8 Video Essays About Books That Will Change Your Perspective

Emily Martin

Emily has a PhD in English from the University of Southern Mississippi, MS, and she has an MFA in Creative Writing from GCSU in Milledgeville, GA, home of Flannery O’Connor. She spends her free time reading, watching horror movies and musicals, cuddling cats, Instagramming pictures of cats, and blogging/podcasting about books with the ladies over at #BookSquadGoals (www.booksquadgoals.com). She can be reached at [email protected].

View All posts by Emily Martin

BookTubers are out here making so much entertaining content about books, and yes, that includes video essays. Check out these eight highly entertaining video essays. Some are from BookTubers you already love, and some might be from BookTubers who are new to you (you’re welcome). Fair warning to book lovers: these video essays will make you rethink some of your favorite works of literature. You might never look at books like Twilight , The Green Mile , or, yes, even Prince Harry’s Spare the same way ever again. But get ready to get educated and have a little fun while you’re at it.

Twilight is a Psychological Thriller, Not A Love Story

Can you believe Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight is almost 20 years old? Where is my eye cream? I am feeling very old. If you’re like me and read this book back when it first came out, it might be time to go back and revisit this text. The story is not what you think it is. In fact, Shanspeare argues that Twilight isn’t a love story at all. It’s more of a psychological thriller. Do you agree? Watch this video and think about it. Then, be sure to check out Shanspeare’s other video essays, including one of her most recent ones: The Feminine Rage Pipeline . Good stuff!

White Authors Don’t Define What’s Scary

Real talk: I think about this video essay all the time. And it’s definitely changed the way I read critiques about thrillers by authors of color. In this video essay, Jesse on YouTube discusses thrillers by BIPOC authors and how they’re received differently than thrillers by white authors. The video mostly draws examples from When No One is Watching by Alyssa Cole, but Jesse also explains how this issue pertains to a lot of books by BIPOC authors and the way white people review them.

The Queer History of Loki (It’s Weirder Than You Think)

YouTuber Jessie Gender ‘s channel includes so many great video essays, mostly focusing on science fiction, fantasy, “nerd” culture, and how this medium is confronting issues of gender and sexuality. Check out this in-depth video essay Jessie did on comic book anti-hero Loki . Loki has become a queer icon, but why is the LGBTQ+ community resonating so much with this character? Watch the video to find out! This video explores Loki’s history, from Norse mythology, to his appearance in Marvel comics, to his portrayal in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

The Magical Negroes of Stephen King

Princess Weekes is not the first person to point out Stephen King’s problematic depiction of BIPOC characters. But this video essay is probably the best, most thorough explanation of “the magical negro” trope and the troubling way King deploys this trope in multiple works. Disclaimer: This YouTuber wants viewers to know that she is not calling Stephen King racist, and she’s actually a huge fan of the author. This video is a great example of how you can enjoy an author’s work while still critiquing it and wanting more from the stories you read. Vampire fans, be sure to also check out her video essay Why Are There So Many Confederate Vampires ?

Authors Behaving Badly Series

One of my favorite video essay series on YouTube has to be Authors Behaving Badly from Reads with Rachel . If you want to hear someone spill all of the literature tea, then you need to check out these videos. But beware: you might not be able to look at your favorite authors the same way ever again. Just take this video on Sarah J. Maas, for example, which confronts all of the author’s problematic behavior. And if you want to see Rachel take down a book bit by bit over the course of many hours (I know I did), watch her deep dive into Fourth Wing . Even if you really enjoyed Fourth Wing , it’s a fun watch.

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark: History of the Pale Lady

Love Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark ? Then you have to check out CZsWorld’s series of videos looking at the history of the stories in these books. I always found the pale lady incredibly creepy, so this is a great one to start with. But the channel also has videos about the history of the Jangly Man and Harold the Scarecrow . If you’ve read the Scary Stories books, then you know these characters, and their images probably haunt your nightmares. Now learn more about where they came from.

Medusa Then and Now: A Monster’s Feminist Reclamation?

Speaking of the history of monsters, here’s one we all know and love: Medusa. In this video essay, historian and author Jean of Jean’s Thoughts breaks down the story of Medusa, why she remains a pop culture icon, and how she has changed over the past thousands of years. Jean really knows her stuff, so if you want more video essays about mythology, she’s got you covered. For instance, here’s why Hades and Persephone aren’t the cute couple you think they are . Enjoy!

The Complicated Ethics of Ghostwriters and Celebrity Books

Okay, people love to hate on ghostwriting and celebrity memoirs. Maybe especially because so many ghostwritten celebrity books have become popular best-sellers over the past few years. But why do we hate on them so much when ghostwriting has been going on since the dawn of literary time? And are these books as bad as people make them out to be? Jack Edwards breaks it all down in this video essay.

Looking for more BookTube content? Same. Always. Here are 10 thriller BookTube accounts to follow . Or you can follow these Nonfiction BookTube accounts . Want to know more about BookTube and where it’s heading? Here’s the past, present and future of BookTube , according to BookTubers. Happy watching!

You Might Also Like

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69371508/rlinn_210504_ecl1082_YoutubeEssays.0.jpg)

Filed under:

- Masterpieces of Streaming

The video essays that spawned an entire YouTube genre

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The video essays that spawned an entire YouTube genre

Polygon’s latest series, The Masterpieces of Streaming , looks at the new batch of classics that have emerged from an evolving era of entertainment.

Like every medium before it, “video essays” on YouTube had a long road of production before being taken seriously. Film was undervalued in favor of literature, TV was undervalued in favor of film, and YouTube was undervalued in favor of TV. In over 10 years of video essays, though, there are some that stand out as landmarks of the form, masterpieces to bring new audiences in.

In Polygon’s list of the best video essays of 2020 , we outlined a taxonomy of what a video essay is . But time should be given to explain what video essays have been and where they might be going.

Video essays can be broken into three eras: pre-BreadTube, the BreadTube era, and post-BreadTube. So, what the hell is BreadTube? BreadTube, sometimes also called “LeftTube,” can be defined as a core group of high production value, academically-minded YouTubers who rose to prominence at the same time.

A brief history of video essays on YouTube

On YouTube, video essays pre-BreadTube started in earnest just after something completely unrelated to YouTube: the adoption of the Common Core State Standards Initiative (or, colloquially, just the “Common Core”). The Common Core was highly political, a type of hotly-contested educational reform that hadn’t been rolled out in decades.

Meanwhile, YouTube was in one of its earliest golden eras in 2010. Four years prior, YouTube had been purchased by Google for $1.65 billion in stock, a number that is simultaneously bonkers high and bonkers low. Ad revenue for creators was flowing. Creators like PewDiePie and Shane Dawson were thriving (because time is a flat circle). With its 2012 Original Channel Initiative , Google invested $100 million, and later an additional $200 million, to both celebrity and independent creators for new, original content on YouTube in an early attempt to rival TV programming.

This was also incentivized by YouTube’s 2012 public change to their algorithm , favoring watch time over clicks.

But video essays still weren’t a major genre on YouTube until the educational turmoil and newfound funds collided, resulting in three major networks: Crash Course in 2011 and SourceFed and PBS Digital Studios in 2012.

The BreadTube Era

With Google’s AdSense making YouTube more and more profitable for some creators, production values rose, and longer videos rose in prominence in the algo. Key creators became household names, but there was a pattern: most were fairly left-leaning and white.

But in 2019, long-time YouTube creator Kat Blaque asked, “Why is ‘LeftTube’ so white?”

Blaque received massive backlash for her criticisms; however, many other nonwhite YouTubers took the opportunity to speak up. More examples include Cheyenne Lin’s “Why Is YouTube So White?” , Angie Speaks’ “Who Are Black Leftists Supposed to Be?” , and T1J’s “I’m Kinda Over This Whole ‘LeftTube’ Thing.”

