Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

A Positive Approach to Academic Integrity

In 2017, 83 Ohio State students were reported for using an app called GroupMe to share quiz questions and answers (Bever, 2017). At universities across the nation, students have cheated using various apps and technology. Increased access to technology tools does provide additional avenues for cheating, but the availability of these new tools has not led to more cheating (see Lang, 2013).

Still, preventing academic misconduct is a topic that weighs on many instructors’ minds. We want students to learn and to come by their degrees honestly. The good news is that the educator’s role in academic honesty does not always have to be punitive or after-the-fact. Proactively promoting academic integrity in positive ways can reduce the likelihood that students will commit misconduct.

In the United States, public attitudes about academic misconduct range from mild irritation at the existence of cheating to the moral outrage one might show toward hard criminal offenses. In an effort to reduce cheating, instructors often implement defensive measures. For example, using a digital plagiarism detector such as Turnitin is meant to deter students from plagiarizing in their writing and to catch the ones who do so. Setting time limits for synchronous online exams is a common tactic for reducing the time available for students to use the textbook or a website like Chegg to solve their problems for them.

But telling students not to cheat—and what will happen to them if they do—only goes so far in deterring academic misconduct.

Underneath those dos and don’ts are implicit values present in the American system of higher education. What if we openly communicated those values instead?

What do we value?

The concept of academic integrity is often taught with a focus on academic misconduct and how not to misbehave. Students navigate through college trying not to break the rules. Underneath those rules lie traits that are valued in our education system, and in scholarly work. For example, we trust that a student who can explain a concept in their own words rather than quoting a text has truly learned that concept. We also value original thought and the individual voice in scholarly conversation. We place importance on respecting what writers and researchers contribute to the conversation, and on distinguishing who said what.

For a brief history on the development of intellectual property, see Bloch, 2012, Chapter 2.

Do students understand what academic integrity is?

Bretag and colleagues (2014) discuss two main types of research into academic integrity: student self-reports about their cheating behaviors and research on students’ understanding of academic integrity. Based on surveys of students at multiple institutions, they found that students had some idea of what academic integrity is but did not feel they received enough support for how to practice it effectively, beyond the generic information provided early in their college careers. In one of the surveys, students indicated that instructors’ expectations varied and that conventions were not uniform across courses, and that knowing what happens when you commit academic misconduct is not helpful.

Learning disciplinary practices

Nelms (2015) points out that many students plagiarize unintentionally on their way to becoming more expert in their fields. As novice students learn to use the language of their disciplines, they may begin by imitating the language that they are reading. He provides a positive view of plagiarism as an opportunity to help students develop their own voices and learn to participate in scholarly conversation. By viewing students first as learners, it is possible to create penalties that are educational rather than punitive (Morris, 2016).

English language learners

It’s especially critical to support English language learners writing in a non-native language to understand academic integrity expectations. Rhetorical styles and conventions vary around the world. Students who were not educated in the United States may have learned practices surrounding academic integrity that do not align with the Western conventions of incorporating and citing scholarly work, and therefore face a steeper learning curve.

Explore resources for supporting international students with writing from Writing Across the Curriculum.

The learning environment

In Cheating Lessons (2013), James Lang examines how features of a learning environment might lead to increased academic misconduct. He argues that instructors can influence these features directly. They are (p. 35):

Emphasis on performance : Students who are more concerned with doing well on a test than with learning are more likely to cheat on that test. If an instructor overemphasizes grades, the focus on performance can put pressure on students and become a dominant feature of the learning environment.

High stakes : If a student’s grade is determined by one or two assessments, such as a midterm (at 50% of the grade) and a final (the other 50% of the grade), cheating is more likely. In such a class, students are not receiving regular feedback on their work, and only have two chances to demonstrate their learning.

Extrinsic motivation for success : Many students are motivated by grades or other extrinsic motivators, such as pressure from parents. However, students who are motivated by grades or other extrinsic rewards are not necessarily only motivated by extrinsic rewards.

Low expectation of success on the part of the student : A student who does not believe they have the necessary knowledge and skills to successfully complete an assessment are more likely to resort to cheating.

In the next section, we’ll discuss how to address each of these characteristics so we can take a positive, rather than punitive, approach to teaching about academic integrity.

In Practice

From explicit communication to assessment design to student support, the strategies below will help you proactively promote academic integrity in your courses.

Be transparent about expectations

Good course design, coupled with transparency, can go a long way to reducing academic misconduct. Explicitly communicate to students your expectations for the course, for individual assessments and assignments, and for academic honesty and other behaviors you want them to demonstrate. Include language in your syllabus around academic integrity and discuss openly what that means and looks like at the start of term. Ensure students understand both the university expectations for academic integrity and the specific expectations for your course.

Align all assessments and assignments to learning outcomes and communicate that alignment clearly to students. Address any specific academic integrity expectations for a given assignment or assessment in the instructions. For example, make clear how resources should be used and cited, what types of collaboration are allowed or encouraged, how previous student work can be repurposed (if at all), and whether a quiz or test is “open book” or “open notes.” These clarifications will help students understand why their work matters, how it fits in the broader context of your course, and what they need to do to be successful while maintaining academic integrity.

Syllabus Language

See this sample syllabus statement for academic integrity and misconduct and the additional considerations in the Online and Hybrid Syllabus template provided by the Office of Distance Education and eLearning.

Communicate values

Support students to understand the values and communication conventions within your discipline. While an introductory composition course may help them learn fundamental concepts or habits, that is just the beginning. Explain to students that they are participating in a scholarly conversation—just as they would with their friends, they should respect the ideas that everyone contributes, including their own. Openly encouraging them to find their own voices as distinct from others can reduce the likelihood of plagiarism.

Beyond scholarly conversation, Lang suggests that educators must explain to students the importance of creating original work in their discipline.

"… I think these two questions are ones that students might pose to faculty in any discipline: how do I produce my own work in this discipline, and why does it matter that I produce my own work? Those two general questions, it seems to me, are ones that each discipline—and perhaps even each faculty member and each course—has to answer distinctively. And those two questions, it also seems to me, can help form the basis for the more substantial conversation you have with your students about academic honesty and dishonesty in your courses, in addition to the general conversation they might be having through educational campaigns on campus." (Lang, 2013, p. 194)

Lang teaches literature, so for him, original work means creating meaningful connections to other works, or to current events in the world. He reminds readers that building these connections leads to deeper learning as students create a more sophisticated mental network (Bransford, et al., 2000, Chapter 2).

If you teach in another discipline, your approach will be different. In the experimental sciences, for example, we often begin by replicating an experiment, fully or partially. We build on or extend it to test another hypothesis or look at the same hypothesis under different conditions. We get a result, we interpret the result, and this prompts more questions and hypotheses. In the sciences, we have a responsibility to be honest and accurate about those results (Committee on Science Engineering, and Public Policy, 1995).

Teach for mastery to de-emphasize performance

Students develop mastery when they acquire a set of skills, practice integrating those skills, and then know when to apply them (Ambrose, et al., 2010). They need opportunities to practice skills in isolation and in combination, and you should evaluate them in both situations. If students are weaker in some skills, provide additional support, perhaps in the form of tutorials or additional practice outside of class.

