Dissertations and research projects

- Book a session

- Planning your research

- Qualitative research

- Quantitative research

Introductions

Literature review, methodology, conclusions, working with your supervisor.

- e-learning and books

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

- Review this resource

What is an abstract?

The abstract is a brief summary of your dissertation to help a new reader understand the purpose and content of the document, in much the same way as you would read the abstract of a journal article to help decide whether it was relevant to your work. The function of the abstract is to describe and summarise the contents of the dissertation, rather than making critical or evaluative statements about the project.

When should I write the abstract?

The abstract should be the last section you write before submitting your final dissertation or extended project report, as the content will only be decided once the main document is complete.

What should I include?

One of the best ways to find the right ‘voice’ for the abstract is to look at other examples, either from dissertations in your field or study, or from journal articles. Look out for examples that you feel communicate complex ideas in a simple and accessible way. Your abstract should be clear and understandable to a non-specialist, so avoid specialist vocabulary as far as possible, and use simple sentence structures over longer more complex constructions. You can find a list of phrases for abstract writing here .

Most abstracts are written in the present tense, but this may differ in some disciplines, so find examples to inform your decision on how to write. Avoid the future tense - ‘this dissertation will consider’ - as the research has already been completed by the time someone is reading the abstract! You can explore some key phrases to use in abstract writing here.

Examples of dissertation abstracts Dissertation abstracts, University of Leeds Overview of what to include in your abstract, University of Wisconsin - Madison Abstract structures from different disciplines, The Writing Center For examples from Sheffield Hallam University, use the 'Advanced Search' function in Library Search to access ‘Dissertations/Theses’.

What should the introduction include?

Your introduction should cover the following points:.

- Provide context and set the scene for your research project using literature where necessary.

- Explain the rationale and value of the project.

- Provide definitions and address general limitations in the literature that have influenced the topic or scope of your project.

- Present your research aims and objectives, which may also be phrased as the research ‘problem’ or questions.

Although it is important to draft your research aims and objectives early in the research process, the introduction will be one of the last sections you write. When deciding on how much context and which definitions to include in this section, remember to look back at your literature review to avoid any repetition. It may be that you can repurpose some of the early paragraphs in the literature review for the introduction.

What is the ‘research aim’?

The research aim is a mission statement, that states the main ambition of your project. in other words, what does your research project hope to achieve you may also express this as the ‘big questions’ that drives your project, or as the research problem that your dissertation will aim to address or solve..

You only need one research aim, and this is likely to change as your dissertation develops through the literature review. Keep returning to your research aim and your aspirations for the project regularly to help shape this statement.

What are the research objectives? How are they different from research questions?

Research objectives and questions are the same thing – the only difference is how they are written! The objectives are the specific tasks that you will need to complete – the stepping stones – that will enable you to achieve your overall research aim.

You will usually have 3-5 research objectives, and their order will hep the reader to understand how you will progress through your research project from start to finish. If you can achieve each objective, or answer each research question, you should meet your research aim! It is therefore important to be specific in your choice of language: verbs, such as ‘to investigate’, ‘to explore’, ‘to assess’ etc. will help your research appear “do-able” (Farrell, 2011).

Here’s an example of three research objectives, also phrased as research questions (this depends entirely on your preference):

For more ideas on how to write research objectives, take at look at this list of common academic verbs for creating specific, achievable research tasks and questions.

We have an online study guide dedicated to planning and structuring your literature review.

What is the purpose of the methodology section?

The methodology outlines the procedure and process of your data collection. You should therefore provide enough detail so that a reader could replicate or adapt your methodology in their own research.

While the literature review focuses on the views and arguments of other authors, the methodology puts the spotlight on your project. Two of the key questions you should aim to answer in this section are:

- Why did you select the methods you used?

- How do these methods answer your research question(s)?

The methodology chapter should also justify and explain your choice of methodology and methods. At every point where you faced a decision, ask: Why did choose this approach? Why not something else? Why was this theory/method/tool the most relevant or suitable for my project? How did this decision contribute to answering my research questions?

Although most students write their methodology before carrying out their data collection, the methodology section should be written in the past tense, as if the research has already been completed.

What is the difference between my methodology and my methods?

There are three key aspects of any methodology section that you should aim to address:.

- Methodology: Your choice of methodology will be grounded in a discipline-specific theory about how research should proceed, such as quantitative or qualitative. This overarching decision will help to provide rationale for the specific methods you go on to use.

- Research Design: An explanation of the approach that you have chosen, and the type of data you will collect. For example, case study or action research? Will the data you collect be quantitative, qualitative or a mix of both?

- Methods: The concrete research tools used to collect and analyse data: questionnaires, in-person surveys, observations etc.

You may also need to include information on epistemology and your philosophical approach to research. You can find more information on this in our research planning guide.

What should I include in the methodology section?

Research paradigm: What is the underpinning philosophy of your research? How does this align with your research aim and objectives?

Methodology : Qualitative or quantitative? Mixed? What are the advantages of your chosen methodology, and why were the other options discounted?

- Research design : Show how your research design is influenced by other studies in your field and justify your choice of approach.

- Methods : What methods did you use? Why? Do these naturally fit together or do you need to justify why you have used different methods in combination?

- Participants/Data Sources: What were your sources/who were your participants? Which sampling approach did you use and why? How were they identified as a suitable group to research, and how were they recruited?

- Procedure : What did you do to collect your data? Remember, a reader should be able to replicate or adapt your methodology in their own research from the information you provide here.

- Limitations : What are the general limitations of your chosen method(s)? Don’t be specific here about your project (ie. what you could have done differently), but instead focus on what the literature outlines as the disadvantages of your methods.

Should I reflect on my position as a researcher?

If you feel your position as a researcher has influenced your choice of methods or procedure in any way, the methodology is a good place to reflect on this. Positionality acknowledges that no researcher is entirely objective: we are all, to some extent, influenced by prior learning, experiences, knowledge, and personal biases. This is particularly true in qualitative research or practice-based research, where the student is acting as a researcher in their own workplace, where they are otherwise considered a practitioner/professional.

The following questions can help you to reflect on your positionality and gauge whether this is an important section to include in your dissertation (for some people, this section isn’t necessary or relevant):

- How might my personal history influence how I approach the topic?

- How am I positioned in relation to this knowledge? Am I being influenced by prior learning or knowledge from outside of this course?

- How does my gender/social class/ ethnicity/ culture influence my positioning in relation to this topic?

- Do I share any attributes with my participants? Are we part of a s hared community? How might this have influenced our relationship and my role in interviews/observations?

- Am I invested in the outcomes on a personal level? Who is this research for and who will feel the benefits?

Visit our detailed guides on qualitative and quantitative research for more information.

- Quantitative projects

- Qualitative projects

T he purpose of this section is to report the findings of your study. In quantitative research, the results section usually functions as a statement of your findings without discussion.

Results sections generally begin with descriptive statistics before moving on to further tests such as multiple linear regression, or inferential statistical tests such as ANOVA, and any associated Post-Hoc testing.

Here are some top tips for planning/writing your results section:

- Explain any treatments you have applied to your data.

