Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Chief Complaint : Infertility

Background: Ms. L.C. is a 34 year old female presenting with concerns of infertility. She has been attempting a pregnancy over the past 16 months with no success. Patient reports that several times she thought she could be pregnant due to a cessation in her menses with accompanying constipation and some abdominal pain. Patient also reports pain that is more intense during menstruation, with “sharp and stabbing” characteristics that is not relieved by use of NSAIDs or hot compresses. The pain radiates from her lower abdominal area into her flanks, which she rates to be a 6 on a scale of 1-10. Patient reports her cycle can be irregular, with the length ranging up to 25-38 days or occasionally no period at all. She is concerned that her and her husband have not had enough intercourse for a pregnancy due to dyspareunia and general pelvic pain.

Figure 1. Photograph of Doctor and Patient (2014)

Past Medical History

- Menarche, age 10

- IUD in place, 26 to 32 years

- Pelvic mass, ruled to be non-cancerous, 30 years

- Most recent sexually transmitted infection (STI) screen negative for chlamydia, syphilis, and gonorrhea, 33 years

- Patient does not take any medications

- Patient has no history of pregnancy

Pertinent Family History

- Mother alive and healthy at 58 years of age

- Maternal grandmother passed from ovarian cancer at 42 years

- Sister, 28, also struggles with infertility

Pertinent Social History

- Patient reports stress and a decrease in sexual fulfillment from infertility concerns.

- Patient is monogamous with her primary partner.

- Patient does not drink alcohol or use recreational drugs.

- Patient follows a vegetarian diet and avoids dairy.

- Patient works as an architect for a small firm in Columbus, and occasionally travels domestically for work.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Pathophysiology,...

Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis

- Related content

- Peer review

- Andrew W Horne , professor of gynaecology and reproductive sciences 1 ,

- Stacey A Missmer , professor of obstetrics, gynaecology, and reproductive biology , adjunct professor of epidemiology 2 3

- 1 EXPPECT Edinburgh and MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

- 2 Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

- 3 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

- Correspondence to: A W Horne andrew.horne{at}ed.ac.uk

Endometriosis affects approximately 190 million women and people assigned female at birth worldwide. It is a chronic, inflammatory, gynecologic disease marked by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which in many patients is associated with debilitating painful symptoms. Patients with endometriosis are also at greater risk of infertility, emergence of fatigue, multisite pain, and other comorbidities. Thus, endometriosis is best understood as a condition with variable presentation and effects at multiple life stages. A long diagnostic delay after symptom onset is common, and persistence and recurrence of symptoms despite treatment is common. This review discusses the potential genetic, hormonal, and immunologic factors that lead to endometriosis, with a focus on current diagnostic and management strategies for gynecologists, general practitioners, and clinicians specializing in conditions for which patients with endometriosis are at higher risk. It examines evidence supporting the different surgical, pharmacologic, and non-pharmacologic approaches to treating patients with endometriosis and presents an easy to adopt step-by-step management strategy. As endometriosis is a multisystem disease, patients with the condition should ideally be offered a personalized, multimodal, interdisciplinary treatment approach. A priority for future discovery is determining clinically informative sub-classifications of endometriosis that predict prognosis and enhance treatment prioritization.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, inflammatory, gynecologic disease marked by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which affects approximately 10% of women during their reproductive years—190 million women worldwide. 1 In many patients, it is associated with chronic painful symptoms and other comorbidities, including infertility. 2 The health burden of endometriosis includes chronic pain and significant lifetime costs of $27 855 per year per patient, 3 accumulating to annual healthcare costs for endometriosis of approximately $22bn in the US alone and £12.5bn in the UK in treatment, work loss, and healthcare costs. 4 Although more than 50% of adults diagnosed as having endometriosis report onset of severe pelvic pain during adolescence, 5 most young women with endometriosis do not receive timely treatment. Almost 60% of women will see three or more clinicians before a diagnosis of endometriosis is made after an average of seven years with symptoms. 6 Women with endometriosis lose on average 11 hours of work per week, similar to other chronic conditions including type 2 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. 7 Adolescents are at risk of having inadequately remediated symptoms during prime years for social development and life planning, 8 and women must be resilient against inadequately remediated symptoms and emerging comorbidities. Women, healthcare providers, and scientists would benefit from conceptualizing endometriosis as a condition that can affect the whole woman. This includes a better understanding of the risk of subsequent development of autoimmune disease, cancer, and cardiovascular disease and a whole health approach to monitoring and wellbeing. 9

This review is aimed at general practitioners and pediatric specialists who are most likely to interact with patients as signs and symptoms of endometriosis first emerge and from whom early attention and empiric treatment may dramatically shorten the burden; gynecology specialists for whom myths must be dispelled and who must be aware of state of the art knowledge about patient centered treatments; endometriosis specialists who care for women’s endometriosis associated symptoms across the life course; and clinical researchers and scientists who must be inspired to bring their expertise and creativity to answer the fundamental enigmas of endometriosis etiology, informative sub-phenotyping, and novel patient centered treatment.

In this review, we use the terms “woman” and “women.” However, it is important to note that endometriosis can affect all people assigned female at birth.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched PubMed for studies using the term “endometriosis.” We considered all peer reviewed studies published in the English language between 1 January 2010 and 28 February 2022. We also identified references from international guidelines on endometriosis published during this time period. We selected relevant publications outside this timeline on the basis of review of the bibliography. We predefined the priority of study selection for this review according to the level of the evidence (meta-analyses, systematic or scoping reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective cohort studies, case-control studies, cross sectional studies; a priori exclusion of case series and case reports), by sample size (we prioritized studies with larger sample size as well as studies providing precision statistics), by population sampling (we prioritized studies with more diverse populations or with declared sub-population design over narrow population samples), and publication date (we prioritized more recent studies).

Overall quality of evidence

Much of the knowledge on endometriosis is based on concepts in early stages of evidence development or on sparse literature. Many studies include single hospital or clinic population samples with small total sample sizes and disproportionately representing patients presenting with infertility compared with endometriosis associated pain. 10

Beyond the limitations of the existing literature, fundamental problems with the diagnosis of endometriosis must be overcome before we can adequately define endometriosis, its prevalence, biologically and clinically informative sub-phenotypes, and its response to treatment and long term prognosis. 11 The lack of a non-invasive diagnostic modality creates insurmountable diagnostic biases driven by characteristics of those patients who can and those who cannot access a definitive surgical or imaging diagnosis and at what point in their endometriosis journey the condition is diagnosed.

Ovarian endometrioma or deep endometriosis can be diagnosed through imaging if the patient is geographically, economically, and socially able to achieve referral to and evaluation from an experienced imaging specialist. 12 13 For women with superficial peritoneal disease, definitive diagnosis by means of surgical evaluation is limited to those with symptoms deemed sufficiently severe and life affecting and resistant to empiric treatment to justify the inherent risks of surgery. Even among patients with symptoms deemed to have enough of an effect to warrant referral for a surgical evaluation, stigma, 14 disbelief and misperceptions of pain or fertility that can be driven by racism or elitism, 15 and geographic and economic barriers to accessing endometriosis focused surgeons remain.

Beyond access to an appropriate, skilled physician, the wide range of symptoms associated with endometriosis—many of which are stigmatized or normalized 14 16 —reduces the likelihood of referral and increases time to referral to appropriate specialists. 5 6 11 17 The bias in diagnosis itself may be influenced by variations in clinical symptoms among different populations not adequately captured or appreciated by standard clinical definitions or may represent implicit bias in healthcare, leading to an alternate interpretation of the same symptoms affecting the likelihood of diagnosis. This delay to diagnosis affects patients directly, but it also results in most scientific studies capturing patients’ characteristics, biologic samples, and biomarker measurements far into the natural pathophysiologic progression of the disease. Moreover, studies from African and Asian countries are considerably under-represented compared with European and North American countries. 10 High quality studies from these regions and development of a sensitive non-invasive diagnostic tool might alter existing global prevalence and incidence estimates and may reveal a more comprehensive view of what early milieu, signs and symptoms, and long term health outcomes are truly attributable to endometriosis.

