Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Research ethics review during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international study

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Current address: Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Affiliation Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, Sinai Health, Toronto, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, Sinai Health, Toronto, Canada, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University, London, Canada

- Fabio Salamanca-Buentello,

- Rachel Katz,

- Diego S. Silva,

- Ross E. G. Upshur,

- Maxwell J. Smith

- Published: April 16, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512

- Reader Comments

Research ethics review committees (ERCs) worldwide faced daunting challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a need to balance rapid turnaround with rigorous evaluation of high-risk research protocols in the context of considerable uncertainty. This study explored the experiences and performance of ERCs during the pandemic. We conducted an anonymous, cross-sectional, global online survey of chairs (or their delegates) of ERCs who were involved in the review of COVID-19-related research protocols after March 2020. The survey ran from October 2022 to February 2023 and consisted of 50 items, with opportunities for descriptive responses to open-ended questions. Two hundred and three participants [130 from high-income countries (HICs) and 73 from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)] completed our survey. Respondents came from diverse entities and organizations from 48 countries (19 HICs and 29 LMICs) in all World Health Organization regions. Responses show little of the increased global funding for COVID-19 research was allotted to the operation of ERCs. Few ERCs had pre-existing internal policies to address operation during public health emergencies, but almost half used existing guidelines. Most ERCs modified existing procedures or designed and implemented new ones but had not evaluated the success of these changes. Participants overwhelmingly endorsed permanently implementing several of them. Few ERCs added new members but non-member experts were consulted; quorum was generally achieved. Collaboration among ERCs was infrequent, but reviews conducted by external ERCs were recognized and validated. Review volume increased during the pandemic, with COVID-19-related studies being prioritized. Most protocol reviews were reported as taking less than three weeks. One-third of respondents reported external pressure on their ERCs from different stakeholders to approve or reject specific COVID-19-related protocols. ERC members faced significant challenges to keep their committees functioning during the pandemic. Our findings can inform ERC approaches towards future public health emergencies. To our knowledge, this is the first international, COVID-19-related study of its kind.

Citation: Salamanca-Buentello F, Katz R, Silva DS, Upshur REG, Smith MJ (2024) Research ethics review during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international study. PLoS ONE 19(4): e0292512. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512

Editor: Collins Atta Poku, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, GHANA

Received: September 5, 2023; Accepted: March 23, 2024; Published: April 16, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Salamanca-Buentello et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data for this study are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. Additionally, the raw survey data are available from the figshare database ( https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24076704 ).

Funding: This study was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant #C150-2019-11 ( https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/193.html ) awarded to MJS. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The ethical review of research protocols during public health emergencies (PHEs) such as the COVID-19 pandemic is a daunting endeavour. Committees tasked with assessing the ethical acceptability of research projects, which we refer to as ethics review committees (ERCs) but are also variably called research ethics boards, research ethics committees, ethics review boards, and institutional review boards, face challenges to reviewing research protocols swiftly while maintaining a high degree of rigour, all under suboptimal conditions and uncertainty. ERCs must balance the urge for rapid turnaround and flexibility with the requirement for intense scrutiny given that new projects often propose innovative but high-risk diagnostic, therapeutic, or preventive approaches to address the PHE. This is especially challenging in the case of countries with fragile health systems, poor infrastructure, and little experience conducting medical research, and also of countries experiencing protracted emergencies [ 1 – 5 ].

Failure to ensure rigour and depth during rapid ethics reviews in public health emergencies may place research participants at risk [ 6 ]. In such challenging circumstances, ERCs must consider how interventions, study design, eligibility criteria, community engagement, and approaches to vulnerable populations impact scientific validity, participant autonomy, respect for persons, welfare, justice, and social value [ 2 , 7 – 9 ]. Additional demands on ERCs may include the ability to incorporate and respond swiftly to newly available knowledge, to provide monitoring and oversight of research, and to grapple with the impact of the PHE on those involved in the research process, such as research participants, investigators, and ERC members and staff [ 7 ].

Public health emergencies force ERCs to make reasonable adjustments and design innovative strategies to address the various components of research ethics review while still adhering to ethical principles [ 3 , 6 , 7 , 10 ]. Moreover, after a PHE, changes implemented to secure continued operations of ERCs must be evaluated to determine their success and whether they should be permanently put in place to improve the everyday functioning of the committees.

Given the challenges that ERCs worldwide faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, we aimed in this exploratory study to identify their experiences in the attempt to adapt to this PHE. We were particularly interested in the availability of pandemic-specific support, the promptness of protocol review, the volume of protocols received, the modifications to and innovations in operational procedures and policies and the evaluation of their outcomes, the anticipated permanence of such changes beyond the pandemic, the presence of pressure from different stakeholders on ERCs, the efforts to ensure quorum, the changes to the composition of ERCs, and the approaches to strengthen inter-ERC collaboration. To our knowledge, this is the first international, COVID-19-related study of its kind.

This international, cross-sectional, exploratory online survey was conducted by researchers from Western University, the University of Toronto, and the Lunenfeld–Tanenbaum Research Institute in Canada, and the University of Sydney in Australia, in collaboration with the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Ethics and Governance Working Group.

Inclusion criteria

We used targeted purposive and criterion sampling to invite Chairs and members of ERCs who were actively involved in the ethics review of COVID-19 research protocols to participate in this study. To ensure eligibility of participants, the first question of the survey asked respondents to confirm whether they had reviewed COVID-19-related research protocols during the pandemic. Responding to our survey was entirely voluntary. For the purposes of this study, we considered March 2020 as the beginning of this PHE. We specifically targeted individuals from all WHO regions. Participants were assigned to either of two categories: high-income countries (HICs) or low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), according to their reported country of residence. To do this, we used the World Bank classification of countries ( https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups ), which is based on gross national income per capita. We adopted this widely used categorization notwithstanding its limitations in terms of hiding power imbalances and reducing important differences among countries to questions of economics [ 11 ].

Survey questionnaire

The complete questionnaire is available as S1 Appendix . The overall structure and flow of the survey questionnaire, which consisted of a main “trunk” of 37 items organized into 11 thematic categories, is shown in Fig 1 . As can be seen in this figure, eight of these items branched into different survey flow elements based on respondents’ answers; seven of these eight items branched into elements with questions (six of them contained two questions). Thus, in total, the questionnaire, written in English, included 50 questions. We privileged close-ended over open-ended questions, but we allowed respondents the opportunity to provide additional comments for some items. We pilot-tested the online questionnaire with a small group of experts who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. This helped polish the wording of the questions and also assess and improve the logistics of the administration of the survey.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.g001

Data collection

The invitation to participate in the survey explained the nature and purpose of our study, the inclusion criteria used to select participants, a summary of the procedures involved, and the URL link to the survey. These invitations were initially distributed by email by the WHO’s COVID-19 Ethics and Governance Working Group through the email listserv of the 13th Global Summit of National Ethics Committees (an event that took place in September 2022). The Working Group identified additional potential participants among its extensive contact networks. We also circulated the invitation to experts identified by the research team. Invitations could also be forwarded to individuals designated by ERCs.

Our survey was active from October 11, 2022, to February 28, 2023. We used the Qualtrics Experience Management (XM) online platform to administer the questionnaire, which was open only to individuals who received the invitation with the link to the survey.

Data analysis

The analysis of the findings of this exploratory study employed descriptive statistics and stratified the comparison between responses of participants from HICs with those of participants from LMICs. To facilitate the examination of the results, tables were prepared showing the number and percentage of respondents from HICs and LMICs who answered each question in the survey. Qualitative data (descriptive responses to open-ended questions) were evaluated using thematic analysis and the constant comparative method.

