- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: What is the Connection between Artworks and Emotions?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 169073

- Pierre Fasula

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

There are many connections between artworks and emotions, and this chapter aims at describing the ones that are philosophically significant. For this reason, it will focus on the Expression Theory of Art and its main alternatives.

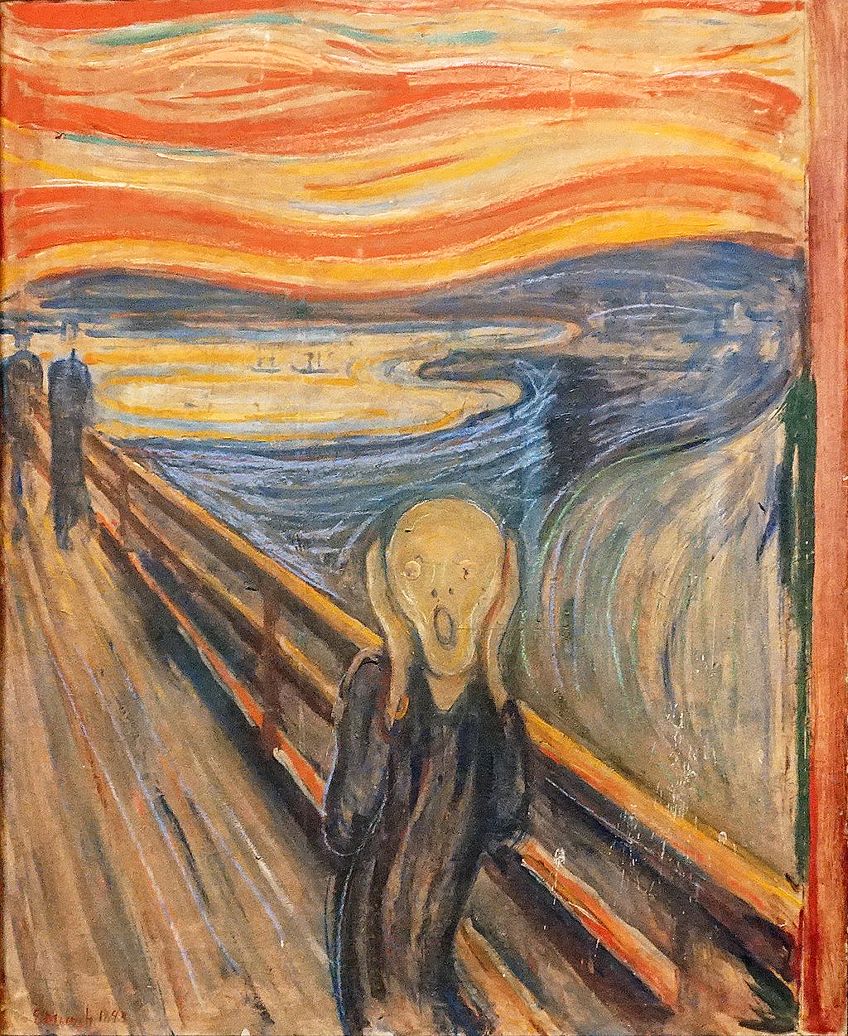

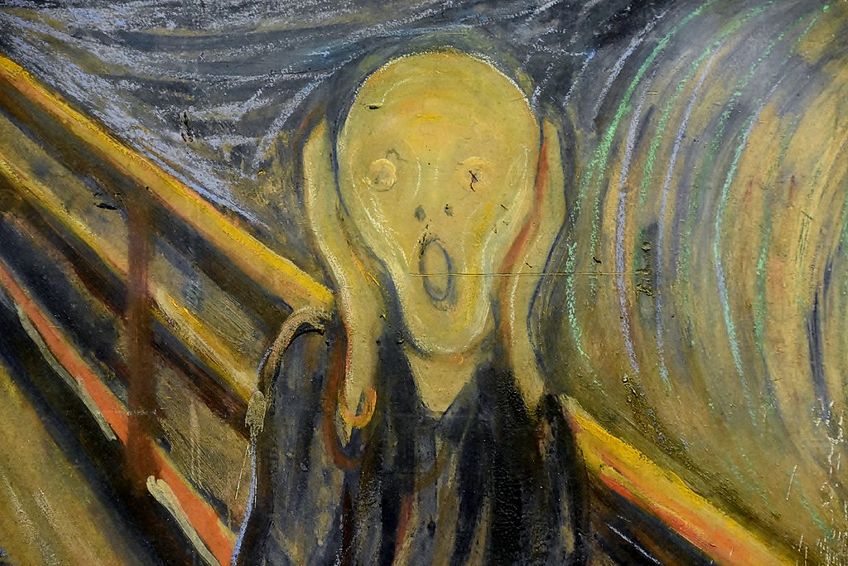

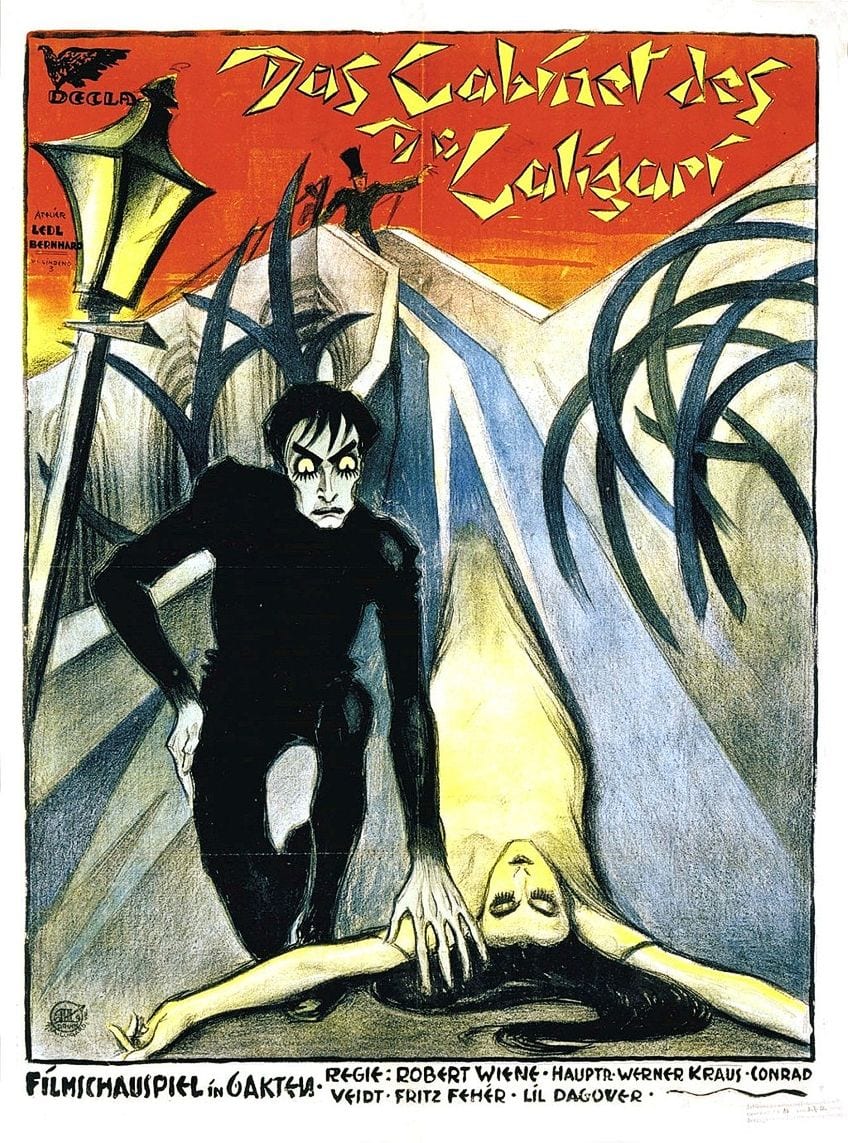

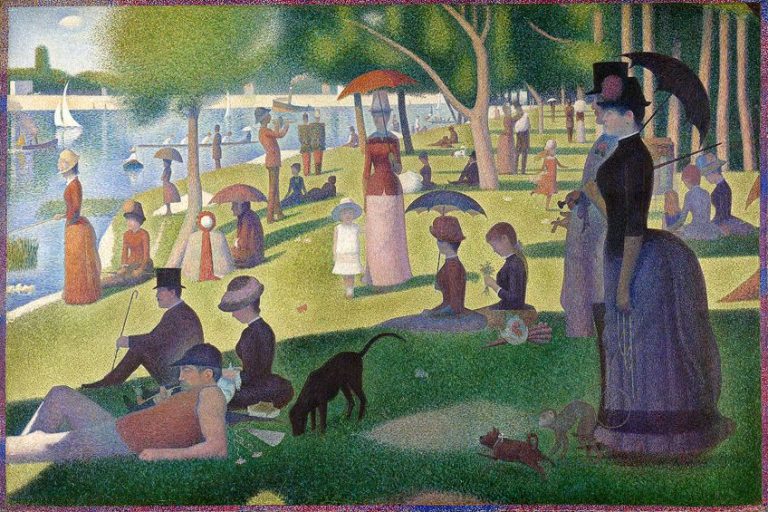

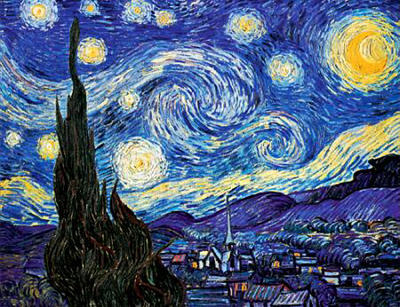

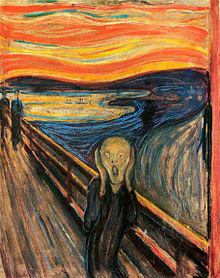

We can describe artworks as sad or cheerful for instance, and more generally as expressing emotions such as enthusiasm, admiration, and desperation. To take famous examples, Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream expresses anxiety; Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Infanta the sadness of mourning; George Miller’s movie Mad Max the rage in front of the loss of kinship. But how are we supposed to understand and explain this connection between artworks and emotions in terms of expression? And is expression the only relation between artworks and emotions? In this chapter, we will explore three main alternatives: the first section develops the idea that artworks express the artist’s emotions; the second that art elicits and represents emotions independently of the artist’s emotions; and the third that art can be said to express emotions by themselves.

