How to Write a Great Plot

What Is a Plot?

When we talk of a story’s plot , we typically refer to the sequence of cause-and-effect events that make up the storyline , connecting the story elements to build meaning and engagement with an audience.

Think of a plot like a roadmap. navigating you through the highs and lows of the story revolving around characters and setting, which leads us to a conflict and eventual resolution.

A good plot should keep you engaged, surprising you with twists and turns and moving you towards a satisfying conclusion. It’s what makes a story more than just a collection of random events and gives it direction and purpose.

The plot is arguably the most critical element of a story and can be approached from two perspectives; a traditional approach which is the main focus of this guide, known as a Plot- Driven Narrative (or commonly just a plot) and another popular approach that tells a story through the lens of a stories protagonist known as a C haracter-Driven narrative.

Let’s take a moment to explore the similarities and differences to these storytelling methods.

Plot-Driven Narratives Vs. Character Driven Narratives

These two types of stories account for the narrative structures of most books, movies, plays, and TV dramas. They represent two distinct approaches to storytelling. For students to get good at writing great plots, they should first learn to distinguish between these two perspectives on storytelling.

Character-driven stories focus primarily on the who of the story. They predominantly concern themselves with the inner lives of their protagonists and how events in the outside world affect them psychologically.

In character-driven stories, we follow the struggles and experiences of the story’s characters which usually culminate in a climax that results in a profound change in the life or psychology of the main character.

The critical element of this type of story is character development, which is commonly found in literary fiction.

When exploring a traditional plot or Plot-Drive n Narrative, think of a story propelled forward by the events and actions within it. This is what we call a plot-driven narrative. It’s like a boat that’s pushed forward by the mighty waves of the story’s events, with the characters simply along for the ride.

Plot-driven narratives are focused on the “what” of a story rather than the “who.” They’re driven by twists, turns, and unexpected occurrences, with the goal of keeping the audience engaged and entertained. So, if you love a good mystery or action-packed adventure, a plot-driven narrative might be the path for you to pursue when writing a narrative.

Famous Character-Driven Stories

- The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

- The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

- Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse

- Raging Bull

- The Godfather

Famous Plot-Driven Stories

- Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien

- Jurrasic Park by Michael Crichton

- Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

Whether a story is primarily plot-driven or character-driven, it will require well-drawn characters and a solidly constructed plot to be a good story.

In the rest of this article, we’ll look at the plot’s main elements, some specific plots, and how students can create great plots for their own fantastic stories. We’ll also suggest activities to help students hone their skills in these areas.

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

What Are The key Parts of a Plot?

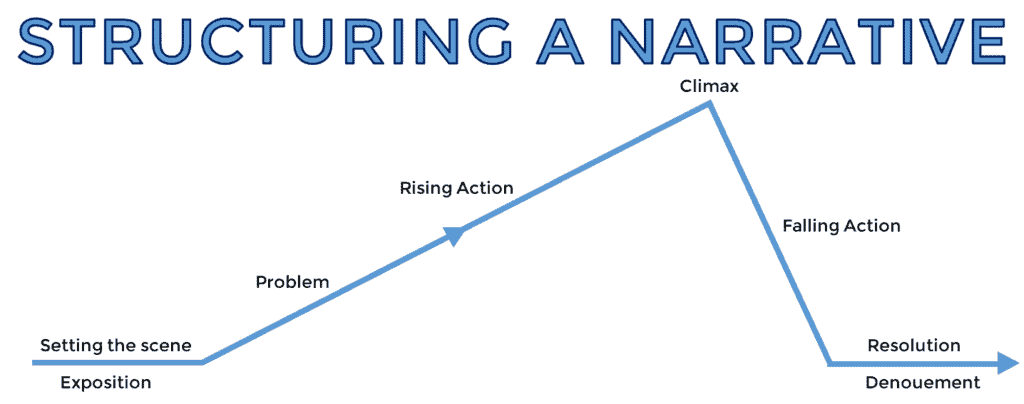

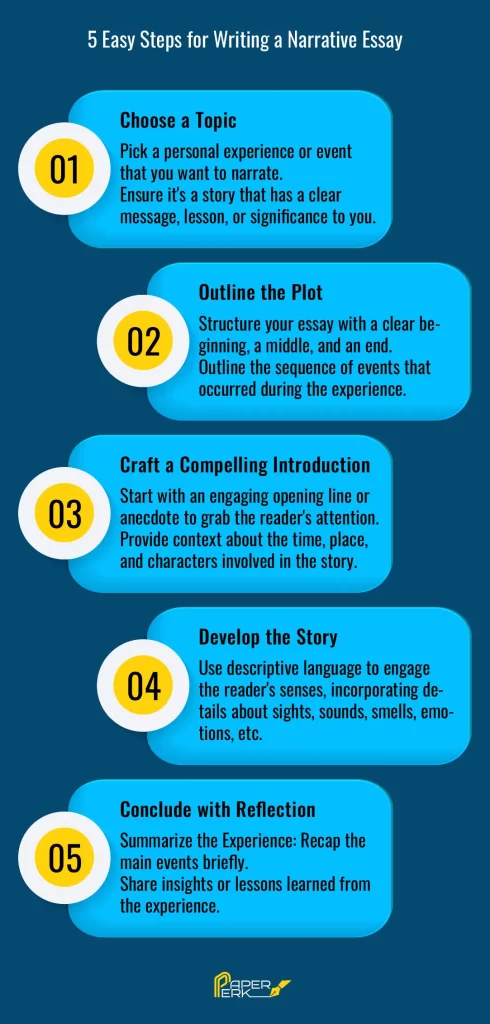

There are six main elements of plot for students to identify and master. These are:

- Conflict or Inciting Incident

- Rising Action

- Falling Action

Below, you’ll find an outline of each element in turn, but if you want to explore these elements in greater detail with your students, check out Our Complete Guide to Narrative Writing here .

1. Exposition

Exposition is all about laying the groundwork. The writer sets the scene in the first paragraphs and introduces the main characters. The exposition orients the reader to the fictional world they are entering.

2. Conflict/Inciting Incident

Every story needs a problem to drive the plot forward. We call this the ‘conflict’ or ‘inciting incident.’ At this stage of the narrative, an incident or a conflict occurs that sees the main character facing a challenge of some sort. This breaks the normality established in the exposition by setting a chain of events in motion that will form the story’s plot.

3. Rising Action

The conflict/inciting event sets off a sequence of causally linked episodes that gradually amp up the dramatic tension as the story builds towards the climax. This process of building tension through raising the stakes is called rising action.

The climax is the dramatic high point of the story, where everything comes to a head. This is where the story’s conflict will ultimately be resolved, usually in a moment of high excitement.

5. Falling Action

As the dramatic tension gets released in the excitement of the climax, the narrative begins to wind down. As the dust settles on the climactic scene, we begin to see the consequences on the characters and the world around them.

6. Resolution/Denouement

Sometimes known as a denouement, the resolution is the plot’s final section, where the conflict’s loose ends are tied up. This section has a finality as it establishes new normalcy in the wake of recent events.

The Classic Three Act Plot Structure Explained

If you are looking for the 5-minute explanation of how to write a strong plot without going into too many details and complexity, allow me to introduce you to the granddaddy of all story structures: the three-act plot. Think of it as a theatrical performance, with each act serving a specific purpose in the storytelling journey.

Act 1, is all about setup : It’s here where you introduce your characters, establish the setting, and create a sense of what’s at stake in the story.

Act 2 is where the drama takes center stage : At this point conflict arises, obstacles are placed in the characters’ way, and tensions rise and grow.

And finally, Act 3 is the grand finale : Where all the story threads come together in a resolution. Loose ends are tied up, conflicts are resolved, and your audience gets the payoff they’ve been waiting for.

So, there it is, next time you’re crafting a story, consider using this tried and true three-act structure to guide your plot and keep your audience engaged.

The & Basic Plot Types (With Prompts)

In the book world, we commonly find plot-driven genre fiction topping the paperback bestseller lists. In fact, most popular fiction known as ‘genre fiction’ is plot-driven.

Genre fiction comes in many forms, for example, science fiction, romance, fantasy, thrillers, and horror, to name but a few.

Whatever the genre, we find many of the same plot types recurring within the well-thumbed pages of these most popular of books. For students to write their own great plots, they’ll need to understand the time-tested seven basic patterns that plots follow.

Let’s take a look at the most common of these plot types along with a writing prompt to get your students to write an example of each.

A genre with ancient roots, tragedies focus on events of great sorrow, suffering, distress and/or destruction. With roots in ancient Greek drama, tragedy treats the plot and the themes it raises with a serious and sombre tone.

Examples: Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Prompt: A story opens with the hero’s untimely death. Can the student go back and tell the story of how events led to such a tragedy?

For the ancient Greeks, comedy represented the dramatic opposite of tragedy. Where tragedy is serious and somber, comedy is light-hearted and humorous. Comedy has many subgenres, including sarcasm , parody, farce, satire, slapstick, romantic comedy, screwball, and even dark humor.

Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams.

Prompt: There is a man who, due to a rare condition, cannot lie. No matter how desperately he wants to avoid telling the truth, he just cannot lie. What happens next?

iii. The Quest

As its name suggests, the quest plotline involves a journey of some sort to find a particular person, place, or item. Sometimes the quest is in pursuit of fame or fortune. Often, the thing being sought isn’t as important as the drama that happens along the way.

Examples: The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien, Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark

Prompt: A young girl escapes from her unhappy home and her mean stepmother in search of a better future. Write what happens to her.

iv. The Voyage and Return

In some ways similar to the quest, except there is the added element of the return home. Typically, the hero enters a new land (often magical) where things are very different. Eventually, the hero, changed by events, returns home. Having learned some important lessons, they bring that new knowledge or discovery back home with them.

