Economic Inequality by Gender

How big are the inequalities in pay, jobs, and wealth between men and women? What causes these differences?

By Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Joe Hasell and Max Roser

This page was first published in March 2018 and last revised in March 2024.

On this page, you can find writing, visualizations, and data on how big the inequalities in pay, jobs, and wealth are between men and women, how they have changed over time, and what may be causing them

Although economic gender inequalities remain common and large, they are today smaller than they used to be some decades ago.

Related topics

Women's Employment

How does women’s labor force participation differ across countries? How has it changed over time? What is behind these differences and changes?

Women’s Rights

How has the protection of women’s rights changed over time? How does it differ across countries? Explore global data and research on women’s rights.

Maternal Mortality

What could be more tragic than a mother losing her life in the moment that she is giving birth to her newborn? Why are mothers dying and what can be done to prevent these deaths?

See all interactive charts on economic inequality by gender ↓

How does the gender pay gap look like across countries and over time?

The 'gender pay gap' comes up often in political debates , policy reports , and everyday news . But what is it? What does it tell us? Is it different from country to country? How does it change over time?

Here we try to answer these questions, providing an empirical overview of the gender pay gap across countries and over time.

The gender pay gap measures inequality but not necessarily discrimination

The gender pay gap (or the gender wage gap) is a metric that tells us the difference in pay (or wages, or income) between women and men. It's a measure of inequality and captures a concept that is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal work.

Differences in pay between men and women capture differences along many possible dimensions, including worker education, experience, and occupation. When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male workers to all female workers – irrespective of differences along these additional dimensions – the result is the 'raw' or 'unadjusted' pay gap. On the contrary, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, etc., then the result is the 'adjusted' pay gap.

Discrimination in hiring practices can exist in the absence of pay gaps – for example, if women know they will be treated unfairly and hence choose not to participate in the labor market. Similarly, it is possible to observe large pay gaps in the absence of discrimination in hiring practices – for example, if women get fair treatment but apply for lower-paid jobs.

The implication is that observing differences in pay between men and women is neither necessary nor sufficient to prove discrimination in the workplace. Both discrimination and inequality are important. But they are not the same.

In most countries, there is a substantial gender pay gap

Cross-country data on the gender pay gap is patchy, but the most complete source in terms of coverage is the United Nation's International Labour Organization (ILO). The visualization here presents this data. You can add observations by clicking on the option 'add country' at the bottom of the chart.

The estimates shown here correspond to differences between the average hourly earnings of men and women (expressed as a percentage of average hourly earnings of men), and cover all workers irrespective of whether they work full-time or part-time. 1

As we can see: (i) in most countries the gap is positive – women earn less than men, and (ii) there are large differences in the size of this gap across countries. 2

In most countries, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades

How is the gender pay gap changing over time? To answer this question, let's consider this chart showing available estimates from the OECD. These estimates include OECD member states, as well as some other non-member countries, and they are the longest available series of cross-country data on the gender pay gap that we are aware of.

Here we see that the gap is large in most OECD countries, but it has been going down in the last couple of decades. In some cases the reduction is remarkable. In the United States, for example, the gap declined by more than half.

These estimates are not directly comparable to those from the ILO, because the pay gap is measured slightly differently here: The OECD estimates refer to percent differences in median earnings (i.e. the gap here captures differences between men and women in the middle of the earnings distribution), and they cover only full-time employees and self-employed workers (i.e. the gap here excludes disparities that arise from differences in hourly wages for part-time and full-time workers).

However, the ILO data shows similar trends.

The conclusion is that in most countries with available data, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades.

The gender pay gap is larger for older workers

The United States Census Bureau defines the pay gap as the ratio between median wages – that is, they measure the gap by calculating the wages of men and women at the middle of the earnings distribution, and dividing them.

By this measure, the gender wage gap is expressed as a percent (median earnings of women as a share of median earnings of men) and it is always positive. Here, values below 100% mean that women earn less than men, while values above 100% mean that women earn more. Values closer to 100% reflect a lower gap.

The next chart shows available estimates of this metric for full-time workers in the US, by age group.

First, we see that the series trends upwards, meaning the gap has been shrinking in the last couple of decades. Secondly, we see that there are important differences by age.

The second point is crucial to understanding the gender pay gap: the gap is a statistic that changes during the life of a worker. In most rich countries, it’s small when formal education ends and employment begins, and it increases with age. As we discuss in our analysis of the determinants below, the gender pay gap tends to increase when women marry and when/if they have children.

The gender pay gap is smaller in middle-income countries – which tend to be countries with low labor force participation of women

The chart here plots available ILO estimates on the gender pay gap against GDP per capita. As we can see there is a weak positive correlation between GDP per capita and the gender pay gap. However, the chart shows that the relationship is not really linear. Actually, middle-income countries tend to have the smallest pay gap.

The fact that middle-income countries have low gender wage gaps is, to a large extent, the result of selection of women into employment . Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) explain it as follows: “[I]f women who are employed tend to have relatively high‐wage characteristics, low female employment rates may become consistent with low gender wage gaps simply because low‐wage women would not feature in the observed wage distribution.” 3

Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) show that this pattern holds in the data: unadjusted gender wage gaps across countries tend to be negatively correlated with gender employment gaps. That is, the gender pay gaps tend to be smaller where relatively fewer women participate in the labor force .

So, rather than reflect greater equality, the lower wage gaps observed in some countries could indicate that only women with certain characteristics – for instance, with no husband or children – are entering the workforce.

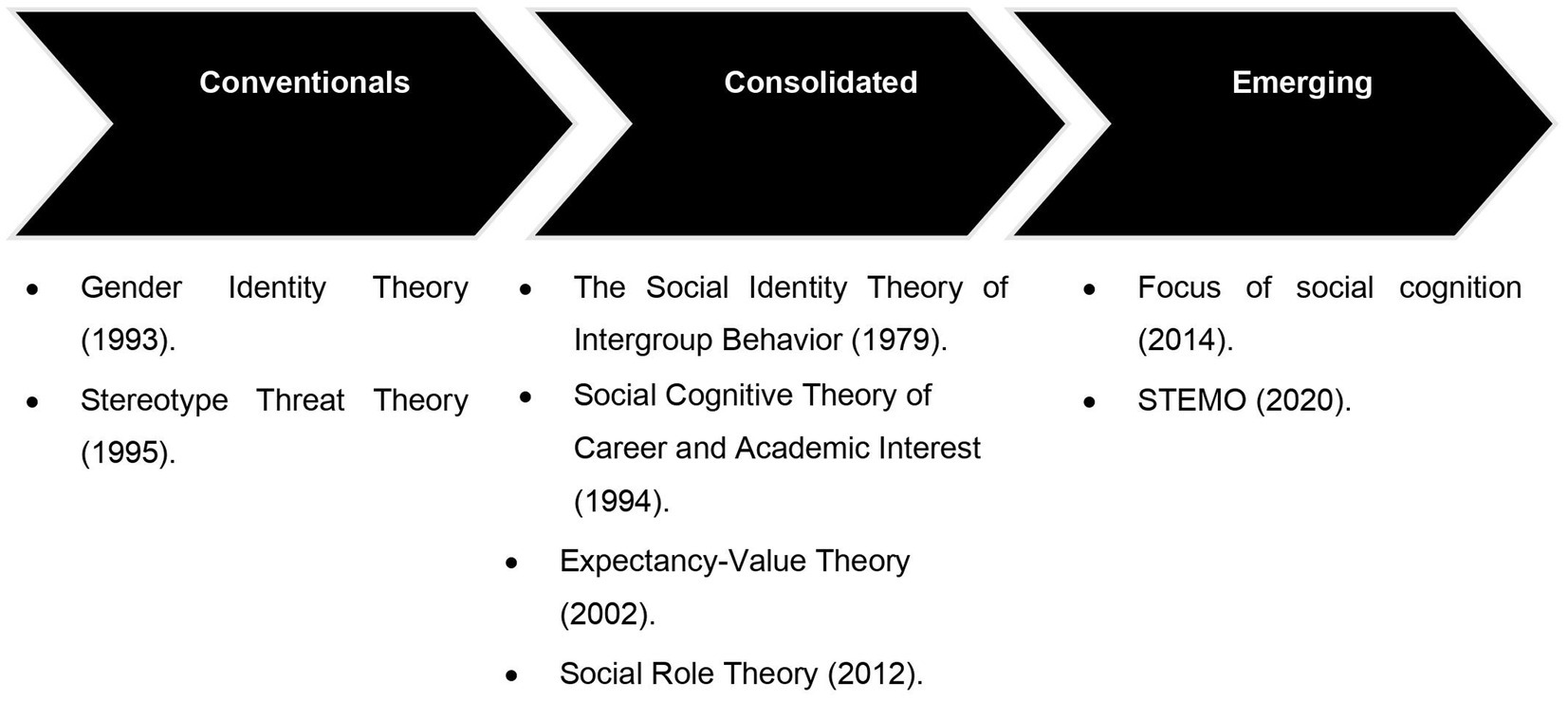

Why is there a gender pay gap?

