Writing Student Learning Outcomes

Student learning outcomes state what students are expected to know or be able to do upon completion of a course or program. Course learning outcomes may contribute, or map to, program learning outcomes, and are required in group instruction course syllabi .

At both the course and program level, student learning outcomes should be clear, observable and measurable, and reflect what will be included in the course or program requirements (assignments, exams, projects, etc.). Typically there are 3-7 course learning outcomes and 3-7 program learning outcomes.

When submitting learning outcomes for course or program approvals, or assessment planning and reporting, please:

- Begin with a verb (exclude any introductory text and the phrase “Students will…”, as this is assumed)

- Limit the length of each learning outcome to 400 characters

- Exclude special characters (e.g., accents, umlats, ampersands, etc.)

- Exclude special formatting (e.g., bullets, dashes, numbering, etc.)

Writing Course Learning Outcomes Video

Watch Video

Steps for Writing Outcomes

The following are recommended steps for writing clear, observable and measurable student learning outcomes. In general, use student-focused language, begin with action verbs and ensure that the learning outcomes demonstrate actionable attributes.

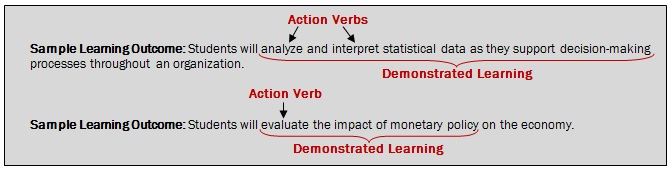

1. Begin with an Action Verb

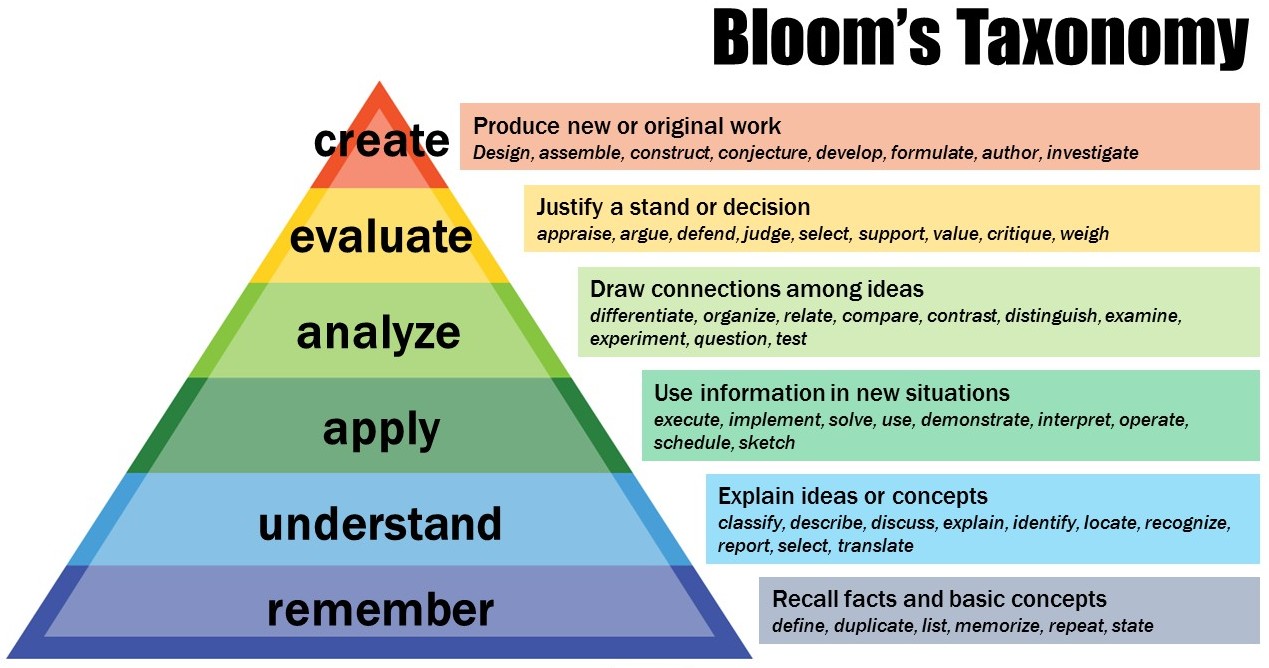

Begin with an action verb that denotes the level of learning expected. Terms such as know , understand , learn , appreciate are generally not specific enough to be measurable. Levels of learning and associated verbs may include the following:

- Remembering and understanding: recall, identify, label, illustrate, summarize.

- Applying and analyzing: use, differentiate, organize, integrate, apply, solve, analyze.

- Evaluating and creating: Monitor, test, judge, produce, revise, compose.

Consult Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy (below) for more details. For additional sample action verbs, consult this list from The Centre for Learning, Innovation & Simulation at The Michener Institute of Education at UNH.

2. Follow with a Statement

- Identify and summarize the important feature of major periods in the history of western culture

- Apply important chemical concepts and principles to draw conclusions about chemical reactions

- Demonstrate knowledge about the significance of current research in the field of psychology by writing a research paper

- Length – Should be no more than 400 characters.

*Note: Any special characters (e.g., accents, umlats, ampersands, etc.) and formatting (e.g., bullets, dashes, numbering, etc.) will need to be removed when submitting learning outcomes through HelioCampus Assessment and Credentialing (formerly AEFIS) and other digital campus systems.

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning: The “Cognitive” Domain

To the right: find a sampling of verbs that represent learning at each level. Find additional action verbs .

*Text adapted from: Bloom, B.S. (Ed.) 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1, Cognitive Domain. New York.

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition). New York: Longman.

Examples of Learning Outcomes

Academic program learning outcomes.

The following examples of academic program student learning outcomes come from a variety of academic programs across campus, and are organized in four broad areas: 1) contextualization of knowledge; 2) praxis and technique; 3) critical thinking; and, 4) research and communication.

Student learning outcomes for each UW-Madison undergraduate and graduate academic program can be found in Guide . Click on the program of your choosing to find its designated learning outcomes.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Contextualization of Knowledge

Students will…

- identify, formulate and solve problems using appropriate information and approaches.

- demonstrate their understanding of major theories, approaches, concepts, and current and classical research findings in the area of concentration.

- apply knowledge of mathematics, chemistry, physics, and materials science and engineering principles to materials and materials systems.

- demonstrate an understanding of the basic biology of microorganisms.

Praxis and Technique

- utilize the techniques, skills and modern tools necessary for practice.

- demonstrate professional and ethical responsibility.

- appropriately apply laws, codes, regulations, architectural and interiors standards that protect the health and safety of the public.

Critical Thinking

- recognize, describe, predict, and analyze systems behavior.

- evaluate evidence to determine and implement best practice.

- examine technical literature, resolve ambiguity and develop conclusions.

- synthesize knowledge and use insight and creativity to better understand and improve systems.

Research and Communication

- retrieve, analyze, and interpret the professional and lay literature providing information to both professionals and the public.

- propose original research: outlining a plan, assembling the necessary protocol, and performing the original research.

- design and conduct experiments, and analyze and interpret data.

- write clear and concise technical reports and research articles.

- communicate effectively through written reports, oral presentations and discussion.

- guide, mentor and support peers to achieve excellence in practice of the discipline.

- work in multi-disciplinary teams and provide leadership on materials-related problems that arise in multi-disciplinary work.