Research ethics approval

Our study received approval from Western University’s Non-Medical Research Ethics Board (Protocol ID 120455). Additionally, it was evaluated by the World Health Organization Research Ethics Review Committee (Protocol ID CERC.0181) and was exempted from further review. The use of the Qualtrics platform facilitated data collection and management while respecting the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Respondents indicated their consent to participate in our survey by selecting a button labelled “I consent” at the end of the letter of information and consent, which appeared on the first page of the questionnaire. Responses were anonymous to protect participants’ privacy and confidentiality and encourage the open sharing of experiences.

Reporting survey results

While no universally agreed-upon reporting standards for surveys exist like there are for clinical trials and meta-analyses, the EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network has recently (2021) proposed a checklist for reporting of survey studies [ 12 ]. EQUATOR has been responsible for the development of several of these standards, including the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for randomized control trials; Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) for observational studies; and Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Even though this is not a globally recognized official standard, it is quite useful, and we have ensured that our manuscript fulfills all the reporting requirements included in this checklist.

Characterization of survey respondents

Two hundred and eighty-one individuals opened our survey. Of these, 250 answered the first question, which confirmed whether respondents fulfilled our inclusion criteria, and with which we could confirm their eligibility. Forty-three individuals explicitly indicated that they did not meet our criteria. Thus, the initial number of suitable respondents was 207. As expected in surveys such as ours in which participants are allowed to skip questions, the number of respondents per question varied slightly, from a maximum of 207 to a minimum of 147.

Of the 204 participants who indicated their sex / gender, 120 (58.8%) were female, 82 (40.2%) were male, one (0.5%) preferred to self-describe, and one (0.5%) preferred not to disclose this information ( Box 1 , Table a ). The proportion of females was higher in HICs (64.9%) than in LMICs (47.9%); thus, the distribution of respondents by sex / gender was more balanced in LMICs than in HICs. As shown in Box 1 , Table b , more than three quarters of respondents (77.9%) were 45 years old or older. This was true for both HICs and LMICs. Most respondents provided ethics review for national bodies such as national ethics committees or national public health organizations; more than a quarter participated in ERCs linked to academic or research institutions ( Box 1 , Table c ). However, while almost half of respondents from HICs were members of ERCs affiliated with national bodies, only one quarter of participants from LMICs provided ethics review for such organizations. In contrast, in LMICs, 40% of respondents were members of ERCs associated with academic or research institutions. Furthermore, only 20% of participants from LMICs and 13.9% of participants from HICs provided ethics review for health care facilities.

Box 1. Characterization of survey participants

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.t001

In terms of the WHO region for which ethics review was provided, all regions were represented in our survey ( S1 Table in S2 Appendix ). More than one third of respondents reviewed research protocols from Europe, almost one fifth from the Americas, one tenth from Africa, and less than one tenth each from the other WHO regions.

Table 1 shows the number of respondents by country of residence. Participants from 48 countries (19 HICs and 29 LMICs) responded to our survey. Of the 203 individuals who indicated their country of residence, 130 (64%) were from HICs and 73 (36%) from LMICs. There was a large contingent of respondents from the UK (93).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.t002

Two thirds of respondents had six or more years of experience as ERC members. This is true for participants from both HICs and LMICs ( S2 Table in S2 Appendix ).

As shown in S3 Table in S2 Appendix , about one half of respondents (52%) were involved in only one ERC. This pattern was common for participants from HICs and LMICs. However, more than one third of respondents from HICs participated in three or more ERCs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of those who indicated involvement with multiple ERCs, close to one half specified that such participation was simultaneous ( S4 Table in S2 Appendix ).

Support for the operation of ERCs during the pandemic

As shown in S5 Table in S2 Appendix , an overwhelming majority (78.4%) of respondents indicated that their ERCs received no additional support for the operation of their committees during the pandemic. This lack of support was more pronounced in the case of ERCs in LMICs. For the minority of ERCs that did receive support, this consisted mainly of administrative and human resources, with one quarter of respondents from LMICs stating that their ERCs also received financial support, in contrast to only 12.5% of those from HICs ( S6 Table in S2 Appendix ). In terms of specific areas supported, participants from both HICs and LMICs mentioned teleconferencing and virtual meeting capabilities, information technology, support staff, assistance for ERC reviewers, and training of ERC members ( Table 2 ). Interestingly, while 20% of respondents from HICs chose ERC support staff as one of the areas that received assistance, only 7.5% of those from LMICs did.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.t003

In their descriptive responses, participants alluded to support for covering the costs of using online platforms for meetings and protocol review, and for acquiring or upgrading hardware such as laptops and webcams. In one ERC, members were able to claim costs of setting up teleconferencing and of telephone calls if dialling into a meeting. In other ERCs, information technology training was offered, along with technical support for the use of online platforms. It is important to note that almost half of respondents from HICs, but close to the totality (91.4%) of those from LMICs, indicated that their ERCs lacked any pre-pandemic financial planning that included provisions for the support of the committees during a public health emergency ( S7 Table in S2 Appendix ).

Modification of existing procedures or policies

Respondents from both HICs and LMICs overwhelmingly (more than 75% of participants in both cases) reported that their ERCs modified existing procedures or policies to operate during the pandemic ( S8 Table in S2 Appendix ). The most frequently modified domain was meeting logistics, followed by meeting frequency and procedures for protocol review and approval ( S9 Table in S2 Appendix ).

In terms of modifications to review procedures, several participants pointed out in their descriptive responses that their ERCs fast-tracked the review of pandemic-related studies, shortening the timeline to review and approve protocols. ERC members were expected to complete the review of these protocols within a few days and, in some cases, 24 hours. To facilitate such a quick turnaround, some ERCs created special sub-committees that would conduct very fast protocol reviews. Moreover, participants emphasized the importance of simplifying and increasing the flexibility of administrative processes. For example, several respondents indicated that their ERCs switched entirely to the use of online platforms for protocol review, eliminating the need for paper documents.

Numerous participants stated that all ERC meetings were conducted virtually (as opposed to face-to-face) during the pandemic, which, in their view, enabled ERC members and researchers to participate regardless of geographical location, prevented contagion, and allowed rapid turnaround of reviews. Even in the case of virtual sessions, all other full meeting requirements such as quorum had to be met. Some ERCs modified their meetings to open a permanent slot in their agendas for COVID-19-related research or added urgent full meetings to discuss top-priority pandemic-related trial protocols. In other cases, members were permanently available to review COVID-19-related protocols, with those pertaining to other topics addressed less frequently.

While most respondents acknowledged the advantages of using online platforms during the pandemic to organize ERC meetings and to review research protocols, several participants highlighted the challenges that the use of such technologies entailed, particularly for new and more senior members of the ERCs who felt uncomfortable using these platforms. Some individuals deplored the loss of quality in the dynamics among ERC members (stilted conversations, fewer informal interactions) compared against the benefits of face-to-face meetings. Resistance to working online for some was compounded by difficulties accessing the internet and the lack of adequate electronic devices to do so.

Regarding the modification of protocol requirements, respondents mentioned adding safety procedures for study participants and members of the research teams, facilitating remote documentation of consent, and changing the policies regarding the use of non-anonymized data from health service and public health records for the duration of the pandemic to allow more unrestrained use of data. Some ERCs transitioned from requiring the physical signature of conflict-of-interest declaration forms to an email declaration.

