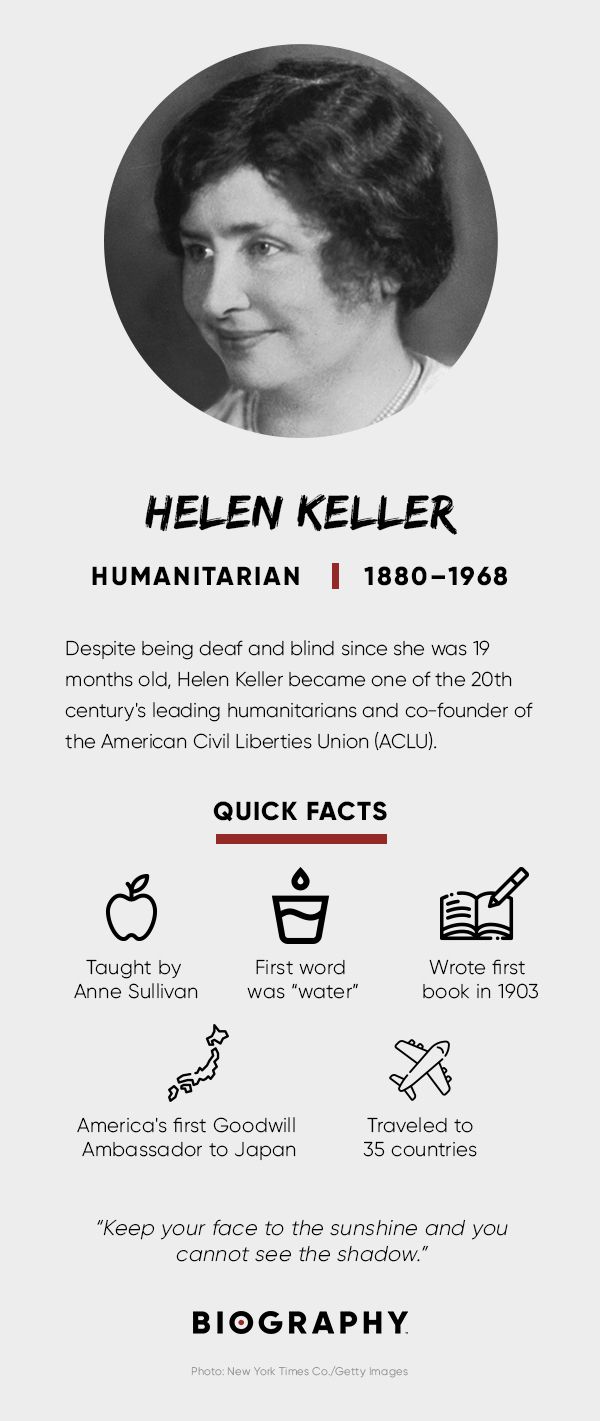

Helen Keller

Undeterred by deafness and blindness, Helen Keller rose to become a major 20 th century humanitarian, educator and writer. She advocated for the blind and for women’s suffrage and co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union.

Born on June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Keller was the older of two daughters of Arthur H. Keller, a farmer, newspaper editor, and Confederate Army veteran, and his second wife Katherine Adams Keller, an educated woman from Memphis. Several months before Helen’s second birthday, a serious illness—possibly meningitis or scarlet fever—left her deaf and blind. She had no formal education until age seven, and since she could not speak, she developed a system for communicating with her family by feeling their facial expressions.

Recognizing her daughter’s intelligence, Keller’s mother sought help from experts including inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who had become involved with deaf children. Ultimately, she was referred to Anne Sullivan, a graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind, who became Keller’s lifelong teacher and mentor. Although Helen initially resisted her, Sullivan persevered. She used touch to teach Keller the alphabet and to make words by spelling them with her finger on Keller’s palm. Within a few weeks, Keller caught on. A year later, Sullivan brought Keller to the Perkins School in Boston, where she learned to read Braille and write with a specially made typewriter. Newspapers chronicled her progress. At fourteen, she went to New York for two years where she improved her speaking ability, and then returned to Massachusetts to attend the Cambridge School for Young Ladies. With Sullivan’s tutoring, Keller was admitted to Radcliffe College, graduating cum laude in 1904. Sullivan went with her, helping Keller with her studies. (Impressed by Keller, Mark Twain urged his wealthy friend Henry Rogers to finance her education.)

Even before she graduated, Keller published two books, The Story of My Life (1902) and Optimism (1903), which launched her career as a writer and lecturer. She authored a dozen books and articles in major magazines, advocating for prevention of blindness in children and for other causes.

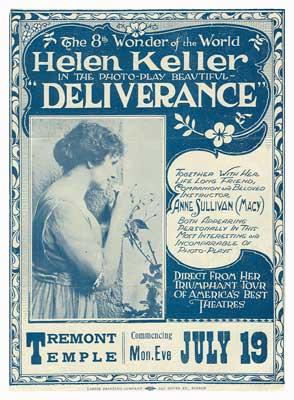

Sullivan married Harvard instructor and social critic John Macy in 1905, and Keller lived with them. During that time, Keller’s political awareness heightened. She supported the suffrage movement, embraced socialism, advocated for the blind and became a pacifist during World War I. Keller’s life story was featured in the 1919 film, Deliverance . In 1920, she joined Jane Addams, Crystal Eastman, and other social activists in founding the American Civil Liberties Union; four years later she became affiliated with the new American Foundation for the Blind in 1924.

After Sullivan’s death in 1936, Keller continued to lecture internationally with the support of other aides, and she became one of the world’s most-admired women (though her advocacy of socialism brought her some critics domestically). During World War II, she toured military hospitals bringing comfort to soldiers.

A second film on her life won the Academy Award in 1955; The Miracle Worker —which centered on Sullivan—won the 1960 Pulitzer Prize as a play and was made into a movie two years later. Lifelong activist, Keller met several US presidents and was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. She also received honorary doctorates from Glasgow, Harvard, and Temple Universities.

- “Helen Keller.” Perkins. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- “Helen Keller.” American Foundation for the Blind. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- "Helen Adams Keller." Dictionary of American Biography . New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988. U.S. History in Context . Accessed February 4, 2015.

- "Keller, Helen." UXL Encyclopedia of U.S. History . Sonia Benson, Daniel E. Brannen, Jr., and Rebecca Valentine. Vol. 5. Detroit: UXL, 2009. 847-849. U.S. History in Context . Accessed February 4, 2015.

- Ozick, Cynthia. “What Helen Keller Saw.” The New Yorker. June 16, 2003. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- Weatherford, Doris. American Women's History: An A to Z of People, Organizations, Issues, and Events . New York: Prentice Hall, 1994.

- PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA - Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2015. Date accessed.

Chicago - Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller." National Women's History Museum. 2015. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/helen-keller.

Helen Keller: Described and Captioned Educational Media

Helen Keller Biography, American Foundation for the Blind

Helen Keller, Perkins School for the Blind

Helen Keller Birthplace

Helen Keller International

The Miracle Worker (1962). Dir. Arthur Penn. (DVD) Film.

The Miracle Worker (2000). Dir. Nadia Tass. (DVD) Film.

Keller, Helen. The World I Live In . New York: NYRB Classics, 2004.

Ford, Carin. Helen Keller: Lighting the Way for the Blind and Deaf . Enslow Publishers, 2001.

Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller: A Life . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Related Biographies

Stacey abrams, abigail smith adams, jane addams, toshiko akiyoshi, related background, “when we sing, we announce our existence”: bernice johnson reagon and the american spiritual', mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, faith ringgold and her fabulous quilts.

Helen Keller

(1880-1968)

Who Was Helen Keller?

Helen Keller was an American educator, advocate for the blind and deaf and co-founder of the ACLU. Stricken by an illness at the age of 2, Keller was left blind and deaf. Beginning in 1887, Keller's teacher, Anne Sullivan, helped her make tremendous progress with her ability to communicate, and Keller went on to college, graduating in 1904. During her lifetime, she received many honors in recognition of her accomplishments.

Early Life and Family

The family was not particularly wealthy and earned income from their cotton plantation. Later, Arthur became the editor of a weekly local newspaper, the North Alabamian .

Keller was born with her senses of sight and hearing, and started speaking when she was just 6 months old. She started walking at the age of 1.

Loss of Sight and Hearing

Keller lost both her sight and hearing at just 19 months old. In 1882, she contracted an illness — called "brain fever" by the family doctor — that produced a high body temperature. The true nature of the illness remains a mystery today, though some experts believe it might have been scarlet fever or meningitis.

