Too much homework? New CA bill aims to ease the load on students

Having less homework would be beneficial for some students like Kyan Vanderweel, a San Luis Obispo high school student.

With multiple band and orchestra practices a day, on top of taking AP classes, Vanderweel finds it difficult to balance the things he loves to do with what he needs to get done, saying it even affects his mental health.

“AP classes should have homework but only a limited amount but in my opinion, I don’t think English classes apart from reading should have any unnecessary homework,” Vanderweel said.

Vanderweel says his homework and classwork are very repetitive and he feels it's unnecessary to do some of the homework.

“By the end of the day, we already know what we're doing so I feel like it’s a waste of time to an extent,” Vanderweel said.

Other students feel like homework in high school is bearable.

“I think I'm pretty comfortable with how it is right now,” San Luis Obispo High School student Tamiyah Murrieta said.

The "Healthy Homework Act,” introduced by Assemblywoman Pilar Schiavo, would not ban homework altogether but would require local school boards and educational agencies to establish policies that consider impacts on students’ physical and mental health with input from parents, teachers and students.

This is something Tyler Gerbel, a San Luis Obispo high school student, says could impact some students.

“Homework has been shown to stress students out a little bit. I’ve felt that myself when I have so much work to do,” Gerbel said.

Although he thinks his workload is manageable right now, he understands how some might have it harder.

“If something is done to limit the homework it might relieve stress off of students and I feel like mental health is a very important thing for students today,” Gerbel said.

The bill is also tailored to people who might not have access to resources at home like high-speed internet.

The bill would require the adopted policy to be updated at least once every five years.

It is currently making its way through the State Legislature.

Sign up for the Headlines Newsletter and receive up to date information.

Now signed up to receive the headlines newsletter..

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

by Jacob Sweet

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

Most Popular

Take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, red lobster’s mistakes go beyond endless shrimp, 20 years of bennifer, explained, cholera is making a comeback — and the world doesn’t have enough vaccines, the air quality index and how to use it, explained, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in The Highlight

Social media platforms aren’t equipped to handle the negative effects of their algorithms abroad. Neither is the law.

The real science behind the billionaire pursuit of immortality

If you want to belong, find a third place

America’s prison system is turning into a de facto nursing home

The one huge obstacle standing in the way of progress on gene-editing medicine

We can make birth safer for Black mothers. Here’s how.

The enormous stakes of India’s election

One explanation for the 2024 election’s biggest mystery

The obscure federal intelligence bureau that got Vietnam, Iraq, and Ukraine right

The Comstock Act, the long-dead law Trump could use to ban abortion, explained

Red Lobster’s mistakes go beyond endless shrimp Audio

New California bill pushes for schools to give less homework

S AN FRANCISCO (KRON) — How much homework is too much homework? A new California bill introduced in the State Assembly asserts that giving elementary school students hefty amounts of homework does not result in higher academic achievement.

Assemblywoman Pilar Schiavo presented the the Healthy Homework Act, AB 2999, in the Assembly Education Committee on Wednesday. The legislation is aimed at developing updated homework guidelines across California school districts. It would mandate school boards to establish homework policies that support and consider impacts to students’ mental and physical health.

Assemblywoman Schiavo said, “As a single parent, I know how stressful homework time can be for our kids and the entire family. The Healthy Homework Act is about ensuring that our homework policies are healthy for our kids, address the needs of the whole child, and also support family time, time to explore other extra-curricular interests, and give students and families time to connect and recover from the day.”

The assemblywoman’s office said research studies found:

- For elementary school pupils, there was no correlation between the amount of time spent on homework and achievement. Students who completed more homework were no more likely than their peers to earn higher grades and scores in school.

- For middle and high school students, research found an increase in academic performance when middle schoolers did up to one hour of homework, and high schoolers did up to two hours daily. These effects began to fade as students did more than two hours of work, and more time spent on homework did not necessarily equate to higher academic achievement.

Research findings in AB 2999 state, “The quality of homework assignments is more important than the quantity of work assigned, and that when pupils find homework interesting, relevant, and valuable, they are more likely to complete it.”

AB 2999 encourages school districts to enact policies that are developmentally appropriate based on grade level, and consider if homework should be optional or not graded in order to reduce pressure.

Schiavo said, “We know homework is a top three stressor in kids’ overall lives. We are in the middle of a student mental health crisis. It’s critical we incorporate homework practices into this discussion to relieve student stress, especially with something we could profoundly impact almost overnight.”

Schiavo announced the bill during a news conference held outside the Capitol Building with teachers on Wednesday. Teacher Casey Cuny, who was named 2023 California Teacher of The Year, said, “This bill will create the space for districts and teachers to have intentional conversations about best practices for homework.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KRON4.

When homework is busywork

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Rachel Bennett, 12, loves playing soccer, spending time with her grandparents and making jewelry with beads. But since she entered a magnet middle school in the fall -- and began receiving two to four hours of homework a night -- those activities have fallen by the wayside.

“She’s only a kid for so long,” said her father, Alex Bennett, of Silverado Canyon. “There’s been tears and frustration and family arguments. Everyone gets burned out and tired.”

