Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Search entire site

- Search for a course

- Browse study areas

Analytics and Data Science

- Data Science and Innovation

- Postgraduate Research Courses

- Business Research Programs

- Undergraduate Business Programs

- Entrepreneurship

- MBA Programs

- Postgraduate Business Programs

Communication

- Animation Production

- Business Consulting and Technology Implementation

- Digital and Social Media

- Media Arts and Production

- Media Business

- Media Practice and Industry

- Music and Sound Design

- Social and Political Sciences

- Strategic Communication

- Writing and Publishing

- Postgraduate Communication Research Degrees

Design, Architecture and Building

- Architecture

- Built Environment

- DAB Research

- Public Policy and Governance

- Secondary Education

- Education (Learning and Leadership)

- Learning Design

- Postgraduate Education Research Degrees

- Primary Education

Engineering

- Civil and Environmental

- Computer Systems and Software

- Engineering Management

- Mechanical and Mechatronic

- Systems and Operations

- Telecommunications

- Postgraduate Engineering courses

- Undergraduate Engineering courses

- Sport and Exercise

- Palliative Care

- Public Health

- Nursing (Undergraduate)

- Nursing (Postgraduate)

- Health (Postgraduate)

- Research and Honours

- Health Services Management

- Child and Family Health

- Women's and Children's Health

Health (GEM)

- Coursework Degrees

- Clinical Psychology

- Genetic Counselling

- Good Manufacturing Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Speech Pathology

- Research Degrees

Information Technology

- Business Analysis and Information Systems

- Computer Science, Data Analytics/Mining

- Games, Graphics and Multimedia

- IT Management and Leadership

- Networking and Security

- Software Development and Programming

- Systems Design and Analysis

- Web and Cloud Computing

- Postgraduate IT courses

- Postgraduate IT online courses

- Undergraduate Information Technology courses

- International Studies

- Criminology

- International Relations

- Postgraduate International Studies Research Degrees

- Sustainability and Environment

- Practical Legal Training

- Commercial and Business Law

- Juris Doctor

- Legal Studies

- Master of Laws

- Intellectual Property

- Migration Law and Practice

- Overseas Qualified Lawyers

- Postgraduate Law Programs

- Postgraduate Law Research

- Undergraduate Law Programs

- Life Sciences

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences

- Postgraduate Science Programs

- Science Research Programs

- Undergraduate Science Programs

Transdisciplinary Innovation

- Creative Intelligence and Innovation

- Diploma in Innovation

- Transdisciplinary Learning

- Postgraduate Research Degree

Sample written assignments

Look at sample assignments to help you develop and enhance your academic writing skills.

How to use this page

This page features authentic sample assignments that you can view or download to help you develop and enhance your academic writing skills.

PLEASE NOTE: Comments included in these sample written assignments are intended as an educational guide only. Always check with academic staff which referencing convention you should follow. All sample assignments have been submitted using Turnitin® (anti-plagiarism software). Under no circumstances should you copy from these or any other texts.

Annotated bibliography

Annotated Bibliography: Traditional Chinese Medicine (PDF, 103KB)

Essay: Business - "Culture is a Tool Used by Management" (PDF, 496KB)

Essay: Business - "Integrating Business Perspectives - Wicked Problem" (PDF, 660KB)

Essay: Business - "Overconsumption and Sustainability" (PDF, 762KB)

Essay: Business - "Post bureaucracy vs Bureaucracy" (PDF, 609KB)

Essay: Design, Architecture & Building - "Ideas in History - Postmodernism" (PDF, 545KB)

Essay: Design, Architecture & Building - "The Context of Visual Communication Design Research Project" (PDF, 798KB)

Essay: Design, Architecture & Building - "Ideas in History - The Nurses Walk and Postmodernism" (PDF, 558KB)

Essay: Health (Childhood Obesity ) (PDF, 159KB)

Essay: Health (Improving Quality and Safety in Healthcare) (PDF, 277KB)

Essay: Health (Organisational Management in Healthcare) (PDF, 229KB)

UTS HELPS annotated Law essay

(PDF, 250KB)

Essay: Science (Traditional Chinese Medicine) (PDF, 153KB)

Literature review

Literature Review: Education (Critical Pedagogy) (PDF, 165KB)

Reflective writing

Reflective Essay: Business (Simulation Project) (PDF, 119KB)

Reflective Essay: Nursing (Professionalism in Context) (PDF, 134KB)

Report: Business (Management Decisions and Control) (PDF, 244KB)

Report: Education (Digital Storytelling) (PDF, 145KB)

Report: Education (Scholarly Practice) (PDF, 261KB)

Report: Engineering Communication (Flood Mitigation & Water Storage) (PDF, 1MB)

UTS acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the Boorooberongal people of the Dharug Nation, the Bidiagal people and the Gamaygal people, upon whose ancestral lands our university stands. We would also like to pay respect to the Elders both past and present, acknowledging them as the traditional custodians of knowledge for these lands.

