Volume 20 Supplement 1

Marketing communications in health and medicine: perspectives from Willis-Knighton Health System

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2020

Connecting communities to primary care: a qualitative study on the roles, motivations and lived experiences of community health workers in the Philippines

- Eunice Mallari 1 ,

- Gideon Lasco 2 ,

- Don Jervis Sayman 1 ,

- Arianna Maever L. Amit 1 ,

- Dina Balabanova 3 ,

- Martin McKee 3 ,

- Jhaki Mendoza 1 ,

- Lia Palileo-Villanueva 1 ,

- Alicia Renedo 3 ,

- Maureen Seguin 3 &

- Benjamin Palafox ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3775-4415 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 20 , Article number: 860 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

23 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Community health workers (CHWs) are an important cadre of the primary health care (PHC) workforce in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The Philippines was an early adopter of the CHW model for the delivery of PHC, launching the Barangay (village) Health Worker (BHW) programme in the early 1980s, yet little is known about the factors that motivate and sustain BHWs’ largely voluntary involvement. This study aims to address this gap by examining the lived experiences and roles of BHWs in urban and rural sites in the Philippines.

This cross-sectional qualitative study draws on 23 semi-structured interviews held with BHWs from barangays in Valenzuela City (urban) and Quezon province (rural). A mixed inductive/ deductive approach was taken to generate themes, which were interpreted according to a theoretical framework of community mobilisation to understand how characteristics of the social context in which the BHW programme operates act as facilitators or barriers for community members to volunteer as BHWs.

Interviewees identified a range of motivating factors to seek and sustain their BHW roles, including a variety of financial and non-financial incentives, gaining technical knowledge and skill, improving the health and wellbeing of community members, and increasing one’s social position. Furthermore, ensuring BHWs have adequate support and resources (e.g. allowances, medicine stocks) to execute their duties, and can contribute to decisions on their role in delivering community health services could increase both community participation and the overall impact of the BHW programme.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the importance of the symbolic, material and relational factors that influence community members to participate in CHW programmes. The lessons drawn could help to improve the impact and sustainability of similar programmes in other parts of the Philippines and that are currently being developed or strengthened in other LMICs.

Peer Review reports

Community health workers (CHWs) are an important cadre on the frontline of health systems in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The 1979 Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care (PHC), with its call for both more health workers and greater community participation [ 1 ], paved the way for CHWs to assume a greater range of functions, from health promotion to case management, with growing evidence of their increasing role which they have been shown to execute effectively and with good value for money [ 2 ].

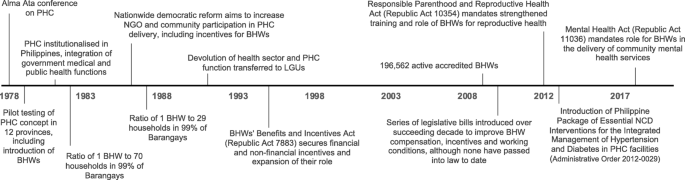

In many parts of the world, CHWs are seen as a means to deliver culturally appropriate health services to the community, serving as liaisons between community members and health care providers [ 3 ]. To achieve this, health systems and programmes typically enlist lay individuals with in-depth understanding of the culture and language of the communities from which they are drawn, with the expectation that they will require only minimal education and in-service training, although this will depend on their scope of work [ 4 ]. In 1981, the Philippines was one of the first countries to implement at scale the Alma Alta recommendation of PHC based on community participation (Fig. 1 ) [ 5 ].

Timeline on the development of the Barangay Health Worker role in the Philippines (1978–2020). This figure illustrates the key events related to the introduction and developing role of Barangay Health Workers in the Philippines, since their introduction in the late 1970s to the present day. BHW Barangay Health Worker; CHW community health worker; LGU local government unit; NCD non-communicable disease; NGO non-governmental organisation; PHC primary health care

Operating at the level of barangays or villages, the smallest unit of governance in the Philippines, volunteer Barangay Health Workers (BHWs) have evolved to become an essential component of the nation’s healthcare workforce [ 6 , 7 , 8 ] and have been key to the success of PHC in the country [ 5 , 8 ]. In recognition of their contribution, the Philippine Congress passed the BHWs’ Benefits and Incentives Act (Republic Act 7883) in 1995 (Fig. 1 ), which is the most recent major reform to the BHW role. The law aimed to empower BHWs to self-organise, to strengthen and systematise their services to communities, and to create a forum for sharing experiences and recommending policies and guidelines [ 9 ]. The law also required local governments to offer benefits and allowances to BHWs, as well as scholarships for their children. The only constraint imposed by the law was that the number of BHWs could not exceed 1% of the community’s population. In practice, however, the number of BHWs, along with the scope of their responsibilities and the size of their allowances, are determined by the budget of the decentralised local government health board covering the barangay to which BHWs are assigned.

BHWs have now existed in the Philippines for almost four decades and have often been commended in evaluations of local health systems and community participation [ 6 , 10 , 11 ]. Yet, we lack a good understanding of what motivates and sustains their involvement on a largely voluntary basis. This understanding is crucial as the programme’s continued success and sustainability relies on its ability to motivate and mobilise community members to act as peer health advocates – and the difficulty of realising such community mobilisation has been noted [ 12 ]. The longevity of the Philippine BHW programme, especially when compared with more recent CHW models elsewhere, provides an excellent case study to explore these topics in depth.

This study aims to address this gap by documenting the experiences and roles of BHWs in selected urban and rural sites in the Philippines. We follow Campbell and Cornish’s approach that draws attention to relational and material aspects of the social context of participation, enhancing understanding of facilitators to community mobilisation to improve health [ 12 ]. This helps identify contextual dimensions often neglected in the literature that undermine or support community members’ motivation to participate in the BHW programme and sustain their involvement over time [ 12 , 13 ]. As many countries are in the process of implementing new CHW programmes or strengthening existing ones, the findings from this study could inform ‘task shifting’ programmes and policies that seek to empower and mobilise communities to take more control over their health by means of CHWs [ 14 ], both in the Philippines and in other LMICs.

This study was conducted as part of the Responsive and Equitable Health Systems-Partnership on Non-Communicable Disease (RESPOND) project, which uses longitudinal mixed-methods to better understand health system barriers to care for hypertension as a tracer condition for non-communicable diseases (NCD) in the Philippines [ 15 ]. The study was conducted in purposefully selected urban barangays in the City of Valenzuela and rural barangays in Quezon province, and data for this analysis was collected via semi-structured interviews with BHWs as part of the facilities assessment component of the RESPOND project.

Data collection and management

A senior in-country, bilingual, social scientist researcher led the data collection and supervised two in-country, bilingual, trained research assistants (one male, one female) with relevant experience and backgrounds in communication and public health in administering semi-structured interviews in pairs in Filipino. A total of 23 BHWs were purposefully recruited, 13 from Valenzuela City and 10 from Quezon province, to maximize diversity of experience in terms of length of service, education and age, across the participating barangays. All BHWs in the study sites were women and those agreeing to participate in the study varied in age from 35 to 75 years. All but one were married. Their lengths of service ranged from 1 to 38 years, with 8 possessing 11 or more years of experience. Two participants reported recently returning to their duties following periods undertaking parental and household duties. The educational background of participants ranged from primary school to undergraduate degree. None received formal training as a health professional prior to starting their roles as BHWs.

The interview guide focused on their motivations for becoming a BHW, their day-to-day experiences of developing their role and responsibilities in the community, and their understanding of hypertension (Supplementary File 1). As BHWs in RESPOND project communities were engaged in the sampling of the household survey component, they were approached directly and oriented to the nature of the BHW study. Written informed consent was acquired from those who wished to participate, and interviews with each were arranged and conducted by the two research assistants in Filipino as the mutually shared language. Because all interviewees were women, it was considered important to include a female and male interviewer who could work flexibly to minimise response bias. Interviews were conducted and audio recorded in a secure place selected by participants between September 2018 and October 2019, lasting 30–60 min. After 15 interviews, data saturation was reached and subsequent interviews were conducted to ensure no new data was generated and to maximise sampling diversity.

Following each interview, written notes were reviewed jointly by the research assistants and BHWs to ensure accurate representation and interpretation. The two research assistants transcribed each interview recording verbatim in Filipino, and the fidelity transcriptions was assessed by the senior researcher against the recording. Anonymised transcripts were produced by removing all personal identifiers and attributes, and participants were assigned a pseudonym, which have been applied throughout this report. Research notes and signed consent forms were stored in locked cabinets accessible only to the research team. All digital audio recordings, digitised research notes, and original and anonymised transcript files were stored separately on secure, encrypted and password protected servers or laptops. All non-anonymised research material (e.g. audio recordings, original transcripts, notes) will be destroyed at project end, while consent forms and anonymised transcripts will be kept securely for 7 years thereafter.

