The Design Argument for the Existence of God

by James R. Beebe

Dept. of Philosophy

University at Buffalo

Copyright ã 2002

Outline of Essay :

I. The Analogical Version of the Design Argument

II. Criticisms of the Analogical Version

A. No Experience of Cosmic Beginnings: A Disanalogy

B. Evil: A Harmful Analogy

C. Full-Blown Anthropomorphism

D. Begging the Question

III. The Inference to the Best Explanation Version of the Design Argument

A. Inference to the Best Explanation

B. The Data

C. Explaining the Data

D. Conditional Probability

IV. Objections and Replies

A. The Anthropic Principle

B. “Sometimes the Improbable Happens”

C. Non-deductive Inference

The design argument is the simplest, most straightforward argument for the existence of God. Unlike the cosmological argument, the design argument can be stated in a few, easy-to-understand steps. In a nutshell, the design argument claims that the fact that everything in nature seems to be put together in just the right manner suggests that an intelligent designer was responsible for its creation. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)—a strident critic of the design argument—recognized both its simplicity and its importance. He wrote, "This proof always deserves to be mentioned with respect. It is the oldest, the clearest, and the most accordant with the common reason of mankind" (Kant 1781/1965, A 623, B 651).

In the first section of this essay I will describe the most famous version of the design argument—William Paley’s argument by analogy. Analogical arguments are perhaps the weakest sort of arguments one can offer without committing an outright fallacy. As we will see in section II, the analogical version of the design argument has come in for some heavy fire over the years. A contemporary reformulation of the argument, which I will call the ‘Inference to the Best Explanation’ (IBE) version of the design argument, claims to be able to escape the criticisms that are leveled against the analogical version. The IBE version will be explained in section III. It eschews the analogical form of the first version and uses evidence from contemporary science to back up its claims.

William Paley (1743-1805), an Anglican priest whose textbooks were required reading at Cambridge until the twentieth-century, put forward the most famous version of the design argument in his book Natural Theology: or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity Collected from the Appearances of Nature . In his autobiography, Charles Darwin (1876/1958, p. 19) cites Paley’s book as one of his favorite undergraduate texts:

In order to pass the B.A. examination, it was also necessary to get up Paley’s Evidences of Christianity , and his Moral Philosophy . This was done in a thorough manner, and I am convinced that I could have written out the whole of the Evidences with perfect correctness, but not of course in the clear language of Paley. The logic of this book and, as I may add, of his Natural Theology , gave me as much delight as did Euclid. The careful study of these works, without attempting to learn any part by rote, was the only part of the academical course which, as I then felt, and as I still believe, was of the least use to me in the education of my mind. I did not at that time trouble myself about Paley’s premises; and taking these on trust, I was charmed and convinced by the long line of argumentation.

The only discussion of the design argument that might be more famous than Paley’s is David Hume’s (1711-1776) in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion . In this work Hume subjects the argument to severe criticism.

Paley famously begins his version of the argument by comparing the universe to a watch. Suppose, he says, that we come upon a watch while walking through the forest.

[W]hen we come to inspect the watch, we perceive... that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that, if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, if a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it.... This mechanism being observed,... the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use. (cited in Hick 1964, pp. 99-100)

Paley claims that the same can be said for the universe as a whole. It seems to show evidence of an intelligent designer as well. The parts of the universe have an order, complexity and simplicity that resemble the parts of a finely crafted, well-oiled machine. It seems, then, that the universe was fashioned by some kind of Divine Watchmaker.

To support the analogy between a finely crafted watch and the universe, defenders of the design argument typically put forward the following kinds of considerations. Consider the fact that the universe is constructed in a way that is conducive to life. There is just enough oxygen to support life on earth. If there were even a little less, the Earth’s atmosphere would not be able to support life as we know it. But if there were just a little bit more oxygen in the atmosphere, combustion would occur too easily and often and it would once again be difficult to sustain life in such conditions. Moreover, the Earth is just the right distance from the sun. If we were a little bit closer, the atmosphere would be too hot to sustain life; but if we were a little further away, plants would not receive enough energy from the sun to carry on photosynthesis—the primary process by which the sun’s energy is converted into life on Earth. These and other “fine-tuning” aspects of the universe suggest that there was an intelligent mind that intentionally brought these features into being. As Sir Isaac Newton put it, the “most beautiful system of the sun, planets and comets could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being” (from the General Scholium of Principia Mathematica ; cited in Leslie 1989, p. 25).

Defenders of the design argument need not rest content with pointing to large-scale features of the universe that suggest design. They can also point to the apparent design of many kinds of objects in the world. Take, for example, mammalian organs, such as the heart, kidney, brain or eye. Each of these has been given a certain function to perform and each has an amazing capacity to carry out that function.

We can summarize the analogical version of the design argument as follows:

1) Human artifacts are the products of intelligent design.

2) The universe resembles human artifacts.

3) Therefore, the universe is probably a product of intelligent design.

4) Therefore, the author of the universe is probably an intelligent being. (adapted from Plantinga 1990, p. 97)

We know that (1) is true on the basis of personal experience and testimony from reliable sources. We know that machines are always put together to serve certain purposes and that it takes careful planning and construction to make sure that each of the parts of a complicated machine work properly. So, when we see that mammalian organs—e.g., hearts, lungs, eyes, brains, etc.—have certain very specific functions that they perform by carrying rather complicated series of interactions, it is plausible to think that they, too, are the products of intelligent design.

The most famous criticisms of the analogical version of the design argument appear in David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion . According to Norman Kemp Smith (“Introduction” to Hume’s Dialogues, p. 3), “Hume’s destructive criticism of the argument was final and complete.” Smith’s sentiments are shared by many. As we will see, however, defenders of the IBE version of the design argument claim that Hume’s criticisms apply only to the analogical version of the argument and not to their own version.

Most of Hume’s criticisms center on the analogical aspect of the traditional design argument. The problem, according to Hume, is that the analogy in question is not as strong as it needs to be in order to succeed. The more the universe resembles an artifact, the stronger the argument will be; but the less the universe is like an artifact, the weaker it will be.

A. No Experience of Cosmic Beginnings: A Disanalogy

Hume points out there are many dissimilarities or disanologies that harm the theist’s case. One of the first things he notes is that there is a disanalogy between the kind of experience we have with respect to artifacts and the kind of experience we have with respect to the universe. We have a lot of experience with a wide range of artifacts, which includes a general idea about what kinds of artisans or craftspeople make artifacts. We know that artifacts are made by intelligent designers because we have observed designers making a variety of things on many occasions. However, we don’t know what usually makes universes. We simply have no experience with this kind of thing. As a result, Hume claims, we can’t be too confident that whatever was responsible for making the universe is going to be much like the designers we are familiar with.

B. Evil: A Harmful Analogy

Hume also argues that there are analogies that are detrimental to belief in a designer. He thinks the analogical design argument correctly notes that we generally infer properties about an artisan or manufacturer from properties we observe in their products. But he claims the argument ignores important facts about our world. For example, from the solid 24 karat gold, diamonds and precision timing of a Rolex watch, one can infer that the manufacturer has the highest commitment to quality. When one is faced with a defective product, one draws analogous but opposite conclusions. For example, I own a Soviet-era military watch with the KGB insignia on its face. At noon and midnight, the two hands of the watch should both be pointing straight up, but there are five degrees of separation between them. Moreover, it gains about eight minutes every day. I have been led to form rather negative conclusions about Soviet-era craftsmanship from the properties of this watch.

Hume notes that there seem to be imperfections in nature: cancer, AIDS, heart disease, famines, plagues, floods, and countless other tragedies. If God is a Divine Watchmaker, as Paley claimed, the world looks to be more like a Soviet watch than a Rolex. In other words, if we are going to infer by analogy characteristics of the Creator from characteristics of the creation, it doesn’t seem we can conclude that the Creator had to be perfect because the world is anything but perfect. In jest, Hume suggests that maybe the universe was created by a junior deity who is just learning the ropes of universe creation and didn’t get things quite right this time.

C. Full-Blown Anthropomorphism

Hume also asks, “While we’re in the business of arguing by analogy, what is to keep us from pursuing the analogy all the way to a full-blown anthropomorphism?” The theist wants to argue that, since every highly ordered, complex contrivance we encounter has an intelligent designer behind it, we can conclude that the world also has a designer behind it. Well, says Hume, every artifact we encounter also has a designer with toenails, a bellybutton, 46 chromosomes, teeth made out of calcium composites, a spleen, and bad breath in the morning. What’s stopping us from concluding that the creator of the universe has all of these features as well? Hume’s point is that the analogy upon which the traditional design argument is based supports other conclusions than the one the theist is seeking to support.

D. Begging the Question

Kelly James Clark (1990, p. 30) echoes some of Hume’s worries when he claims,

The connection between the first premise, that the world appears designed, and belief in God is so tight that some contend that the argument from design simply assumes what it is trying to prove: to countenance apparent cosmic design is already to be committed to a design -er.

Clark thinks that one must already believe in God before one can accept the first premise of the traditional design argument—viz., that the world appears to be designed. If you don’t think there is a cosmic designer, then you’re probably not going to look at the world and think “This world appears to be designed.” An argument that assumes from the start the very thing that is up for debate is said to ‘beg the question.’ Since Clark thinks the analogical design argument begs the question, he concludes that the argument fails to have any persuasive force.

While I think Hume’s criticisms for the most part succeed in hitting their mark, I think that Clark’s does not. Most (if not all) evolutionary theorists admit that biological organs appear to be designed, but they remain committed to the project of explaining apparent design without appealing to a designer. In other words, they do not deny the first premise that Clark finds so worrisome; they merely deny the inferences theists wish to draw from it.

In any case, the objections put forward in this section have convinced many people that the design argument fails miserably. However, in recent years there has been a renewal of interest in the design argument—from both philosophers and scientists—and this has led to an updated formulation of the argument.

The design argument can be reformulated so that it is not an analogical argument. Instead, it can be understood as an inference to the best explanation. This form of inference is common to both science and ordinary life. We start with a set of data that is initially surprising or unexplained, and we wonder what could explain it. As possible explanations pop into our minds, we evaluate the initial plausibility and simplicity of each explanation and see how well the explanations make sense of the data. J. P. Moreland (1994, p. 26) offers the following example of an ordinary inference to the best explanation.

Suppose I get a terrible stomachache. Then it dawns on me that I just ate a gallon and a half of ice cream, two bags of popcorn and a lot of candy on an empty stomach. A hypothesis suggests itself as the best explanation of the stomachache—it arose because of what I had just eaten. Other hypotheses may also suggest themselves, but I should adopt the explanation that best solves the problems for which it was postulated.

In what follows I will present an array of scientific data that, according to defenders of the IBE design argument, cries out for explanation. The facts described are extraordinarily improbable and unlikely to be the result of chance. After presenting the data, we will examine the suggestion that the best explanation for these unlikely occurrences is that a personal, transcendent Being of tremendous power and intelligence is directly responsible for purposefully bringing them about.

1. We can begin by considering the fact that the energy the Earth receives from the Sun is precisely the amount required to nurture life. According to Richard Brennan (1997, pp. 244-245),

The term used in science for this energy is the solar constant , which is defined as 1.99 calories of energy per minute per square centimeter. If Earth received much more or less than 2 calories per minute per square centimeter, the water of the oceans would be vapor or ice, leaving the planet with no liquid water or reasonable substitute in which life could evolve. It is only because Earth is 93 million miles away from a Sun that produces 5,600 million, million, million, million calories per minute that life is possible.

2. Brennan (1997, p. 245) continues,

For another example, it has been calculated that if Earth were just 5 million miles closer to the Sun, the intensity of the Sun’s rays would have broken apart water molecules in the atmosphere and eventually turned the planet into a dry and dusty wasteland. If Earth were only 1 million miles farther from the Sun, the cold would have frozen the ocean solid.

3. For there to be enough carbon around to support life, the strong nuclear force (the force that holds quarks together to form protons and neutrons and holds protons and neutrons together to form the nuclei of atoms) can be no more than 1% stronger or weaker than it is. Increasing its strength by 2% would block the formation of protons, so that there would either be no atoms at all or else stars would burn a billion billion times faster than our sun, thereby making it difficult to have an environment friendly to living organisms (Leslie 1989, p. 4). Increasing its strength by only 1% would result in all carbon being burned into oxygen (Leslie 1989, p. 35).

4. Decreasing the strong nuclear force by 5% would make it impossible for stars to burn (Leslie 1989, p.4).

5. If the force of electromagnetism were somewhat stronger, the amount of light given off by stars would be significantly lower. Main sequence stars (i.e., stars like our sun in the stable phase during which they spend most of their lifetimes and have their interior heat and radiation provided by nuclear fusion reactions near their centers) would be too cold to support life and would not contain any elements heavier than iron. It would also make protons repel one another strongly enough to prevent the existence of atoms (Leslie 1989, p. 4).

6. If the force of electromagnetism were slightly weaker, all main sequence stars would be very hot and short-lived blue stars. According to the physicist, P. C. W. Davies, changes in either electromagnetism or gravity by only one part in 10 40 would spell catastrophe for stars like the sun (Leslie 1989, p. 37).

7. Some of the basic forces of the universe also need to be finely-tuned to each other. Gravity is roughly 10 39 times weaker than electromagnetism. If it had been only 10 33 times weaker, stars would be a billion times less massive and would burn a million times faster (Leslie 1989, p. 5). If gravity were ten times less strong, stars and planets could probably not form at all (Leslie 1989, p. 39).

8. The opposite charges of electrons and protons perfectly balance each other. They are identical magnitudes. If there had been a difference between their charges even as small as one part in ten billion, scientists have calculated that no solid bodies could weigh more than one gram (Leslie 1989, p. 45).

9. The difference in mass between protons and neutrons is twice the mass of the electron, which is itself a very small quantity. If this were not so, then

all neutrons would have decayed into protons or else all protons would have changed irreversibly into neutrons. Either way, there would not be the couple of hundred stable types of atom on which chemistry and biology are based. (Leslie 1989, p. 5)

If all protons were changed irreversibly into neutrons, the universe would consist of nothing but neutron stars and black holes. (A neutron star is a kind of collapsed star that is immensely dense and is made mostly of neutrons. It is not the sort of star that could support life as we know it.)

10. According to William Lane Craig (Strobel 2000, p. 77), P. C. W. Davies concluded that the odds against the initial conditions being suitable for the formation of stars is a one followed by at least a thousand billion billion zeroes.

11. Davies also estimated that if the strength of gravity or of the weak force were changed by only one part in a ten followed by a hundred zeroes, life could never have developed (ibid.).

12. Craig (1990, p. 143) writes,

[Astronomer Fred] Hoyle and his colleague Wickramasinghe calculated the odds of the random formation of a single enzyme from amino acids anywhere on the earth’s surface as one in 10 20 . But that is only the beginning: “The trouble is that there are about two thousand enzymes, and the chance of obtaining them all in a random trial is only one part in (10 20 ) 20,000 = 10 40,000 , an outrageously small probability that could not be faced even if the whole universe consisted of organic soup.” And of course, the formation of enzymes is but one step in the formation of life. “Nothing has been said of the origin of DNA itself, nothing of DNA transcription to RNA, nothing of the origin of the program whereby cells organize themselves, nothing of mitosis and meiosis. These issues are too complex to set numbers to.” In the end, they conclude that the chances of life originating by random ordering of organic molecules is not sensibly different from zero.

13. J. P. Moreland (1987, p. 53) claims, “If the mass of a proton were increased by 0.2 percent, hydrogen would be unstable and life would not have formed.”

14. Brennan (1997, p. 246) writes,

If something called the fine structure constant (the square of the charge of the electron divided by the speed of light multiplied by Planck’s constant) were slightly different, atoms would not exist.

15. The fact that all of this fine tuning is distributed across enormous ranges makes it even more amazing that they should be found in just the right proportions. The strong nuclear force is roughly 100 times stronger than electromagnetism. Electromagnetism is itself some 10,000 billion billion billion times stronger than gravity (Leslie 1989, p. 6).

None of the foregoing evidence of the “fine-tuning” of the universe depends upon acceptance of the Big Bang theory of the origin of (the present state of) the universe and the cosmic timeline (spanning 15 billion years) that goes with it. Theists who think that the Big Bang is identical to the event of divine creation, however, can avail themselves of further evidence of the fine-tuning of the universe, some of which is described below. According to defenders of the IBE design argument, this evidence shows that even the theory of cosmic origin most widely accepted by atheist scientists strongly suggests that there was and is an Intelligent Designer behind the controls of the universe.

16. The rate of expansion of the universe immediately after the Big Bang had to be finely tuned. According to William Lane Craig (Strobel 2000, p. 77), Stephen Hawking, the world’s most famous living physicist, has calculated that if the rate of the universe’s expansion one second after the Big Bang had been smaller by even one part in a hundred thousand million million, the universe would have collapsed into a fireball.

17. If the rate of expansion were decreased by only one part in a million when the Big Bang was a second old, the universe would have recollapsed before temperatures fell below 10,000 degrees (i.e., before it could cool off enough for life to be able to form) (Leslie 1989, p. 29).

18. An increase of only one part in a million in the rate of the early universe’s expansion would have meant that the kinetic energy of expansion would have so dominated gravity that stars could not form (Leslie 1989, p. 29).

19. Had the weak nuclear force been slightly stronger, the Big Bang would have burned all hydrogen to helium. There would then be neither water nor long-lived stable stars, which are hydrogen-burning (Leslie 1989, p. 4).

20. The weakness of the weak force results in our sun burning its hydrogen slowly and gently for billions of years instead of blowing up like a bomb (Leslie 1989, p. 34).

21. Making the weak nuclear force slightly weaker would have destroyed all of the hydrogen, and the neutrons formed during the earliest stages of the universe would not have decayed into protons (Leslie 1989, p. 4). Without this neutron-decay, the universe would be made up of nothing but helium (Leslie 1989, p. 34).

22. P. C. W. Davies ( Other Worlds , London, 1980, pp. 168-169; cited in Leslie 1989, p. 28) claims that, because of all the parameters that had to be perfectly set before the Big Bang, the odds against a universe filled with stars is “one followed by a thousand billion billion zeros, at least.”

What should we make of all these facts? John Leslie (1989, p. 25) responds, “Our universe does seem remarkably tuned to Life’s needs.” Craig (1990, p. 143) writes,

The point is that within the wide range of universes permitted by the actual laws of physics, scarcely any are life-permitting, and those that are require incredible fine-tuning of the physical constants and quantities. In fact, Donald Page of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study has calculated the odds against the formation of our universe as one out of 10,000,000,000 124 , a number that exceeds all imagination.

To get a handle on how large this number is, consider the fact that there are estimated to be only 10 80 elementary particles in the universe (Craig 1990, p. 159). A universe that is inhospitable to life is extraordinarily more likely to have arisen than the one that we, in fact, find ourselves in. Craig (1990, p. 143) claims that the fine-tuning of the universe “cries out for explanation.” And an explanation immediately suggests itself: maybe this improbable “cosmic accident” wasn’t an accident after all. Keith Parsons (1990, p. 181), who is quite skeptical of the design argument, summarizes the conclusion of the argument nicely as follows.

[A] “finely tuned” universe is much more likely if there is a God than if there is not. In other words, it is implied that the cosmic “coincidences” that make possible a universe such as ours are extremely improbable unless they are the product of conscious design. Presumably, the conclusion is that since a “finely tuned” universe does in fact exist, its existence strongly confirms the existence of a conscious Designer—that is, God.

In other words, scientific discoveries of the infinitesimally small margin of error allowed in creating a universe capable of sustaining life support the central claim of theism: the universe was purposefully constructed by a personal, transcendent Being of tremendous power and intelligence.

D. Conditional Probability

Let me introduce some ideas from probability theory that can make clearer how the IBE version of the design argument is supposed to work.

1. Let ‘P(A ½ B)’ mean “the probability of A, given B.”

2. Let A = “You will die of cancer in the next ten years.”

3. Let B = “You are 20 years old, do not smoke, have no family history of cancer, and are very healthy.”

The value of ‘P(A ½ B)’ is called a ‘ conditional probability ’ value because we are asking what the probability is that A is true, on the condition that B is true. We are not simply asking what the probability of A is. We are asking about A’s likelihood in light of certain background assumptions.

According to the stipulations above, P(A ½ B) is the probability that you will die of cancer in the next ten years, given that you are 20 years old, do not smoke, have no family history of cancer, and are very healthy. The probability of that happening should be very low. Let’s replace B with the following conditions and see how the resulting probability values differ.

4. Let C = “You are a chain-smoking, 55-year old male.”

5. Let D = “You are a chain-smoking, 55-year old male who has been working in an asbestos factory for 35 years.”

Consider the value of P(A ½ C). It will obviously be a lot higher than P(A ½ B). And it’s a good bet that P(A ½ D) will be even higher.

In each of these cases, A remained the same. The only thing that changed was the set of background assumptions we used to determine the conditional probability value in question. We are now in a position to use the idea of conditional probability to achieve a better understanding of the IBE version of the design argument.

6. Let F = “There exists a finely-tuned, life-permitting universe.”

7. Let T = “There exists an all-powerful, all-knowing, perfectly good God who created the universe.”

8. Let Not-T = “There does not exist an all-powerful, all-knowing, perfectly good God who created the universe.”

Now consider the following probabilities.

9. P(F ½ T)

10. P(F ½ Not-T)

According to the scientists cited above, a conservative estimate of P(F ½ Not-T) is 1/10,000,000,000 124 . In other words, it is extraordinarily unlikely that the fine-tuning of the universe could have been brought about without the conscious planning of an intelligent designer.

Now think about the value of P(F ½ T). You can make an estimate of this probability, regardless of whether you are a theist or an atheist (or neither). I am simply asking what you think the probability of there being a a finely-tuned, life-permitting universe would be IF there were an all-powerful, all-knowing, perfectly good God who created the universe. Although I can’t give a precise number, it seems that the probability of P(F ½ T) would be extremely high. If there were a supremely powerful and intelligent God, that being could easily create a finely-tuned universe if he so desired. So, the difference between P(F ½ T) and P(F ½ Not-T) is enormous.

Why is this fact significant? Parsons (1990, pp. 193-194) writes,

It is the consequence of Bayes’ theorem [a theorem of probability theory that undergirds the currently accepted view about the confirmation of scientific theories]… that a given piece of evidence e confirms a hypothesis h if and only if e is more probable on h than on not- h . Hence, where h is theism and not- h is atheism and e comprises all of the “finely tuned” features of the universe, the “finely tuned” features of the universe confirm theism if and only if those features are more likely if God exists than if God does not exist.

In other words, since P(F ½ T) is tremendously higher than P(F ½ Not-T), facts about the fine-tuning the universe provide confirmation of the existence of God. The defender of the IBE version of the design argument concludes that it is more reasonable to believe that the universe was created by an Intelligent Designer than to believe that it spontaneously arose through chance.

The Inference to the Best Explanation version of the design argument sometimes encounters the following objection.

We should not be surprised that the universe is life-permitting. If it weren’t life-permitting, we wouldn’t be here to contemplate it. The fact that we are indeed here to contemplate it shows that it obviously must be life-permitting. Consequently, expressions of surprise at the fact that our universe is well suited for living things are inappropriate.

Part of this objection is obviously true, but another part of it is mistaken. The trivially true part is the claim that if our universe were not life-permitting, we living human beings would not be around to contemplate it. But it is a mistake to think that this fact neutralizes the need to explain why the universe is life-permitting.

Let me use the following example to make the point. Suppose I were brought before a firing squad made up of one hundred professional marksmen and that each of them was instructed to shoot one dozen rounds of ammunition at me. Now suppose that, after the smoke clears, it becomes evident that all 1200 bullets fired at me have missed their intended target. After a brief moment of elation, I will begin to wonder why I am still alive. Suppose I said to myself, “If they hadn’t all missed me then I shouldn’t be contemplating the matter so I mustn’t be surprised that they missed” (Leslie 1989, p. 108). Would that thought thoroughly satisfy my curiosity? Not by a long shot [sic]. I would begin to wonder whether they really intended to harm me. Were they instructed to miss me on purpose? Did someone load all of their rifles with blanks? Was this just a cruel birthday joke perpetrated by my wife? I might start looking around for the cameras from Spy TV or Candid Camera.

Similarly, merely pointing out that if the universe were not life-permitting, we would not be around to contemplate it does not satisfy our curiosity about the fine-tuning of the universe. We can still ask for an explanation of why these amazing and unlikely facts came to be.

B. “Sometimes the Improbable Happens”

A second objection that is often raised against the Inference to the Best Explanation version of the design argument goes like this:

Sometimes the improbable happens. For example, the fact that it is extraordinarily unlikely that any single person will win the Powerball lottery does not mean that no one will ever win. In fact, people whose odds of winning are vanishingly small win the Powerball lottery on a regular basis. Our reaction to the existence of an improbable, “finely-tuned,” life-permitting universe should be the same as our reaction to the news that somebody won the latest Powerball lottery: an uninterested yawn.

The defender of the IBE design argument will claim: a) that there is a confusion lurking behind these remarks; and b) once we clear up the confusion we will see that there are important disanalogies between the Powerball case and the case of a fine-tuned universe.

Suppose that in a certain lottery there are 100 million tickets sold and that one of these tickets will be chosen at random. If it is a fair lottery, then every ticket has an equal chance of winning. So, the probability that any particular ticket will bring riches to its bearer is 1/100,000,000. Now consider the probability that at least one of the 100 million lottery tickets that were sold will win. That probability is 1 (probabilities come in ranges of continuous values between zero and one). In other words, there is a 100% chance that one of the 100 million tickets sold will win.

According to the defender of the IBE design argument, we need to distinguish between the following two kinds of probability judgments:

1) The probability that a particular ticket will win.

2) The probability that some (i.e., at least one) ticket will win.

The value of (1) is 1/100,000,000. The value of (2) is 1. The reason we are unsurprised that somebody (or other) won the latest Powerball lottery is that the probability of somebody (or other) winning is 1. It’s a sure bet. But that doesn’t mean that we would not not be surprised if we held the winning ticket. We be very surprised because of the enormous odds against our winning.

Our winning, however, would not be completely mysterious to us. It’s not as if we would have no idea about how to explain how we won. Our knowledge of how lotteries work includes the knowledge that somebody has to win. We also know that winners in a fair lottery are selected through some kind of random process that gives everybody a fair shot. Knowledge of this process—even if it is vague and unspecific—keeps the fact of our winning from being an utterly mysterious, unexplainable fact.

The defender of the IBE design argument will maintain that the central problem with the current objection is that we do not know that the following is true:

4) The initial conditions of the present universe—e.g., the strengths of the four fundamental forces (the strong and weak nuclear forces, electromagnetism, and gravity), the masses of the fundamental particles, etc.—were the result of some kind of cosmic lottery. Out of the indefinitely large number of possible universes that could have been brought into being, ours was the one that just so happened—by pure chance—to be selected. If other universes had been selected, they would have collapsed into fireballs just a few seconds after being formed, while others would have been composed of only neutron stars and black holes. Still others would have consisted of nothing but electromagnetic radiation. Fortunately for us, none of these cosmic options were selected.

If we knew: a) that each possible universe had an equal probability of being actualized; b) that the probability that any particular universe would be selected was extremely small; and c) that at least one of them had to be selected; then it seems that we should show the same lack of surprise at the existence of our improbable but life-permitting universe that we do at the news of the latest lottery winner. The problem, however, is that we don’t know that our universe was the winner of a perfectly fair cosmic lottery. Lack of surprise is appropriate only when we have this knowledge. The fact that a life-permitting universe is extraordinarily improbable raises the suspicion that our universe wasn’t randomly selected after all.

Consider the following unlikely events and the “explanations” offered of these events.

i) The stones in one garden are randomly strewn about. In another garden the stones spell “Welcome to Wales by British Railways.” Regarding this example William Dembski (1998, p. xi) writes, “In both instances the precise arrangement of stones is vastly improbable. Indeed, any given arrangement of stones is but one of an almost infinite number of possible arrangements.” When asked for the best explanation of why one set of stones spells out an English sentence, someone replies, “Sometimes the improbable happens.”

ii) On several occasions during the last week, large pieces of scrap metal have fallen from above and nearly killed me. After each “accident” I turn around and see hurrying away from the scene one of my colleagues who has only a temporary contract with LSU but whose chances of being permanently hired by LSU would be greatly increased if I were out of the way. When detained and questioned by the police about why he always seemed to be present when pieces of scrap metal were falling near my head, my colleague simply replies “Sometimes the improbable happens.”

iii) I am brought before a firing squad made up of one hundred professional marksmen, each of whom is instructed to shoot one dozen rounds of ammunition at me. All 1200 bullets fired at me miss their intended target. When I ask someone for an explanation of this unlikely phenomenon, someone replies “Sometimes the improbable happens.”

iv) A silk merchant who, while trying to sell a silk gown, keeps his thumb over a hole in the silk the entire time his customer is looking at the gown. When his ruse is found out and he is asked to account for his behavior, he replies, “Every thumb must be somewhere. While it is improbable that my thumb should cover the hole the entire time, it is equally improbable that my thumb should be at any other location on the gown. Sometimes the improbable happens.”

v) The winner of January’s state lottery was the nephew of the Lottery Commissioner. The winner of the February lottery was the niece of the Lottery Commissioner. The winner of the state lottery in March was the Lottery Commissioner’s brother. The winner in April was the Lottery Commissioner’s ex-wife who, it is well known, has been trying to sue him for everything he’s got. When asked to account for this highly improbable string of events the Lottery Commissioner replies, “Sometimes the improbable happens.”

In none of these cases is the offered explanation even remotely satisfying or convincing. When we lack the positive knowledge that an event is the outcome of a fair lottery (or its probabilistic equivalent), we find ourselves unable to accept the answer that “Sometimes the improbable happens.” Our minds immediately turn to more likely scenarios that would explain the events in question. We automatically assume that British Railways intentionally arranged the set of stones to be a greeting. We think it highly likely that my colleague wants to bump me off so he can take my position. We think the firing squad must be a sham that serves some unseen purpose. We believe beyond any reasonable doubt that the location of the silk merchant’s thumb is due to greed and dishonesty rather than chance. And no one, I take it, would believe the Lottery Commissioner’s claim to innocence.

Recall the fine-tuned features of the universe cited above. The fact that all of these life-permitting features have come together is exceedingly improbable. The defender of the IBE design argument claims that this situation is more similar to the five cases listed above than to a fair lottery. As in the five cases above, they think we should be led to seek an explanation that does not appeal to mere chance. That explanation, they suggest, is that the universe was purposefully created by an Intelligent Designer.

A third objection to the Inference to the Best Explanation version of the design argument stems from the fact that the conclusion of the argument is not necessitated by its premises. Neal Gillespie (1979, pp. 83-84) has stated the objection as follows.

It has been generally agreed (then and since) that Darwin’s doctrine of natural selection effectively demolished William Paley’s classical design argument for the existence of God. By showing how blind and gradual adaptation could counterfeit the apparently purposeful design that Paley... and others had seen in the contrivances of nature, Darwin deprived their argument of the analogical inference that the evident purpose to be seen in the contrivances by which means and ends were related in nature was necessarily a function of mind.

Although Gillespie’s objection is aimed at Paley’s analogical version of the design argument, it can be modified to apply to the IBE version as well. Gillespie takes the design argument to task for thinking that the apparent design of the universe “was necessarily a function of [an intelligent, creative] mind.” But neither version of the design argument claims that the fine-tuned features of the universe are necessarily the product of intelligent design.

The IBE version merely claims that the hypothesis of intelligent design provides the best explanation for those features. In other words, the design argument does not purport to be a deductive argument, in which the truth of the premises necessitates the truth of the conclusion. Instead, it claims to offer a strong non-deductive argument for the hypothesis of intelligent design. Pointing out that the premises of a non-deductive argument do not necessitate its conclusion is like pointing out that Einstein’s general theory of relativity does not explain how to make a great Cabernet. That was never its intended purpose.

When dealing with non-deductive inferences, such as inferences to the best explanation, we must ask ourselves how much likelihood or palusibility is conferred upon the conclusion by the premises. If the IBE design argument is strong, then the facts about fine-tuning make the conclusion about an Intelligent Designer highly probable. If the argument is weak, then these facts do not make the Intelligent Design conclusion very probable at all. The key point is that, when dealing with non-deductive arguments, the issue is always one of probability rather than necessity . Strong, inductive arguments purport to make their conclusions probable. They do not claim to necessitate their conclusions. So, pointing out that they do not necessitate their premises cannot count as an objection against them. The IBE design argument is an inference to the best explanation; not an inference to the only possible explanation.

References

Brennan, Richard. 1997. Heisenberg Probably Slept Here: The Lives, Times, and Ideas of the Great Physicists of the 20th Century . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Clark, Kelly James. 1990. Return to Reason: A Critique of Enlightenment Evidentialism and a Defense of Reason and Belief in God . Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Craig, William Lane. 1990. “In Defense of Rational Theism.” In J. P. Moreland & Kai Nielsen (Eds.), Does God Exist? The Great Debate . Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Darwin, Charles. 1876/1958. Autobiography . Francis Darwin (Ed.). New York: Dover.

Dembski, William A. 1998. The Design Inference: Eliminating Chance Through Small Probabilities . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gillespie, Neal. 1979. Charles Darwin and the Problem of Creation . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hick, John. 1964. The Existence of God . New York: Macmillan.

Hume, David. 1779/1947. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion , edited with an introduction by N. K. Smith. New York: Macmillan.

Kant, Immanuel. 1781/1965. Critique of Pure Reason , trans. N. K. Smith. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Leslie, John. 1989. Universes . London: Routledge.

Moreland, J. P. 1987. Scaling the Secular City: A Defense of Christianity . Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House.

Moreland, J. P. 1990. “Yes! A Defense of Christianity.” In J. P. Moreland & Kai Nielsen (Eds.), Does God Exist? The Great Debate . Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Moreland, J. P. 1994. “Introduction.” In J. P. Moreland (Ed.), The Creation Hypothesis: Scientific Evidence for an Intelligent Designer . Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Parsons, Keith. 1990. “Is There a Case for Christian Theism?” In J. P. Moreland & Kai Nielsen (Eds.), Does God Exist? The Great Debate . Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Plantinga, Alvin. 1990. God and Other Minds: A Study of the Rational Justification of Belief in God , paperback edition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Strobel, Lee. 2000. The Case for Faith: A Journalist Investigates the Toughest Objections to Christianity . Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Evolutionary Concepts

- Open access

- Published: 24 October 2009

The Argument from Design: A Guided Tour of William Paley’s Natural Theology (1802)

- T. Ryan Gregory 1

Evolution: Education and Outreach volume 2 , pages 602–611 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

104k Accesses

4 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

According to the classic “argument from design,” observations of complex functionality in nature can be taken to imply the action of a supernatural designer, just as the purposeful construction of human artifacts reveals the hand of the artificer. The argument from design has been in use for millennia, but it is most commonly associated with the nineteenth century English theologian William Paley and his 1802 treatise Natural Theology , or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity , Collected from the Appearances of Nature . The book remains relevant more than 200 years after it was written, in large part because arguments very similar to Paley’s underlie current challenges to the teaching of evolution (indeed, his name arises with considerable frequency in associated discussions). This paper provides an accessible overview of the arguments presented by Paley in Natural Theology and considers them both in their own terms and in the context of contemporary issues.

I did not at that time [as a Cambridge theology student, 1827–1831] trouble myself about Paley’s premises; and taking these on trust, I was charmed and convinced by the long line of argumentation. (p. 59)

The old argument from design in nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered. (p. 87) Charles Darwin, Autobiography

Introduction

The “teleological argument,” better known as the “argument from design,” is the claim that the appearance of “design” in nature—such as the complexity, order, purposefulness, and functionality of living organisms—can only be explained by the existence of a “designer” (typically of the supernatural variety). In its most familiar manifestation, the argument from design involves drawing parallels between human-designed objects (e.g., telescopes, outboard motors) and biological counterparts with similar functional roles (e.g., eyes, bacterial flagella). The former are complex, often indivisibly so if they are to maintain their current function, clearly perform specific functions, and are known to have been the product of intentional design. The functional complexity of living organisms is far greater still, it is argued, and, therefore, must present even stronger evidence for the role of intelligent agency.

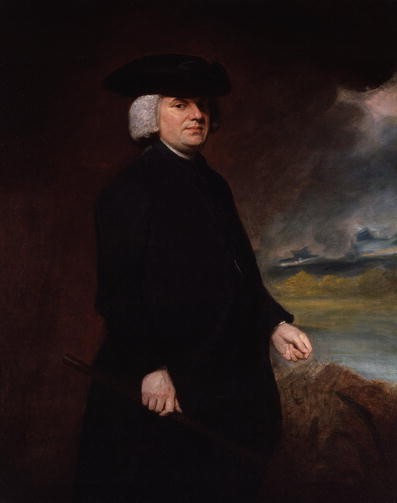

Though the basic premise of the teleological argument had been articulated by thinkers as far back as ancient Greece and Rome, today it is almost universally associated with the writings of one person: William Paley (Fig. 1 ). Paley was born in July 1743 in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, England. He was educated at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and was ordained a deacon in 1766 and soon thereafter a priest in Cambridge. He was appointed Archdeacon of Carlisle Cathedral in 1782 and awarded a Doctor of Divinity degree at Cambridge in 1795. He authored several successful theological works, the best-known being Natural Theology , or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity , Collected from the Appearances of Nature .

William Paley (1743–1805). Portrait circa 1790 by George Romney (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Natural Theology was published in 1802, only three years before Paley’s death on May 25, 1805. It was very successful, going through ten editions in the first four years alone (see Fyfe 2002 ). Despite being written in labyrinthine prose (by modern standards), Natural Theology remains an especially lucid exposition of the classic argument from design. This undoubtedly is one of the reasons that Paley’s name is most commonly linked with the design argument even though it was by no means original to him. Footnote 1

Darwin was influenced by Paley’s work, and some modern authors have cited it as an important example of pre-Darwinian “adaptationist” thinking (e.g., Dawkins 1986 ; Williams 1992 ; but see Gliboff 2000 ; McLaughlin 2008 ). Whatever its significance in the past, it is clear that Paley’s contribution continues to be of direct relevance in the current educational and political climate. Notably, Natural Theology was exhibit P-751 in the landmark 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover trial, which successfully challenged the constitutionality of promoting “intelligent design” in US public schools. Paley’s name appears more than 80 times in the trial testimony transcripts, and he is mentioned a further half a dozen times in Judge Jones’s decision. Footnote 2

In light of their continuing importance in current discourse, it is worth exploring the arguments presented in Paley’s classic treatise. This review is intended to provide a “guided tour” of Natural Theology , Footnote 3 giving the reader an abridged and annotated rendition of Paley’s widely referenced (but less often read) account of the argument from design.

Watches and Watchmakers

Natural Theology opens with the paragraph for which it is best (if not exclusively) known, in which Paley draws a contrast between a rock and a pocket watch: Footnote 4

In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone , and were asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer, that, for any thing I knew to the contrary, it had lain there for ever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for any thing I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? why is it not as admissible in the second case, as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz. that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e. g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that, if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order, than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it. (p.1–2)

Thus, in the very first passage of a book written more than two centuries ago, Paley encapsulates the core components of the argument from design—an argument that has been revived in much the same form by proponents of “intelligent design.” Specifically, Paley points out that the watch exhibits an irreducibly complex organization that was obviously constructed to perform a specific function. Remove or rearrange any of its intricate inner workings, and the watch becomes barely more effective at keeping time than the rock formerly dismissed with a kick. Footnote 5 From this, Paley concludes that

...the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker: that there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use. (p.3)

Furthermore, like modern proponents of the argument from design, Paley argues that one need not know any details of the designer’s identity or methods to conclude that an intelligent agent was involved:

Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed; all this being no more than what is true of some exquisite remains of ancient art, of some lost arts, and, to the generality of mankind, of the more curious productions of modern manufacture. (p.3–4)

Today’s neo-Paleyans must also concur with Paley that the watch’s delicate functionality could not be the product of chance, inherent “principles of order,” or laws of matter, nor merely an illusion of design. For Paley, this conclusion supersedes all other considerations and renders additional details largely superfluous. As he wrote,

Neither...would our observer be driven out of his conclusion, or from his confidence in its truth, by being told that he knew nothing at all about the matter. He knows enough for his argument: he knows the utility of the end: he knows the subserviency and adaptation of the means to the end. These points being known, his ignorance of other points, his doubts concerning other points, affect not the certainty of his reasoning. The consciousness of knowing little, need not beget a distrust of that which he does know. Footnote 6 (p.7)

However, given their aggressive resistance to the notion of suboptimality or nonfunction of biological structures, Footnote 7 it appears that many modern design proponents disagree with Paley’s subsequent assertions that neither imperfections nor ambiguous—or even nonexistent—functions refute the thesis of design for the origin of complex, (mostly) functional objects or organs. In this sense, Paley could be said to adhere more closely to the analogy with human artifacts than do many of his present-day counterparts:

Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion, that the watch sometimes went wrong, or that it seldom went exactly right. The purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer, might be evident, and in the case supposed would be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It is not necessary that a machine be perfect, in order to show with what design it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is, whether it were made with any design at all. (p.4–5)

Nor, thirdly, would it bring any uncertainty into the argument, if there were a few parts of the watch, concerning which we could not discover, or had not yet discovered, in what manner they conduced to the general effect; or even some parts, concerning which we could not ascertain, whether they conduced to that effect in any manner whatever. For...if by the loss, or disorder, or decay of the parts in question, the movement of the watch were found in fact to be stopped, or disturbed, or retarded, no doubt would remain in our minds as to the utility or intention of these parts, although we should be unable to investigate the manner according to which, or the connexion by which, the ultimate effect depended upon their action or assistance; and the more complex is the machine, the more likely is this obscurity to arise. Then, as to the second thing supposed, namely, that there were parts which might be spared, without prejudice to the movement of the watch, and that we had proved this by experiment,—these superfluous parts, even if we were completely assured that they were such, would not vacate the reasoning which we had instituted concerning other parts. The indication of contrivance remained, with respect to them, nearly as it was before. (p.5–6)

Continuing with the analogy of the watch, Paley next argues that one could not explain away the evidence of design even if the watch in hand had, through some exceptional mechanics, been produced by the self-replication of a parental watch. It matters not, according to Paley, whether any particular entity had been born of similar entities, as this accounts only for its existence and not its complex functional characteristics. Indeed, discovering the watch’s capacity to reproduce would only increase an observer’s admiration for its remarkable complexity:

No answer is given to this question, by telling us that a preceding watch produced it. There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance without a contriver; order without choice; arrangement, without any thing capable of arranging; subserviency and relation to a purpose, without that which could intend a purpose; means suitable to an end, and executing their office, in accomplishing that end, without the end ever having been contemplated, or the means accommodated to it. Arrangement, disposition of parts, subserviency of means to an end, relation of instruments to a use, imply the presence of intelligence and mind. No one, therefore, can rationally believe, that the insensible, inanimate watch, from which the watch before us issued, was the proper cause of the mechanism we so much admire in it;—could be truly said to have constructed the instrument, disposed its parts, assigned their office, determined their order, action, and mutual dependency, combined their several motions into one result, and that also a result connected with the utilities of other beings. All these properties, therefore, are as much unaccounted for, as they were before. (p.11–12)

Thus, Paley argues, no matter how many generations of watches beget watches (or, by obvious implication, organisms produce offspring or cells generate daughter cells), the specific, irreducible, and purposeful arrangement of watches’ inner workings can only be attributed to the action of intelligent agency.

The Cosmic Optician

Having established the connection between watches and watchmakers, Paley begins his third chapter by arguing that the principle applies equally to living organisms and their components—or indeed, more so, given that their degree of adaptive complexity is vastly greater. As he might have argued, human hands more thoroughly evince design than anything crafted by them.

As did many of his predecessors Footnote 8 (and followers), Paley considered eyes to provide a particularly illuminating exemplar of organic design: “there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it” (p. 18). Paley noted that telescopes and eyes rely on similar optical principles but that in fact vertebrate eyes are much more effective by virtue of their ability to adjust to different distances and brightness, in their well-developed protective features including eyelids and nictitating membranes, and by their capacity to correct for spherical aberration. In fact, he pointed out, telescope designers solved the problem of aberration by adopting features observed in biological lenses. In the absence of a natural explanation for their occurrence, eyes provided one of the best-known cases in support of the design argument. Darwin exposed the fallacy of this conclusion, and the efforts of countless scientists since then have resolved in increasingly fine detail how the various components of eyes are likely to have evolved. Footnote 9

In considering the eyes of different types of animals, Paley noted two critical facts: (1) that eyes differ according to the environment in which they are used to see and (2) that despite these differences, all vertebrate eyes are constructed according to the same basic physical plan. Eyes specialized for sight underwater, on land, or in the dark are not fundamentally different from each other; rather, they are modifications of a general theme: “Thus, in comparing the eyes of different kinds of animals, we see, in their resemblances and distinctions, one general plan laid down, and that plan varied with the varying exigencies to which it is to be applied” (p. 31). Today, this similarity amidst diversity is explained by the fact that all vertebrates share a common ancestor that was possessed of eyes and that specializations to different lifestyles have involved descent with modification of this ancestral organ.

The fact that all eyes have evolved through the modification of prior form and the cooption of preexisting components also explains some otherwise puzzling structural complications (not to mention features that are downright maladaptive; see Novella 2008 for several examples). However, through his teleological lens, Paley viewed complexities as further evidence of good design, as with his example of muscles in the eyes of cassowaries:

In the configuration of the muscle which, though placed behind the eye, draws the nictitating membrane over the eye, there is...a marvellous mechanism....The muscle is passed through a loop formed by another muscle: and is there inflected, as if it were round a pulley. This is a peculiarity; and observe the advantage of it. A single muscle with a straight tendon, which is the common muscular form, would have been sufficient, if it had had power to draw far enough. But the contraction, necessary to draw the membrane over the whole eye, required a longer muscle than could lie straight at the bottom of the eye. Therefore, in order to have a greater length in a less compass, the cord of the main muscle makes an angle. This, so far, answers the end; but, still further, it makes an angle, not round a fixed pivot, but round a loop formed by another muscle; which second muscle, whenever it contracts, of course twitches the first muscle at the point of inflection, and thereby assists the action designed by both. (p.37–38; italics in original)

In mammals, the recurrent laryngeal nerve provides a connection between the brain and the larynx, though not a direct one. Instead of taking a direct route, it passes down into the chest, circles under the aorta, and ascends back up to the neck (in giraffes, this nerve is more than 2 meters long; Harrison 1995 ). Similarly, the mammalian vas deferens connects the testes to the urethra, but not before passing into the pelvic cavity, looping around the urinary bladder and then descending back to complete its circuitous path. Meanwhile, the urethra itself passes directly through the prostate gland, an arrangement that readily engenders urinary difficulties if the prostate becomes swollen. It is only with great effort that arrangements such as these might be characterized as optimizations rather than as simple quirks of evolutionary history Footnote 10 (for additional examples, see Williams 1997 ; Shubin 2008 ; Coyne 2009 ).

But why bother with eyes at all? If the designer is omnipotent, why does the detection of visual information require such a complex arrangement of lenses, receptors, nerves, muscles, and neurons? In Paley’s words,

Why make the difficulty in order to surmount it? If to perceive objects by some other mode than that of touch, or objects which lay out of the reach of that sense, were the thing proposed; could not a simple volition of the Creator have communicated the capacity? Why resort to contrivance, where power is omnipotent? Contrivance, by its very definition and nature, is the refuge of imperfection. To have recourse to expedients, implies difficulty, impediment, restraint, defect of power. (p.39)

Thus answers Paley his own rhetorical queries:

...beside reasons of which probably we are ignorant, one answer is this: It is only by the display of contrivance, that the existence, the agency, the wisdom of the Deity, could be testified to his rational creatures. This is the scale by which we ascend to all the knowledge of our Creator which we possess, so far as it depends upon the phenomena, or the works of nature. Take away this, and you take away from us every subject of observation, and ground of reasoning; I mean as our rational faculties are formed at present. Whatever is done, God could have done without the intervention of instruments or means: but it is in the construction of instruments, in the choice and adaptation of means, that a creative intelligence is seen. It is this which constitutes the order and beauty of the universe. God, therefore, has been pleased to prescribe limits to his own power, and to work his end within those limits. (p.40)

According to Paley, the exquisite function of eyes bespeaks the great power of a designer, but the very decision to create eyes reflects an intentional limitation of this power so that humans might understand how eyes came to be. This logic may strike the modern reader as rather tortuous, but it serves to illustrate a very important point: that any explanation for complex organs must account not only for their adaptive characteristics but also their imperfections. Today, this duality can be accounted for by the countervailing influences of adaptive modification and the constraints of genetics, anatomy, and history, but for Paley, the intent of a designer provided the only conceivable answer. As noted, Paley did not consider imperfections to challenge the conclusion that design indicates the work of a designer. It is only if one wishes to defend the infallibility of the designer that one must assume all features of an object to be functional, and optimally so (see pp.56–57). Paley considered nonfunctional aspects of organisms to be “extremely rare,” and as is clear from later chapters, he viewed most aspects of the world to be optimally designed, but he was careful not to base his argument for the existence of a designer on these secondary considerations. Again, this represents something of a more sophisticated application of the argument from design than is often encountered in contemporary discourse.

Not a Chance

One of the most obstinate misconceptions about evolutionary theory is that it hypothesizes that eyes and other complex organs arise “by chance.” Even under the most charitable assessment, such a view of adaptive evolution must be considered deeply misguided. Whereas genetic mutation is both integral to the process and indeed is random with respect to its effects, natural selection is, by definition, the nonrandom survival and reproduction of individuals. Variation is generated at random, but whether or not it is preserved depends on its effects on survival and reproduction within a given environment Footnote 11 (for reviews, see Gregory 2008 , 2009 ). No serious evolutionary biologist of the past 150 years has suggested that the emergence of complex organs is merely the result of chance.

Writing as he did before Darwin and Wallace proposed the theory of natural selection, it was not possible for Paley to make this error (modern neo-Paleyans, by contrast, do so with remarkable proficiency). In the early 1800s, chance was not the only suggested alternative to conscious design (McLaughlin 2008 ), but Paley viewed its refutation as an important part of his argument. Paley (and Darwin) understood that chance plays a role in nature, but that it is incapable of producing adaptive complexity:

What does chance ever do for us? In the human body, for instance, chance, i.e. the operation of causes without design, may produce a wen, a wart, a mole, a pimple, but never an eye. Amongst inanimate substances, a clod, a pebble, a liquid drop might be; but never was a watch, a telescope, an organized body of any kind, answering a valuable purpose by a complicated mechanism, the effect of chance. (p.63)

Modern evolutionary biologists do not part company with Paley on the claim that complex organs must arise through a mechanism other than pure chance. The disagreement is only with his subsequent assertion, that “in no assignable instance hath such a thing existed without intention somewhere” (p.63).

Paley takes his argument against the role of chance a step farther, in the process raising—and summarily rejecting—a possible explanation that exhibits shades of the principle of natural selection. However, his description is of an ancient version of the idea that, as Paley rightly notes, is unworkable in practice. Footnote 12

There is another answer which has the same effect as the resolving of things into chance; which answer would persuade us to believe, that the eye, the animal to which it belongs, every other animal, every plant, indeed every organized body which we see, are only so many out of the possible varieties and combinations of being, which the lapse of infinite ages has brought into existence; that the present world is the relict of that variety: millions of other bodily forms and other species having perished, being by the defect of their constitution incapable of preservation, or of continuance by generation. Now there is no foundation whatever for this conjecture in any thing which we observe in the works of nature; no such experiments are going on at present: no such energy operates, as that which is here supposed, and which should be constantly pushing into existence new varieties of beings. Nor are there any appearances to support an opinion, that every possible combination of vegetable or animal structure has formerly been tried. Multitudes of conformations, both of vegetables and animals, may be conceived capable of existence and succession, which yet do not exist. Perhaps almost as many forms of plants might have been found in the fields, as figures of plants can be delineated upon paper. A countless variety of animals might have existed, which do not exist. Upon the supposition here stated, we should see unicorns and mermaids, sylphs and centaurs, the fancies of painters, and the fables of poets, realized by examples. Or, if it be alleged that these may transgress the limits of possible life and propagation, we might, at least, have nations of human beings without nails upon their fingers, with more or fewer fingers and toes than ten, some with one eye, others with one ear, with one nostril, or without the sense of smelling at all. All these, and a thousand other imaginable varieties, might live and propagate. We may modify any one species many different ways, all consistent with life, and with the actions necessary to preservation, although affording different degrees of conveniency and enjoyment to the animal. And if we carry these modifications through the different species which are known to subsist, their number would be incalculable. No reason can be given why, if these deperdits ever existed, they have now disappeared. Yet, if all possible existences have been tried, they must have formed part of the catalogue. (p.63–65)

The problem, of course, is not the notion that great variety may arise by chance and be narrowed by differential survival—this is the basis of natural selection as it is now understood. Rather, the implausibility of Paley’s scenario is the scale at which he considered the process. Specifically, he envisioned an unconstrained morphospace in which drastically divergent species continually pop into existence. This lies in stark contrast to Darwin’s later emphasis on small-scale variation arising within species and then being sorted generation by generation.

In this context, it is also worth noting Paley’s view on extinction—namely that it does not happen. According to Paley, the classification of species into larger taxa would be rendered impossible by widespread extinction. In contrast, extinction was established as a common process in the history of life by Darwin’s time, and today it is acknowledged that the overwhelming majority of species that have existed no longer grace the Earth. In fact, the major divisions among extant lineages are now understood to exist precisely because so many ancestors and intermediate forms have perished.

Design and Diversity

The preceding arguments occupy only the first six of the 27 chapters in Natural Theology . In Chapters 7 through 20, Paley leads the reader on an expedition through the annals of early nineteenth century biological knowledge as he understands it, pausing along the way to admire the elegance of the bones (Chapter 8), muscles (Chapter 9), blood vessels (Chapter 10), and digestive systems (Chapters 7 and 10) of vertebrates, as well as features of insects (Chapter 19) and plants (Chapter 20) which, though less well understood, he also described as bearing the hallmarks of design.

Once again, modern biology does not contradict Paley’s enthusiastic exposition of features well-suited to specific functions, only the way in which their origin is explained. Similarly, Paley takes a broad comparative approach that would be at home in modern evolutionary biology were it interpreted from a different perspective. He recognizes that specializations for particular lifestyles reflect modifications of traits shared by many animals. He grasps the unity of underlying body plans. And he notes that though it dissipates among groups living in widely divergent habitats, the similarity does not disappear. Consider the following passages from Chapter 12 on “Comparative Anatomy”:

Whenever we find a general plan pursued, yet with such variations in it as are, in each case, required by the particular exigency of the subject to which it is applied, we possess, in such plan and such adaptation, the strongest evidence that can be afforded of intelligence and design; an evidence which most completely excludes every other hypothesis. If the general plan proceeded from any fixed necessity in the nature of things, how could it accommodate itself to the various wants and uses which it had to serve under different circumstances, and on different occasions? (p.211)

Very much of this reasoning is applicable to what has been called Comparative Anatomy . In their general economy, in the outlines of the plan, in the construction as well as offices of their principal parts, there exists between all large terrestrial animals a close resemblance. In all, life is sustained, and the body nourished by nearly the same apparatus. The heart, the lungs, the stomach, the liver, the kidneys, are much alike in all. The same fluid (for no distinction of blood has been observed) circulates through their vessels, and nearly in the same order. The same cause, therefore, whatever that cause was, has been concerned in the origin, has governed the production of these different animal forms.

When we pass on to smaller animals, or to the inhabitants of a different element, the resemblance becomes more distant and more obscure; but still the plan accompanies us. (pp.212–213)

Chapter 13 deals with the opposite subject, namely adaptations (“Peculiar Organizations”) that are unique to particular groups: features of the neck of large mammals, the swim bladder of fishes, the fangs of snakes, the pouches of marsupials, the claws of birds, the stomach of camels, the tongue of woodpeckers, and the curved tusks of wild boars. These, like functional traits shared more broadly, also reflect the remarkable fit of species to their environments which Paley takes as strong evidence for their origin by design.

In Chapter 14, Paley lends particular credence to examples of adaptive features that emerge ontogenetically before they are needed, in preparation for use later in life (“Prospective Contrivances”):

I can hardly imagine to myself a more distinguishing mark, and, consequently, a more certain proof of design, than preparation , i.e. the providing of things beforehand, which are not to be used until a considerable time afterwards; for this implies a contemplation of the future, which belongs only to intelligence. (p.252)

The teeth of mammals, the milk that nourishes their young, their eyes that develop while still in the darkness of the womb, and their lungs that form before encountering any opportunity to draw a breath—in the absence of knowledge about developmental genetics, these struck Paley as especially weighty examples of foresightful design.

Fitting Together

Paley does not only rely on individual examples of function to support his position. In addition, he expounds upon the close interaction of parts in service of a specific function. He returns to the analogy of the watch in this capacity at the opening of Chapter 15:

When several different parts contribute to one effect; or, which is the same thing, when an effect is produced by the joint action of different instruments; the fitness of such parts or instruments to one another, for the purpose of producing, by their united action the effect, is what I call relation: and wherever this is observed in the works of nature or of man, it appears to me to carry along with it decisive evidence of understanding, intention, art. In examining, for instance, the several parts of a watch , the spring, the barrel, the chain, the fusee, the balance, the wheels of various sizes, forms, and positions, what is it which would take an observer's attention, as most plainly evincing a construction, directed by thought, deliberation, and contrivance? It is the suitableness of these parts to one another; first, in the succession and order in which they act; and, secondly, with a view to the effect finally produced. (pp. 261–262)