Build in opportunities for students to apply important skills in different contexts. Some students excel with certain types of assessments and not others. Providing multiple opportunities—and options—for assessment allows students a variety of ways to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

Lower the stakes

Among your assessments should be many lower stakes opportunities. For example, rather than giving one midterm and one final, include multiple exams or quizzes that are worth fewer points overall. Your students will benefit from the testing effect; Karpicke and Roedinger (2008) demonstrated that the more frequently students were tested on information, the more likely they were to retain that information.

Plan ways for students to practice for graded assessments during class time or through ungraded asynchronous activities. Autograded quizzes in Carmen that present a random set of questions aligned to appropriate learning outcomes make it possible for students to take a quiz as many times as needed until they get the answers right. Shorter assignments that are worth just a few points can help students practice—and get feedback on—what they need to do for a bigger project.

Scaffolding assignments is another way you can lower the stakes. Break a larger project or paper into manageable pieces and ask students to show their progress on each piece, so you can see how their work unfolds over time. You will get a sense of which students need more support earlier in the semester, preventing unpleasant surprises later.

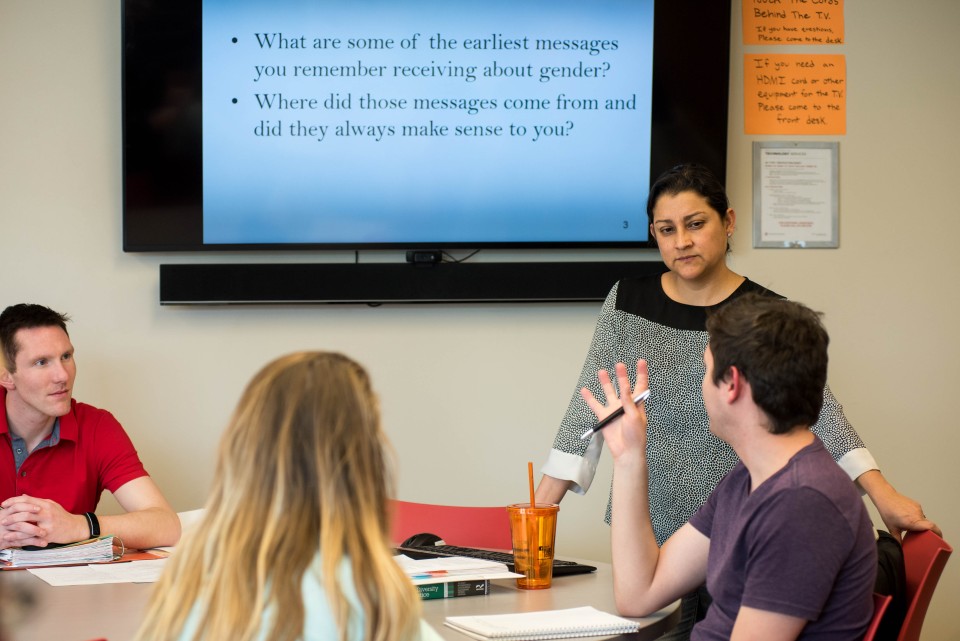

Foster intrinsic motivation

According to Bain (2004), “People learn best when they ask an important question that they care about answering.” Connecting your course material to students’ interests and personal lives beyond your class can increase their investment. For example, a freshman statistics seminar at Carnegie Mellon University, Statistics of Sexual Orientation, included rigorous statistical analysis while also dealing with theories about the LGBT population. The following are additional techniques for fostering student motivation (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Integrate real–world, authentic tasks so students can see the relevance of what they are learning.

Connect your course content to other courses students are taking or will take so they understand its place in the larger context of their educations.

Demonstrate how learned skills will be useful in students’ future professional lives.

Build students’ self-efficacy

In a chapter on student motivation, Ambrose et al. (2010) describe two parts to self-efficacy. First, students must believe they know what they need to know in order to succeed at a given task. Second, they must believe, when they begin that task, that they will succeed. Even if students have the necessary knowledge and skills, they may feel rushed on the task, that the instructor will not grade fairly, that other members in a group project will hinder their progress, or simply that they will not succeed. Imposter syndrome and stereotype threat can also affect students’ self-efficacy.

Lang (2013) and Ambrose et al. (2010) describe a variety of strategies for supporting student self-efficacy. One important strategy is to help students develop metacognition . Students who have an awareness of how they learn tend to be more successful learners. There are a variety of ways to support metacognitive thinking. For example, in STEM courses, separate problem-solving strategies from the actual computation to help students categorize problems into types and see deeper patterns. Ask students to review their graded work and reflect upon study strategies that worked or didn’t work for them (see “ exam wrappers ”). Explicitly guiding students to identify and leverage behaviors they can control, such as study strategies and time management, can increase their success. Sharing recommended study strategies and resources with students can give them options they may not have considered.

Dive deeper into strategies for Designing Assessments of Student Learning and Supporting Student Learning in Your Course .

Learning for Mastery

Building a question bank, student tips for preserving academic integrity.

By taking proactive approaches, you can make the shift from the defensive prevention of cheating to the creation of an environment in which students are less likely to cheat in the first place.

Key strategies for promoting academic integrity include:

Focus on positive messages rather than fear or the threat of punishment . Emphasizing the consequences of academic misconduct does not support students to understand why academic integrity matters.

Use good course design to reduce the chances of academic misconduct . Intentionally align assignments to learning outcomes and clearly communicate that alignment to students.

Provide transparent and explicit instruction and support around academic integrity . Students come to college with diverse backgrounds and values around appropriate academic behavior. Openly discuss what academic integrity looks like at the university and in the context of your course.

Explain the values and discourse of your discipline . Provide positive examples of how students can enact those values. This is a crucial piece of helping students see themselves as participants in the scholarly conversation of your discipline.

Teach for mastery and lower the stakes . Focusing on learning over grades and allowing students many opportunities to practice—and make mistakes—will lessen the anxiety around performance on bigger exams or projects.

Foster intrinsic motivation and help build students’ self-efficacy . Authentic assignments connected to student interests and a balance of challenge and support will keep students motivated.

You may do everything you can to proactively promote academic integrity but still encounter the occasional student who cheats. In the event that you need to report academic misconduct, consult these resources from the Office of Academic Affairs to familiarize yourself with your responsibilities and the university procedure.

- Academic Integrity and Misconduct (website)

- Academic Integrity in Online Courses (workshop recording)

- Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty (e-book)

- Instructor Resources for Choosing and Using Sources (website)

- International Center for Academic Integrity (website)

- Plagiarism, Intellectual Property and the Teaching of L2 Writing (book)

- Setting up Question Banks in Carmen (help article)

- Using question banks to randomize exam questions in Carmen (help article)

Learning Opportunities

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., Norman, M.K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bever, L. (2017). Dozens of Ohio State students accused of cheating ring that used group-messaging app. The Washington Post , 13 Nov. 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2017/11/13/dozens-of-ohio-state-students-accused-in-cheating-ring-using-group-messaging-app/

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., and Cocking, R.R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school . Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., McGowan, U., East, J., Green, M., Partridge, L., & James, C. (2014). ‘Teach us how to do it properly!’ An Australian academic integrity survey. Studies in Higher Education 37 (7): 1150---1169.