Examples: Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L Frank Baum

Prompt: A prince is engaged to be married to a princess. She has been kidnapped by an evil rival. The prince must journey to find her with the hopes of bringing her home.

v. The Monster

In this type of plot, the hero must eliminate the threat posed by some sort of beast or evil entity such as a dragon, vampire, ghost, or demon. By destroying this monster, the hero will restore order and safety to the world.

Examples: Dracula by Bram Stoker, Jack and the Beanstalk (Traditional)

Prompt: The sea beast arises from the dark depths of the oceans and develops a taste for human flesh. The hero must find a way to stop this evil predator before his whole village is wiped out.

vi. Rebirth

Here, we witness the events leading to the redemption and rebirth of the main character who previously struggled with their place in the world. At the end of this type of story, there is a shift where the world is restored to a balance.

Examples: A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, Lion King

Prompt: A cruel orphanage owner stumbles across a foundling in the forest. This event sets in action a chain of events that leads to the orphanage owner’s redemption. Write what happens.

vii. Rags to Riches

This plot type charts the hero’s rise from humble origins through adversity to the heights of fame and fortune.

Examples: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, The Pursuit of Happyness

Prompt: A neglected child escapes from her unhappy home and struggles to provide for herself in the cold, uncaring city. One day, she meets an unlikely benefactor, beginning a sequence of events that will forever change her life. Write what happens.

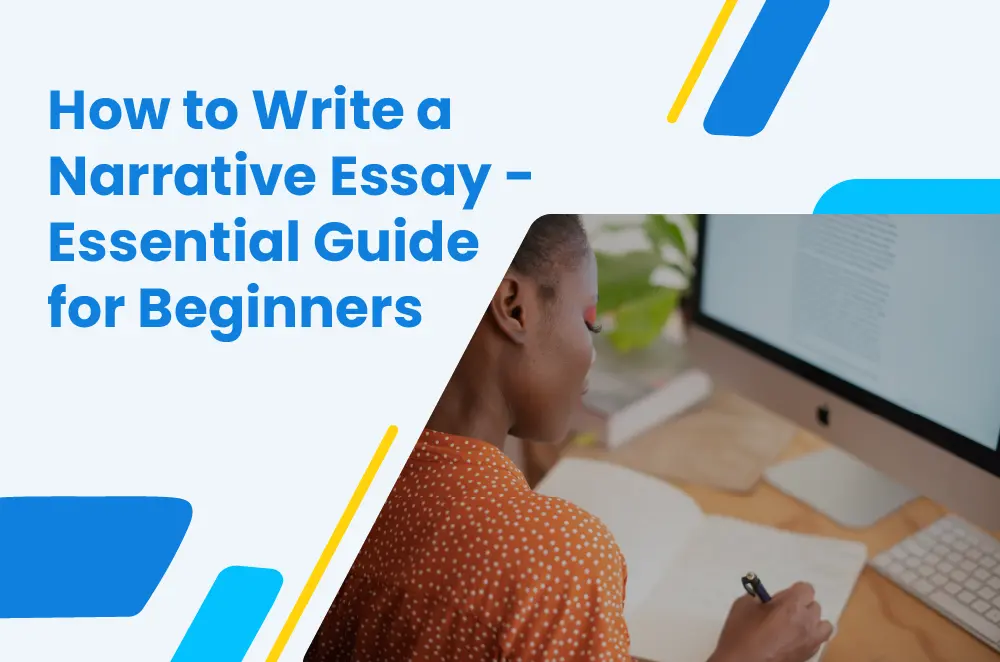

How to Write a Great Plot: A Step-by-Step Process

Step 1: Generate Some Ideas

A story begins with the seed of an idea. Students can begin this process by deciding on one of the basic plot types above and then brainstorming a list of five events that might ignite a story.

Encourage the students to draw on their own life experiences, that of their friends and family members, and on things they’ve read about or seen on the news, for example.

Step 2: Create a Premise

Once they have the initial germ of an idea, it’s time to get the premise written down. The premise is a few sentences that express the proposed plot of the story in simple terms.

Step 3: Choose Characters and a Setting

Now it’s time to create the characters and choose the settings for the tale’s action to be played out. Writing brief character profiles, including some bullet points of their backstories, can be a great way to help the student build believable characters.

For settings, creating a collage from photos, pictures, and illustrations can be an effective way to inspire vivid descriptions in the student’s work.

With these elements in place, the students can begin writing the exposition part of their stories.

Step 4: Introduce the Central Conflict

No problem = no story!

Whether it’s called the central conflict, problem, or inciting incident, the student now needs to introduce it to anchor the plot and begin creating tension in the story.

At this point, examining this element in well-known stories in the same genre will be helpful for the student.

Ask the students to think about their favorite books and movies. Can they identify the central conflict in each?

Step 5: Map Out a Path to the Resolution

With the central conflict firmly in place, a set of logical cause-and-effect dominoes now needs to be set up to take the plotline up the ladder of rising action to the climax and subsequent resolution.

Storyboarding is a highly effective way of helping students visualize their plot arc before committing to writing. Remind students of the importance of ensuring each scene connects causally.

When the climax has been reached, the dust will settle in the falling action to reveal the consequences of the actions and see new normalcy established in the resolution.

Tips for Writing a Great Plot

- Start with a strong hook: Begin your story with an interesting and attention-grabbing scene to grab your reader’s attention .

- Know your genre: Study the conventions and expectations of the genre you write in, so you can effectively play within those boundaries.

- Create memorable characters: Develop dynamic and compelling characters that drive the story forward.

- Build conflict: Your story needs conflict, whether it’s internal or external, to keep the plot moving.

- Use the three-act structure: Follow the classic three-act structure of setup, confrontation, and resolution to keep your plot structured and focused.

- Introduce twists and turns: Add unexpected events and plot twists to keep your audience engaged and on their toes.

- Keep it simple: Avoid complicating your plot with too many subplots or unnecessary details.

- Use foreshadowing: Plant hints and clues throughout the story to create suspense and keep your audience guessing.

- Have a clear resolution: Make sure your story has a satisfying conclusion that wraps up loose ends and resolves conflicts.

- Write with passion: Write from the heart, imbuing your plot with your own experiences and emotions to create a story that resonates with your reader.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING STORY ELEMENTS

☀️This HUGE resource provides you with all the TOOLS, RESOURCES , and CONTENT to teach students about characters and story elements.

⭐ 75+ PAGES of INTERACTIVE READING, WRITING and COMPREHENSION content and NO PREPARATION REQUIRED.

Plot Teaching Strategies and Activities

Following the structural elements laid out above, combined with the conventions of a basic plot type chosen from the seven types above, students should be well-placed to construct a well-ordered plotline.

If the above description of how to write a great plot seems too prescriptive initially, it’s worth noting that there is considerable creative freedom within the structures described in this article.

The plot types listed above have been identified from the shapes and patterns of thousands of our favorite tales told across the centuries rather than being templates that are laid out to be studiously followed. As humans, we are pattern-recognizing machines. It is in patterns that we find meaning.

Teaching Activities

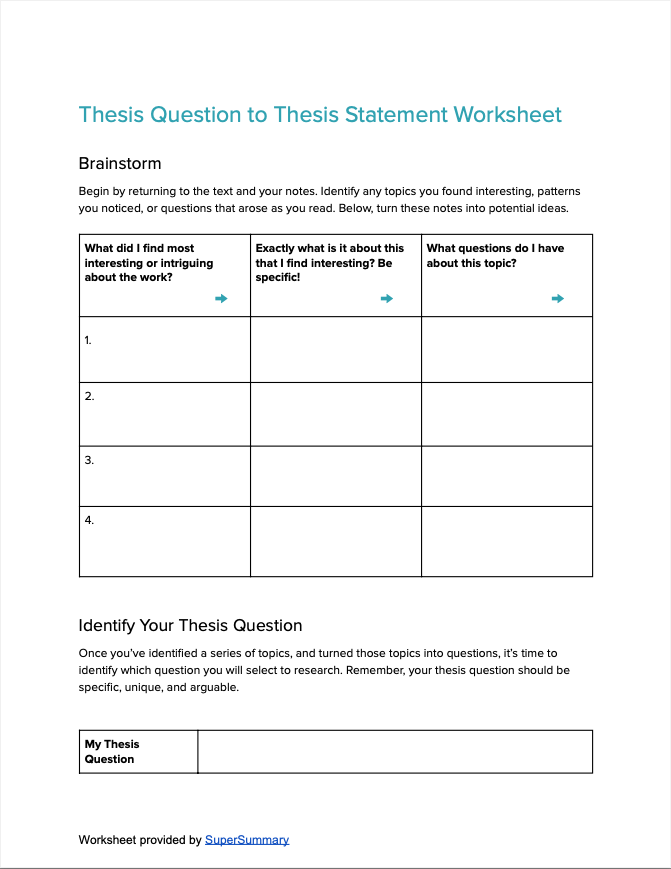

- Story mapping: Have students create visual representations of the events and elements in a story to help them understand the structure of a plot.

- Analyzing plot in literature: Analyze and discuss the plot structure of well-known books and movies to see how different elements contribute to the overall story.

- Plot planning worksheet : Provide students with a worksheet or graphic organizer such as this to plan out their own story, including key events, characters, and conflicts.

- Writing workshops: Encourage students to workshop their own stories with peers, providing feedback on plot structure and pacing.