In almost all countries, if you compare the wages of men and women you find that women tend to earn less than men. These inequalities have been narrowing across the world. In particular, most high-income countries have seen sizeable reductions in the gender pay gap over the last couple of decades.

How did these reductions come about and why do substantial gaps remain?

Before we get into the details, here is a preview of the main points.

- An important part of the reduction in the gender pay gap in rich countries over the last decades is due to a historical narrowing, and often even reversal of the education gap between men and women.

- Today, education is relatively unimportant in explaining the remaining gender pay gap in rich countries. In contrast, the characteristics of the jobs that women tend to do, remain important contributing factors.

- The gender pay gap is not a direct metric of discrimination. However, evidence from different contexts suggests discrimination is indeed important to understand the gender pay gap. Similarly, social norms affecting the gender distribution of labor are important determinants of wage inequality.

- On the other hand, the available evidence suggests differences in psychological attributes and non-cognitive skills are at best modest factors contributing to the gender pay gap.

Differences in human capital

The adjusted pay gap.

Differences in earnings between men and women capture differences across many possible dimensions, including education, experience, and occupation.

For example, if we consider that more educated people tend to have higher earnings, it is natural to expect that the narrowing of the pay gap across the world can be partly explained by the fact that women have been catching up with men in terms of educational attainment, in particular years of schooling.

Indeed, since differences in education partly contribute to explaining differences in wages, it is common to distinguish between 'unadjusted' and 'adjusted' pay differences.

When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male and female workers, irrespective of differences in worker characteristics, the result is the raw or unadjusted pay gap. In contrast to this, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, and other factors that matter for the pay gap, then the result is the adjusted pay gap.

The idea of the adjusted pay gap is to make comparisons within groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure, and education. This allows us to tease out the extent to which different factors contribute to observed inequalities.

The chart here, from Blau and Kahn (2017) shows the evolution of the adjusted and unadjusted gender pay gap in the US. 4

More precisely, the chart shows the evolution of female-to-male wage ratios in three different scenarios: (i) Unadjusted; (ii) Adjusted, controlling for gender differences in human capital, i.e. education and experience; and (iii) Adjusted, controlling for a full range of covariates, including education, experience, job industry, and occupation, among others. The difference between 100% and the full specification (the green bars) is the “unexplained” residual. 5

Several points stand out here.

- First, the unadjusted gender pay gap in the US shrunk over this period. This is evident from the fact that the blue bars are closer to 100% in 2010 than in 1980.

- Second, if we focus on groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure, and education, we also see a narrowing. The adjusted gender pay gap has shrunk.

- Third, we can see that education and experience used to help explain a very large part of the pay gap in 1980, but this changed substantially in the decades that followed. This third point follows from the fact that the difference between the blue and red bars was much larger in 1980 than in 2010.

- And fourth, the green bars grew substantially in the 1980s, but stayed fairly constant thereafter. In other words: Most of the convergence in earnings occurred during the 1980s, a decade in which the "unexplained" gap shrunk substantially.

Education and experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages in the US

The next chart shows a breakdown of the adjusted gender pay gaps in the US, factor by factor, in 1980 and 2010.

When comparing the contributing factors in 1980 and 2010, we see that education and work experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages over time, while occupation and industry have become more important. 6

In this chart we can also see that the 'unexplained' residual has gone down. This means the observable characteristics of workers and their jobs explain wage differences better today than a couple of decades ago. At first sight, this seems like good news – it suggests that today there is less discrimination, in the sense that differences in earnings are today much more readily explained by differences in 'productivity' factors. But is this really the case?

The unexplained residual may include aspects of unmeasured productivity (i.e. unobservable worker characteristics that could not be accounted for in the study), while the "explained" factors may themselves be vehicles of discrimination.

For example, suppose that women are indeed discriminated against, and they find it hard to get hired for certain jobs simply because of their sex. This would mean that in the adjusted specification, we would see that occupation and industry are important contributing factors – but that is precisely because discrimination is embedded in occupational differences!

Hence, while the unexplained residual gives us a first-order approximation of what is going on, we need much more detailed data and analysis in order to say something definitive about the role of discrimination in observed pay differences.

Gender pay differences around the world are better explained by occupation than by education

The set of three maps here, taken from the World Development Report (2012) , shows that today gender pay differences are much better explained by occupation than by education. This is consistent with the point already made above using data for the US: as education expanded radically over the last few decades, human capital has become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages.

Justin Sandefur at the Center for Global Development shows that education also fails to explain wage gaps if we include workers with zero income (i.e. if we decompose the wage gap after including people who are not employed).

Looking beyond worker characteristics

Job flexibility.

All over the world women tend to do more unpaid care work at home than men – and women tend to be overrepresented in low-paying jobs where they have the flexibility required to attend to these additional responsibilities.

The most important evidence regarding this link between the gender pay gap and job flexibility is presented and discussed by Claudia Goldin in the article ' A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter ', where she digs deep into the data from the US. 8 There are some key lessons that apply both to rich and non-rich countries.

Goldin shows that when one looks at the data on occupational choice in some detail, it becomes clear that women disproportionately seek jobs, including full-time jobs, that tend to be compatible with childrearing and other family responsibilities. In other words, women, more than men, are expected to have temporal flexibility in their jobs. Things like shifting hours of work and rearranging shifts to accommodate emergencies at home. And these are jobs with lower earnings per hour, even when the total number of hours worked is the same.

The importance of job flexibility in this context is very clearly illustrated by the fact that, over the last couple of decades, women in the US increased their participation and remuneration in only some fields. In a recent paper, Goldin and Katz (2016) show that pharmacy became a highly remunerated female-majority profession with a small gender earnings gap in the US, at the same time as pharmacies went through substantial technological changes that made flexible jobs in the field more productive (e.g. computer systems that increased the substitutability among pharmacists). 9

The chart here shows how quickly female wages increased in pharmacy, relative to other professions, over the last few decades in the US.

The motherhood penalty

Closely related to job flexibility and occupational choice is the issue of work interruptions due to motherhood. On this front, there is again a great deal of evidence in support of the so-called 'motherhood penalty'.

Lundborg, Plug, and Rasmussen (2017) provide evidence from Denmark – more specifically, Danish women who sought medical help in achieving pregnancy. 10

By tracking women’s fertility and employment status through detailed periodic surveys, these researchers were able to establish that women who had a successful in vitro fertilization treatment, ended up having lower earnings down the line than similar women who, by chance, were unsuccessfully treated.

Lundborg, Plug, and Rasmussen summarise their findings as follows: "Our main finding is that women who are successfully treated by [in vitro fertilization] earn persistently less because of having children. We explain the decline in annual earnings by women working less when children are young and getting paid less when children are older. We explain the decline in hourly earnings, which is often referred to as the motherhood penalty, by women moving to lower-paid jobs that are closer to home."

The fact that the motherhood penalty is indeed about ‘motherhood’ and not ‘parenthood’, is supported by further evidence.

A recent study , also from Denmark, tracked men and women over the period 1980-2013 and found that after the first child, women’s earnings sharply dropped and never fully recovered. But this was not the case for men with children, nor the case for women without children.

These patterns are shown in the chart here. The first panel shows the trend in earnings for Danish women with and without children. The second panel shows the same comparison for Danish men.

Note that these two examples are from Denmark – a country that ranks high on gender equality measures and where there are legal guarantees requiring that a woman can return to the same job after taking time to give birth.

This shows that, although family-friendly policies contribute to improving female labor force participation and reducing the gender pay gap , they are only part of the solution. Even when there is generous paid leave and subsidized childcare, as long as mothers disproportionately take additional work at home after having children, inequities in pay are likely to remain.

Ability, personality, and social norms

The discussion so far has emphasized the importance of job characteristics and occupational choice in explaining the gender pay gap. This leads to obvious questions: What determines the systematic gender differences in occupational choice? What makes women seek job flexibility and take a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work?

