What is Problem Solving? (Steps, Techniques, Examples)

By Status.net Editorial Team on May 7, 2023 — 5 minutes to read

What Is Problem Solving?

Definition and importance.

Problem solving is the process of finding solutions to obstacles or challenges you encounter in your life or work. It is a crucial skill that allows you to tackle complex situations, adapt to changes, and overcome difficulties with ease. Mastering this ability will contribute to both your personal and professional growth, leading to more successful outcomes and better decision-making.

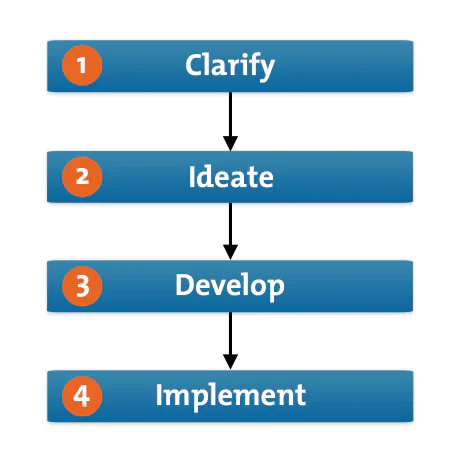

Problem-Solving Steps

The problem-solving process typically includes the following steps:

- Identify the issue : Recognize the problem that needs to be solved.

- Analyze the situation : Examine the issue in depth, gather all relevant information, and consider any limitations or constraints that may be present.

- Generate potential solutions : Brainstorm a list of possible solutions to the issue, without immediately judging or evaluating them.

- Evaluate options : Weigh the pros and cons of each potential solution, considering factors such as feasibility, effectiveness, and potential risks.

- Select the best solution : Choose the option that best addresses the problem and aligns with your objectives.

- Implement the solution : Put the selected solution into action and monitor the results to ensure it resolves the issue.

- Review and learn : Reflect on the problem-solving process, identify any improvements or adjustments that can be made, and apply these learnings to future situations.

Defining the Problem

To start tackling a problem, first, identify and understand it. Analyzing the issue thoroughly helps to clarify its scope and nature. Ask questions to gather information and consider the problem from various angles. Some strategies to define the problem include:

- Brainstorming with others

- Asking the 5 Ws and 1 H (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How)

- Analyzing cause and effect

- Creating a problem statement

Generating Solutions

Once the problem is clearly understood, brainstorm possible solutions. Think creatively and keep an open mind, as well as considering lessons from past experiences. Consider:

- Creating a list of potential ideas to solve the problem

- Grouping and categorizing similar solutions

- Prioritizing potential solutions based on feasibility, cost, and resources required

- Involving others to share diverse opinions and inputs

Evaluating and Selecting Solutions

Evaluate each potential solution, weighing its pros and cons. To facilitate decision-making, use techniques such as:

- SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats)

- Decision-making matrices

- Pros and cons lists

- Risk assessments

After evaluating, choose the most suitable solution based on effectiveness, cost, and time constraints.

Implementing and Monitoring the Solution

Implement the chosen solution and monitor its progress. Key actions include:

- Communicating the solution to relevant parties

- Setting timelines and milestones

- Assigning tasks and responsibilities

- Monitoring the solution and making adjustments as necessary

- Evaluating the effectiveness of the solution after implementation

Utilize feedback from stakeholders and consider potential improvements. Remember that problem-solving is an ongoing process that can always be refined and enhanced.

Problem-Solving Techniques

During each step, you may find it helpful to utilize various problem-solving techniques, such as:

- Brainstorming : A free-flowing, open-minded session where ideas are generated and listed without judgment, to encourage creativity and innovative thinking.

- Root cause analysis : A method that explores the underlying causes of a problem to find the most effective solution rather than addressing superficial symptoms.

- SWOT analysis : A tool used to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to a problem or decision, providing a comprehensive view of the situation.

- Mind mapping : A visual technique that uses diagrams to organize and connect ideas, helping to identify patterns, relationships, and possible solutions.

Brainstorming

When facing a problem, start by conducting a brainstorming session. Gather your team and encourage an open discussion where everyone contributes ideas, no matter how outlandish they may seem. This helps you:

- Generate a diverse range of solutions

- Encourage all team members to participate

- Foster creative thinking

When brainstorming, remember to:

- Reserve judgment until the session is over

- Encourage wild ideas

- Combine and improve upon ideas

Root Cause Analysis

For effective problem-solving, identifying the root cause of the issue at hand is crucial. Try these methods:

- 5 Whys : Ask “why” five times to get to the underlying cause.

- Fishbone Diagram : Create a diagram representing the problem and break it down into categories of potential causes.

- Pareto Analysis : Determine the few most significant causes underlying the majority of problems.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis helps you examine the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats related to your problem. To perform a SWOT analysis:

- List your problem’s strengths, such as relevant resources or strong partnerships.

- Identify its weaknesses, such as knowledge gaps or limited resources.

- Explore opportunities, like trends or new technologies, that could help solve the problem.

- Recognize potential threats, like competition or regulatory barriers.

SWOT analysis aids in understanding the internal and external factors affecting the problem, which can help guide your solution.

Mind Mapping

A mind map is a visual representation of your problem and potential solutions. It enables you to organize information in a structured and intuitive manner. To create a mind map:

- Write the problem in the center of a blank page.

