14 Crafting a Thesis Statement

Learning Objectives

- Craft a thesis statement that is clear, concise, and declarative.

- Narrow your topic based on your thesis statement and consider the ways that your main points will support the thesis.

Crafting a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know, clearly and concisely, what you are going to talk about. A strong thesis statement will allow your reader to understand the central message of your speech. You will want to be as specific as possible. A thesis statement for informative speaking should be a declarative statement that is clear and concise; it will tell the audience what to expect in your speech. For persuasive speaking, a thesis statement should have a narrow focus and should be arguable, there must be an argument to explore within the speech. The exploration piece will come with research, but we will discuss that in the main points. For now, you will need to consider your specific purpose and how this relates directly to what you want to tell this audience. Remember, no matter if your general purpose is to inform or persuade, your thesis will be a declarative statement that reflects your purpose.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech.

Once you have chosen your topic and determined your purpose, you will need to make sure your topic is narrow. One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to seven-minute speech. While five to seven minutes may sound like a long time for new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

Is your speech topic a broad overgeneralization of a topic?

Overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

Is your speech’s topic one clear topic or multiple topics?

A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and Women’s Equal Rights Amendment should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: Ratifying the Women’s Equal Rights Amendment as equal citizens under the United States law would protect women by requiring state and federal law to engage in equitable freedoms among the sexes.

Does the topic have direction?

If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good public speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Declarative Sentence

You wrote your general and specific purpose. Use this information to guide your thesis statement. If you wrote a clear purpose, it will be easy to turn this into a declarative statement.

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: To inform my audience about the lyricism of former President Barack Obama’s presentation skills.

Your thesis statement needs to be a declarative statement. This means it needs to actually state something. If a speaker says, “I am going to talk to you about the effects of social media,” this tells you nothing about the speech content. Are the effects positive? Are they negative? Are they both? We don’t know. This sentence is an announcement, not a thesis statement. A declarative statement clearly states the message of your speech.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Or you could state, “Socal media has both positive and negative effects on users.”

Adding your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement, we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin demonstrates exceptional use of rhetorical strategies.

