Organizational development (OD) interventions: examples & best practices

In the world of organizational development, change is a constant process of discovery, analysis and action. An effective OD intervention can be one of the best mechanisms for creating impactful change and helping improve organizational efficiency.

The right OD intervention can help ensure you're solving the right problems, achieve your desired change velocity and also navigate any resistance. In this guide, we'll explore the different types of organization development interventions available to org dev teams and give you practical advice for implementing them along the way.

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

At the heart of any organizational development strategy is the desire for meaningful change and growth. But whether you’re working in a small startup or a large enterprise, implementing change can pose a challenge and isn’t without its risk.

The process of improving organizational effectiveness can lead to tough decisions and its not uncommon to see resistance to change, difficulties with employee engagement or face friction when implement large-scale change across an entire organization.

While change can be kickstarted in many forms, one of the most effective and common tools used by top HR and change management teams is an OD intervention.

Interventions aim to formalize key actions within a change process and provide a framework for successful change. In this guide, we’ll explore the four types of OD intervention and explain how and when you might deploy them in your organization.

We’ll also share some organizational development intervention examples and give practical advice and tips for implementing these interventions. So whether you’re new to organizational development or you already have an intervention in mind, there’s something for you in this guide.

What are Organizational Development (OD) interventions?

Organizational Development (OD) interventions refer to a systematic and planned series of actions or activities designed to improve the overall effectiveness, health, and performance of an organization.

To simplify, an OD intervention is a process that is actioned in response to a need for change. You might radically redesign your organizational structure because of inefficiencies in how your org works together and achieves your goals.

If you identify a significant ongoing issue in how your organization operates, innovates or grows, this is often a trigger point for an OD intervention.

For example, if you struggle to find and retain the right talent, your HR and hiring teams might use an OD intervention to identify issues with job description or design, DEI initiatives or onboarding and employee happiness.

OD interventions are typically large in scale and are designed to have a major impact on key areas of how your organization operates. They require the coordination and efforts of multiple departments and the input of senior leadership in order to take effect.

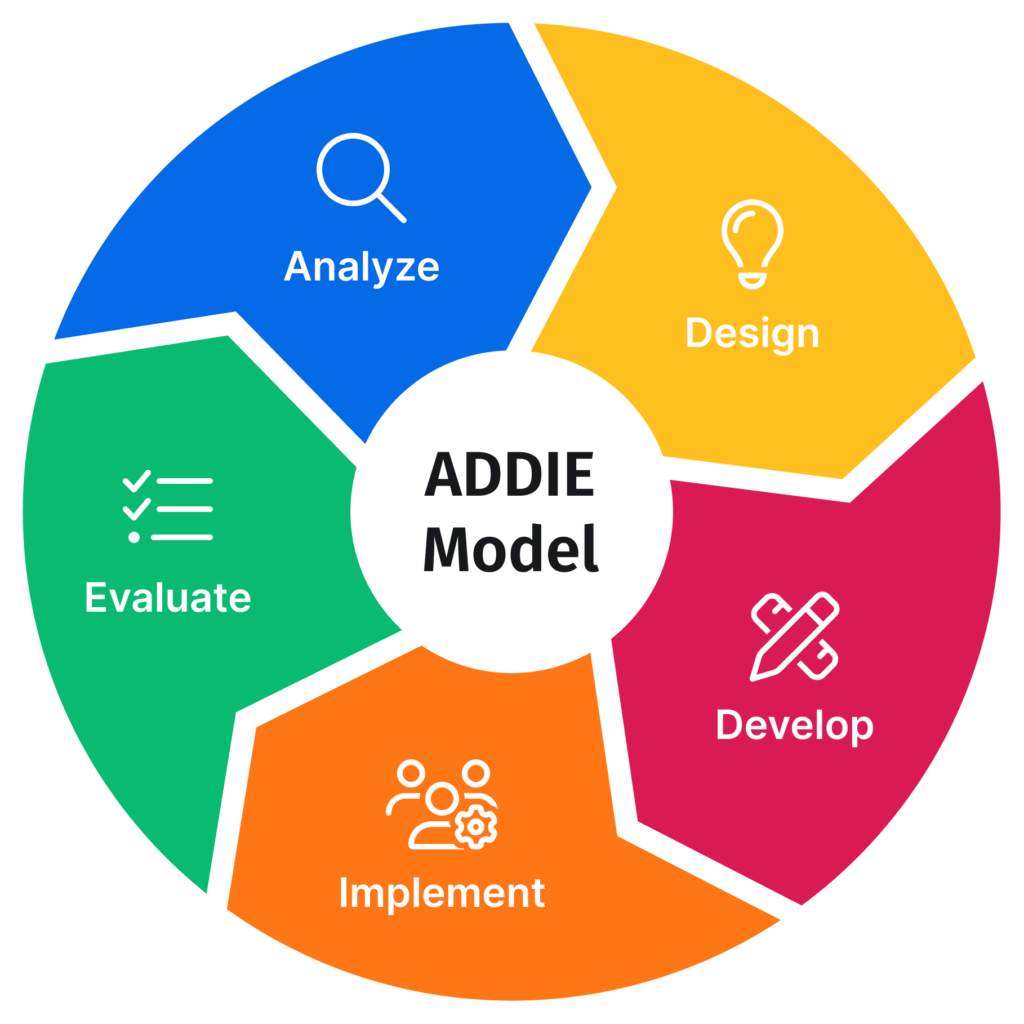

OD interventions follow a process of identifying and exploring the problem, diagnosing the issue further and then carefully developing a strategy that considers people, processes and other organizational factors.

After crafting a solution in the form of a proposed intervention, then comes the challenge of actually enacting that change and then evaluating the impact of the solution.

In the above example, your org dev team would work with affected teams to understand the situation and build an action plan that may radically change the organization.

Perhaps you discover job design is an issue or that there is a communication gap between your SMT and the rest of the company that has left your employees feeling unheard and unvalued. Finding a solution that adequately addresses organizational challenges requires a thorough exploration and analysis of the problem at hand and the people affected.

While conducting an OD intervention can be a little overwhelming, with the right process you can improve organizational performance, take care of your people and create lasting change.

What are the 4 types of organizational development (OD) interventions?

Organizational development interventions can take various forms, and they are typically categorized into different types based on their focus and objectives. Some common types of organizational development interventions include:

Human process interventions:

Human process interventions focus on improving group dynamics within the organization and how teams work together. Group interventions are common here, and change managers working in this area will likely run workshops and facilitate team building interventions with a desire to improve dynamics and interpersonal relationships on the team.

Techno-structural interventions:

OD interventions in this bracket typically focus on improving team productivity and performance by leveraging new technology and by considering how an organization is structured. Typical actions can include deploying new tools to streamline team workflows, automating processes or shifting organizational structures in order to maximise efficiency and reduce overhead.

Human resource management interventions:

Human resource management interventions typically focus on developing talent, creating employee training plans and otherwise working on how your organizations sources, nurtures and develops your people. Diversity interventions and wellness interventions also fall under this banner and as such, they’re typically implemented and coordinated by HR teams.

Strategic change interventions:

Organization development interventions related to strategy can be the among far reaching and impactful when it comes to improving an organization’s performance. This kind of change often aims to be transformational in nature and is often actioned when the long-term survival of the organization is at risk or there is a desire to radically alter how a company operates.

While other OD interventions exist, as Cummings and Worley noted in their book, Organization Development and Change 9th Edition , most interventions fall under the four types of OD interventions outlined in this guide.

That said, this list is not exhaustive nor are these OD interventions mutually exclusive. The actions your organization will take to create meaningful change will likely feature elements of various intervention types.

When considering what changes and interventions might be most effective, try not to be pigeon-holed into just one type of OD intervention or restrict yourself to set organizational strategies.

Think about the desired end state of your OD initiative and conduct a thorough root-cause analysis to select the most appropriate intervention(s). After implementation, evaluate the efficacy of your actions and be open to using other types of intervention in your ongoing quest to improve organizational efficiency.

Human Process Interventions

The original, best known and most regularly deployed OD intervention are those which focus on human processes. These kinds of interventions aim to improve interpersonal, group and organizational dynamics.

Facing challenges with team culture, communication or conflict resolution between teams and individuals? OD teams will often run interventions in the form of soft skills training , team building programs and improving relationships between different departments.

These can be low effort, such as running a weekly games session for employees to deepen bonds and get to know each other better. They can also include long term programs for conflict resolution and soft skills training, culture committees or mentoring and coaching opportunities for your team.

I recall an early career moment where there was friction between sales and support. Both teams felt misunderstood by the other and were regularly coming into conflict. Not only did this affect team morale, but it also contributed to a decline in our CSAT score AND missed sales targets.

