Macbeth and Violence — Example A Grade Essay

Here’s an essay on Macbeth’s violent nature that I wrote as a mock exam practice with students. Feel free to read and analyse it, use the quotes and context for your own essays too!

It’s also useful for anyone studying Macbeth in general, especially with the following exam boards: CAIE / Cambridge, Edexcel, OCR, CCEA, WJEC / Eduqas.

Thanks for reading! If you find this resource useful, you can take a look at our full online Macbeth course here . Use the code “SHAKESPEARE” to receive a 50% discount!

This course includes:

- A full set of video lessons on each key element of the text: summary, themes, setting, characters, context, attitudes, analysis of key quotes, essay questions, essay examples

- Downloadable documents for each video lesson

- A range of example B-A* / L7-L9 grade essays, both at GCSE (ages 14-16) and A-Level (age 16+) with teacher comments and mark scheme feedback

- A bonus Macbeth workbook designed to guide you through each scene of the play!

For more help with Macbeth and Tragedy, read our article here .

THE QUESTION

Starting with this speech, explore how far shakespeare presents macbeth as a violent character. (act 1 scene 2).

Debate: How far is Macbeth violent? (AGREE / DISAGREE)

Themes: Violence (break into different types of violence)

Focus: Character of Macbeth (what he says/does, other character’s actions towards him and speech about him)

PLAN — 6–8 mins

Thesis – Shakespeare uses Macbeth to make us question the nature of violence and whether any kind of violent behaviour is ever appropriate

Point 1 : Macbeth has an enjoyment of violence

‘Brandished steel’ ‘smoked with bloody execution’

‘Unseam’d him from the nave to’th’chops’ ‘fixed his head upon the battlements’

Context — Thou shalt not kill / Tragic hero

Point 2 : Macbeth is a violent character from the offset, but this violence is acceptable at first

‘Disdaining Fortune’ ‘valiant cousin/ worthy gentleman’

‘Worthy to be a rebel’

Context: Divine Right of Kings / James I legacy

Point 3: The witches and Lady Macbeth manipulate that violent power

‘Fair is foul and foul is fair’ ‘so foul and fair a day I have not seen’

‘Will these hands never be clean?’ ‘incarnadine’

‘Is this a dagger I see before me?’

Context: Psychological power — Machiavelli / Demonology

(Point 4) Ultimately, Macbeth is undone by violence in the end

Hubris — ‘Macduff was from his mother’s womb untimely ripp’d’

‘Traitor’ ‘Tyrant’

‘Life is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’

Context: Violence for evil means is unsustainable, political unrest equally is negative and unsustainable — support James

Macbeth is certainly portrayed as a violent character from the offset, but initially this seems a positive trait: the Captain, Ross and others herald him as a great warrior, both an ally and valuable asset to Duncan and his kingdom. Furthermore, Duncan himself is overjoyed at Macbeth’s skill in battle. Yet, as the play progresses and Macbeth embarks upon his tragic fall, Shakespeare encourages us to question the nature of violence itself, and whether any kind of violence is truly good. Ultimately, Shakespeare demonstrates that Macbeth’s enjoyment of violence works against him, as it is manipulated by the evil forces at work in the play, and it ends in destroying not only himself but his entire life’s work, reputation and legacy.

Firstly, Macbeth is established as a character who embraces violence, though he uses it as a force for good in the sense that he defends Duncan and his Kingdom against traitors and the King of Norway’s attack. In the play, it is interesting to note that Macbeth’s reputation precedes him — despite being the central focus of the tragedy, we do not meet him until Act 1 Scene 3, and so this extract occurs before we have seen the man himself. The Captain’s speech begins with the dramatic utterance ‘Doubtful it stood’, creating a sense of tension and uncertainty as he recounts the events of the battle to Duncan and the others. Yet, the tone of the speech becomes increasingly full of praise and confidence as he explains how Macbeth and Banquo overcame ‘Fortune’, the luck that went against them, and their strong willpower enabled them to defeat ‘the merciless Macdonwald’, the alliteration serving to underscore the Captain’s dislike of the man, while the adjective ‘merciless’ implies that the traitor himself was also cruel and violent. The sense that Macbeth enjoys the violence he enacts upon the traitor is conveyed through visual imagery, which is graphic and quite repellent: ‘his brandish’d steel… smoked with bloody execution’ and ‘he unseam’d [Macdonwald] from the nave to th’chops’. The dynamic verb ‘smoked’ suggests the intense action of the scene and the amount of fresh blood that had stained Macbeth’s sword. Furthermore, the verb ‘unseam’d’ suggests the skill with which Macbeth is able to kill — he does not simply stab the traitor, he delicately and expertly destroys him, almost as if he’s a butcher who takes pleasure in his profession, and indeed at the end of the play Macduff does call him by this same term: ‘the dead butcher and his fiend-like queen’. Interestingly, much of the violence that occurs in the play happens offstage, Duncan is murdered in between Acts 2.1 and 2.2., as are Banquo and Macduff’s family. Even in this early scene, the audience hear about the violence rather than experiencing it directly. This suggests perhaps that for a Jacobean audience at a time of political instability, Shakespeare wanted to discourage the idea or enjoyment of violence whilst still exploring the idea of it in human nature and psychology. Furthermore, a contemporary audience would be aware of the Biblical commandment ‘thou shall not kill’, which expressed that violence and murder of any kind was a sinful act against God. Therefore, we can see that Macbeth is established as a tragic hero from the offset, though he is a successful character and increasing his power within the feudal world, this power is built upon his capacity for and enjoyment of violence, which will ultimately cause him to fail and in turn warn the Jacobean audience against any kind of violence in their own lives.

We could also interpret Macbeth as inherently violent, but under control of his own power at the beginning of the play, an aspect of himself which degenerates under the influence of evil. Though he is physically great, he is easily manipulated by the witches and Lady Macbeth, all of whom are arguably psychologically stronger. The use of chiasmus in the opening scene — ‘fair is foul and foul is fair’ is echoed by Macbeth’s first line in Act One Scene 3: ‘so foul and fair a day I have not seen’. Delving deeper into the meaning of these lines also reveals more about Shakespeare’s opinions on the inherent nature of violence; though the language is equivocal and can be interpreted in many ways, we can assume that the witches are implying that the world has become inverted, that ugliness and evil are now ‘fair’, what is seen as right or normal in Macbeth’s violent world. Macbeth uses similar lines, but with a different meaning, he is stating that he has never seen a day so ‘foul’, so full of gore and death, that was at the same time so ‘fair’, so good in terms of outcome, and positive for the future. Shakespeare is perhaps exposing an inherent paradox in violence here, that war and murder is thought by many to be noble if it leads to a positive political outcome. Furthermore, Lady Macbeth encourages and appeals to Macbeth’s sense for violence by directly associating it with masculinity and male traits that were considered noble or desirable in the Jacobean era. She questions him just prior to Duncan’s death, stating ‘I fear thy nature is too full o’th’milk of human kindness / to catch the nearest way’, using ‘milk’ as a symbol of femininity to imply his womanly and cowardly nature, while in turn asking evil spirits to ‘unsex’ her and fill her with ‘direst cruelty’. In this sense, it could be argued that Shakespeare is commenting on the connections between nature and violence, perhaps a Jacobean audience would have understood that Macbeth fighting for the king was an acceptable outlet for his violence, whereas Macbeth using violence for personal gain and Lady Macbeth’s wish to become more masculine, and therefore more violent, are all against the perceived view of natural gender and social roles of the time. Overall, we could say that the culture itself, which encourages Machievellian disruption and political vying for power through both women and men stepping out of the social norms of their society, encourages more violence and evil to enter the world.