Bloch, Joel. (2012). Plagiarism, intellectual property and the teaching of L2 writing . Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy. (1995). On being a scientist: Responsible conduct in research . 2nd edition. Washington DC: National Academy Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232224/

DiPietro, M. (2009, Fall). Diversity content as a gateway to deeper learning: the statistics of sexual orientation. Diversity & Democracy 12 (3). https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/diversity-content-gateway-deeper-learning-statistics-sexual

Karpicke, J.K. and Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science 319 : 966-968.

Lang, James M. (2013). Cheating lessons: learning from academic dishonesty . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Morris. E.J. (2016). Academic integrity: A teaching and learning approach. Chapter 70 (pp. 1038-1051) in Bretag, T. (Ed.). Handbook of Academic Integrity . Singapore: Springer Science and Business Media.

Nelms, G. (2015, July 20). Why plagiarism doesn’t bother me at all: A research-based overview of plagiarism as an educational opportunity . Teaching and Learning in Higher Ed. https://teachingandlearninginhighered.org/2015/07/20/plagiarism-doesnt-bother-me-at-all-research/

Tatum, H. and Schwartz, B.M. (2017). Honor codes: Evidence based strategies for improving academic integrity. Theory into Practice 56 :129-135.

Related Teaching Topics

Shaping a positive learning environment, designing assessments of student learning, strategies and tools for academic integrity in online environments, related toolsets, carmencanvas, search for resources.

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Promoting Academic Integrity

While it is each student’s responsibility to understand and abide by university standards towards individual work and academic integrity, instructors can help students understand their responsibilities through frank classroom conversations that go beyond policy language to shared values. By creating a learning environment that stimulates engagement and designing assessments that are authentic, instructors can minimize the incidence of academic dishonesty.

Academic dishonesty often takes place because students are overwhelmed with the assignments and they don’t have enough time to complete them. So, in addition to being clear about expectations and responsibilities related to academic integrity, instructors should also invite students to plan accordingly and communicate with them in the event of an emergency. Instructors can arrange extensions and offer solutions in case that students have an emergency. Communication between instructors and students is vital to avoid bad practices and contribute to hold on to the academic integrity values.

The guidance and strategies included in this resource are applicable to courses in any modality (in-person, online, and hybrid) and includes a discussion of addressing generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT with students.

On this page:

What is academic integrity, why does academic dishonesty occur, strategies for promoting academic integrity, academic integrity in the age of artificial intelligence, columbia university resources.

- References and Additional Resources

- Acknowledgment

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Promoting Academic Integrity. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/academic-integrity/

According to the International Center for Academic Integrity , academic integrity is “a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage.” We commit to these values to honor the intellectual efforts of the global academic community, of which Columbia University is an integral part.

Academic dishonesty in the classroom occurs when one or more values of academic integrity are violated. While some cases of academic dishonesty are committed intentionally, other cases may be a reflection of something deeper that a student is experiencing, such as language or cultural misunderstandings, insufficient or misguided preparation for exams or papers, a lack of confidence in their ability to learn the subject, or perception that course policies are unfair (Bernard and Keith-Spiegel, 2002).

Some other reasons why students may commit academic dishonesty include:

- Cultural or regional differences in what comprises academic dishonesty

- Lack or poor understanding on how to cite sources correctly

- Misunderstanding directions and/or expectations

- Poor time management, procrastination, or disorganization

- Feeling disconnected from the course, subject, instructor, or material

- Fear of failure or lack of confidence in one’s ability

- Anxiety, depression, other mental health problems

- Peer/family pressure to meet unrealistic expectations

Understanding some of these common reasons can help instructors intentionally design their courses and assessments to pre-empt, and hopefully avoid, instances of academic dishonesty. As Thomas Keith states in “Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem.” faculty and administrators should direct their steps towards a “thoughtful, compassionate pedagogy.”

The CTL is here to help!

The CTL can help you think through your course policies and ways to create community, design course assessments, and set up CourseWorks to promote academic integrity. Email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

In his research on cheating in the college classroom, James Lang argues that “the amount of cheating that takes place on our campuses may well depend on the structures of the learning environment” (Lang, 2013a; Lang, 2013b). Instructors have agency in shaping the classroom learning experience; thus, instances of academic dishonesty can be mitigated by efforts to design a supportive, learning-oriented environment (Bertam, 2017 and 2008).

Understanding Student’s Perceptions about Cheating

It is important to know how students understand critical concepts related to academic integrity such as: cheating, transparency, attribution, intellectual property, etc. As much as they know and understand these concepts, they will be able to show good academic integrity practices.

1. Acknowledge the importance of the research process, not only the outcome, during student learning.

Although the research process is slow and arduous, students should understand the value of the different processes involved during academic writing: investigation, reading, drafting, revising, editing and proof-reading. For Natalie Wexler, using generative Artificial Intelligence tools like ChatGPT as a substitute of writing itself is beyond cheating, an act of self cheating: “The process of writing itself can and should deepen that knowledge and possibly spark new insights” (“‘ Bots’ Can Write Good Essays, But That Doesn’t Make Writing Obsolete” ).

Ways to understand the value of writing their own work without external help, either from external sources, peers or AI, hinge on prioritizing the process over the product:

- Asking students to present drafts of their work and receive feedback can help students to gain confidence to continue researching and writing.

- Allowing students the freedom to choose or change their research topic can increase their investment in an assignment, which can motivate them to conduct their own writing and research rather than relying on AI tools.

2. Create a supportive learning environment

When students feel supported in a course and connected to instructors and/or TAs and their peers, they may be more comfortable asking for help when they don’t understand course material or if they have fallen behind with an assignment.

Ways to support student learning include:

- Convey confidence in your students’ ability to succeed in your course from day one of the course (this may ease student anxiety or imposter syndrome ) and through timely and regular feedback on what they are doing well and areas they can improve on.

- Explain the relevance of the course to students; tell them why it is important that they actually learn the material and develop the skills for themselves. Invite students to connect the course to their goals, studies, or intended career trajectories. Research shows that students’ motivation to learn can help deter instances of academic dishonesty (Lang, 2013a).

- Teach important skills such as taking notes, summarizing arguments, and citing sources. Students may not have developed these skills, or they may bring bad habits from previous learning experiences. Have students practice these skills through exercises (Gonzalez, 2017).

- Provide students multiple opportunities to practice challenging skills and receive immediate feedback in class (e.g., polls, writing activities, “boardwork”). These frequent low-stakes assessments across the semester can “[improve] students’ metacognitive awareness of their learning in the course” (Lang, 2013a, pp. 145).

- Help students manage their time on course tasks by scheduling regular check-ins to reduce students’ last minute efforts or frantic emails about assignment requirements. Establish weekly online office hours and/or be open to appointments outside of standard working hours. This is especially important if students are learning in different time zones. Normalize the use of campus resources and academic support resources that can help address issues or anxieties they may be facing. (See the Columbia University Resources section below for a list of support resources.)

- Provide lists of approved websites and resources that can be used for additional help or research. This is especially important if on-campus materials are not available to online learners. Articulate permitted online “study” resources to be used as learning tools (and not cheating aids – see McKenzie, 2018) and how to cite those in homework, writing assignments or problem sets.