- Present your findings in a logical order.

- Describe trends in the data/anomalous findings but don’t start to interpret them. Save that for your discussion section.

- Figures and tables are usually the clearest way to present information. It is important to remember to title and label any titles/diagrams to communicate their meaning to the reader and so that you can refer to them again later in the report (e.g. Table 1).

- Remember to be consistent with the rounding of figures. If you start by rounding to 2 decimal places, ensure that you do this for all data you report.

- Avoid repeating any information - if something appears in a table it does not need to appear again in the main body of the text.

Presenting qualitative data

In qualitative studies, your results are often presented alongside the discussion, as it is difficult to include this data in a meaningful way without explanation and interpretation. In the dsicussion section, aim to structure your work thematically, moving through the key concepts or ideas that have emerged from your qualitative data. Use extracts from your data collection - interviews, focus groups, observations - to illustrate where these themes are most prominent, and refer back to the sources from your literature review to help draw conclusions.

Here's an example of how your data could be presented in paragraph format in this section:

Example from 'Reporting and discussing your findings ', Monash University .

What should I include in the discussion section?

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret your findings and discuss these against the context of the wider literature. This section should also highlight how your research has contributed to the understanding of a phenomenon or problem: this can be achieved by responding to your research questions.

Though the structure of discussion sections can vary, a relatively common structure is offered below:

- State your major findings – this can be a brief opening paragraph that restates the research problem, the methods you used to attempt to address this, and the major findings of your research.

- Address your research questions - detail your findings in relation to each of your research questions to help demonstrate how you have attempted to address the research problem. Answer each research question in turn by interpreting the relevant results: this may involve highlighting patterns, relationships or statistically significant differences depending on the design of your research and how you analysed your data.

- Discuss your findings against the wider literature - this will involve comparing and contrasting your findings against those of others and using key literature to support the interpretation of your results; often, this will involve revisiting key studies from your literature review and discussing where your findings fit in the pre-existing literature. This process can help to highlight the importance of your research through demonstrating what is novel about your findings and how this contributes to the wider understanding of your research area.

- Address any unexpected findings in your study - begin with by stating the unexpected finding and then offer your interpretation as to why this might have occurred. You may relate unexpected findings to other research literature and you should also consider how any unexpected findings relate to your overall study – especially if you think this is significant in terms of what your findings contribute to the understanding of your research problem!

- Discuss alternative interpretations - it’s important to remember that in research we find evidence to support ideas, theories and understanding; nothing is ever proven. Consequently, you should discuss possible alternative interpretations of your data – not just those that neatly answer your research questions and confirm your hypotheses.

- Limitations/weaknesses of your research – acknowledge any factors that might have affected your findings and discuss how this relates to your interpretation of the data. This might include detailing problems with your data collection method, or unanticipated factors that you had not accounted for in your original research plan. Likewise, detail any questions that your findings could not answer and explain why this was the case.

- Future directions (this part of your discussion could also be included in your conclusion) – this section should address what questions remain unanswered about your research problem. For example, it may be that your findings have answered some questions but raised new ones; this can often occur as a result of unanticipated findings. Likewise, some of the limitations of your research may necessitate further work to address a methodological confound or weakness in a tool of measurement. Whatever these future directions are, remember you’re not writing a proposal for this further research; a brief suggestion of what the research should do and how this would address one of the new problems/limitations you have identified is enough.

Here are some final top tips for writing your discussion section:

- Don’t rewrite your results section – remember your goal is to interpret and explain how your findings address the research problem.

- Be clear about what you have found, how this has addressed a gap in the literature and how it changes our understanding of your research problem.

- Structure your discussion in a logical way that highlights your most important/interesting findings first.

- Be careful about how you interpret your data: be wary over-interpreting to confirm a hypothesis. Remember, we can still learn from non-significant research findings.

- Avoid being apologetic or too critical when discussing the limitations of your research. Be concise and analytical.

How do I avoid repetition in the conclusion?

The conclusion is your opportunity to synthesise everything you have done/written as part of your research, in order to demonstrate your understanding.

A well-structured conclusion is likely to include the following:

- State your conclusions – in clear language, state the conclusions from your research. Crucially, this not just restating your results/findings: instead, this is a synthesis of the research problem, your research questions, your findings (and interpretation), and the relevant research literature. From your conclusions, it should be clear to your reader how our understanding of the research topic has changed.

- Discuss wider significance – this is your opportunity to highlight (potential) wider implications of your conclusions. Depending on your discipline, this might include recommendations for policy, professional practice or a tentative speculation about how an academic theory might change given your findings. It is important not to over-generalise here; remember the limitations of your theoretical and methodological choices and what these mean for the applicability of your findings/conclusions. If your discipline encourages reflection, this can be a suitable place to include your thoughts about the research process, the choices you made and how your findings/conclusions might influence your professional outlook/practice going forwards.

- Take home message – this should be a strong and clear final statement that draws the reader’s focus to the primary message of your study. Whilst it’s important to avoid being overly grandiose, this is your closing argument, and you should remind the reader of what your research has achieved.

Ultimately, your conclusion is your final word about the research problem you have investigated; don’t be afraid of emphasising your contribution to the understanding of that problem. Your conclusion should be clear, succinct and provide a summary of everything that has been learned as a result of your research project.

What supervisors expect from their dissertation students:

- to determine the focus and direction of the dissertation, particularly in terms of identifying a topic of interest and research question.

- to work independently to explore literature and research in the chosen topic area.

- to be proactive in arranging supervision meetings, email draft work before meetings for feedback and prepare specific questions and issues to discuss in supervision time.

- to be honest and open about any challenges or difficulties that arise during the research or writing process.

- to bring a problem-solving approach to the dissertation (you are not expected to know all the answers but should show initiative in exploring possible solutions to any problems that might arise).

What you can expect from your supervisor:

- to offer guidance on the best way to structure and carry out a successful research project in the timescale for your dissertation, and to help you to set achievable and appropriate research objectives.

- to act as an expert in your discipline and sounding board for your ideas, and to advise you on the literature search and theoretical background for your project.

- to serve as a 'lifeline' and point of support when the dissertation feels challenging.

- to read your drafts and give feedback in supervision meetings.

- to offer practical advice and strategies for managing your time, securing ethics approval, collecting data and common pitfalls to avoid during the research process.

Making the most of your supervision meetings

Meeting your supervisor can feel daunting at first but your supervision meetings offer a great opportunity to discuss your research ideas and get feedback on the direction of your project. Here are our top tips to getting the most out of time with your supervisor:

- Y ou are in charge of the agenda. If you arrange a meeting with your supervisor, you call the shots! Here are a few tips on how to get the most out of the time with your supervisor.

- Send an email in advance of the meeting , with an overview of the key ideas you want to talk about. This can save time in the meeting and helps to give you some structure to follow. If this isn't possible, run through these points quickly when you first sit down as you introduce the meeting - "I wanted to focus on the literature review today, as I'm having some trouble deciding on the order my key themes and points should be introduced in."