As shown in Table 3 , only a minority of respondents indicated that their ERCs conducted a formal evaluation of the success or failure of modifying existing procedures or policies (28% of participants from HICs and 17% of those from LMICs). More than one quarter of respondents did not know whether such modifications had been assessed.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.t004

Design and implementation of new procedures and policies

Almost two-thirds of respondents from both HICs and LMICs reported that their ERCs had designed and implemented new procedures and policies to address the challenges brought about by the pandemic ( S10 Table in S2 Appendix ). As in the case of modifications to ERC processes, innovations occurred mainly in the areas of meeting logistics and frequency, and of procedures for protocol review and approval ( S11 Table in S2 Appendix ). This was the case for ERCs in both HICs and LMICs.

In their descriptive responses, participants mentioned the development and implementation of new standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the integration of ad hoc committees, some including specialists, for urgent, accelerated protocol review. Such fast-track ERCs could review studies in one or two days, considerably shortening the time to complete reviews. One respondent considered the most successful innovation to be the formation of a “pool” of committee members ready to be convened at very short notice to quickly review COVID-19-related protocols. Such an ad hoc committee enabled applications to be reviewed and turned around very quickly. Of note, survey participants did not explicitly specify in their descriptive responses whether these ad hoc committees were integrated exclusively by existing ERC members, or if external experts and specialists were invited to take part in them. Similarly, respondents did not comment on whether existing SOPs contemplated the creation of ad hoc committees, on the way these entities were governed, or on the modifications made to SOPs to allow the integration of such committees.

The proportion of ERCs that formally evaluated the success or failure of new procedures and policies was analogous to that described for modifications to SOPs. Table 4 shows that just 37% of respondents from HICs and 21% of those from LMICs reported that their ERCs conducted such an evaluation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.t005

Permanently putting into effect modifications and innovations

A substantial majority of respondents (almost three quarters of those from HICs and more than four-fifths of those from LMICs) stated that many of the modifications and innovations to operating procedures implemented during the pandemic should be permanently put into effect ( S12 Table in S2 Appendix ), particularly in the areas of meeting logistics and frequency, procedures for protocol review and approval, and training of ethics review committee members in new or modified procedures ( S13 Table in S2 Appendix ). Several participants argued in their descriptive responses that virtual online meetings should be a permanent feature of ERC operations, as they increase efficiency and preclude many of the disadvantages of face-to-face meetings. Another recommendation was to enable the integration of ad hoc committees during times of increased demand. Similarly, respondents emphasized the relevance of facilitating the incorporation of new expert members to the ERCs as required. However, 20% of participants from HICs and 50% of those from LMICs indicated that their ERCs had no support to permanently implement modifications or innovations established during the COVID-19 pandemic ( S14 Table in S2 Appendix ).

Policies, procedures, and guidelines for public health emergencies

It is noteworthy that almost half of respondents from HICs and three-quarters of participants from LMICs indicated that their ERCs did not have internal policies, procedures, or guidelines before the pandemic that could orient members regarding the functioning of the committees during PHEs ( S15 Table in S2 Appendix ). Regarding the use of internal guidelines, some ERCs adapted existing documents, while others developed entirely new procedures. In the absence of specific internal guidelines, some SOPs explicitly privileged expedited review during health crises.

In contrast to the widespread absence of internal guidelines, the ERCs of one quarter of respondents from HICs and of almost half of those from LMICs used external guidelines not developed by their committees to govern their operation during the pandemic ( S16 Table in S2 Appendix ). Members of several committees referred to publicly available national and international guidelines. A selection of the most consulted documents appears in Box 2 .

Box 2. National and international external guidelines* that survey respondents reported were used by their ERCs to manage operations during the COVID-19 pandemic

International health organizations.

• Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, & World Health Organization (2016). International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans (Fourth Ed.). Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.56759/rgxl7405

• Pan-American Health Organization (2020). Guidance for ethics oversight of COVID-19 research in response to emerging evidence. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/53021

• Pan-American Health Organization (2020). Guidance and strategies to streamline ethics review and oversight of COVID-19-related research. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52089

• Pan-American Health Organization (2020). Template and operational guidance for the ethics review and oversight of COVID-19-related research. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52086

• Pan-American Health Organization (2022). Catalyzing ethical research in emergencies. Ethics guidance, lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, and pending agenda. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/56139

• Red de América Latina y el Caribe de Comités Nacionales de Bioética—United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2020). Ante las investigaciones biomédicas por la pandemia de enfermedad infecciosa por coronavirus Covid-19. https://redbioetica.com.ar/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Declaracion-RED-ALAC-CNBS-Investigaciones-Covid-19.pdf

• World Health Organization (2016). Guidance for managing ethical issues in infectious disease outbreaks. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250580

• World Health Organization (2020). Key criteria for the ethical acceptability of COVID-19 human challenge studies. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331976

• World Health Organization (2020). Guidance for research ethics committees for rapid review of research during public health emergencies. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332206

• World Health Organization (2020). Ethical standards for research during public health emergencies: distilling existing guidance to support COVID-19 R&D. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331507

Bioethics centres

• Nuffield Council of Bioethics (2020). Ethical considerations in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/assets/pdfs/Ethical-considerations-in-responding-to-the-COVID-19-pandemic.pdf

The Hastings Center: Berlinger N et al . (2020). Ethical Framework for Health Care Institutions Responding to Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to COVID-19. https://www.thehastingscenter.org/ethicalframeworkcovid19/

Scientific publications mentioned by respondents

• Saxena et al. (2019). Ethics preparedness: facilitating ethics review during outbreaks—recommendations from an expert panel. https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-019-0366-x

National guidelines

Resolución 908/2020. Ministerio de Salud de Argentina: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/resoluci%C3%B3n-908-2020-337359/texto

• Normativas da Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/normativas-conep?view=default

• Consejo Nacional de Investigación en Salud de Costa Rica (CONIS) (2020). COMUNICADO 2: Recomendaciones para realizar investigación biomédica durante el periodo de la emergencia sanitaria por COVID-19 en Costa Rica. https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/gestores_en_salud/conis/circulares/comunicado_cec_oac_oic_20082020.pdf

El Salvador

• Comité Nacional de Ética de la Investigación en Salud de El Salvador (2015). Manual de procedimientos operativos estándar para comités de ética de la investigación en salud. https://www.cneis.org.sv/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MANUAL-CNEIS.pdf

• Indian Council of Medical Research (2017). National ethical guidelines for biomedical and health research involving human participants. https://ethics.ncdirindia.org/asset/pdf/ICMR_National_Ethical_Guidelines.pdf

• Indian Council of Medical Research (2020).National guidelines for ethics committees reviewing biomedical & health research during COVID-19 pandemic. https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/EC_Guidance_COVID19_06_05_2020.pdf

• Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (2019). KEMRI SERU guidelines for the conduct of research during the covid-19 pandemic in Kenya. https://www.kemri.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/KEMRI-SERU_GUIDELINES-FOR-THE-CONDUCT-OF-RESEARCH-DURING-THE-COVID_8-June-2020_Final.pdf

Garis Panduan Pengurusan COVID-19 di Malaysia No.5 [COVID-19 Management Guidelines in Malaysia No.5] (2020). Ministry of Health of Malaysia. https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/garis-panduan/garis-panduan-kkm

• Government of Pakistan National COVID Command and Operation Center (NCOC) Guidelines (2020). [No longer available, as NCOC ceased operations on April 1, 2022)]

South Africa

• Department of Health, Republic of South Africa (2015). Ethics in Health Research: Principles, Processes and Structures (2d Ed). https://www.sun.ac.za/english/research-innovation/Research-Development/Documents/Integrity%20and%20Ethics/DoH%202015%20Ethics%20in%20Health%20Research%20-%20Principles,%20Processes%20and%20Structures%202nd%20Ed.pdf

South Korea

• Government of the Republic of Korea (2014). Bioethics and Safety Act (Act No. 12844). https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=33442&type=part&key=36

United Kingdom

• United Kingdom Health Departments / Research Ethics Service (2022). Standard Operating Procedures for Research Ethics Committees (Version 7.6). https://www.hra.nhs.uk/documents/3090/RES_Standard_Operating_Procedures_Version_7.6_September_2022_Final.pdf . [In particular, several respondents from the UK mentioned Section 9 of this document, which addresses expedited review in situations such as public health emergencies.]