Bennett is part of a vocal movement of parents and educators who contend that homework overload is robbing children of needed sleep and playtime, chipping into family dinners and vacations and overly stressing young minds. The objections have been raised for years but increasingly, school districts are listening. They are banning busywork, setting time limits on homework and barring it on weekends and over vacations.

“Groups of parents are going to schools and saying, ‘Get real. We want our kids to have a life,’ ” said Cathy Vatterott, an associate education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who has studied the issue.

Trustees in Danville, Calif., eliminated homework on weekends and vacations last year. Palo Alto officials banned it over winter break. Officials in Orange, where Rachel Bennett attends school, are reminding teachers about limits on homework and urging them not to assign it on weekends. A private school in Hollywood has done away with book reports.

“As adults, if every book we ever read, we had to write a report on -- would that encourage our reading or discourage it?” asked Eileen Horowitz, head of school at Temple Israel of Hollywood Day School. “We realized we needed to rethink that.”

Nancy Ortenberg is happy about the change.

“Homework is much more meaningful now,” said Ortenberg, whose daughter Isabelle, 9, was in school before the policy took effect in 2007. Before the change, it was a chore for her daughter, but “now she reads for the pure joy of reading.”

Homework was once hugely controversial. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, social commentators and physicians crusaded against it, convinced it was causing children to become wan, weak and nervous.

In a 1900 article titled “A National Crime at the Feet of American Parents” in the Ladies’ Home Journal, editor Edward Bok wrote, “When are parents going to open their eyes to this fearful evil? Are they as blind as bats, that they do not see what is being wrought by this crowning folly of night study?”

California was at the vanguard of the anti-homework movement. In 1901, the California Legislature banned it for students under 15 and ordered high schools to limit it for older students to 20 recitations a week. The law was taken off the books in 1917.

Homework has fallen in and out of favor ever since, often viewed as a force for good when the nation feels threatened -- after the Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957, for example, and during competition with Japan in the 1980s.

The homework wars have reignited in recent years, with parents around the nation arguing that children are being given too much.

Much of the debate is driven by the belief that today’s students are doing more work at home than their predecessors. But student surveys do not bear that out, said Brian Gill, a senior social scientist with Mathematica Policy Research.

Instead, in today’s increasingly competitive race for college admission, student schedules are increasingly packed with clubs, sports and other activities in addition to homework, Gill said. Students -- and parents -- may just have less time, he said.

Not all object, however.

“Obviously we want to think it’s busywork, but most of the time it’s really helpful,” said Allison Hall, 16, a junior at Villa Park High in the Orange district. Allison, who is taking five Advanced Placement classes, has up to three hours of homework a night; she also is on the cross country, track and mock trial teams and does volunteer work.

But others say there is just too much, especially for younger children. Karen Adnams of Villa Park has four children. She said that heavier course loads make sense for older children but that she doesn’t understand the amount of work given in lower grades.

“I think teachers have lost touch with what a third-grader or a fifth-grader can really do,” she said.

Vatterott, a former principal, said she became interested in the subject a decade ago as a frustrated parent. Her son, who has a learning disability, was upset by assignments he didn’t understand and couldn’t complete in a reasonable time.

She decided to study the effectiveness of homework. That research showed that more time spent on such work was not necessarily better.

Vatterott questioned the quantity and the quality of assignments. If 10 math problems could demonstrate a child’s grasp of a concept, why assign 50, she asked? The solution, she said, was not to do away with homework but to clarify the reasons for assigning it.

Some schools, among them Grant Elementary in Glenrock, Wyo., have gone further. Principal Christine Hendricks had grown concerned that students were spending too much time on busywork and that homework was causing conflicts between parents and children and between teachers and students. So she got rid of it last year except for reading and studying for tests.

“My philosophy, even when I was a teacher, is if you work hard during the day, I don’t like to work at night. Kids are kind of the same way,” she said.

Other districts, including San Ramon Valley Unified in Danville, Calif., have taken a more nuanced approach.

Since San Ramon revised its homework policy last year, the youngest students are given no more than 30 minutes a night; high school students have up to three hours of work. District trustees also decided that aside from reading, no homework should be given to elementary and middle school students on weekends or vacations.

In the Orange Unified School District, trustee John Ortega grew concerned about the workload carried by his middle school daughter. “We would have a swim meet all weekend, and she would be worried about coming home and having to finish homework,” he said. “She was stressed about it.”

After speaking with other parents, Ortega raised the subject publicly in the fall, prompting a series of discussions in the district. It turned out that although the board had set limits on homework, they were not always followed, said Marsha Brown, assistant superintendent of educational services. She said teachers have now been informed about the policy and principals are working to clarify the purpose of homework.

Brown said children’s social growth must be nurtured alongside their academic development. “We don’t want just academic children. We want them involved in sports and music and art and family time and downtime,” she said. “We want well-rounded citizens. I think we will always be struggling with that balance.”