One argument usually put forward is that, to the extent that biological differences in preferences and abilities underpin gender roles, they are the main factors explaining the gender pay gap. In their review of the evidence, Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn (2017) show that there is limited empirical support for this argument. 11

To be clear, yes, there is evidence supporting the fact that men and women differ in some key attributes that may affect labor market outcomes. For example, standardized tests show that there are statistical gender gaps in maths scores in some countries ; and experiments show that women avoid more salary negotiations , and they often show particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotion potential . However, these observed differences are far from being biologically fixed – 'gendering' begins early in life and the evidence shows that preferences and skills are highly malleable. You can influence tastes, and you can certainly teach people to tolerate risk, to do maths, or to negotiate salaries.

What's more, independently of where they come from, Blau and Kahn show that these empirically observed differences can typically only account for a modest portion of the gender pay gap.

In contrast, the evidence does suggest that social norms and culture, which in turn affect preferences, behavior, and incentives to foster specific skills, are key factors in understanding gender differences in labor force participation and wages. You can read more about this farther below.

Discrimination and bias

Independently of the exact origin of the unequal distribution of gender roles, it is clear that our recent and even current practices show that these roles persist with the help of institutional enforcement. Goldin (1988), for instance, examines past prohibitions against the training and employment of married women in the US. She touches on some well-known restrictions, such as those against the training and employment of women as doctors and lawyers, before focusing on the lesser known but even more impactful 'marriage bars' that arose in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These work prohibitions are important because they applied to teaching and clerical jobs – occupations that would become the most commonly held among married women after 1950. Around the time the US entered World War II, it is estimated that 87% of all school boards would not hire a married woman and 70% would not retain an unmarried woman who married. 12

The map here highlights that to this day, explicit barriers limit the extent to which women are allowed to do the same jobs as men in some countries. 13

However, even after explicit barriers are lifted and legal protections put in place, discrimination and bias can persist in less overt ways. Goldin and Rouse (2000), for example, look at the adoption of "blind" auditions by orchestras and show that by using a screen to conceal the identity of a candidate, impartial hiring practices increased the number of women in orchestras by 25% between 1970 and 1996. 14

Many other studies have found similar evidence of bias in different labor market contexts. Biases also operate in other spheres of life with strong knock-on effects on labor market outcomes. For example, at the end of World War II only 18% of people in the US thought that a wife should work if her husband was able to support her . This obviously circles back to our earlier point about social norms. 15

Strategies for reducing the gender pay gap

In many countries wage inequality between men and women can be reduced by improving the education of women. However, in many countries, gender gaps in education have been closed and we still have large gender inequalities in the workforce. What else can be done?

An obvious alternative is fighting discrimination. But the evidence presented above shows that this is not enough. Public policy and management changes on the firm level matter too: Family-friendly labor-market policies may help. For example, maternity leave coverage can contribute by raising women’s retention over the period of childbirth, which in turn raises women’s wages through the maintenance of work experience and job tenure. 16

Similarly, early education and childcare can increase the labor force participation of women — and reduce gender pay gaps — by alleviating the unpaid care work undertaken by mothers. 17

Additionally, the experience of women's historical advance in specific professions (e.g. pharmacists in the US), suggests that the gender pay gap could also be considerably reduced if firms did not have the incentive to disproportionately reward workers who work long hours, and fixed, non-flexible schedules. 18

Changing these incentives is of course difficult because it requires reorganizing the workplace. But it is likely to have a large impact on gender inequality, particularly in countries where other measures are already in place. 19

Implementing these strategies can have a positive self-reinforcing effect. For example, family-friendly labor-market policies that lead to higher labor-force attachment and salaries for women will raise the returns on women's investment in education – so women in future generations will be more likely to invest in education, which will also help narrow gender gaps in labor market outcomes down the line. 20

Nevertheless, powerful as these strategies may be, they are only part of the solution. Social norms and culture remain at the heart of family choices and the gender distribution of labor. Achieving equality in opportunities requires ensuring that we change the norms and stereotypes that limit the set of choices available both to men and women. It is difficult, but as the next section shows, social norms can be changed, too.

How well do biological differences explain the gender pay gap?

Across the world, women tend to take on more family responsibilities than men. As a result, women tend to be overrepresented in low-paying jobs where they are more likely to have the flexibility required to attend to these additional responsibilities.

These two facts – documented above – are often used to claim that, since men and women tend to be endowed with different tastes and talents, it follows that most of the observed gender differences in wages stem from biological sex differences. But what’s the broader evidence for these claims?

In a nutshell, here's what the research and data shows:

- There is evidence supporting the fact that statistically speaking, men and women tend to differ in some key aspects, including psychological attributes that may affect labor-market outcomes.

- There is no consensus on the exact weight that nurture and nature have in determining these differences, but whatever the exact weight, the evidence does show that these attributes are strongly malleable.

- Regardless of the origin, these differences can only explain a modest part of the gender pay gap.

Some context regarding the gender distribution of labor

Before we get into the discussion of whether biological attributes explain wage differences via gender roles, let's get some perspective on the gender distribution of work.

The following chart shows, by country, the female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care work, including tasks like taking care of children at home, housework, or doing community work. As can be seen, all over the world there is a radical unbalance in the gender distribution of labor – everywhere women take a disproportionate amount of unpaid work.

This is of course closely related to the fact that in most countries there are gender gaps in labor force participation and wages .

“Boys are better at maths”

Differences in biological attributes that determine our ability to develop 'hard skills', such as maths, are often argued to be at the heart of the gender pay gap. 21 Do large gender differences in maths skills really exist? If so, is this because of differences in the attributes we are born with?

Let's look at the data.

Are boys better in the mathematics section of the PISA standardized test ? One could argue that looking at top scores is more relevant here since top scores are more likely to determine gaps in future professional trajectories – for example, gaps in access to 'STEM degrees' at the university level.

The chart shows the share of male and female test-takers scoring at the highest level on the PISA test (that's level 6). As we can see, most countries lie above the diagonal line marking gender parity; so yes, achieving high scores in maths tends to be more common among boys than girls. However, there is huge cross-country variation – the differences between countries are much larger than the differences between the sexes. And in many countries, the gap is effectively inexistent. 22

Similarly, researchers have found that within countries there is also large geographic variation in gender gaps in test scores. So clearly these gaps in mathematical ability do not seem to be fully determined by biological endowments. 23

Indeed, research looking at the PISA cross-country results suggests that improved social conditions for women are related to improved math performance by girls. 24

Not only do statistical gaps in test scores vary substantially across societies – they also vary substantially across time. This suggests that social factors play a large role in explaining differences between the sexes.

In the US, for example, the gender gap in mathematics has narrowed in recent decades. 25 And this narrowing took place as high school curricula of boys and girls became more similar. The following chart shows this: In the US boys in 1957 took far more math and science courses than did girls; but by 1992 there was virtual parity in almost all science and math courses.

More importantly for the question at hand, gender gaps in 'hard skills' are not large enough to explain the gender gaps in earnings. In their review of the evidence, Blau and Kahn (2017) concludes that gaps in test scores in the US are too small to explain much of the gender pay at any point in time. 26

So, taken together, the evidence suggests that statistical gaps in maths test scores are both relatively small and heavily influenced by social and environmental factors.

“It’s about personality”

Biological differences in tastes (e.g. preferences for 'people' over 'things'), psychological attributes (e.g. 'risk aversion'), and soft skills (e.g. the ability to get along with others) are also often argued to be at the heart of the gender pay gap.

There are hundreds of studies trying to establish whether there are gender differences in preferences, personality traits, and 'soft skills'. The quality and general relevance (i.e. the internal and external validity) of these studies is the subject of much discussion, as illustrated in the recent debate that ensued from the Google Memo affair .

A recent article from the 'Heterodox Academy ', which was produced specifically in the context of the Google Memo, provides a fantastic overview of the evidence on this topic and the key points of contention among scholars.

For the purpose of this blog post, let's focus on the review of the evidence presented in Blau and Kahn (2017) – their review is particularly helpful because they focus on gender differences in the context of labor markets.

Blau and Kahn point out that, yes, researchers have found statistical differences between men and women that are important in the context of labor-market outcomes. For example, studies have found statistical gender differences in 'people skills' (i.e. ability to listen, communicate, and relate to others). Similarly, experimental studies have found that women more often avoid salary negotiations , and they often show a particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotability. But are the origins of these differences mainly biological or are they social? And are they strong enough to explain pay gaps?

The available evidence here suggests these factors can only explain a relatively small fraction of the observed differences in wages. 27 And they are anyway far from being purely biological – preferences and skills are highly malleable and 'gendering' begins early in life. 28

Here is a concrete example: Leibbrandt and List (2015) did an experiment in which they assessed how men and women reacted to job advertisements. 29 They found that although men were more likely to negotiate than women when there was no explicit statement that wages were negotiable, the gender difference disappeared and even reversed when it was explicitly stated that wages were negotiable. This suggests that it is not as much about 'talent', as it is about norms and rules.