Since the whiteness of video essays has been more clearly illuminated, terms like “BreadTube’’ and “LeftTube” are seldom used to describe the video essay space. Likewise, the importance of flashy production has been de-emphasized.

Post-BreadTube

Like most phenomena, BreadTube does not have a single moment one can point to as its end, but in 2020 and 2021, it became clear that the golden days of BreadTube were in the past.

And, notably, prominent BreadTube creators consistently found themselves in hot water on Twitter. If beauty YouTubers have mastered the art of the crying apology video, video essayists have begun the art of intellectualized, conceptualized, semi-apology video essays. Natalie Wynn’s “Canceling” and Lindsay Ellis’s “Mask Off” discuss the YouTubers’ experiences with backlash after some phenomenally yikes tweets. Similarly, Gita Jackson of Vice has reported on the racism of SocialismDoneLeft.

We’re now in post-BreadTube era. More Black creators, like Yhara Zayd and Khadija Mbowe, are valued as the important video essayists they are. Video essays and commentary channels are seeing more overlap, like the works of D’Angelo Wallace and Jarvis Johnson .

With a history of YouTube video essays out of the way, let’s discuss some of the best of the best, listed here in chronological order by release date, spanning all three eras of the genre. Only one video essay has been selected from each creator, and creators whose works have also been featured on our Best of 2020 list have different works selected here. If you like any of the following videos, we highly recommend checking out the creators’ backlogs; there are plenty of masterpieces in the mix.

PBS Idea Channel, “Can Dungeons & Dragons Make You A Confident & Successful Person?” (October 10, 2012)

Many of the conventions of modern video essays — a charismatic quick-talking host, eye-grabbing pop culture gifs accompanying narration, and sleek edits — began with PBS Idea Channel. Idea Channel, which ran from 2012 to 2017 and produced over 200 videos, laid many of the blueprints for video essays to come. In this episode, host Mike Rugnetta dissects the practical applications of tabletop roleplaying games like Dungeons & Dragons . The episode predates the tabletop renaissance, shepherded by Stranger Things and actual play podcasts , but gives the same level of love and appreciation the games would see in years to come.

Every Frame a Painting, “Edgar Wright - How to Do Visual Comedy” (May 26, 2014)

Like PBS Idea Channel, Every Frame a Painting was fundamental in setting the tone for video essays on YouTube. In this episode, the works of Edgar Wright (like Shaun of the Dead and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World ) are put in contrast with the trend of dialogue-based comedy films like The Hangover and Bridesmaids . The essay analyzes the lack of visual jokes in the American comedian style of comedy and shows the value of Wright’s mastery of physical comedy. The video winds up not just pointing out what makes Wright’s films so great, but also explaining the jokes in meticulous detail without ever ruining them.

Innuendo Studios, “This Is Phil Fish” (June 16, 2014)

As documented in the 2012 documentary Indie Game: The Movie and all over Twitter, game designer Phil Fish is a contentious figure, to say the least. Known for public meltdowns and abusive behavior, Phil Fish is easy to armchair diagnose, but Ian Danskin of Innuendo Studios uses this video to make something clear: We do not know Phil Fish. Before widespread discussions of parasocial relationships with online personalities, Innuendo Studios was pointing out the perils of treating semi-celebrities as anything other than strangers.

What’s So Great About That?, “Night In The Woods: Do You Always Have A Choice?” (April 20, 2017)

Player choice in video games is often emphasized as an integral facet of gameplay — but what if not having a real choice is the point? In this video, Grace Lee of What’s So Great About That? discusses how removing choice can add to a game’s narrative through the lens of sad, strange indie game Night in the Woods . What can a game with a mentally ill protagonist in a run-down post-industrial town teach us about what choices really mean, and how is a game the perfect way to depict that meaning? This video essay aims to make you see this game in a new light.

Pop Culture Detective, “Born Sexy Yesterday” (April 27, 2017)

One of the many “all killer no filler” channels on this list, Pop Culture Detective is best known as a trope namer. One of those tropes, “Born Sexy Yesterday,” encourages the audience to notice a specific, granular, but strangely prominent character trait in science fiction and fantasy: a female character who, through the conceit of the world and plot, has very little functional knowledge of the world around her, but is also a smoking hot adult. It’s sort of the reverse of the prominent anime trope of a grown woman, sometimes thousands of years old, inhabiting the body of a child. When broken down, the trope is not just a nightmare, it’s something you can’t unsee — and you start to see it everywhere .

Maggie Mae Fish, “Looking For Meaning in Tim Burton’s Movies” (April 24, 2018)

Tim Burton is an iconic example of an outsider making art for other outsiders who question and push the status quo ... right? In Maggie Mae Fish’s first video essay on her channel, she breaks down how Burton co-opts the anticapitalist aesthetics of German expressionism (most obviously, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari ) to give an outsider edge to films that consistently, aggressively enforce the status quo. If you’re a die-hard Burton fan, this one might sting, but Jack Skellington would be proud of you for seeking knowledge. Just kidding. He’d probably want you to take the aesthetic of the knowledge and put it on something completely unrelated, removing it of meaning.

hbomberguy, “CTRL+ALT+DEL | SLA:3” (April 26, 2018)

Are you looking for a video essay with a little more unhinged chaos energy? Prepare yourself for this video by Harry Brewis, aka hbomberguy, analyzing the webcomic CTRL+ALT+DEL, and ultimately, the infamous loss.jpg. But this essay’s also more than that; it’s a response to the criticisms of analyzing pop culture, saying that sometimes art isn’t that deep, or that works can exist outside of the perspective of the creator. This video is infamous for its climax, which we won’t spoil here, but go in knowing it’s, at the very least, adjacent to not safe for work.

Folding Ideas, “A Lukewarm Defence of Fifty Shades of Grey” (August 31, 2018)

Speaking of not-safe-for-work, let’s talk about kink! Dan Olson of Folding Ideas has been creating phenomenal video essays for years. Highlighting “In Search of Flat Earth” as one of the best video essays in 2020 (and, honestly, ever) gives an opportunity to discuss his other masterpieces here: his three-part series dissecting the Fifty Shades of Grey franchise. This introduction to the series discusses specifically the first film, and it does so in a way that is refreshingly kink-positive while still condemning the ways Fifty Shades has promoted extremely unsafe kink practices and dynamics. It also analyzes the first film with a shockingly fair lens, giving accolades where they’re due (that cinematography!) and ripping the film to shreds when necessary (what the hell are these characters?).

ToonrificTariq, “How To BLACK: An Analysis of Black Cartoon Characters (feat. ReviewYaLife)” (January 13, 2019)

While ToonrificTariq’s channel usually focuses on fantastic, engaging reviews of off-kilter nostalgic cartoons — think Braceface and As Told By Ginger — takes this video to explain the importance of writing Black characters in cartoons for kids, and not just one token Black friend per show. Through the lens of shows like Craig of the Creek and Proud Family , ToonrificTariq and guest co-host ReviewYaLife explain the way Black characters have been written into the boxes and how those tropes can be overcome by writers in the future. The collaboration between the two YouTubers also allows a mix of scripted, analytical content and some goofy, fun back-and-forth and riffing.

Jacob Geller, “Games, Schools, and Worlds Designed for Violence” (October 1, 2019)

Jacob Geller ( who has written for Polygon ) has this way of baking sincerity, vulnerability, and so much care into his video essays. This episode is rough, digging into what level design in war games can tell us about the architecture of American schools following the tragic Sandy Hook shooting in 2012. It’s a video essay about video games, about violence, about safety, and about childhood. It’s a video essay about what we prioritize and how, and what that priority can look like. It’s a video essay that will leave you with deep contemplation, but a hungry contemplation, a need to learn and observe more.