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

Designing Writing Assignments

Designing Writing Assignments designing-assignments

As you think about creating writing assignments, use these five principles:

- Tie the writing task to specific pedagogical goals.

- Note rhetorical aspects of the task, i.e., audience, purpose, writing situation.

- Make all elements of the task clear.

- Include grading criteria on the assignment sheet.

- Break down the task into manageable steps.

You'll find discussions of these principles in the following sections of this guide.

Writing Should Meet Teaching Goals

Working backwards from goals, guidelines for writing assignments, resource: checksheets, resources: sample assignments.

- Citation Information

To guarantee that writing tasks tie directly to the teaching goals for your class, ask yourself questions such as the following:

- What specific course objectives will the writing assignment meet?

- Will informal or formal writing better meet my teaching goals?

- Will students be writing to learn course material, to master writing conventions in this discipline, or both?

- Does the assignment make sense?

Although it might seem awkward at first, working backwards from what you hope the final papers will look like often produces the best assignment sheets. We recommend jotting down several points that will help you with this step in writing your assignments:

- Why should students write in your class? State your goals for the final product as clearly and concretely as possible.

- Determine what writing products will meet these goals and fit your teaching style/preferences.

- Note specific skills that will contribute to the final product.

- Sequence activities (reading, researching, writing) to build toward the final product.

Successful writing assignments depend on preparation, careful and thorough instructions, and on explicit criteria for evaluation. Although your experience with a given assignment will suggest ways of improving a specific paper in your class, the following guidelines should help you anticipate many potential problems and considerably reduce your grading time.

- Explain the purpose of the writing assignment.

- Make the format of the writing assignment fit the purpose (format: research paper, position paper, brief or abstract, lab report, problem-solving paper, etc.).

II. The assignment

- Provide complete written instructions.

- Provide format models where possible.

- Discuss sample strong, average, and weak papers.

III. Revision of written drafts

Where appropriate, peer group workshops on rough drafts of papers may improve the overall quality of papers. For example, have students critique each others' papers one week before the due date for format, organization, or mechanics. For these workshops, outline specific and limited tasks on a checksheet. These workshops also give you an opportunity to make sure that all the students are progressing satisfactorily on the project.

IV. Evaluation

On a grading sheet, indicate the percentage of the grade devoted to content and the percentage devoted to writing skills (expression, punctuation, spelling, mechanics). The grading sheet should indicate the important content features as well as the writing skills you consider significant.

Visitors to this site are welcome to download and print these guidelines

Checksheet 1: (thanks to Kate Kiefer and Donna Lecourt)

- written out the assignment so that students can take away a copy of the precise task?

- made clear which course goals this writing task helps students meet?

- specified the audience and purpose of the assignment?

- outlined clearly all required sub-parts of the assignment (if any)?

- included my grading criteria on the assignment sheet?

- pointed students toward appropriate prewriting activities or sources of information?

- specified the format of the final paper (including documentation, headings or sections, page layout)?

- given students models or appropriate samples?

- set a schedule that will encourage students to review each other's drafts and revise their papers?

Checksheet 2: (thanks to Jean Wyrick)

- Is the assignment written clearly on the board or on a handout?

- Do the instructions explain the purpose(s) of the assignment?

- Does the assignment fit the purpose?

- Is the assignment stated in precise language that cannot be misunderstood?

- If choices are possible, are these options clearly marked?

- Are there instructions for the appropriate format? (examples: length? typed? cover sheet? type of paper?)

- Are there any special instructions, such as use of a particular citation format or kinds of headings? If so, are these clearly stated?

- Is the due date clearly visible? (Are late assignments accepted? If so, any penalty?)

- Are any potential problems anticipated and explained?

- Are the grading criteria spelled out as specifically as possible? How much does content count? Organization? Writing skills? One grade or separate grades on form and content? Etc.

- Does the grading criteria section specifically indicate which writing skills the teacher considers important as well as the various aspects of content?

- What part of the course grade is this assignment?

- Does the assignment include use of models (strong, average, weak) or samples outlines?

Sample Full-Semester Assignment from Ag Econ 4XX

Good analytical writing is a rigorous and difficult task. It involves a process of editing and rewriting, and it is common to do a half dozen or more drafts. Because of the difficulty of analytical writing and the need for drafting, we will be completing the assignment in four stages. A draft of each of the sections described below is due when we finish the class unit related to that topic (see due dates on syllabus). I will read the drafts of each section and provide comments; these drafts will not be graded but failure to pass in a complete version of a section will result in a deduction in your final paper grade. Because of the time both you and I are investing in the project, it will constitute one-half of your semester grade.

