The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

NCPR Podcasts

More podcasts from NPR

More from NPR

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

Why do you do what you do? What is the engine that keeps you up late at night or gets you going in the morning? Where is your happy place? What stands between you and your ultimate dream?

Heavy questions. One researcher believes that writing down the answers can be decisive for students.

He co-authored a paper that demonstrates a startling effect: nearly erasing the gender and ethnic minority achievement gap for 700 students over the course of two years with a short written exercise in setting goals.

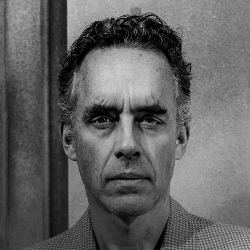

Jordan Peterson teaches in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. For decades, he has been fascinated by the effects of writing on organizing thoughts and emotions.

Experiments going back to the 1980s have shown that "therapeutic" or "expressive" writing can reduce depression, increase productivity and even cut down on visits to the doctor.

"The act of writing is more powerful than people think," Peterson says.

Most people grapple at some time or another with free-floating anxiety that saps energy and increases stress. Through written reflection, you may realize that a certain unpleasant feeling ties back to, say, a difficult interaction with your mother. That type of insight, research has shown, can help locate, ground and ultimately resolve the emotion and the associated stress.

At the same time, "goal-setting theory" holds that writing down concrete, specific goals and strategies can help people overcome obstacles and achieve.

'It Turned My Life Around'

Recently, researchers have been getting more and more interested in the role that mental motivation plays in academic achievement — sometimes conceptualized as "grit" or "growth mindset" or "executive functioning."

Peterson wondered whether writing could be shown to affect student motivation. He created an undergraduate course called Maps of Meaning . In it, students complete a set of writing exercises that combine expressive writing with goal-setting.

Students reflect on important moments in their past, identify key personal motivations and create plans for the future, including specific goals and strategies to overcome obstacles. Peterson calls the two parts "past authoring" and "future authoring."

"It completely turned my life around," says Christine Brophy, who, as an undergraduate several years ago, was battling drug abuse and health problems and was on the verge of dropping out. After taking Peterson's course at the University of Toronto, she changed her major. Today she is a doctoral student and one of Peterson's main research assistants.

In an early study at McGill University in Montreal, the course showed a powerful positive effect with at-risk students, reducing the dropout rate and increasing academic achievement.

Peterson is seeking a larger audience for what he has dubbed "self-authoring." He started a for-profit company and is selling a version of the curriculum online. Brophy and Peterson have found a receptive audience in the Netherlands.

At the Rotterdam School of Management, a shortened version of self-authoring has been mandatory for all first-year students since 2011. (These are undergraduates — they choose majors early in Europe).

The latest paper, published in June, compares the performance of the first complete class of freshmen to use self-authoring with that of the three previous classes.

Overall, the "self-authoring" students greatly improved the number of credits earned and their likelihood of staying in school. And after two years, ethnic and gender-group differences in performance among the students had all but disappeared.

The ethnic minorities in question made up about one-fifth of the students. They are first- and second-generation immigrants from non-Western backgrounds — Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

While the history and legacy of racial oppression are different from that in the United States, the Netherlands still struggles with large differences in wealth and educational attainment among majority and minority groups.

'Zeroes Are Deadly'

At the Rotterdam school, minorities generally underperformed the majority by more than a third, earning on average eight fewer credits their first year and four fewer credits their second year. But for minority students who had done this set of writing exercises, that gap dropped to five credits the first year and to just one-fourth of one credit in the second year.

How could a bunch of essays possibly have this effect on academic performance? Is this replicable?

Melinda Karp is the assistant director for staff and institutional development at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. She leads studies on interventions that can improve college completion. She calls Peterson's paper "intriguing." But, she adds, "I don't believe there are silver bullets for any of this in higher ed."

Peterson believes that formal goal-setting can especially help minority students overcome what's often called "stereotype threat," or, in other words, to reject the damaging belief that generalizations about ethnic-group academic performance will apply to them personally.

Karp agrees. "When you enter a new social role, such as entering college as a student, the expectations aren't always clear." There's a greater risk for students who may be academically underprepared or who lack role models. "Students need help not just setting vague goals but figuring out a plan to reach them."

The key for this intervention came at crunch time, says Peterson. "We increased the probability that students would actually take their exams and hand in their assignments." The act of goal-setting helped them overcome obstacles when the stakes were highest. "You don't have to be a genius to get through school; you don't even have to be that interested. But zeroes are deadly."

Karp has a theory for how this might be working. She says you often see at-risk students engage in self-defeating behavior "to save face."

"If you aren't sure you belong in college, and you don't hand in that paper," she explains, "you can say to yourself, 'That's because I didn't do the work, not because I don't belong here.' "

Writing down their internal motivations and connecting daily efforts to blue-sky goals may have helped these young people solidify their identities as students.

Brophy is testing versions of the self-authoring curriculum at two high schools in Rotterdam, and monitoring their psychological well-being, school attendance and tendency to procrastinate.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/ .

Beacon Hill weighing how to prevent campaign-season AI deepfakes

GBH cuts staff and programming

They save lives, but they can't buy a house. First responders hit by Cape and Islands housing crisis

Massachusetts libraries are boosting their mission with new hires: Social workers

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

Why do you do what you do? What is the engine that keeps you up late at night or gets you going in the morning? Where is your happy place? What stands between you and your ultimate dream?

Heavy questions. One researcher believes that writing down the answers can be decisive for students.

He co-authored a paper that demonstrates a startling effect: nearly erasing the gender and ethnic minority achievement gap for 700 students over the course of two years with a short written exercise in setting goals.

