Visual Analysis: How to Analyze a Painting and Write an Essay

A visual analysis essay is an entry-level essay sometimes taught in high school and early university courses. Both communications and art history students use visual analysis to understand art and other visual messages. In our article, we will define the term and give an in-depth guide on how to look at a piece of art and write a visual analysis essay. Stay tuned until the end for a handy visual analysis essay example from our graduate paper writing service .

What Is Visual Analysis?

Visual analysis is the process of looking at a piece of visual art (painting, photography, film, etc.) and dissecting it for the artist’s intended meaning and means of execution. In some cases, works are also analyzed for historical significance and their impact on culture, art, politics, and the social consciousness of the time. This article will teach you how to perform a formal analysis of art.

Need Help With Your Visual Analysis?

You only need to send your paper requirements to get help from professional writers.

A visual analysis essay is a type of essay written mostly by students majoring in Art History and Communications. The process of visual analysis can be applied to painting, visual art, journalism, photo-journalism, photography, film, and writing. Works in these mediums are often meant to be consumed for entertainment or informative purposes. Visual analysis goes beyond that, focusing on form, themes, execution, and the compositional elements that make up the work.

Classical paintings are a common topic for a visual analysis essay because of their depth and historical significance. Take the famous Raphael painting Transfiguration. At first glance, it is an attractive image showing a famous scene from the Bible. But a more in-depth look reveals practical painting techniques, relationships between figures, heavy symbolism, and a remarkable choice of colors by the talented Raphael. This deeper look at a painting, a photograph, visual or written art is the process of visual analysis.

Get term paper writer from our professionals. Leave us a message ' write my paper for me ' and we'll deliver the task asap.

Formal Analysis of Art: Who Does It?

Most people who face visual analysis essays are Communication, English, and Art History students. Communications students explore mediums such as theater, print media, news, films, photos — basically anything. Comm is basically a giant, all-encompassing major where visual analysis is synonymous with Tuesday.

Art History students study the world of art to understand how it developed. They do visual analysis with every painting they look it at and discuss it in class.

English Literature students perform visual analysis too. Every writer paints an image in the head of their reader. This image, like a painting, can be clear, or purposefully unclear. It can be factual, to the point, or emotional and abstract like Ulysses, challenging you to search your emotions rather than facts and realities.

How to Conduct Visual Analysis: What to Look For

Whether you study journalism or art, writing a visual analysis essay will be a frequent challenge on your academic journey. The primary principles can be learned and applied to any medium, regardless of whether it’s photography or painting.

For the sake of clarity, we’ve chosen to talk about painting, the most common medium for the formal analysis of art.

In analyzing a painting, there are a few essential points that the writer must know.

- Who is the painter, and what era of art did they belong to? Classical painters depict scenes from the Bible, literature, or historical events (like the burning of Rome or the death of Socrates). Modernists, on the other hand, tend to subvert classical themes and offer a different approach to art. Modernism was born as a reaction to classical painting, therefore analyzing modernist art by the standards of classical art would not work.

- What was the painter’s purpose? Classical painters like Michelangelo were usually hired by the Vatican or by noble families. Michelangelo didn’t paint the Sistine Chapel just for fun; he was paid to do it.

- Who is the audience? Artists like Andy Warhol tried to appeal to the masses. Others like Marcel Duchamp made art for art people, aiming to evolve the art form.

- What is the historical context? Research your artist/painting thoroughly before you write. The points of analysis that can be applied to a Renaissance painter cannot be applied to a Surrealist painter. Surrealism is an artistic movement, and understanding its essence is the key to analyzing any surrealist painting.

Familiarizing yourself with these essential points will give you all the information and context, you need to write a good visual analysis essay.

But visual analysis can go deeper than that — especially when dealing with historic pieces of visual art. Students explore different angles of interpretation, the interplay of colors and themes, how the piece was made and various reactions, and critiques of it. Let’s dig deeper.

A Detailed Process of Analyzing Visual Art

Performing a formal analysis of art is a fundamental skill taught at entry-level art history classes. Students who study art or communications further develop this skill through the years. Not all types of analysis apply to every work of art; every art piece is unique. When performing visual analysis, it’s essential to keep in mind why this particular work of art is important in its own way.

Step 1: General Info

To begin, identify the following necessary information on the work of art and the artist.

- Subject — who or what does this work represent?

- Artist — who is the author of this piece? Refer to them by their last name.

- Date and Provenance — when and where this work of art was made. Is it typical to its historical period or geographical location?

- Past and Current Locations — where was this work was displayed initially, and where is it now?

- Medium and Creation Techniques — what medium was this piece made for and why is it important to that medium? Note which materials were used in its execution and its size.

Step 2: Describe the Painting

Next, describe what the painting depicts or represents. This section will be like an abstract, summarizing all the visible aspects of the piece, painting the image in the reader’s mind. Here are the dominant features to look for in a painting:

- Characters or Figures: who they are and what they represent.

- If this is a classical painting, identify the story or theme depicted.

- If this is an abstract painting, pay attention to shapes and colors.

- Lighting and overall mood of the painting.

- Identify the setting.

Step 3: Detailed Analysis

The largest chunk of your paper will focus on a detailed visual analysis of the work. This is where you go past the basics and look at the art elements and the principles of design of the work.

Art elements deal mostly with the artist’s intricate painting techniques and basics of composition.

- Lines — painters use a variety of lines ranging from straight and horizontal to thick, curved, even implied lines.

- Shapes — shapes can be distinct or hidden in plain sight; note all the geometrical patterns of the painting.

- Use of Light — identify the source of light, or whether the lighting is flat; see whether the painter chooses contrasting or even colors and explain the significance of their choice in relation to the painting.

- Colors — identify how the painter uses color; which colors are primary, which are secondary; what is the tone of the painting (warm or cool?)

- Patterns — are there repeating patterns in the painting? These could be figures as well as hidden textural patterns.

- Use of Space — what kind of perspective is used in the painting; how does the artist show depth (if they do).

- Passage of Time and Motion

Design principles look at the painting from a broader perspective; how the art elements are used to create a rounded experience from an artistic and a thematic perspective.

- Variety and Unity - explore how rich and varied the artists’ techniques are and whether they create a sense of unity or chaos.

- Symmetry or Asymmetry - identify points of balance in the painting, whether it’s patterns, shapes, or use of colors.

- Emphasis - identify the points of focus, both from a thematic and artistic perspective. Does the painter emphasize a particular color or element of architecture?

- Proportions - explain how objects and figures work together to provide a sense of scale, mass, and volume to the overall painting.

- Use of Rhythm - identify how the artist implies a particular rhythm through their techniques and figures.

Seeing as each work of art is unique, be thoughtful in which art elements and design principles you wish to discuss in your essay. Visual analysis does not limit itself to painting and can also be applied to mediums like photography.

Got Stuck While writing your paper?

Count on the support of the professional writers of our essay writing service .

The Structure: How to Write a Visual Analysis Paper

It’s safe to use the five-paragraph essay structure for your visual analysis essay. If you are looking at a painting, take the most important aspects of it that stand out to you and discuss them in relation to your thesis. Structure it with the simple essay structure:

Introduction: An introduction to a visual analysis essay serves to give basic information on the work of art and briefly summarize the points of discussion.

- Give a brief description of the painting: name of artist, year, artistic movement (if necessary), and the artist’s purpose in creating this work.

- Briefly describe what is in the painting.

- Add interesting facts about the artist, painting, or historical period to give your reader some context.

- As in all introductions, don’t forget to include an attention-grabber to get your audience interested in reading your work.

Thesis: In your thesis, state the points of analysis on this work of art which you will discuss in your essay.

Body: Explore the work of art and all of its aspects in detail. Refer to the section above titled “A Detailed Process of Analyzing Visual Art,” which will comprise most of your essay’s body.

Conclusion: After you’ve thoroughly analyzed the painting and the artist’s techniques, give your thoughts and opinions on the work. Your observations should be based on the points of analysis in your essay. Discuss how the art elements and design principles of the artist give the painting meaning and support your observations with facts from your essay.

Citation: Standard citation rules apply to these essays. Use in-text citations when quoting a book, website, journal, or a movie, and include a sources cited page listing your sources. And there’s no need to worry about how to cite a piece of art throughout the text. Explain thoroughly what work of art you’re analyzing in your introduction, and refer to it by name in the body of your essay like this — Transfiguration by Raphael.

If you want a more in-depth look at the classic essay structure, feel free to visit our 5 PARAGRAPH ESSAY blog

Learn From a Visual Analysis Example

Many YouTube videos are analyzing famous paintings like the Death of Socrates, which can be a great art analysis example to go by. But the best way to understand the format and presentation is by looking at a painting analysis essay example done by a scholarly writer. One of our writers has penned an outstanding piece on Leonardo Da Vinci’s La Belle Ferronnière, which you may find below. Use it as a reference point for your visual analysis essay, and you can’t go wrong!