Alternatively, it could be argued that Shakespeare uses Macbeth’s success through violence to criticise the nature of the Early Modern world, and so it is not Macbeth’s violence itself which is at fault, but the world which embraces and encourages this in him. Duncan responds to the Captain’s speech by exclaiming ‘valiant cousin’ ‘worthy gentleman!’, demonstrating his extreme faith in Macbeth’s powers. The Captain additionally terms him ‘Brave Macbeth’, stating ‘well he deserves that name’, suggesting that the general structure of the world supports violent and potentially unstable characters such as Macbeth, enabling them to rise to power beyond their means. Interestingly the downfall of Macbeth is foreshadowed early on in this extract, as the term ‘worthy’ is also applied to the traitor in the Captain’s speech, when he states Macdonwald is ‘worthy to be a rebel’, the repetition of this adjective perhaps subtly compares Macdonwald’s position to Macbeth’s own, as Macbeth’s own death also is similar to the initial traitors, with his own head being ‘fixed…upon the battlements’ of Inverness castle. Through this repetition of staging and terminology, we realise that the world is perhaps at fault more than Macbeth himself, as it encourages a cycle of violence and political instability. Though there is a sense of positivity in extract as Duncan has succeeded in securing the throne and defeating the traitor, the violent context in which this action occurs, being set in 11th century feudal Scotland, suggests the underlying political unrest that mirrors the political instability of Shakespeare’s own time. The play was first performed in 1606, three years after James I had been made King of England (though he was already King of Scotland at this time), and in 1605 there had been a violent attempt on his life with the Gunpowder Plot from a group of secret Catholics who felt they were being underrepresented. Shakespeare’s own family were known associates of some of the perpetrators, so it is likely that he intended to clear suspicion of his own name by creating a play that strongly supported James I’s Divine Right to rule. In this sense, we can see that the concept of a cycle of violence that is created through political instability is integral to Shakespeare’s overall purpose, he is strongly conveying to the audience that not only is Macbeth’s personal violence sinful, but the way in which society encourages people to become violent is terrible and must be stopped, for the good of everyone.

In summary, Macbeth is established from the offset as a violent character, who takes pride and pleasure in fighting and killing. However, Shakespeare is careful not to make this violent action central to the enjoyment of the play (until the very end, when Macbeth himself is defeated), to force us to engage with the psychology of violence more than the physical nature of it. Though the women in the play are passive, Lady Macbeth and the witches prove to incite violence in Macbeth’s nature and lead ultimately to more evil entering the world. Finally, we can interpret the violence of the play as a criticism of the political and social instability of Jacobean times, rather than it being purely Macbeth’s fault, Shakespeare is exploring how the society itself encourages instability through the encouragement of Machiavellian ideas such as power grabbing, nepotism, greed and ambition.

If you’re studying Macbeth, you can click here to buy our full online course. Use the code “SHAKESPEARE” to receive a 50% discount!

You will gain access to over 8 hours of engaging video content , plus downloadable PDF guides for Macbeth that cover the following topics:

- Character analysis

- Plot summaries

- Deeper themes

There are also tiered levels of analysis that allow you to study up to GCSE , A Level and University level .

You’ll find plenty of top level example essays that will help you to write your own perfect ones!

Related Posts

The Theme of Morality in To Kill A Mockingbird

Unseen Poetry Exam Practice – Spring

To Kill A Mockingbird Essay Writing – PEE Breakdown

Emily Dickinson A Level Exam Questions

Poem Analysis: Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare

An Inspector Calls – Official AQA Exam Questions

The Dolls House by Katherine Mansfield: Summary + Analysis

An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge: Stories of Ourselves:

How to Get Started with Narrative Writing

Robert Frost’s Life and Poetic Career

© Copyright Scrbbly 2022

William Shakespeare

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

To call Macbeth a violent play is an understatement. It begins in battle, contains the murder of men, women, and children, and ends not just with a climactic siege but the suicide of Lady Macbeth and the beheading of its main character, Macbeth . In the process of all this bloodshed, Macbeth makes an important point about the nature of violence: every violent act, even those done for selfless reasons, seems to lead inevitably to the next. The violence through which Macbeth takes the throne, as Macbeth himself realizes, opens the way for others to try to take the throne for themselves through violence. So Macbeth must commit more violence, and more violence, until violence is all he has left. As Macbeth himself says after seeing Banquo's ghost, "blood will to blood." Violence leads to violence, a vicious cycle.

Violence ThemeTracker

Violence Quotes in Macbeth

Mr Salles Teaches English

How is Violence Portrayed in Macbeth?

Another top grade essay.

Students keep sending me essays, which is great for you, and terrible for me.

I’m busy making videos. I’m releasing courses on AQA GCSE language . I’m collabbing with Mr Everything English and First Rate Tutor.

But, exams are coming - and so I turn to Tilf.io.

I’ve just had a chat with Kelly, and I’ve said students need more than one free go. And she says, ah, but they can. If you get anyone else to sign up for a free go, you get more free goes. I wish you would do that so that you don’t send them to me!

Give Tilf.io a go. It now gives you a mark too.

In Shakespeare's archetypal, allegorical play "Macbeth", Macbeth's violence is constructed as a warning outlining the detrimental repercussions on morality when employing violence to fulfil selfish ambitions in order to obtain power. In Macbeth's character, violence is inextricably liked to his ambition and his path to usurping the throne, as well as the gender roles prescribed by a patriarchal society that incites a trajectory to prove ones self-worth by procuring an unblemished masculinity.

(This introduction sets up a clear argument about the thematic link between violence and ambition in 'Macbeth'. You effectively introduce the idea that violence is not only a physical act but also tied to societal expectations of masculinity. However, be cautious with phrasing to ensure clarity; 'inextricably liked' may be a typo for 'linked'.)

In the extract Macbeth’s violent acts are commemorated in battle, using violence to defend one's country and defeat ones enemies is valued and respected. The Captain illustrates Macbeth's brave conquering as honoured: "Disdaining Fortune... smoked with bloody execution". The use of religious imagery within "fortune", could suggest how Macbeth's acts of "valour" were honourable and true, how he is so "worthy" that he can destroy his countries enemy, by his own might, without god's help. In this Shakespeare displays the idea that some violent acts are necessary and "valiant", and so initially Macbeth's acts are alined with God and the divine order. Alternatively, "fortune"could allude to fate and the predetermined, relating to gods divine plan. However, it is curious how Macbeth wasn't blessed or crowned with "fortune", he was "disdaining fortune" suggesting a disregard, deeming the fortune of god unworthy. Although, Macbeth is being celebrated and praised, there is an underlying theme of him usurping the fortune of god to obtain a violent conquering in battle.

(You provide a nuanced analysis of the extract, exploring the dual nature of violence as both honorable and potentially hubristic. The examination of the term 'fortune' is insightful, showing an understanding of the complexity of Shakespeare's language. However, ensure that you maintain a focus on the question by explicitly linking these observations back to the presentation of violence.)

Furthermore, the metaphor of "smoked" connotes to heat and hell, foreshadowing the moral, phycological and physiological ramifications of Macbeth's violent acts. Shakespeare instills this idea of violence within Macbeth's character as inherent, from the beginning of the play and even while Macbeth is being payed homage to thee is an underlying shadow of violent acts to defend Scotland that is accepted, now even thought these violent acts, later, bring about his tragic downfall. Perhaps, Shakespeare constructs this in order to appease James I, Shakespeare's patron- this idea of the tragic and eternal consequence of even a trusted, honoured soldier, betraying their king, usurping power- dissuading anyone from treason.

(Your analysis of the metaphor 'smoked' is effective in exploring the ominous undertones of Macbeth's violence. The connection to King James I and the potential political implications of the play is a sophisticated contextual point. However, be mindful of spelling and grammatical errors ('phycological' should be 'psychological', 'payed' should be 'paid', and 'thee' seems out of place) as they can detract from the clarity of your argument.)

In acts 2 Macbeth's portrayal as a violent character is embossed with mania and aggression, initiating his decent from "worthy" to "fiend". as Macbeth outlines his ambitions, he says "with Tarquins ravishing strides, towards his design". This remark to Tarquin, a Roman tyrant who rapped his wife, revealed the constraints that Macbeth has been "cabined, cribbed, confined" too. Shakespeare utilises the prescribed gender roles of society to expose their corrupt and immoral ways. Macbeth, emasculated by lady Macbeth's "when you durst do it, then you were a man", has lost a sense of his own identity within his masculinity. his aspiration to emaciate Tarquin, who ruled ruthlessly, signifies that he now perceives power synonymous with brutality and toxic masculinity. Moreover the idea of "design" further alludes to gods "design" of creation, demonstrating that Macbeth's ambition, fuelled by violent means, is to obtain the intention, time and power of the gods. To a pious Jacobean audience, this idea of Macbeth's aspiration for transgression against the natural order exacerbates Macbeth as, not only a physically violent character but also a threat to gods diving order.

(This paragraph offers a strong analysis of Macbeth's descent into violence and the influence of gender roles. The reference to Tarquin is well-chosen and effectively used to illustrate Macbeth's changing perception of power. However, there are several typographical errors ('rapped' should be 'raped', 'emaciate' seems incorrect, 'gods' should be 'God's', 'durst' should be 'dare', 'diving' should be 'divine') that need to be addressed. Additionally, ensure that your analysis remains focused on the presentation of violence as per the essay question.)