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

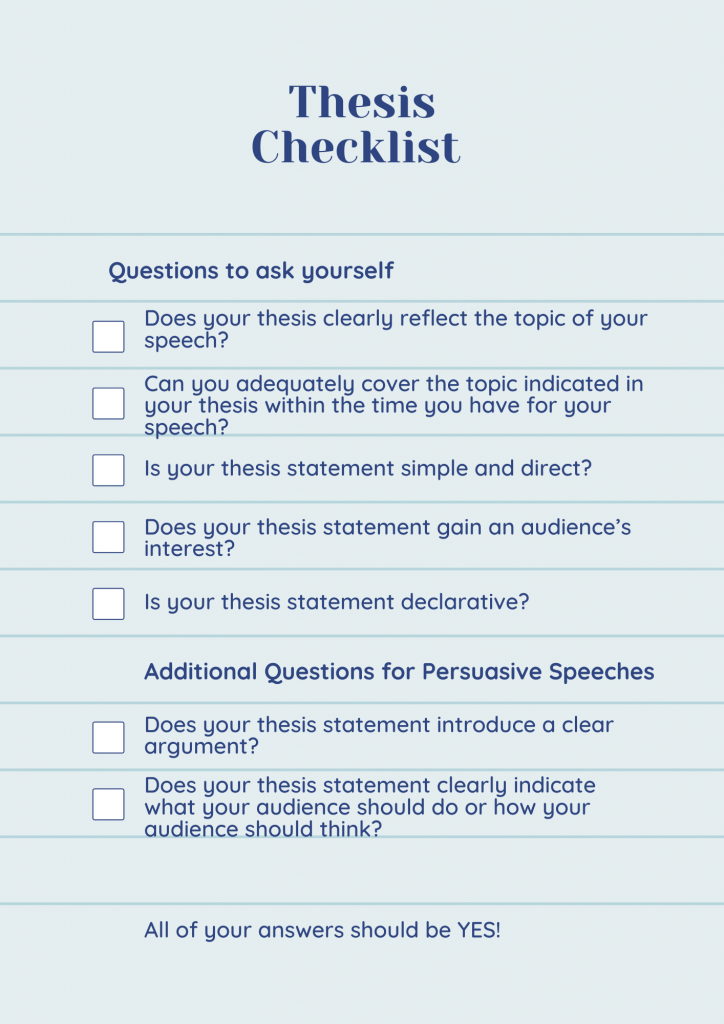

Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown below.

Preview of Speech

The preview, as stated in the introduction portion of our readings, reminds us that we will need to let the audience know what the main points in our speech will be. You will want to follow the thesis with the preview of your speech. Your preview will allow the audience to follow your main points in a sequential manner. Spoiler alert: The preview when stated out loud will remind you of main point 1, main point 2, and main point 3 (etc. if you have more or less main points). It is a built in memory card!

For Future Reference | How to organize this in an outline |

Introduction

Attention Getter: Background information: Credibility: Thesis: Preview:

Key Takeaways

Introductions are foundational to an effective public speech.

- A thesis statement is instrumental to a speech that is well-developed and supported.

- Be sure that you are spending enough time brainstorming strong attention getters and considering your audience’s goal(s) for the introduction.

- A strong thesis will allow you to follow a roadmap throughout the rest of your speech: it is worth spending the extra time to ensure you have a strong thesis statement.

Stand up, Speak out by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

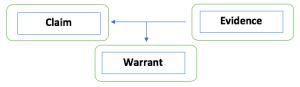

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Speech Crafting →

Public Speaking: Developing a Thesis Statement In a Speech

Understanding the purpose of a thesis statement in a speech

Diving headfirst into the world of public speaking, it’s essential to grasp the role of a thesis statement in your speech. Think of it as encapsulating the soul of your speech within one or two sentences.

It’s the declarative sentence that broadcasts your intent and main idea to captivate audiences from start to finish. More than just a preview, an effective thesis statement acts as a roadmap guiding listeners through your thought process.

Giving them that quick glimpse into what they can anticipate helps keep their attention locked in.

As you craft this central hub of information, understand that its purpose is not limited to informing alone—it could be meant also to persuade or entertain based on what you aim for with your general purpose statement.

This clear focus is pivotal—it shapes each aspect of your talk, easing understanding for the audience while setting basic goals for yourself throughout the speech-making journey. So whether you are rallying rapturous applause or instigating intellectual insight, remember—your thesis statement holds power like none other! Its clarity and strength can transition between being valuable sidekicks in introductions towards becoming triumphant heroes by concluding lines.

Identifying the main idea to develop a thesis statement

In crafting a compelling speech, identifying the main idea to develop a thesis statement acts as your compass. This process is a crucial step in speech preparation that steers you towards specific purpose.

Think of your central idea as the seed from which all other elements in your speech will grow.

To pinpoint it, start by brainstorming broad topics that interest or inspire you. From this list, choose one concept that stands out and begin to narrow it down into more specific points. It’s these refined ideas that form the heart of your thesis statement — essentially acting as signposts leading the audience through your narrative journey.

Crafting an effective thesis statement requires clarity and precision. This means keeping it concise without sacrificing substance—a tricky balancing act even for public speaking veterans! The payoff though? A well-developed thesis statement provides structure to amplifying your central idea and guiding listeners smoothly from point A to B.

It’s worth noting here: just like every speaker has their own unique style, there are multiple ways of structuring a thesis statement too. But no matter how you shape yours, ensuring it resonates with both your overarching message and audience tastes will help cement its effectiveness within your broader presentation context.

Analyzing the audience to tailor the thesis statement

Audience analysis is a crucial first step for every public speaker. This process involves adapting the message to meet the audience’s needs, a thoughtful approach that considers cultural diversity and ensures clear communication.