Leonardo da Vinci was an Italian artist born in April 1452 and died in May 1519who lived in the Renaissance era. His fame and popularity were based on his painting sand contribution to the Italian artwork. Leonardo was also an active inventor, a vibrant musician, writer, and scientist as well as a talented sculptor amongst other fields. His various career fields proved that he wanted to know everything about nature. In the book “Leonardo Da Vinci: The Mind of the Renaissance” by Alessandro Vezzosi, it is argued that Leonardo was one of the most successful and versatile artists and anatomists of the Italian renaissance based on his unique artwork and paintings (Vezzosi, p1454). Some of his groundbreaking research in medicine, metal-casting, natural science, architecture, and weaponry amongst other fields have been explored in the book. He was doing all these in the renaissance period in Italy from the 1470s till his death.

Visual analysis essays will appear early in your communications and art history degrees. Learning how to formally analyze art is an essential skill, whether you intend to pursue a career in art or communications.

Before diving into analysis, get a solid historical background on the painter and their life. Analyzing a painting isn’t mere entertainment; one must pay attention to intricate details which the painter might have hidden from plain sight.

We live in an environment saturated by digital media. By gaining the skill of visual analysis, you will not only heighten your appreciation of the arts but be able to thoroughly analyze the media messages you face in your daily life.

Also, don't forget to read summary of Lord of the Flies , and the article about Beowulf characters .

Need Someone to Write Your Paper?

If you read the whole article and still have no idea how to start your visual analysis essay, let a professional writer do this job for you. Contact us, and we’ll write your work for a higher grade you deserve. All ' college essay service ' requests are processed fast.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The Importance of Visual Art

Visual art is a fundamental component of the human experience reflecting the world and the time in which we live. Art can help us understand our history, our culture, our lives, and the experience of others in a manner that cannot be achieved through other means. It can also be a source of inspiration, reflection, and joy.

Visual Art and the American Experience is a testament to the power of art and its connection to our national heritage. Through the exploration of various themes, eras, and artistic styles, the exhibition will serve as a lens through which we can learn about the history of American art and the African American experience.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Visual Arts - List of Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Visual arts encompass a wide range of artistic expressions that are created to be appreciated primarily for their aesthetic or emotional impact. Essays on visual arts could delve into the exploration of different art forms such as painting, sculpture, photography, and digital art. Discussions might also explore the evolution of visual arts, the impact of technological advancements, and the significance of visual arts in cultural and societal contexts. Moreover, analyzing the works of significant artists, the aesthetic principles, and the therapeutic and educational value of engaging in visual arts can provide a comprehensive understanding of the enriching and diverse world of visual arts. A vast selection of complimentary essay illustrations pertaining to Visual Arts you can find at PapersOwl Website. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Visual Arts Analysis: ‘The Calling of Saint Matthew’

In the realm of art history, few works have encapsulated the raw power of divine calling as vividly as Caravaggio's "The Calling of Saint Matthew." This masterpiece, painted between 1599 and 1600, remains a pivotal work that not only exemplifies Caravaggio’s pioneering use of chiaroscuro but also captures an intense and intimate biblical moment. Caravaggio's treatment of this scene from the Gospel of Matthew (9:9) is as dramatic as it is groundbreaking. The painting shows Matthew, a tax collector, sitting […]

Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo

Both Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo belonged to the period names High Renaissance. This beginning in 1490’s and ending in 1527. This period was also referenced as the “Hochrenaissance” in the early 19th century. Leonardo Da Vinci was a well-known painter throughout renaissance. He was not just a painter but also a scientist, inventor, and philosopher. Leonardo was known as an Italian polymath which means he is a person who has a very wide range of expertise in a specific […]

The Art between the Creation of Adam and Mona Lisa

Over the pass hundreds of years, there has been all types of beautiful artwork. More than thousands of artworks are in our museums today that has so much meaning and potential. I would like to talk about and to analyze two types of artwork that I find fascinating Today, the creation of Adam and the Mona Lisa. Although these paintings are fascinating to see there's a lot of meaning behind these artworks such as the elements and principle, they have […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Raphael – Essay

Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael are all considered a great in their own considered fields however, they are all different in their artistic styles. Who was the better artist of the Renaissance and The Late Middle Ages. Leonardo Da Vinci was born on April 15, 1452, Raphael was born on April 6,1520. Michelangelo was born on March 6,1475. All of these artist have different painting styles. Leonardo Da Vinci typically painted with oil paint that he made by hand […]

The Evolution of Art in Mexican Culture

When the world thinks about art we think about paintings and sculptures. But what comes from it? When art is tied with culture you create this everlasting piece of work that has an impact on those who come across it. The significance of each work of art differs from the next. In this research paper we will indulge into the background of art in Mexican culture. Art in Mexico has shifted and continues to modernize because of the customs that […]

Frida Kahlo: a Bibliography and Analysis

"In this research paper I will discuss a brief biography on the artist Frida Kahlo and a cultural and historical context of the two images I chose for this paper. I will focus on a formal analysis on two of Kahlo’s famous paintings, Henry Ford Hospital (Fig 1.) and Self Portrait Along the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States (Fig 2). I will be comparing/analyzing the two paintings based on the subject, space, size, and dimensions. My research […]

Religion and the Renaissance

Religion is not easy to define. Many people have their own definitions of religion based on how they perform their religious beliefs. Religion can be a specific underlying set of beliefs and practices generally agreed upon by a number of persons or faith community. In the dictionaries religion is defined as “the belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power, especially a personal God or gods.” The Florence Cathedral depicts religion through the artifacts inside that have a religious […]

Extended Essay Final Draft By: Esther Natal

Frida Kahlo is now recognized as the greatest twentieth century female artist. Her art explores female themes that are still relevant and timeless, and her work remains iconic for the feminist movement. Frida Kahlo is often iconized by the feminist movement because of the appeal of her images to women, her efforts to claim her Mexican cultural heritage, and her role in expressing evolving gender roles The 6th of July, 1907, in the City of Mexico, Frida Kahlo was born […]