Let’s present these alternatives more closely. The first one is generally termed the Expression Theory of Art: if artworks can be described with the vocabulary of emotions, as expressing emotions, it is because they express the artist’s emotions. An additional feature is that this expression of the artist enables the audience to experience these emotions. But it seems necessary to assess such a theory: is it legitimate to explain the sadness of a poem by saying that it actually expresses the sadness of its creator? The second theory involves no reference to the artist’s emotions. A more central relation lies between the artwork and the audience, as the former is made to elicit emotions in the latter or represent emotions for the latter. However, what is the difference between elicitation and representation? And what is the connection between representing and expressing emotions? The third alternative defends precisely the idea that artworks can be said to express emotions themselves, without being necessarily connected to the artist’s emotions or those of the audience.

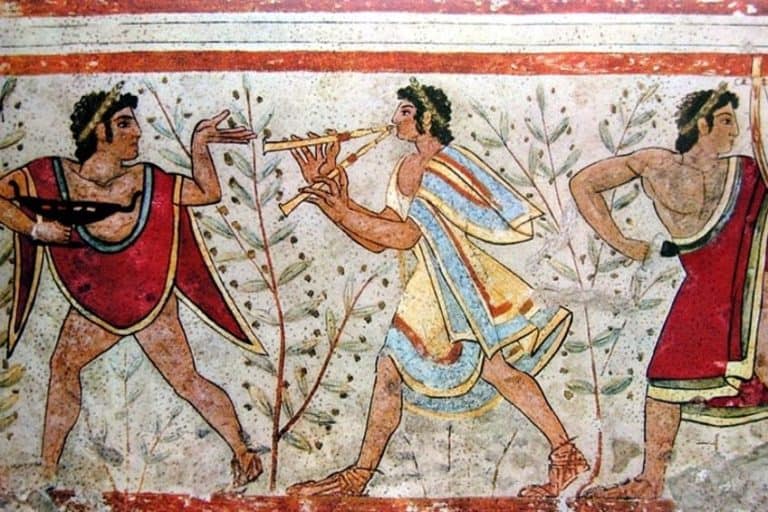

A historical remark must first be made in order to bring out the specificity of this issue. That artworks express the artist’s emotions is an idea that appears with romanticism, at the beginning of the 19 th century. [1] Before this period, another conception of artworks is predominant: they were considered as representations of reality. [2] This concept of representation can be understood in many ways and raises issues, but the most important for this chapter is that this concept of representation was more or less supplanted by the concept of expression, as can be seen for instance in the famous claim of the English romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850) in his preface to Lyrical Ballads : “all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” (Wordsworth and Coleridge [1800] 1991, 237). Even if, according to Wordsworth, “our continued influxes of feeling are modified and directed by our thoughts” (237) and his aim was to describe and colour ordinary life, the expression of emotions became central, a criterion not only for judging but also defining poetry, and later any kind of art.

The Expression Theory of Art

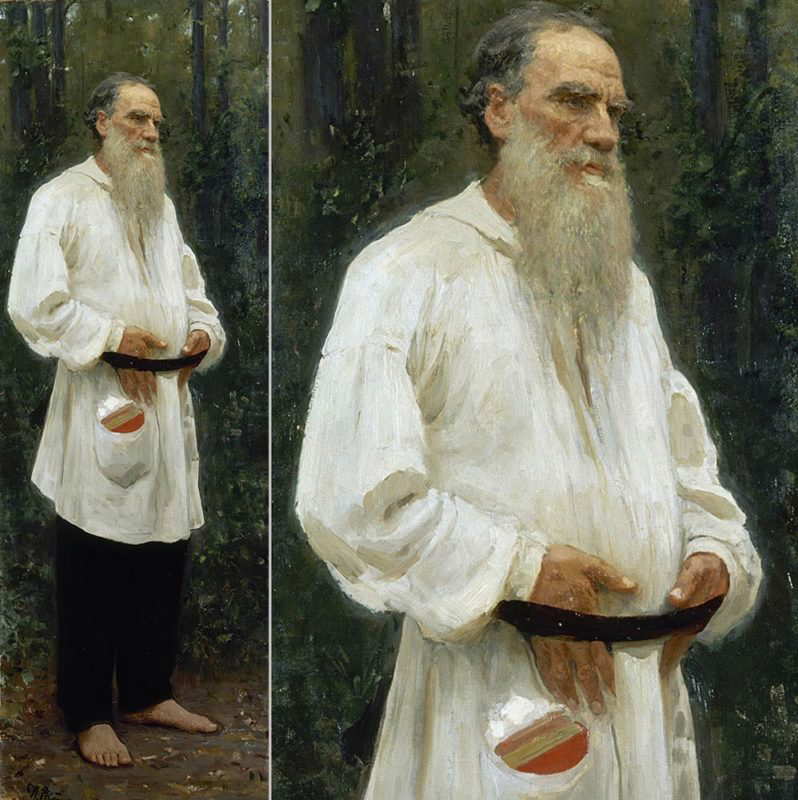

In this section, we will begin with a description of the Expression Theory of Art, following the path of two famous defenders of it: Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) in What is Art? and R.G. Collingwood (1889–1943) in The Principles of Art. Then we’ll consider several criticisms that can be addressed to this theory.

Suppose you find and describe such or such poem as expressing anger; it is rather natural to try to explain it by saying that the poem expresses the artist’s anger. More precisely, the mention of the artist’s anger functions here both as a justification of our description, and as an explanation of the poem itself, in the sense that the poet is supposed to have experienced such a feeling and produced the poem according to his feeling. However, it is possible to refine this ordinary explanation using literary and philosophical resources.

Tolstoy presents the Expression Theory of Art in the 5 th chapter of What Is Art? Its first four chapters are devoted to beauty, insofar as beauty is very often considered as a criterion to distinguish between art and non-art. Tolstoy criticises such a use of the idea of beauty in order to propose another measure: the expression of emotions. The idea of beauty is particularly contentious, and as such it can’t provide a definition of art. This is why Tolstoy considers another option, shifting art into a more general framework: “the conditions of human life” (Tolstoy 1904, 47). Art is supposed to be one of these conditions of human life, or more precisely, “one of the means of intercourse between man and man” (47). Tolstoy then defines art in this way:

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and having evoked it in oneself, then, by means of movements, lines, colours, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others may experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art. Art is a human activity, consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings, and also experience them. (Tolstoy 1904, 50)

This definition implies, firstly, the presence of an artist, an audience, and an emotion; secondly, that the transfer of emotion from the artist to the audience is intentional (“consciously”); thirdly, that this requires an inward evocation and a clarification of what is experienced; fourthly, that the expression is based on specific artistic media (movements, lines, colours, sounds, words).

Thus Tolstoy puts together the elements of a dynamic model of art, emphasizing agents, action, and the means entailed in the experience and practice of art. Such a model is for Tolstoy more appropriate than the criterion of beauty insofar as it grasps the nature of art via its practice.

Collingwood similarly highlights these aspects of art, using the concept of expression to define art in his own version of the Expression Theory. However, his relevance and added value in comparison with Tolstoy lies in the distinction he draws between bringing out emotions and artistic expression:

When a man is said to express emotion, what is being said about him comes to this. At first, he is conscious of having an emotion, but not conscious of what this emotion is. All he is conscious of is a perturbation or excitement which he feels going on within him, but of whose nature he is ignorant. While in this state, all he can say about his emotion is: “I feel … I don’t know what I feel.” From this helpless and oppressed condition he extricates himself by doing something which we call expressing himself. This is an activity which has something to do with the thing we call language: he expresses himself by speaking. It has also something to do with consciousness: the emotion expressed is an emotion of whose nature the person who feels it is no longer unconscious. It also has something to do with the way in which he feels the emotion. As unexpressed, he feels it in what we called a helpless and oppressed way; as expressed, he feels in a way from which this sense of oppression has vanished. His mind is somehow lightened and eased. (Collingwood 1960, 109–10)

At the beginning of the process of creation, there isn’t an identified “ready-made” emotion waiting for its expression, but what Collingwood calls a perturbation, an excitement; that is to say, an internal feeling, the nature and the cause of which are still undetermined. An activity, the expression of oneself (the paradigm of which is language) clarifies, makes the perturbation conscious, and transforms it into an emotion, while alleviating the individual’s perturbation. Thus, Collingwood considers the expression of the emotions in a deeper and a more subtle way, describing more precisely its actions and effects in individuals, but leaving aside other dimensions taken into account by Tolstoy, such as the necessity of an audience and the means of artistic expression. This provides the starting point of the next section.