Adapting your speech to resonate with your target audience’s interests, level of understanding, attitudes and beliefs can significantly affect its impact.

Crafting an appealing thesis statement hinges on this initial stage of audience analysis. As you analyze your crowd, focus on shaping a specific purpose statement that reflects their preferences yet stays true to the objective of your speech—capturing your main idea in one or two impactful sentences.

This balancing act demands strategy; however, it isn’t impossible. Taking into account varying aspects such as culture and perceptions can help you tailor a well-received thesis statement. A strong handle on these elements allows you to select language and tones best suited for them while also reflecting the subject at hand.

Ultimately, putting yourself in their shoes helps increase message clarity which crucially leads to acceptance of both you as the speaker and your key points – all embodied within the concise presentation of your tailor-made thesis statement.

Brainstorming techniques to generate thesis statement ideas

Leveraging brainstorming techniques to generate robust thesis statement ideas is a power move in public speaking. This process taps into the GAP model, focusing on your speech’s Goals, Audience, and Parameters for seamless target alignment.

Dive into fertile fields of thought and let your creativity flow unhindered like expert David Zarefsky proposes.

Start by zeroing in on potential speech topics then nurture them with details till they blossom into fully-fledged arguments. It’s akin to turning stones into gems for the eye of your specific purpose statement.

Don’t shy away from pushing the envelope – sometimes out-of-the-box suggestions give birth to riveting speeches! Broaden your options if parameters are flexible but remember focus is key when aiming at narrow targets.

The beauty lies not just within topic generation but also formulation of captivating informative or persuasive speech thesis statements; both fruits harvested from a successful brainstorming session.

So flex those idea muscles, encourage intellectual growth and watch as vibrant themes spring forth; you’re one step closer to commanding attention!

Remember: Your thesis statement is the heartbeat of your speech – make it strong using brainstorming techniques and fuel its pulse with evidence-backed substance throughout your presentation.

Narrowing down the thesis statement to a specific topic

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your speech requires narrowing down a broad topic to a specific focus that can be effectively covered within the given time frame. This step is crucial as it helps you maintain clarity and coherence throughout your presentation.

Start by brainstorming various ideas related to your speech topic and then analyze them critically to identify the most relevant and interesting points to discuss. Consider the specific purpose of your speech and ask yourself what key message you want to convey to your audience.

By narrowing down your thesis statement, you can ensure that you address the most important aspects of your chosen topic, while keeping it manageable and engaging for both you as the speaker and your audience.

Choosing the appropriate language and tone for the thesis statement

Crafting the appropriate language and tone for your thesis statement is a crucial step in developing a compelling speech. Your choice of language and tone can greatly impact how your audience perceives your message and whether they are engaged or not.

When choosing the language for your thesis statement, it’s important to consider the level of formality required for your speech. Are you speaking in a professional setting or a casual gathering? Adjusting your language accordingly will help you connect with your audience on their level and make them feel comfortable.

Additionally, selecting the right tone is essential to convey the purpose of your speech effectively. Are you aiming to inform, persuade, or entertain? Each objective requires a different tone: informative speeches may call for an objective and neutral tone, persuasive speeches might benefit from more assertive language, while entertaining speeches can be lighthearted and humorous.

Remember that clarity is key when crafting your thesis statement’s language. Using concise and straightforward wording will ensure that your main idea is easily understood by everyone in the audience.

By taking these factors into account – considering formality, adapting to objectives, maintaining clarity – you can create a compelling thesis statement that grabs attention from the start and sets the stage for an impactful speech.

Incorporating evidence to support the thesis statement

Incorporating evidence to support the thesis statement is a critical aspect of delivering an effective speech. As public speakers, we understand the importance of backing up our claims with relevant and credible information.

When it comes to incorporating evidence, it’s essential to select facts, examples, and opinions that directly support your thesis statement.