- Draw branches from the central problem to related sub-problems or contributing factors.

- Add more branches to represent potential solutions or further ideas.

Mind mapping allows you to visually see connections between ideas and promotes creativity in problem-solving.

Examples of Problem Solving in Various Contexts

In the business world, you might encounter problems related to finances, operations, or communication. Applying problem-solving skills in these situations could look like:

- Identifying areas of improvement in your company’s financial performance and implementing cost-saving measures

- Resolving internal conflicts among team members by listening and understanding different perspectives, then proposing and negotiating solutions

- Streamlining a process for better productivity by removing redundancies, automating tasks, or re-allocating resources

In educational contexts, problem-solving can be seen in various aspects, such as:

- Addressing a gap in students’ understanding by employing diverse teaching methods to cater to different learning styles

- Developing a strategy for successful time management to balance academic responsibilities and extracurricular activities

- Seeking resources and support to provide equal opportunities for learners with special needs or disabilities

Everyday life is full of challenges that require problem-solving skills. Some examples include:

- Overcoming a personal obstacle, such as improving your fitness level, by establishing achievable goals, measuring progress, and adjusting your approach accordingly

- Navigating a new environment or city by researching your surroundings, asking for directions, or using technology like GPS to guide you

- Dealing with a sudden change, like a change in your work schedule, by assessing the situation, identifying potential impacts, and adapting your plans to accommodate the change.

- How to Resolve Employee Conflict at Work [Steps, Tips, Examples]

- How to Write Inspiring Core Values? 5 Steps with Examples

- 30 Employee Feedback Examples (Positive & Negative)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

Problem-Solving Techniques: A Complete Guide

Problem-Solving Techniques are systematic methods for recognising, evaluating, and resolving issues in an organised way. This blog discusses What are Problem-Solving Techniques, their importance, Basic Problem-Solving Techniques, etc. These skills can enhance your problem-solving skills. Read more to learn further.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Introduction to Management

- Personal & Organisational Development

- Workforce Resource Planning Training

- Supervisor Training

- Introduction to Managing Budgets

According to Indeed , the average salary of a Problem Solver in the UK is £30,000 per year. Further, in this blog, you will learn about the top 15 Problem-Solving Techniques and their importance.

Table of Contents

1) What are Problem-Solving Techniques?

2) The Importance of Problem-Solving Techniques

3) Basic Problem-Solving Techniques

4) Top 20+ Problem-Solving Techniques

5) Conclusion

What are Problem-Solving Techniques?

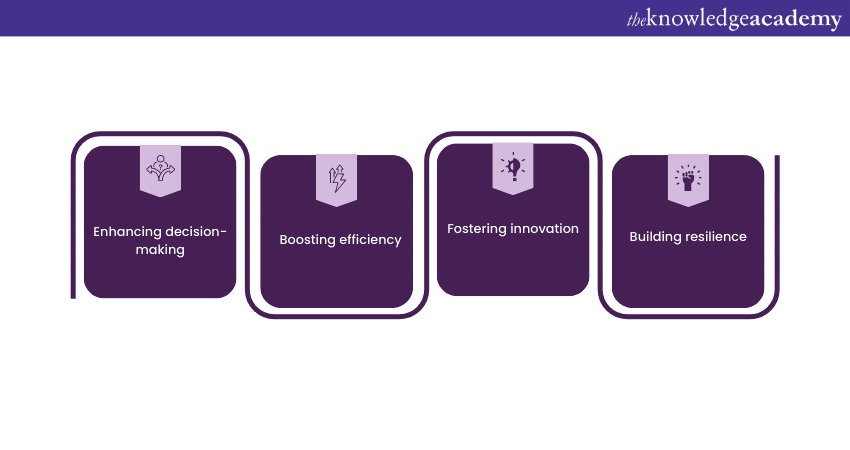

The Importance of Problem-Solving Techniques

1) Enhancing decision-making: Effective Problem-Solving Techniques enhance the decision-making process. When individuals face problems, they are encouraged to explore various solutions and carefully evaluate their potential outcomes.By considering the consequences of each option, individuals can make wise decisions that lead to positive outcomes.

2) Boosting efficiency: In today's fast-paced world, efficiency is paramount.Problem-Solving Techniques enable individuals to address issues promptly and efficiently. By breaking down problems into manageable steps, they can tackle each component with precision, ultimately speeding up the Problem-Solving process.

3) Fostering innovation: Creativity is a driving force behind innovation, and Problem-Solving Techniques stimulate this aspect. When individuals engage in brainstorming sessions and explore unconventional solutions, they open the door to innovative ideas that can revolutionise their approach to Problem-Solving.

4) Building resilience: The ability to bounce back from challenges and setbacks is known as Resilience. Problem-Solving Techniques encourage individuals to view obstacles as opportunities for growth and learning. By approaching issues with a positive mindset, individuals can build resilience and nurture the confidence to tackle any future challenges.

Problem-Solving Techniques are instrumental in empowering individuals to handle various situations effectively. By improving decision-making, boosting efficiency, fostering innovation, and nurturing resilience, these techniques become valuable assets in both personal and professional endeavours.

Unleash your Problem-Solving prowess and conquer challenges with our transformative Problem Solving Training - Sign up now!