Content, Concepts and Substance

Papers will focus on the peoples and policies related to population, food, and the environment of your chosen country. As well as exploring each of these subsets, papers need to highlight the interrelations among them. These interrelations should form part of your revision focus for the final draft. Important concepts relevant to the papers will be covered in class; therefore, your research should be focused on the collection of information on your chosen country or region to substantiate your themes. Specifically, the paper needs to address the following questions.

- Population - Developing countries have undergone large changes in population. Explain the dynamic nature of this continuing change in your country or region and the forces underlying the changes. Better papers will go beyond description and analyze the situation at hand. That is, go behind the numbers to explain what is happening in your country with respect to the underlying population dynamics: structure of growth, population momentum, rural/urban migration, age structure of population, unanticipated populations shocks, etc. DUE: WEEK 4.

- Food - What is the nature of food consumption in your country or region? Is the average daily consumption below recommended levels? Is food consumption increasing with economic growth? What is the income elasticity of demand? Use Engel's law to discuss this behavior. Is production able to stay abreast with demand given these trends? What is the nature of agricultural production: traditional agriculture or green revolution technology? Is the trend in food production towards self-sufficiency? If not, can comparative advantage explain this? Does the country import or export food? Is the politico-economic regime supportive of a progressive agricultural sector? DUE: WEEK 8.

- Environment - This is the third issue to be covered in class. It is crucial to show in your paper the environmental impact of agricultural production techniques as well as any direct impacts from population changes. This is especially true in countries that have evolved from traditional agriculture to green revolution techniques in the wake of population pressures. While there are private benefits to increased production, the use of petroleum-based inputs leads to environmental and human health related social costs which are exacerbated by poorly defined property rights. Use the concepts of technological externalities, assimilative capacity, property rights, etc. to explain the nature of this situation in your country or region. What other environmental problems are evident? Discuss the problems and methods for economically measuring environmental degradation. DUE: WEEK 12.

- Final Draft - The final draft of the project should consider the economic situation of agriculture in your specified country or region from the three perspectives outlined above. Key to such an analysis are the interrelationships of the three perspectives. How does each factor contribute to an overall analysis of the successes and problems in agricultural policy and production of your chosen country or region? The paper may conclude with recommendations, but, at the very least, it should provide a clear summary statement about the challenges facing your country or region. DUE: WEEK15.

Landscape Architecture 3XX: Design Critique

Critical yet often overlooked components of the landscape architect's professional skills are the ability to critically evaluate existing designs and the ability to eloquently express him/herself in writing. To develop your skills at these fundamental components, you are to professionally critique a built project with which you are personally and directly familiar. The critique is intended for the "informed public" as might be expected to be read in such features in The New York Times or Columbus Monthly ; therefore, it should be insightful and professionally valid, yet also entertaining and eloquent. It should reflect a sophisticated knowledge of the subject without being burdened with professional jargon.

As in most critiques or reviews, you are attempting not only to identify the project's good and bad features but also to interpret the project's significance and meaning. As such, the critique should have a clear "point of view" or thesis that is then supported by evidence (your description of the place) that persuades the reader that your thesis is valid. Note, however, that your primary goal is not to force the reader to agree with your point of view but rather to present a valid discussion that enriches and broadens the reader's understanding of the project.

To assist in the development of the best possible paper, you are to submit a typed draft by 1:00 pm, Monday, February 10th. The drafts will be reviewed as a set and will then serve as a basis of an in-class writing improvement seminar on Friday, February 14th. The seminar will focus on problems identified in the set of drafts, so individual papers will not have been commented on or marked. You may also submit a typed draft of your paper to the course instructor for review and comment at any time prior to the final submission.

Final papers are due at 2:00 pm, Friday, February 23rd.

Animal/Dairy/Poultry Science 2XX: Comparative Animal Nutrition

Purpose: Students should be able to integrate lecture and laboratory material, relate class material to industry situations, and improve their problem-solving abilities.

Assignment 1: Weekly laboratory reports (50 points)

For the first laboratory, students will be expected to provide depth and breadth of knowledge, creativity, and proper writing format in a one-page, typed, double-spaced report. Thus, conciseness will be stressed. Five points total will be possible for the first draft, another five points possible will be given to a student peer-reviewer of the draft, and five final points will be available for a second draft. This assignment, in its entirety, will be due before the first midterm (class 20). Any major writing flaws will be addressed early so that students can grasp concepts stressed by the instructors without major impact on their grades. Additional objectives are to provide students with skills in critically reviewing papers and to acquaint writers and reviewers of the instructors' expectations for assignments 2 and 3, which are weighted much more heavily.