Within a few days after the fever broke, Keller's mother noticed that her daughter didn't show any reaction when the dinner bell was rung, or when a hand was waved in front of her face.

As Keller grew into childhood, she developed a limited method of communication with her companion, Martha Washington, the young daughter of the family cook. The two had created a type of sign language. By the time Keller was 7, they had invented more than 60 signs to communicate with each other.

During this time, Keller had also become very wild and unruly. She would kick and scream when angry, and giggle uncontrollably when happy. She tormented Martha and inflicted raging tantrums on her parents. Many family relatives felt she should be institutionalized.

Keller's Teacher, Anne Sullivan

Keller worked with her teacher Anne Sullivan for 49 years, from 1887 until Sullivan's death in 1936. In 1932, Sullivan experienced health problems and lost her eyesight completely. A young woman named Polly Thomson, who had begun working as a secretary for Keller and Sullivan in 1914, became Keller's constant companion upon Sullivan's death.

Looking for answers and inspiration, Keller's mother came across a travelogue by Charles Dickens, American Notes, in 1886. She read of the successful education of another deaf and blind child, Laura Bridgman, and soon dispatched Keller and her father to Baltimore, Maryland to see specialist Dr. J. Julian Chisolm.

After examining Keller, Chisolm recommended that she see Alexander Graham Bell , the inventor of the telephone, who was working with deaf children at the time. Bell met with Keller and her parents, and suggested that they travel to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston, Massachusetts.

There, the family met with the school's director, Michael Anaganos. He suggested Keller work with one of the institute's most recent graduates, Sullivan.

On March 3, 1887, Sullivan went to Keller's home in Alabama and immediately went to work. She began by teaching six-year-old Keller finger spelling, starting with the word "doll," to help Keller understand the gift of a doll she had brought along. Other words would follow.

At first, Keller was curious, then defiant, refusing to cooperate with Sullivan's instruction. When Keller did cooperate, Sullivan could tell that she wasn't making the connection between the objects and the letters spelled out in her hand. Sullivan kept working at it, forcing Keller to go through the regimen.

As Keller's frustration grew, the tantrums increased. Finally, Sullivan demanded that she and Keller be isolated from the rest of the family for a time, so that Keller could concentrate only on Sullivan's instruction. They moved to a cottage on the plantation.

In a dramatic struggle, Sullivan taught Keller the word "water"; she helped her make the connection between the object and the letters by taking Keller out to the water pump, and placing Keller's hand under the spout. While Sullivan moved the lever to flush cool water over Keller's hand, she spelled out the word w-a-t-e-r on Keller's other hand. Keller understood and repeated the word in Sullivan's hand. She then pounded the ground, demanding to know its "letter name." Sullivan followed her, spelling out the word into her hand. Keller moved to other objects with Sullivan in tow. By nightfall, she had learned 30 words.

In 1905, Sullivan married John Macy, an instructor at Harvard University, a social critic and a prominent socialist. After the marriage, Sullivan continued to be Keller's guide and mentor. When Keller went to live with the Macys, they both initially gave Keller their undivided attention. Gradually, however, Anne and John became distant to each other, as Anne's devotion to Keller continued unabated. After several years, the couple separated, though were never divorced.

In 1890, Keller began speech classes at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf in Boston. She would toil for 25 years to learn to speak so that others could understand her.

From 1894 to 1896, Keller attended the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf in New York City. There, she worked on improving her communication skills and studied regular academic subjects.

Around this time, Keller became determined to attend college. In 1896, she attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, a preparatory school for women.

As her story became known to the general public, Keller began to meet famous and influential people. One of them was the writer Mark Twain , who was very impressed with her. They became friends. Twain introduced her to his friend Henry H. Rogers, a Standard Oil executive.

Rogers was so impressed with Keller's talent, drive and determination that he agreed to pay for her to attend Radcliffe College. There, she was accompanied by Sullivan, who sat by her side to interpret lectures and texts. By this time, Keller had mastered several methods of communication, including touch-lip reading, Braille, speech, typing and finger-spelling.

Keller graduated, cum laude, from Radcliffe College in 1904, at the age of 24.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S HELEN KELLER FACT CARD

'The Story of My Life'

With the help of Sullivan and Macy, Sullivan's future husband, Keller wrote her first book, The Story of My Life . Published in 1905, the memoirs covered Keller's transformation from childhood to 21-year-old college student.

Social Activism

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Keller tackled social and political issues, including women's suffrage, pacifism, birth control and socialism.

After college, Keller set out to learn more about the world and how she could help improve the lives of others. News of her story spread beyond Massachusetts and New England. Keller became a well-known celebrity and lecturer by sharing her experiences with audiences, and working on behalf of others living with disabilities. She testified before Congress, strongly advocating to improve the welfare of blind people.

In 1915, along with renowned city planner George Kessler, she co-founded Helen Keller International to combat the causes and consequences of blindness and malnutrition. In 1920, she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union .

When the American Federation for the Blind was established in 1921, Keller had an effective national outlet for her efforts. She became a member in 1924, and participated in many campaigns to raise awareness, money and support for the blind. She also joined other organizations dedicated to helping those less fortunate, including the Permanent Blind War Relief Fund (later called the American Braille Press).

Soon after she graduated from college, Keller became a member of the Socialist Party, most likely due in part to her friendship with John Macy. Between 1909 and 1921, she wrote several articles about socialism and supported Eugene Debs, a Socialist Party presidential candidate. Her series of essays on socialism, entitled "Out of the Dark," described her views on socialism and world affairs.

It was during this time that Keller first experienced public prejudice about her disabilities. For most of her life, the press had been overwhelmingly supportive of her, praising her courage and intelligence. But after she expressed her socialist views, some criticized her by calling attention to her disabilities. One newspaper, the Brooklyn Eagle , wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development."

In 1946, Keller was appointed counselor of international relations for the American Foundation of Overseas Blind. Between 1946 and 1957, she traveled to 35 countries on five continents.

In 1955, at age 75, Keller embarked on the longest and most grueling trip of her life: a 40,000-mile, five-month trek across Asia. Through her many speeches and appearances, she brought inspiration and encouragement to millions of people.

'The Miracle Worker' Movie

Keller's autobiography, The Story of My Life , was used as the basis for 1957 television drama The Miracle Worker .

In 1959, the story was developed into a Broadway play of the same title, starring Patty Duke as Keller and Anne Bancroft as Sullivan. The two actresses also performed those roles in the 1962 award-winning film version of the play.

Awards and Honors

During her lifetime, she received many honors in recognition of her accomplishments, including the Theodore Roosevelt Distinguished Service Medal in 1936, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964, and election to the Women's Hall of Fame in 1965.

Keller also received honorary doctoral degrees from Temple University and Harvard University and from the universities of Glasgow, Scotland; Berlin, Germany; Delhi, India; and Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. She was named an Honorary Fellow of the Educational Institute of Scotland.

Keller died in her sleep on June 1, 1968, just a few weeks before her 88th birthday. Keller suffered a series of strokes in 1961 and spent the remaining years of her life at her home in Connecticut.

During her remarkable life, Keller stood as a powerful example of how determination, hard work, and imagination can allow an individual to triumph over adversity. By overcoming difficult conditions with a great deal of persistence, she grew into a respected and world-renowned activist who labored for the betterment of others.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Helen Adams Keller

- Birth Year: 1880

- Birth date: June 27, 1880

- Birth State: Alabama

- Birth City: Tuscumbia

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: American educator Helen Keller overcame the adversity of being blind and deaf to become one of the 20th century's leading humanitarians, as well as co-founder of the ACLU.

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Wright-Humason School for the Deaf

- Radcliffe College

- Cambridge School for Young Ladies

- Horace Mann School for the Deaf

- Death Year: 1968

- Death date: June 1, 1968

- Death State: Connecticut

- Death City: Easton

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Helen Keller Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/activists/helen-keller

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 6, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- Keep your face to the sunshine and you cannot see the shadow.

- One can never consent to creep when one feels an impulse to soar.

- Remember, no effort that we make to attain something beautiful is ever lost. Sometime, somewhere, somehow we shall find that which we seek.

- Gradually from naming an object we advance step by step until we have traversed the vast distance between our first stammered syllable and the sweep of thought in a line of Shakespeare.

- If it is true that the violin is the most perfect of musical instruments, then Greek is the violin of human thought.

- A happy life consists not in the absence, but in the mastery of hardships.