• Health Research Authority (2020). https://www.hra.nhs.uk/approvals-amendments/

• Health Research Authority (2020). https://www.hra.nhs.uk/covid-19-research/covid-19-guidance-sponsors-sites-and-researchers/

• Department of Health and Social Care (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19): notification to organisations to share information. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-notification-of-data-controllers-to-share-information

* We defined “external guidelines” as those not developed internally by participants’ ERCs

Changes in workload

Respondents stated that the workload of ERC members increased considerably during the pandemic because of the increase in the number of protocols reviewed and also due to the urgency that the approval of COVID-19-related studies demanded. More than half of participants indicated that the volume of protocols received for review increased, both for studies assigned to delegated / expedited review, and for protocols that underwent full review ( S17 Table in S2 Appendix ). The increase in the volume of protocols had unexpected consequences. For example, in one HIC, the number of applicants who were summoned to discuss their protocols with ERCs in online meetings increased proportionally to the escalation in the volume of protocols submitted. In another case, ERC members were burdened with additional tasks such as working closely with the investigators of rejected COVID-19 protocols to improve their applications until these could be approved.

In terms of the time it took ERCs to process and approve protocols during the pandemic, participants confirmed in their descriptive responses that the turnaround time for ERC review was markedly shortened, from weeks or even months to just a few days. In general, more than half of survey participants indicated that, before the pandemic, the duration of the review process, from the time of initial submission to full approval, was between three and eight weeks ( S18 Table in S2 Appendix ). In contrast, during the pandemic, this process was substantially reduced to less than two weeks for both delegated / expedited review and full review. However, this decrease was more pronounced in HICs than in LMICs ( S19 Table in S2 Appendix ). Unsurprisingly, the approval of COVID-19-related research protocols was faster than that of non-COVID-19 studies. More than two-thirds of respondents indicated that delegated / expedited review of COVID-19-related protocols took less than five weeks; this was the case for more than half of full reviews. The process was longer in LMICs, though ( S20 Table in S2 Appendix ). Conversely, protocol review was slightly longer for non-COVID-19 studies, except in the case of full reviews in LMICs, which participants reported took between three and more than 12 weeks ( S21 Table in S2 Appendix ).

Presence of external pressure on ERCs

While only 14% of respondents from HICs reported that their ERCs were subjected to different types of external pressure to both approve and reject research protocols, one third of participants from LMICs (34%) faced such a challenge ( S22 Table in S2 Appendix ). The perceived demand mentioned most frequently involved pressures to rush studies through the review process at the expense of proper examination and ethical oversight. This was especially evident in the case of COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. Some participants highlighted their defense of the autonomy of their ERCs in the face of external influences by using, for example, research policies developed and implemented specifically for the pandemic as a tool for transparent decision-making and as a safeguard against external pressures. One ERC successfully resisted government pressure to approve a research protocol related to a domestic PCR test, human trials of locally developed ventilators, and a placebo-controlled vaccine trial proposed despite the existence of six emergency-authorized vaccines and ongoing mass vaccination.

While some respondents acknowledged that entities such as national governments were understandably impatient for preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic measures to combat the pandemic, they still emphasized the need for proper and thorough review of research protocols. One respondent stated that institutional authorities that favoured or sponsored certain studies sought their immediate approval and considered ERCs as inconvenient hindrances to achieve this goal. Several participants described instances in which ERCs, particularly in LMICs, received pressure to approve alternative medicine clinical trials.

Types of COVID-19 protocols reviewed by ERCs

Given the range of challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was interesting to determine the proportion of protocols received by ERCs according to the research area in which they could be classified, namely, diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccines, pharmacovigilance, or other topics such as behavioural research. Our results suggest that between one-half and two-thirds of ERCs received from one to 10 studies in each area ( Table 5 ). In other words, all areas of COVID-19 research were covered in these protocols submitted to ERCs of both HICs and LMICs. However, it must be noted that between one-third and one-half of respondents could not classify the protocols received by their ERCs (perhaps due to not tracking such information).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.t006

Prioritization of protocols for ethics review

Overwhelmingly, and as expected, participants reported that their ERCs considered COVID-19-related protocols urgent and thus prioritized their review and approval over that of others, particularly in terms of expediting the review of these studies and privileging their discussion during committee meetings. More than three quarters of respondents from HICs and almost two-thirds of those from LMICs indicated that their ERCs gave priority to COVID-19-related studies ( S23 Table in S2 Appendix ). In fact, in one case, an ERC stopped reviewing non-COVID-19-related protocols altogether. Some ERCs gave precedence to the review of COVID-19-related studies according to the priorities determined by their national governments. Others were assigned studies by an ad hoc national entity that triaged the research protocols. Interestingly, however, as shown in S23 Table in S2 Appendix , 15% of respondents from HICs and 27% of those from LMICs stated that their ERCs did not give priority to pandemic-related studies.

Furthermore, our results show that almost one-third of respondents from HICs and almost half of those from LMICs indicated that, for their ERCs, the review of some types of COVID-19-related studies took precedence over that of others ( S24 Table in S2 Appendix ). In their descriptive responses, participants explicitly mentioned prioritizing clinical trials, particularly those focused on COVID-19 vaccine development and safety monitoring; studies related to therapeutic agents for the treatment of COVID-19; protocols about diagnostics and prognostic factors; epidemiological studies, including those related to the natural history of COVID-19 and serosurveillance; and research affecting public health policy. In the case of one ERC in a HIC with very low infection rates resulting from successful public health measures, priority was given to vaccine trials and observational research on vaccine monitoring and community incidence.

Membership of ERCs during the pandemic

One of the main challenges that ERCs worldwide faced during the pandemic was making certain that the number and expertise of their members enabled the efficient operation of the committees under such demanding circumstances. Most survey respondents indicated that their ERCs were able to ensure quorum (80% of participants from HICs, but only 60% of those from LMICs); however, one-third of respondents from LMICs stated that quorum in their ERCs was infrequently met ( S25 Table in S2 Appendix ). Two-thirds of participants from HICs and three quarters of those from LMICs reported that their committees had taken measures to ensure continuity of adequate review of research protocols in case existing members became unavailable due to the pandemic ( S26 Table in S2 Appendix ).