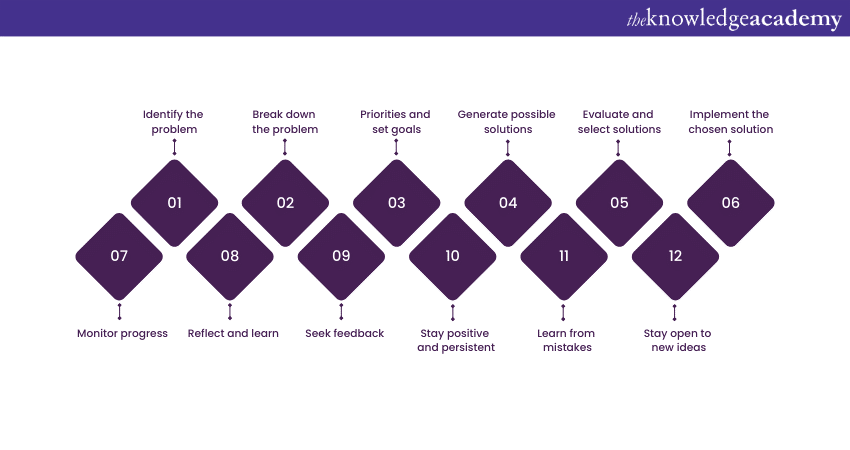

Basic Problem-Solving Techniques

Basic Problem-Solving Techniques are essential tools that individuals can employ to address a wide range of challenges effectively. These techniques serve as a foundation for Problem-Solving and can be applied in various situations. Here are some basic Problem-Solving Techniques:

1) Identify the problem: The first step is to clearly identify the issue at hand. Take time to understand the problem's nature, scope, and impact. Gathering relevant information and data is crucial for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the situation.

2) Break down the problem: Therefore, breaking down the problem into smaller, more manageable parts can make it easier. Analyse the problem's components and consider how they relate to one another.

3) Priorities and set goals: Determine which aspects of the problem are most urgent and require immediate attention. Keep Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART) goals to guide the Problem-Solving process.

4) Generate possible solutions: Brainstorm potential solutions to the problem. Encourage creative thinking and be open to creative ideas. At this stage, the quantity of ideas is more important than their quality. All ideas are considered without judgment.

5) Evaluate and select solutions: After generating a list of potential solutions, evaluate each one based on its feasibility, practicality, and alignment with the established goals. Consider the pros and cons of each option.

6) Implement the chosen solution: Once the most suitable solution is selected, put it into action. Create a clear action plan outlining the necessary steps, responsibilities, and timelines for implementation.

7) Monitor progress: Consistently track the progress of the implemented solution. Assess its effectiveness and whether it is achieving the desired results. If necessary, make adjustments to optimise the outcome.

8) Reflect and learn: After solving the problem, take some time to reflect on the process. Identify what worked well and what could be improved. Learning from past experiences can help enhance Problem-Solving skills for future challenges.

9) Seek feedback: Gather feedback from relevant stakeholders involved in the Problem-Solving process. Feedback can offer valuable insights and different perspectives, leading to more comprehensive solutions.

10) Stay positive and persistent: Though Problem-Solving can be challenging, maintaining a positive attitude and persistence is essential. Some problems may require multiple attempts and iterations before finding the best solution.

11) Learn from mistakes: Mistakes are a natural part of the Problem-Solving process. Embrace them as learning opportunities and use them to improve future approaches.

12) Be open to new ideas: Problem-Solving is not a linear process. Stay open to new information, ideas, and perspectives that may arise throughout the process.

Individuals can incorporate these basic Problem-Solving Techniques into their approach to become more effective in addressing various challenges and making informed decisions. These techniques provide a structured and systematic way to navigate problems, leading to successful outcomes in both personal and professional contexts.

Transform conflict into collaboration and build harmonious workplaces with our Conflict Management Training – Sign up today!

Top 20+ Problem-Solving Techniques

Problem-Solving Techniques are systematic approaches used to identify, analyse, and resolve issues in a structured and effective manner. These techniques are crucial in both personal and professional spheres as they enable individuals to navigate challenges and find practical solutions. Here are the top 20+ Problem-Solving Techniques:

1) Define the problem clearly

Precisely defining the problem is the cornerstone of effective Problem-Solving. It includes finding the root cause of the issue and understanding its scope. Gathering relevant information and data is crucial at this stage to gain a comprehensive understanding of the problem's context. Articulating the problem in simple terms ensures clarity for all involved in the Problem-Solving process. This will make the communication and collaboration easier.

2) Brainstorming solutions

Once the problem is well-defined, the next step is to conduct brainstorming sessions. These sessions aim to generate a diverse range of potential solutions. It's essential to create a supportive and open environment during brainstorming, encouraging participants to think freely and creatively. Sometimes, unconventional ideas that emerge during brainstorming sessions can lead to creative and unique solutions that may not have been considered otherwise.

3) Evaluating and selecting solutions

With a pool of potential solutions, it's time to evaluate each option critically. Consider factors like feasibility, practicality, cost-effectiveness, and alignment with the overarching goals. A well-thought-out evaluation process enables decision-makers to narrow down the list of potential solutions. This approach identifies those solutions that are most viable and likely to address the problem effectively.

