Qualitative case study data analysis: an example from practice

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, National University of Ireland, Galway, Republic of Ireland.

- PMID: 25976531

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.22.5.8.e1307

Aim: To illustrate an approach to data analysis in qualitative case study methodology.

Background: There is often little detail in case study research about how data were analysed. However, it is important that comprehensive analysis procedures are used because there are often large sets of data from multiple sources of evidence. Furthermore, the ability to describe in detail how the analysis was conducted ensures rigour in reporting qualitative research.

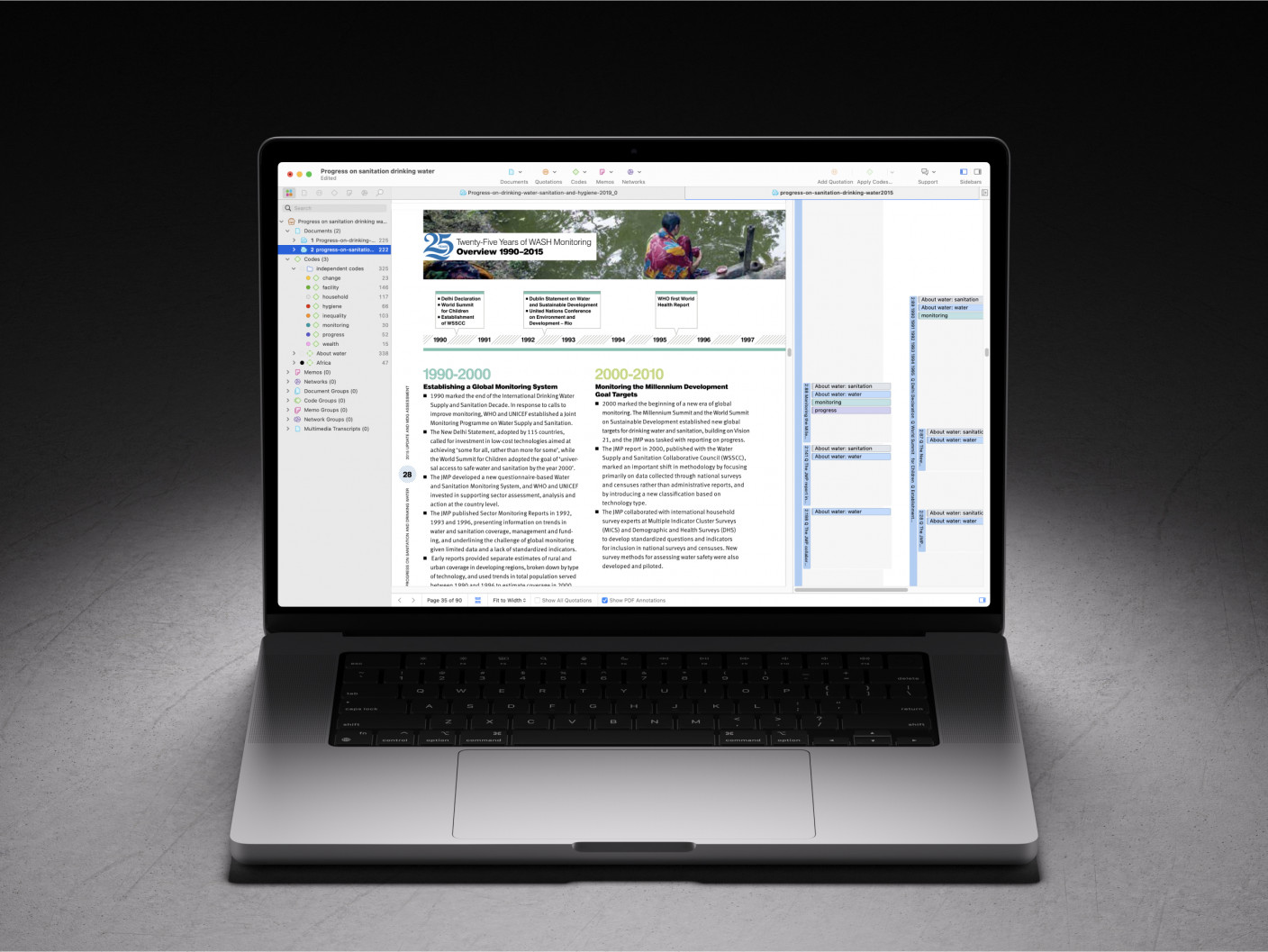

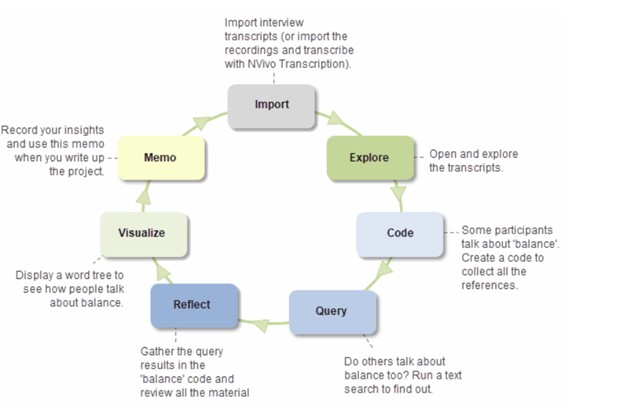

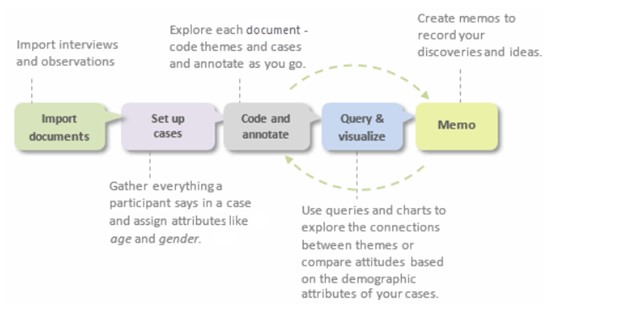

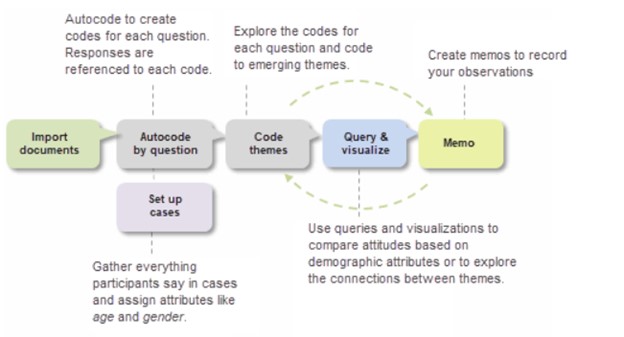

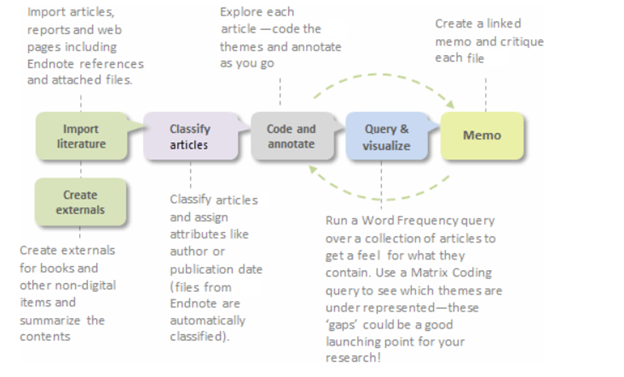

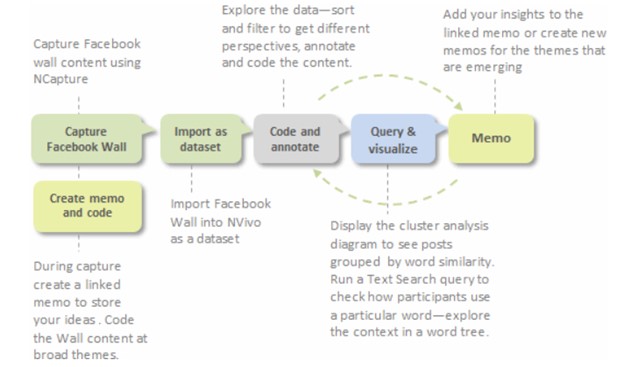

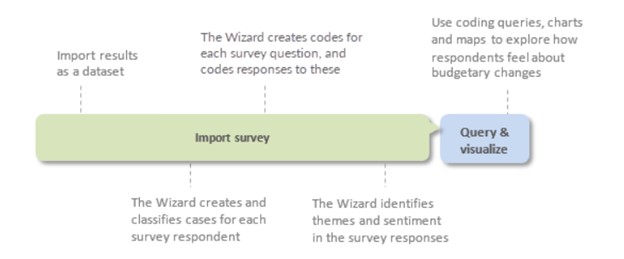

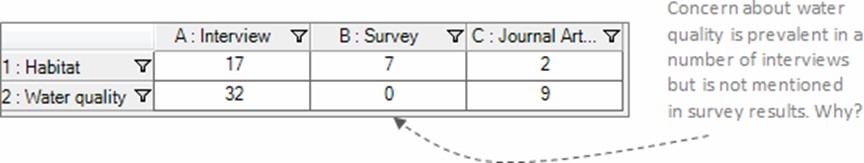

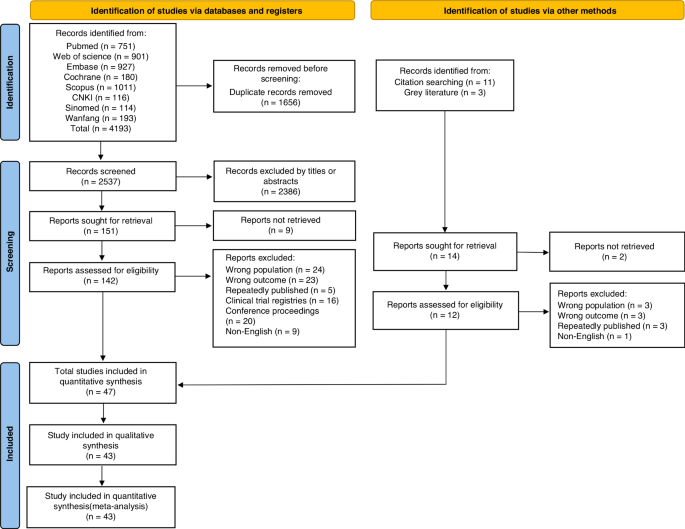

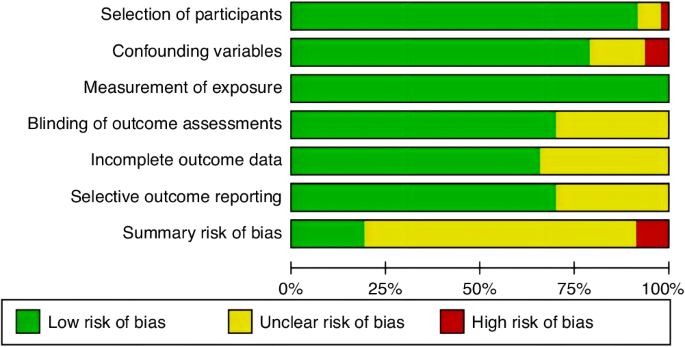

Data sources: The research example used is a multiple case study that explored the role of the clinical skills laboratory in preparing students for the real world of practice. Data analysis was conducted using a framework guided by the four stages of analysis outlined by Morse ( 1994 ): comprehending, synthesising, theorising and recontextualising. The specific strategies for analysis in these stages centred on the work of Miles and Huberman ( 1994 ), which has been successfully used in case study research. The data were managed using NVivo software.