Accented Cinema, “Parasite: Mastering the Basics of Cinema” (November 7, 2019)

2019 Bong Joon-ho cinematic masterpiece Parasite is filled to the brim with things to analyze, but Yang Zhang of Accented Cinema takes his discussion back to the basics. Focusing on how the film uses camera positions, light, and lines, the essay shows the mastery of details many viewers might not have noticed on first watch. But once you do notice them, they’re extremely, almost comically overt, while still being incredibly effective. The way the video conveys these ideas is simple, straightforward, and accessible while still illuminating so much about the film and remaining engaging and fun to watch. Accented Cinema turns this video into a 101 film studies crash course, showing how mastery of the basics can make a film such a standout.

Kat Blaque, “So... Let’s Talk About JK Rowling’s Tweet” (December 23, 2019)

In 2020, J. K. Rowling wrote her most infamous tweet about trans people, exemplifying a debate about trans rights and identities that is still becoming more and more intense today. Rowling’s tweet was not the first, or the most important, or even her first — but it was one of the tweets about the issue that gained the most attention. Kat Blaque’s video essay on the tweet isn’t really about the tweet itself. Instead, it’s a masterful course in transphobia, TERFs, and how people hide their prejudice against trans people in progressive language. In an especially memorable passage, Blaque breaks down the tweet, line by line, phrase by phrase, explaining how each of them convey a different aspect of transphobia.

Philosophy Tube, “Data” (January 31, 2020)

One of the most underrated essays in Philosophy Tube’s catalogue, “Data” explains the importance of data privacy. Data privacy is often easily written off; “I have nothing to hide,” and “It makes my ads better,” are both given as defenses against the importance of data privacy. In this essay, though, creator Abigail Thorn breaks traditional essay form to depict an almost Plato-like philosophical dialogue between two characters: a bar patron and the bar’s bouncer. It’s also somewhat of a choose-your-own-adventure game, a post- Bandersnatch improvement upon the Bandersnatch concept.

Intelexual Media, “A Short History of American Celebrity” (February 13, 2020)

Historian Elexus Jionde of Intelexual Media has one of the strongest and sharpest analytical voices when discussing celebrity, from gossip to idolization to the celebrity industrial complex to stan culture . Her history of American celebrity is filled to the brim with information, fact following fact at a pace that’s breakneck without ever leaving the audience behind. While the video initially seems like just a history, there’s a thesis baked into the content about what celebrity is, how it got to where it is today, and where it might be going—and what all of that means about the rest of us.

Princess Weekes, “Empire and Imperialism in Children’s Cartoons—a super light topic” (June 22, 2020)

This video by Princess Weekes (Melina Pendulum) starts with a bang — a quick, goofy song followed by a steep dive into imperialization and its effect on intergenerational trauma. And then, it connects those concepts to much-beloved cartoons for kids like Avatar: The Last Airbender , Steven Universe , and She-Ra and the Princesses of Power . Fans of shows like these may be burnt out on fandom discourse quickly saying, “thing bad!” because of how they view its stance on imperialization. Weekes, however, has always favored nuance and close reading. Her take on imperialization in cartoons offers a more complex method of analyzing these shows, and the cartoons that will certainly drum up the same conversations in the future.

Yhara Zayd, “Holes & The Prison-Industrial Complex” (July 7, 2020)

2003’s Holes absolutely rules, and Yhara Zayd’s video essay on the film shows why it isn’t just a fun classic with memorable characters. It’s also way, way more complex than most of us might remember. Like Dan Olson, Yhara Zayd appeared on our list of the best video essays of 2020, but frankly, any one of her videos could belong there or here. What makes this analysis of Holes stand out is the meticulous attention to detail Zayd has in her analysis, revealing the threads that connect the film’s commentary across its multiple interwoven plotlines. And, of course, there’s Zayd’s trademark quiet passion for the work she’s discussing, making this essay just as much of a close reading as it is a love letter to the film.

D’Angelo Wallace, “The Disappearance of Blaire White” (November 2, 2020)

D’Angelo Wallace is best known as a commentary YouTuber, someone who makes videos reacting to current events, pop culture, and, of course, other YouTubers. With his hour-long essay on YouTuber Blaire White, though, that commentary took a sharp turn into cultural analysis and introspection. For those unfamiliar with White’s work, she was once a prominent trans YouTuber known for her somewhat right-wing politics, including her discussion of other trans people. In Wallace’s video, her career is outlined — but so is the effect she had on her viewers. What is it about creators like White that makes them compelling? And what does it take for us to reevaluate what they’ve been saying?

Chromalore, “The Last Unicorn: Death and the Legacy of Fantasy” (December 3, 2020)

Chromalore is a baffling internet presence. With one video essay up, one single tweet, and a Twitter bio that simply reads, “just one (1) video essay, as a treat,” this channel feels like the analysis equivalent of seeing someone absolutely captivating at a party who you know you’ll never see again, and who you know you’ll never forget.

This video essay discusses themes of death, memory, identity, remorse, and humanity as seen through both the film and the novel The Last Unicorn . It weaves together art history and music, Christian iconography and anime-inspired character designs. It talks about why this film is so beloved and the effect it’s had on audiences today. It’s moving, deeply researched, brilliantly executed, and we will probably never see this creator again.

Khadija Mbowe, “Digital Blackface?” (December 23, 2020)

“Digital Blackface” is a term popularized by Lauren Michele Jackson’s 2017 Teen Vogue essay, “We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs.” The piece explains the prominence of white people using the images of Black people without context to convey a reaction, and Khadija Mbowe’s deep dive on the subject expands on how, and why, blackface tropes have evolved in the digital sphere. Mbowe’s essay involves a great deal of history and analysis, all of which is deeply uncomfortable. Consider this a content warning for depictions of racism throughout the video. But that discomfort is key to explaining why digital blackface is such a problem and how nonblack people, especially white people, can be more cognizant about how they depict their reactions online.

CJ the X, “No Face Is An Incel” (April 4, 2021)

Rounding out this list is a 2021 newcomer to video essays with an endlessly enjoyable gremlin energy that still winds up being some of the smartest, sharpest, and funniest discussions about pop culture. CJ the X, a human sableye , breaks down one of the most iconic and merch-ified Studio Ghibli characters, No Face, who is an incel. This is a video essay best experienced with no knowledge except its main thesis—that No Face is an incel—so you can sit back, be beguiled, be enraptured, and then be convinced.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22545776/TCL_square.png)

TCL’s 85” Class XL Collection

Prices taken at time of publishing.

TCL’s new XL collection creates a larger-than-life entertainment experience. From watching movies and shows to playing the hottest new game these 85” TVs come loaded with features to suit any entertainment needs.

- $2,999 at Amazon

- $2,999 at Best Buy

The Masterpieces of Streaming

TriQuarterly

Search form, an introduction to video essays.

The works in our winter suite are interested in process. These three new videos demonstrate how, like other literary genres, the “video essay” gets redefined by every new iteration. Like early examples of video art, each piece repurposes a technology to highlight the accidental art-experiences available within a utilitarian process.

In our first video, “Ars Poetica,” Kelly Slivka compresses the inherent audio/video qualities of digital composition—the sound of keys tapping, the flash of copy-paste, all the sensory layers of writing-aloud. While this project might serve as a document of what writing was like in the early digital age, it also demonstrates the various lives and “meanings” a poem briefly inhabits on its way to a final version. “Ars Poetica” has us thinking about poems as being always already in flux. As the audience watches Slivka compose, we begin to root for the writer to get each word right, to come toward a point of rest, a final utterance, even—and because—it won’t be their last.

Our second video, “The Center” by Annelyse Gelman has us eyeing the eerie potential for non-human entities to replicate or replace human jobs, relationships, and even literature. Like examples of video art that pushed the limits of early green screen technology, “The Center” repurposes face swap and text-to-voice in a savvy, uncanny pairing of poetry and digital media that brings out the specific resonances of the text. Gelman’s project nods to animal experiments involving cages with electrified flooring, centers and peripheries that implicate and confront the viewer: “Are you thinking about your own heartbeat?”