By helping the team understand one another more deeply and creating a clear, collaborative process of handling high ticket customers and sharing information, the issue gradually improved.

Examples of human process interventions

Individual interventions.

Interventions on the individual level can have a massive impact on not only a single person’s happiness or job satisfaction but on how the system operates as a whole. Individual interventions often take the form of one-to-one interactions designed to improve how a single employee relates to their work, their team and themselves. Common interventions at this level can include one-to-one mentoring, individual growth plans, buddy systems and work shadowing programs.

Managers or HR teams might work with specific individuals to help resolve conflicts, build skills or better integrate them into the team. Regular one-to-ones can inform this process, but an individual intervention is often called for when a problem is discovered.

A common trigger point for such an intervention is during an employee feedback process. For example, if a manager has received a lot of feedback from their team that suggests they aren’t managing well, they may get coaching from a senior leader to help them improve their leadership skills.

Team forming interventions

Group dynamics are an important aspect of how a team functions. Team forming interventions are focused on helping improve those dynamics, creating alignment and helping groups get to know each other more deeply in a safe environment. Interventions designed to help accelerate team cohesion and bring groups together are some of the most common you’ll run, and it’s likely you’re doing some of them already.

Common trigger points for such an intervention can include when a new team is formed, discovering problems with how a team works together or wanting to reassert team values and shared bonds. Team building events, participatory workshops and any shared activities that create opportunities for connection and trust are all common interventions in this area.

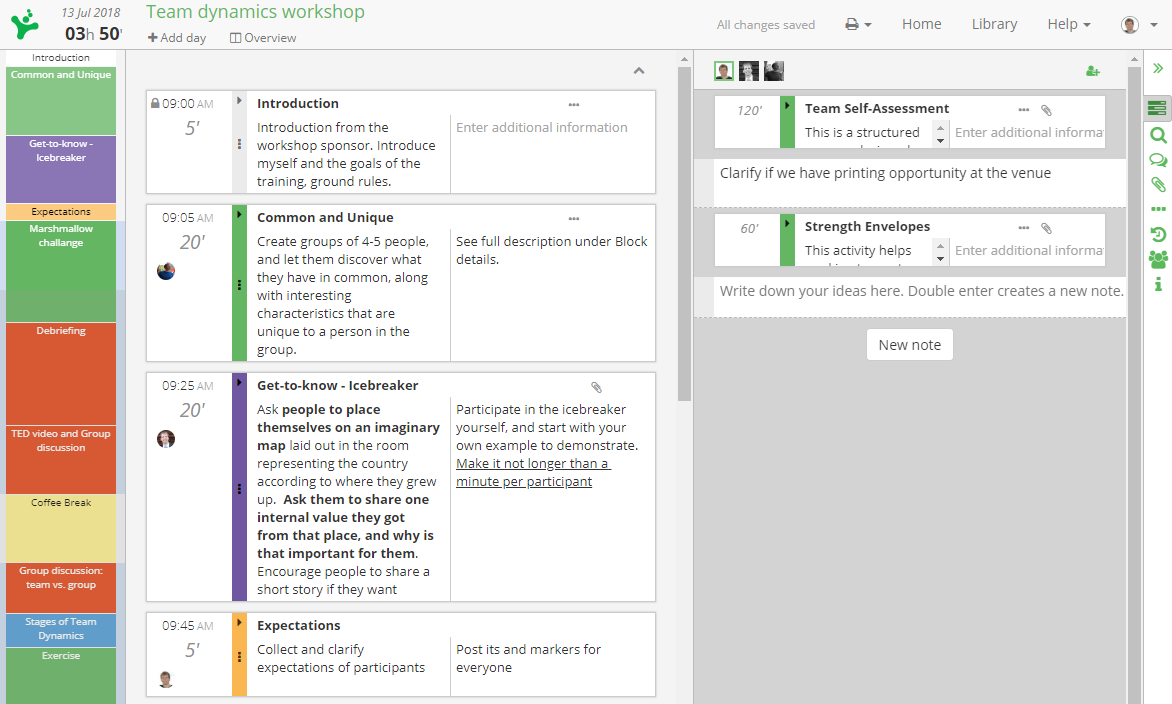

Workshops are among the most powerful formats for team forming interventions . When first bringing a team together, you might run a team canvas workshop to help a group align on their values, explore team dynamics and decide how they want to work together.

Alternatively, you might conduct a skills workshop where your team gets to ideate and learn something new as a group. In any case, be sure to support your process with the right workshop tools in order to create engagement and get results.

Purposeful team building activities are another key human process intervention. Simply spending time playing games, having fun or sharing our stories can have a powerful effect on team dynamics. The important thing is providing an opportunity for people to get to know each other more deeply, create bonds and grow together.

Intergroup interventions

When two different departments in your organization are finding it difficult to work together, an intergroup intervention is a great step. Mapping how the two teams would like to collaborate and deepening understanding of the challenges and specifics of each group’s work can help smooth things out and improve efficiency too.

In the sales/support example above, a combination of team building and process design was key to the intergroup intervention we undertook. Only by coming together and talking about the problems while also getting to know each other as individuals were we able to move forward.

For companies with few opportunities for inter-departmental work, simply bringing employees together for a team building activity so they can understand one another better is a powerful step towards change.

Tips for human process interventions

One size doesn’t fit all.

Whenever you’re working with people, it’s important to note that everyone is different and what works with one team or individual may not work for another . I recall an occasion where a company-wide team building activity (casino and club night) chosen by upper management was chosen without asking the team how they felt.

While some folks loved it, many people felt uncomfortable or were disengaged. The desired goal of improved team connections wasn’t met and instead, the group ended up feeling more fractured. Especially in the case of intergroup relations interventions, remember to include people from both groups and think about their varying needs!

Choose your intervention with the individual or group affected in mind and where possible, directly include them in the process. For example, an individual development plan should absolutely factor in how the person in question learns best and the unique context of the situation. Processes and systems are good, but don’t forget that the best outcomes arise out of solutions that have those people affected at heart.

It’s an ongoing process

One common mistake I’ve seen with organizations deploying change is to assume a single intervention will solve a problem forever. Human processes are all about relationships between people and teams. Like any relationship, these need nurturing over time.

While a single team building event can recharge the tanks and help cement bonds, without care and consistent attention, that hard work can be for nothing.

For example, let’s say you run a company values workshop to help create alignment on the future of the organization and improve company culture. Your team comes together to choose core values and everyone feels good at the end of the session. Then, 6 months later, you ask your team what your values are and nobody can remember what they are. Without follow-up actions and a process of keeping those values alive and present, the desired change in culture has been ineffective.

While most organizational development interventions are ongoing in nature, human processes can prove to be especially liquid and require extra attention from people throughout the system.

People are complex! Be sure to create systems to check-in on progress, continue the good work of an intervention afterwards and reinforce the change you wish to create.

Repetition is a key element of these processes so think not about running a single company event, but how to ensure you continuously build on your company culture.

Empower your managers

While large-scale interventions benefit from research, analysis and oversight provided by a change manager, some changes can benefit from speed.

At the human process level, line managers are often the first to see issues and spot opportunities for change. So why not give them the tools and permission to try and create positive changes for their teams?

For example, let’s say that a team member comes to you feeling overwhelmed and stressed because they’re having difficulty finding childcare. In the long-term, a company policy around childcare would be great, but that doesn’t solve the immediate issue for the team members affected.

At a human process level, proactivity and timeliness can make all the difference. Ensure your company policies and organizational culture support managers in making timely, responsible and effective interventions on behalf of their team.

As with any change process, be sure to log and track changes and reflect on the impact. In addition to alleviating difficulties for individuals and teams, smaller, fast-moving intervention techniques can provide important insights for company-wide initiatives.

Feedback loops are vital

Human systems are dynamic and ever-changing. Without feedback loops, it’s possible for issues or opportunities within those systems to go unnoticed. For some interventions such as coaching or mentoring programs, feedback is an implicit part of the process.

For others, change managers will need to create a process for gathering feedback in order to monitor, evaluate and improve OD interventions with the input of all stakeholders. Whatever system you use, it’s also vital that feedback goes both ways. Running a train the trainer course and giving your trainees feedback on their progress is important, but you should also get feedback about the program from trainees, managers and any other stakeholders.

When it comes to human systems, you’ll also find it most effective to have a system for gathering feedback well in advance of any intervention. Try to make giving and receiving feedback a consistent process for your teams and use tools to support the process where possible.

Techno-Structural Interventions:

Techno-structural interventions aim to better align an organization’s structure, technology and processes with its goals and objectives. OD interventions in this area can be among the most far reaching for any org dev team and they’re often deployed when change feels paramount for a company’s survival or for maintaining a competitive edge.