Course Learning Outcomes

- identify, formulate and solve integrative chemistry problems. (Chemistry)

- build probability models to quantify risks of an insurance system, and use data and technology to make appropriate statistical inferences. (Actuarial Science)

- use basic vector, raster, 3D design, video and web technologies in the creation of works of art. (Art)

- apply differential calculus to model rates of change in time of physical and biological phenomena. (Math)

- identify characteristics of certain structures of the body and explain how structure governs function. (Human Anatomy lab)

- calculate the magnitude and direction of magnetic fields created by moving electric charges. (Physics)

Additional Resources

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- The Six Facets of Understanding – Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (2nd ed.). ASCD

- Taxonomy of Significant Learning – Fink, L.D. (2003). A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning. Jossey-Bass

- College of Agricultural & Life Sciences Undergraduate Learning Outcomes

- College of Letters & Science Undergraduate Learning Outcomes

Learning Outcomes 101: A Comprehensive Guide

For those trying to figure out what are learning outcomes, its types, steps, and assessments, this article is for you. Read on to find out more about this guide in developing your teaching strategies.

Table of Contents

Introduction.

In today’s education landscape, learning outcomes play a pivotal role in shaping the educator’s teaching strategies and heralding the academic progress of students. Defining the road map of a learning session, the learning outcomes focus on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that learners should grasp upon the completion of a course or program.

The relevance and applicability of learning outcomes extend to both the educators and the learners, providing the former with a clear teaching structure and the latter with expectations for their learning.

In the broader sense, understanding these integral aspects of our education system would be incomplete without delving into the types of learning outcomes, elucidating the steps involved in formulating them, exploring their assessment, and shedding light on their impacts and challenges.

Defining Learning Outcomes

What are learning outcomes.

Learning outcomes are statements that describe the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students should have after completing a learning activity or program. These outcomes articulate what students should know or be able to do as a result of the learning experience. This includes knowledge gained , new skills acquired , a deepened understanding of the subject matter , attitudes and values influenced by learning, as well as changes in behavior that can be applied in specific contexts.

Learning outcomes are statements that describe the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students should have after completing a learning activity or program.

Learning outcomes are critical in the educational setting because they guide the design of curriculum , instruction, and assessment methods. They are the foundation of a course outline or syllabus, providing clear direction for what will be taught, how it will be taught, and how learning will be assessed. They hold teachers accountable for delivering effective instruction that leads to desired learning outcomes and help students understand what is expected of them, enhancing their learning experience.

Learning outcomes also equip students with transferrable skills and knowledge. They provide a clear description of what the learner can apply in real-world contexts or in their further studies. This makes learning outcomes not only crucial in the academic setting but also in preparing learners for the workforce.

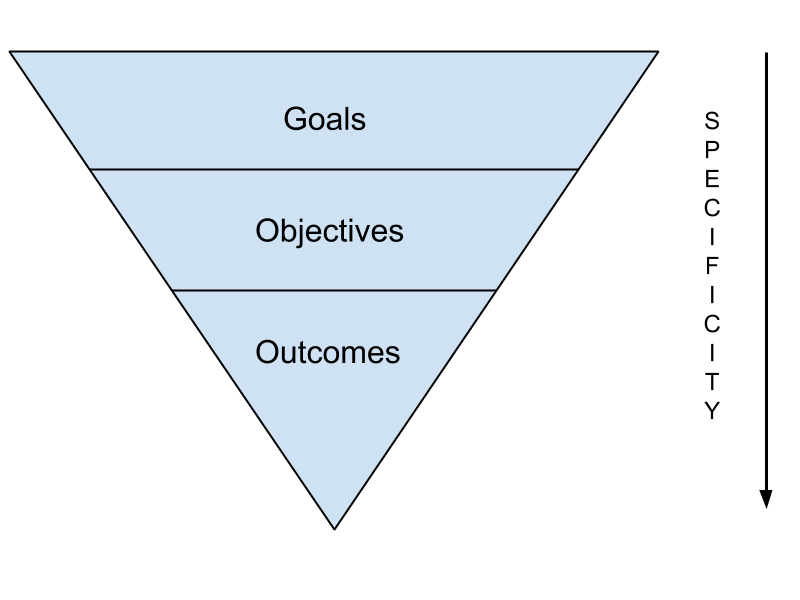

Differentiating Learning Outcomes from Learning Objectives

Learning outcomes and learning objectives are often used interchangeably. However, they have distinct meanings and roles in education.

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives are more teacher-centered and describe what the teacher intends to teach or what the instruction aims to achieve in the scope of a lesson or unit. These may involve specific steps or methodologies used to impart knowledge or skills to the students.

Learning Outcomes

On the other hand, learning outcomes are student-centered and focus on what the student is expected to learn and demonstrate at the end of a learning period. These are usually measurable and observable, making them useful tools for assessing a student’s learning progress and the effectiveness of a lesson or course.

For instance, a learning objective may state, “The teacher will explain the process of photosynthesis.” The associated learning outcome could be, “Students will be able to describe the process of photosynthesis and explain its importance to plant life.”

Examples of Learning Outcomes

Various academic disciplines utilize explicit learning outcomes to provide students with a clear understanding of what they are expected to achieve by the end of a course, unit, or lesson. Here are some examples:

- Mathematics: By the close of the course, students should be capable of solving linear equations and inequalities.

- Science: Upon finishing the module, students will be equipped to accurately elucidate the importance of DNA in genetic inheritance.

- English: Students should be proficient in crafting an organized, eloquent essay that effectively puts forth an argument.

- Social Studies: By the term’s conclusion, students should possess the ability to assess the impacts of World War II from varied perspectives.

- Arts: After completing the lesson, learners should be adept at recreating a piece of art employing learnt techniques, such as watercolor painting.

These specific learning outcomes are instrumental in steering the progress of students throughout their educational journey. They provide key alignment within the education system, ensuring that instructions, learning activities, assessments, and feedback are all constructed around accomplishing these predefined objectives.

3 Types of Learning Outcomes

1. knowledge outcomes.

Knowledge outcomes represent a student’s capacity to remember and comprehend the information and concepts imparted during lessons. These outcomes are usually assessed through examinations or tests, which gauge how well the student has retained the information.

To illustrate, a history student may be tested on their ability to remember specific dates or events, whereas a science student may be required to understand and demonstrate the process of photosynthesis.

This strand of learning outcomes is generally divided into two categories: declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge . Declarative knowledge outcomes evaluate the student’s aptitude to recollect and identify factual information , such as the capital city of a country. In contrast, procedural knowledge outcomes measure the student’s ability to utilize rules and processes fruitfully to solve problems , such as mathematical calculations. Thus, both these subsets form the bedrock of a student’s academic accomplishments.

2. Skill Outcomes

Skill outcomes assess a student’s ability to apply learned theories or concepts within real-world contexts. These are practical skills often developed through hands-on experience and active participation, such as fieldwork or lab experiments. They may also stem from the application of theoretical knowledge to solve practical problems.

For instance, a student studying biology may be required to carry out a dissection as part of their assessments. Similarly, a computer science student might be assessed based on their problem-solving skills using programming languages.

Skill outcomes are commonly split into two categories: generic skills and specific skills . Generic skills are transferable skills that can be used across various fields , such as communication or teamwork skills. Specific skills pertain to specific fields or jobs, such as the ability to use laboratory equipment correctly or the ability to compile code in a specific programming language.

3. Attitudinal Outcomes

When assessing a student’s growth and learning, attitudinal outcomes come into play. These are used to measure a student’s attitudes, values, and beliefs . Given their inherent subjectivity, these outcomes can be a challenge to measure. However, educators utilize various methods such as surveys , reflective journals , and direct observations to evaluate them accurately.