Using a style that sets high-quality footage to the pace of slow breathing, Allain Daigle’s “New Arctic” thinks about the future of our planet without using images of landscape. In this project, Daigle shows us a house being built from the inside: industrial lighting, radio waves, breaths that rise in parcels. He asks us to consider the changes “our skin doesn’t notice” that mean our children will “dream about icebergs,” because “the new Arctic,” of course, is an oxymoron.

The videos in this suite trick us into seeing three familiar technologies in unfamiliar ways. Each piece showcases the variety of formats, structures, and new media that today’s literary videos might take on.

Issue 155 Winter / Spring 2019

Next: , share triquarterly, about the author, sarah minor.

Sarah Minor is the author of Slim Confessions: The Universe as a Spider or Spit (Noemi Press 2021), Bright Archive (Rescue Press 2020), winner of the 2020 Big Other Nonfiction Book Award and The Persistence of the Bonyleg: Annotated from Essay Press. She is the recipient of the Barthelme Prize for Short Prose, an Individual Research Grant from the American-Scandinavian Foundation, an Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council, and fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center, the Hambidge Center for Creative Arts, and the Kenyon Writers' Workshop. Her essays have been collected in places like Best American Experimental Writing , Advanced Creative Nonfiction , and A Harp in the Stars. Minor holds an MFA from the University of Arizona and a PhD from Ohio University. She currently teaches as a Visiting Assistant Professor in the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program.

The Latest Word

What is a Video Essay? The Art of the Video Analysis Essay

I n the era of the internet and Youtube, the video essay has become an increasingly popular means of expressing ideas and concepts. However, there is a bit of an enigma behind the construction of the video essay largely due to the vagueness of the term.

What defines a video analysis essay? What is a video essay supposed to be about? In this article, we’ll take a look at the foundation of these videos and the various ways writers and editors use them creatively. Let’s dive in.

Watch: Our Best Film Video Essays of the Year

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

What is a video essay?

First, let’s define video essay.

There is narrative film, documentary film, short films, and then there is the video essay. What is its role within the realm of visual media? Let’s begin with the video essay definition.

VIDEO ESSAY DEFINITION

A video essay is a video that analyzes a specific topic, theme, person or thesis. Because video essays are a rather new form, they can be difficult to define, but recognizable nonetheless. To put it simply, they are essays in video form that aim to persuade, educate, or critique.

These essays have become increasingly popular within the era of Youtube and with many creatives writing video essays on topics such as politics, music, film, and pop culture.

What is a video essay used for?

- To persuade an audience of a thesis

- To educate on a specific subject

- To analyze and/or critique

What is a video essay based on?

Establish a thesis.

Video analysis essays lack distinguished boundaries since there are countless topics a video essayist can tackle. Most essays, however, begin with a thesis.

How Christopher Nolan Elevates the Movie Montage • Video Analysis Essays

Good essays often have a point to make. This point, or thesis, should be at the heart of every video analysis essay and is what binds the video together.

Related Posts

- Stanley Kubrick Directing Style Explained →

- A Filmmaker’s Guide to Nolan’s Directing Style →

- How to Write a Voice Over Montage in a Script →

interviews in video essay

Utilize interviews.

A key determinant for the structure of an essay is the source of the ideas. A common source for this are interviews from experts in the field. These interviews can be cut and rearranged to support a thesis.

Roger Deakins on "Learning to Light" • Video Analysis Essays

Utilizing first hand interviews is a great way to utilize ethos into the rhetoric of a video. However, it can be limiting since you are given a limited amount to work with. Voice over scripts, however, can give you the room to say anything.

How to create the best video essays on Youtube

Write voice over scripts.

Voice over (VO) scripts allow video essayists to write out exactly what they want to say. This is one of the most common ways to structure a video analysis essay since it gives more freedom to the writer. It is also a great technique to use when taking on large topics.

In this video, it would have been difficult to explain every type of camera lens by cutting sound bites from interviews of filmmakers. A voice over script, on the other hand, allowed us to communicate information directly when and where we wanted to.

Ultimate Guide to Camera Lenses • Video essay examples

Some of the most famous video essayists like Every Frame a Painting and Nerdwriter1 utilize voice over to capitalize on their strength in writing video analysis essays. However, if you’re more of an editor than a writer, the next type of essay will be more up your alley.

Video analysis essay without a script

Edit a supercut.

Rather than leaning on interview sound bites or voice over, the supercut video depends more on editing. You might be thinking “What is a video essay without writing?” The beauty of the video essay is that the writing can be done throughout the editing. Supercuts create arguments or themes visually through specific sequences.

Another one of the great video essay channels, Screen Junkies, put together a supercut of the last decade in cinema. The video could be called a portrait of the last decade in cinema.

2010 - 2019: A Decade In Film • Best videos on Youtube

This video is rather general as it visually establishes the theme of art during a general time period. Other essays can be much more specific.

Critical essays

Video essays are a uniquely effective means of creating an argument. This is especially true in critical essays. This type of video critiques the facets of a specific topic.

In this video, by one of the best video essay channels, Every Frame a Painting, the topic of the film score is analyzed and critiqued — specifically temp film score.

Every Frame a Painting Marvel Symphonic Universe • Essay examples

Of course, not all essays critique the work of artists. Persuasion of an opinion is only one way to use the video form. Another popular use is to educate.

- The Different Types of Camera Lenses →

- Write and Create Professionally Formatted Screenplays →

- How to Create Unforgettable Film Moments with Music →

Video analysis essay

Visual analysis.

One of the biggest advantages that video analysis essays have over traditional, written essays is the use of visuals. The use of visuals has allowed video essayists to display the subject or work that they are analyzing. It has also allowed them to be more specific with what they are analyzing. Writing video essays entails structuring both words and visuals.

Take this video on There Will Be Blood for example. In a traditional, written essay, the writer would have had to first explain what occurs in the film then make their analysis and repeat.

This can be extremely inefficient and redundant. By analyzing the scene through a video, the points and lessons are much more clear and efficient.

There Will Be Blood • Subscribe on YouTube

Through these video analysis essays, the scene of a film becomes support for a claim rather than the topic of the essay.

Dissect an artist

Essays that focus on analysis do not always focus on a work of art. Oftentimes, they focus on the artist themself. In this type of essay, a thesis is typically made about an artist’s style or approach. The work of that artist is then used to support this thesis.

Nerdwriter1, one of the best video essays on Youtube, creates this type to analyze filmmakers, actors, photographers or in this case, iconic painters.

Caravaggio: Master Of Light • Best video essays on YouTube

In the world of film, the artist video analysis essay tends to cover auteur filmmakers. Auteur filmmakers tend to have distinct styles and repetitive techniques that many filmmakers learn from and use in their own work.

Stanley Kubrick is perhaps the most notable example. In this video, we analyze Kubrick’s best films and the techniques he uses that make so many of us drawn to his films.

Why We're Obsessed with Stanley Kubrick Movies • Video essay examples

Critical essays and analytical essays choose to focus on a piece of work or an artist. Essays that aim to educate, however, draw on various sources to teach technique and the purpose behind those techniques.

What is a video essay written about?

Historical analysis.

Another popular type of essay is historical analysis. Video analysis essays are a great medium to analyze the history of a specific topic. They are an opportunity for essayists to share their research as well as their opinion on history.

Our video on aspect ratio , for example, analyzes how aspect ratios began in cinema and how they continue to evolve. We also make and support the claim that the 2:1 aspect ratio is becoming increasingly popular among filmmakers.

Why More Directors are Switching to 18:9 • Video analysis essay

Analyzing the work of great artists inherently yields a lesson to be learned. Some essays teach more directly.