The audience, the identity, and the existence of emotions in artistic creation

The expression theory of art by both Tolstoy and Collingwood are questionable, and we’ll raise objections corresponding to their main elements.

The first objection deals with the necessity of an audience to which to communicate the emotions. An interesting feature of Collingwood’s (1960) version of this theory is that “the expression of an emotion by speech may be addressed to someone; but if so it is not done with the intention of arousing a like emotion in him” (110, italics mine). This introduces a difference with Tolstoy’s version. According to the latter, art consists, as an activity, in passing on emotions to other people; whereas, according to the former, the relation of art to an audience is only a possibility, not a necessity. The consequence is that there are actually two versions of Expression Theory of art, named by Noël Carroll in Philosophy of Art respectively the “transmission theory” and the “solo theory” (Carroll 1999, 65).

What is the issue? The objection to the transmission theory is that “one can make a work of art for oneself” without trying to publish it (e.g., literature) or to exhibit it (e.g., painting, sculpture) (Carroll 1999, 67). Someone else who would read or see it would deem it as an artwork, but if the artist hides it, the work is still an artwork. The rejoinder is that the mere fact of writing a poem, or producing a painting, or creating a piece of music, is a use of public media that makes the emotions public, which “indicate[s] an intention to communicate to others” (67).

A solution can be developed from two similar remarks. Firstly, there is a distinction between an actual and a potential audience. An artist may not want to address such or such audience, but create an artwork designed to communicate to a potential audience. Secondly, one can question the intention to communicate to others, without questioning the communication itself. Even if it is not the intention of an artist to communicate emotions to others, an artwork can nevertheless communicate emotions. These two remarks converge in the idea that communication is a potentiality, not necessarily an intention nor even a fact. This potentiality is actualised if the artwork is presented to a public. This idea preserves both the idea that one can make a work of art for oneself, and that the medium used is publicly accessible.

There is a second objection one can make against the transmission version. It deals with the identity of the emotion supposed to be communicated from the artist to the audience. “Identity” means firstly that the audience experiences the same emotion as the artist, which implies that the artist experienced this emotion and transmits it. But is this necessarily the case? A poet can express a feeling of sorrow, but the audience feels admiration for this expression. Let’s take for instance Victor Hugo’s poem “Tomorrow, At Dawn” (1856), related to the death of his daughter:

At dawn tomorrow, when the plains grow bright, I’ll go. You wait for me: I know you do. I’ll cross the woods, I’ll cross the mountain-height. No longer can I keep away from you. I’ll walk along with eyes fixed on my mind— The world around I’ll neither hear nor see— Alone, unknown, hands crossed, and back inclined; And day and night will be alike to me. I’ll see neither the gold of evening gloom Nor the sails off to Harfleur far away; And when I come, I’ll place upon your tomb Some flowering heather and a holly spray. (Hugo 2004, 199)

The emotion expressed and the emotion experienced may not be the same: Hugo expresses sadness, annihilation, and isolation, whereas the audience may well feel sadness, but also compassion, and perhaps more generally admiration, in response to such an expression of love.

“Identity” also refers to the identification of the emotions. Is the audience supposed to experience “these” emotions, as if it were possible to clearly identify our emotions? One can highlight the generality and vagueness of certain emotions. They are not necessarily individualised, but general, shared, and they are not necessarily clearly defined, but vague. In the example above, emotions overlap, and some of them are explicitly mentioned, others only suggested. It is true that this could be precisely the function of artworks to individualise and define our emotions. But such an idea fits only with a part of artistic practice: e.g., poetry is only sometimes an evocation of entangled emotions.

Ultimately, the Expression Theory of Art assumes the artist’s experience of emotions. However it is not at all certain that she must experience this emotion herself. Does a writer of a thriller experience fear, so that the thriller expresses and produces fear in the audience? It is likely they experience excitement in trying to produce fear. This objection does not deal anymore with the identity of the emotion, but with its very existence, at the roots of the potential relation between the artist and the audience. Why should an artist even experience any emotion? Of course, it would be difficult to defend the idea of artists experiencing no emotion at all. But it does not mean that emotions are the cause, the reason, or the object of creation. In this sense, emotions are not always necessary to creation.

Eliciting and Representing Emotions

These criticisms do not imply the rejection of expression of/and emotions in art, but only of the idea that art must be defined as an expression of the artist’s emotions to an audience by certain means. Moreover, such a criticism allows other possible descriptions of the relation between artworks and emotions, such as elicitation and representation, which we consider in this section.

It is a classical idea of the rhetorical approach to literary works that they elicit emotions. Rhetoric describes the techniques by which one is able to produce reactions in an audience according to context. In the judicial field, the lawyer has to convince judges regarding past facts in order to win the case. In the political field, politicians and ordinary citizens have to convince each other to make a decision about the future, according to what is useful or detrimental to the country. In the field of public eulogies, the speaker has to praise or comfort. In all these cases, the rhetoric provides non-linguistic means such as advice about posture, gestures, etc., and linguistic means such as patterns of arguments (for instance, enthymemes) and figures of speech, that both play on and elicit emotional reactions, in order to convince and persuade.

Beyond these specific fields, literary criticism and more generally aesthetics use (among other things) the figures of speech studied and systematised by rhetoric. They do so in order not only to describe literary artworks and the style of artworks, but also to show the way artists and literary writers use these figures of speech as means to elicit emotions. Let’s consider the first stanza of Rimbaud’s “Orphans’ New Year Gifts” (1870):

The room is full of shadow and the sad Faint whispering of two little ones, Heads still heavy with dreams Beneath the long white curtain, stirring slightly … Outside, birds cluster for warmth, Wings drooping against the grey sky. And the New Year, dragging mist, Trailing its snow-dress on the ground, Smiles through tears, and shivers a song … (Rimbaud 2001, 3)

A significant feature is its general structure, organised around the contrast of two locations, a room and the outside, but also the continuity established between them by the echo of the shadow of the room in the sad whispering of the orphans, on one hand, and the mist of the New year and its “smile through tears,” on the other. But more important is the personification of the New Year, which drags mist, trails a snow-dress, smiles through tears, and shivers a song, as a presence outside that echoes the orphans’ sadness within. This figure of speech contributes to the eliciting of visual and emotional impressions, as a picture materialises gradually and a feeling of sadness arises, one that then envelops the whole stanza.

An alternative way to describe this elicitation of emotions can be found in T.S. Eliot’s essay on “Hamlet and His Problems,” under the label of “objective correlative.” There he tries to explain what is, according to him, Hamlet ’s failure. A starting point is his agreement with the idea that “the essential emotion of the play is the feeling of a son [Hamlet] towards a guilty mother” (Eliot 1939, 144). If there is a failure, though, it lies in that “Hamlet is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible, . . . that Hamlet’s bafflement at the absence of objective equivalent to his feelings is a prolongation of the bafflement of his creator in the face of his artistic problem” (145). By contrast, here is the rule T.S. Eliot defends:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an “objective correlative”; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked. (Eliot 1939, 145)

The emotion of the play and, more generally, of a literary work is to be found in an objective correlative, which is an “exact equivalent” characterised by a “complete adequacy of the external to the emotion.” That’s to say, more concretely, the emotion is found in a description of situations, events, characters, reactions, that shows this emotion, and therefore in a full representation of the emotion that elicits it in the audience. According to T.S. Eliot one finds a good example of objective correlative in Macbeth :

You will find that the state of mind of Lady Macbeth walking in her sleep has been communicated to you by a skilful accumulation of imagined sensory impressions; the words of Macbeth on hearing of his wife’s death strike us as if, given the sequence of events, these words were automatically released by the last events in the series. (Eliot 1939, 145)

Nevertheless, it would be superficial to present the elicitation of emotions as a causal production of emotion by means of figures of speech. As Danto puts it in his discussion of Aristotle and rhetoric in the last part of The Transfiguration of the Common place ,

if it be anger they [rhetoricians] intend to arouse, they will know how to characterize the intended object of the anger in such a way that anger toward that object is the only justifiable response. . . . After all, like beliefs and actions–in contrast with bare perceptions and mere bodily movements–emotions–in contrast perhaps with bare feelings–are embedded in structures of justification. There are things we know we ought to feel given a certain characterization of the conditions we are under. (Danto 1981, 169)

To elicit emotions for a (literary) artwork is not merely a matter of causal relation: the artwork, its figures of speech, or its style, if successful, are such that one should have a determinate emotional response. In other words, not any emotion is admissible but only some of them are justifiable in front of a particular artwork.