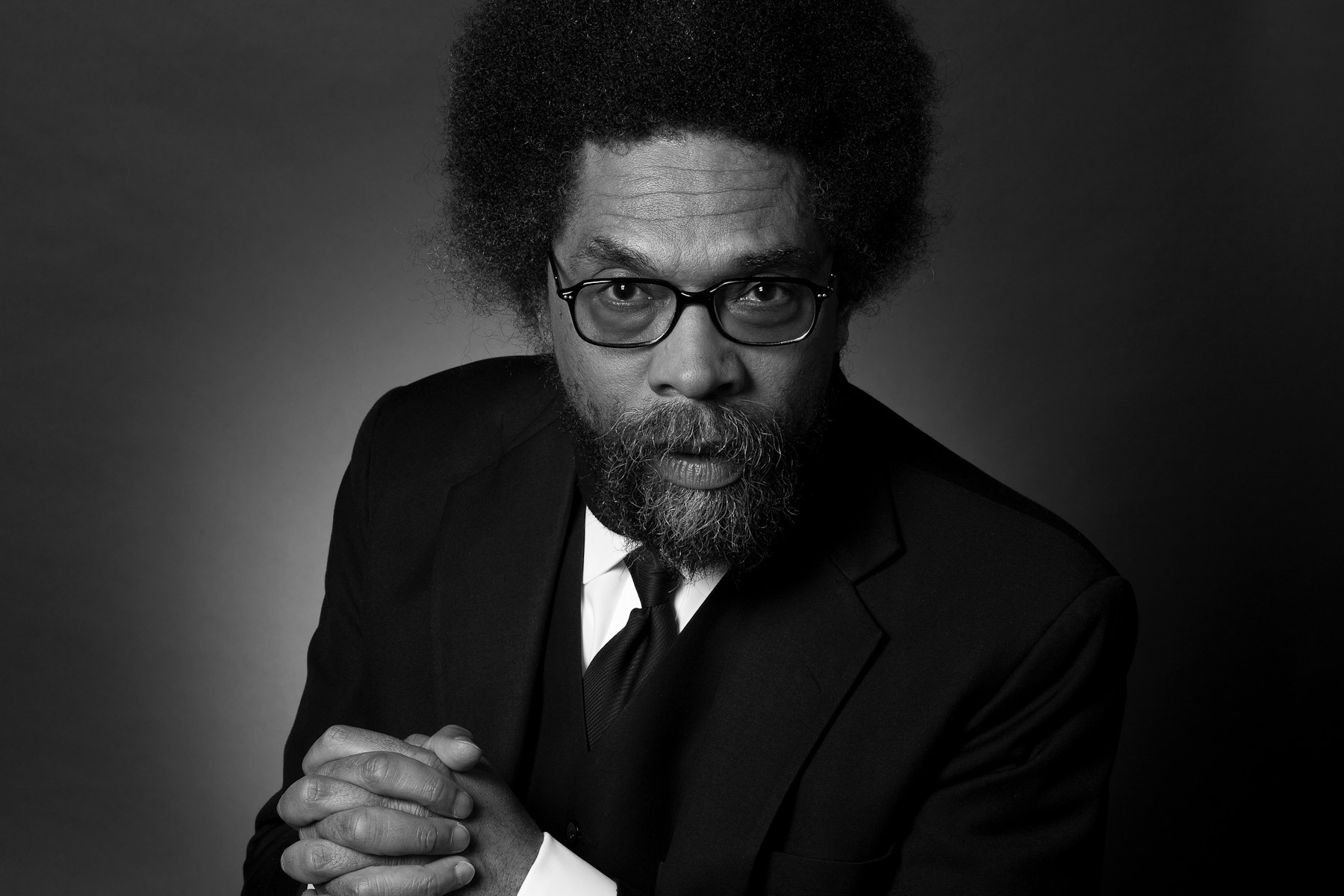

Andy Warhol’s Life and Career

Andy Warhol was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928. His family were immigrants from Carpatho-Rusyn, which is now known as Eastern Slovakia (Andy Warhol's Life). Warhol's family was a religious one, being devout Catholics, they attended mass regularly and kept to their heritage (Andy Warhol's Life). When he was six years old, they moved to a South Oakland neighborhood to be closer to the church they attended, St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic (Andy Warhol's Life). Warhol's childhood was […]

Caravaggio and Caravaggisti in Th-Century Europe

Caravaggio's painting, Death of a Virgin, is painted in a very dark style and he painted Virgin Mary in a very realistic style that is very characteristic of him. Caravaggio painted Virgin Mary like an average modern Roman and he was criticized for portraying her in a very indecent way. Virgin Mary is painted in a style that is usual of the Baroque by having her laying diagonal. Caravaggio spent a lot of time in detailing each aspect of the […]

High Renaissance and the Amazing Artists

"In week two we discussed the High Renaissance and the amazing artists, arts, and styles that were brought up during that time. The High Renaissance was a time period beginning in the 1490’s in the Italian states that truly had amazing artistic production. This time period was greatly dominated by three famous and intellectual artists named Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci. This time period flourished for about 35 years, from the 1490’s to 1527. The High Renaissance originated in […]

Renaissance Art: the Madonna of the Rocks

Interpreting historical paintings is as interesting as they are challenging, more so considering that the artist who made them did not write prefaces to enlighten viewers about the theme of their work and the purpose they served. This omission leaves these works to several, sometimes conflicting interpretations. One such painting is The Madonna of the Rocks by Leonardo da Vinci, which depicts the Virgin Mary, the angel Gabriel, baby Jesus and baby John the Baptist in a cave. I chose […]

1300 Italian Art

During the 1300s, Italian Art made a tremendous impact on a variety of people and still does today. Not only was this a turning point for Italian art because of the Renaissance but also because of the realism and new techniques that were brought about during this time. The art reflected the modernization that this time period was entering. These numerous characteristics, styles, and influential artists all displayed the feelings and emotions of the 1300s. The innovations made in the […]

Art : Mona Lisa

Art is the skill and imagination exercise by the expression of human creativity. We have seen different kinds of art like painting and sculpture that has amazed us throughout our life. There are lots of historical art in this world which were created by some of the legendary artists. Among that Mona Lisa artwork of Leonardo da Vinci is also listed as one of the greatest, famous and amazing artwork of all time. Leonardo da Vinci was one of the […]

Biography of Frida Kahlo

For this assignment, I chose to write about Frida Kahlo. About a year ago, I was not familiarized with many artists except for the well none artist you hear about everywhere, such as Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Leonardo Da Vinci; so when I stumbled upon Frida Kahlo on Google images I was impressed to have found not only a well-known female artist but also a Mexican female artist. Being a child of grown are raised Mexican parents made […]

Leonardo Da Vinci and his Artwork

Leonardo da Vinci is an artist who made paintings, sculptures, architecture and he was also an inventor under military engineering. Leonardo was from a peasant family his mum known as Caterina, and the father's name was Ser Piero. He was born in the town of Vinci on 15th April of the year 1452 (""Leonardo da Vinci"" 56). His parents were no living together and due to the struggles that Leonardo experienced he decided to move to Florence city when he […]

“The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne” by Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci was had an interest in studying landscapes, which can be seen in his painting called, the Annunciation, in which the artist was attentive in producing a persuasive illusion of the nature features of the painting using light and dark oil paints to create dimension (Brown 76). Leonardo’s primary intent was to juxtapose his characters in an environment. In his original painting, Leonardo u create a mountain range using the gradual and irregular grading of blues that fades […]

Effect Science had on the Art during the Three Major Art Periods

"In this paper, I will discuss the effect science had on the art during the three major art periods, Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo. As a part of the discussion, I will examine one art from each art period. One of the greatest artists of the Renaissance period was Leonardo Da Vinci. Leonardo was an Italian polymath. He was great at many disciplines both humanitarian and scientific in nature. He was skilled in drawing, painting, sculpting, carpentry, metallurgy, chemistry, mathematics and […]

Caravaggio a World-renowned Painter

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was a world-renowned painter. Actively painting from 1584 to his controversial death in 1610. Merisi was most renowned for his use of the art technique known as chiaroscuro. Chiaroscuro refers to the use of bold contrasts of light and dark which affect the whole piece, adding volume or solidarity. Many artists and art historians would agree that Caravaggio had a large influence on the Baroque style of painting. The Baroque style is often characterized by "... […]

A Tour of Five Eras

The best representatives of Greek and Roman culture for the Greco-Roman room of the museum are Funerary Crater and Emperor Caracalla, respectively. Funerary Crater, a terra cotta amphora created by an unknown artist in the eighth century BC, is decorated with black-figure images, mainly depicting mythological symbols and scenes (Benton and DiYanni, 2014, p. 38). This fits well with the Greek culture, which was totally permeated by mythological ideas; a vase such as this one would have been used in […]

Frida Kahlo’s Broken Canvas: Pain, Perseverance, and the Quest for Freedom

The artwork includes both elements of design and principles of design. Horizontal lines are found on several areas such as the straps painted onto Frida Kahlo for support and the lines included in the background depicts the terrain as dry and harsh. The lines are also used to divide the sky from the terrain. The shape of Frida Kahlo’s skin, hair, and breasts are soft while other parts in the piece are depicted more concrete and hard-edged such as the […]

Analyzing Changes in the ‘Virgin and Child with Saint Anne’ Painting

A rendition of the renowned painting found in the Louvre that was created by Leonardo da Vinci himself, the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne by Gian Giacomo Capriotti or Sali was painted in the workshop of Leonardo under his direct supervision. Changes done to the painting, such as inclusion of undergrowth, trees, rendering of light, color and alterations of figures, were made purposefully to bring to life Leonardo’s various ideas for the painting that he left unfinished or hidden […]

Mexican Artist – Frida Kahlo

Frida kahlo was one of the most influential Mexican artists. Frida painted self portraits. She was inspired by Mexico’s well liked culture. She painted folk art, gender, race in the mexican society. Frida the well known artist in Mexico died on July 13, 1954. Kahlo was born in Mexico City, Mexico in 1907. Frida went to National Preparatory School. She was one of the few females that went to the school. She joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican […]

Biography of Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo was born in April 15, 1452, Italy, and he died on May 2, 1519, France. While he was growing, he was exposed to Vinci's long standing painting tradition. When Leonardo was about 15 years old, his father apprenticed him to the well-known workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence. As an trainee, Leonardo proved his great talent. One of Leonardo's first big breaks was to paint an angel in""Baptism of Christ."" He was so much better than his master's […]

Every Artist has a Different Muse

The 20th century is a very interesting era, planished with different artists and art movements. One of the greatest art movement was surrealism, it was not only an artistic movement but also a literary one. Surrealism was an important movement because of the end of the World War I and the Mexican revolution. Surrealists—inspired by Sigmund Freud’s theories of dreams and the unconscious—believed insanity was the breaking of the chains of logic, and they represented this idea in their art […]

Painting of Mona Lisa

A painting which doesn't have words but can explain everything just by a view of the true artist. One of the most beautiful works in history is a painting of Mona Lisa by Leonardo in the city Florence between 1503 and 1505. Mona Lisa was beautiful wife of Francesco del Gioconda, but Leonardo never gives the portrait to Francesco. Instead, he kept it with himself. They are the much more profound meaning of the painting some say it is the […]

“A Picture Says a Thousand Words”

A wise man once said, "A picture says a thousand words." I have found one of the best painting ever made in the art world. It none other than the famous "The Mona Lisa." For some people, it is just a painting of a woman, but others it’s like the best romantic painting ever. One of the most beautiful works in history is a painting of Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci in the city of Florence between 1503 and […]

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo Y Calderon

Magdalena Carmene Frida Kahlo y Calderón, otherwise known as Frida Kahlo, was born on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico. She was the daughter of Hungarian Jewish immigrant photographer, Guillermo Kahlo, and Matilde Calderón. Kahlo studied at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, where she was one of thirty-five girls in a student body of two thousand. In 1925, Kahlo was in a traffic accident and her spine and pelvis were fractured. While she recovered she began to paint. In 1929, Kahlo […]

Advances in Arts: Exploring the Evolution from Renaissance to Rococo

Advances in arts and sciences generally go hand in hand, as we have seen from the Classical era to the Modern. This is true especially for the Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo eras. When we think of the arts and science of the Renaissance one man comes to mind before all others, Leonard da Vinci. Scientific expansion during the Baroque era was achieved with a shift towards observation. Scientific expansion during the Baroque era was achieved with a shift towards observation. […]

An Analysis of Great Quattrocento and High Renaissance Art

An interesting tradition among the dining rooms of convents and monasteries in Italy is the depiction of the Last Supper, where Christ administered the Eucharist to his Disciples on the night he was betrayed. Both Andrea del Castagno’s and Leonardo da Vinci’s depictions of the Last Supper are intimate, as monks and nuns dine with Christ and his disciples each evening. With diverse facial expression and hand gesture, Del Castagno’s The Last Supper is indicative in style of the Quattrocento, […]

Related topic

Additional example essays.