- Create story arcs: Teach students about the basic story arc and have them practice creating their own arcs for short stories or character arcs for longer works.

Once students get used to these underlying structures, they can begin to let their imaginations run away with them, safe in the knowledge that a coherent story will emerge from their bursts of creativity.

Plot Definition

What is plot? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Plot is the sequence of interconnected events within the story of a play, novel, film, epic, or other narrative literary work. More than simply an account of what happened, plot reveals the cause-and-effect relationships between the events that occur.

Some additional key details about plot:

- The plot of a story explains not just what happens, but how and why the major events of the story take place.

- Plot is a key element of novels, plays, most works of nonfiction, and many (though not all) poems.

- Since ancient times, writers have worked to create theories that can help categorize different types of plot structures.

Plot Pronounciation

Here's how to pronounce plot: plaht

The Difference Between Plot and Story

Perhaps the best way to say what a plot is would be to compare it to a story. The two terms are closely related to one another, and as a result, many people often use the terms interchangeably—but they're actually different. A story is a series of events; it tells us what happened . A plot, on the other hand, tells us how the events are connected to one another and why the story unfolded in the way that it did. In Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster uses the following examples to distinguish between story and plot:

“The king died, and then the queen died” is a story. “The king died, and then the queen died of grief” is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: “The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.” This is a plot with a mystery in it.

Therefore, when examining a plot, it's helpful to look for events that change the direction of the story and consider how one event leads to another.

The Structure of a Plot

For nearly as long as there have been narratives with plots, there have been people who have tried to analyze and describe the structure of plots. Below we describe two of the most well-known attempts to articulate the general structure of plot.

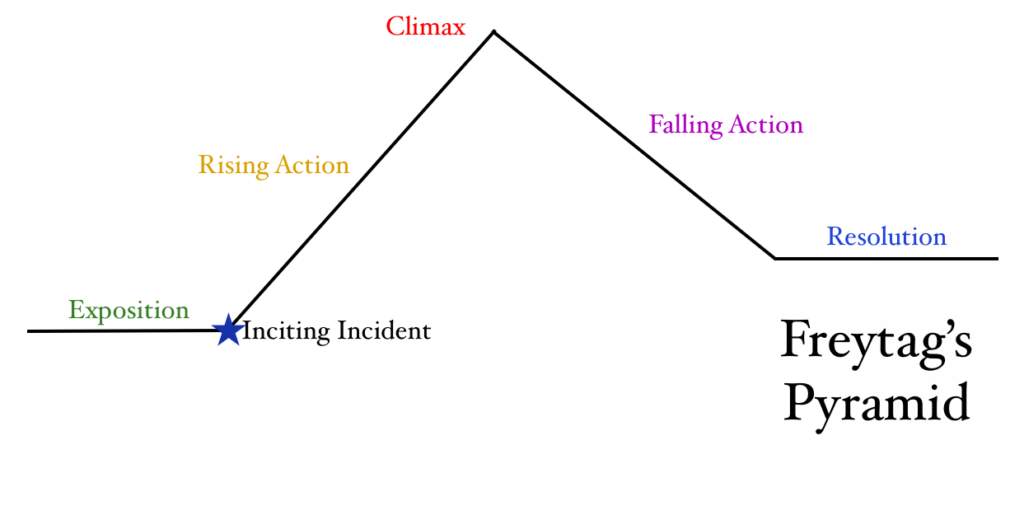

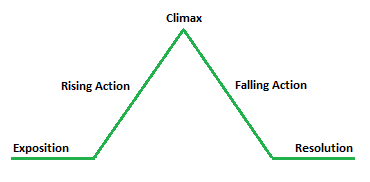

Freytag's Pyramid

One of the first and most influential people to create a framework for analyzing plots was 19th-century German writer Gustav Freytag, who argued that all plots can be broken down into five stages: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement. Freytag originally developed this theory as a way of describing the plots of plays at a time when most plays were divided into five acts, but his five-layered "pyramid" can also be used to analyze the plots of other kinds of stories, including novels, short stories, films, and television shows.

- Exposition is the first section of the plot. During the exposition, the audience is introduced to key background information, including characters and their relationships to one another, the setting (or time and place) of events, and any other relevant ideas, details, or historical context. In a five-act play, the exposition typically occurs in the first act.

- The rising action begins with the "inciting incident" or "complication"—an event that creates a problem or conflict for the characters, setting in motion a series of increasingly significant events. Some critics describe the rising action as the most important part of the plot because the climax and outcome of the story would not take place if the events of the rising action did not occur. In a five-act play, the rising action usually takes place over the course of act two and perhaps part of act three.

- The climax of a plot is the story's central turning point, which the exposition and the rising action have all been leading up to. The climax is the moment with the greatest tension or conflict. Though the climax is also sometimes called the crisis , it is not necessarily a negative event. In a tragedy , the climax will result in an unhappy ending; but in a comedy , the climax usually makes it clear that the story will have a happy ending. In a five-act play, the climax usually takes place at the end of the third act.

- Whereas the rising action is the series of events leading up to the climax, the falling action is the series of events that follow the climax, ending with the resolution, an event that indicates that the story is reaching its end. In a five-act play, the falling action usually takes place over the course of the fourth act, ending with the resolution.

- Dénouement is a French word meaning "outcome." In literary theory, it refers to the part of the plot which ties up loose ends and reveals the final consequences of the events of the story. During the dénouement, the author resolves any final or outstanding questions about the characters’ fates, and may even reveal a little bit about the characters’ futures after the resolution of the story. In a five-act play, the dénouement takes place in the fifth act.

While Freytag's pyramid is very handy, not every work of literature fits neatly into its structure. In fact, many modernist and post-modern writers intentionally subvert the standard narrative and plot structure that Freytag's pyramid represents.

Booker's "Meta-Plot"

In his 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, Christopher Booker outlines an overarching "meta-plot" which he argues can be used to describe the plot structure of almost every story. Like Freytag's pyramid, Booker's meta-plot has five stages:

- The anticipation stage , in which the hero prepares to embark on adventure;

- The dream stage , in which the hero overcomes a series of minor challenges and gains a sense of confidence and invincibility;

- The frustration stage , in which the hero confronts the villain of the story;

- The nightmare stage , in which the hero fears they will be unable to overcome their enemy;

- The resolution , in which the hero finally triumphs.

Of course, like Freytag's Pyramid, Booker's meta-plot isn't actually a fool-proof way of describing the structure of every plot, but rather an attempt to describe structural elements that many (if not most) plots have in common.

Types of Plot

In addition to analyzing the general structure of plots, many scholars and critics have attempted to describe the different types of plot that serve as the basis of most narratives.

Booker's Seven Basic Plots

Within the overarching structure of Booker's "meta-plot" (as described above), Booker argues that plot types can be further subdivided into the following seven categories. Booker himself borrows most of these definitions of plot types from much earlier writers, such as Aristotle. Here's a closer look at each of the seven types:

- Comedy: In a comedy , characters face a series of increasingly absurd challenges, conflicts, and misunderstandings, culminating in a moment of revelation, when the confusion of the early part of the plot is resolved and the story ends happily. In romantic comedies, the early conflicts in the plot act as obstacles to a happy romantic relationship, but the conflicts are resolved and the plot ends with an orderly conclusion (and often a wedding). A Midsummer Night's Dream , When Harry Met Sally, and Pride and Prejudice are all examples of comedies.

- Tragedy: The plot of a tragedy follows a tragic hero —a likable, well-respected, morally upstanding character who has a tragic flaw or who makes some sort of fatal mistake (both flaw and/or mistake are known as hamartia ). When the tragic hero becomes aware of his mistake (this realization is called anagnorisis ), his happy life is destroyed. This reversal of fate (known as peripeteia ) leads to the plot's tragic ending and, frequently, the hero's death. Booker's tragic plot is based on Aristotle's theory of tragedy, which in turn was based on patterns in classical drama and epic poetry. Antigone , Hamlet , and The Great Gatsby are all examples of tragedies.

- Rebirth: In stories with a rebirth plot, one character is literally or metaphorically imprisoned by a dark force, enchantment, and/or character flaw. Through an act of love, another character helps the imprisoned character overcome the dark force, enchantment, or character flaw. Many stories of rebirth allude to Jesus Christ or other religious figures who sacrificed themselves for others and were resurrected. Beauty and the Beast , The Snow Queen , and A Christmas Carol are all examples of stories with rebirth plots.

- Overcoming the Monster: The hero sets out to fight an evil force and thereby protect their loved ones or their society. The "monster" could be literal or metaphorical: in ancient Greek mythology, Perseus battles the monster Medusa, but in the television show Good Girls Revolt , a group of women files a lawsuit in order to fight discriminatory policies in their workplace. Both examples follow the "Overcoming the Monster" plot, as does the epic poem Beowulf .

- Rags-to-Riches : In a rags-to-riches plot, a disadvantaged person comes very close to gaining success and wealth, but then appears to lose everything, before they finally achieve the happy life they have always deserved. Cinderella and Oliver Twist are classic rags-to-riches stories; movies with rags-to-riches plots include Slumdog Millionaire and Joy .

- The Quest: In a quest story, a hero sets out to accomplish a specific task, aided by a group of friends. Often, though not always, the hero is looking for an object endowed with supernatural powers. Along the way, the hero and their friends face challenges together, but the hero must complete the final stage of the quest alone. The Celtic myth of "The Fisher-King and the Holy Grail" is one of the oldest quest stories; Monty Python and the Holy Grail is a satire that follows the same plot structure; while Heart of Darkness plays with the model of a quest but has the quest end not with the discovery of a treasure or enlightenment but rather with emptiness and disillusionment.

