9 Collaboration techniques to solve problems: A guide for leaders and people managers

Knowing when to ask for help is a strength. Learn why collaboration to solve problems is essential to your business and how to promote a culture of teamwork.

Table of Contents

Imagine you’re in Rome for the summer. You don’t speak the language and the transportation system is completely different from your home country.

You’re using Google Maps and a translation app to read signs and get around on your own. But after wandering around the Roma Termini for 15 minutes with no idea where to find your train platform, it’s time to get some help.

In this case, no one would think less of you for asking for directions. So why are we often too worried about being judged to do the same at work?

It’s a strength to know when to seek help and use collaboration to solve problems. Acknowledging that there are things you don’t know or can’t solve on your own isn’t only smart, but is actually more productive. As soon as you and your team start playing to each other’s strengths, you’ll find those KPIs far more achievable.

Instead of spinning their wheels when they’re stuck on a problem, your team needs to know when to bring in an outside perspective to find possible solutions. By the end of this article, you’ll have a clear understanding of the benefits of collaborative problem-solving and learn how to get your team working together to overcome challenges.

Work together to find the best solutions to your business problems. Add a whiteboard to your Switchboard room and collect your team’s ideas live or async. Learn more

Benefits of collaborative problem solving

Solving complex problems in groups helps you find solutions faster. With more perspectives in the room, you’ll get ideas you’d never have thought of alone. In fact, collaboration can cause teams to spend 24% less time on idea generation. Together, you’ll spark more ideas and reach innovative solutions more quickly.

Not only that, but looking at problems in groups allows your team to learn from others, which can make them more resilient to issues in future.

Peer-to-peer learning is also an opportunity to upskill your team while strengthening their relationships. That’s because collaborative problem-solving encourages people to trust each other as they work together towards common goals. It’s team collaboration best practice to encourage your team to share ideas without risk of humiliation.

How to get your team to solve problems collaboratively

Promoting collaborative problem-solving skills within your team allows you to create a culture where people are comfortable seeking feedback on their work. That means you won’t have to host a dedicated brainstorming session to get your team to collaborate—they’ll just start doing it naturally.

To get there, you need to foster a psychologically safe environment, provide them with the right tools, and reinforce the power of teamwork whenever possible. Here are ways to enable a collaborative problem-solving culture:

1. Create the right environment

Simply inviting your team to work together isn’t enough for them to actually do it. You need to foster psychological safety so they feel comfortable sharing ideas and aren’t afraid of getting called out if they are wrong.

It all starts with your team culture

Your culture should be supportive, inclusive, safe, trusting, respectful, and empathetic. It should make people certain that asking for help is a sign of strength, not weakness.

Remind your team that brainstorming spaces are safe and all ideas are welcomed. They shouldn’t wait until they have a perfect solution to intervene. Be open-minded and treat all ideas as important even if you think they aren’t viable. This can be as simple as writing down all solutions on a shared document and asking questions for further clarification.

Give them what they need to do their job

Set your team up with the necessary resources and information to solve problems effectively. This includes written guidelines or even training on communication, leading a brainstorming session, or problem solving skills.

Also, technology improves collaboration in the workplace , so equip your team with the right tools for effective communication, information sharing, and project management. Make sure your team finds it easy to work with the tools they have. If they struggle to reach team mates due to technicalities, they’ll likely end up working on their own.

Switchboard can support your existing tech stack since all browser-based apps work in their persistent rooms. In this visual digital workspace , team members always know where to find project-related information and can work together on those apps directly from Switchboard—without switching tabs.

2. Promote open, transparent communication and feedback

A huge part of creating a psychologically safe environment for collaboration is encouraging open communication and establishing a culture that embraces feedback. Using active listening techniques, such as paraphrasing their words to check your understanding, can help you truly understand individual points of view focusing only on your answer.

For example, if your team member is struggling to find the words to express themselves, don’t jump in straight away with your own assumptions. Listen openly and let them fill the silence with their thoughts. Then, try and summarize what they’ve said so far and let them correct you.

It’s also important to be transparent when setting goals and addressing potential setbacks.

“The clearer you can be about what you need as a leader, what you need from your team, and what your clients need, you’ll be able to take action that's in alignment with creating that outcome,” says Tarah Keech , Founder of Tarah Keech Coaching .

Finally, follow-up on discussions when you have results so each contributor can see the impact of their input.

3. Set clear common goals

What makes collaboration different from compromising, for example, is that you get to work toward a common objective . When team members have a shared purpose, they become allies and are more likely to work together to find the best solution possible, instead of trying to be in the right.

For instance, when you offer profit sharing, people earn more money if the company makes higher revenue. That means if two people work together on finding a solution, they’ll likely decide on the one that’s better for the business—because, in the end, it’ll be beneficial for both.

Also, when you set clear goals for the collaboration, you get more focused answers and help improve team productivity. For example, start a brainstorming session by clearly stating the problem “Sign-ups are down by 1%, we need to come up with ideas to get back to the regular signup rate.”