Data analysis and rigour

Verbatim transcriptions in Filipino were analysed using NVivo 12 software [ 16 ]. The senior social scientist led the open reading of the Filipino transcripts and several rounds of coding using a thematic approach [ 17 ] with the research assistants. The coding frame emerged, in part, inductively through multiple, iterative readings of the interview transcripts, but was also informed from our a priori interest in motivations and experiences of BHWs, drawing on Campbell and Cornish’s approach to examining how a “health enabling social environment” affects community mobilisation and participation [ 12 ]. After several rounds of coding, analytical memos of emerging and recurring themes were shared with the broader research team, who have expertise in primary health care, health system strengthening in LMICs and the local context, to conduct interpretation and contextualisation via regular discussions in English, ensuring the relevance and transferability of the results both locally and globally. This also included critical assessments of the findings’ plausibility, consistency with other research of findings, and in light of researchers’ own biases, preconceptions, preferences, and dynamic with the respondent (i.e. researchers were health professionals and/or staff of well-known universities) to ensure validity. Key themes, supporting quotations and statements included in memos (and subsequently in the manuscript) were extracted from interview transcripts and translated to English by the bilingual research assistants; and the quality of translations was assessed by bilingual senior researchers by checking and rechecking transcripts against the translated interpretations [ 18 ].

Informed consent and ethical approval

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the local research ethics board of the University of the Philippines Manila Panel 1. We obtained written informed consent from BHWs prior to the interview, ensuring that their anonymity, privacy and confidentiality would be maintained. BHWs were advised of their right to withdraw their participation at any time, although none of the participating BHWs did so.

In this section, we summarise the lived experiences of community members who volunteer as BHWs in our urban and rural study locations. We also describe the salient themes from these accounts that relate to factors that influenced their initial motivation to volunteer and that determine their continuing involvement.

Becoming a BHW: the role of socio-political positioning and technical knowledge

The social relationships and political positioning of BHWs played an important role in their pathway to participation in the local health system (i.e. recruitment, appointment, and continuing inclusion). Recruitment was largely dependent on having these socio-political connections rather than on having the right skills or technical knowledge to deliver health services. The barangay captain, the leader of the village administration, holds the power to appoint BHWs, and with no formal guidelines to follow, appointments are arbitrary. Some BHWs recalled that they or their peers were appointed by the captain as a result of personal or political relationships, or following a recommendation from other barangay officials, including current BHWs or health staff. Some of the reasons cited for these endorsements included a history of active involvement in barangay activities, such as programmes on feeding, family planning, and fitness. For example, Amy (1 year in service) shared:

I volunteered myself and I said to [the barangay councillor] that if he wins, [allot me a position]. I’ve been applying since before, but I was not given the opportunity. I only volunteer. When he won a seat, I finally got a position at the [health] centre. [The councillor] is my husband’s buddy .

Importantly, however, there need not be any reason for the endorsement other than the prospective BHW’s need for a job, as Ellen (2 years in service) recalled:

My livelihood then was to wash and iron clothes and take to care of children. But when I had a grandchild I could no longer do those tasks, so I asked the barangay treasurer (who happens to be my co-godmother) for any available jobs in the barangay. She told me that they can make me a BHW, so I suddenly became one.

Ellen’s example points to the informality of the application process to become a BHW, something supported by most respondents’ accounts. Cea (11 years in service) recalled that she was interviewed by the local doctor and simply asked (not assessed) about her capacity to work in health centre: “I was interviewed and she asked, ‘Can you do community area activities? Can you do duties in the health centre? Can you do all of this?’” Skills and professional qualification, while useful, are largely secondary to personal connections.

Given that barangay captains are elected every 3 years and their power to appoint (or remove) BHWs, one’s position may not be secure when administrations change. Many BHWs recalled instances when they or their former peers were dismissed because they were not allied politically with the newly elected captain’s party. Luisa (5 years in service) shared that she was dismissed because her religious values did not permit her to vote; while Catherine (6 years in service) recalled that she was dismissed unexpectedly at an earlier point in her career:

We thought that they would not remove anyone, including BHW positions. I was confident. I did not even vote and had no involvement in the political system. After the election on July 1, I went to the barangay office and my name was not included on the list of BHWs.

While a connection to barangay officials appears to be a common route to becoming a BHW, involvement with the wrong politician or non-involvement in politics can also be liability, underscoring the political nature of the position. However, several examples of more merit-based appointments were noted, such as where applicants had previously volunteered for other community activities or programmes (e.g. in the barangay day care centre) or assisted existing BHWs.

Mediating health: bridging and linking community members to services

In general, the activities performed by BHWs involved two roles: serving as frontline health centre staff and acting as community health mobilisers. However, the balance of activities depended on the priorities of the health centre manager to which the BHW was assigned. BHWs were commonly involved in various health centre programmes, including immunisation, maternal care, family planning and hypertension management. Their weekly schedules varied from barangay to barangay, but they typically spent the whole day in health centres 2–3 times a week.

As frontline staff at local health centres, BHWs are often the first point of contact for patients. They welcome patients and perform a range of specific tasks, including admitting and interviewing patients and recording patient information and/or vital signs (e.g. blood pressure), before being seen by a doctor or nurse, if available. BHWs confirmed that their role did not involve diagnosing or prescribing.

As community health mobilisers, BHWs serve as a bridge between the community and their local health centre, promoting health and engagement with existing services, often working house-to-house. They particularly encourage uptake of programmes such as child feeding and NCD prevention and screening at health centres. While they are not allowed to dispense medicines, administer vaccines, or provide direct patient care, they play a supportive role, which includes assisting midwives, blood pressure monitoring, and talking to and motivating patients to adopt appropriate health behaviours. Gina ( 38 years in service) shared:

We encourage them. This is our job: to encourage them that we have a health centre and to seek help if they feel something.

BHWs also assist patients in the community with self-management of their chronic conditions. For instance, they measure the blood pressure of those with hypertension at both the health centre and during house-to-house visits, take the opportunity to remind patients of upcoming follow-up appointments, advise them if medicines are available at the health centre for prescription refills, and educate community members. Ruby (22 years in service) shared:

I remind them that they should not be confident if they don’t feel anything [symptoms]. We don’t know if we have hypertension.

BHWs’ role as community health mobilisers also includes a public health surveillance component, following up on non-adherence and surveying prevailing health conditions in the community. April (8 years in service) described:

If we are not in the health centre, we visit our assigned area. We ask who is pregnant. We ask who is sick. We ask who has tuberculosis. We also do lectures on tuberculosis.

Denden (10 years in service) also described:

We visit them. We knock on their doors and ask why they don’t visit the centre. We remind them to finish the programme. If they give us a chance, we explain the need to continue the programme. It’s like the patient and I are a tandem.

BHWs’ local knowledge and position in the community are useful assets in their role as health mediators, helping them to identify health needs and engage with community members to link them to services . Maria (2 years in service) talked about using her local knowledge and position in the community to achieve this:

We know for example in our community who has tuberculosis. We always research them, so that we encourage them to undergo treatment. During immunisation, we notify parents to bring their child to the health centre.

BHWs also mentioned that they are often approached by patients before they have reached the health centre, which suggests that they enjoy a high level of trust among community members as intermediaries of the health system. Lili (11 years in service) told us about being contacted often by patients asking for medicines and using this opportunity to remind then about the importance of engaging with services to “ consult the doctor before taking medicine. It’s just not about taking medicine.”

Contracting arrangements and compensation

BHWs are considered part-time, volunteer workers and not government employees. Hence, they do not receive a regular salary. However, BHWs from rural areas reported being given honoraria and allowances of PhP 1150 (USD24) each month; in urban communities honoraria were also paid but their size, and that of any other allowances, varied depending on whether they were contracted by city or barangay administrations, with the latter having smaller budgets. Although urban BHWs all perform similar duties and report to local health centres, the financial incentives, in the form of honoraria to acknowledge their voluntary contributions and allowances to cover the incidental costs of carrying out their assignments (e.g. transport), varied by location. For barangay-funded BHWs, the combined lump sum was reported as PhP 2300 (USD 50) per month distributed in cash by barangay offices, and PhP 3000 (USD 60) for city-funded BHWs paid through a designated local bank. In addition to honoraria and allowances, city-funded BHWs are provided with PhilHealth membership, the national social health insurance programme.