Students will submit seven one-page handwritten reports from each week's previous laboratory. These reports will cover laboratory classes 2-9; note that one report can be dropped and week 10 has no laboratory. Reports will be graded (5 points each) by the instructors for integration of relevant lecture material or prior experience with the current laboratory.

Assignment 2: Group problem-solving approach to a nutritional problem in the animal industry (50 points)

Students will be divided into groups of four. Several problems will be offered by the instructors, but a group can choose an alternative, approved topic. Students should propose a solution to the problem. Because most real-life problems are solved by groups of employees and (or) consultants, this exercise should provide students an opportunity to practice skills they will need after graduation. Groups will divide the assignment as they see fit. However, 25 points will be based on an individual's separate assignment (1-2 typed pages), and 25 points will be based on the group's total document. Thus, it is assumed that papers will be peer-reviewed. The audience intended will be marketing directors, who will need suitable background, illustrations, etc., to help their salespersons sell more products. This assignment will be started in about the second week of class and will be due by class 28.

Assignment 3: Students will develop a topic of their own choosing (approved by instructors) to be written for two audiences (100 points).

The first assignment (25 points) will be written in "common language," e.g., to farmers or salespersons. High clarity of presentation will be expected. It also will be graded for content to assure that the student has developed the topic adequately. This assignment will be due by class 38.

Concomitant with this assignment will be a first draft of a scientific term paper on the same subject. Ten scientific articles and five typed, double-spaced pages are minimum requirements. Basic knowledge of scientific principles will be incorporated into this term paper written to an audience of alumni of this course working in a nutrition-related field. This draft (25 points) will be due by class 38. It will be reviewed by a peer who will receive up to 25 points for his/her critique. It will be returned to the student and instructor by class 43. The final draft, worth an additional 25 points, will be due before class 50 and will be returned to the student during the final exam period.

Integration Papers - HD 3XX

Two papers will be assigned for the semester, each to be no more than three typewritten pages in length. Each paper will be worth 50 points.

Purpose: The purpose of this assignment is to aid the student in learning skills necessary in forming policy-making decisions and to encourage the student to consider the integral relationship between theory, research, and social policy.

Format: The student may choose any issue of interest that is appropriate to the socialization focus of the course, but the issue must be clearly stated and the student is advised to carefully limit the scope of the issue question.

There are three sections to the paper:

First: One page will summarize two conflicting theoretical approaches to the chosen issue. Summarize only what the selected theories may or would say about the particular question you've posed; do not try to summarize the entire theory. Make clear to a reader in what way the two theories disagree or contrast. Your text should provide you with the basic information to do this section.

Second: On the second page, summarize (abstract) one relevant piece of current research. The research article must be chosen from a professional journal (not a secondary source) written within the last five years. The article should be abstracted and then the student should clearly show how the research relates to the theoretical position(s) stated earlier, in particular, and to the socialization issue chosen in general. Be sure the subjects used, methodology, and assumptions can be reasonably extended to your concern.

Third: On the third page, the student will present a policy guideline (for example, the Colorado courts should be required to include, on the child's behalf, a child development specialist's testimony at all custody hearings) that can be supported by the information gained and presented in the first two pages. My advice is that you picture a specific audience and the final purpose or use of such a policy guideline. For example, perhaps as a child development specialist you have been requested to present an informed opinion to a federal or state committee whose charge is to develop a particular type of human development program or service. Be specific about your hypothetical situation and this will help you write a realistic policy guideline.

Sample papers will be available in the department reading room.

SP3XX Short Essay Grading Criteria

A (90-100): Thesis is clearly presented in first paragraph. Every subsequent paragraph contributes significantly to the development of the thesis. Final paragraph "pulls together" the body of the essay and demonstrates how the essay as a whole has supported the thesis. In terms of both style and content, the essay is a pleasure to read; ideas are brought forth with clarity and follow each other logically and effortlessly. Essay is virtually free of misspellings, sentence fragments, fused sentences, comma splices, semicolon errors, wrong word choices, and paragraphing errors.

B (80-89): Thesis is clearly presented in first paragraph. Every subsequent paragraph contributes significantly to the development of the thesis. Final paragraph "pulls together" the body of the essay and demonstrates how the essay as a whole has supported the thesis. In terms of style and content, the essay is still clear and progresses logically, but the essay is somewhat weaker due to awkward word choice, sentence structure, or organization. Essay may have a few (approximately 3) instances of misspellings, sentence fragments, fused sentences, comma splices, semicolon errors, wrong word choices, and paragraphing errors.