4) Implementing the solution

The selected solution now needs to be put into action. Creating a detailed action plan that defines the specific steps, responsibilities, and timelines is essential. Having a well-structured implementation process ensures that everyone involved understands their role and contributes to the successful execution of the solution.

5) Monitoring and evaluating

Implementing the solution is not the end of the Problem-Solving process. Continuous monitoring and evaluation are critical to assess the effectiveness of the solution. Regularly tracking progress and gathering feedback from stakeholders allow for adjustments and improvements as needed. This iterative method ensures that the solution remains relevant and optimised over time.

6) Root Cause Analysis (RCA)

Rather than merely addressing the symptoms of a problem, an RCA seeks to identify the underlying factors that trigger the issue. By targeting the root cause, individuals can develop sustainable solutions that prevent the problem from recurring in the future.

7) SWOT analysis

A SWOT analysis is a valuable tool that helps individuals understand the internal strengths and weaknesses of their organisation or themselves. It also identifies external opportunities and threats in the environment. By identifying these factors, Problem-solvers can develop well-informed strategies that align with their strengths and capitalise on opportunities. At the same time, they address weaknesses and mitigate threats.

8) Decision matrix analysis

When faced with multiple solutions, a decision matrix analysis allows for a structured comparison. This technique involves assigning weights to different criteria and scoring each solution based on those criteria. The solution with the highest score indicates the most viable option.

9) Creative thinking

Encouraging creative thinking during Problem-Solving opens up a world of possibilities. Techniques like mind mapping, brainstorming, and lateral thinking stimulate great ideas and novel approaches to tackle problems creatively.

10) Collaborative Problem-Solving

Involving a diverse group of individuals in the Problem-Solving process brings in a variety of perspectives and expertise. Collaborative Problem-Solving fosters a sense of ownership among team members, promoting active participation and commitment to finding effective solutions.

11) Risk analysis

Assessing potential risks and challenges associated with each solution helps individuals anticipate and prepare for contingencies. Identifying potential obstacles allows for the implementation of risk mitigation strategies to minimise negative outcomes.

12) Learn from past experiences

Reflecting on past Problem-Solving experiences, both successes and failures, provides valuable insights. Learning from these experiences helps improve Problem-Solving skills and approaches over time, making individuals more adept at addressing future challenges.

13) Consider constraints and resources

In the process of Problem-Solving, it's essential to take into account the constraints and available resources. These constraints may include budget limitations, time constraints, or external factors beyond one's control. By understanding and acknowledging these limitations, Problem Solvers can craft solutions that are realistic and achievable within the given constraints.

14) Feedback and input

Solving problems doesn't need to be an individual effort. Getting advice and opinions from others can offer important perspectives and fresh ideas. Input from colleagues, mentors, or users can enrich your understanding of the issue and open up new solution paths.

15) Continuous learning and adaptability

Problem-Solving is an ongoing process, and learning is a vital part of it. Adopt an approach of continuous learning and adaptability. Stay open to new information, emerging technologies, and best practices inProblem-Solving. Being adaptable allows individuals to adjust their approaches as new challenges arise, ensuring they remain effective Problem Solvers in dynamic environments.

Embrace the art of effective leadership and propel your career forward with our exclusive Management Training – Sign up now!

16) Six thinking hats

Different people solve problems uniquely, influenced by their team, job roles, biases, or internal politics. The Six Thinking Hats method helps them tackle problems from various perspectives, focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or potential drawbacks. This framework effectively removes roadblocks, enabling teams to address all aspects of complex problems comprehensively.

17) Lightening Decision Jam (LDJ)

The process involves a series of timed exercises that guide participants through identifying issues, generating solutions, deciding on the best solutions to pursue, and creating action steps. The goal of an LDJ is to sidestep the usual debate and analysis paralysis that can occur in team meetings, leading to clear, actionable outcomes in a short amount of time. This method is particularly useful for solving specific problems, improving processes, or breaking through creative blocks.

18) Problem definition process

Complex problems don't always require complex solutions; often, simple approaches are enough to tackle them effectively.

Starting with a clear identification and definition of the problem allows the group to shift their perspective, seeing the problem as an opportunity for change. The process begins with pinpointing a central question and examining its various aspects. Then, the group divides into five teams, each adopting unique approaches like escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion, or wishful thinking to tackle the issue.

Each team sets a goal related to the problem and brainstorms solutions according to their assigned method, which is later shared with the entire group. This technique facilitates deep conversation and opens the door to innovative solutions by encouraging diverse thinking and creativity.

19) The Five whys

Sometimes, a team must dig deeper to understand the core reason behind issues in an organisation. RCA helps in pinpointing the root cause of business problems or ongoing challenges. The 5 Whys is a simple and powerful method for locating the root cause of any problem. It starts with forming a problem statement and then asking "why" five times to gradually get to the heart of the issue. This method offers a clear path to discovering the true cause behind a problem.

20) World cafe

World Cafe is a method that makes it easier for large groups to tackle complex issues together. It works by setting up a cosy, cafe-like environment where people can naturally group together to discuss topics that matter to them, all focused on solving a key problem. By arranging the space like a cafe and guiding participants at the start, you can then let them drive the conversation.