- The two greatest characters in the 19th century are Napoleon and Helen Keller. Napoleon tried to conquer the world by physical force and failed. Helen tried to conquer the world by power of mind — and succeeded!” (Mark Twain)

- The bulk of the world’s knowledge is an imaginary construction.

- We differ, blind and seeing, one from another, not in our senses, but in the use we make of them, in the imagination and courage with which we seek wisdom beyond the senses.

- [T]he mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!

- It is more difficult to teach ignorance to think than to teach an intelligent blind man to see the grandeur of Niagara.

- Everything has its wonders, even darkness and silence, and I learn, whatever state I may be in, therein to be content.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Suffragettes

Harriet Tubman

Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Emmeline Pankhurst

Carrie Chapman Catt

Kate Sheppard

Emily Davison

Molly Brown

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Helen Keller

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 18, 2019 | Original: April 14, 2010

Helen Keller was an author, lecturer, and crusader for the handicapped. Born in Tuscumbia, Alabama , She lost her sight and hearing at the age of nineteen months to an illness now believed to have been scarlet fever. Five years later, on the advice of Alexander Graham Bell , her parents applied to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston for a teacher, and from that school hired Anne Mansfield Sullivan. Through Sullivan’s extraordinary instruction, the little girl learned to understand and communicate with the world around her. She went on to acquire an excellent education and to become an important influence on the treatment of the blind and deaf.

Keller learned from Sullivan to read and write in Braille and to use the hand signals of the deaf-mute, which she could understand only by touch. Her later efforts to learn to speak were less successful, and in her public appearances she required the assistance of an interpreter to make herself understood. Nevertheless, her impact as educator, organizer, and fund-raiser was enormous, and she was responsible for many advances in public services to the handicapped.

With Sullivan repeating the lectures into her hand, Keller studied at schools for the deaf in Boston and New York City and graduated cum laude from Radcliffe College in 1904. Her unprecedented accomplishments in overcoming her disabilities made her a celebrity at an early age; at twelve she published an autobiographical sketch in the Youth’s Companion , and during her junior year at Radcliffe, she produced her first book, The Story of My Life , still in print in over fifty languages. Keller published four other books of her personal experiences as well as a volume on religion, one on contemporary social problems, and a biography of Anne Sullivan. She also wrote numerous articles for national magazines on the prevention of blindness and the education and special problems of the blind.

In addition to her many appearances on the lecture circuit, Keller in 1918 made a movie in Hollywood, Deliverance , to dramatize the plight of the blind and during the next two years supported herself and Sullivan on the vaudeville stage. She also spoke and wrote in support of women’s rights and other liberal causes and in 1940 strongly backed the United States’ entry into World War II .

In 1924, Keller joined the staff of the newly formed American Foundation for the Blind as an adviser and fund-raiser. Her international reputation and warm personality enabled her to enlist the support of many wealthy people, and she secured large contributions from Henry Ford , John D. Rockefeller , and leaders of the motion picture industry. When the AFB established a branch for the overseas blind, it was named Helen Keller International. Keller and Sullivan were the subjects of a Pulitzer Prize-winning play, The Miracle Worker, by William Gibson, which opened in New York in 1959 and became a successful Hollywood film in 1962.

Widely honored throughout the world and invited to the White House by every U.S. president from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon B. Johnson , Keller altered the world’s perception of the capacities of the handicapped. More than any act in her long life, her courage, intelligence, and dedication combined to make her a symbol of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

As a name that is known worldwide, Helen Keller is a symbol of courage and hope. Yet, she is much more than a name or a symbol. She was a woman of astounding intelligence, unwavering determination, unbelievable courage and insurmountable achievement. She dedicated her entire life to the betterment of others, helping people see the potential in their own lives, as well as the lives of people around them. She became the first blind-deaf person to effectively communicate with the sighted and hearing world. In so doing, she became an international celebrity from the age of eight, even before the era of mass communications.

Helen Adams Keller was born on June, 27, 1880 to Arthur H. Keller and Kate Adams Keller in the small, north Alabama town of Tuscumbia. When she was only 19 months old, she contracted a fever that would leave her both deaf and blind. At almost seven years of age, her mother and father took her to see the famous inventor, Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, who advised them to hire a governess for the child.

On March 3, 1887, Anne Mansfield Sullivan, a partially blind, twenty-one year old woman, arrived in Tuscumbia to be Helen’s teacher. With patience, understanding and love, Miss Sullivan was able to save Helen from her “double dungeon of darkness and silence”.

With the help of her beloved teacher, Helen quickly and eagerly learned to read and write. After attending high school at the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, Massachusetts, Miss Sullivan helped Helen enroll in Radcliffe College, formerly the all-male Harvard College’s coordinate institution for female students. With remarkable determination, Helen graduated Cum Laude in 1904, becoming the first deaf-blind person to graduate from college. At that time, she announced that her life would be dedicated to the amelioration of blindness.

After graduation, Helen Keller began her life’s work of helping blind and deaf-blind people. She appeared before state and national legislatures and international forums. She regarded herself as a “world citizen”, visiting 39 countries on five continents between 1939 and 1957. She published 14 books and produced numerous articles. Not only was she out-spoken on the needs and issues affecting her fellow deaf and deaf-blind comrades, Helen was also a valiant supporter of women’s suffrage, civil rights, and the labor union movement, as well as many other worthwhile and important causes.

Helen Keller’s pilgrimage from Tuscumbia, Alabama to worldwide recognition is an inspiring story that took her from silence and darkness to a life of vision and advocacy. Against overwhelming odds, she waged a seemingly impossible battle to re-enter the world she had lost. She is one of the most powerful symbols of triumph over adversity our era has produced, leading Winston Churchill to call her, “The greatest woman of our age”.

Helen Keller won numerous honors, including several honorary university degrees, the Lions Humanitarian Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the French Legion of Honor and election to the Women’s Hall of Fame. She also met every President of the United States, from Calvin Coolidge to John F. Kennedy.

Helen died on June 1, 1968 at the age of 87. She was laid to rest in St. Joseph’s Chapel, at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Her legacy reminds us that with faith and courage, we can overcome obstacles in our own lives. With endurance and determination, we can help to better the lives of those around us. With love and patience, we can leave this world a better place.

In 1968, Senator Lister Hill eulogized her as “One of the few persons not born to die”. She will always be known as “The first lady of courage”.

View photos of Helen Keller and those she touched.

View the chronology of Helen Keller’s life.

“To keep our faces toward change and behave like free spirits in the presence of fate, is strength un-defeatable.” -Helen Keller

Featured Reading

The Foundation understands that the message of courage and selflessness implied in Helen Keller’s legacy is and always will be important to transmit to new generations – both for its own value, and as a means to promote public understanding of vision and hearing research.

Continue Reading…

Help Advance Research

The Foundation’s research discoveries have the potential to save substantial sight and to reduce healthcare expenditures by $50 million annually. The research efforts have also generated more than 700 publications and presentations and earned a particularly strong reputation in the areas of eye trauma and surgical treatment of the center of vision, the macula. The Helen Keller Prize for Vision Research was established to honor research excellence and is now commonly regarded as the premier award in vision research.

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,586 free eBooks

- 6 by Helen Keller

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

.cls-1{fill:#0966a9 !important;}.cls-2{fill:#8dc73f;}.cls-3{fill:#f79122;}

Your support helps VCU Libraries make the Social Welfare History Project freely available to all. A generous challenge grant will double your impact.

Keller, Helen

Helen keller (june 27, 1880 – june 1, 1968) – advocate for the deaf and blind, author, socialist and suffragist.

Introduction: Helen Adams Keller was born a healthy child in Tuscumbia, Alabama on June 27, 1880 in a white, frame cottage called “Ivy Green.” On her father’s side she was descended from Alexander Spottswood, a colonial governor of Virginia, who was connected with the Lees and other Southern families. On her mother’s side, she was related to a number of prominent New England families, including the Hales, the Everetts, and the Adamses. Her father, Captain Arthur Keller, was the editor of a newspaper, the North Alabamian . Captain Keller also had a strong interest in public life and was an influential figure in his own community. In 1885, under the Cleveland administration, he was appointed Marshal of North Alabama.

The illness that struck the infant Helen Keller, and left her deaf and blind before she learned to speak, was diagnosed as brain fever at the time; perhaps it was scarlet fever. As Helen Keller grew from infancy into childhood she was wild and unruly, and had little real understanding of the world around her.