- Voyage and Return: The hero goes on a literal journey to an unfamiliar place where they overcome a series of challenges, then return home with wisdom and experience that help them live a happier life. The Odyssey , Alice's Adventures in Wonderland , Chronicles of Narnia, and Eat, Pray, Love all follow the voyage and return plot.

As you can probably see, there's lots of room for these categories to overlap. This is one of the problems with trying to create any sort of categorization scheme for plots such as this—an issue we'll cover in greater detail below.

The Hero's Journey

The Hero's Journey is an attempt to describe a narrative archetype , or a common plot type that has specific details and structure (also known as a monomyth ). The Hero's Journey plot follows a protagonist's journey from the known to the unknown, and back to the known world again. The journey can be a literal one, as in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, or a purely metaphorical one. Regardless, the protagonist is a changed person by the end of the story. The Hero's Journey structure was first popularized by Joseph Campbell's 1949 book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Later, theorists David Adams Leeming, Phil Cousineau, and Christopher Vogler all developed their own versions of the Hero's Journey structure. Each of these theorists divides The Hero's Journey into slightly different stages (Campbell identifies 17 stages, whereas Vogler finds 12 stages and Leeming and Cousineau use just 8). Below, we'll take a closer look at the 12 stages that Vogler outlines in his analysis of this plot type:

- The Ordinary World: When the story begins, the hero is a seemingly ordinary person living an ordinary life. This section of the story often includes expository details about the story's setting and the hero's background and personality.

- The Call to Adventure: Soon, the hero's ordinary life is interrupted when someone or something gives them an opportunity to go on a quest. Often, the hero is asked to find something or someone, or to defeat a powerful enemy. The call to adventure sometimes, but not always, involves a supernatural event. (In Star Wars: A New Hope , the call to adventure occurs when Luke sees the message from Leia to Obi-Wan Kenobi.)

- The Refusal of the Call: Some heroes are initially reluctant to embark on their journey and instead attempt to continue living their ordinary life. When this refusal takes place, it is followed by another event that prompts the hero to accept the call to adventure (Luke's aunt and uncle getting killed in Star Wars ).

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero meets a mentor: a wiser, more experienced person who gives them advice and guidance. The mentor trains and protects the hero until the hero is ready to embark on the next phase of the journey. (Obi-Wan Kenobi is Luke's mentor in Star Wars .)

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero "crosses the threshold" when they have left the familiar, ordinary world behind. Some heroes are eager to enter a new and unfamiliar world, while others may be uncertain if they are making the right choice, but in either case, once the hero crosses the threshold, there is no way to turn back. (Luke about to enter Mos Eisley, or of Frodo leaving the Shire in Lord of the Rings .)

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: As the hero continues on their journey, they face a series of increasingly difficult "tests" or challenges. Along the way, they acquire friends who help them overcome these challenges, and enemies who attempt to thwart their quest. The hero may defeat some enemies during this phase or find ways to keep them temporarily at bay. These challenges help the reader develop a better a sense of the hero's strengths and weaknesses, and they help the hero become wiser and more experienced. This phase is part of the rising action .

- Approach to the Innermost Cave: At this stage, the hero prepares to face the greatest challenge of the journey, which lies within the "innermost cave." In some stories, the hero must literally enter an isolated and dangerous place and do battle with an evil force; in others, the hero must confront a fear or face an internal conflict; or, the hero may do both. You can think of the approach to the innermost cave as a second threshold—a moment when the hero faces their doubts and fears and decides to continue on the quest. (Think of Frodo entering Mordor, or Harry Potter entering the Forbidden Forest with the Deathly Hallows, ready to confront Lord Voldemort.)

- The Ordeal: The ordeal is the greatest challenge that the hero faces. It may take the form of a battle or physically dangerous task, or it may represent a moral or personal crisis that threatens to destroy the hero. Earlier (in the "Tests, Allies, and Enemies" phase), the hero might have overcome challenges with the help of friends, but the hero must face the ordeal alone. The outcome of the ordeal often determines the fate of the hero's loved ones, society, or the world itself. In many stories, the ordeal involves a literal or metaphorical resurrection, in which the hero dies or has a near-death experience, and is reborn with new knowledge or abilities. This constitutes the climax of the story.

- Reward: After surviving the ordeal, the hero receives a reward of some kind. Depending on the story, it may come in the form of new wisdom and personal strengths, the love of a romantic interest, a supernatural power, or a physical prize. The hero takes the reward or rewards with them as they return to the ordinary world.

- The Road Back: The hero begins to make their way home, either by retracing their steps or with the aid of supernatural powers. They may face a few minor challenges or setbacks along the way. This phase is part of the falling action .

- The Resurrection: The hero faces one final challenge in which they must use all of the powers and knowledge that they have gained throughout their journey. When the hero triumphs, their rebirth is completed and their new identity is affirmed. This phase is not present in all versions of the hero's journey.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero reenters the ordinary world, where they find that they have changed (and perhaps their home has changed too). Among the things they bring with them when they return is an "elixir," or something that will transform their ordinary life for the better. The elixir could be a literal potion or gift, or it may take the form of the hero's newfound perspective on life: the hero now possesses love, forgiveness, knowledge, or another quality that will help them build a better life.

Other Genre-Specific Plots

Apart from the plot types described above (the "Hero's Journey" and Booker's seven basic plots), there are a couple common plot types worth mentioning. When a story uses one of the following plots, it usually means that it belongs to a specific genre of literature—so these plot structures can be thought of as being specific to their respective genres.

- Mystery : A story that centers around the solving of a baffling crime—especially a murder. The plot structure of a mystery can often be described using Freytag's pyramid (i.e., it has exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement), but the plots of mysteries also tend to follow other, more genre-specific conventions, such as the gradual discovery of clues culminating in the revelation of the culprit's identity as well as their motive. In a typical story (i.e., a non-mystery) key characters and their motives are usually revealed before the central conflict arises, not after.

- Bindungsroman : A story that shows a young protagonist's journey from childhood to adulthood (or immaturity to maturity), with a focus on the trials and misfortunes that affect the character's growth. The term "coming-of-age novel" is sometimes used interchangeably with Bildungsroman. This is not necessarily incorrect—in most cases the terms can be used interchangeably—but Bildungsroman carries the connotation of a specific and well-defined literary tradition, which tends to follow certain genre-specific conventions (for example, the main character often gets sent away from home, falls in love, and squanders their fortune). The climax of the Bildungsroman typically coincides with the protagonist reaching maturity.

Other Attempts to Classify Types of Plots

In addition to Freytag, Booker, and Campbell, many other theorists and literary critics have created systems classifying different kinds of plot structures. Among the best known are:

- William Foster-Harris, who outlined three archetypal plot structures in The Basic Patterns of Plot

- Ronald R. Tobias, who wrote a book claiming there are 20 Master Plots

- Georges Polti, who argued there are in fact Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations

- Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch, who in the early twentieth century outlined seven types of plot

And then there are the more atypical approaches to classifying the different types of plots:

- In 1965, the University of Chicago rejected Kurt Vonnegut's college thesis, which claimed that folktales and fairy tales shared common structures, or "shapes," including "man in a hole," "boy gets girl" and "Cinderella." He went on to write Slaughterhouse-Five , a novel which subverts traditional narrative structures, and later developed a lecture based on his failed thesis .

- Two recent studies, led by University of Nebraska professor Matthew Jockers and researchers at the University of Adelaide and the University of Vermont respectively, have used machine learning to analyze the plot structures and emotional ups-and-downs of stories. Both projects concluded that there are six types of stories.

Criticism of Efforts to Categorize Plot Types

Some critics argue that though archetypal plot structures can be useful tools for both writers and readers, we shouldn't rely on them too heavily when analyzing a work of literature. One such skeptic is New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani, who in a 2005 review described Christopher Booker's Seven Basic Plots as "sometimes absorbing and often blockheaded." Kakutani writes that while Booker finds interesting ways to categorize stories by plot type, he is too fixated on finding stories that fit these plot types perfectly. As a result, Booker tends to idealize overly simplistic stories (and Hollywood films in particular), instead of analyzing more complex stories that may not fit the conventions of his seven plot types. Kakutani argues that, as a result of this approach, Booker undervalues modern and contemporary writers who structure their plots in different and innovative ways.

Kakutani's argument is a reminder that while some great works of literature may follow archetypal plot structures, they may also have unconventional plot structures that defy categorization. Authors who use nonlinear structures or multiple narrators often intentionally create stories that do not perfectly fit any of the "plot types" discussed above. William Faulker's The Sound and the Fury and Jennifer Egan's A Visit From the Goon Squad are both examples of this kind of work. Even William Shakespeare, who wrote many of his plays following the traditional structures for tragedies and comedies, authored several "problem plays," which many scholars struggle to categorize as strictly tragedy or comedy: All's Well That Ends Well , Measure for Measure , Troilus and Cressida, The Winter's Tale , Timon of Athens, and The Merchant of Venice are all examples of "problem plays."

Plot Examples

The following examples are representative of some of the most common types of plot.

The "Hero's Journey" Plot in The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

The plot of The Hobbit closely follows the structure of a typical hero's journey.

- The Ordinary World: At the beginning of The Hobbit , the story's hero, Bilbo Baggins, is living a comfortable life alongside his fellow hobbits in the Shire. (Hobbits are short, human-like creatures predisposed to peaceful, domestic routines.)

- The Call to Adventure: The wizard Gandalf arrives in the Shire with a band of 13 dwarves and asks Bilbo to go with them to Lonely Mountain in order to reclaim the dwarves' treasure, which has been stolen by the dragon Smaug.