Definition, symptoms, and classification

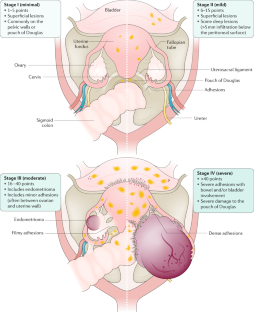

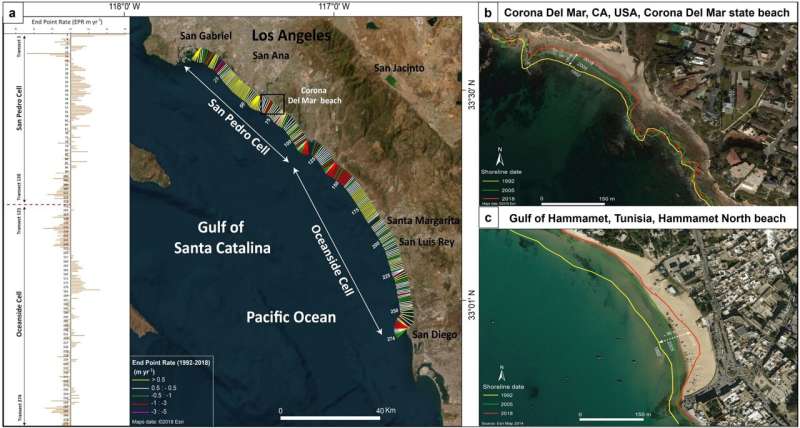

Among women with the condition, endometriosis has a highly heterogeneous presentation of visualized endometriotic lesions, multisystem symptom presentation, and comorbid conditions ( fig 1 ).

Highly varied presentation of endometriosis

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Surgically visualized macro sub-phenotypes of endometriosis

Endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrium-like epithelium and/or stroma (lesions) outside the endometrium and myometrium, usually with an associated inflammatory process. 18 Most endometriosis is found within the abdominal cavity, and it exists as three subtypes: superficial peritoneal endometriosis (accounting for around 80% of endometriosis), ovarian endometriosis (cysts or “endometrioma”), and deep endometriosis 1 19 ( box 1 ; fig 2 ). All forms of endometriosis can be found together, not solely as separate entities. Although not a subtype, endometriosis situated inside the bowel wall is termed “bowel endometriosis.” It mostly affects the rectosigmoid area, but lesions can also be found in other parts of the gastrointestinal system, including the appendix. Endometriosis involving the detrusor muscle and/or the bladder epithelium is termed “bladder endometriosis.” Extra-abdominal (replacing the older term “extra-pelvic”) endometriosis is used to describe any endometriosis lesions found outside of the abdomen (for example, thoracic endometriosis). 20 Iatrogenic endometriosis describes endometriosis thought to be arising from direct or indirect dissemination of endometrium following surgery (for example, cesarean scar endometriosis).

Nomenclature 18

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis.

Endometrium-like tissue lesions involving the peritoneal surface with multiple appearances

Ovarian endometriosis

Endometrium-like tissue lesions in the form of ovarian cysts containing endometrium-like tissue and dark blood stained fluid (endometrioma or “chocolate cysts”)

Deep endometriosis

Endometrium-like tissue lesions extending on or infiltrating the peritoneal surface (usually nodular, invading into adjacent structures, and associated with fibrosis)

Extra-abdominal endometriosis

Endometrium-like tissue outside the abdominal cavity (for example, thoracic, umbilical, brain endometriosis)

Iatrogenic endometriosis

Direct or indirect dissemination of endometrium following surgery (for example, cesarean scar endometriosis)

Surgical images of endometriosis sub-phenotypes

Adenomyosis is not a sub-phenotype of endometriosis, 21 although it is characterized by endometrial tissue surrounded by smooth muscle cells within the myometrium. 22 Symptoms include dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual and/or abnormal uterine bleeding, 23 and a heterogeneous adenomyosis presentation is visualized with radiologic imaging or at hysterectomy that lacks an agreed terminology or classification system. 24 25 Evidence is emerging of tissue injury and repair mechanisms mediated by estradiol and inflammation. 25 26

Endometriosis associated symptoms

Endometriosis is often associated with a range of painful symptoms that include chronic pelvic pain (cyclical and non-cyclical), painful periods (dysmenorrhea), painful sex (dyspareunia), and pain on defecation (dyschezia) and urination (dysuria). 1 27 Their severity can range from mild to debilitating. Some women have no symptoms, others have episodic pelvic pain, and still others experience constant pain in multiple body regions. 28 A related observation is that some women transition between these categories, progressing from episodic and localized pain to that which is chronic, complex, and more difficult to treat. Furthermore, women with disease that is anatomically “severe” can have minimal symptoms and women with “minimal” evidence of endometriosis can have severe, life affecting symptoms. 1 19 In common with other chronic pain conditions, women with endometriosis often report experiencing fatigue and depression. Infertility is significantly more common in patients with endometriosis, with a doubling of risk compared with women without endometriosis. 2 Endometriosis is discovered in 30-50% of women who present for assisted reproductive treatment. 29 30

Endometriosis associated or high risk comorbidities

Endometriosis is certainly a multisystem condition, perhaps as a result of common pathogenesis or as a consequence of the chronic endogenous response to the presence of endometriotic lesions. 9 Although pelvic pain is the most common symptom of possible endometriosis, women with endometriosis also have a high risk of co-occurring or evolving multisite pain. 28 Patients with endometriosis have a higher risk of presentation with comorbid chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, 31 32 33 migraines, 34 35 and also rheumatoid arthritis, 33 36 psoriatic arthritis, 37 and osteoarthritis. 36 38 Reports of back, bladder, or bowel pain are prevalent, 16 39 with dyschezia being potentially predictive of endometriosis. 40 Nearly 50% of women with bladder pain syndrome or interstitial cystitis have endometriosis. 41 42 Irritable bowel syndrome is a common co-occurring diagnosis that reinforces the importance of awareness of endometriosis among gastroenterologists. 43 44 45 These conditions may share a common cause, 46 they may arise together owing to shared environmental or genetic factors, and/or the occurrence of comorbid pain conditions could be due to changes in pain perception after repeated sensitization. 47 Research focused on disentangling the overlapping and independent pathways of these frequently co-occurring pain associated conditions is essential. 48 49

Women with endometriosis have a greater risk of presenting with other non-malignant gynecologic diseases, including uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. 50 51 They are also at greater risk of a subsequent diagnosis of malignancies, autoimmune diseases, early natural menopause, and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular conditions. 36 52 53 54 55 56 57 The hypothesized causal mechanisms for endometriosis discussed below are all thought to be enhanced by and/or result in chronic inflammation. Local and systemic chronic inflammation can directly activate afferent nociceptive fibers and promote pelvic pain, 58 although this does not entirely explain the heterogeneity in types and severity of painful symptoms that patients experience. Furthermore, endometriosis induced chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation may also contribute to the endometriosis associated subsequent risk of each of these comorbid conditions. 59 60

Although this multisystem effect reinforces the importance of knowledge of and attention to endometriosis from general practitioners and a myriad specialists for whole healthcare, the most prominent association, and the focus of the greatest volume of comorbidity research, is the elevated risk of ovarian cancer among women with endometriosis. A recent meta-analysis confirmed this association, 53 finding a nearly twofold greater relative risk of ovarian cancer among patients with endometriosis (summary relative risk (SRR) 1.93, 95% confidence interval 1.68 to 2.22; n=24 studies) that was strongest for clear cell (3.44, 2.82 to 4.42; n=5 studies) and endometrioid (2.33, 1.82 to 2.98; n=5 studies) histotypes. However, among these 24 studies, significant evidence existed of both heterogeneity across studies and publication bias (Egger’s and Begg’s P values <0.01). Clinicians need to reinforce that ovarian cancer is rare regardless of women’s endometriosis status 61 : the absolute lifetime risk in the general population is 1.3%, 62 and applying the risk estimate from the meta-analysis (SRR 1.9) gives an absolute lifetime risk for women with endometriosis of 2.5%, which is 1.2% higher than the absolute risk for women without endometriosis and still very low.