A New Beginning : Sometime in March 1887, when Helen Keller was a few months short of seven years old, Anne Mansfield Sullivan came to Tuscumbia to be her teacher. Miss Sullivan, a 20-year-old graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind, who had regained useful sight through a series of operations, had come to the Keller’s through the sympathetic interest of Alexander Graham Bell. That was the day Miss Keller would always call “The most important day I can remember in my life.”

From that fateful day, the two—teacher and pupil—were inseparable until the death of the former in 1936. How Miss Sullivan turned the uncontrolled child into a responsible human being and succeeded in awakening and stimulating her marvelous mind is familiar to millions, most notably through William Gibson’s play and film, “The Miracle Worker,” Miss Keller’s autobiography of her early years, The Story of My Life , and Joseph Lash’s Helen and Teacher.

Miss Sullivan began her task with a doll that the children at Perkins had made for her to take to Helen. By spelling “d-o-l-l” into the child’s hand, she hoped to teach her to connect objects with letters. Helen quickly learned to form the letters correctly and in the correct order, but did not know she was spelling a word, or even that words existed. In the days that followed she learned to spell a great many more words in this uncomprehending way.

One day she and “Teacher”—as Helen always called her—went to the outdoor pump. Miss Sullivan started to draw water and put Helen’s hand under the spout. As the cool water gushed over one hand, she spelled into the other hand the word “w-a-t-e-r” first slowly, then rapidly. Suddenly, the signals had meaning in Helen’s mind. She knew that “water” meant the wonderful cool substance flowing over her hand. Quickly, she stopped and touched the earth and demanded its letter name and by nightfall she had learned 30 words.

Thus began Helen Keller’s education. She proceeded quickly to master the alphabet, both manual and in raised print for blind readers, and gained facility in reading and writing. In 1890, when she was just 10, she expressed a desire to learn to speak. Somehow she had found out that a little deaf-blind girl in Norway had acquired that ability. Miss Sarah Fuller of the Horace Mann School was her first speech teacher.

Even when she was a little girl, Helen Keller said, “Someday I shall go to college.” And go to college she did. In 1898 she entered the Cambridge School for Young Ladies to prepare for Radcliffe College. She entered Radcliffe in the fall of 1900 and received a bachelor of arts degree cum laude in 1904. Throughout these years and until her own death in 1936, Anne Sullivan was always by Helen’s side, laboriously spelling book after book and lecture after lecture, into her pupil’s hand.

Helen Keller’s formal schooling ended when she received her B.A. degree, but throughout her life she continued to study and stay informed on all matters of importance to modern people. In recognition of her wide knowledge and many scholarly achievements, she received honorary doctoral degrees from Temple University and Harvard University and from the Universities of Glasgow, Scotland; Berlin, Germany; Delhi, India; and Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. She was also an Honorary Fellow of the Educational Institute of Scotland.

Anne Sullivan’s marriage, in 1905, to John Macy, an eminent critic and prominent socialist, caused no change in the teacher-pupil relationship. Helen went to live with the Macy’s and both husband and wife unstintingly gave their time to help her with her studies and other activities.

Helen Keller the Author : While still a student at Radcliffe, Helen Keller began a writing career that was to continue on and off for 50 years. In 1903, The Story of My Life , which had first appeared in serial form in the Ladies Home Journal , appeared in book form. This was always to be the most popular of her works and today is available in more than 50 languages, including Marathi, Pushtu, Tagalog, and Vedu. It is also available in several paperback editions in the United States.

Miss Keller’s other published works include “Optimism,” an essay; The World I Live In ; The Song of the Stone Wall ; Out of the Dark ; My Religion ; Midstream—My Later Life ; Peace at Eventide ; Helen Keller in Scotland ; Helen Keller’s Journal ; Let Us Have Faith; Teacher, Anne Sullivan Macy; and The Open Door.

In addition, she was a frequent contributor to magazines and newspapers, writing most frequently on blindness, deafness, socialism, social issues, and women’s rights. She used a braille typewriter to prepare her manuscripts and then copied them on a regular typewriter.

Honors and Recognition : During her lifetime, Helen Keller received awards of great distinction too numerous to recount fully here. An entire room, called the Helen Keller Archives at the American Foundation for the Blind in New York City, is devoted to their preservation. These awards include Brazil’s Order of the Southern Cross; Japan’s Sacred Treasure; the Philippines’ Golden Heart; Lebanon’s Gold Medal of Merit; and her own country’s highest honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Most of these awards were bestowed on her in recognition of the stimulation her example and presence gave to work for the blind in those countries. In 1933 she was elected to membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters. During the Louis Braille Centennial Commemoration in 1952, Miss Keller was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor at a ceremony in the Sorbonne.

On the 50th anniversary of her graduation, Radcliffe College granted her its Alumnae Achievement Award. Her Alma Mater also showed its pride in her by dedicating the Helen Keller Garden in her honor and by naming a fountain in the garden for Anne Sullivan Macy.

Miss Keller also received the Americas Award for Inter-American Unity, the Gold Medal Award from the National Institute of Social Sciences, the National Humanitarian Award from Variety Clubs International, and many others. She held honorary memberships in scientific societies and philanthropic organizations throughout the world.

Yet another honor came to Helen Keller in 1954 when her birthplace, “Ivy Green,” in Tuscumbia, was made a permanent shrine. It was dedicated on May 7, 1954 with officials of the American Foundation for the Blind and many other agencies and organizations present. In conjunction with this event, the premiere of Miss Keller’s film biography, “The Unconquered,” produced by Nancy Hamilton and narrated by Katharine Cornell, was held in the nearby city of Birmingham. The film was later renamed “Helen Keller in Her Story” and in 1955 won an “Oscar”—the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences award as the best feature-length documentary film of the year.

Miss Keller was indirectly responsible for two other “Oscars” a few years later when Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke won them for their portrayals of Anne Sullivan and Helen Keller in the film version of “The Miracle Worker.”

More rewarding to her than the many honors she received were the acquaintances and friendships Helen Keller made with most of the leading personalities of her time. She met many world figures, from Grover Cleveland to Charlie Chaplin, Nehru, and John F. Kennedy. Among those she met, she counted many personal friends including Katharine Cornell, Van Wyck Brooks, Alexander Graham Bell, and Jo Davidson. Two friends from her early youth, Mark Twain and William James, expressed beautifully what most of her friends felt about her. Mark Twain said, “The two most interesting characters of the 19th century are Napoleon and Helen Keller.” William James wrote, “But whatever you were or are, you’re a blessing!”

Helping Others: As broad and wide ranging as her interests were, Helen Keller never lost sight of the needs of other blind and deaf-blind individuals. From her youth, she was always willing to help them by appearing before legislatures, giving lectures, writing articles, and above all, by her own example of what a severely disabled person could accomplish. When the American Foundation for the Blind, the national clearinghouse for information on blindness, was established in 1921, she at last had an effective national outlet for her efforts. From 1924 until her death she was a member of the Foundation staff, serving as counselor on national and international relations. It was also in 1924 that Miss Keller began her campaign to raise the “Helen Keller Endowment Fund” for the Foundation. Until her retirement from public life, she was tireless in her efforts to make the Fund adequate for the Foundation’s needs.

Of all her contributions to the Foundation, Miss Keller was perhaps most proud of her assistance in the formation in 1946 of its special service for deaf-blind persons. She was, of course, deeply concerned for this group of people and was always searching for ways to help those “less fortunate than myself.”

Helen Keller was as interested in the welfare of blind persons in other countries as she was for those in her own country; conditions in the underdeveloped and war-ravaged nations were of particular concern. Her active participation in this area of work for the blind began as early as 1915 when the Permanent Blind War Relief Fund, later called the American Braille Press, was founded. She was a member of its first board of directors.

When the American Braille Press became the American Foundation for Overseas Blind (now Helen Keller International) in 1946, Miss Keller was appointed counselor on international relations. It was then that she began the globe-circling tours on behalf of the blind for which she was so well known during her later years. During seven trips between 1946 and 1957 she visited 35 countries on five continents. In 1955, when she was 75 years old, she embarked on one of her longest and most grueling journeys, a 40,000-mile, five-month-long tour through Asia. Wherever she traveled, she brought encouragement to millions of blind people, and many of the efforts to improve conditions among blind people outside the U.S. can be traced directly to her visits.

During her lifetime, Helen Keller lived in many different places—Tuscumbia, Alabama; Cambridge and Wrentham, Massachusetts; Forest Hills, New York, but perhaps her favorite residence was her last, the house in Easton, Connecticut she called “Arcan Ridge.” She moved to this white, frame house surrounded by mementos of her rich and busy life after her beloved “Teacher’s” death in 1936. And it was Arcan Ridge she called home for the rest of her life. “Teacher’s” death, although it left her with a heavy heart, did not leave Helen alone. Polly Thomson, a Scotswoman who joined the Keller household in 1914, assumed the task of assisting Helen with her work. After Miss Thomson’s death in 1960, a devoted nurse-companion, Mrs. Winifred Corbally, assisted her until her last day.