For example, in an ethics course, an attitudinal outcome may include the student’s ability to comprehend, value, and respect different cultural or ethical contexts. Similarly, in an environmental studies course, an outcome could involve evaluating the student’s attitudes towards sustainable practices.

Such outcomes play a significant role in shaping a student’s viewpoint and actions, both in the classroom and beyond. Attitudinal outcomes can reflect changes in attitudes, enhanced appreciation of alternate perspectives, or an inclination to engage with different individuals or groups.

While these outcomes may be more challenging to assess than knowledge or skill-based outcomes, they are imperative for nurturing lifelong learners dedicated to ongoing personal and professional development .

Steps in Formulating Learning Outcomes

1. determine the knowledge, essential skills, and attitude expected.

Once an understanding of knowledge, skills, and attitudinal outcomes is obtained, educators then identify the necessary knowledge, skills and attitude (KSA) that students need to acquire in a specific subject. This stage involves identifying the important competencies and understandings that should be mastered by the end of a course or learning program.

For example, in a mathematics course, core skills that a student may need to develop could include solving linear equations, while key knowledge to be absorbed might involve grasping the principles of calculus.

By identifying these skills and knowledge, the foundation is laid for designing effective learning outcomes. These insights then guide subsequent steps in the process of formulating concrete and measurable learning outcomes for specific courses or programs.

2. Draft the Learning Objectives

Once the necessary skills and knowledge have been identified, the next step entails crafting preliminary learning objectives.

At this juncture, educators start to formulate the objectives that guide the learning process. These objectives should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) to ensure they can effectively guide students’ learning.

For example, in a history course, a learning objective could be: “By the end of the semester, students will be able to identify and analyze the primary causes and effects of the First World War.” But you can break this objective into two as it is good practice to have only one learning objective as guide for your lessons.

Hence, we can rephrase the learning objective as “By the end of the semester, students will be able to 1) identify the primary causes of the First World War, and 2) analyze the effects of the First World War.”

3. Develop the Learning Outcomes

The third step in the process involves evolving these learning objectives into learning outcomes. Unlike objectives, which refer to goals that educators set for their students, learning outcomes refer to demonstrable skills or competencies that learners should exhibit upon the completion of a course or program. They are typically written from a learner’s perspective and are often accompanied by associated assessment criteria.

A related outcome to the previous example would be: “Students will demonstrate their understanding of the causes and effects of the First World War through a detailed written content analysis .”

4. Write Clear and Achievable Outcomes

Writing clear and achievable outcomes is the next significant step.

An effective learning outcome should be worded clearly enough that it becomes obvious to both learners and educators whether or not it has been achieved. Each outcome must also be achievable within the constraints of the learning program.

For example, an achievable outcome of an English course might be: “At the end of the course, students will be able to write a well-structured and clearly argued essay”.

5. Understand and Refine Learning Outcomes

Learning outcomes are a critical piece of the educational process. They lay the groundwork for curriculum design , teaching methods, and evaluation procedures in our educational system. These outcomes are the skills, knowledge, or mental attitudes that students are anticipated to gain throughout their learning experience. They may pertain to subject-specific understanding, general knowledge, or transferable skills like problem-solving or analytical thinking. Once these learning outcomes are initially established, it’s necessary to reassess and refine them to ensure they remain relevant and beneficial to the students.

Assessment of Learning Outcomes

Regularly refine and revise the learning outcomes.

Once the preliminary draft of learning outcomes is developed, educators need to evaluate them to certify they align properly with the program’s curriculum and the distribution of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills is accurate. Refining these outcomes might involve rephrasing for clarity , confirming their relevance to the course and student needs , ensuring they are attainable and manageable within the parameters of the course. Regular revisions, reflections, and refinements of these outcomes become necessary to make certain they stay potent and significant.

For instance, an English course’s prior outcome might be modified following a review to something like: “Upon completing the course, students will demonstrate their capability to write a well-structured persuasive essay with hardly any grammatical errors.”

Methods to Assess Learning Outcomes

Achievement of learning outcomes can be assessed via various methods, largely dependent on the nature of the learning outcome itself. Traditional methods of evaluation include written tests and quizzes, which are effective at measuring content knowledge and comprehension skills. Provided students have been well-prepared and the assessment is fair, results from these can accurately reflect student learning.

Other methods include project-based assessments or portfolios , which are ideal for evaluating more complex learning outcomes, such as problem-solving skills, creativity, and the ability to apply knowledge in real-world situations. These types of assessments allow students to demonstrate their skills and knowledge in a more meaningful context, and they provide evidence of learning that is more authentic and comprehensive than a single test score.

Importance of Consistent and Fair Assessments

Consistency and fairness in assessments are not only important for accuracy, but also for promoting a positive learning environment. Assessments should be built around clear and measurable outcomes , and students should understand these outcomes ahead of time. This ensures that every student knows what they are expected to learn and how their learning will be measured.

Assessment tasks and criteria should be structured in a way that all students have an equal opportunity to demonstrate their learning. Moreover, assessments should challenge students appropriately, pushing them to extend their learning while not imposing unrealistic expectations.

If the assessment is perceived to be unfair or inconsistent, students may lose motivation, resulting in decreased performance and engagement with the subject matter. They may also develop negative attitudes toward learning and education in general, which can have detrimental effects on their future learning experiences.

Different Ways to Evaluate Learning Outcomes

The most common way to evaluate learning outcomes is through formative and summative assessments .

Formative assessments occur throughout the learning process and provide ongoing feedback to students. They can take the form of quizzes, assignments, class discussions , and more informal methods like self or peer assessments .

Summative assessments take place after instruction and are often used to evaluate student’s mastery of content and skills. These assessments might include final exams , term papers , or presentations .

However, regardless of the type, all assessments must be developed with clear and direct alignment to learning outcomes.

Moreover, rubrics are often used in assessing more complex learning outcomes. This tool articulates expectations about an assignment by listing the criteria or what counts, and describing levels of quality from excellent to poor.

Feedback as a Key Component in Evaluating Learning Outcomes

In evaluating learning outcomes, feedback stands as a central tool. When offered promptly and constructively, feedback can work wonders in elevating learning experiences. It not only offers students a mirror to reflect on their performance, strengths and opportunities for augmentation but also deepens their understanding and motivates their progress—thus enriching the overall learning outcomes.

Through consistent, purposeful and tailored feedback, educators have the power to steer their students’ learning trajectory towards achieving desired outcomes. It’s a navigational tool that informs students’ journey in gaining new knowledge and honing skills that are in sync with envisioned learning outcomes.

Impacts and Challenges of Learning Outcomes

Learning outcomes: proven catalysts in students’ upward progression.

Learning outcomes hold the potential to significantly influence a student’s learning journey – they serve as beacons, inspiring, steering, and propelling learners towards pre-determined goals. A clear understanding and grasp of these outcomes can help students to strategically streamline their efforts to accomplish these objectives, thus promoting focused learning.

Notable facets of well-formulated learning outcomes include fostering active participation among learners in their learning process. Armed with identified objectives, learners transform from being mere passive consumers of information to active measurers of their own progress, calibrating their strategies accordingly.

Learning outcomes also fuel learners’ confidence and desire to learn. They provide incremental milestones towards the ultimate goal, enabling learners to revel in frequent success and thus perpetuate a positive feedback loop. This heightened morale becomes a natural motivator that drives persistent learning endeavors.