“A man should earn more than his wife”

The experiment in which researchers found that gender differences in negotiation attitudes disappeared when it was explicitly stated that wages were negotiable, emphasizes the important role that social norms and culture play in labor-market outcomes.

These concepts may seem abstract: What do social norms and culture actually look like in the context of the gender pay gap?

The reproduction of stereotypes through everyday positive enforcement can be seen in a range of aspects: A study analyzing 124 prime-time television programs in the US found that female characters continue to inhabit interpersonal roles with romance, family, and friends, while male characters enact work-related roles. 30 In the realm of children’s books, a study of 5,618 books found that compared to females, males are represented nearly twice as often in titles and 1.6 times as often as central characters. 31 Qualitative research shows that even in the home, parents are often enforcers of gender norms – especially when it comes to fathers endorsing masculinity in male children. 32

Of particular relevance in the context of labor markets, social norms also often take the form of specific behavioral prescriptions such as "a man should earn more than his wife".

The following chart depicts the distribution of the share of the household income earned by the wife, across married couples in the US.

Consistent with the idea that "a man should earn more than his wife", the data shows a sharp drop at 0.5, the point where the wife starts to earn more than the husband.

Distribution of income share earned by the wife across married couples in the US – Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan (2015) 33

This is the result of two factors. First, it is about the matching of men and women before they marry – 'matches' in which the woman has higher earning potential are less common. Second, it is a result of choices after marriage – the researchers show that married women with higher earning potential than their husbands often stay out of the labor force, or take 'below-potential' jobs. 34

The authors of the study from which this chart is taken explored the data in more detail and found that in couples where the wife earns more than the husband, the wife spends more time on household chores, so the gender gap in unpaid care work is even larger; and these couples are also less satisfied with their marriage and are more likely to divorce than couples where the wife earns less than the husband.

The empirical exploration in this study highlights the remarkable power that gender norms and identity have on labor-market outcomes.

Why do gender norms and identity matter?

Does it actually matter if social norms and culture are important determinants of gender roles and labor-market outcomes? Are social norms in our contemporary societies really less fixed than biological traits?

The available research suggests that the answers to these questions are yes and yes. There is evidence that social norms can be actively and rapidly changed.

Here is a concrete example: Jensen and Oster (2009) find that the introduction of cable television in India led to a significant decrease in the reported acceptability of domestic violence towards women and son preference, as well as increases in women’s autonomy and decreases in fertility. 35

Of course, TV is a small aspect of all the big things that matter for social norms. But this study is important for the discussion because it is hard to study how social norms can be changed. TV introduction is a rare opportunity to see how a group that is exposed to a driver of social change actually changes.

As Jensen and Oster point out, most popular cable TV shows in India feature urban settings where lifestyles differ radically from those in rural areas. For example, many female characters on popular soap operas have more education, marry later, and have smaller families than most women in rural areas. And, similarly, many female characters in these tv shows are featured working outside the home as professionals, running businesses, or are shown in other positions of authority.

The bar chart below shows how cable access changed attitudes toward the self-reported preference for their child to be a son. As the authors note, "reported desire for the next child to be a son is relatively unchanged in areas with no change in cable status, but it decreases sharply between 2001 and 2002 for villages that get cable in 2002, and between 2002 and 2003 (but notably not between 2001 and 2002) for those that get cable in 2003. For both measures of attitudes, the changes are large and striking, and correspond closely to the timing of introduction of cable."

To conclude: The evidence suggests that biological differences are not a key driver of gender inequality in labor-market outcomes; while social norms and culture – which in turn affect preferences, behavior, and incentives to foster specific skills – are very important.

This matters for policy because social norms are not fixed – they can be influenced in a number of ways, including through intergenerational learning processes, exposure to alternative norms, and activism such as that which propelled the women's movement. 36

How are women represented across jobs?

Representation of women at the top of the income distribution.

Despite having fallen in recent decades, there remains a substantial pay gap between the average wages of men and women .

But what does gender inequality look like if we focus on the very top of the income distribution? Do we find any evidence of the so-called 'glass ceiling' preventing women from reaching the top? How did this change over time?

Answers to these questions are found in the work of Atkinson, Casarico and Voitchovsky (2018). Using tax records, they investigated the incomes of women and men separately across nine high-income countries. As such, they were restricted to those countries in which taxes are collected on an individual basis, rather than as couples. 37

In addition to wages they also take into account income from investments and self-employment.

Whilst investment income tends to make up a larger share of the total income of rich individuals in general, the authors found this to be particularly marked in the case of women in top-income groups.

The two charts present the key figures from the study.

One chart shows the proportion of women out of all individuals falling into the top 10%, 1%, and 0.1% of the income distribution. The open circle represents the share of women in the top income brackets back in 2000; the closed circle shows the latest data, which is from 2013.

The other chart shows the data over time for individual countries. You can explore data for other countries using the 'Change country' button on the chart.

The two charts allow us to answer the initial questions:

- Women are greatly under-represented in top income groups – they make up much less than 50% across each of the nine countries. Within the top 1% women account for around 20% and there is surprisingly little variation across countries.

- The proportion of women is lower the higher you look up the income distribution. In the top 10% up to every third income-earner is a woman; in the top 0.1% only every fifth or tenth person is a woman.

- The trend is the same in all countries of this study: Women are now better represented in all top-income groups than they were in 2000.

- But improvements have generally been more limited at the very top. With the exception of Australia, we see a much smaller increase in the share of women amongst the top 0.1% than amongst the top 10%.

Overall, despite recent inroads, we continue to see remarkably few women making it to the top of the income distribution today.

Representation of women in management positions

The chart here plots the proportion of women in senior and middle management positions around the world. It shows that women all over the world are underrepresented in high-profile jobs, which tend to be better paid.

The next chart provides an alternative perspective on the same issue. Here we show the share of firms that have a woman as manager. We highlight world regions by default, but you can remove them and add specific countries.

As we can see, all over the world firms tend to be managed by men. And, globally, only about 18% of firms have a female manager.

Firms with female managers tend to be different to firms with male managers. For example, firms with female managers tend to also be firms with more female workers .

Representation of women in low-paying jobs

Above we show that women all over the world are underrepresented in high-profile jobs, which tend to be better paid. As it turns out, in many countries women are at the same time overrepresented in low-paying jobs.

This is shown in the chart here, where 'low-pay' refers to workers earning less than two-thirds of the median (i.e. the middle) of the earnings distribution.

A share above 50% implies that women are 'overrepresented', in the sense that among those with low wages, there are more women than men.

The fact that women in rich countries are overrepresented in the bottom of the income distribution goes together with the fact that working women in these countries are overrepresented in low-paying occupations. The chart shows this for the US.

How much control do women have over household resources?

Women often have no control over their personal earned income.

The next chart plots cross-country estimates of the share of women who are not involved in decisions about their own income. The line shows national averages, while the dots show averages for rich and poor households (i.e. averages for women in households within the top and bottom quintiles of the corresponding national income distribution).

As we can see, in many countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, a large fraction of women are not involved in household decisions about spending their personal earned income. And this pattern is stronger among low-income households within low-income countries.

Percentage of women not involved in decisions about their own income – World Development Report (2012) 39

In many countries, women have limited influence over important household decisions

Above we focus on whether women get to choose how their own personal income is spent. Now we look at women's influence over total household income.

In this chart, we plot the share of currently married women who report having a say in major household purchase decisions, against national GDP per capita.

We see that in many countries, notably in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, an important number of women have limited influence over major spending decisions.