Jordan Peterson teaches in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. For decades, he has been fascinated by the effects of writing on organizing thoughts and emotions.

Experiments going back to the 1980s have shown that "therapeutic" or "expressive" writing can reduce depression, increase productivity and even cut down on visits to the doctor.

"The act of writing is more powerful than people think," Peterson says.

Most people grapple at some time or another with free-floating anxiety that saps energy and increases stress. Through written reflection, you may realize that a certain unpleasant feeling ties back to, say, a difficult interaction with your mother. That type of insight, research has shown, can help locate, ground and ultimately resolve the emotion and the associated stress.

At the same time, "goal-setting theory" holds that writing down concrete, specific goals and strategies can help people overcome obstacles and achieve.

'It Turned My Life Around'

Recently, researchers have been getting more and more interested in the role that mental motivation plays in academic achievement — sometimes conceptualized as "grit" or "growth mindset" or "executive functioning."

Peterson wondered whether writing could be shown to affect student motivation. He created an undergraduate course called Maps of Meaning . In it, students complete a set of writing exercises that combine expressive writing with goal-setting.

Students reflect on important moments in their past, identify key personal motivations and create plans for the future, including specific goals and strategies to overcome obstacles. Peterson calls the two parts "past authoring" and "future authoring."

"It completely turned my life around," says Christine Brophy, who, as an undergraduate several years ago, was battling drug abuse and health problems and was on the verge of dropping out. After taking Peterson's course at the University of Toronto, she changed her major. Today she is a doctoral student and one of Peterson's main research assistants.

In an early study at McGill University in Montreal, the course showed a powerful positive effect with at-risk students, reducing the dropout rate and increasing academic achievement.

Peterson is seeking a larger audience for what he has dubbed "self-authoring." He started a for-profit company and is selling a version of the curriculum online. Brophy and Peterson have found a receptive audience in the Netherlands.

At the Rotterdam School of Management, a shortened version of self-authoring has been mandatory for all first-year students since 2011. (These are undergraduates — they choose majors early in Europe).

The latest paper, published in June, compares the performance of the first complete class of freshmen to use self-authoring with that of the three previous classes.

Overall, the "self-authoring" students greatly improved the number of credits earned and their likelihood of staying in school. And after two years, ethnic and gender-group differences in performance among the students had all but disappeared.

The ethnic minorities in question made up about one-fifth of the students. They are first- and second-generation immigrants from non-Western backgrounds — Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

While the history and legacy of racial oppression are different from that in the United States, the Netherlands still struggles with large differences in wealth and educational attainment among majority and minority groups.

'Zeroes Are Deadly'

At the Rotterdam school, minorities generally underperformed the majority by more than a third, earning on average eight fewer credits their first year and four fewer credits their second year. But for minority students who had done this set of writing exercises, that gap dropped to five credits the first year and to just one-fourth of one credit in the second year.

How could a bunch of essays possibly have this effect on academic performance? Is this replicable?

Melinda Karp is the assistant director for staff and institutional development at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. She leads studies on interventions that can improve college completion. She calls Peterson's paper "intriguing." But, she adds, "I don't believe there are silver bullets for any of this in higher ed."

Peterson believes that formal goal-setting can especially help minority students overcome what's often called "stereotype threat," or, in other words, to reject the damaging belief that generalizations about ethnic-group academic performance will apply to them personally.

Karp agrees. "When you enter a new social role, such as entering college as a student, the expectations aren't always clear." There's a greater risk for students who may be academically underprepared or who lack role models. "Students need help not just setting vague goals but figuring out a plan to reach them."

The key for this intervention came at crunch time, says Peterson. "We increased the probability that students would actually take their exams and hand in their assignments." The act of goal-setting helped them overcome obstacles when the stakes were highest. "You don't have to be a genius to get through school; you don't even have to be that interested. But zeroes are deadly."

Karp has a theory for how this might be working. She says you often see at-risk students engage in self-defeating behavior "to save face."

"If you aren't sure you belong in college, and you don't hand in that paper," she explains, "you can say to yourself, 'That's because I didn't do the work, not because I don't belong here.' "

Writing down their internal motivations and connecting daily efforts to blue-sky goals may have helped these young people solidify their identities as students.

Brophy is testing versions of the self-authoring curriculum at two high schools in Rotterdam, and monitoring their psychological well-being, school attendance and tendency to procrastinate.

Early results are promising, she says: "It helps students understand what they really want to do."

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.4: The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives Links to an external site

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 14106

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/07/10/419202925/the-writing-assignment-that-changes-lives

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

NPR calls Jordan Peterson’s self-authoring the writing assignment that changes lives :

Experiments going back to the 1980s have shown that “therapeutic” or “expressive” writing can reduce depression, increase productivity and even cut down on visits to the doctor. “The act of writing is more powerful than people think,” Peterson says. [...] Recently, researchers have been getting more and more interested in the role that mental motivation plays in academic achievement — sometimes conceptualized as “grit” or “growth mindset” or “executive functioning.” Peterson wondered whether writing could be shown to affect student motivation. He created an undergraduate course called Maps of Meaning . In it, students complete a set of writing exercises that combine expressive writing with goal-setting. Students reflect on important moments in their past, identify key personal motivations and create plans for the future, including specific goals and strategies to overcome obstacles. Peterson calls the two parts “past authoring” and “future authoring.” “It completely turned my life around,” says Christine Brophy, who, as an undergraduate several years ago, was battling drug abuse and health problems and was on the verge of dropping out. After taking Peterson’s course at the University of Toronto, she changed her major. Today she is a doctoral student and one of Peterson’s main research assistants. In an early study at McGill University in Montreal, the course showed a powerful positive effect with at-risk students, reducing the dropout rate and increasing academic achievement. Peterson is seeking a larger audience for what he has dubbed “self-authoring.” He started a for-profit company and is selling a version of the curriculum online. Brophy and Peterson have found a receptive audience in the Netherlands. At the Rotterdam School of Management, a shortened version of self-authoring has been mandatory for all first-year students since 2011. (These are undergraduates — they choose majors early in Europe). The latest paper, published in June, compares the performance of the first complete class of freshmen to use self-authoring with that of the three previous classes. Overall, the “self-authoring” students greatly improved the number of credits earned and their likelihood of staying in school. And after two years, ethnic and gender-group differences in performance among the students had all but disappeared. The ethnic minorities in question made up about one-fifth of the students. They are first- and second-generation immigrants from non-Western backgrounds — Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Posted in Education | 4 Comments »