- The Refusal of the Call: At first, Bilbo refuses to join Gandalf and the dwarves, explaining that it isn't in a hobbit's nature to go on adventures.

- Meeting the Mentor: Gandalf, who serves as Bilbo's mentor throughout The Hobbit, persuades Bilbo to join the dwarves on their journey.

- Cross the Threshold: Gandalf takes Bilbo to meet the dwarves at the Green Dragon Inn in Bywater, and the group leaves the Shire together.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: Bilbo faces many challenges and trials on the way to the Lonely Mountain. Early in the trip, they are kidnapped by trolls and are rescued by Gandalf. Bilbo takes an elvish dagger from the trolls' supply of weapons that he uses throughout the rest of the journey. Soon Bilbo and the dwarves are captured by goblins, but they are rescued by Gandalf who also kills the Great Goblin. Later, Bilbo finds a magical ring (which becomes the focus of the Lord of the Rings books), and when the dwarves are captured later in the journey (once by giant spiders and once by elves), Bilbo uses the ring and the dagger to rescue them. Finally, Bilbo and the dwarves arrive at Lake Town, near the Lonely Mountain.

- Approach to the Innermost Cave: Bilbo and the dwarves makes his way from Lake Town to the Lonely Mountain, where the dragon Smaug is guarding the dwarves' treasure. Bilbo alone is brave enough to enter the Smaug's lair. Bilbo steals a cup from Smaug, and also learns that Smaug has a weak spot in his scaly armor. Enraged at Bilbo's theft, Smaug flies to Lake-Town and devastates it, but is killed by a human archer who learns of Smaug's weak spot from a bird that overheard Bilbo speaking of it.

- The Ordeal: After Smaug's death, elves and humans march to the Lonely Mountain to claim what they believe is their portion of the treasure (as Smaug plundered from them, too). The dwarves refuse to share the treasure and a battle seems evident, but Bilbo steals the most beautiful gem from the treasure and gives it to the humans and elves. The greedy dwarves banish Bilbo from their company. Meanwhile, an army of wargs (magical wolves) and goblins descend on the Lonely Mountain to take vengeance on the dwarves for the death of the Great Goblin. The dwarves, humans, and elves form an alliance to fight the wargs and goblins, and eventually triumph, though Bilbo is knocked unconscious for much of the battle. (It might seem odd that Bilbo doesn't participate in the battle, but that fact also seems to suggest that the true ordeal of the novel was not the battle but rather Bilbo's moral choice to steal the gem and give it to the men and elves to counter the dwarves growing greed.)

- Reward: The victorious dwarves, humans, and elves share the treasure among themselves, and Bilbo receives a share of the treasure, which he takes home, along with the dagger and the ring.

- The Road Back: It takes Bilbo and Gandalf nearly a year to travel back to the Shire. During that time they e-visit with some of the people they met on their journey out and have many adventures, though none are as difficult as those they undertook on the way to the Lonely Mountain.

- The Resurrection: Bilbo's return to the Shire as a changed person is underlined by the fact that he has been away so long, the other hobbits in the Shire believe that he has died and are preparing to sell his house and belongings.

- Return with the Elixir: Bilbo returns to the shire with the ring, the dagger, and his treasure—enough to make him rich. He also has his memories of the adventure, which he turns into a book.

Other examples of the Hero's Journey Plot Structure:

- Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

- The Epic of Gilgamesh

- The Martian by Andy Weir

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- The Iliad by Homer

The Comedic Plot in Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare's play, Twelfth Night , is generally described as a comedy and follows what Booker would call comedic plot structure. At the beginning of the play, the protagonist, Viola is shipwrecked far from home in the kingdom of Illyria. Her twin brother, Sebastian, appears to have died in the storm. Viola disguises herself as a boy, calls herself Cesario, and gets a job as the servant of Count Orsino, who is in love with the Lady Olivia. When Orsino sends Cesario to deliver romantic messages to Olivia on his behalf, Olivia falls in love with Cesario. Meanwhile, Viola falls in love with Orsino, but she cannot confess her love without revealing her disguise.

In another subplot, Olivia's uncle Toby and his friend Sir Andrew Aguecheek persuade the servant Maria to play a prank convincing another servant, Malvolio, that Olivia loves him. The plot thickens when Sebastian (Viola's lost twin) arrives in town and marries Olivia, who believes she is marrying Cesario. At the end of the play, Viola is reunited with her brother, reveals her identity, and confesses her love to Orsino, who marries her. In spite of the chaos, misunderstandings, and challenges the characters face in the early part of the plot—a source of much of the play's humor— Twelfth Night reaches an orderly conclusion and ends with two marriages.

Other examples of comedic plot structure:

- Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare

- A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare

- Love's Labor's Lost by William Shakespeare

- Emma by Jane Austen

- Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Lysistrata by Aristophanes

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

The Tragic Plot in Macbeth by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare's play Macbeth follows the tragic plot structure. The tragic hero , Macbeth, is a Scottish nobleman, who receives a prophecy from three witches saying that he will become the Thane of Cawdor and eventually the King. After King Duncan makes Macbeth Thane of Cawdor, Lady Macbeth persuades her husband to fulfill the prophecy by secretly murdering Duncan. He does, and is named King. Later, to ensure that Macbeth will remain king, they also order the assassination of the nobleman Banquo, his son, and the wife and children of the nobleman Macduff. However, as Macbeth protects his throne in ever more bloody ways, Lady Macbeth begins to go mad with guilt. Macbeth consults the witches again, and they reassure him that "no man from woman born can harm Macbeth" and that he will not be defeated until the "wood begins to move" to Dunsinane castle. Therefore, Macbeth is reassured that he is invincible. Lady Macbeth never recovers from her guilt and commits suicide, and Macbeth feels numb and empty, even as he is certain he can never be killed. Meanwhile an army led by Duncan's son Malcolm, their number camouflaged by the branches they carry, so that they look like a moving forest, approaches Dunsinane. In the fighting Macduff reveals he was born by cesarian section, and kills Macbeth.

Macbeth's mistake ( hamartia ) is his unrelenting ambition to be king, and his trust in the witches' prophecies. He realizes his mistake in a moment of anagnorisis when the forest full of camouflaged soldiers seems to be moving, and he experiences a reversal of fate ( peripeteia ) when he is defeated by Macduff.

Other examples of tragic plot structure:

- Antigone by Sophocles

- Oedipus at Colonus by Sophocles

- Agamemnon by Aeschylus

- The Libation Bearers by Aeschylus

- The Eumenides by Aeschylus

- Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare

- Othello by William Shakespeare

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

- The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The "Rebirth" Plot in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens' novel A Christmas Carol is an example of the "rebirth" plot. The novel's protagonist is the miserable, selfish businessman Ebenezer Scrooge, who mistreats his clerk, Bob Cratchit, who is a loving father struggling to support his family. Scrooge scoffs at the notion that Christmas is a time for joy, love, and generosity. But on Christmas Eve, he is visited by the ghost of his deceased business partner, who warns Scrooge that if he does not change his ways, his spirit will be condemned to wander the earth as a ghost. Later that night, he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present, and Christmas Yet to Come. With these ghosts, Scrooge revisits lonely and joyful times of his youth, sees Cratchit celebrating Christmas with his loved ones, and finally foresees his own lonely death. Scrooge awakes on Christmas morning and resolves to change his ways. He not only celebrates Christmas with the Cratchits, but embraces the Christmas spirit of love and generosity all year long. By the end of the novel, Scrooge has been "reborn" through acts of generosity and love.

Other examples of "rebirth" plot structure:

- The Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare

- The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

- The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood

- Beloved by Toni Morrison

- Snow White by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

- The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Anderson

- Beauty and the Beast by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve

The "Overcoming the Monster" Plot in Beowulf

The Old English epic poem, Beowulf , follows the structure of an "overcoming the monster" plot. In fact, the poem's hero, Beowulf, defeats not just one monster, but three. As a young warrior, Beowulf slays Grendel, a swamp-dwelling demon who has been raiding the Danish king's mead hall. Later, when Grendel's mother attempts to avenge her son's death, Beowulf kills her, too. Beowulf eventually becomes king of the Geats, and many years later, he battles a dragon who threatens his people. Beowulf manages to kill the dragon, but dies from his wounds, and is given a hero's funeral. Three times, Beowulf succeeds in protecting his people by defeating a monster.

Other examples of the overcoming the monster plot structure:

- Dracula by Bram Stoker

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling

The "Rags-to-Riches" Plot in Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre is an example of a "rags-to-riches" plot. The protagonist, Jane, is a mistreated orphan who is eventually sent away to a boarding school where students are severely mistreated. Jane survives the school and goes on to become a governess at Thornfield Manor, where Jane falls in love with Mr. Rochester. The two become engaged, but on their wedding day, Jane discovers that Rochester's first wife, Bertha, has gone insane and is imprisoned in Thornfield's attic. She leaves Rochester and ends up finding long-lost cousins. After a time, her very religious cousin, St. John, proposes to her. Jane almost accepts, but then rejects the proposal. She returns to Thornfield to discover that Bertha started a house fire and leapt off the roof of the burning building to her death, and that Rochester had been blinded by the fire in an attempt to save Bertha. Jane and Rochester marry, and live a quiet and happy life together. Jane begins the story with nothing, seems poised to achieve true happiness before losing everything, but ultimately has a happy ending.