- Encourage TAs (if applicable) to establish good relationships with students and to check-in with you about concerns they may have about students in the course. (Explore the Working with TAs Online resource to learn more about partnering with TAs.)

3. Clarify expectations and establish shared values

In addition to including Columbia’s academic integrity policy on syllabi, go a step further by creating space in the classroom to discuss your expectations regarding academic integrity and what that looks like in your course context. After all, “what reduces cheating on an honor code campus is not the code itself, but the dialogue about academic honesty that the code inspires. ” (Lang, 2013a, pp. 172)

Ways to cultivate a shared sense of responsibility for upholding academic integrity include:

- Ask students to identify goals and expectations around academic integrity in relation to course learning objectives.

- Communicate your expectations and explain your rationale for course policies on artificial intelligence tools, collaborative assignments, late work, proctored exams, missed tests, attendance, extra credit, the use of plagiarism detection software or proctoring software, etc. It will make a difference to take the time at the beginning of the course to explain differences between quoting, summarizing and paraphrasing. Providing examples of good and bad quotation/paraphrasing will help students to know what constitutes good academic writing.

- Define and provide examples for what constitutes plagiarism or other forms of academic dishonesty in your course.

- Invite students to generate ideas for responding to scenarios where they may be pressured to violate the values of academic integrity (e.g.: a friend asks to see their homework, or a friend suggests using chat apps during exams), so students are prepared to react with integrity when suddenly faced with these situations.

- State clearly when collaboration and group learning is permitted and when independent work is expected. Collaboration and group work provide great opportunities to build student-student rapport and classroom community, but at the same time, it can lead students to fall into academic misconduct due to unintended collaboration/failure to safeguard their work.

- Discuss the ethical, academic, and legal repercussions of posting class recordings, notes and/or class materials online (e.g., to sites such as Chegg, GitHub, CourseHero – see Lederman, 2020).

- Partner with TAs (if applicable) and clarify your expectations of them, how they can help promote shared values around academic integrity, and what they should do in cases of suspected cheating or classroom difficulties

4. Design assessments to maximize learning and minimize pressure

High stakes course assessments can be a source of student anxiety. Creating multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning, and spreading assessments throughout the semester can lessen student stress and keep the focus on student learning (see Darby, 2020 for strategies on assessing students online). As Lang explains, “The more assessments you provide, the less pressure you put on students to do well on any single assignment or exam. If you maintain a clear and consistent academic integrity policy, and ensure that all students caught cheating receive an immediate and substantive penalty, the benefit of cheating on any one assessment will be small, while the potential consequences will be high” (Lang, 2013a and Lang, 2013c). For support with creating online exams, please please refer to our Creating Online Exams resource .

Ways to enhance one’s assessment approach:

- Design assignments based on authentic problems in your discipline. Ask students to apply course concepts and materials to a problem or concept.

- Structure assignments into smaller parts (“scaffolding”) that will be submitted and checked throughout the semester. This scaffolding can also help students learn how to tackle large projects by breaking down the tasks.

- Break up a single high-stakes exam into smaller, weekly tests. This can help distribute the weight of grades, and will lessen the pressure students feel when an exam accounts for a large portion of their grade.

- Give students options in how their learning is assessed and/or invite students to present their learning in creative ways (e.g., as a poster, video, story, art project, presentation, or oral exam).

- Provide feedback prior to grading student work. Give students the opportunity to implement the feedback. The revision process encourages student learning, while also lowering the anxiety around any one assignment.

- Utilize multiple low-stakes assignments that prepare students for high-stakes assignments or exams to reduce anxiety (e.g., in-class activities, in-class or online discussions)

- Create grading rubrics and share them with your students and TAs (if applicable) so that expectations are clear, to guide student work, and aid with the feedback process.

- Use individual student portfolio folders and provide tailored feedback to students throughout the semester. This can help foster positive relationships, as well as allow you to watch students’ progress on drafts and outlines. You can also ask students to describe how their drafts have changed and offer rationales for those decisions.

- For exams , consider refreshing tests every term, both in terms of organization and content. Additionally, ground your assignments by having students draw connections between course content and the unique experience of your course in terms of time (unique to the semester), place (unique to campus, local community, etc. ), personal (specific student experiences), and interdisciplinary opportunities (other courses students have taken, co-curricular activities, campus events, etc.). (Lang, 2013a, pp. 77).

Since its release, ChatGPT has raised concern in universities across the country about the opportunity it presents for students to cheat and appropriate AI ideas, texts, and even code as their own work. However, there are also potential positive uses of this tool in the learning process–including as a tool for teachers to rely on when creating assessments or working with repetitive and time-consuming tasks.

Possible Advantages of ChatGPT

Due to the novelty of this tool, the possible advantages that might present in the teaching-learning process should be under the control of each instructor since they know exactly what they expect from students’ work.

Prof. Ethan Mollick teaches innovation and entrepreneurship at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and has been openly sharing on his Twitter account his journey incorporating ChatGPT into his classes. Prof. Mollick advises his students to experiment with this tool, trying and retrying prompts. He recognizes the importance of acknowledging its limits and the risks of violating academic honesty guidelines if the use of this tool is not stated at the end of the assignment.

Prof. Mollick uncovers four possible uses of this AI tool, ranging from using ChatGPT as an all-knowing intern, as a game designer, as an assistant to launch a business, or even to “hallucinate” together ( “Four Paths to the Revelation” ). For Prof. Mollick, ChatGPT is a useful technology to craft initial ideas, as long as the prompts are given within a specific field, include proper context, step-by-step directions and have the proper changes and edits.

Resources for faculty:

- Academic Integrity Best Practices for Faculty (Columbia College & School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

- Faculty Statement on Academic Integrity (Columbia College)

- FAQs: Academic Integrity from Columbia Student Conduct and Community Standards

- Ombuds Office for assistance with academic dishonesty issues.

- Columbia Center of Artificial Intelligence Technology

Resources for students:

- Policies from Columbia Student Conduct and Community Standards

- Understanding the Academic Integrity Policy (Columbia College & School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

Student support resources:

- Maximizing Student Learning Online (Columbia Online)

- Center for Student Advising Tutoring Service (Berick Center for Student Advising)

- Help Rooms and Private Tutors by Department (Berick Center for Student Advising

- Peer Academic Skills Consultants (Berick Center for Student Advising)

- Academic Resource Center (ARC) for School of General Studies

- Center for Engaged Pedagogy (Barnard College)

- Writing Center (for Columbia undergraduate and graduate students)

- Counseling and Psychological Services

- Disability Services

For graduate students:

- Writing Studio (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

- Student Center (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

- Teachers College

Columbia University Information Technology (CUIT) CUIT’s Academic Services provides services that can be used by instructors in their courses such as Turnitin , a plagiarism detection service and online proctoring services such as Proctorio , a remote proctoring service that monitors students taking virtual exams through CourseWorks.

Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) The CTL can help you think through your course policies, ways to create community, design course assessments, and setting up CourseWorks to promote integrity, among other teaching and learning facets. To schedule a one-on-one consultation, please contact the CTL at [email protected] .

References

Bernard, W. Jr. and Keith-Spiegel, P. (2002). Academic Dishonesty: An Educator’s Guide . Mahwah, NJ: Psychology Press.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2017). Academic Integrity as a Teaching and Learning Issue: From Theory to Practice . Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 88-94.