Helen Keller made her last major public appearance in 1961 at a Washington, DC, Lions Clubs International Foundation meeting. At that meeting she received the Lions Humanitarian Award for her lifetime of service to humanity and for providing the inspiration for the adoption by Lions Clubs International Foundation of their sight conservation and aid to blind programs. During that visit to Washington, she also called on President Kennedy at the White House. After that White House visit, a reporter asked her how many of our presidents she had met. She replied that she did not know how many, but that she had met all of them since Grover Cleveland!

After 1961, Helen Keller lived quietly at Arcan Ridge. She saw her family, close friends, and associates from the American Foundation for the Blind and the American Foundation for Overseas Blind, and spent much time reading. Her favorite books were the Bible and volumes of poetry and philosophy.

Despite her retirement from public life, Helen Keller was not forgotten. In 1964 she received the previously mentioned Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1965, she was one of 20 elected to the Women’s Hall of Fame at the New York World’s Fair. Miss Keller and Eleanor Roosevelt received the most votes among the 100 nominees. Helen Keller is now honored in The Hall of Fame for Leaders and Legends of the Blindness Field.

Helen Keller died on June 1, 1968, at Arcan Ridge, a few weeks short of her 88th birthday. Her ashes were placed next to her beloved companions, Anne Sullivan Macy and Polly Thomson, in the St. Joseph’s Chapel of Washington Cathedral. On that occasion a public memorial service was held in the Cathedral. It was attended by her family and friends, government officials, prominent persons from all walks of life, and delegations from most of the organizations for the blind and deaf.

In his eulogy, Senator Lister Hill of Alabama expressed the feelings of the whole world when he said of Helen Keller, “She will live on, one of the few, the immortal names not born to die. Her spirit will endure as long as man can read and stories can be told of the woman who showed the world there are no boundaries to courage and faith.”

This work may also be read through the Internet Archive .

For further reading:

The Story of My Life

“ Optimism ”

The World I Live In

The Song of the Stone Wall

Out of the Dark

My Religion

Midstream—My Later Life

Peace at Eventide

Helen Keller in Scotland

Helen Keller’s Journal

Republished from : The American Foundation for the Blind

Note : Under the terms of her will, Helen Keller selected the American Foundation for the Blind as the repository of her papers and memorabilia.

How to Cite this Article (APA Format): The American Foundation for the Blind (2016). Helen Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) – Advocate for the deaf and blind, author, socialist, and suffragist. Social Welfare History Project . Retrieved [date accessed] from https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/people/keller-helen/

0 Replies to “Keller, Helen”

Comments for this site have been disabled. Please use our contact form for any research questions.

Biography of Helen Keller, Deaf and Blind Spokesperson and Activist

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

- B.A., English Literature, University of Houston

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880–June 1, 1968) was a groundbreaking exemplar and advocate for the blind and deaf communities. Blind and deaf from a nearly fatal illness at 19 months old, Helen Keller made a dramatic breakthrough at the age of 6 when she learned to communicate with the help of her teacher, Annie Sullivan. Keller went on to live an illustrious public life, inspiring people with disabilities and fundraising, giving speeches, and writing as a humanitarian activist.

Fast Facts: Helen Keller

- Known For : Blind and deaf from infancy, Helen Keller is known for her emergence from isolation, with the help of her teacher Annie Sullivan, and for a career of public service and humanitarian activism.

- Born : June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama

- Parents : Captain Arthur Keller and Kate Adams Keller

- Died : June 1, 1968 in Easton Connecticut

- Education : Home tutoring with Annie Sullivan, Perkins Institute for the Blind, Wright-Humason School for the Deaf, studies with Sarah Fuller at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf, The Cambridge School for Young Ladies, Radcliffe College of Harvard University

- Published Works : The Story of My Life, The World I Live In, Out of the Dark, My Religion, Light in My Darkness, Midstream: My Later Life

- Awards and Honors : Theodore Roosevelt Distinguished Service Medal in 1936, Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964, election to the Women's Hall of Fame in 1965, an honorary Academy Award in 1955 (as the inspiration for the documentary about her life), countless honorary degrees

- Notable Quote : "The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen, nor touched ... but are felt in the heart."

Early Childhood

Helen Keller was born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama to Captain Arthur Keller and Kate Adams Keller. Captain Keller was a cotton farmer and newspaper editor and had served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War . Kate Keller, 20 years his junior, had been born in the South, but had roots in Massachusetts and was related to founding father John Adams .

Helen was a healthy child until she became seriously ill at 19 months. Stricken with an illness that her doctor called "brain fever," Helen was not expected to survive. The crisis was over after several days, to the great relief of the Kellers. However, they soon learned that Helen had not emerged from the illness unscathed. She was left blind and deaf. Historians believe that Helen had contracted either scarlet fever or meningitis.

The Wild Childhood Years

Frustrated by her inability to express herself, Helen Keller frequently threw tantrums that included breaking dishes and even slapping and biting family members. When Helen, at age 6, tipped over the cradle holding her baby sister, Helen's parents knew something had to be done. Well-meaning friends suggested that she be institutionalized, but Helen's mother resisted that notion.

Soon after the incident with the cradle, Kate Keller read a book by Charles Dickens about the education of Laura Bridgman. Laura was a deaf-blind girl who had been taught to communicate by the director of the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston. For the first time, the Kellers felt hopeful that Helen could be helped as well.

The Guidance of Alexander Graham Bell

During a visit to a Baltimore eye doctor in 1886, the Kellers received the same verdict they had heard before. Nothing could be done to restore Helen's eyesight. The doctor, however, advised the Kellers that Helen might benefit from a visit with the famous inventor Alexander Graham Bell in Washington, D.C.

Bell's mother and wife were deaf and he had devoted himself to improving life for the deaf, inventing several assistive devices for them. Bell and Helen Keller got along very well and would later develop a lifelong friendship.

Bell suggested that the Kellers write to the director of the Perkins Institute for the Blind, where Laura Bridgman, now an adult, still resided. The director wrote the Kellers back, with the name of a teacher for Helen: Annie Sullivan .

Annie Sullivan Arrives

Helen Keller's new teacher had also lived through difficult times. Annie Sullivan had lost her mother to tuberculosis when she was 8. Unable to care for his children, her father sent Annie and her younger brother Jimmie to live in the poorhouse in 1876. They shared quarters with criminals, prostitutes, and the mentally ill.

Young Jimmie died of a weak hip ailment only three months after their arrival, leaving Annie grief-stricken. Adding to her misery, Annie was gradually losing her vision to trachoma, an eye disease. Although not completely blind, Annie had very poor vision and would be plagued with eye problems for the rest of her life.

When she was 14, Annie begged visiting officials to send her to school. She was lucky, for they agreed to take her out of the poorhouse and send her to the Perkins Institute. Annie had a lot of catching up to do. She learned to read and write, then later learned braille and the manual alphabet (a system of hand signs used by the deaf).

After graduating first in her class, Annie was given the job that would determine the course of her life: teacher to Helen Keller. Without any formal training to teach a deaf-blind child, 20-year-old Annie Sullivan arrived at the Keller home on March 3, 1887. It was a day that Helen Keller later referred to as "my soul's birthday."

A Battle of Wills

Teacher and pupil were both very strong-willed and frequently clashed. One of the first of these battles revolved around Helen's behavior at the dinner table, where she roamed freely and grabbed food from the plates of others.

Dismissing the family from the room, Annie locked herself in with Helen. Hours of struggle ensued, during which Annie insisted Helen eat with a spoon and sit in her chair.

In order to distance Helen from her parents, who gave in to her every demand, Annie proposed that she and Helen move out of the house temporarily. They spent about two weeks in the "annex," a small house on the Keller property. Annie knew that if she could teach Helen self-control, Helen would be more receptive to learning.

Helen fought Annie on every front, from getting dressed and eating to going to bed at night. Eventually, Helen resigned herself to the situation, becoming calmer and more cooperative.

Now the teaching could begin. Annie constantly spelled words into Helen's hand, using the manual alphabet to name the items she handed to Helen. Helen seemed intrigued but did not yet realize that what they were doing was more than a game.