To ensure your evidence is relevant and reliable, consider conducting thorough research on the topic at hand. Look for trustworthy sources such as academic journals, respected publications, or experts in the field.

By choosing solid evidence that aligns with your message, you can enhance your credibility as a speaker.

When presenting your evidence in the speech itself, be sure to keep it concise and clear. Avoid overwhelming your audience with excessive details or data. Instead, focus on selecting key points that strengthen your argument while keeping their attention engaged.

Remember that different types of evidence can be utilized depending on the nature of your speech. You may include statistical data for a persuasive presentation or personal anecdotes for an informative talk.

The choice should reflect what will resonate best with your audience and effectively support your thesis statement.

By incorporating strong evidence into our speeches, we not only bolster our arguments but also build trust with our listeners who recognize us as reliable sources of information. So remember to choose wisely when including supporting material – credibility always matters when making an impact through public speaking.

Avoiding common mistakes when developing a thesis statement

Crafting an effective thesis statement is vital for public speakers to deliver a compelling and focused speech. To avoid common mistakes when developing a thesis statement , it is essential to be aware of some pitfalls that can hinder the impact of your message.

One mistake to steer clear of is having an incomplete thesis statement. Ensure that your thesis statement includes all the necessary information without leaving any key elements out. Additionally, avoid wording your thesis statement as a question as this can dilute its potency.

Another mistake to watch out for is making statements of fact without providing evidence or support. While it may seem easy to write about factual information, it’s important to remember that statements need to be proven and backed up with credible sources or examples.

To create a more persuasive argument, avoid using phrases like “I believe” or “I feel.” Instead, take a strong stance in your thesis statement that encourages support from the audience. This will enhance your credibility and make your message more impactful.

By avoiding these common mistakes when crafting your thesis statement, you can develop a clear, engaging, and purposeful one that captivates your audience’s attention and guides the direction of your speech effectively.

Key words: Avoiding common mistakes when developing a thesis statement – Crafting a thesis statement – Effective thesis statements – Public speaking skills – Errors in the thesis statement – Enhancing credibility

Revising the thesis statement to enhance clarity and coherence

Revising the thesis statement is a crucial step in developing a clear and coherent speech. The thesis statement serves as the main idea or argument that guides your entire speech, so it’s important to make sure it effectively communicates your message to the audience.

To enhance clarity and coherence in your thesis statement, start by refining and strengthening it through revision . Take into account any feedback you may have received from others or any new information you’ve gathered since initially developing the statement.

Consider if there are any additional points or evidence that could further support your main idea.

As you revise, focus on clarifying the language and tone of your thesis statement. Choose words that resonate with your audience and clearly convey your point of view. Avoid using technical jargon or overly complicated language that might confuse or alienate listeners.

Another important aspect of revising is ensuring that your thesis statement remains focused on a specific topic. Narrow down broad ideas into more manageable topics that can be explored thoroughly within the scope of your speech.

Lastly, consider incorporating evidence to support your thesis statement. This could include statistics, examples, expert opinions, or personal anecdotes – whatever helps strengthen and validate your main argument.

By carefully revising your thesis statement for clarity and coherence, you’ll ensure that it effectively conveys your message while capturing the attention and understanding of your audience at large.

Testing the thesis statement to ensure it meets the speech’s objectives.

Testing the thesis statement is a crucial step to ensure that it effectively meets the objectives of your speech. By testing the thesis statement , you can assess its clarity, relevance, and impact on your audience.

One way to test your thesis statement is to consider its purpose and intent. Does it clearly communicate what you want to achieve with your speech? Is it concise and specific enough to guide your content?.

Another important aspect of testing the thesis statement is analyzing whether it aligns with the needs and interests of your audience. Consider their background knowledge, values, and expectations.

Will they find the topic engaging? Does the thesis statement address their concerns or provide valuable insights?.