Bertram Gallant, T. (Ed.). (2008). Academic Integrity in the Twenty-First Century: A Teaching and Learning Imperative . ASHE Higher Education Report . 33(5), 1-143.

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Creating Online Exams .

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Working with TAs online .

Darby, F. (2020). 7 Ways to Assess Students Online and Minimize Cheating . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Gonzalez, J. (2017, February). Teaching Students to Avoid Plagiarism . Cult of Pedagogy, 26.

International Center for Academic Integrity (2023). Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity .

International Center on Academic Integrity (2023). https://academicintegrity.org/

Keith, T. Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem. The University of Chicago. (2022, Feb 16).

Lang, J.M. (2013a). Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty . Harvard University Press.

Lang, J. M. (2013b). Cheating Lessons, Part 1 . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lang, J. M. (2013c). Cheating Lessons, Part 2 . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lederman, D. (2020, February 19). Course Hero Woos Professors . Inside Higher Ed.

McKenzie, L. (2018, May 8). Learning Tool or Cheating Aid? Inside Higher Ed.

Marche, S. (2022, Dec 6). The College Essay is Dead. The Atlantic.

Mollick, E. (2023, Jan 17). All my Classes Suddenly Became AI Classes. One Useful Thing.

Mollick, Ethan. (2022, Dic 8). Four Paths to the Revelation. One Useful Thing.

Wexler, N. Bots’ Can Write Good Essays, But That Doesn’t Make Writing Obsolete. Minding the Gap.

Additional Resources

Bretag, T. (Ed.). (2016). Handbook of Academic Integrity. Singapore: Springer Publishing.

Ormand, C. (2017 March 6). SAGE Musings: Minimizing and Dealing with Academic Dishonesty . SAGE 2YC: 2YC Faculty as Agents of Change.

WCET (2009). Best Practice Strategies to Promote Academic Integrity in Online Education .

Thomas, K. (2022 February 16). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 February 25). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 2: Small Steps to Discourage Academic Dishonesty. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 April 28). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 3: Towards a Pedagogy of Academic Integrity. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 June 7). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 4: Library Services to Support Academic Honesty. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

Acknowledgement

This resource was adapted from the faculty booklet Promoting Academic Integrity & Preventing Academic Dishonesty: Best Practices at Columbia University developed by Victoria Malaney Brown, Director of Academic Integrity at Columbia College and Columbia Engineering, Abigail MacBain and Ramón Flores Pinedo, PhD students in GSAS. We would like to thank them for their extensive support in creating this academic integrity resource.

Want to communicate your expectations around AI tools?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Academic Honesty: Why It Matters in Psychology

In psychology, academic honesty is about so much more than getting in trouble..

Posted April 17, 2021 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- All colleges and universities have academic honesty policies with serious consequences.

- Websites that pay to write student papers violate academic honesty and are becoming more abundant and aggressive.

- Academic honesty is inherently psychological, involving questions of curiosity, trust, morality, and future orientation.

The other day, while looking for a free plagiarism checker to use in addition to the one provided by my institution, I came across a website blatantly selling papers to students. This particular site promises, for a high fee per page, to write students completely unique papers that won’t get caught as plagiarism. They’ll even write your Ph.D. dissertation for you (uh…good luck defending that).

All professors are familiar with these sites. The fact that students are paying others to produce work for them is not a secret, at all. Most of us have caught students doing this, or versions of it, and though it’s exhausting and demoralizing, we’ve learned to deal with it semester after semester.

What is academic honesty?

This behavior falls under the heading of “academic honesty.” All colleges and universities have academic honesty policies that address issues like plagiarism and cheating, including serious consequences for violating them. I, for one, am particularly adept at detecting copy/paste/change-a-few-words plagiarism. Frankly, half the time it’s obvious because it’s incomprehensible. As many professors will commiserate, if I wasn’t so good at detecting it, life would be much easier.

Most of us on the policy enforcement side can relate stories with versions of, “But I bought the paper! I didn’t plagiarize, the person who wrote it did! I shouldn’t be held responsible!” In fact, I receive more and more pushback like that every semester: “My cousin wrote the paper for me and I had no idea she plagiarized! She should get in trouble, not me!”

Where does academic dishonesty come from?

We certainly understand that issues like plagiarism may come from lack of confidence in one’s writing skills, being unprepared for college, pressure, inaccessible resources, and the like, but overall, I’ve found it to be a matter of buy-in. Either students buy in to the concept of academic honesty or they don’t, and this has implications beyond school.

How is academic honesty linked to psychology?

I’m less concerned with magically convincing students to follow academic honesty policies than I am in getting them to think about why it is important in the context of psychology. Though I am indeed a prevention practitioner, I’m not naïve enough to think I can change someone’s mind about the value of academic honesty. I am, however, hopeful that those studying psychology will consider the following connections (and then some):

- Learning – You’re not learning much if you’re not doing the work. I once listened to an NPR story about students purchasing papers in which a student said, “I feel like I am doing my own work because I’m using my own money.” Come on. Psychology is all about learning. It’s a topic in every introductory psychology course. It’s usually an entire chapter in introductory psychology textbooks. We have classes specifically focused on it. One of the foundations of learning is that the learner be…involved.

- Morality – “What is moral?” students ask. I can’t answer that, but I am pretty confident that cheating is not. Again, this is a topic that is usually covered in introductory psychology and then over and over again in developmental psychology, social psychology, and more. You’ll even find “moral psychology” as its own field. Psychologist Lawrence Kholberg asked if subjects would steal a drug. Today, he could ask if you’d buy a term paper.

- Future orientation – Personality psychology research suggests that those with a “future orientation” tend to have better outcomes than those with a “present orientation.” The idea is that if you have a future orientation, you tend to, well, look to the future and anticipate future outcomes more than those who are focused solely on the present. While a concern with consequences is associated with mortality (e.g. Kholberg’s theory), the ability or tendency to envision potential consequences is associated with a future orientation. Could there be a more psychological question than, “Is it worth it?”

- Conscientiousness and trust – Conscientiousness is a core personality trait. Trust is essential in development and relationships. Academic dishonesty violates trust and displays low conscientiousness.

- Human services – Students often take psychology because it’s required for medical careers, careers involving working with children, and other human service careers. Go back to the first point about learning. I once had a nurse who tried to inject Heparin directly into my muscle. I had to fight to get her to inject it subcutaneously, as directed. When you work in a hospital, on a general surgery floor, not knowing where to safely inject a blood thinner is alarming. When you don’t do your own work, you don’t have a chance to learn and for a discipline preparing students to work with humans, especially children, everything associated with academic honesty, all of the above, is essential.

- Personal fable – Simply put, this component of David Elkind’s adolescent egocentrism theory suggests that adolescents tend to think they are special and unique. “It might happen to you, but it won’t happen to me.” I can’t tell you how many students are shocked and very angry when caught. In fact, I once read a Twitter thread from professors about the very real dangers associated with catching plagiarism. Many students are still in adolescence , and thinking you’re an exception who won’t get caught is a sure sign.