C (70-79): There is a thesis, but the reader may have to hunt for it a bit. All the paragraphs contribute to the thesis, but the organization of these paragraphs is less than clear. Final paragraph simply summarizes essay without successfully integrating the ideas presented into a unified support for thesis. In terms of style and content, the reader is able to discern the intent of the essay and the support for the thesis, but some amount of mental gymnastics and "reading between the lines" is necessary; the essay is not easy to read, but it still has said some important things. Essay may have instances (approximately 6) of misspellings, sentence fragments, fused sentences, comma splices, semicolon errors, wrong word choices, and paragraphing errors.

D (60-69): Thesis is not clear. Individual paragraphs may have interesting insights, but the paragraphs do not work together well in support of the thesis. In terms of style and content, the essay is difficult to read and to understand, but the reader can see there was a (less than successful) effort to engage a meaningful subject. Essay may have several instances (approximately 6) of misspellings, sentence fragments, fused sentences, comma splices, semicolon errors, wrong word choices, and paragraphing errors.

Teacher Comments

Patrick Fitzhorn, Mechanical Engineering: My expectations for freshman are relatively high. I'm jaded with the seniors, who keep disappointing me. Often, we don't agree on the grading criteria.

There's three parts to our writing in engineering. The first part, is the assignment itself.

The four types: lab reports, technical papers, design reports, and proposals. The other part is expectations in terms of a growth of writing style at each level in our curriculum and an understanding of that from students so they understand that high school writing is not acceptable as a senior in college. Third, is how we transform our expectations into justifiable grades that have real feedback for the students.

To the freshman, I might give a page to a page and one half to here's how I want the design report. To the seniors it was three pages long. We try to capture how our expectations change from freshman to senior. I bet the structure is almost identical...

We always give them pretty rigorous outlines. Often times, the way students write is to take the outline we give them and students write that chunk. Virtually every writing assignment we give, we provide a writing outline of the writing style we want. These patterns are then used in industry. One organization style works for each of the writing styles. Between faculty, some minute details may change with organization, but there is a standard for writers to follow.

Interviewer: How do students determine purpose

Ken Reardon, Chemical Engineerin: Students usually respond to an assignment. That tells them what the purpose is. . . . I think it's something they infer from the assignment sheet.

Interviewer What types of purposes are there?

Ken Reardon: Persuading is the case with proposals. And informing with progress and the final results. Informing is to just "Here are the results of analysis; here's the answer to the question." It's presenting information. Persuasion is analyzing some information and coming to a conclusion. More of the writing I've seen engineers do is a soft version of persuasion, where they're not trying to sell. "Here's my analysis, here's how I interpreted those results and so here's what I think is worthwhile." Justifying.

Interviewer: Why do students need to be aware of this concept?

Ken Reardon: It helps to tell the reader what they're reading. Without it, readers don't know how to read.

Kiefer, Kate. (1997). Designing Writing Assignments. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/teaching/guide.cfm?guideid=101

Search form

How to write the best college assignments.

By Lois Weldon

When it comes to writing assignments, it is difficult to find a conceptualized guide with clear and simple tips that are easy to follow. That’s exactly what this guide will provide: few simple tips on how to write great assignments, right when you need them. Some of these points will probably be familiar to you, but there is no harm in being reminded of the most important things before you start writing the assignments, which are usually determining on your credits.

The most important aspects: Outline and Introduction

Preparation is the key to success, especially when it comes to academic assignments. It is recommended to always write an outline before you start writing the actual assignment. The outline should include the main points of discussion, which will keep you focused throughout the work and will make your key points clearly defined. Outlining the assignment will save you a lot of time because it will organize your thoughts and make your literature searches much easier. The outline will also help you to create different sections and divide up the word count between them, which will make the assignment more organized.

The introduction is the next important part you should focus on. This is the part that defines the quality of your assignment in the eyes of the reader. The introduction must include a brief background on the main points of discussion, the purpose of developing such work and clear indications on how the assignment is being organized. Keep this part brief, within one or two paragraphs.

This is an example of including the above mentioned points into the introduction of an assignment that elaborates the topic of obesity reaching proportions:

Background : The twenty first century is characterized by many public health challenges, among which obesity takes a major part. The increasing prevalence of obesity is creating an alarming situation in both developed and developing regions of the world.

Structure and aim : This assignment will elaborate and discuss the specific pattern of obesity epidemic development, as well as its epidemiology. Debt, trade and globalization will also be analyzed as factors that led to escalation of the problem. Moreover, the assignment will discuss the governmental interventions that make efforts to address this issue.