- Renaissance Humanism

- Analysis of "The True Cost" Documentary

- Social Media and Body Image

- Just Mercy: Justice in American

- Randy Travis: Beyond the Funeral, a Legacy Revisited

- The Madea Chronicles: An Exploration of Tyler Perry's Cinematic Family Tree

- Colonism in Things Fall Apart

- The short story "The Cask of Amontillado"

- Beowulf and Grendel Comparison

- The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food

- Drunk Driving

- Basketball - Leading the Team to Glory

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: What is Visual Art?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10109

- Pamela Sachant, Peggy Blood, Jeffery LeMieux, & Rita Tekippe

- University System of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

To explore a subject, we need first to define it. Defining art, however, proves elusive. You may have heard it said (or even said it yourself) that “it might be art, but it’s not Art,” which means, “I might not know how to define it, but I know it when I see it.”

Everywhere we look, we see images designed to command our attention, including images of desire, images of power, religious images, images meant to recall memories, and images intended to manipulate our appetites. But are they art?

Some languages do not have a separate word for art. In those cultures, objects tend to be utilitarian in purpose but often include in their design the intent to delight, portray a special status, or commemorate an important event or ritual. Thus, while the objects are not considered art, they do have artistic functions.

1.2.1 Historic Development of the Idea of Art

The idea of art has developmentally progressed from human prehistory to the present day. Changes to the definition of art over time can be seen as attempts to resolve problems with earlier definitions. The ancient Greeks saw the goal of visual art as copying, or mimesis. Nineteenth-century art theorists promoted the idea that art is communication: it produces feelings in the viewer. In the early twentieth century, the idea of significant form, the quality shared by aesthetically pleasing objects, was proposed as a definition of art. Today, many artists and thinkers agree with the institutional theory of art, which shifts focus from the work of art itself to who has the power to decide what is and is not art. While this progression of definitions of art is not exhaustive, it is instructive.

1.2.1.1 Mimesis

The ancient Greek definition of art as mimesis , or imitation of the real world, appears in the myth of Zeuxis and Parhassios, rival painters from ancient Greece in the late fifth century BCE who competed for the title of greatest artist. (Figure 1.2) Zeuxis painted a bowl of grapes that was so lifelike that birds came down to peck at the image of fruit. Parhassios was unimpressed with this achievement. When viewing Parhassios’s work, Zeuxis, on his part, asked that the curtain over the painting be drawn back so he could see his rival’s work more clearly. Parhassios declared himself the victor because the curtain was the painting, and while Zeuxis fooled the birds with his work, Parhassios fooled a thinking human being—a much more difficult feat.

Figure 1.2 Zeuxis conceding defeat: "I have deceived the birds, but Parhassios has deceived Zeuxis." Artist: Joachim von Sandrart; engraving by Johann Jakob von Sandrart Author: (Public Domain; “Fae”).

The ancient Greeks felt that the visual artist’s goal was to copy visual experience. This approach appears in the realism of ancient Greek sculpture and pottery. We must sadly note that, due to the action of time and weather, no paintings from ancient Greek artists exist today. We can only surmise their quality based on tales such as that of Zeuxis and Parhassios, the obvious skill in ancient Greek sculpture, and in drawings that survive on ancient Greek pottery.

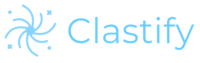

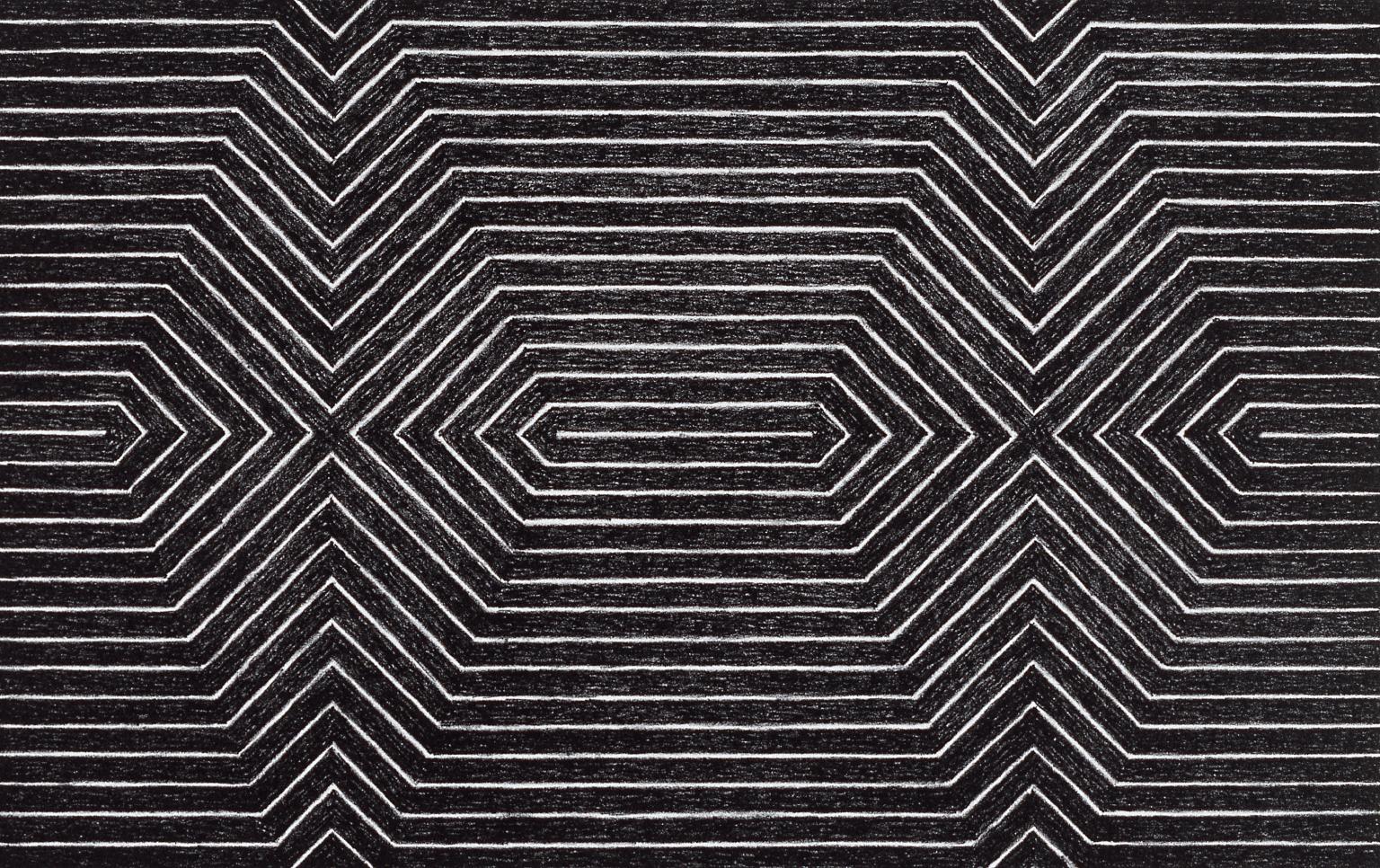

This definition of art as copying reality has a problem, though. Jackson Pollock (1912-1956, USA), a leader in the New York School of the 1950’s, intentionally did not copy existing objects in his art. (Figure 1.3) While painting these works, Pollock and his fellow artists would consciously avoid making marks or passages that resembled recognizable objects. They succeeded at making artwork that did not copy anything, thus demonstrating that the ancient Greek view of art as mimesis—simple copying—does not sufficiently define art.