Other non-monetary incentives that BHWs reported receiving included free medicines from the health centre, free health services, and groceries at Christmas from local or barangay administrations. Since the honoraria received by both rural and urban BHWs is insufficient to support themselves and their families, most respondents reported also having part-time jobs, mostly in the service industry, alongside their BHW duties.

Beyond economic empowerment: social positioning and common good

We now describe how relational dimensions of BHWs’ work play an important role in their initial motivations and in sustaining participation over time. Interviewees described a range of motivations for volunteering as BHWs, with the desire to serve the community and improve its health as the most frequently mentioned factor. Gina (38 years in service) described this motivation to contribute to the common good of the community:

I observed the lack of health [knowledge] in our barangay. Parents are not aware of what to do for their child’s fever. They only cover them with [wet towels]. It's just like a cold. I want to know why, why they lack attention and knowledge.

Sisa (1 year in service) cited similar motivation and particularly wanted to improve health-seeking behaviour of the community: “I want the community to be aware that if they are sick, they should consult a doctor. I advise them to go to the doctor.” Jhoanne (4 years in service) derived pleasure from serving the community: “I’m happy to serve my fellow community members. You will be happy if you do it with you heart. You will learn a lot [from being a BHW].”

Supporting the community required some BHWs to contribute their own money, for example to purchase medicines for patients who could not afford them, and to cover costs to travel to their assigned areas. April (8 years in service) described the honorarium and allowances provided as insufficient to shoulder such expenses:

During our areas of assignment, it’s our own-pocket expenses. It’s fortunate if the barangay can provide a transportation service. What if none? We will walk and of course, we will eat and drink. Not all households can provide drinks. Our PhP 3000 honorarium [and allowance] is really not enough.

Gina (38 years in service), said that it was inevitable that she would use her own funds:

I visited a patient and he had no food. I gave my own money. I also arrived when he was sick. He had no money for medicine and I gave him money. I accompanied a patient to the hospital. It’s my own pocket expense.

Mell (5 years in service) described how a provincial governor promised to increase the financial incentives given to BHWs.

Our governor’s term is about to end, but he promised that we, the BHWs, will become counterparts of nurses, doctors and midwives. We need salary. We need honorarium.

Although some BHWs reported struggling financially as a consequence of the low honorarium and allowances, they still expressed contentment with what they were doing. The opportunity to serve the community gave them a sense of fulfilment, through the relational aspects of their involvement in the programme. Their relationships with other BHWs, patients, and the wider community, as well as the new knowledge they gained, compensated for the relative lack of financial and non-financial incentives. Denden (10 years in service) expressed that it was not about how high her compensation was:

If feels good to help. Sometimes [patients] comfortably share their stories. That’s the best part. After they are treated, they go again to you and say thank you. That’s the best part to us. A simple thank you means a lot and it makes us smile. It’s not about how high is our compensation. If you enjoy your work, it’s the best feeling. It’s feels good to give service to the community.

Enhancing one’s social position, particularly through establishing new relationships in the community, gaining respect, and acquiring technical knowledge, played an important role in sustaining participation. Amy (1 year in service) echoed: “Patients trust us. One of my neighbours visited my house and asked if I can take her blood pressure or when I will next be on duty. [I feel] they trust me. They wait for me to be on duty.”

Cherry (12 years in service) shared that she gained respect (‘ respeto ’) from being a BHW:

Interviewer: What do you feel being a BHW? Are you happy?

Cherry: “I’m happy that they address me as ‘Ma’am’. If I was not a BHW, they would not address me as ‘Ma’am’. I’m happy with that. They respect me. I gain respect.”

Many BHWs spoke of the opportunities to travel outside of their localities, develop camaraderie with fellow BHWs, and acquire health knowledge as rewards in themselves, pointing to the role conferring a multiplicity of benefits. As Lili (11 years in service) said:

Being a BHW is difficult, but fun, because you are able to visit places you don't get to visit for seminars, out of town activities, and the like. And then of course the ‘bonding’ here in the health centre. It’s also fun because we learn a lot.

This camaraderie also appeared to be developed and reinforced through the model of BHW training, which was similar in both urban and rural study locations. New recruits typically shadowed more experienced BHWs and other health workers to familiarise themselves with health centre workflows. This was followed by brief training on basic procedures, such as blood pressure monitoring and first-aid. BHWs gained further knowledge and skills through participating in occasional activities organised by national and/or local government agencies, including workshops on immunisation, tuberculosis management and monitoring, and basic life support, among others. While BHWs found such activities useful, many claimed that the most valuable sources of knowledge and skills came from their interactions with experienced BHWs and from their own experiences on the job.

Finally, since the BHWs interviewed were typically mothers and wives, they also found the additional income and, as mentioned above, the opportunity to gain health knowledge and skills as attractive incentives. As Sisa (1 year in service) recalled:

I’m a mother and for my children, it’s good that I have [health] knowledge. I have no husband and I mainly guide my children. I need [health] knowledge in case of emergency. I can use what [I learn] as a BHW and apply it to my family.

This paper examines the experiences of local women in urban and rural locations of the Philippines involved in the delivery of primary care as part of the national BHW programme, a four-decade-long experiment in community participation. By focussing on the socio-political and material conditions that facilitate and sustain their involvement in the programme, as advocated by Campbell and Cornish [ 12 ], the findings from this case study identify factors that contribute to the continued success and longevity the BHW programme in these settings. Such findings may improve the impact and sustainability of similar programmes in other parts of the Philippines and other LMICs. Below, we use the concepts suggested by Campbell and Cornish to contextualise our results [ 12 ].

Symbolic context

Regarding the symbolic context, which refers to relevant meanings, ideologies or worldviews that shape community perceptions of the BHW programme, the participants’ accounts indicate that the BHW role is respected by community members and confers social status, which are two widely recognised factors known to motivate individual CHWs [ 19 ]. Those interviewed in both rural and urban locations noted that community members valued them as resource persons for health, and as peer supporters who assisted others to navigate the health system and manage their health conditions. These symbolic meanings attached to the BHW role are also formally acknowledged and reinforced in several ways. First, the BHW role is defined in national law, which recognises them as essential components of the national health workforce with specific rights and responsibilities [ 9 ]. Also, the value of BHW contributions to primary care service delivery is embodied in the monetary compensation (i.e. honorarium) mandated by the law and the various non-monetary incentives provided to them. That many of the interviewees became BHWs through appointment by community officials further signals the perceived status attached to the role.

While the respect conferred by each of the symbolic factors noted above motivated many participants to initially seek and maintain their BHW appointment, the same factors were also found to have certain stigmas attached, which could discourage community members from becoming BHWs. The commonly held view that BHW appointments are politicised or require personal connections to local officials poses a barrier to wider community participation, leading to an inequitable distribution throughout the community of the health and social benefits derived from the BHW programme. The resulting turnover of BHW staff at each electoral cycle also negatively affects the sustainability and effectiveness of the programme, as resources invested into training BHWs and building rapport within the community are lost with each new round of appointments. This also negatively impacts the ‘embeddedness’ of BHWs in the community and their integration into local health systems, which are recognised enablers to CHW programme success [ 2 ]. It is notable that reforming the BHW appointment process was recommended as far back as the early 1990s [ 20 ]. Furthermore, the national BHW law codifies the role as ‘voluntary’, despite the recognition of the essential contributions that they make to the health system [ 9 ]. While not explicitly mentioned by any participants during interviews, some may question why such an essential role is only voluntary, rather than salaried.

Our observation that the BHWs engaged in all of our study sites were exclusively female points to yet another symbolic factor that may limit wider participation and the impact of the programme: the persistent effect of cultural patriarchy on women’s labour force participation in the Philippines. Despite the country’s world-leading performance on several key indicators of gender equality, the most recent figures for 2019 indicate that just under half of all Filipinas above 15 years of age are economically active, placing them in bottom third of over 180 nations [ 21 ]. Moreover, these women’s jobs are largely restricted to those considered as extensions of the mothering, caring and educating roles defined by a patriarchal worldview [ 22 , 23 ]. The descriptions of the BHW role and factors motivating women to seek BHW appointments are consistent with this worldview, which likely explains the absence of male participation and the role’s categorisation as voluntary, as has been observed in numerous CHW programmes in both lower and higher income country settings [ 24 ]. While BHWs felt respected by community members, those who adhere to patriarchal views may not consider BHWs as sufficiently authoritative to trust or follow any health advice given, further eroding BHW’s embeddedness in the community and their impact of community health [ 2 ].