ERCs in both HICs and LMICs did invite new members or appointed alternate ones to ensure quorum and inclusion of individuals with appropriate expertise. Yet, consulting expert non-members seems to have been preferred to incorporating individuals to the committee. Only 13% of respondents from HICs and 24% of those from LMICs indicated that their ERCs had added new members to accelerate protocol review during the pandemic ( S27 Table in S2 Appendix ). Similarly, 11% of participants from HICs and 37% of those from LMICs added new members with specific expertise ( S28 Table in S2 Appendix ). In contrast, almost one-third of individuals from HICs, but close to two-thirds of those from LMICs, stated that their committees had consulted expert non-members to address novel areas of research or to provide enhanced scrutiny of research protocols ( S29 Table in S2 Appendix ). In their descriptive responses, participants expressed that, in some cases, ERCs incorporated new members who were available at quick notice and comfortable with the use of online platforms for meetings and protocol review. A similar approach consisted of integrating virtual ad hoc committees solely to review COVID-19-related-protocols. For some ERCs, national legislation complicated getting additional support or adding new members. Another factor complicating the integration of ERCs was that clinical responsibilities of individuals directly in the care of COVID-19 patients soared, hindering their participation in committee meetings. One participant reported that some ERC members could not fulfill their duties in their respective ERCs because they had become highly sought-after “media celebrity” experts.

Survey respondents suggested that it would be worthwhile to assess the psychological and emotional challenges that ERC members faced when having to evaluate protocols using new, unfamiliar procedures under extreme pressure. Also, it is worth reiterating that, according to several participants, many ERC members, particularly older ones, deplored the loss of features common to face-to-face meetings, such as a warmer, more informal and welcoming environment that favoured interpersonal interactions. Other respondents expressed their desire for constructive and supportive feedback and for more appreciative and generous gestures of gratitude for the extraordinary efforts of ERCs. However, a few participants considered that being able to respond in a useful way to a public health crisis as ERC members was in itself very gratifying and validating.

National and international collaboration

While 38.5% of respondents from HICs and 40% of those from LMICs reported the presence of national and international collaboration among ERCs to standardize emergency operations and procedures during the pandemic, almost one-third of participants from HICs were unsure about the existence of such collaboration ( S30 Table in S2 Appendix ). Almost half of respondents from HICs, but more than two-thirds of those from LMICs, indicated that their ERCs did not have strategies to harmonize multiple review processes ( S31 Table in S2 Appendix ). Most participants (55% of those from HICs and 63% of those from LMICs) reported that their ERCs relied on established procedures to recognize and validate research protocol reviews conducted by other committees ( S32 Table in S2 Appendix ). About one half of respondents from HICs, but almost two-thirds of those from LMICs, affirmed that their ERCs collaborated with scientific committees that pre-reviewed or prioritized pandemic-related research protocols ( S33 Table in S2 Appendix ).

Almost 50% of participants from HICs, but little more than a third of those from LMICs, reported the presence of centralized ethics review of research protocols for multicentre studies related to COVID-19 ( S34 Table in S2 Appendix ). Conversely, one-third of respondents from HICs, but more than two-thirds of those from LMICs, stated that their ERCs did not consider the formation of Joint Scientific Advisory Committees, Data Safety Review Committees, Data Access Committees, or a Joint Ethics Review Committee integrated with representatives of ethics committees of all institutions and countries involved in COVID-19-related research ( S35 Table in S2 Appendix ).

In their descriptive responses, participants noted the need for better inter-ERC collaboration and communication at the national and international levels to share successful strategies and avoid effort duplication. A case of very successful national inter-ERC collaboration is worth mentioning. Respondents from one particular LMIC stated that, given the critical and unforeseen absence of the national entity responsible for health research ethics during the pandemic, ERCs throughout the country joined forces to create an ad hoc spontaneous informal national network of all ERC chairs and co-chairs (it also included members of the national drug regulator) to strengthen mutual support, enhance communication among ERCs, identify best practices, and share academic and ethics resources.

ERCs faced considerable challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Demands were placed on them to urgently review an increased volume of protocols while maintaining rigour, all under suboptimal conditions and uncertainty. Yet, our findings suggest ERCs reviewed a greater volume of protocols and did so faster than before the pandemic. Against this backdrop, our results also reveal that, despite billions of dollars having been invested into the research and development (R&D) ecosystem to support the COVID-19 research response, little to no additional resources were directed to ERCs to support or expedite their functions. This should be particularly sobering for those who raise complaints about ERCs being an “obstacle” to research [ 13 – 16 ]. It may also help to explain other challenges experienced by ERCs during the pandemic, such as the absence of internal policies or guidelines for adapting to a PHE, the collateral damage sustained from deprioritizing non-COVID-19 protocols, and the pressures felt to rush protocols through review.

Our finding that ERCs wish to sustain many of the modifications made to their operations during the COVID-19 pandemic should be interpreted in light of the fact that ERCs also report having received little or no support during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as exiguous support for the maintenance of any modifications they would like to make permanent into the future. While it is expected that the research ethics ecosystem learn from this experience and enhance operations for future threats, it is difficult to see how this will be possible without significant investment. While no one seems to disagree that the research ethics ecosystem should strive for greater efficiency and collaboration, especially during PHEs, investments are required to achieve these aims. Simply put, the experience of ERCs during the COVID-19 pandemic, while herculean in many respects, was a function of necessity and is unlikely to be sustainable.

Extant literature reporting the challenges faced by ERCs during the COVID-19 pandemic is scant and tends to be limited to the early phases of this PHE. Most studies published on this topic are confined to single countries or geographical regions, with only one study including 14 countries in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe[ 17 ]. Several of these contributions focus exclusively on one ERC, usually associated with an academic or health care institution. The literature includes descriptions of ERC operations during the pandemic in Central America and the Dominican Republic [ 18 ], China [ 19 ], Ecuador [ 20 ], Egypt [ 21 ], Germany [ 22 ], India [ 23 – 25 ], Iran [ 10 ], Ireland [ 26 ], Kenya [ 27 ], Kyrgyzstan [ 28 ], Latin America [ 29 ], the Netherlands [ 30 ], Pakistan [ 31 ], South Africa [ 32 , 33 ], Turkey [ 34 ], and the United States [ 35 – 37 ]. Most of these studies reported results from surveys, interviews, focus groups, and documentary analysis, including review of research protocols, ERC meeting minutes, and existing SOPs. Participants usually consisted of ERC chairpersons and members, clinical and biomedical researchers, institutional representatives, and laypeople. Most studies based on surveys and interviews included fewer than 30 respondents, with only some having more than 100 participants.

Our findings agree with this literature. Given that our study is truly global in scope, it considerably broadens what is known about the operation of ERCs during the COVID-19 pandemic and clears a path towards greater consensus on strategies to prepare for and respond during future PHEs.

In this literature, several studies emphasize the lack of support and resources to operate during the pandemic. The vast majority of ERCs made numerous modifications to their SOPs. In particular, the use of online platforms for ERC meetings and for protocol review was ubiquitous. However, ERC members across studies pointed out several disadvantages of such platforms, including lack of familiarity and technical know-how, particularly in the case of more senior members of the committees. Only a few institutions provided training, equipment, and technical support for the use of these online platforms. Consistent with our findings, almost no ERCs in these studies reported having internal policies, procedures, or guidelines to operate during a PHE. National regulations on this topic, where available, were often unclear, contradictory, rapidly changing, vague, or difficult to interpret. Conversely, several ERCs availed themselves of international guidelines ( Box 2 ), in particular those prepared by WHO [ 38 – 41 ] and PAHO [ 42 – 45 ].

In terms of changes in workload, all ERCs in the studies mentioned earlier experienced a dramatic increase in the number of COVID-19-related protocols received, which had to be reviewed very quickly in the face of pressure for expedited approvals from researchers, institutions, governments, and the media. The surge in the volume of protocols, along with shortened timelines for turnaround, severely strained ERC members’ ability to conduct rigorous, thorough, high-quality assessments. Despite feeling overwhelmed, ERC members participating in these studies managed to fulfill their responsibilities, sometimes at great personal cost.