- What do you want to get out of the meeting? Note down any questions you would like the answers to or identify what it is you will need from the meeting in order to make progress on the next stage of your dissertation. Supervision meetings offer the change to talk about your ideas for the project, but they can also be an opportunity to find out practical details and troubleshoot. Don't leave the meeting until you have addressed these and got answers/advice in each key area.

- Trust your supervisor. Your supervisor may not be an expert in your chosen subject, but they will have experience of writing up research projects and coaching other dissertation students. You are responsible for reading up on your subject and exploring the literature - your supervisor can't tell you what to read, but they can give you advice on how to read your sources and integrate them into your argument and writing.

- Choose a short section to discuss in the meeting for feedback - for example, if you're not sure on structure, pick a page or two that demonstrate this, or if you want advice on being critical, find an example from a previous essay where you think you did this well and ask your supervisor how to translate this into dissertation writing.

- Agree an action plan . Work with your supervisor to set a goal for your next meeting, or an objective that you will meet in the week following your supervision. Feeling accountable to someone can be a great motivator and also helps you to recognise where you are starting to fall behind the targets that you've set for yourself.

- Be open and honest . It can feel daunting meeting your supervisor, but supervision meetings aren't an interview where you have to prove everything is going well. Ask for help and advice where you need it, and be honest if you're finding things difficult. A supervisor is there to support you and help you to develop the skills and knowledge you need along the journey to submitting your dissertation.

- << Previous: Quantitative research

- Next: e-learning and books >>

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 10:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/researchprojects

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 11 November 2022.

A dissertation proposal describes the research you want to do: what it’s about, how you’ll conduct it, and why it’s worthwhile. You will probably have to write a proposal before starting your dissertation as an undergraduate or postgraduate student.

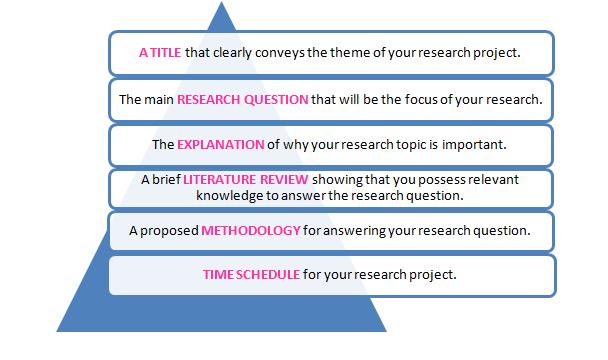

A dissertation proposal should generally include:

- An introduction to your topic and aims

- A literature review of the current state of knowledge

- An outline of your proposed methodology

- A discussion of the possible implications of the research

- A bibliography of relevant sources

Dissertation proposals vary a lot in terms of length and structure, so make sure to follow any guidelines given to you by your institution, and check with your supervisor when you’re unsure.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Step 1: coming up with an idea, step 2: presenting your idea in the introduction, step 3: exploring related research in the literature review, step 4: describing your methodology, step 5: outlining the potential implications of your research, step 6: creating a reference list or bibliography.

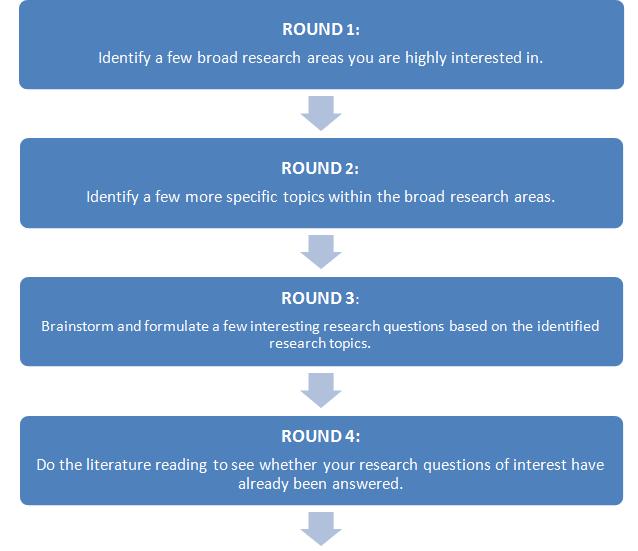

Before writing your proposal, it’s important to come up with a strong idea for your dissertation.

Find an area of your field that interests you and do some preliminary reading in that area. What are the key concerns of other researchers? What do they suggest as areas for further research, and what strikes you personally as an interesting gap in the field?

Once you have an idea, consider how to narrow it down and the best way to frame it. Don’t be too ambitious or too vague – a dissertation topic needs to be specific enough to be feasible. Move from a broad field of interest to a specific niche:

- Russian literature 19th century Russian literature The novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky

- Social media Mental health effects of social media Influence of social media on young adults suffering from anxiety

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Like most academic texts, a dissertation proposal begins with an introduction . This is where you introduce the topic of your research, provide some background, and most importantly, present your aim , objectives and research question(s) .

Try to dive straight into your chosen topic: What’s at stake in your research? Why is it interesting? Don’t spend too long on generalisations or grand statements:

- Social media is the most important technological trend of the 21st century. It has changed the world and influences our lives every day.

- Psychologists generally agree that the ubiquity of social media in the lives of young adults today has a profound impact on their mental health. However, the exact nature of this impact needs further investigation.

Once your area of research is clear, you can present more background and context. What does the reader need to know to understand your proposed questions? What’s the current state of research on this topic, and what will your dissertation contribute to the field?

If you’re including a literature review, you don’t need to go into too much detail at this point, but give the reader a general sense of the debates that you’re intervening in.

This leads you into the most important part of the introduction: your aim, objectives and research question(s) . These should be clearly identifiable and stand out from the text – for example, you could present them using bullet points or bold font.

Make sure that your research questions are specific and workable – something you can reasonably answer within the scope of your dissertation. Avoid being too broad or having too many different questions. Remember that your goal in a dissertation proposal is to convince the reader that your research is valuable and feasible:

- Does social media harm mental health?

- What is the impact of daily social media use on 18– to 25–year–olds suffering from general anxiety disorder?

Now that your topic is clear, it’s time to explore existing research covering similar ideas. This is important because it shows you what is missing from other research in the field and ensures that you’re not asking a question someone else has already answered.

You’ve probably already done some preliminary reading, but now that your topic is more clearly defined, you need to thoroughly analyse and evaluate the most relevant sources in your literature review .

Here you should summarise the findings of other researchers and comment on gaps and problems in their studies. There may be a lot of research to cover, so make effective use of paraphrasing to write concisely:

- Smith and Prakash state that ‘our results indicate a 25% decrease in the incidence of mechanical failure after the new formula was applied’.

- Smith and Prakash’s formula reduced mechanical failures by 25%.

The point is to identify findings and theories that will influence your own research, but also to highlight gaps and limitations in previous research which your dissertation can address:

- Subsequent research has failed to replicate this result, however, suggesting a flaw in Smith and Prakash’s methods. It is likely that the failure resulted from…

Next, you’ll describe your proposed methodology : the specific things you hope to do, the structure of your research and the methods that you will use to gather and analyse data.