Making it clear that you’ve identified a gap and know exactly what you need from others helps them understand why the session is relevant and what they need to do.

4. Present collaboration as a win-win

If you don’t set up a collaborative culture, team members will spin their wheels rather than get help to solve a problem. It’s crucial that you explain the benefits of collaboration clearly to your team so you can:

- Reach profitable business solutions

- Make people feel heard and valued

- Bring your team together

- Increase trust in the company’s decisions

- Make people feel part of something bigger

- Promote knowledge sharing

It’s your job to help team members understand that collaboration is beneficial for both individual and collective success—and find win-win scenarios.

5. Eliminate silos and solicit diverse opinions

Working in silos can affect productivity and morale as people spend more time coming up with solutions. A way to eliminate silos is by encouraging cross-functional projects and hosting team-building activities for colleagues to get to know each other.

“The only path that creates positive change is the one you haven't taken yet,” says Tarah. Encouraging teamwork allows you to come up with more diverse alternatives to problems. “And, the fastest way to identify the path that works is by using each other as resources and co-creators,” she adds.

Gather multiple perspectives on a problem by ensuring everyone shares their thoughts even if they’re introverted. For example, create a Switchboard room and invite everyone to add one or two ideas to the whiteboard either during or before the meeting. Then, go over each one of those ideas and vote on the best ones. This can happen anonymously so people feel more comfortable sharing their thoughts.

This is an easy way to bring diverse people together and see problems from multiple perspectives. “We all have stories from our lives where we pull lessons from. Imagine if we had access to other people's lessons. How much time would that save us?” says Tarah.

6. Train your team on how to resolve conflicts

Conflict resolution is a skill all managers should have, so make sure to give training on this topic. Equip your team with problem-resolution skills—for them to find mutually beneficial solutions. This will allow them to address disagreements and conflicts before they escalate to something bigger. Do this by:

Leaving your ego at the door

Many times conflicts occur when people take things personally or when you enter team meetings with your ego by your side.

The best advice for learning how to solve conflicts is to leave your ego at the door and assume you all want what’s best for the business. The idea of working together toward a common goal instead of discussing who’s right or which proposal is best helps reach consensus and a better alternative to all ideas.

7. “Yes, and…” every idea

This concept comes from improv and means acknowledging others’ proposals and adding to them. Improv actors use this technique to come up with stories in a group.

For example, someone enters the scene and goes “Help, mother, help!” The next person should say “ Yes , dear, I’m here. And , what do you need?” If they enter the room and say “I’ve told you a thousand times, I’m not your mother,” it’ll neglect the first actor’s proposal and can make the story stagnant.

You can apply this practice to business teamwork. If during collaborative problem-solving, you suggest an idea and someone neglects that thought, the conversation goes nowhere.

Instead, try establishing a “yes, and…” mentality to move the conversation forward. This is an example of how this would look in practice:

- Do: “I think the problem is that users are struggling to find the sign-up button.” “ Yes , that’s a potential issue, and it might also be because the color of the button doesn’t stand out. Let’s look at our web page analytics.”

- Don’t: “I think the problem is that users are struggling to find the sign-up button.” “Hmm, not really , we’ve conducted usability testing and that was never an issue.”

This mindset gives space for ideas to grow, even if they seem off the mark initially. Let people explain their thoughts and you'll be surprised how solutions can result. Avoid premature judgment and create a safe space for creativity and exploration.

8. Play to everyone’s strengths

You can’t expect the same type of insights from all team members. The beauty of having diverse people on your team is that they can all add to the conversation from their unique perspectives.

Assign roles and responsibilities based on team members' strengths and expertise. Encourage collaboration and reach potential solutions to problems by assigning tasks that require different skill sets.

For example, let’s say the customer support team’s workload increased in the last month. They don’t know why, but people keep complaining about their orders being wrong. The team is so busy trying to find quick solutions for the customers that they can’t take the time to get to the root cause of the problem.

You can’t afford to close the online store and decide to host a brainstorming session with one or two key players from each department. Inviting them to this session helps bring their own experiences to the table and will help you find the problem faster. Not necessarily the ones affected by an issue are the most suited to solve it.

9. Recognize and reward teamwork

Acknowledge and appreciate collaborative efforts within the team. Recognize individuals who actively contribute to problem-solving and emphasize the importance of teamwork. This will help you keep your team engaged and motivated as well as remind everyone that if they collaborate, they might get rewarded.

Give negative feedback in private with useful examples, and celebrate successes in public as a team. However, not everyone likes public recognition, so take time to understand what motivates different people from your team and implement it.

Encourage risk taking and turn failure into learning opportunities. Part of collaborating toward solutions is understanding that making mistakes is part of the process, and the faster you get to fail, the better.

The fastest way to succeed is by solving problems in groups

You can make mistakes as a tourist in Rome because the worst thing that could happen is getting lost for a couple of hours (and you can always call an Uber).