Review methods: Literature examining qualitative data analysis was reviewed and strategies illustrated by the case study example provided. Discussion Each stage of the analysis framework is described with illustration from the research example for the purpose of highlighting the benefits of a systematic approach to handling large data sets from multiple sources.

Conclusion: By providing an example of how each stage of the analysis was conducted, it is hoped that researchers will be able to consider the benefits of such an approach to their own case study analysis.

Implications for research/practice: This paper illustrates specific strategies that can be employed when conducting data analysis in case study research and other qualitative research designs.

Keywords: Case study data analysis; case study research methodology; clinical skills research; qualitative case study methodology; qualitative data analysis; qualitative research.

- Case-Control Studies*

- Data Interpretation, Statistical*

- Nursing Research / methods*

- Qualitative Research*

- Research Design

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- AI & NLP

- Churn & Loyalty

- Customer Experience

- Customer Journeys

- Customer Metrics

- Feedback Analysis

- Product Experience

- Product Updates

- Sentiment Analysis

- Surveys & Feedback Collection

- Try Thematic

Welcome to the community

Qualitative Data Analysis: Step-by-Step Guide (Manual vs. Automatic)

When we conduct qualitative methods of research, need to explain changes in metrics or understand people's opinions, we always turn to qualitative data. Qualitative data is typically generated through:

- Interview transcripts

- Surveys with open-ended questions

- Contact center transcripts

- Texts and documents

- Audio and video recordings

- Observational notes

Compared to quantitative data, which captures structured information, qualitative data is unstructured and has more depth. It can answer our questions, can help formulate hypotheses and build understanding.

It's important to understand the differences between quantitative data & qualitative data . But unfortunately, analyzing qualitative data is difficult. While tools like Excel, Tableau and PowerBI crunch and visualize quantitative data with ease, there are a limited number of mainstream tools for analyzing qualitative data . The majority of qualitative data analysis still happens manually.

That said, there are two new trends that are changing this. First, there are advances in natural language processing (NLP) which is focused on understanding human language. Second, there is an explosion of user-friendly software designed for both researchers and businesses. Both help automate the qualitative data analysis process.

In this post we want to teach you how to conduct a successful qualitative data analysis. There are two primary qualitative data analysis methods; manual & automatic. We will teach you how to conduct the analysis manually, and also, automatically using software solutions powered by NLP. We’ll guide you through the steps to conduct a manual analysis, and look at what is involved and the role technology can play in automating this process.

More businesses are switching to fully-automated analysis of qualitative customer data because it is cheaper, faster, and just as accurate. Primarily, businesses purchase subscriptions to feedback analytics platforms so that they can understand customer pain points and sentiment.

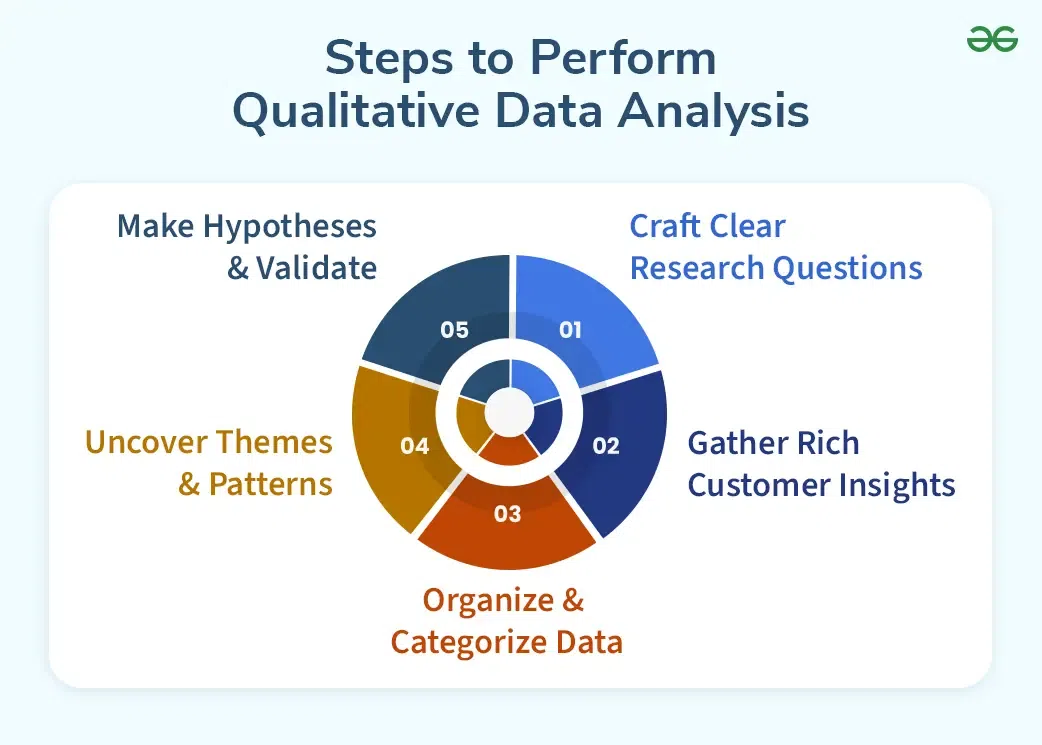

We’ll take you through 5 steps to conduct a successful qualitative data analysis. Within each step we will highlight the key difference between the manual, and automated approach of qualitative researchers. Here's an overview of the steps:

The 5 steps to doing qualitative data analysis

- Gathering and collecting your qualitative data

- Organizing and connecting into your qualitative data

- Coding your qualitative data

- Analyzing the qualitative data for insights

- Reporting on the insights derived from your analysis

What is Qualitative Data Analysis?

Qualitative data analysis is a process of gathering, structuring and interpreting qualitative data to understand what it represents.

Qualitative data is non-numerical and unstructured. Qualitative data generally refers to text, such as open-ended responses to survey questions or user interviews, but also includes audio, photos and video.

Businesses often perform qualitative data analysis on customer feedback. And within this context, qualitative data generally refers to verbatim text data collected from sources such as reviews, complaints, chat messages, support centre interactions, customer interviews, case notes or social media comments.

How is qualitative data analysis different from quantitative data analysis?

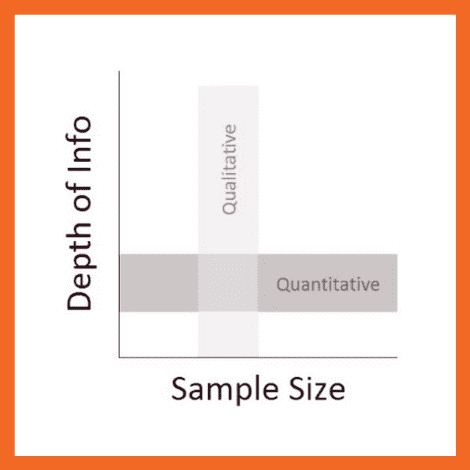

Understanding the differences between quantitative & qualitative data is important. When it comes to analyzing data, Qualitative Data Analysis serves a very different role to Quantitative Data Analysis. But what sets them apart?

Qualitative Data Analysis dives into the stories hidden in non-numerical data such as interviews, open-ended survey answers, or notes from observations. It uncovers the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ giving a deep understanding of people’s experiences and emotions.

Quantitative Data Analysis on the other hand deals with numerical data, using statistics to measure differences, identify preferred options, and pinpoint root causes of issues. It steps back to address questions like "how many" or "what percentage" to offer broad insights we can apply to larger groups.

In short, Qualitative Data Analysis is like a microscope, helping us understand specific detail. Quantitative Data Analysis is like the telescope, giving us a broader perspective. Both are important, working together to decode data for different objectives.