Figure 1.3 Left: The She-Wolf; Right: Gothic, Artist: Jackson Pollock, Author: (CC BY-SA 4.0; "Group de Besanez")

1.2.1.2 Communication

A later attempt at defining art comes from the nineteenth-century Russian author Leo Tolstoy. Tolstoy wrote on many subjects, and is the author of the great novel War and Peace (1869). He was also an art theorist. He proposed that art is the communication of feeling , stating, “Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one man consciously by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that others are infected by these feelings and also experience them.”1

This definition does not succeed because it is impossible to confirm that the feelings of the artist have been successfully conveyed to another person. Further, suppose an artist created a work of art that no one else ever saw. Since no feeling had been communicated through it, would it still be a work of art? The work did not “hand on to others” anything at all because it was never seen. Therefore, it would fail as art according to Tolstoy’s definition.

1 Leo Tolstoy, What is Art? And Essays on Art, trans. Aylmer Maude (London: Oxford University Press, 1932), 123.

1.2.1.3 Significant Form

To address these limitations of existing definitions of art, in 1913 English art critic Clive Bell proposed that art is significant form , or the “quality that brings us aesthetic pleasure.” Bell stated, “to appreciate a work of art we need bring with us nothing but a sense of form and colour.”2 In Bell’s view, the term “form” simply means line, shape, mass, as well as color. Significant form is the collection of those elements that rises to the level of your awareness and gives you noticeable pleasure in its beauty. Unfortunately, aesthetics , pleasure in the beauty and appreciation of art, are impossible to measure or reliably define. What brings aesthetic pleasure to one person may not affect another. Aesthetic pleasure exists only in the viewer, not in the object. Thus significant form is purely subjective. While Clive Bell did advance the debate about art by moving it away from requiring strict representation, his definition gets us no closer to understanding what does or does not qualify as an art object.

1.2.1.4 Art world

One definition of art widely held today was first promoted in the 1960s by American philosophers George Dickie and Arthur Danto, and is called the institutional theory of art, or the “Artworld” theory. In the simplest version of this theory, art is an object or set of conditions that has been designated as art by a “person or persons acting on behalf of the artworld,” and the artworld is a “complex field of forces” that determine what is and is not art.3 Unfortunately, this definition gets us no further along because it is not about art at all! Instead, it is about who has the power to define art, which is a political issue, not an aesthetic one.

2 Clive Bell, “Art and Significant Form,” in Art (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1913), 2

3 George Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974), 464.

1.2.2 Definition of Art

We each perceive the world from our own position or perspective and from that perception we make a mental image of the world. Science is the process of turning perceptions into a coherent mental picture of the universe through testing and observation. (Figure 1.4) Science moves concepts from the world into the mind. Science is vitally important because it allows us to understand how the world works and to use that understanding to make good predictions. Art is the other side of our experience with the world. Art moves ideas from the mind into the world .

Figure 1.4 Perception: Art and Science, Author: Jeffrey LeMieux, (CC BY-SA 4.0)

We need both art and science to exist in the world. From our earliest age, we both observe the world and do things to change it. We are all both scientists and artists. Every human activity has both a science (observation) and an art (expression) to it. Anyone who has participated in the discipline of Yoga, for example, can see that even something as simple as breathing has both an art and a science to it.

This definition of art covers the wide variety of objects that we see in museums, on social media, or even in our daily walk to work. But this definition of art is not enough. The bigger question is: what art is worthy of our attention, and how do we know when we have found it? Ultimately, each of us must answer that question for ourselves.

But we do have help if we want it. People who have made a disciplined study of art can offer ideas about what art is important and why. In the course of this text, we will examine some of those ideas about art. Due to the importance of respecting the individual, the decision about what art is best must belong to the individual. We ask only that the student understand the ideas as presented.

When challenged with a question or problem about what is best, we first ask, “What do I personally know about it?” When we realize our personal resources are limited, we might ask friends, neighbors, and relatives what they know. In addition to these important resources, the educated person can refer to a larger body of possible solutions drawn from a study of the history of literature, philosophy, and art: What did the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley say about truth in his essay Defense of Poetry (1840)? (Figure 1.5) What did the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau claim about human nature in his treatise Emile or On Education (1762)? (Figure 1.6) What did Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675, Netherlands) show us about the quiet dignity of the domestic space in his painting Woman Holding a Balance? (Figure 1.7) Through experiencing these works of art and literature, our ideas about such things can be tested and validated or found wanting.

Figure 1.5 Portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Artist: Alfred Clint, Author: (Public Domain; "Dcoetzee"). Figure 1.6 Portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Artist: Maurice Quentin de la Tour, Author: (Public Domain; "Maarten van Vilet"). Figure 1.7 Woman Holding a Balance, Artist: Johannes Vermeer, Author: (Public Domain; " DcoetzeeBot")

We will examine works of visual art from a diverse range of cultures and periods. The challenge for you as the reader is to increase your ability to interpret works of art through the use of context, visual dynamics, and introspection, and to integrate them into a coherent worldview. The best outcome of an encounter with art is an awakening of the mind and spirit to a new point of view. A mind stretched beyond itself never returns to its original dimension.

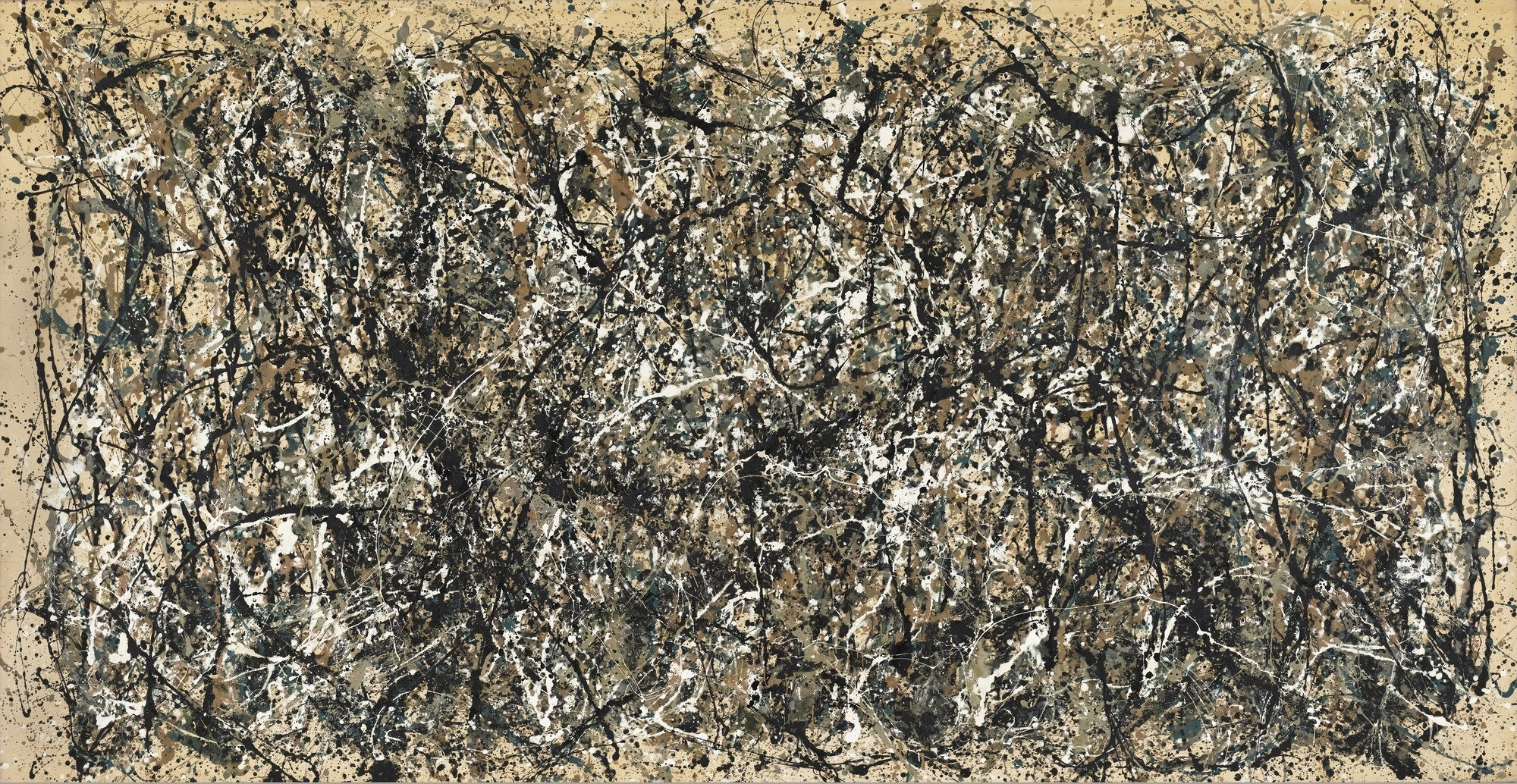

1.2.3 The Distinction of Fine Art

From our definition of art proposed above, it would seem that craft and fine art are indistinguishable as both come from the mind into the world. But the distinction between craft and art is real and important. This distinction is most commonly understood as one based on the use or end purpose of an object, or as an effect of the material used. Clay, textiles, glass, and jewelry were long considered the province of craft, not art. If an object’s intended use was a part of daily living, then it was generally thought to be the product of craft, not fine art. But many objects originally intended to be functional, such as quilts, are now thought to qualify as fine art. (Figure 1.8)

Figure 1.8 Quilt, Artist: Lucy Mingo, Author: (CC BY-SA 4.0, " Billvolckening")

So what could be the difference between art and craft? Anyone who has been exposed to training in a craft such as carpentry or plumbing recognizes that craft follows a formula, that is, a set of rules that govern not only how the work is to be conducted but also what the outcome of that work must be. The level of craft is judged by how closely the end product matches the pre-determined outcome. We want our houses to stand and water to flow when we turn on our faucets. Fine art, on the other hand, results from a free and open-ended exploration that does not depend on a pre-determined formula for its outcome or validity. Its outcome is surprising and original. Almost all fine art objects are a combination of some level both of craft and art. Art stands on craft, but goes beyond it.