Nevertheless, learning outcomes pose potential drawbacks as well. These come to the fore if the outcomes are overly specific and rigid , thereby stifling critical thinking and creativity. On the other hand, unduly lofty outcomes could leave students grappling to meet them, causing frustration and eventual disinterest. Accordingly, there lies a crucial need for balanced, flexible, and attainable learning outcomes.

Challenges in Implementing Learning Outcomes

Despite the obvious benefits, the implementation of learning outcomes can present specific challenges. These include potential resistance from teachers or educators who may have grown comfortable with traditional methods and perceive the introduction of learning outcomes as an unnecessary burden or interference.

The formulation of learning outcomes itself is a complex process that demands a deep understanding of the domain of learning. It is crucial to balance the need for specificity of outcomes, with the breadth and richness of the learning experience. Getting this balance right can be a painstaking process.

Differing interpretations and perspectives among faculty about what constitutes good learning outcomes can also be a point of contention. This can lead to a lack of consensus and inconsistencies in implementation.

Overcoming Challenges

Overcoming these challenges requires a holistic approach. Organizational culture plays a crucial role in this regard. Encouraging a culture of change and innovation can mitigate resistance from faculty.

Professional development programs , workshops, and training can be helpful in honing faculty’s skills for creating and implementing effective learning outcomes. These programs can also be used to foster a shared understanding of the purpose and role of learning outcomes.

Another pragmatic approach could be to incrementally introduce learning outcomes while reassuring educators of continued support during the transition. This can be further backed up by regular assessments to provide constructive feedback for improvements.

Thoroughly comprehending learning outcomes and effectively implementing them in educational circumstances is a challenging yet rewarding task. Learning outcomes, including knowledge outcomes, skill outcomes, and attitudinal outcomes, provide a comprehensive framework for a constructive learning environment. They are cardinal in structuring the teaching methods, allowing educators to chart a clear course for student learning, and rightly assessing the achieved outcomes offers vital insights into their effectiveness.

However, it’s essential to consider the challenges that might be encountered in this process. Notwithstanding these challenges, the potential benefits of learning outcomes to students’ educational progress present them as a crucial factor in the quest for enhanced education quality.

Related Posts

Six Famous Curriculum Theorists and their Contributions to Education

Three Examples of Creative Curriculum Lessons

How to Use the Grammar Translation Method

About the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel, a faculty member of the graduate school, served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

SimplyEducate.Me Privacy Policy

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

IUPUI IUPUI IUPUI

- Center Directory

- Hours, Location, & Contact Info

- Plater-Moore Conference on Teaching and Learning

- Teaching Foundations Webinar Series

- Associate Faculty Development

- Early Career Teaching Academy

- Faculty Fellows Program

- Graduate Student and Postdoc Teaching Development

- Awardees' Expectations

- Request for Proposals

- Proposal Writing Guidelines

- Support Letter

- Proposal Review Process and Criteria

- Support for Developing a Proposal

- Download the Budget Worksheet

- CEG Travel Grant

- Albright and Stewart

- Bayliss and Fuchs

- Glassburn and Starnino

- Rush Hovde and Stella

- Mithun and Sankaranarayanan

- Hollender, Berlin, and Weaver

- Rose and Sorge

- Dawkins, Morrow, Cooper, Wilcox, and Rebman

- Wilkerson and Funk

- Vaughan and Pierce

- CEG Scholars

- Broxton Bird

- Jessica Byram

- Angela and Neetha

- Travis and Mathew

- Kelly, Ron, and Jill

- Allison, David, Angela, Priya, and Kelton

- Pamela And Laura

- Tanner, Sally, and Jian Ye

- Mythily and Twyla

- Learning Environments Grant

- Extended Reality Initiative(XRI)

- Champion for Teaching Excellence Award

- Feedback on Teaching

- Consultations

- Equipment Loans

- Quality Matters@IU

- To Your Door Workshops

- Support for DEI in Teaching

- IU Teaching Resources

- Just-In-Time Course Design

- Teaching Online

- Scholarly Teaching Taxonomy

- The Forum Network

- Media Production Spaces

- CTL Happenings Archive

- Recommended Readings Archive

Center for Teaching and Learning

- Preparing to Teach

Writing and Assessing Student Learning Outcomes

By the end of a program of study, what do you want students to be able to do? How can your students demonstrate the knowledge the program intended them to learn? Student learning outcomes are statements developed by faculty that answer these questions. Typically, Student learning outcomes (SLOs) describe the knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviors or values students should be able to demonstrate at the end of a program of study. A combination of methods may be used to assess student attainment of learning outcomes.

Characteristics of Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs)

- Describe what students should be able to demonstrate, represent or produce upon completion of a program of study (Maki, 2010)

Student learning outcomes also:

- Should align with the institution’s curriculum and co-curriculum outcomes (Maki, 2010)

- Should be collaboratively authored and collectively accepted (Maki, 2010)

- Should incorporate or adapt professional organizations outcome statements when they exist (Maki, 2010)

- Can be quantitatively and/or qualitatively assessed during a student’s studies (Maki, 2010)

Examples of Student Learning Outcomes

The following examples of student learning outcomes are too general and would be very hard to measure : (T. Banta personal communication, October 20, 2010)

- will appreciate the benefits of exercise science.

- will understand the scientific method.

- will become familiar with correct grammar and literary devices.

- will develop problem-solving and conflict resolution skills.

The following examples, while better are still general and again would be hard to measure. (T. Banta personal communication, October 20, 2010)

- will appreciate exercise as a stress reduction tool.

- will apply the scientific method in problem solving.

- will demonstrate the use of correct grammar and various literary devices.

- will demonstrate critical thinking skills, such as problem solving as it relates to social issues.

The following examples are specific examples and would be fairly easy to measure when using the correct assessment measure: (T. Banta personal communication, October 20, 2010)

- will explain how the science of exercise affects stress.

- will design a grounded research study using the scientific method.

- will demonstrate the use of correct grammar and various literary devices in creating an essay.

- will analyze and respond to arguments about racial discrimination.

Importance of Action Verbs and Examples from Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Action verbs result in overt behavior that can be observed and measured (see list below).

- Verbs that are unclear, and verbs that relate to unobservable or unmeasurable behaviors, should be avoided (e.g., appreciate, understand, know, learn, become aware of, become familiar with). View Bloom’s Taxonomy Action Verbs

Assessing SLOs

Instructors may measure student learning outcomes directly, assessing student-produced artifacts and performances; instructors may also measure student learning indirectly, relying on students own perceptions of learning.

Direct Measures of Assessment

Direct measures of student learning require students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. They provide tangible, visible and self-explanatory evidence of what students have and have not learned as a result of a course, program, or activity (Suskie, 2004; Palomba & Banta, 1999). Examples of direct measures include:

- Objective tests

- Presentations

- Classroom assignments

This example of a Student Learning Outcome (SLO) from psychology could be assessed by an essay, case study, or presentation: Students will analyze current research findings in the areas of physiological psychology, perception, learning, abnormal and social psychology.

Indirect Measures of Assessment

Indirect measures of student learning capture students’ perceptions of their knowledge and skills; they supplement direct measures of learning by providing information about how and why learning is occurring. Examples of indirect measures include:

- Self assessment

- Peer feedback

- End of course evaluations

- Questionnaires

- Focus groups

- Exit interviews

Using the SLO example from above, an instructor could add questions to an end-of-course evaluation asking students to self-assess their ability to analyze current research findings in the areas of physiological psychology, perception, learning, abnormal and social psychology. Doing so would provide an indirect measure of the same SLO.