This entry was posted on Tuesday, January 24th, 2017 at 3:46 pm and is filed under Education . You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

4 Responses to “The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives”

Positive thinkers have been extolling written affirmations and success journals and gratitude journals since the 19th century.

Positive thinkers are not always happy with the results of positive thinking diaries.

If this research adds anything new, I know a whole lot of less-than-enthusiastic positive thinkers who will be willing to put a lot of effort into this.

He’s an interesting guy. I’ve been watching his Maps of Meaning lectures on Youtube. Very good. Some people say they learned a lot or it changed their lives. I’m not learning a huge amount new but the new stuff is very high quality.

His new year’s message http://jordanbpeterson.com/2016/12/new-years-letter/ contains a lot of stuff that I wouldn’t normally take too seriously, but since it’s coming from him I give it more consideration. Same goes for this “Authoring” suite. I’d want to see more before I paid for it though.

Spandrell has been covering him recently: https://bloodyshovel.wordpress.com/2017/01/23/jordan-peterson/ https://bloodyshovel.wordpress.com/2016/12/22/jordan-peterson-on-truth/

The writing assignment costs $30, and it’s basically a self-help book with less information. It gives you a bunch of quizzes and lets you pick 2 to 10 interesting items. And then it gives you the same three questions for each item: 1 – What happened to cause a crisis? 2 – What could you have done different in that specific crisis? 3 – In general, how can you be better?

There’s no analysis, no answers other than the answers you provide for yourself.

Leave a Reply

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <strike> <strong>

Recent Comments

- Jim : Felix: “Jim, what are the important, unread books you have in mind?” You may have heard of the Stamp Acts, one of the key precipitating overreaches of the British Parliament into the American Colonies. What you may not have heard of is that that body “gave jurisdiction over Stamp Act offenses to the admiralty courts, which followed civil-law rather than common-law procedures.” Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36, 47 (2004). Thus, offenses against the revenue laws (including...

- Phileas Frogg : Audacity is a fickle currency. One day she can purchase you the impossible, and the next a hangman’s noose. There’s really no telling which.

- Gaikokumaniakku : Possibly relevant: https://www.yahoo.com/ne ws/britain-says-developi ng-radio-wave-132346318. html

- Gaikokumaniakku : Possibly relevant: https://www.laserfocuswo rld.com/lasers-sources/a rticle/14211951/testing- 50-kw-lasers-in-weapon-s ystems I did a few searches trying to find good news about long-range electrolasers, but I only found short-range devices suitable for clearing IEDs.

- Shadeburst : The three thousand feet sounds highly suspect. A formation of WW2 Forts would drop all its bombs simultaneously on a signal from the lead bombardier. As the formation was spread out across the sky, side- as well as long-ways, and the bombs were released over a period of a few seconds (during which time the formation had traveled a thousand feet) the intention was to bomb an area, not a pickle-barrel pinpoint. In addition, Europe being Europe, the target might often be obscured by cloud, in...

- Gaikokumaniakku : Also, the cars may or may not be well-designed but the charging stations apparently were designed to be convenient for copper thieves.

- Gaikokumaniakku : “Musk, in contrast, spent more time walking assembly lines than he did walking around the design studio. ‘The brain strain of designing the car is tiny compared to the brain strain of designing the factory,’ he says.” I have heard rumors that Tesla cars cannot survive car washes or mud puddles unless they are first put into “car wash mode.” If such rumors are true, maybe the factory is well-designed but the car is badly designed.

- M. Mack : Elon sounds pretty “Old School,” like Henry Ford and his right hand man “Cast Iron” Charlie Sorensen. Between them, they defined the auto industry, with the moving assembly line, one worker doing one task, and setting up the River Rouge plant to be vertically integrated, from the iron ore being turned into steel and iron in blast furnaces on site all the way to the cars rolling off the end of the line, and close to every step in between.

- Elmer : Few decades back Marlin made the Supergoose, a 10-gauge bolt action shotgun with a 36-inch extra full choke barrel, took 3 1/2 inch 10-gauge shells, had a 2-round box magazine. Heavy, ugly, slow rate of fire unless you knew how to run a bolt gun, but it brought down geese at distances a 12-gauge could only dream about. Might be pretty good against drones. About the same time Ithaca made a 10 gauge 3 round semi-auto shotgun, also took 3 1/2 unch shells; IIRC, a 32 inch full choke barrel was...

- Phileas Frogg : Blanket censorship of internal criticisms and critiques, without respect to their efficacy, is a sure sign of a social group lacking the internal social flexibility to withstand a serious external threat to their cohesion. The only thing keeping them together is the static nature of their circumstances; change that and there is a high likelihood of failure. Such a group is ossified and ready to break. I hesitate to put a number on it, but I’m willing to wager that a shockingly small...