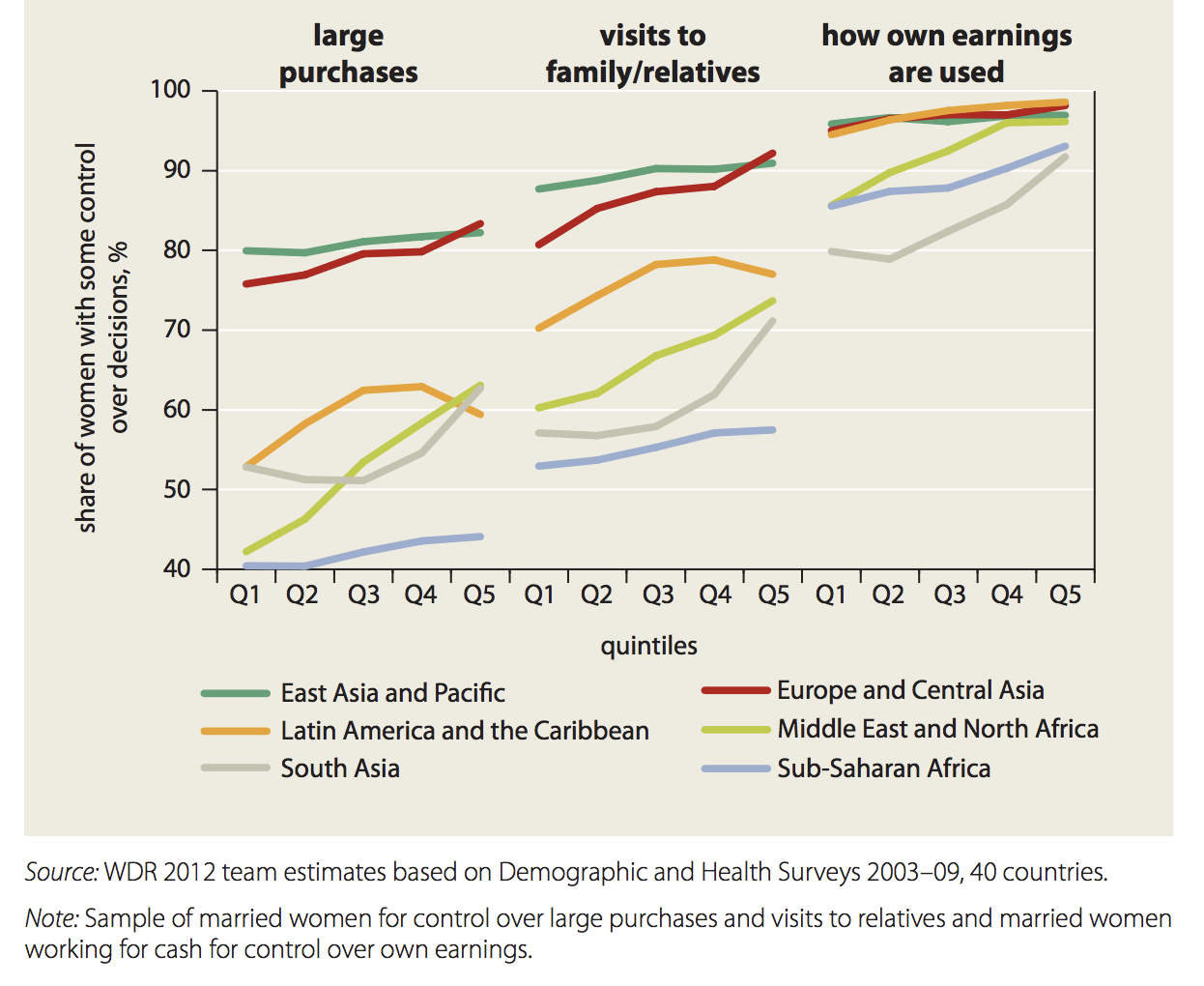

The chart above shows that women’s control over household spending tends to be greater in richer countries. In the next chart, we show that this correlation also holds within countries: Women’s control is greater in wealthier households. Household wealth is shown by the quintile in the wealth distribution on the x-axis – the poorest households are in the lowest quintiles (Q1) on the left.

There are many factors at play here, and it's important to bear in mind that this correlation partly captures the fact that richer households enjoy greater discretionary income beyond levels required to cover basic expenditure, while at the same time, in richer households women often have greater agency via access to broader networks as well as higher personal assets and incomes.

Land ownership is more often in the hands of men

Economic inequalities between men and women manifest themselves not only in terms of wages earned but also in terms of assets owned. For example, as the chart shows, in nearly all low and middle-income countries with data, men are more likely to own land than women.

Women's lack of control over important household assets, such as land, can be a critical problem in case of divorce or the husband’s death.

Closely related to the issue of land ownership is the fact that in several countries women do not have the same rights to property as men. These countries are highlighted in the map. 40

Gender-equal inheritance systems have been adopted in most, but not all countries

Inheritance is one of the main mechanisms for the accumulation of assets. In the map, we provide an overview of the countries that do and do not have gender-equal inheritance systems.

If you move the slider to 1920, you will see that while gender-equal inheritance systems were very rare in the early 20th century, today they are much more common. And still, despite the progress achieved, in many countries, notably in North Africa and the Middle East, women and girls still have fewer inheritance rights than men and boys.

Gender differences in access to productive inputs are often large

Above we show that there are large gender gaps in land ownership across low-income countries. Here we show that there are also large gaps in terms of access to borrowed capital.

The chart shows the percentage of men and women who report borrowing any money in the past 12 months to start, operate, or expand a farm or business.

As we can see, almost everywhere, including in many rich countries, women are less likely to obtain borrowed capital for productive purposes.

This can have large knock-on effects: in agriculture and entrepreneurship, gender differences in access to productive inputs, including land and credit, can lead to gaps in earnings via lower productivity.

Indeed, studies have found that, when statistical gender differences in agricultural productivity exist, they often disappear when access to and use of productive inputs are taken into account. 41

Interactive Charts on Economic Inequality by Gender

Acknowledgements.

We thank Sandra Tzvetkova and Diana Beltekian for their great research assistance.

There are some exceptions to this definition. In particular, sometimes self-employed workers, or part-time workers are excluded.

This measure can also be negative. This means that, on an hourly basis, men earn on average less than women. It is the case for some countries, such as Malaysia.

Olivetti, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2008). Unequal pay or unequal employment? A cross-country analysis of gender gaps. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(4), 621-654.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. " The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. " Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 789-865.

For each specification, Blau and Kahn (2017) perform regression analyses on data from the PSID (the Michigan Panel Study of Income Dynamics), which includes information on labor-market experience and considers men and women ages 25-64 who were full-time, non-farm, wage and salary workers.

In 2010, unionization and education show negative values; this reflects the fact that women have surpassed men in educational attainment, and unionization in the US has been in general decline with a greater effect on men.

The full source is: World Development Report (2012) Gender Equality and Development , World Bank.

Goldin, C. (2014). A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. The American Economic Review, 104(4), 1091-1119.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2016). A most egalitarian profession: pharmacy and the evolution of a family-friendly occupation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(3), 705-746.

Lundborg, P., Plug, E., & Rasmussen, A. W. (2017). Can Women Have Children and a Career? IV Evidence from IVF Treatments. American Economic Review, 107(6), 1611-1637.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. " The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. " Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 789-865

Goldin, C. (1988). Marriage bars: Discrimination against married women workers, 1920's to 1950's .

The data in this map, which comes from the World Bank's World Development Indicators, provides a measure of whether there are any specific jobs that women are not allowed to perform. So, for example, a country might be coded as "No" if women are only allowed to work in certain jobs within the mining industry, such as health care professionals within mines, but not as miners.

Goldin, C., & Rouse, C. (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of" blind" auditions on female musicians. American Economic Review , 90(4), 715-741.

Blau and Kahn (2017) provide a whole list of experimental studies that have found labor-market discrimination. Another early example is from Neumark et al. (1996), who look at discrimination in restaurants. In this case, male and female pseudo-job-seekers were given similar CVs to apply for jobs waiting on tables at the same set of restaurants in Philadelphia. The results showed discrimination against women in high-priced restaurants.

The full reference of this study is Neumark, D., Bank, R. J., & Van Nort, K. D. (1996). Sex discrimination in restaurant hiring: An audit study. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(3), 915-941.

Waldfogel, J. (1998). Understanding the "family gap" in pay for women with children. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(1), 137-156.

Olivetti, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2017). The economic consequences of family policies: lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 205-230.

As we show above, in several nations, such as Sweden and Denmark, a “motherhood penalty” in earnings exists, even though these nations have generous family policies, including paid family leave and subsidized child care.

For a discussion of this mechanism, see page 814, Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 789-865.

Hard skills are abilities that can be defined and measured, such as writing, reading, or doing maths. By contrast, soft skills are less tangible and harder to measure and quantify.

Also importantly: If we focus on gender differences for average , rather than top students, we find that there is not even a clear tendency in favor of boys. ( This interactive chart compares PISA average math scores for boys and girls ).

For more on this see Pope, D. G., & Sydnor, J. R. (2010). Geographic variation in the gender differences in test scores. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(2), 95-108.

Guiso, L., Monte, F., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2008). Culture, gender, and math. SCIENCE-NEW YORK THEN WASHINGTON-, 320(5880), 1164.

A number of papers have documented the narrowing of gender gaps in test scores. See, for example, Hyde, J. S., Lindberg, S. M., Linn, M. C., Ellis, A. B., & Williams, C. C. (2008). Gender similarities characterize math performance . Science, 321(5888), 494-495.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 789-865.