Helen Keller's Breakthrough

On the morning of April 5, 1887, Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller were outside at the water pump, filling a mug with water. Annie pumped the water over Helen's hand while repeatedly spelling “w-a-t-e-r” into her hand. Helen suddenly dropped the mug. As Annie later described it, "a new light came into her face." She understood.

All the way back to the house, Helen touched objects and Annie spelled their names into her hand. Before the day was over, Helen had learned 30 new words. It was just the beginning of a very long process, but a door had been opened for Helen.

Annie also taught her how to write and how to read braille. By the end of that summer, Helen had learned more than 600 words.

Annie Sullivan sent regular reports on Helen Keller's progress to the director of the Perkins Institute. On a visit to the Perkins Institute in 1888, Helen met other blind children for the first time. She returned to Perkins the following year and stayed for several months of study.

High School Years

Helen Keller dreamed of attending college and was determined to get into Radcliffe , a women's university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. However, she would first need to complete high school.

Helen attended a high school for the deaf in New York City, then later transferred to a school in Cambridge. She had her tuition and living expenses paid for by wealthy benefactors.

Keeping up with school work challenged both Helen and Annie. Copies of books in braille were rarely available, requiring that Annie read the books, then spell them into Helen's hand. Helen would then type out notes using her braille typewriter. It was a grueling process.

Helen withdrew from the school after two years, completing her studies with a private tutor. She gained admission to Radcliffe in 1900, making her the first deaf-blind person to attend college.

Life as a Coed

College was somewhat disappointing for Helen Keller. She was unable to form friendships both because of her limitations and the fact that she lived off campus, which further isolated her. The rigorous routine continued, in which Annie worked at least as much as Helen. As a result, Annie suffered severe eyestrain.

Helen found the courses very difficult and struggled to keep up with her workload. Although she detested math, Helen did enjoy English classes and received praise for her writing. Before long, she would be doing plenty of writing.

Editors from Ladies' Home Journal offered Helen $3,000, an enormous sum at the time, to write a series of articles about her life.

Overwhelmed by the task of writing the articles, Helen admitted she needed help. Friends introduced her to John Macy, an editor and English teacher at Harvard . Macy quickly learned the manual alphabet and began to work with Helen on editing her work.

Certain that Helen's articles could successfully be turned into a book, Macy negotiated a deal with a publisher and "The Story of My Life" was published in 1903 when Helen was only 22 years old. Helen graduated from Radcliffe with honors in June 1904.

Annie Sullivan Marries John Macy

John Macy remained friends with Helen and Annie after the book's publication. He found himself falling in love with Annie Sullivan, although she was 11 years his senior. Annie had feelings for him as well, but wouldn't accept his proposal until he assured her that Helen would always have a place in their home. They were married in May 1905 and the trio moved into a farmhouse in Massachusetts.

The pleasant farmhouse was reminiscent of the home Helen had grown up in. Macy arranged a system of ropes out in the yard so that Helen could safely take walks by herself. Soon, Helen was at work on her second memoir, "The World I Live In," with John Macy as her editor.

By all accounts, although Helen and Macy were close in age and spent a lot of time together, they were never more than friends.

An active member of the Socialist Party, John Macy encouraged Helen to read books on socialist and communist theory. Helen joined the Socialist Party in 1909 and she also supported the women's suffrage movement .

Helen's third book, a series of essays defending her political views, did poorly. Worried about their dwindling funds, Helen and Annie decided to go on a lecture tour.

Helen and Annie Go on the Road

Helen had taken speaking lessons over the years and had made some progress, but only those closest to her could understand her speech. Annie would need to interpret Helen's speech for the audience.

Another concern was Helen's appearance. She was very attractive and always well dressed, but her eyes were obviously abnormal. Unbeknownst to the public, Helen had her eyes surgically removed and replaced by prosthetic ones prior to the start of the tour in 1913.

Prior to this, Annie made certain that the photographs were always taken of Helen's right profile because her left eye protruded and was obviously blind, whereas Helen appeared almost normal on the right side.

The tour appearances consisted of a well-scripted routine. Annie spoke about her years with Helen and then Helen spoke, only to have Annie interpret what she had said. At the end, they took questions from the audience. The tour was successful, but exhausting for Annie. After taking a break, they went back on tour two more times.

Annie's marriage suffered from the strain as well. She and John Macy separated permanently in 1914. Helen and Annie hired a new assistant, Polly Thomson, in 1915, in an effort to relieve Annie of some of her duties.

Helen Finds Love

In 1916, the women hired Peter Fagan as a secretary to accompany them on their tour while Polly was out of town. After the tour, Annie became seriously ill and was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

While Polly took Annie to a rest home in Lake Placid, plans were made for Helen to join her mother and sister Mildred in Alabama. For a brief time, Helen and Peter were alone together at the farmhouse, where Peter confessed his love for Helen and asked her to marry him.

The couple tried to keep their plans a secret, but when they traveled to Boston to obtain a marriage license, the press obtained a copy of the license and published a story about Helen's engagement.

Kate Keller was furious and brought Helen back to Alabama with her. Although Helen was 36 years old at the time, her family was very protective of her and disapproved of any romantic relationship.

Several times, Peter attempted to reunite with Helen, but her family would not let him near her. At one point, Mildred's husband threatened Peter with a gun if he did not get off his property.

Helen and Peter were never together again. Later in life, Helen described the relationship as her "little island of joy surrounded by dark waters."

The World of Showbiz

Annie recovered from her illness, which had been misdiagnosed as tuberculosis, and returned home. With their financial difficulties mounting, Helen, Annie, and Polly sold their house and moved to Forest Hills, New York in 1917.

Helen received an offer to star in a film about her life, which she readily accepted. The 1920 movie, "Deliverance," was absurdly melodramatic and did poorly at the box office.

In dire need of a steady income, Helen and Annie, now 40 and 54 respectively, next turned to vaudeville. They reprised their act from the lecture tour, but this time they did it in glitzy costumes and full stage makeup, alongside various dancers and comedians.

Helen enjoyed the theater, but Annie found it vulgar. The money, however, was very good and they stayed in vaudeville until 1924.

American Foundation for the Blind

That same year, Helen became involved with an organization that would employ her for much of the rest of her life. The newly-formed American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) sought a spokesperson and Helen seemed the perfect candidate.

Helen Keller drew crowds whenever she spoke in public and became very successful at raising money for the organization. Helen also convinced Congress to approve more funding for books printed in braille.

Taking time off from her duties at the AFB in 1927, Helen began work on another memoir, "Midstream," which she completed with the help of an editor.

Losing 'Teacher' and Polly

Annie Sullivan's health deteriorated over several years' time. She became completely blind and could no longer travel, leaving both women entirely reliant on Polly. Annie Sullivan died in October 1936 at the age of 70. Helen was devastated to have lost the woman whom she had known only as "Teacher," and who had given so much to her.

After the funeral, Helen and Polly took a trip to Scotland to visit Polly's family. Returning home to a life without Annie was difficult for Helen. Life was made easier when Helen learned that she would be taken care of financially for life by the AFB, which built a new home for her in Connecticut.

Helen continued her travels around the world through the 1940s and 1950s accompanied by Polly, but the women, now in their 70s, began to tire of travel.

In 1957, Polly suffered a severe stroke. She survived, but had brain damage and could no longer function as Helen's assistant. Two caretakers were hired to come and live with Helen and Polly. In 1960, after spending 46 years of her life with Helen, Polly Thomson died.

Later Years

Helen Keller settled into a quieter life, enjoying visits from friends and her daily martini before dinner. In 1960, she was intrigued to learn of a new play on Broadway that told the dramatic story of her early days with Annie Sullivan. "The Miracle Worker" was a smash hit and was made into an equally popular movie in 1962.

Strong and healthy all of her life, Helen became frail in her 80s. She suffered a stroke in 1961 and developed diabetes.

On June 1, 1968, Helen Keller died in her home at the age of 87 following a heart attack. Her funeral service, held at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., was attended by 1,200 mourners.

Helen Keller was a groundbreaker in her personal and public lives. Becoming a writer and lecturer with Annie while blind and deaf was an enormous accomplishment. Helen Keller was the first deaf-blind individual to earn a college degree.

She was an advocate for communities of people with disabilities in many ways, raising awareness through her lecture circuits and books and raising funds for the American Foundation for the Blind. Her political work included helping to found the American Civil Liberties Union and advocacy for increased funding for braille books and for women's suffrage.

She met with every U.S. president from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon Johnson. While she was still alive, in 1964, Helen received the highest honor awarded to a U.S. citizen, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, from President Lyndon Johnson .