Low growth, a rapidly changing market or key areas of a business underperforming? These can be triggers for a techno-structural intervention.

Tasks such as organizational restructuring, process redesign, job enrichment or even downsizing fall under this umbrella. Other common interventions for OD teams include implementing new tools and technologies to improve efficiency, streamline workflows and future proof the company.

In techno-structural interventions, there is often an emphasis on continuous process improvement. Switching to Agile or lean methodologies or embracing total quality management processes like Six Sigma, as made famous by their use at Ford Motor Company , are common tasks.

As large-scale processes that can include changing business direction or radically repositioning your product, these interventions can be a challenge to implement.

Without a change management plan, change can be slow, meet resistance or simply not catch on. Be sure to leverage the skills and expertise of change managers and senior leadership when conducting these kinds of interventions.

Examples of techno-structural interventions

Organizational restructuring.

Restructuring an organization means rethinking how some or all of your workforce is structured and operates . Who reports to who? Which departments fall under which manager and who is responsible for making decisions that affect different areas of the business?

Common triggers for an organizational restructure include a need for greater revenue or reduced costs, a desire to refocus or change company goals or a move into a new market.

Creating innovative new products or services or simply working to resolve issues with workload, resource management or siloing are also common interventions that require a technological or structural approach.

For example, in a small startup, it’s not uncommon for all of your developers and designers to sit under the same branch in your org chart with a single founding developer as their manager.

For a while, this works and then as you grow, you start seeing bottlenecks in your dev process, and there are too many direct reports for your founding developer to handle while also trying to innovate and place your product in the market.

At this stage, an organizational restructure will be necessary in order to ensure efficiency, avoid burnout and also ensure you have the right skillset present among your dev team.

Rapid growth or reduction in your team size is another trigger for a restructure. Sometimes, this might mean a single department may split or combine with others.

On other occasions, it’s necessary for organizations to completely rethink how the hierarchy of their teams works – for example, switching from a functional org structure, where each department reports to a department head, to a matrix structure, where cross functional teams are put together on a project by project basis.

Business process reengineering

BPR is a process of radically redesigning how your organization works. It’s a comprehensive model of analyzing, redesigning and optimizing your organizational processes in order to improve business performance.

This is particularly valuable for organizations who need to see significant change in order to remain competitive or where redundancies and inefficiencies in processes are creating massive costs or an inability to meet goals.

Organizations implementing a BPR intervention typically begin by mapping all current business processes and analyzing them for opportunities, gaps and issues. After validating ideas for improvement, the organization will design an ideal future state and begin moving towards it.

By definition, BPR is wide ranging in nature, and team’s working with this kind of intervention should not feel constrained with their suggestions. Removing redundant processes or implementing a new helpdesk to improve the efficiency of your customer support team might be enough to save costs, but what if you fixed the root cause of your largest customer issues or invested in self-serve support?

If your team is finding themselves coming up against the same problems even after a solution or quick-fix has been implemented, you may need to go further. That’s the perfect time for a more thorough and radical appraisal and solution process such as BPR.

Work design interventions

Work design interventions are used when an organization wishes to improve the content or organization of the work and responsibilities falling upon individual employees or departments.

The way our work is designed affects how we feel about our job our ourselves. The tasks, working hours or contact points associated with our role can have a massive impact on our overall motivation, engagement and stress.

We all want our teams to be happy and productive, and a work design intervention can cover everything from redesigning job roles and individual tasks, to finding ways to automate or improve processes that impact job satisfaction or productivity.

For example, let’s say that individuals on a team feel stressed because they have a large workload and don’t feel supported in achieving their goals. OD interventions might include redesigning job sepcs, allocating more resources, creating reward and recognition schemes or even improving autonomy and self management.

Deep understanding of the problem is key when considering work design interventions. Be sure to conduct interviews, run a focus group and implement a continuous feedback system so you can see problems emerge and understand whether team’s need more support, job control, enrichment, development opportunties or something else entirely.

Tips for running a techno-structural intervention

Document your current processes. .

While the ideal state is that your processes are well documented in advance of problems arising, it’s not uncommon for there to be gaps in your documentation when you get around to thinking about interventions. In fact, it’s entirely possible that one of the first steps of the problem analysis and diagnosis stage will be to document any missing processes.

Before you start implementing a new process, be sure to take time to understand how your organization operates now. Try to map your processes from end-to-end and be sure to capture all the actors involved in the system. Redesigning a sales process without thinking about how it might impact your support team is a surefire way of causing new problems.

When documenting, be sure to involve stakeholders from across the organization so you can gain an accurate, in-depth picture of your processes. Not going deep enough or speaking to the people who actually enact or work with a process is another pitfall you can avoid by simply speaking to the right people.

Moving forward, aim for each team to document your processes as a matter of habit and ongoing improvement. Not only will it help any changes be smoother should you need to make them but it can help surface issues and opportunities more quickly.

Use a proven framework and do your research

Changing the structure or processes or a large organization is a difficult undertaking but you are not the first person to encounter this challenge. Lean on proven frameworks and the work of other thinkers, experts and organizations.

At SessionLab, we transitioned to an EOS framework to help us nail down our strategy, create a new org chart and organize our work . We found that the structure, advice and existing knowledge around EOS allowed us to make better decisions, transition faster and focus on implementation, rather than trying to come up with an entirely new solution.

No two organizations are the same but there’s something to learn from how others have changed for the better. Try looking at how successful organizations at a similar maturity or size to your own operate or better yet, look at those that have solved some of the challenges you’re facing. Join a masterclass or community – the ongoing support and insight of peers can also be invaluable in actioning change.

Run workshops to surface insights quickly and collaboratively

When thinking about introducing new processes it’s imperative that you first explore and diagnose a problem correctly . When it comes to how teams and departments operate, it’s not uncommon for hidden variables or unspoken actions within the system to be at the heart of your issues. So how do you bring them out into the open and encourage openness from your team?

Speaking to major stakeholders and business people across the org is vital, but it’s often not enough to just send out an email asking for input.

Workshops are some of the most powerful intervention techniques available to change managers and org dev teams. Ideating on possible solutions collaboratively is often a more effective way to truly discover the root cause of issues and create solutions that account for the people who will be most affected by the process you are changing.