You should get quite specific in this section – you need to convince your supervisor that you’ve thought through your approach to the research and can realistically carry it out. This section will look quite different, and vary in length, depending on your field of study.

You may be engaged in more empirical research, focusing on data collection and discovering new information, or more theoretical research, attempting to develop a new conceptual model or add nuance to an existing one.

Dissertation research often involves both, but the content of your methodology section will vary according to how important each approach is to your dissertation.

Empirical research

Empirical research involves collecting new data and analysing it in order to answer your research questions. It can be quantitative (focused on numbers), qualitative (focused on words and meanings), or a combination of both.

With empirical research, it’s important to describe in detail how you plan to collect your data:

- Will you use surveys ? A lab experiment ? Interviews?

- What variables will you measure?

- How will you select a representative sample ?

- If other people will participate in your research, what measures will you take to ensure they are treated ethically?

- What tools (conceptual and physical) will you use, and why?

It’s appropriate to cite other research here. When you need to justify your choice of a particular research method or tool, for example, you can cite a text describing the advantages and appropriate usage of that method.

Don’t overdo this, though; you don’t need to reiterate the whole theoretical literature, just what’s relevant to the choices you have made.

Moreover, your research will necessarily involve analysing the data after you have collected it. Though you don’t know yet what the data will look like, it’s important to know what you’re looking for and indicate what methods (e.g. statistical tests , thematic analysis ) you will use.

Theoretical research

You can also do theoretical research that doesn’t involve original data collection. In this case, your methodology section will focus more on the theory you plan to work with in your dissertation: relevant conceptual models and the approach you intend to take.

For example, a literary analysis dissertation rarely involves collecting new data, but it’s still necessary to explain the theoretical approach that will be taken to the text(s) under discussion, as well as which parts of the text(s) you will focus on:

- This dissertation will utilise Foucault’s theory of panopticism to explore the theme of surveillance in Orwell’s 1984 and Kafka’s The Trial…

Here, you may refer to the same theorists you have already discussed in the literature review. In this case, the emphasis is placed on how you plan to use their contributions in your own research.

You’ll usually conclude your dissertation proposal with a section discussing what you expect your research to achieve.

You obviously can’t be too sure: you don’t know yet what your results and conclusions will be. Instead, you should describe the projected implications and contribution to knowledge of your dissertation.

First, consider the potential implications of your research. Will you:

- Develop or test a theory?

- Provide new information to governments or businesses?

- Challenge a commonly held belief?

- Suggest an improvement to a specific process?

Describe the intended result of your research and the theoretical or practical impact it will have:

Finally, it’s sensible to conclude by briefly restating the contribution to knowledge you hope to make: the specific question(s) you hope to answer and the gap the answer(s) will fill in existing knowledge:

Like any academic text, it’s important that your dissertation proposal effectively references all the sources you have used. You need to include a properly formatted reference list or bibliography at the end of your proposal.

Different institutions recommend different styles of referencing – commonly used styles include Harvard , Vancouver , APA , or MHRA . If your department does not have specific requirements, choose a style and apply it consistently.

A reference list includes only the sources that you cited in your proposal. A bibliography is slightly different: it can include every source you consulted in preparing the proposal, even if you didn’t mention it in the text. In the case of a dissertation proposal, a bibliography may also list relevant sources that you haven’t yet read, but that you intend to use during the research itself.

Check with your supervisor what type of bibliography or reference list you should include.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 11). How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 27 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- Home »

find your perfect postgrad program Search our Database of 30,000 Courses

Everything you need to know about your research project.

For many postgraduate students, the RESEARCH PROJECT is the quintessential part of their course and the basis of their dissertation/thesis . The project is not only integral in passing the course but also serves as the final test of students’ capability to work independently and think critically.

Because postgraduate research projects bear such high importance, we have compiled the most important information that you as a prospective postgraduate student need to know about starting your first research project.

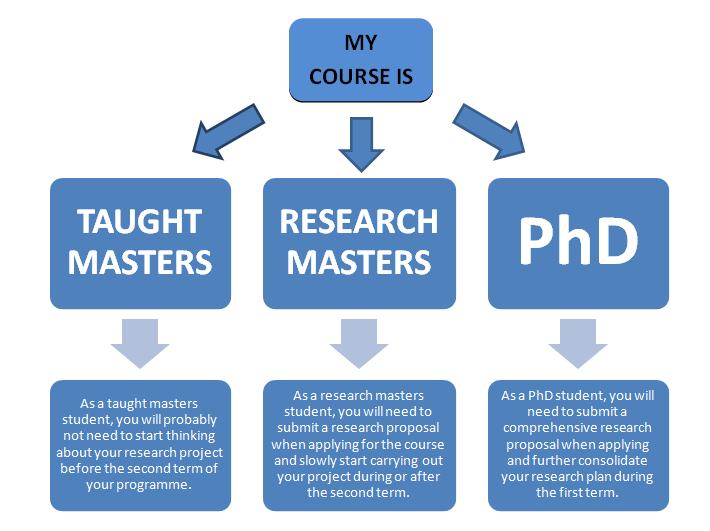

1. WHEN should I start planning my research project?

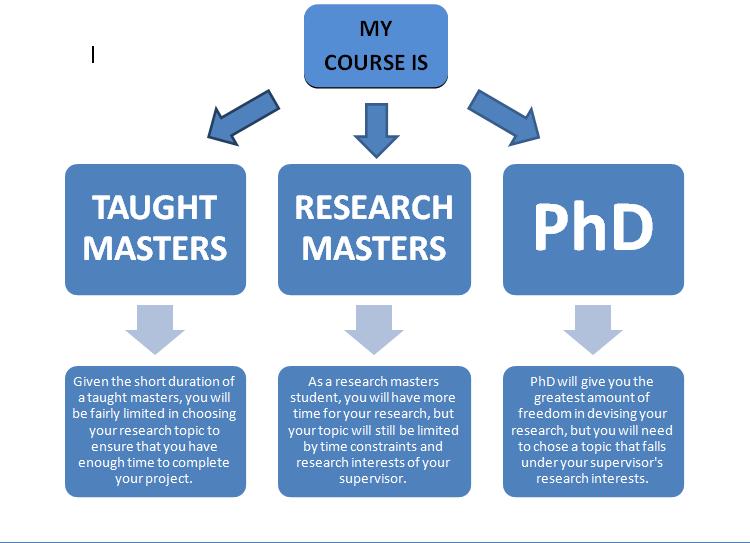

2. What FREEDOM will I have in choosing my research topic?

3. HOW do I choose an appropriate research topic?

4. WHAT should my research proposal contain?

As a masters student, your research proposal will need to be brief and contain only essential information. It will usually be between 500 and 1,000 words long. In contrast, PhD proposals are longer, between 1,000 and 2,500 words, and contain more comprehensive information. However, regardless of whether you are writing a masters or a PhD research proposal, it will need to cover the same key points:

5. What are the QUALITIES of a good research proposal?

A. It should be clearly written, well-structured, and presumably follow the chronology described under the previous section.