- Entitlement and violence – Speaking of anger, the idea that you’re special is linked to entitlement , a very psychological concept. In fact, those who study education research “academic entitlement,” in which students feel they should get a good grade just because they attended class or just because they turned in work. Having worked in domestic and sexual violence for a very long time, I know that entitlement is often coupled with violence, as challenges to one’s sense of entitlement frequently result in anger and aggression . Linking homework to violence seems incredible, but it’s a very real possibility.

- Behavioral consistency – As much as we may want to, professors generally can’t share information about other students with other professors. There’s no, “Hey, watch out for this student, they told me their cousin is doing all their homework for them.” However, all academic honesty policies do require some level of reporting to campus administration and they know about behavioral consistency, another psychological concept. This concept suggests that people tend to behave in a consistent manner; they behave in ways that match their past behavior. Need I say more?

One of the main reasons for academic honesty is scientific integrity. I didn’t address it above because, frankly, I find that’s not a very convincing argument, especially when these “pay for us to do your homework” sites target students so aggressively. I found a few more of these sites and recently used their online chat tool. Before I disclosed that I am a professor, and subsequently got kicked off, every single one guaranteed that my professor and my institution “wouldn’t find out.” That’s appalling, not just for the reasons above, but because we do find out, and it can ruin a student’s entire academic career .

Psychology is fascinating and fun. Why wouldn’t you want to learn it, anyway?

Ashley Maier teaches psychology at Los Angeles Valley College.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What is academic integrity? | Academic integrity definition

Building an awareness of inequities, and empowering ourselves as educators to promote academic integrity and making it more inclusive, is a first step towards making education a “great equalizer.”

When students come from outside the racial, ethnic, and cultural mainstream, they have greater learning challenges. Students not familiar with the vernacular of a classroom or even the language, have to make huge adjustments to navigate learning. One way for educators to address this gap is through culturally responsive pedagogy.

By completing this form, you agree to Turnitin's Privacy Policy . Turnitin uses the information you provide to contact you with relevant information. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

Academic integrity is more than a policy to uphold at your institution. While academic integrity should be addressed in honor codes, it is also important to understand its meaning and uphold it at all levels, from explicit instruction to formative feedback to final assessment. Academic integrity, too, is a set of values to enact throughout a student’s learning experience into the workplace with a lifelong commitment to learning.

Having a concrete definition of academic integrity to be used within a classroom setting is important in order to action the term. While it’s easy to define academic integrity as what it is not (i.e., not plagiarizing, not contract cheating, not engaging in AI Writing misconduct), it is important to define it in practical and actionable ways.

The word “academic integrity,” in sum, entails a commitment to honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage.

An authoritative definition of academic integrity can be found at the International Center of Academic Integrity (ICAI) , which was founded in 1992 by leading researchers. Don McCabe spearheaded its founding and is credited as the person who popularized the term “academic integrity.” In 1999, the Center identified and described the “ fundamental values of academic integrity ” as honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility, and in 2014 added the sixth value of courage. Academic integrity, per the ICAI, is a commitment to these values.

Academic integrity is not only a definition, but a set of values to uphold. The components of academic integrity are enacted in the following ways:

- Honesty: be truthful, give credit, and provide facts

- Trust: provide transparency, trust others, give credence

- Fairness: apply rules consistently, engage with others equitably, and take responsibility for our own actions

- Respect: receive feedback willingly, accept others’ thoughts, and recognize the impacts of our own words and actions on others

- Responsibility: follow institutional rules and conduct codes, engage in difficult conversations, and model good behavior

- Courage: take a stand to address wrongdoing, be undaunted in defending integrity, and endure discomfort for something you believe in ( ICAI, 2020 )

According to research by Guerrero-Dib, Portales, and Heredia-Escorza, “Academic integrity is much more than avoiding dishonest practices such as copying during exams, plagiarizing or contract cheating; it implies an engagement with learning and work which is well done, complete, and focused on a good purpose— learning. It also involves using appropriate means, genuine effort and good skills. Mainly it implies diligently taking advantage of all learning experiences” ( International Journal for Educational Integrity, 2020 ).

Academic integrity goes beyond avoiding cheating or plagiarizing. Academic integrity is also about maintaining excellent academic standards in teaching and curriculum and fostering impeccable research processes. Academic integrity requires full institutional and instructor effort as well as the vigilance of individuals in the learning process. Not only should students not cheat, but educators offer accurate assessments, and institutions support honest research practices and when applicable, fair discipline.

In 2010, after years of active participation from international communities like Australia, Canada, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates, the ICAI added “international” to its name.

The ICAI, without a doubt, has done groundbreaking work and rallied the world to uphold academic integrity. But it is also important to note that this prior work is largely rooted in the Western world, and there is still much to be done when it comes to promoting academic integrity around the world.

For starters, cultural differences can challenge the ICAI definition of academic integrity.

According to Tran, Hogg, & Marshall, research shows that students who come from rote-learning habits view plagiarism as a less serious offense. Additionally, Western-based plagiarism values may conflict with various cultures ( 2022 ).

Collectivist cultures, for example, define respect in a way that can uphold mimicry, prioritizing rote memorization above all else. Mimicry itself is a sign of respect. Professor Tosh Yamamoto of Kansai University described Japanese perspectives on academic integrity for Turnitin. Yamamoto states, “Academic integrity is, I believe, a philosophical mindset to reflect the learning mind to the mirror of honesty, sincerity, contribution to the future society, and also scientific attitude and ethics and morals. However, on the other hand, education in Japan is focused on rote memorization and regurgitation and understanding” ( Yamamoto, 2021 ).

In fact, there may be instances in which paraphrasing or adding original ideas to a text is seen as a form of disrespect. Mimicry makes plagiarism a very possible outcome. This cultural context with regards to respect, then, runs counter to intentions of the ICAI definition of academic integrity.

In other parts of the world, citations themselves may be fraught and a sign of disrespect. Quoting or paraphrasing well-known texts without attribution is common in, for instance, the Middle East. Teachers are expected to know sources to such ideas; this is otherwise known as “communal ownership of knowledge.” In fact, this expectation is endemic to such a degree that including a citation may be received as patronizing or even insulting to the instructor ( Sowden, 2005 ).

Additionally, there are areas of the world that literally do not have a word for academic integrity; like Japan, for instance. In other countries like Eritrea, copyright protection simply doesn’t exist. And in Latvia, “the Latvian academic terminology database AkadTerm does not include terms such as academic integrity,’ ‘academic honesty,’ and ‘academic misconduct’” ( Tauginiené, et al. 2019 ).

Academic integrity is a western term, one that many institutions follow, and an ideal that we should all uphold. Still, it is important to note academic integrity’s cultural roots so that educators can support students from different parts of the world to understand how to conduct work within a western framework, particularly when studying abroad.

That said, academic integrity is a global expectation. In our changing, post-industrial world, students and institutional goals include entering a global marketplace of ideas. And it is more important than ever that those ideas be original and authentic.

According to 2013 research, “The education landscape has been shifting towards a stronger emphasis on higher-order level of thinking such as creative thinking, critical thinking, and problem solving as research shows that current graduates lack transcending skills like communication skills and problem-solving skills, which are crucial in the industry. The most important skills employers look for when hiring new employees are teamwork, critical thinking, communication...or innovative thinking” ( Ju, Mai, et al. ).