Seema Mehta is a veteran political writer who is covering the 2024 presidential race as well as other state and national contests. She started at the Los Angeles Times in 1998, previously covered multiple presidential, state and local races, and completed a Knight-Wallace fellowship at the University of Michigan in 2019.

More From the Los Angeles Times

UCLA, UC Davis brace for strike as union alleges free speech violations in pro-Palestinian protests

May 28, 2024

Commentary: Here’s how to actually show appreciation for teachers

May 25, 2024

LAUSD caves to public outcry: No more timed testing for 4-year-olds

May 24, 2024

UC worker strike to hit UCLA, Davis next. A looming question: Is this walkout legal?

- by Heather Kemp

- July 23, 2021 July 21, 2021

New report considers California’s homework gap

- Closing the Achievement Gap

More than 1.6 million children across California did not have high-speed internet access at home prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new report.

“ Closing the Homework Gap in California ” — released in June by the Alliance for Excellent Education, the Small School Districts’ Association and the Linked Learning Alliance — analyzes data from the 2019 American Community Survey.

“This digital divide — also described as the ‘homework gap’— spans across California, but it disproportionately impacts children of color and those living in rural areas and in low-income families,” the report states. “Research shows that, regardless of race or socioeconomic status, middle and high school students who lack high-speed home internet access have poorer academic outcomes than their connected peers.”

The students who lacked access experienced lower grade point averages, less advanced digital skills and were not as likely to attend college. Upwards of 745,500 children were without a computer in 2019 and 8.4 percent of households did not have a computer, according to the report.

While pandemic-related school closures underscored the need for reliable, high-speed internet in homes and the expansion of distance learning fast tracked efforts by the state and local educational agencies to provide students with items like computers, tablets and WiFi hotspots, there remains progress to be made, the report states.

Districts large and small worked tirelessly to get their students connected at appropriate speeds, but “the depth of the homework gap and its disproportionate impact on rural families, low-income families, and families of color indicate that California’s schools need additional investments to ensure all children have the high-speed home internet access required for a 21st-century education.”

While the data may be dated in light of recent progress made, Latino children remain one of the groups most lacking in access to high-speed home internet and devices, and significant gaps persist by region

Geographically, the percentage of households without high-speed home internet access was much higher in non-metropolitan/rural areas than metropolitan locations at 27.5 percent compared to 18.4 percent. The same was found for the percentage of households without a computer as 11.3 percent of non-metropolitan/rural did not have one compared to 8.3 percent for metropolitan areas. LEAs in more urban counties do substantially contribute to the homework gap, however.

“Together, Los Angeles County and neighboring San Bernardino County account for more than 550,000 children without high-speed home internet access and more than 245,000 children without home computers,” the report states. “This means that about one-third of California’s children without broadband internet or devices at home live in these two counties alone.”

The state’s northern rural counties, including Del Norte, Lassen, Modoc and Humboldt, also account for more than one-third of households with children do not have high-speed internet. Meanwhile, in central Madera County, nearly four in 10 households with children do not have high-speed internet access — the highest percentage statewide. “Collectively, more than 80,000 children who live in rural California communities do not have high-speed internet access at home,” according to the report.

Progress prompted by the pandemic

The authors call on state policymakers to provide the financial and technical investments necessary to help ensure that all students have high-speed internet access and devices for schoolwork — a plea that has been at least partially answered due to the public health crisis.

The organizations who presented the report urged California lawmakers to use state funds and federal funds from the American Rescue Plan to make a one-time investment of $7 billion toward the cause, as was proposed in the revised state budget proposal.

They also voiced support for Assembly Bill 34 , the Broadband for All Act of 2022, and said U.S. Congress should continue to fund the Emergency Broadband Benefit and the Emergency Connectivity Fund so the cost of high-speed internet and computers isn’t a barrier to learning.

“COVID-19 did not create California’s homework gap. However, if state lawmakers do not take steps now to close this digital divide, students without home internet access and devices will fall even further behind their connected peers long after the pandemic ends,” the report states. “California’s students deserve this investment today to ensure their future success.”

On July 20, AB 156 , the broadband trailer bill, was signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom authorizing $6 billion in spending over the next three years to expand the state’s broadband fiber infrastructure and increase internet connectivity throughout communities.

Related Posts

Parental attitudes toward attendance may be a factor in difficulties reducing chronic absenteeism

Survey of college and career prep shows gaps persist along poverty lines, school size

New briefs detail best and worst practices in serving English learners and immigrant-origin students

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

When Homework Was Banned

Published: November 3, 2023

In the early 1900s, Ladies' Home Journal took up a crusade against homework, enlisting doctors and parents who say it damages children's health. In 1901 California passed a law abolishing homework!

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Surprising History of Homework Reform

Really, kids, there was a time when lots of grownups thought homework was bad for you.

Homework causes a lot of fights. Between parents and kids, sure. But also, as education scholar Brian Gill and historian Steven Schlossman write, among U.S. educators. For more than a century, they’ve been debating how, and whether, kids should do schoolwork at home .