Integrating problem-Solving into the culture of an organisation can be challenging. However, friendly and inviting approaches such as World Cafe are particularly useful for welcoming those who are new to workshop settings, making it easier for everyone to contribute.

21) Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

Creating a comfortable environment where people can openly share and learn from each other is key to finding solutions together. DAD is a method that can guide a group in deciding which issues they want to tackle and how they plan to solve them. It's really effective in reducing resistance to change and ensuring everyone agrees with the plan.

This approach also promotes commitment by giving those directly involved the power to make decisions. It's an essential technique for anyone leading group discussions or workshops.

22) Design Sprint 2.0

Do you want to know how a team can tackle big challenges and quickly move on to creating and testing solutions? Jake Knapp's Design Sprint 2.0, from his book "Sprint," gives you a full plan for a four-day workshop that really works.

Making a good plan can be hard, and making sure you do everything right can be stressful or take a lot of time, especially if you're not used to it. If you're stuck on a tough problem and want to get your team focused on a fast way to test a new idea or find a quick solution, this four-day workshop template is perfect. It's all about moving quickly and efficiently.

23) Open space technology

Open Space Technology is created by Harrison Owen. It is a method where big groups can actively solve problems and lead discussions themselves. It works well when there is a lot of knowledge and different perspectives in the room, and you want to explore different ways to tackle a specific issue.

First, gather everyone to focus on a main topic. Go over some basic rules to help guide everyone in solving the problem. Then, let each person pick an issue related to the topic they care about and are willing to handle.

People then write their chosen issue on a paper, announce it to everyone, choose a time and place for a discussion, and put the paper on a wall. As the wall gets covered with different sessions, everyone picks the ones they are interested in and feel they can add value to, and that is when the discussions start. Groups discuss their chosen topics, take notes, and, if it makes sense, share what they have found with everyone else later.

By employing these Problem-Solving Techniques, individuals and organisations can become proficient in tackling a wide range of challenges and making well-informed decisions. Effective Problem-Solving skills are invaluable assets that lead to growth, success, and continuous improvement.

Conclusion

We hope you read and understand everything about Problem-Solving Techniques. Mastering these techniques empowers individuals to overcome challenges with confidence and make informed decisions. These skills foster adaptability and continuous improvement, leading to successful outcomes in personal and professional contexts.

Master the art of leadership and accelerate your professional growth with our Introduction To Management Course – Sign up today!

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-Solving Techniques help conflict management by finding common ground and creating solutions everyone agrees on. They encourage open communication and understanding, which can reduce tension and resolve disputes.

Problem-Solving Techniques can boost personal growth by teaching you how to tackle challenges head-on. They improve critical thinking and decision-making skills, making you more adaptable and resilient in various situations.

The Knowledge Academy’s Knowledge Pass , a prepaid voucher, adds another layer of flexibility, allowing course bookings over a 12-month period. Join us on a journey where education knows no bounds.

The Knowledge Academy takes global learning to new heights, offering over 30,000 online courses across 490+ locations in 220 countries. This expansive reach ensures accessibility and convenience for learners worldwide.

Alongside our diverse Online Course Catalogue, encompassing 17 major categories, we go the extra mile by providing a plethora of free educational Online Resources like News updates, Blogs , videos, webinars, and interview questions. Tailoring learning experiences further, professionals can maximise value with customisable Course Bundles of TKA .

The Knowledge Academy offers various Management Courses , including Problem-Solving, Personal & Organisational Development and Business Process Improvement Training. These courses cater to different skill levels, providing comprehensive insights into Problem-Solving .

Our Business Skills blogs covers a range of topics related to Communication Skills, offering valuable resources, best practices, and industry insights. Whether you are a beginner or looking to advance your Communication skills, The Knowledge Academy's diverse courses and informative blogs have you covered.

Upcoming Business Skills Resources Batches & Dates

Fri 14th Jun 2024

Fri 23rd Aug 2024

Fri 11th Oct 2024

Fri 13th Dec 2024

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

Table of Contents

The problem-solving process, how to solve problems: 5 steps, train to solve problems with lean today, what is problem solving steps, techniques, & best practices explained.

Problem solving is the art of identifying problems and implementing the best possible solutions. Revisiting your problem-solving skills may be the missing piece to leveraging the performance of your business, achieving Lean success, or unlocking your professional potential.

Ask any colleague if they’re an effective problem-solver and their likely answer will be, “Of course! I solve problems every day.”

Problem solving is part of most job descriptions, sure. But not everyone can do it consistently.

Problem solving is the process of defining a problem, identifying its root cause, prioritizing and selecting potential solutions, and implementing the chosen solution.

There’s no one-size-fits-all problem-solving process. Often, it’s a unique methodology that aligns your short- and long-term objectives with the resources at your disposal. Nonetheless, many paradigms center problem solving as a pathway for achieving one’s goals faster and smarter.

One example is the Six Sigma framework , which emphasizes eliminating errors and refining the customer experience, thereby improving business outcomes. Developed originally by Motorola, the Six Sigma process identifies problems from the perspective of customer satisfaction and improving product delivery.

Lean management, a similar method, is about streamlining company processes over time so they become “leaner” while producing better outcomes.

Trendy business management lingo aside, both of these frameworks teach us that investing in your problem solving process for personal and professional arenas will bring better productivity.