Helen Keller remains a source of inspiration to all people for her enormous courage overcoming the obstacles of being both deaf and blind and for her ensuing life of humanitarian selfless service.

- Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller: A Life. University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Keller, Helen. Midstream: My Later Life . Nabu Press, 2011.

- Julia Ward Howe Biography

- Top 100 Women of History

- Helen Keller Quotes

- Biography of Sharpshooter Annie Oakley

- Act 1 Plot Summary of Arthur Miller's "All My Sons"

- Life and Work of Anni Albers, Master of Modernist Weaving

- Helen of Troy in the Iliad of Homer

- June Themes, Holiday Activities, and Events for Elementary Students

- Teaching Students Identified with Interpersonal Intelligence

- Biography of Hilda Doolittle, Poet, Translator, and Memoirist

- Biography of Patricia Bath, American Doctor and Inventor

- Biography of Annie Jump Cannon, Classifier of Stars

- Annie Besant, Heretic

- April Writing Prompts

- Banned Books: History and Quotes

- Helen Pitts Douglass

Helen Keller

- Bibliography /

- Filmography /

Helen Keller’s brief career in silent film began when she was approached by historian and author of the popular Photographic History of the Civil War Francis Trevelyan Miller, who hoped to write a motion picture script based on Keller’s life and work. Miller, in a January 1918 letter to Keller, argued that the motion pictures were “a universal language” and an opportunity for the deaf-blind author and activist to share her political and social message with the world. Keller, who was often frustrated by the limitations of biographical interest in her life, responded to the broader vision of the project and wrote, typing in her distinctive typing style, back to him in April: “So according to your conception, the interest of our life-drama will not be confined to the events of my life, but will be spread out all round the world [… ] and bring many vital truths home to the hearts of the people, truths that shall hasten the deliverance of the human race.” This rhetoric becomes more pointed in the context of Keller’s public life; she had been a politically active Socialist since 1912.

With money raised through Keller’s philanthropic connections and George Foster Platt hired as director for the film, the Helen Keller Film Corporation was created in May 1918. Miller became its president, and production of the film Deliverance began. Despite the alleged universality of the medium, everyone involved found that significant translations were necessary for the director to communicate with the film’s star, Keller herself. After Anne Sullivan Macy had interpreted Platt’s directions for Keller, or she had read his lips with her hands, Platt would tap on the floor during actual filming to cue Keller’s movements and facial expressions. Reports of this process appear in various publicity articles, but the most detailed descriptions of the film production, and its difficulties, come from Keller’s memoir Midstream and her correspondence from the period.

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy; Sullivan signs as Charlie Chaplin shoots Shoulder Arms (1918). Courtesy of the Bison Archives.

Polly Thompson, Anne Sullivan Macy, Helen Keller, and Charlie Chaplin on the set of Shoulder Arms (1918). Courtesy of American Foundation for the Blind.

In her 1929 biography Midstream , Keller writes of an initial “exaltation” over the decision to attempt “a mystical unfoldment of my story” rather than “a matter of fact narrative” (195–200), but after Keller and Macy viewed a version of the film, with Macy finger spelling descriptions of the action and images, Macy wrote Miller with a list of objections. Macy and Keller revised and edited the existing titles and requested the editing or removal of various scenes. Meanwhile, Keller contacted the film’s investors, invoking in an April 1919 letter the “right to reject the picture if it does not satisfy us.” For the investors Keller described, indignantly, “a scene called ‘The Council Chamber,’ where all the great generals, kings and statesmen are assembled in a sort of peace conference. I enter … and proclaim the Rights of Man rather feebly. There is no foundation in fact for such a scene, and the symbolism is not apparent. We want it omitted. This scene is followed by a Pageant with me on horseback, leading all the peoples of the world to freedom—or something. It is altogether too hilarious to typify the struggles of mankind for liberty.”

Unfortunately, the producers did not take Keller’s perceptive critique of the weakest elements of the film seriously. The extant version of the film includes much of the footage that Keller and Macy found objectionable and actually opens with the scene in “The Council Chamber.” The following two “acts,” titled “Childhood,” in which Keller is played by a child actress, and “Maidenhood,” loosely follow Keller’s 1903 autobiography, The Story of My Life , and did meet with Macy and Keller’s approval. Some of the more fantastic scenes of Keller’s “Maidenhood,” including a daydream romance with Homer’s Odysseus , reveal the influence of Keller’s literary metaphors, as well as the influence of the sensorially rich descriptive literary style of her 1908 essay collection The World I Live In . Still, Keller and Macy were disappointed with the film.

Deliverance introduces a fictional character into Keller’s childhood in Tuscumbia, Alabama—a young immigrant girl named Nadja. Scenes from Nadja’s life, a fairly conventional silent-era story of poverty and hardship, are crosscut with scenes from Keller’s biography. The women reunite after Nadja’s son returns from war blinded and she seeks Keller’s aid. While the film includes no direct representations of Keller’s adult political work or speeches—“Act Three Womanhood” focuses instead on Keller’s sensory experiences and domestic arrangements—Nadja’s story carries an explicitly political, but conventionally patriotic, message.

In their correspondence with the filmmakers, Macy and Keller repeatedly insisted that they wanted the film to include scenes from the rehabilitation hospitals where blinded World War I veterans were learning to adjust physically and psychologically to their disabilities, work Keller was then advocating. These scenes would have been more in tune with Keller’s pacifist and socialist opposition to a war that, as she writes in “Strike Against War,” would take “the lives of millions of young men; other millions crippled and blinded for life; existence made hideous for still more millions of human beings” (79). One can’t help but contrast this statement of Keller’s antiwar sympathies with the images of the uplifting and heroic blinded soldier that appears beside the adult Keller in the film’s final scenes.

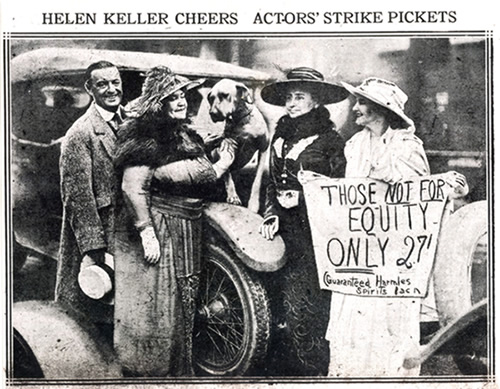

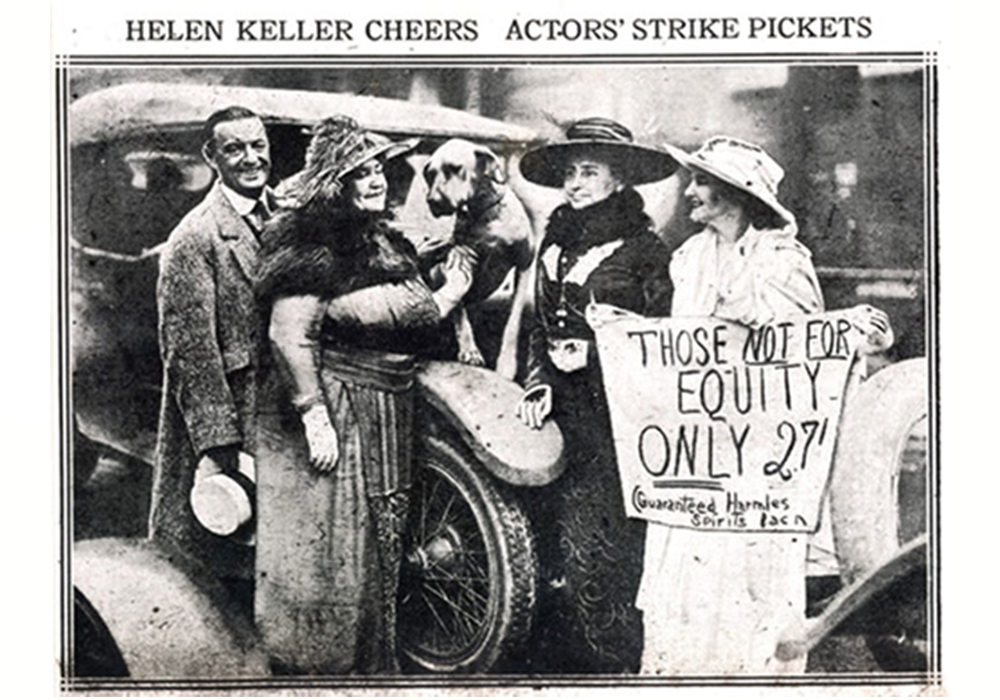

Keller had planned to speak at the August 1919 New York premiere of the film, but an actors and musicians strike was underway in the city and, according to the New York Times , “when she learned that the actors were striking against the Schuberts, who own the Lyric [the theatre premiering Keller’s film], she declined to come to the theatre” (1). The film was not successful at the box office, and distributor George Kleine eventually wrote to Keller that the film would be distributed for educational purposes and that he had removed the Nadja story to satisfy her.