B. Your research project must be achievable and realistic rather than too ambitious. This means that you need to pay attention to time constraints, support all your statements by relevant literature, and show that you can think coherently about your subject.

C. Your research topic needs to ‘fill in’ some of the existing gaps encountered within the relevant literature.

D. If you are applying for a PhD under a specific supervisor, you need to show that you are familiar with his/her work and that you understand how it relates to your research topic.

E. If you are applying for funding, you need to make sure that your proposal clearly explains why your research is both relevant to the “real world” and to your research field, and you need to give convincing reasons for what makes your research idea outstanding.

F. Your research proposal must be driven by the curiosity to expand the knowledge about your research field rather than by choosing a research question just because you know that it can be easily answered and earn you the degree.

6. What will the CYCLE of my research project look like?

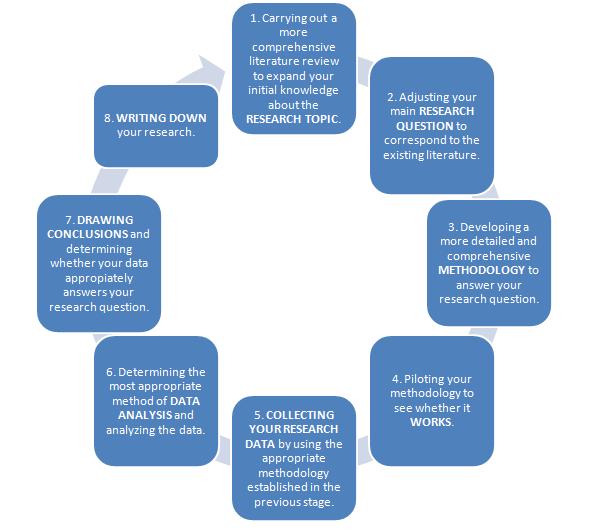

Once that your research proposal has been approved you will need to start your actual research project. Each research project is unique and different people have different ways of carrying out their research. However, there are some basic stages which may be relevant to all the research projects and we have compiled these stages to show you what a typical research cycle looks like:

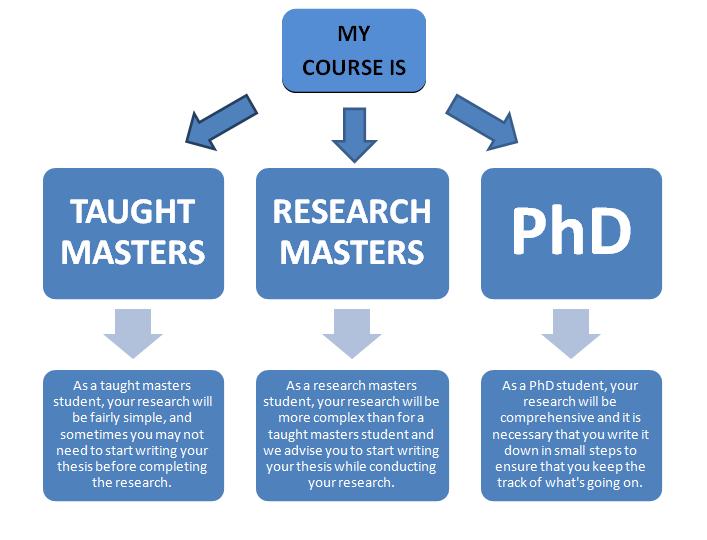

7. Is it better to START writing the dissertation/thesis after my research has been completed or to write it in small sections?

8. KEY POINTS

• A research project is at the core of many postgraduate courses. For PhD and research masters students it is the most important element of their course, whereas for taught masters students it is relatively less important but still highly relevant.

• Postgraduate research projects are usually written up in the form of a dissertation/thesis .

• Taught masters students usually need to start thinking about their research project during or after the second term of their studies, whereas research masters and PhD students need to know their research project in advance and describe it in a research proposal when applying for the course.

• The initial step in any research project is to choose the appropriate research topic. The most important factors to consider when choosing the research topic is whether it is personally inspiring for the student, whether it will contribute to existing literature in the field, and whether it is practical enough to be investigated within the specific time limit.

• PhD students usually have higher freedom in choosing their research topic because their course lasts for 3-4 years and they have the necessary knowledge to tackle more complex research issues. However, their choice is limited by their supervisor’s research interests and they need to undertake a project that can be completed within the duration of their course. In contrast, taught and research masters students are more limited in choosing their research topic because the duration of their course is shorter and their knowledge is still not developed enough to tackle more complex research issues.

• Once the appropriate research topic has been chosen, the student uses it to formulate the research proposal. Taught masters students usually need to submit their research proposal after the start of their course, whereas research masters and PhD students need to submit it while applying for the course. PhD research proposals are usually more comprehensive and 1,000-2,500 words long, whereas masters research proposals are simpler and 500-1,000 words long.

• Each research proposal should contain a title, the main research question, the explanation of why the topic studied is relevant, literature review, methodology, and time schedule.

• Good research proposals should have a clear structure and be adjusted to the time constraints of the course undertaken and to the research interests of the course supervisor.

• Once a research proposal has been approved, the student needs to start carrying out the actual research project. This process usually consists of a few stages: conducting a more comprehensive literature review, reconsidering the research question, devising a more detailed methodology and testing it to see whether it works, collecting research data and analysing it, drawing conclusions based on the data analysis, and describing the research in the dissertation/thesis.• Because PhD research projects are long and comprehensive, it is necessary that PhD students write their thesis in small steps to ensure that they keep track of what's going on in their research. Research masters students are also advised to write their thesis in two or three phases to break their research into smaller units that are easier to describe. Although research projects of taught master’s students are relatively less complex, and writing the thesis before the research has ended may sometimes not be necessary, it is always better to be early than to be late!

Related Articles

Dissertation Proposal

Top Tips When Writing Your Dissertation

How To Survive Your Masters Dissertation

Dissertation Methodology

Postgrads - Thinking About Your Thesis

Top Tips And Tools For Easy Postgraduate Research

How To Effectively Conduct Postgraduate Research

Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries

Exclusive bursaries Open day alerts Funding advice Application tips Latest PG news

Sign up now!

Take 2 minutes to sign up to PGS student services and reap the benefits…

- The chance to apply for one of our 5 PGS Bursaries worth £2,000 each

- Fantastic scholarship updates

- Latest PG news sent directly to you.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Table of Contents

Dissertation

Definition:

Dissertation is a lengthy and detailed academic document that presents the results of original research on a specific topic or question. It is usually required as a final project for a doctoral degree or a master’s degree.

Dissertation Meaning in Research

In Research , a dissertation refers to a substantial research project that students undertake in order to obtain an advanced degree such as a Ph.D. or a Master’s degree.

Dissertation typically involves the exploration of a particular research question or topic in-depth, and it requires students to conduct original research, analyze data, and present their findings in a scholarly manner. It is often the culmination of years of study and represents a significant contribution to the academic field.

Types of Dissertation

Types of Dissertation are as follows:

Empirical Dissertation

An empirical dissertation is a research study that uses primary data collected through surveys, experiments, or observations. It typically follows a quantitative research approach and uses statistical methods to analyze the data.