In addition to considering purpose and audience fit, incorporating supporting evidence into your speech is vital for testing the effectiveness of your thesis statement. Ensure that there is relevant material available that supports your claim.

To further enhance clarity and coherence in a tested thesis statement, revise it if necessary based on feedback from others or through self-reflection. This will help refine both language choices and overall effectiveness.

By thoroughly testing your thesis statement throughout these steps, you can confidently develop a clear message for an impactful speech that resonates with your audience’s needs while meeting all stated objectives.

1. What is a thesis statement in public speaking?

A thesis statement in public speaking is a concise and clear sentence that summarizes the main point or argument of a speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience, guiding them through the speech and helping them understand its purpose.

2. How do I develop an effective thesis statement for a speech?

To develop an effective thesis statement for a speech, start by identifying your topic and determining what specific message you want to convey to your audience. Then, clearly state this message in one or two sentences that capture the main idea of your speech.

3. Why is it important to have a strong thesis statement in public speaking?

Having a strong thesis statement in public speaking helps you stay focused on your main argument throughout the speech and ensures that your audience understands what you are trying to communicate. It also helps establish credibility and authority as you present well-supported points related to your thesis.

4. Can my thesis statement change during my speech preparation?

Yes, it is possible for your thesis statement to evolve or change during the preparation process as you gather more information or refine your ideas. However, it’s important to ensure that any changes align with the overall purpose of your speech and still effectively guide the content and structure of your presentation.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

8.2 The Topic, General Purpose, Specific Purpose, and Thesis

Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a general purpose, a specific purpose statement, and crafting a central idea, or thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about and for what purpose you will speak. These decisions will influence and guide the entire speechwriting process, so it is wise to think carefully and critically during these beginning stages.

Understanding the General Purpose

Before any work on a speech can be done, the speaker needs to understand the general purpose of the speech. The general purpose is what the speaker hopes to accomplish and will help guide in the selection of a topic. The instructor generally provides the general purpose for a speech, which falls into one of three categories. A general purpose to inform would mean that the speaker is teaching the audience about a topic, increasing their understanding and awareness, or providing new information about a topic the audience might already know. Informative speeches are designed to present the facts, but not give the speaker’s opinion or any call to action. A general purpose to persuade would mean that the speaker is choosing the side of a topic and advocating for their side or belief. The speaker is asking the audience to believe in their stance, or to take an action in support of their topic. A general purpose to entertain often entails short speeches of ceremony, where the speaker is connecting the audience to the celebration. You can see how these general purposes are very different. An informative speech is just facts, the speaker would not be able to provide an opinion or direction on what to do with the information, whereas a persuasive speech includes the speaker’s opinions and direction on what to do with the information. Before a speaker chooses a topic, they must first understand the general purpose.

Selecting a Topic

Generally, speakers focus on one or more interrelated topics—relatively broad concepts, ideas, or problems that are relevant for particular audiences. The most common way that speakers discover topics is by simply observing what is happening around them—at their school, in their local government, or around the world. Opportunities abound for those interested in engaging speech as a tool for change. Perhaps the simplest way to find a topic is to ask yourself a few questions, including:

- What important events are occurring locally, nationally, and internationally?

- What do I care about most?

- Is there someone or something I can advocate for?

- What makes me angry/happy?

- What beliefs/attitudes do I want to share?

- Is there some information the audience needs to know?