Qualitative Data Analysis methods

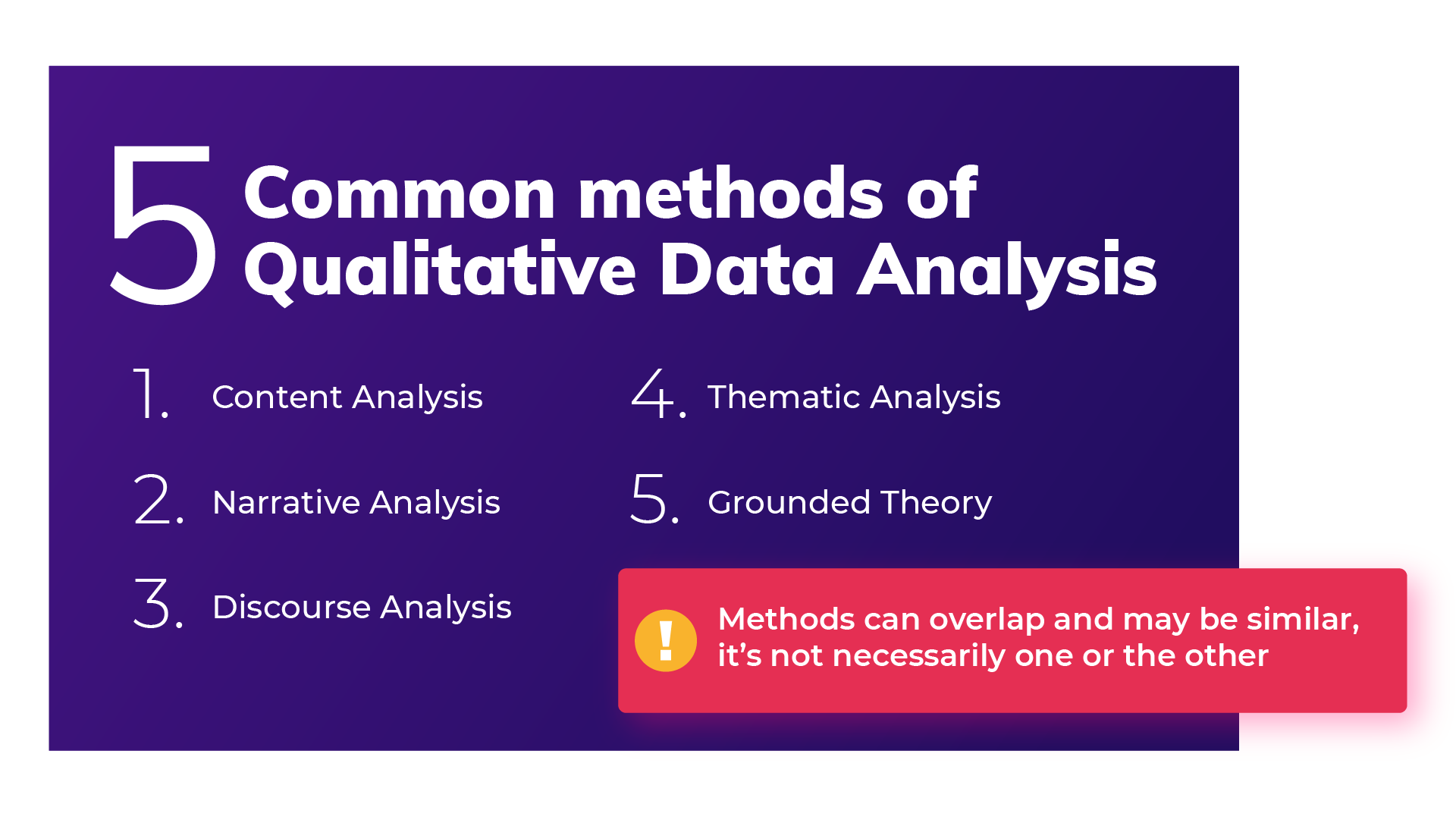

Once all the data has been captured, there are a variety of analysis techniques available and the choice is determined by your specific research objectives and the kind of data you’ve gathered. Common qualitative data analysis methods include:

Content Analysis

This is a popular approach to qualitative data analysis. Other qualitative analysis techniques may fit within the broad scope of content analysis. Thematic analysis is a part of the content analysis. Content analysis is used to identify the patterns that emerge from text, by grouping content into words, concepts, and themes. Content analysis is useful to quantify the relationship between all of the grouped content. The Columbia School of Public Health has a detailed breakdown of content analysis .

Narrative Analysis

Narrative analysis focuses on the stories people tell and the language they use to make sense of them. It is particularly useful in qualitative research methods where customer stories are used to get a deep understanding of customers’ perspectives on a specific issue. A narrative analysis might enable us to summarize the outcomes of a focused case study.

Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis is used to get a thorough understanding of the political, cultural and power dynamics that exist in specific situations. The focus of discourse analysis here is on the way people express themselves in different social contexts. Discourse analysis is commonly used by brand strategists who hope to understand why a group of people feel the way they do about a brand or product.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is used to deduce the meaning behind the words people use. This is accomplished by discovering repeating themes in text. These meaningful themes reveal key insights into data and can be quantified, particularly when paired with sentiment analysis . Often, the outcome of thematic analysis is a code frame that captures themes in terms of codes, also called categories. So the process of thematic analysis is also referred to as “coding”. A common use-case for thematic analysis in companies is analysis of customer feedback.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is a useful approach when little is known about a subject. Grounded theory starts by formulating a theory around a single data case. This means that the theory is “grounded”. Grounded theory analysis is based on actual data, and not entirely speculative. Then additional cases can be examined to see if they are relevant and can add to the original grounded theory.

Challenges of Qualitative Data Analysis

While Qualitative Data Analysis offers rich insights, it comes with its challenges. Each unique QDA method has its unique hurdles. Let’s take a look at the challenges researchers and analysts might face, depending on the chosen method.

- Time and Effort (Narrative Analysis): Narrative analysis, which focuses on personal stories, demands patience. Sifting through lengthy narratives to find meaningful insights can be time-consuming, requires dedicated effort.

- Being Objective (Grounded Theory): Grounded theory, building theories from data, faces the challenges of personal biases. Staying objective while interpreting data is crucial, ensuring conclusions are rooted in the data itself.

- Complexity (Thematic Analysis): Thematic analysis involves identifying themes within data, a process that can be intricate. Categorizing and understanding themes can be complex, especially when each piece of data varies in context and structure. Thematic Analysis software can simplify this process.

- Generalizing Findings (Narrative Analysis): Narrative analysis, dealing with individual stories, makes drawing broad challenging. Extending findings from a single narrative to a broader context requires careful consideration.

- Managing Data (Thematic Analysis): Thematic analysis involves organizing and managing vast amounts of unstructured data, like interview transcripts. Managing this can be a hefty task, requiring effective data management strategies.

- Skill Level (Grounded Theory): Grounded theory demands specific skills to build theories from the ground up. Finding or training analysts with these skills poses a challenge, requiring investment in building expertise.

Benefits of qualitative data analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) is like a versatile toolkit, offering a tailored approach to understanding your data. The benefits it offers are as diverse as the methods. Let’s explore why choosing the right method matters.

- Tailored Methods for Specific Needs: QDA isn't one-size-fits-all. Depending on your research objectives and the type of data at hand, different methods offer unique benefits. If you want emotive customer stories, narrative analysis paints a strong picture. When you want to explain a score, thematic analysis reveals insightful patterns

- Flexibility with Thematic Analysis: thematic analysis is like a chameleon in the toolkit of QDA. It adapts well to different types of data and research objectives, making it a top choice for any qualitative analysis.

- Deeper Understanding, Better Products: QDA helps you dive into people's thoughts and feelings. This deep understanding helps you build products and services that truly matches what people want, ensuring satisfied customers

- Finding the Unexpected: Qualitative data often reveals surprises that we miss in quantitative data. QDA offers us new ideas and perspectives, for insights we might otherwise miss.

- Building Effective Strategies: Insights from QDA are like strategic guides. They help businesses in crafting plans that match people’s desires.

- Creating Genuine Connections: Understanding people’s experiences lets businesses connect on a real level. This genuine connection helps build trust and loyalty, priceless for any business.

How to do Qualitative Data Analysis: 5 steps

Now we are going to show how you can do your own qualitative data analysis. We will guide you through this process step by step. As mentioned earlier, you will learn how to do qualitative data analysis manually , and also automatically using modern qualitative data and thematic analysis software.

To get best value from the analysis process and research process, it’s important to be super clear about the nature and scope of the question that’s being researched. This will help you select the research collection channels that are most likely to help you answer your question.

Depending on if you are a business looking to understand customer sentiment, or an academic surveying a school, your approach to qualitative data analysis will be unique.

Once you’re clear, there’s a sequence to follow. And, though there are differences in the manual and automatic approaches, the process steps are mostly the same.

The use case for our step-by-step guide is a company looking to collect data (customer feedback data), and analyze the customer feedback - in order to improve customer experience. By analyzing the customer feedback the company derives insights about their business and their customers. You can follow these same steps regardless of the nature of your research. Let’s get started.

Step 1: Gather your qualitative data and conduct research (Conduct qualitative research)

The first step of qualitative research is to do data collection. Put simply, data collection is gathering all of your data for analysis. A common situation is when qualitative data is spread across various sources.

Classic methods of gathering qualitative data

Most companies use traditional methods for gathering qualitative data: conducting interviews with research participants, running surveys, and running focus groups. This data is typically stored in documents, CRMs, databases and knowledge bases. It’s important to examine which data is available and needs to be included in your research project, based on its scope.

Using your existing qualitative feedback

As it becomes easier for customers to engage across a range of different channels, companies are gathering increasingly large amounts of both solicited and unsolicited qualitative feedback.

Most organizations have now invested in Voice of Customer programs , support ticketing systems, chatbot and support conversations, emails and even customer Slack chats.

These new channels provide companies with new ways of getting feedback, and also allow the collection of unstructured feedback data at scale.

The great thing about this data is that it contains a wealth of valubale insights and that it’s already there! When you have a new question about user behavior or your customers, you don’t need to create a new research study or set up a focus group. You can find most answers in the data you already have.

Typically, this data is stored in third-party solutions or a central database, but there are ways to export it or connect to a feedback analysis solution through integrations or an API.

Utilize untapped qualitative data channels

There are many online qualitative data sources you may not have considered. For example, you can find useful qualitative data in social media channels like Twitter or Facebook. Online forums, review sites, and online communities such as Discourse or Reddit also contain valuable data about your customers, or research questions.