We should also recognize that coexisting gynecologic conditions such as adenomyosis and uterine fibroids, 50 as well as associations with endometrial cancer, 53 can be influenced by diagnostic biases and failure to distinguish between diagnoses in women undergoing hysterectomy and those in women with an intact uterus. 11 51 When attempting to infer a causal relation between endometriosis and other conditions, applying rigorous prospective temporality (rather than cross sectional co-occurrence) is particularly important for valid subsequent risk associations. 53 These studies need large study populations with well documented longitudinal data. A large impediment is the lack of routine, harmonized documentation of the characteristics of endometriosis and its absence from international classification of diseases coding. 63 64

Endometriosis classification systems

Several classification, staging, and reporting systems have been developed; 22 systems were published between 1973 and 2021. 65 The three most commonly used systems are the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification (stages I-IV; where stage I is equivalent to “minimal” disease and stage 4 to “severe” disease), the ENZIAN (and newer #ENZIAN) classification, and the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI). 66 67 68 69 Many validation studies and reports on the implementation of the different systems have been published. The rASRM system (scored at surgery on the basis of the extent of visualized superficial peritoneal lesions, endometriomas, and adhesions) has been shown to have poor correlation with pain, 70 fertility outcomes, and prognosis, and the ENZIAN system (which additionally includes deep endometriosis) has been shown to have poor correlation with symptoms and infertility. 71 72 73 The EFI is a well validated clinical tool that predicts pregnancy rates after surgical staging of endometriosis, with ongoing evaluation to determine the predictive importance of the individual parameters included in the scoring algorithm as well as the effect of completeness of surgical treatment on pregnancy prediction. 74 Unfortunately, no international agreement exists on how to describe endometriosis or how to classify it. As most systems show no, or very little, correlation with patients’ symptoms and outcomes, this is further evidence of our lack of understanding of the physiology underlying the symptoms associated with endometriosis.

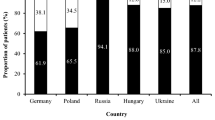

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown given diagnostic delays and barriers, and—perhaps consequently—it is extremely varied depending on the population and the indication for evaluation. A recent meta-analysis identified 69 studies describing the prevalence and/or incidence of endometriosis, among which 26 studies were general population samples, 17 were from regional/national hospitals or insurance claims systems, and the remaining 43 studies were conducted in single clinic or hospital settings. 10 The prevalence reported in general population studies ranged from 0.7% to 8.6%, whereas that reported in single clinic or hospital based studies ranged from 0.2% to 71.4%.

When defined by indications for diagnosis, the prevalence of endometriosis ranged from 15.4% to 71.4% among women with chronic pelvic pain, from 9.0% to 68.0% among women presenting with infertility, and from 3.7% to 43.3% among women undergoing tubal sterilization. Few studies have investigated the incidence and prevalence of endometriosis specifically among adolescents. The reported prevalence of visually confirmed endometriosis among adolescents with pelvic pain ranges from 25% to 100%, with an average of 49% among adolescents with chronic pelvic pain and 75% among those unresponsive to medical treatment. 75 The Ghiasi meta-analysis reported a decrease in recorded prevalence across the past 30 years. 10 Speculating, this may be due to more rapid and more ubiquitous embracing of empiric treatment of symptom, forgoing or delaying definitive imaging or surgical diagnosis, a patient centered approach that has been ratified by the most recent European endometriosis guideline. 13 This hypothesis is supported by a recent report from a large US health system’s electronic medical records database that observed a decline from 2006 through 2015 in incidence rates for endometriosis (from 30.2 per 10 000 person years in 2006 to 17.4 per 10 000 person years in 2015) but an increase in documentation of chronic pelvic pain diagnoses (from 3.0% to 5.6%). 76

Pathophysiology

Heritability and genetics.

Estimates from twin studies suggest 47-51% total heritability of endometriosis, with 26% estimated to be from genetic variation. 77 78 79 To date, nine genome-wide association studies have been reported. 59 The largest study so far, using 17 045 cases and 191 596 controls, has identified 19 single nucleotide polymorphisms, most of which were more strongly associated with rASRM stage III/IV, rather than stage I/II, explaining 1.75% of risk for endometriosis. 80 Consistent with other complex diseases with multifactorial origins, no high penetrance susceptibility genes for endometriosis have yet been identified. 62 The loci discovered to date are almost all located in intergenic regions that are known to play a role in the regulation of expression of target genes yet to be identified. The critical next steps in genetic discovery are to identify additional genes that reveal novel pathophysiological pathways and also emerge to better define the underpinnings of variation in symptoms (in particular, pain types and infertility and treatment response predictors) and also gene expression correlated with comorbid autoimmune, cancer, and cardiovascular conditions. 62

Reflux of endometrial tissue fragments/cells and protein rich fluid through the fallopian tubes into the pelvis during menstruation is considered the most likely explanation for why endometriotic lesions form within the peritoneal cavity, although this mechanism is not sufficient as nearly all women experience retrograde menstruation. 81 82 Additional postulated origins include celomic metaplasia and lymphatic and vascular metastasis. Scientific avenues exploring contributions of interacting endocrine, immunologic, proinflammatory, and proangiogenic processes are drawing curiosity and expertise from varied disciplines with application of state of the art technologies. 59 Retrograde menstruation of stem cells contributes to the establishment of endometriosis, 83 whereas bone marrow stem cells contribute to the continued growth of endometriosis lesions. 84 85 Bone marrow derived stem cells may be responsible for those cases of endometriosis outside of the abdominal cavity. 86

Studies exploring why lesions develop in some, but not all, women have detected changes in the endometrial tissue as well as in the peritoneal fluid and cells lining the cavity. Eutopic endometrial tissue has a significantly different immune profile in women with endometriosis compared with those without it. 87 However, the extent to which this inflammation is a cause or an effect of endometriosis remains unclear. Aberrant inflammation could have an effect on the development of endometriosis lesions and disease progression in various ways, including immune angiogenesis and immune-endocrine interaction. 59 60 Specifically, some of the proposed pathways include altered production of inflammatory cytokines by immune cells in lesions or by endometrial cells themselves involving decreased immune clearance of abnormal endometrial cells and consequent seeding and development of lesions, increased likelihood of adhesion to mesothelial cells due to pro-invasion inflammatory milieu, inflammation promoted proliferation of endometrial cells, and inflammation promoted reduction in apoptosis of endometrial cells. 88 Analysis of eutopic endometrium from women with endometriosis has identified altered expression of genes implicated in the inflammation/immune response, angiogenesis, and steroid responsiveness (progesterone “resistance”). 89 Shed menstrual tissue contains high concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, proteases, and immune cells, all of which may influence the peritoneal microenvironment after reflux. Stem/progenitor cells have been identified in the endometrium and are thought to survive and implant onto the peritoneum, contributing to lesions. 83 Mesothelial cells line the pelvic peritoneal cavity, and changes in their function in women with endometriosis, including altered morphology and metabolism (switch to aerobic glycolysis) 90 and production of factors that promote immune cell recruitment and angiogenesis are all thought to favor survival and establishment of lesions. 91 Physiological hormonal fluctuations in women induce cyclical episodes of cell proliferation, inflammation, injury, and repair within lesions that favor fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation and fibrosis.

Mechanisms of endometriosis associated pain

The development of a new blood supply and associated nerves (neuroangiogenesis) is considered key to the establishment of endometriotic lesions and the activation of peripheral pain pathways ( fig 3 ). 92 Sensory C, sensory Ad, cholinergic, and adrenergic nerve fibers have all been detected in lesions. Estrogens can promote crosstalk between immune cells and nerves within lesions, increasing expression of nociceptive ion channels such as the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1. 93 Factors that promote inflammation and nerve growth, such as nerve growth factor, tumor necrosis factor α, and interleukin 1-β, are increased in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis and may exacerbate a neuroinflammatory cascade. Consistent with other conditions associated with chronic pain, endometriosis is associated with unique, and sometimes disease specific, alterations in the peripheral and central nervous systems, including changes in the volume of regions of the brain and in brain biochemistry. 94 Increased risk of central sensitization may partially explain why approximately 30% of patients with endometriosis will develop chronic pelvic pain that is unresponsive to conventional treatments, including surgery. 95 Through this central process, patients can experience reduced pain thresholds, increased responsiveness and length of aftereffects to noxious stimuli, and expansion of the receptive field so that input from non-injured tissue may elicit pain. 46 47 Among endometriosis patients with central sensitization, the removal of the endometriotic lesions is unlikely to result in adequate pain remediation owing to continued activation of the central nervous system. 96 97 Thus, endometriosis associated pain does not neatly fall into one of the three main categories of chronic pain (that is, nociceptive, neuropathic, or nociplastic), 98 99 100 and it likely has a mixed pain phenotype or sits somewhere along a continuum of these pain phenotypes. For example, some patients have primarily nociceptive or neuropathic pain, others have primarily nociplastic pain, and the rest have a mixed phenotype with variable contributions of nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain.