Blau and Kahn write: "While findings such as those in table 7 ['Selected Studies Assessing the Role of Psychological Traits in Accounting for the Gender Pay Gap'] are informative in elucidating some of the possible omitted factors that lie behind gender differences in wages as well as the unexplained gap in traditional wage regressions, in general, the results suggest that these factors do not account for a large portion of either the raw or unexplained gender gap."

For a discussion of 'gendering' see West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125-151.

Leibbrandt, A., & List, J. A. (2014). Do women avoid salary negotiations? Evidence from a large-scale natural field experiment. Management Science, 61(9), 2016-2024.

Lauzen, M. M., Dozier, D. M., & Horan, N. (2008). Constructing gender stereotypes through social roles in prime-time television. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(2), 200-214.

McCabe, J., Fairchild, E., Grauerholz, L., Pescosolido, B. A., & Tope, D. (2011). Gender in twentieth-century children’s books: Patterns of disparity in titles and central characters. Gender & Society, 25(2), 197-226.

Kane, E. W. (2006). “No way my boys are going to be like that!” Parents’ responses to children’s gender nonconformity. Gender & Society, 20(2), 149-176.

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571-614.

More precisely, the authors find that in couples where the wife’s potential income is likely to exceed her husband’s (based on the income that would be predicted for her observed characteristics), the wife is less likely to be in the labor force, and if she does work, her income is lower than predicted.

Jensen, R., & Oster, E. (2009). The power of TV: Cable television and women's status in India . In The Quarterly Journal of Economics , 124(3), 1057-1094.

Regarding intergenerational transmission of gender roles, see Fernández, R. (2013). Cultural change as learning: The evolution of female labor force participation over a century. The American Economic Review, 103(1), 472-500.

For a discussion regarding social activism and its link to the determinants of female labor supply, see for example this study by Heer and Grossbard-Shechtman (1981).

Atkinson, A.B., Casarico, A. & Voitchovsky, S. Top incomes and the gender divide . J Econ Inequal (2018) 16: 225.

The authors produced results for 8 countries, and included earlier results for Sweden from Boschini, A., Gunnarsson, K., Roine, J.: Women in Top Incomes: Evidence from Sweden 1974-2013, IZA Discussion paper 10979, August (2017).

World Bank. (2011). World development report 2012: gender equality and development . World Bank Publications.

The map from The World Development Report (2012) provides a more fine-grained overview of different property regimes operating in different countries.

For more discussion of the evidence see page 20 in World Bank (2011) World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development. World Bank Publications.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Report | Wages

What is the gender pay gap and is it real? : The complete guide to how women are paid less than men and why it can’t be explained away

Report • By Elise Gould , Jessica Schieder , and Kathleen Geier • October 20, 2016

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

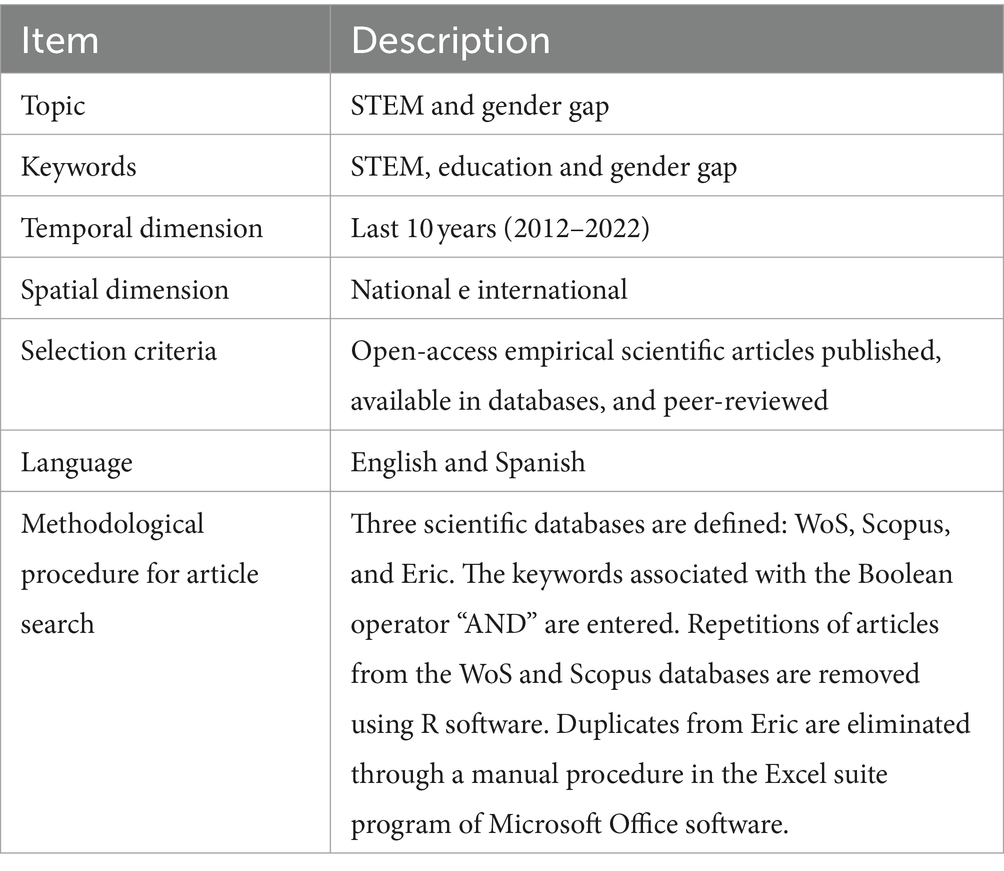

Working women are paid less than working men. A large body of research accounts for, diagnoses, and investigates this “gender pay gap.” But this literature often becomes unwieldy for lay readers, and because pay gaps are political topics, ideological agendas often seep quickly into discussions.

This primer examines the evidence surrounding the gender pay gap, both in the literature and through our own data analyses. We will begin by explaining the different ways the gap is measured, and then go deeper into the data using hourly wages for our analyses, 1 culling from extensive national and regional surveys of wages, educational attainment, and occupational employment.

Why different measures don’t mean the data are unreliable

A number of figures are commonly used to describe the gender wage gap. One often-cited statistic comes from the Census Bureau, which looks at annual pay of full-time workers. By that measure, women are paid 80 cents for every dollar men are paid. Another measure looks at hourly pay and does not exclude part-time workers. It finds that, relative to men, typical women are paid 83 cents on the dollar. 2 Other, less-cited measures show different gaps because they examine the gap at different parts of the wage distribution, or for different demographic subgroups, or are adjusted for factors such as education level and occupation.

The presence of alternative ways to measure the gap can create a misconception that data on the gender wage gap are unreliable. However, the data on the gender wage gap are remarkably clear and (unfortunately) consistent about the scale of the gap. In simple terms, no matter how you measure it, there is a gap. And, different gaps answer different questions. By discussing the data and the rationale behind these seemingly contradictory measures of the wage gap, we hope to improve the discourse around the gender wage gap.

Why adjusted measures can’t gauge the full effects of discrimination

The most common analytical mistake people make when discussing the gender wage gap is to assume that as long as it is measured “correctly,” it will tell us precisely how much gender-based discrimination affects what women are paid.

Specifically, some people note that the commonly cited measures of the gender wage gap do not control for workers’ demographic characteristics (such measures are often labeled unadjusted). They speculate that the “unadjusted” gender wage gap could simply be reflecting other influences, such as levels of education, labor market experiences, and occupations. And because gender wage gaps that are “adjusted” for workers’ characteristics (through multivariate regression) are often smaller than unadjusted measures, people commonly infer that gender discrimination is a smaller problem in the American economy than thought.

However, the adjusted gender wage gap really only narrows the analysis to the potential role of gender discrimination along one dimension : to differential pay for equivalent work. But this simple adjustment misses all of the potential differences in opportunities for men and women that affect and constrain the choices they make before they ever bargain with an employer over a wage. While multivariate regression can be used to distill the role of discrimination in the narrowest sense, it cannot capture how discrimination affects differences in opportunity.

In short, one should have a very precise question that he or she hopes to answer using the data on the wage differences between men and women workers. We hope to provide this careful thinking in the questions we address in this primer.

A summary of some key questions and answers in this primer

Given that gender wage gaps are strikingly persistent in economic data, it is natural to then ask, “What causes these gaps?” And, further, “Do women’s own choices and labor force characteristics drive the gender wage gap, or are women’s opportunities for higher pay constricted relative to men?” Although this paper will largely focus on empirical data to answer questions about the size and scope of the gaps for different groups of women, we will use the data to shed light on some of these “why” questions.