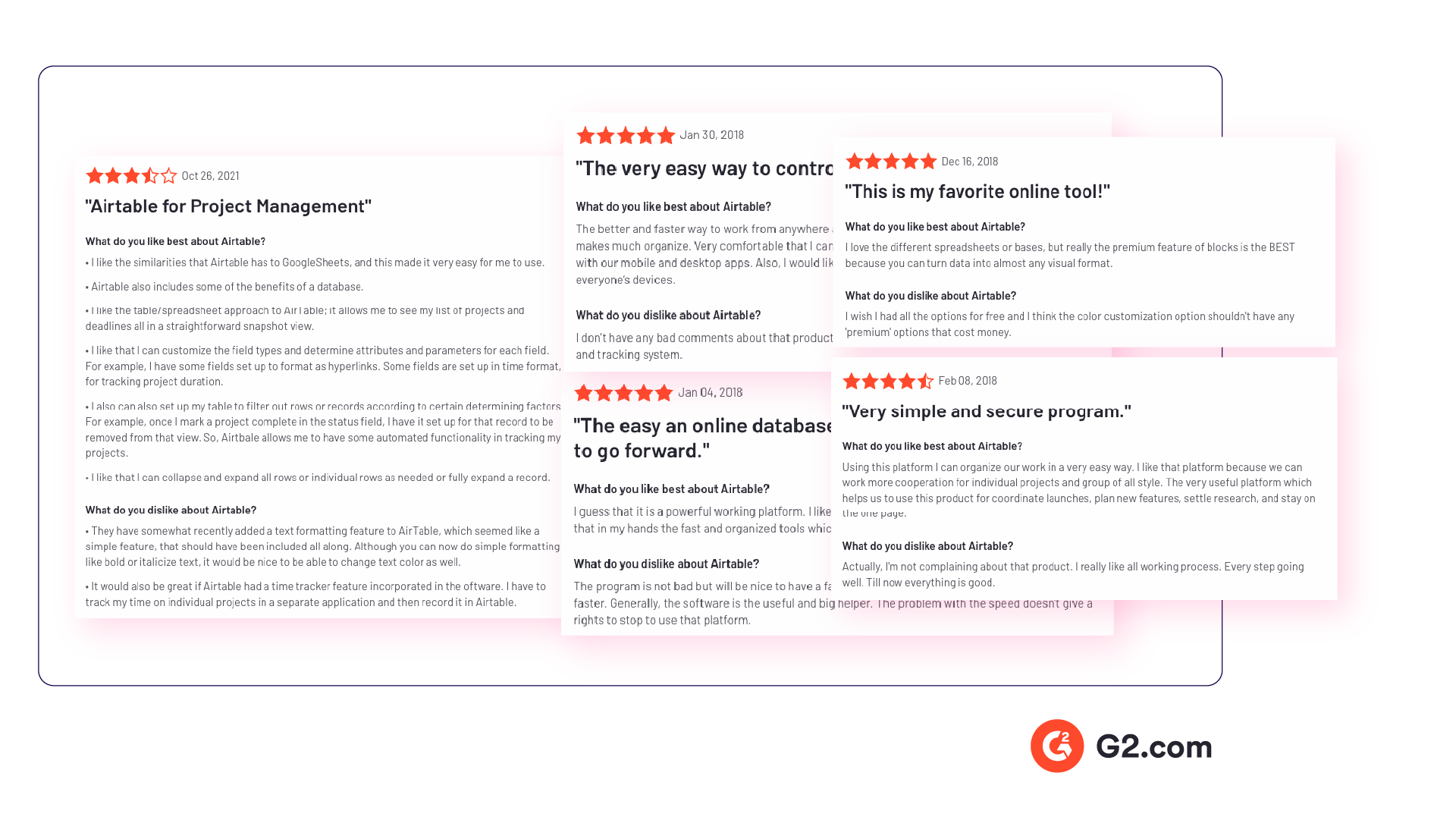

If you are considering performing a qualitative benchmark analysis against competitors - the internet is your best friend. Gathering feedback in competitor reviews on sites like Trustpilot, G2, Capterra, Better Business Bureau or on app stores is a great way to perform a competitor benchmark analysis.

Customer feedback analysis software often has integrations into social media and review sites, or you could use a solution like DataMiner to scrape the reviews.

Step 2: Connect & organize all your qualitative data

Now you all have this qualitative data but there’s a problem, the data is unstructured. Before feedback can be analyzed and assigned any value, it needs to be organized in a single place. Why is this important? Consistency!

If all data is easily accessible in one place and analyzed in a consistent manner, you will have an easier time summarizing and making decisions based on this data.

The manual approach to organizing your data

The classic method of structuring qualitative data is to plot all the raw data you’ve gathered into a spreadsheet.

Typically, research and support teams would share large Excel sheets and different business units would make sense of the qualitative feedback data on their own. Each team collects and organizes the data in a way that best suits them, which means the feedback tends to be kept in separate silos.

An alternative and a more robust solution is to store feedback in a central database, like Snowflake or Amazon Redshift .

Keep in mind that when you organize your data in this way, you are often preparing it to be imported into another software. If you go the route of a database, you would need to use an API to push the feedback into a third-party software.

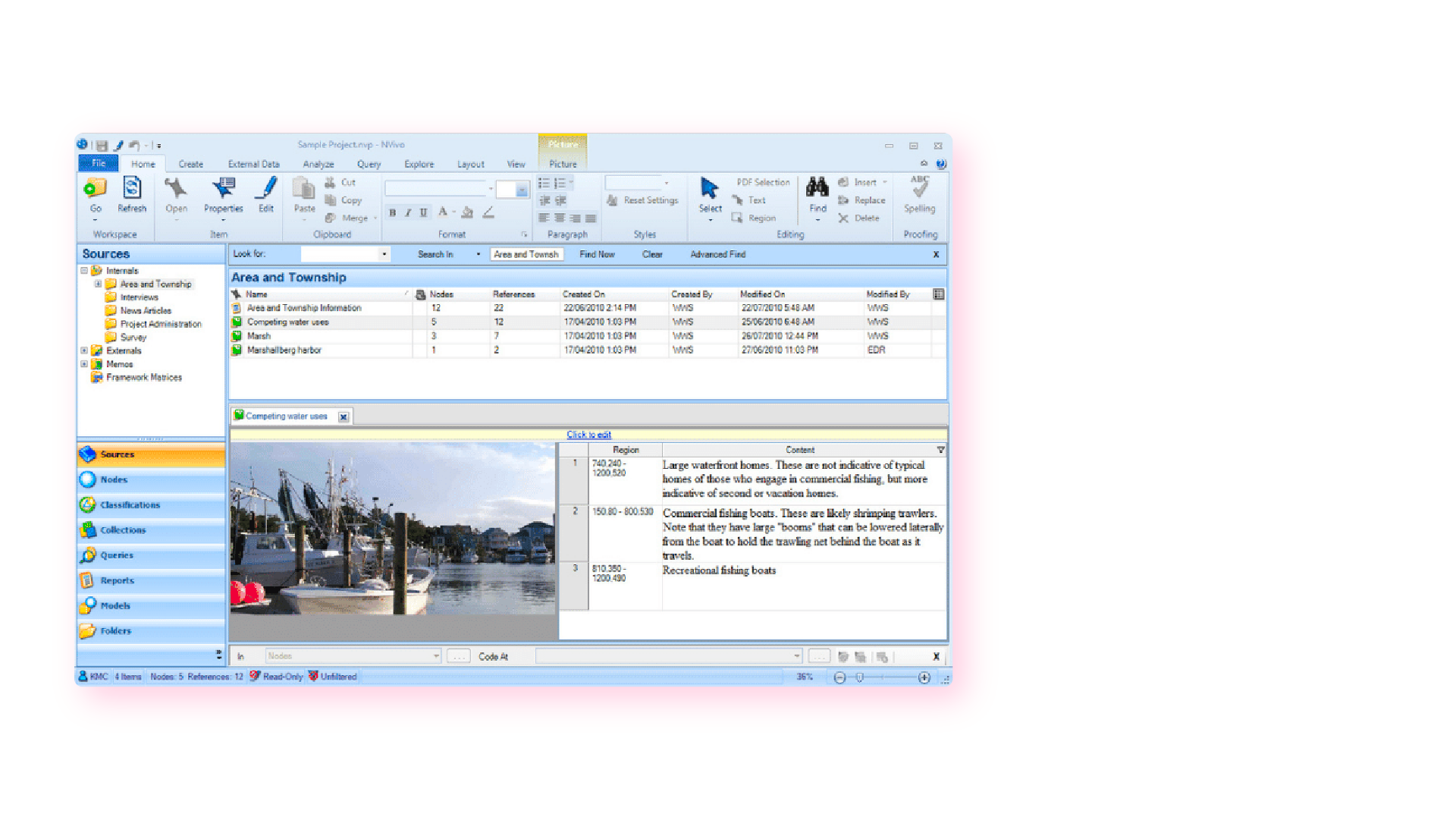

Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS)

Traditionally within the manual analysis approach (but not always), qualitative data is imported into CAQDAS software for coding.

In the early 2000s, CAQDAS software was popularised by developers such as ATLAS.ti, NVivo and MAXQDA and eagerly adopted by researchers to assist with the organizing and coding of data.

The benefits of using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software:

- Assists in the organizing of your data

- Opens you up to exploring different interpretations of your data analysis

- Allows you to share your dataset easier and allows group collaboration (allows for secondary analysis)

However you still need to code the data, uncover the themes and do the analysis yourself. Therefore it is still a manual approach.

Organizing your qualitative data in a feedback repository

Another solution to organizing your qualitative data is to upload it into a feedback repository where it can be unified with your other data , and easily searchable and taggable. There are a number of software solutions that act as a central repository for your qualitative research data. Here are a couple solutions that you could investigate:

- Dovetail: Dovetail is a research repository with a focus on video and audio transcriptions. You can tag your transcriptions within the platform for theme analysis. You can also upload your other qualitative data such as research reports, survey responses, support conversations, and customer interviews. Dovetail acts as a single, searchable repository. And makes it easier to collaborate with other people around your qualitative research.

- EnjoyHQ: EnjoyHQ is another research repository with similar functionality to Dovetail. It boasts a more sophisticated search engine, but it has a higher starting subscription cost.

Organizing your qualitative data in a feedback analytics platform

If you have a lot of qualitative customer or employee feedback, from the likes of customer surveys or employee surveys, you will benefit from a feedback analytics platform. A feedback analytics platform is a software that automates the process of both sentiment analysis and thematic analysis . Companies use the integrations offered by these platforms to directly tap into their qualitative data sources (review sites, social media, survey responses, etc.). The data collected is then organized and analyzed consistently within the platform.

If you have data prepared in a spreadsheet, it can also be imported into feedback analytics platforms.