Other examples of the rags-to-riches plot structure:

- Cinderella by Charles Perrault

- David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

- Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

- The Once and Future King by T.H. White

- Villette by Charlotte Brontë

- Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw

- Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackery

The Quest Plot in Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

Siddhartha , by Herman Hesse, follows the structure of the "quest" plot. The novel's protagonist, Siddartha, leaves his hometown in search of spiritual enlightenment, accompanied by his friend, Govinda. On their journey, they join a band of holy men who seek enlightenment through self-denial, and later, they study with a group of Bhuddists. Disillusioned with religion, Siddartha leaves Govinda and the Bhuddists behind and takes up a hedonistic lifestyle with the beautiful Kamala. Still unsatisfied with his life, he considers suicide in a river, but instead decides to apprentice himself to the man who runs the ferry boat. By studying the river, Siddhartha eventually obtains enlightenment.

Other examples of the quest plot structure:

- Candide by Voltaire

- Don Quixote by Migel de Cervantes

- A Passage to India by E.M. Forster

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

- Perceval by Chrétien

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling

The "Voyage and Return" Plot in Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston's novel Their Eyes Were Watching God follows what Booker would describe as a voyage and return plot structure. The plot follows the hero, Janie, as she seeks love and happiness. The novel begins and ends in Eatonville, Florida, where Janie was brought up by her grandmother. Janie has three romantic relationships, each better than the last. She marries a man named Logan Killicks on her grandmother's advice, but she finds the marriage stifling and she soon leaves him. Janie's second, more stable marriage to the prosperous Joe Starks lasts 20 years, but Janie does not feel truly loved by him. After Joe dies, she marries Tea Cake, a farm worker who loves, respects, and cherishes her. They move to the Everglades and live there happily for just over a year, when Tea Cake dies of rabies after getting bitten by a dog during a hurricane. Janie mourns Tea Cake's death, but returns to Eatonville with a sense of peace: she has known true love, and she will always carry her memories of Tea Cake with her. Her journey and her return home have made her stronger and wiser.

Other examples of the voyage and return plot structure:

- The Odyssey by Homer

- Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

- Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

- By the Waters of Babylon by Stephen Vincent Benét

Other Helpful Plot Resources

- What Makes a Hero? Check out this awesome video on the hero's journey from Ted-Ed.

- The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations : Visit Wikipedia for an overview of George Polti's theory of dramatic plot structure.

- Why Tragedies Are Alluring : Learn more about Aristotle's tragic structure, ancient Greek and Shakespearean tragedy, and contemporary tragic plots.

- The Wikipedia Page on Plot: A basic but helpful overview of plots.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1929 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,694 quotes across 1929 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Bildungsroman

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Falling Action

- Rising Action

- Tragic Hero

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Red Herring

- Anadiplosis

- Antimetabole

- Slant Rhyme

- Colloquialism

- Flat Character

- Rhyme Scheme

The plot of a story defines the sequence of events that propels the reader from beginning to end. Storytellers have experimented with the plot of a story since the dawn of literature. No matter what genre you write, understanding the possibilities of plot structure, as well as the different types of plot, will help bring your stories to life.

So, what is plot? Is there a difference between plot vs. story? What plot devices can you use to surprise the reader? And how does plot relate to the story itself?

In this article, we go over the elements of plot, different plot structures to use in your work, and the many possibilities of narrative structuring.

But first, what is the plot of a story? Let’s investigate in detail.

Elements of Plot

- Common Plot Structures

What is Plot Without Conflict?

Common plot devices.

- 8 Types of Plot

- Plot-Driven Vs. Character-Driven Stories

- Plot Vs. Story

Plot Definition: What is the Plot of a Story?

The plot of a story is the sequence of events that shape a broader narrative, with every event causing or affecting each other. In other words, story plot is a series of causes-and-effects which shape the story as a whole.

What is plot?: A series of causes-and-effects which shape the story as a whole.

Plot is not merely a story summary: it must include causation. The novelist E. M. Forster sums it up perfectly:

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.” —E. M. Forster

In other words, the premise doesn’t become a plot until the words “of grief” adds causality. Without including “of grief” in the sentence, the queen could have died for any number of reasons, like assassination or suicide. Grief not only provides plot structure to the story, it also introduces what the story’s theme might be.

The plot of a story must include the following elements:

- Causation: one event causes another, and that cause-and-effect unleashes a whole chain of plot points which formulate the story.

- Characters: stories are about people, so a plot must introduce the main players of the plot.

- Conflict: a plot must involve people with competing interests or internal conflicts, because without conflict, there is no story or themes.

Combining these elements of plot creates the structure of the story itself. Let’s take a look at those plot structures now, because there are many different ways to organize the story’s events.

Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot. —Leigh Brackett

Some Common Plot Structures

There are many ways to develop the plot of a story, and writers have been experimenting with plot structures for millennia. Consider the following structures as you attempt to write your own stories, as they may help you find a solution to the problems you encounter in your story writing.

Plot Structures: Aristotle’s Story Triangle

The oldest recorded discussion of plot structures comes from Aristotle’s Poetics (circa 335 B.C.). In Poetics , Aristotle represents the plot of a story as a narrative triangle, suggesting that stories provide linear narratives that resolve certain conflicts in three parts: a beginning, middle, and end.

To Aristotle, the beginning should exist independent of any prior events: it should be a self-sustaining unit of the story without prompting the reader to ask “why?” or “how?” The middle should be a logical continuation of the events from the beginning, expanding upon the story’s conflicts and tragedies. Finally, the end should provide a neat resolution, without suggesting further events.

Obviously, many stories complicate this basic plot triangle, and it lacks some of the finer details of plot structure. One way that Aristotle has been developed further is through Freytag’s Pyramid.

Plot Structures: Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid builds upon Aristotle’s Poetics by expanding the structural elements of plot. This pyramid consists of five discrete parts:

- Exposition: The beginning of the story, introducing main characters, settings , themes, and the author’s own style .

- Rising Action: This begins after the inciting incident , which is the event that kicks off the story’s main conflict. Rising Action follows the cause-and-effect plot points once the main conflict is established.

- Climax: The moment in which the story’s conflict peaks, and we learn the fate of the main characters.

- Falling Action: The main characters react to and contend with the Climax, processing what it means for their lives and futures.

- Denouement: The end of the story, wrapping up any loose ends that haven’t been wrapped up in the Falling Action. Some Denouements are open ended.

For more on Freytag’s Pyramid, check out our article. https://writers.com/freytags-pyramid

Plot Structures: Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc

A further expansion of Freytag’s Pyramid, the 8 Point Arc is Nigel Watts’ contribution to the study of narratology. Watts contends that a story must pass through 8 discrete plot points:

- Stasis: The everyday life of the protagonist , which becomes disrupted by the story’s inciting incident, or “trigger.”

- Trigger: Something beyond the protagonist’s control sets the story’s conflict in motion.

- The quest: Akin to the rising action, the quest is the protagonist’s journey to contend with the story’s conflict.

- Surprise: Unexpected but plausible moments during the quest that complicate the protagonist’s journey. A surprise might be an obstacle, complication, confusion, or internal flaw that the protagonist didn’t predict.

- Critical choice : Eventually, the protagonist must make a complicated, life-altering decision. This decision will reveal the protagonist’s true character, and it will also radically alter the events of the story.

- Climax: The result of the protagonist’s critical choice, the climax determines the consequences of that choice. It is the apex of tension in the story.

- Reversal: This is the protagonist’s reaction to the climax. Reversal should alter the protagonist’s status, whether that status is their place in society, their outlook on life, or their own death.

- Resolution: The return to a new stasis, in which a new life goes forth from the ashes of the story’s conflict and climax.

If the plot of a story passes through each of these moments in order, the author has built a complete narrative.

Watts expands upon this plot structure in his book Write a Novel and Get It Published .

Plot Structures: Save the Cat

The Save the Cat plot structure was developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder. Although it primarily deals with screenplays, it maps out story structure in such a detailed way that its many elements can be incorporated into all types of stories.

Rather than reinvent the wheel, we’ll point you to the great breakdown of Save the Cat, including a worksheet you can use to draft your own story. Find it here, at Reedsy .

Plot Structures: The Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey is a plot structure originally crafted by Joseph Campbell. Campbell argued that the plot of a story has three main acts, with each act corresponding to the necessary journey a hero must undergo in order to be the hero.

Those three parts are: Stage 1) The Departure Act (the hero leaves their everyday life); Stage 2) The Initiation Act (the hero undergoes various conflicts in an unknown land); and Stage 3) The Return Act (the hero returns, radically altered, to their original home).

In his screenwriting textbook The Writer’s Journey , Christopher Vogler expands these three stages into a 12 step process. To Vogler, the hero’s journey must pass through these parts:

The Departure Act

- The Ordinary World: We meet our hero in their mundane, everyday reality.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is confronted with a challenge which, if they accept it, forces them to leave their ordinary world.

- Refusing the Call: Recognizing the dangers of adventure, the hero will, if not reject the call, at least demure or hesitate while considering the many probable ways it will go wrong.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero decides to go on the adventure, but they are much too inexperienced to survive. A mentor accompanies the hero to help them be smart and strong enough for the journey.

The Initiation Act

- Crossing the Threshold: By leaving for their adventure, the hero crosses a liminal threshold. They cannot go back, and if they return home, they won’t return the same.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero enters a strange new world, with unfamiliar rules and dangers. They also encounter allies and enemies that broaden and complicate the story’s conflicts.

- Approach (to the Inmost Cave) : The “inmost cave” is the locus of the journey’s worst dangers—think of the dragon’s lair in Beowulf or the White Witch’s castle in The Chronicles of Narnia . The hero is approaching this cave, though must locate it and build strength.