In conclusion, Shakespeare presents Macbeth's ambition as innate and internalised. As a "worthy" character, although patriotically, Macbeth employs violence so powerful that it can overwhelm and disregard fortune". furthermore, as a tyrant, Macbeth's violence is continually ingrained into his mentality and being, inflamed from his emasculation. This cyclical structure, demonstrates how Macbeth is "smoked" in eternal damnation for his instinctuall violence and brutality to fulfil his own self-serving ambition.

(Your conclusion effectively summarises the key points of your essay, reinforcing the idea that Macbeth's violence is a product of his ambition and societal pressures. However, the conclusion could be strengthened by more explicitly tying these points back to the question of how violence is presented in the play. Also, watch out for typographical errors ('instinctuall' should be 'instinctual', 'fortune"' is missing the opening quotation mark) and ensure that the final sentence is grammatically complete.)

Mr Salles Teaches English is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts which help you get top grades, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Mark: 21 - 24 (this is a beta feature and mark may not be very accurate)

Overall feedback:

Your essay demonstrates a thoughtful and developed consideration of the presentation of violence in 'Macbeth', with a particular focus on the interplay between ambition, societal expectations, and gender roles. You provide a range of apt references and integrate them well into your interpretations. To improve, pay close attention to typographical and grammatical accuracy, as errors can detract from the overall quality of your work. Additionally, ensure that each point you make is explicitly linked back to the question to maintain a clear and focused argument throughout.

What went well: The essay shows a strong understanding of the thematic complexities in 'Macbeth' and provides a nuanced analysis of the text. The use of context to inform the interpretation is particularly well done.

Even better if: To achieve a higher level, work on refining the precision of language and proofreading to eliminate typographical errors. Ensure that all analysis is clearly and consistently linked back to the question of how violence is presented in the play.

Thank you for reading Mr Salles Teaches English. This post is public so feel free to share it with someone else who wants top grades.

Ready for more?

Macbeth by William Shakespeare: a timeless exploration of violence and treachery

Senior Lecturer (English and Drama) ANU, Australian National University

Disclosure statement

Kate Flaherty works for the Australian National University. She has received funding from the Australian Research Council.

Australian National University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

In our Guide to the Classics series, experts explain key works of literature.

Macbeth issues a warning: the greatest risk to the inner life comes from the delusion that it does not exist.

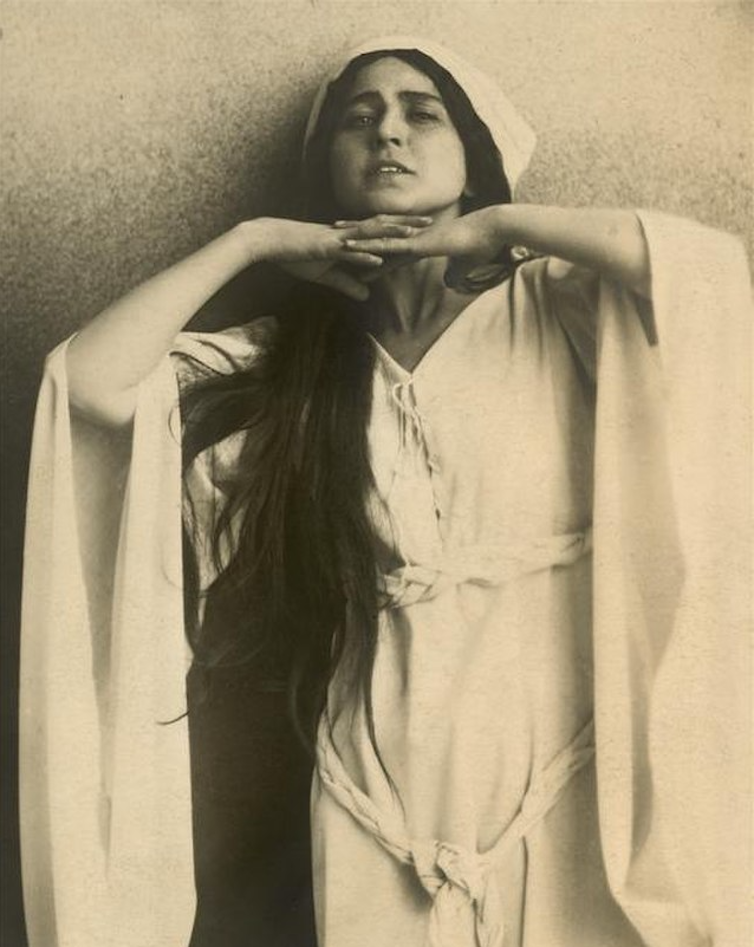

“A little water clears us of this deed,” says Lady Macbeth, thinking that getting the look right will make it right. But in doing so she commits treachery upon her inner life.

In a world where existence seems increasingly to equate to self-projection, she is an example of the mistake we make when we see the visible surface of public and social media as the place where reality plays out, the place where we see what we are.

Macbeth, like most of Shakespeare’s plays, sets two worlds spinning: one of outer action and one of inner being. The collision of their orbits provides the spark for the drama. The themes of Macbeth’s outer world of action are violence and treachery. The intersecting themes of its inner world are ambition, and moral reasoning.

In exploring what holds a society together and what tears it apart, the play doesn’t just condemn violence, it dramatises its uses. The play showcases both loyal violence and treacherous violence.

In Act One, Scene One, a soldier reports that Macbeth, a Scottish general, has shown prowess on the battlefield and “unseamed” his rebel opponent, Macdonald, “from the nave to th’ chops.” That means he cut him in half.

Macbeth does this in loyal service to King Duncan, and usually enters the stage splattered with blood, that of his victims and his own – blood lost in service to his king. The military campaign is to suppress domestic rebellion. Among the rebels is the “disloyal traitor” the Thane of Cawdor, whose title Duncan transfers to Macbeth, commanding that the treacherous clan chief be executed.

Macbeth’s first promotion, then, is gained through the sanctioned violence of killing traitors. There is a fragile moment at the beginning of the play, when this violence seems to have restored order.

Read more: 'Supp'd full with horrors': 400 years of Shakespearean supernaturalism

Macbeth’s second promotion is also achieved through violence, but this time by premeditated treachery. The witches on the heath greet him as Thane of Glamis, which he is, Thane of Cawdor, which we know from Duncan’s command that he will be, and “king hereafter”.

This sets the spark to the powder keg of Macbeth’s ambition. Violence is in his repertoire and he needs only to take one violent step further to fulfil their prophecy.

The thought of killing the king, a thought “whose murder yet is but fantastical”, occurs to him immediately. And when he arrives back at his castle, his wife Lady Macbeth urges him to “catch the nearest way” to fulfilment of the prophecy by stabbing King Duncan to death as he sleeps in their home.

Here one of the inner-world themes intrudes – who is morally responsible for what Macbeth does? Do the witches wield power over him? Does Lady Macbeth, as the architect of regicide, carry equal blame with Macbeth?

Read more: Guide to the classics: Shakespeare's Hamlet, the Everest of literature

Outer and inner dimensions

The unfolding of their murderous plot is dramatised by Shakespeare as having outer and inner dimensions. The physical world is portrayed as instantly ruptured by their act of violence. Even before Duncan’s murder is discovered, Lennox speaks of the unruly night that has passed: chimneys were blown down, strange lamentings and screams of death were heard in the air, and the earth shook and was feverish.

There is dramatic irony in Macbeth’s response to this poetic description of cosmic disorder: “It was a rough night.”

Society is also fractured. Duncan’s sons flee Scotland. A mood of paranoid crisis sets in as Macbeth is crowned.

But the treachery resonates inwardly, too, and Shakespeare keeps the inner dimension perpetually before the audience. That image from Act One of a man split down the middle is a potent symbol for the destruction the Macbeths have wrought upon themselves.

The order of Macbeth’s mind begins to break down the moment he murders his king. He roams out of the king’s chamber with the bloody daggers still in his hands saying he has heard a voice cry, “Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep.”

Lady Macbeth seems to preserve her practical mindset for a time. She says “a little water clears us of this deed”. But this is another moment of dramatic irony. Her moral delusion is patent.