Material context

Participants in both rural and urban communities unanimously valued the various resources they were able to access as BHWs. These resources comprise Campbell and Cornish’s material context, which empowers community members to put themselves forward for appointment as BHWs [ 12 ]. Several described how the health knowledge and skills acquired as BHWs not only allowed them to perform their assigned tasks effectively, but also enhanced their roles as the carers and educators of family and friends. And while many protested the paltry level of monthly honorarium and allowances given to BHWs, this financial benefit was still considered a useful source of primary or secondary income; however, we acknowledge that this may be due to the fact that our participants were assigned to and drawn from low-income communities. These findings align closely with existing evidence, which also demonstrates clear positive links between incentive levels (both monetary and non-monetary) and CHW motivation, performance and retention [ 2 , 19 , 25 ].

The decentralisation of decision-making powers for the delivery of health care from national down to provincial, city/municipal and even barangay administrative levels [ 26 ] also appears to influence the material context of the BHW’s daily working conditions. This is most evident in the incentive packages that varied depending on the governance level to which the BHW was attached. Such decentralisation means that the amounts of local government budgets allocated to health, and primary care specifically, depends largely on the priorities of locally elected officials, which likely varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and administration to administration. This, in turn, is known to directly affect CHW’s scopes of work, remuneration and incentive levels, training and supervision, and logistical and material support (e.g. transport, medicines, equipment, etc.) needed for them to perform their duties – all of which impact their motivation, performance and retention, ultimately determining the effectiveness of CHW programmes [ 2 , 7 , 20 , 27 , 28 ]. Our findings suggest that BHW monetary incentives should be reviewed periodically by decentralised decision-makers to ensure that their levels are appropriate for their specific contexts and scopes of work, as has been advocated by several studies [ 29 , 30 ]. Also, ensuring health centres are continuously stocked with medicines and supplies will support BHW activities and foster the trust and confidence that community members have both in BHWs and in local health services.

Finally, while it is acknowledged that CHWs in LMICs can effectively support a range community-based programmes targeting NCDs, including tobacco cessation, diabetes and hypertension control [ 31 ], evidence emerging from mainly high-income settings also suggests that, with sufficient training, supervision and definition in roles, they may also be effectively integrated into the provision of other primary care services, including mental health and drug rehabilitation [ 2 , 32 ]. These issues have been prioritised by national government as reflected in several key reforms since 2012 that have mandated the involvement of BHWs in community services for mental health, hypertension, diabetes and addiction (Fig. 1 ) [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. However, CHWs should not be used as a remedy for reducing the burden of other health workers or other symptoms of a weak health system [ 36 ]. Also, when broadening CHW responsibilities, careful consideration must be given to the education, training, remuneration and commitment required from CHWs to deliver such services, as such parameters vary from programme to programme, even within countries as described above. Importantly, programmes must ensure that such expansion does not result in task overload, which could reduce productivity and worsen health population health outcomes [ 37 ].

Relational context

Perhaps the factors that have contributed most to the success and longevity of the BHW programme in the Philippines pertain to the Campbell and Cornish’s relational context, which are the features that encourage community participation through the prospect of being involved in leadership, decision-making, and the building of social capital [ 12 ]. As above, the respect from community members that the BHW role confers is derived not only from the symbolic, but also from other features that mark out these individuals as community leaders. In our study communities, BHWs viewed themselves as ‘local’ health experts, peer mentors and trainers, and brokers and facilitators of patient care and access to the local health system, particularly for the underserved and marginalised in their communities, all of which are well documented nonmonetary CHW incentives [ 19 ]. These functions appeared to underlay the profound satisfaction they derived from their position, despite the perceived inadequacy of material remuneration. It is also evident that these leadership functions succeed by fostering the development of social capital in both its bonding form (by helping community members to “get by” and benefit from existing health services), and its bridging form (by helping other BHWs to “get ahead” and succeed in the role) [ 38 ].

Recent research has, indeed, clarified the significance of social capital for the CHW role. One review concludes that the CHW’s ability to affect positive health behaviour change rests largely on the bonding and bridging social capital existing between them and community members [ 39 ]. Others have discussed how the social capital wielded by CHWs in these forms is crucial to facilitating access to care in poor and marginalised communities [ 40 ]. Again, these notions resonate clearly with the experiences and motivations mentioned by respondents in both rural and urban study locations. With continuing urban migration, the rising burden of NCDs, and the immense strain these trends are placing on the health system both in the Philippines and beyond, the value CHWs and the social capital that they bring is only likely to grow in importance [ 41 ].

However, our findings suggest that more attention could be given to BHW involvement in decision-making about their role and primary care more generally, which itself constitutes a form of linking social capital as a means of spanning power divisions between community members and those who design and fund community health services [ 38 ]. Despite being explicitly mandated by Republic Act 7883 [ 9 ], the participant accounts from our study locations provided little evidence that such involvement occurred in any institutionalised form. Meaningful participation of BHWs in decision making represents yet another means of integrating and embedding them further into the local health system [ 2 , 40 ]. In the decentralised Philippine context, this could be readily achieved, for example, through the inclusion of BHWs as ‘local’ health experts in multi-stakeholder consultations administered by local governments on the planning, financing, implementation, management and monitoring of community health services [ 42 ]. With the ongoing implementation of the Universal Health Care Act in the Philippines [ 43 ], and the renewed commitment to strengthen primary health care [ 44 ], a formidable cadre of BHWs stand ready to dedicate their time, energy and expertise to help realise these goals for the nation.

The Philippine experience of integrating CHWs in the delivery of effective PHC over nearly four decades provides an important, yet under-reported, case study of community participation and people-centred care. As many countries work to develop and strengthen CHW programmes in their effort to achieve universal health care and the health-related sustainable development goals, the lessons drawn from the Philippines could help to ensure that such programmes achieve optimal impact and sustainability.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the presence of information that could compromise research participant privacy and confidentiality.

Abbreviations

Barangay (village) Health Worker

community health worker

local government unit

low- and middle-income country

non-communicable disease

non-governmental organisation

primary health care

Philippine Peso

Responsive and Equitable Health Systems – Partnership for NCDs

United States Dollar

World health organization and UNICEF: primary health care: report of the international conference on primary health care, 6-12 September 1978. Alma-Ata, USSR; 1978.

Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, Pariyo G, Rao KD, Cometto G, Perry HB. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):39.

Article Google Scholar

Pinto RM, da Silva SB, Soriano R. Community health Workers in Brazil’s unified health system: a framework of their praxis and contributions to patient health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):940–7.

Olaniran A, Smith H, Unkels R, Bar-Zeev S, van den Broek N. Who is a community health worker? - a systematic review of definitions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1272223.

Phillips DR. Primary health care in the Philippines: banking on the barangays? Soc Sci Med (1982). 1986;23(10):1105–17.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Boerma T. The viability of the concept of a primary health care team in developing countries. Soc Sci Med (1982). 1987;25(6):747–52.

Lariosa TR. The role of community health workers in malaria control in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J Tropical Med Public Health. 1992;23(Suppl 1):30–5.

Google Scholar

Bautista VA: Reconstructing the Functions of Government: The Case of Primary Health Care in the Philippines. Philippine J Public Administration 1996, XL(3 & 4 (July–October)):231–247.

Congress of the Philippines: Republic Act no. 7883: An act granting benefits and incentives to accredit barangay health workers and for other purposes. In . Metro Manila: Republic of the Philippines; 1995.

Bautista VA. Reconstructing the functions of government: the case of primary health Care in the Philippines; 1996.

Ramiro LS, Castillo FA, Tan-Torres T, Torres CE, Tayag JG, Talampas RG, Hawken L. Community participation in local health boards in a decentralized setting: cases from the Philippines. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(Suppl 2):61–9.

Campbell C, Cornish F. Towards a "fourth generation" of approaches to HIV/AIDS management: creating contexts for effective community mobilisation. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl 2):1569–79.

Marston C, Renedo A, McGowan CR, Portela A. Effects of community participation on improving uptake of skilled care for maternal and newborn health: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55012.

World Health Organization. Task shifting: Global recommendations and guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Palafox B, Seguin ML, McKee M, Dans AL, Yusoff K, Candari CJ, Idris K, Ismail JR, Krauss SE, Lasco G, et al. Responsive and equitable health systems-partnership on non-communicable diseases (RESPOND) study: a mixed-methods, longitudinal, observational study on treatment seeking for hypertension in Malaysia and the Philippines. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e024000.

QSR International. NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 12. In: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2018.

Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385–405.

Regmi K, Naidoo J, Pilkington P. Understanding the processes of translation and transliteration in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2010;9(1):16–26.

Bhattacharyya K, Winch P, LeBan K, Tien M: Community health worker incentives and disincentives. In . Arlington, Virginia: USAID-BASICS II; 2001.