Non-Empirical Dissertation

A non-empirical dissertation is based on secondary sources, such as books, articles, and online resources. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as content analysis or discourse analysis.

Narrative Dissertation

A narrative dissertation is a personal account of the researcher’s experience or journey. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, focus groups, or ethnography.

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review is a comprehensive analysis of existing research on a specific topic. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as meta-analysis or thematic analysis.

Case Study Dissertation

A case study dissertation is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or organization. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, observations, or document analysis.

Mixed-Methods Dissertation

A mixed-methods dissertation combines both quantitative and qualitative research approaches to gather and analyze data. It typically uses methods such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as statistical analysis.

How to Write a Dissertation

Here are some general steps to help guide you through the process of writing a dissertation:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that you are passionate about and that is relevant to your field of study. It should be specific enough to allow for in-depth research but broad enough to be interesting and engaging.

- Conduct research : Conduct thorough research on your chosen topic, utilizing a variety of sources, including books, academic journals, and online databases. Take detailed notes and organize your information in a way that makes sense to you.

- Create an outline : Develop an outline that will serve as a roadmap for your dissertation. The outline should include the introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Write the introduction: The introduction should provide a brief overview of your topic, the research questions, and the significance of the study. It should also include a clear thesis statement that states your main argument.

- Write the literature review: The literature review should provide a comprehensive analysis of existing research on your topic. It should identify gaps in the research and explain how your study will fill those gaps.

- Write the methodology: The methodology section should explain the research methods you used to collect and analyze data. It should also include a discussion of any limitations or weaknesses in your approach.

- Write the results: The results section should present the findings of your research in a clear and organized manner. Use charts, graphs, and tables to help illustrate your data.

- Write the discussion: The discussion section should interpret your results and explain their significance. It should also address any limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research.

- Write the conclusion: The conclusion should summarize your main findings and restate your thesis statement. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

- Edit and revise: Once you have completed a draft of your dissertation, review it carefully to ensure that it is well-organized, clear, and free of errors. Make any necessary revisions and edits before submitting it to your advisor for review.

Dissertation Format

The format of a dissertation may vary depending on the institution and field of study, but generally, it follows a similar structure:

- Title Page: This includes the title of the dissertation, the author’s name, and the date of submission.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the dissertation’s purpose, methods, and findings.

- Table of Contents: A list of the main sections and subsections of the dissertation, along with their page numbers.

- Introduction : A statement of the problem or research question, a brief overview of the literature, and an explanation of the significance of the study.

- Literature Review : A comprehensive review of the literature relevant to the research question or problem.

- Methodology : A description of the methods used to conduct the research, including data collection and analysis procedures.

- Results : A presentation of the findings of the research, including tables, charts, and graphs.

- Discussion : A discussion of the implications of the findings, their significance in the context of the literature, and limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : A summary of the main points of the study and their implications for future research.

- References : A list of all sources cited in the dissertation.

- Appendices : Additional materials that support the research, such as data tables, charts, or transcripts.

Dissertation Outline

Dissertation Outline is as follows:

Title Page:

- Title of dissertation

- Author name

- Institutional affiliation

- Date of submission

- Brief summary of the dissertation’s research problem, objectives, methods, findings, and implications

- Usually around 250-300 words

Table of Contents:

- List of chapters and sections in the dissertation, with page numbers for each

I. Introduction

- Background and context of the research

- Research problem and objectives

- Significance of the research

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing literature on the research topic

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Theoretical framework and concepts

III. Methodology

- Research design and methods used

- Data collection and analysis techniques

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation and analysis of data collected

- Findings and outcomes of the research

- Interpretation of the results

V. Discussion

- Discussion of the results in relation to the research problem and objectives

- Evaluation of the research outcomes and implications

- Suggestions for future research

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of the research findings and outcomes

- Implications for the research topic and field

- Limitations and recommendations for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the dissertation

VIII. Appendices

- Additional materials that support the research, such as tables, figures, or questionnaires.

Example of Dissertation

Here is an example Dissertation for students:

Title : Exploring the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Achievement and Well-being among College Students

This dissertation aims to investigate the impact of mindfulness meditation on the academic achievement and well-being of college students. Mindfulness meditation has gained popularity as a technique for reducing stress and enhancing mental health, but its effects on academic performance have not been extensively studied. Using a randomized controlled trial design, the study will compare the academic performance and well-being of college students who practice mindfulness meditation with those who do not. The study will also examine the moderating role of personality traits and demographic factors on the effects of mindfulness meditation.

Chapter Outline:

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Background and rationale for the study

- Research questions and objectives

- Significance of the study

- Overview of the dissertation structure

Chapter 2: Literature Review

- Definition and conceptualization of mindfulness meditation

- Theoretical framework of mindfulness meditation

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and academic achievement

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and well-being

- The role of personality and demographic factors in the effects of mindfulness meditation

Chapter 3: Methodology

- Research design and hypothesis

- Participants and sampling method

- Intervention and procedure

- Measures and instruments

- Data analysis method

Chapter 4: Results

- Descriptive statistics and data screening

- Analysis of main effects

- Analysis of moderating effects

- Post-hoc analyses and sensitivity tests

Chapter 5: Discussion

- Summary of findings

- Implications for theory and practice

- Limitations and directions for future research

- Conclusion and contribution to the literature

Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Recap of the research questions and objectives

- Summary of the key findings

- Contribution to the literature and practice

- Implications for policy and practice

- Final thoughts and recommendations.

References :

List of all the sources cited in the dissertation

Appendices :

Additional materials such as the survey questionnaire, interview guide, and consent forms.

Note : This is just an example and the structure of a dissertation may vary depending on the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the institution or the supervisor.

How Long is a Dissertation

The length of a dissertation can vary depending on the field of study, the level of degree being pursued, and the specific requirements of the institution. Generally, a dissertation for a doctoral degree can range from 80,000 to 100,000 words, while a dissertation for a master’s degree may be shorter, typically ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 words. However, it is important to note that these are general guidelines and the actual length of a dissertation can vary widely depending on the specific requirements of the program and the research topic being studied. It is always best to consult with your academic advisor or the guidelines provided by your institution for more specific information on dissertation length.

Applications of Dissertation

Here are some applications of a dissertation:

- Advancing the Field: Dissertations often include new research or a new perspective on existing research, which can help to advance the field. The results of a dissertation can be used by other researchers to build upon or challenge existing knowledge, leading to further advancements in the field.

- Career Advancement: Completing a dissertation demonstrates a high level of expertise in a particular field, which can lead to career advancement opportunities. For example, having a PhD can open doors to higher-paying jobs in academia, research institutions, or the private sector.

- Publishing Opportunities: Dissertations can be published as books or journal articles, which can help to increase the visibility and credibility of the author’s research.

- Personal Growth: The process of writing a dissertation involves a significant amount of research, analysis, and critical thinking. This can help students to develop important skills, such as time management, problem-solving, and communication, which can be valuable in both their personal and professional lives.