Pathophysiology of endometriosis: (1) potential factors contributing to endometriosis associated pain; (2) potential mechanisms of endometriosis associated infertility; (3) local factors involved in the development of an endometriosis lesion; (4) role of the eutopic endometrium in the development of an endometriosis lesion. CNS=central nervous system; PNS=peripheral nervous system

Mechanisms of endometriosis associated infertility

Endometriosis may impair fertility through multiple pathways, including peritoneal inflammation and endocrine derangements, which interfere with the follicular environment and consequently affect ovarian function and ultimately reduce oocyte competence. 101 Several studies of women undergoing in vitro fertilization have documented lower oocyte yield or ovarian reserve among women with endometriosis compared with those with other infertility diagnoses. 102 103 A recent study observed lower oocyte yield among endometrioma affected ovaries but not among the contralateral ovaries that were unaffected by endometriosis compared with unexposed ovaries from women with no evidence of endometriosis. 104 In addition, although unproven, anatomical distortion and adhesions caused by endometriosis, particularly in stage III-IV disease, seem likely to reduce the chance of natural conception.

No way to prevent endometriosis is known. Enhanced awareness, followed by early diagnosis and management, may slow or halt the natural progression of the disease and reduce the long term burden of painful symptoms, including possibly the risk of central sensitization, but no cure exists. Furthermore, the evidence for modifiable risk factors for endometriosis remains unacceptably sparse. 12 Critically needed are large scale longitudinal studies that can quantify modifiable exposures in girls and young women in the pre-diagnostic, and ideally the pre-symptomatic, window that are then explored further in humans, 105 106 107 as well as in experimental models, to determine the physiologic pathways defined by causal effects on the epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome. To date, few risk factors have been robustly replicated in multiple populations, with the most consistently associated with endometriosis including müllerian anomalies, low birth weight and lean body size, early age at menarche, short menstrual cycles, and nulliparity. 1 11 Less research has supported associations with endocrine disrupting toxins including diethystilbestrol. 108

Clinical course

A critical aspect of care for women with endometriosis is that associated symptoms progress and recede over the life course, sometimes in response to treatment and sometimes with age or altered environment in pathways that we do not yet understand ( fig 4 ). For example, pain remediation is often a priority among adolescents, 109 whereas older women may be focused on fertility or on life affecting fatigue. 8 110 Furthermore, a long held belief that endometriosis and its symptoms do not occur in adolescents and end at menopause was erroneous. However, the years of perimenopause can be a time of increased pelvic pain, 111 112 with particular attention needing to be paid to symptom management that may include an unexpected return of pain in those patients for whom a treatment regimen had been successful during premenopause. 113 Clinicians need to focus across the life course on patient centered care, engaging in a dialogue to capture evolving symptomatology but also to collaborate on what symptoms are of most importance to the patient at this life stage. 110 Importantly, all that we believe we know about endometriosis is limited to the characteristics and natural history of those women who successfully obtain a diagnosis. To whatever extent asymptomatic or incidental findings have influenced the diagnostic population or to whatever extent health disparities or biases regarding symptom belief or access to pain or infertility care have limited or skewed those diagnosed, our elucidation of the true signs and symptoms and prognosis of endometriosis will evolve as care and access to it improves. 11

Endometriosis risk, establishment, and multisystem effects encompassing evolution across the life course

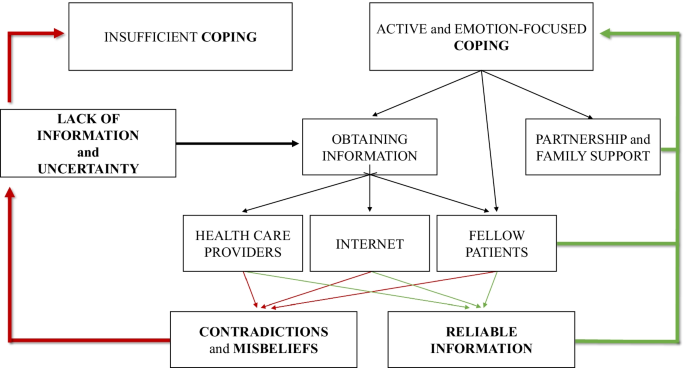

Diagnosis and monitoring

Although endometriosis has a highly variable presentation, steps can be recommended for decision making by general practitioners and gynecologists to approach a “working diagnosis” of probable endometriosis, implement treatment to remediate endometriosis associated symptoms, and consider multi-specialty collaboration for patient centered whole healthcare ( fig 5 ).

Flowchart for a step-by-step approach to patients with suspected endometriosis (adapted from flowcharts in the NICE 114 and ESHRE 13 endometriosis guidelines). *Imaging does not rule out endometriosis; if “negative” imaging but symptoms highly suggestive of endometriosis, consider “working diagnosis” of probable endometriosis. †General practitioners should monitor for emergence of signs of conditions associated with endometriosis and involve/refer to appropriate specialist (eg, gastroenterologist, cardiologist, rheumatologist, psychologist, oncologist). ‡Ideally within accredited specialist endometriosis center

“Red flag” symptoms and signs

The diagnosis of endometriosis should be considered in women (including girls aged 17 and under) presenting with one (or more) of the following symptoms or signs: chronic pelvic pain with or without cyclic flares, dysmenorrhea (affecting daily activities and quality of life), deep dyspareunia, cyclical gastrointestinal symptoms (particularly dyschezia), cyclical urinary symptoms (particularly hematuria or dysuria), or infertility in association with one (or more) of the preceding symptoms or signs. 114 Shoulder tip pain (pain under the shoulder blade), catamenial pneumothorax, cyclical cough/hemoptysis/chest pain, and cyclical scar swelling/pain can indicate endometriosis at extra-abdominal sites. 13 40 115 116 Fatigue is commonly reported by women with endometriosis. An abdomino-pelvic examination may help to identify ovarian and deep disease. 117

Diagnostic biomarkers

Many research studies and Cochrane reviews have assessed potential biomarkers for endometriosis, 118 119 120 with the ultimate goal of reducing the delay that exists in diagnosing endometriosis. Unfortunately, all of the candidates investigated to date have proven non-specific or unreliable, making them inappropriate for routine clinical use.

Imaging to diagnose endometriosis

Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (ideally two dimensional, T2 weighted sequences without fat suppression) can be used to diagnose endometriosis preoperatively, but the absence of findings on imaging does not exclude endometriosis, particularly superficial peritoneal disease. 121 122 Nevertheless, the ENDO Study enrolled 131 women from the general population who had not presented for gynecologic evaluation, among whom magnetic resonance imaging was used to diagnose endometriosis in 11%. 123 Although the sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasonography is maximized only for endometriomas, technological and training advances are improving detection of all sub-phenotypes of endometriotic lesions. 124 125 Saline infusion sonoPODography is a novel technique that may be able to diagnose superficial peritoneal endometriosis on ultrasonography, although it needs to be validated. 126

Laparoscopic diagnosis and appearance of endometriosis

In patients with suspected endometriosis, in whom imaging has shown no obvious pelvic pathology or for whom empirical treatment has been unsuccessful, laparoscopy is recommended for diagnosis. Laparoscopy for endometriosis should always involve a comprehensive exploration of the abdominal and pelvic contents. Histopathological confirmation is ideal; however, histologic definitions for endometriosis have remained stagnant for decades, with a lower than expected sensitivity, 12 particularly among younger women with endometriosis. 127 Superficial peritoneal endometriosis has been described as having a black (powder burn) or dark bluish appearance from the accumulation of blood pigments ( fig 2 ). 128 However, lesions can appear as white opacifications, red flame-like lesions, or yellow-brown patches in earlier, active stages of disease. 129 Ovarian endometriomas have a distinct morphology classically described as a “chocolate cysts,” containing old menstrual blood, necrotic fluid, and other poorly defined components that give their contents a dark brown appearance. Adhesions are often found in association with endometriomas and consist of fibrous scar tissue resulting from chronic inflammation. In many cases, endometriosis is present at the site of ovarian fixation. 130 Deep endometriosis appears as multifocal nodules and may infiltrate the surrounding viscera and peritoneal tissue. 131 Almost 40% of laparoscopies done for pelvic pain do not identify any pathology. 99 Clinicians should always consider other pelvic and non-pelvic visceral and somatic structures, as well as centrally mediated pain factors, that could be generating or contributing to the pain. 99

“Working diagnosis” of probable endometriosis

In women with a high suspicion of endometriosis, in whom imaging has not shown obvious pelvic pathology and a laparoscopy has not been done or is awaited, giving a “working diagnosis” of probable endometriosis and instigating early medical treatment without waiting for a more definitive diagnosis can be helpful. 13 114 132 133 This is an emerging concept for which some people use the terms “working” and “clinical” diagnosis interchangeably.