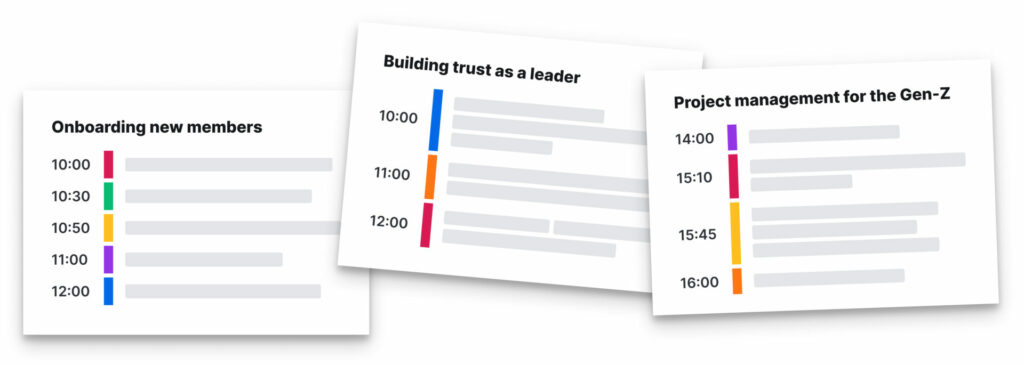

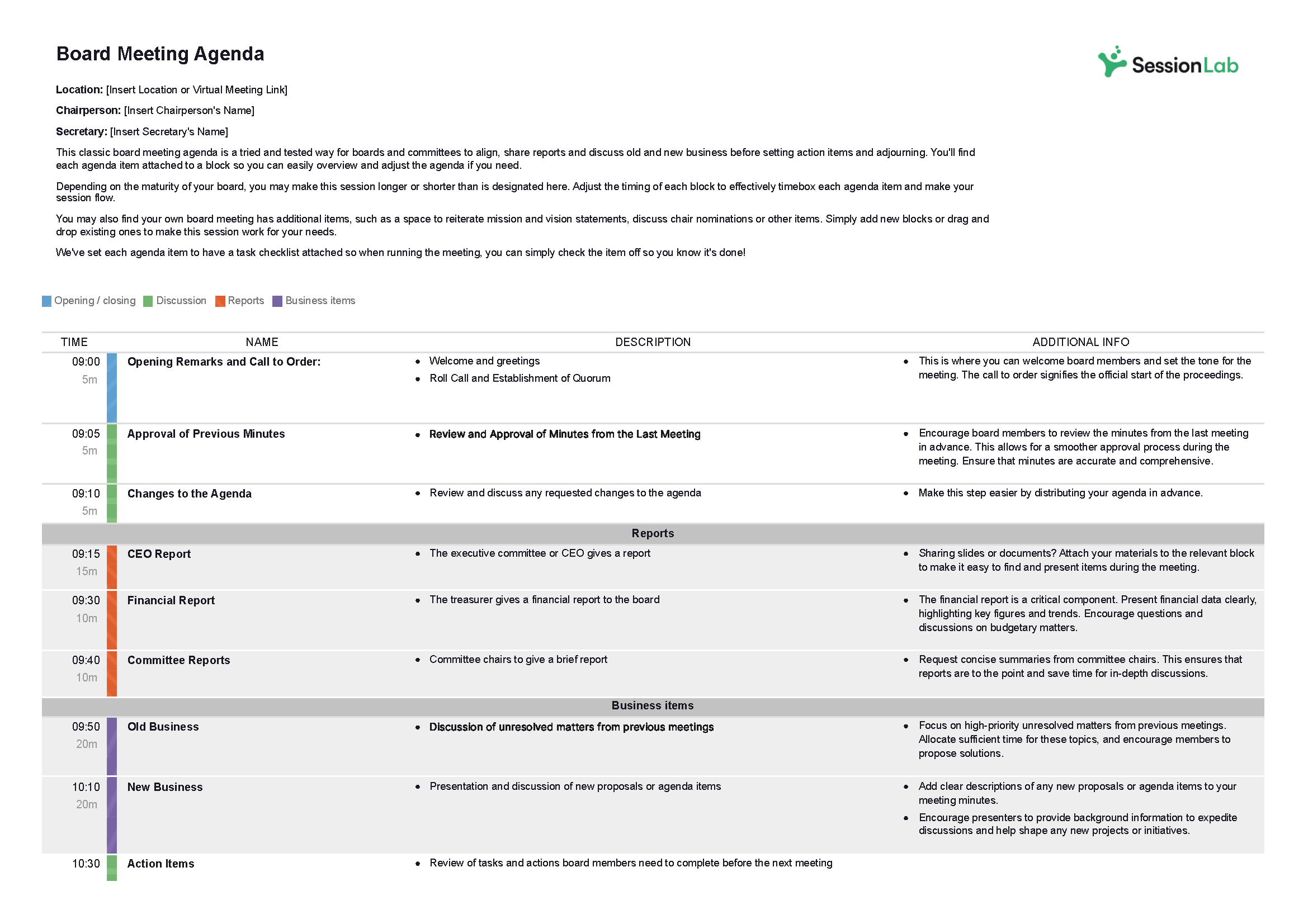

SessionLab is an effective tool for designing and delivering the workshops that you’ll use to support your OD intervention process. Invite stakeholders to co-create your agenda in real-time and involve them in the change process. Save time designing your key workshops and ensure your process is efficient with SessionLab.

Human Resource Management (HRM) Interventions

HRM interventions concentrate on developing and managing human resources within the organization. Examples include improving hiring processes, creating and reinforcing diversity, improving performance management processes and building opportunities for career development. People are one of the most important parts of how an organization functions and HRM interventions are designed to directly impact the people working in your company.

As the name would suggest, these kinds of interventions are often deployed by or in conjunction with HR teams in response to difficulties with hiring or retaining staff, employee satisfaction or problems with performance.

Effective change tracking, strong feedback loops and good communication are essential elements of a successful HRM intervention. Programs and initiatives that form the backbone of human resource development – such as wellness or training programs – are ongoing in nature.

You’ll often find that such an intervention takes time to achieve its chosen goal and the strength of your research is a key element of success. Purposeful interventions that incorporate the direct input of your employees are more likely to be fit for purpose and create long-lasting change.

Examples of human resource management interventions

Employee wellness interventions.

Staff are reporting high levels of burnout and managers are noting that their direct reports are feeling overwhelmed or stressed. This is the perfect time for an employee wellness intervention.

While HR teams might also consider job design and other factors, these programs most commonly involve the creation of new opportunities and programs designed to alleviate issues and improve the health of your team.

Some common strategies include creating new employee benefits linked to health and wellness . Cycle-to-work schemes, free gym memberships and budgets to support employees in improving their own wellbeing can all have positive impacts on team wellness.

You might also provide opportunities for staff to access company healthcare and counselling. On the lighter side, creating a budget for healthy lunches and office snacks, giving opportunities to volunteer or exercise on company time can also have an immediate impact.

While the same is true for most interventions, employee wellness programs absolutely require the involvement of everyone on your team when choosing what to implement. A poorly designed or unfit for purpose intervention can quite easily have a negative impact on wellness.

Let’s say you create a scheme where everyone in the office gets a free healthy lunch. Great for your onsite team, but how about your hybrid and remote employees? If you don’t offer a similar benefit or take them into account, they could feel less valued and overall wellness could suffer.

Performance management interventions

Managing and hopefully improving the performance of your team over time is a necessity for any successful business. But what about if the problem you uncover issues with staff performance or a lack of process for tracking and improving the performance of your team? Time for a performance management intervention.

For some organizations, such an intervention might include actually setting up a performance management system and ensuring that every member of staff is given frequent feedback and opportunities to improve. For others, this might mean enabling managers with better tools and processes or creating reward programmes to encourage higher performance.

Coaching, mentoring and the unblocking of other issues that might impact employee performance are also key tasks that can be part of a performance management intervention.

A key part of a successful performance management intervention is truly understanding the root cause of an issue. Underperforming staff may face issues with job design, internal or external pressures or may not have even been given feedback or an opportunity to improve before.

Try not to jump into the deep-end with punitive measures unless you’ve already taken a more holistic approach that gives staff the feedback, tools and opportunities they need to develop.

Talent development interventions

As a company grows and roles change, it’s not uncommon to discover that your team has skill gaps that need to be filled. You might find that a changing market means that key competencies need to be updated or supported with new training. Or you might discover that people are unhappy with the pace of their career development and are leaving the company as a result.

Talent development interventions are all about managing and developing your team so they’re better positioned to do their jobs, grow in their careers and stick around.

Common talent development interventions include designing new training programs and coaching opportunities, personal growth plans and even reconsidering how you onboarding, compensate and promote members of your team. These kinds of interventions also extend to rethinking how your HR team goes about attracting and hiring new team members.

Any time you are struggling with team performance, remember that the solution is only as good as the analysis of the problem. Talk to team members at different levels and who have been with the company for different lengths of time.

Only once you’ve truly identified the root cause of the issue can you implement an intervention that will serve everyone on your team and prevent issues from occurring in the future.

Tips for running HRM interventions

Engage people throughout the organization .

Any intervention that directly affects your team should get some level of input from the people being affected. For some interventions, it’s absolutely paramount to source input and get feedback from your employees.

For example, a wellness program for your remote employees without the input of remote team members isn’t likely to serve their needs.

Underperforming sales team? Rather than making an assumption at a management level, talk to your sales reps and see what they think the issue is. Not only are these people more likely to be able to identify the root cause of a problem, but they’re also instrumental in actioning any given intervention.

Engaging people early in the process is helpful for getting buy-in and removing barriers to change. Don’t keep your change discussions entirely confined to management meetings and get input when you can, so long as it’s appropriate.

Support your process with data

Human-process interventions can sometimes be kickstarted by qualitative data : anecdotes about how people on the team are feeling or gut feelings from management about burnout or stress. While these kinds of comments and discussions are vital, it’s also important to back-up any change with data and processes to determine the viability and success of any initiative.

The gut feeling about a problem is likely onto something, but without data of some kind, it can be hard to be confident that your solution is the right one to support your wider business strategy.

For example, before making a large-sweeping change to working hours, maybe survey your team to find out if that works for them. Want to roll out your marketing training program to other teams? What data about team performance and employee satisfaction do you have that supports that decision?

Feeling like your hiring process is bringing in a large number of low quality interviewees and want to make a change? Check out industry standards, compare across job roles and back up your feelings with hard data wherever possible.

Start measuring employee KPIS before the need for an intervention

While some challenges are difficult to predict, HR teams are in a great position to pro-actively source input, monitor employee happiness and prepare for wider change.

If you’re already using a performance management system, it’s easy to start tracking how your team feels, see the efficacy of personal development plans and monitor things like onboarding efficacy and retention.

If you’re not, it really pays to start measuring employee sentiment and refining your feedback loops so that you have something to point to if the need for a HRM intervention arises.

Even something as simple as a monthly employee satisfaction survey can help your HR team see issues coming, track changes over time and also create an ongoing channel for surfacing opportunities for improvement.

