- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

The Best Fiction Books » Historical Fiction

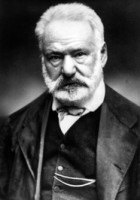

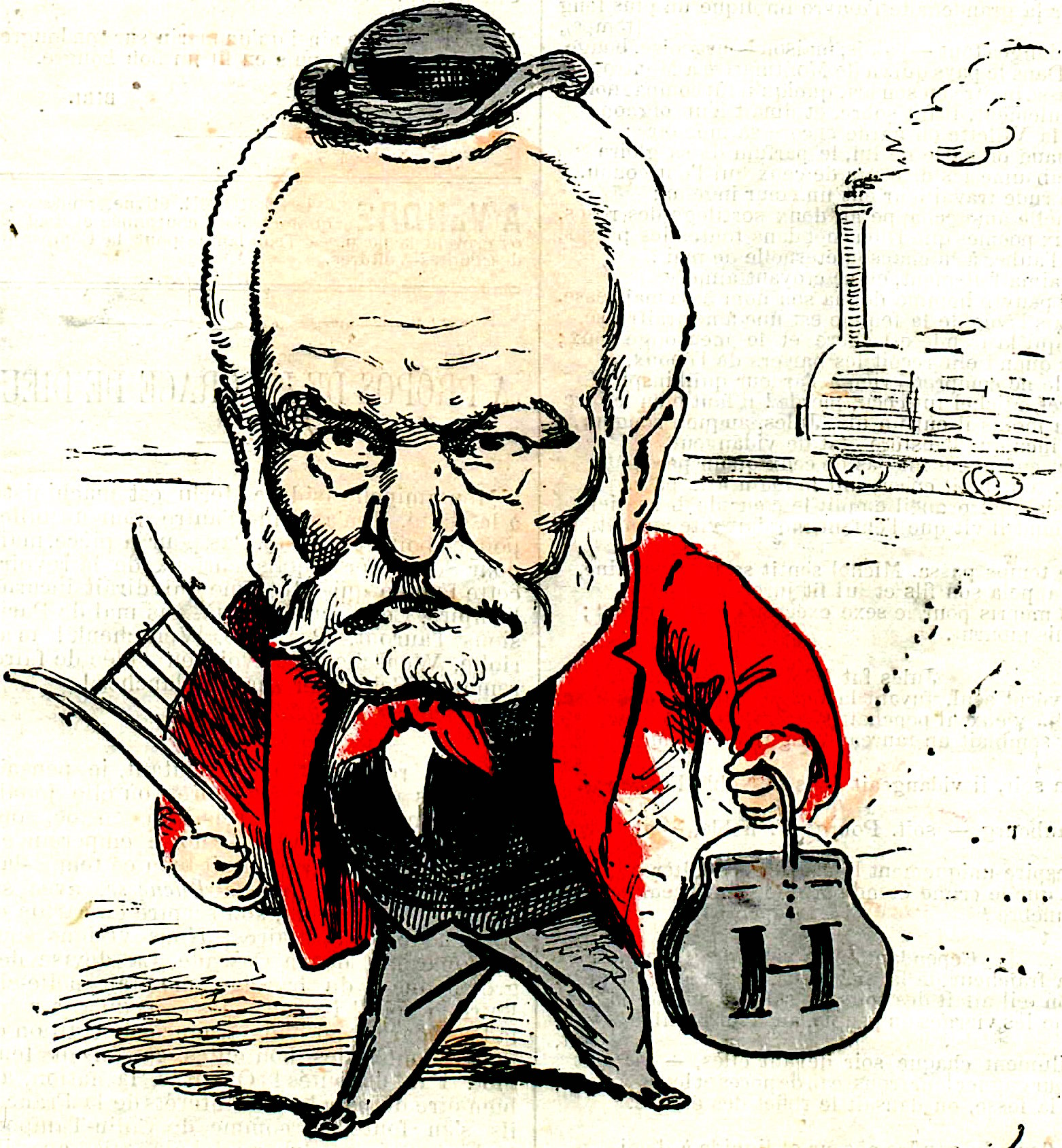

Les misérables, by victor hugo, recommendations from our site.

“Vividly illustrates two ideas about character. The first is that our characters can change over time, the second is that role models can be powerful sources of character change.” Read more...

The best books on Moral Character

Christian B Miller , Philosopher

“I read Les Misérables when I was a kid and then re-read it last summer and…I am now convinced that it is the greatest novel of all time. Every story in the world is somewhere in there. It’s extremely sentimental, it’s extremely historical and digressive, there are parts of it that are boring as hell – but that’s true of War and Peace and other great novels. Overall, it’s such a compendious, wonderful thing, full of gems…He was an opponent of Napoleon III who had seized power in a coup d’état in 1851 and turned what had been a left-wing revolution into a – not vicious – but very authoritarian right-wing regime, and Hugo, who was a leading figure in French politics, objected and the Emperor said ‘Out you go’; many hundreds, thousands, of opposition figures were exiled, imprisoned or executed at that time…He was in exile on the island of Guernsey from where he could almost see France on a clear day. And one big dimension of Les Misérables is it’s a novel of nostalgia – he’s trying to reconstruct the Paris of his youth which he didn’t know if he would ever see again. In a sense, he never would because most of it had been rebuilt during the Second Empire by the time he got back.” Read more...

The Greatest French Novels

David Bellos , Biographer

Other books by Victor Hugo

Notre-dame de paris by victor hugo, our most recommended books, green darkness by anya seton, war and peace by leo tolstoy, the name of the rose by umberto eco, wolf hall by hilary mantel, all quiet on the western front by erich maria remarque, the western wind: a novel by samantha harvey.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

Les Misérables by Victor Hugo: Book Review & Summary

Book: les misérables.

About the Author: Victor HugoPlease enable JavaScript Excerpts from the original textBook summary, book review, reading notes. If anything is horrible, if there is a reality that surpasses our worst dreams, it is this: to live, to see the sun, to be in full possession of manly vigor, to have health and joy, to laugh heartily, to rush toward a glory that lures you on, to feel lungs that breathe, a heart that beats, a mind that thinks, to speak, to hope, to love; to have mother, wife, children, to have sunlight, and suddenly, in less time than it takes to cry out, to plunge into an abyss, to fall, to roll, to crush, to be crushed, to see the heads of grain, the flowers, the leaves, the branches, unable to catch hold of anything, to feel your sword useless, men under you, horses over you, to struggle in vain, your bones were broken by some kick in the darkness, to feel a heel gouging your eyes out of their sockets, raging atthe horseshoe between your teeth, to stifle, to howl, to twist, to be under all this and to say, “Just then I was a living man!” ---Quoted on page 353 Do you prefer to listen rather than read? If so, here’s a nice opportunity to try Audible for 30 days. Need a bookish gift? Give the gift of reading to the book lovers in your life. 'ReadingAndThinking.com' content is reader-supported. "As an Amazon Associate, when you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.". Related PostExplore and find your next good read - Book Recommendations for specific interests. Explore and find your next Book Summary for specific interests. Explore and find Book Series for specific interests. Recent PostBook reviews, popular posts, 30 great books that will expand your knowledge and mind. Welcome to an insightful journey through the '30 great books that will expand your knowledge and mind,' written by Muhiuddin Alam o... 19 Books from Elon Musk's Reading List Recommended for Everyone30 hilariously most inappropriate children's books (adults), the moon and sixpence: book review, summary & analysis, books by subject, related topics. Advertisement Supported by The Legacy of ‘Les Misérables’: Charting the Life of a Classic