Delayed diagnosis

Endometriosis can occur at any age, with some patients reporting that pelvic pain symptoms arose at or soon after thelarche or menarche. Among women with endometriosis diagnosed in adulthood, nearly a fifth report that their symptoms began before age 20 and two thirds report onset before age 30. 5 The exact time of disease onset is unknown for endometriosis, as symptoms must emerge and be sufficiently life affecting to gain referral for definitive diagnosis. Furthermore, non-specific symptoms such as dysmenorrhea have often been treated with hormonal drugs without consideration of endometriosis, whereas the current recommendation is to be aware and consider a working diagnosis of probable endometriosis. Thus, varied non-specific symptomatology, normalization of pelvic pain, clinicians’ awareness of endometriosis, and economic and geographic access to care all contribute to a delay averaging seven years from symptom onset to surgical diagnosis. 1 5

Long term monitoring of endometriosis

Follow-up, including psychological support, should be considered in women with confirmed endometriosis, with renewed evaluation and a revised treatment plan if symptoms emerge, recur, or worsen over time. However, no evidence exists of benefit of regular long term monitoring (for example, imaging) for early detection of endometriotic lesion recurrence, complications, or malignant transformation, in the absence of complex ovarian masses or endometriosis with deep bowel effect. 134 135 Given growing evidence of risk of multisystem involving conditions ( fig 4 ), patient centered whole healthcare dictates that monitoring by general practitioners for emergence of signs and symptoms of mental health conditions, cardiovascular disease, immunologic and autoimmune disorders, gastrointestinal conditions, or multifocal pain conditions should be heightened and referral to a non-gynecologic specialist should be considered as needed.

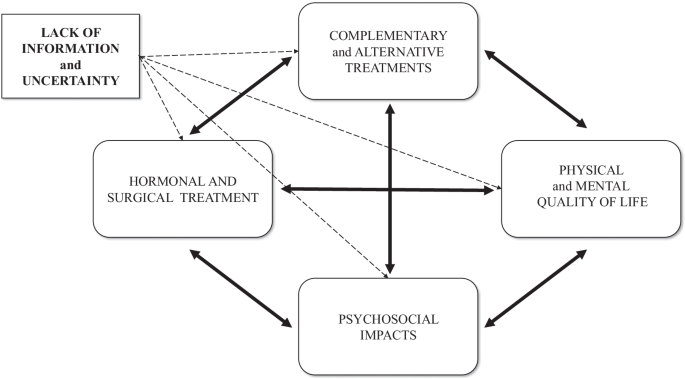

Management of endometriosis associated pain

The growing recognition that endometriosis associated pain has a mixed pain phenotype (or occupies different points on a continuum) supports a personalized, multimodal, interdisciplinary treatment approach, 13 which might include surgical ablation/excision of lesions, analgesics, hormonal treatments, non-hormonal treatments including neuromodulators, and non-drug therapies (or a combination of the above). 1 The evidence supporting different surgical, pharmacologic, and non-pharmacologic approaches to treating endometriosis is examined below.

Surgical management of endometriosis associated pain

The most recent guidelines for endometriosis (for example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), ESHRE) recommend surgery as a treatment option to reduce endometriosis associated pain. 13 114 However, only a limited number of RCTs have assessed pain outcomes after surgery (and most are small, offer little detail on endometriosis sub-phenotypes visualized at surgery, and have a follow-up period of less than 12 months). Furthermore, the authors of the most recent Cochrane review of surgery for endometriosis associated pain concluded that they were “uncertain of the effect of laparoscopic surgery on pain and quality of life” owing to the low quality of the available studies. 136 They included only two of the published RCTs (comparing surgical treatment of endometriosis with diagnostic laparoscopy alone) in their analysis of laparoscopic excision to improve pain and quality of life. 137 138 One trial of 16 participants experiencing pain associated with endometriosis assessed “overall pain” scores at 12 months (mean difference on 0-100 visual analog scale (VAS) 1.65, 95% confidence interval 1.11 to 2.19), and the other trial of 39 participants assessed quality of life at six months measured using the EuroQol-5D (mean difference 0.03, –0.12 to 0.18). The evidence of benefit for specific subtypes is discussed in more detail below.

Surgery for superficial peritoneal endometriosis

Little evidence shows that surgery to treat isolated superficial peritoneal endometriosis improves overall symptoms and quality of life. The uncertainty around surgical management of this subtype is compounded by the limited evidence to allow an informed selection of specific surgical modalities to remove the lesions (for example, laparoscopic ablation versus laparoscopic excision). 139 140

Surgery for ovarian endometriosis

To our knowledge, no RCTs have compared cystectomy versus no treatment in women with endometrioma and measured the effect on painful symptoms. Also, no published data indicate a threshold cyst size below which surgery may be safely withheld in the absence of suspicious features on imaging (surgery is the only means by which a tissue specimen can be obtained to rule out ovarian malignancy). Thus, surgical excision is generally considered the optimal treatment for ovarian endometriosis. Cystectomy, instead of drainage and coagulation, is the preferred surgical approach as it reduces recurrence of endometrioma and endometriosis associated pain. 141 Cystectomy should be chosen with caution for women who desire fertility, as a risk of fertility affecting diminished ovarian reserve exists, and a highly skilled conservative approach should be applied to minimize ovarian damage. 142

Surgery for deep endometriosis

Surgical treatment to completely excise deep disease is generally considered to be the treatment of choice. 143 144 Nevertheless, most of the studies that have reported improvements in quality of life following surgical excision of deep endometriosis (typically involving the bowel) have been done in small cohorts of women, usually from single centers, without a comparator arm, and this affects the precision and generalizability of the results. The largest multicenter prospective non-randomized study published to date reported the six, 12, and 24 month follow-up outcomes on nearly 5000 women undergoing laparoscopic excision of deep rectovaginal endometriosis. 143 This showed clinically and statistically significant reductions in premenstrual, menstrual, and non-cyclical pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dyschezia, low back pain, and bladder pain at 24 months (data from 524-560 participants for each symptom) with a corresponding improvement in quality of life (575 participants, median score on EuroQol-5D 76, 95% confidence interval 75 to 80). Although the results should be interpreted with caution, because data were missing for >70% of patients at 24 months, assigned score methods suggest that evidence of improvement remained statistically significant.

Hysterectomy for endometriosis

No RCTs on hysterectomy for the treatment of endometriosis associated pain have been done. Most published articles are retrospective case series, and only a few prospective studies have been reported. Hysterectomy (with or without oophorectomy) with removal of all visible endometriosis lesions should be reserved for women who no longer wish to conceive and who have not responded to more conservative management. Women with endometriosis should be informed that hysterectomy is not a “cure” for endometriosis and that it is best reserved for women with coexisting adenomyosis (which does occur inside the uterus) or for women with severe pain who have exhausted all other options to improve their symptoms. 145 Recent longitudinal studies have not found a benefit of bilateral oophorectomy for long term pain management. 145 146 Of note, BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of color) women are more likely to have complications of hysterectomy, in part because they are more likely to undergo laparotomy rather than minimally invasive laparoscopy. 147 Women should be informed that hysterectomy is associated with long term morbidity, 148 including cardiovascular disease, 56 among those with and without surgically induced menopause. 149 150

Recurrence or progression of endometriosis after surgery

The reported recurrence rate of painful symptoms attributed to endometriosis is high, estimated as 21.5% at two years and 40-50% at five years. 146 151 However, although a purist’s definition of “endometriosis recurrence” calls for “second look” laparoscopy, it is most often diagnosed in the real world on the basis of recurrence of symptoms alone. In addition, no robust evidence exists to support an ordered progression of endometriotic lesions. In prospective studies of repeat surgeries, lesions progressed (in 29% of cases), regressed (in 42%), or were static (in 29%). 152 Surgical treatment of certain subtypes of endometriosis could also exacerbate painful symptoms. 153 154

Preoperative and postoperative hormone treatment

Preoperative hormone treatment has not been shown to improve the immediate outcome of surgery for pain, or reduce recurrence, in women with endometriosis. 155 A meta-analysis of 340 participants found that compared with surgery alone, postoperative hormone treatment of endometriosis reduced pelvic pain after 12 months (standardized mean difference on VAS −0.79, −1.02 to −0.56), but the evidence is very low quality. 155 Women with endometriosis who undergo hysterectomy with oophorectomy should be advised to start continuous combined hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for at least the first few years after surgery. 156 This may be changed later to estrogen alone, but this needs to be balanced with the theoretical risk of reactivation and malignant transformation of any residual endometriosis, which can occur many years later.