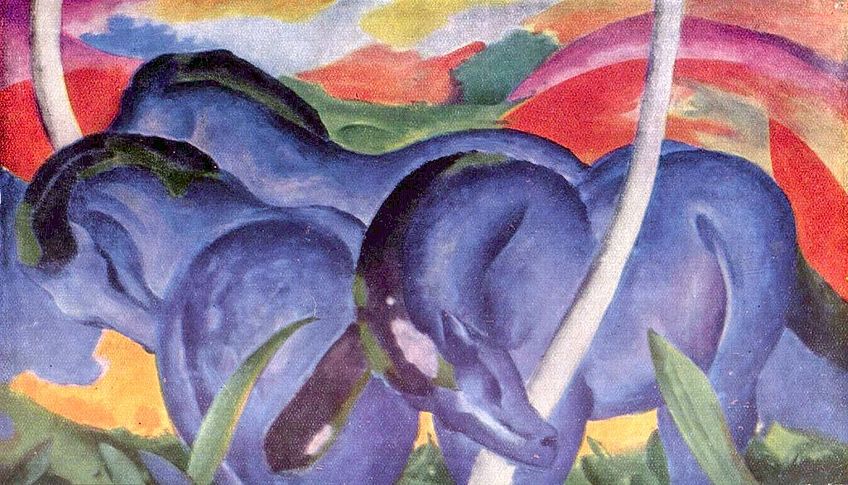

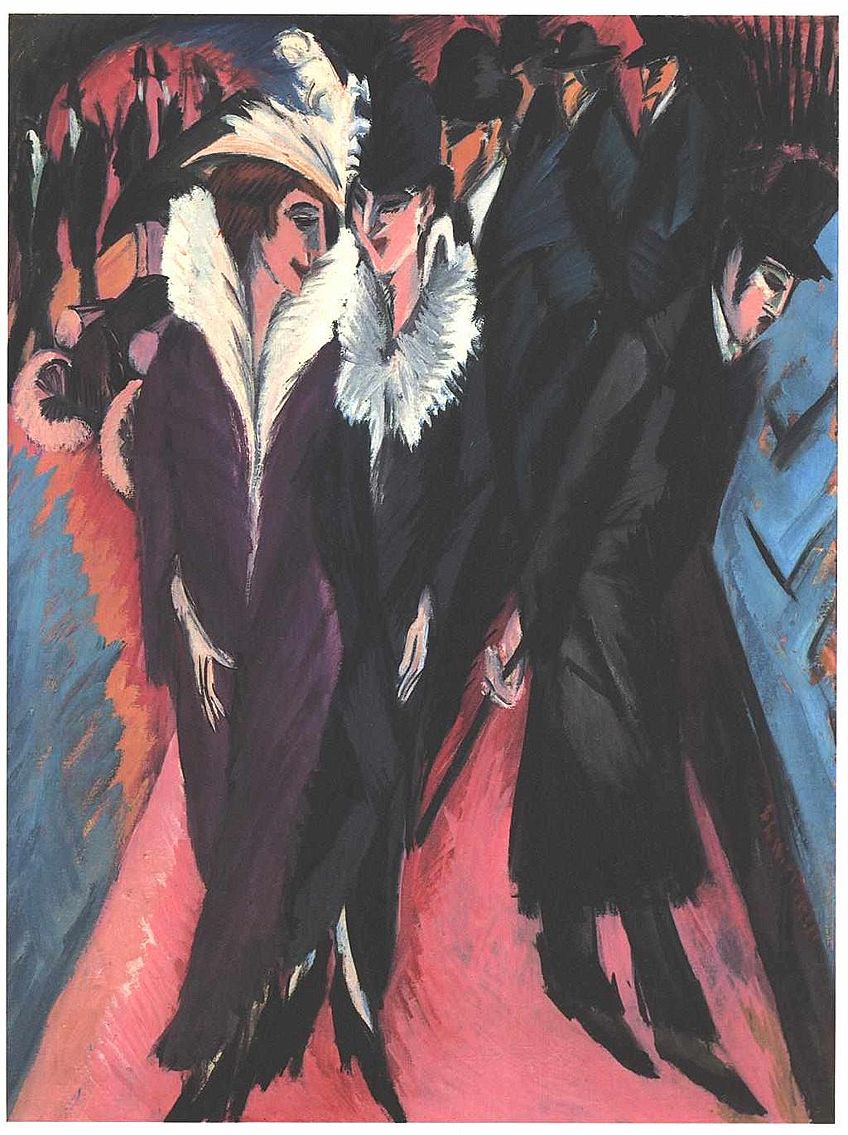

To conclude this section, it is possible to argue that, even though artworks do not necessarily express the artist’s emotions, they elicit emotions in the audience by artistic means such as figures of speech in literary artworks, or representation of emotions in the choice of a certain “correlated” objectivity, such as a series of actions in a play or a set of forms and colours in a painting.

An Autonomous Expression

The idea defended in the last section, according to which artworks can represent emotions, allows us to come back to the notion of expression, but in a different way to the Expression Theory of Art elaborated in the first section. T.S. Eliot uses “representation” and “expression” almost indistinguishably, but these terms should be refined. What does it mean for artworks not only to represent but also to express emotions by themselves? A closer analysis of the notion of expression is needed here.

In our ordinary judgments, we talk about the sadness of a poem, the fact that a certain piece of music is described as joyful and another one as desperate, or that a particular style for a building is cold. Hence, the question: Can artworks be said to express emotions themselves? And why would it be a problem? As Oets K. Bouwsma explains in “The Expression Theory of Art,”

The use of emotional terms—sad, gay, joyous, calm, restless, hopeful, playful, etc.—in describing music, poems, pictures, etc., is indeed common. So long as such descriptions are accepted and understood in innocence, there will be, of course, no puzzle. But nearly everyone can understand the motives of [the] question “How can music be sad?” and of his impulsive “It can’t, of course.” (Bouswma 1959, 74)

How can we explain such a paradoxical use of emotional terms, which seems to be at the same time accepted and impossible? What is assumed in “Music can’t be sad” is “… as someone can be sad.” It is the reason why, according to Bouswma, it is interesting to consider and compare several uses of “sad,” such as: “Cassie is sad,” “Cassie’s dog is sad,” “Cassie’s book is sad,” and “Cassie’s face is sad.” In the first case, one can imagine Cassie learning the death of a next of kin and crying, or reading a wonderful but sad poem, and becoming sad herself, crying or not. In the second case, it makes sense to say that the dog can be sad, but could it cry? One does not expect the dog to express sadness in all the ways human beings do (a dog does not restrain its howls). One can paraphrase the third case saying that this book makes Cassie sad. And in the last case, one can easily describe obvious signs of sadness, however there is no guarantee that she is really sad.

What conclusion can we draw now as regards to the assertion “the music is sad”? This assertion is similar neither to Cassie being sad and crying because of a death in her family, nor to Cassie being sad but not crying, nor to her dog being sad but not crying: a song is neither crying nor holding back tears! It is much more similar to “the book is sad,” understood as producing sadness, but particularly as being sad in itself, as a face can be sad, be it a real face or a drawing: the book, the music, and the face express sadness themselves but in a specific way.

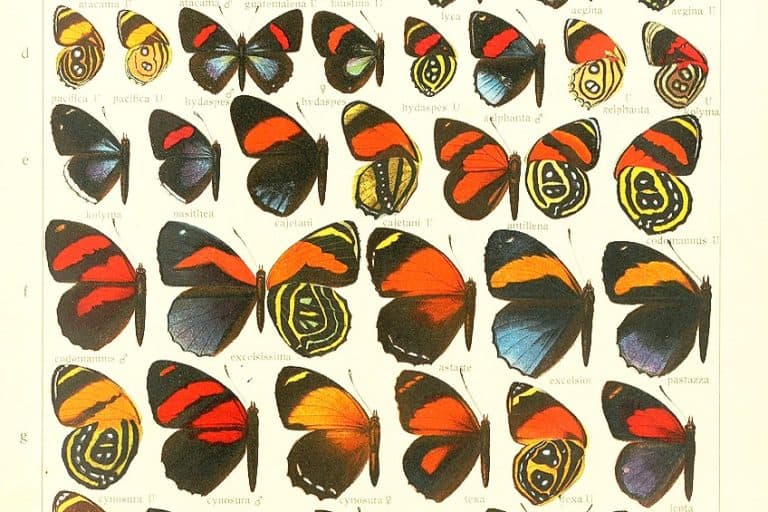

How can one account for this expression? Are these examples really on the same level? One can find an answer in Nelson Goodman’s theory of expression in Languages of Art , which is based on the concepts of exemplification and metaphor.

An expression can be considered as a kind of exemplification. Exemplification refers to a certain relation of something to some properties. For instance, a sample of fabric exemplifies cashmere, in that (1) it is made of cashmere and therefore possesses this property to be made of cashmere, (2) qua sample, it refers to this property. Indeed, something can refer to cashmere without possessing this property of being made of cashmere, as it is the case in a description of this fabric.

However, such a definition of exemplification is not enough to account for the description of an artwork as expressing such or such emotion. It is true that a sad poem possesses this property of being sad, and refers to sadness in general, but how could a sad poem be “made of sadness” or be described literally as sad? The poem is not described literally as sad but metaphorically; the possession of the property is not literal but metaphorical. [3] Therefore, a poem exemplifies sadness in that (1) it refers to sadness and (2) possesses sadness (3) metaphorically.