Practical tips on assignment writing

Here are some practical tips that will keep your work focused and effective:

– Critical thinking – Academic writing has to be characterized by critical thinking, not only to provide the work with the needed level, but also because it takes part in the final mark.

– Continuity of ideas – When you get to the middle of assignment, things can get confusing. You have to make sure that the ideas are flowing continuously within and between paragraphs, so the reader will be enabled to follow the argument easily. Dividing the work in different paragraphs is very important for this purpose.

– Usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ – According to the academic writing standards, the assignments should be written in an impersonal language, which means that the usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ should be avoided. The only acceptable way of building your arguments is by using opinions and evidence from authoritative sources.

– Referencing – this part of the assignment is extremely important and it takes a big part in the final mark. Make sure to use either Vancouver or Harvard referencing systems, and use the same system in the bibliography and while citing work of other sources within the text.

– Usage of examples – A clear understanding on your assignment’s topic should be provided by comparing different sources and identifying their strengths and weaknesses in an objective manner. This is the part where you should show how the knowledge can be applied into practice.

– Numbering and bullets – Instead of using numbering and bullets, the academic writing style prefers the usage of paragraphs.

– Including figures and tables – The figures and tables are an effective way of conveying information to the reader in a clear manner, without disturbing the word count. Each figure and table should have clear headings and you should make sure to mention their sources in the bibliography.

– Word count – the word count of your assignment mustn’t be far above or far below the required word count. The outline will provide you with help in this aspect, so make sure to plan the work in order to keep it within the boundaries.

The importance of an effective conclusion

The conclusion of your assignment is your ultimate chance to provide powerful arguments that will impress the reader. The conclusion in academic writing is usually expressed through three main parts:

– Stating the context and aim of the assignment

– Summarizing the main points briefly

– Providing final comments with consideration of the future (discussing clear examples of things that can be done in order to improve the situation concerning your topic of discussion).

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Lois Weldon is writer at Uk.bestdissertation.com . Lives happily at London with her husband and lovely daughter. Adores writing tips for students. Passionate about Star Wars and yoga.

7 comments on “How To Write The Best College Assignments”

Extremely useful tip for students wanting to score well on their assignments. I concur with the writer that writing an outline before ACTUALLY starting to write assignments is extremely important. I have observed students who start off quite well but they tend to lose focus in between which causes them to lose marks. So an outline helps them to maintain the theme focused.

Hello Great information…. write assignments

Well elabrated

Thanks for the information. This site has amazing articles. Looking forward to continuing on this site.

This article is certainly going to help student . Well written.

Really good, thanks

Practical tips on assignment writing, the’re fantastic. Thank you!