1. Precisely Identify Problems

As obvious as it seems, identifying the problem is the first step in the problem-solving process. Pinpointing a problem at the beginning of the process will guide your research, collaboration, and solutions in the right direction.

At this stage, your task is to identify the scope and substance of the problem. Ask yourself a series of questions:

- What’s the problem?

- How many subsets of issues are underneath this problem?

- What subject areas, departments of work, or functions of business can best define this problem?

Although some problems are naturally large in scope, precision is key. Write out the problems as statements in planning sheets . Should information or feedback during a later step alter the scope of your problem, revise the statements.

Framing the problem at this stage will help you stay focused if distractions come up in later stages. Furthermore, how you frame a problem will aid your search for a solution. A strategy of building Lean success, for instance, will emphasize identifying and improving upon inefficient systems.

2. Collect Information and Plan

The second step is to collect information and plan the brainstorming process. This is another foundational step to road mapping your problem-solving process. Data, after all, is useful in identifying the scope and substance of your problems.

Collecting information on the exact details of the problem, however, is done to narrow the brainstorming portion to help you evaluate the outcomes later. Don’t overwhelm yourself with unnecessary information — use the problem statements that you identified in step one as a north star in your research process.

This stage should also include some planning. Ask yourself:

- What parties will ultimately decide a solution?

- Whose voices and ideas should be heard in the brainstorming process?

- What resources are at your disposal for implementing a solution?

Establish a plan and timeline for steps 3-5.

3. Brainstorm Solutions

Brainstorming solutions is the bread and butter of the problem-solving process. At this stage, focus on generating creative ideas. As long as the solution directly addresses the problem statements and achieves your goals, don’t immediately rule it out.

Moreover, solutions are rarely a one-step answer and are more like a roadmap with a set of actions. As you brainstorm ideas, map out these solutions visually and include any relevant factors such as costs involved, action steps, and involved parties.

With Lean success in mind, stay focused on solutions that minimize waste and improve the flow of business ecosystems.

Become a Quality Management Professional

- 10% Growth In Jobs Of Quality Managers Profiles By 2025

- 11% Revenue Growth For Organisations Improving Quality

Certified Lean Six Sigma Green Belt

- 4 hands-on projects to perfect the skills learnt

- 4 simulation test papers for self-assessment

Lean Six Sigma Expert

- IASSC® Lean Six Sigma Green Belt and Black Belt certification

- 13 Projects, 12 Simulation exams, 18 Case Studies & 114 PDUs

Here's what learners are saying regarding our programs:

Xueting Liu

Mechanical engineer student at sargents pty. ltd. ,.

A great training and proper exercise with step-by-step guide! I'll give a rating of 10 out of 10 for this training.

Abdus Salam

I have completed the Lean Six Sigma Expert Master’s Program from Simplilearn. And after the course, I could take up new projects and perform better. My average pay rate for a research position increased by 21%.

4. Decide and Implement

The most critical stage is selecting a solution. Easier said than done. Consider the criteria that has arisen in previous steps as you decide on a solution that meets your needs.

Once you select a course of action, implement it.

Practicing due diligence in earlier stages of the process will ensure that your chosen course of action has been evaluated from all angles. Often, efficient implementation requires us to act correctly and successfully the first time, rather than being hurried and sloppy. Further compilations will create more problems, bringing you back to step 1.

5. Evaluate

Exercise humility and evaluate your solution honestly. Did you achieve the results you hoped for? What would you do differently next time?

As some experts note, formulating feedback channels into your evaluation helps solidify future success. A framework like Lean success, for example, will use certain key performance indicators (KPIs) like quality, delivery success, reducing errors, and more. Establish metrics aligned with company goals to assess your solutions.

Master skills like measurement system analysis, lean principles, hypothesis testing, process analysis and DFSS tools with our Lean Six Sigma Green Belt Training Course . Sign-up today!

Become a quality expert with Simplilearn’s Lean Six Sigma Green Belt . This Lean Six Sigma certification program will help you gain key skills to excel in digital transformation projects while improving quality and ultimate business results.

In this course, you will learn about two critical operations management methodologies – Lean practices and Six Sigma to accelerate business improvement.

Our Quality Management Courses Duration And Fees

Explore our top Quality Management Courses and take the first step towards career success

Get Free Certifications with free video courses

Quality Management

Lean Management

Project Management

Learn from industry experts with free masterclasses, digital marketing.

The Top 10 AI Tools You Need to Master Marketing in 2024

SEO vs. PPC: Which Digital Marketing Career Path Fits You Best in 2024?

Unlock Digital Marketing Career Success Secrets for 2024 with Purdue University

Recommended Reads

Introduction to Machine Learning: A Beginner's Guide

Webinar Wrap-up: Mastering Problem Solving: Career Tips for Digital Transformation Jobs

An Ultimate Guide That Helps You to Develop and Improve Problem Solving in Programming

Free eBook: 21 Resources to Find the Data You Need

ITIL Problem Workaround: A Leader’s Guide to Manage Problems

Your One-Stop Solution to Understand Coin Change Problem

Get Affiliated Certifications with Live Class programs

- PMP, PMI, PMBOK, CAPM, PgMP, PfMP, ACP, PBA, RMP, SP, and OPM3 are registered marks of the Project Management Institute, Inc.