Bibliography

Keller, Helen. Midstream: My Later Life. 1929. New York: Greenwood Press, 1969: 186-215.

------. Letter to Francis Trevelyan Miller, draft. April 10, 1918. American Foundation for the Blind.

------. Letter to Mrs. William Thaw. 12 April 1919. American Foundation for the Blind.

------. “Strike Against War.” In Helen Keller: Her Socialist Years. Writings and Speeches . Ed. Philip S. Foner. New York: International Publishers, 1967.

------. The Story of My Life . 1903; Rpt. Cutchogue, N.Y. : Buccaneer Books, 1976.

------. The World I Live In . New York: The Century Co., 1908.

Miller, Francis Trevelyan. Letter to Mr. Holmes. 5 June 1918. American Foundation for the Blind.

------. Letter to Richard Daly. 5 Jan 1918. American Foundation for the Blind.

“Miss Keller’s Own Work.” New York Times (24 Aug. 1919): 4.

“Stage Hands and Musicians Strike; 16 Theatres Dark.” New York Times (17 Aug. 1919):1.

Archival Paper Collections:

Helen Keller Archive. American Foundation for the Blind .

Filmography

A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles:

1. Helen Keller as Actress and Producer

Deliverance. Prod./dir. George C. Platt, sc.: Francis Trevelyan Miller (Helen Keller Film Corp. 1919) cas.: Helen Keller, Anne Sullivan, si, 16mm. Archive: Library of Congress .

D. Streamed Media:

Deliverance (1919) is streaming online via the Library of Congress

Salerno, Abigail. "Helen Keller." In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. <https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-nqhs-vs25>

Helen Keller

Undeterred by deafness and blindness, Helen Keller rose to become a major 20 th century humanitarian, educator and writer. She advocated for the blind and for women’s suffrage and co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union.

Born on June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Keller was the older of two daughters of Arthur H. Keller, a farmer, newspaper editor, and Confederate Army veteran, and his second wife Katherine Adams Keller, an educated woman from Memphis. Several months before Helen’s second birthday, a serious illness – possibly meningitis or scarlet fever – left her deaf and blind. She had no formal education until age seven, and since she could not speak, she developed a system for communicating with her family by feeling their facial expressions.

Recognizing her daughter’s intelligence, Keller’s mother sought help from experts including inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who had become involved with deaf children. Ultimately, she was referred to Anne Sullivan, a graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind, who became Keller’s lifelong teacher and mentor. Although Helen initially resisted her, Sullivan persevered. She used touch to teach Keller the alphabet and to make words by spelling them with her finger on Keller’s palm. Within a few weeks, Keller caught on. A year later, Sullivan brought Keller to the Perkins School in Boston, where she learned to read Braille and write with a specially made typewriter. Newspapers chronicled her progress. At fourteen, she went to New York for two years where she improved her speaking ability, and then returned to Massachusetts to attend the Cambridge School for Young Ladies. With Sullivan’s tutoring, Keller was admitted to Radcliffe College, graduating cum laude in 1904. Sullivan went with her, helping Keller with her studies. (Impressed by Keller, Mark Twain urged his wealthy friend Henry Rogers, financed her education.)

Even before she graduated, Keller published two books, The Story of My Life (1902) and Optimism (1903), which launched her career as a writer and lecturer. She authored a dozen books and articles in major magazines, advocating for prevention of blindness in children and for other causes.

Sullivan married Harvard instructor and social critic John Macy in 1905, and Keller lived with them. During that time, Keller’s political awareness heightened. She supported the suffrage movement, embraced socialism, advocated for the blind and became a pacifist during World War I. Keller’s life story was featured in the 1919 film, Deliverance . In 1920, she joined Jane Addams, Crystal Eastman and other social activists in founding the American Civil Liberties Union; four years later she became affiliated with the new American Foundation for the Blind in 1924.

After Sullivan’s death in 1936, Keller continued to lecture internationally with the support of other aides, and she became one of the world’s most-admired women (though her advocacy of socialism brought her some critics domestically). During World War II, she toured military hospitals bringing comfort to soldiers.

A second film on her life won the Academy Award in 1955; The Miracle Worker -- which centered on Sullivan -- won the 1960 Pulitzer Prize as a play and was made into a movie two years later. Lifelong activist, Keller met several U.S. presidents and was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. She also received honorary doctorates from Glasgow, Harvard, and Temple Universities.

Edited by Debra Michals, Ph.D.

- “Helen Keller.” Perkins. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- “Helen Keller.” American Foundation for the Blind. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- "Helen Adams Keller." Dictionary of American Biography . New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988. U.S. History in Context . Accessed February 4, 2015.

- "Keller, Helen." UXL Encyclopedia of U.S. History . Sonia Benson, Daniel E. Brannen, Jr., and Rebecca Valentine. Vol. 5. Detroit: UXL, 2009. 847-849. U.S. History in Context . Accessed February 4, 2015.

- Ozick, Cynthia. “What Helen Keller Saw.” The New Yorker. June 16, 2003. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- Weatherford, Doris. American Women's History: An A to Z of People, Organizations, Issues, and Events . New York: Prentice Hall, 1994.

- PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA - Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2015. Date accessed.

Chicago - Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller." National Women's History Museum. 2015. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/helen-keller.

Helen Keller: Described and Captioned Educational Media

Helen Keller Biography, American Foundation for the Blind

Helen Keller, Perkins School for the Blind

Helen Keller Birthplace

Helen Keller International

The Miracle Worker (1962). Dir. Arthur Penn. (DVD) Film.

The Miracle Worker (2000). Dir. Nadia Tass. (DVD) Film.

Keller, Helen. The World I Live In . New York: NYRB Classics, 2004.

Ford, Carin. Helen Keller: Lighting the Way for the Blind and Deaf . Enslow Publishers, 2001.

Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller: A Life . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Related Biographies

Abigail smith adams, jane addams, susan brownell anthony, josephine baker, related background, the extraordinary relevance of girl's schools, why are so many teachers women, woman's suffrage timeline, march on washington for jobs and freedom.

Helen Keller

- Occupation: Activist

- Born: June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama

- Died: June 1, 1968 in Arcan Ridge, Easton, Connecticut

- Best known for: Accomplishing much despite being both deaf and blind.

- Annie Sullivan was often called the "Miracle Worker" for the way she was able to help Helen.

- Helen became very famous. She met with every President of the United States from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon Johnson . That's a lot of presidents!

- Helen starred in a movie about herself called Deliverance . Critics liked the movie, but not a lot of people went to see it.

- She loved dogs. They were a great source of joy to her.

- Helen became friends with famous people such as the inventor of the telephone Alexander Graham Bell and the author Mark Twain .

- She wrote a book titled Teacher about Annie Sullivan's life.

- Two films about Helen Keller won Academy Awards. One was a documentary called The Unconquered (1954) and the other was a drama called The Miracle Worker (1962) starring Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke.

- Listen to a recorded reading of this page:

Back to Biography for Kids

- All Teaching Materials

- New Lessons

- Popular Lessons

- This Day In People’s History

- If We Knew Our History Series

- New from Rethinking Schools

- Workshops and Conferences

- Teach Reconstruction

- Teach Climate Justice

- Teaching for Black Lives

- Teach Truth

- Teaching Rosa Parks

- Abolish Columbus Day

- Project Highlights

Who Stole Helen Keller?

June 21, 2012

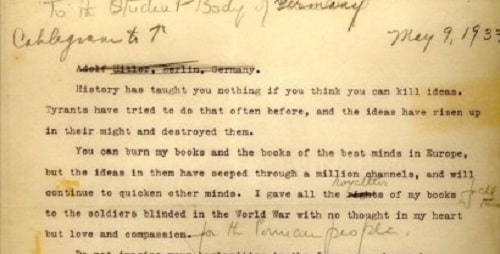

“When one comes to think of it, there are no such things as divine, immutable, or inalienable rights. Rights are things we get when we are strong enough to make good our claim on them.” Portrait by Robert Shetterly.

By Ruth Shagoury