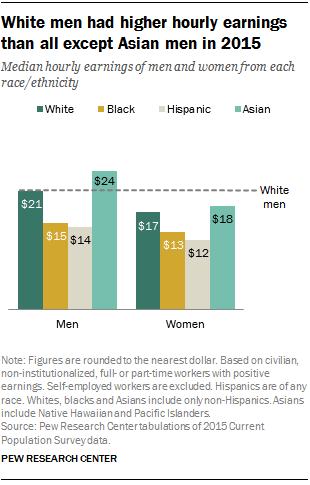

- How much do women make relative to men? A typical, or median, woman working full time is paid 80 cents for every dollar a typical man working full time is paid. When evaluated by wages per hour, a typical woman is paid 83 cents for every dollar a man is paid. Both of these measures are correct, but examining women’s earnings per hour is our preferred way of looking at the wage gap. 3

- Is the wage gap the same whether you are a front-line worker or a high-level executive? There is much greater parity at the lower end of the wage distribution, likely because minimum wages and other labor market policies create a wage floor. At the 10th percentile, women are paid 92 cents on the male dollar, whereas women at the 95th percentile are paid 74 cents relative to the dollar of their male counterparts’ hourly wages.

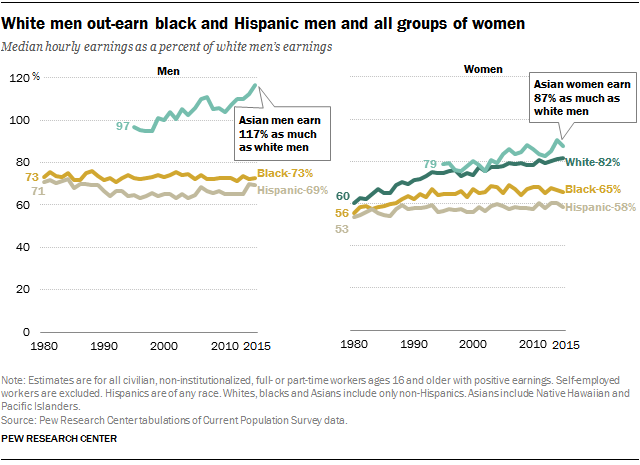

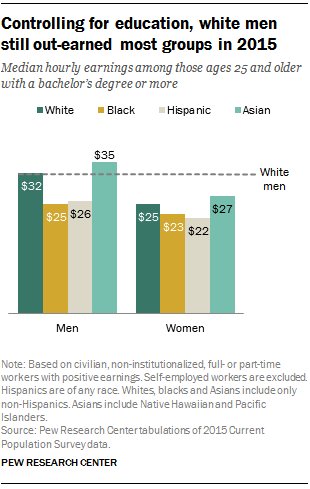

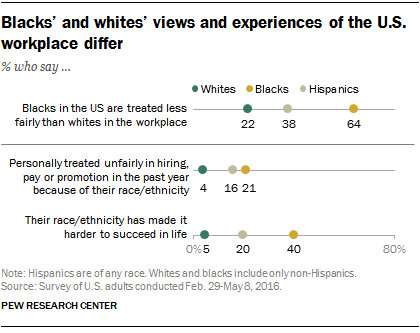

- Does a woman’s race or ethnicity affect how much she makes relative to a man? Asian and white women at the median actually experience the biggest gaps relative to Asian and white men, respectively. But that is due, in part, to the fact that Asian and white men make much more than black or Hispanic men. Relative to white non-Hispanic men, black and Hispanic women workers are paid only 65 cents and 58 cents on the dollar, respectively, compared with 81 cents for white, non-Hispanic women workers and 90 cents for Asian women.

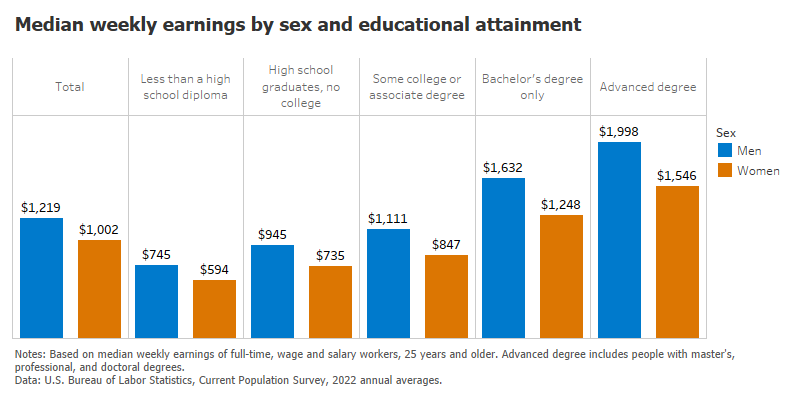

- Can women close the wage gap by getting more education? It appears not. Women are paid less than similarly educated men at every level of education. And the wage gap tends to rise with education level. This, again, in part likely reflects labor market policies that foster more-equal outcomes for workers in the lower tier of the wage distribution. It also may be affected by certain challenges that disproportionately affect women’s ability to secure jobs at the top of the wage distribution, such as earnings penalties for time out of the workforce, excessive work hours, domestic gender roles, and pay and promotion discrimination.

- Men constitute greater shares of certain types of jobs, or occupations, and women greater shares in others. Some say that these differences in how men and women are distributed across occupations explain much of the gender wage gap. In truth, it explains some of the gap, but not nearly as much as is assumed. And even when we reduce the size of the measured gap by controlling for occupational distributions, that does not mean that the remaining gap provides a complete view of the role of discrimination on women’s wages. Gender discrimination doesn’t happen only in the pay-setting practices of employers making wage offers to nearly identical workers of different genders. It can happen at every stage of a woman’s life, from steering her away from science and technology education to shouldering her with home responsibilities that impede her capacity to work the long hours of demanding professions.

- Women who work in male-dominated occupations are paid significantly less than similarly educated males in those occupations. So even recommending that women choose better-paying occupations does not solve the problem.

- Are women in unions, relative to their male peers, better or worse off? Working women in unions are paid 89 cents for every dollar paid to unionized working men; nonunionized working women are paid 82 cents for every dollar paid to nonunionized working men.

- After giving birth, women’s pay lags behind pay of similarly educated and experienced men and of women without children. There is no corresponding “fatherhood penalty” for men. 4

- Outside the labor market, mothers are also charged a time penalty. For example, among married full-time working parents of children under the age of 18, women still spend 50 percent more time than men engaging in care activities within the home. Among child-rearing couples that include a woman either working part time or staying at home to parent, the burden of caring for family members is even more disproportionately borne by women. This higher share of domestic and care work performed by women suggests that cultural norms and expectations strongly condition (and often restrict) the labor market opportunities of women. Indeed, it likely plays a role in the lower labor force participation of mothers relative to men or women without children.

- The higher share of domestic and care work performed by women is also a disadvantage for women in high-prestige, high-wage jobs in which employers demand very long hours as a condition of work.

- Does a shrinking wage gap unequivocally indicate a good thing—that women are catching up to men? Unfortunately no. Because the gender pay gap has both a numerator (women’s wages) and a denominator (men’s wages), one cannot make firm normative judgments about whether a given fall (or rise) in the gender pay gap is welcome news. For example, about 30 percent of the reduction of the gender wage gap between the median male and female worker since 1979 is due to the decline in men’s wages during this period.

- If we counted benefits, would women be doing less bad relative to men? The gender pay gap in cash wages would not disappear by factoring in other employee benefits because women are less likely than men to have employer-provided health insurance and have fewer retirement resources than men.

The gender pay gap is a fraught topic. Discussions about it would benefit greatly from a thorough review of the empirical evidence. The data can answer only precise questions, but the answers can help us work toward the broader questions. This paper aims to provide this precision in search of broader answers. Readers can access the data we analyze and report in this paper in the EPI State of Working America Data Library . By making the data publicly available and usable, we hope to advance constructive discussions of the gender pay gap.

The gender wage gap 101: The basics

The gender wage gap is a measure of pay disparity between men and women. While it can be measured different ways, the data are clear: women are still paid much less relative to men (about 83 cents per dollar, by our measure), and progress on closing the gap has stalled.

What is the gender wage gap?

The wage gap means women are paid:.

82.7 percent of men’s wages. This translates to 83 cents per dollar. The “typical” (median) woman is paid 83 cents per every dollar the typical man is paid.

In dollar terms this means women bring home:

$3.27 less per hour than men. The median hourly wage is $15.67 for women and $18.94 for men.