- Types of Camera Movements in Film Explained →

- What is Aspect Ratio? A Formula for Framing Success →

- Visualize your scenes with intuitive online shotlist software →

Writing video essays about technique

Teach technique.

Educational essays designed to teach are typically more direct. They tend to be more valuable for those looking to create art rather than solely analyze it.

In this video, we explain every type of camera movement and the storytelling value of each. Educational essays must be based on research, evidence, and facts rather than opinion.

Ultimate Guide to Camera Movement • Best video essays on YouTube

As you can see, there are many reasons why the video essay has become an increasingly popular means of communicating information. Its ability to use both sound and picture makes it efficient and effective. It also draws on the language of filmmaking to express ideas through editing. But it also gives writers the creative freedom they love.

Writing video essays is a new art form that many channels have set high standards for. What is a video essay supposed to be about? That’s up to you.

Organize Post Production Workflow

The quality of an essay largely depends on the quality of the edit. If editing is not your strong suit, check out our next article. We dive into tips and techniques that will help you organize your Post-Production workflow to edit like a pro.

Up Next: Post Production →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

I wish I could've submitted video essays instead of term papers back in film school. It's such a digestible form to learn and discover new ideas. And it looks like it'd be way more fun than writing a paper and adjusting all the margins and period sizes to hit the page count minimum.

2 big questions- What about copyright claims from the rightsholders/studios of all the movie clips that are going into these "essays" ?

How does one avoid be flagged by YouTube and having the work being taken down?

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- How to Get a Film Permit — A Step-by-Step Breakdown

- How to Make a Storyboard: Ultimate Step-by-Step Guide (2024)

- VFX vs. CGI vs. SFX — Decoding the Debate

- What is a Freeze Frame — The Best Examples & Why They Work

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- 100 Facebook

- 0 Pinterest

The Video Essay: Celebrating an Exciting New Literary Form

- Student Experience

- Weinberg College

EVANSTON, Ill. --- TriQuarterly, Northwestern University’s celebrated literary journal that moved to an online format three years ago, is among the leading literary outlets of the video essay, an exciting new literary form.

"Today's digital technology gives writers unprecedented creative freedom," said Northwestern faculty member John Bresland, who curates the online journal’s video essays. An award-winning essayist working in video, radio and print, he equates the impact of 21st century technology on creativity to the invention of the printing press.

TriQuarterly, an international journal of writing, art and cultural inquiry, is part of Northwestern's degree program in creative writing, one of the nation's few part-time graduate writing programs. The latest issue of the magazine is twice the usual size, and it features a piece by noted author Ron Carlson as well.

See the new Summer/Fall 2013 issue of TriQuarterly online.

Writers of every genre who have composed on the page for decades -- novelist Bill Roorbach, essayist and Northwestern faculty member Eula Biss, poet Joe Wenderoth -- now also author works for the screen. Variations of this fast-emerging form of expression are taught in institutions of higher education across the country.

When Bresland surveyed the curricula of 30 major universities, he found nearly all offered classes similar to video essay courses he teaches in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and School of Continuing Studies. But what he calls video essay, another university might label "experimental media," "multimedia storytelling" or "writing with video."

That lack of uniformity reminds Bresland that turn-of-the-century cars were once called horseless carriages. "In 1885, we could only name this invention with familiar terms -- part horse, part buggy -- though clearly it was a radically new category that reordered the landscape," he said.

As today’s literary landscape is reordered by digital technology, TriQuarterly is embracing not just the video essay but a form of visual poetry called “cinepoetry,” a term borrowed from avant-garde photographer Man Ray. When TQ’s latest edition launches July 15, it will include a suite of five video essays and “cinepoems.”

Bresland’s personal site is jam-packed with video essays and writings about the new genre, including his highly influential “On the Origin of the Video Essay.” We talked with Bresland and asked him to expand on this revolutionary literary development.

How are mobile technologies revolutionizing the essay?

The screen of an iPad, for example, isn’t just a substitute for paper. It’s a canvas, a movie screen, an animation studio, a keyboard, a guitar, a microphone, a mixing board. The mobile devices we now use to collect our thoughts and memories don’t care whether we compose using words or images or sounds or all three. I believe the act of writing will always be, as writer Don DeLillo describes it, a concentrated form of thinking. But I also believe that fewer authors in the years ahead will choose to stop at the printed word.”

How do your students respond to this new literary form?

They go bright-eyed when you tell them writing doesn’t mean strictly words on a page. Most own a mobile device capable of acquiring video and sound. They delight in making sense of their world using the full arsenal of sensory input -- image, text, sound, voice. Not that it’s all wine and roses. I think most students realize, in the end, that no matter the medium, the heavy lifting of real thinking can’t be avoided.

Where is the video essay appearing?

Today I know of about a dozen literary journals that feature video essays and poems; 10 years ago there were none. I believe Blackbird and Ninth Letter were the first to realize the possibilities of a new kind of literature conveyed with image and sound, yet still had language at its core. Press Play is doing some thrilling work in the form, perhaps altering the rules of engagement between critic and film. TriQuarterly has featured video essays for 18 months.

Can you describe some the video essays or cinepoems that have appeared in TQ?

One of my favorites is Dinty W. Moore’s “ History ." Moore is an accomplished essayist who I knew could take great photographs but had never before worked in video. “History” is a memoir assembled from the faces of strangers he photographed in Scotland. It’s just a moving, gorgeous work.

TriQuarterly often features the still image in video essays. Angela Mears’ “ You Are Here ” and Bill Roorbach’s “ Starflower ” are short, brilliant essays built around a single still, and intense meditations likely to alter the viewer’s relationship to that image.

Kristen Radtke’s “ That Kind of Daughter ” is another great video essay. Visually it’s animated as a cut-out, one of the oldest animation techniques there is, just flat shapes arranged within a frame. But the text is so good and so densely lyrical and personal that it takes your breath away.

I also really love “ Wolfvision ” by Robin Schiff, who recently had a poem in The New Yorker, and Nick Twemlow. Assembled from Schiff’s text and from video that Twemlow gleaned from YouTube, “Wolfvision” is a haunting and beautiful essay, if it’s an essay. I do think the video essay lends itself to poetry, often skirting the line separating these two genre categories, if such a line really exists.

Are there other subgenres of the video essay?

There are at least two that have been getting a lot of attention the past couple years. One, which tends to go viral -- no doubt because it’s such a pleasure to experience -- is the video essay made up entirely of clips from previously released films, often held together and enriched by a sustained voiceover track. A wonderful recent work by Kevin B. Lee, called “ The Spielberg Face ” is a wall-to-wall compilation of reaction shots from the famous director’s body of work -- full of moments like the one in “Jaws” when Sheriff Brody first sees the shark, right before he utters the greatest line in the history of deadpan.

Aaron Aradillas and Matt Zoller Seitz have consistently produced compulsively watchable, insightful video essays about the credit sequences of David Fincher films, say, or “Rocky III,” as a test-bed for the popular films of the 1980s that followed it. What’s key is that critics have found a new venue for talking about film that’s not on the page -- their voices overlay the films themselves. It’s the perfect match of subject and form. Before the advent of online video in 2006 or so, this never would have been possible.

Another subgenre popping up all over academia is a hybrid of the personal essay and the old-school academic essay. A few years ago, Tufts University invited applicants to submit video essays that said “something about you.” Some 1,000 applicants took up the challenge. On the strength of Tufts’ video essay buzz, the number of applicants surged to its highest level in a generation. And now there’s not an admissions dean in America who hasn’t taken note. Dartmouth’s dean of admissions told National Public Radio that there’s no stopping video: “It’s the language of this generation.” As more and more media savvy students enter the academy, more teachers are compelled to speak that language.

Are there already “masters” of the video essay?