- Balances the limitations inherent when using only one method (Maki, 2004).

- Provides students the opportunity to demonstrate learning in an alternative way (Maki, 2004).

- Contributes to an overall interpretation of student learning at both institutional and programmatic levels.

- Values the many ways student learn (Maki, 2004).

Bloom, B. (1956) A taxonomy of educational objectives, The classification of educational goals-handbook I: Cognitive domain . New York: McKay .

Maki, P.L. (2004). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution . Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Maki, P.L. (2010 ). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution (2nd ed.) . Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Palomba, C.A., & Banta, T.W. (1999). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Suskie, L. (2004). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing.

Revised by Doug Jerolimov (April, 2016)

Helpful Links

- Revise Bloom's Taxonomy Action Verbs

- Fink's Taxonomy

Related Guides

- Creating a Syllabus

- Assessing Student Learning Outcomes

Recommended Books

Center for Teaching and Learning social media channels

CENTRE FOR TEACHING SUPPORT & INNOVATION

- What We Offer Home

- Consultations

- CTSI Programming

- Teaching with Generative AI at U of T

Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Course Evaluations

- Teaching Awards

- Teaching Feedback Services

- Resources Home

- Assessing Learning

- Engaging Your Students

- Improving Practice

- Planning and Delivering Your Courses

- Tool Guides

- Tool Finder

- Teaching with Technology

- Search for:

- Advanced Site Search

Developing Learning Outcomes

What are learning outcomes.

Learning outcomes are statements that describe the knowledge or skills students should acquire by the end of a particular assignment, class, course, or program. They help students:

- understand why that knowledge and those skills will be useful to them

- focus on the context and potential applications of knowledge and skills

- connect learning in various contexts

- help guide assessment and evaluation

Good learning outcomes emphasize the application and integration of knowledge. Instead of focusing on coverage of material, learning outcomes articulate how students will be able to employ the material, both in the context of the class and more broadly.

Consider using approximately five to ten learning outcomes per assignment; this number allows the learning outcomes to cover a variety of knowledge and skills while retaining a focus on essential elements of the course.

Learn how you can add learning outcomes to your Quercus course .

Examples of Learning Outcomes

For reference, Bloom’s Taxonomy of relevant active verbs.

- identify and describe the political, religious, economic, and social uses of art in Italy during the Renaissance

- identify a range of works of art and artists analyze the role of art and of the artist in Italy at this time

- analyze the art of the period according to objective methods

- link different materials and types of art to the attitudes and values of the period

- evaluate and defend their response to a range of art historical issues

- provide accurate diagrams of cells and be able to classify cells from microscopic images

- identify and develop data collection instruments and measures for planning and conducting sociological research

- identify and classify their spending habits and prepare a personal budget

- predict the appearance and motion of visible celestial objects

- formulate scientific questions about the motion of visible celestial objects

- plan ways to model and/or simulate an answer to the questions chosen

- select and integrate information from various sources, including electronic and print resources, community resources, and personally collected data, to answer the questions chosen communicate scientific ideas, procedures, results, and conclusions using appropriate SI units, language, and formats

- describe, evaluate, and communicate the impact of research and other accomplishments in space technology on our understanding of scientific theories and principles and on other fields of endeavour

- By the end of this course, students will be able to categorize macroeconomic policies according to the economic theories from which they emerge.

- By the end of this unit, students will be able to describe the characteristics of the three main types of geologic faults (dip-slip, transform, and oblique) and explain the different types of motion associated with each.

- By the end of this course, students will be able to ask questions concerning language usage with confidence and seek effective help from reference sources.

- By the end of this course, students will be able to analyze qualitative and quantitative data, and explain how evidence gathered supports or refutes an initial hypothesis.

- By the end of this course, students will be able to work cooperatively in a small group environment.

- By the end of this course, students will be able to identify their own position on the political spectrum.

Specific Language

Learning outcomes should use specific language , and should clearly indicate expectations for student performance.

Vague Outcome : By the end of this course, students will have added to their understanding of the complete research process.

More Precise Outcome : By the end of this course, students will be able to:

- describe the research process in social interventions

- evaluate critically the quality of research by others

- formulate research questions designed to test, refine, and build theories

- identify and demonstrate facility in research designs and data collection strategies that are most appropriate to a particular research project

- formulate a complete and logical plan for data analysis that will adequately answer the research questions and probe alternative explanations

- interpret research findings and draw appropriate conclusions

Vague Outcome : By the end of this course, students will have a deeper appreciation of literature and literary movements in general.

- identify and describe the major literary movements of the 20th century

- perform close readings of literary texts

- evaluate a literary work based on selected and articulated standards

For All Levels

Learning outcomes are useful for all levels of instruction, and in a variety of contexts.

By the end of this course students will be able to:

- identify the most frequently encountered endings for nouns, adjectives and verbs, as well as some of the more complicated points of grammar, such as aspect of the verb

- translate short unseen texts from Czech

- read basic material relating to current affairs using appropriate reference works, where necessary

- make themselves understood in basic everyday communicative situations

By the end of this course, students will be able to:

- identify key measurement problems involved in the design and evaluation of social interventions and suggest appropriate solutions

- assess the strengths and weaknesses of alternative strategies for collecting, analyzing and interpreting data from needs analyses and evaluations in direct practice, program and policy interventions

- identify specific strategies for collaborating with practitioners in developmental projects, formulation of research questions, and selection of designs and measurement tools so as to produce findings usable by practitioners at all levels

- analyze qualitative data systematically by selecting appropriate interpretive or quantified content analysis strategies

- evaluate critically current research in social work

- articulate implications of research findings for explanatory and practice theory development and for practice/program implementation

- instruct classmates and others in an advanced statistical or qualitative data analysis procedure

By the end of the course you will be able to:

- identify several learning style models and know how to use these models in your teaching

- construct and use learning objectives

- design a course and a syllabus

- implement the principles of Universal Instructional Design in the design of a course

- use strategies and instructional methods for effective teaching of small classes and large classes

- identify the advantages and disadvantages of different assessment methods

- construct a teaching portfolio

Why Develop Learning Outcomes?

For students:.

- By focusing on the application of knowledge and skills learned in a course and on the integration of knowledge and skills with other areas of their lives, students are more connected to their learning and to the material of the course.

- The emphasis on integration and generalizable skills helps students draw connections between courses and other kinds of knowledge, enhancing student engagement.

- Students understand the conditions and goals of their assessment.

For instructors:

- Developing learning outcomes allows for reflection on the course content and its potential applications, focusing on the knowledge and skills that will be most valuable to the student now and in the future.

- Learning outcomes point to useful methods of assessment.

- Learning outcomes allow instructors to set the standards by which the success of the course will be evaluated.

For institutions and administrators:

- When an instructor considers the particular course or unit in the context of future coursework and the curriculum as a whole, it contributes to the development of a coherent curriculum within a decentralized institution and helps to ensure that students are prepared for future work and learning.

- The application and integration of learning emphasized by learning outcomes reflect and support the contemporary nature and priorities of the university, enhancing student engagement, uncovering opportunities for interdisciplinary, and providing guidance and support for students with many different kinds of previous academic preparation.

- Learning outcomes provide structures from which courses and programs can be evaluated and can assist in program and curricular design, identify gaps or overlap in program offerings, and clarify instructional, programmatic, and institutional priorities.

Context of Learning

In developing learning outcomes, first consider the context of the learning taking place in the course might include:

- If the course is part of the major or specialization, what knowledge or skills should students have coming into the course? What knowledge or skills must they have by its conclusion in order to proceed through their program?