1.2.4 Why Art Matters

American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer is considered a “father of the atomic bomb” for the role he played in developing nuclear weapons as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II (1939-1945). (Figure 1.9) Upon completion of the project, quoting from the Hindu epic tale Bhagavad Gita, he stated, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Clearly, Oppenheimer had read more than physics texts in his education, which fit him well for his important role during World War II.

Figure 1.9 J. Robert Oppenheimer, Author: Los Alamos National Laboratory, (Public Domain)

When we train in mathematics and the sciences, for example, we become very powerful. Power can be used well or badly. Where in our schools is the coursework on how to use power wisely? Today a liberal arts college education requires students to survey the arts and history of human cultures in order to examine a wide range of ideas about wisdom and to humanize the powerful. With that in mind, in every course taken in the university, it is hoped that you will recognize the need to couple your increasing intellectual power with a study of what is thought to be wisdom, and to view each educational experience in the humanities as part of the search for what is better in ourselves and our communities.

This text is not intended to determine what is or is not good art and why it matters. Rather, the point of this text is to equip you with intellectual tools that will enable you to analyze, decipher, and interpret works of art as bearers of meaning, to make your own decisions about the merit of those works, and then usefully to integrate those decisions into your daily lives.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 October 2017

The visual essay and the place of artistic research in the humanities

- Remco Roes 1 &

- Kris Pint 1

Palgrave Communications volume 3 , Article number: 8 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

9718 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Archaeology

- Cultural and media studies

What could be the place of artistic research in current contemporary scholarship in the humanities? The following essay addresses this question while using as a case study a collaborative artistic project undertaken by two artists, Remco Roes (Belgium) and Alis Garlick (Australia). We argue that the recent integration of arts into academia requires a hybrid discourse, which has to be distinguished both from the artwork itself and from more conventional forms of academic research. This hybrid discourse explores the whole continuum of possible ways to address our existential relationship with the environment: ranging from aesthetic, multi-sensorial, associative, affective, spatial and visual modes of ‘knowledge’ to more discursive, analytical, contextualised ones. Here, we set out to defend the visual essay as a useful tool to explore the non-conceptual, yet meaningful bodily aspects of human culture, both in the still developing field of artistic research and in more established fields of research. It is a genre that enables us to articulate this knowledge, as a transformative process of meaning-making, supplementing other modes of inquiry in the humanities.

Introduction

In Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (2011), Tim Ingold defines anthropology as ‘a sustained and disciplined inquiry into the conditions and potentials of human life’ (Ingold, 2011 , p. 9). For Ingold, artistic practice plays a crucial part in this inquiry. He considers art not merely as a potential object of historical, sociological or ethnographic research, but also as a valuable form of anthropological inquiry itself, providing supplementary methods to understand what it is ‘to be human’.

In a similar vein, Mark Johnson’s The meaning of the body: aesthetics of human understanding (2007) offers a revaluation of art ‘as an essential mode of human engagement with and understanding of the world’ (Johnson, 2007 , p. 10). Johnson argues that art is a useful epistemological instrument because of its ability to intensify the ordinary experience of our environment. Images Footnote 1 are the expression of our on-going, complex relation with an inner and outer environment. In the process of making images of our environment, different bodily experiences, like affects, emotions, feelings and movements are mobilised in the creation of meaning. As Johnson argues, this happens in every process of meaning-making, which is always based on ‘deep-seated bodily sources of human meaning that go beyond the merely conceptual and propositional’ (Ibid., p. 11). The specificity of art simply resides in the fact that it actively engages with those non-conceptual, non-propositional forms of ‘making sense’ of our environment. Art is thus able to take into account (and to explore) many other different meaningful aspects of our human relationship with the environment and thus provide us with a supplementary form of knowledge. Hence Ingold’s remark in the introduction of Making: anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture (2013): ‘Could certain practices of art, for example, suggest new ways of doing anthropology? If there are similarities between the ways in which artists and anthropologists study the world, then could we not regard the artwork as a result of something like an anthropological study, rather than as an object of such study? […] could works of art not be regarded as forms of anthropology, albeit ‘written’ in non-verbal media?’ (Ingold, 2013 , p. 8, italics in original).

And yet we would hesitate to unreservedly answer yes to these rhetorical questions. For instance, it is true that one can consider the works of Francis Bacon as an anthropological study of violence and fear, or the works of John Cage as a study in indeterminacy and chance. But while they can indeed be seen as explorations of the ‘conditions and potentials of human life’, the artworks themselves do not make this knowledge explicit. What is lacking here is the logos of anthropology, logos in the sense of discourse, a line of reasoning. Therefore, while we agree with Ingold and Johnson, the problem remains how to explicate and communicate the knowledge that is contained within works of art, how to make it discursive ? How to articulate artistic practice as an alternative, yet valid form of scholarly research?

Here, we believe that a clear distinction between art and artistic research is necessary. The artistic imaginary is a reaction to the environment in which the artist finds himself: this reaction does not have to be conscious and deliberate. The artist has every right to shrug his shoulders when he is asked for the ‘meaning’ of his work, to provide a ‘discourse’. He can simply reply: ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I do not want to know’, as a refusal to engage with the step of articulating what his work might be exploring. Likewise, the beholder or the reader of a work of art does not need to learn from it to appreciate it. No doubt, he may have gained some understanding about ‘human existence’ after reading a novel or visiting an exhibition, but without the need to spell out this knowledge or to further explore it.

In contrast, artistic research as a specific, inquisitive mode of dealing with the environment requires an explicit articulation of what is at stake, the formulation of a specific problem that determines the focus of the research. ‘Problem’ is used here in the neutral, etymological sense of the word: something ‘thrown forward’, a ‘hindrance, obstacle’ (cf. probleima , Liddell-Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon). A body-in-an-environment finds something thrown before him or her, an issue that grabs the attention. A problem is something that urges us to explore a field of experiences, the ‘potentials of human life’ that are opened up by a work of art. It is often only retroactively, during a second, reflective phase of the artistic research, that a formulation of a problem becomes possible, by a selection of elements that strikes one as meaningful (again, in the sense Johnson defines meaningful, thus including bodily perceptions, movements, affects, feelings as meaningful elements of human understanding of reality). This process opens up, to borrow a term used by Aby Warburg, a ‘Denkraum’ (cf. Gombrich, 1986 , p. 224): it creates a critical distance from the environment, including the environment of the artwork itself: this ‘space for thought’ allows one to consciously explore a specific problem. Consciously here does not equal cerebral: the problem is explored not only in its intellectual, but also in its sensual and emotional, affective aspects. It is projected along different lines in this virtual Denkraum , lines that cross and influence each other: an existential line turns into a line of form and composition; a conceptual line merges into a narrative line, a technical line echoes an autobiographical line. There is no strict hierarchy in the different ‘emanations’ of a problem. These are just different lines contained within the work that interact with each other, and the problem can ‘move’ from one line to another, develop and transform itself along these lines, comparable perhaps to the way a melody develops itself when it is transposed to a different musical scale, a different musical instrument, or even to a different musical genre. But, however, abstract or technical one formulates a problem, following Johnson we argue that a problem is always a translation of a basic existential problem, emerging from a specific environment. We fully agree with Johnson when he argues that ‘philosophy becomes relevant to human life only by reconnecting with, and grounding itself in, bodily dimensions of human meaning and value. Philosophy needs a visceral connection to lived experience’ (Johnson, 2007 , p. 263). The same goes for artistic research. It too finds its relevance in the ‘visceral connection’ with a specific body, a specific situation.