Properly resource line managers

Managers across your organization are vital parts of making any HRM intervention a success. Whether they’re directly involved as a result of overhauling performance management processes or indirectly affected because of changes to flexible working hours or giving back schemes, your managers often have extra work or overhead created by HRM interventions.

Don’t underestimate the impact and ripple effects of even the smallest interventions. Line managers are often the frontline in actioning change or hearing misgivings from employees. They can often be those people who pick up slack within the system.

Be sure to take this additional workload into account and create extra resources and support processes for line managers . Consult them before any changes are rolled out, involve them in the process as much as needed and think about how to make it easier for them to implement and support processes when engaging with their teams.

Strategic Change Interventions

While other organizational development interventions can operate on the individual to small group level, strategic change interventions are more far-reaching in scope. These interventions are designed to analyze and radically redefine how an organization functions or what it hopes to achieve.

An organization might reconsider its vision or goals because of changes in the market or because the team has conflicting ideas about their shared missions or core values. Other times, the changes can come about because of issues preventing a company from meeting their goals, such as how a team is structured or how a culture of innovation is nurtured.

Interventions that impact core business strategies are usually undertaken when the survival or competitive edge of a business is at risk. Strategic change can be prompted by internal or external factors, but they’re very rarely taken lightly. The desire is for a massive improvement in how the company functions and the work required is often massive in scale too.

Done right, however, and companies who deploy these interventions can create incredible innovation, reverse falling revenue forecasts and radically improve employee happiness too.

Examples of strategic change interventions

Transformational change interventions.

Examples of interventions for transformational change include a top-to-bottom organizational redesign, perhaps in response to a changing environment, a major pivot or a desire to enact meaningful culture change.

Dangers to the long term viability of the business, major competition or market shifts can be a common trigger for a transformational change intervention. You can also find that analyzing challenges to employee retention can uncover an issue with company culture that only a massive change and restructure can improve.

Expect transformational changes to radically alter how a company operates, shifting the status quo and transforming the organization into something that is better positioned to achieve its goals.

Continuous change interventions

Continuous change interventions are designed to help an organization make minor improvements on an ongoing basis. Creating a culture of learning, developing an experimental, continuous growth model or creating space for innovation and cooperative structures are common actions taken here.

Trans-organzational change interventions

Trans-organizational change refers to interventions where two or more organizations are involved. Mergers and acquisitions fall under this umbrella though major business partnerships are also an example of a task that might require an OD intervention.

Tips for implementing strategic change interventions

Map your systems and organizational structure.

Before you decide where to take your organization, you’ll need a clear view of where you are right now. Activities such as Systems Mapping are a great first start for any intervention but they are especially valuable when considering large-scale strategic change.

Not only can you more accurately assess the scope of what you’re doing, but you can also draw out where changes need to take place.

Try creating a map of your organization with a process of systems mapping to better understand and enact your proposed change. These are workshops dedicated to drawing out (and actually drawing) all the stakeholders and other elements (such as suppliers, for example) that compose the wider system of which your company is a part.

Systems Mapping will help your teams look at the big picture and figure out best place to intervene.

Get outside help

Enacting or even deciding whether to undergo a major strategic change is a significant undertaking. Experience and expertise is invaluable in making a change process a success and when conducting major organizational change, a consultant or agency can make all the difference.

Receiving advice from someone who has enabled change for dozens of companies and has seen many processes from inception to completion is invaluable. They’ll help you ask the right questions, show you a proven framework for change and also help you navigate any roadblocks. Consultants are also adept at working around unintentional biases or assumptions that can form as a long-term employee.

If you want to improve your change velocity, feel confident in the changes you’re making and streamline the change management process, professional assistance is absolutely worth investigating.

Remember that big changes take time (and sometimes multiple interventions)

Strategic changes can involve upending how your company operates, thinks about its culture or how it positions itself in the market. While a single intervention might help you successfully restructure your team, it will take further work and careful management to help those teams thrive in the new environment.

Committing to large-scale organizational change means committing to a process that will take time, consistent effort and potentially further interventions along the way. Prepare your teams and managers for a long, ongoing process and be sure to check in along the way.

Shifting your target customer base for example, might require your sales and marketing teams to radically rethink how they source and talk to customers. While the eventual change might be great, don’t expect to see a complete upswing overnight. Be sure to take this into account when setting targets and when managing your people.

Set expectations accordingly and ensure there are feedback and support systems in place for your team while such large scale changes are in action. Run effective team meetings to keep track of what’s happening and ensure stakeholders can synchronise effectively.

More tips for a successful OD intervention

Organizational development is a complex process that can test even the most seasoned teams . The good news is that you’re not the first company undergoing a process of change and there are a heap of best practices and tips you can use to help you achieve your desired change.

We’ve included tips for each of the different types of OD intervention above, though we also wanted to share some additional OD best practices that should help, regardless of the kind of intervention you’re running.

Carefully assess the current state of the business

Designing and deploying the right OD intervention means gaining a thorough understanding of where your business is currently at. Not only will you need to determine what needs to change, but also gain an understanding of drivers and potential blockers to that change.

Failure to do this properly can result in slow or unsuccessful change. It can even lead to changes with unintended consequences or negative effects.

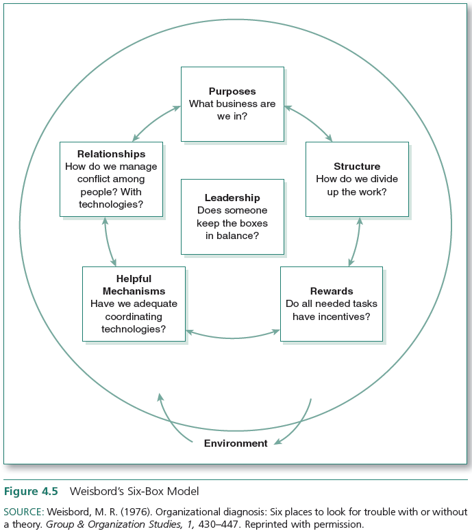

There are various tools for assessing the state of the business. A change management framework is one such tool, though you’ll likely synthesize everything from stakeholder input, current business performance, risk assessments and other situational analysis tools.

The key here is to ensure you deeply understand the system being changed in order to propose the right change and have the resources and environment to make it happen.

Find the root cause of your problem

Long lasting change comes from a deep understanding of the root cause of an issue. Facing challenges with high staff turnover and low morale? Bringing in free snacks and reducing working hours over the holidays might have a short-term impact on employee happiness, but it’s unlikely to truly solve the issue.

Whenever engaging in an organizational development process, be sure to go deep enough to truly understand the cause of an issue before enacting change. Don’t rely on assumptions and talk to your team, often multiple times while conducting a root cause analysis.

Review performance data and thoroughly analyze what you find. (Sometimes, it’s enough to just keep asking why!) If in doubt, run a problem solving workshop to truly surface what’s going on and create a safe space for uncovering issues.

Not spending enough time analyzing an issue is a potential pitffall for any organization seeking to improve. Without finding the root cause of organizational issues, it’s entirely possible to treat the symptoms rather than finding a cure. Avoid this by going deep, involving people across the organization, backing up ideas with data where possible and be ready to challenge your assumptions.

Fishbone Analysis #problem solving ##root cause analysis #decision making #online facilitation A process to help identify and understand the origins of problems, issues or observations.

Have a clear purpose and end-state

People are more likely to get behind change when they know exactly what it is they are working towards. The purpose of an intervention should be clear, focused and simple to explain. If you can’t easily explain why you’re making a change or it’s overly complex or unclear, chances are you’re trying to do too much or you don’t have a clear understanding of the problem you are trying to solve.

Clarity of purpose helps ensure that you are taking the right actions and that your change will be successful. Decision making gets easier when you have a clear purpose too. Does this support our purpose and will it help us achieve our goal? Yes: let’s do it. No: either we don’t do it or it could be the focus of a separate intervention or change initiative.

In addition to a clear purpose, it’s useful to have a desired end-state in mind when conducting any organizational development activities. What will the business look like when you’re done? How will you know your change has been a success?

Asking these questions helps you align and focus your actions while also giving you a means to evaluate the impact of your process. An exciting, aspirational end-state is also invaluable when it comes to getting support for your intervention and reducing possible resistance to change.

Align interventions with organizational goals

Successful change requires many moving parts across your organization to be working in tandem. Your organizational goals or mission are often the north star for anything your team does, including any development processes. Often, the simplest way to determine the right OD intervention is to ask whether it helps your organization better achieve its goals. If the answer is yes, then it’s a great candidate for action. Aligning your interventions with your greater goals can also help ensure that the team is able to get behind them and understand why the intervention is being run. For example, let’s say you’re an NGO whose mission is to help provide learning opportunities for disadvantaged folks.