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission. By Tobias Grey

THE NOVEL OF THE CENTURY The Extraordinary Adventure of “Les Misérables” By David Bellos 307 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $27. A good book could be written about the bastardization of great novels, and Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” would make a fine Exhibit A. Rarely has any work of literature received such a pummeling at the hands of a succession of publishers, translators, filmmakers and musical impresarios, as David Bellos demonstrates in “The Novel of the Century,” his intriguing new history of Hugo’s 1,500-page masterpiece. “Les Misérables” was published in France in 1862. An English-language version appeared in New York that same year, thanks to a justly hailed translation that the American Egyptologist Charles Wilbour completed in only six months. But right away there were signs the novel would take on a life of its own: A pirated version of Wilbour’s translation was soon released in Richmond, Va., where the Union’s copyright laws did not apply. All of Hugo’s references to the evils of slavery were struck out. (“The absence of a few antislavery paragraphs will hardly be complained of by Southern readers,” the preface proposed.) Hugo’s doctored novel went on to become such an emphatic hit in the South that the downbeaten soldiers of Robert E. Lee took to calling themselves “Lee’s miserables.” There was distortion of another sort in the first British translation, by Sir Charles Lascelles Wraxall, also published in 1862. According to Bellos, Wraxall, a historian who fancied himself an expert on Waterloo, did not hesitate to alter the meaning of Hugo’s novel whenever he disagreed with passages pertaining to Napoleon Bonaparte’s downfall. Bellos also relates how filmmakers from around the world have betrayed the original by putting “back in what Hugo so pointedly omits” — namely, organized religion. Though Hugo professed to believe in God, he did not subscribe to any one faith and was determined, Bellos says, not to let the Catholic Church “think it has a role in the ‘indefinite but unshakable’ religious slant of ‘Les Misérables.’ ” Tom Hooper’s unfortunate decision to shoot some scenes of his 2012 musical adaptation in Winchester Cathedral ran contrary to the novel, which never once enters a church. We are having trouble retrieving the article content. Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings. Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times. Thank you for your patience while we verify access. Already a subscriber? Log in . Want all of The Times? Subscribe . Books: A true story Book reviews and some (mostly funny) true stories of my life. Book Review: Les Miserables by Victor HugoAugust 23, 2011 By Jessica Filed Under: Book Review 3 Comments Les MiserablesIntroducing one of the most famous characters in literature, Jean Valjean - the noble peasant imprisoned for stealing a loaf of bread - Les Misérables (1862) ranks among the greatest novels of all time. In it Victor Hugo takes readers deep into the Parisian underworld, immerses them in a battle between good and evil, and carries them onto the barricades during the uprising of 1832 with a breathtaking realism that is unsurpassed in modern prose. I read Les Miserables unabridged. I read it because I wanted to know what really happens at the end since this 1400 + page book is usually abridged. Call it the rebel in me, but why should I let someone else choose what I should read out of this book? Oh, you don’t think I can read the whole thing? WATCH ME. In addition to my rebelliousness, three separate people said to me with passion that I had to read Les Mis unabridged and I have to say it was worth it. The ending was amazing! It took me about 5 years to read it. I spent about 1 year actually reading it and 4 years convincing myself to read it. Cliffnotes were essential in me being able to finish it. Since I took long breaks from it, I would read all the summaries up to where I had stopped. The story has an epic feel to it, but the plot was often interrupted by what I called “political rants” that ran on for about 20-30 pages. These little rants are probably what gets edited out in abridged versions. You’d come across a nunnery in the narrative and Victor Hugo would go, “Speaking of nuns…” and ramble on for 30 pages about what exactly he thought about nuns. Here’s a list of the political essays (which I named myself) that he inserted into Les Mis:

What struck me the most about his essays was not how different the problems were back then, but how much they are the same . Don’t we still argue about politics and education today? Another thing that I noticed about the unabridged version was the fact that you got to learn the entire back story for almost every character you met. It added such depth and color to the story and made it truly unique. Content Rating : None About Victor Hugo Victor Marie Hugo (26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, novelist, and dramatist of the Romantic movement. He is considered one of the greatest and best known French writers. In France, Hugo's literary fame comes first from his poetry but also rests upon his novels and his dramatic achievements. Among many volumes of poetry, Les Contemplations and La Légende des siècles stand particularly high in critical esteem. Outside France, his best-known works are the novels Les Misérables, 1862, and Notre-Dame de Paris, 1831 (known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). Though a committed royalist when he was young, Hugo's views changed as the decades passed; he became a passionate supporter of republicanism, and his work touches upon most of the political and social issues and artistic trends of his time. He was buried in the Panthéon. August 24, 2011 at 6:45 am Great review! You have a fabulous blog! I’m an author and illustrator and I made some awards to give to fellow bloggers whose sites I enjoy. It’s not a pass on award. This is just for you to keep. I want to award you with the Best Books Blog Award for all the hard work you do! Thank you so much for taking the time to read and review all these books for us authors and readers. Go to http://astorybookworld.blogspot.com/p/awards.html and pick up your award. ~Deirdra August 24, 2011 at 7:18 am Wow. I am really impressed that you finished this book. Congratulations! August 27, 2011 at 7:54 am so cool … I think I’ll just skip straight to the political essays/rants. Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *  email subscription