- How can this course contribute to the student’s broad learning and the student’s understanding of other subjects or disciplines?

- What are the priorities of the department or Faculty? How does the particular focus of the course contribute to those broader goals?

- Does the course play a particular role within the student’s program (introductory, elective, summative)? How is the course shaped by this role?

- What knowledge or skills gained in this course will serve students throughout their lives? How will the class shape the student’s general understanding of the world?

- Which careers commonly stem from education in this field? What are the skills or knowledge essential to these careers?

- What kinds of work are produced in those careers?

- How can this course enrich a student’s personal or professional life?

- Where will the student encounter the subject matter of the course elsewhere in his or her life? In what situations might the knowledge or skills gained in the course be useful to the student?

Tools for Developing Learning Outcomes

The process of developing learning outcomes offers an opportunity for reflection on what is most necessary to help learners gain this knowledge and these skills. Considering the following elements as you prepare your learning outcomes.

To begin the process of developing learning outcomes, it may be useful to brainstorm some key words central to the disciplinary content and skills taught in the course. You may wish to consider the following questions as you develop this list of key words:

- What are the essential things students must know to be able to succeed in the course?

- What are the essential things students must be able to do to succeed in the course?

- What knowledge or skills do students bring to the course that the course will build on?

- What knowledge or skills will be new to students in the course?

- What other areas of knowledge are connected to the work of the course?

Scholars working in pedagogy and epistemology offer us taxonomies of learning that can help make learning outcomes more precise. These levels of learning can also help develop assessment and evaluation methods appropriate to the learning outcomes for the course.

Bloom’s Taxonomy and Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO) Taxonomy

These three areas can be used to identify and describe different aspects of learning that might take place in a course.

Content can be used to describe the disciplinary information covered in the course. This content might be vital to future work or learning in the area. A learning outcome focused on content might read:

By the end of this course, students will be able recall the 5 major events leading up to the Riel Rebellion and describe their role in initiating the Rebellion.

Skills can refer to the disciplinary or generalizable skills that students should be able to employ by the conclusion of the class. A learning outcome focused on skills might read:

By the end of this course, students will be able to define the characteristics and limitations of historical research.

Values can describe some desired learning outcomes, the attitudes or beliefs imparted or investigated in a particular field or discipline. In particular, value-oriented learning outcomes might focus on ways that knowledge or skills gained in the course will enrich students’ experiences throughout their lives. A learning outcome focused on values might read:

By the end of this course, students will be able to articulate their personal responses to a literary work they have selected independently.

Characteristics of Good Learning Outcomes

Good learning outcomes are very specific , and use active language – and verbs in particular – that make expectations clear and ensure that student and instructor goals in the course are aligned.

Where possible, avoid terms, like understand or demonstrate, that can be interpreted in many ways.

See the Bloom’s Taxonomy resource for a list of useful verbs.

Vague Outcome : By the end of the course, I expect students to increase their organization, writing, and presentation skills.

More precise outcome : By the end of the course, students will be able to:

- produce professional quality writing

- effectively communicate the results of their research findings and analyses to fellow classmates in an oral presentation

Vague Outcome : By the end of this course, students will be able to use secondary critical material effectively and to think independently.

More precise outcome : By the end of this course, students will be able to evaluate the theoretical and methodological foundations of secondary critical material and employ this evaluation to defend their position on the topic.

Keep in mind, learning outcomes:

- should be flexible : while individual outcomes should be specific, instructors should feel comfortable adding, removing, or adjusting learning outcomes over the length of a course if initial outcomes prove to be inadequate

- are focused on the learner: rather than explaining what the instructor will do in the course, good learning outcomes describe knowledge or skills that the student will employ, and help the learner understand why that knowledge and those skills are useful and valuable to their personal, professional, and academic future

- are realistic , not aspirational: all passing students should be able to demonstrate the knowledge or skill described by the learning outcome at the conclusion of the course. In this way, learning outcomes establish standards for the course

- focus on the application and integration of acquired knowledge and skills: good learning outcomes reflect and indicate the ways in which the described knowledge and skills may be used by the learner now and in the future

- indicate useful modes of assessment and the specific elements that will be assessed: good learning outcomes prepare students for assessment and help them feel engaged in and empowered by the assessment and evaluation process

- offer a timeline for completion of the desired learning

Each assignment, activity, or course might usefully employ between approximately five and ten learning outcomes; this number allows the learning outcomes to cover a variety of knowledge and skills while retaining a focus on essential elements of the course.

- Speak to the learner : learning outcomes should address what the learner will know or be able to do at the completion of the course

- Measurable : learning outcomes must indicate how learning will be assessed

- Applicable : learning outcomes should emphasize ways in which the learner is likely to use the knowledge or skills gained

- Realistic : all learners who complete the activity or course satisfactorily should be able to demonstrate the knowledge or skills addressed in the outcome

- Time-bound : the learning outcome should set a deadline by which the knowledge or skills should be acquired;

- Transparent : should be easily understood by the learner; and

- Transferable : should address knowledge and skills that will be used by the learner in a wide variety of contexts

The SMART(TT) method of goal setting is adapted from Blanchard, K., & Johnson, S. (1981). The one minute manager. New York: Harper Collins

Assessment: Following Through on Learning Outcomes

Through assessment, learning outcomes can become fully integrated in course design and delivery. Assignments and exams should match the knowledge and skills described in the course’s learning outcomes. A good learning outcome can readily be translated into an assignment or exam question; if it cannot, the learning outcome may need to be refined.

One way to match outcomes with appropriate modes of assessment is to return to Bloom’s Taxonomy . The verbs associated with each level of learning indicate the complexity of the knowledge or skills that students should be asked to demonstrate in an assignment or exam question.

For example, an outcome that asks students to recall key moments leading up to an historical event might be assessed through multiple choice or short answer questions. By contrast, an outcome that asks students to evaluate several different policy models might be assessed through a debate or written essay.

Learning outcomes may also point to more unconventional modes of assessment. Because learning outcomes can connect student learning with its application both within and outside of an academic context, learning outcomes may point to modes of assessment that parallel the type of work that students may produce with the learned knowledge and skills in their career or later in life.

Unit of Instruction (e.g. lecture, activity, exam, course, workshop) and Assessment Examples

Objective : What content or skills will be covered in this instruction?

- Identification and evaluation of severe weather patterns, use of weather maps

Outcome : What should students know or be able to do as a result of this unit of instruction?

- By completing this assignment, students will be able to accurately predict severe weather using a standard weather map.

How do you know? : How will you be able to tell that students have achieved this outcome?

- Student predictions will be compared with historical weather records.

Assessment : What kind of work can students produce to demonstrate this?

- Based on this standard weather map, please indicate where you would expect to see severe weather in the next 24-hour period. Your results will be compared with historical weather records.

- Stylistic characteristics and common themes of Modernist literature

- By the end of this unit, students will be able to identify the stylistic and thematic elements of Modernism.

- Students will be able to identify a passage from a Modernist novel they have not read.

- Read this passage. Identify which literary movement it represents and which qualities drew you to that conclusion.

Course, Program, Institution: Connecting Learning Outcomes

Learning outcomes can also be implemented at the program or institutional level to assess student learning over multiple courses, and to monitor whether students have acquired the necessary knowledge and skills at one stage to be able to move onto the next.

Courses that require prerequisites may benefit from identifying a list of outcomes necessary for advancement from one level to another. When this knowledge and these skills are identified as outcomes as opposed to topics, assessment in the first level can directly measure preparation for the next level.