It’s different at work. Many people think that making mistakes could cause them to build up a bad reputation or, in extreme cases, lose their job. However, that mindset is what causes you to get stuck on a problem. And, if you don’t ask others to support you, you might struggle to come up with solutions in a timely manner.

But asking for help isn’t a mistake. It’s a sign of strength and your company should encourage people to seek different perspectives. To encourage your team to use collaboration to solve problems, build a psychologically safe environment for people to speak openly about their ideas.

Set common goals, eliminate siloed work, and promote a “yes, and…” mentality. And, along with leaving your ego at the door, you should get equipped with the right team collaboration tools .

Using a tool like Switchboard makes it easy for your team to work together to solve problems in a shared room. There, everyone can add files, edit content directly from browser-based applications, or include their ideas on a whiteboard to simplify team communication and reach solutions faster.

Work in groups to find the best solution to your business problems. Add a whiteboard to your Switchboard room and collect your worker’s ideas live or async. Learn more

Frequently asked questions about collaboration to solve problems

What is the purpose of collaboration.

The purpose of collaboration is to bring diverse people together to share ideas to work together towards solving a common goal. Teamwork can help organizations:

- Shorten decision-making loops

- Solve problems faster

- Drive innovation

- Improve knowledge sharing

- Tighten team relationships

- Get better at managing conflict

- Create a sense of belonging

What is the difference between collaboration and compromise?

The difference between collaboration and compromise is that the first one aims to reach a common goal; while compromising, means finding a middle ground. Collaboration presents the opportunity to reach win-win solutions while compromising means someone needs to cede.

What is the difference between brainstorming and collaborative problem-solving?

The difference between brainstorming and collaborative problem-solving is that brainstorming is meant for doing group work to come up with ideas that may or may not solve a problem. Collaborative problem-solving, on the other hand, is much more structured and aims to find practical solutions to a specific problem (brainstorming can be one of the techniques used to reach that solution).

Keep reading

Musings on remote work and the future of collaboration

8 Common meeting pitfalls and how to avoid them

How to run a productive design critique session

Stop, collaborate, and listen.

Get product updates and Switchboard tips and tricks delivered right to your inbox.

You can unsubscribe at any time using the links at the bottom of the newsletter emails. More information is in our privacy policy.

Work together to find the best solutions to your business problems.

Add a whiteboard to your Switchboard room and collect your team’s ideas live or async.

Collaborative Problem Solving: What It Is and How to Do It

What is collaborative problem solving, how to solve problems as a team, celebrating success as a team.

Problems arise. That's a well-known fact of life and business. When they do, it may seem more straightforward to take individual ownership of the problem and immediately run with trying to solve it. However, the most effective problem-solving solutions often come through collaborative problem solving.

As defined by Webster's Dictionary , the word collaborate is to work jointly with others or together, especially in an intellectual endeavor. Therefore, collaborative problem solving (CPS) is essentially solving problems by working together as a team. While problems can and are solved individually, CPS often brings about the best resolution to a problem while also developing a team atmosphere and encouraging creative thinking.

Because collaborative problem solving involves multiple people and ideas, there are some techniques that can help you stay on track, engage efficiently, and communicate effectively during collaboration.

- Set Expectations. From the very beginning, expectations for openness and respect must be established for CPS to be effective. Everyone participating should feel that their ideas will be heard and valued.

- Provide Variety. Another way of providing variety can be by eliciting individuals outside the organization but affected by the problem. This may mean involving various levels of leadership from the ground floor to the top of the organization. It may be that you involve someone from bookkeeping in a marketing problem-solving session. A perspective from someone not involved in the day-to-day of the problem can often provide valuable insight.

- Communicate Clearly. If the problem is not well-defined, the solution can't be. By clearly defining the problem, the framework for collaborative problem solving is narrowed and more effective.

- Expand the Possibilities. Think beyond what is offered. Take a discarded idea and expand upon it. Turn it upside down and inside out. What is good about it? What needs improvement? Sometimes the best ideas are those that have been discarded rather than reworked.

- Encourage Creativity. Out-of-the-box thinking is one of the great benefits of collaborative problem-solving. This may mean that solutions are proposed that have no way of working, but a small nugget makes its way from that creative thought to evolution into the perfect solution.

- Provide Positive Feedback. There are many reasons participants may hold back in a collaborative problem-solving meeting. Fear of performance evaluation, lack of confidence, lack of clarity, and hierarchy concerns are just a few of the reasons people may not initially participate in a meeting. Positive public feedback early on in the meeting will eliminate some of these concerns and create more participation and more possible solutions.

- Consider Solutions. Once several possible ideas have been identified, discuss the advantages and drawbacks of each one until a consensus is made.

- Assign Tasks. A problem identified and a solution selected is not a problem solved. Once a solution is determined, assign tasks to work towards a resolution. A team that has been invested in the creation of the solution will be invested in its resolution. The best time to act is now.