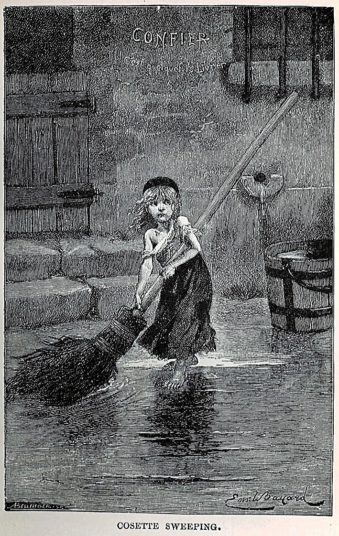

Victor Hugo's Les Misérables: a game with destinyTo begin with the central problem: the exorbitant length. Les Misérables is one of the longest novels in European literature. But length is not just a question of pages, it's also a question of tempo. And this is why Les Misérables is longer than the arithmetic of its length. In his essay "The Curtain", Milan Kundera writes how "aesthetic concepts began to interest me only when I first perceived their existential roots, when I came to understand them as existential concepts . . ." A form is not free-floating; it is not purely a technical exercise, an external imposition. It is intimately, intricately linked to what it describes. "In the art of the novel," Kundera adds, "existential discoveries are inseparable from the transformation of form." And the most obvious transformation Victor Hugo effects in the novel's form is sheer gargantuan size. This megalomania was a conscious choice on Hugo's part. To describe his work in progress, he jotted down a list of hyperbolic adjectives: "Astounding, extraordinary, surprising, superhuman, supernatural, unheard of, savage, sinister, formidable, gigantic, savage, colossal, monstrous, deformed, disturbed, electrifying, lugubrious, funereal, hideous, terrifying, shadowy, mysterious, fantastic, nocturnal, crepuscular." The size was the centre of Hugo's discovery in the art of the novel. And this is visible immediately: it's visible, to the perturbed reader, in the second of this novel's many sentences. The beginning, it turns out, is not a beginning at all. "There is something we might mention that has no bearing whatsoever on the tale we have to tell - not even on the background." Les Misérables begins with a digression from a digression (thus resembling Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary, which a few years earlier had begun with a digression, too.) Here, at the start, Hugo was trying to set up a narrative convention, derived from the novel's deep theory. When the book was finished, Hugo tried - and failed - to write a preface. The preface would have begun like this: "This book has been composed from the inside out. The idea engenders the characters, the characters produce the drama, and this is, in effect, the law of art. By having the ideal, that is God, as the generator instead of the idea, we can see that it fulfils the same function as nature. Destiny and in particular life, time and in particular this century, man and in particular the people, God and in particular the world, this is what I have tried to include in this book; it is a sort of essay on the infinite." The subject of one of the longest novels in European literature is - what else? - the infinite. That is why its tempo is so explicit with slowness, syncopated with digression. But in this novel there is no such thing as a digression. Everything is relevant - since the subject of this book, quite literally, is everything: "This book is a tragedy in which infinity plays the lead," writes Hugo. "Man plays a supporting role." "When the subject is not lost sight of, there is no digression," Hugo wrote later on. But how can the subject of the novel ever be lost sight of, if the lead character is infinity? In that case, nothing will ever be a digression. Yes, the length of this novel is important. Its quantity is its quality. It represents an answer to a central artistic question, which was not an answer the tradition of the novel has ever quite believed in since. This is one reason why Hugo's novel is so strange, and so valuable. "Really, universally, relations stop nowhere," Henry James would write, 40 years later, in his preface to the New York Edition of his early novel Roderick Hudson, "and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so." Life was infinite, argued James, but the novel therefore required a form which gave the illusion of completeness. James, after all, had learned the art of the novel from Flaubert. According to this modernist tradition, the novel was an art of miniaturisation, and indirection. Hugo, however, had come up with a new solution, no less artful than the solution proposed by Flaubert and James. He wanted to create a novel which would try to represent everything by pretending that it did, in fact, represent everything. It would be wilfully ramshackle and inclusive - both on the level of form, and on the level of content: an essayistic novel, or a novelistic essay. "The eye of the drama must be everywhere at once," wrote Hugo. For every plot, seen from the angle of Hugo's style, was infinite. In some ways, the plot of Les Misérables is simple. It is the story of an escaped convict, Jean Valjean, who determines to reform after being saved by the Bishop of Digne; Javert, the policeman who wants to see him rightfully punished according to the law; a dead prostitute, Fantine, and her illegitimate daughter, Cosette, who is entrusted to Valjean's care; an evil inn-keeping couple, the Thénardiers, and their urchin children, Éponine and Gavroche; and Marius, who falls in love with Cosette, and who is the son of a Napoleonic hero who died believing wrongly that he had once been saved on the field of Waterloo by Thénardier, who was in fact a scavenging thief. This might sound tightly plotted, taut with melodrama. It might sound like a good plot for a musical. But no one can read Les Misérables for the cleverness or subtlety of its plot. It is not a novel which prides itself on believability. This might seem surprising - since one natural assumption, perhaps, is that improbability in a novel should diminish with length. In Tolstoy's War and Peace, if people coincide, or marry each other, it still seems probable. Every decision retains its fluidity. And yet in Les Misérables this isn't true. In this gargantuan novel, everything seems utterly improbable. Every plot operates through coincidence. Normally, novelists develop techniques to naturalise and hide this. Hugo, with his technique of massive length, refuses to hide it at all. In fact, he makes sure that the plot's coincidences are exaggerated. It could be argued that the persistent weakness of the plotting is its strength. This, after all, is how coincidence often happens in real life - thinly. But the overwhelming impression is of schlock. And so it might be right to remember that Hugo's original title for his novel was Les Misères, not Les Misérables: which echoed Eugène Sue's recent bestseller, Les Mystères de Paris. Hugo's novel would offer miseries, not mysteries. But it would be part of the same urban pulp tradition. Schlock, however, can make existential discoveries too. One way in which Hugo emphasises the coincidences in his novel is the persistent failures of recognition. This occurs on the level of the characters - where a father does not recognise his son, or a criminal does not recognise the very person he has been pursuing for years. And it occurs on the level of the narration, where the narrator withholds the name of a character throughout an entire episode. Partly, perhaps, this adds to suspense: it creates moments of dramatic irony. But really it's to create a bifocal effect. Hugo wants a plot that is at once about total randomness, and also total predetermination. The novel, therefore, is written from two perspectives. The perspective of mankind, and the perspective of God - or Destiny. "We chip away as best we can at the mysterious block of marble our lives are made of - in vain; the black vein of destiny always reappears." Hugo is echoing Hamlet here: "There's a divinity that shapes our ends, / Rough-hew them how we will . . ." His aim is to stress the weird mixture of freedom and predetermination which is the essence of his novel. Les Misérables is a game with destiny: it dramatises the gap between the imperfections of human judgments, and the perfect patterns of the infinite. The reason for including so much of the world's matter was to work out how mystical the world was. As he put it in Les Misérables: "How do we know the creation of worlds is not determined by the falling of grains of sand? Who, after all, knows the reciprocal ebb and flow of the infinitely big and the infinitely small, the reverberation of causes in the chasms of a being, the avalanches of creation? A cheese mite matters; the small is big, the big is small; everything is in equilibrium within necessity - a frightening vision for the mind." He wanted pattern. But he wanted it only after subjecting the form to its limits, stuffing it with random accreted details - like the man fighting at the barricades, who "had padded his chest with a breastplate of nine sheets of grey packing paper and was armed with a saddler's awl". Meaning could be revealed only by slowing down the tempo of each scene: pausing it in the infinity of its detail. What is relevant? This is the meaning of Hugo's long novel and its slow tempo - heavy with detail. How can you know what fact will emerge, and destroy you? How can you know what will become a trap, and what will not? We live our lives so blissful in our ignorance of an infinity which could invade us at any moment. Hugo's form, predicated on length, on digression and detail, is a deliberate accretion of overlapping examples: his scenes are all variations on the same theme. That is why the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has described how Hugo's main scenes are "irresistible traps" - volcanic craters, where chaos suddenly acquires logic. (And yet, how strenuously do Hugo's characters try to resist the traps of the world!) Whether Hugo is writing about the historical battle of Waterloo or the fictional journey to Arras, his scenes obey the same constraints: a mass of infinite detail, which coalesces to form a trap, an unstoppable destiny. According to Hugo, the battle of Waterloo was determined by the weather. "If it hadn't rained during the