At the dawn of the twentieth century, homework meant memorizing lists of facts which could then be recited to the teacher the next day. The rising progressive education movement despised that approach. These educators advocated classrooms free from recitation. Instead, they wanted students to learn by doing. To most, homework had no place in this sort of system.

Through the middle of the century, Gill and Schlossman write, this seemed like common sense to most progressives. And they got their way in many schools—at least at the elementary level. Many districts abolished homework for K–6 classes, and almost all of them eliminated it for students below fourth grade.

By the 1950s, many educators roundly condemned drills, like practicing spelling words and arithmetic problems. In 1963, Helen Heffernan, chief of California’s Bureau of Elementary Education, definitively stated that “No teacher aware of recent theories could advocate such meaningless homework assignments as pages of repetitive computation in arithmetic. Such an assignment not only kills time but kills the child’s creative urge to intellectual activity.”

But, the authors note, not all reformers wanted to eliminate homework entirely. Some educators reconfigured the concept, suggesting supplemental reading or having students do projects based in their own interests. One teacher proposed “homework” consisting of after-school “field trips to the woods, factories, museums, libraries, art galleries.” In 1937, Carleton Washburne, an influential educator who was the superintendent of the Winnetka, Illinois, schools, proposed a homework regimen of “cooking and sewing…meal planning…budgeting, home repairs, interior decorating, and family relationships.”

Another reformer explained that “at first homework had as its purpose one thing—to prepare the next day’s lessons. Its purpose now is to prepare the children for fuller living through a new type of creative and recreational homework.”

That idea didn’t necessarily appeal to all educators. But moderation in the use of traditional homework became the norm.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

“Virtually all commentators on homework in the postwar years would have agreed with the sentiment expressed in the NEA Journal in 1952 that ‘it would be absurd to demand homework in the first grade or to denounce it as useless in the eighth grade and in high school,’” Gill and Schlossman write.

That remained more or less true until 1983, when publication of the landmark government report A Nation at Risk helped jump-start a conservative “back to basics” agenda, including an emphasis on drill-style homework. In the decades since, continuing “reforms” like high-stakes testing, the No Child Left Behind Act, and the Common Core standards have kept pressure on schools. Which is why twenty-first-century first graders get spelling words and pages of arithmetic.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

Building Classroom Discussions around JSTOR Daily Syllabi

Scaffolding a Research Project with JSTOR

Making Implicit Racism

The Diverse Shamanisms of South America

Recent posts.

- Palestinians against Fascism

- Dopamine, Hummus, and Iranian Politics

- Finding Lucretia Howe Newman Coleman

- The Novels that Taught Americans about Abortion

- Humans for Voyage Iron: The Remaking of West Africa

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Official website of the State of California

Resources for California

- Key services

- Health insurance or Medi-Cal

- Business licenses

- Food & social assistance

- Find a CA state job

- Vehicle registration

- Digital vaccine record

- Traffic tickets

- Birth certificates

- Lottery numbers

- Unemployment

- View all CA.gov services

- Popular topics

- Building California

- Climate Action

- Mental health care for all

California Bans Book Bans and Textbook Censorship in Schools

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW: Governor Newsom signed AB 1078 (Jackson) to ban book bans and textbook censorship in the state’s 10,000+ schools.