Interventions that are aligned with that organizational goal, either helping your team reach more people with better tools or clearly improve your team’s ability to do their core tasks are much more likely to succeed than interventions that seem tangential or don’t support that core mission.

Work backwards from your ideal future state

A common facilitation technique for creating change is backcasting, or imagining an ideal future state and working backwards to decide how to achieve it. Often, the prospect of organizatioanl change can leave teams overwhelmed with how to achieve it or be unsure of how their actions might result in a desired change.

Working backwards can simplify the process, reducing noise and help crystallize your shared purpose. By thinking big, you can often find that the ideal steps towards change become more clearer.

An aspirational future state can also be an effective tool when getting stakeholder buy-in. A shared vision gives everyone a clear target and it’s easier to align various actions around an organizational goal they believe in.

Backcasting #define intentions #create #design #action Backcasting is a method for planning the actions necessary to reach desired future goals. This method is often applied in a workshop format with stakeholders participating. To be used when a future goal (even if it is vague) has been identified.

Communicate effectively

Resistance to change can often come as a result of poor communication or a lack of understanding about why a change is being implemented at all. How you talk about your OD intervention is an important part of ensuring that stakeholders and those affected get behind the initiative.

When rolling out your OD intervention, create a communication plan and be sure to highlight the purpose of the proposed change. For example, rolling out a personal development program without context can cause confusion or anxiety. Is this a genuine desire to improve career prospects and employee fulfilment, or is there an issue with my performance and is my job at risk?

Clearly communicate why and how you’re making changes, create documentation that is easy to access and create space for questions and answers too. By providing a clear vision and purpose for such a program, you can make it easier for everyone involved to get involved and help your change take root.

Be wary of analysis paralysis

Thorough analysis and careful planning is an integral part of leading an organizational change. But is it possible to do too much?

For some teams lacking in confidence or expertise, it’s possible they delay making changes or continue to analyze and weigh up options even when the path is clear. It’s a tough balance, but spending too long assessing when a case for change is clear can actually undermine the process or create barriers to change.

You can mitigate this potential by following a proven framework, having clear organizational timelines and by bringing in consultants to help increase the velocity of your process. In other cases, it’s a matter of using an 80/20 principle or using a bias for action methodology to make a decision and move forward.

If your company is just starting the process of organizational development, it’s natural to want to tread carefully. Just be certain that your process is efficient and that your team’s anxieties are aired and don’t get in the way of progress.

Get started!

In the case of small interventions or change processes, you can often adopt a more lightweight process and get started more quickly. You may not need to mobilize your entire change management team for a localized intervention. You might also find that you can gain confidence in a proposed change without performing a top-to-bottom situational analysis.

Change can only happen once a process is set in action and in some cases, it’s worthy to just get started, monitor the results and empower your teams to be proactive. This is different for every organization and while it’s common for small teams to be more agile, large organizations often have more red-tape, and with good reason.

Recognise the specific circumstances of your organization and review every OD intervention you perform to see how you can do better. If your changes are successful but your team feels like you spend too long assessing when things were clear early in the process, that makes a good case for trying to streamline your process.

Not every change needs a large intervention

In my experience, the thoroughness of the process directly correlates to the scale of the proposed change. Over-engineering small-scale change processes can create unnecessary friction or lead to frustrated team members. This can cause just as many problems as under-engineering a large scale intervention and developing a poor solution. In doubt about a small, low–risk change but don’t want to block an enthusiastic team mate? Call it an experiment and monitor the impact. Sometimes, you can learn more from just getting started, rather than adding it to a massive organizational to-do-list.

In any case, it’s worthy to explore how you can create continuous change by engaging your team proactively in the process. Teams are vital actors in any change process and by empowering them, you can often avoid future issues and ensure opportunities are taken where possible.

Leaders are integral

Without leadership support, organizational change can struggle to get traction. Everyone from senior leaders to line managers are instrumental in helping change be a success. This might include modelling changes yourself by attending skills workshops, volunteering or cycling to work in line with sustainability goals.

Often, leaders and line managers are also responsible for tracking employee sentiment, keeping change processes front-of-mind and helping employees adapt to change.

Without leadership backing, change can be slow or ineffective. Get them onboard early and give them the tools they need to brief and support their teams and they can help any change process be smooth and purposeful.

Leaders aren’t just important when helping enact change. During the early stages of an org dev process, leaders are often key stakeholders in research and analysis tasks. They’re well positioned to provide input, spot additional risks and see dependencies you might not.

Engage leaders throughout the organization as early as possible and keep them in-the-loop. Change doesn’t just come from your senior management team! Even the most well-designed OD interventions can fall down if logistics or team workloads don’t align with the process.

Acknowledge the additional workload of change and plan accordingly

Change is hard for most living things, humans included. Whatever the level of involvement in planning, enacting and evaluating organizational change, the process can create additional work or mental load for those affected. Acknowledge this and be proactive in order to support your team and remove potential barriers to change too.

This might look like simply reducing workload in other areas to create space for change, creating support structures or otherwise addressing the unique pain points that might come up in the process.

Sometimes, even an acknowledgement and group discussion about change can be sufficient to clear the air and give teams the opportunity to suggest ways to counterbalance any increased workload.

Use measurable metrics for success

Measuring the effects of change is an integral part of organizational development, but how can you ensure you are measuring the right metrics and have confidence that your change has been successful?

KPIs and data-based measurements are your friend here. Seeing a clear change in revenue, customer satisfaction or staff turnover in numbers can provide verifiable proof your change has been successful. That said, think about sourcing both qualitative and quantitative data where possible.

Staff might anecdotally report lower stress in a one-on-one meeting, but how are sick days trending since you implemented the change? Revenue might be up, but did your sales team bag an enormous contract that has skewed data?

It’s also important to decide on the metrics of success before you implement any change. You’ll want to use metrics that will be directly affected by what you’re doing and align your actions accordingly.

It’s also vital that you actually have the means to measure what you want to measure and ideally source existing data to serve as a point of comparison. If you’re conducting an employee wellness program to lower stress, see if you have previous surveys or performance metrics to serve as a baseline. Using a combination of leading and lagging indicators can also be helpful. For example, a leading indicator for the efficacy of your wellness program might be how many people take advantage of new services on a weekly basis. If more people take advantage of the services, you’d expect to see lower stress – great, but it’s only one piece of the puzzle.

A lagging indicator might be how many staff are reporting high stress levels in a monthly employee survey or even the productivity levels for a team or department. With a combination of these kinds of metrics, you can not only determine if your change has been successful, but also see where in the process you might make improvements.

Use tools to support your process

Successfully implementing an OD intervention strategy means organizing tasks, project managing the process and evaluating its impact. It’s a lot of work that can be streamlined by using the right tools.

Use change management software to optimize the end-to-end process of an intervention and improve the velocity of change you’re enacting.

It’s also worth recognising that various barriers to change can be mitigated by using efficient processes and bespoke tools. When committing to creating impactful organizational change, invest in tools that will help you achieve your goals faster and more efficiently.

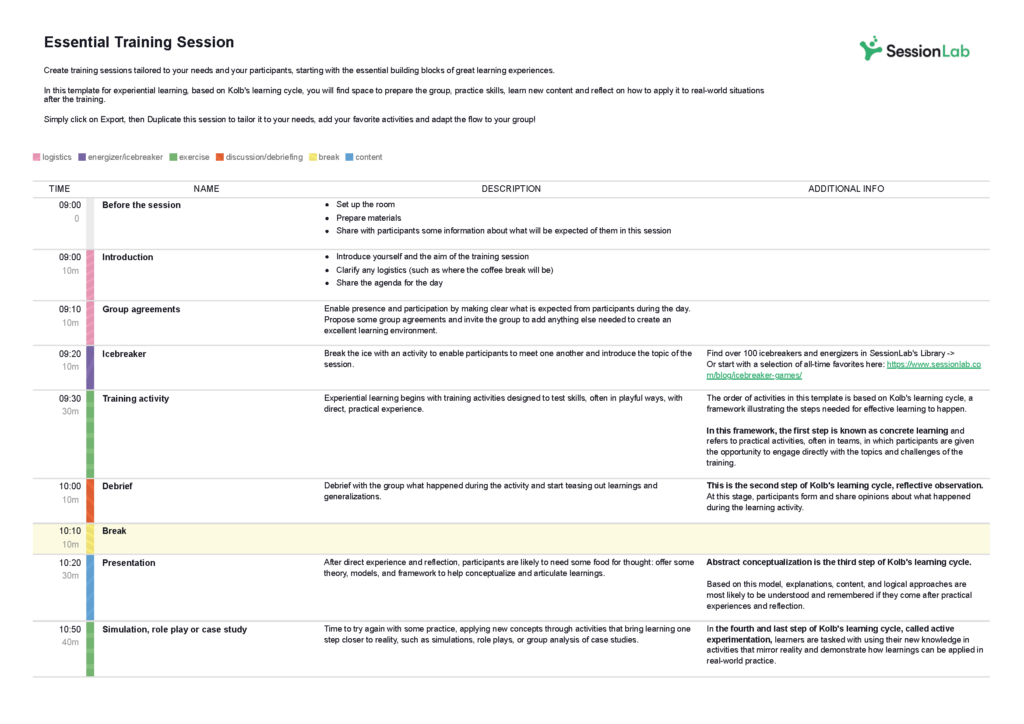

With SessionLab, you can create stakeholder workshops and braining storming sessions in minutes. Drag and drop blocks to create your session. Invite collaborators to co-create your design in one-place and make changes with ease.