One could object that this idea of metaphorical possession is obscure, as if only literal possession were without difficulty (for instance, in “this stone is hard”). However, among the different ways of describing things, events, people, etc., it is possible to attribute properties in a metaphorical way (and then to see in this possession an exemplification of the property in question). One could reply that, because it is a metaphor, the sadness is not “really” in the poem. However, the fact is that such a metaphorical description is sometimes far more objectively true than a literal one. To describe someone as a “Don Quixote” or a “Don Giovanni” (which means that this person possesses metaphorically and exemplifies the properties of Don Quixote or Don Giovanni) does not necessarily raise a question, whereas to describe literally such or such entity as a virus or an organism raises sometimes real difficulties and disagreements between scientists. In this sense, that a song or a poem expresses such or such emotion can be perfectly objective.

To conclude, there is certainly something right in the ordinary claim that artworks express emotions. This means that the issue lies somewhere else, in the philosophical accounts of such a claim. While a number of accounts can be found in contemporary philosophy, not all of them are likely to make sense of the ordinary claim about artwork’s expression of emotions.

More precisely, all the elements mentioned by Tolstoy are interesting for those who are passionate about arts: the relation of an artist and audience, the sharing of emotions, and the means used to do this. They all belong to our experience and practice of art, and one virtue of Tolstoy’s analysis is precisely to consider artworks in this broader context: our practices and experiences. At the same time, it raises a philosophical issue about what is essential in this general description if one wants to understand artworks’ specific feature regarding emotions: expressivity.

This chapter aims at showing the intrinsic expressivity of artworks, in addition to their capacity to elicit and represent emotions, ultimately leaving aside the artist’s and audience’s experience of emotions. The idea is neither to deny the reality of such an experience, nor its importance for the artist and the audience, but to highlight how artworks’ expressivity can be found in themselves, because they are themselves describable as expressing such or such emotion. To go further in this direction, one could say that the key to expressivity can be found in the functioning of works of art, for instance, the way a painting describes a landscape, possesses such or such characteristics (colours or lines), and refers to sadness or joy. What it is (characteristics) and what it does (description and reference) are central to understand how an artwork finally expresses emotions. The next step would be to come back to our experience and practice: How do they shape our ability to grasp the emotions expressed in artworks? What is the role of experience and practice in the understanding of the artwork’s expressivity?

Bouswma, Oets K. 1959. “The Expression Theory of Art.” In Aesthetics and Language , edited by William Elton, 73–99. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carroll, Noël. 1999. Philosophy of Art . London and New York: Routledge.

Collingwood, Robin G. 1960. The Principles of Art . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Danto, Arthur. 1981. The Transfiguration of the Commplace . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 1939. Selected Essays . London: Faber and Faber Limited.

Hugo, Victor. 2004. Selected Poems of Victor Hugo . Translated by E. H. and A. M. Blackmore. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Goodman, Nelson. 1968. Languages of Art . Indianapolis: The Bobs-Merrill Company.

Rimbaud, Arthur. 2001. Collected Poems . Edited by Martin Sorrell. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tolstoy, Leo. 1904. What is Art? Translated by Aylmer Maude. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Wordsworth, William and Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. [1800] 1991. Lyrical Ballads . Edited by R. L. Brett and A. R. Jones. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Particularly in Great Britain with William Wordsworth’s poetry, for instance his Lyrical Ballads (1798), or in Germany with Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, for instance “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” (1818). ↵

- The main representative works of this tradition are Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Poetics , even if the overlapping of their concept of imitation and the concept of representation is problematic. The question is indeed: Do artworks have to imitate reality? If so, what does "imitate" mean here? And what is the reality that would have to be imitated? ↵

- Goodman (1968) draws a distinction between literal and metaphorical descriptions as follows. A description is literal when the words are used in their ordinary, routine way (e.g., to use “green” to describe the grass). But it becomes metaphorical when the words are applied to new things that first of all resist such a description and then accept it (e.g., to use a word of colour in order to describe a mood). ↵

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Abstract expressionism.

Number 28, 1950

Jackson Pollock

The Glazier

Willem de Kooning

No. 13 (White, Red on Yellow)

Mark Rothko

The Flesh Eaters

William Baziotes

Black Reflections

Franz Kline

Clyfford Still

Symphony No. 1, The Transcendental

Richard Pousette-Dart

David Smith

Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70

Robert Motherwell

Black Untitled

Barnett Newman

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)

Night Creatures

Lee Krasner

Stella Paul Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

A new vanguard emerged in the early 1940s, primarily in New York, where a small group of loosely affiliated artists created a stylistically diverse body of work that introduced radical new directions in art—and shifted the art world’s focus. Never a formal association, the artists known as “Abstract Expressionists” or “The New York School” did, however, share some common assumptions. Among others, artists such as Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), Franz Kline (1910–1962), Lee Krasner (1908–1984), Robert Motherwell (1915–1991), William Baziotes (1912–1963), Mark Rothko (1903–1970), Barnett Newman (1905–1970), Adolph Gottlieb (1903–1974), Richard Pousette-Dart (1916–1992), and Clyfford Still (1904–1980) advanced audacious formal inventions in a search for significant content. Breaking away from accepted conventions in both technique and subject matter, the artists made monumentally scaled works that stood as reflections of their individual psyches—and in doing so, attempted to tap into universal inner sources. These artists valued spontaneity and improvisation, and they accorded the highest importance to process. Their work resists stylistic categorization, but it can be clustered around two basic inclinations: an emphasis on dynamic, energetic gesture, in contrast to a reflective, cerebral focus on more open fields of color. In either case, the imagery was primarily abstract. Even when depicting images based on visual realities, the Abstract Expressionists favored a highly abstracted mode.

Context Abstract Expressionism developed in the context of diverse, overlapping sources and inspirations. Many of the young artists had made their start in the 1930s. The Great Depression yielded two popular art movements, Regionalism and Social Realism, neither of which satisfied this group of artists’ desire to find a content rich with meaning and redolent of social responsibility, yet free of provincialism and explicit politics. The Great Depression also spurred the development of government relief programs, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a jobs program for unemployed Americans in which many of the group participated, and which allowed so many artists to establish a career path.

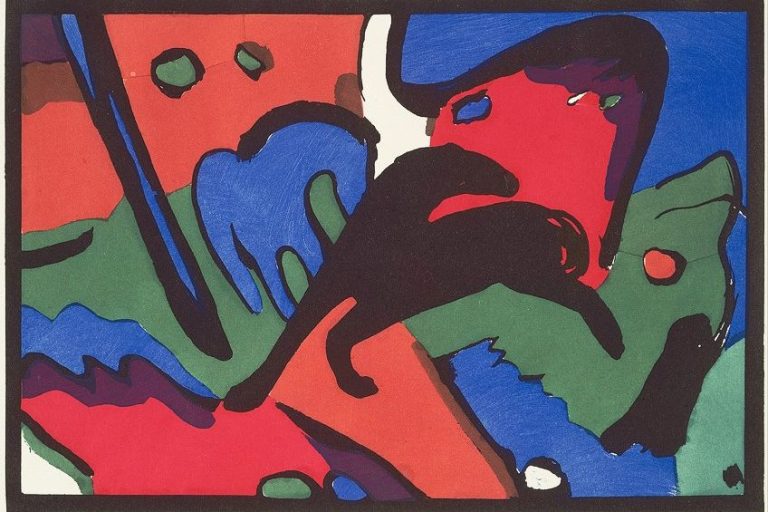

But it was the exposure to and assimilation of European modernism that set the stage for the most advanced American art. There were several venues in New York for seeing avant-garde art from Europe. The Museum of Modern Art had opened in 1929, and there artists saw a rapidly growing collection acquired by director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. They were also exposed to groundbreaking temporary exhibitions of new work, including Cubism and Abstract Art (1936), Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (1936–37), and retrospectives of Matisse , Léger , and Picasso , among others. Another forum for viewing the most advanced art was Albert Gallatin’s Museum of Living Art, which was housed at New York University from 1927 to 1943. There the Abstract Expressionists saw the work of Mondrian, Gabo, El Lissitzky, and others. The forerunner of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum—the Museum of Non-Objective Painting—opened in 1939. Even prior to that date, its collection of Kandinskys had been publicly exhibited several times. The lessons of European modernism were also disseminated through teaching. The German expatriate Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) became the most influential teacher of modern art in the United States, and his impact reached both artists and critics.

The crisis of war and its aftermath are key to understanding the concerns of the Abstract Expressionists. These young artists, troubled by man’s dark side and anxiously aware of human irrationality and vulnerability, wanted to express their concerns in a new art of meaning and substance. Direct contact with European artists increased as a result of World War II, which caused so many—including Dalí, Ernst, Masson, Breton, Mondrian, and Léger—to seek refuge in the U.S. The Surrealists opened up new possibilities with their emphasis on tapping the unconscious. One Surrealist device for breaking free of the conscious mind was psychic automatism—in which automatic gesture and improvisation gain free rein.

Early Work Early on, the Abstract Expressionists, in seeking a timeless and powerful subject matter, turned to primitive myth and archaic art for inspiration. Rothko, Pollock, Motherwell, Gottlieb, Newman, and Baziotes all looked to ancient or primitive cultures for expression. Their early works feature pictographic and biomorphic elements transformed into personal code. Jungian psychology was compelling, too, in its assertion of the collective unconscious. Directness of expression was paramount, best achieved through lack of premeditation. In a famous letter to the New York Times (June 1943), Gottlieb and Rothko, with the assistance of Newman, wrote: “To us, art is an adventure into an unknown world of the imagination which is fancy-free and violently opposed to common sense. There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is critical.”