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

How to Write an Effective Assignment

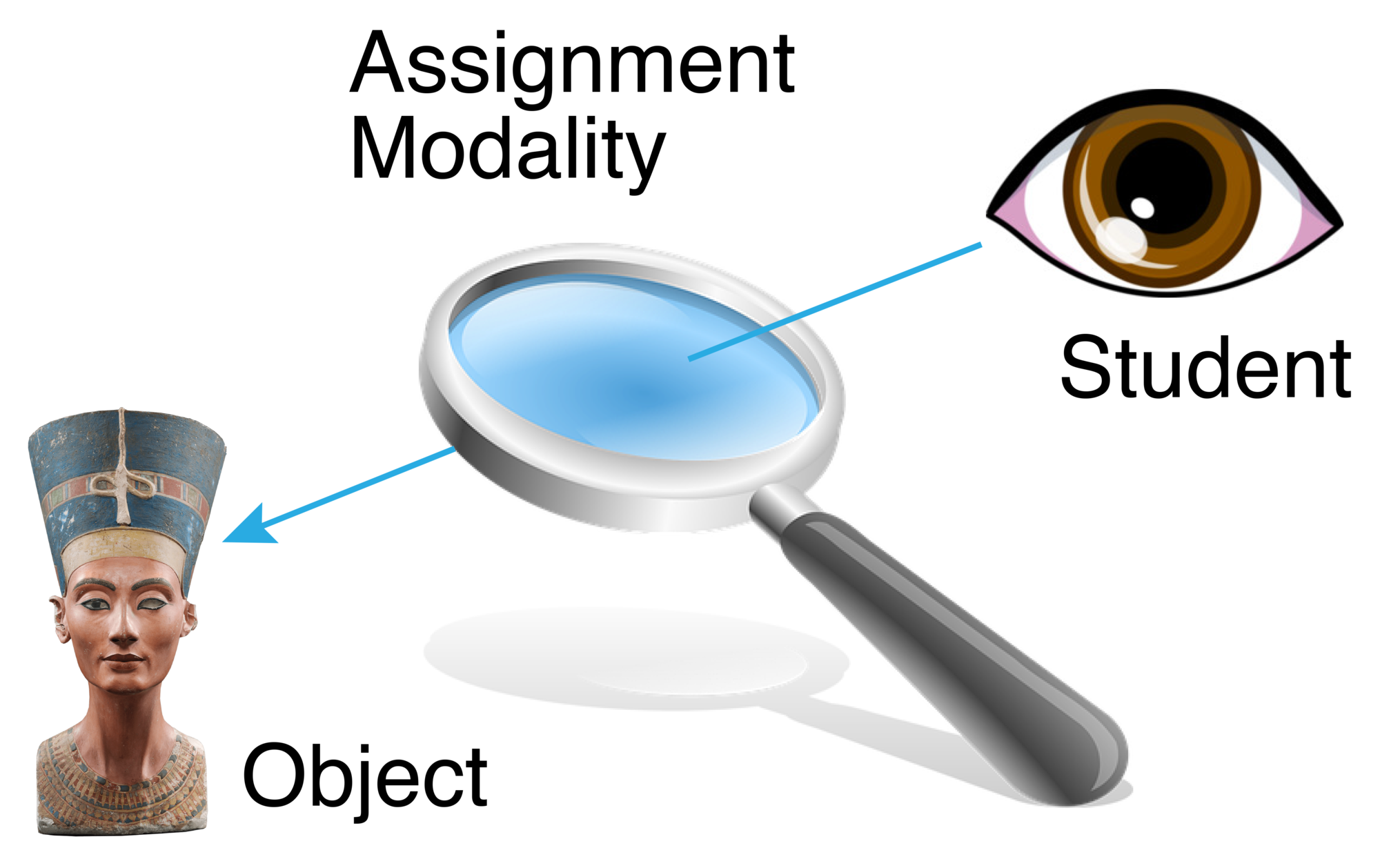

At their base, all assignment prompts function a bit like a magnifying glass—they allow a student to isolate, focus on, inspect, and interact with some portion of your course material through a fixed lens of your choosing.

The Key Components of an Effective Assignment Prompt

All assignments, from ungraded formative response papers all the way up to a capstone assignment, should include the following components to ensure that students and teachers understand not only the learning objective of the assignment, but also the discrete steps which they will need to follow in order to complete it successfully:

- Preamble. This situates the assignment within the context of the course, reminding students of what they have been working on in anticipation of the assignment and how that work has prepared them to succeed at it.

- Justification and Purpose. This explains why the particular type or genre of assignment you’ve chosen (e.g., lab report, policy memo, problem set, or personal reflection) is the best way for you and your students to measure how well they’ve met the learning objectives associated with this segment of the course.

- Mission. This explains the assignment in broad brush strokes, giving students a general sense of the project you are setting before them. It often gives students guidance on the evidence or data they should be working with, as well as helping them imagine the audience their work should be aimed at.

- Tasks. This outlines what students are supposed to do at a more granular level: for example, how to start, where to look, how to ask for help, etc. If written well, this part of the assignment prompt ought to function as a kind of "process" rubric for students, helping them to decide for themselves whether they are completing the assignment successfully.

- Submission format. This tells students, in appropriate detail, which stylistic conventions they should observe and how to submit their work. For example, should the assignment be a five-page paper written in APA format and saved as a .docx file? Should it be uploaded to the course website? Is it due by Tuesday at 5:00pm?

For illustrations of these five components in action, visit our gallery of annotated assignment prompts .

For advice about creative assignments (e.g. podcasts, film projects, visual and performing art projects, etc.), visit our Guidance on Non-Traditional Forms of Assessment .

For specific advice on different genres of assignment, click below:

Response Papers

Problem sets, source analyses, final exams, concept maps, research papers, oral presentations, poster presentations.

- Learner-Centered Design

- Putting Evidence at the Center

- What Should Students Learn?

- Start with the Capstone

- Gallery of Annotated Assignment Prompts

- Scaffolding: Using Frequency and Sequencing Intentionally

- Curating Content: The Virtue of Modules

- Syllabus Design

- Catalogue Materials

- Making a Course Presentation Video

- Teaching Teams

- In the Classroom

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

- Privacy Policy

Home » Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Assignment is a task given to students by a teacher or professor, usually as a means of assessing their understanding and application of course material. Assignments can take various forms, including essays, research papers, presentations, problem sets, lab reports, and more.

Assignments are typically designed to be completed outside of class time and may require independent research, critical thinking, and analysis. They are often graded and used as a significant component of a student’s overall course grade. The instructions for an assignment usually specify the goals, requirements, and deadlines for completion, and students are expected to meet these criteria to earn a good grade.