Lacuesta MC, Sarangani ST, Amoyen ND. A diagnostic study of the DOH health volunteer workers program. Philipp Popul J. 1993;9(1–4):26–36.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

DataBank. https://databank.worldbank.org/home . Accessed 8 July 2020.

Rodriguez LL. Patriarchy and Women's Subordination in the Philippines. Review of Women's Studies. 1990;1(1):15–25.

Philippine Statistical Authority: Gender Statistics on Labor and Employment. In . : Republic of the Philippines - Philippine Statistical Authority; 2017.

Ramirez-Valles J. Promoting health, promoting women: the construction of female and professional identities in the discourse of community health workers. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(11):1749–62.

Nkonki L, Cliff J, Sanders D. Lay health worker attrition: important but often ignored. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(12):919–23.

Langran IV. Decentralization, democratization, and health: the Philippine experiment. J Asian Afr Stud. 2011;46(4):361–74.

David F, Chin F. An analysis of the determinants of family planning volunteer workers' performance in Iloilo City; 1993.

Quitevis RB. Level of acceptability of roles and performance of barangay health Workers in the Delivery of basic health services. UNP Research J. 2011;20(1):1–1.

Daniels K, Sanders D, Daviaud E, Doherty T. Valuing and sustaining (or not) the ability of volunteer community health workers to deliver integrated community case Management in Northern Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0126322.

Glenton C, Scheel IB, Pradhan S, Lewin S, Hodgins S, Shrestha V. The female community health volunteer programme in Nepal: decision makers' perceptions of volunteerism, payment and other incentives. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2010;70(12):1920–7.

Jeet G, Thakur JS, Prinja S, Singh M. Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: evidence and implications. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180640.

Javanparast S, Windle A, Freeman T, Baum F. Community health worker programs to improve healthcare access and equity: are they only relevant to low- and middle-income countries? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(10):943–54.

Congress of the Philippines: Republic Act 11036: The Mental Health Act. In . Metro Manila: Republic of the Philippines; 2015.

Dangerous Drugs Board: Philippine Anti-Illegal Drugs Strategy. In . Edited by Board DD. Manila: Republic of the Philippines; 2019.

Department of Health: Implementing Guidelines on the Institutionalization of Philippine Package of Essential NCD Interventions for the Integrated Management of Hypertension and Diabetes in PHC facilities (Administrative Order 2012–0029). In . Manila: Republic of the Philippines; 2012.

Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, Walker DG, Bhutta Z: Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet (London, England) 2007, 369(9579):2121–2131.

Seidman G, Atun R. Does task shifting yield cost savings and improve efficiency for health systems? A systematic review of evidence from low-income and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):29.

Woolcock M, Narayan D. Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res Obs. 2000;15(2):225–49.

Mohajer N, Singh D. Factors enabling community health workers and volunteers to overcome socio-cultural barriers to behaviour change: meta-synthesis using the concept of social capital. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):63.

Adams C. Toward an institutional perspective on social capital health interventions: lay community health workers as social capital builders. Sociol Health Illness. 2020;42(1):95–110.

Wahl B, Lehtimaki S, Germann S, Schwalbe N. Expanding the use of community health workers in urban settings: a potential strategy for progress towards universal health coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2019.

Liwanag HJ, Wyss K. Optimising decentralisation for the health sector by exploring the synergy of decision space, capacity and accountability: insights from the Philippines. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):4.

Congress of the Philippines: Republic Act 11223: The Universal Health Care Act. In . Metro Manila: Republic of the Philippines; 2018.

Department of Health: Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Universal Heatlh Care Act (Republic Act 11223). In . Metro Manila: Republic of the Philippines; 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

The authors would like to thank the Wellcome Trust/Newton Fund-MRC Humanities & Social Science Collaborative Award scheme (200346/Z/15/Z) for providing funding for this research. The funders had no role in the design of the study, or in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Medicine, University of the Philippines – Manila, Metro Manila, Philippines

Eunice Mallari, Don Jervis Sayman, Arianna Maever L. Amit, Jhaki Mendoza & Lia Palileo-Villanueva

Department of Anthropology, University of the Philippines – Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines

Gideon Lasco

Faculty of Public Health & Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, London, WC1H 9SH, UK

Dina Balabanova, Martin McKee, Alicia Renedo, Maureen Seguin & Benjamin Palafox

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

GL, DB, MM, LPV, AR, MS, BP designed the overall RESPOND project; and GL, BP conceptualised the component described in this manuscript. EM, GL, DJS, AMA, JM, LPV, BP contributed to the development of study design, data collection and analysis. EM, GL, DJS, LPV, BP produced the first draft. All authors interpreted the data, critically revised and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benjamin Palafox .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the local research ethics board of the University of the Philippines Manila - Panel 1 (UPMREB 2017–481-01). Written informed consent from all participants was obtained prior to interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

Topic guide for BHWs.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mallari, E., Lasco, G., Sayman, D.J. et al. Connecting communities to primary care: a qualitative study on the roles, motivations and lived experiences of community health workers in the Philippines. BMC Health Serv Res 20 , 860 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05699-0

Download citation

Received : 10 February 2020

Accepted : 31 August 2020

Published : 11 September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05699-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community health workers

- Primary health care

- Human resources for health

- Health systems

- Philippines

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Research Issues in Community Nursing

- © 1999

- Latest edition

- Jean McIntosh (QNI Professor of Community Nursing Research) 0

Department of Nursing and Community Health, Glasgow Caledonian University, UK

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- Brings together some of the most influential researchers in the field of community nursing to share their knowledge and experience Makes real links between the research itself and the potential effects on practice and policy

Part of the book series: Community Health Care Series (CHCS)

21 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Other ways to access.

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (10 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

Jean McIntosh

Using research in community nursing

- Rosamund Mary Bryar

Evidence-based health visiting — the utilisation of research for effective practice

- Sally Kendall

Research questions and themes in district nursing

- Lisbeth Hockey

Exploring district nursing skills through research

- Jean McIntosh, Jean Lugton, Deirdre Moriarty, Orla Carney

Community nursing research in mental health

- Sawsan Reda

Community mental health nursing: an interpretation of history as a context for contemporary research

- Edward White

Assessing vulnerability in families

- Jane V. Appleton

Investigating the needs of and provisions for families caring for children with life-limiting incurable disorders

- Alison While

Supporting family carers: a facilitative model for community nursing practice

- Mike Nolan, Gordon Grant, John Keady

Back Matter

- nursing research

About this book

Editors and affiliations, about the editor, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Research Issues in Community Nursing

Editors : Jean McIntosh

Series Title : Community Health Care Series

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-14850-9

Publisher : Red Globe Press London

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : Macmillan Publishers Limited 1999

Softcover ISBN : 978-0-333-73504-6 Due: 30 April 1999

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIII, 224

Additional Information : Previously published under the imprint Palgrave

Topics : Nursing Research

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Community health nursing in iran: a review of challenges and solutions (an integrative review).

- 1 Student Research Committee, Nursing and Midwifery School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

- 2 Cancer Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 3 Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Background and Objective: In recent decades, nursing has witnessed many changes in Iran. Despite the numerous advances in nursing, the health system faces many challenges in community health nursing. This study aims to review the challenges in community health nursing in Iran and provide an evidence-based solution as well.

Materials and Methods: This article is an integrated review of the literature regarding the challenges in community health nursing published between 2000 and 2021 in the databases Scopus, Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Scientific Information Database (SID). After performing searches, 20 articles were selected and studied. Data analysis was done using Russell approach (2005).

Findings: The results of this study were summarized in 6 themes consisting of challenges in community health nursing education, practical challenges in community health nursing, policy-making challenges in community health nursing, management challenges in community health nursing, and infrastructural and cultural challenges. Solutions were also proposed to address each of the above issue.

Conclusions: The results of the study showed that diverse challenges exist in community health nursing in Iran, considering that community health nurses play an important role in providing primary health care and community-based care. In order to solve these challenges, the authors have some recommendations: modifying the structure of the health system with the aim of moving toward a community-oriented approach from a treatment-oriented one, developing laws to support community health nurses, creating an organizational chart for nurses at the community level, modifying nursing students' training through a community-based approach, and covering community-based services and care under insurance.