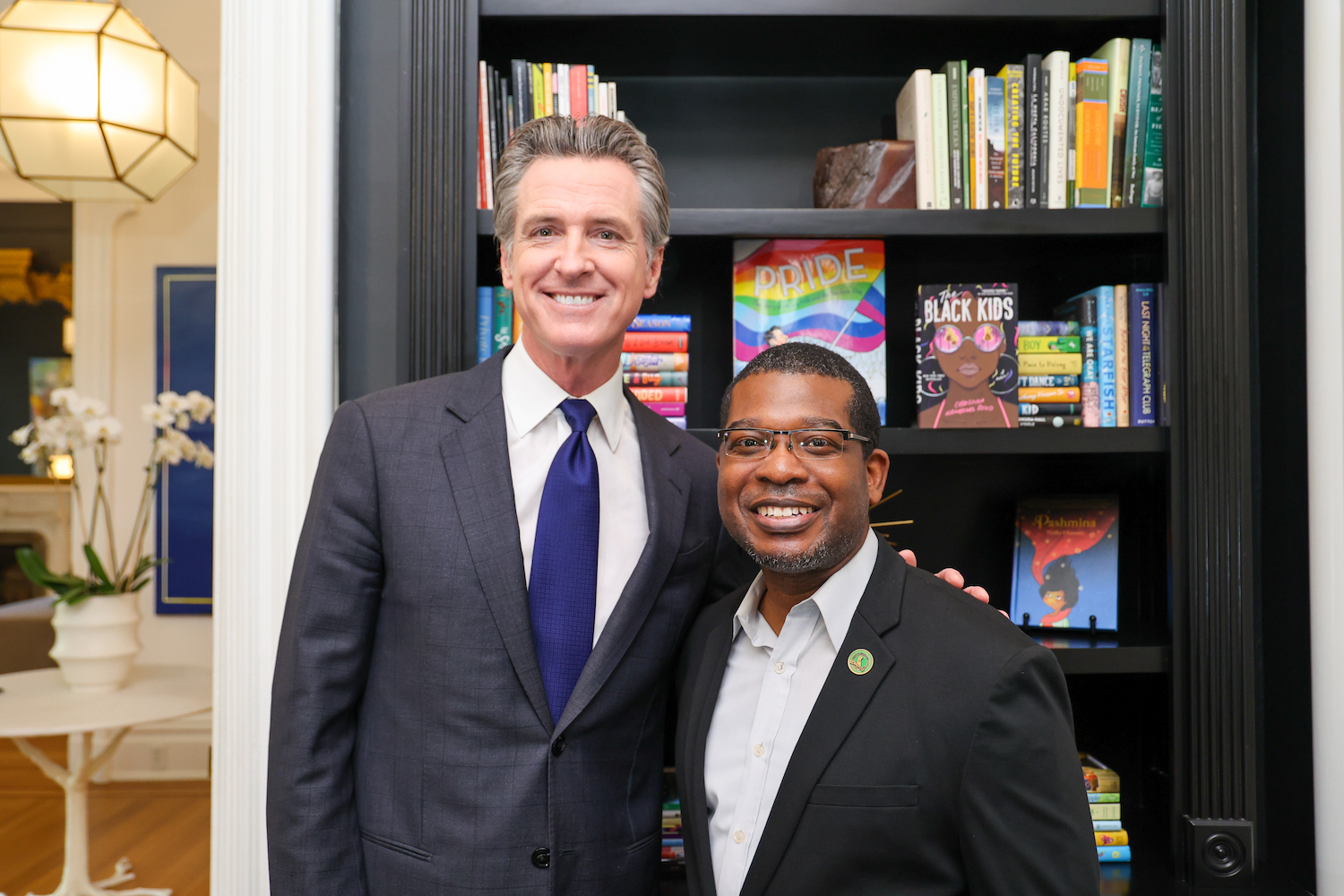

SACRAMENTO — Building on his Family Agenda to promote educational freedom and success, Governor Gavin Newsom today signed AB 1078 by Assemblymember Dr. Corey Jackson (D-Moreno Valley), which bans “book bans” in schools, prohibits censorship of instructional materials, and strengthens California law requiring schools to provide all students access to textbooks that teach about California’s diverse communities.

WHAT GOVERNOR NEWSOM SAID: “From Temecula to Tallahassee, fringe ideologues across the country are attempting to whitewash history and ban books from schools. With this new law, we’re cementing California’s role as the true freedom state: a place where families — not political fanatics — have the freedom to decide what’s right for them.”

“When we restrict access to books in school that properly reflect our nation’s history and unique voices, we eliminate the mirror in which young people see themselves reflected, and we eradicate the window in which young people can comprehend the unique experiences of others,” said First Partner Jennifer Siebel Newsom. “In short, book bans harm all children and youth, diminishing communal empathy and serving to further engender intolerance and division across society. We Californians believe all children must have the freedom to learn about the world around them and this new law is a critical step in protecting this right.”

“It is the responsibility of every generation to continue the fight for civil and human rights against those who seek to take them away,” said Assemblymember Dr. Corey Jackson. “Today, California has met this historical imperative and we will be ready to meet the next one.”

“AB 1078 sends a strong signal to the people of California — but also to every American — that in the Golden State — we don’t ban books — we cherish them,” said State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond . “This law will serve as a model for the nation that California recognizes and understands the moment we are in – and while some want to roll back the clock on progress, we are doubling down on forward motion. Rather than limiting access to education and flat out banning books like other states, we are embracing and expanding opportunities for knowledge and education, because that’s the California way.”

Governor Newsom and Assemblymember Dr. Corey Jackson

AB 1078 provides the Superintendent of Public Instruction the authority to buy textbooks for students in a school district, recoup costs, and assess a financial penalty if a school board willfully chooses to not provide sufficient standards-aligned instructional materials for students. The law also prohibits school boards from banning instructional materials or library books on the basis that they provide inclusive and diverse perspectives in compliance with state law.

While other states ban books, California is making tens of billions of dollars in strategic investments to improve education outcomes and literacy. California outperformed most states — including Florida and Texas — in mitigating learning loss during the pandemic, and through historic levels of school funding, the state is building a cohesive structure of support for educators and students that reflects a focus on equity, inclusion, and academic success.

As part of the Governor’s Family Agenda, California is ensuring parents and caregivers have the opportunity to actively participate in their children’s education. Parents in California have a seat at the decision-making table for key budget, programmatic, and curricular decisions, including the creation of Local Control and Accountability Plans. In the past two years, in partnership with the Legislature, Governor Newsom has required schools to make it easier for working parents to participate in school decisions, invested $4.1 billion to convert one in four schools into community schools with deeper parent engagement, and invested another $100 million in the Community Engagement Initiative for more proactive collaboration with parents.

California provides instruction and support services to roughly 5.9 million students in grades transitional kindergarten through twelve in more than 1,000 districts and over 10,000 schools throughout the state. Education funding in the state is at a record high, totaling $129.2 billion in the 2023-24 budget.