- Lu An Li : For McChuck and thank you. Makes sense. Unity of command.

- McChuck : Just as there can only be one king, and army may only have a single commander. Command, by its very nature, rests upon a single head. Two commanders will constantly butt heads, confusing the troops and adding to the natural chaos of war. They often end up fighting each other more than the enemy. Even if they have the best of intentions, two commanders will inadvertently misdirect each others’ troops and interfere with each others’ plans.

- Lucklucky : Maybe bad translation. But i think it means it is better to have 1 good and 1 bad than 2 good to be able to choose.

- Lu An Li : “I believe it would be better to have one bad general than to have two good ones.” Someone explain this to me.

- Gaikokumaniakku : After the lemur bites the millipede, it sprays its toxic secretion, which the lemur then rubs all over its fur. Research suggests that there is a practical purpose to this: the benzoquinone secretion functions as a natural pesticide and wards off malaria-carrying mosquitos. The secretion also acts as a narcotic, which causes the lemur to salivate profusely and enter a state of intoxication.

- Freddo : If you want to reach the mass market you need an equally sized megaphone (or a lot of luck). A push by Oprah will do it, Joe Rogan probably to a lesser extend. Amazons algorithm and star rating have been wokified to the point of uselessness; goodreads fast approaching the same point. Aspiring writers get the advice to build their own internet presence, but that of course is a lot of work by itself. I like the concept of a book bomb where a group of like-minded authors do a push of a new novel.

- Felix : And, no mention of romance novels. Aren’t they supposed to be 50% or better of books sold? Sure, there are big name romance writers. A lot of them, if the grocery store is indicative. But. No mention?

- Felix : Jim, what are the important, unread books you have in mind?

- Albion : As someone who has published a couple of books (independently) on-line I can testify no one reads them much. In a way not a problem as it was more of a hobby, and there is a certain pleasure in getting words down in roughly the right order. But in terms of return for effort, it is barely a penny an hour in all likelihood. As they say, don’t give up the day job. Equally I can go to a library or bookshop, and while there tens of thousands of books available, I know I don’t want to read...

- Phileas_Frogg : Jim, Your comment is obviously true, and yet the religion of those Ellis Islanders has managed to intellectually persevere, and indeed dominate, in intellectually rigorous fields, and in particular at the most intellectually rarified branch of the government (SCOTUS is 6 Catholics, 2 Protestants, 1 Jew). It is an odd paradox. I suspect we’re seeing a selection process take place where the less intelligent, curious, and literate Catholics are ending up non-Catholic, while the more...

- Alan Moore (21)

- Andrew Bisset (27)

- Animals (684)

- Antikythera (6)

- Arnold Kling (239)

- Autism (27)

- Bruce Bueno de Mesquita (12)

- Bruce Charlton (19)

- Business (1970)

- Charles Munger (9)

- Chernobyl (7)

- Economics (2023)

- Education (1399)

- Edward Banfield (15)

- Edward Luttwak (33)

- Eric Falkenstein (51)

- Ethanol (35)

- Farewell to Alms (10)

- Fitness (601)

- Flight of the Conchords (10)

- Fred Reed (25)

- Games (433)

- George Fitzhugh (19)

- Henry George (9)

- Hilaire du Berrier (7)

- John Derbyshire (40)

- Lee Harris (22)

- Linguistics (161)

- Malcolm Gladwell (21)

- Martial Arts (368)

- Classics of Fantasy (17)

- Mencius Moldbug (209)

- Myth of the Rational Voter (9)

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb (42)

- Nikola Tesla (6)

- Paul Graham (78)

- Peter Thiel (12)

- Philip K. Dick (6)

- Policy (5445)

- Robert Heinlein (48)

- Robert Kaplan (76)

- Rory Miller (41)

- Roy Dunlap (89)

- Science (3075)

- Serious Play (17)

- Singapore (38)

- Steve Blank (29)

- Steve Ditko (4)

- Technology (2191)

- Theodore Dalrymple (61)

- Theory of Constraints (19)

- Thomas Schelling (14)

- Uncategorized (1606)

- Urbanism (400)

- Viktor Suvorov (19)

- Crime (622)

- Panzer Battles (22)

- Weapons (821)

- May 2024 (21)

- April 2024 (26)

- March 2024 (27)

- February 2024 (28)

- January 2024 (30)

- December 2023 (27)

- November 2023 (27)

- October 2023 (33)

- September 2023 (30)

- August 2023 (34)

- July 2023 (31)

- June 2023 (32)

- May 2023 (32)

- April 2023 (30)

- March 2023 (30)

- February 2023 (32)

- January 2023 (33)

- December 2022 (28)

- November 2022 (26)

- October 2022 (29)

- September 2022 (22)

- August 2022 (32)

- July 2022 (20)

- June 2022 (23)

- May 2022 (25)

- April 2022 (41)

- March 2022 (45)

- February 2022 (22)

- January 2022 (29)

- December 2021 (29)

- November 2021 (30)

- October 2021 (23)

- September 2021 (17)

- August 2021 (27)

- July 2021 (29)

- June 2021 (30)

- May 2021 (33)

- April 2021 (30)

- March 2021 (41)

- February 2021 (32)

- January 2021 (32)

- December 2020 (29)

- November 2020 (30)

- October 2020 (31)

- September 2020 (30)

- August 2020 (33)

- July 2020 (34)

- June 2020 (27)

- May 2020 (29)

- April 2020 (29)

- March 2020 (52)

- February 2020 (57)

- January 2020 (50)

- December 2019 (44)

- November 2019 (27)