Given the urgency to examine and approve an ever-increasing number of COVID-19 research protocols, previous studies report several strategies implemented by ERCs worldwide to prioritize their review. This frequently meant that the assessment of non-COVID-19-related studies was postponed or even abandoned. Similarly, non-interventional COVID-19 protocols were given secondary importance. Prioritization of COVID-19 protocols by type of study was rare.

Despite numerous staffing challenges, most ERCs in the studies examined were able to ensure quorum. In some cases, their institutions provided training sessions to update committee members on the rapidly changing landscape of basic and clinical knowledge about COVID-19. A less frequently used approach was to incorporate new members with relevant expertise into the ERCs. One common strategy across different countries was the integration of ad hoc committees focused exclusively on the review of COVID-19 -related protocols.

The topic of centralized review of pandemic-related research is rather contentious in this literature. While some studies report ERC members favouring such an approach, others consider that a single national ERC in charge of PHE-specific ethics review is bound to be unsuccessful due to the importance of local context in responding to PHEs. In Ecuador, forcing researchers to submit their protocols to a seven-member centralized ad hoc ERC caused considerable delays in the approval process and instead severely impeded the execution of COVID-19-related studies [ 20 ].

As shown in our results, in some countries ERCs strengthened collaboration networks during the pandemic. A notable case was the creation of a spontaneous, informal, ad hoc group in South Africa—the Research Ethics Support in COVID-19 Pandemic (RESCOP)—by ERC chairpersons and members as a response to the lack of national ethics guidance and the unexpected critical absence of the National Health Research Ethics Council at the most crucial moment in the pandemic [ 33 ]. This example highlights the clear need for national governance and oversight for research ethics to ensure accountability and responsiveness of ERCs [ 46 ].

A common topic of concern across ERCs in several countries was the set of unique challenges to obtaining informed consent during the pandemic, especially in the case of patients unable to give consent, such as those who were severely ill, isolated, or in the intensive care unit. Thus, it was necessary to find innovative alternative strategies to obtain consent.

Recommendations

The recommendations presented in Box 3 aim to strengthen the resiliency of ERCs during future public health emergencies. They are based upon our careful analysis of survey responses, and thus articulate, in a way, the concerns and expectations of the participants in our study. These recommendations closely align with the national and international guidelines listed in Box 2 , particularly with those published by WHO.

Box 3. Recommendations to strengthen the resiliency of ERCs during future public health emergencies

• Increase and assign an adequate proportion of the budgets of ethics review committees (ERCs) for:

○ their continued operation during public health emergencies (PHEs), especially in terms of online teleconferencing and review platforms

○ sustaining select modifications and innovations designed and implemented during PHEs

• Increase awareness of the value of ERCs in the research and development (R&D) ecosystem as a means of protecting research participants, ensuring social value, and promoting public trust in research outputs, rather than as a bureaucratic nuisance

• Evaluate the success or failure of modifications and innovations designed and implemented during PHEs

• Develop a “first aid kit” for each ERC that includes:

○ Existing external guidelines for committee operation during a PHE

○ Internal contingency plans designed by the ERC or its home institution that adapt existing external guidelines to local contexts

○ A directory of expert non-members available for consultation

○ Easy-to-follow checklists that incorporate the essential elements needed to function during a PHE

• Familiarize ERC members with the “first aid kit” through periodic capacity building activities

• Consider the psychological and emotional challenges that ERC members face during PHEs

• Devise strategies to defend and safeguard ERCs’ autonomy against external pressures

• Promote national and regional collaboration networks of ERCs that strengthen their resiliency during PHEs

• Facilitate collaboration between ERCs and scientific committees

Limitations and strengths

In terms of the limitations of our study, it would have been desirable to include participants from more countries, and a larger number of respondents from each country. It was probably difficult to reach a higher response rate due to “pandemic fatigue”. Non-native English speakers, especially in LMICs, may have excluded themselves from our survey. Absent or unreliable internet access could have limited the participation of some participants, particularly in LMICs. The number of ERC members that provided ethics review for health care facilities was relatively low. Despite the anonymity of their answers, respondents may have been reluctant to share specific instances of external pressures impinging upon their ERCs. The large number of participants from the UK (93 out of 281) likely skewed the results from HICs, and from experiences in the UK in particular.

We chose to present our results descriptively and did not perform any analytic tests for statistically significant differences in responses. This was because we were unable to determine a denominator, so we could not meet the requirements for many significance tests. Non-parametric tests could have been used, but we think reporting statistical significance in this context would not be informative. Non-response bias could also influence our results. This could be non-differential in its effects as our results cohere with the literature thus far reported.

To our knowledge, this is the first examination at a global level of the challenges faced by ERCs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the strategies used to address them. Also, our study compares for the first time several dimensions of the operation of ERCs during the pandemic between committees in HICs and those in LMICs. All WHO regions were represented in our study, as participants from 48 countries (19 HICs and 29 LMICs) responded to our survey. There was an adequate balance in terms of the sex / gender of respondents. Furthermore, the ample experience of the study participants as ERC members (two thirds of respondents had six or more years of experience in this role) strengthens the generalizability of our findings. The recommendations suggested by the study participants are quite relevant to combating future public health emergencies. In general, all these strengths give credence to the validity, reliability, and accuracy of our results.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. qualtrics questionnaire..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.s001

S2 Appendix. Supplementary tables.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292512.s002

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all the members of ethics review committees from around the world who participated in our survey. We also want to express our gratitude to Andreas Reis and Katherine Littler of the Global Health Ethics and Governance Unit, World Health Organization, and to the following members of the World Health Organization COVID-19 Ethics and Governance Working Group, for their inputs on the survey instrument and manuscript: Aasim Ahmad, Thalia Arawi, Caesar Atuire, Oumou Bah-Sow, Anant Bhan, Ingrid Callies, Angus Dawson, Jean-François Delfraissy, Ezekiel Emanuel, Ruth Faden, Tina Garanis-Papadatos, Prakash Ghimire, Dirceu Greco, Calvin Ho, Patrik Hummel, Zubairu Iliyasu, Mohga Kamal-Yanni, Sharon Kaur, So Yoon Kim, Sonali Kochhar, Ruipeng Lei, Ahmed Mandil, Julian März, Ignacio Mastroleo, Roli Mathur, Signe Mežinska, Ryoko Miyazaki-Krause, Keymanthri Moodley, Suerie Moon, Michael Parker, Carla Saenz, G. Owen Schaefer, Ehsan Shamsi-Gooshki, Jerome Singh, Beatriz Thomé, Teck Chuan Voo, Jonathan Wolff, and Xiaomei Zhai.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, World Health Organization. International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans. Fourth Ed. Geneva: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences; 2016.

- 13. Schneider CE. The Censor’s Hand: The Misregulation of Human-Subject Research. 1st edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press; 2015.

- 38. World Health Organization. Guidance for managing ethical issues in infectious disease outbreaks. Geneva; 2016. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250580 .

- 46. World Health Organization. WHO tool for benchmarking ethics oversight of health-related research with human participants (Draft). Geneva; 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-tool-for-benchmarking-ethics-oversight-of-health-related-research-with-human-participants .

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

Ethics review of big data research: What should stay and what should be reformed?