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

The end of homework? Why some schools are banning homework

Fed up with the tension over homework, some schools are opting out altogether.

No-homework policies are popping up all over, including schools in the U.S., where the shift to the Common Core curriculum is prompting educators to rethink how students spend their time.

“Homework really is a black hole,” said Etta Kralovec, an associate professor of teacher education at the University of Arizona South and co-author of “The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning.”

“I think teachers are going to be increasingly interested in having total control over student learning during the class day and not relying on homework as any kind of activity that’s going to support student learning.”

College de Saint-Ambroise, an elementary school in Quebec, is the latest school to ban homework, announcing this week that it would try the new policy for a year. The decision came after officials found that it was “becoming more and more difficult” for children to devote time to all the assignments they were bringing home, Marie-Ève Desrosiers, a spokeswoman with the Jonquière School Board, told the CBC .

Kralovec called the ban on homework a movement, though she estimated just a small handful of schools in the U.S. have such policies.

Gaithersburg Elementary School in Rockville, Maryland, is one of them, eliminating the traditional concept of homework in 2012. The policy is still in place and working fine, Principal Stephanie Brant told TODAY Parents. The school simply asks that students read 30 minutes each night.

“We felt like with the shift to the Common Core curriculum, and our knowledge of how our students need to think differently… we wanted their time to be spent in meaningful ways,” Brant said.

“We’re constantly asking parents for feedback… and everyone’s really happy with it so far. But it’s really a culture shift.”

It was a decision that was best for her community, Brant said, adding that she often gets phone calls from other principals inquiring how it’s working out.

The VanDamme Academy, a private K-8 school in Aliso Viejo, California, has a similar policy , calling homework “largely pointless.”

The Buffalo Academy of Scholars, a private school in Buffalo, New York, touts that it has called “a truce in the homework battle” and promises that families can “enjoy stress-free, homework-free evenings and more quality time together at home.”

Some schools have taken yet another approach. At Ridgewood High School in Norridge, Illinois, teachers do assign homework but it doesn’t count towards a student’s final grade.

Many schools in the U.S. have toyed with the idea of opting out of homework, but end up changing nothing because it is such a contentious issue among parents, Kralovec noted.

“There’s a huge philosophical divide between parents who want their kids to be very scheduled, very driven, and very ambitiously focused at school -- those parents want their kids to do homework,” she said.

“And then there are the parents who want a more child-centered life with their kids, who want their kids to be able to explore different aspects of themselves, who think their kids should have free time.”

So what’s the right amount of time to spend on homework?

National PTA spokeswoman Heidi May pointed to the organization’s “ 10 minute rule ,” which recommends kids spend about 10 minutes on homework per night for every year they’re in school. That would mean 10 minutes for a first-grader and an hour for a child in the sixth grade.

But many parents say their kids must spend much longer on their assignments. Last year, a New York dad tried to do his eight-grader’s homework for a week and it took him at least three hours on most nights.

More than 80 percent of respondents in a TODAY.com poll complained kids have too much homework. For homework critics like Kralovec, who said research shows homework has little value at the elementary and middle school level, the issue is simple.

“Kids are at school 7 or 8 hours a day, that’s a full working day and why should they have to take work home?” she asked.

Follow A. Pawlowski on Google+ and Twitter .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Should we get rid of homework? Why, or why not?

Is homework an outdated, ineffective or counterproductive tool for learning? Do you agree with the authors of the paper that homework is harmful and worsens inequalities that exist between students’ home circumstances?

Or do you agree with Mr. Kang that homework still has real educational value?

When you get home after school, how much homework will you do? Do you think the amount is appropriate, too much or too little? Is homework, including the projects and writing assignments you do at home, an important part of your learning experience? Or, in your opinion, is it not a good use of time? Explain.

In these letters to the editor , one reader makes a distinction between elementary school and high school:

Homework’s value is unclear for younger students. But by high school and college, homework is absolutely essential for any student who wishes to excel. There simply isn’t time to digest Dostoyevsky if you only ever read him in class.

What do you think? How much does grade level matter when discussing the value of homework?

Is there a way to make homework more effective?

If you were a teacher, would you assign homework? What kind of assignments would you give and why?

Want more writing prompts? You can find all of our questions in our Student Opinion column . Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate them into your classroom.

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

Will Less Homework Stress Make California Students Happier?

A bill from a member of the Legislature’s happiness committee would require schools to come up with homework policies that consider the strain on students.

Mario Ramirez Garcia does homework on April 23, 2021. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters -->

BY LYNN LA, CalMatters

Update: The Assembly education committee on April 24 approved an amended version of the bill that softens some requirements and gives districts until the 2027-28 school year. Some bills before California’s Legislature don’t come from passionate policy advocates, or from powerful interest groups.

Sometimes, the inspiration comes from a family car ride.

While campaigning two years ago, Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo ’s daughter, then nine, asked from the backseat what her mother could do if she won.

Schiavo answered that she’d be able to make laws. Then, her daughter Sofia asked her if she could make a law banning homework.