It seems that Macbeth, with his auditory and ocular hallucinations, has the clearer moral vision. Inevitably, her sleeping mind goes to war with her waking consciousness: “Out damn spot!” She cannot unsee the blood on her hands.

The Macbeths have failed to anticipate that their inner lives – their minds and their functional connection with the world – will be broken by their outer action. Remarkably, these mental, physical, spiritual breakdowns are rendered from the sufferers’ point of view.

Before he kills the king, Macbeth gives a speech about ambition that shows he has the moral insight to avoid the crime. He says he has “no spur to prick the sides of [his] intent”, using the metaphor of riding a horse to express that there is nothing about Duncan to urge him forward into the act of murder.

Macbeth realises he has “only vaulting ambition”, which leaps over itself and falls on the other side. He anticipates the catastrophe, but he kills the king anyway.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Shakespeare’s sonnets — an honest account of love and a surprising portal to the man himself

The twists and turns of moral reasoning

Why does Shakespeare include such contradictions?

Shakespeare understood that it is spellbinding to witness a character forming an inner resolution, or breaking one. In Macbeth, the stakes are high: an innocent life and a kingdom’s peace hang in the balance. The tension is relentless. Lady Macbeth enters, cutting off Macbeth’s reflection on ambition. He has just reasoned himself out of committing the murder, and she reasons him back into it.

The play dramatises the twists and turns of moral reasoning and the pressure of emotional coercion on conscience. Macbeth is wise and compassionate one instant, and preparing to kill his friend the next. This challenges our tendency to see the world in black and white, populated by good people and bad people.

All of the themes of Macbeth – violence, treachery, moral reasoning, conscience and ambition – were close the surface of public consciousness in Shakespeare’s day.

Since Henry VIII left the Catholic Church, establishing himself as the head of the Church of England in 1534, the nation’s political landscape had been riven by religious opposition. This affected people’s everyday lives and challenged their deepest inner convictions. In 1557, you could be burned as a heretic for being Protestant; in 1567, you could be burned as a heretic for being Catholic.

Being able to see the soul in motion, as Shakespeare allows his audience to do, was a fantasy that interrogators of both Catholic and Protestant persuasions would have cherished.

By the time Shakespeare wrote Macbeth, he was a member of The King’s Men – a playing company patronised directly by a new king – James the First of England and the Sixth (you guessed it) of Scotland. What can we make of the fact of Shakespeare writing a Scottish play for a Scottish king, who is also the boss of his particular business enterprise? He had to be very careful.

Shakespeare steered a clever course. His play seems mildly topical and politically correct on the surface, but underneath it complicated the moral questions of its moment.

The first thing to be aware of is that James had a preoccupation with the occult. In 1597, James had published a book called Demonology , seeking to prove and condemn witchcraft. He had it published again in 1603 when he became King of England.

Shakespeare seems to pander to this obsession when he includes witches in his play, who discuss spells and make prophetic predictions.

Notice, though, that Shakespeare leaves unanswered the question of their moral culpability. We are left wondering whether it pleased or disturbed King James that the supernatural element in the play explains very little about the actions of its characters. Shakespeare portrays the Macbeths’ ambition for power as perfectly adequate motivation for their criminal action.

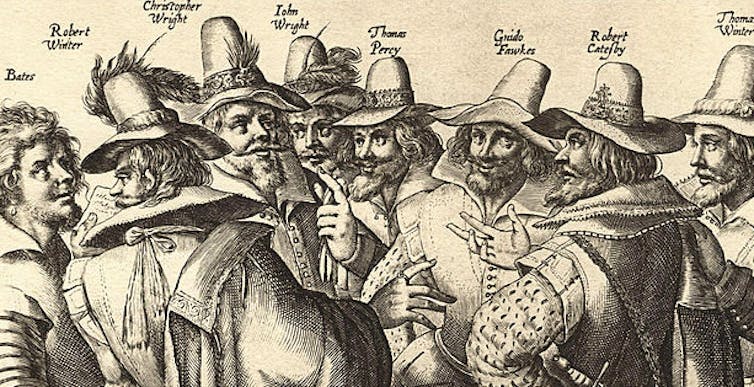

The second thing to be aware of is the Gunpower Plot . When Macbeth was first staged in 1606, England was reeling from the discovery of a nearly successful conspiracy to blow up parliament. If successful, the attempt would have killed the king and a large number of the nation’s ruling class, and triggered catastrophic civic disorder.

Read more: The Gunpowder Plot: torture and persecution in fact and fiction

Gunpowder, treason and plot

On 4 November 1605, Guy Fawkes was arrested. A letter tipping off a member of parliament had led to the discovery of a stash of barrels of gunpowder in a cellar under parliament. Under torture, Fawkes revealed the names of his Catholic conspirators.

The discovery of the plot was promoted as a defining moment of victory for the Protestant nation against its Catholic traitors within, and led to intensified persecution of Catholics across Europe.

The adage, don’t waste a crisis, seems to have been heeded by James. Even in its own moment, the event became a black and white moral fable, in which treachery was weeded out and punished with violence. The traitors were tortured and publicly executed. Their bodies were literally quartered.

How did Shakespeare’s play, first performed in 1606, engage with the Gunpowder Plot and the grisly punishment of its perpetrators?

On the surface, Shakespeare cashed in on the way the Gunpowder Plot had shocked the people of London. Fireworks, or “squibs”, were used at the opening of the play as special effects for the “thunder and lightning” called for in the script. It is easy to imagine the first audience jumping with terror and then telling friends to attend the next spectacular performance.

By inventing the witches, Shakespeare also sets up ambiguous, almost imaginary figures of evil who “melt into air”. Were these anything like the monsters that the trial of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators had created in the public imagination? Many understood the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot to be an act of supernatural preservation of their God-ordained ruler. A silver commemorative medal from 1605 bears the Latin inscription: “You [God], the keeper of James, have not slept.”

Tracing a parallel with this sensibility, Shakespeare borrows Banquo – a real 11th century person believed to be an ancestor of King James – from the historical Chronicles of Raphael Holinshed . His characterisation, deviating from that of Holinshed, puts King James, through association, on the side of right in the play.

Shakespeare’s story of Banquo, who is murdered on Macbeth’s orders but returns as a ghost, seems to shore up by supernatural intervention James’ right to the throne. That is, until we consider that the witches who prophesy that Banquo will be the father of kings are the same ones who predict Macbeth’s ascent to the crown.

Shakespeare’s play is unsettling. It provides a thought experiment. It teases out the moral ambiguities of a society whose members see others in black and white, while permitting shades of grey in themselves.

It is a society in which treachery is punished with sanctioned violence, but in which ambition paves the way to real power via both violence and treachery. It is the kingdom of Scotland riven by contending clans. It is England of 1606 reeling from the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot. It is our world of perpetual crisis.

Crisis appeals to the human imagination because it offers to suspend the rules by which we normally operate. Crisis can, as Macbeth shows, make moral compromises appeal as “the nearest way” to increased power. It can make brutal measures seem necessary to retain it.

Macbeth issues a warning for our times about the harm done to individuals and societies when they allow the will for power to drown out the inner voice of conscience.

- William Shakespeare

- Guide to the Classics

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Subject Coordinator in Cultural Studies

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 25, 2020 • ( 0 )

Macbeth . . . is done upon a stronger and more systematic principle of contrast than any other of Shakespeare’s plays. It moves upon the verge of an abyss, and is a constant struggle between life and death. The action is desperate and the reaction is dreadful. It is a huddling together of fierce extremes, a war of opposite natures which of them shall destroy the other. There is nothing but what has a violent end or violent beginnings. The lights and shades are laid on with a determined hand; the transitions from triumph to despair, from the height of terror to the repose of death, are sudden and startling; every passion brings in its fellow-contrary, and the thoughts pitch and jostle against each other as in the dark. The whole play is an unruly chaos of strange and forbidden things, where the ground rocks under our feet. Shakespear’s genius here took its full swing, and trod upon the farthest bounds of nature and passion.

—William Hazlitt, Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays

Macbeth completes William Shakespeare’s great tragic quartet while expanding, echoing, and altering key elements of Hamlet, Othello, and King Lear into one of the most terrifying stage experiences. Like Hamlet, Macbeth treats the consequences of regicide, but from the perspective of the usurpers, not the dispossessed. Like Othello, Macbeth centers its intrigue on the intimate relations of husband and wife. Like Lear, Macbeth explores female villainy, creating in Lady Macbeth one of Shakespeare’s most complex, powerful, and frightening woman characters. Different from Hamlet and Othello, in which the tragic action is reserved for their climaxes and an emphasis on cause over effect, Macbeth, like Lear, locates the tragic tipping point at the play’s outset to concentrate on inexorable consequences. Like Othello, Macbeth, Shakespeare’s shortest tragedy, achieves an almost unbearable intensity by eliminating subplots, inessential characters, and tonal shifts to focus almost exclusively on the crime’s devastating impact on husband and wife.