Introduction

An examination of nurses' status and position in the service provision system around the world shows that nurses constitute the largest group of health care workers ( 1 , 2 ). Community health nurses are a major link between the community and health institutions. They are able to understand and interpret the needs of the society and the objectives of health policymakers ( 3 , 4 ). In addition, community health nurses have an excellent position and status for addressing many challenges in the health system including immigration, bioterrorism, homelessness, unemployment, violence, obesity epidemic, etc. ( 1 , 2 , 5 ). From the perspective of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Nursing Association, community health nursing is a special area of nursing that combines nursing skills, public health, and a part of social activities with the aim of promoting health, improving physical and social condition, and rehabilitation and recovery from diseases and disabilities ( 6 , 7 ). Considering the importance of nursing services in the health service provision system and their role in universal health coverage, in the 66th Session of the health ministers of WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, much attention was devoted to developing plans for improving and strengthening community health nursing ( 8 ).

In all developed countries, community health nursing has had a significant growth in the health care system ( 9 ). In Canada, the community-based community health nursing has been established in 1978, aiming to maintain and promote the health of individuals, families, and communities. It also participates in the family physician and primary health care delivery ( 10 ). In some European countries, including Norway, Finland, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden, and France, community health nurses have replaced physician-centered and hospital-centered approaches, providing health services for the members of the community ( 4 , 9 , 11 – 13 ). A study conducted by WHO on community health nursing's status in some less developed and developing countries (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, Cameroon, Senegal, Uganda, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago) shows a lack of commitment and the low capacity of the policymakers to implement global and regional political tools regarding community health nursing, although most of the countries under study had a basic and operational framework for the optimal activity of community health nurses. On the other hand, only 6% of the community health nurses in these countries worked in the field of health promotion, disease prevention, and rehabilitation care, while this sector is supposed to be their main field of activity. The existing barriers preventing community health nurses from playing their role in developing countries include the lack of consensus in the realm of community health nursing practice, the lack of necessary coordination for inter-professional activities, few job opportunities for community health nurses, insufficient recognition of community health nursing, and great emphasis on clinical care in health centers ( 6 ). In Asian countries, including Japan, China, and Malaysia, community health nurses play a key role, too, focusing on the assessment of community health needs, health care delivery, and health promotion ( 9 , 14 , 15 ).

Iran is a populated country in the Eastern Mediterranean region, where health services are provided at public, private, and charity sectors ( 16 , 17 ). In Iran, since 1958, behavioral and social sciences have been included in the nursing program as a major part of its curriculum. Then, in 1986, the disciplines of community-based and community-oriented nursing were considered by educational policymakers, followed by the inclusion of community health nursing and epidemiology courses in the undergraduate curriculum. Community health nursing program is developed in line with health-oriented policies and focuses on community health. Graduates of this field work in different settings of community by combining the nursing science with other health-related sciences and evidence-based practice ( 18 , 19 ). Due to its focus on health promotion, the position of this discipline in the country's health system is very crucial, and is a major contributor to directing the community toward the 20-Year National Vision and in an ideal position to address the countless challenges against the health system ( 2 ). However, the role of nurses in Iran has not made significant progress and is limited to providing services in medical centers ( 20 ), because the viewpoint and the attitude of most Iranian health authorities is based on the employment of nurses in the secondary level of prevention, i.e., clinical care in hospitals ( 2 ). Therefore, hospitals are the most common setting for community health nurses' activities ( 21 ). Comprehensive health centers are also managed to provide health services by the workers with bachelor's and associate's degrees in family health, environmental health, occupational health, and disease control, as well as midwives. These services are provided sporadically in health service centers ( 18 ) and no effective strategies tailored to the needs of the community are adopted in order to provide care ( 22 ).

It is noteworthy and interesting that also in the family physician team, no position has been defined for community health nurses and most of the Iranian health authorities believe that nurses cannot provide significant health services ( 18 ). However, the community health nurse can be a complementary project in the family physician program and even make up for its shortcomings. This can help the government understand the health for all as a goal, the proof of which is the presence of nurses in blood pressure screening program in 2012 ( 23 ). On the other hand, numerous studies indicate community health nurses' abilities and their key role in identifying health needs and promoting community health ( 24 – 28 ). Although the education and training of community health nurses is costly for the government, their expertise is not utilized. At present, the services of community health nurses in Iran are mainly provided at the third level and at hospitals, because no position is defined for them in comprehensive health centers ( 18 , 29 ). In other words, they have no defined job position to work in this field, although in the curriculums, the future job status of this discipline is designed ( 30 ). Therefore, one of the most important infrastructural issues is to create a position and a job description in the organizational chart for community health nurses in comprehensive health centers ( 31 ).

A brief review shows that studies in Iran have mostly focused on the challenges of community health nursing education and barriers against home care ( 1 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 32 – 34 ) and other aspects of community health nursing have rarely been studied. In addition, no study has been conducted to offer solutions for addressing the challenges of community health nursing. Although other studies have been conducted in different cultures and contexts, an integrated review of them can help identify and eliminate present barriers with the aim of facilitating future planning and policymaking to enhance the status of community health nursing. Therefore, by conducting an integrated review, the present study aimed to identify the challenges of and barriers against community health nursing and the strategies to address them.

Methodology

This is an integrative review study on the challenges of community health nursing and the related solutions. The integrated review of literature is the summarization of previous studies by extracting the study results. This method is used to evaluate the strength of scientific evidence, identify gaps in current research, detect the needs for future research, create a research question, identify a theoretical or conceptual framework, and explore the research methods that have been successfully used. The integrative review study is based on Russell model which consists of 5 steps as follows: (1) formulating the research problem, objective, and question, (2) collecting data or searching through articles, (3) evaluating data, (4) data analysis, (5) interpreting and presenting the results ( 35 ).

Formulating the Research Problem, Objective, and Question

Considering the items discussed in the introduction, this study is conducted to determine the challenges of community health nursing in Iran and the related solutions. Two key questions guiding the review process include “What are the challenges of the community health nursing discipline in Iran?” and “What are the solutions to address these challenges?” Answering these two key questions will help detect the challenges of community health nursing, propose solutions to address them, and promote the community health nursing discipline.

Collecting Data or Searching Through Texts

In this study, the target population consisted of all the studies (articles and dissertations) that had been conducted in the field of community health nursing regarding its challenges, barriers, and solutions, the full texts of which were accessible. Available resources, including all the studies on the challenges of community health nursing, were reviewed in this study. A comprehensive search was done through the databases Medline, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Scientific Information Database (SID) for the papers published between 2000 and 2021 in eligible English or Farsi journals.

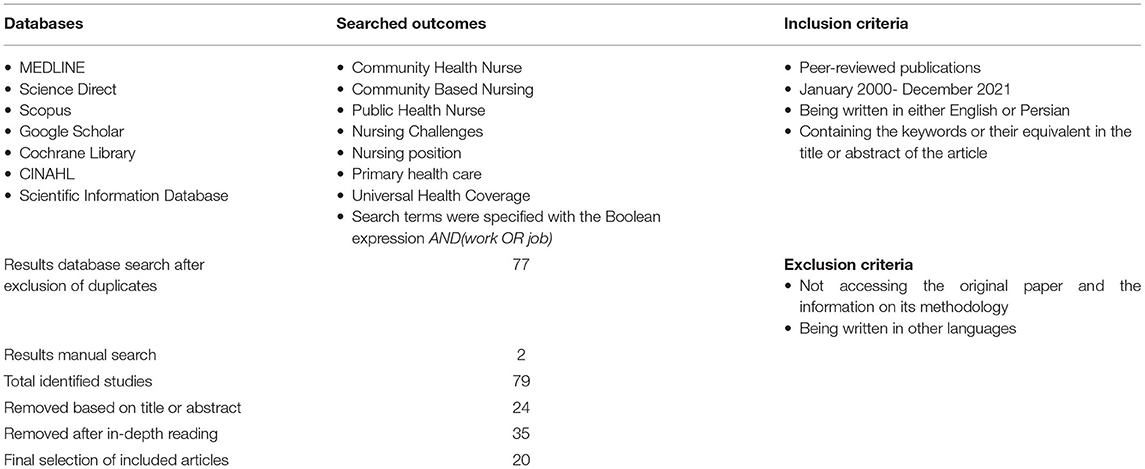

The keywords that were searched consisted of community health nurse, community-based nursing, public health nurse, nursing challenges, nursing position, and primary health care. The keywords were investigated both separately and in combination with each other ( Table 1 ). Finally, after preforming the search, 142 published articles were identified.

Table 1 . Search strategy.

Data Evaluation

The relevant articles were evaluated based on the title, abstract, text, as well as the inclusion and the exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for the studies consisted of the following: (1) examining the challenges of and barriers against community health nurses and its position, (2) containing the keywords or their equivalent in the title or abstract of the article (3) Being written in either Farsi or English. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) not accessing the original paper and the information on its methodology, (2) being written in other languages, (3) being irrelevant to the research question. It is noteworthy that in this study, there were no limitations in terms of research method, so that the results of various studies could be used.