- October 2019 (29)

- September 2019 (30)

- August 2019 (29)

- July 2019 (49)

- June 2019 (59)

- May 2019 (61)

- April 2019 (57)

- March 2019 (55)

- February 2019 (36)

- January 2019 (43)

- December 2018 (38)

- November 2018 (36)

- October 2018 (32)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (42)

- July 2018 (30)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (41)

- April 2018 (30)

- March 2018 (32)

- February 2018 (36)

- January 2018 (59)

- December 2017 (42)

- November 2017 (46)

- October 2017 (59)

- September 2017 (39)

- August 2017 (45)

- July 2017 (49)

- June 2017 (41)

- May 2017 (41)

- April 2017 (35)

- March 2017 (43)

- February 2017 (37)

- January 2017 (54)

- December 2016 (35)

- November 2016 (55)

- October 2016 (55)

- September 2016 (39)

- August 2016 (56)

- July 2016 (46)

- June 2016 (58)

- May 2016 (64)

- April 2016 (56)

- March 2016 (41)

- February 2016 (36)

- January 2016 (55)

- December 2015 (61)

- November 2015 (57)

- October 2015 (61)

- September 2015 (61)

- August 2015 (70)

- July 2015 (66)

- June 2015 (76)

- May 2015 (73)

- April 2015 (70)

- March 2015 (78)

- February 2015 (57)

- January 2015 (73)

- December 2014 (84)

- November 2014 (77)

- October 2014 (91)

- September 2014 (103)

- August 2014 (101)

- July 2014 (101)

- June 2014 (83)

- May 2014 (107)

- April 2014 (90)

- March 2014 (79)

- February 2014 (73)

- January 2014 (87)

- December 2013 (93)

- November 2013 (77)

- October 2013 (94)

- September 2013 (93)

- August 2013 (77)

- July 2013 (89)

- June 2013 (71)

- May 2013 (67)

- April 2013 (71)

- March 2013 (77)

- February 2013 (52)

- January 2013 (50)

- December 2012 (45)

- November 2012 (57)

- October 2012 (49)

- September 2012 (55)

- August 2012 (53)

- July 2012 (70)

- June 2012 (74)

- May 2012 (68)

- April 2012 (57)

- March 2012 (42)

- February 2012 (69)

- January 2012 (80)

- December 2011 (80)

- November 2011 (67)

- October 2011 (99)

- September 2011 (102)

- August 2011 (75)

- July 2011 (84)

- June 2011 (76)

- May 2011 (79)

- April 2011 (90)

- March 2011 (77)

- February 2011 (106)

- January 2011 (81)

- December 2010 (90)

- November 2010 (69)

- October 2010 (83)

- September 2010 (60)

- August 2010 (121)

- July 2010 (108)

- June 2010 (130)

- May 2010 (114)

- April 2010 (125)

- March 2010 (140)

- February 2010 (121)

- January 2010 (137)

- December 2009 (87)

- November 2009 (134)

- October 2009 (117)

- September 2009 (115)

- August 2009 (160)

- July 2009 (129)

- June 2009 (99)

- May 2009 (108)

- April 2009 (128)

- March 2009 (120)

- February 2009 (159)

- January 2009 (115)

- December 2008 (108)

- November 2008 (114)

- October 2008 (99)

- September 2008 (139)

- August 2008 (125)

- July 2008 (133)

- June 2008 (123)

- May 2008 (107)

- April 2008 (146)

- March 2008 (126)

- February 2008 (94)

- January 2008 (84)

- December 2007 (139)

- November 2007 (121)

- October 2007 (114)

- September 2007 (120)

- August 2007 (117)

- July 2007 (160)

- June 2007 (99)

- May 2007 (124)

- April 2007 (97)

- March 2007 (64)

- February 2007 (99)

- January 2007 (112)

- December 2006 (113)

- November 2006 (103)

- October 2006 (91)

- September 2006 (99)

- August 2006 (112)

- July 2006 (128)

- June 2006 (114)

- May 2006 (80)

- April 2006 (166)

- March 2006 (161)

- February 2006 (166)

- January 2006 (132)

- December 2005 (94)

- November 2005 (115)

- October 2005 (105)

- September 2005 (129)

- August 2005 (83)

- July 2005 (81)

- June 2005 (126)

- May 2005 (85)

- April 2005 (80)

- March 2005 (96)

- February 2005 (91)

- January 2005 (126)

- December 2004 (71)

- November 2004 (115)

- October 2004 (94)

- September 2004 (64)

- August 2004 (86)

- July 2004 (92)

- June 2004 (83)

- May 2004 (85)

- April 2004 (119)

- March 2004 (91)

- February 2004 (31)

- January 2004 (63)

- December 2003 (59)

- November 2003 (56)

- October 2003 (56)

- September 2003 (53)

- August 2003 (35)

- July 2003 (36)

- June 2003 (46)

- May 2003 (72)

- April 2003 (43)

- March 2003 (68)

- February 2003 (141)

- January 2003 (52)

Isegoria is proudly powered by WordPress Entries (RSS) and Comments (RSS) .

Self Authoring

Self Authoring Suite

Past Authoring, Present Authoring, Future Authoring

What is Self Authoring?

The Self-Authoring Suite is a series of online writing programs that collectively help you explore your past, present and future.

For a limited time, get qqqqqq for qqqqqq (qqqqqq% off) using qqqqqqq code qqqqqqq

When you buy the Self Authoring 2 for 1 Special, you will receive all the Self Authoring exercises for yourself. You will also receive a voucher that you can email to a friend.

The Self Authoring Suite provides access to all four of the Self Authoring exercises: the Present Authoring - Faults, Present Authoring - Virtues, the Future Authoring, and the Past Authoring.

People who spend time writing carefully about themselves become happier, less anxious and depressed and physically healthier. They become more productive, persistent and engaged in life. This is because thinking about where you came from, who you are and where you are going helps you chart a simpler and more rewarding path through life.

The Past Authoring Program helps you remember, articulate and analyze key positive and negative life experiences.

The Present Authoring Program has two modules. The first helps you understand and rectify your personality faults. The second helps you understand and develop your personality virtues.

The Future Authoring Program helps you envision a meaningful, healthy and productive future, three to five years down the road, and to develop a detailed, implementable plan to make that future a reality.

Put your past to rest! Understand and improve your present personality! Design the future you want to live! The Self Authoring Suite will improve your life.

Plan for your Ideal Future

Understand your past, discover your true self.

Tried and Tested

The Self Authoring programs have been used in many different settings, and the results have been overwhelmingly positive.

Improve performance

Students who use the Self Authoring programs often see an increase in school performance, and are less likely to drop out of classes.

Improve relationships

Find out what you want from both your friendships, and your intimate relationships with the Self Authoring Suite.

The Self Authoring programs will help identify your highest goals, and allow you to discover the tools necessary to achieve them.

What does the research say?

Future Authoring has been used by over 10,000 people and has shown to help them achieve more, while alleviating anxiety about the future through a feeling of clarity of purpose and direction.

While most Future Authoring participants feel better about their future and generally achieve more towards their goals, there have been academic studies performed to demonstrate the effect of the Future Authoring program:

Four hundred students completed an abbreviated version of the Future Authoring program during freshman orientation at an undergraduate college. By the second semester, 27% of the class had dropped out, while only 14% of the group that had used Future Authoring had left the college.

Other university studies have shown that not only does Future Authoring help students avoid dropping out, but it also improves their performance in terms of grade point average and the number of credits earned.

We are a group of clinical and research psychologists from the University of Toronto and McGill University who are distributing tools that will improve psychological and physical health to interested individuals everywhere.

Jordan B. Peterson, Ph.d

Founder & Psychology Professor, UofT

Daniel M. Higgins, Ph.d

Founder, Head of Software Development

Robert O. Pihl, Ph.d

Founder, Psychology Professor, McGill

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

Why do you do what you do? What is the engine that keeps you up late at night or gets you going in the morning? Where is your happy place? What stands between you and your ultimate dream? NPR's feature on the Self Authoring Suite. Read more ...

Writing Benefits

Careful writing about traumatic or uncertain events, past, present or future, appears to produce a variety of benefits, physiological and psychological. Written accounts of trauma positively influence health. Read more ...

Please read the frequently asked questions & tips page if you run into any technical difficulties with the programs.

404 Not found

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

Why do you do what you do? What is the engine that keeps you up late at night or gets you going in the morning? Where is your happy place? What stands between you and your ultimate dream?

Heavy questions. One researcher believes that writing down the answers can be decisive for students.

He co-authored a paper that demonstrates a startling effect: nearly erasing the gender and ethnic minority achievement gap for 700 students over the course of two years with a short written exercise in setting goals.

Jordan Peterson teaches in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. For decades, he has been fascinated by the effects of writing on organizing thoughts and emotions.

Experiments going back to the 1980s have shown that "therapeutic" or "expressive" writing can reduce depression, increase productivity and even cut down on visits to the doctor.

"The act of writing is more powerful than people think," Peterson says.

Most people grapple at some time or another with free-floating anxiety that saps energy and increases stress. Through written reflection, you may realize that a certain unpleasant feeling ties back to, say, a difficult interaction with your mother. That type of insight, research has shown, can help locate, ground and ultimately resolve the emotion and the associated stress.

At the same time, "goal-setting theory" holds that writing down concrete, specific goals and strategies can help people overcome obstacles and achieve.

'It Turned My Life Around'

Recently, researchers have been getting more and more interested in the role that mental motivation plays in academic achievement — sometimes conceptualized as "grit" or "growth mindset" or "executive functioning."

Peterson wondered whether writing could be shown to affect student motivation. He created an undergraduate course called Maps of Meaning. In it, students complete a set of writing exercises that combine expressive writing with goal-setting.

Students reflect on important moments in their past, identify key personal motivations and create plans for the future, including specific goals and strategies to overcome obstacles. Peterson calls the two parts "past authoring" and "future authoring."

"It completely turned my life around," says Christine Brophy, who, as an undergraduate several years ago, was battling drug abuse and health problems and was on the verge of dropping out. After taking Peterson's course at the University of Toronto, she changed her major. Today she is a doctoral student and one of Peterson's main research assistants.

In an early study at McGill University in Montreal, the course showed a powerful positive effect with at-risk students, reducing the dropout rate and increasing academic achievement.

Peterson is seeking a larger audience for what he has dubbed "self-authoring." He started a for-profit company and is selling a version of the curriculum online. Brophy and Peterson have found a receptive audience in the Netherlands.

At the Rotterdam School of Management, a shortened version of self-authoring has been mandatory for all first-year students since 2011. (These are undergraduates — they choose majors early in Europe).

The latest paper, published in June, compares the performance of the first complete class of freshmen to use self-authoring with that of the three previous classes.

Overall, the "self-authoring" students greatly improved the number of credits earned and their likelihood of staying in school. And after two years, ethnic and gender-group differences in performance among the students had all but disappeared.

The ethnic minorities in question made up about one-fifth of the students. They are first- and second-generation immigrants from non-Western backgrounds — Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

While the history and legacy of racial oppression are different from that in the United States, the Netherlands still struggles with large differences in wealth and educational attainment among majority and minority groups.

'Zeroes Are Deadly'

At the Rotterdam school, minorities generally underperformed the majority by more than a third, earning on average eight fewer credits their first year and four fewer credits their second year. But for minority students who had done this set of writing exercises, that gap dropped to five credits the first year and to just one-fourth of one credit in the second year.

How could a bunch of essays possibly have this effect on academic performance? Is this replicable?

Melinda Karp is the assistant director for staff and institutional development at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. She leads studies on interventions that can improve college completion. She calls Peterson's paper "intriguing." But, she adds, "I don't believe there are silver bullets for any of this in higher ed."

Peterson believes that formal goal-setting can especially help minority students overcome what's often called "stereotype threat," or, in other words, to reject the damaging belief that generalizations about ethnic-group academic performance will apply to them personally.

Karp agrees. "When you enter a new social role, such as entering college as a student, the expectations aren't always clear." There's a greater risk for students who may be academically underprepared or who lack role models. "Students need help not just setting vague goals but figuring out a plan to reach them."

The key for this intervention came at crunch time, says Peterson. "We increased the probability that students would actually take their exams and hand in their assignments." The act of goal-setting helped them overcome obstacles when the stakes were highest. "You don't have to be a genius to get through school; you don't even have to be that interested. But zeroes are deadly."

Karp has a theory for how this might be working. She says you often see at-risk students engage in self-defeating behavior "to save face."

"If you aren't sure you belong in college, and you don't hand in that paper," she explains, "you can say to yourself, 'That's because I didn't do the work, not because I don't belong here.' "

Writing down their internal motivations and connecting daily efforts to blue-sky goals may have helped these young people solidify their identities as students.

Brophy is testing versions of the self-authoring curriculum at two high schools in Rotterdam, and monitoring their psychological well-being, school attendance and tendency to procrastinate.

Early results are promising, she says: "It helps students understand what they really want to do."

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

How Writing Down Specific Goals Can Empower You

Anya Kamenetz

This is one of the most popular pieces that ran on NPR Ed in the past year. Here's a brief update:

In 2016, the "self-authoring" curriculum will be tested at a school in the United States for the first time. Community High School, in Swannanoa, N.C., will test the program on 150 students in grades 11 and 12. This is an "alternative school" that receives students who have struggled elsewhere, due in part to issues like family substance abuse and homelessness.

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

Why do you do what you do? What is the engine that keeps you up late at night or gets you going in the morning? Where is your happy place? What stands between you and your ultimate dream?

Heavy questions. One researcher believes that writing down the answers can be decisive for students.

He co-authored a paper that demonstrates a startling effect: nearly erasing the gender and ethnic minority achievement gap for 700 students over the course of two years with a short written exercise in setting goals.

Jordan Peterson teaches in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. For decades, he has been fascinated by the effects of writing on organizing thoughts and emotions.

Experiments going back to the 1980s have shown that "therapeutic" or "expressive" writing can reduce depression, increase productivity and even cut down on visits to the doctor.

"The act of writing is more powerful than people think," Peterson says.

Most people grapple at some time or another with free-floating anxiety that saps energy and increases stress. Through written reflection, you may realize that a certain unpleasant feeling ties back to, say, a difficult interaction with your mother. That type of insight, research has shown, can help locate, ground and ultimately resolve the emotion and the associated stress.

At the same time, "goal-setting theory" holds that writing down concrete, specific goals and strategies can help people overcome obstacles and achieve.

'It Turned My Life Around'

Recently, researchers have been getting more and more interested in the role that mental motivation plays in academic achievement — sometimes conceptualized as "grit" or "growth mindset" or "executive functioning."

Peterson wondered whether writing could be shown to affect student motivation. He created an undergraduate course called Maps of Meaning. In it, students complete a set of writing exercises that combine expressive writing with goal-setting.

Students reflect on important moments in their past, identify key personal motivations and create plans for the future, including specific goals and strategies to overcome obstacles. Peterson calls the two parts "past authoring" and "future authoring."

"It completely turned my life around," says Christine Brophy, who, as an undergraduate several years ago, was battling drug abuse and health problems and was on the verge of dropping out. After taking Peterson's course at the University of Toronto, she changed her major. Today she is a doctoral student and one of Peterson's main research assistants.

In an early study at McGill University in Montreal, the course showed a powerful positive effect with at-risk students, reducing the dropout rate and increasing academic achievement.

Peterson is seeking a larger audience for what he has dubbed "self-authoring." He started a for-profit company and is selling a version of the curriculum online. Brophy and Peterson have found a receptive audience in the Netherlands.

At the Rotterdam School of Management, a shortened version of self-authoring has been mandatory for all first-year students since 2011. (These are undergraduates — they choose majors early in Europe).

The latest paper, published in June, compares the performance of the first complete class of freshmen to use self-authoring with that of the three previous classes.

Overall, the "self-authoring" students greatly improved the number of credits earned and their likelihood of staying in school. And after two years, ethnic and gender-group differences in performance among the students had all but disappeared.

The ethnic minorities in question made up about one-fifth of the students. They are first- and second-generation immigrants from non-Western backgrounds — Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

While the history and legacy of racial oppression are different from that in the United States, the Netherlands still struggles with large differences in wealth and educational attainment among majority and minority groups.

'Zeroes Are Deadly'

At the Rotterdam school, minorities generally underperformed the majority by more than a third, earning on average eight fewer credits their first year and four fewer credits their second year. But for minority students who had done this set of writing exercises, that gap dropped to five credits the first year and to just one-fourth of one credit in the second year.