“It was a kind of a joke,” the Santa Clarita Valley Democrat said in an interview, “though I’m sure she’d be happy if homework were banned.”

Still, the conversation got Schiavo thinking, she said. And while Assembly Bill 2999 — which faces its first big test on Wednesday — is far from a ban on homework, it would require school districts, county offices of education and charter schools to develop guidelines for K-12 students and would urge schools to be more intentional about “good,” or meaningful homework.

Among other things, the guidelines should consider students’ physical health, how long assignments take and how effective they are. But the bill’s main concern is mental health and when homework adds stress to students’ daily lives.

Homework’s impact on happiness is partly why Schiavo brought up the proposal last month during the first meeting of the Legislature’s select committee on happiness , led by former Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon .

“This feeling of loneliness and disconnection — I know when my kid is not feeling connected,” Schiavo, a member of the happiness committee, told CalMatters. “It’s when she’s alone in her room (doing homework), not playing with her cousin, not having dinner with her family.”

'I feel that I should teach them what I need to teach them when I’m with them in the room.' Casey Cuny, California Teacher of the Year

The bill analysis cites a survey of 15,000 California high schoolers from Challenge Success, a nonprofit affiliated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education. It found that 45% said homework was a major source of stress and that 52% considered most assignments to be busywork. The organization also reported in 2020 that students with higher workloads reported “symptoms of exhaustion and lower rates of sleep,” but that spending more time on homework did not necessarily lead to higher test scores.

Homework’s potential to also widen inequities is why Casey Cuny supports the measure. An English and mythology teacher at Valencia High School and 2024’s California Teacher of the Year , Cuny says language barriers, unreliable home internet, family responsibilities or other outside factors may contribute to a student falling behind on homework.

“I never want a kid’s grade to be low because they have divorced parents and their book was at their dad’s house when they were spending the weekend at mom’s house,” said Cuny, who plans to attend a press conference Wednesday to promote the bill.

In addition, as technology makes it easier for students to cheat — using artificial technology or chat threads to lift answers, for example — Schiavo says that the educators she has spoken to indicate they’re moving towards more in-class assignments.

Cuny agrees that an emphasis on classwork does help to rein in cheating and allows him to give students immediate feedback. “I feel that I should teach them what I need to teach them when I’m with them in the room,” he said.

Assemblymember Pilar Schiavo, far left, and other members of the Select Committee on Happiness and Public Policy Outcomes listen to speakers during an informational hearing on at the California Capitol in Sacramento on March 12, 2024. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

The bill says the local homework policies should have input from teachers, parents, school counselors, social workers and students; be distributed at the beginning of every school year; and be reevaluated every five years.

The Assembly Committee on Education is expected to hear the bill Wednesday. Schiavo says she has received bipartisan support and so far, no official opposition or support is listed in the bill analysis.

The measure’s provision for parental input may lead to disagreements given the recent culture war disputes between Democratic officials and parental rights groups backed by some Republican lawmakers. Because homework is such a big issue, “I’m sure there will be lively (school) board meetings,” Schiavo said.

Nevertheless, she says she hopes the proposal will overhaul the discussion around homework and mental health. The bill is especially pertinent now that the state is also poised to cut spending on mental health services for children with the passage of Proposition 1 .

Schiavo said the mother of a student with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder told her that the child’s struggle to finish homework has raised issues inside the house, as well as with the school’s principal and teachers.

“And I’m just like, it’s sixth grade!” Schaivo said. “What’s going on?”

Articles which extol the virtues of a report or article put out by a local newsroom.

Explainers and guides from our team of journalists, a curated news digest from trusted local newsrooms, and local government announcements and upcoming meetings, delivered every Monday morning to your inbox.

You are subscribed!

And look for our newsletter every Monday morning. See you then!

You're already subscribed

There was a problem with the submitted email address.

We can't subscribe you with the submitted email address. Please try another.

Make your Mondays more interesting and informative.

Thanks for visiting! GoodRx is not available outside of the United States. If you are trying to access this site from the United States and believe you have received this message in error, please reach out to [email protected] and let us know.

- Interactive

- Informative

- Ask the Gardener

- Boardgame Reviews

- Book Reviews

- Celebration of Life

- Christine’s Corner

- Dimple Bites

- Dimple Dash

- Fred’s Corn-ier

- In the Garden

- Non-Profit Spotlight

- Poetic Pauses

- Home & Garden

- Online Games

- Real Estate

- Senior Living

- Ask a gardener

- Become a Contributor

- Community Sponsors

- Reader’s Contest

February 2024 Horoscope

January 2024 horoscope, november 2023 horoscope, october 2023 horoscope, september 2023 horoscope.

Dive into a garlic-infused meal

Sandwich ideal for picnic dinners

March 2023 horoscope, february 2023 horoscope, trending tags.