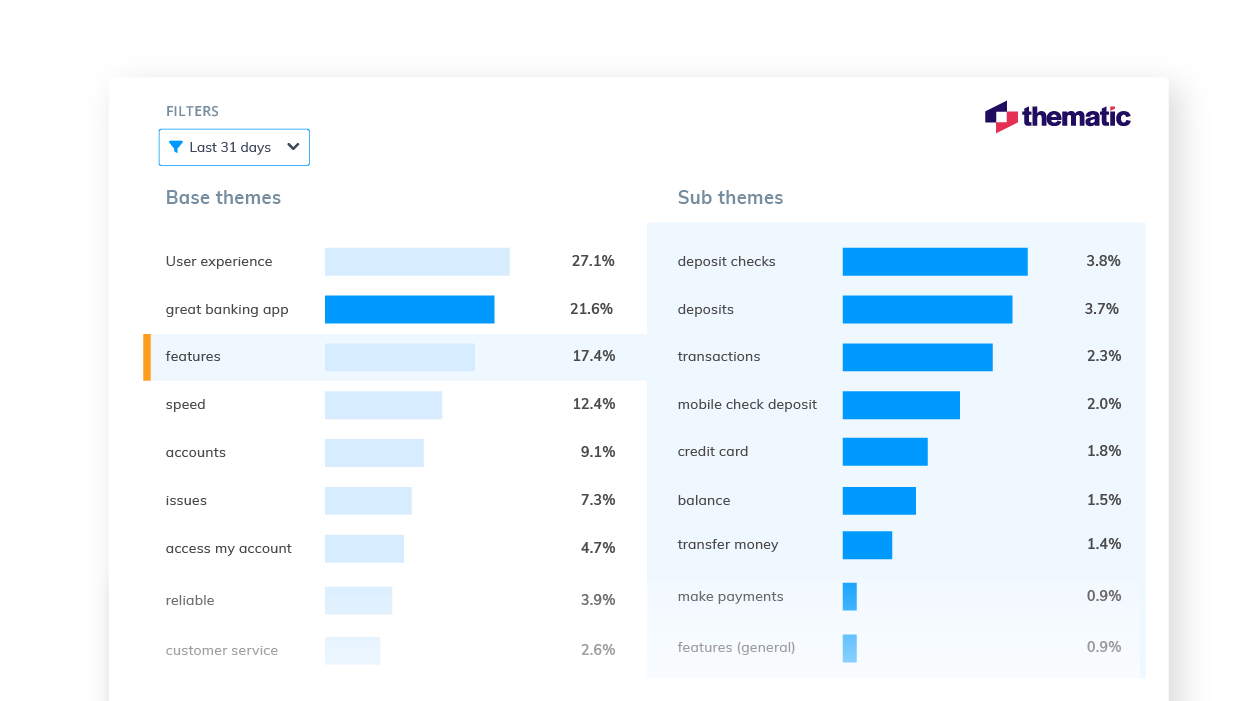

Once all this rich data has been organized within the feedback analytics platform, it is ready to be coded and themed, within the same platform. Thematic is a feedback analytics platform that offers one of the largest libraries of integrations with qualitative data sources.

Step 3: Coding your qualitative data

Your feedback data is now organized in one place. Either within your spreadsheet, CAQDAS, feedback repository or within your feedback analytics platform. The next step is to code your feedback data so we can extract meaningful insights in the next step.

Coding is the process of labelling and organizing your data in such a way that you can then identify themes in the data, and the relationships between these themes.

To simplify the coding process, you will take small samples of your customer feedback data, come up with a set of codes, or categories capturing themes, and label each piece of feedback, systematically, for patterns and meaning. Then you will take a larger sample of data, revising and refining the codes for greater accuracy and consistency as you go.

If you choose to use a feedback analytics platform, much of this process will be automated and accomplished for you.

The terms to describe different categories of meaning (‘theme’, ‘code’, ‘tag’, ‘category’ etc) can be confusing as they are often used interchangeably. For clarity, this article will use the term ‘code’.

To code means to identify key words or phrases and assign them to a category of meaning. “I really hate the customer service of this computer software company” would be coded as “poor customer service”.

How to manually code your qualitative data

- Decide whether you will use deductive or inductive coding. Deductive coding is when you create a list of predefined codes, and then assign them to the qualitative data. Inductive coding is the opposite of this, you create codes based on the data itself. Codes arise directly from the data and you label them as you go. You need to weigh up the pros and cons of each coding method and select the most appropriate.

- Read through the feedback data to get a broad sense of what it reveals. Now it’s time to start assigning your first set of codes to statements and sections of text.

- Keep repeating step 2, adding new codes and revising the code description as often as necessary. Once it has all been coded, go through everything again, to be sure there are no inconsistencies and that nothing has been overlooked.

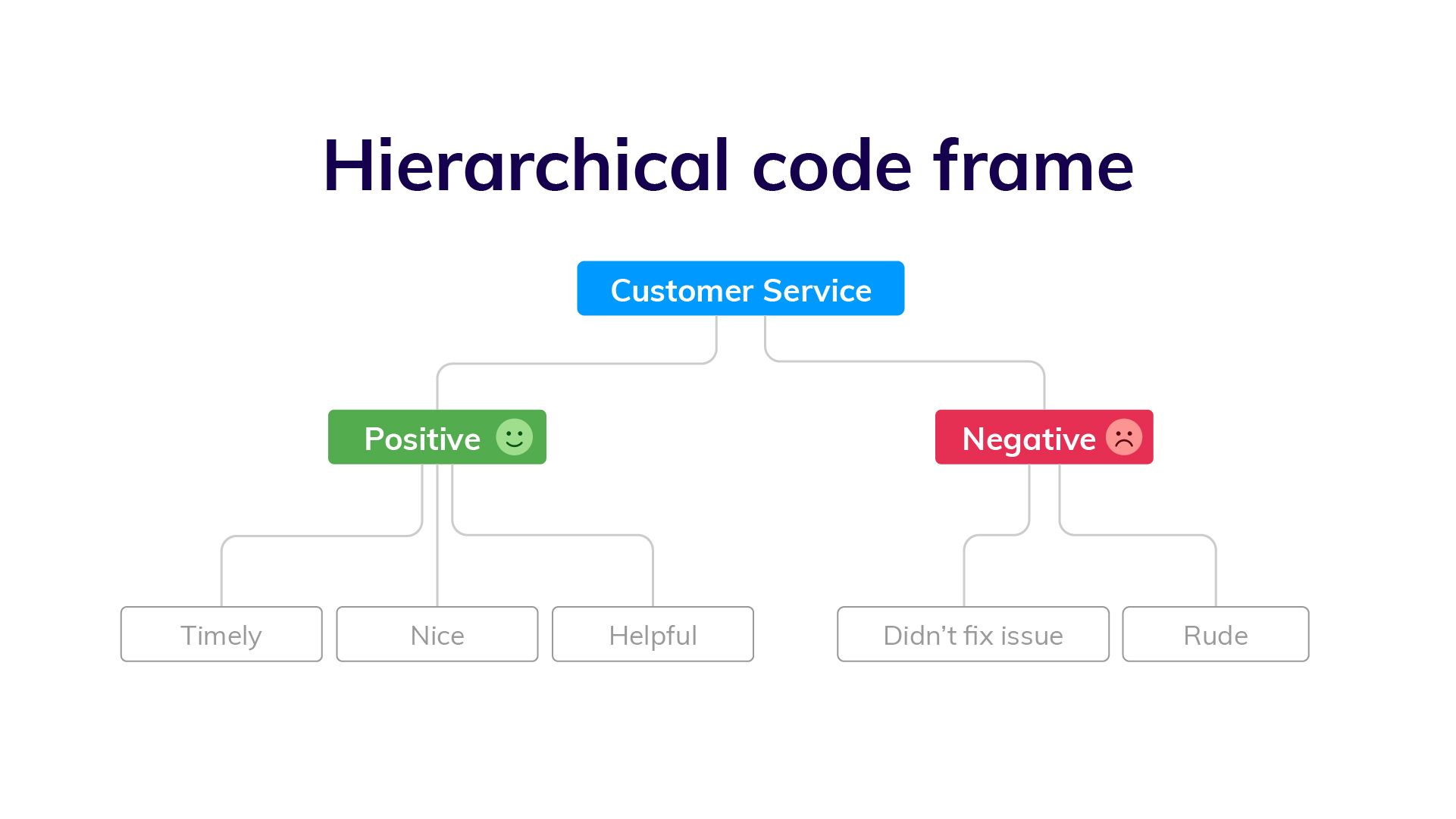

- Create a code frame to group your codes. The coding frame is the organizational structure of all your codes. And there are two commonly used types of coding frames, flat, or hierarchical. A hierarchical code frame will make it easier for you to derive insights from your analysis.

- Based on the number of times a particular code occurs, you can now see the common themes in your feedback data. This is insightful! If ‘bad customer service’ is a common code, it’s time to take action.

We have a detailed guide dedicated to manually coding your qualitative data .

Using software to speed up manual coding of qualitative data

An Excel spreadsheet is still a popular method for coding. But various software solutions can help speed up this process. Here are some examples.

- CAQDAS / NVivo - CAQDAS software has built-in functionality that allows you to code text within their software. You may find the interface the software offers easier for managing codes than a spreadsheet.

- Dovetail/EnjoyHQ - You can tag transcripts and other textual data within these solutions. As they are also repositories you may find it simpler to keep the coding in one platform.

- IBM SPSS - SPSS is a statistical analysis software that may make coding easier than in a spreadsheet.

- Ascribe - Ascribe’s ‘Coder’ is a coding management system. Its user interface will make it easier for you to manage your codes.

Automating the qualitative coding process using thematic analysis software

In solutions which speed up the manual coding process, you still have to come up with valid codes and often apply codes manually to pieces of feedback. But there are also solutions that automate both the discovery and the application of codes.

Advances in machine learning have now made it possible to read, code and structure qualitative data automatically. This type of automated coding is offered by thematic analysis software .

Automation makes it far simpler and faster to code the feedback and group it into themes. By incorporating natural language processing (NLP) into the software, the AI looks across sentences and phrases to identify common themes meaningful statements. Some automated solutions detect repeating patterns and assign codes to them, others make you train the AI by providing examples. You could say that the AI learns the meaning of the feedback on its own.

Thematic automates the coding of qualitative feedback regardless of source. There’s no need to set up themes or categories in advance. Simply upload your data and wait a few minutes. You can also manually edit the codes to further refine their accuracy. Experiments conducted indicate that Thematic’s automated coding is just as accurate as manual coding .

Paired with sentiment analysis and advanced text analytics - these automated solutions become powerful for deriving quality business or research insights.

You could also build your own , if you have the resources!

The key benefits of using an automated coding solution

Automated analysis can often be set up fast and there’s the potential to uncover things that would never have been revealed if you had given the software a prescribed list of themes to look for.

Because the model applies a consistent rule to the data, it captures phrases or statements that a human eye might have missed.

Complete and consistent analysis of customer feedback enables more meaningful findings. Leading us into step 4.

Step 4: Analyze your data: Find meaningful insights

Now we are going to analyze our data to find insights. This is where we start to answer our research questions. Keep in mind that step 4 and step 5 (tell the story) have some overlap . This is because creating visualizations is both part of analysis process and reporting.