- Policy Implications: The findings of a dissertation can have policy implications, particularly in fields such as public health, education, and social sciences. Policymakers can use the research to inform decision-making and improve outcomes for the population.

When to Write a Dissertation

Here are some situations where writing a dissertation may be necessary:

- Pursuing a Doctoral Degree: Writing a dissertation is usually a requirement for earning a doctoral degree, so if you are interested in pursuing a doctorate, you will likely need to write a dissertation.

- Conducting Original Research : Dissertations require students to conduct original research on a specific topic. If you are interested in conducting original research on a topic, writing a dissertation may be the best way to do so.

- Advancing Your Career: Some professions, such as academia and research, may require individuals to have a doctoral degree. Writing a dissertation can help you advance your career by demonstrating your expertise in a particular area.

- Contributing to Knowledge: Dissertations are often based on original research that can contribute to the knowledge base of a field. If you are passionate about advancing knowledge in a particular area, writing a dissertation can help you achieve that goal.

- Meeting Academic Requirements : If you are a graduate student, writing a dissertation may be a requirement for completing your program. Be sure to check with your academic advisor to determine if this is the case for you.

Purpose of Dissertation

some common purposes of a dissertation include:

- To contribute to the knowledge in a particular field : A dissertation is often the culmination of years of research and study, and it should make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field.

- To demonstrate mastery of a subject: A dissertation requires extensive research, analysis, and writing, and completing one demonstrates a student’s mastery of their subject area.

- To develop critical thinking and research skills : A dissertation requires students to think critically about their research question, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on evidence. These skills are valuable not only in academia but also in many professional fields.

- To demonstrate academic integrity: A dissertation must be conducted and written in accordance with rigorous academic standards, including ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent, protecting the privacy of participants, and avoiding plagiarism.

- To prepare for an academic career: Completing a dissertation is often a requirement for obtaining a PhD and pursuing a career in academia. It can demonstrate to potential employers that the student has the necessary skills and experience to conduct original research and make meaningful contributions to their field.

- To develop writing and communication skills: A dissertation requires a significant amount of writing and communication skills to convey complex ideas and research findings in a clear and concise manner. This skill set can be valuable in various professional fields.

- To demonstrate independence and initiative: A dissertation requires students to work independently and take initiative in developing their research question, designing their study, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. This demonstrates to potential employers or academic institutions that the student is capable of independent research and taking initiative in their work.

- To contribute to policy or practice: Some dissertations may have a practical application, such as informing policy decisions or improving practices in a particular field. These dissertations can have a significant impact on society, and their findings may be used to improve the lives of individuals or communities.

- To pursue personal interests: Some students may choose to pursue a dissertation topic that aligns with their personal interests or passions, providing them with the opportunity to delve deeper into a topic that they find personally meaningful.

Advantage of Dissertation

Some advantages of writing a dissertation include:

- Developing research and analytical skills: The process of writing a dissertation involves conducting extensive research, analyzing data, and presenting findings in a clear and coherent manner. This process can help students develop important research and analytical skills that can be useful in their future careers.

- Demonstrating expertise in a subject: Writing a dissertation allows students to demonstrate their expertise in a particular subject area. It can help establish their credibility as a knowledgeable and competent professional in their field.

- Contributing to the academic community: A well-written dissertation can contribute new knowledge to the academic community and potentially inform future research in the field.

- Improving writing and communication skills : Writing a dissertation requires students to write and present their research in a clear and concise manner. This can help improve their writing and communication skills, which are essential for success in many professions.

- Increasing job opportunities: Completing a dissertation can increase job opportunities in certain fields, particularly in academia and research-based positions.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .

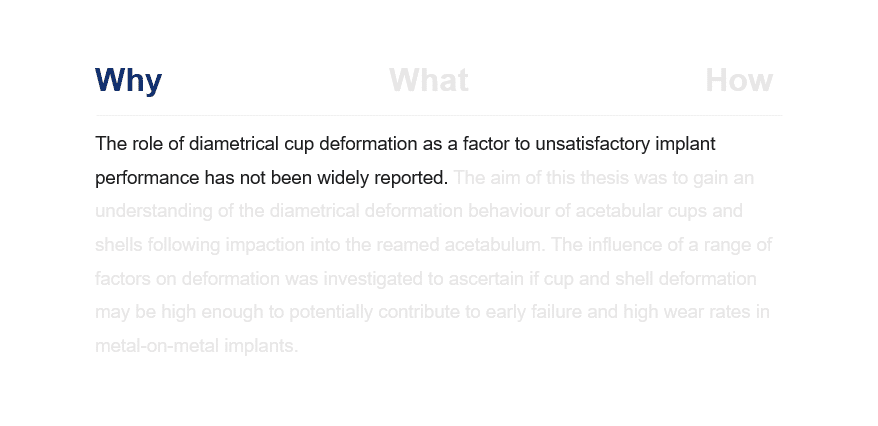

A research aim is usually formulated as a broad statement of the main goal of the research and can range in length from a single sentence to a short paragraph. Although the exact format may vary according to preference, they should all describe why your research is needed (i.e. the context), what it sets out to accomplish (the actual aim) and, briefly, how it intends to accomplish it (overview of your objectives).

To give an example, we have extracted the following research aim from a real PhD thesis:

Example of a Research Aim

The role of diametrical cup deformation as a factor to unsatisfactory implant performance has not been widely reported. The aim of this thesis was to gain an understanding of the diametrical deformation behaviour of acetabular cups and shells following impaction into the reamed acetabulum. The influence of a range of factors on deformation was investigated to ascertain if cup and shell deformation may be high enough to potentially contribute to early failure and high wear rates in metal-on-metal implants.

Note: Extracted with permission from thesis titled “T he Impact And Deformation Of Press-Fit Metal Acetabular Components ” produced by Dr H Hothi of previously Queen Mary University of London.

Research Objectives

Where a research aim specifies what your study will answer, research objectives specify how your study will answer it.

They divide your research aim into several smaller parts, each of which represents a key section of your research project. As a result, almost all research objectives take the form of a numbered list, with each item usually receiving its own chapter in a dissertation or thesis.

Following the example of the research aim shared above, here are it’s real research objectives as an example:

Example of a Research Objective

- Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

- Investigate the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup.

- Determine the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types.

- Investigate the influence of non-uniform cup support and varying the orientation of the component in the cavity on deformation.

- Examine the influence of errors during reaming of the acetabulum which introduce ovality to the cavity.

- Determine the relationship between changes in the geometry of the component and deformation for different cup designs.

- Develop three dimensional pelvis models with non-uniform bone material properties from a range of patients with varying bone quality.

- Use the key parameters that influence deformation, as identified in the foam models to determine the range of deformations that may occur clinically using the anatomic models and if these deformations are clinically significant.

It’s worth noting that researchers sometimes use research questions instead of research objectives, or in other cases both. From a high-level perspective, research questions and research objectives make the same statements, but just in different formats.

Taking the first three research objectives as an example, they can be restructured into research questions as follows:

Restructuring Research Objectives as Research Questions

- Can finite element models using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum together with explicit dynamics be used to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion?