- Agata Ferretti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6716-5713 1 ,

- Marcello Ienca 1 ,

- Mark Sheehan 2 ,

- Alessandro Blasimme 1 ,

- Edward S. Dove 3 ,

- Bobbie Farsides 4 ,

- Phoebe Friesen 5 ,

- Jeff Kahn 6 ,

- Walter Karlen 7 ,

- Peter Kleist 8 ,

- S. Matthew Liao 9 ,

- Camille Nebeker 10 ,

- Gabrielle Samuel 11 ,

- Mahsa Shabani 12 ,

- Minerva Rivas Velarde 13 &

- Effy Vayena 1

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 51 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

39 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

Ethics review is the process of assessing the ethics of research involving humans. The Ethics Review Committee (ERC) is the key oversight mechanism designated to ensure ethics review. Whether or not this governance mechanism is still fit for purpose in the data-driven research context remains a debated issue among research ethics experts.

In this article, we seek to address this issue in a twofold manner. First, we review the strengths and weaknesses of ERCs in ensuring ethical oversight. Second, we map these strengths and weaknesses onto specific challenges raised by big data research. We distinguish two categories of potential weakness. The first category concerns persistent weaknesses, i.e., those which are not specific to big data research, but may be exacerbated by it. The second category concerns novel weaknesses, i.e., those which are created by and inherent to big data projects. Within this second category, we further distinguish between purview weaknesses related to the ERC’s scope (e.g., how big data projects may evade ERC review) and functional weaknesses, related to the ERC’s way of operating. Based on this analysis, we propose reforms aimed at improving the oversight capacity of ERCs in the era of big data science.

Conclusions

We believe the oversight mechanism could benefit from these reforms because they will help to overcome data-intensive research challenges and consequently benefit research at large.

Peer Review reports

The debate about the adequacy of the Ethics Review Committee (ERC) as the chief oversight body for big data studies is partly rooted in the historical evolution of the ERC. Particularly relevant is the ERC’s changing response to new methods and technologies in scientific research. ERCs—also known as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Research Ethics Committees (RECs)—came to existence in the 1950s and 1960s [ 1 ]. Their original mission was to protect the interests of human research participants, particularly through an assessment of potential harms to them (e.g., physical pain or psychological distress) and benefits that might accrue from the proposed research. ERCs expanded in scope during the 1970s, from participant protection towards ensuring valuable and ethical human subject research (e.g., having researchers implement an informed consent process), as well as supporting researchers in exploring their queries [ 2 ].

Fast forward fifty years, and a lot has changed. Today, biomedical projects leverage unconventional data sources (e.g., social media), partially inscrutable data analytics tools (e.g., machine learning), and unprecedented volumes of data [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Moreover, the evolution of research practices and new methodologies such as post-hoc data mining have blurred the concept of ‘ human subject’ and elicited a shift towards the concept of data subject —as attested in data protection regulations. [ 6 , 7 ]. With data protection and privacy concerns being in the spotlight of big data research review, language from data protection laws has worked its way into the vocabulary of research ethics. This terminological shift further reveals that big data, together with modern analytic methods used to interpret the data, creates novel dynamics between researchers and participants [ 8 ]. Research data repositories about individuals and aggregates of individuals are considerably expanding in size. Researchers can remotely access and use large volumes of potentially sensitive data without communicating or actively engaging with study participants. Consequently, participants become more vulnerable and subjected to the research itself [ 9 ]. As such, the nature of risk involved in this new form of research changes too. In particular, it moves from the risk of physical or psychological harm towards the risk of informational harm, such as privacy breaches or algorithmic discrimination [ 10 ]. This is the case, for instance, with projects using data collected through web search engines, mobile and smart devices, entertainment websites, and social media platforms. The fact that health-related research is leaving hospital labs and spreading into online space creates novel opportunities for research, but also raises novel challenges for ERCs. For this reason, it is important to re-examine the fit between new data-driven forms of research and existing oversight mechanisms [ 11 ].

The suitability of ERCs in the context of big data research is not merely a theoretical puzzle but also a practical concern resulting from recent developments in data science. In 2014, for example, the so-called ‘emotional contagion study’ received severe criticism for avoiding ethical oversight by an ERC, failing to obtain research consent, violating privacy, inflicting emotional harm, discriminating against data subjects, and placing vulnerable participants (e.g., children and adolescents) at risk [ 12 , 13 ]. In both public and expert opinion [ 14 ], a responsible ERC would have rejected this study because it contravened the research ethics principles of preventing harm (in this case, emotional distress) and adequately informing data subjects. However, the protocol adopted by the researchers was not required to undergo ethics review under US law [ 15 ] for two reasons. First, the data analyzed were considered non-identifiable, and researchers did not engage directly with subjects, exempting the study from ethics review. Second, the study team included both scientists affiliated with a public university (Cornell) and Facebook employees. The affiliation of the researchers is relevant because—in the US and some other countries—privately funded studies are not subject to the same research protections and ethical regulations as publicly funded research [ 16 ]. An additional example is the 2015 case in which the United Kingdom (UK) National Health Service (NHS) shared 1.6 million pieces of identifiable and sensitive data with Google DeepMind. This data transfer from the public to the private party took place legally, without the need for patient consent or ethics review oversight [ 17 ]. These cases demonstrate how researchers can pursue potentially risky big data studies without falling under the ERC’s purview. The limitations of the regulatory framework for research oversight are evident, in both private and public contexts.

The gaps in the ERC’s regulatory process, together with the increased sophistication of research contexts—which now include a variety of actors such as universities, corporations, funding agencies, public institutes, and citizens associations—has led to an increase in the range of oversight bodies. For instance, besides traditional university ethics committees and national oversight committees, funding agencies and national research initiatives have increasingly created internal ethics review boards [ 18 , 19 ]. New participatory models of governance have emerged, largely due to an increase in subjects’ requests to control their own data [ 20 ]. Corporations are creating research ethics committees as well, modelled after the institutional ERC [ 21 ]. In May 2020, for example, Facebook welcomed the first members of its Oversight Board, whose aim is to review the company’s decisions about content moderation [ 22 ]. Whether this increase in oversight models is motivated by the urge to fill the existing regulatory gaps, or whether it is just ‘ethics washing’, is still an open question. However, other types of specialized committees have already found their place alongside ERCs, when research involves international collaboration and data sharing [ 23 ]. Among others, data safety monitoring boards, data access committees, and responsible research and innovation panels serve the purpose of covering research areas left largely unregulated by current oversight [ 24 ].

The data-driven digital transformation challenges the purview and efficacy of ERCs. It also raises fundamental questions concerning the role and scope of ERCs as the oversight body for ethical and methodological soundness in scientific research. Footnote 1 Among these questions, this article will explore whether ERCs are still capable of their intended purpose, given the range of novel (maybe not categorically new, but at least different in practice) issues that have emerged in this type of research. To answer this question, we explore some of the challenges that the ERC oversight approach faces in the context of big data research and review the main strengths and weaknesses of this oversight mechanism. Based on this analysis, we will outline possible solutions to address current weaknesses and improve ethics review in the era of big data science.