Students speak about what is interesting to them and their audiences. What topics do you think are relevant today? There are other questions you might ask yourself, too, but these should lead you to at least a few topical choices. The most important work that these questions do is to locate topics within your pre-existing sphere of knowledge and interest. Topics should be ideas that interest the speaker or are part of their daily lives. In order for a topic to be effective, the speaker needs to have some credibility or connection to the topic; it would be unfair to ask the audience to donate to a cause that the speaker has never donated to. There must be a connection to the topic for the speaker to be seen as credible. David Zarefsky (2010) also identifies brainstorming as a way to develop speech topics, a strategy that can be helpful if the questions listed above did not yield an appropriate or interesting topic. Brainstorming involves looking at your daily activities to determine what you could share with an audience. Perhaps if you work out regularly or eat healthy, you could explain that to an audience, or demonstrate how to dribble a basketball. If you regularly play video games, you may advocate for us to take up video games or explain the history of video games. Anything that you find interesting or important might turn into a topic. Starting with a topic you are already interested in will make writing and presenting your speech a more enjoyable and meaningful experience. It means that your entire speechwriting process will focus on something you find important and that you can present this information to people who stand to benefit from your speech. At this point, it is also important to consider the audience before choosing a topic. While we might really enjoy a lot of different things that could be topics, if the audience has no connection to that topic, then it wouldn’t be meaningful for the speaker or audience. Since we always have a diverse audience, we want to make sure that everyone in the audience can gain some new information from the speech. Sometimes, a topic might be too complicated to cover in the amount of time we have to present, or involve too much information then that topic might not work for the assignment, and finally if the audience can not gain anything from a topic then it won’t work. Ultimately, when we choose a topic we want to pick something that we are familiar with and enjoy, we have credibility and that the audience could gain something from. Once you have answered these questions and narrowed your responses, you are still not done selecting your topic. For instance, you might have decided that you really care about breeds of dogs. This is a very broad topic and could easily lead to a dozen different speeches. To resolve this problem, speakers must also consider the audience to whom they will speak, the scope of their presentation, and the outcome they wish to achieve.

Formulating the Purpose Statements

By honing in on a very specific topic, you begin the work of formulating your purpose statement. In short, a purpose statement clearly states what it is you would like to achieve. Purpose statements are especially helpful for guiding you as you prepare your speech. When deciding which main points, facts, and examples to include, you should simply ask yourself whether they are relevant not only to the topic you have selected, but also whether they support the goal you outlined in your purpose statement. The general purpose statement of a speech may be to inform, to persuade, to celebrate, or to entertain. Thus, it is common to frame a specific purpose statement around one of these goals. According to O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein, a specific purpose statement “expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve” (2004). The specific purpose is a single sentence that states what the audience will gain from this speech, or what will happen at the end of the speech. The specific purpose is a combination of the general purpose and the topic and helps the speaker to focus in on what can be achieved in a short speech.

To go back to the topic of a dog breed, the general purpose might be to inform, a specific purpose might be: To inform the audience about how corgis became household pets. If the general purpose is to persuade the specific purpose might be: to persuade the audience that dog breeds deemed “dangerous” should not be excluded from living in the cities. In short, the general purpose statement lays out the broader goal of the speech while the specific purpose statement describes precisely what the speech is intended to do. The specific purpose should focus on the audience and be measurable, if I were to ask the audience before I began the speech how many people know how corgis became household pets, they could raise their hand, and if I ask at the end of my speech how many people know how corgis became household pets, I should see a lot more hands. The specific purpose is the “so what” of the speech, it helps the speaker focus on the audience and take a bigger idea of a topic and narrow it down to what can be accomplished in a short amount of time.

Writing the Thesis Statement

The specific purpose statement is a tool that you will use as you write your speech, but it is unlikely that it will appear verbatim in your speech. Instead, you will want to convert the specific purpose statement into a central idea, or thesis statement that you will share with your audience. Just like in a written paper, where the thesis comes in the first part of the paper, in a speech, the thesis comes within the first few sentences of the speech. The thesis must be stated and tells the audience what to expect in this speech. A thesis statement may encapsulate the main idea of a speech in just a sentence or two and be designed to give audiences a quick preview of what the entire speech will be about. The thesis statement should be a single, declarative statement followed by a separate preview statement. If you are a Harry Potter enthusiast, you may write a thesis statement (central idea) the following way using the above approach: J.K. Rowling is a renowned author of the Harry Potter series with a Cinderella-like story of a rise to fame.