Pharmacologic management of endometriosis associated pain

Most women with suspected or known endometriosis use over-the-counter drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, the available evidence to support their use is scarce. The data on the benefit of NSAIDs are limited to one small RCT. 157 They can be useful as “breakthrough medication” in the management of a pain flare.

Hormonal treatments

Hormone treatments for endometriosis include combined contraceptives, progestogens, gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, GnRH antagonists, and aromatase inhibitors ( table 1 ). All of these hormone treatments (except the newer GnRH antagonists, which have not been so extensively studied) have been included in a multivariate network meta-analysis of the outcomes “menstrual pain” and “non-menstrual pelvic pain” (pain relief on VAS; total of 1680 participants). 114 All treatments led to a clinically significant reduction in pain on the VAS compared with placebo. The magnitude of this treatment effect is similar for all treatments, suggesting that little difference exists between them in their capacity to reduce pain. Furthermore, symptoms return after cessation of treatment and hormone treatments used to manage endometriosis all have side effects. In addition, although the contraceptive properties of the hormones may be welcome if the woman does not wish to become pregnant, they may be unwanted if fertility is desired.

Hormone treatments

- View inline

Non-hormonal treatments

Analgesic tricyclic antidepressants (for example, amitriptyline, nortriptyline), selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (for example, duloxetine) and anticonvulsants (for example, gabapentin and pregabalin) are sometimes used clinically in the treatment of endometriosis associated pain without a strong evidence base. 167 These “neuromodulatory drugs” differ from conventional analgesics, such as NSAIDs, in that they primarily affect the central nervous system’s modulation of pain rather than peripheral mediators of inflammation. However, in a recent RCT for the management of chronic pelvic pain (in the absence of endometriosis), gabapentin was not shown to be superior to placebo and was associated with dose limiting side effects. 168

Non-drug management of endometriosis associated pain

Pelvic physiotherapy.

An increasing number of women with endometriosis report anecdotal benefit from pelvic physiotherapy. Physiotherapists may support women with activity management (for example, exercises, pacing strategies, and goal setting) and/or use complementary approaches to manage their pelvic pain symptoms (for example, massage and trigger point release therapy). Establishing the independent benefit of standalone physiotherapy is difficult, because most studies have assessed it in combination with psychological and medical management. 169 Two small pilot studies assessed the outcome of manipulations and massage for relief of endometriosis associated pain specifically, but they included specific patient groups and need expansion and replication to support recommendations for care of endometriosis patients. 170 171

The most common psychologically based intervention for chronic pain is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Most of the studies of CBT in women with endometriosis are of low quality, designed using different methods and based on different psychological frameworks (making separation of effects difficult). However, given that CBT has been evaluated across a spectrum of other chronic pain disorders and shown to be effective for developing pain coping strategies, 98 99 172 it should be integrated into individualized treatment plans when needed.

Dietary intervention

Diet has been postulated to affect symptoms of endometriosis. However, very few studies (all of limited quality) have evaluated the benefit of dietary interventions and their effect on endometriosis symptoms. Supplements, such as omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (O-PUFAs), have been investigated as a way of reducing inflammation and pain in endometriosis. 173 174 In a recent review, decreased pain scores were observed in women with endometriosis after use of O-PUFAs, which were not seen in controls. 175 Clinicians should be aware that women with endometriosis have an increased risk of co-presenting with irritable bowel syndrome concomitant with endometriosis associated dyschezia. 44 Patients are not uncommonly referred for gastroenterology evaluation without consideration of potential endometriosis. 45

Treatment of endometriosis associated infertility

Hormonal/medical therapies.

No evidence exists of benefit of suppression of ovarian function in women with endometriosis associated infertility who wish to conceive. 176 Following surgery for endometriosis, women seeking pregnancy should not be treated with postoperative hormone suppression with the sole purpose of enhancing future pregnancy rates.

Surgery to increase chance of natural pregnancy

Moderate quality evidence from a Cochrane meta-analysis of three RCTs in a total of 528 participants shows that laparoscopic treatment (ablation or excision) of superficial peritoneal endometriosis increases viable intrauterine pregnancy rates compared with diagnostic laparoscopy only (odds ratio 1.89, 95% confidence interval 1.25 to 2.86). 136 We found no data on live birth rates, and the effect on ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage rates is unclear. No published RCTs have assessed fertility outcomes after surgery for ovarian or deep disease, and surgery is generally recommended only in the presence of painful symptoms. 13 Use of the Endometriosis Fertility Index to support decision making for the most appropriate option to achieve pregnancy after surgery (for example, women who may benefit from medically assisted reproduction) has been recently suggested. 13 68

Medically assisted reproduction

Low quality evidence shows that viable intrauterine pregnancy rates are increased in women with superficial peritoneal endometriosis if they undergo intrauterine insemination with ovarian stimulation, instead of expectant management or intrauterine insemination alone. In one RCT of 103 participants randomized either to ovarian stimulation with gonadotrophins and intrauterine insemination treatment or to expectant management, the live birth rate was 5.6 (95% confidence interval 1.18 to 17.4) times higher in the treated couples. 177 In women with ovarian or deep endometriosis, the benefit of ovarian stimulation with intrauterine insemination is unclear. No RCTs have evaluated the efficacy of assisted reproductive technology (ART) versus no intervention in women with endometriosis. Recommendations in guidelines suggesting that ART may be effective for endometriosis associated infertility have been based on meta-analyses of observational studies comparing the outcomes of ART in women with and without endometriosis. 13 178 179 Doing surgery before ART for infertility associated with superficial peritoneal endometriosis is not recommended, as the evidence suggesting benefit is based on a single retrospective study of low quality 180 (and is not supported by indirect evidence from multiple studies comparing outcomes in women with surgically treated endometriosis and those managed without surgery 179 ). Doing surgery for ovarian endometrioma before ART to improve live birth rates is also not recommended. Current evidence shows no benefit, and surgery is likely to have a negative effect on ovarian reserve. 181 182 In addition, no evidence shows that doing surgical excision of deep endometriosis before ART improves reproductive outcomes, and this should be reserved for women with concomitant painful symptoms.

Specialist endometriosis centers

Specialist centers were first formally proposed in 2006, 183 and this model of care has been successfully implemented in the UK and several other European countries such as Denmark, Germany, and France. 184 185 The role of specialist endometriosis centers should be to offer a coordinated, holistic, multidisciplinary, multimodal approach to women with complex symptoms of endometriosis that are experienced and evolve across the life course ( fig 5 ). Although relevant surgical expertise is important, the role of a center is not to focus solely on surgical treatment to eradicate lesions. Thus, a specialist center should offer an integrated service, including gynecologists, colorectal surgeons, urologists, endometriosis specialist nurses, pain medicine specialists, psychologists, physiotherapists, fertility specialists, and imaging experts.

Various national and international organizations have issued guidelines for the assessment and management of endometriosis. We reviewed and compared nine of these guidelines (including the recent 2022 update of the ESHRE guideline). 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 All of the guidelines recommend the combined oral contraceptive pill and progestogens for endometriosis associated pain, but they differ in the recommendations around “second line” medical treatments. All of the guidelines recommend laparoscopic surgery for the management of endometriosis associated pain, although some acknowledge the lack of evidence for surgery in the management of pain associated with superficial peritoneal endometriosis specifically. 13 114 No clear consensus exists regarding surgical treatment for endometriosis associated infertility, especially with regard to the management of an endometrioma before assisted reproduction.