- Evaluate the Solution. Reconnect as a team once the solution is implemented and the problem is solved. What went well? What didn't? Why? Collaboration doesn't necessarily end when the problem is solved. The solution to the problem is often the next step towards a new collaboration.

The burden that is lifted when a problem is solved is enough victory for some. However, a team that plays together should celebrate together. It's not only collaboration that brings unity to a team. It's also the combined celebration of a unified victory—the moment you look around and realize the collectiveness of your success.

We can help

Check out MindManager to learn more about how you can ignite teamwork and innovation by providing a clearer perspective on the big picture with a suite of sharing options and collaborative tools.

Need to Download MindManager?

Try the full version of mindmanager free for 30 days.

Collaborative problem solvers are made not born – here’s what you need to know

Professor of Cognitive Sciences, University of Central Florida

Disclosure statement

Stephen M. Fiore has received funding from federal agencies such as NASA, ONR, DARPA, and the NSF to study collaborative problem solving and teamwork. He is past president of the Interdisciplinary Network for Group Research, currently a board member of the International Network for the Science of Team Science, and a member of DARPA's Information Science and Technology working group.

View all partners

Challenges are a fact of life. Whether it’s a high-tech company figuring out how to shrink its carbon footprint, or a local community trying to identify new revenue sources, people are continually dealing with problems that require input from others. In the modern world, we face problems that are broad in scope and great in scale of impact – think of trying to understand and identify potential solutions related to climate change, cybersecurity or authoritarian leaders.

But people usually aren’t born competent in collaborative problem-solving. In fact, a famous turn of phrase about teams is that a team of experts does not make an expert team . Just as troubling, the evidence suggests that, for the most part, people aren’t being taught this skill either. A 2012 survey by the American Management Association found that higher level managers believed recent college graduates lack collaboration abilities .

Maybe even worse, college grads seem to overestimate their own competence. One 2015 survey found nearly two-thirds of recent graduates believed they can effectively work in a team, but only one-third of managers agreed . The tragic irony is that the less competent you are, the less accurate is your self-assessment of your own competence. It seems that this infamous Dunning-Kruger effect can also occur for teamwork.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that in a 2015 international assessment of hundreds of thousands of students, less than 10% performed at the highest level of collaboration . For example, the vast majority of students could not overcome teamwork obstacles or resolve conflict. They were not able to monitor group dynamics or to engage in the kind of actions needed to make sure the team interacted according to their roles. Given that all these students have had group learning opportunities in and out of school over many years, this points to a global deficit in the acquisition of collaboration skills.

How can this deficiency be addressed? What makes one team effective while another fails? How can educators improve training and testing of collaborative problem-solving? Drawing from disciplines that study cognition, collaboration and learning, my colleagues and I have been studying teamwork processes. Based on this research, we have three key recommendations.

How it should work

At the most general level, collaborative problem-solving requires team members to establish and maintain a shared understanding of the situation they’re facing and any relevant problem elements they’ve identified. At the start, there’s typically an uneven distribution of knowledge on a team. Members must maintain communication to help each other know who knows what, as well as help each other interpret elements of the problem and which expertise should be applied.

Then the team can get to work, laying out subtasks based upon member roles, or creating mechanisms to coordinate member actions. They’ll critique possible solutions to identify the most appropriate path forward.

Finally, at a higher level, collaborative problem-solving requires keeping the team organized – for example, by monitoring interactions and providing feedback to each other. Team members need, at least, basic interpersonal competencies that help them manage relationships within the team (like encouraging participation) and communication (like listening to learn). Even better is the more sophisticated ability to take others’ perspectives, in order to consider alternative views of problem elements.

Whether it is a team of professionals in an organization or a team of scientists solving complex scientific problems , communicating clearly, managing conflict, understanding roles on a team, and knowing who knows what – all are collaboration skills related to effective teamwork.

What’s going wrong in the classroom?

When so many students are continually engaged in group projects, or collaborative learning, why are they not learning about teamwork? There are interrelated factors that may be creating graduates who collaborate poorly but who think they are quite good at teamwork.

I suggest students vastly overestimate their collaboration skills due to the dangerous combination of a lack of systematic instruction coupled with inadequate feedback. On the one hand, students engage in a great deal of group work in high school and college. On the other hand, students rarely receive meaningful instruction, modeling and feedback on collaboration . Decades of research on learning show that explicit instruction and feedback are crucial for mastery .

Although classes that implement collaborative problem-solving do provide some instruction and feedback, it’s not necessarily about their teamwork. Students are learning about concepts in classes; they are acquiring knowledge about a domain. What is missing is something that forces them to explicitly reflect on their ability to work with others.

When students process feedback on how well they learned something, or whether they solved a problem, they mistakenly think this is also indicative of effective teamwork. I hypothesize that students come to conflate learning course content material in any group context with collaboration competency.