Developing a new learning program ? Create your ideal learning flow and invite your course managers and subject matter experts to collaborate in one-place.

Innovation experts and consultancies have found SessionLab to be a vital part of creating change for their clients. Get started for free and save time and effort in your session design process.

Evaluate & adjust

Once an intervention is complete, it’s time to evaluate. Using your carefully chosen success metrics in combination with stakeholder input, you’ll determine if you’ve achieved your goals and if not, how might you change or adjust your intervention to do so.

While it can be tempting to see a green KPI and call it a day, proper investigation of why you were successful can help ensure you can repeat that success in future. It can also help your org dev team improve their processes and fuel the next intervention too!

And how about if you feel the need to make changes in the middle of an intervention? However well you’ve designed and run a change process, it’s possible for something unexpected to occur or for additional elements to emerge. Be sure to have a system of checking-in on progress and adjusting where necessary.

Use your KPIs, talk to your team and create open channels for feedback . In some change processes, you might freely adjust throughout the process or you may want to complete the entire intervention before properly evaluating and making changes.

For example, if you’re running a series of soft skills workshops and discover that employees are struggling to engage, the workshop facilitator might take a different approach in order to fulfil the needs of the intervention and you might adjust the program as a result.

On the other hand, if you’re rolling out a new interview process with your HR team and they’ve had some feedback that it’s too long from a few participants. It might be too early to make changes when the success of the intervention is the quality of the final hire.

Whatever your process, thorough evaluation is necessary to first determine the success of your intervention and then enable your team to make the right adjustments. Ensure you have the means to collect data and input from your team in order to evaluate well early so that you aren’t picking up the pieces later!

Conclusion

OD interventions are a key tool for any company wanting to improve organizational performance, stay competitive and create meaningful change.

Whether it’s finding ways to improve employee development, implement new tools or radically restructure your team, we hope that this guide will help you take the first steps in creating your intervention strategy.

In my experience, while the distinctions between different types of group interventions are useful for understanding the role of organizational development and what tools might be available, they are not mutually exclusive.

For example, fixing a complex problem like low employee satisfaction may include a combination of human process, human resource management and other change strategies. As with any change process, the solutions used should respond to the specifics of the challenge and situation you face.

Your own OD intervention strategy will likely feature elements of various intervention types and in truth, OD interventions are most successful when tailored to the organization at hand and the problems they are facing. Looking for more resources? Discover how change management software can help facilitate successful OD interventions and improve organizational effectiveness.

Running workshops as part of your group interventions? Explore how to create engaging and impactful sessions in this workshop planning guide.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Going from a mere idea to a workshop that delivers results for your clients can feel like a daunting task. In this piece, we will shine a light on all the work behind the scenes and help you learn how to plan a workshop from start to finish. On a good day, facilitation can feel like effortless magic, but that is mostly the result of backstage work, foresight, and a lot of careful planning. Read on to learn a step-by-step approach to breaking the process of planning a workshop into small, manageable chunks. The flow starts with the first meeting with a client to define the purposes of a workshop.…

How does learning work? A clever 9-year-old once told me: “I know I am learning something new when I am surprised.” The science of adult learning tells us that, in order to learn new skills (which, unsurprisingly, is harder for adults to do than kids) grown-ups need to first get into a specific headspace. In a business, this approach is often employed in a training session where employees learn new skills or work on professional development. But how do you ensure your training is effective? In this guide, we'll explore how to create an effective training session plan and run engaging training sessions. As team leader, project manager, or consultant,…

Effective online tools are a necessity for smooth and engaging virtual workshops and meetings. But how do you choose the right ones? Do you sometimes feel that the good old pen and paper or MS Office toolkit and email leaves you struggling to stay on top of managing and delivering your workshop? Fortunately, there are plenty of online tools to make your life easier when you need to facilitate a meeting and lead workshops. In this post, we’ll share our favorite online tools you can use to make your job as a facilitator easier. In fact, there are plenty of free online workshop tools and meeting facilitation software you can…

Design your next workshop with SessionLab

Join the 150,000 facilitators using SessionLab

Sign up for free

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Cases and Exercises in Organization Development & Change

- Donald L. Anderson - University of Denver, USA

- Description

Cases and Exercises in Organization Development & Change, Second Edition encourages students to practice organization development (OD) skills in unison with learning about theories of organizational change and human behavior. The book includes a comprehensive collection of cases about the OD process and organization-wide, team, and individual interventions, including global OD, dialogic OD, and OD in virtual organizations. In addition to real-world cases, author Donald L. Anderson gives students practical and experiential exercises that make the course material come alive through realistic scenarios that managers and organizational change practitioners regularly experience.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

Password-protected Instructor Resources include teaching notes for the cases, designed for instructors to expand questions to students or initiate class discussion.

The Text has not yet arrived.

Case studies support course work synthesis

This is a very good book to use in the classroom because it helps students connect theoretical knowledge about organizational development and change with practice.

Cases were well put together and kept the students engaged.

NEW TO THIS EDITION

- New cases discuss relevant areas of growing importance to OD practitioners, encouraging students to think about topics such as global OD, dialogic OD, and OD in virtual organizations.

- Each case contains learning objectives, discussion questions, and suggestions for further reading, encouraging students to take an active role to interpret and discover the cases’ meaning.

- The revised structure aligns with Organization Development, Fourth Edition , making it easier for students and instructors to use the two books simultaneously in a semester.

KEY FEATURES

- Provides rich scenarios of organizational life , with each case constructed as a brief scene in which students are asked to weigh the pros and cons of alternate courses of action.

- Written by experts in the field , these original cases focus precisely on a specific topic in the OD process or intervention method.

- Cases represent a wide range of industries in which OD is practiced, exposing students to issues in for-profit businesses, educational institutions, government agencies, and health care organizations.

Includes a variety of exercises including self-assessment tools, role-play exercises, and individual or group simulations to enhance students' skill development in acting as change agents.

Organizational Change and Development: A Case Study in the Indian Electricity Market

Cite this chapter.

- Pawan Budhwar ,

- Jyotsna Bhatnagar &

- Debi Saini

1 Citations

The present economic growth of India is largely an outcome of the liberalization of its economic policies in 1991. Since gaining independence in 1947, India adopted a “mixed economy” approach (emphasizing both private and public enterprise). This had the effect of reducing both entrepreneurship and global competitiveness. Despite the formalities of planning, the Indian economy reached its worst in 1990 and witnessed a double digit rate of inflation, decelerated industrial production, fiscal indiscipline, a very high ratio of borrowing to the GNP (both internal and external) and a dismally low level of foreign exchange reserves. The World Bank and the IMF agreed to bail out India at that time on the condition that it changed to a “free market economy” from what at the time was a regulated regime. To meet the challenges, the government announced a series of economic policies, followed by a new industrial policy supported by fiscal and trade policies. A number of reforms were made in the public sector that affected trade and exchange policy. At the same time, the banking sector together with activity in foreign investment was liberalized.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Further reading

Budhwar, P. and Varma, A. (2011a) (eds) Doing Business in India , London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Budhwar, P. and Varma, A. (2011b) “Emerging HR Management in India and the way forward”, Organizational Dynamics , 40(4), pp. 317–25.

Article Google Scholar

Budhwar, P. and Varma, A. (2010) “Guest Editors’ Introduction: Emerging Patterns of HRM in the New Indian Economic Environment”, Human Resource Management , 49(3), pp. 343–51.

Budhwar, P. and Bhatnagar, J. (2009) The Changing Face of People Management in India , London: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Burnes, B. (2006) Managing Change , Harlow: FT Prentice-Hall.

Clardy, A. (2004) “Toward an HRD Auditing Protocol: Assessing HRD Risk Management Practices”, HumanResourceDevelopment Review , 3(2), pp. 124–50.

Kotter, J. P. and Cohen, D. S. (2006) The Heart of Change: Real-life Stories of How People Change their Organizations , Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Ramnarayan, S. (2003) “Changing Mindsets of Middle-level Officers in Government Organizations”, Vikalpa , 28(4), pp. 63–76.