History of Assignment

The use of assignments as a tool for teaching and learning has been a part of education for centuries. Following is a brief history of the Assignment.

- Ancient Times: Assignments such as writing exercises, recitations, and memorization tasks were used to reinforce learning.

- Medieval Period : Universities began to develop the concept of the assignment, with students completing essays, commentaries, and translations to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the subject matter.

- 19th Century : With the growth of schools and universities, assignments became more widespread and were used to assess student progress and achievement.

- 20th Century: The rise of distance education and online learning led to the further development of assignments as an integral part of the educational process.

- Present Day: Assignments continue to be used in a variety of educational settings and are seen as an effective way to promote student learning and assess student achievement. The nature and format of assignments continue to evolve in response to changing educational needs and technological innovations.

Types of Assignment

Here are some of the most common types of assignments:

An essay is a piece of writing that presents an argument, analysis, or interpretation of a topic or question. It usually consists of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Essay structure:

- Introduction : introduces the topic and thesis statement

- Body paragraphs : each paragraph presents a different argument or idea, with evidence and analysis to support it

- Conclusion : summarizes the key points and reiterates the thesis statement

Research paper

A research paper involves gathering and analyzing information on a particular topic, and presenting the findings in a well-structured, documented paper. It usually involves conducting original research, collecting data, and presenting it in a clear, organized manner.

Research paper structure:

- Title page : includes the title of the paper, author’s name, date, and institution

- Abstract : summarizes the paper’s main points and conclusions

- Introduction : provides background information on the topic and research question

- Literature review: summarizes previous research on the topic

- Methodology : explains how the research was conducted

- Results : presents the findings of the research

- Discussion : interprets the results and draws conclusions

- Conclusion : summarizes the key findings and implications

A case study involves analyzing a real-life situation, problem or issue, and presenting a solution or recommendations based on the analysis. It often involves extensive research, data analysis, and critical thinking.

Case study structure:

- Introduction : introduces the case study and its purpose

- Background : provides context and background information on the case

- Analysis : examines the key issues and problems in the case

- Solution/recommendations: proposes solutions or recommendations based on the analysis

- Conclusion: Summarize the key points and implications

A lab report is a scientific document that summarizes the results of a laboratory experiment or research project. It typically includes an introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

Lab report structure:

- Title page : includes the title of the experiment, author’s name, date, and institution

- Abstract : summarizes the purpose, methodology, and results of the experiment

- Methods : explains how the experiment was conducted

- Results : presents the findings of the experiment

Presentation

A presentation involves delivering information, data or findings to an audience, often with the use of visual aids such as slides, charts, or diagrams. It requires clear communication skills, good organization, and effective use of technology.

Presentation structure:

- Introduction : introduces the topic and purpose of the presentation

- Body : presents the main points, findings, or data, with the help of visual aids

- Conclusion : summarizes the key points and provides a closing statement

Creative Project

A creative project is an assignment that requires students to produce something original, such as a painting, sculpture, video, or creative writing piece. It allows students to demonstrate their creativity and artistic skills.

Creative project structure:

- Introduction : introduces the project and its purpose

- Body : presents the creative work, with explanations or descriptions as needed

- Conclusion : summarizes the key elements and reflects on the creative process.

Examples of Assignments

Following are Examples of Assignment templates samples:

Essay template:

I. Introduction

- Hook: Grab the reader’s attention with a catchy opening sentence.

- Background: Provide some context or background information on the topic.

- Thesis statement: State the main argument or point of your essay.

II. Body paragraphs

- Topic sentence: Introduce the main idea or argument of the paragraph.

- Evidence: Provide evidence or examples to support your point.

- Analysis: Explain how the evidence supports your argument.

- Transition: Use a transition sentence to lead into the next paragraph.

III. Conclusion

- Restate thesis: Summarize your main argument or point.

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your essay.

- Concluding thoughts: End with a final thought or call to action.

Research paper template:

I. Title page

- Title: Give your paper a descriptive title.

- Author: Include your name and institutional affiliation.

- Date: Provide the date the paper was submitted.

II. Abstract

- Background: Summarize the background and purpose of your research.

- Methodology: Describe the methods you used to conduct your research.

- Results: Summarize the main findings of your research.

- Conclusion: Provide a brief summary of the implications and conclusions of your research.

III. Introduction

- Background: Provide some background information on the topic.

- Research question: State your research question or hypothesis.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of your research.

IV. Literature review

- Background: Summarize previous research on the topic.

- Gaps in research: Identify gaps or areas that need further research.

V. Methodology

- Participants: Describe the participants in your study.

- Procedure: Explain the procedure you used to conduct your research.

- Measures: Describe the measures you used to collect data.

VI. Results