night of June 17-18, 1815," writes Hugo, "the future of Europe would have been different. A few drops of water, more or less, brought Napoléon to his knees. So that Waterloo could be the end of Austerlitz, Providence needed only a bit of rain, and a cloud crossing the sky out of season was enough for a whole world to disintegrate." It looks like an essay on Waterloo; just as Valjean's story looks like a story about the tribulations of an escaped convict. In both cases, however, the true subject is chance: "the immense strokes of luck, good or bad, that are calibrated by an infinity that escapes us". Hugo's length does not just represent a philosophy: it is also a politics. In Les Misérables, there is a correlation between the infinite and the unknown; and another correlation between the unknown and the miserable - the destitute. This is why Hugo can move so fluently from a detail to its moral or political halo. Everything is linked by his thematic network. Perhaps it's a pity, therefore, that all that survived of his preface to the novel was a single, dogmatic sentence: "As long as social damnation exists, through laws and customs, artificially creating hell at the heart of civilisation and muddying a destiny that is divine with human calamity; as long as the three problems of the century - man's debasement through the proletariat, woman's demoralisation through hunger, the wasting of the child through darkness - are not resolved; as long as social suffocation is possible in certain areas; in other words, and to take an even broader view, as long as ignorance and misery exist in this world, books like the one you are about to read are, perhaps, not entirely useless." Hugo's epigraph limits his novel too neatly. It's true that the same triad of the needy - which corresponds to Valjean, Fantine and Cosette - is restated by two characters in the novel. But Hugo was not simply a political writer. How could he be? His subject was the infinite. In an abandoned section on prostitution, Hugo wrote: "The portion of fate that depends on man is called 'misère', and it can be abolished. The portion of fate that depends on the unknown is called 'douleur', and this must be considered and explored with trepidation." He was an ontological pessimist, and a historical optimist. This was why Flaubert was unfair to mock Hugo for "the Catholic-socialist dregs . . . the philosophical-evangelist vermin" who admired his novel. Hugo's novel was grander than its politics. It was not so limited. Many years earlier, in his preface to a collection of poetry, Inner Voices, dated June 24 1837, Hugo had said that the poet's duty was to elevate political events to the dignity of historical events. This fluidity between the political and the historical is central to Les Misérables. Hugo wanted to transform politics into history, and rewrite history so that it included the unknown, the ignored, the forgotten - a version of history that would inevitably, therefore, be both an exercise in philosophy and an exercise in politics. Les Misérables, let's remember, was a historical novel on its first publication. But what is a historical novel? With Les Misérables it allowed Hugo to rewrite history: to show how far history is fiction; how far fiction had always been taciturn about the mass of its editing. In his chapter "The Year 1817", a four-page list of minute events, Hugo concludes: "History neglects nearly every one of these little details and cannot do otherwise if it is not to be swamped by the infinite minutiae. And yet, the details, which are wrongly described as little - there are no little facts in the human realm, any more than there are little leaves in the realm of vegetation - are useful." It is this devotion to the infinitely unknown that makes Hugo so meticulous in giving the reader Valjean's prison numbers; and why Valjean's name is almost a tautology. Valjean is everyman: the anonymous, the ignored. That is the secret of his repetitive name (like Nabokov's criminal hero in his novel Despair: Hermann Hermann, a misprint for Mr Man Mr Man). And it is also why Hugo is so careful to set the novel in the suburbs of Paris. It was the communist surrealist Louis Aragon who stated that "with Victor Hugo, Paris stops being the seat of the court to become the city of the people". Hugo was expert at describing the formless suburbs: "that funny, rather ugly semi-rural landscape, with its odd, dual nature, that surrounds certain big cities, notably Paris. To observe the urban outskirts is to observe the amphibian. End of trees, beginning of roofs, end of grass, beginning of pavement, end of furrows, beginning of shops, end of ruts, beginning of passions, end of divine murmuring, beginning of human racket . . ." Hugo's novel restores real life to the truth of its infinite length. Before he describes the barricades of the 1832 revolution, Hugo returns to his theory of history, which is really a theory of detail. "The events we are about to relate belong to that dramatic and living reality that the historian sometimes neglects for want of space and time. But this is where, and we insist on this, this is where life is, the throbbing, the shuddering of humanity. Little details, as I think we may have said, are the foliage, so to speak, of big events and are lost in the remoteness of history." Hugo himself had already provided an example of this foliage - in his description of the battle of Waterloo. He had reinstated an episode which more prudish historians preferred to omit, describing the final desperate resistance of some French soldiers: "They could hear in the crepuscular gloom that cannons were being loaded, wicks were being lit and gleamed like the eyes of tigers in the night, making a circle around their heads, all the shot-firers of the English batteries approached the cannons, and then, deeply moved, holding the moment of reckoning hanging over these men, an English general - Colville according to some, Maitland according to others - cried out to them: 'Brave Frenchmen, give yourselves up!' Cambronne replied: 'Shit!'" This word shit - which Hugo called "the misérable of words" - electrifies the long network of metaphors and themes in the novel. It relates the battle of Waterloo and its themes of chance and destiny to the sewers through which Valjean wanders after he has left the barricades; and it links the sewers to the underground slang, the argot, which Hugo delights to record in his prose. Most prison songs, after all, came from a great long cellar at Châtelet - "eight feet below the level of the Seine". But it also invigorates the moral and political structure of the novel. Les Misérables is based on an ethics which believes in the triumph of the defeated. At the novel's climax, Hugo describes how Marius "began to have an inkling of how incredibly lofty and solemn a figure this Jean Valjean was. An unheard-of virtue appeared to him, supreme and meek, humble in its immensity. The convict was transfigured into Christ." The novel possesses a logic of conversion. It is there in Javert's conversion towards the end of the novel: his sense of "some indefinable sense of justice according to God's rules that was the reverse of justice according to man". And it is there in that miserable word "Shit!". After describing Cambronne's last stand, Hugo describes the meaning of this word "Shit!", as shouted to the English at Waterloo. "To say that," he writes, "to do that, to come up with that - this is to be the victor." It was really Cambronne who won at the battle of Waterloo. That is Hugo's crazy, novelistically persuasive theory: Cambronne, who had made "the last of words the first". The triumph is truly his. In Hugo's list of Parisian gangsters active in the 1830s, there is a stowaway: "Panchaud, alias Printanier, alias Bigrenaille, or Hotwhack, Springlike, Golightly Brujon. (There was a whole dynasty of Brujons; we can't promise not to say more about this later.) "Boulatruelle, the road-mender we have already met. "Laveuve, or the Widow. "Finistère. "Homère Hugu, a black man. "Mardisoir, or Tuesday night." Homère Hugu, a black man! This alias is not the only one Hugo adopts in the novel, which is punctuated by stashed versions of the name Hugo. But Homère Hugu sums up his prose style in Les Misérables: a first-person warped autobiographical voice which improvises a slang version of epic. This voice is the great formal invention of Hugo's novel - the support to the novel's length: a narrator who is unembarrassed by sententiae: sentimental interjections, melodramatic addresses to historical characters, one-word paragraphs, chains of adjectives linked only by their sound, characters who freeze into rants. A narrator devoted to the prolix, the comprehensive. For the world of Les Misérables is one which has been comprehensively transformed into language. It is a new world, with its own conventions. And the gigantism of its plot operates through the range of Hugo's vocabulary. Nothing escapes Hugo's omnivorous collage, not the argot of the criminal underworld, nor songs in dialect, nor the scraps of paper scribbled with revolutionary notes which Hugo loves quoting - incomprehensible fragments, like imported nonsense poems. This novel invents the idea of language as history, as deposit, as waste. It is a huge act of restitution: an exercise in the ignored. Yes, Les Misérables is a microcosmic, metaphoric novel. So that even Baudelaire - the modernist poet, the poet of dense economy - could write in Le Boulevard, on April 20 1862, that it was "a novel constructed like a poem". Its length is a formal property. Its style is saturated in its length. But then again, Baudelaire didn't know the lengths to which Hugo would still go. In April 1862, after all, Baudelaire had only read Part I: Fantine. The rest was still to be published. · Les Misérables by Victor Hugo is published by Vintage Classics this month.