Mature Abstract Expressionism: Gesture In 1947, Pollock developed a radical new technique, pouring and dripping thinned paint onto raw canvas laid on the ground (instead of traditional methods of painting in which pigment is applied by brush to primed, stretched canvas positioned on an easel). The paintings were entirely nonobjective. In their subject matter (or seeming lack of one), scale (huge), and technique (no brush, no stretcher bars, no easel), the works were shocking to many viewers. De Kooning, too, was developing his own version of a highly charged, gestural style, alternating between abstract work and powerful iconic figurative images. Other colleagues, including Krasner and Kline, were equally engaged in creating an art of dynamic gesture in which every inch of a picture is fully charged. For Abstract Expressionists, the authenticity or value of a work lay in its directness and immediacy of expression. A painting is meant to be a revelation of the artist’s authentic identity. The gesture, the artist’s “signature,” is evidence of the actual process of the work’s creation. It is in reference to this aspect of the work that critic Harold Rosenberg coined the term “action painting” in 1952: “At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act—rather than as a space in which to reproduce, re-design, analyze, or ‘express’ an object, actual or imagined. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.”

Mature Abstract Expressionism: Color Field Another path lay in the expressive potential of color. Rothko, Newman, and Still, for instance, created art based on simplified, large-format, color-dominated fields. The impulse was, in general, reflective and cerebral, with pictorial means simplified in order to create a kind of elemental impact. Rothko and Newman, among others, spoke of a goal to achieve the “sublime” rather than the “beautiful,” harkening back to Edmund Burke in a drive for the grand, heroic vision in opposition to a calming or comforting effect. Newman described his reductivism as one means of “freeing ourselves of the obsolete props of an outmoded and antiquated legend … freeing ourselves from the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, and myth that have been the devices of Western European painting.” For Rothko, his glowing, soft-edged rectangles of luminescent color should provoke in viewers a quasi-religious experience, even eliciting tears. As with Pollock and the others, scale contributed to the meaning. For the time, the works were vast in scale. And they were meant to be seen in relatively close environments, so that the viewer was virtually enveloped by the experience of confronting the work. Rothko said, “I paint big to be intimate.” The notion is toward the personal (authentic expression of the individual) rather than the grandiose.

The Aftermath The first generation of Abstract Expressionism flourished between 1943 and the mid-1950s. The movement effectively shifted the art world’s focus from Europe (specifically Paris) to New York in the postwar years. The paintings were seen widely in traveling exhibitions and through publications. In the wake of Abstract Expressionism, new generations of artists—both American and European—were profoundly marked by the breakthroughs made by the first generation, and went on to create their own important expressions based on, but not imitative of, those who forged the way.

Paul, Stella. “Abstract Expressionism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/abex/hd_abex.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Messinger, Lisa Mintz Abstract Expressionism: Works on Paper. Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992. See on MetPublications

Thaw, Eugene Victor "The Abstract Expressionist." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin , v. 44, no. 3 (Winter, 1986–87). See on MetPublications

Tinterow, Gary, Lisa Mintz Messinger, and Nan Rosenthal, eds. Abstract Expressionism and Other Modern Works: The Muriel Kallis Steinberg Newman Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007. See on MetPublications

Additional Essays by Stella Paul

- Paul, Stella. “ Modern Storytellers: Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Fernand Léger (1881–1955)

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

- School of Paris

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986)

- Jasper Johns (born 1930)

- Modern Storytellers: Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold

- Paul Klee (1879–1940)

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- 20th Century A.D.

- Abstract Art

- Action Painting / Gestural Painting

- Beat Movement

- Color Field

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- North America

- Nouveau Realisme

- Oil on Canvas

- Regionalism

- Sculpture in the Round

- Stainless Steel

- Tachism / Art Informel / Lyrical Abstraction

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Albers, Josef

- Baziotes, William

- Booth, Peter

- De Kooning, Willem

- Gorky, Arshile

- Kline, Franz

- Krasner, Lee

- Motherwell, Robert

- Newman, Barnett

- Pollock, Jackson

- Pousette-Dart, Richard

- Rothko, Mark

- Smith, David

- Still, Clyfford

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Deciphering the Flowers” by Sheena Wagstaff

- 82nd & Fifth: “Gesture” by Nicholas Cullinan

- The Artist Project: “Mark Bradford on Clyfford Still”

- The Artist Project: “Robert Longo on Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) “

- The Artist Project: “Wenda Gu on Robert Motherwell’s Lyric Suite “

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Croce’s Aesthetics

The Neapolitan Benedetto Croce (1860–1952) was a dominant figure in the first half of the twentieth century in aesthetics and literary criticism, and to lesser but not inconsiderable extent in philosophy generally. But his fame did not last, either in Italy or in the English speaking world. He did not lack promulgators and willing translators into English: H. Carr was an early example of the former, R. G. Collingwood was perhaps both, and D. Ainslie did the latter service for most of Croce’s principal works. But his star rapidly declined after the Second World War. Indeed it is hard to find a figure whose reputation has fallen so far and so quickly; this is somewhat unfair not least because Collingwood’s aesthetics is still studied, when its many of its main ideas are often thought to have been borrowed from Croce. The causes are a matter for speculation, but two are likely. First, Croce’s general philosophy was very much of the preceding century. As the idealistic and historicist systems of Bradley, Green, and Joachim were in Britain superseded by Russell, Moore and Ayer, and analytical philosophy in general, Croce’s system was swept away by new ideas on the continent—from Heidegger and Sartre on the one hand to deconstructionism on the other. Second, Croce’s manner of presentation in his famous early works now seems, not to put too fine a point on it, dismissively dogmatic; it is full of the youthful conviction and fury that seldom wears well. On certain key points, opposing positions are characterized as foolish, or as confused expressions of simple truths that only waited upon Croce to articulate properly (yet his later exchange with John Dewey—see Croce 1952, Douglas 1970, Vittorio 2012—finds him more earnestly accountable). Of course, these dismissals carry some weight—Croce’s reading is prodigious and there is far more insight beneath the words than initially meets the eye—but unless the reader were already convinced that here at last is the truth, their sheer number and vehemence will arouse mistrust. And since the early works, along with his long running editorship of the journal La Critica , rocketed him to such fame and admiration, whereas later years were devoted among other things to battling with while being tolerated by fascists, it’s not surprising that he never quite lost this habit.

Nevertheless, Croce’s signal contribution to aesthetics—an interesting new angle on the idea that art is expression—can be more or less be detached from the surrounding philosophy and polemics. In what follows, we will first see the doctrine as connected to its original philosophical context, then we will attempt to snip the connections.

1. The Four Domains of Spirit (or Mind)

2. the primacy of the aesthetic, 3. art and aesthetics, 4.1 the double ideality of the work of art, 4.2 the role of feeling, 4.3 feeling, expression and the commonplace, 5. natural expression, beauty and hedonic theory, 6. externalization, 7. judgement, criticism and taste, 8. the identity of art and language, 9. later developments, 10.1 acting versus contemplation, 10.2 privacy, 10.3 the view of language, 11. conclusion, primary sources, secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries.

We are confining ourselves to Croce’s aesthetics, but it will help to have at least the most rudimentary sketch in view of his rather complex general philosophy.

In Italy at the beginning of the twentieth century, the prevailing philosophy or ‘world-view’ was not, as in England, post-Hegelian Idealism as already mentioned, but the early forms of empiricist positivism associated with such figures as Comte and Mach. Partly out of distaste for the mechanism and enshrinement of matter of such views, and partly out of his reaction, both positive and negative, to the philosophy of Hegel, Croce espoused what he called ‘Absolute Idealism’ or ‘Absolute Historicism’. A constant theme in Croce’s philosophy is that he sought a path between the Scylla of ‘transcendentalism’ and the Charybdis of ‘sensationalism’, which for most purposes may be thought of as co-extensive with rationalism and empiricism. For Croce, they are bottom the same error, the error of abstracting from ordinary experience to something not literally experienceable. Transcendentalism regards the world of sense to be unreal, confused or second-rate, and it is the philosopher, reflecting on the world in a priori way from his armchair, who sees beyond it, to reality. What Croce called ‘Sensationalism’, on the other hand, regards only instantaneous impressions of colour and the like as existing, the rest being in some sense a mere logical construction out of it, of no independent reality. The right path is what Croce calls immanentism : All but only lived human experience, taking place concretely and without reduction, is real. Therefore all Philosophy, properly so-called, is Philosophy of Spirit (or Mind), and is inseparable from history. And thus Croce’s favoured designations, ‘Absolute Idealism’ or ‘Absolute Historicism’.

Philosophy admits of the following divisions, corresponding to the different modes of mental or spiritual activity. Mental activity is either theoretic (it understands or contemplates) or it is practical (it wills actions). These in turn divide: The theoretic divides into the aesthetic, which deals in particulars (individuals or intuitions), and logic or the intellectual domain, which deals in concepts and relations, or universals. The practical divides into the economic—by which Croce means all manner of utilitarian calculation—and the ethical or moral. Each of the four domains are subject to a characteristic norm or value: aesthetic is subject to beauty, logic is subject to truth, economic is subject to the useful (or vitality), and the moral is subject to the good. Croce devoted three lengthy books written between 1901 and 1909 to this overall scheme of the ‘Philosophy of Spirit’: Aesthetic (1901) and (1907) (revised), Logic (1909) and the Philosophy of the Practical (1908), the latter containing both the economic and ethics (in today’s use of term you might call the overall scheme Croce’s metaphysics , but Croce himself distanced himself from that appellation; there is also some sense in calling it philosophy of mind ).