- Ordeal: This is the hero’s biggest test (thus far). Sometimes the climax (but not always), the ordeal forces the hero to face their biggest fears, and it often occurs when the hero receives unexpected news. This is a low point for the hero.

- Reward: The hero receives whatever reward they gain from their ordeal, whether that reward is a material possession, greater knowledge, someone’s freedom, or the resolution of the hero’s internal conflict.

The Return Act

- The Road Back: The hero ventures back home, though their newfound reward raises additional dangers, many of which stem from the Inmost Cave.

- Resurrection: The main antagonist returns for one final fight against the hero. This is a test of whether the hero has truly learned their lesson and undergone significant character development ; it is also the other climax of the story. The hero comes closest to death here (if they don’t actually die).

- The Return: The elixir is whatever reward the hero accrued, whether that be knowledge or material wealth. Regardless, the hero returns home a changed person, and their return home highlights the many ways in which the hero has changed—both for better and worse.

Plot Structures: Fichtean Curve

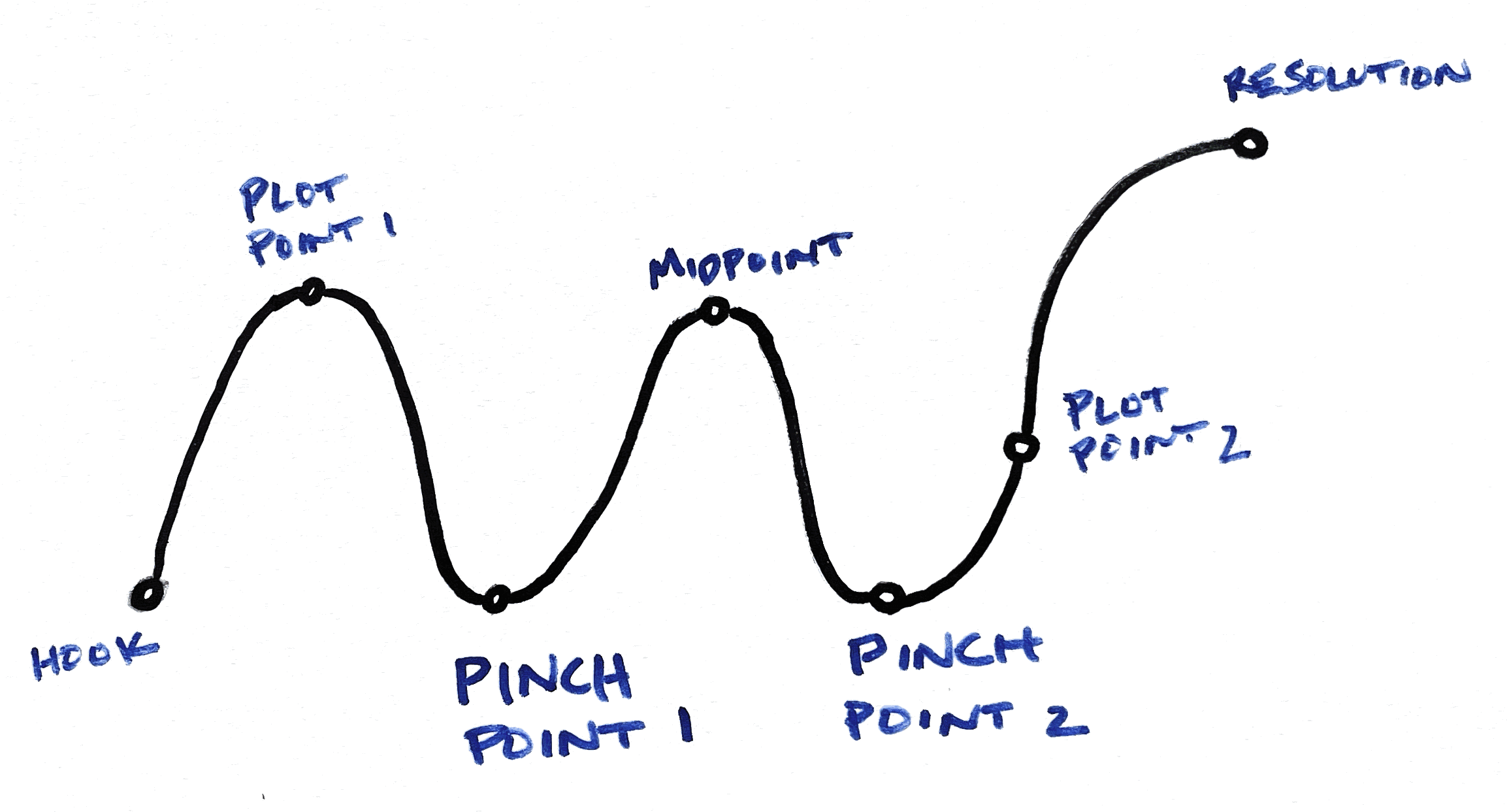

The Fichtean Curve was originally crafted for pulp and mystery stories, though it can certainly apply to stories in other genres. Described extensively by John Gardner in The Art of Fiction , the Fichtean Curve argues that a story plot has three parts: a rising action, a climax, and a falling action.

In the Fichtean Curve, the rising action comprises about ⅔ of the entire story. Moreover, the rising action isn’t linear. Rather, a series of escalating and de-escalating conflicts slowly pushes the story towards its climax.

If you’ve ever read one of Agatha Christie’s murder mysteries, then you’re already familiar with the Fichtean Curve. In Murder on the Orient Express , for example, Hercule Poirot continues to stoke the flames of the story’s many suspects: he uncovers every passenger’s flaws, insecurities, and secrets, each time generating a little more conflict, and each time narrowing down the murderer until the story’s explosive climax.

In a moment, we’ll look at some common plot devices that authors use to keep their stories fresh and engaging. But first, let’s discuss a central element of all plots: conflict. Is it always essential to good storytelling? What is plot without conflict?

First, let’s define conflict. Conflict is not necessarily two characters bickering, although that’s certainly an example. Conflict refers to the opposing forces acting against a character’s goals and interests. Sometimes, that conflict is external: an enemy, bureaucracy, society, etc. Other times, the conflict is internal: traumas, illogical ways of thinking, character flaws, etc.

Typically, conflict is the engine of the story. It’s what incites the inciting incident. It’s what keeps the rising action rising. The climax is the final product of the conflict, and the denouement decides the outcome of that conflict. The plot of a story relies on conflict to keep the pages turning.

So, a word of advice: if you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict. Each scene should stoke a conflict forward, even if the conflict isn’t readily apparent just yet. Anything that doesn’t explore, expand, or resolve the elements of a story’s conflict is likely wasting the reader’s time.

If you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict.

Before we move on, it’s worth noting that the centrality of conflict in plot in literature is a very Western notion. Some forms of storytelling don’t rely on conflict. The Eastern story structure Kishōtenketsu, for example, involves characters reacting to random external situations, rather than generating and resolving their own conflicts. A conflict might be featured in this kind of storytelling, but the story engine is the characters themselves, their own complexities and dilemmas, and how they survive in a world they can’t control.

To learn more about conflict in story plot, check out our article:

What is Conflict in a Story? Definition and Examples

The plot of a story is influenced by many factors. While plot structures give the framework for the story itself, the author must employ plot devices to keep the story moving, otherwise the rising action will never become a climax.

These plot devices ensure that your reader will keep reading, and that your story will deepen and complicate the themes it seeks to engage.

Aristotle’s Plot Devices

In Poetics , Aristotle describes three plot devices which are essential to most stories. These are:

1. Anagnorisis (Recognition)

Luke, I am your father! Anagnorisis is the moment in which the protagonist goes from ignorance to knowledge. Often preceding the story’s climax, anagnorisis is the key piece of information that propels the protagonist into resolving the story’s conflict.

2. Pathos (Suffering)

Aristotle defines pathos as “a destructive or painful action.” This can be physical pain, such as death or severe wounds, but it can also be an emotional or existential pain. Regardless, Aristotle contends that all stories confront extreme pain, and that this pain is essential for the propulsion of the plot. (This is different from the rhetorical device “pathos,” in which a rhetorician seeks to appeal to the audience’s emotions.)

3. Peripeteia (Reversal)

A peripeteia is a moment in which bad fortunes change to good, or good fortunes change to bad. In other words, this is a reversal of the situation. Often accompanied by anagnorisis, peripeteia is often the outcome of the story’s climax, since the climax decides whether the protagonist’s story ends in comedy or tragedy.

Plot Devices for Story Structure

The plot of a story will gain structure from the use of these devices.

Backstory refers to important moments that have occurred prior to the main story. They happen before the story’s exposition, and while they sometimes change the direction of the story, they more often provide historical parallels and key bits of characterization. Sometimes, a story will refer to its own backstory via flashback .

Deus Ex Machina

A deus ex machina occurs when the protagonist’s fate is changed due to circumstances outside of their control. The Gods may intervene, the antagonist may suddenly perish, or the story’s conflict resolves itself. Generally, deus ex machina is viewed as a “cop out” that prevents the protagonist from experiencing the full growth necessary to complete their journey. However, this risky device may pay off, especially in works of comedy or absurdism.

In Media Res

From the Latin “in the middle of things,” a story is “in media res” when it starts in the middle. On Page 1, word 1, the story starts somewhere in the middle of the rising action, hooking the reader in despite the lack of context. Eventually, the story will properly introduce the characters and take us to the beginning of the conflict, but “in media res” is one way to generate immediate interest in the story.

Plot Voucher

A plot voucher is something that is given to the protagonist for later use, except the protagonist doesn’t know yet that they will use it. That “something” might be an item, a piece of information, or even a future allegiance with another person. Many times, a plot voucher is bequeathed before the story’s conflict properly takes shape. For example, in the Harry Potter series, the Resurrection Stone is hidden in Harry’s first golden snitch, making the snitch a plot voucher.