Many major and specialist programs identify a list of discipline-specific and multi-purpose skills, values, and areas of knowledge graduating students in the program will have. By articulating these as things that students will know or be able to do, the benefits of a program of study can be clearly communicated to prospective students, to employers, and to others in the institution.

Athabasca University developed learning outcomes for all its undergraduate major programs. Please see their Anthropology BA learning outcomes as an example.

Academic plans increasingly include a list of learning outcomes that apply across programs of study and even across degree levels. These outcomes provide an academic vision for the institution, serve as guidelines for new programs and programs undergoing review, and communicate to members of the university and the public at large the academic values and goals of the university. As previously discussed, the best learning outcomes address course-specific learning within the context of a student’s broader educational experience. One way to contribute to a coherent learning experience is to align course outcomes, when appropriate, with institutional priorities.

The University of Toronto’s academic plan, Stepping Up: A framework for academic planning at the University of Toronto, 2004-2010, outlines institutional goals in relation to the learning experience of our undergraduate and graduate students. These priorities are further articulated in “Companion Paper 1: Enabling Teaching and Learning and the Student Experience”. The skills outcomes meant to apply to all undergraduate programs follow.

- knowing what one doesn’t know and how to seek information

- able to think: that is, to reason inductively and deductively, to analyze and to synthesize, to think through moral and ethical issues, to construct a logical argument with appropriate evidence

- able to communicate clearly, substantively, and persuasively both orally and in writing

- able not only to answer questions through research and analysis but to exercise judgment about which questions are worth asking knowledgeable about and committed to standards of intellectual honesty and use of information

- knowing how to authenticate information, whether it comes from print sources or through new technologies

- able to collaborate with others from different disciplines in the recognition that multidisciplinary approaches are necessary to address the major issues facing society

- understanding the methods of scientific inquiry; that is, scientifically literate

Curriculum Mapping: Translating between local and global learning outcomes

At the global program or institutional level, learning outcomes are often necessarily vague to allow for flexibility in their implementation and assessment. Consequently, in order to be effectively applied at the local level of a course or class, they must be reformulated for the particular setting. Similarly, learning outcomes from individual courses may be extrapolated and generalized in order to create program or institution-wide learning outcomes.

Both of these processes are most frequently accomplished through a technique called “curriculum mapping” . When moving from programmatic or institutional to course or class outcomes, curriculum mapping involves identifying which courses, portions of courses, or series of courses fulfill each programmatic or institutional learning outcome.

The global learning outcomes can then be matched with course-specific outcomes that directly address the content and skills required for that particular subject material. Identifying and locating all the learning outcomes encountered by a student over the course of their program can help present learning as a coherent whole to students and others, and can help students make the connection between their learning in one course and that in another. Maki (2004) notes that understanding where particular pieces of learning take place can help students take charge of their own education:

A map reveals the multiple opportunities that students have to make progress on collectively agreed-on learning goals, beginning with their first day on campus. Accompanied by a list of learning outcomes, maps can encourage students to take responsibility for their education as a process of integration and application, not as a checklist of courses and educational opportunities. Maps can also position students to make choices about courses and educational experiences that will contribute to their learning and improve areas of weakness.

For more information about and examples of curriculum mapping, please see Maki, P. (2004). Maps and inventories: Anchoring efforts to track student learning. About Campus 9(4), 2-9.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License

Teaching Assistants' Training Program

For information on graduate student and Teaching Assistant professional development and job training, please visit the TATP for resources, events and more.

Enroll in the SoTL Hub to access resources, share ideas and engage with your U of T community.

Table of Contents

Related topics (tags), related tool guides.

- Quercus Learning Outcomes

Learning Outcomes

Ivan Andreev

Demand Generation & Capture Strategist, Valamis

July 26, 2022 · updated May 3, 2024

10 minute read

After reading this guide, you will understand the best way to set clear, actionable learning outcomes, and how to write them to improve instruction and training within your organization.

What are learning outcomes?

5 types of learning outcomes.

- Learning outcomes vs learning objectives

Examples of learning objectives and learning outcomes

Learning outcomes examples, how to write learning outcomes, learning outcomes verbs.

Learning outcomes are descriptions of the specific knowledge, skills, or expertise that the learner will get from a learning activity, such as a training session, seminar, course, or program.

Learning outcomes are measurable achievements that the learner will be able to understand after the learning is complete , which helps learners understand the importance of the information and what they will gain from their engagement with the learning activity.

Creating clear, actionable learning outcomes is an important part of the creation of training programs in organizations. When developing these programs, both management and instructors need to be clear about what learners should understand after completing their learning path.

Learning outcomes also play a key role in assessment and evaluation, making clear what knowledge learners should have upon completion of the learning activity.

A well-written learning outcome will focus on how the learner will be able to apply their new knowledge in a real-world context, rather than on a learner being able to recite information.

The most useful learning outcomes include a verb that describes an observable action, a description of what the learner will be able to do and under which conditions they will be able to do it, and the performance level they should be able to reach.

Training evaluation form template

Understand training impact and gather valuable feedback directly from learners

1. Intellectual skills

With this type of learning outcome, the learner will understand concepts, rules or procedures. Put simply, this is understanding how to do something.

2. Cognitive strategy

In this type of learning outcome, the learner uses personal strategies to think, organize, learn and behave.

3. Verbal information

This type of learning outcome is when the learner is able to definitively state what they have learned from an organized body of knowledge.

4. Motor skills

This category is concerned with the physical ability to perform actions, achieving fluidity, smoothness or proper timing through practice.

5. Attitude

This is the internal state that reflects in the learner’s behavior. It is complex to quantify but can be shown in the learner’s response to people or situations.

Learning outcomes vs learning objectives: what is the difference?

You will often see learning outcomes and learning objectives used interchangeably, but they are different. The following concepts and examples will show how learning objectives and learning outcomes for the same activity are different, although connected to each other.

Perspective of the teacher vs. student

- Learning objective : Why the teacher is creating a learning activity.

Example : This training session will discuss the new policy for reporting travel expenses.

- Learning outcome : What the learner will gain from the learning activity.

Example : The learner understands how to properly report travel expenses.

Purpose vs. outcome

- Learning objective : States the purpose of the learning activity and the desired outcomes.

Example : This class will explain new departmental HR policies.

- Learning outcome : States what the learner will be able to do upon completing the learning activity.

Example : The learner is able to give examples of when to apply new HR policies.

Future vs. past

- Learning objective : What the teacher hopes that the learning activity will accomplish. It looks to the future, what will happen.

Example : This seminar will outline new health and safety protocols.

- Learning outcome : This looks at what has been accomplished, what has happened for the learner as a result of their participation in the activity.

Example : Seminar participants can correctly identify new protocols and explain why they have been established.

Intended outcome vs. observed outcome

- Learning objectives : What the creators of the learning activity hope to achieve.

Example : This training activity will illustrate the five styles of effective communication in the workplace.

- Learning objectives : What can be demonstrably shown to have been achieved by the activity.

Example : Learners can list and define the styles of communication.

Specific units of knowledge vs. broad outcome

- Learning objective : Describes discrete concepts, skills, or units of knowledge.

Example : This lecture will list ten ways to de-escalate a confrontation in the workplace.

- Learning outcome : Describes a wider range of behavior, knowledge and skill that makes up the basis of learning.

Example : Learners can reliably demonstrate how to use de-escalation techniques to neutralize conflicts.