The task of uncovering insights is to scour through the codes that emerge from the data and draw meaningful correlations from them. It is also about making sure each insight is distinct and has enough data to support it.

Part of the analysis is to establish how much each code relates to different demographics and customer profiles, and identify whether there’s any relationship between these data points.

Manually create sub-codes to improve the quality of insights

If your code frame only has one level, you may find that your codes are too broad to be able to extract meaningful insights. This is where it is valuable to create sub-codes to your primary codes. This process is sometimes referred to as meta coding.

Note: If you take an inductive coding approach, you can create sub-codes as you are reading through your feedback data and coding it.

While time-consuming, this exercise will improve the quality of your analysis. Here is an example of what sub-codes could look like.

You need to carefully read your qualitative data to create quality sub-codes. But as you can see, the depth of analysis is greatly improved. By calculating the frequency of these sub-codes you can get insight into which customer service problems you can immediately address.

Correlate the frequency of codes to customer segments

Many businesses use customer segmentation . And you may have your own respondent segments that you can apply to your qualitative analysis. Segmentation is the practise of dividing customers or research respondents into subgroups.

Segments can be based on:

- Demographic

- And any other data type that you care to segment by

It is particularly useful to see the occurrence of codes within your segments. If one of your customer segments is considered unimportant to your business, but they are the cause of nearly all customer service complaints, it may be in your best interest to focus attention elsewhere. This is a useful insight!

Manually visualizing coded qualitative data

There are formulas you can use to visualize key insights in your data. The formulas we will suggest are imperative if you are measuring a score alongside your feedback.

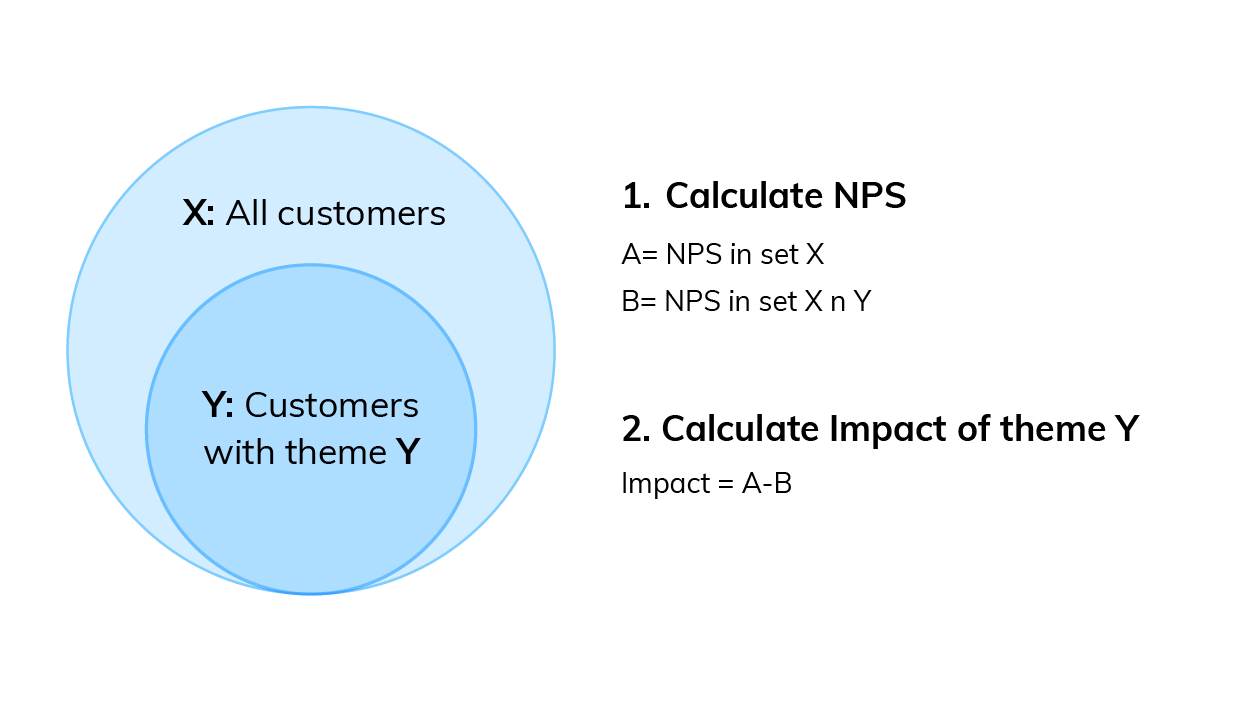

If you are collecting a metric alongside your qualitative data this is a key visualization. Impact answers the question: “What’s the impact of a code on my overall score?”. Using Net Promoter Score (NPS) as an example, first you need to:

- Calculate overall NPS

- Calculate NPS in the subset of responses that do not contain that theme

- Subtract B from A

Then you can use this simple formula to calculate code impact on NPS .

You can then visualize this data using a bar chart.

You can download our CX toolkit - it includes a template to recreate this.

Trends over time

This analysis can help you answer questions like: “Which codes are linked to decreases or increases in my score over time?”

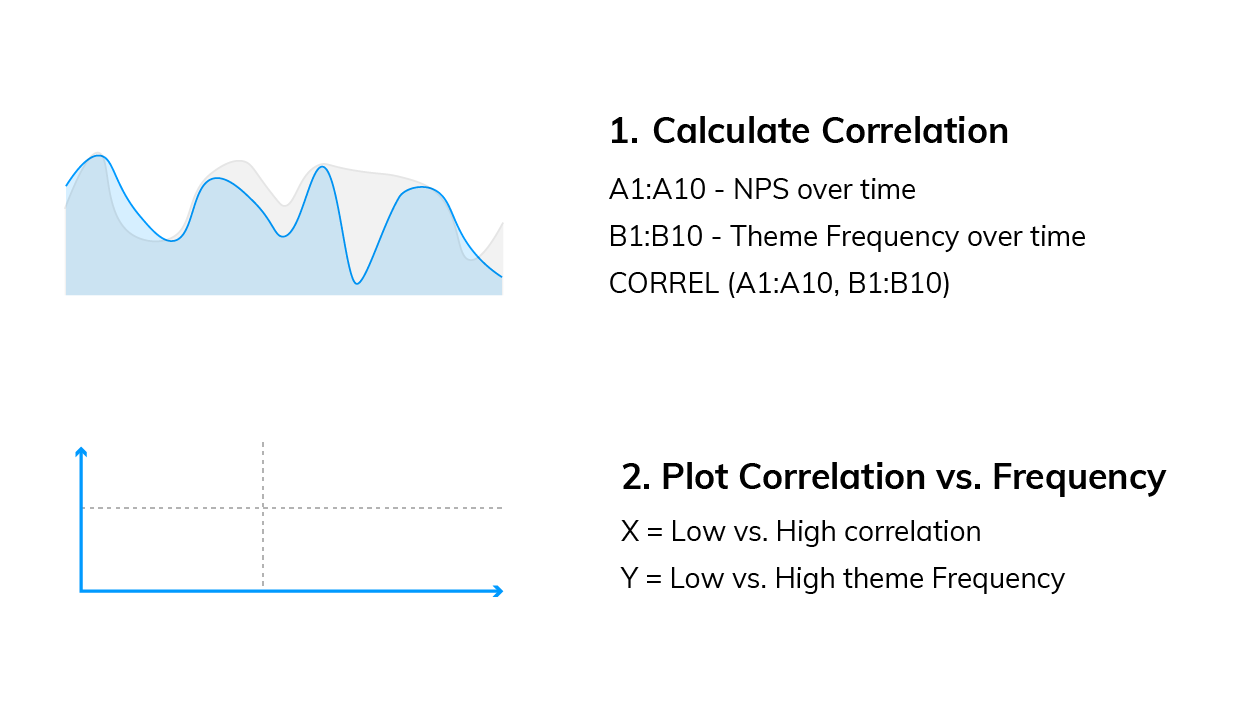

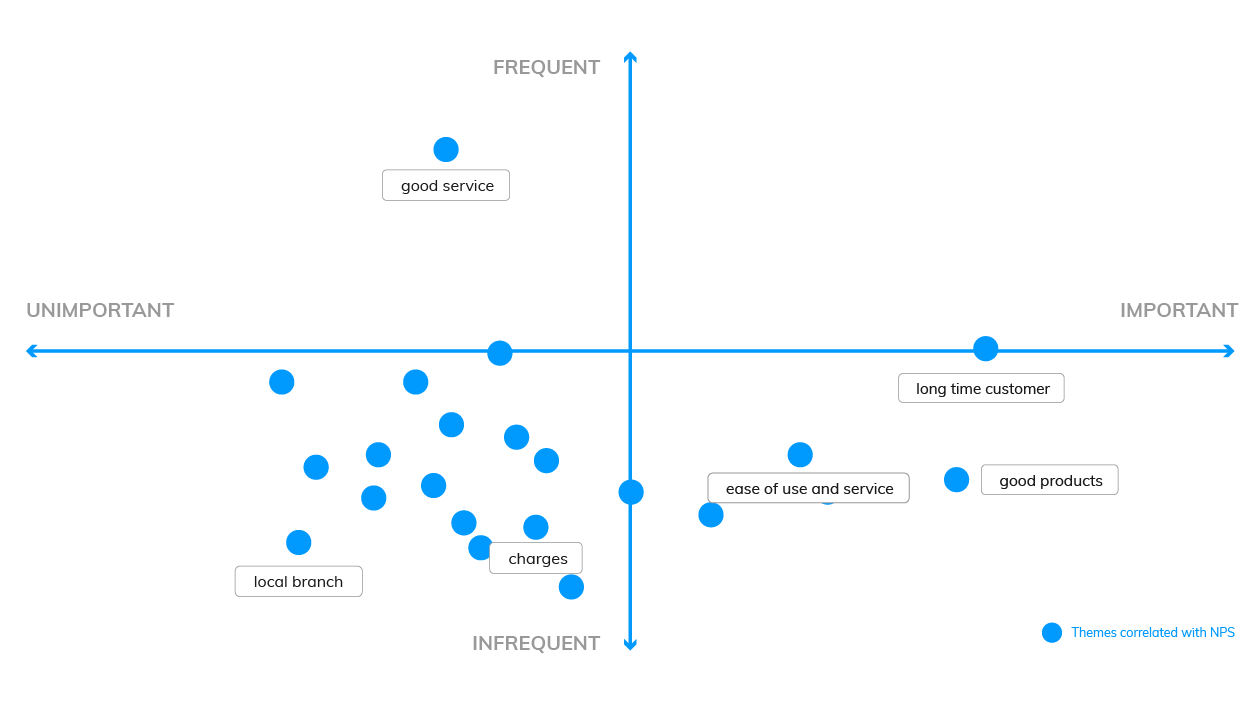

We need to compare two sequences of numbers: NPS over time and code frequency over time . Using Excel, calculate the correlation between the two sequences, which can be either positive (the more codes the higher the NPS, see picture below), or negative (the more codes the lower the NPS).