Leaving Trouble Behind – Poetic Pauses

Rainbow – Poetic Pauses

White Lies – Poetic Pauses

Secrets ~ Acrostic Poem

The Trudgery of Life – Poetic Pauses

Christmas Sparkles – Poetic Pauses

Keep a Song in Your Heart – Poetic Pauses

Small Town Angels – Poetic Pauses

Adapt ~ An Acrostic Poem

Towns you can buy today

Valentine’s Day in other cultures is just as sweet

Foxgloves bring beauty and history to your garden

Groundhog Day captures imaginations

Unidentified objects leaving governments mystified amid alien speculation

Goliath versus Goliath? AI copyright battles blow up

What will happen in 2024?

Go into Debt for a Wedding? Nope! – Dave Says

Risk is real – dave says.

- This Day in History

Strange But True – In 1901 California banned homework

Strange But True - In 1901 California banned homework

Request advertising info . View All .

* Maurice Sendak’s beloved kids’ classic “Where the Wild Things Are” was originally titled “Where the Wild Horses Are.” Why the change in title? Sendak realized he was unable to draw horses.

* Rapper Lil’ Wayne originally went by the moniker “Shrimp Daddy.”

You might also like

A simple test – fred’s corn-ier.

* Not ones to marry in haste and repent at leisure, a Paraguayan couple set up housekeeping in 1933. After 80 years, eight children and 50 grandchildren, the 103-year-old groom finally said a formal “I do” to his 99-year-old bride.

Advertisement - Story continues below

* The prize money for winning the Monopoly World Championship is $20,580 — the same amount of money there is in the game’s bank.

* Modern students who complain about the amount of homework they’re issued might well wish they’d lived in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when doctors crusaded against it because they believed it was causing children to become wan, weak and nervous. In 1901, California even banned homework for anyone under the age of 15.

* Over a 24-year career, Roman charioteer Gaius Appuleius Diocles amassed an astonishing fortune worth 35,863,120 sesterces (an ancient Roman coin), or roughly $15 billion in today’s dollars, making him the highest-paid athlete of all time.

* In January 2021, the first commercial 3D-printed house in the U.S. went on sale for $299,000.

* The term “rum bubber,” which originated in the 16th century, referred to a thief who specialized in stealing silver tankards from inns and pubs.

* An actual “chill pill,” which could even be made at home, was used in the late 1800s to remedy chills associated with a high fever. *** Thought for the Day: “We should live, act, and say nothing to the injury of anyone. It is not only best as a matter of principle, but it is the path to peace and honor.” — Robert E. Lee

(c) 2022 King Features Synd., Inc.

Trending Video

Contaminated drinking water at u.s. bases – veterans post, trivia test: a little color, lucie winborne.

Strange but True (c) 2022 King Features Synd., Inc.

Related Posts

The Medical Game – Fred’s Corn-ier

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Keep up to date

Choose Your News

- View Digital Issues

- Reader’s Contest

Recent Post

Lost Piece – Poetic Pauses

© 2021 Dimple Times is a division of E-Quiver, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Visit our other publication, The Pickaway Cultivator for "Adventures, Bucket List and Community" and it's all about Pickaway County, Ohio. Website Design and Hosting by Calebweb.com for Pickaway, Fairfield, Fayette and Ross County.

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Privacy Overview

- One email, all the Golden State news

- Get the news that matters to all Californians. Start every week informed.

- Newsletters

- Environment

- 2024 Voter Guide

- Digital Democracy

- Daily Newsletter

- Data & Trackers

- California Divide

- CalMatters for Learning

- College Journalism Network

- What’s Working

- Youth Journalism

- Manage donation

- News and Awards

- Sponsorship

- Inside the Newsroom

- CalMatters en Español

Higher Education

Hundreds arrested and suspended: How California colleges are disciplining faculty and students over protests

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Students and faculty protesting the Israel-Hamas war at universities throughout California are facing a range of consequences from arrests to suspensions and bans from campus. Meanwhile, students and faculty have also had to endure campus closures, canceled events, and classes moving online. What are the academic and legal costs of civil disobedience for California’s college protesters?

While some universities in California are negotiating with student protestors, hundreds of students and faculty throughout the state are facing legal and academic repercussions for protesting the Israel-Hamas war.

Protesters, who have largely been non-violent, have disrupted events, occupied buildings and public spaces, erected encampments, and skirmished with counterprotesters, resulting in university leaders citing campus policy violations and calling in law enforcement to forcefully remove protesters. According to a CalMatters analysis, at least 567 people, many of whom are students and faculty, have been disciplined by their universities or arrested since the Palestinian militant group Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, killing over 1,100 and sparking a counter-offensive by Israel that has killed 35,000 Palestinians.

For months, pro-Palestinians have been intent on forcing their universities to divest from weapons manufacturers and companies with ties to Israel, and pro-Israelis have insisted the language and actions of the pro-Palestinian groups have been creating anti-semitic environments.

At some campuses, students and faculty are facing consequences for what they see as engaging in their First Amendment rights to speech and to peaceably assemble. An unknown number of students have been suspended or warned of possible suspension, while other students and faculty have been arrested on suspicion of trespassing, attempted burglary and unlawful assembly. And although some campuses are dropping charges, students and faculty throughout California face long-term repercussions.

Students and faculty face legal consequences