A prescription for better collaborators

Now that we’ve defined the problem, what can be done? A century of research on team training , combined with decades of research on group learning in the classroom , points the way forward. My colleagues and I have distilled some core elements from this literature to suggest improvements for collaborative learning .

First, most pressing is to get training on teamwork into the world’s classrooms. At a minimum, this needs to happen during college undergraduate education, but even better would be starting in high school or earlier. Research has demonstrated it’s possible to teach collaboration competencies such as dealing with conflict and communicating to learn. Researchers and educators need, themselves, to collaborate to adapt these methods for the classroom.

Secondly, students need opportunities for practice. Although most already have experience working in groups, this needs to move beyond science and engineering classes. Students need to learn to work across disciplines so after graduation they can work across professions on solving complex societal problems.

Third, any systematic instruction and practice setting needs to include feedback. This is not simply feedback on whether they solved the problem or did well on learning course content. Rather, it needs to be feedback on interpersonal competencies that drive successful collaboration. Instructors should assess students on teamwork processes like relationship management, where they encourage participation from each other, as well as skills in communication where they actively listen to their teammates.

Even better would be feedback telling students how well they were able to take on the perspective of a teammate from another discipline. For example, was the engineering student able to take the view of a student in law and understand the legal ramifications of a new technology’s implementation?

My colleagues and I believe that explicit instruction on how to collaborate, opportunities for practice, and feedback about collaboration processes will better prepare today’s students to work together to solve tomorrow’s problems.

- Decision making

- Cooperation

- Problem solving

- Collaboration

- Dunning-Kruger effect

- Wicked problems

- student collaboration

- College graduates

- 21st century skills

- Group decision making

- Collaborative problem solving

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Strategy Implementation Manager

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

How to ace collaborative problem solving

April 30, 2023 They say two heads are better than one, but is that true when it comes to solving problems in the workplace? To solve any problem—whether personal (eg, deciding where to live), business-related (eg, raising product prices), or societal (eg, reversing the obesity epidemic)—it’s crucial to first define the problem. In a team setting, that translates to establishing a collective understanding of the problem, awareness of context, and alignment of stakeholders. “Both good strategy and good problem solving involve getting clarity about the problem at hand, being able to disaggregate it in some way, and setting priorities,” Rob McLean, McKinsey director emeritus, told McKinsey senior partner Chris Bradley in an Inside the Strategy Room podcast episode . Check out these insights to uncover how your team can come up with the best solutions for the most complex challenges by adopting a methodical and collaborative approach.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

Countering otherness: Fostering integration within teams

Psychological safety and the critical role of leadership development

If we’re all so busy, why isn’t anything getting done?

To weather a crisis, build a network of teams

Unleash your team’s full potential

Modern marketing: Six capabilities for multidisciplinary teams

Beyond collaboration overload

MORE FROM MCKINSEY

Take a step Forward

Business Collaboration collaborative culture company culture

5 Expert Collaborative Problem-Solving Strategies

Lorin mccann.

- December 9th, 2015

You don’t need to be an executive to initiate powerful change within your organization. According to collaboration expert Jane Ripley, collaboration begins with you.

Expecting superiors, employees, coworkers, or other departments to take responsibility will get you nowhere, fast. Instead, adopt collaboration as a personal responsibility and be unafraid to take initiative — it doesn’t matter if you’re an entry-level employee or a seasoned executive.

Jane Ripley is a collaboration expert and co-author of the book Collaboration Begins With You: Be a Silo Buster along with Ken Blanchard and Eunice Parisi-Carew (you can follow Jane on Twitter: @WiredLeadership ). Jane draws on her research working with companies ranging from small businesses and entrepreneurs to large, multi-national enterprises to talk about collaborative problem-solving strategies professionals can use no matter what organizational level they’re at.

Initiating collaborative problem-solving within an organization is a complex task, with many moving parts. Jane describes it well: “Imagine you’re in the aircraft and there’s this dashboard. You’ve got to try and get all the buttons and levers in the right places.” Collaboration within an organization is also a complex process.

The approach Jane and her co-authors adopt in their books aims to simplify a complex subject with actionable models, including the UNITE model for collaborative problem-solving:

U = Utilize difference N = Nurture safety and trust I = Involve others in creating a clear purpose, values, and goals T = Talk openly E = Empower yourself and others

Executives can use these strategies to transform the culture and impact of their organizations from the company culture from the top down. Alternatively,entry-level employees can adopt the same strategies to accelerate professional growth while offering enormous value to their organizations from the bottom up.

In this post, we’ll look at each of the elements of the UNITE model — and what you need to know to put them into action.

1. Utilize differences in collaborative problem-solving

Collaborative problem-solving relies on the presence of multiple perspectives.

Jane advises to remember that different perspectives are not personal. In fact, conflict is important.

Fear of contrasting opinions often indicates a competitive mindset, not a collaborative one. This only creates more problems rather than solving them.

“The power,” Jane says, “is in the combination of perspectives.”