Writing the Preview Statement

A preview statement (or series of statements) is a guide to your speech. This is the part of the speech that literally tells the audience exactly what main points you will cover. If you were to get on any freeway, there would be a green sign on the side of the road that tells you what cities are coming up—this is what your preview statement does; it tells the audience what points will be covered in the speech. Best of all, you would know what to look for! So, if we take our J.K Rowling example, the thesis and preview would look like this: J.K. Rowling is a renowned author of the Harry Potter series with a Cinderella-like rags-to-riches story. First, I will tell you about J.K. Rowling’s humble beginnings. Then, I will describe her personal struggles as a single mom. Finally, I will explain how she overcame adversity and became one of the richest women in the United Kingdom.

Writing the Body of Your Speech

Once you have finished the important work of deciding what your speech will be about, as well as formulating the purpose statement and crafting the thesis, you should turn your attention to writing the body of your speech. The body of your speech consists of 3–4 main points that support your thesis and help the audience to achieve the specific purpose. Creating main points helps to chunk the information you are sharing with your audience into an easy-to-understand organization. Choosing your main points will help you focus in on what information you want to share with the audience in order to prove your thesis. Since we can’t tell the audience everything about our topic, we need to choose our main points to make sure we can share the most important information with our audience. All of your main points are contained in the body, and normally this section is prepared well before you ever write the introduction or conclusion. The body of your speech will consume the largest amount of time to present, and it is the opportunity for you to elaborate on your supporting evidence, such as facts, statistics, examples, and opinions that support your thesis statement and do the work you have outlined in the specific purpose statement. Combining these various elements into a cohesive and compelling speech, however, is not without its difficulties, the first of which is deciding which elements to include and how they ought to be organized to best suit your purpose.

clearly states what it is you would like to achieve

“expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve” (O'Hair, Stewart, & Rubenstein, 2004)

single, declarative sentence that captures the essence or main point of your entire presentation

It’s About Them: Public Speaking in the 21st Century Copyright © 2022 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3 Putting It Together: Steps to Complete Your Introduction

Learning objectives.

- Clearly identify why an audience should listen to a speaker.

- Discuss how you can build your credibility during a speech.

- Understand how to write a clear thesis statement.

- Design an effective preview of your speech’s content for your audience.

Erin Brown-John – puzzle – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Once you have captured your audience’s attention, it’s important to make the rest of your introduction interesting, and use it to lay out the rest of the speech. In this section, we are going to explore the five remaining parts of an effective introduction: linking to your topic, reasons to listen, stating credibility, thesis statement, and preview.

Link to Topic

After the attention-getter, the second major part of an introduction is called the link to topic. The link to topic is the shortest part of an introduction and occurs when a speaker demonstrates how an attention-getting device relates to the topic of a speech. Often the attention-getter and the link to topic are very clear. For example, if you look at the attention-getting device example under historical reference above, you’ll see that the first sentence brings up the history of the Vietnam War and then shows us how that war can help us understand the Iraq War. In this case, the attention-getter clearly flows directly to the topic. However, some attention-getters need further explanation to get to the topic of the speech. For example, both of the anecdote examples (the girl falling into the manhole while texting and the boy and the filberts) need further explanation to connect clearly to the speech topic (i.e., problems of multitasking in today’s society).

Let’s look at the first anecdote example to demonstrate how we could go from the attention-getter to the topic.

In July 2009, a high school girl named Alexa Longueira was walking along a main boulevard near her home on Staten Island, New York, typing in a message on her cell phone. Not paying attention to the world around her, she took a step and fell right into an open manhole. This anecdote illustrates the problem that many people are facing in today’s world. We are so wired into our technology that we forget to see what’s going on around us—like a big hole in front of us.

In this example, the third sentence here explains that the attention-getter was an anecdote that illustrates a real issue. The fourth sentence then introduces the actual topic of the speech.

Let’s now examine how we can make the transition from the parable or fable attention-getter to the topic: