Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 2: Ethics in Public Speaking

This chapter, except where otherwise noted, is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 .

What are the objectives of ethical speaking?

Now that you’ve learned the foundations of public speaking, you know that creating a speech involves more than just slapping some facts together and hoping your audience listens. In this module, we move on to explore a core element of public speaking: the importance of ethical communication. We’ve all heard advertisers, received a sales pitch, and listened to politicians who try and persuade us to take some action. But how do we know these are ethical communications? Speechmakers may manipulate facts, present one-sided arguments, and even lie to persuade their audience. And the audience may be fooled if they are not listening critically. None of these actions involve ethical communication. When speakers do not speak ethically, they taken advantage of their audience. When an audience does not listen critically, they disrespect the speaker.

In this module, we will explore what it means to be both an ethical speaker and an ethical listener. You can ethically and effectively persuade. And you can take responsibility to be ethically informed. We will show you how.

Ethical Speaking

Every day, people around the world make ethical decisions regarding public speech, for example, is it ever appropriate to lie if it’s in a group’s best interest? Should you use evidence to support your speech’s core argument when you are not sure if the evidence is correct? Should you refuse to listen to a speaker with whom you fundamentally disagree? These three examples represent ethical choices that speakers and listeners face in the public speaking context. To help you understand the issues involved with thinking about ethics, we begin this module by presenting an ethical communications model, known as the ethics pyramid. We will then show how you can apply the National Communication Association’s (NCA) Credo for Ethical Communication to public speaking. We will conclude with a general free speech discussion.

The Ethics Pyramid

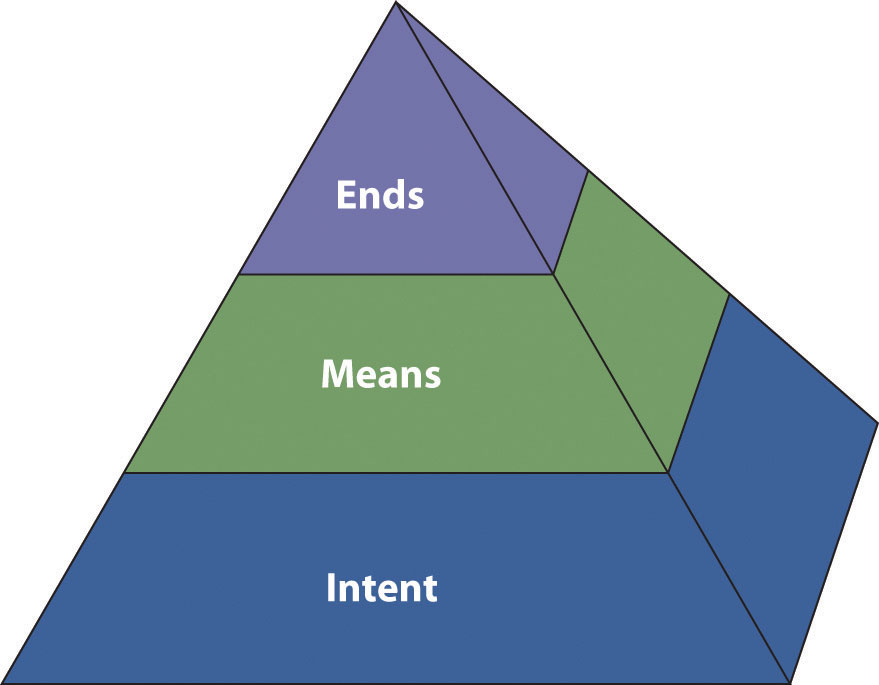

One way to talk about ethics is to use the ethics pyramid. What is the ethics pyramid?

Elspeth Tilley, a public communication ethics expert from Massey University, proposes a structured approach to thinking about ethics (Tilley, 2005). Her ethics pyramid involves three basic concepts: intent, means, and ends.

According to Tilley, intent is the first major concept to consider when examining an issue’s ethicality. To be an ethical speaker or listener, it is important to begin with ethical intentions. For example, if we agree that honesty is ethical, it follows that ethical speakers will prepare their remarks with the intent to tell the truth to their audiences. Similarly, if we agree that it is ethical to listen with an open mind, it follows that ethical listeners will intend to hear a speaker’s case before forming judgments.

Many professional organizations, including the Independent Computer Consultants Association, American Counseling Association, and American Society of Home Inspectors, have codes of conduct or ethical guidelines for their members. Individual corporations such as Monsanto, Coca-Cola, Intel, and ConocoPhillips also have ethical guidelines for how their employees should interact with suppliers or clients.

It is important to be aware that people can unintentionally engage in unethical behavior. For example, suppose we agree that it is unethical to take someone else’s words and pass them off as your own—a behavior known as plagiarism. What happens if a speaker makes a statement that he believes he thought of on his own, but the statement is actually quoted from a radio commentator whom he heard without clearly remembering doing so? The plagiarism is unintentional, but does that make it ethical?

Tilley describes the means you use to communicate with others as the ethics pyramid’s second concept. According to McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond, “means are the tools or behaviors we employ to achieve a desired outcome” (McCroskey, Wrench, & Richmond, 2003). Some means are good and some bad.

For example, suppose you want your friend Marty to spend an hour reviewing your speech. What means might you use to persuade Marty to do you this favor? You might explain to Marty’s that you value his opinion and will gladly return the favor when Marty prepares his speech (good means), or you might inform Marty that you’ll tell his professor that he cheated on a test (bad means). While both of these means may lead to the same end—Marty agrees to review your speech—one is clearly more ethical than the other.

Ends is the ethics pyramid s third concept. According to McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond (McCroskey, Wrench, & Richmond, 2003), “ends are those outcomes that you desire to achieve.” Ends might include the following:

- Persuading your audience to make a financial contribution for you to participate in Relay for Life.

- Persuading a group of homeowners that your real estate agency would best meet their needs.

- Informing your fellow students about newly required university fees.

Whereas the means are the behavioral choices we make, the ends are the results of those choices.

Like intent and means, ends can be good or bad. For example, suppose a city council wants to balance the city’s annual budget. Balancing the budget may be a good end, assuming that the city has adequate tax revenues and some discretionary spending for city services. However, voters might argue that balancing the budget is a bad end if the city lacks the tax revenue and must raise taxes or cut essential city services, or both, to do so.

What are the guidelines for ethical speaking?

Steven Lucas, a well-known speech instructor, put together five helpful guidelines to ensure ethical speechmaking (Lucas, 2012, pp. 31-35).

- Make sure your goals are ethically sound. Are you asking your audience to do something you yourself do not believe in, do not think is good for the audience, or would not do yourself?

- Be fully prepared for each speech. Don’t cheat the audience by just winging it. If you calculate the money each person in your audience makes during the time you speak, do you want to waste that much of their time and money? As speakers we have a solemn responsibility to make that time worthwhile.

- Be honest in what you say. Speechmaking rests on the assumption that words can be trusted and that people will be truthful. Without this assumption, there is no basis for communication and no reason for one person to believe anything that another person says.

- Avoid name-calling and other forms of abusive language. Names leave psychological scars that last for years. Name-calling defames, demeans, or degrades. These words dehumanize people, all of whom should be treated with dignity and respect.

- Put ethical principles into practice. Being ethical means behaving ethically all the time—not only when it’s convenient (Lucas, 2012, pp.34-35).

Your audience is watching you even when you are not speechmaking. If you try to be honest in your speeches, yet an audience member observes you lying to a classmate, what does that do to your credibility as an ethical speaker? Something to consider.

A Speaker’s Ethical Obligation

According to Lucas, “Name-calling and abusive language pose ethical problems in public speaking when they are used to silence opposing voices. A democratic society depends upon open expression of ideas. In the United States, all citizens have the right to join in democracy’s never-ending dialogue. As a public speaker, you have an ethical obligation to help preserve that right by avoiding tactics such as name-calling, which inherently impugn the accuracy or respectability of public statements made by groups or individual who voice opinions different from yours.

“The obligation is the same whether you are black or white, Christian or Muslim, male or female, gay or straight, liberal or conservative. A pro-union public employee who castigated everyone opposed to her ideas as an “enemy of the middle class” is unethical. A politician who labels all his adversaries “tax-and-spend liberals” is unethical. Although name-calling can be hazardous to free speech, it is still protected under the Bill of Right’s free-speech clause.

Nevertheless, it will not alter the ethical responsibility of public speakers on or off campus to avoid name-calling and other kinds of abusive language” (Lucas, 2012, pp.34-35).

Important Ethical Principles

The largest communication organization in the United States and second largest in the world created an ethical credo outlining important principles to follow if we want to be ethical communicators. Notice how they indicate that ethical speaking takes courage.

National Communication Association Credo for Ethical Communication

Questions of right and wrong arise whenever people communicate. Ethical communication is fundamental to responsible thinking, decision making, and the development of relationships and communities within and across contexts, cultures, channels, and media. Moreover, ethical communication enhances human worth and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others. We believe that unethical communication threatens the quality of all communication and consequently the well-being of individuals and the society in which we live. Therefore we, the members of the National Communication Association, endorse and are committed to practicing the following principles of ethical communication:

- We advocate truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication.

- We endorse freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and tolerance of dissent to achieve the informed and responsible decision making fundamental to a civil society.

- We strive to understand and respect other communicators before evaluating and responding to their messages.

- We promote access to communication resources and opportunities as necessary to fulfill human potential and contribute to the well-being of families, communities, and society.

- We promote communication climates of caring and mutual understanding that respect the unique needs and characteristics of individual communicators.

- We condemn communication that degrades individuals and humanity through distortion, intimidation, coercion, and violence, and through the expression of intolerance and hatred.

- We are committed to the courageous expression of personal convictions in pursuit of fairness and justice.

- We advocate sharing information, opinions, and feelings when facing significant choices while also respecting privacy and confidentiality.

- We accept responsibility for the short- and long-term consequences of our own communication and expect the same of others.

Source: National Communication Association

Applying Ethical Principles

Use reason and logical arguments. While there are cases where speakers have blatantly lied to an audience, it is more common for speakers to prove a point by exaggerating, omitting facts that weigh against their message, or distorting information. We believe that speakers build a relationship with their audiences, and that lying, exaggerating, or distorting information violates this relationship. Ultimately, a speaker will be more persuasive by using reason and logical arguments.

Choose objective sources. It is also important to be honest about where you get your information. As speakers, examine your sources and research and determine whether they are biased or have hidden agendas. For example, you are not likely to get accurate information about nonwhite individuals from a neo-Nazi website. While you may not know all your sources firsthand, you should attempt to find objective sources that do not have an overt or covert agenda that skews the argument you are making.

Don’t plagiarize. Using someone else’s words or ideas without giving credit is called plagiarism. The word “plagiarism” stems from the Latin word plagiaries, or kidnapper. The consequences for failing to cite sources during public speeches can be substantial. When Senator Joseph Biden was running for president of the United States in 1988, reporters found that he had plagiarized portions of his stump speech from British politician Neil Kinnock. Biden was forced to drop out of the race as a result. More recently, the student newspaper at Malone University in Ohio alleged that university president, Gary W. Streit, had plagiarized material in a public speech. Streit retired abruptly as a result.

Cite your sources. Even if you are not running for president of the United States or serving as a college president, citing sources is important to you as a student. Many universities have policies that include dismissing students from the institution for plagiarizing academic work, including public speeches. Failing to cite your sources might result, at best, in lowering your credibility with your audience and, at worst, in a failing course grade or school expulsion.

Speakers tend to fall into one of three major traps regarding plagiarism.

- The first trap is failing to tell the audience the source of a direct quotation.

- The second trap is paraphrasing what someone else said or wrote without giving credit to the speaker or author. For example, you may have read a book and learned that there are three types of schoolyard bullying. In the middle of your speech, you talk about those three types of bullying. If you do not tell your audience where you found that information, you are plagiarizing.

- The third trap that speakers fall into is re-citing someone else’s sources within a speech. To explain this problem, let’s look at a brief segment from a research paper written by Wrench, DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam:

“The main character on the hit Fox television show House , Dr. Gregory House, has one basic mantra, “It’s a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies. The only variable is about what” (Shore & Barclay, 2005). This notion that “everybody lies” is so persistent in the series that t-shirts have been printed with the slogan. Surprisingly, research has shown that most people do lie during interpersonal interactions to some degree. In a study conducted by Turner, Edgley, and Olmstead (1975), the researchers had 130 participants record their own conversations with others. After recording these conversations, the participants then examined the truthfulness of the statements within the interactions. Only 38.5% of the statements made during these interactions were labeled as “completely honest.”

In this example, we see that the authors of this paragraph cited information from two external sources: Shore and Barclay and Tummer, Edgley, and Olmstead. These two groups of authors are given credit for their ideas. The authors make it clear that they did not produce the television show House or conduct the study that found that only 38.5 percent of statements were completely honest. Instead, these authors cited information found in two other locations. This type of citation is appropriate.

However, if a speaker read the paragraph and said the following during a speech, it would be plagiarism:

“According to Wrench DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam, in a study of 130 participants, only 38.5 percent of the responses were completely honest.”

In this case, the speaker is attributing the information cited to the authors of the paragraph, which is not accurate. If you want to cite the information within your speech, you need to read the original article by Turner, Edgley, and Olmstead and cite that information yourself.

There are two main reasons we do this.

- First, Wrench, DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam may have mistyped the information. Suppose the study by Turner, Edgley, and Olstead really actually found that 58.5 percent of the responses were completely honest. If you cited the revised number (38.5 percent) from the paragraph, you would be further spreading incorrect information.

- The second reason we do not re-cite someone else’s sources within our speeches is because it’s intellectually dishonest. You owe your listeners an honest description of where the facts you are relating came from, not just the name of an author who cited those facts. It is more work to trace the original source of a fact or statistic, but by doing that extra work you can avoid this plagiarism trap.

The Difference Between Global, Patchwork, and Incremental Plagiarism

This section is adapted from The Art of Public Speaking by Stephen E Lucas.

Global plagiarism: Stealing speech entirely from a single source and passing it off as your own. Maybe you go online and find a speech, or you use the speech your spouse created for her speech class. These are both examples of global plagiarism.

Patchwork plagiarism: Stealing ideas from two or more sources and passing them off as your own. You cut and paste information from one source, then another, then another and patch them together to make your speech, but you don’t cite each source within your speech.

Incremental plagiarism: Failing to give credit for particular parts of a speech that are borrowed from other people. In global and patchwork plagiarism, the entire speech is cribbed more or less verbatim from a single source or a few sources. But incremental plagiarism occurs when you borrow particular parts or increments from other people, quotes, or phrases to make your speech, and you don’t give credit. For example:

Whenever you quote someone directly, you must attribute the words to that person.

Scientist Roberts said, “Rocks also contain remnants of their electromagnetic information.”

Whenever you summarize or paraphrase someone else’s words or ideas you must attribute it to that person.

According to historian Belford, we are on the brink of a new era.

Now you have clearly identified Roberts and Belford and given them credit for their words, rather than presenting them as your own.

Ethically, we need to talk about your captive audience.

Captive Audiences

“Captive audience doctrine posits a situation in which the listener has no choice but to hear the undesired speech. This lack of choice has a strong spatial component to it: indeed, the classic example of a captive audience is being the target of residential picketing” (William, 2003, p. 400). For example, if picketers come to your neighborhood to picket the coming of a large store chain in a residential area, their speeches, yelling and propaganda can be heard in your home. They have entered your space and it doesn’t matter that you need quiet to put your little one down for a nap or you don’t agree with the picketer’s message, your are forced to listen because they are in your space.

“Defenders of sexual harassment law argue that employees’ need to earn a living makes the workplace a context where an employee should not be forced to listen to undesired speech” (William, 2003, p.404).

“In the case of the internet, it could be argued that the inability to filter out undesirable speech creates an unacceptable dilemma for a would-be user: use the internet and subject yourself to the risk of encountering such speech, or abstain altogether from using the medium (William, 2003, p. 404).

If we take this captive audience idea to our classroom, how does it apply? We are asking you to listen to at least two of your fellow students’ speeches as part of your grade. You don’t know if you will hear something offensive or something you don’t want to hear.

Knowing that others are required to hear your speech, implies that you are responsible for creating a speech that takes your “captive audience” into account and that you do not abuse the privilege. What does this mean to you when preparing a speech?

Topic Choice

Does this mean you cannot choose a controversial topic? You may choose a controversial topic. We will walk you through how to do that and still respect your audience.

Word Choice

Does this mean you can choose any words you want? Gone are the days when “sticks and stone could break our bones but words could never hurt us.” Words carry meaning and the ability to harm and alienate our audience. We will walk you through how to compose your speech to draw your audience in so they will want to hear more.

Visual Aids

Does this mean you can choose any visual aids you want? Visual images can be powerful ways to communicate your meaning if chosen well. They can also be damaging if not chosen well. We will walk you through how to choose your visual aids.

Gestures and Non-Verbal Delivery

Does this mean you can use any non-verbal delivery you want? More than 75 percent of our communication is non-verbal. It has a powerful effect on our audience. We will help you choose your non-verbal delivery so it will enhance your speech.

Captive Audience Outside of Class

Does this mean that you can speak to a captive audience any way you want outside of class? Outside of class, speakers still have a responsibility to respect their captive-audience privilege and to speak and use it ethically. We’ll talk about how.

The First Amendment and Free Speech

Some speakers feel that they can talk about anything they want, to anyone they want, in anyway they want because their speech is protected under the First Amendment, allowing them to behave in the following ways:

- Be foul mouthed.

- Use destructive topics.

- Use naked visual aids.

- Tell their audience how much they should despise their neighbors.

These speakers feel the First Amendment gives them the freedom of any kind of speech. Do you know if this is true?

Speech Covered Under the First Amendment

Disputes over the meaning and scope of the First Amendment arise almost daily in connection with issues such as terrorism, pornography, and hate speech.

There are some kinds of speech that are not protected under the First Amendment, including the following:

- Defamatory falsehoods that destroy a person’s reputation.

- Threats against the life of the President.

- Inciting an audience to illegal action in circumstances where the audience is likely to carry out the action.

Otherwise, the Supreme Court has held—and most ethics communication experts have agreed—that public speakers have an almost unlimited right of free expression.

While free speech allows for much individual expression, you have learned that there are ethical guidelines for public speaking. But did you know there are ethical guidelines for listening as well?

It is surprising to see that adults, in a sedate context, set a poor example and forget their ethical listening manners. See if you can hear them in the video, GOP Rep. to Obama: “You lie!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sipHTEARyYo

GOP Rep to Obama You Lie! , by Communication 1020 Videso , Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sipHTEARyYo

There is a time for debate, disagreement, and protest. However, ethical listening takes into account the following:

- What is appropriate for the context.

- The implications of an outburst.

Lucas gives us clear information about ethical listening in his list.

Guidelines for Ethical Listening

- Be courteous and attentive. The speaker has put a lot of work into the speech. It is surprising how often student audience members think it is ok to look at their phones, newspapers, work on homework, or even leave the room during a speech. These are all unethical listening behaviors and should be avoided.

- Avoid prejudging the speaker. It is easy to see what a speaker is wearing, their accent, or even word choice and to prejudge their message. This doesn’t mean you need to agree with everything a speaker has to say, but you might be surprised what you will learn if you attentively listen to the full speech with an open mind.

- Maintain the free and open expression of ideas. Just as the speaker needs to avoid name-calling and tactics that shut down free speech, listeners have an obligation to maintain the speaker’s right to be heard. You don’t need to agree with the speaker.

Lucas, S.E. (2014). The Art of Public Speaking (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

University of Minnesota. (2011). Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking . University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/ . CC BY-SA 4.0.

William, D. A. (2003). Captive audiences, children and the internet. Brandeis Law Journal 41, 397-415

Media References

(no date). yell, shout, scream, anger, angry, mouth, person, human body part, body part, close-up [Image]. pxfuel. https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-odgkm

A K M Adam. (2018, 28 February). Picketers, Exam Schools [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/akma/39950320734/

Bruce Mars. (no date). Woman Thinking Photo [Image]. StockSnap. https://stocksnap.io/photo/woman-thinking-MLZIHL9GLY

Caragiuss. (2013, 29 January). Ballroom dance [Image]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ballroom_dance.jpg

Carmella Fernando. (2007, 24 September). Promise? [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/13923263@N07/1471150324/

Communication 1020 Videso. (2021, November 9). GOP Rep to Obama You Lie! Source [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sipHTEARyYo

OpenClipart-Vectors. (2016, March 31). Angel Chess Demon [Image]. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/vectors/angel-chess-demon-devil-evil-game-1294401/

Presidio of Monterey. (2014, 26 April). DLIFLC students compete in 39th Annual Mandarin Speech Contest in San Francisco [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/presidioofmonterey/13890165109

Sulogocreativocom. (2017, 15 September). Coca cola ejemplo logo [Image]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coca_cola_ejemplo_logo.png

Tilley, E. (2005). The ethics pyramid: Making ethics unavoidable in the public relations process. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 20 , 305–320. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/2-1-the-ethics-pyramid/#wrench_1.0-ch02_s01_f01

Public Speaking Copyright © 2022 by Sarah Billington and Shirene McKay is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.2 Ethics in Public Speaking

Learning objectives.

- Understand how to apply the National Communication Association (NCA) Credo for Ethical Communication within the context of public speaking.

- Understand how you can apply ethics to your public speaking preparation process.

The study of ethics in human communication is hardly a recent endeavor. One of the earliest discussions of ethics in communication (and particularly in public speaking) was conducted by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato in his dialogue Phaedrus . In the centuries since Plato’s time, an entire subfield within the discipline of human communication has developed to explain and understand communication ethics.

Communication Code of Ethics

In 1999, the National Communication Association officially adopted the Credo for Ethical Communication (see the following sidebar). Ultimately, the NCA Credo for Ethical Communication is a set of beliefs communication scholars have about the ethics of human communication.

National Communication Association Credo for Ethical Communication

Questions of right and wrong arise whenever people communicate. Ethical communication is fundamental to responsible thinking, decision making, and the development of relationships and communities within and across contexts, cultures, channels, and media. Moreover, ethical communication enhances human worth and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others. We believe that unethical communication threatens the quality of all communication and consequently the well-being of individuals and the society in which we live. Therefore we, the members of the National Communication Association, endorse and are committed to practicing the following principles of ethical communication:

- We advocate truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication.

- We endorse freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and tolerance of dissent to achieve the informed and responsible decision making fundamental to a civil society.

- We strive to understand and respect other communicators before evaluating and responding to their messages.

- We promote access to communication resources and opportunities as necessary to fulfill human potential and contribute to the well-being of families, communities, and society.

- We promote communication climates of caring and mutual understanding that respect the unique needs and characteristics of individual communicators.

- We condemn communication that degrades individuals and humanity through distortion, intimidation, coercion, and violence, and through the expression of intolerance and hatred.

- We are committed to the courageous expression of personal convictions in pursuit of fairness and justice.

- We advocate sharing information, opinions, and feelings when facing significant choices while also respecting privacy and confidentiality.

- We accept responsibility for the short- and long-term consequences of our own communication and expect the same of others.

Source: http://www.natcom.org/Default.aspx?id=134&terms=Credo

Applying the NCA Credo to Public Speaking

The NCA Credo for Ethical Communication is designed to inspire discussions of ethics related to all aspects of human communication. For our purposes, we want to think about each of these principles in terms of how they affect public speaking.

We Advocate Truthfulness, Accuracy, Honesty, and Reason as Essential to the Integrity of Communication

Carmella Fernando – Promise? – CC BY 2.0.

As public speakers, one of the first ethical areas we should be concerned with is information honesty. While there are cases where speakers have blatantly lied to an audience, it is more common for speakers to prove a point by exaggerating, omitting facts that weigh against their message, or distorting information. We believe that speakers build a relationship with their audiences, and that lying, exaggerating, or distorting information violates this relationship. Ultimately, a speaker will be more persuasive by using reason and logical arguments supported by facts rather than relying on emotional appeals designed to manipulate the audience.

It is also important to be honest about where all your information comes from in a speech. As speakers, examine your information sources and determine whether they are biased or have hidden agendas. For example, you are not likely to get accurate information about nonwhite individuals from a neo-Nazi website. While you may not know all your sources of information firsthand, you should attempt to find objective sources that do not have an overt or covert agenda that skews the argument you are making. We will discuss more about ethical sources of information in Chapter 7 “Researching Your Speech” later in this book.

The second part of information honesty is to fully disclose where we obtain the information in our speeches. As ethical speakers, it is important to always cite your sources of information within the body of a speech. Whether you conducted an interview or read a newspaper article, you must tell your listeners where the information came from. We mentioned earlier in this chapter that using someone else’s words or ideas without giving credit is called plagiarism . The word “plagiarism” stems from the Latin word plagiaries , or kidnapper. The American Psychological Association states in its publication manual that ethical speakers do not claim “words and ideas of another as their own; they give credit where credit is due” (American Psychological Association, 2001).

In the previous sentence, we placed quotation marks around the sentence to indicate that the words came from the American Psychological Association and not from us. When speaking informally, people sometimes use “air quotes” to signal direct quotations—but this is not a recommended technique in public speaking. Instead, speakers need to verbally tell an audience when they are using someone else’s information. The consequences for failing to cite sources during public speeches can be substantial. When Senator Joseph Biden was running for president of the United States in 1988, reporters found that he had plagiarized portions of his stump speech from British politician Neil Kinnock. Biden was forced to drop out of the race as a result. More recently, the student newspaper at Malone University in Ohio alleged that the university president, Gary W. Streit, had plagiarized material in a public speech. Streit retired abruptly as a result.

Even if you are not running for president of the United States or serving as a college president, citing sources is important to you as a student. Many universities have policies that include dismissal from the institution for student plagiarism of academic work, including public speeches. Failing to cite your sources might result, at best, in lower credibility with your audience and, at worst, in a failing grade on your assignment or expulsion from your school. While we will talk in more detail about plagiarism later in this book, we cannot emphasize enough the importance of giving credit to the speakers and authors whose ideas we pass on within our own speeches and writing.

Speakers tend to fall into one of three major traps with plagiarism. The first trap is failing to tell the audience the source of a direct quotation. In the previous paragraph, we used a direct quotation from the American Psychological Association; if we had not used the quotation marks and clearly listed where the cited material came from, you, as a reader, wouldn’t have known the source of that information. To avoid plagiarism, you always need to tell your audience when you are directly quoting information within a speech.

The second plagiarism trap public speakers fall into is paraphrasing what someone else said or wrote without giving credit to the speaker or author. For example, you may have read a book and learned that there are three types of schoolyard bullying. In the middle of your speech you talk about those three types of schoolyard bullying. If you do not tell your audience where you found that information, you are plagiarizing. Typically, the only information you do not need to cite is information that is general knowledge. General knowledge is information that is publicly available and widely known by a large segment of society. For example, you would not need to provide a citation within a speech for the name of Delaware’s capital. Although many people do not know the capital of Delaware without looking it up, this information is publicly available and easily accessible, so assigning credit to one specific source is not useful or necessary.

The third plagiarism trap that speakers fall into is re-citing someone else’s sources within a speech. To explain this problem, let’s look at a brief segment from a research paper written by Wrench, DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam:

The main character on the hit Fox television show House , Dr. Gregory House, has one basic mantra, “It’s a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies. The only variable is about what” (Shore & Barclay, 2005). This notion that “everybody lies” is so persistent in the series that t-shirts have been printed with the slogan. Surprisingly, research has shown that most people do lie during interpersonal interactions to some degree. In a study conducted by Turner, Edgley, and Olmstead (1975), the researchers had 130 participants record their own conversations with others. After recording these conversations, the participants then examined the truthfulness of the statements within the interactions. Only 38.5% of the statements made during these interactions were labeled as “completely honest.”

In this example, we see that the authors of this paragraph cited information from two external sources: Shore and Barclay and Tummer, Edgley, and Olmstead. These two groups of authors are given credit for their ideas. The authors make it clear that they did not produce the television show House or conduct the study that found that only 38.5 percent of statements were completely honest. Instead, these authors cited information found in two other locations. This type of citation is appropriate.

However, if a speaker read the paragraph and said the following during a speech, it would be plagiarism: “According to Wrench DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam, in a study of 130 participants, only 38.5 percent of the responses were completely honest.” In this case, the speaker is attributing the information cited to the authors of the paragraph, which is not accurate. If you want to cite the information within your speech, you need to read the original article by Turner, Edgley, and Olmstead and cite that information yourself.

There are two main reasons we do this. First, Wrench, DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam may have mistyped the information. Suppose the study by Turner, Edgley, and Olstead really actually found that 58.5 percent of the responses were completely honest. If you cited the revised number (38.5 percent) from the paragraph, you would be further spreading incorrect information.

The second reason we do not re-cite someone else’s sources within our speeches is because it’s intellectually dishonest. You owe your listeners an honest description of where the facts you are relating came from, not just the name of an author who cited those facts. It is more work to trace the original source of a fact or statistic, but by doing that extra work you can avoid this plagiarism trap.

We Endorse Freedom of Expression, Diversity of Perspective, and Tolerance of Dissent to Achieve the Informed and Responsible Decision Making Fundamental to a Civil Society

This ethical principle affirms that a civil society depends on freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and tolerance of dissent and that informed and responsible decisions can only be made if all members of society are free to express their thoughts and opinions. Further, it holds that diverse viewpoints, including those that disagree with accepted authority, are important for the functioning of a democratic society.

If everyone only listened to one source of information, then we would be easily manipulated and controlled. For this reason, we believe that individuals should be willing to listen to a range of speakers on a given subject. As listeners or consumers of communication, we should realize that this diversity of perspectives enables us to be more fully informed on a subject. Imagine voting in an election after listening only to the campaign speeches of one candidate. The perspective of that candidate would be so narrow that you would have no way to accurately understand and assess the issues at hand or the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing candidates. Unfortunately, some voters do limit themselves to listening only to their candidate of choice and, as a result, base their voting decisions on incomplete—and, not infrequently, inaccurate—information.

Listening to diverse perspectives includes being willing to hear dissenting voices. Dissent is by nature uncomfortable, as it entails expressing opposition to authority, often in very unflattering terms. Legal scholar Steven H. Shiffrin has argued in favor of some symbolic speech (e.g., flag burning) because we as a society value the ability of anyone to express their dissent against the will and ideas of the majority (Shiffrin, 1999). Ethical communicators will be receptive to dissent, no matter how strongly they may disagree with the speaker’s message because they realize that a society that forbids dissent cannot function democratically.

Ultimately, honoring free speech and seeking out a variety of perspectives is very important for all listeners. We will discuss this idea further in the chapter on listening.

We Strive to Understand and Respect Other Communicators before Evaluating and Responding to Their Messages

This is another ethical characteristic that is specifically directed at receivers of a message. As listeners, we often let our perceptions of a speaker’s nonverbal behavior—his or her appearance, posture, mannerisms, eye contact, and so on—determine our opinions about a message before the speaker has said a word. We may also find ourselves judging a speaker based on information we have heard about him or her from other people. Perhaps you have heard from other students that a particular teacher is a really boring lecturer or is really entertaining in class. Even though you do not have personal knowledge, you may prejudge the teacher and his or her message based on information you have been given from others. The NCA credo reminds us that to be ethical listeners, we need to avoid such judgments and instead make an effort to listen respectfully; only when we have understood a speaker’s viewpoint are we ready to begin forming our opinions of the message.

Listeners should try to objectively analyze the content and arguments within a speech before deciding how to respond. Especially when we disagree with a speaker, we might find it difficult to listen to the content of the speech and, instead, work on creating a rebuttal the entire time the speaker is talking. When this happens, we do not strive to understand the speaker and do not respect the speaker.

Of course, this does not just affect the listener in the public speaking situation. As speakers, we are often called upon to evaluate and refute potential arguments against our positions. While we always want our speeches to be as persuasive as possible, we do ourselves and our audiences a disservice when we downplay, distort, or refuse to mention important arguments from the opposing side. Fairly researching and evaluating counterarguments is an important ethical obligation for the public speaker.

We Promote Access to Communication Resources and Opportunities as Necessary to Fulfill Human Potential and Contribute to the Well-Being of Families, Communities, and Society

Human communication is a skill that can and should be taught. We strongly believe that you can become a better, more ethical speaker. One of the reasons the authors of this book teach courses in public speaking and wrote this college textbook on public speaking is that we, as communication professionals, have an ethical obligation to provide others, including students like you, with resources and opportunities to become better speakers.

We Promote Communication Climates of Caring and Mutual Understanding That Respect the Unique Needs and Characteristics of Individual Communicators

Speakers need to take a two-pronged approach when addressing any audience: caring about the audience and understanding the audience. When you as a speaker truly care about your audience’s needs and desires, you avoid setting up a manipulative climate. This is not to say that your audience will always perceive their own needs and desires in the same way you do, but if you make an honest effort to speak to your audience in a way that has their best interests at heart, you are more likely to create persuasive arguments that are not just manipulative appeals.

Second, it is important for a speaker to create an atmosphere of mutual understanding. To do this, you should first learn as much as possible about your audience, a process called audience analysis. We will discuss this topic in more detail in the audience analysis chapter.

To create a climate of caring and mutual respect, it is important for us as speakers to be open with our audiences so that our intentions and perceptions are clear. Nothing alienates an audience faster than a speaker with a hidden agenda unrelated to the stated purpose of the speech. One of our coauthors once listened to a speaker give a two-hour talk, allegedly about workplace wellness, which actually turned out to be an infomercial for the speaker’s weight-loss program. In this case, the speaker clearly had a hidden (or not-so-hidden) agenda, which made the audience feel disrespected.

We Condemn Communication That Degrades Individuals and Humanity through Distortion, Intimidation, Coercion, and Violence and through the Expression of Intolerance and Hatred

This ethical principle is very important for all speakers. Hopefully, intimidation, coercion, and violence will not be part of your public speaking experiences, but some public speakers have been known to call for violence and incite mobs of people to commit attrocities. Thus distortion and expressions of intolerance and hatred are of special concern when it comes to public speaking.

Distortion occurs when someone purposefully twists information in a way that detracts from its original meaning. Unfortunately, some speakers take information and use it in a manner that is not in the spirit of the original information. One place we see distortion frequently is in the political context, where politicians cite a statistic or the results of a study and either completely alter the information or use it in a deceptive manner. FactCheck.org, a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center ( http://www.factcheck.org ), and the St. Petersburg Times’s Politifact ( http://www.politifact.com ) are nonpartisan organizations devoted to analyzing political messages and demonstrating how information has been distorted.

Expressions of intolerance and hatred that are to be avoided include using ageist , heterosexist , racist , sexist , and any other form of speech that demeans or belittles a group of people. Hate speech from all sides of the political spectrum in our society is detrimental to ethical communication. As such, we as speakers should be acutely aware of how an audience may perceive words that could be considered bigoted. For example, suppose a school board official involved in budget negotiations used the word “shekels” to refer to money, which he believes the teachers’ union should be willing to give up (Associated Press, 2011). The remark would be likely to prompt accusations of anti-Semitism and to distract listeners from any constructive suggestions the official might have for resolving budget issues. Although the official might insist that he meant no offense, he damaged the ethical climate of the budget debate by using a word associated with bigotry.

At the same time, it is important for listeners to pay attention to expressions of intolerance or hatred. Extremist speakers sometimes attempt to disguise their true agendas by avoiding bigoted “buzzwords” and using mild-sounding terms instead. For example, a speaker advocating the overthrow of a government might use the term “regime change” instead of “revolution”; similarly, proponents of genocide in various parts of the world have used the term “ethnic cleansing” instead of “extermination.” By listening critically to the gist of a speaker’s message as well as the specific language he or she uses, we can see how that speaker views the world.

We Are Committed to the Courageous Expression of Personal Convictions in Pursuit of Fairness and Justice

We believe that finding and bringing to light situations of inequality and injustice within our society is important. Public speaking has been used throughout history to point out inequality and injustice, from Patrick Henry arguing against the way the English government treated the American colonists and Sojourner Truth describing the evils of slavery to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech and Army Lt. Dan Choi’s speeches arguing that the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell policy” is unjust. Many social justice movements have started because young public speakers have decided to stand up for what they believe is fair and just.

We Advocate Sharing Information, Opinions, and Feelings When Facing Significant Choices While Also Respecting Privacy and Confidentiality

This ethical principle involves balancing personal disclosure with discretion. It is perfectly normal for speakers to want to share their own personal opinions and feelings about a topic; however, it is also important to highlight information within a speech that represents your own thoughts and feelings. Your listeners have a right to know the difference between facts and personal opinions.

Similarly, we have an obligation to respect others’ privacy and confidentiality when speaking. If information is obtained from printed or publicly distributed material, it’s perfectly appropriate to use that information without getting permission, as long as you cite it. However, when you have a great anecdote one of your friends told you in confidence, or access to information that is not available to the general public, it is best to seek permission before using the information in a speech.

This ethical obligation even has legal implications in many government and corporate contexts. For example, individuals who work for the Central Intelligence Agency are legally precluded from discussing their work in public without prior review by the agency. And companies such as Google also have policies requiring employees to seek permission before engaging in public speaking in which sensitive information might be leaked.

We Accept Responsibility for the Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Our Own Communication and Expect the Same of Others

The last statement of NCA’s ethical credo may be the most important one. We live in a society where a speaker’s message can literally be heard around the world in a matter of minutes, thanks to our global communication networks. Extreme remarks made by politicians, media commentators, and celebrities, as well as ordinary people, can unexpectedly “go viral” with regrettable consequences. It is not unusual to see situations where a speaker talks hatefully about a specific group, but when one of the speaker’s listeners violently attacks a member of the group, the speaker insists that he or she had no way of knowing that this could possibly have happened. Washing one’s hands of responsibility is unacceptable: all speakers should accept responsibility for the short-term and long-term consequences of their speeches. Although it is certainly not always the speaker’s fault if someone commits an act of violence, the speaker should take responsibility for her or his role in the situation. This process involves being truly reflective and willing to examine how one’s speech could have tragic consequences.

Furthermore, attempting to persuade a group of people to take any action means you should make sure that you understand the consequences of that action. Whether you are persuading people to vote for a political candidate or just encouraging them to lose weight, you should know what the short-term and long-term consequences of that decision could be. While our predictions of short-term and long-term consequences may not always be right, we have an ethical duty to at least think through the possible consequences of our speeches and the actions we encourage.

Practicing Ethical Public Speaking

Thus far in this section we’ve introduced you to the basics of thinking through the ethics of public speaking. Knowing about ethics is essential, but even more important to being an ethical public speaker is putting that knowledge into practice by thinking through possible ethical pitfalls prior to standing up and speaking out. Table 2.1 “Public Speaking Ethics Checklist” is a checklist based on our discussion in this chapter to help you think through some of these issues.

Table 2.1 Public Speaking Ethics Checklist

Key Takeaways

- All eight of the principles espoused in the NCA Credo for Ethical Communication can be applied to public speaking. Some of the principles relate more to the speaker’s role in communication, while others relate to both the speaker’s and the audience’s role in public speech.

- When preparing a speech, it is important to think about the ethics of public speaking from the beginning. When a speaker sets out to be ethical in his or her speech from the beginning, arriving at ethical speech is much easier.

- Fill out the “Public Speaking Ethics Checklist” while thinking about your first speech. Did you mark “true” for any of the statements? If so, why? What can you do as a speaker to get to the point where you can check them all as “false”?

- Robert is preparing a speech about legalizing marijuana use in the United States. He knows that his roommate wrote a paper on the topic last semester and asks his roommate about the paper in an attempt to gather information. During his speech, Robert orally cites his roommate by name as a source of his information but does not report that the source is his roommate, whose experience is based on writing a paper. In what ways does Robert’s behavior violate the guidelines set out in the NCA Credo for Ethical Communication?

American Psychological Association. (2001). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author, p. 349.

Associated Press. (2011, May 5). Conn. shekel shellacking. New York Post .

Shiffrin, S. H. (1999). Dissent, injustice and the meanings of America . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Speech from Dr. Stavros Thomadakis, IESBA Chair: Ethics, Professionalism and the Public Interest

A. INTRODUCTION

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am very happy to be in Beijing and to address distinguished representatives of the Accounting Profession today.

My presentation coincides with the celebration of the “Year of Professionalism”. It is appropriate and a great opportunity to share with you my perspectives on the significance of Ethics to professional judgment and professional practice; and on the positioning of ethical practices by accountants in the global context.

The financial crisis that shook markets ten years ago, and many corporate and financial scandals and misbehaviors that have occurred since then around the world, have been met by a variety of responses - policies and regulations. They have left however a lingering feeling of doubt and mistrust of the way markets work and of the way professionals who support markets, in the private and public sectors, choose their actions.

Trust is essential for smooth functioning of financial markets and, more broadly, of economic mechanisms. The buildup and maintenance of trust are not a momentary exercise nor can trust occur by declaration or decree. It takes time, consistency, mutual respect between contracting parties, and accountability, private and public. It is a long process with long-term consequences, either when it is preserved or when it is broken.

Trust is the pinnacle of a good professional reputation, both individual and collective for a whole profession. Especially in the case of widely practiced and visible professions - such as the Accounting Profession - a few misbehaving members may bring discredit to a whole profession. Professions need to be perceived collectively as reputable, i.e. dependable, competent, fair and honest, in order to maintain their trustful status in economies and enable their individual members to play their significant role in the economy and society.

If we examine carefully the policies and regulations that have been instituted around the world in the aftermath of financial crisis, we discover that most are shaped around agendas of reestablishing trust.

In the context of rebuilding trust, a renewed notion of “public interest” has emerged and has acquired sharp and specific planetary dimensions: financial and fiscal stability, inclusive growth and environmental sustainability are now understood as goals that transcend national boundaries, striving to attain a “global common good”. Public expectations as well as policies are increasingly responding to these goals.

The accounting profession is the clearest and most important case of a profession whose role is paramount for the economic function; whose commitment to the public interest is an explicit responsibility; and whose “professionalism” is embedded and articulated in a comprehensive and globally accepted Code of Ethics.

In our times, professionalism cannot be understood without Ethics. Professionals, such as accountants, who interact with clients, stakeholders and decision-makers have to be ethical, and be perceived as ethical, in their social environment. Being ethical means simply to make judgments that embody ethical fundamental principles and reflect public interest goals. Being perceived as ethical means, in effect, that behavior is seen as above reproach and trustworthy.

In times of complex economic activity, difficult choices, dilemmas and challenges arise. The professional accountant must have recourse to an authoritative source-document guiding judgment and behavior. That is the Code of Ethics. The accountants’ code of ethics is not simply something we learned some time ago for our examinations and then left it on the bookshelves to collect dust. It is an everyday guide for judgments and actions. Compliance with the Code is a constant duty of the accountant either as an auditor or in any other role.

The International Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants , which was first formulated under the auspices of the International Federation of Accountants ( IFAC ) in the late 1970s, has now evolved into a comprehensive and coherent framework for judgment and behavior. The Code of Ethics openly designates that upholding the public interest is a supreme responsibility of accountants in all their roles, and that is ultimately the bedrock of public trust in the profession.

I want to reemphasize this important point: in our world of repeated crises – corporate and financial – public perceptions of the duties of accountants, auditors and corporate officers have strongly shifted towards the need for ethics; ethical thinking and ethical doing. The centrality of Ethics is constantly being underlined in many quarters of international public opinion. This has increased our responsibilities as ethics standard setters to strengthen relevance, visibility and awareness of the Code, as well as making its contents more robust.

A global Code of Ethics that is applied uniformly in every jurisdiction and holds for auditors and accountants is today an indispensable instrument for economies, markets and states. In the present and future, ethics will be a major priority for the accounting profession.

I know, and am very pleased, that the International Code of Ethics is adopted as the basis of the Code that applies to the Chinese accounting profession. This is very significant not only in itself, but also because China is a big and globally influential country, a member of the G-20 and active in all international organizations; and it is of course important that the Code applied by the Chinese accounting profession remains relevant and up to date in a changing environment with new challenges.

So, it is my intention to present to you today the way in which the IESBA is constituted and works in order to produce a high quality, relevant and authoritative Code of Ethics; to discuss the new Restructured and Revised Code, including Independence Requirements for auditors, as it has just become effective; to report the most recent update on global adoption of the Code;

and to discuss the vision and future directions of IESBA’s continuing work on strengthening the Code.

I will conclude my presentation with few thoughts on two areas of challenge: new “disruptive technology”, and the need for uniform implementation of the Code within and across national boundaries combined with ethical leadership.

B. IESBA: AN INDEPENDENT AND AUTHORITATIVE STANDARD SETTER

The International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants ( IESBA ) is an independent standard setting body, diversified professionally and geographically. It is the recognized global body that issues the standards of Ethics for all professional accountants, including auditors.

The Board is made up of 18 members, men and women from all continents, eight of them are practitioners from the profession, and ten are non-practitioners and public members. The chairman is independent and a public member. All members are committed to act in the public interest, which is the overarching objective of the Code. Members are volunteers assisted by technical advisers.

The quality of IESBA’s work is contingent on the qualities and personalities of its volunteer members. To be a successful member a person must have integrity, expertise, collaborative ability and capacity to articulate arguments; also, a perspective that expands beyond national boundaries and an understanding of the accounting profession and its regulation. Members are elected for three-year terms rotating after six years. An independent mindset and a public interest commitment are paramount. At present we do not have a member from China, and we would be happy to consider valid candidacies of worthy individuals from this country.

IESBA is supported by resources that IFAC provides; however, IESBA, as well as its sister Board the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board ( IAASB ), operates independently of IFAC in its objectives, its processes, its choice of agenda and in the determination of its new or revised standards. That is why we talk of the “IESBA Code”, not the “IFAC Code”. IESBA works under the oversight of the Public Interest Oversight Board ( PIOB ), which is itself made up of independent members appointed by global regulatory organizations. The PIOB monitors and certifies that due process is followed, and the standards respond to the public interest.

In order to carry out its work, IESBA undertakes broad consultation with stakeholders around the world, including regulators, national standard setters, professional accounting organizations, firms, investors, corporate governance representatives, preparers of financial statements, and international organizations. The standards and the guidance that it issues take into account perspectives from around the world. This makes them broadly applicable. IESBA standards are principle-based and are designed for global application.

The International Code of Ethics, including the standards for auditor Independence, is adopted or used as a basis for national ethics standards by 120 jurisdictions around the world. It is also adopted by the largest 32 international network audit firms for their transnational audits . This means wide acceptance and application. We invite all jurisdictions and countries around the world to join this large community by adopting the International Code.

C. ESSENTIALS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ETHICS

The overarching objective of the Code is to define and pursue behaviors that serve the public interest and produce trust in the accounting profession.

The foundational presumption upon which the Code rests is that accountants and auditors do not simply apply rules, but rather, they exercise professional judgment on all the issues they tackle in their tasks. In exercising this judgment, the public interest is an overarching objective.

Five fundamental principles are the basis on which the Code is developed: Integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, professional behavior and confidentiality.

The Code includes a conceptual framework that describes the threats to compliance with those principles, as well as requirements and guidance for all professional accountants about how to comply. It also includes requirements for auditor Independence, as an important and special area for application of the fundamental principles.

The Code is thus all about professional accountants’ responsibility. Compliance with the Code – and quality of service as well – requires active, perceptive and responsible individuals applying it.

One of your colleagues once asked me why the Code is called a Code rather than simply “standards of ethics”. The answer is simple. The entire Code flows from a need to define an ethical mindset and to assist ethical judgments in all professional situations. Furthermore, the entire Code flows from a tight core of the five fundamental principles. It is therefore cohesive in that all its provisions relate to the fundamental principles and compliance with them. Ethical behavior is unified, and the Code is a whole of interrelated parts not a sum of unrelated requirements.

Of course, we must recognize that active, perceptive and responsible individuals are not self- sufficient or solo actors. They certainly need courage when addressing ethical dilemmas or conflicts, but they also need the support of their teams, their colleagues and their organizations. In that regard, the Code’s requirements and guidance extend to the responsibility of engagement teams and accounting firms.

- The Code seeks to elevate the ethical bar of the profession.

- The Code applies to large as well as small audit practices.

- The Code applies to all audits, those of Public Interest Entities and those of all other entities.

- The Code applies to auditor as well as non-audit roles, e.g., professional accountants in business and in government.

- The Code applies to developed as well as developing and emerging markets and economies.

D. RESTRUCTURING AND REVISION: THE NEW CODE OF 2018

In April 2018, we issued the Restructured International Code of Ethics including the International Independence Standards. This is the newest and most advanced version of the Code. We urge all adopters of the Code to move swiftly to adoption of the new Code.

The restructuring of the Code was a big project motivated by the strong desire of the Board to respond to new challenges and by the recommendation by many stakeholders, including users and regulators, to make the Code easier to understand, use, translate and enforce.

So, we undertook a complete rewriting of the Code with simpler language, clearer distinction between requirements and application material, and more and sharper examples. The architecture of the Code was also revamped into four parts, as follows:

- Fundamental Principles and Conceptual Framework

- Professional Accountants in Business

- Professional Accountants in Public Practice

- International Independence Standards

The Code ends with an accompanying Glossary of terms and definitions. This has also been enhanced and enriched compared to earlier versions.

The basic user principle running through the Code is that all requirements for any particular aspect of practice must be complied with, but that in every case, and in accordance with the conceptual framework, the accountant must “step back” and ensure that he/she has complied with all five fundamental principles.

Besides the restructuring exercise which involved new writing conventions and a total revamping of wording and text structure, the version of the Code released in April 2018 also includes many significant revisions and new standards that respond to new circumstances and emerging public perceptions.

The foremost examples of those are:

- The standard on “Non-compliance with Laws and Regulations” ( NOCLAR for short) that describes the duties of an accountant when becoming aware of a serious noncompliance in the course of his or her work; this standard, which covers auditors and all other accountants, allows the professional to bypass the principle of confidentiality and report to an appropriate authority serious non-compliance that may place at risk of harm organizations and their stakeholders.

- The standard on partner rotation due to Long Association between auditor and client; the revision of this standard extends the “cooling – off period” for audit engagement partners to five years; it also imposes new restrictions on any other engagement of the partner with the client during the cooling-off period. This revision strengthens independence requirements.

- The standard on “ inducements ” which expands the earlier coverage of “gifts and hospitality” to all forms of inducement (including for example bribery and corruption) and forbids acceptance or offer of inducements to engage in unethical behavior, by failing to comply with the fundamental principles.

- Revised and clarified standards on safeguards for auditor independence that are aligned more directly with well-defined threats to independence such as self-interest, familiarity, self-review, advocacy etc.

- New provisions about preparing or presenting information , which strengthen the role of accountants as guardians of the quality of information shared with stakeholders and the public at large.

- New guidance on professional judgment and professional skepticism , recognizing that these are fundamental attributes which must be exercised by professional accountants in auditor or non-auditor roles.

Altogether these revisions enhance the Code’s robustness and specify clear new ethical requirements that raise the ethical bar for the accounting profession The Restructured and Revised Code became effective on June 15, 2019. Already, there is a significant number of jurisdictions that have moved to adopt this new version of the Code, including Australia, the UK, Japan, South Africa, India and New Zealand to name a few.

Many others are actively working to introduce the new Code into their national standards, notably several European countries, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Brazil and Korea. China is also among those working in that direction, by revising its extant Code. We wish you rapid and good progress in that endeavor.

Finally, the Restructured Code has already been adopted by the 32 largest networks of accounting firms in relation to transnational audits. On the whole, there is impressive global momentum for adoption of the Restructured Code.

Let me also point out that some jurisdictions have ethical requirements of their own, but adopt the International Code. Using the International Code as a basis, they add on more stringent or specific requirements that fit their experiences. In this way they align with international practice but retain desired national features. The International Code is a principle–based Code and fits well with such circumstances.

The Chinese Code is a good example in which the International Code is adopted but fortified by more stringent requirements on partner rotation and on family relations with respect to independence, for example. This is acceptable from our perspective since additional requirements are more stringent than the Code and responsive to specific Chinese circumstances that remain within the Code’s fundamental principles, respect the Codes architecture and neither dilute nor modify its overarching objectives.

As the new Code has now become effective, the IESBA is devoting considerable effort to facilitate the rollout and global adoption of the Restructured Code. On our webpage, you can find tools and resources such as slide decks, frequently asked questions (FAQs), videos, webcasts and brochures that explain the content and the advantages of the new Code. These are accessible and very useful tools for answering questions and clarifying the Code to facilitate adoption and use.

E. THE eCODE: A VALUABLE TOOL FOR USERS

The IESBA has also released a new digital tool that greatly facilitates understanding, use and training on the Restructured Code: an eCode . This is a tool delivered at the same time as the new Code came into effect, last June.

The eCode presents functionalities such as copy and paste, drilling down to details for each section of the Code, a smart search facility, cross-referencing and links to non-authoritative documents (FAQs, explanatory memos, bases for conclusions etc.) among other features. It is freely available to all users on the website of IESBA. It is in English but its platform will be available for translated versions developed by national standard setters. Translations into several languages are already being prepared, as I am told.

We believe the eCode will multiply the accessibility and the navigation across the Code’s sections; experimenting with its features will become itself a learning tool. The ability to cut and paste will enable the customization of features most needed, for example by firms, audit inspectors, academics or other users. So, we invite and urge you all to become familiar with the eCode, by visiting our webpage in the coming days and months.

Finally, let me point out that the eCode will not be a static tool. It will have a capability to collect feedback from users and point us to improvements that will be more directed to users’ needs and preferences. Thus, it will be a dynamic tool that will evolve with use: a “living and learning” functionality.

F. WORKING FOR THE FUTURE

As an independent standard setting Board, IESBA has formulated its new five–year “ strategy and work plan ” (SWP) that extends from 2019 to 2023. This was achieved after extensive international consultation with stakeholder communities such as national standard setters, regulators, audit firms and accounting organizations, investors and academics. The Strategy and Work Plan embodies the independent priorities that IESBA has formulated and that will guide its effort over the period until 2023.

In other words, this is our program for the future. As I said, it reflects views and recommendations of the large community of stakeholders on the basis of our own proposals. The very large participation of stakeholders from around the world in our consultations, roundtables and dialogues has lent explicit legitimacy to our plans for the future.

Let me offer a brief description of the goals, the main themes and the priorities of our program for the future: The broad objective is to maintain the Code as a relevant, robust instrument that is applicable globally; and an instrument that enables the profession, through high ethical behavior, to discharge its primary duties: on one hand, to serve the public interest and, on the other, to reinforce its own international reputation, gaining trust in its capacities and confidence in its value.

In a dynamic and uncertain world, the Code of Ethics must be responsive to underlying and ongoing forces of change that shape new realities: Technology is one such force. Advances in Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence already reshape the audit function, business models and methods of service delivery. (I will come back to technology in a few minutes.)

The other force of change comes from shifting public expectations and perceptions: the responsibilities of accountants and auditors are held up to a higher standard of expectations vis- a–vis the public and the public interest. Corporate failures and market crises, corruption and malfeasance elevate the centrality of ethics everywhere.

In tandem with these major themes, the IESBA has incorporated in its plan a major and pervasive work stream on “technology and ethics”. This work stream seeks to reexamine how technological progress will create risks and opportunities to compliance with fundamental ethical principles; and how such fundamental imperatives as independence and professional skepticism will be applied in the new technological environment.

Other projects that we are currently working on or will soon undertake relate mostly to independence; more specifically, the IESBA is already working on:

- The provision of non-audit services to audit clients, (prohibiting self-review situations, as no safeguards can be applied)

- The level and structure of fees charged by audit firms, (imposing requirements on the level of audit fees not being influenced by other services provided to the client, transparency about fees and restrictions on fee dependence)

- The role and mindset of the professional accountant, (explaining that beyond auditors who need to apply professional skepticism, all accountants must exhibit an inquiring mind during their work.

- The definition of a “public interest entity”, (current definition needs revision, alignment with similar concept in International Standards on Auditing (ISAs), and recognition of differences in the intensity of requirements between PIEs and non-PIEs)

- The ethics of tax advisers, which is another strong example of a project directed to expected public-interest behavior of accountants

- All these current projects respond to strong public expectations about the independence of auditors, and the ethical conduct of professional accountants in different roles and capacities.

Furthermore, the IESBA is planning to conduct implementation reviews of the Restructured Code, as well as two recently issued and far-reaching standards, NOCLAR and Long Association.

One can easily discern in this summary of IESBA’s Strategy and Work Plan a very clear determination to tackle the most significant challenges that emerging technologies and societal expectations pose to the conduct and duties of all accounting professionals, auditors and non- auditors alike.

G. RECOGNIZING THE SYNERGY OF ETHICS AND ISAs

The areas of Independence and professional skepticism, and of the exercise of professional judgment to achieve high audit quality, are areas in which the standards of Audit (ISAs) and Ethics (the Code) overlap and work together.