Words are one way of disclosing this lived experience, but within the context of an artistic practice one can hardly ignore the potential for images to provide us with an equally valuable account. In fact, they may even prove most suited to establish the kind of space that comes close to this multi-threaded, embodied Denkraum . In order to illustrate this, we would like to present a case study, a short visual ‘essay’ (however, since the scope of four spreads offers only limited space, it is better to consider it as the image-equivalent of a short research note).

Case study: step by step reading of a visual essay

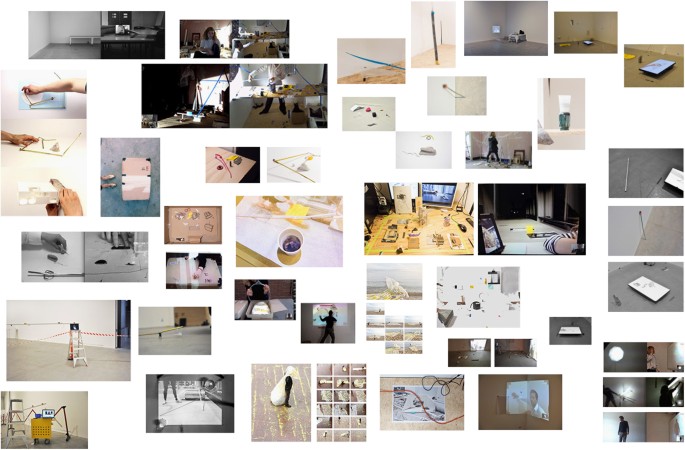

The images (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) form a short visual essay based on a collaborative artistic project 'Exercises of the man (v)' that Remco Roes and Alis Garlick realised for the Situation Symposium at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Melbourne in 2014. One of the conceptual premises of the project was the communication of two physical ‘sites’ through digital media. Roes—located in Belgium—would communicate with Garlick—in Australia—about an installation that was to be realised at the physical location of the exhibition in Melbourne. Their attempts to communicate (about) the site were conducted via e-mail messages, Skype-chats and video conversations. The focus of these conversations increasingly distanced itself from the empty exhibition space of the Design Hub and instead came to include coincidental spaces (and objects) that happened to be close at hand during the 3-month working period leading up to the exhibition. The focus of the project thus shifted from attempting to communicate a particular space towards attempting to communicate the more general experience of being in(side) a space. The project led to the production of a series of small in-situ installations, a large series of video’s and images, a book with a selection of these images as well as texts from the conversations, and the final exhibition in which artefacts that were found during the collaborative process were exhibited. A step by step reading of the visual argument contained within images of this project illustrates how a visual essay can function as a tool for disclosing/articulating/communicating the kind of embodied thinking that occurs within an artistic practice or practice-based research.

Figure 1 shows (albeit in reduced form) a field of photographs and video stills that summarises the project without emphasising any particular aspect. Each of the Figs. 2 – 5 isolate different parts of this same field in an attempt to construct/disclose a form of visual argument (that was already contained within the work). In the final part of this essay we will provide an illustration of how such visual sequences can be possibly ‘read’.

First image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

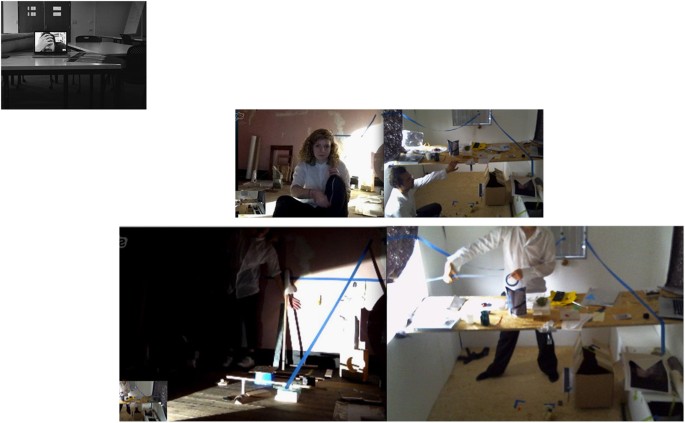

Second image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

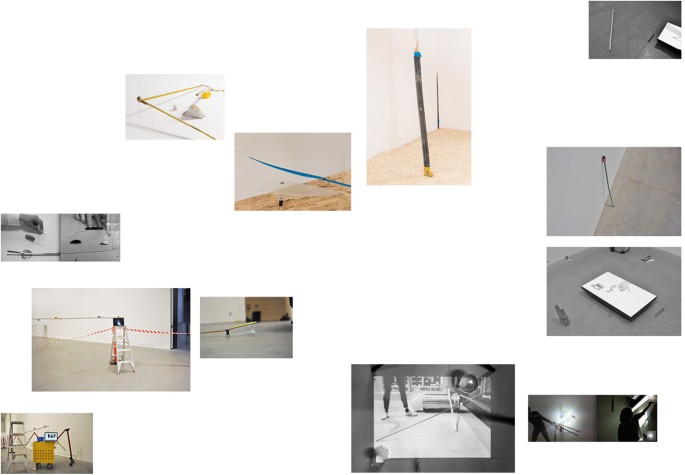

Third image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

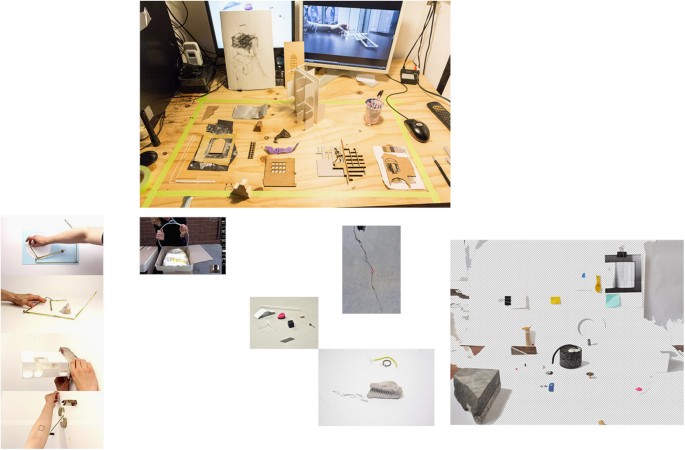

Fourth image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Fifth image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Figure 1 is a remnant of the first step that was taken in the creation of the series of images: significant, meaningful elements in the work of art are brought together. At first, we quite simply start by looking at what is represented in the pictures, and how they are presented to us. This act of looking almost inevitably turns these images into a sequence, an argument. Conditioned by the dominant linearity of writing, including images (for instance in a comic book) one ‘reads’ the images from left to right, one goes from the first spread to the last. Just like one could say that a musical theme or a plot ‘develops’, the series of images seem to ‘develop’ the problem, gradually revealing its complexity. The dominance of this viewing code is not to be ignored, but is of course supplemented by the more ‘holistic’ nature of visual perception (cf. the notion of ‘Gestalt’ in the psychology of perception). So unlike a ‘classic’ argumentation, the discursive sequence is traversed by resonance, by non-linearity, by correspondences between elements both in a single image and between the images in their specific positioning within the essay. These correspondences reveal the synaesthetic nature of every process of meaning-making: ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual and potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences. In pragmatist lingo, the meaning of something is a matter of how it connects to what has gone before and what it entails for present or future experiences and actions’ (Johnson, 2007 , p. 265). The images operate in a similar way, by bringing together different actions, affects, feelings and perceptions into a complex constellation of meaningful elements that parallel each other and create a field of resonance. These connections occur between different elements that ‘disturb’ the logical linearity of the discourse, for instance by the repetition of a specific element (the blue/yellow opposition, or the repetition of a specific diagonal angle).

Confronted with these images, we are now able to delineate more precisely the problem they express. In a generic sense we could formulate it as follows: how to communicate with someone who does not share my existential space, but is nonetheless visually and acoustically present? What are the implications of the kind of technology that makes such communication possible, for the first time in human history? How does it influence our perception and experience of space, of materiality, of presence?

Artistic research into this problem explores the different ways of meaning-making that this new existential space offers, revealing the different conditions and possibilities of this new spatiality. But it has to be stressed that this exploration of the problem happens on different lines, ranging from the kinaesthetic perception to the emotional and affective response to these spaces and images. It would, thus, be wrong to reduce these experiences to a conceptual framework. In their actions, Roes and Garlick do not ‘make a statement’: they quite simply experiment with what their bodies can do in such a hybrid space, ‘wandering’ in this field of meaningful experiences, this Denkraum , that is ‘opened up’: which meaningful clusters of sensations, affects, feelings, spatial and kinaesthetic qualities emerge in such a specific existential space?

In what follows, we want to focus on some of these meaningful clusters. As such, these comments are not part of the visual essay itself. One could compare them to ‘reading remarks’, a short elaboration on what strikes one as relevant. These comments also do not try to ‘crack the code’ of the visual material, as if they were merely a visual and/or spatial rebus to be solved once and for all (‘ x stands for y’ ). They rather attempt to engage in a dialogue with the images, a dialogue that of course does not claim to be definitive or exhaustive.