What is singular about Macbeth, compared to the other three great Shakespearean tragedies, is its villain-hero. If Hamlet mainly executes rather than murders, if Othello is “more sinned against than sinning,” and if Lear is “a very foolish fond old man” buffeted by surrounding evil, Macbeth knowingly chooses evil and becomes the bloodiest and most dehumanized of Shakespeare’s tragic protagonists. Macbeth treats coldblooded, premeditated murder from the killer’s perspective, anticipating the psychological dissection and guilt-ridden expressionism that Feodor Dostoevsky will employ in Crime and Punishment . Critic Harold Bloom groups the protagonist as “the culminating figure in the sequence of what might be called Shakespeare’s Grand Negations: Richard III, Iago, Edmund, Macbeth.” With Macbeth, however, Shakespeare takes us further inside a villain’s mind and imagination, while daringly engaging our sympathy and identification with a murderer. “The problem Shakespeare gave himself in Macbeth was a tremendous one,” Critic Wayne C. Booth has stated.

Take a good man, a noble man, a man admired by all who know him—and destroy him, not only physically and emotionally, as the Greeks destroyed their heroes, but also morally and intellectually. As if this were not difficult enough as a dramatic hurdle, while transforming him into one of the most despicable mortals conceivable, maintain him as a tragic hero—that is, keep him so sympathetic that, when he comes to his death, the audience will pity rather than detest him and will be relieved to see him out of his misery rather than pleased to see him destroyed.

Unlike Richard III, Iago, or Edmund, Macbeth is less a virtuoso of villainy or an amoral nihilist than a man with a conscience who succumbs to evil and obliterates the humanity that he is compelled to suppress. Macbeth is Shakespeare’s greatest psychological portrait of self-destruction and the human capacity for evil seen from inside with an intimacy that horrifies because of our forced identification with Macbeth.

Although there is no certainty in dating the composition or the first performance of Macbeth, allusions in the play to contemporary events fix the likely date of both as 1606, shortly after the completion and debut of King Lear. Scholars have suggested that Macbeth was acted before James I at Hampton Court on August 7, 1606, during the royal visit of King Christian IV of Denmark and that it may have been especially written for a royal performance. Its subject, as well as its version of Scottish history, suggest an effort both to flatter and to avoid offending the Scottish king James. Macbeth is a chronicle play in which Shakespeare took his major plot elements from Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1587), but with significant modifications. The usurping Macbeth’s decade-long (and largely successful) reign is abbreviated with an emphasis on the internal and external destruction caused by Macbeth’s seizing the throne and trying to hold onto it. For the details of King Duncan’s death, Shakespeare used Holinshed’s account of the murder of an earlier king Duff by Donwald, who cast suspicion on drunken servants and whose ambitious wife played a significant role in the crime. Shakespeare also eliminated Banquo as the historical Macbeth’s co-conspirator in the murder to promote Banquo’s innocence and nobility in originating a kingly line from which James traced his legitimacy. Additional prominence is also given to the Weird Sisters, whom Holinshed only mentions in their initial meeting of Macbeth on the heath. The prophetic warning “beware Macduff” is attributed to “certain wizards in whose words Macbeth put great confidence.” The importance of the witches and the occult in Macbeth must have been meant to appeal to a king who produced a treatise, Daemonologie (1597), on witch-craft.

The uncanny sets the tone of moral ambiguity from the play’s outset as the three witches gather to encounter Macbeth “When the battle’s lost and won” in an inverted world in which “Fair is foul, and foul is fair.” Nothing in the play will be what it seems, and the tragedy results from the confusion and conflict between the fair—honor, nobility, duty—and the foul—rank ambition and bloody murder. Throughout the play nature reflects the disorder and violence of the action. Opening with thunder and lightning, the drama is set in a Scotland contending with the rebellion of the thane (feudal lord) of Cawdor, whom the fearless and courageous Macbeth has vanquished on the battlefield. The play, therefore, initially establishes Macbeth as a dutiful and trusted vassal of the king, Duncan of Scotland, deserving to be rewarded with the rebel’s title for restoring peace and order in the realm. “What he hath lost,” Duncan declares, “noble Macbeth hath won.” News of this honor reaches Macbeth through the witches, who greet him both as the thane of Cawdor and “king hereafter” and his comrade-in-arms Banquo as one who “shalt get kings, though thou be none.” Like the ghost in Hamlet , the Weird Sisters are left purposefully ambiguous and problematic. Are they agents of fate that determine Macbeth’s doom, predicting and even dictating the inevitable, or do they merely signal a latency in Macbeth’s ambitious character?

When he is greeted by the king’s emissaries as thane of Cawdor, Macbeth begins to wonder if the first predictions of the witches came true and what will come of the second of “king hereafter”:

This supernatural soliciting Cannot be ill, cannot be good. If ill, Why hath it given me earnest of success Commencing in a truth? I am Thane of Cawdor. If good, why do I yield to that suggestion Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair And make my seated heart knock at my ribs, Against the use of nature? Present fears Are less than horrible imaginings: My thought, whose murder yet is but fantastical, Shakes so my single state of man that function Is smother’d in surmise, and nothing is But what is not.

Macbeth will be defined by his “horrible imaginings,” by his considerable intellectual and imaginative capacity both to understand what he knows to be true and right and his opposed desires and their frightful consequences. Only Hamlet has as fully a developed interior life and dramatized mental processes as Macbeth in Shakespeare’s plays. Macbeth’s ambition is initially checked by his conscience and by his fear of the unforeseen consequence of violating moral laws. Shakespeare brilliantly dramatizes Macbeth’s mental conflict in near stream of consciousness, associational fashion:

If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well It were done quickly. If th’assassination Could trammel up the consequence, and catch With his surcease, success: that but this blow Might be the be all and the end all, here, But here, upon this bank and shoal of time, We’d jump the life to come. But in these cases We still have judgement here, that we but teach Bloody instructions which, being taught, return To plague th’inventor. This even-handed justice Commends th’ingredients of our poison’d chalice To our own lips. He’s here in double trust: First, as I am his kinsman and his subject, Strong both against the deed; then, as his host, Who should against his murderer shut the door, Not bear the knife myself. Besides, this Duncan Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been So clear in his great office, that his virtues Will plead like angels trumpet-tongued against The deep damnation of his taking-off, And pity, like a naked new-born babe, Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubin, horsed Upon the sightless couriers of the air, Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye That tears shall drown the wind. I have no spur To prick the sides of my intent, but only Vaulting ambition which o’erleaps itself And falls on the other.

Macbeth’s “spur” comes in the form of Lady Macbeth, who plays on her husband’s selfimage of courage and virility to commit to the murder. She also reveals her own shocking cancellation of gender imperatives in shaming her husband into action, in one of the most shocking passages of the play:

. . . I have given suck, and know How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me. I would, while it was smiling in my face, Have plucked my nipple from his boneless gums And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn As you have done to this.

Horrified at his wife’s resolve and cold-blooded calculation in devising the plot, Macbeth urges his wife to “Bring forth menchildren only, / For thy undaunted mettle should compose / Nothing but males,” but commits “Each corporal agent to this terrible feat.”

With the decision to kill the king taken, the play accelerates unrelentingly through a succession of powerful scenes: Duncan’s and Banquo’s murders, the banquet scene in which Banquo’s ghost appears, Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking, and Macbeth’s final battle with Macduff, Thane of Fife. Duncan’s offstage murder contrasts Macbeth’s “horrible imaginings” concerning the implications and Lady Macbeth’s chilling practicality. Macbeth’s question, “Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood / Clean from my hand?” is answered by his wife: “A little water clears us of this deed; / How easy is it then!” The knocking at the door of the castle, ominously signaling the revelation of the crime, prompts the play’s one comic respite in the Porter’s drunken foolery that he is at the door of “Hell’s Gate” controlling the entrance of the damned. With the fl ight of Duncan’s sons, who fear for their lives, causing them to be suspected as murderers, Macbeth is named king, and the play’s focus shifts to Macbeth’s keeping and consolidating the power he has seized. Having gained what the witches prophesied, Macbeth next tries to prevent their prediction that Banquo’s descendants will reign by setting assassins to kill Banquo and his son, Fleance. The plan goes awry, and Fleance escapes, leaving Macbeth again at the mercy of the witches’ prophecy. His psychic breakdown is dramatized by his seeing Banquo’s ghost occupying Macbeth’s place at the banquet. Pushed to the edge of mental collapse, Macbeth steels himself to meet the witches again to learn what is in store for him: “Iam in blood,” he declares, “Stepp’d in so far that, should Iwade no more, / Returning were as tedious as go o’er.”