Most viewedThe Terror of KnowingReview | les misérables by victor hugo.  “ Introducing one of the most famous characters in literature, Jean Valjean–the noble peasant imprisoned for stealing a loaf of bread–Les Misérables ranks among the greatest novels of all time. In it, Victor Hugo takes readers deep into the Parisian underworld, immerses them in a battle between good and evil, and carries them to the barricades during the uprising of 1832 with a breathtaking realism that is unsurpassed in modern prose. Within his dramatic story are themes that capture the intellect and the emotions: crime and punishment, the relentless persecution of Valjean by Inspector Javert, the desperation of the prostitute Fantine, the amorality of the rogue Thénardier, and the universal desire to escape the prisons of our own minds. Les Misérables gave Victor Hugo a canvas upon which he portrayed his criticism of the French political and judicial systems, but the portrait that resulted is larger than life, epic in scope–an extravagant spectacle that dazzles the senses even as it touches the heart. “ ( Synopsis source ) Les Misérables is a book with whom I have a history. My undergraduate dissertation is based, in large part, on this novel and its adaptations, and I’ve been to see the musical itself many times – it’s probably my favourite musical, all things considered. I’m more than familiar with its soaring themes of justice, redemption, faith, atonement etc. and its characters (I was a big observer of the barricade boys fandom on Tumblr and on fanfiction sites). Despite all this, I’d never fully read the novel, cover to cover; anyone who has ever done a dissertation on a book will tell you that selective skimming of it is sufficient so long as you close-read specific, well-chosen sections that advance your overarching argument. But I always felt a little bit of a fraud as I could never bring myself to legitimately say I had read the novel – I ran the Misérables May readalong to correct this. “Teach the ignorant as much as you can; society is culpable in not providing a free education for all and it must answer for the night which it produces. If the soul is left in darkness sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but he who causes the darkness.” Victor Hugo’s novel is a huge sweeping tale based around its central character, Jean Valjean. A former convict, Valjean was imprisoned for stealing a loaf of bread to try to save his family from starvation and, as he kept trying to escape, his sentence became longer and longer when he was caught. When we start the novel he has been released on parole but this means he has a proverbial black mark against his name and he isn’t exactly welcomed in many of the rural towns of France that he wanders through. He finds work but isn’t paid fairly, inns turn him away because he’s a former convict, and it seems as though he has hit rock bottom even though he has done his time and ‘paid’ from his crime. Enter the Bishop, a too-good-for-this-world character, who, after Valjean steals his silver from him, willingly gives him a pair of silver candlesticks, and with them ‘buys his soul for God’. This starts off many a philosophical and moral dilemma for Valjean who didn’t have faith and didn’t feel like the world was on his side – with the Bishop forgiving him for his crime and telling him God would still have his soul, Valjean starts a journey of redemption. “Love is the foolishness of men, and the wisdom of God.” Of course, the story is much more complex – we have tenacious police officer, Javert, as Valjean’s antagonist; we have Fantine, a poor young girl blinded by love and left as a single mother trying to provide for her daughter before dying; we have the Thenardiers who exploit Fantine’s desperation and adopt her daughter, Cosette, to a loveless life of servitude; we have Marius, grandson of a royalist who ends up having rebellious republican feelings; we have Gavroche, a young urchin child in Paris that stands for all orphaned children on the streets at the time; and we have a group of enterprising Parisian revolutionaries hoping to incite rebellion in the now-little-known June Rebellion of 1832 . Regardless of what else you think of Victor Hugo’s novel, the mastery of weaving together so many threads of story and sustaining them for 1000+ pages is undeniable. “There is always more misery among the lower classes than there is humanity in the higher.” Often commented on when it comes to Les Misérables is its length – the edition I read stood at some 1400 pages and it’s not lightly that its fans call it The Brick. As you might expect through such an expansive novel with a huge cast of characters, certain moments of the story are more gripping than others – for example, I found the sections where the Thenardier family disguise themselves as the Jondrettes and con people out of money particularly fun and engrossing, the section in the Parisian sewer system less so. What I’ve always found intriguing about the musical of Les Misérables is how different themes and characters interest different people – I most enjoy the sections on the barricade with the revolutionary group Les amis de l’ABC, whereas a friend of mine loves the clash between Valjean and Javert the most. The novel is no different. Well, except in one way – Victor Hugo is known for his digressions, digressions which test the very notion of the word by lasting for 50 pages at a time. These digressions serve to enrich the context of the novel’s story – the aforementioned journey into the sewer system is one such digression, another on the subject of Waterloo happens. However, none of these digressions are crucial to the advancement of the plot and I think this is why they, and the novel as a whole, can be hard to get through. Similarly, there are sections of the novel which read like treatises or polemics on particular social or political issues of the time – they aren’t strictly necessary for the sake of following the story, but they do enrich the understanding of the context around the characters which has produced the circumstances in which the story can happen. It still doesn’t make 50+ pages about literal shit any easier to stomach, though. “To love or have loved, that is enough. Ask nothing further. There is no other pearl to be found in the dark folds of life. “ In conclusion, Les Misérables is a sweeping, expansive 19th-century novel that explores French history and politics, moral philosophical issues, topography and architecture of Paris, and antimonarchist sentiments, alongside universal themes of justice, faith, and love. To try to summarise or review it is a nearly impossible task. For all its high and lofty themes, it’s also a compelling story of complex characters with moments of light and shade which is probably more so why it has endured the centuries and become thought of as one of the greatest stories of all-time. “So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation which, in the midst of civilization, artificially creates a hell on earth, and complicates with human fatality a destiny that is divine; so long as the three problems of the century – the degradation of man by the exploitation of his labour, the ruin of women by starvation and the atrophy of childhood by physical and spiritual night are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words and from a still broader point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, there should be a need for books such as this.” Goodreads | Twitter | Instagram Share this:3 responses to “review | les misérables by victor hugo”. […] has a pattern of raising awareness of the awful state of poverty. Victor Hugo’s infamous Les Miserables is about revolution in France and the struggles of an entire cast of characters from varying […] I’m not sure if I’ll be adding this to my TBR anytime soon but well done for reading this all the way through! I can’t imagine how frustrating the digressions would be to read through, but it sounds like you appreciate why Hugo might have put them there. Like Liked by 1 person I’m ashamed to say I’m French and have never read this… I loved your review 😊 Leave a comment Cancel replyThis site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