The constellation itself generates a sense of ‘lacking’: we see that there are two characters intensely collaborating and interacting with each other, while never sharing the same space. They are performing, or watching the other perform: drawing a line (imaginary or physically), pulling, wrapping, unpacking, watching, framing, balancing. The small arrangements, constructions or compositions that are made as a result of these activities are all very fragile, shaky and their purpose remains unclear. Interaction with the other occurs only virtually, based on the manipulation of small objects and fragments, located in different places. One of the few materials that eventually gets physically exported to the other side, is a kind of large plastic cover. Again, one should not ‘read’ the picture of Roes with this plastic wrapped around his head as an expression, a ‘symbol’ of individual isolation, of being wrapped up in something. It is simply the experience of a head that disappears (as a head appears and disappears on a computer screen when it gets disconnected), and the experience of a head that is covered up: does it feel like choking, or does it provide a sense of shelter, protection?

A different ‘line’ operates simultaneously in the same image: that of a man standing on a double grid: the grid of the wet street tiles and an alternative, oblique grid of colourful yellow elements, a grid which is clearly temporal, as only the grid of the tiles will remain. These images are contrasted with the (obviously staged) moment when the plastic arrives at ‘the other side’: the claustrophobia is now replaced with the openness of the horizon, the presence of an open seascape: it gives a synaesthetic sense of a fresh breeze that seems lacking in the other images.

In this case, the contrast between the different spaces is very clear, but in other images we also see an effort to unite these different spaces. The problem can now be reformulated, as it moves to another line: how to demarcate a shared space that is both actual and virtual (with a ribbon, the positioning of a computer screen?), how to communicate with each other, not only with words or body language, but also with small artefacts, ‘meaningless’ junk? What is the ‘common ground’ on which to walk, to exchange things—connecting, lining up with the other? And here, the layout of the images (into a spread) adds an extra dimension to the original work of art. The relation between the different bodies does now not only take place in different spaces, but also in different fields of representation: there is the space of the spread, the photographed space and in the photographs, the other space opened up by the computer screen, and the interaction between these levels. We see this in the Fig. 3 where Garlick’s legs are projected on the floor, framed by two plastic beakers: her black legging echoing with the shadows of a chair or a tripod. This visual ‘rhyme’ within the image reveals how a virtual presence interferes with what is present.

The problem, which can be expressed in this fundamental opposition between presence/absence, also resonates with other recurring oppositions that rhythmically structure these images. The images are filled with blue/yellow elements: blue lines of tape, a blue plexi form, yellow traces of paint, yellow objects that are used in the video’s, but the two tones are also conjured up by the white balance difference between daylight and artificial light. The blue/yellow opposition, in turn, connects with other meaningful oppositions, like—obviously—male/female, or the same oppositional set of clothes: black trousers/white shirt, grey scale images versus full colour, or the shadow and the bright sunlight, which finds itself in another opposition with the cold electric light of a computer screen (this of course also refers to the different time zones, another crucial aspect of digital communication: we do not only not share the same place, we also do not share the same time).

Yet the images also invite us to explore certain formal and compositional elements that keep recurring. The second image, for example, emphasises the importance placed in the project upon the connecting of lines, literally of lining up. Within this image the direction and angle of these lines is ‘explained’ by the presence of the two bodies, the makers with their roles of tape in hand. But upon re-reading the other spreads through this lens of ‘connecting lines’ we see that this compositional element starts to attain its own visual logic. Where the lines in image 2 are literally used as devices to connect two (visual) realities, they free themselves from this restricted context in the other images and show us the influence of circumstance and context in allowing for the successful establishing of such a connection.

In Fig. 3 , for instance, we see a collection of lines that have been isolated from the direct context of live communication. The way two parts of a line are manually aligned (in the split-screens in image 2) mirrors the way the images find their position on the page. However, we also see how the visual grammar of these lines of tape is expanded upon: barrier tape that demarcates a working area meets the curve of a small copper fragment on the floor of an installation, a crack in the wall follows the slanted angle of an assembled object, existing marks on the floor—as well as lines in the architecture—come into play. The photographs widen the scale and angle at which the line operates: the line becomes a conceptual form that is no longer merely material tape but also an immaterial graphical element that explores its own argument.

Figure 4 provides us with a pivotal point in this respect: the cables of the mouse, computer and charger introduce a certain fluidity and uncontrolled motion. Similarly, the erratic markings on the paper show that an author is only ever partially in control. The cracked line in the floor is the first line that is created by a negative space, by an absence. This resonates with the black-stained edges of the laser-cut objects, laid out on the desktop. This fourth image thus seems to transform the manifestation of the line yet again; from a simple connecting device into an instrument that is able to cut out shapes, a path that delineates a cut, as opposed to establishing a connection. The circle held up in image 4 is a perfect circular cut. This resonates with the laser-cut objects we see just above it on the desk, but also with the virtual cuts made in the Photoshop image on the right. We can clearly see how a circular cut remains present on the characteristic grey-white chessboard that is virtual emptiness. It is evident that these elements have more than just an aesthetic function in a visual argumentation. They are an integral part of the meaning-making process. They ‘transpose’ on a different level, i.e., the formal and compositional level, the central problem of absence and presence: it is the graphic form of the ‘cut’, as well as the act of cutting itself, that turns one into the other.

Concluding remarks

As we have already argued, within the frame of this comment piece, the scope of the visual essay we present here is inevitably limited. It should be considered as a small exercise in a specific genre of thinking and communicating with images that requires further development. Nonetheless, we hope to have demonstrated the potentialities of the visual essay as a form of meaning-making that allows the articulation of a form of embodied knowledge that supplements other modes of inquiry in the humanities. In this particular case, it allows for the integration of other meaningful, embodied and existential aspects of digital communication, unlikely to be ‘detected’ as such by an (auto)ethnographic, psychological or sociological framework.

The visual essay is an invitation to other researchers in the arts to create their own kind of visual essays in order to address their own work of art or that of others: they can consider their artistic research as a valuable contribution to the exploration of human existence that lies at the core of the humanities. But perhaps it can also inspire scholars in more ‘classical’ domains to introduce artistic research methods to their toolbox, as a way of taking into account the non-conceptual, yet meaningful bodily aspects of human life and human artefacts, this ‘visceral connection to lived experience’, as Johnson puts it.

Obviously, a visual essay runs the risk of being ‘shot by both sides’: artists may scorn the loss of artistic autonomy and ‘exploitation’ of the work of art in the service of scholarship, while academic scholars may be wary of the lack of conceptual and methodological clarity inherent in these artistic forms of embodied, synaesthetic meaning. The visual essay is indeed a bastard genre, the unlawful love (or perhaps more honestly: love/hate) child of academia and the arts. But precisely this hybrid, impure nature of the visual essay allows it to explore unknown ‘conditions and potentials of human life’, precisely because it combines imagination and knowledge. And while this combination may sound like an oxymoron within a scientific, positivistic paradigm, it may in fact indicate the revival, in a new context, of a very ancient alliance. Or as Giorgio Agamben formulates it in Infancy and history: on the destruction of experience (2007 [1978]): ‘Nothing can convey the extent of the change that has taken place in the meaning of experience so much as the resulting reversal of the status of the imagination. For Antiquity, the imagination, which is now expunged from knowledge as ‘unreal’, was the supreme medium of knowledge. As the intermediary between the senses and the intellect, enabling, in phantasy, the union between the sensible form and the potential intellect, it occupies in ancient and medieval culture exactly the same role that our culture assigns to experience. Far from being something unreal, the mundus imaginabilis has its full reality between the mundus sensibilis and the mundus intellegibilis , and is, indeed, the condition of their communication—that is to say, of knowledge’ (Agamben, 2007 , p. 27, italics in original).

And it is precisely this exploration of the mundus imaginabilis that should inspire us to understand artistic research as a valuable form of scholarship in the humanities.

We consider images as a broad category consisting of artefacts of the imagination, the creation of expressive ‘forms’. Images are thus not limited to visual images. For instance, the imagery used in a poem or novel, metaphors in philosophical treatises (‘image-thoughts’), actual sculptures or the imaginary space created by a performance or installation can also be considered as images, just like soundscapes, scenography, architecture.

Agamben G (2007) Infancy and history: on the destruction of experience [trans. L. Heron]. Verso, London/New York, NY

Google Scholar

Garlick A, Roes R (2014) Exercises of the man (v): found dialogues whispered to drying paint. [installation]

Gombrich EH (1986) Aby Warburg: an intellectual biography. Phaidon, Oxford, [1970]

Ingold T (2011) Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge, London/New York, NY

Ingold T (2013) Making: anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. Routledge, London/New York, NY

Johnson M (2007) The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hasselt University, Martelarenlaan 42, 3500, Hasselt, Belgium

Remco Roes & Kris Pint

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Remco Roes .

Additional information

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher’s note : Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article