2. Nurture safety and trust within your organization

Effective collaboration is impossible when trust isn’t a part of the culture.

Jane elaborates: “My co-author, Eunice Parisi-Carew, always says, ‘Fear is the number one inhibitor to collaboration, because if you’re inhibited, you won’t contribute, and if you don’t contribute nobody will know that you have a different perspective.’”

In fact, trust is one of the most crucial elements in being a silo-buster; it plays enormous role in preventing bottlenecks and accelerating growth.

“Some people come to the workplace trusting everybody, and they get let down. Other people come to the workplace believing nobody will do the work as well as they can. Those people try to do it all and become a bottleneck,” Jane explains.

Low trust within an organization rarely goes unnoticed. Even if executives are unaware of the problem, employees always are — it negatively impacts their ability to be effective.

A tell-tale sign of a low-trust culture for leaders is when people don’t contribute ideas. Jane shares a classic example: “When the leader sits at the meeting and says, ‘I’ve got this new thing that’s been handed to us from headquarters, now we’ve got to implement XYZ initiative. Any ideas?’ And…there’s no response.”

Silence follows because, as Jane explains, “not usually because [the employees] don’t have any ideas, it’s just that they just don’t want to voice them” — for fear of criticism, negative feedback, no feedback, or backlash.

3. Involve others for effective collaborative problem-solving

According to Jane, “Not all the best ideas come from the top, and not all the best ideas come from a specific group. Marketing can have a very valuable perspective on the use of collaborative software, and so can IT.”

It may be uncomfortable to involve people and departments with whom you don’t currently have a relationship, but it’s essential for effective collaborative problem-solving. Even as an entry-level employee, you can take the initiative to open the lines of communication to other people within your organization.

Invite someone to lunch — or suggest involving someone from another department in a final review on a project that could use their feedback. It’s a simple way to begin, but it’s powerful.

4. Don’t be afraid to talk openly

How important is speed to your organization? On a scale of one to ten it’s probably an eight, nine, or ten.

According to Jane, speed is the number-one benefit of talking openly, or transparency: “If you’ve all got the same information, you can all make decisions and bring those pieces of information together to solve the problem more quickly.” Alternatively, a lack of transparency creates confusion, more meetings, and more discussion.

“So now you’ve got a [unproductive] discussion instead of having everybody on the same level playing field all coming at it from the same approach, able to look at the data or the information and critically evaluate that,” she adds.

And speed isn’t the only benefit of talking openly. As counterintuitive as it may seem, so is security.

Jane often talks about information theft when discussing transparency. “When information is kept in silos you open up an opportunity for other people to prosper from it,” she says. “So an unscrupulous individual can take that information and do what they like with it, whereas if it’s common knowledge, it’s in the public domain, [and] they have no more power.”

5. Don’t wait to empower yourself and others

As a leader, empowering your organization starts with you. As an employee, it’s no different! You can’t wait for someone at the top to make the shift before you allow yourself to as well.

Jane shares insights into how both leaders and employees can take take steps to empower themselves, and in doing so empower others:

Firstly, leaders must discard a competitive mindset in favor of a collaborative one.

“Empowering yourself and others is the big part for the leader. [Leaders] are coaching for competence, creating clarity around goals, and setting boundaries. They’re removing roadblocks, sharing their networks, and giving opportunities to build knowledge… it’s how they help an individual become collaborative and make a greater contribution [to the organization].”

Instead of keeping your knowledge, network, and expertise close to the vest as a leader, share it openly with your employees. Not only will your experiences add enormous value to their professional growth, it will also empower them to be more effective in their jobs. They’ll also trust and appreciate you more.

Employees can also take initiative within their organization, regardless of the current company culture. They can start by offering their ideas, insights — even their networks.

Jane says, “It always amazes me how, particularly with the millennial generation, that they’re networked electronically they have some phenomenal people in their networks and can bring those equally to leaders who are sitting in a position maybe four, five, six, seven years older than them, it’s tremendous.”

People are innately collaborative

Jane ties together the concepts and action steps surrounding collaborative problem with a familiar example:

“People are innately collaborative. We do it innately and we do it socially. If somebody wants to throw a party everybody says,‘What should I bring?’‘What shall I do?’ ‘I’ll do the decorating!’

And yet, when they come to work, ‘Oh, wait a minute, the decorating belongs to that department, refreshments belongs to that department, so now we need a meeting.’”

“We’re wired,” Jane explains, “for collaboration, and it’s our workplace habits, systems, and beliefs that get in the way. For better collaborative problem-solving where you work, you don’t need more meetings.”

Instead, work on building a culture of collaboration by utilizing difference, nurturing safety and trust, involving others in creating a clear purpose, values, and goals, talking openly, and empowering yourself and others. And that’s something we all can do.

Lorin is an inbound marketer and demand generation specialist at Lotus Growth , a B2B marketing consultancy. She also helps entrepreneurs kick off new digital marketing strategies at Vrtical . Read more by Lorin McCann »

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Solve Problems

- Laura Amico

To bring the best ideas forward, teams must build psychological safety.