- Activity : An onboarding class for new hires

Learning objective : After taking this class, new hires will understand company policies and know in which situations to apply them.

Learning outcome : Learners are able to identify situations in which company policies apply and describe the proper actions to take in response to them.

This type of learning outcome deals with knowledge or intellectual skills. The learner understands the new concept that they are being taught.

- Activity : A seminar designed to help HR officers improve mediation

Learning objective : This seminar will teach learners how to effectively mediate disputes using basic conflict dynamics and negotiation.

Learning outcome : Learners understand and be able to apply basic conflict resolution practices in the workplace.

This type of learning outcome measures performance, learners are able to use what they learned in a real-world situation.

- Activity : An online training session for new product management software

Learning objective : Session will cover the three main areas of the software.

Learning outcome : Learners are able to operate software and explain the functions that they are using.

This type of learning outcome deals with competence or skill. The learner can demonstrate their understanding of the new concept.

- Activity : A virtual reality training session on how to replace machine components

Learning objective : Session will demonstrate the steps to remove and replace components.

Learning outcome : Learners can correctly remove and replace components of each machine, explaining what they are doing and why.

This learning outcome deals with motor skills. Learners can physically demonstrate the outcome of their learning.

- Activity : A lecture on organization strategies

Learning objective : Lecture will illustrate how proper organization can help managers optimize workflow within their teams.

Learning outcome : Learners can demonstrate how they will use organization strategies with actionable steps.

This outcome deals with verbal information. Learners can verbalize the knowledge they have gained and synthesize solutions for their workflow.

You can see that, although learning objectives and learning outcomes are related, they are different, and address different aspects of the learning process.

Use learning data to accelerate change

Understand learning data and receive a practical tool to help apply this knowledge in your company.

As mentioned above, well-written learning outcomes focus on what the learner can concretely demonstrate after they complete the learning activity. A learning outcome is only useful if it is measurable. So, it should include the learning behaviors of the learner, the appropriate assessment method, and the specific criteria that demonstrates success.

The following examples are well-written learning outcomes:

- learners will be able to identify which scenarios to apply each of the five types of conflict management.

- learners will be able to use the company’s LMS to effectively engage with and complete all training materials.

- learners will understand how to interpret marketing data and use it to create graphs.

- learners will understand how to employ company-prescribed SEO practices while writing copy.

- learners can properly use company guidelines to create case studies.

- learners will be able to properly operate and clean the autoclaves.

The following examples are poorly written learning outcomes:

- learners will understand conflict management.

- learners will know how to use the company’s LMS.

- learners will appreciate how to use marketing data.

- learners will know about the company’s SEO practices.

- learners will understand what goes into a case study.

- learners will learn about autoclaves.

Defining learning outcomes is also a key stage of instructional design models such as the ADDIE model and SAM . The first step of the more in-depth ADDIE model is “analyze.” During this stage is to set the goals for the new training program. This goal should be broken down into a list of clearly explained learning outcomes. While SAM takes a more rapid approach to instructional design, the primary purpose of the first preparation stage is to identify the desired learning outcomes of the program.

When writing learning outcomes, there are a few rules that you should follow.

1. Learning outcomes always use an action verb .

What action verbs can be used when writing learning outcomes?

Depending on the type of outcome, different verbs are appropriate.

Intellectual skills

- Demonstrate

Cognitive strategy

- Differentiate

- Distinguish

Verbal information

- Give examples

Motor skills

2. Learning outcomes must be written clearly, and should be easy to understand.

3. Learning outcomes should clearly indicate what learners should learn from within the discipline they are studying.

4. Learning outcomes must show what the expected level of learning or understanding should be, and it should be reasonable to the level of the learners.

5. Learning outcomes help with assessment, and thus should clearly indicate what success looks like for the learner.

6. There should not be too few or too many learning outcomes. Four to six is the ideal number.

Here are some additional tips (with example) for writing learning outcomes.

Example: a course on accounting software.

You must first start with the main learning goal of the learning activity.

The learning goal would be that the learners will become adept at the software. But that is too vague to be a learning outcome. It doesn’t tell learners what they are expected to learn, nor is it useful for assessments. Instead, that goal should be broken down into smaller parts.

The learning outcomes for this accounting course might be:

- Learners are able to generate invoices.

- Learners understand how to process income tax payments.

- Learners can demonstrate how to properly set up payroll.

- Learners can explain how to use reports to track company expenses.

All of these outcomes are clear, action-oriented and can be assessed by the instructor.

Using a simple formula of action verb plus content to be learned plus the context in which it will be used, you can create a well-written learning outcome. These learning outcomes will improve the results of learners, as they will be clear about what they are expected to learn and will be able to focus on the most pertinent information throughout the course.

You might be interested in

Behind the Valamis product vision

The Social Balance Sheet: Enabling the workforce to learn

Learning and development fundamentals

Learn what learning and development is and why it is so important. Discover main areas, terms, challenges, jobs, and the key difference between HR and L&D.

Information Literacy Toolkit: Resource for Teaching Faculty

- Learning Outcomes

Writing Learning Outcomes

- Introducing the UMD Libraries

- Finding a Research Question

- Finding Articles

- Finding Books

- Evaluating Information

- Artificial Intelligence

- Promotional Materials

- Objectives vs Outcomes

- Checklist for Outcomes

Structure of a Learning Outcome Statement:

- An action word that identifies the performance to be demonstrated

- A l earning statement that specifies what learning will be demonstrated in the performance

- A broad statement of the criterion or standard for acceptable performance

Characteristics of Good Learning Outcomes:

- Specify the level, criterion, or standard for the knowledge, skill, ability, or disposition that the learner must demonstrate

- Include conditions under which they should be able to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, abilities, or dispositions

- Contain active verbs using Bloom's taxonomy

- Be measurable / assessable

- Example of a poorly written outcome: At the end of the session, students will create a search strategy using Boolean operators and write a correctly formatted MLA citation for a scholarly article.

"Learning objectives" and "learning outcomes" are often used interchangeably in the literature. In general, "objectives" are intended results or consequences of instruction, curricula, programs, or activities, while "outcomes" are achieved results or consequences of what was learned, i.e. evidence that learning took place. Objectives are often focused on teaching intentions and typically indicate the subject content that the teacher intends to cover. Learning outcomes, on the other hand, are more student-centered and describe the actions the learner should be able to take as a result of a learning experience.

Learning Objective: This workshop will cover background and method for writing learning objectives.

Learning Outcome: At the end of this session, participants will be able to construct a learning outcome for an undergraduate course

- Are the outcomes written using action verbs to specify definite, observable behavior? OR Do they use vague or unclear language, such as "understand" or "comprehend"?

- Is it possible to collect accurate and measurable data for each outcome?

- Is it possible to use a single method to measure each outcome?

Achievable/Actionable

- Do the outcomes clearly describe and define the expected abilities, knowledge, and values of learners?

- Are the outcomes aligned with the mission, vision, values, and goals of the institution? program? course?

- Can the outcome be used to identify areas for improvement?

- Are learners at the center of the outcome, or does it focus on the teacher's behaviors?

- Is the language used to describe an outcome, not a process?

Timely/Timebound

- Can the outcome be assessed within the duration of the learning experience (course session, assignment, course, degree program, etc.)?

- How to Write Objectives and Outcomes Basics of writing learning outcomes. Includes information on how to clarify an "unclear outcome."

- Learning Outcomes: University of Connecticut Excerpt from "Assessment Primer: Goals, Objectives, and Outcomes." Quick overview of the basics of learning outcomes with a focus on course-level outcomes.