Now you need to plot code frequency against the absolute value of code correlation with NPS. Here is the formula:

The visualization could look like this:

These are two examples, but there are more. For a third manual formula, and to learn why word clouds are not an insightful form of analysis, read our visualizations article .

Using a text analytics solution to automate analysis

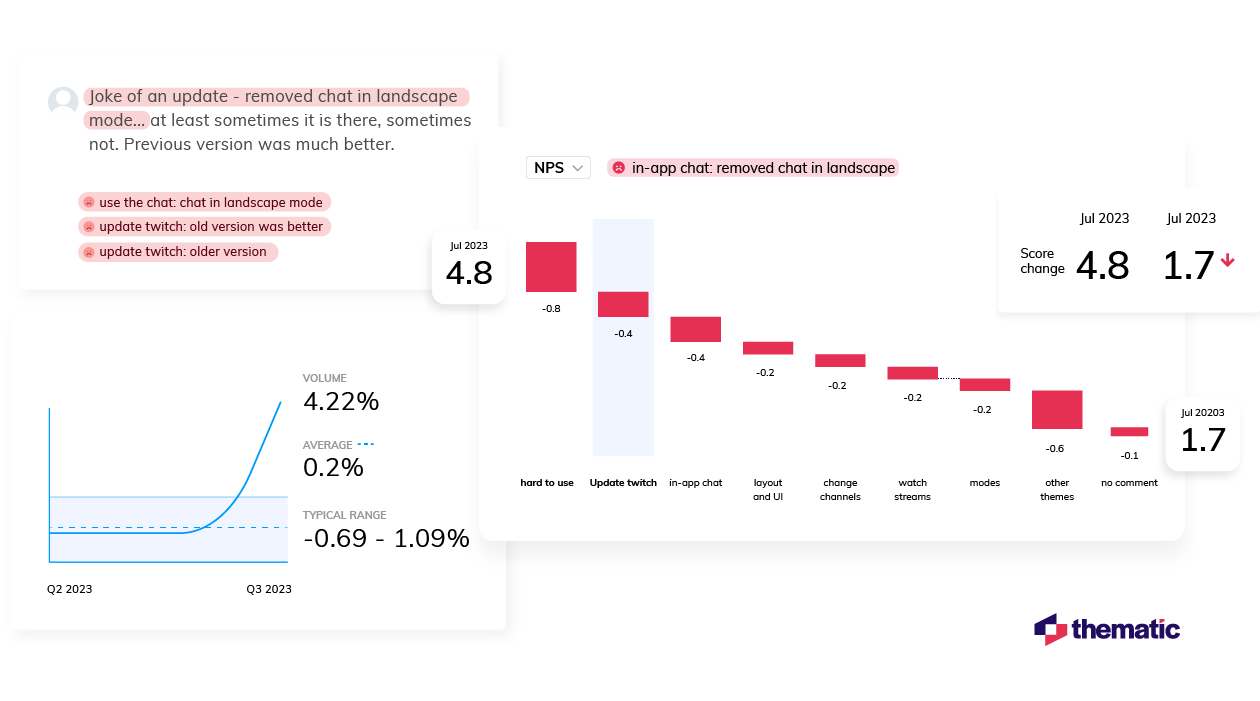

Automated text analytics solutions enable codes and sub-codes to be pulled out of the data automatically. This makes it far faster and easier to identify what’s driving negative or positive results. And to pick up emerging trends and find all manner of rich insights in the data.

Another benefit of AI-driven text analytics software is its built-in capability for sentiment analysis, which provides the emotive context behind your feedback and other qualitative textual data therein.

Thematic provides text analytics that goes further by allowing users to apply their expertise on business context to edit or augment the AI-generated outputs.

Since the move away from manual research is generally about reducing the human element, adding human input to the technology might sound counter-intuitive. However, this is mostly to make sure important business nuances in the feedback aren’t missed during coding. The result is a higher accuracy of analysis. This is sometimes referred to as augmented intelligence .

Step 5: Report on your data: Tell the story

The last step of analyzing your qualitative data is to report on it, to tell the story. At this point, the codes are fully developed and the focus is on communicating the narrative to the audience.

A coherent outline of the qualitative research, the findings and the insights is vital for stakeholders to discuss and debate before they can devise a meaningful course of action.

Creating graphs and reporting in Powerpoint

Typically, qualitative researchers take the tried and tested approach of distilling their report into a series of charts, tables and other visuals which are woven into a narrative for presentation in Powerpoint.

Using visualization software for reporting

With data transformation and APIs, the analyzed data can be shared with data visualisation software, such as Power BI or Tableau , Google Studio or Looker. Power BI and Tableau are among the most preferred options.

Visualizing your insights inside a feedback analytics platform

Feedback analytics platforms, like Thematic, incorporate visualisation tools that intuitively turn key data and insights into graphs. This removes the time consuming work of constructing charts to visually identify patterns and creates more time to focus on building a compelling narrative that highlights the insights, in bite-size chunks, for executive teams to review.

Using a feedback analytics platform with visualization tools means you don’t have to use a separate product for visualizations. You can export graphs into Powerpoints straight from the platforms.

Conclusion - Manual or Automated?

There are those who remain deeply invested in the manual approach - because it’s familiar, because they’re reluctant to spend money and time learning new software, or because they’ve been burned by the overpromises of AI.

For projects that involve small datasets, manual analysis makes sense. For example, if the objective is simply to quantify a simple question like “Do customers prefer X concepts to Y?”. If the findings are being extracted from a small set of focus groups and interviews, sometimes it’s easier to just read them

However, as new generations come into the workplace, it’s technology-driven solutions that feel more comfortable and practical. And the merits are undeniable. Especially if the objective is to go deeper and understand the ‘why’ behind customers’ preference for X or Y. And even more especially if time and money are considerations.

The ability to collect a free flow of qualitative feedback data at the same time as the metric means AI can cost-effectively scan, crunch, score and analyze a ton of feedback from one system in one go. And time-intensive processes like focus groups, or coding, that used to take weeks, can now be completed in a matter of hours or days.

But aside from the ever-present business case to speed things up and keep costs down, there are also powerful research imperatives for automated analysis of qualitative data: namely, accuracy and consistency.

Finding insights hidden in feedback requires consistency, especially in coding. Not to mention catching all the ‘unknown unknowns’ that can skew research findings and steering clear of cognitive bias.

Some say without manual data analysis researchers won’t get an accurate “feel” for the insights. However, the larger data sets are, the harder it is to sort through the feedback and organize feedback that has been pulled from different places. And, the more difficult it is to stay on course, the greater the risk of drawing incorrect, or incomplete, conclusions grows.

Though the process steps for qualitative data analysis have remained pretty much unchanged since psychologist Paul Felix Lazarsfeld paved the path a hundred years ago, the impact digital technology has had on types of qualitative feedback data and the approach to the analysis are profound.

If you want to try an automated feedback analysis solution on your own qualitative data, you can get started with Thematic .

Community & Marketing

Tyler manages our community of CX, insights & analytics professionals. Tyler's goal is to help unite insights professionals around common challenges.

We make it easy to discover the customer and product issues that matter.

Unlock the value of feedback at scale, in one platform. Try it for free now!

- Questions to ask your Feedback Analytics vendor

- How to end customer churn for good

- Scalable analysis of NPS verbatims

- 5 Text analytics approaches

- How to calculate the ROI of CX

Our experts will show you how Thematic works, how to discover pain points and track the ROI of decisions. To access your free trial, book a personal demo today.

Recent posts

When two major storms wreaked havoc on Auckland and Watercare’s infrastructurem the utility went through a CX crisis. With a massive influx of calls to their support center, Thematic helped them get inisghts from this data to forge a new approach to restore services and satisfaction levels.

Become a qualitative theming pro! Creating a perfect code frame is hard, but thematic analysis software makes the process much easier.

Qualtrics is one of the most well-known and powerful Customer Feedback Management platforms. But even so, it has limitations. We recently hosted a live panel where data analysts from two well-known brands shared their experiences with Qualtrics, and how they extended this platform’s capabilities. Below, we’ll share the

Qualitative Data Analysis Methods 101:

The “big 6” methods + examples.

By: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (D.Tech) | May 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Qualitative data analysis methods. Wow, that’s a mouthful.

If you’re new to the world of research, qualitative data analysis can look rather intimidating. So much bulky terminology and so many abstract, fluffy concepts. It certainly can be a minefield!

Don’t worry – in this post, we’ll unpack the most popular analysis methods , one at a time, so that you can approach your analysis with confidence and competence – whether that’s for a dissertation, thesis or really any kind of research project.

What (exactly) is qualitative data analysis?

To understand qualitative data analysis, we need to first understand qualitative data – so let’s step back and ask the question, “what exactly is qualitative data?”.

Qualitative data refers to pretty much any data that’s “not numbers” . In other words, it’s not the stuff you measure using a fixed scale or complex equipment, nor do you analyse it using complex statistics or mathematics.

So, if it’s not numbers, what is it?

Words, you guessed? Well… sometimes , yes. Qualitative data can, and often does, take the form of interview transcripts, documents and open-ended survey responses – but it can also involve the interpretation of images and videos. In other words, qualitative isn’t just limited to text-based data.

So, how’s that different from quantitative data, you ask?

Simply put, qualitative research focuses on words, descriptions, concepts or ideas – while quantitative research focuses on numbers and statistics . Qualitative research investigates the “softer side” of things to explore and describe , while quantitative research focuses on the “hard numbers”, to measure differences between variables and the relationships between them. If you’re keen to learn more about the differences between qual and quant, we’ve got a detailed post over here .

So, qualitative analysis is easier than quantitative, right?

Not quite. In many ways, qualitative data can be challenging and time-consuming to analyse and interpret. At the end of your data collection phase (which itself takes a lot of time), you’ll likely have many pages of text-based data or hours upon hours of audio to work through. You might also have subtle nuances of interactions or discussions that have danced around in your mind, or that you scribbled down in messy field notes. All of this needs to work its way into your analysis.