Teams today aren’t just asked to execute tasks: They’re called upon to solve problems. You’d think that many brains working together would mean better solutions, but the reality is that too often problem-solving teams fall victim to inefficiency, conflict, and cautious conclusions. The two charts below will help your team think about how to collaborate better and come up with the best solutions for the thorniest challenges.

- Laura Amico is a former senior editor at Harvard Business Review.

Partner Center

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

13 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

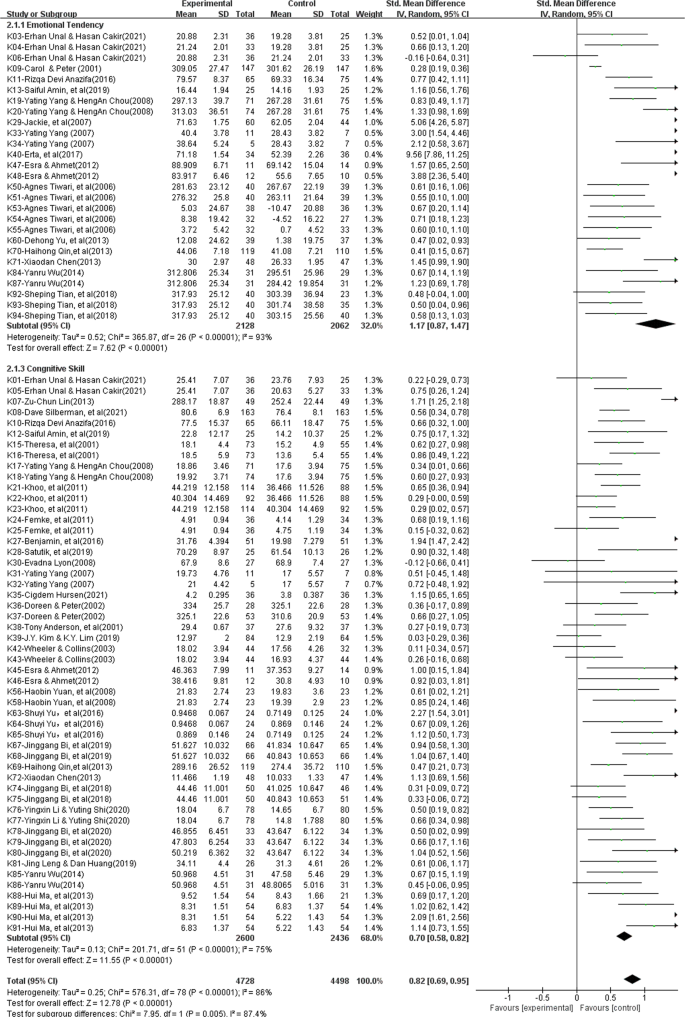

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Fostering twenty-first century skills among primary school students through math project-based learning

Nadia Rehman, Wenlan Zhang, … Samia Batool

A meta-analysis to gauge the impact of pedagogies employed in mixed-ability high school biology classrooms

Malavika E. Santhosh, Jolly Bhadra, … Noora Al-Thani

A guide to critical thinking: implications for dental education

Deborah Martin

Introduction

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

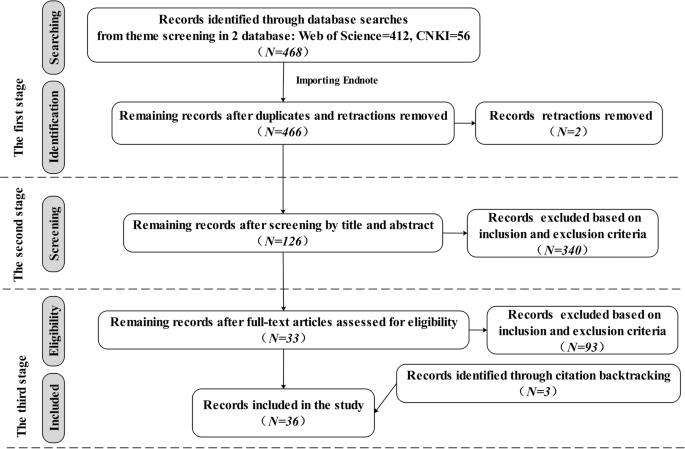

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Publication bias test

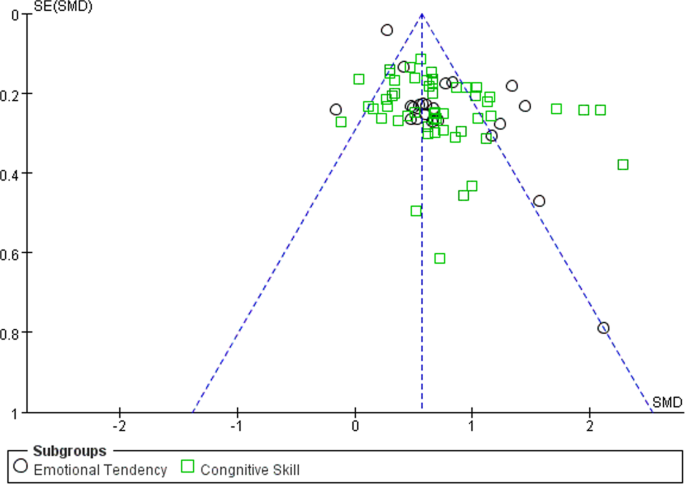

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.