Academic integrity is critical to some of the following areas:

- Fostering the positive reputations of institutions and individuals

- Future workplace behavior

Academic misconduct, simply put, shortcuts learning. When learning isn’t measured accurately because either the student’s answers are not their own or because the person who graded the essay is a ghost-grader who doesn’t provide accurate feedback, there is no way to support students towards next steps. Students don’t receive the feedback they need to learn. When the work is not the student’s own original thoughts, they lose learning opportunities.

Accurate assessment also provides instructors with data on student knowledge, such as learning gaps that can be bridged. When student’s answers are not their own, it’s impossible for educators to have an accurate measurement of learning and to provide feedback or make appropriate changes to a teaching curriculum and bridge learning gaps.

If this information exchange is muddied due to misconduct, learning is stymied.

Academic integrity also fosters respect for the learning process and is critical for life-long learning.

In their research, Guerrero-Dib, Portales, and Heredia-Escorza state, “Academic integrity is much more than avoiding dishonest practices such as copying during exams, plagiarizing or contract cheating; it implies an engagement with learning and work which is well done, complete, and focused on a good purpose – learning” ( 2020 ).

While shortcut solutions belittle education, academic integrity takes advantage of and embraces every learning opportunity. When for instance quotes are attributed, research is acknowledged, data is accurate, and knowledge exchange is upheld and respected.

Knowledge is a university’s product; academic integrity is linked to education integrity. When students graduate from an institution having learned what the institution’s diploma represents and embodies the values of that institution, reputations are upheld. An institution’s academic reputation is essential to a university community, credibility, and financial stability, whether via admissions or donations from third parties.

On the other hand, academic misconduct scandals can erode the value of a degree. If students are not learning course material, then it follows that their knowledge does not reflect a valid education. Furthermore, in fields like nursing, this deficit can have serious life and death consequences. Scandals, too, have financial impacts on institutions.

In their paper, “The Impact of College Scandals on College Applications,” Michael Luca, Patrick Rooney, and Jonathan Smith, researchers from the Harvard Business School and the College Board, state:

“Scandals with more than five mentions in The New York Times lead to a 9 percent drop in applications at the college the following year. Colleges with scandals covered by long-form magazine articles receive 10 percent fewer applications the following year. To put this into context, a long-form article decreases a college’s number of applications roughly as much as falling 10 places in the U.S. News and World Report college rankings.”

Enrollment is a university’s financial bread-and-butter, particularly for those without large financial endowments. Universities benefit in other ways from popularity. According to Dr. Aldemaro Romero Jr., “The more and better students an institution can enroll, the more it can claim a level of prestige. And if the numbers of applicants increase—because of the perceived prestige—institutions become more selective in admissions. This, in turn, increases retention and graduation rates” ( 2016 ).

An institution’s reputation is more important than ever, given the trend of universities closing down, with The Hechinger Report citing declining student enrollment as the leading cause of campus closures ( Barshay, 2022 ).

Attached to a university’s academic reputation is its research component; in the field of research, scandals can stain reputations and impact factors , ending the academic careers of individuals. Research is a cumulative, interactive process, one that must prioritize academic honesty to provide innovation without fraud—as well as provide critical knowledge to bettering the world.

School is not just about learning the content of subject matter but nurturing a love of learning and ability to share knowledge in an equitable manner. And what students learn in school informs an entire life. The friends made in college, the community building within residential halls, study habits, the cultures to which students are exposed on campus, and the quality of mentorship are some of the many components of higher education that can influence a person’s life.

There is an adage, “ Past behavior is the best indicator of future behavior .”

To that end, numerous research studies show that academic dishonesty in school leads to workplace deviance ( Blankenship & Whitley 2000, Harding, et al. 2004, Lawson 2004, Nonis & Swift 2001, & Sims 1993 ). Those who engage in misconduct during university are more likely to lie, cheat, and steal later on in the workplace ( Druica, et al., 2019 ).

Which can lead to the question of whether or not academic integrity in school upholds workplace honesty. Recent 2021 research states that “Tolerating dishonest behaviors in college seems to support dishonest students who may continue to be dishonest in the future. Thus, maintaining academic integrity in college may increasingly contribute to the credibility of the workplace” ( Mulisa & Ebissa, 2021 ).

While academic dishonesty in college leads to workplace misconduct, the opposite can hold true as well: academic integrity is an indicator of future workplace integrity. It is important to nurture academic integrity early to promote future success and to make clear academic integrity’s importance to students.

Academic integrity can also be defined by what not to do.

Despite best efforts, misconduct occurs. In March 2020, ICAI researchers surveyed 840 students across multiple college campuses (the geographical region was not specified). They found that 32 percent of undergraduates freely admitted to “cheating in any way on an exam.” Additionally, they survived 70,000 high school students at over 24 high schools in the United States. In that survey, researchers found that “58 percent admitted to plagiarism and 95 percent said they participated in some form of cheating” ( ICAI, 2020 ).

Academic dishonesty, or the violation of academic integrity principles, manifests in different ways and in different forms of misconduct. Collusion , copy-paste plagiarism , usage of electronic cheating devices, access to online test banks , abuse of word spinners , self-plagiarism (including as a researcher ), contract cheating , data manipulation, and the emerging trend of AI Writing misconduct , are all examples of academic misconduct as shown on Turnitin’s Plagiarism Spectrum 2.0 infographic.

All of the above examples misrepresent knowledge, violate trust, disrespect the learning process, shirk responsibility, and are unfair to oneself and others. In sum, they violate academic integrity. And in doing so, they all shortcut learning.

Ceceilia Parnther states, “Students learn what educators value and what we don’t care about—as well as who we hold to certain standards and who we don’t” (University of Calgary, October 2020 ). When it comes to academic integrity, it is important to set expectations and then model academic integrity for students. There are several ways to uphold academic integrity, including:

- Academic policies, honor codes, and equitable discipline

- Understanding who cheats, why, and shepherding students towards academic integrity

- Variety of assessment types and assessment design

Let’s look at each of these in depth to understand how students can benefit from the framework that academic integrity provides.

Honor codes make explicit institutional expectations. It is critical to show students that academic integrity is important via policies, honor codes, assessment design, support, and equitable discipline that supports the learning journey. As stated earlier, what students learn in school informs an entire life: how educators enact academic integrity is as important as stating its importance.

When there is a university plagiarism policy that is carefully worded, students deepened their understanding of academic integrity. Furthermore, researchers found that honor codes are an effective way to impress the seriousness of academic misconduct ( Brown & Howell, 2001 ).

Ensure that disciplinary action provides opportunities for students to transform plagiarism into a teachable moment .

Instead of a “zero tolerance” policy, consider a restorative approach (Sopcak) that can help students learn from past mistakes and move forward in their learning journey and possibly become advocates for academic integrity. This approach also models academic integrity by modeling the foundational values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage

Students who feel no value in assessments may cheat. Students who excel in their studies but feel the pressure to be “perfect,” may cheat. Students who are struggling and have no vested interest in the subject matter may cheat. Students who feel peer pressure to “help” fellow students may cheat. The list goes on. There is no one profile of a student who cheats. But understanding the push and pull factors of shortcut solutions can help educators mitigate academic misconduct.