Emerging diagnostic tools and treatments

Most endometriosis research studies to date have been underfunded and on a small scale, and have involved poorly defined populations of women and samples captured from those who receive a diagnosis well along in their endometriosis journey. However, real hope exists of a breakthrough in the development of a biomarker to diagnose endometriosis closer to emergence and earlier in its natural progression, and to predict response to treatment, owing to the establishment of globally harmonized endometriosis protocols for clinical data and human tissue collection. 105 106 107 The biomarker field will also hopefully benefit from new insights being gained from the study of serum microRNAs and metabolomics. 194 195 Preclinical studies of new non-hormonal medical treatments have offered insights by focusing on inflammation, pain, and metabolism as the platform for repurposing of drugs already approved for other conditions. 19 90 196 Increasing evidence also suggests that the “gut-brain axis” could be a novel therapeutic target for pain symptom relief in endometriosis. 197 Microbiomes likely play a role in the gut-brain axis, are associated with the spectrum of symptoms associated with endometriosis, and are an exciting putative therapeutic target. Lastly, although randomized evaluations of surgical interventions for endometriosis have been rare (and some interventions have been adopted without rigorous evaluation), we are witnessing important collaboration between research and surgical communities to conduct large scale, appropriate, and well designed trials (for example, PRE-EMPT ( https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/bctu/trials/womens/pre-empt/index.aspx ), REGAL ( https://w3.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/REGAL/Public/Public/index.cshtml ), ESPriT2 ( https://www.ed.ac.uk/centre-reproductive-health/esprit2 ), and DIAMOND ( https://w3.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/DIAMOND/Public/Public/index.cshtml )). Surgical trials are difficult to undertake successfully and pose practical and methodological challenges. However, the inherent value of a well conducted RCT to predict the outcomes and/or success rates of surgical treatments for endometriosis should not be overlooked.

Endometriosis is a prevalent, often life affecting condition that in most women emerges during adolescence and can evolve to include symptoms and conditions encompassing multiple systems. Endometriosis demands to be known, considered, and tackled by all practitioners—general and specialist—who treat female patients at all stages across the life course. Patient centered whole healthcare requires a dialog between a woman and her healthcare practitioners to monitor symptom remediation, persistence, or recurrence and to prioritize the focus of care—for example, fatigue remediation when sports participation is paramount, fertility when family building is desired, a revision of medical treatment during perimenopause, or early response to signs of cardiovascular changes. Stigma around menstrual health and chronic pain remain all too ubiquitous barriers to high quality healthcare. Awareness in the general public and among healthcare providers is essential.

Once their symptoms are acknowledged and treated, most patients with endometriosis do well. However, despite overcoming diagnostic delays and access to state of the art treatment, some experience persistence or progression of symptoms. Critical next steps for discovery include defining sub-phenotypes of endometriosis that classify patients into groups that are predictive of prognosis and the natural course of the condition and indicate selection of treatments most likely to be successful to restore high quality of life. We must also answer foundational questions that remain about the causes and natural progression of endometriosis that need expanded funding and attraction of multidisciplinary scientists from all areas of population and bench science. Recommendations to permit a “working diagnosis” of probable endometriosis are having an effect on patient centered care and faster symptom remediation. Through the work of endometriosis associations, non-governmental organizations, and the endometriosis community across the globe, awareness of endometriosis has increased in recent years, along with some increases in funding. We are early on the necessary trajectory, but the journey is gaining speed.

Questions for future research

What causes endometriosis?

Can a non-invasive screening tool be developed to aid the diagnosis of endometriosis?

What are the most effective ways of maximizing and/or maintaining fertility in women with confirmed or suspected endometriosis?

What are the most effective ways of managing the emotional, psychological, and/or fatigue related impact of living with endometriosis?

Can we predict the outcomes and/or success rates for surgical or medical treatments for endometriosis?

What are the most effective non-surgical ways of managing endometriosis related pain and/or symptoms?

Adapted from the James Lind Alliance “Top ten research priorities for endometriosis in the UK and Ireland” 198

Patient involvement

We consulted Emma Cox, chief executive of Endometriosis UK, a nationally recognized representative and voice of patients with endometriosis, in the development of this review, and she commented on the draft and final manuscript. No patients were involved directly in the preparation of this article.

Acknowledgments

In addition to invaluable insight provided by Emma Cox, we thank Naoko Sasamoto and Marzieh Ghiasi for early design of figures 1 and 4, which were further adapted by SAM for this review; Kevin Kuan for designing figure 3 in BioRender; and Dan Martin for contributing image 1 to figure 2.

Series explanation: State of the Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason they are written predominantly by US authors

Contributors: AWH and SAM contributed equally to the planning, analysis, and writing of the article. AWH is the guarantor.

Funding: AWH is supported by an MRC Centre Grant (MRC G1002033) and an NIHR Project Grant (NIHR129801).

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: AWH’s institution (University of Edinburgh) has received payment for consultancy and grant funding from Roche Diagnostics to assist in the early development of a possible blood diagnostic biomarker for endometriosis. AWH has received grant funding from the MRC and NIHR for endometriosis research; he is a board member of the World Endometriosis Society and Society for Endometriosis and Uterine Disorders, is co-editor in chief of Reproduction and Fertility , has been a member of the NICE and ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Groups, and is a trustee and medical adviser to Endometriosis UK. SAM has received payment for consultancy and grant funding from AbbVie, LLC, for population based research unrelated to product development and has received grant funding from the US National Institutes of Health, US Department of Defense, and the Marriott Family Foundations for endometriosis research. SAM is a board member of the World Endometriosis Society, World Endometriosis Research Foundation, American Society for Reproductive Medicine Endometriosis Special Interest Group, and the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology Special Interest Group on Endometriosis and Endometrial Disorders; a member of the Interdisciplinary Network on Female Pelvic Health of the Society for Women’s Health Research; and is a statistical advisory board member for Human Reproduction and field chief editor for Frontiers in Reproductive Health .

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Zondervan KT ,

- Becker CM ,

- Prescott J ,

- Farland LV ,

- Tobias DK ,

- Soliman AM ,

- Simoens S ,

- Dunselman G ,

- Dirksen C ,

- Nnoaham KE ,

- Hummelshoj L ,

- Webster P ,

- World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health consortium

- Stratton P ,

- Cleary SD ,

- Ballweg ML ,

- Missmer SA ,

- Agarwal SK ,

- Kulkarni MT ,

- Shafrir AL ,

- Taylor HS ,

- Adamson GD ,

- Diamond MP ,

- Heikinheimo O ,

- ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group

- DiVasta AD ,

- Vitonis AF ,

- Laufer MR ,

- Ballard K ,

- Tomassetti C ,

- Johnson NP ,

- Petrozza J ,

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES

- Saunders PTK ,

- Andres MP ,

- Arcoverde FVL ,

- Souza CCC ,

- Fernandes LFC ,

- Halvorson LM

- Isaacson K ,

- Halvorson LM ,

- Giudice LC ,

- Vannuccini S ,

- Petraglia F ,

- Bourdon M ,

- Santulli P ,

- Jeljeli M ,

- Saunders PTK

- Williams C ,

- Bedaiwy MA ,

- Counsellor VS

- Eskenazi B ,

- Coloma JL ,

- Martínez-Zamora MA ,

- Collado A ,

- Larrosa Pardo F ,

- Bondesson E ,

- Schelin MEC ,

- Palmor MC ,

- Fourquet J ,

- Miller JA ,

- Shigesi N ,

- Kvaskoff M ,

- Kirtley S ,

- Harris HR ,

- Korkes KMN ,

- Costenbader KH ,

- Kennedy SH ,

- Jenkinson C ,

- World Endometriosis Research Foundation Women’s Health Symptom Survey Consortium

- Rodríguez MA ,

- Buchwald DS ,

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Working Group on Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain

- Tirlapur SA ,

- Chaliha C ,

- Chiaffarino F ,

- Cipriani S ,

- Zimmerman LA ,

- Fadayomi AB ,

- Morotti M ,

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM ,

- Liedgens H ,

- IMI-PainCare PROMPT consensus panel

- Nunez-Badinez P ,

- Laux-Biehlmann A ,

- Gallagher CS ,

- Mäkinen N ,

- 23andMe Research Team

- Mahamat-Saleh Y ,

- Thombre Kulkarni M ,

- Shafrir A ,

- Degnan WJ 3rd . ,

- Rich-Edwards J ,

- Spiegelman D ,

- Forman JP ,

- Vincent K ,

- Taylor RN ,

- Symons LK ,

- Miller JE ,

- Rahmioglu N ,

- Morris AP ,

- WERF EPHect Working Group

- Whitaker LHR ,

- Vermeulen N ,

- Einarsson JI ,

- International working group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES

- ↵ Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996 . Fertil Steril 1997 ; 67 : 817 - 21 . doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81391-X pmid: 9130884 OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Tuttlies F ,