Furthermore, the associated improvements in attitudinal tendency are much stronger, but the corresponding improvements in cognitive skill are only marginally better. According to certain studies, cognitive skill differs from the attitudinal tendency in classroom instruction; the cultivation and development of the former as a key ability is a process of gradual accumulation, while the latter as an attitude is affected by the context of the teaching situation (e.g., a novel and exciting teaching approach, challenging and rewarding tasks) (Halpern, 2001 ; Wei and Hong, 2022 ). Collaborative problem-solving as a teaching approach is exciting and interesting, as well as rewarding and challenging; because it takes the learners as the focus and examines problems with poor structure in real situations, and it can inspire students to fully realize their potential for problem-solving, which will significantly improve their attitudinal tendency toward solving problems (Liu et al., 2020 ). Similar to how collaborative problem-solving influences attitudinal tendency, attitudinal tendency impacts cognitive skill when attempting to solve a problem (Liu et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ), and stronger attitudinal tendencies are associated with improved learning achievement and cognitive ability in students (Sison, 2008 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). It can be seen that the two specific dimensions of critical thinking as well as critical thinking as a whole are affected by collaborative problem-solving, and this study illuminates the nuanced links between cognitive skills and attitudinal tendencies with regard to these two dimensions of critical thinking. To fully develop students’ capacity for critical thinking, future empirical research should pay closer attention to cognitive skills.

The moderating effects of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

In order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking, exploring possible moderating effects that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis. The findings show that the moderating factors, such as the teaching type, learning stage, group size, learning scaffold, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, could all support the cultivation of collaborative problem-solving in critical thinking. Among them, the effect size differences between the learning stage and measuring tool are not significant, which does not explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of the learning stage, various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively without significant intergroup differences, indicating that we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking.

Although high education accounts for 70.89% of all empirical studies performed by researchers, high school may be the appropriate learning stage to foster students’ critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving since it has the largest overall effect size. This phenomenon may be related to student’s cognitive development, which needs to be further studied in follow-up research.

With regard to teaching type, mixed course teaching may be the best teaching method to cultivate students’ critical thinking. Relevant studies have shown that in the actual teaching process if students are trained in thinking methods alone, the methods they learn are isolated and divorced from subject knowledge, which is not conducive to their transfer of thinking methods; therefore, if students’ thinking is trained only in subject teaching without systematic method training, it is challenging to apply to real-world circumstances (Ruggiero, 2012 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Teaching critical thinking as mixed course teaching in parallel to other subject teachings can achieve the best effect on learners’ critical thinking, and explicit critical thinking instruction is more effective than less explicit critical thinking instruction (Bensley and Spero, 2014 ).

In terms of the intervention duration, with longer intervention times, the overall effect size shows an upward tendency. Thus, the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated. Critical thinking, as a key competency for students in the 21st century, is difficult to get a meaningful improvement in a brief intervention duration. Instead, it could be developed over a lengthy period of time through consistent teaching and the progressive accumulation of knowledge (Halpern, 2001 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Therefore, future empirical studies ought to take these restrictions into account throughout a longer period of critical thinking instruction.

With regard to group size, a group size of 2–3 persons has the highest effect size, and the comprehensive effect size decreases with increasing group size in general. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a group composed of two to four members is most appropriate for collaborative learning (Schellens and Valcke, 2006 ). However, the meta-analysis results also indicate that once the group size exceeds 7 people, small groups cannot produce better interaction and performance than large groups. This may be because the learning scaffolds of technique support, resource support, and teacher support improve the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members, and a collaborative group with more members may increase the diversity of views, which is helpful to cultivate critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

With regard to the learning scaffold, the three different kinds of learning scaffolds can all enhance critical thinking. Among them, the teacher-supported learning scaffold has the largest overall effect size, demonstrating the interdependence of effective learning scaffolds and collaborative problem-solving. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a successful strategy is to encourage learners to collaborate, come up with solutions, and develop critical thinking skills by using learning scaffolds (Reiser, 2004 ; Xu et al., 2022 ); learning scaffolds can lower task complexity and unpleasant feelings while also enticing students to engage in learning activities (Wood et al., 2006 ); learning scaffolds are designed to assist students in using learning approaches more successfully to adapt the collaborative problem-solving process, and the teacher-supported learning scaffolds have the greatest influence on critical thinking in this process because they are more targeted, informative, and timely (Xu et al., 2022 ).