How could a bunch of essays possibly have this effect on academic performance? Is this replicable?

Melinda Karp is the assistant director for staff and institutional development at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. She leads studies on interventions that can improve college completion. She calls Peterson's paper "intriguing." But, she adds, "I don't believe there are silver bullets for any of this in higher ed."

Peterson believes that formal goal-setting can especially help minority students overcome what's often called "stereotype threat," or, in other words, to reject the damaging belief that generalizations about ethnic-group academic performance will apply to them personally.

Karp agrees. "When you enter a new social role, such as entering college as a student, the expectations aren't always clear." There's a greater risk for students who may be academically underprepared or who lack role models. "Students need help not just setting vague goals but figuring out a plan to reach them."

The key for this intervention came at crunch time, says Peterson. "We increased the probability that students would actually take their exams and hand in their assignments." The act of goal-setting helped them overcome obstacles when the stakes were highest. "You don't have to be a genius to get through school; you don't even have to be that interested. But zeroes are deadly."

Karp has a theory for how this might be working. She says you often see at-risk students engage in self-defeating behavior "to save face."

"If you aren't sure you belong in college, and you don't hand in that paper," she explains, "you can say to yourself, 'That's because I didn't do the work, not because I don't belong here.' "

Writing down their internal motivations and connecting daily efforts to blue-sky goals may have helped these young people solidify their identities as students.

Brophy is testing versions of the self-authoring curriculum at two high schools in Rotterdam, and monitoring their psychological well-being, school attendance and tendency to procrastinate.

Early results are promising, she says: "It helps students understand what they really want to do."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

- Resource Collection

- State Resources

Community for Adult Educators

We've updated LINCS Courses. Please see the Course Guide for updated information on using the site.

- Public Groups

- Micro Groups

- Recent Activity

- Reading and Writing

- Discussions

The Writing Assigment that Changes Lives

Colleagues,

Researcher Jordan Peterson, in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto, has co-authored a paper "that demonstrates a startling effect: nearly erasing the gender and ethnic minority achievement gap for 700 students over the course of two years with a short written exercise in setting goals." Although this study took place with at-risk students in college, the approach may also be effective with adult basic skills learners. I wonder if you know of approaches like this in adult basic or adult secondary level education, or transition to college programs. If so, please tell us about them.

You will find more about this in an NPR.org article at http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/07/10/419202925/the-writing-assignment-that-changes-lives?utm_source=npr_newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=20150719&utm_campaign=mostemailed&utm_term=nprnews

David J. Rosen

- Log in or register to post comments

David, this paper provides a whole lot of grist for this writing and literacy mill. I appreciate the support offered for two practices, among others he discusses and that I have long advocated: (1) give students time to reflect, a rare occurrence in our active, fast-paced learning environments, and (2) have students write about what they know! Adding goal setting to the equation also adds a whole lot to the outcome!

There is a whole lot to consider in Peterson's work, which bridges disciplines very nicely to the benefit of developing writers. Thank you so much for sharing the resources and starting this conversation. Great stuff!

Leecy Wise [email protected]

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

The One Method That Changes Your—and All Students’—Writing

Science-based writing methods can achieve dramatic results..

Posted May 14, 2024 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- Why Education Is Important

- Find a Child Therapist

- A systematic writing framework offers a method for dramatically improving the teaching of writing.

- This method received only limited uptake, despite high-profile research publications and textbooks.

- A focus on writing style might have limited the method's impacts.

I remember spending hours commenting painstakingly on my students’ papers when I was a graduate student teaching in the Expository Writing Program at New York University. My students loved our classes, and they filled my sections and gave me terrific course evaluations. Yet I could see that their writing failed to change significantly over the course of the semester. I ended up feeling as if I should refund their money, haunted by the blunt instruments we had to teach writing.

As I’ve learned from directing five writing programs at three different universities, methods matter. When I reviewed comments on papers from instructors who taught in my programs, I discovered that the quantity and quality of comments on students’ papers made only a slight impact on writing outcomes. For instance, one notoriously lazy instructor took several weeks to return assignments and only used spelling and grammar checkers to automate comments. But his conscientious colleague made dozens of sharp observations about students’ arguments, paragraphs, and sentences. However, Mr. Conscientious’ students improved perhaps only 10% over Mr. Minimalist’s students. Even then, the differences stemmed from basic guidelines Mr. Conscientious insisted his students write to, which included providing context sentences at the outset of their essay introductions.

Educators have also poured resources into teaching writing, with increasing numbers of hours dedicated to teaching writing across primary, secondary, and higher education . Yet studies continue to find writing skills inadequate . In higher education, most universities require at least a year of writing-intensive courses, with many universities also requiring writing across the curriculum or writing in the disciplines to help preserve students’ writing skills. However, writing outcomes have remained mostly unchanged .

While pursuing my doctorate, I dedicated my research to figuring out how writing worked. As a graduate student also teaching part-time, I was an early convert to process writing. I also taught those ancient principles of logos, ethos, and pathos, as well as grammar and punctuation. Nevertheless, these frameworks only created a canvas for students’ writing. What was missing: how writers should handle words, sentence structure, and relationships between sentences.

Yet researchers published the beginnings of a science-based writing method over 30 years ago. George Gopen, Gregory Colomb, and Joseph Williams created a framework for identifying how to maximize the clarity, coherence, and continuity of writing. In particular, Gopen and Swan (1990) created a methodology for making scientific writing readable . This work should have been a revelation to anyone teaching in or directing a writing program. But, weirdly, comparatively few writing programs or faculty embraced this work, despite Williams, Colomb, and Gopen publishing both research and textbooks outlining the method and process.