Sharma, R. R. (2007) Change Management: Concepts and Applications , New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Director of Executive Education, Aston Business School, UK

Cora Lynn Heimer Rathbone

Copyright information

© 2012 Pawan Budhwar, Jyotsna Bhatnagar and Debi Saini

About this chapter

Budhwar, P., Bhatnagar, J., Saini, D. (2012). Organizational Change and Development: A Case Study in the Indian Electricity Market. In: Rathbone, C.L.H. (eds) Ready for Change?. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137008404_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137008404_9

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-34448-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-00840-4

eBook Packages : Palgrave Business & Management Collection Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

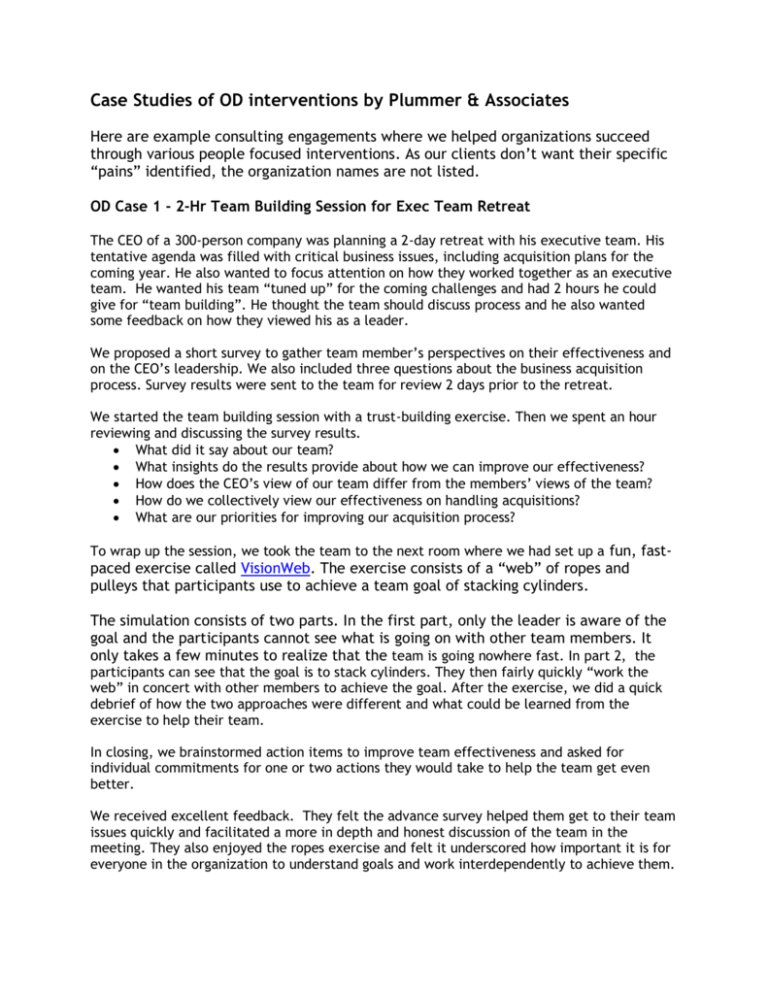

The Impact of OD Interventions on Performance Management: A Case Study

Article sidebar, main article content.

Good performance management systems can have a significant impact upon the operations and success of any organization. The broad objectives of this article are to identify the problematic areas in the company and identify ways to improve staff performance, employee motivation and involvement. The specific research objectives are to describe and analyse the current situation of the company and to conduct a 3-phase diagnosis: Phase 1, identification of problematic areas which need improvement; Phase 2 development and implementation of intervention techniques; Phase 3 monitoring and evaluation of results after the intervention to determine the impact on the company performance. Both the qualitative and quantitative methods of analysis were used which included interview, observation and questionnaires. The findings are that after the ODI, staff performance improved. This improvement has led to better performance of the organization at three levels. At the individual level—staff perceived more motivation and that their competencies at work increased. At the team level—staff perceived that there was an improvement in team effort. At the corporate level— the findings suggest that improved corporate performance is linked to improved individual and team level processes.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

The submitting author warrants that the submission is original and that she/he is the author of the submission together with the named co-authors; to the extend the submission incorporates text passages, figures, data, or other material from the work of others, the submitting author has obtained any necessary permission.

Articles in this journal are published under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY What does this mean? ). This is to get more legal certainty about what readers can do with published articles, and thus a wider dissemination and archiving, which in turn makes publishing with this journal more valuable for you, the authors.

Patima Jeerapaet

Patima Jeerapaet is a graduate of the Ph.D. OD Program at Assumption University. He is also the chairman of the Joint Foreign Chamber of Commerce in Thailand (JFCCT).

Similar Articles

- Nattaya Chokekanoknapa, Strengthening Organizational Effectiveness through an ODI on Performance Management at the Departmental Level: A Case Study , AU-GSB e-JOURNAL: Vol. 4 No. 1 (2011): AU-GSB e-JOURNAL (June 2011)

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this article.

OD Interventions: Catalyzing Organizational Transformation

Table of Contents

Organizational Development (OD) interventions are purposeful actions and strategies designed to drive positive change within an organization. In this blog, we’ll delve into the significance of OD interventions, common types, and how they contribute to organizational transformation.

Understanding OD Interventions:

What are od interventions.

OD interventions are deliberate activities and initiatives aimed at improving an organization’s performance, culture, and effectiveness. They are structured approaches to bring about desired changes within the organization, aligning it with strategic goals and fostering growth and adaptability.

Types of OD Interventions:

OD interventions can take various forms, tailored to address specific organizational challenges and goals. Here are some common types:

1. Team Building:

- Team building interventions focus on improving communication, collaboration, and cohesion among teams. Activities may include team workshops, retreats, and problem-solving exercises.

2. Leadership Development:

- These interventions aim to enhance leadership skills and capabilities at all levels of the organization. Leadership development programs often involve training, coaching, and mentoring.

3. Change Management:

- Change management interventions assist in navigating and implementing organizational changes smoothly. They include strategies for communication, stakeholder engagement, and resistance management.

4. Process Consultation:

- Process consultation involves working with employees to analyze and improve existing processes and workflows. It encourages employees to identify areas for enhancement and develop solutions.

5. Cultural Interventions:

- Cultural interventions focus on shaping and nurturing the organizational culture. They may involve initiatives to promote diversity and inclusion, values alignment, and ethical behavior.

6. Organizational Design:

- Organizational design interventions explore and modify the structure, roles, and responsibilities within the organization. They aim to enhance efficiency and alignment with strategic goals.

7. Strategic Planning:

- These interventions facilitate the development and execution of strategic plans. They include activities such as visioning sessions, goal setting, and strategy alignment.

8. Conflict Resolution:

- Conflict resolution interventions address interpersonal or team conflicts within the organization. They help identify root causes and implement strategies for resolution.

The Role of OD Interventions:

1. driving change:.

- OD interventions serve as catalysts for change by providing a structured framework for planning and implementing organizational improvements.

2. Engaging Employees:

- They engage employees at all levels, fostering a sense of ownership and involvement in the change process.

3. Aligning with Strategy:

- OD interventions ensure that changes align with the organization’s strategic goals and long-term vision.

4. Measuring Progress:

- They provide mechanisms for tracking and measuring the impact of change initiatives, allowing for continuous improvement.

5. Enhancing Adaptability:

- OD interventions equip organizations with the tools and capabilities to adapt to evolving market conditions and challenges.

The Process of OD Interventions:

OD interventions typically follow a structured process:

1. Assessment:

- The organization assesses its current state, identifying areas for improvement and setting clear goals.

2. Planning:

- A detailed plan is developed, outlining the specific intervention strategies, timelines, and resources required.

3. Implementation:

- The interventions are executed according to the plan, involving employees and stakeholders as needed.

4. Evaluation:

- The impact of the interventions is assessed through data collection and analysis, and adjustments are made as necessary.

5. Sustainability:

- Successful interventions are integrated into the organizational culture and processes to ensure long-term sustainability.

Conclusion:

OD interventions are instrumental in catalyzing organizational transformation. They provide a structured approach to address challenges, improve performance, and foster a culture of continuous learning and growth. By engaging employees and aligning with strategic goals, OD interventions empower organizations to thrive in a dynamic and evolving business environment.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you! 😔

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Management Functions and Organisational Processes

1 Management: An Overview

- Meaning and Definition of Management

- Nature of Management

- Characteristics of Management

- Administration and Management

- The Importance of Management

- Functions of Management

- Challenges of Management

2 Management and its Evolution

- Perspectives of Management