Strengths of the ethics review via ERC

Historically, ERCs have enabled cross disciplinary exchange and assessment [ 27 ]. ERC members typically come from different backgrounds and bring their perspectives to the debate; when multi-disciplinarity is achieved, the mixture of expertise provides the conditions for a solid assessment of advantages and risks associated with new research. Committees which include members from a variety of backgrounds are also suited to promote projects from a range of fields, and research that cuts across disciplines [ 28 ]. Within these committees, the reviewers’ expertise can be paired with a specific type of content to be reviewed. This one-to-one match can bring timely and, ideally, useful feedback [ 29 ]. In many countries (e.g., European countries, the United States (US), Canada, Australia), ERCs are explicitly mandated by law to review many forms of research involving human participants; moreover, these laws also describe how such a body should be structured and the purview of its review [ 30 , 31 ]. In principle, ERCs also aim to be representative of society and the research enterprise, including members of the public and minorities, as well as researchers and experts [ 32 ]. And in performing a gatekeeping function to the research enterprise, ERCs play an important role: they recognize that both experts and lay people should have a say, with different views to contribute [ 33 ].

Furthermore, the ERC model strives to ensure independent assessment. The fact that ERCs assess projects “from the outside” and maintain a certain degree of objectivity towards what they are reviewing, reduces the risk of overlooking research issues and decreases the risk for conflicts of interest. Moreover, being institutionally distinct—for example, being established by an organization that is distinct from the researcher or the research sponsor—brings added value to the research itself as this lessens the risk for conflict of interest. Conflict of interest is a serious issue in research ethics because it can compromise the judgment of reviewers. Institutionalized review committees might particularly suffer from political interference. This is the case, for example, for universities and health care systems (like the NHS), which tend to engage “in house” experts as ethics boards members. However, ERCs that can prove themselves independent are considered more trustworthy by the general public and data subjects; it is reassuring to know that an independent committee is overseeing research projects [ 34 ].

The ex-ante (or pre-emptive) ethical evaluation of research studies is by many considered the standard procedural approach of ERCs [ 35 ]. Though the literature is divided on the usefulness and added value provided by this form of review [ 36 , 37 ], ex-ante review is commonly used as a mechanism to ensure the ethical validity of a study design before the research is conducted [ 38 , 39 ]. Early research scrutiny aims at risk-mitigation: the ERC evaluates potential research risks and benefits, in order to protect participants’ physical and psychological well-being, dignity, and data privacy. This practice saves researchers’ resources and valuable time by preventing the pursuit of unethical or illegal paths [ 40 ]. Finally, the ex-ante ethical assessment gives researchers an opportunity to receive feedback from ERCs, whose competence and experience may improve the research quality and increase public trust in the research [ 41 ].

All strengths mentioned in this section are strengths of the ERC model in principle. In practice, there are many ERCs that are not appropriately interdisciplinary or representative of the population and minorities, that lack independence from the research being reviewed, and that fail to improve research quality, and may in fact hinder it. We now turn to consider some of these weaknesses in more detail.

Weaknesses of the ethics review via ERC

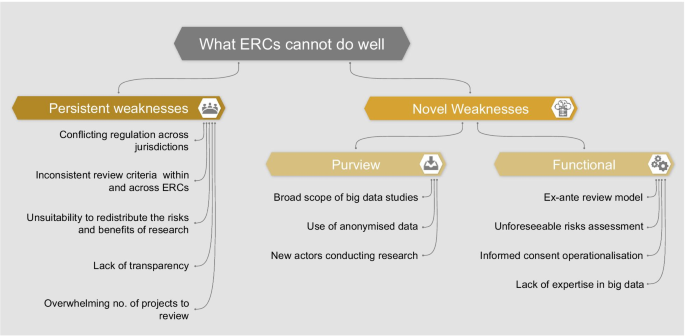

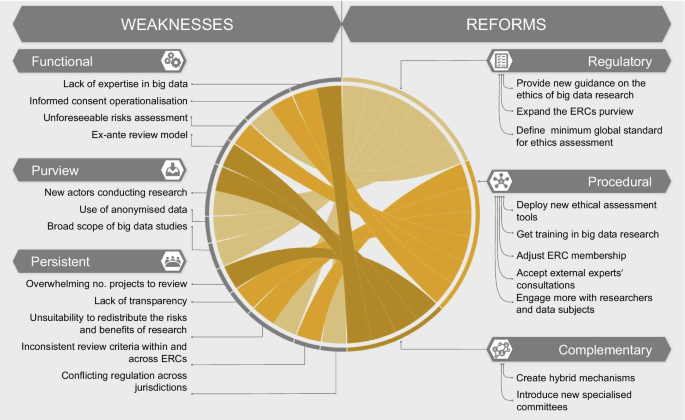

In order to assess whether ERCs are adequately equipped to oversee big data research, we must consider the weaknesses of this model. We identify two categories of weaknesses which are described in the following section and summarized in Fig. 1 :

Persistent weaknesses : those existing in the current oversight system, which could be exacerbated by big data research

Novel weaknesses : those brought about by and specific to the nature of big data projects

Within this second category of novel weaknesses, we further differentiate between:

Purview weaknesses : reasons why some big data projects may bypass the ERCs’ purview

Functional weaknesses : reasons why some ERCs may be inadequate to assess big data projects specifically

Weaknesses of the ERCs

We base the conceptual distinction between persistent and novel weaknesses on the fact that big data research diverges from traditional biomedical research in many respects. As previously mentioned, big data projects are often broad in scope, involve new actors, use unprecedented methodologies to analyze data, and require specific expertise. Furthermore, the peculiarities of big data itself (e.g., being large in volume and from a variety of sources) make data-driven research different in practice from traditional research. However, we should not consider the category of “novel weaknesses” a closed category. We do not argue that weaknesses mentioned here do not, at least partially, overlap with others which already exist. In fact, in almost all cases of ‘novelty’, (i) there is some link back to a concept from traditional research ethics, and (ii) some thought has been given to the issue outside of a big data or biomedical context (e.g., the problem of ERCs’ expertise has arisen in other fields [ 42 ]). We believe that by creating conceptual clarity about novel oversight challenges presented by big data research, we can begin to identify tailored reforms.

Persistent weaknesses

As regulation for research oversight varies between countries, ERCs often suffer from a lack of harmonization. This weakness in the current oversight mechanism is compounded by big data research, which often relies on multi-center international consortia. These consortia in turn depend on approval by multiple oversight bodies demanding different types of scrutiny [ 43 ]. Furthermore, big data research may give rise to collaborations between public bodies, universities, corporations, foundations, and citizen science cooperatives. In this network, each stakeholder has different priorities and depends upon its own rules for regulation of the research process [ 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Indeed, this expansion of regulatory bodies and aims does not come with a coordinated effort towards agreed-upon review protocols [ 47 ]. The lack of harmonization is perpetuated by academic journals and funding bodies with diverging views on the ethics of big data. If the review bodies which constitute the “ethics ecosystem” [ 19 ] do not agree to the same ethics review requirements, a big data project deemed acceptable by an ERC in one country may be rejected by another ERC, within or beyond the national borders.

In addition, there is inconsistency in the assessment criteria used within and across committees. Researchers report subjective bias in the evaluation methodology of ERCs, as well as variations in ERC judgements which are not based on morally relevant contextual considerations [ 48 , 49 ]. Some authors have argued that the probability of research acceptance among experts increases if some research peer or same-field expert sits on the evaluation committee [ 50 , 51 ]. The judgement of an ERC can also be influenced by the boundaries of the scientific knowledge of its members. These boundaries can impact the ERC’s approach towards risk taking in unexplored fields of research [ 52 ]. Big data research might worsen this problem since the field is relatively new, with no standardized metric to assess risk within and across countries [ 53 ]. The committees do not necessarily communicate with each other to clarify their specific role in the review process, or try to streamline their approach to the assessment. This results in unclear oversight mandates and inconsistent ethical evaluations [ 27 , 54 ].