The witches reassure him that “none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth” and that he will never be vanquished until “Great Birnam wood to high Dunsinane hill / Shall come against him.” Confident that he is invulnerable, Macbeth responds to the rebellion mounted by Duncan’s son Malcolm and Macduff, who has joined him in England, by ordering the slaughter of Lady Macduff and her children. Macbeth has progressed from a murderer in fulfillment of the witches predictions to a murderer (of Banquo) in order to subvert their predictions and then to pointless butchery that serves no other purpose than as an exercise in willful destruction. Ironically, Macbeth, whom his wife feared was “too full o’ the milk of human kindness / To catch the nearest way” to serve his ambition, displays the same cold calculation that frightened him about his wife, while Lady Macbeth succumbs psychically to her own “horrible imaginings.” Lady Macbeth relives the murder as she sleepwalks, Shakespeare’s version of the workings of the unconscious. The blood in her tormented conscience that formerly could be removed with a little water is now a permanent noxious stain in which “All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten.” Women’s cries announcing her offstage death are greeted by Macbeth with detached indifference:

I have almost forgot the taste of fears: The time has been, my senses would have cool’d To hear a nightshriek, and my fell of hair Would at a dismal treatise rouse and stir As life were in’t. Ihave supp’d full with horrors; Direness, familiar to my slaughterous thoughts, Cannot once start me.

Macbeth reveals himself here as an emotional and moral void. Confirmation that “The Queen, my lord, is dead” prompts only the bitter comment, “She should have died hereafter.” For Macbeth, life has lost all meaning, refl ected in the bleakest lines Shakespeare ever composed:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow Creeps in this petty pace from day to day To the last syllable of recorded time; And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

Time and the world that Macbeth had sought to rule are revealed to him as empty and futile, embodied in a metaphor from the theater with life as a histrionic, talentless actor in a tedious, pointless play.

Macbeth’s final testing comes when Malcolm orders his troops to camoufl age their movement by carrying boughs from Birnam Woods in their march toward Dunsinane and from Macduff, whom he faces in combat and reveals that he was “from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripp’d,” that is, born by cesarean section and therefore not “of woman born.” This revelation, the final fulfillment of the witches’ prophecies, causes Macbeth to fl ee, but he is prompted by Macduff’s taunt of cowardice and order to surrender to meet Macduff’s challenge, despite knowing the deadly outcome:

Yet I will try the last. Before my body I throw my warlike shield. Lay on, Macduff, And damn’d be him that first cries, “Hold, enough!”

Macbeth returns to the world of combat where his initial distinctions were honorably earned and tragically lost.

The play concludes with order restored to Scotland, as Macduff presents Macbeth’s severed head to Malcolm, who is hailed as king. Malcolm may assert his control and diminish Macbeth and Lady Macbeth as “this dead butcher and his fiendlike queen,” but the audience knows more than that. We know what Malcolm does not, that it will not be his royal line but Banquo’s that will eventually rule Scotland, and inevitably another round of rebellion and murder is to come. We also know in horrifying human terms the making of a butcher and a fiend who refuse to be so easily dismissed as aberrations.

Macbeth Oxford Lecture by Emma Smith

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Plays

Macbeth Ebook pdf (8MB)

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Bibliography Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Character Study Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Criticism Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Drama Criticism , ELIZABEHAN POETRY AND PROSE , Essays Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Lady Macbeth , Lady Macbeth Character Study , Lady Macbeth Feminist Criticism , Literary Criticism , Macbeth , Macbeth Analysis , Macbeth Essays , Macbeth Guide , Macbeth Lecture , Macbeth Notes , Macbeth pdf , Macbeth Play Analysis , Macbeth Play Notes , Macbeth Play Summary , Macbeth Summary , Macbeth theme , Notes Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Plot Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Simple Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Study Guides Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Summary Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Synopsis Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , Themes Of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth , William Shakespeare

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Violence in Macbeth

Macbeth is a prime example of a violent Jacobean drama .

As the Elizabethan age gave way to the Jacobean era new young playwrights emerged. They were very much in tune with their sophisticated London audience, who delighted in the spectacle of sex and violence, so Jacobean plays became increasingly sexual and violent. Not only was there killing and wounding with swords and daggers, poisonings, stranglings, and torture, but also a great number of minor bloodcurdling acts of physical violence. In The Changeling by Middleton and Rowley , for example, De Flores, one of the most villainous psychopaths of the Jacobean stage, stabs a rival, Alonso, three times while his back is turned. He then spies a diamond ring on his victim’s finger. He tries but fails, to remove the ring so he just cuts off the finger and puts it in his pocket before disposing of the body.

Shakespeare wrote most of his plays during the reign of King James. He, of course, had been in tune with his audiences right from the beginning of his career, catering for their interest in history and humour and classical themes during Elizabeth’s reign. And now he was filling his theatres with plays as violent as those of the best of his fellow theatre writers. Cornwall, a character in King Lear , matches De Flores’ unthinkable act by pulling out Gloucester’s eyes, with the stage direction ‘he plucks out his eyes.’

With all that violence, all those blood-drenched stages, all those dead bodies, the shock value of such things would have been somewhat blunted – so what would shock a Jacobean audience? Nothing more than the brutal murder of a child on stage, which Shakespeare provides Macbeth .

There is nothing superficial about Shakespeare’s plays, though. Unlike some of his contemporaries, his violent plays were never about violence: when he used violence it was always in the pursuit of greater meaning and the violence was either a device for characterisation, a dramatic device to move the action forward, or something else quite profound. Indeed, he was titillating his audience, pulling them in to fill the seats but, as always with Shakespeare, he had the larger picture in mind.

If the brutal killing of Macduff’s young son is not there simply to satisfy the bloodthirsty taste of the audience then what was it about? We are used to that scene being there but try and imagine an audience seeing it for the first time. What a shock it must have been, given that most members of the audience had little children and the worst thing they would have been able to imagine would have been the murder of one of them. That scene has been familiar for four centuries but it still shocks when we see it on the stage.

The text of Macbeth is infused with blood: Shakespeare uses the word more than forty times. Putting it very simply, the play is about Macbeth’s ambition to be king (read some of the many Macbeth ambition quotes ) , and having trod a bloody path to realize that he now finds it to have been a hollow and empty enterprise. His attempt to cover up his route to the throne and simply to survive as king involves increasingly desperate acts of violence, and a lot more blood, as he sets about eliminating his opposition.

Macbeth, drenched in blood

Well, what about the murder of the child? This is where we see the master dramatist at work. Shakespeare’s plays are always manipulations of the audience’s emotions. At the beginning of Macbeth Shakespeare takes care to show them Macbeth as a great popular hero, loved by the king and respected and honored by the whole of Scotland. Shakespeare builds that in many ways. When Macbeth gets the idea of murdering Duncan and being elected king we follow him down that road as Shakespeare lets us into his mind with several soliloquies. We don’t see anything else. Macbeth is hesitant. He is still a good man, and we are basically on his side as there are no counter-arguments. We also see him as someone who wants to be king but shrinks from the act he has to commit to get there, but he is bullied and manipulated by Lady Macbeth and forced into it.

The point is that Shakespeare wants us to be there with Macbeth and so at this point, we are identifying with him and wanting him to win. When he kills Duncan it’s done offstage, and all we see is the blood on his hands and his sense of the horror of what he has done. It’s not particularly horrifying for the audience as we don’t see the killing: if Shakespeare had presented the assassination onstage we would have responded differently. But now Macbeth, crowned king, begins to be paranoid. Shakespeare moves us away from the inner life of Macbeth and we have scenes where other characters talk about his violent suppression of anyone he regards as a threat. We see the murder of his best friend, Banquo, and we hear of other atrocities. We are beginning to not like Macbeth so much but perhaps we can still sympathize with his position. But then we have a scene with an intelligent and endearing child, the son of Macduff, chatting with his mother, wondering what’s happened to his father, who has fled to England. Macbeth’s hired killers enter and begin their slaughter of Macduff’s family, on the orders of Macbeth, starting with the killing of the child. Directors of productions of the play are able to make that as brutal and bloody as they like.