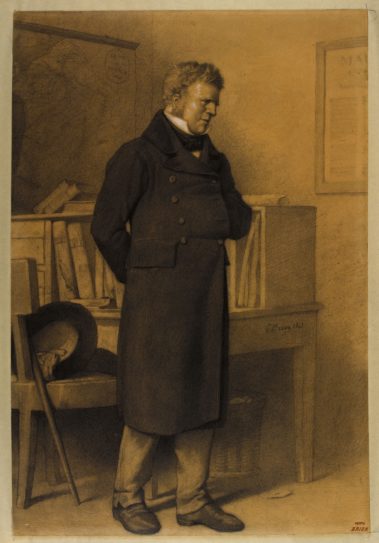

Les Misérables Mercy Vs Law, Society Vs HumanityAuthor: Victor Hugo Les Miserables has long been a staple of our shared narrative – an epic story of heroism and villainy and all the shades of desperation and hopelessness that lie in between. Spawning numerous plays and movies, as well as countless adaptations and abridgements, Hugo’s story survives not because of its perfection but because of its uncompromising power. I first encountered Les Miserables as a child right on the cusp of adulthood, although I was ultimately more inclined to childish things than the new world opening up to me. I saw Hugo’s story represented in a movie, which stayed mostly true to the overarching story; fifteen odd years later, I still remember the closing scene, the gut wrenching desire to cry, and the commentary on a “justice system” turned intolerably cruel. I’ve been promising myself to read the book ever since, but its sheer volume (1,000+ pages) and my first experience with Hugo (the slog through the digression that is known as Hunchback of Notre Dame , which is entirely more about the architecture of Notre Dame than the fate of the hunchback) kept me from approaching the task until now. Ultimately, I’m glad that I took this long journey. It was an unforgettable foray into the depths of humanity at both its most angelic and most depraved. Hugo, however, remains a difficult author, not so much for his writing style (it’s languid and beautiful) but for his affinity to add non-fictional essays wherever possible, stilting what is a dynamic plot. But more on that later.  Jean Valjean, as the Mayor, by Gustave Brion For those not in the know, Les Miserables follows the life of a man, Jean Valjean. Caught as a young man, stealing a loaf of bread to keep his sister and her needy children alive, Valjean was sentenced to 19 years of imprisonment and hard labor. As his body grew more stolid and strong, his soul collapsed within him. He emerges, having paid his supposed debt to society, but even still that is not enough. His sister and her children are gone, presumably long dead or else captured into prostitution, and Valjean, with his tell-tale convict papers, is not wanted anywhere in society. The bitterness is extreme and heartfelt and sets him on a dark path that is intercepted by a kindly Bishop who through one true act of kindness and forgiveness alters everything for Valjean and allows him to start over. But, secrets will out and Javert, the ineffable police inspector, is determined to capture the convict again. As Valjean makes his journey through society, now hidden behind a secret name, success is offset by compassion. But nothing is so clear-cut in Hugo’s world, and the “justice” system is far from done. Javert is not the only antagonist, and soon circumstances put Valjean in a difficult position. Meanwhile, Fatine, a young woman destroyed by the love of a man, is left pregnant, unmarried, and desperate. As she slowly works her way down in society, desperate to do anything to take care of her child, Cosette, destiny is set in motion. As Fatine sells first her hair, then her teeth, and finally her body, her path intersects with Valjean, and what’s right and what’s wrong takes them all far outside of the law and its steadfast interpretation by Javert. As Les Miserables continues, other characters come and go. Dregs from the bottom of society, criminals, orphaned street children, policemen, and a wealthy young man consumed by monarchism and an ancient debt that will soon get him entangled in the mess of all the miserable people around him. It culminates in the June rebellion of 1832 where history and fate interweave, love and romance meet despair and war, idealism and reality clash, and the meaning of duty leads to shattering decisions. Les Miserables ranges over a lifetime with Valjean starting as one type of person and then working his way through an incredible character arc, which pits his own delusion of his criminality against the necessity to thwart the law and protect the neglected and the brutalized. Valjean’s encounter with Fatine and her dying wish that he protect her daughter, held by a ruthless foster family, forces Valjean to take a strange path and find his own form of justice, his own definition of what’s right against what is legal. This is where the crux of the novel lies and where Hugo shines his brightest. The law is dogmatic whereas love and God are not. Human law is pitiless, but God’s law sees room for forgiveness and understanding. One thwarts and plays against the other, and simple interpretations are thrown aside as we submerge ourselves into the underworld of Paris and watch good intentions lead to criminal actions, lead to desperation, which then leads ultimately towards violence and a weird sort of connection. The world of the street is a dark place, but by our complacence have we not made it so? Have we not determined that once fallen escape and retribution are impossible? The story lives up to its title. It’s a tear jerker and while some characters elicit more sympathy than others (I was so mad at Cosette and Marius by the end) Jean Valjean ties us emotionally to the narrative, even through Hugo’s sermonizing about everything ranging from the ultimate historical meaning of Waterloo to the creation of Paris sewers and a surprisingly long narrative on human waste and its existential meaning. If you can read through this tale and not cry – not feel for Jean Valjean as though he is a close and much abused friend – then you ultimately have no soul and no love for humanity. Hugo is a master at character and a master at revealing injustice in all its fetid ugliness.  A drawing of Cosette by Emilie Bayard, which appeared in the original edition of Les Misérables What he is not a master of, however, is pacing. While the story is itself is sheer perfection, the delivery hurts the narrative and its forceful point. Hugo likes to ramble. A LOT. Because of this, I often found myself picking up the book, not for the joy of reading or the revelation of Hugo’s complex morality, but out of duty. This is a pure Hugo issue, and he is the only author to ever make me feel kindly towards abridging. Every time the narrative starts to build power and the theme force, Hugo stops and goes on (sometimes for hundreds of pages) about things that simply don’t matter to the story. This devalues everything he is working toward. As Valjean finds himself transforming into a father for Cosette and finally finding love among people, everything stops for pages and pages as we deep-dive on monasticism, specifically its merits and cultural implications as opposed to its unnecessary strictures and flaws. An interesting topic, sure, but does it belong here? The answer, as always, is no. Hugo likes to set his stage with history, and I am surprised that he doesn’t just go back to the beginning of time. Any mention of a road, a building, a personage, leads to a back-in-time extravaganza with much eulogizing of everything from military tactics to the virtues and vices of Napoleon (long dead by the time this story starts, I might add.) It’s enervating and saps the joy of reading out of a narrative that is, in and of itself, unforgettable and unsurpassed. Just why, Hugo, why? In the end, despite Hugo’s rants (oh, there are so, so many and they are soooo long) Les Miserables is so amazing that it’s worth the trouble, even (if you can stand it) the non-abridged version. Ignore the asides and keep your eyes on Valjean, on Javert, on Cosette, and allow your heart and connection to prevail during the dry moments. Valjean is an unforgettable character. He will leave you in tears, but ultimately his story will change your life and perception, will make you kinder and more empathetic, will make you look at the why behind people’s circumstances instead of relying on knee-jerk judgment, and will make you accept (and hope to change) your complicity in the entire mess of society and despair. – Frances Carden Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews [AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1977076602″]