7.3 Problem-Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

Problems themselves can be classified into two different categories known as ill-defined and well-defined problems (Schacter, 2009). Ill-defined problems represent issues that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solutions whereas well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solutions, and clear expected solutions. Problem solving often incorporates pragmatics (logical reasoning) and semantics (interpretation of meanings behind the problem), and also in many cases require abstract thinking and creativity in order to find novel solutions. Within psychology, problem solving refers to a motivational drive for reading a definite “goal” from a present situation or condition that is either not moving toward that goal, is distant from it, or requires more complex logical analysis for finding a missing description of conditions or steps toward that goal. Processes relating to problem solving include problem finding also known as problem analysis, problem shaping where the organization of the problem occurs, generating alternative strategies, implementation of attempted solutions, and verification of the selected solution. Various methods of studying problem solving exist within the field of psychology including introspection, behavior analysis and behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experimentation.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them (table below). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error. The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

Further problem solving strategies have been identified (listed below) that incorporate flexible and creative thinking in order to reach solutions efficiently.

Additional Problem Solving Strategies :

- Abstraction – refers to solving the problem within a model of the situation before applying it to reality.

- Analogy – is using a solution that solves a similar problem.

- Brainstorming – refers to collecting an analyzing a large amount of solutions, especially within a group of people, to combine the solutions and developing them until an optimal solution is reached.

- Divide and conquer – breaking down large complex problems into smaller more manageable problems.

- Hypothesis testing – method used in experimentation where an assumption about what would happen in response to manipulating an independent variable is made, and analysis of the affects of the manipulation are made and compared to the original hypothesis.

- Lateral thinking – approaching problems indirectly and creatively by viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.

- Means-ends analysis – choosing and analyzing an action at a series of smaller steps to move closer to the goal.

- Method of focal objects – putting seemingly non-matching characteristics of different procedures together to make something new that will get you closer to the goal.

- Morphological analysis – analyzing the outputs of and interactions of many pieces that together make up a whole system.

- Proof – trying to prove that a problem cannot be solved. Where the proof fails becomes the starting point or solving the problem.

- Reduction – adapting the problem to be as similar problems where a solution exists.

- Research – using existing knowledge or solutions to similar problems to solve the problem.

- Root cause analysis – trying to identify the cause of the problem.

The strategies listed above outline a short summary of methods we use in working toward solutions and also demonstrate how the mind works when being faced with barriers preventing goals to be reached.

One example of means-end analysis can be found by using the Tower of Hanoi paradigm . This paradigm can be modeled as a word problems as demonstrated by the Missionary-Cannibal Problem :

Missionary-Cannibal Problem

Three missionaries and three cannibals are on one side of a river and need to cross to the other side. The only means of crossing is a boat, and the boat can only hold two people at a time. Your goal is to devise a set of moves that will transport all six of the people across the river, being in mind the following constraint: The number of cannibals can never exceed the number of missionaries in any location. Remember that someone will have to also row that boat back across each time.

Hint : At one point in your solution, you will have to send more people back to the original side than you just sent to the destination.

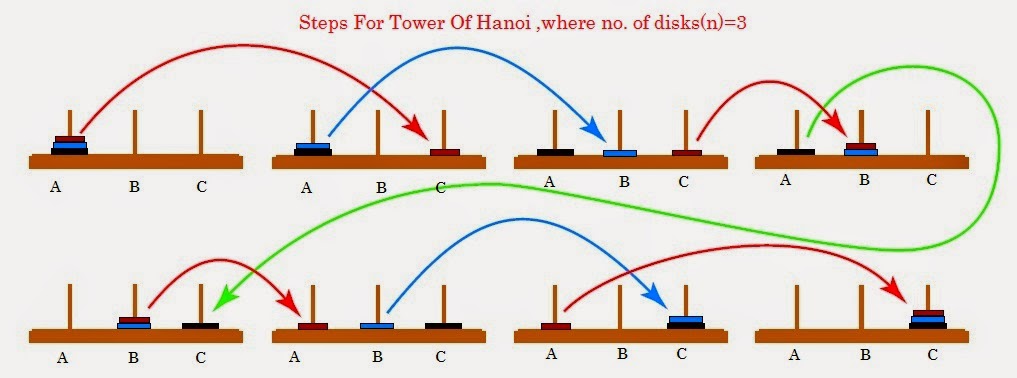

The actual Tower of Hanoi problem consists of three rods sitting vertically on a base with a number of disks of different sizes that can slide onto any rod. The puzzle starts with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod, the smallest at the top making a conical shape. The objective of the puzzle is to move the entire stack to another rod obeying the following rules:

- 1. Only one disk can be moved at a time.

- 2. Each move consists of taking the upper disk from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty rod.

- 3. No disc may be placed on top of a smaller disk.

Figure 7.02. Steps for solving the Tower of Hanoi in the minimum number of moves when there are 3 disks.