This scene occurs right in the middle of the play – the apex of a structure that leads up to it, with the audience on Macbeth’s side, and follows it with our horror at what a villain he is, allowing us to rejoice in his defeat – another violent act in which he is beheaded, and his head displayed onstage. Shakespeare has manipulated our response and turned us completely. The scene depicting the brutal killing of a child takes us away from our support for Macbeth, leading us to an appalled sense of horror at his actions.

The scene is central in every way. The scenes immediately adjacent to it reflect each other, and it goes back to the beginning and forwards to the end of the play in that way, the scenes before that scene and after it reflecting each other at every step, all pointing to that supreme act of violence.

Shakespeare has adopted a structure that was used by the great writers of the past – Homer and all the books of the Old and New Testaments – in which the writers place their main point at the centre of the book and lead up to and away from it, everything pointing to that main, central point. And so, to Shakespeare, the murder of a child is the main point in Macbeth. This idea has not been generally explored by Shakespearean scholars but it suggests that Shakespeare may have seen ambition’s toll as far worse than simply the downfall of a single protagonist. But whether a member of an audience understood that or not was not as important in the early 17th century as the enjoyment of a paying audience derived from witnessing such shocking violence.

but that isnt the main focus of the play…

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

THEMES: VIOLENCE.

Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work. Explore the theme of violence in Macbeth

Macbeth is an extremely violent play.

Macbeth takes the throne of Scotland by killing Duncan and his guards, and tries to hold on to it by sending people to murder Banquo and Macduff’s family. Finally, he attempts to keep his reign by fighting Macduff. These might be the scenes of violence which are the most obvious in the play, but there are others throughout. Even before any characters are on stage, the theatre’s special effects of thunder and lightning, made with gunpowder, cannonballs and fireworks, would have sounded, and smelled, like a battle.

After the Witches, one of the first characters we see is the Captain, wounded in battle in Act I, scene 2. ‘What bloody man is that?’ asks Duncan, drawing attention to him. So when the play begins, the violence of the battle has already been happening. We are not told the causes of ‘the revolt’ but merely its ‘newest state’, that is, just the latest developments.

Those developments are described very graphically by the Captain, who tells us of Macbeth fighting Macdonwald:

‘Till he unseam’d him from the nave to th’ chops, And fix’d his head upon our battlements’ — Act I, scene 2

So, before we even meet Macbeth, he has sliced someone in half and chopped his head off as a prize. This might seem in character for the killer that we know Macbeth to be. The difference is that Macbeth’s actions here are celebrated by the king: ‘O valiant cousin! worthy gentleman!’. Later in the scene, Duncan sentences Cawdor to death. So what the play gives us is two different types of violence: one that is acceptable, and one that is criminal; the first holds Scotland together, the second tears it apart.

Violence is definitely linked to power in the play: the most successful king seems to be the one who is the best at killing. What this means is that the world of Macbeth is caught in a repeating circle of violence:

‘It will have blood, they say: blood will have blood’ — Act III, scene 4

is how Macbeth sums this up. It also leaks into the language of the characters, who make their points with bloody images. Perhaps the most unsettling one belongs to Lady Macbeth, who imagines a baby:

‘I would, while it was smiling in my face, Have pluck’d my nipple from his boneless gums, And dash’d the brains out’ — Act I, scene 7

She is trying to persuade Macbeth to keep his promise, but has to do so like this because the language of violence is the most convincing in Macbeth’s world.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER

What do you think about violence in the play?

In what ways is it similar to violence today?

How is it different?

Does the play offer alternatives to a cycle of violence?

OTHER RESOURCES YOU MIGHT LIKE

Get to know the characters we meet in Macbeth

Delve deeper into the language used in Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Context & themes

Everything you need to know about the context of Macbeth , as well as key themes in the play

Follow the production of Macbeth through weekly blogs & resources

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience from our website.

Carry on browsing if you're happy with this, or find out how to manage cookies .

Heroic Violence

Macbeth is shown to be a hero at the start because of his violent nature. He kills a traitor. Ironically, Macbeth ends up becoming the traitor that is murdered at the end of the play.

- The violent imagery describing Macbeth at the start of the play is honourable: his violence on the battlefield is for the king.

- He is praised and rewarded for killing a treacherous thane, Macdonald (sometimes spelt Macdonwald): ‘Till he unseam’d him from the nave to th’ chops / And fixed his head upon our battlements’ (1,2).

- Macbeth shows his courage and strength by cutting his enemy open from his navel (belly button) to his face.

- The violent verb ‘unseam’d’ emphasises how Macbeth opens him up.

- It all seems very fluid (free) in motion. This implies Macbeth is very strong and is unphased by horrifically killing another man.

Macdonald's head - message about treason

- Macbeth removes his enemy’s head and displays it from the battlements. This might seem grisly, but it has a clear purpose.

- When Shakespeare was writing, anyone sentenced to death for treason, such as Guy Fawkes after the failed Gunpowder Plot, would be hung, drawn and quartered (a horrible punishment of partial hanging, disembowelling and cutting of body into quarters) and their heads would be shown on pikes on Traitor’s Gate. This was the gateway prisoners would pass through as they entered the Tower of London.

- This was done to make sure people thought twice before acting against their king and country.

Macbeth's head

- At the end of the play, Macduff removes Macbeth’s head.

- Macduff seems to be displaying it as he asks them to look at it: ‘Behold where stands / the usurper’s cursed head’ (5,9).

- This moment makes Macbeth’s heroism at the start somewhat ironic – he was a hero for killing a man who seems to have been a traitor to the king. However, almost immediately after that, he himself becomes a traitor, soon murdering the king and taking over Scotland.

- This relates back to the witches’ statement: 'Fair is foul, and foul is fair' (1,1) – things and people are not always what they seem.

Heroic code

- The warriors fighting believed in the heroic code (defines how a noble person should act): it was honourable to die in battle.

- This is why Siward says that his son ‘parted well’ (5,9). The battles were bloody and violent, but participating and fighting, even dying, bravely was very honourable. It deserved praise.

- This is why Macbeth’s murder of King Duncan seems particularly evil – he killed him while he slept, without warning.

- He did not give Duncan a chance to meet him equally in battle.

Lady Macbeth - Violent Imagery

Lady Macbeth uses very violent imagery to persuade her husband to murder King Duncan. She tells him she would have bashed in the brain of her own baby if she had promised to do it: ‘I would, while it was smiling in my face, / Have plucked the nipple from his boneless gums, / And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn / As you have done to this’ (1,7).

Shocking (from a woman)

- This would have been very shocking to a Jacobean (during the reign of James I of England) audience.

- Lady Macbeth is a woman whose main purpose, according to the values of the time, would be to give birth to and nurture children. The language she uses is very vivid and violent.

'Plucked'

- The verb ‘plucked’ is simple, but devastating; it’s as if she casually removed the baby from the breast and broke the connection between them.

- In this sense, Lady Macbeth goes against nature by refusing to nurture her own child and, instead, describes the violent image of her murdering it.

'Boneless'

- The adjective ‘boneless’ reflects how young the child is.

- He doesn’t have teeth in his gums yet. This reminds the audience of how vulnerable the baby is and how Lady Macbeth does not seem to care – again, her careless attitude goes against nature, especially for women at the time the play was set.

'Dashed'

- Finally, the verb ‘dashed’ is a very aggressive one. It shows how she would have bashed in her baby’s head if she had promised to do it.

- She uses violence to try and show Macbeth how strong her commitment is to anything she promises to do.

- She is trying to show him he is a coward for going back on the plan.

- She uses an image of violence against the thing she cares most about – her baby. She does this to show him that she’d do anything to keep her word to him and to make him change his mind.

- In Lady Macbeth’s mind, this violent description shows her husband the extent she’d go to for him and, therefore, how much she loves him.

Murder and Violence

Violence leads to more violence in Macbeth . Macbeth murders the king and murders to protect his crown thereafter. He even orders for a child to be murdered.

Killing Duncan

- The violence of killing King Duncan is clear from the blood on Macbeth’s hands.

- King Duncan was sleeping. Macbeth was especially cowardly in the murder and he prevented him from a warrior’s death.