Book Review: Les Misérables Jean Valjean has been in prison for 19 years. On the day he is freed, he walks to the city of Digne, which is over thirty miles away. Exhausted, he searches for food and shelter, but is rejected at each place he goes to because he was a former convict. Finally he is told to ask the Bishop of Digne for help. The Bishop agrees without hesitation. Valjean wakes up early in the morning and steals the Bishop's silverware. He is caught and brought back to the Bishop, but the Bishop saves Valjean from returning to prison by pretending that the silverware was actually a gift. He even gives Valjean silver candlesticks as well. The Bishop convinces Valjean to turn around his life. Exceptionally strong character development was a highlight for me. Some themes in this classic are sacrifice for others and unexpected generosity; for example, Valjean has an opportunity to shoot his worst enemy, but instead decides to free him. The plot also weaves the connections between characters magnificently. This book has made me experience emotions more strongly than any other book I've read. Les Miserables is a relatively long novel; Victor Hugo (the author) is willing to become verbose frequently. I actually enjoyed its details, which made me more immersed in the story. If you don't usually read books with philosophy, it may take a little getting used to. Even if you have already watched the play, the book is still worth considering; there is plenty of extra material in the book that the play skips. Les MisérablesBy victor hugo. 'Les Misérables' is a story of how everyday people can build a more just society through small acts of courage and hope despite difficult circumstances and the past.  Article written by Emma Baldwin B.A. in English, B.F.A. in Fine Art, and B.A. in Art Histories from East Carolina University. The novel is quite long, detailing the lives of various characters in France, many of whom play secondary roles. Primarily though, it follows the lives and struggles of Valjean, Cosette, Eponine, Fantine, and Marius as they deal with the politics of 19th-century France and their individual hopes and dreams. Spoiler-Free Summary‘ Les Misérables ‘ is an epic tale of courage and perseverance set in early 19th-century France. The story follows Jean Valjean, a prisoner recently released from prison after serving almost 20 years for stealing a small amount of bread. Valjean’s determination to lead a life of moral rectitude and become a model of justice is soon tested as the relentless pursuit of Javert, a ruthless police inspector, follows him through France. During his travels, Valjean meets Fantine, a struggling factory worker, and a single mother desperate to provide for her daughter Cosette. Valjean helps Fantine as much as he can before she tragically dies. Valjean, Cosette, and a young man named Marius Pontmercy all soon find themselves in the midst of the Paris Uprising of 1832, an uprising driven by passionate citizens eager to throw off oppression. The complex tale explores themes of mercy and justice , forgiveness, sacrifice, and morality. Valjean’s lifelong struggle to uphold the law while avoiding the persecution of Javert serves as the spine of the story. Plot Summary of Les MisérablesSpoiler alert: important details of the novel are revealed below. In the first chapters of ‘ Les Misérables ,’ the reader is introduced to Jean Valjean, a prisoner who recently finished a 19-year sentence for stealing bread. He stays at the home of Bishop Myriel, hoping to start his life off on a new foot. But, out of desperation and poverty, Valjean steals the bishop’s silverware. Kindly, Myriel gifts Valjean the silver when he’s rearrested by police. Years pass, and Valjean becomes the mayor of a small town, Montreuil-sur-mer. Readers are also introduced to Fantine, a young woman who falls in love and gets pregnant. Her lover, Tholomyès, leaves her alone to contend with her pregnancy, birth, and later poverty. She knows that no one will hire her if they know she’s had a child out of wedlock, so she gives her baby, Cosette, to the Thénardiers to take care of. Fantine is later fired from her job after her coworkers find out about her child, and she has to start working as a prostitute. She’s about to be arrested when Valjean intervenes and sits at Fantine’s bedside while she dies. At the same time, the police inspector Javert catches up with him and arrests him. Valjean soon escapes from prison and travels to Montfermeil in order to keep his promise to Fantine and find Cosette. The Thénardiers are revealed to be an incredibly cruel family who has done nothing to give Cosette a happy life. They have two daughters, one of whom, Eponine, plays an important role in the novel. Valjean takes Cosette to Paris, and Javert finds them, forcing them to flee. They spend time living in a convent afterward while Cosette goes to school. Readers then learn about Marius Pontmercy, a young man from a wealthy family. Marius decides to live a poor life as a law student and joins the Friends of the ABC, a revolutionary group led by Enjolras. When Marius sees Cosette in a park, he falls in love with her immediately. Eponiine, who’s been living nearby with her parents under assumed names, falls in love with Marius. But he’s still entirely dedicated to Cosette and her to him. Valjean disapproves and disappears with her, breaking Marius’ heart. Marius and his friends start a political uprising and attempt to fight for democracy behind a series of barricades. Javert has disguised himself among the troops, and they discover him. Eponine then sacrifices her life to save Marius’ and dies in his arms. Valjean, realizing that he’s wronged his daughter, decides to find Marius and ensure that nothing happens to him. He volunteers to execute Javert but decides to let him go. Valjean tries to flee with a very injured and unconscious Marius through the sewers, but Javert finds them and is torn between his duty and what he knows is right. He throws himself into the river, committing suicide, after letting Valjean go. Marius recovers from his injuries, and he and Cosette get married. Marius learns about Valjean’s past and tells Cosette, worried that he’s a bad influence on his new wife. Valjean, depressed and lonely, is near death. The novel ends with a reconciliation, and Valjean is able to die happily with his family around him after Marius learns that Valjean is the one who saved him. What kind of novel is Les Misérables ?‘ Les Misérables ‘ is an epic historical novel written by Victor Hugo . It tells the story of redemption and the human condition in 19th-century France, with characters ranging from criminals to saints . It has been adapted numerous times for the stage and screen, showcasing its enduring power. What are Victor Hugo’s books known for?Victor Hugo is renowned for his richly descriptive stories , such as ‘ Les Misérables ‘ and ‘ The Hunchback of Notre Dame .’ His books are known for their unforgettable characters, captivating plot lines, and inspiring themes. What is the style of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables ?Victor Hugo’s ‘ Les Misérables ‘ is a classic novel in the style of historical fiction, romanticism, and social commentary. He brilliantly uses the settings of nineteenth-century France to illustrate how the revolutionary and Napoleonic periods changed people’s lives . Why is Les Misérables important?‘ Les Misérables ‘ is an important story of the power of hope and the enduring strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity. Its message of justice and redemption transcends time, showing us the power of grace, compassion, and second chances. Join Our Community for Free! Exclusive to Members Create Your Personal Profile Engage in Forums Join or Create GroupsSave your favorites, beta access.  About Emma BaldwinEmma Baldwin, a graduate of East Carolina University, has a deep-rooted passion for literature. She serves as a key contributor to the Book Analysis team with years of experience. About the Book Discover literature, enjoy exclusive perks, and connect with others just like yourself! Start the Conversation. Join the Chat. There was a problem reporting this post. Block Member?Please confirm you want to block this member. You will no longer be able to:

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete. Stray ThoughtsA home for the stray thoughts of an ordinary christian woman.  Book Review: Les MiserablesYes, I finally finished it! All 1,400+ pages! I’ve read a couple of different abridged versions of Les Miserables by Victor Hugo and made it my goal to read the unabridged version.  When he traveled into a new town, his help in saving someone’s life and the confusion and excitement around the event resulted in the town officials’ forgetting to ask him for his papers. He was hired on in a factory and devised a way to improve the factory’s production, leading to his promotion, eventually to the head of the factory, and further still to his being elected the mayor. He was known as a quiet but kind and and benevolent man, using much of his wealth to aid those in need. Thus it would seem his life was set on a new course of usefulness and happiness, except…except… Except for Javert, a former prison guard who became the new police inspector in Valjean’s town, who thinks he recognizes the mayor as an ex-convict who has broken his parole. Intersecting Valjean’s story is that of Fantine, a young, naive girl who gave herself to a man who only wanted to use her as a diversion one summer, leaving her with child, Cosette. In that day a single woman with a child was a scandal, so Fantine found an innkeeper and his wife whom she paid to keep her child while she went to another town to look for work. She ended up in Valjean’s factory, where she was fired after it was discovered that she had a child. In the meantime, the innkeeper, Thenardier, made up stories about Cosette needing more clothes, needing medicine, becoming very ill, all in an effort to extort money from Fantine. Fantine, worried and desperate, sold her teeth, her hair, and eventually her body (which is handled discreetly, without explicitness, in the book and was viewed by Hugo as a form of slavery). She became gravely ill from neglect of her own care, and an altercation in the street brought her to the attention of Valjean. When he heard her story, he felt responsible for her situation since she was dismissed from his factory, and he paid her her care and promised to take care of her daughter. The Thenardiers resented Valjean’s rescue of Cosette and the subsequent loss of income. The rest of the book details the pursuit of Valjean by Javert, and, at times, Thenardier, his care of Cosette, her growth into a young woman, her falling in love with Marius, much to the dismay of Valjean, who has never loved anyone else and is afraid of losing Cossette. That is the basic plot, but there are so many more layers, subplots, and characters in Les Miserables . There are discussions of poverty, politics, French history. One of the major themes is the righteousness of the law, as represented by Javert, versus the righteousness of grace, represented by Valjean. While not a Christian book in itself (it portrays the innate goodness of man, whereas Scripture portrays the innate sinfulness of man , and it includes some strange philosophies, and its politics are much more socialistic than I am comfortable with), it does portray Christian themes of redemption, forgiveness, sacrifice, and selflessness, and Valjean does depend on God for salvation and strength. I have mentioned here before that I had read a couple of different abridged versions and had wanted to read this unbridged version for a long time. Though normally I am a book purist, wanting a book to remain as untouched as possible, I can see now why this book is abridged. The sheer 1,463 page length of the book is not so much the problem as the frequent asides. It is rather like rush hour traffic in some places — very slow going interspersed by brief interludes of acceleration. It’s like a mini-series interrupted at the climactic moments by a documentary. Valjean’s escape with Cosette to a convent leads to a discussion of the history of convents in general, this convent in particular, whether convents are right or wrong. An incident at the end of the battle of Waterloo which has repercussions for two characters later in the book is preceded by a 57-page description and discussion of Waterloo. A student revolt at the barricades leads to a discussion of the differences between an insurrection and a riot and which, in the author’s opinion, is right and wrong. Valjean’s escape from the barricades with a wounded Marius through the sewers involves a detailed description of the history of sewers and the author’s suggestions for how they could be made better (and I never knew there were so many different synonyms for sewage). Hugo must have been an intensely curious man as well as a thinker and a philosopher, but the asides do get tiresome. Though at times I found myself interested in them in spite of myself, particularly the battle of Waterloo section, a few times I was tempted to skip through them, reminding myself that I wanted to read the unabridged version, not skim through it. And I am glad that I read it. It did give me a fuller understanding of the story, and I particularly enjoyed learning more of Fantine’s early story than other versions included and more of Javert’s mental struggle that led to his actions at the end of his life. There are moments of sheer beauty in the book, moments of identification with the very human struggle, such as Valjean’s dilemma when he learns another man has been arrested under his name. One of the most poignant moments iss when he returns home after Cossette’s wedding and pulls out the little clothes he had bought for her when he first rescued her, and weeps into them. One of my favorite sections is when Thenardier seeks to implicate Valjean to Marius, unwittingly clearing his name instead. And for all of Hugo’s wordiness, there are moments of clever, succinct, descriptive phrasing: “For dowry, she had gold and pearls; but the gold was on her head and the pearls were in her mouth.” “A torn conscience leads to an unraveled life.” “There is a way of falling into error while on the road of truth. He had a sort of willful implicit faith that swallowed everything whole.” “Skepticism, that dry rot of the intellect.” “He suffered the strange pangs of a conscience suddenly operated on for a cataract’.” “This man…was…still bleeding from the lacerations of his destiny.” Just a word about the musical based on the novel: it was through the musical that I first discovered this story. I was in the library video section one day, saw a video of the tenth anniversary production of the musical, and decided I’d check it out just to see what it was all about, having heard the title for years but knowing little of the story. I was absolutely enthralled. The music is gorgeous and the story so touching. But for the information of those whose standards are as conservative as mine or more so, there is a smattering of four-letter words, and the section dealing with Fantine’s prostitution is much more explicit than the book is. Unfortunately, though I’d love to see a stage production, I could not in good conscience because of that section. As it is we skip the “Lovely Ladies” song on the video and CD. I was delighted to discover, though, that the musical does go back to the original for many things, using even some exact lines from the book. It’s fairly faithful to the book except for the section mentioned, and the fact that Eponine and Marius’s relationship is not as it was in the book, and the scene of Valjean praying over Marius before the battle of the barricade and regarding him as a son was not on the book: at that point, even after rescuing Marius, Valjean hates him for the threat he is to taking Cosette away and is only caring for him for her happiness, though he does come to love him as a son much later. Plus Valjean doesn’t fight Javert after Fantine’s death before rescuing Cosette: he is arrested and escapes again later. I’ll leave you with a couple of scenes from the musical. The first is the confrontation between Valjean and J avert after Fantine dies. The second takes place after Valjean learns another man has been arrested in his name, and he struggles within himself as to what to do about it. The number 24601, which is mentioned in both songs, was Valjean’s number in prison. (This review is linked to Semicolon’s Saturday Review of Books , Callapidder Day’s Spring Reading Thing 2009 Book Reviews , and 5 Minutes For Books Classic Bookclub Discussion of Les Miserables .) Share this:48 thoughts on “ book review: les miserables ”. CONGRATULATIONS on getting through that! I saw the musical first and then read the book. I’ve forgotten most of the musical now and am curious to see it again but, as you say, the issue of prostitution is more heavily emphasized. One day I would like to go back and re-read the entire book. However, that’ll have to wait a little while! I tried to read this years ago and just could not. Maybe I was too young and should try again. You made it sound interesting. Thanks for the review, Barbara. Your description makes me lean toward not reading the unabridged version–I’m not sure I could get through the history of convents section or the 57-pages on the background of Waterloo. The story itself, however, sounds very good. I’ve always wanted to see the musical. I’m just like Quilly! I tried to read it I think in high school – and it just wasn’t happening. I never picked it up again – and I’ve never seen the musical either. I should probably revisit this whole thing! Sounds like a great story! Woo Hoo. You are the definition of stick-to-tiveness! Wow, Barbara. Talk about perseverance – you certainly have it. My hats off to you! Thanks for the summary of the book. I have always heard of the book, but didn’t know what it’s really all about. Good on you for finishing!!!! WOW! Great review. Congrats on rising to the challenge. I read this in high school, but I’m not sure whether it was the full text or an abridgement. Probably it was an abridgement. My youth pastor was always recommending books, and he recommended this one with great enthusiasm. I picked up a used copy of ‘War and Peace’ and was going to read it, but then I discovered it was abridged. I know what you mean about being a purist, yet seeing why, sometimes, these monumental works are abridged. Sometimes I wonder if the author himself might pare it down if he had opportunity to revise it today! You certainly have preservered. I know you’re happy its finished. Pingback: Friday’s Fave Five « Stray Thoughts Good review on a great book. I read it when I didn’t know there were abridged versions available! But, like you, I’m glad I made it through. Such a good book, and a great musical opera. Like you, I love both. I even enjoyed some of the essays and asides; others I skimmed. GREAT review, Barbara! Thanks for the videos too. I would love to get into this once I finish Dostoyevsky’s CRIME AND PUNISHMENT. LES MISERABLES is too good to be missed. Pingback: Saturday Review of Books: April 11, 2009 at Semicolon Pingback: What’s On Your Nightstand: April « Stray Thoughts Does anyone know what 24601 means? besides it was Jean ValJeans number? does it represent something? I don’t think it represents anything, Emily. Thank you for your review on Les Mis. I’ve never seen it and I can’t remember reading it in h.s. so when my two girls (14, 15) wanted to audition for the summer theater school edition of Les Mis I didn’t hesitate to say yes (it’s a classic after all). Then a friend mentioned the prostitution aspect so I asked the summer theater director how the school edition handles this and she said, “it’s still there … language and all.” She said she’d cast the older girls or girls who didn’t have a problem with it, but wasn’t sure how she’d do the choreography and costumes. So we are going to find something else to do this summer. Needless to say we are all very disappointed. Pingback: Spring Reading Thing 2009 Wrap-Up « Stray Thoughts Congrats on making it through. The 57-page description of Waterloo was my Waterloo for this book. I just couldn’t make it past that! Good for you for persevering! Great review! I loved the book and have seen the play several times. I also have the music :>) Happy BTT! Wow! That is a BIG accomplishment (pun intended 🙂 And, a great review! Here’s my BTT. I love listening to the musical – my best friend in high school did his term paper on this and I remember it was huge. I now want to read it because I adore the overall story and would love to see more detail to it. Les Miserables is one of my favourite books ever. Not always easy to get through, and my hardback copy weighed a ton even though it only ran to 900 pages, but definitely worth the effort. I adore the show, too, but there’s so much more to the book that just can’t be squeezed into a couple of hours. I enjoyed reading your review! Les Miz is the very best book ever that I’ve read in my entire life (although I’ve lived only 15 years). I’ve first read it when I was 12, and then it led me to many different abridged versions of Les Miz. I’ve seen Les Miz musical in London and Tokyo, but I’ve been longing to see it in Broadway. Now I know I can’t reach my dream, though. It’s a great pleasure to share the great impression of Les Miz with others:) Pingback: Meme of Reading Questions « Stray Thoughts This was review was very interesting to read. I ama sophomore in high school and decided to read this for an English project. Overall it was an incredible novel but I couldn’t agree with you more about how there were some parts of the story that were difficult to get through. I remember trying to read the section on Waterloo and often found myself drifting off. Thanks so much for linking me up to your review, Barbara. I hope I have enough perseverance to finish this one day! I’m about to start reading the unabridged version of this book. Thanks so much for the review! You’re very welcome! I hope you enjoy it! I enjoyed reading your review!. Thanks so much for the review! I’ve become obsessed with reading this book. Your review did it extreme justice. Thanks for keeping such a great blog 🙂 Pingback: Book Review: Chasing Mona Lisa « Stray Thoughts Pingback: Together on Tuesdays: Favorites Books and Films « Stray Thoughts Les Miserables is possibly the most remarkable work of fiction I have ever read. I have read it multiple times, including the full text and many different abridgments. I admit that despite it being my favorite book, I do not enjoy reading the entire original text each time. I am not a French scholar, a war historian, nor do I have any particular fascination with the French Revolution or Napoleon. But I love this story. The first time I read an abridged version, I was shocked to see that Fantine was almost an afterthought; she was barely mentioned in the book. There were many glaring differences that I thought destroyed many of the characters, and thus the true power of this book. I have also read longer abridgments which include all the necessary portions, but still find it necessary to include vast descriptions of the sewers of Paris, and the Battle of Waterloo. I finally decided to abridge the book myself. I only omitted those parts I found to be completely superfluous, unrelated to the narrative, or distracting from the flow of the story. The original text contains over 540,000 words. My abridgment contains less than half that at under 254,000. Here is the link: http://lesmiserablesabridged.blogspot.com/2012/12/les-miserables-abridged-part-1-fantine.html ITS A GOOD IN FINISHING ‘FATASTIC My son and I went to see the movie on Christmas day since hubby was working and daughter had gone out of town with cousins. I will probably do a review on my blog soon of both the positives and negatives of it. I don’t go to many movies, but this was an experience. The work itself is fantastic. I had heard of it, of course, but was not familiar with the plot. I’d love to hear about the movie. We’ve been wanting to go but wary about how the scenes with Fantine were handled. The musical plays up aspects of that that the book does not. Hugo was realistic but discreet. Pingback: A bloggy look back at 2012 « Stray Thoughts Pingback: What did you read as a kid? « Stray Thoughts Pingback: Bookish fun | Stray Thoughts Pingback: A-Z Bookish Questionnaire | Stray Thoughts Nice review! You’re right – the real thing is always better than versions and abridgements. I haven’t read any Hugo (’93 is on my “to read” pile for next year). (I followed the link in your comment on lisanotes) Pingback: Bookish Questions | Stray Thoughts Pingback: Book Review: June Bug | Stray Thoughts Pingback: Laudable Linkage | Stray Thoughts Pingback: Books I’d Like to Reread | Stray Thoughts Pingback: Literary vs. Biblical Redemption | Stray Thoughts Comments are closed.

Notice: All forms on this website are temporarily down for maintenance. You will not be able to complete a form to request information or a resource. We apologize for any inconvenience and will reactivate the forms as soon as possible.Book ReviewLes misérables.

Readability Age Range