The gender wage gap is a measure of what women are paid relative to men. It is commonly calculated by dividing women’s wages by men’s wages, and this ratio is often expressed as a percent, or in dollar terms. This tells us how much a woman is paid for each dollar paid to a man. This gender pay ratio is often measured for year-round, full-time workers and compares the annual wages (of hourly wage and salaried workers) of the median (“typical”) man with that of the median (“typical”) woman; measured this way, the current gender pay ratio is 0.796, or, expressed as a percent, it is 79.6 percent (U.S. Census Bureau 2016). In other words, for every dollar a man makes, a woman makes about 80 cents.

The difference in earnings between men and women is also sometimes described in terms of how much less women make than men. To calculate this gap from the ratio as defined above, simply subtract the ratio from 1. So, if the gender pay ratio is about 80 percent (or 80 cents on the dollar), this means that women are paid 20 percent less (or 20 cents less per dollar) than men. A larger difference between men’s and women’s earnings translates into a lower ratio but a larger gap in their earnings.

We keep with this convention of using median wages of wage and salary workers rather than average wages of wage and salary workers because averages can be skewed by a handful of people making much more or much less than the rest of workers in a sample. However, we examine median wages on an hourly basis and include all workers reporting a positive number of work hours. This hourly measure constitutes a limited “adjustment” in research methodology in that it accounts for the fact that men work more hours on average during the year, and that more women work part time. 5 This limited adjustment allows us to compare women’s and men’s wages without assuming that women, who still shoulder a disproportionate amount of responsibilities at home, would be able or willing to work as many hours as their male counterparts.

Computed this way using data from the federal government’s Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group, or CPS ORG in shorthand, the typical woman is paid 82.7 percent of what the typical man is paid (CPS ORG 2015). Or in common terms, women are paid 83 cents on the male dollar.

Notwithstanding our limited adjustment, this is basically the “raw” or “unadjusted” gap that we explore throughout this report when we consider the ways a large basket of factors interact and create the wage gap women experience when they cash their paychecks.

Would adjusting the raw gender wage gap to include factors such as education help explain the gap? Maybe it is not as big of a problem as it seems?

Adjustments can help round out our understanding but unfortunately, as we explain here, they don’t explain away the gap. It is important to understand why.

The gender wage gap described above and referred to in this primer has the virtue of being clear and simple. It provides a good overview of what is going on with typical women’s earnings relative to men’s. But it does not tell us what the wage gap is between men and women doing similar work, and whether the size of the gap derives in part from differences in education levels, experience levels, and other characteristics of working men and women. To round out our understanding of the disparity between men’s and women’s pay, we also consider “adjusted” measures of the gender wage gap—with the caveat that the adjusted measures may understate the wage disparities.

Adjusted wage gap estimates control for characteristics such as race and ethnicity, level of education, potential work experience, and geographic division. These estimate are made using average wages rather than median because it requires standard regression techniques. Again, using the Current Population Survey data from the CPS Outgoing Rotation Group, but making these adjustments, we find that the wage gap grows, with women on average paid 21.7 percent less than men. 6 The unadjusted penalty for the average woman is 17.9 percent. 7 The measured penalty actually increases when accounting for these influences because women workers, on average, have higher levels of education than men. 8

Models that control for a much larger set of variables—such as occupation, industry, or work hours—are sometimes used to isolate the role of discrimination in setting wages for specific jobs and workers. The notion is that if we can control for these factors, the wage gap will shrink, and what is left can be attributed to discrimination. Think of a man and woman with identical education and years of experience working side-by-side in cubicles but who are paid different wages because of discriminatory pay-setting practices. We also run a model with more of these controls, and find that the wage gap shrinks slightly from the unadjusted measure, from 17.9 percent to 13.5 percent. 9 Researchers have used more extensive datasets to examine these differences. For instance, Blau and Kahn (2016) find an unadjusted penalty of 20.7 percent, a partially adjusted penalty of 17.9 percent, and a fully adjusted penalty of 8.4 percent. 10

But switching to a fully adjusted model of the gender wage gap actually can radically understate the effect of gender discrimination on women’s earnings. This is because gender discrimination doesn’t happen only in the pay-setting practices of employers making wage offers to nearly identical workers of different genders. Instead, it can potentially happen at every stage of a woman’s life, from girlhood to moving through the labor market. By the time she completes her education and embarks on her career, a woman’s occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations of parents and other influential adults, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work/family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society (Gould and Schieder 2016). So it would not be accurate to assume that discrimination explains only the gender wage gap that remains after adjusting for education, occupational choice, and all these other factors. Put another way, we cannot look at our adjusted model and say that discrimination explains at most 13.5 percent of the gender wage gap. Why? Because, for example, by controlling for occupation, this adjusted wage gap no longer includes the discrimination that can influence a woman’s occupational choice.

How much does the gender pay gap cost women over a lifetime?

The average woman worker loses more than $530,000 over the course of her lifetime because of the gender wage gap, and the average college-educated woman loses even more—nearly $800,000 (IWPR 2016). It’s worth noting that each woman’s losses will vary significantly based on a variety of factors—including the health of the economy at various points in her life, her education, and duration of periods out of the labor force—but this estimate demonstrates the significance of the cumulative impact. And, as explained later, the gap may play a role in the retirement insecurity of older American women.

Yes, but isn’t the gender pay gap smaller than it used to be?

Over the past three and a half decades, substantial progress has been made to narrow the pay gap. Women’s wages are now significantly closer to men’s, but in recent years, that progress has stalled.

From 1979 to the early 1990s, the ratio of women’s median hourly earnings to men’s hourly median earnings grew partly because women made disproportionate gains in education and labor force participation. After that, convergence slowed, and over the past two decades, it has stalled. According to the most recent data, as of 2015, women’s hourly wages are 82.7 percent of men’s hourly wages at the median ( Figure A ), with the median woman paid an hourly wage of $15.67, compared with $18.94 for men ( Figure B ).

Progress in closing the gender pay gap has largely stalled : Women's hourly wages as a share of men's at the median, 1979–2015

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey microdata. For more information on the data sample see EPI's State of Working America Data Library .

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Women earn less than men at every wage level : Hourly wages by gender and wage percentile, 2015

Source : EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata. For more information on the data sample see EPI's State of Working America Data Library .

It’s not entirely clear why women have stopped gaining on men. But as discussed later in the section on the “motherhood penalty,” the tendency for women with children to receive systematically lower pay has stubbornly persisted, suggesting that the gender pay gap is not going away anytime soon. Economist Claudia Goldin’s research supports this conclusion. According to Goldin, current trends indicate that women’s wages will still be pulled down over the course of their working lifetimes, even after controlling for education and work time (Goldin 2014).

How much of the narrowing of the gender pay gap is due to women’s earnings rising, and how much is due to men’s earnings falling?

Since 1979, median men’s wages have stagnated, falling 6.7 percent in real terms from $20.30 per hour to $18.94 ( Figure C ). At the same time, women’s real median hourly wages have increased. In 1979, they were equal to roughly 62.4 percent of men’s real median hourly wages. By 2015, they were equal to 82.7 percent of men’s real wages at the median—a substantial reduction in the wage gap. Unfortunately, this means that about 30 percent of the reduction was due to the decline in men’s wages. The stagnation and decline of median men’s wages has played a significant role in the decline in the unadjusted gender wage gap. Women’s wages increased as more women had increased their participation in the labor force, increased their educational attainment, and entered higher-paying occupations. (Davis and Gould 2015). At the same time, for most workers, wages no longer increased with increases in economy-wide productivity. Had workers’ wages continued to keep pace with productivity, both men and women would be earning much more today.

The gender wage gap persists, but has narrowed since 1979 : Median hourly wages, by gender, 1979–2015

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata. For more information on the data sample see EPI's State of Working America Data Library .

Does a woman’s race, age, or pay level affect the gender gap she experiences?

Belonging to a certain race or age group does not immunize women from experiencing the gender wage gap. It affects women across the board, though higher-earning women and middle-age women are at a greater disadvantage relative to their male counterparts. And relative to white male wages, black and Hispanic women are the most disadvantaged.

Is the gender wage gap a problem for low- or high-earning women?

The gender wage gap is a problem for women at every wage level. At each and every point in the wage distribution, men significantly out-earn women, although by different amounts, to be sure (Figures B and C).

In 2015, the gap between men’s and women’s hourly wages was smallest among the lowest-earning workers, with 10th percentile women earning 92.0 percent of men’s wages. The minimum wage is partially responsible for this greater equality among the lowest earners. It sets a wage floor that applies to everyone, which means that people near the bottom of the distribution are likely to make more equal wages, even though those wages are very low ( Figure D ).

The gender wage gap is still widest among top earners : Women's hourly wages as a share of men's at various wage percentiles, 1979 and 2015

Notes: The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation group microdata

At the median, women’s hourly wages are equal to 82.7 percent of men’s wages.