- Keckstein J ,

- Saridogan E ,

- Ulrich UA ,

- Schliep KC ,

- Mumford SL ,

- Peterson CM ,

- Shamiyeh A ,

- World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium

- Borrelli GM ,

- Maheux-Lacroix S ,

- Nesbitt-Hawes E ,

- Janssen EB ,

- Rijkers AC ,

- Hoppenbrouwers K ,

- Meuleman C ,

- D’Hooghe TM

- Christ JP ,

- Schulze-Rath R ,

- Grafton J ,

- Treloar SA ,

- O’Connor DT ,

- O’Connor VM ,

- Pettersson HJ ,

- Svedberg P ,

- Nyholt DR ,

- ANZGene Consortium ,

- International Endogene Consortium ,

- Genetic and Environmental Risk for Alzheimer’s disease Consortium

- Sapkota Y ,

- Steinthorsdottir V ,

- iPSYCH-SSI-Broad Group

- Hammond MG ,

- Cousins FL ,

- Figueira PG ,

- Critchley HOD ,

- Babayev E ,

- Gajbhiye R ,

- McKinnon B ,

- Mortlock S ,

- Mueller M ,

- Montgomery G

- Saunders PT ,

- Greaves E ,

- Esnal-Zufiurre A ,

- Mechsner S ,

- Saunders PT

- As-Sanie S ,

- Harris RE ,

- Napadow V ,

- Coccia ME ,

- Rizzello F ,

- Palagiano A ,

- Scarselli G

- Sutton CJ ,

- Whitelaw N ,

- Khachikyan I ,

- Carrillo J ,

- Di Tucci C ,

- Di Feliciantonio M ,

- Senapati S ,

- Sammel MD ,

- Barnhart KT

- Carvalho LFP ,

- Fassbender A ,

- Buck Louis GM

- Gallagher JS ,

- Angioni S ,

- Gemmell LC ,

- Webster KE ,

- VanBuren WM ,

- Kuznetsov L ,

- Dworzynski K ,

- Overton C ,

- Guideline Committee

- Ballard KD ,

- Seaman HE ,

- de Vries CS ,

- Bonsignore L ,

- Samuels S ,

- Vercellini P

- Rouzier R ,

- Thomassin-Naggara I ,

- Nisenblat V ,

- Bossuyt PM ,

- Farquhar C ,

- Johnson N ,

- Moura APC ,

- Ribeiro HSAA ,

- Bernardo WM ,

- Buck Louis GM ,

- Hediger ML ,

- ENDO Study Working Group

- Guerriero S ,

- Condous G ,

- van den Bosch T ,

- Leonardi M ,

- Mestdagh W ,

- Stamatopoulos N ,

- Watkins JC ,

- Mettler L ,

- Schollmeyer T ,

- Lehmann-Willenbrock E ,

- Jansen RP ,

- Koninckx PR ,

- Adamyan L ,

- Wattiez A ,

- Barraclough K ,

- Chapron C ,

- Andreotti RF ,

- Vercellini P ,

- Sergenti G ,

- Frattaruolo MP ,

- Beebeejaun Y ,

- Bosteels J ,

- Jarrell J ,

- Mohindra R ,

- Taenzer P ,

- Daniels J ,

- DeSarno M ,

- Findley J ,

- Maouris P ,

- Shaltout MF ,

- Elsheikhah A ,

- BSGE Endometriosis Centres

- Bendifallah S ,

- Sandström A ,

- Johansson M ,

- Bäckström T ,

- Shakiba K ,

- McGill KM ,

- Orlando MS ,

- Luna Russo MA ,

- Richards EG ,

- Stewart EA ,

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK ,

- Weaver AL ,

- Hans Evers JL

- Schrepf AD ,

- Zakhari A ,

- Delpero E ,

- McKeown S ,

- Tomlinson G ,

- Choudhry AJ ,

- ↵ British Menopause Society. Tools for Clinicians: induced menopause in women with endometriosis. 2019. https://thebms.org.uk/publications/tools-for-clinicians/ .

- Kauppila A ,

- di Tucci C ,

- Achilli C ,

- Benedetti Panici P

- Kettner LO ,

- Lessey BA ,

- Tanimoto M ,

- Kusumoto T ,

- Arjona Ferreira JC ,

- Hewitt CA ,

- GaPP2 collaborative

- Nordling J ,

- Jaszczak P ,

- Deboute O ,

- Zacharopoulou C ,

- Valiani M ,

- Ghasemi N ,

- Bahadoran P ,

- Williams ACC ,

- Eccleston C

- Abokhrais IM ,

- Denison FC ,

- Nodler JL ,

- Collins JJ ,

- Fedorkow DM ,

- Vandekerckhove P

- Tummon IS ,

- Martin JS ,

- Gallos ID ,

- Coomarasamy A

- Opøien HK ,

- Fedorcsak P ,

- Nickkho-Amiry M ,

- Majumder K ,

- Edi-O’sagie E ,

- D’Hooghe T ,

- Hummelshoj L

- van Hanegem N ,

- van Kesteren P ,

- Kalaitzopoulos DR ,

- Samartzis N ,

- Kolovos GN ,

- Dunselman GA ,

- European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- Collinet P ,

- Revel-Delhom C ,

- Buchweitz O ,

- German and Austrian Societies for Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Leyland N ,

- Laberge P ,

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine

- World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium

- Moustafa S ,

- Mamillapalli R ,

- Nematian S ,

- Koscielniak M ,

- Williams L ,

- Salliss ME ,

- Mahnert ND ,

- Herbst-Kralovetz MM

- Endometriosis Priority Setting Partnership Steering Group (appendix)

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Volume 2024, Issue 5, May 2024 (In Progress)

- Volume 2024, Issue 4, April 2024

- Bariatric Surgery

- Breast Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Colorectal Surgery

- Colorectal Surgery, Upper GI Surgery

- Gynaecology

- Hepatobiliary Surgery

- Interventional Radiology

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Otorhinolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Plastic Surgery

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgery

- Upper GI Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Case Reports

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, case report, conflict of interest statement, consent for publication, abdominal wall endometriosis: a case report.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Stefanos K Stefanou, Kostas Tepelenis, Christos K Stefanou, George Gogos-Pappas, Christos Tsalikidis, Konstantinos Vlachos, Abdominal wall endometriosis: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports , Volume 2021, Issue 4, April 2021, rjab055, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab055

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Abdominal wall endometriosis has an incidence of 0.3–1% of extrapelvic disease. Α 48-year-old female appeared in the emergency department with cellulitis in a lower midline incision. She had an endometrioma of the anterior abdominal wall removed 2 years ago. After 5 months, she underwent an open repair of an incisional hernia with a propylene mesh, which was unfortunately infected and removed 1 month later. Finally, in July 2019, she had her incisional hernia repaired with a biological mesh. Imaging modalities revealed a large mass below the umbilicus. Mass was punctured under ultrasound guidance. Cytology reported the recurrence of endometriosis. Pain and abdominal mass associating with menses were the two most typical symptoms. Wide local excision of the mass with at least 1 cm negative margins is the preferred treatment. Surgeons should maintain a high suspicion of the disease in reproductive women with circular pain, palpable abdominal mass and history of uterine-relating surgery.

Endometriosis is a common condition where endometrial cells, both glands and stroma, are found outside the womb [ 1 ]. Most often, endometriosis is located on the ovaries, fallopian tubes and tissue around the uterus and ovaries, whereas the extrapelvic disease is rare [ 2 ]. Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE), the commonest site of extrapelvic disease, has an incidence of 0.03–1% [ 3 ]. Cause is not entirely clear, and several theories have been proposed about its pathogenesis [ 2 , 4 ]. The main symptom is a recurrent cyclic pain associated with menstruation [ 5 ]. Differential diagnosis encompasses hernias, abscesses, lipomas, desmoids tumors and malignancies [ 6 ].

A 48-year-old female patient visited the emergency department due to cellulitis in a lower midline incision. She had a tumor of the anterior abdominal wall removed at 2017, which turned out to be an endometrioma in the histological report. Six months later, she underwent an open repair of an incisional hernia with a polypropylene mesh. The mesh was placed on lay. One month after the surgery, the mesh was removed owing to infection. On July 2019, her incisional hernia was repaired with a biological mesh. From obstetric history, she had a caesarian delivery 18 years ago.

Abdominal examination disclosed a palpable hard mass below the umbilicus. The patient was admitted to the surgical department for observation, and antibiotics were commenced, particularly vancomycin. A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was obtained, which demonstrated a large oval mass 10.7 × 5.7 × 7.8 cm with rim enhancement and dense content, which was located below the umbilicus.