Philosophers since Kant customarily distinguish intuitions or representations from concepts or universals. In one sense Croce follows this tradition, but another sense his view departs radically. For intuitions are not blind without concepts; an intuitive presentation (an ‘intuition’) is a complete conscious manifestation just as it is, in advance of applying concepts (and all that is true a priori of them is that they have a particular character or individual physiognomy—they are not necessarily spatial or temporal, contra Kant). To account for this, Croce supposes that the modes of mental activity are in turn arranged at different levels. The intellect presupposes the intuitive mode—which just is the aesthetic—but the intuitive mode does not presuppose the intellect. The intellect—issuing in particular judgements—in turn is presupposed by the practical, which issues among other things in empirical laws. And morality tells the practical sciences what ends in particular they should pursue. Thus Croce regarded this as one of his key insights: All mental activity, which means the whole of reality, is founded on the aesthetic, which has no end or purpose of its own, and of course no concepts or judgements. This includes the concept of existence or reality: the intuition plus the judgement of existence is what Croce calls perception, but itself is innocent of it.

To say the world is essentially history is to say that at the lowest level it is aesthetic experiences woven into a single fabric, a world-narrative, with the added judgement that it is real, that it exists. Croce takes this to be inevitable: the subjective present is real and has duration; but any attempt to determine its exact size is surely arbitrary. Therefore the only rigorous view is that the past is no less real than the present. History then represents, by definition, the only all-encompassing account of reality. What we call the natural sciences then are impure, second-rate. Consider for example the concept of a space-time point . Plainly it is not something anyone has ever met with in experience; it is an abstraction, postulated as a limit of certain operations for the convenience of a ‘theory’. Croce would call it a pseudo-concept, and would not call the so-called ‘empirical laws’ in which it figures to be fit subjects for truth and knowledge. Its significance, like that of other pseudo-concepts, is pragmatic.

In fact the vast majority of concepts—house, reptile, tree—are mere adventitious collections of things that are formulated in response to practical needs, and thus cannot, however exact the results of the corresponding science, attain to truth or knowledge. Nor do the concepts of mathematics escape the ‘pseudo’ tag. What Croce calls pure concepts, in contrast, are characterised by their possession of expressiveness, universality and concreteness, and they perform their office by a priori synthesis (this accounts for character mentioned above). What this means it that everything we can perceive or imagine—every representation or intuition—will necessarily have all three: there is no possible experience that is not of something concrete, universal in the sense of being an instance of something absolutely general, and expressive, that is, admitting of verbal enunciation. Empirical concepts, then, like heat , are concrete but not universal; mathematical concepts, like number , are universal but not concrete. Examples of pure concepts are rare, but those recognized by Croce are finality, quality and beauty . Such is the domain of Logic, in Croce’s scheme.

A critical difference, for our purposes, between Croce’s ideas and those of his apparent follower Collingwood, emerges when we ask: what are the constituents of the intuition? For Collingwood—writing in the mid-1930s—intuitions are built up out of sense-data, the only significant elaboration of Russell’s doctrine being that sense-data are never simple, comprising what analysis reveals as sensory and affective constituents. For Croce the intuition is an organic whole, such that to analyze it into atoms is always a false abstraction: the intuition could never be re-built with such elements. (Although a deadly opponent of formal logic, Croce did share Frege’s insight that the truly meaningful bit of language is the sentence; ‘only in the context of sentence does a word have a meaning’, wrote Frege in 1884).

With such an account of ‘the aesthetic’ in view, one might think that Croce intends to cover roughly the same ground as Kant’s Transcendental Aesthetic, and like Kant will think of art as a comparatively narrow if profound region of experience. But Croce takes the opposite line (and finds Kant’s theory of beauty and art to have failed at precisely this point): art is everywhere, and the difference between ordinary intuition and that of ‘works of art’ is only a quantitative difference ( Aes. 13). This principle has for Croce a profound significance:

We must hold firmly to our identification, because among the principal reasons which have prevented Aesthetic, the science of art, from revealing the true nature of art, its real roots in human nature, has been its separation from the general spiritual life, the having made of it a sort of special function or aristocratic club…. There is not … a special chemical theory of stones as distinct from mountains. In the same way, there is not a science of lesser intuition as distinct from a science of greater intuition, nor one of ordinary intuition as distinct from artistic intuition. ( Aes. 14)

But the point is not that every object is to some degree a work of art. The point is that every intuition has to some degree the qualities of the intuition of a work of art; it’s just that the intuition of a work of art has them in much greater degree.

4. Intuition and Expression

We now reach the most famous and notorious Crocean doctrine concerning art. ‘To intuit’, he writes, ‘is to express’ ( Aes. 11); ‘intuitive knowledge is expressive knowledge’. There are several points that have to be in place in order to understand what Croce means by this, because it obviously does not strike one as initially plausible.

For our purposes, it is simplest to regard Croce as an idealist, for whom there is nothing besides the mind. So in that sense, the work of art is an ideal or mental object along with everything else; no surprise there, but no interest either. But he still maintains the ordinary commonplace distinction between mental things—thoughts, hopes and dreams—and physical things—tables and trees. And on this divide, the work of art, for Croce, is still a mental thing. In other words, the work of art in doubly ideal; to put it another way, even if Croce were a dualist —or a physicalist with some means of reconstructing the physical-mental distinction—the work of art would remain mental. In what follows, then, except where otherwise noted, we shall treat Croce is being agnostic as between idealism, physicalism, or dualism (see PPH 227).

This claim about the ontological status of works of art means that a spectator ‘of’ a work of art—a sonata, a poem, a painting—is actually creating the work of art in his mind. Croce’s main argument for this is the same as, therefore no better but no worse than, Russell’s argument from the relativity of perception to sense-data. The perceived aesthetic qualities of anything vary with the states of the perceiver; therefore in speaking of the former we are really speaking of the latter ( Aes. 106; Croce does not, it seems, consider the possibility that certain states of the perceiver might be privileged, but it is evident that he would discount this possibility). Now the Crocean formulation—to intuit is to express—perhaps begins to make sense. For ‘intuition’ is in some sense a mental act , along with its near-cognates ‘representation’, ‘imagination’, ‘invention’,‘vision’, and ‘contemplation.’ Being a mental act, something we do, it is not a mere external object.

Feeling, for Croce, is necessarily part of any (mental) activity, including bare perception—indeed, feeling is a form of mental activity (it is part of his philosophy that there is never literally present to consciousness anything passive). We are accustomed to thinking of ‘artistic expression’ as concerned with specific emotions that are relatively rare in the mental life, but again, Croce points out that strictly speaking, we are thinking of a quantitative distinction as qualitative. In fact feeling is nothing but the will in mental activity, with all its varieties of thought, desire and action, its varieties of frustration and satisfaction ( Aes. 74–6). The only criterion of ‘art’ is coherence of expression, of the movement of the will (for a comparison with Collingwood’s similar doctrine, see Kemp 2003: 173–9).

Because of this, Croce discounts certain aesthetic applications of the distinction between form and content as confused. The distinction only applies at a theoretical level, to a posited a priori synthesis ( EA 39–40). At that level, the irruption of an intuition just is the emergence of a form (we are right to speak of the formation of intuition, that intuitions are formed ). At the aesthetic level—one might say at the phenomenological level—there is no identification of content independently of the forms in which we meet it, and none of form independently of content. It makes no sense to speak of a work of art’s being good on form but poor on content, or good on content but poor on form.

When Croce says that intuition and expression are the same phenomenon, we are likely to think: what does this mean for a person who cannot draw or paint, for example? Even if we allow Croce his widened notion of feeling, surely the distinction between a man who looks at a bowl of fruit but cannot draw or paint it, and the man who does draw or paint it, is precisely that of a man with a Crocean intuition but who cannot express it, and one who has both. How then can expression be intuition?

Croce comes at this concern from both sides. On one side, there is ‘the illusion or prejudice that we possess a more complete intuition of reality than we really do’ ( Aes. 9). We have, most of the time, only fleeting, transitory intuitions amidst the bustle of our practical lives. ‘The world which as rule we intuit is a small thing’, he writes; ‘It consists of small expressions … it is a medley of light and colour’ ( Aes. 9). On the other side, if our man is seriously focussed on the bowl of fruit, it is only a prejudice to deny that then he is to that extent expressing himself—although, according to Croce, ordinary direct perception of things, as glimpsed in photography, will generally be lacking the ‘lyrical’ quality that genuine artists give to their works (though this particular twist is a later addition; see section 9 below).