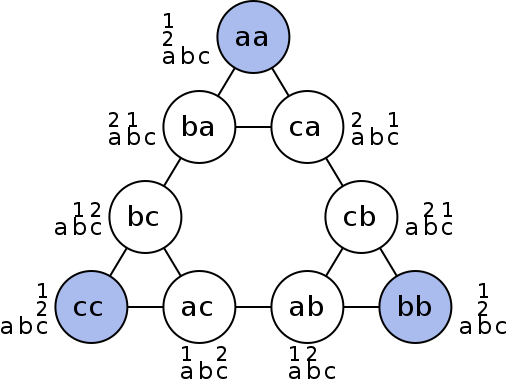

Figure 7.03. Graphical representation of nodes (circles) and moves (lines) of Tower of Hanoi.

The Tower of Hanoi is a frequently used psychological technique to study problem solving and procedure analysis. A variation of the Tower of Hanoi known as the Tower of London has been developed which has been an important tool in the neuropsychological diagnosis of executive function disorders and their treatment.

GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY AND PROBLEM SOLVING

As you may recall from the sensation and perception chapter, Gestalt psychology describes whole patterns, forms and configurations of perception and cognition such as closure, good continuation, and figure-ground. In addition to patterns of perception, Wolfgang Kohler, a German Gestalt psychologist traveled to the Spanish island of Tenerife in order to study animals behavior and problem solving in the anthropoid ape.

As an interesting side note to Kohler’s studies of chimp problem solving, Dr. Ronald Ley, professor of psychology at State University of New York provides evidence in his book A Whisper of Espionage (1990) suggesting that while collecting data for what would later be his book The Mentality of Apes (1925) on Tenerife in the Canary Islands between 1914 and 1920, Kohler was additionally an active spy for the German government alerting Germany to ships that were sailing around the Canary Islands. Ley suggests his investigations in England, Germany and elsewhere in Europe confirm that Kohler had served in the German military by building, maintaining and operating a concealed radio that contributed to Germany’s war effort acting as a strategic outpost in the Canary Islands that could monitor naval military activity approaching the north African coast.

While trapped on the island over the course of World War 1, Kohler applied Gestalt principles to animal perception in order to understand how they solve problems. He recognized that the apes on the islands also perceive relations between stimuli and the environment in Gestalt patterns and understand these patterns as wholes as opposed to pieces that make up a whole. Kohler based his theories of animal intelligence on the ability to understand relations between stimuli, and spent much of his time while trapped on the island investigation what he described as insight , the sudden perception of useful or proper relations. In order to study insight in animals, Kohler would present problems to chimpanzee’s by hanging some banana’s or some kind of food so it was suspended higher than the apes could reach. Within the room, Kohler would arrange a variety of boxes, sticks or other tools the chimpanzees could use by combining in patterns or organizing in a way that would allow them to obtain the food (Kohler & Winter, 1925).

While viewing the chimpanzee’s, Kohler noticed one chimp that was more efficient at solving problems than some of the others. The chimp, named Sultan, was able to use long poles to reach through bars and organize objects in specific patterns to obtain food or other desirables that were originally out of reach. In order to study insight within these chimps, Kohler would remove objects from the room to systematically make the food more difficult to obtain. As the story goes, after removing many of the objects Sultan was used to using to obtain the food, he sat down ad sulked for a while, and then suddenly got up going over to two poles lying on the ground. Without hesitation Sultan put one pole inside the end of the other creating a longer pole that he could use to obtain the food demonstrating an ideal example of what Kohler described as insight. In another situation, Sultan discovered how to stand on a box to reach a banana that was suspended from the rafters illustrating Sultan’s perception of relations and the importance of insight in problem solving.

Grande (another chimp in the group studied by Kohler) builds a three-box structure to reach the bananas, while Sultan watches from the ground. Insight , sometimes referred to as an “Ah-ha” experience, was the term Kohler used for the sudden perception of useful relations among objects during problem solving (Kohler, 1927; Radvansky & Ashcraft, 2013).

Solving puzzles.

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below (see figure) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

How long did it take you to solve this sudoku puzzle? (You can see the answer at the end of this section.)

Here is another popular type of puzzle (figure below) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

Did you figure it out? (The answer is at the end of this section.) Once you understand how to crack this puzzle, you won’t forget.

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below (figure below). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

What steps did you take to solve this puzzle? You can read the solution at the end of this section.

Pitfalls to problem solving.

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the table below.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in the figure below? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in the figures above? Here are the answers.

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Review Questions:

1. A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

a. an algorithm

b. a heuristic

c. a mental set

d. trial and error

2. Solving the Tower of Hanoi problem tends to utilize a ________ strategy of problem solving.

a. divide and conquer

b. means-end analysis

d. experiment

3. A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

4. Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

a. anchoring bias

b. confirmation bias

c. representative bias

d. availability bias

5. Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

6. Wolfgang Kohler analyzed behavior of chimpanzees by applying Gestalt principles to describe ________.

a. social adjustment

b. student load payment options

c. emotional learning

d. insight learning

7. ________ is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for.

a. functional fixedness

c. working memory

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

2. How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

Personal Application Question:

1. Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

anchoring bias

availability heuristic

confirmation bias

functional fixedness

hindsight bias

problem-solving strategy

representative bias

trial and error

working backwards

Answers to Exercises

algorithm: problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

anchoring bias: faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

availability heuristic: faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

confirmation bias: faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

functional fixedness: inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

heuristic: mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

hindsight bias: belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

mental set: continually using an old solution to a problem without results

problem-solving strategy: method for solving problems

representative bias: faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

trial and error: problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

working backwards: heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.