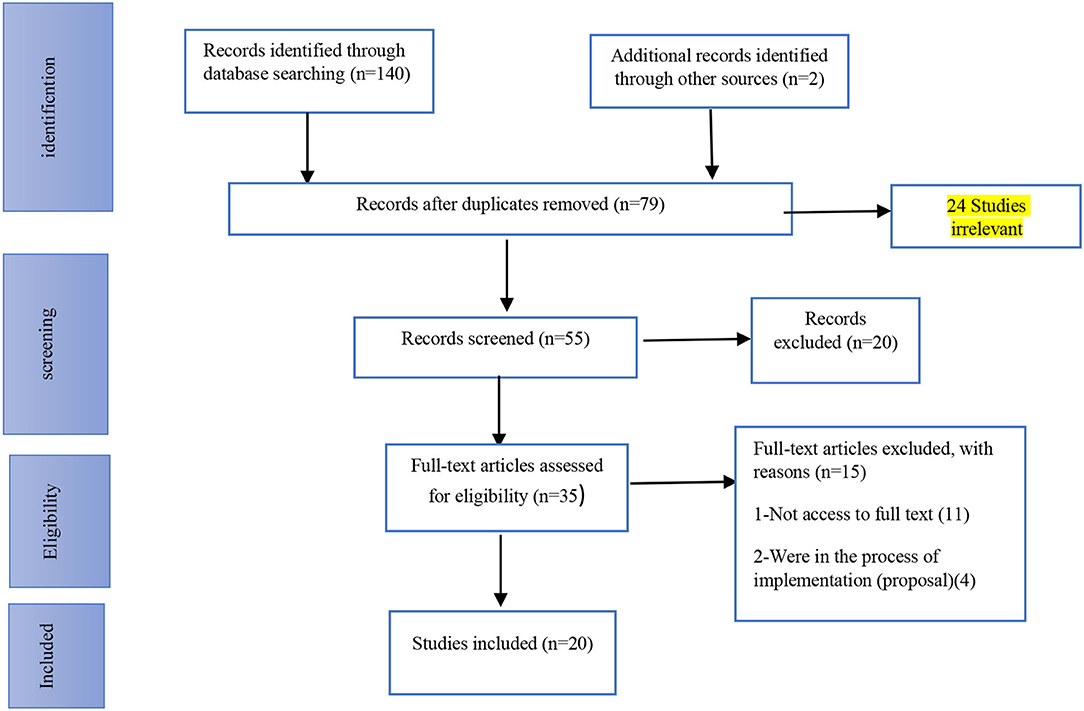

Selecting Studies

After doing the systematic search, the studies related to the search keywords were found. After removing the duplicate titles (79 articles), the title, the abstract, and the full text of the studies were reviewed by the research team, and the inclusion and the exclusion criteria were applied. Twenty-four articles were excluded due to being irrelevant and 55 articles entered the screening stage, 20 of which were excluded. Then 35 articles were examined regarding eligibility and, finally, 20 articles were included in the study. The studies were selected by a research team consisting of two nursing professors (faculty members of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences and Tehran's Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences) and one nursing PhD student (Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences). Furthermore, the research team came to a consensus through more discussion regarding the points of disagreement.

Data Analysis

At this stage, the articles were reviewed separately. Finally, 20 articles related to the purpose of the study were reviewed and analyzed. Each article was read completely and the results of the studies were extracted from them. After extracting the results of the articles, their results and statistical analysis were compared. The results with the highest frequency in these articles were further interpreted in the next phase.

Interpreting the Data and Publishing Information

At this stage, according to the analysis of the related studies, their comparison, and the data frequency, the following items were extracted.

Search Results

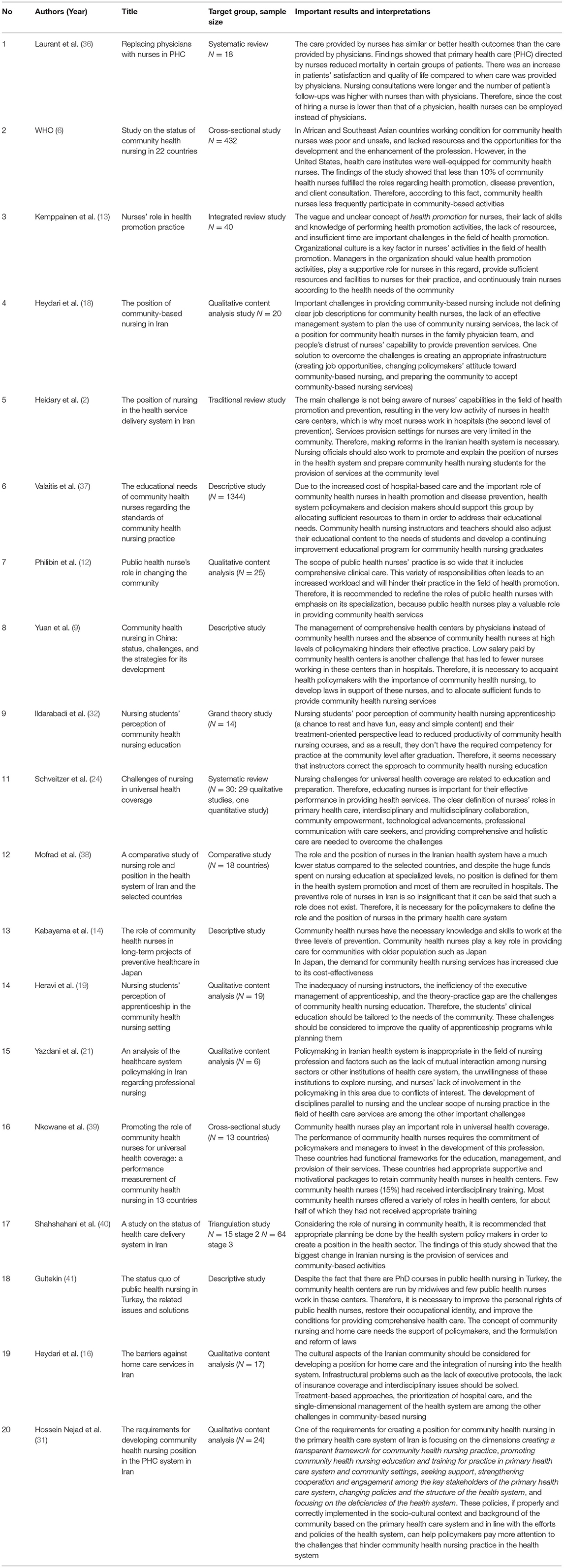

After eliminating the duplicate articles ( n = 79), 55 studies entered the screening phase and their titles and abstracts were evaluated. In total, 35 studies were included in the selection phase, and 20 remained in the study ( Figure 1 ). Twenty articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. The details are displayed in Table 2 .

Figure 1 . PRISMA flowchart for search strategy and results.

Table 2 . A summary of the critical review of previous Iranian and foreign studies.

The 20 remaining studies were published between 2010 and 2021. Five of them were review studies (systematic, meta-synthesis and integrated reviews). Seven reviews were of qualitative type (grounded and content analysis), seven reviews were cross-sectional descriptive, and one was a comparative study. Eighteen reviews were published in English and two were published in Farsi. The majority of the reviews investigated the position and the role of community health nursing in the health service delivery system and its challenges. About 40% of the reviews are related to the studies on the situation of community health nursing and the barriers against its provision in Iran. Two reviews have studied community health nursing education in Iran, and seven reviews proposed strategies to solve the challenges of community health nursing.