Making sense of all of this is no small task and you shouldn’t underestimate it. Long story short – qualitative analysis can be a lot of work! Of course, quantitative analysis is no piece of cake either, but it’s important to recognise that qualitative analysis still requires a significant investment in terms of time and effort.

Need a helping hand?

In this post, we’ll explore qualitative data analysis by looking at some of the most common analysis methods we encounter. We’re not going to cover every possible qualitative method and we’re not going to go into heavy detail – we’re just going to give you the big picture. That said, we will of course includes links to loads of extra resources so that you can learn more about whichever analysis method interests you.

Without further delay, let’s get into it.

The “Big 6” Qualitative Analysis Methods

There are many different types of qualitative data analysis, all of which serve different purposes and have unique strengths and weaknesses . We’ll start by outlining the analysis methods and then we’ll dive into the details for each.

The 6 most popular methods (or at least the ones we see at Grad Coach) are:

- Content analysis

- Narrative analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Grounded theory (GT)

- Interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA)

Let’s take a look at each of them…

QDA Method #1: Qualitative Content Analysis

Content analysis is possibly the most common and straightforward QDA method. At the simplest level, content analysis is used to evaluate patterns within a piece of content (for example, words, phrases or images) or across multiple pieces of content or sources of communication. For example, a collection of newspaper articles or political speeches.

With content analysis, you could, for instance, identify the frequency with which an idea is shared or spoken about – like the number of times a Kardashian is mentioned on Twitter. Or you could identify patterns of deeper underlying interpretations – for instance, by identifying phrases or words in tourist pamphlets that highlight India as an ancient country.

Because content analysis can be used in such a wide variety of ways, it’s important to go into your analysis with a very specific question and goal, or you’ll get lost in the fog. With content analysis, you’ll group large amounts of text into codes , summarise these into categories, and possibly even tabulate the data to calculate the frequency of certain concepts or variables. Because of this, content analysis provides a small splash of quantitative thinking within a qualitative method.

Naturally, while content analysis is widely useful, it’s not without its drawbacks . One of the main issues with content analysis is that it can be very time-consuming , as it requires lots of reading and re-reading of the texts. Also, because of its multidimensional focus on both qualitative and quantitative aspects, it is sometimes accused of losing important nuances in communication.

Content analysis also tends to concentrate on a very specific timeline and doesn’t take into account what happened before or after that timeline. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing though – just something to be aware of. So, keep these factors in mind if you’re considering content analysis. Every analysis method has its limitations , so don’t be put off by these – just be aware of them ! If you’re interested in learning more about content analysis, the video below provides a good starting point.

QDA Method #2: Narrative Analysis

As the name suggests, narrative analysis is all about listening to people telling stories and analysing what that means . Since stories serve a functional purpose of helping us make sense of the world, we can gain insights into the ways that people deal with and make sense of reality by analysing their stories and the ways they’re told.

You could, for example, use narrative analysis to explore whether how something is being said is important. For instance, the narrative of a prisoner trying to justify their crime could provide insight into their view of the world and the justice system. Similarly, analysing the ways entrepreneurs talk about the struggles in their careers or cancer patients telling stories of hope could provide powerful insights into their mindsets and perspectives . Simply put, narrative analysis is about paying attention to the stories that people tell – and more importantly, the way they tell them.

Of course, the narrative approach has its weaknesses , too. Sample sizes are generally quite small due to the time-consuming process of capturing narratives. Because of this, along with the multitude of social and lifestyle factors which can influence a subject, narrative analysis can be quite difficult to reproduce in subsequent research. This means that it’s difficult to test the findings of some of this research.

Similarly, researcher bias can have a strong influence on the results here, so you need to be particularly careful about the potential biases you can bring into your analysis when using this method. Nevertheless, narrative analysis is still a very useful qualitative analysis method – just keep these limitations in mind and be careful not to draw broad conclusions . If you’re keen to learn more about narrative analysis, the video below provides a great introduction to this qualitative analysis method.

QDA Method #3: Discourse Analysis

Discourse is simply a fancy word for written or spoken language or debate . So, discourse analysis is all about analysing language within its social context. In other words, analysing language – such as a conversation, a speech, etc – within the culture and society it takes place. For example, you could analyse how a janitor speaks to a CEO, or how politicians speak about terrorism.

To truly understand these conversations or speeches, the culture and history of those involved in the communication are important factors to consider. For example, a janitor might speak more casually with a CEO in a company that emphasises equality among workers. Similarly, a politician might speak more about terrorism if there was a recent terrorist incident in the country.

So, as you can see, by using discourse analysis, you can identify how culture , history or power dynamics (to name a few) have an effect on the way concepts are spoken about. So, if your research aims and objectives involve understanding culture or power dynamics, discourse analysis can be a powerful method.

Because there are many social influences in terms of how we speak to each other, the potential use of discourse analysis is vast . Of course, this also means it’s important to have a very specific research question (or questions) in mind when analysing your data and looking for patterns and themes, or you might land up going down a winding rabbit hole.

Discourse analysis can also be very time-consuming as you need to sample the data to the point of saturation – in other words, until no new information and insights emerge. But this is, of course, part of what makes discourse analysis such a powerful technique. So, keep these factors in mind when considering this QDA method. Again, if you’re keen to learn more, the video below presents a good starting point.

QDA Method #4: Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis looks at patterns of meaning in a data set – for example, a set of interviews or focus group transcripts. But what exactly does that… mean? Well, a thematic analysis takes bodies of data (which are often quite large) and groups them according to similarities – in other words, themes . These themes help us make sense of the content and derive meaning from it.

Let’s take a look at an example.

With thematic analysis, you could analyse 100 online reviews of a popular sushi restaurant to find out what patrons think about the place. By reviewing the data, you would then identify the themes that crop up repeatedly within the data – for example, “fresh ingredients” or “friendly wait staff”.

So, as you can see, thematic analysis can be pretty useful for finding out about people’s experiences , views, and opinions . Therefore, if your research aims and objectives involve understanding people’s experience or view of something, thematic analysis can be a great choice.

Since thematic analysis is a bit of an exploratory process, it’s not unusual for your research questions to develop , or even change as you progress through the analysis. While this is somewhat natural in exploratory research, it can also be seen as a disadvantage as it means that data needs to be re-reviewed each time a research question is adjusted. In other words, thematic analysis can be quite time-consuming – but for a good reason. So, keep this in mind if you choose to use thematic analysis for your project and budget extra time for unexpected adjustments.

QDA Method #5: Grounded theory (GT)

Grounded theory is a powerful qualitative analysis method where the intention is to create a new theory (or theories) using the data at hand, through a series of “ tests ” and “ revisions ”. Strictly speaking, GT is more a research design type than an analysis method, but we’ve included it here as it’s often referred to as a method.

What’s most important with grounded theory is that you go into the analysis with an open mind and let the data speak for itself – rather than dragging existing hypotheses or theories into your analysis. In other words, your analysis must develop from the ground up (hence the name).

Let’s look at an example of GT in action.

Assume you’re interested in developing a theory about what factors influence students to watch a YouTube video about qualitative analysis. Using Grounded theory , you’d start with this general overarching question about the given population (i.e., graduate students). First, you’d approach a small sample – for example, five graduate students in a department at a university. Ideally, this sample would be reasonably representative of the broader population. You’d interview these students to identify what factors lead them to watch the video.

After analysing the interview data, a general pattern could emerge. For example, you might notice that graduate students are more likely to read a post about qualitative methods if they are just starting on their dissertation journey, or if they have an upcoming test about research methods.

From here, you’ll look for another small sample – for example, five more graduate students in a different department – and see whether this pattern holds true for them. If not, you’ll look for commonalities and adapt your theory accordingly. As this process continues, the theory would develop . As we mentioned earlier, what’s important with grounded theory is that the theory develops from the data – not from some preconceived idea.

So, what are the drawbacks of grounded theory? Well, some argue that there’s a tricky circularity to grounded theory. For it to work, in principle, you should know as little as possible regarding the research question and population, so that you reduce the bias in your interpretation. However, in many circumstances, it’s also thought to be unwise to approach a research question without knowledge of the current literature . In other words, it’s a bit of a “chicken or the egg” situation.

Regardless, grounded theory remains a popular (and powerful) option. Naturally, it’s a very useful method when you’re researching a topic that is completely new or has very little existing research about it, as it allows you to start from scratch and work your way from the ground up .

QDA Method #6: Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA)

Interpretive. Phenomenological. Analysis. IPA . Try saying that three times fast…

Let’s just stick with IPA, okay?

IPA is designed to help you understand the personal experiences of a subject (for example, a person or group of people) concerning a major life event, an experience or a situation . This event or experience is the “phenomenon” that makes up the “P” in IPA. Such phenomena may range from relatively common events – such as motherhood, or being involved in a car accident – to those which are extremely rare – for example, someone’s personal experience in a refugee camp. So, IPA is a great choice if your research involves analysing people’s personal experiences of something that happened to them.

It’s important to remember that IPA is subject – centred . In other words, it’s focused on the experiencer . This means that, while you’ll likely use a coding system to identify commonalities, it’s important not to lose the depth of experience or meaning by trying to reduce everything to codes. Also, keep in mind that since your sample size will generally be very small with IPA, you often won’t be able to draw broad conclusions about the generalisability of your findings. But that’s okay as long as it aligns with your research aims and objectives.

Another thing to be aware of with IPA is personal bias . While researcher bias can creep into all forms of research, self-awareness is critically important with IPA, as it can have a major impact on the results. For example, a researcher who was a victim of a crime himself could insert his own feelings of frustration and anger into the way he interprets the experience of someone who was kidnapped. So, if you’re going to undertake IPA, you need to be very self-aware or you could muddy the analysis.

How to choose the right analysis method

In light of all of the qualitative analysis methods we’ve covered so far, you’re probably asking yourself the question, “ How do I choose the right one? ”

Much like all the other methodological decisions you’ll need to make, selecting the right qualitative analysis method largely depends on your research aims, objectives and questions . In other words, the best tool for the job depends on what you’re trying to build. For example:

- Perhaps your research aims to analyse the use of words and what they reveal about the intention of the storyteller and the cultural context of the time.

- Perhaps your research aims to develop an understanding of the unique personal experiences of people that have experienced a certain event, or

- Perhaps your research aims to develop insight regarding the influence of a certain culture on its members.