- What is the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup?

- What is the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types?

Difference Between Aims and Objectives

Hopefully the above explanations make clear the differences between aims and objectives, but to clarify:

- The research aim focus on what the research project is intended to achieve; research objectives focus on how the aim will be achieved.

- Research aims are relatively broad; research objectives are specific.

- Research aims focus on a project’s long-term outcomes; research objectives focus on its immediate, short-term outcomes.

- A research aim can be written in a single sentence or short paragraph; research objectives should be written as a numbered list.

How to Write Aims and Objectives

Before we discuss how to write a clear set of research aims and objectives, we should make it clear that there is no single way they must be written. Each researcher will approach their aims and objectives slightly differently, and often your supervisor will influence the formulation of yours on the basis of their own preferences.

Regardless, there are some basic principles that you should observe for good practice; these principles are described below.

Your aim should be made up of three parts that answer the below questions:

- Why is this research required?

- What is this research about?

- How are you going to do it?

The easiest way to achieve this would be to address each question in its own sentence, although it does not matter whether you combine them or write multiple sentences for each, the key is to address each one.

The first question, why , provides context to your research project, the second question, what , describes the aim of your research, and the last question, how , acts as an introduction to your objectives which will immediately follow.

Scroll through the image set below to see the ‘why, what and how’ associated with our research aim example.

Note: Your research aims need not be limited to one. Some individuals per to define one broad ‘overarching aim’ of a project and then adopt two or three specific research aims for their thesis or dissertation. Remember, however, that in order for your assessors to consider your research project complete, you will need to prove you have fulfilled all of the aims you set out to achieve. Therefore, while having more than one research aim is not necessarily disadvantageous, consider whether a single overarching one will do.

Research Objectives

Each of your research objectives should be SMART :

- Specific – is there any ambiguity in the action you are going to undertake, or is it focused and well-defined?

- Measurable – how will you measure progress and determine when you have achieved the action?

- Achievable – do you have the support, resources and facilities required to carry out the action?

- Relevant – is the action essential to the achievement of your research aim?

- Timebound – can you realistically complete the action in the available time alongside your other research tasks?

In addition to being SMART, your research objectives should start with a verb that helps communicate your intent. Common research verbs include:

Table of Research Verbs to Use in Aims and Objectives

Last, format your objectives into a numbered list. This is because when you write your thesis or dissertation, you will at times need to make reference to a specific research objective; structuring your research objectives in a numbered list will provide a clear way of doing this.

To bring all this together, let’s compare the first research objective in the previous example with the above guidance:

Checking Research Objective Example Against Recommended Approach

Research Objective:

1. Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

Checking Against Recommended Approach:

Q: Is it specific? A: Yes, it is clear what the student intends to do (produce a finite element model), why they intend to do it (mimic cup/shell blows) and their parameters have been well-defined ( using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum ).

Q: Is it measurable? A: Yes, it is clear that the research objective will be achieved once the finite element model is complete.

Q: Is it achievable? A: Yes, provided the student has access to a computer lab, modelling software and laboratory data.

Q: Is it relevant? A: Yes, mimicking impacts to a cup/shell is fundamental to the overall aim of understanding how they deform when impacted upon.

Q: Is it timebound? A: Yes, it is possible to create a limited-scope finite element model in a relatively short time, especially if you already have experience in modelling.

Q: Does it start with a verb? A: Yes, it starts with ‘develop’, which makes the intent of the objective immediately clear.

Q: Is it a numbered list? A: Yes, it is the first research objective in a list of eight.

Mistakes in Writing Research Aims and Objectives

1. making your research aim too broad.

Having a research aim too broad becomes very difficult to achieve. Normally, this occurs when a student develops their research aim before they have a good understanding of what they want to research. Remember that at the end of your project and during your viva defence , you will have to prove that you have achieved your research aims; if they are too broad, this will be an almost impossible task. In the early stages of your research project, your priority should be to narrow your study to a specific area. A good way to do this is to take the time to study existing literature, question their current approaches, findings and limitations, and consider whether there are any recurring gaps that could be investigated .

Note: Achieving a set of aims does not necessarily mean proving or disproving a theory or hypothesis, even if your research aim was to, but having done enough work to provide a useful and original insight into the principles that underlie your research aim.

2. Making Your Research Objectives Too Ambitious

Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time you have available. It is natural to want to set ambitious research objectives that require sophisticated data collection and analysis, but only completing this with six months before the end of your PhD registration period is not a worthwhile trade-off.

3. Formulating Repetitive Research Objectives

Each research objective should have its own purpose and distinct measurable outcome. To this effect, a common mistake is to form research objectives which have large amounts of overlap. This makes it difficult to determine when an objective is truly complete, and also presents challenges in estimating the duration of objectives when creating your project timeline. It also makes it difficult to structure your thesis into unique chapters, making it more challenging for you to write and for your audience to read.

Fortunately, this oversight can be easily avoided by using SMART objectives.

Hopefully, you now have a good idea of how to create an effective set of aims and objectives for your research project, whether it be a thesis, dissertation or research paper. While it may be tempting to dive directly into your research, spending time on getting your aims and objectives right will give your research clear direction. This won’t only reduce the likelihood of problems arising later down the line, but will also lead to a more thorough and coherent research project.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

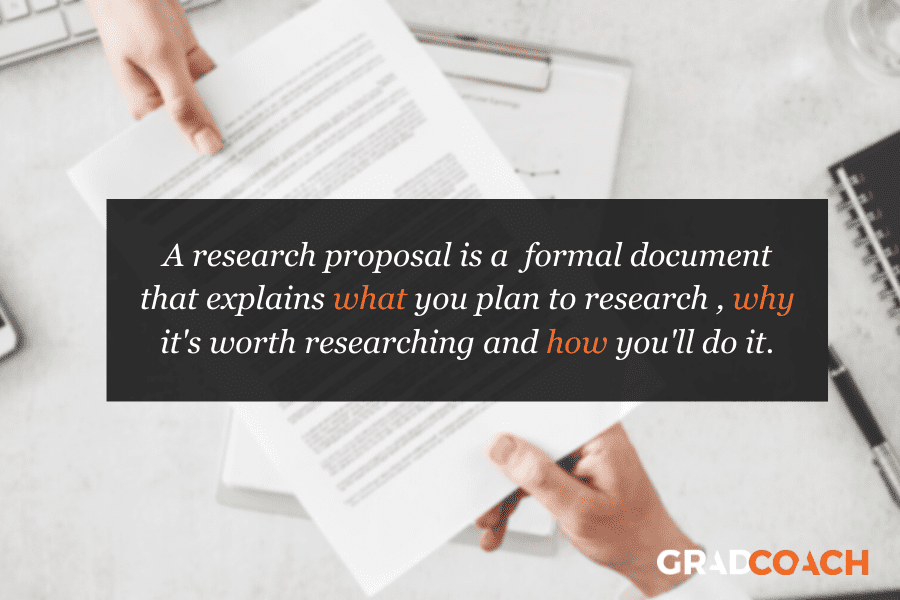

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?