- Macbeth refers to his hands as ‘a sorry sight’ (2,2). This suggests that he has done something incredibly weak in murdering a sleeping man, and one who he was honour-bound (morally obliged) to serve and protect.

Other murders

- After King Duncan’s murder, Macbeth steps away from murdering others with his own hands. He prefers to send murderers to do this for him.

- This may suggest he is still ashamed of using violence against those who don’t deserve it.

- Alternatively, this could show that he cares so little about human life that he carelessly gives the job of murdering to other people – his victims do not deserve his attention.

Violence bringing violence

- Macbeth says after seeing Banquo’s ghost, ‘It will have blood they say: blood will have blood’ (3,4).

- This is a metaphor saying that once a violent act is committed, more violence will follow. This usually happens when a family tries to avenge (get revenge for) the first murder.

One murder after another

- After murdering King Duncan, Macbeth continues to kill others in an attempt to stop anyone else from taking his throne.

- He hires men to murder Banquo and his son.

- He hires men to murder Lady Macduff and her son.

- The guilt of murdering Duncan drives Lady Macbeth to suicide.

- The murder of Duncan, Lady Macduff, and her son causes Macduff to kill Macbeth.

Protecting the crown

- Macbeth will also stop at nothing to protect his crown. He punishes those disloyal to him, including women and children.

- He sends murderers to kill Banquo and his son, Fleance, who escapes.

- After Macduff leaves for England, Macbeth sends more murderers to kill his wife and children in their home.

Murdering children

- The murder of Macduff’s son is seen on stage: ‘he has killed me, mother’ (4,2).

- The murder of children is very violent and upsetting. Children are symbolic of innocence. They cannot protect themselves.

- Calling out to his ‘mother’ is very emotive (brings out feelings), because it reminds those watching of how young he is. This violence reflects how evil Macbeth has become.

1 Literary & Cultural Context

1.1 Context

1.1.1 Tragedy

1.1.2 The Supernatural & Gender

1.1.3 Politics & Monarchy

1.1.4 End of Topic Test - Context

2 Plot Summary

2.1.1 Scenes 1 & 2

2.1.2 Scene 3

2.1.3 Scenes 4-5

2.1.4 Scenes 6-7

2.1.5 End of Topic Test - Act 1

2.2 Acts 2-4

2.2.1 Act 2

2.2.2 Act 3

2.2.3 Act 4

2.3.1 Scenes 1-3

2.3.2 Scenes 4-9

2.3.3 End of Topic Test - Acts 2-5

3 Characters

3.1 Macbeth

3.1.1 Hero vs Villain

3.1.2 Ambition & Fate

3.1.3 Relationship

3.1.4 Unstable

3.1.5 End of Topic Test - Macbeth

3.2 Lady Macbeth

3.2.1 Masculine & Ruthless

3.2.2 Manipulative & Disturbed

3.3 Other Characters

3.3.1 Banquo

3.3.2 The Witches

3.3.3 Exam-Style Questions - The Witches

3.3.4 King Duncan

3.3.5 Macduff

3.3.6 End of Topic Test - Lady Macbeth & Banquo

3.3.7 End of Topic Test - Witches, Duncan & Macduff

3.4 Grade 9 - Key Characters

3.4.1 Grade 9 - Lady Macbeth Questions

4.1.1 Power & Ambition

4.1.2 Power & Ambition HyperLearning

4.1.3 Violence

4.1.4 The Supernatural

4.1.5 Masculinity

4.1.6 Armour, Kingship & The Natural Order

4.1.7 Appearances & Deception

4.1.8 Madness & Blood

4.1.9 Women, Children & Sleep

4.1.10 End of Topic Test - Themes

4.1.11 End of Topic Test - Themes 2

4.2 Grade 9 - Themes

4.2.1 Grade 9 - Themes

4.2.2 Extract Analysis

5 Writer's Techniques

5.1 Structure, Meter & Other Literary Techniques

5.1.1 Structure, Meter & Dramatic Irony

5.1.2 Pathetic Fallacy & Symbolism

5.1.3 End of Topic Test - Writer's Techniques

Jump to other topics

Unlock your full potential with GoStudent tutoring

Affordable 1:1 tutoring from the comfort of your home

Tutors are matched to your specific learning needs

30+ school subjects covered

Power & Ambition HyperLearning

The Supernatural

The Role of Violence in Shakespeare's Macbeth (Essay Sample)

Macbeth, written by the literary master Shakespeare, is a story full of tragedy, ambition, and suspense. However, a larger theme of violence encompasses and controls the story and its characters. Violence, playing an important role in the play, depicts Macbeth's degradation from an honorable soldier and thane into an evil and selfish king. As Derek Cohen says in Macbeth's Rites of Violence, “There is no peace in the play. Lurking behind every scene, every dialogue, every fantastic appearance or event, is the spectre of violence with death following in its wake.” (Cohen), Macbeth is wholly centered around violence playing an insurmountable role in the determination of Macbeth's morality. When the Three Witches, speaking in trochaic tetrameter, give paradox in the line “Fair is foul, and foul is fair: / Hover through the fog and filthy air” (Shakespeare 1.1.12-13), they give us the most prominent theme in Macbeth. Paradox, and the “fair is foul” theme, is used throughout multiple events in the play, yet is most present in the role of violence. As Macbeth gradually yields to more violence, he changes from an honorable, honest man who fought for a greater good into a corrupt, evil king who fights for his own gain. Violence throughout Macbeth is viewed as valiant, honorable, and rewarding at the start of the play. However, the honor in violence begins to distort as the play carries on, shifting to selfish and cruel intentions. Throughout Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the role of violence emphasizes the shifts in Macbeth’s moral compass and coincides with the theme “fair is foul, and fair is foul” by first being viewed as honorable, representing pathetic fallacy, and ending as a representation of evil.

At the start of the play, the role of violence is one of valor and honor, however this is distinctly different from its role of evil towards the end of Macbeth. When Macbeth returns from the first battle, he is greeted with congratulations and honor. He is rewarded for being a courageous and valiant soldier with a new thane title. The people of Scotland express pride and gratitude for Macbeth's violence in battle and reward him for being ruthless on the battlefront. Macbeth’s friends bare him the great news of his successes: “The king hath happily received, Macbeth, / The news of thy success, and when he reads / Thy personal venture in the rebels’ sight, / His wonders and his praises do contend / Which thine or his” (Shakespeare 1.3.87-91). At this point, Macbeth uses violence for the greater good of defending his country. In Shakespeare for Students: Critical Interpretations of Shakespeare’s Plays and Poetry states: “Macbeth encounters three witches who predict that he will become King of Scotland; these prophecies begin the process of awakening his personal ambition for power” (pg. 440). Macbeth's view of violence drastically alters towards the end of the play from one of honor and loyalty, to one of selfishness and treachery, and this change is depicted with the help of pathetic fallacy in Macbeth's surroundings.

Violence is reflected with pathetic fallacy and continuously present throughout the course of Macbeth in the weather, animals, and other characters. As Macbeth progresses, violence increases, and Macbeth grows eviler with each scene. Actkinson states in Enter Three Witches that “As Macbeth ascends to the throne, the court descends to violence and murder”. (Actkinson), further illustrating that Macbeth's increase in power corresponds to an increase in violence in Scotland. Macbeth's submission to violence and commitment increasingly heinous murders following the introduction of the three witches has an apparent negative effect on the weather and depicts a manifestation of evil in Scotland. As Macbeth's morals slip, the weather becomes stormy, and animals begin to act distressed, notably during the murder of King Duncan when Lady Macbeth says, “I heard the owl scream and the crickets cry” (2.2.15). Violence throughout the play also constitutes a disarray of the environment in Scotland and presents a grim, formidable mood with destruction: “The night has been unruly. Where we lay, / Our chimneys were blown down and, as they say, / Lamentings heard i’ th’ air, strange screams of death / .... Some say the Earth / Was feverous and did shake.” (Shakespeare 2.3.28-36). Shakespeare uses pathetic fallacy to attribute human qualities and emotions to nature, and violence encompasses a larger theme in Macbeth by affecting Scotland negatively. As Macbeth progressively turns to violence, Scotland's environment experiences stormy weather, disturbed animals, and desecrate natural disasters. Because the damaging violence in Macbeth corresponds heavily to pathetic fallacy in weather and animals, this shows that violence is necessary to the progress of the play and essential in explaining the turn and fall of Macbeth into total violence and evil.