Plot Devices for Complicating the Story

What is the plot of a story, if not complicated? These plot devices bring your readers in for a wild ride.

Cliffhanger

A cliffhanger occurs when the story ends before the climax is resolved. Specifically, the story ends mid-climax so that the reader experiences the height of the story’s tension, but doesn’t see the outcome of the climax and the fate of the protagonist or conflict. Cliffhangers will generally occur when the story is part of a series, though it can also have literary merit. In One Thousand and One Nights , Scheherazade ends her stories on cliffhangers so that the king keeps postponing her execution.

A MacGuffin is a plot device in which the protagonist’s main desire lacks intrinsic value. In other words, the protagonist desires the MacGuffin, which causes the story’s conflict, but the MacGuffin itself is actually valueless. Many times, the protagonist doesn’t even obtain the MacGuffin, because they have learned what lessons they were supposed to learn from the chase. An example is the falcon statuette in The Maltese Falcon . This statuette is never obtained, but it drives the novel’s many murders and double crossings.

Red Herring

A red herring is a distraction device in which the author misleads the reader (or other characters) with seemingly-relevant details. (The MacGuffin is a form of red herring.) Red herrings are primarily found in mystery and suspense stories, as they string the reader down different possibilities while distracting from the truth. Although this plot device can complicate the story and even build symbolism , it can also fracture the reader’s trust in the author, so writers should use it sparingly and wisely. (This is slightly different from the logical fallacy “red herring,” in which irrelevant information is used to distract the reader from a faulty argument.)

For more plot devices and storytelling techniques, take a look at our article The Art of Storytelling.

https://writers.com/the-art-of-storytelling

8 Types of Plot in Literature

Certain types of plot recur throughout literature, especially in genre fiction. These stories build upon the previously mentioned plot devices, and they have their own tropes and archetypes which the author must fill to tell a complete story.

Some, but not all, of the following plots were originally defined by Christopher Booker in his work The Seven Basic Plots . (We’ve omitted some of the plots he mentions if they are rarely seen in contemporary literature.)

The plot of a story might take the following shapes:

1. Plot of a Story: Quest

Often resembling the Hero’s Journey, a quest is a story in which the protagonist sets out from their homeland in search of something. They might be searching for treasure, for love, for the truth, for a new home, or for the solution to a problem. Often accompanied by other allies, and often embarking on this journey with hesitation, the protagonist comes back from their quest stronger, smarter, and irreversibly changed—if they make it back alive.

Examples of the quest include: The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight , and The Harry Potter Series .

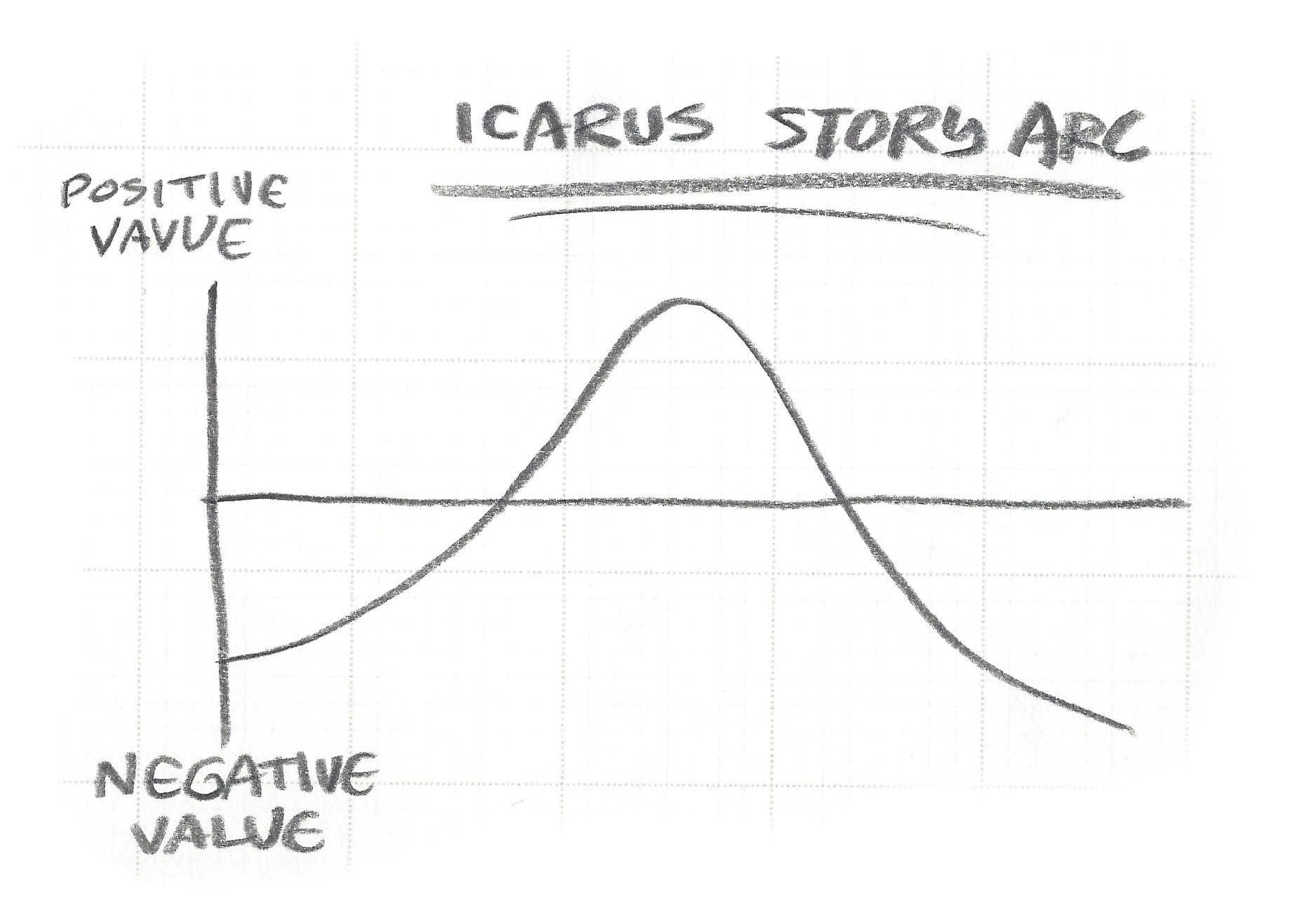

2. Plot of a Story: Tragedy

A tragedy is a story of a well-meaning protagonist who, due to their flaws or shortcomings, fails to resolve the story’s conflict. (The hero’s tragic flaw is known as hamartia .) Tragedies often highlight the terrible circumstances that the protagonist finds themselves in, or the impossible moral quandaries that they must resolve (but don’t). Readers come to love the tragic hero both despite and because of their flaws, and their inability to resolve the conflict often comes as a great moral or personal loss, even resulting in the protagonist’s death.

Examples of the tragedy include: Romeo & Juliet by Shakespeare, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, and Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.

3. Plot of a Story: Rags to Riches

A rags to riches story involves a protagonist who goes from dire poverty to excessive wealth. In addition to navigating issues of class and identity, these stories often showcase the protagonist’s inner world as they adjust to drastically new life circumstances. The plot of a rags to riches story will follow the protagonist’s relationship to wealth, and the things that protagonist chases precisely because of that wealth.

Examples of the rags to riches include: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, The Count of Monte Cristo Alexandre Dumas, and Q & A by Vikas Swarup.

4. Plot of a Story: Story Within a Story

The story within a story, also known as an embedded narrative, one of the less-structured types of plot. Essentially, the author embeds a second story, complete with its own narrative and conflict, to bolster the progression of the main story. Embedded narratives often reflect the themes of the main narratives, but they can also complicate and challenge those themes, providing additional layers of meaning to the story. This is not to be confused with parallel plot, because the story within a story is an invention solely for the sake of advancing the main narrative, whereas a parallel plot has multiple, equally important narratives.

Examples of the story within a story include: The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Hamlet by Shakespeare, Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, Afterworlds by Scott Westerfeld, and Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes.

5. Plot of a Story: Parallel Plot

A parallel plot is a story in which two or more concurrent plots are told side-by-side. Each plot influences the course of the other plot, even if those stories happen on opposite ends of the world. Every narrative that occurs in a parallel plot is equally vital to the story as a whole.

Examples of parallel plot include: Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami, A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, Break the Bodies, Haunt the Bones by Micah Dean Hicks, The Testaments by Margaret Atwood, and In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez.

6. Plot of a Story: Rebellion Against “The One”

A story of rebellion follows a hero who actively resists the oppressive force of an omnipotent antagonist. Despite working tirelessly to defeat that antagonist, the protagonist is ill-equipped to do so as a singular and powerless entity. So, the story often ends with the protagonist submitting to the antagonist, or else perishing altogether.

Examples of rebellion against “The One” include: 1984 by George Orwell, The Hunger Games Series by Suzanne Collins, “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut, and The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood.

7. Plot of a Story: Anticlimax

The anticlimax is a story that details the falling action after a climax has already occurred . In other words, the anticlimax does not have a climax itself: the climax is merely provided as backstory, and the novel is dedicated to the events of the story’s denouement. This not to be confused with the plot device anticlimax, which describes a story’s resolution that is actually incredibly simple.

Examples of the anticlimax include: The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner, Encircling by Carl Frode Tiller, and Oryx & Crake by Margaret Atwood.

8. Plot of a Story: Voyage and Return