I’ve always loved Agnes Varda, who looks like this nice old French lady but, in fact, makes fierce essays for the screen. Her best might be “The Gleaners and I,” which came out in 2000 and caused something of a sensation in France and was popular here, too. Maybe we’re hungry for films that make us do more than “feel” -- we want to think, too, and we want to act on our convictions.

Chris Marker’s 1983 “Sans Soleil” is another classic film essay that, like any great work of art, seems to change as we change. But the greats don’t all have French passports. Ross McElwee has been releasing personal film-essays for decades -- “Time Indefinite” in 1993 and “Bright Leaves” in 2003 are among my favorites. What these filmmakers have in common is a knack for making smart, literate films that invite the viewer to co-create meaning. Most films today don’t leave any room for the viewer’s imagination. The smallness of the video essay, the fact that it tends to be the work of a single author or just one or two collaborators, can result in a work that’s less interested in a commercial payoff and more interested in asking difficult questions of others and of ourselves.

Editor’s Picks

This algorithm makes robots perform better

‘the night watchman’ named next one book selection, six northwestern faculty elected to american academy of arts and sciences, related stories.

The childhood of Hans Christian Andersen explored in musical at Northwestern University

Northwestern academy supports evanston students, trethewey named to the academy of american poets.

CFP: Literature and the Video Essay. Researching and Teaching Literature Through Moving Images

Editors: Adriana Margareta Dancus (University of South-Eastern Norway) and Alan O’Leary (Aarhus University)

This special issue explores how the video essay can function as an academic and pedagogic resource in the study and teaching of literature.

Literature and literature instruction are central components in the language subjects. In this special issue, we use the term ‘literature’ in a broad sense to encompass narratives in different genres and media, including picture books, comics, feature and documentary films, narrative apps, and computer games with an intrinsic aesthetical value. Didactic perspectives on literature encompass questions about why and how to teach literature as well as what literary texts to choose from in the language subjects. Further, we adopt a ‘performative’ approach to research whereby the video essay is conceived as a form that generates new theoretical and analytical insights.

Contributors will produce own video essays (5-12 minutes) accompanied by an academic guiding text between 1000-1500 words that fleshes out the relevance of the topic, positions the video essay in a larger academic context, and provides critical reflections on the process of making the video essay.

We welcome contributions in English, Danish, Norwegian or Swedish.

Abstracts (300 words) and a one page-mood board which visualizes the project should be sent to [email protected] by May 31, 2023.

Why the video essay in literary studies?

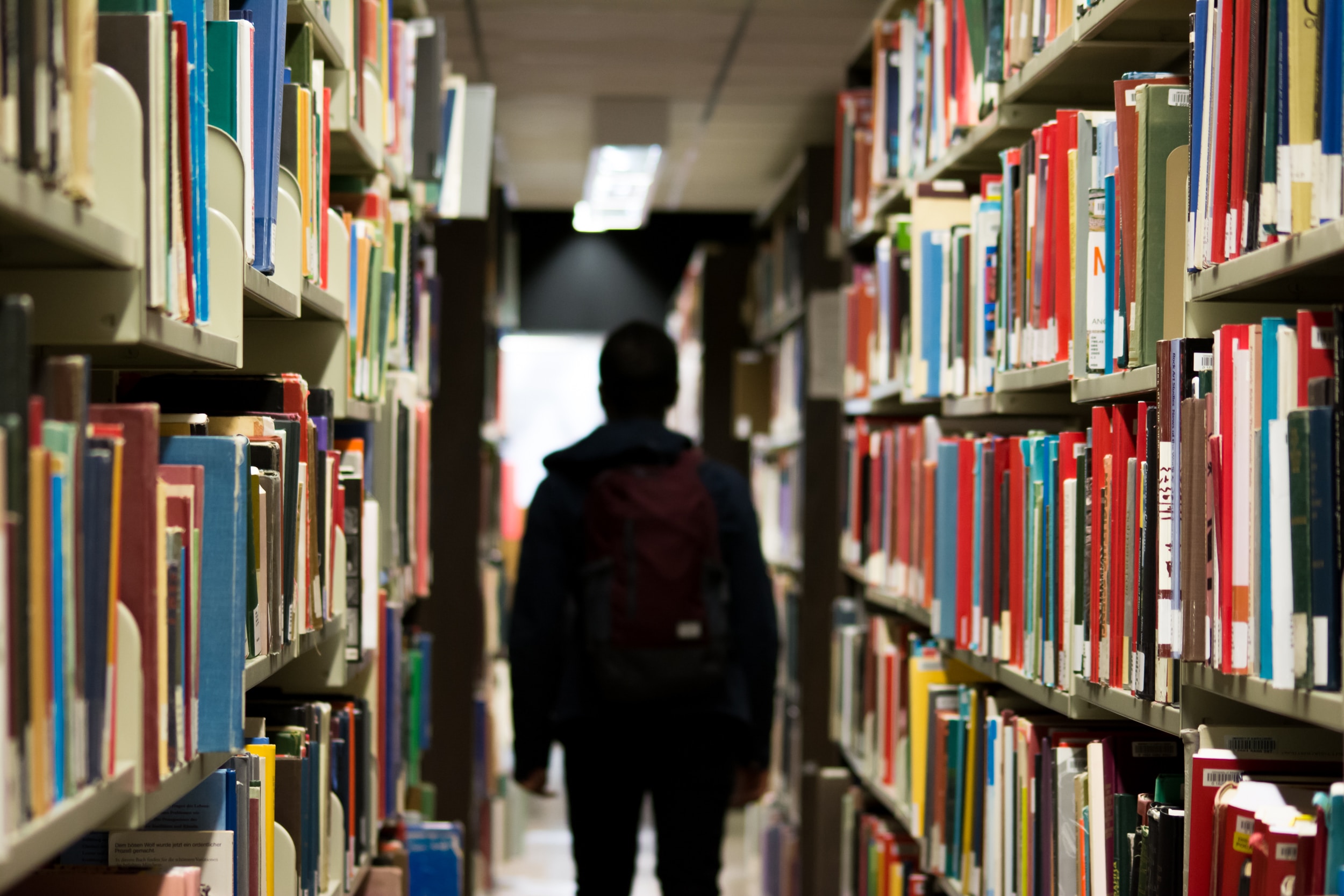

Since its very inception, the audiovisual has always struck a core with children and youth. Young generations who grow up in the digital age are both avid consumers and producers of audiovisual content. What can the audiovisual afford the teaching of literature and how does the audiovisual impact literary scholarship in the digital age? These questions are important to explore if we keep in mind the following paradox facing Nordic educational systems, especially the teaching of language subjects in Nordic schools. On the one hand, statistics show that Nordic children and youth spend significant amounts of time on social media and gaming, while the desire to read literature, as well as the amount of time spent on reading for pleasure, enjoyment, and meaningful cultural experiences, drops significantly with age, particularly among boys (Hansen et. al, 2022; Ipsos, 2022; Swedish Ministry of Culture, 2020). On the other hand, a consistent body of scholarship shows how reading literature is important for the development of critical thinking, democratic skills, and emotional literacy, to name a few (see Andersen, 2011; Nussbaum, 2016; Tørnby, 2020). In Norway, the educational reform from 2020 seeks to address this paradox by promoting a combination of formal, contextual, and interdisciplinary pedagogical approaches that encourage an aesthetic and critical engagement with literature (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training n.d.).