Approaches on upholding academic integrity involve systemic, institutional, parental, instructional, as well as student involvement. Building a culture of academic integrity bolsters student courage to stand up for what is right. Some approaches include:

- Provide explicit instruction on academic integrity and academic misconduct within classrooms to level-set knowledge for students coming from diverse educational backgrounds.

- Include the definition in course syllabi .

- And set a foundation for students by creating a sense of belonging .

According to Tran, Hogg, & Marshall’s 2022 research, “Explicit plagiarism training makes a difference. A training session on referencing improved Chinese students’ knowledge of referencing and plagiarism (Du, 2020 ) and a 13-week course on plagiarism-related issues enhanced international students’ academic writing skills and understanding of plagiarism (Tran, 2012 ). Perkins and Roe ( 2020 ) revealed the effectiveness of an academic English master class on Vietnamese students’ understanding of academic conventions” ( Tran, Hogg, & Marshall 2022 ).

Offer inclusive and formative assessments with a variety of formats so students with different learning styles can practice and receive feedback while failing safely .

Assessment design is widely regarded as one of the most effective ways to mitigate misconduct and help students understand the relevance of assignments, quizzes, tests, or exams. Creating assignments, quizzes, tests, exams, projects, and all the ways to measure learning outcomes are a critical component to upholding academic honesty. Ensuring that assessments are designed to be inclusive and test what has been taught is one way to model integrity. A variety of formats and frequent, low-stakes assessments ensure that students feel supported.

To that end, provide frequent, low-stakes assessments to support student learning. Consider replacing high-stakes exams with low-stakes assessments. Design assessments that test what has been taught in order to lower student stress and increase fairness. Consider designing questions specific to your course or class discussions and avoid generic questions so as to avoid contract cheating. Provide rubrics so that students understand the relevance of the assessment to their learning.

Finally, there are plagiarism detection or similarity tools like Turnitin Feedback Studio . These are a backstop solution to academic dishonesty and should not be a first step in upholding academic integrity in the classroom. They can, however, act as a deterrent and if needed, provide data for Courageous Conversations about misconduct with students.

In sum, academic integrity is a concept that must be backed up by institutional policies, curriculum, teaching interventions, assessment design, and feedback loops that strengthen a student’s bond to learning. By making learning a positive experience, academic integrity can remain in an individual’s life throughout school and into their lifelong journey.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Academic Integrity

Responsible research and writing habits

Generative ai (artificial intelligence).

- Using Sources and AI

- From Research to Writing

- GSD Writing Services

- Grants and Fellowships

- Reading, Notetaking, and Time Management

- Theses and Dissertations

Need Help? Be in Touch.

- Ask a Design Librarian

- Call 617-495-9163

- Text 617-237-6641

- Consult a Librarian

- Workshop Calendar

- Library Hours

Central to any academic writing project is crediting (or citing) someone else' words or ideas. The following sites will help you understand academic writing expectations.

Academic integrity is truthful and responsible representation of yourself and your work by taking credit only for your own ideas and creations and giving credit to the work and ideas of other people. It involves providing attribution (citations and acknowledgments) whenever you include the intellectual property of others—and even your own if it is from a previous project or assignment. Academic integrity also means generating and using accurate data.

Responsible and ethical use of information is foundational to a successful teaching, learning, and research community. Not only does it promote an environment of trust and respect, it also facilitates intellectual conversations and inquiry. Citing your sources shows your expertise and assists others in their research by enabling them to find the original material. It is unfair and wrong to claim or imply that someone else’s work is your own.

Failure to uphold the values of academic integrity at the GSD can result in serious consequences, ranging from re-doing an assignment to expulsion from the program with a sanction on the student’s permanent record and transcript. Outside of academia, such infractions can result in lawsuits and damage to the perpetrator’s reputation and the reputation of their firm/organization. For more details see the Academic Integrity Policy at the GSD.

The GSD’s Academic Integrity Tutorial can help build proficiency in recognizing and practicing ways to avoid plagiarism.

- Avoiding Plagiarism (Purdue OWL) This site has a useful summary with tips on how to avoid accidental plagiarism and a list of what does (and does not) need to be cited. It also includes suggestions of best practices for research and writing.

- How Not to Plagiarize (University of Toronto) Concise explanation and useful Q&A with examples of citing and integrating sources.

This fast-evolving technology is changing academia in ways we are still trying to understand, and both the GSD and Harvard more broadly are working to develop policies and procedures based on careful thought and exploration. At the moment, whether and how AI may be used in student work is left mostly to the discretion of individual instructors. There are some emerging guidelines, however, based on overarching values.

- Always ask first if AI is allowed and specifically when and how.

- Always check facts and sources generated by AI as these are not reliable.

- Cite your use of AI to generate text or images. Citation practices for AI are described in Using Sources and AI.

Since policies are changing rapidly, we recommend checking the links below often for new developments, and this page will continue to update as we learn more.

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) from HUIT Harvard's Information Technology team has put together this webpage explaining AI and curating resources about initial guidelines, recommendations for prompts, and recommendations of tools with a section specifically on image-based tools.

- Generative AI in Teaching and Learning at the GSD The GSD's evolving policies, information, and guidance for the use of generative AI in teaching and learning at the GSD are detailed here. The policies section includes questions to keep in mind about privacy and copyright, and the section on tools lists AI tools supported at the GSD.

- AI Code of Conduct by MetaLAB A Harvard-affiliated collaborative comprised of faculty and students sets out recommendations for guidelines for the use of AI in courses. The policies set out here are not necessarily adopted by the GSD, but they serve as a good framework for your own thinking about academic integrity and the ethical use of AI.

- Prompt Writing Examples for ChatGPT+ Harvard Libraries created this resource for improving results through crafting better prompts.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Using Sources and AI >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 2:01 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

16 Chapter Sixteen: Academic Honesty

Academic Honesty

I would prefer even to fail with honor than win by cheating. —Sophocles

Academic Honesty and Dishonesty

At most educational institutions, “academic honesty” means demonstrating and upholding the highest integrity and honesty in all the academic work that you do. In short, it means doing your own work and not cheating, and not presenting the work of others as your own.

The following are some common forms of academic dishonesty prohibited by most academic institutions:

Cheating can take the form of crib notes, looking over someone’s shoulder during an exam, or any forbidden sharing of information between students regarding an exam or exercise. Many elaborate methods of cheating have been developed over the years—from hiding notes in the bathroom toilet tank to storing information in graphing calculators, pagers, cell phones, and other electronic devices. Cheating differs from most other forms of academic dishonesty, in that people can engage in it without benefiting themselves academically at all. For example, a student who illicitly telegraphed answers to a friend during a test would be cheating, even though the student’s own work is in no way affected.

Deception is providing false information to an instructor concerning an academic assignment. Examples of this include taking more time on a take-home test than is allowed, giving a dishonest excuse when asking for a deadline extension, or falsely claiming to have submitted work.

Fabrication

Fabrication is the falsification of data, information, or citations in an academic assignment. This includes making up citations to back up arguments or inventing quotations. Fabrication is most common in the natural sciences, where students sometimes falsify data to make experiments “work” or false claims are made about the research performed.

Plagiarism, as defined in the 1995 Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary, is the “use or close imitation of the language and thoughts of another author and the representation of them as one’s own original work.” [1]