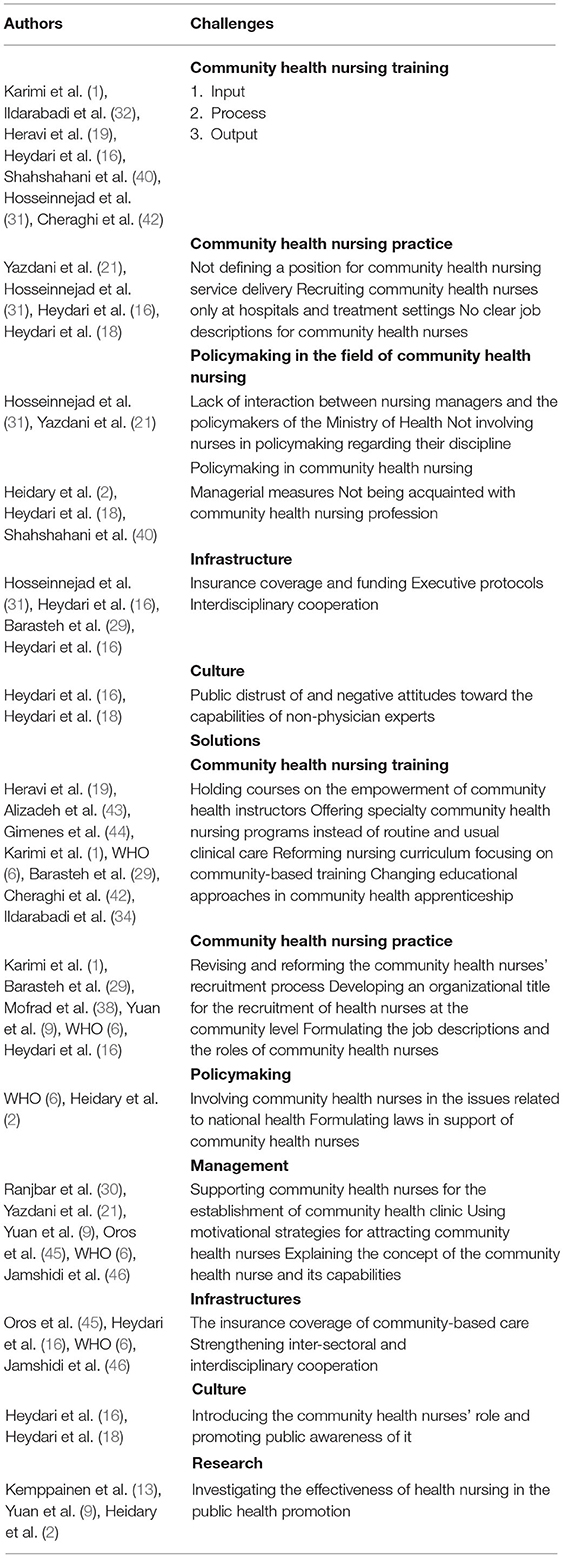

By analyzing the reviews, six themes emerged in the field of community health nursing challenges, and six other themes concerned the strategies to overcome the challenges. The details are displayed in Table 3 .

Table 3 . The challenges of community health nursing and the identified solutions.

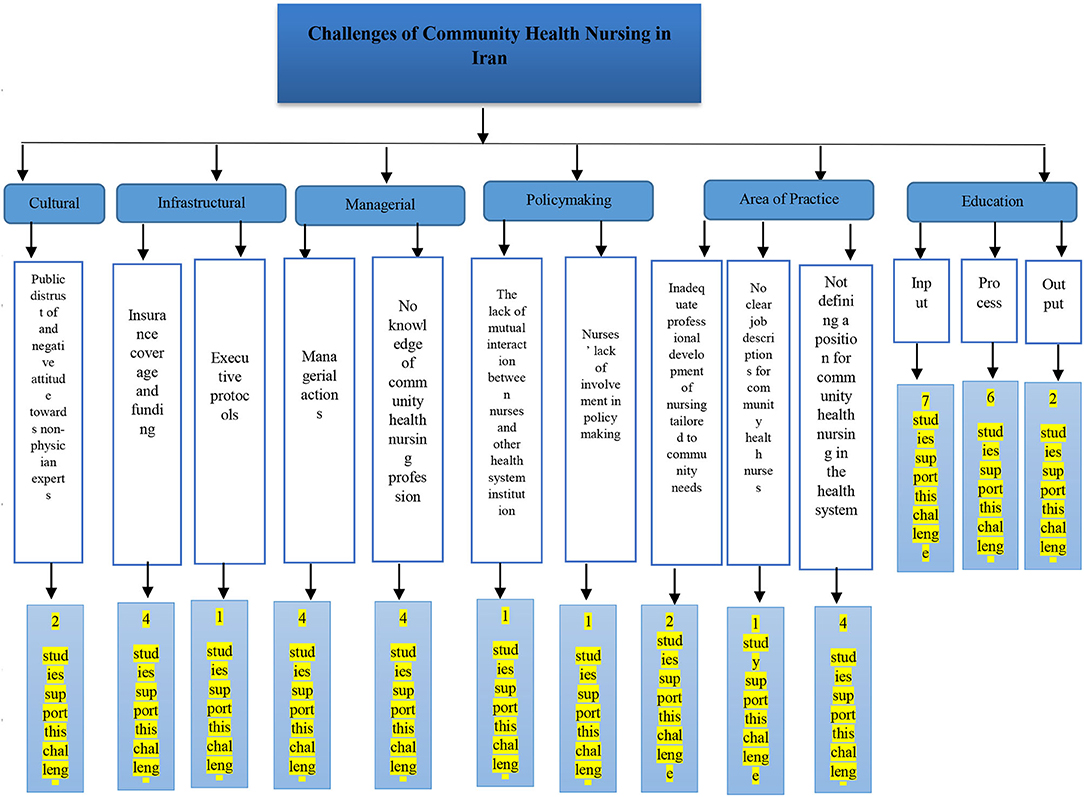

The Challenges of Community Health Nursing in Iran

There are several challenges regarding community health nursing in Iran, which have been addressed in previous studies ( Figure 2 )

Figure 2 . Community health nursing challenges in Iran.

Challenges of Community Health Nursing Education

Several challenges were mentioned in the literature in regard with the education, which were divided into the three areas input, process , and output .

Input. Students' poor understanding of community health nursing lessons, considering the community health nursing apprenticeship as futile, and, in some cases, even as a chance to rest, as well as their poor motivation for active participation were mentioned as important challenges ( 32 ). Moreover, nursing students' treatment-based and disease-based perspective and their poor community-based and holistic perspective is another challenge in this area ( 1 , 2 ).

Another challenge in this area is the insufficient skills and experience of nursing educators in the field of community-based educational planning, their inadequacy in conducting community health apprenticeship programs and the related evaluations, and ineffectiveness of community health apprenticeship ( 19 , 42 ). In another study, the low quality of community health nursing education, the use of traditional methods, reviewing theoretical topics during apprenticeship, and not implementing appropriate educational models were mentioned as challenges ( 1 , 19 ). Other studies have shown that the educational system of medical universities is not adjusted to PHC and the educational content is not tailored to the needs. Therefore, the university graduates do not have the required skills to deal with problems and academic education courses should be promoted and based on PHC ( 22 , 47 ).

The Process. The poor presence of community-based care in the nursing education and focusing on hospital care have been referred to as one of the most important challenges according to several studies. Nursing education in Iran is more focused on clinical education. Most nursing schools train their students to play the traditional nursing role, while community needs the training of nurses according to holistic perspectives ( 1 , 16 , 19 , 40 ). Limited community health credits and the hours of apprenticeship in health centers will lead to poor productivity of apprenticeship programs ( 2 , 31 ). The theory-practice gap, i.e., the inapplicability of some health theory content in the apprenticeship settings, and the lack of community-based education standards in nursing were mentioned as other challenges in this field ( 1 , 19 ).

Output. Recruiting nurses only in clinical settings such as hospitals and the absence of a particular and appropriate professional position for nursing and community health nursing graduates in health centers has prevented nursing graduates from acquiring the necessary skills to provide health care ( 31 , 42 ).

Practical Challenges of Community Health Nursing

One of the most important challenges in this field is not defining positions for the provision of nursing services in the community and various settings of the health system. Therefore, in hospitals, which are considered as the main position of nurses, appropriate roles are not defined for them with the aim of health promotion ( 21 ). Another challenge is hiring nurses and community health nurses in medical settings and hospitals. Nursing care in Iran focuses on the provision of care at the secondary level of prevention; therefore, the preventive role of nurses is overshadowed and nurses are not involved in health care homes and comprehensive health centers, which is the first level of people's contact with the health care system ( 16 , 31 , 40 ). The lack of adequate and proper health care in remote and rural areas is one of the biggest national concerns, and most of the health care workers in rural and remote areas are Behvarzes (rural health workers) and practical nurses, while no job opportunities exist for community-based nursing postgraduates in comprehensive health centers, prevention units, and health care homes ( 2 ). The lack of clear job descriptions for community health nurses and community-based nursing in the country is another challenge, as community health nursing is only a field for study, not suited for practice ( 18 ). Another important challenge will be the inadequate professional development of nursing compatible with the needs of community, the lack of competent staff in the field of community-based nursing, and the lack of nursing promotion in accordance with the pattern of diseases in the country ( 29 ).

One of the important areas of community health nursing is performing home visits and the provision of care and counseling in the home environment. A challenge that community health nurses face in this regard is the problems with ensuring their safety ( 16 ).

Policymaking Challenges in Community Health Nursing