Parallel to these developments, the video essay has gained academic terrain in the last decade. [In]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies is the first peer-reviewed academic journal exclusively dedicated to videographic film studies, and an increasing number of academic journals publish video essays in special issues or independently. Most scholarly video essays produced today spring out of film, media, and game studies. Scholars in these fields praise this format for its capacity to rejuvenate and enhance academic film and TV criticism, incite critical cinephilia, make film students focus on the conceptual challenges and poetic possibilities of digital technology, and afford important reflections on the balance between poetic and explanatory modes of knowledge production (see Grant 2013, 2016; Keathley 2011, 2012; Keathley et al. 2019; Lavik 2012). Christian Keathley (2011), a founding editor of [in]Transition together with Catherine Grant and others, argues that the best video essays are marked by a unique combination: “a simultaneous faithfulness to the object of study and an imaginative use of it” (183). Grant (2013), who over the years has produced a significant amount of video essays, further underlines that the video essay is not about the translation of written film studies into audiovisual ones, but an attempt to create ontologically new scholarly forms that can live alongside traditional scholarly writing such as articles or monographs.

‘How’ the video essay in literary studies?

In a literary context, the video essay encourages an intimate, exploratory, and performative approach to literary studies that can engage with the expectations of young generations who grow up with access to the Internet and advanced portable digital devices. Most importantly, the video essay can inspire new ways of doing academic literary criticism and teaching literature in the digital age.

Relevant inquiries include, but are not limited to:

- How can the video essay afford presentation and learning of complex literary phenomena?

- What possibilities lie in the “showing” and “moving” of literature through techniques such as juxtaposition, superimposition, split screen, fast and slow motion, pausing, zooming or mixing sound, etc.?

- What kind of literary knowledge is produced when digital skills are put in the service of making video essays about literature?

- How is the video essay suited to the fleshing out of and engagement with the multisensory and affective impact of literary texts?

- What kinds of collaborations and collaborative forms of learning does the video essay encourage in literary studies?

- How can the video essay contribute to interdisciplinarity in literary studies?

- How does the video essay allow the exploration of literary theory centered around notions of authorship, genre, adaptation, and intertextuality?

- What can the practice-based methods of the video essay offer scholars and students of literature?

- How, and to what extent, can video essay-making help to develop a creative-critical competence in practitioners and students?

Guest editors:

Adriana Margareta Dancus is Professor of Norwegian at the University of South-Eastern Norway. Her research focuses on the affective investments afforded by contemporary Nordic cinema and literature and vulnerability as a resource. Dancus is the author of Exposing Vulnerability: Self-Mediation in Scandinavian Films by Women (Intellect/The University of Chicago Press 2019) and co-editor of Vulnerability in Scandinavian Art and Culture (Palgrave McMillan 2020) and Litteratur og sårbarhet (Universitetsforlaget 2021).

Alan O’Leary is Associate Professor of Film and Media in Digital Contexts at Aarhus University, Denmark, and Visiting Researcher in the Centre for World Cinemas and Digital Cultures, University of Leeds, UK. He has published video essays in [in]Transition and 16:9 and his most recent book is a study of the 1966 postcolonial film classic The Battle of Algiers ( Mimesis International, 2019 ). He is working on a videographic ‘monograph’ on the poetics of videographic criticism and his ‘ Workshop of Potential Scholarship: Manifesto for a parametric videographic criticism ’ was published in NECSUS in 2021.

Contributors and forms of collaboration :

Scholars in the fields of literature, art, film, TV, media, computer games, education and education research are invited to submit contributions to this special issue.

To foster an academic community around the video essay as form of research and teaching in literary studies, we structure submissions in four phases, with submission two and three being followed by a digital work-in-progress seminar in which we discuss our projects as a group together with the editorial team:

- Abstracts (300 words) and one page-mood board which visualizes the project - Rough cut of video essay - Fine cut of video essay and first draft of academic guiding text - Final cut of video essay and final draft of academic guiding text

The exacts dates for the work-in-progress seminars will be communicated to authors well in advance.

Guidelines for the video essay and the guiding text:

The video essay and the guiding text will be reviewed together according to the following criteria:

- Originality: the project makes an important and innovative contribution to knowledge and understanding - Significance: the project expands the range and depth of existing research - Rigor: coherence of aesthetic means and epistemic goals and/or clear arguments, precise methodology, powerful analysis, good citation practices (of written and audio-visual sources), follows ethical guidelines for research in the humanities - Technical and stylistic execution: good sound quality, cinematography, editing and text/typography that serve the purpose of the project

While the co-editors cannot support the technical development of the video essay, we use the work-in-progress seminars to advise on the aesthetic and conceptual development of the piece.

The final cut of the video essay is handed in as a separate .mp4- video-file. The guiding text is handed in a Word-file according to the house style guide of the journal.

Working timetable: 31 MAY 2023: Submission of abstracts and mood board JUNE 2023: Individual response to authors of abstract SEPTEMBER 2023: Rough cut of the video essay OCTOBER 2023: Work-in-progress seminar: Discuss rough cuts DECEMBER 2023: Fine cut of the video essays and first draft of the academic guiding text JANUARY 2024: Work-in-progress seminar: Discuss fine cut and first draft MARCH 2024: Final cut of video essay and final draft of academic guiding text MAY 2024: Individual feedback from peer reviewers JULY 2024: Submit revised video essays and academic guiding text after the peer review FALL 2024: Publication expected

Cited works and recommended readings: Andersen, P.T. (2011). Hva skal vi med skjønnlitteraturen i skolen?. Norsklæraren , 2(11), 15–22.

Grant, C. (2013). How long is a piece of string? On the Practice, Scope and Value of Videographic Film Studies and Criticism. The Audiovisual Essay. https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/audiovisualessay/frankfurt-papers/catherine-grant/ Grant, C. (2016). The audiovisual essay as performative research. NECSUS . https://necsus-ejms.org/the-audiovisual-essay-as-performative-research/.

Hansen, S.R., T.I. Hansen & M. Pettersson. (2022). Børn og unges læsning 2021 . Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Ipsos. (2022). Barn&Ungdom 2022 – Målgruppe mellom 8 og 19 år. Ipsos Barn og ungdomsundersøkelser. https://www.ipsos.com/nb-no/barnungdom-2022-malgruppe-mellom-8-og-19-ar.

Keathley, C. (2011). La caméra-stylo: Notes on Video Criticism and Cinephilia. In A. Clayton & A. Klevan (Eds.), The Language and Style of Film Criticism (p. 176-191). Routledge.

Keathley, C. (2012). Teaching the Scholarly Video. Frames, 1(1). https://framescinemajournal.com/article/teaching-the-scholarly-video/.

Keathley, C., J. Mittell & C. Grant. (2019). The Videographic Essay: Practice and Pedagogy. http://videographicessay.org/works/videographic-essay/index

Lavik, E. (2012). The Video Essay: The Future of Academic Film and Television Criticism. Frames, 1(1). http://framescinemajournal.com/article/the-video-essay-the-future/

Learning on Screen. (2020). Introductory Guide to Video Essays. https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/guidance/introductory-guide-to-video-essays/.

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (n.d.). Core Curriculum – Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2016). Litteraturen etikk – følelser og forestillingsevne. Oslo: Pax forlag.

Swedish Ministry of Culture (2020). Barns og ungas läsing (Skr. 2020/21:95). Government of Sweden. https://www.regeringen.se/496374/contentassets/83baa2be54344a508317cbd4738c1058/barns-och-ungas-lasning-skr.-20202195.pdf The Cine-files. (2014). Special Issue on Video Essay. http://issue7.thecine-files.com/.

The Cine-files. (2020). Special Issue on the scholarly video essay. http://www.thecine-files.com/issue15-position-papers/.

Tørnby, H. (2020). Picturebooks in the Classroom. Perspectives on life skills, sustainable development and democracy & citizenship. Fagbokforlaget.

Example video essays and collections:

This selection is intended to give a sense of some of the different registers, structures and approaches adopted by video essayists.

• Ariel Avissar (ed.), TV Dictionary. Vimeo showcase. https://vimeo.com/showcase/8660446

· Ariel Avissar and Evelyn Kreutzer (eds.), Once Upon A Screen vol. 2 (part 1), [in]Transition 9:3 (2022). http://mediacommons.org/intransition/journal-videographic-film-moving-image-studies-93-2022

· Johannes Binotto, Practices of Viewing. Vimeo showcase. https://vimeo.com/showcase/9086821

· Stephanie Brown, ‘Desktop Documentary and the Practice of Everyday Life’ (2021). https://videos.files.wordpress.com/iIRJ7qk5/stephaniebrowndesktopdoc_mov_hd.mp4

· Elisabeth Brun, ‘3xShapes of Home’ (2020). Screenworks 11:1 (2021). https://screenworks.org.uk/archive/volume-11-1/thinking-through-form

· Allison De Fren, ‘Fembot in a Red Dress’. [in]Transition 2:4 (2016). http://mediacommons.org/intransition/fembot-red-dress

· Miguel Mesquita Duarte. ‘The Birds, after Hitchcock’. [in]Transition 5:4 (2019). http://mediacommons.org/intransition/birds-after-hitchcock

· Chloé Galibert-Laîné, ‘Watching THE PAIN OF OTHERS’. [in]Transition 6:3 (2019). http://mediacommons.org/intransition/watching-pain-others

· Ian Garwood, ‘The Place of Voiceover in Academic Audiovisual Film and Television Criticism’. NECSUS Autumn (2016). https://necsus-ejms.org/the-place-of-voiceover-in-audiovisual-film-and-television-criticism/.

· _____ ‘SLAP THAT BASS zoomed’ (2021). https://vimeo.com/430707925

· Catherine Grant, ‘The Haunting of THE HEADLESS WOMAN’ (2019). https://vimeo.com/301095918

·_____‘Touching the Film Object?’ (2011). https://vimeo.com/28201216.

· _____‘UN/CONTAINED: A Video Essay on Andrea Arnold’s (2009) Film FISHTANK’. https://filmanalytical.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncontained-video-essay-on-andrea.html.

· Christian Keathley, ‘Pass the Salt’ (2006). https://vimeo.com/23266798

· Evelyn Kreutzer, ‘ On Psycho and The Witches’. The Cine Files 15 (2020). http://www.thecine-files.com/on-psycho-and-the-witches/.

· Evelyn Kreutzer and Noga Stiazzy. 'The Archival In-Between’. Audiovisual Traces 4 (2022). https://film-history.org/issues/text/digital-digging-traces-gazes-and-archival-between

· Kevin B. Lee, ‘TRANSFORMERS: THE PREMAKE (a desktop documentary)’ (2014). https://vimeo.com/94101046

· _____'Mourning with Minari' (2021). https://vimeo.com/530395705.

· Jason Mittell, ‘ADAPTATION.’s Anomalies’(2016). https://vimeo.com/142425249

· Darline Morales, ‘Touki Dollars’. The Cine Files 11 (2016). http://www.thecine-files.com/touki-dollars-issue11/ .

· Alan O’Leary, ‘No Voiding Time: A Deformative Video Essay’. 16:9 Filmtidsskrift (2019). http://www.16-9.dk/2019/09/no-voiding-time/

· Matt Payne, ‘Who Ever Heard…?’ (2019), https://vimeo.com/342772573

· Sight and Sound. (2020-2022). Annual best video essays polls: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/polls/best-video-essays-2022 https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/polls/best-video-essays-2021 https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/best-video-essays-2020

- Norsk Bokmål

ISSN: 2704-0968

Contact: [email protected]

How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

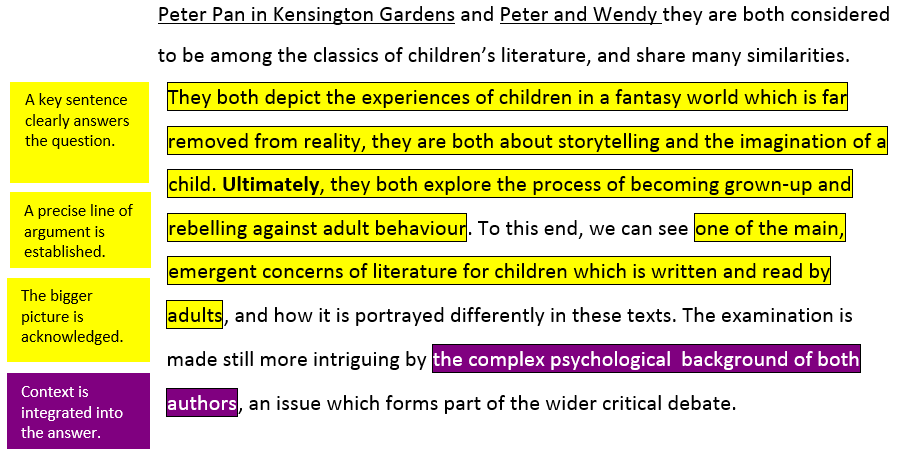

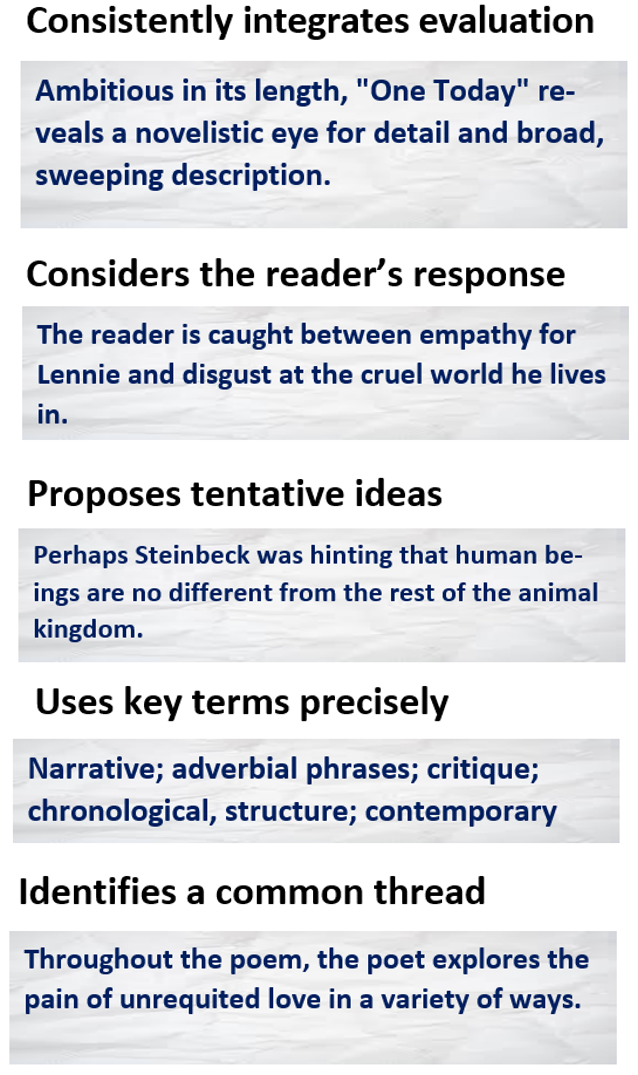

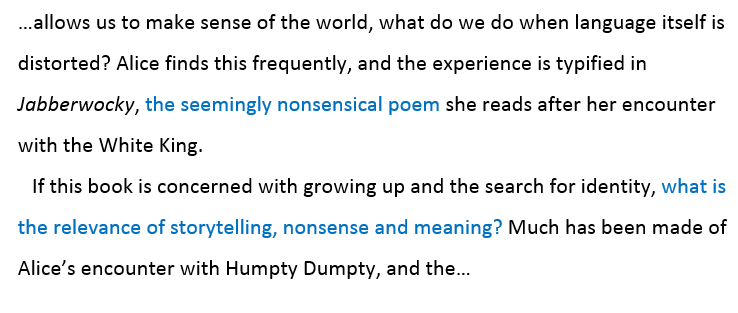

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.