There is another respect in which Croce’s notion of expression as intuition departs from what we ordinarily think of in connection with the word ‘expression’. For example we think unreflectively of wailing as a natural expression of pain or grief; generally, we think of expressive behaviour or gestures as being caused, at least paradigmatically, by the underlying emotion or feelings. But Croce joins a long line of aestheticians in attempting a sharp distinction between this phenomenon and expression in art. Whereas the latter is the subject of aesthetics, the former is a topic for the natural sciences—‘for instance in Darwin’s enquiries into the expression of feeling in man and in the animals’ ( PPH 265; cf. Aes. 21, 94–7). In an article he wrote for the Encyclopaedia Britannica , speaking of such ‘psychophysical phenomena’, he writes:

…such ‘expression’, albeit conscious, can rank as expression only by metaphorical licence, when compared with the spiritual or aesthetic expression which alone expresses, that is to say gives to the feeling a theoretical form and converts into language, song, shape. It is in the difference between feeling as contemplated (poetry, in fact), and feeling as enacted or undergone, that lies the catharsis, the liberation from the affections, the calming property which has been attributed to art; and to this corresponds the aesthetic condemnation of works of art if, or in so far as, immediate feeling breaks into them or uses them as an outlet. ( PPH 219).

Croce is no doubt right to want to distinguish these things, but whether his official position—that expression is identical to intuition—will let him do so is another matter; he does not actually analyze the phenomena in such a way as to deduce, with the help of his account of expression, the result. He simply asserts it. But we will wait for our final section to articulate criticisms.

Croce’s wish to divorce artistic expression from natural expression is partly driven by his horror at naturalistic theories of art. The same goes for his refusal to rank pleasure as the aim, or at least an aim, of art ( Aes. 82–6). He does not of course deny that aesthetic pleasures (and pains) exist, but they are ‘the practical echo of aesthetic value and disvalue’ ( Aes. 94). Strictly speaking, they are dealt with in the Philosophy of the Practical, that is, in the theory of the will, and do not enter into the theory of art. That is, if the defining value of the Aesthetic is beauty , the defining value of the Practical is usefulness . In the Essence of Aesthetic ( EA 11–13) Croce points out that the pleasure is much wider than the domain of art, so a definition of art as ‘what causes pleasure’ will not do. Croce does speak of the ‘truly aesthetic pleasure’ had in beholding the ‘aesthetic fact’ ( Aes. 80). But perhaps he is being consistent. The pragmatic pleasure had in beholding beauty is only contingently aroused, but in point of fact it always is aroused by such beholding, because the having of an intuition is an act of mind, and therefore the will is brought into play.

The painting of pictures, the scrape of the bow upon strings, the chanting or inscription of a poem are, for Croce, only contingently related to the work of art, that is, to the expressed intuition. By this Croce does not mean to say that for example the painter could get by without paint in point of fact; the impossibility of say the existence of Leonardo’s Last Supper without his having put paint on the wall of Santa Maria delle Grazie not an impossibility in principle, but it is a factual impossibility, like that of a man jumping to the Moon. What he is doing is always driven by the intuition, and thereby making it possible for others to have the intuition (or rather, an intuition). First, the memory—though only contingently—often requires the physical work to sustain or develop the intuition. Second, the physical work is necessary for the practical business of the communication of the intuition.

For example the process of painting is a closely interwoven operation of positive feedback between the intuitive faculty and the practical or technical capacity to manipulate the brush, mix paint and so on:

Likewise with the painter, who paints upon canvas or upon wood, but could not paint at all, did not the intuited image, the line and colour as they have taken shape in the fancy, precede , at every stage of the work, from the first stroke of the brush or sketch of the outline to the finishing touches, the manual actions. And when it happens that some stroke of the brush runs ahead of the image, the artist, in his final revision, erases and corrects it.

It is, no doubt, very difficult to perceive the frontier between expression and communication in actual fact, for the two processes usually alternate rapidly and are almost intermingled . But the distinction is ideally clear and must be strongly maintained… The technical does not enter into art, but pertains to the concept of communication. ( PPH 227–8, emphasis added; cf. Aes . 50–1, 96–7, 103, 111–17; EA 41–7)

He also defines technique as ‘knowledge at the service of the practical activity directed to producing stimuli to aesthetic reproduction’ ( Aes. 111). Again, we defer criticism to the conclusion.

The first task of the spectator of the work of art—the critic—is for Croce simple: one is to reproduce the intuition, or perhaps better, one is to realize the intuition, which is the work of art. One may fail, and Croce is well aware that one may be mistaken ; ‘haste, vanity, want of reflexion, theoretic prejudices’ may bring it about that one finds beautiful what is not, or fail to find beautiful what is ( Aes. 120). But given the foregoing strict distinction between practical technique and artistic activity properly so-called, his task is the same as that of the artist :

How could that which is produced by a given activity be judged a different activity? The critic may be a small genius, the artist a great one … but the nature of both must remain the same. To judge Dante, we must raise ourselves to his level: let it be well understood that empirically we are not Dante, nor Dante we; but in that moment of contemplation and judgement, our spirit is one with that of the poet, and in that moment we and he are one thing. ( Aes. 121)

Leave aside the remark that we become identical with the poet. If by taste we mean the capacity for aesthetic judgement—that is, the capacity to find beauty—and by genius we mean the capacity to produce beauty, then they are the same: the capacity to realize intuitions.

In Croce’s overall philosophy, the aesthetic stands alone: in having an intuition, one has succeeded entirely insofar as aesthetic value is concerned. Therefore there cannot be a real question of a ‘standard’ of beauty which an object might or might not satisfy. Thus Croce says:

…the criterion of taste is absolute, but absolute in a different way from that of the intellect, which expresses itself in ratiocination. The criterion of taste is absolute, with the intuitive absoluteness of the imagination. ( Aes. 122)

Of course there is as a matter of fact a great deal of variability in critical verdicts. But Croce believes this is largely due to variances in the ‘psychological conditions’ and the physical circumstance of spectators ( Aes. 124). Much of this can be offset by ‘historical interpretation’ ( Aes. 126); the rest, one presumes, are due to disturbances already mentioned: ‘haste, vanity, want of reflexion, theoretic prejudices’ ( Aes. 120). Also one must realize that for Croce, all that Sibley famously characterized as aesthetic concepts—not just gracefulness, delicacy and so on but only aesthetically negative concepts like ugliness—are really variations on the over-arching master-concept beauty .

The title of the first great book of Croce’s career was ‘Aesthetic as a Science of expression and general linguistic ’ (emphasis added). There are several interconnected aspects to this.

Croce claims that drawing, sculpting, writing of music and so on are just as much ‘language’ as poetry, and all language is poetic; therefore ‘ Philosophy of language and philosophy of art are the same thing ’ ( Aes. 142; author’s emphasis). The reason for this is that language is to be understood as expressive; ‘an emission of sounds which expresses nothing is not language’ ( Aes. 143). From our perspective, we might regard Croce as arguing thus: (1) Referential semantics—scarcely mentioned by Croce—necessarily involves parts of speech. (2) However:

It is false to say that a verb or noun is expressed in definite words, truly distinguishable from others. Expression is an indivisible whole. Noun and verb do not exist in it, but are abstractions made by us, destroying the sole linguistic reality, which is the sentence . ( Aes. 146)

If we take this as asserting the primacy of sentence meaning—glossing over the anti-abstraction remark which is tantamount to a denial of syntactic compositionality—then together with (3) a denial of what in modern terms would be distinction between semantic and expressive meaning, or perhaps in Fregean terms sense and tone, then it is not obvious that the resulting picture of language would not apply equally to, for example, drawing. In that case, just as drawings cannot be translated, so linguistic translation is impossible (though for certain purposes, naturally, we can translate ‘relatively’; Aes. 68).

Interestingly, Croce does not think of all signs as natural signs, as lightning is a sign of thunder; on the contrary, he thinks of ‘pictures, poetry and all works of art’ as equally conventional—as ‘ historically conditioned ’ ( Aes. 125; authors emphasis).

There is no doubt that on this point Croce was inspired by his great precursor, the Neapolitan Giambattista Vico (1668–1744). According to Croce ( Aes. 220–34) Vico was the first to recognise the aesthetic as a self-sufficient and non-conceptual mode of knowledge, and famously he held that all language is substantially poetry. The only serious mistake in this that Croce found was Vico’s belief in an actual historical period when all language was poetry; it was the mistake of substituting a concrete history for ‘ideal history’ ( Aes. 232).

As he became older, there was one aspect of his aesthetics that he was uneasy with. In the Aesthetic of 1901 ( Aes. 82–7, 114), and again in Essence of Aesthetic of 1913 ( EA 13–16) , he had been happy to deduce from his theory that art cannot have an ethical purpose. The only value in art is beauty. But by 1917, in the essay The Totality of Artistic Expression ( PPH 261–73), his attitude towards the moral content of art is more nuanced. This may have been only a shift of emphasis, or, charitably perhaps, drawing out a previously unnoticed implication: ‘If the ethical principle is a cosmic [universal] force (as it certainly is) and queen of the world, the world of liberty, she reigns in her own right, while art, in proportion to the purity with which she re-enacts and expresses the motions of reality, is herself perfect’ ( PPH 267). In other words, he still holds that to speak of a moral work of art would not impinge upon it aesthetically; likewise to speak of an immoral work, for the values of the aesthetic and moral domains are absolutely incommensurable. It is not merely an assertion that within the domain of pure intuition, the concepts simply don’t apply; that would merely beg the question. He means that a pure work of art cannot be subject to moral praise or blame because the Aesthetic domain exists independently of and prior, in the Philosophy of Spirit, to the Ethical.

In the Encyclopaedia article of 1928, Croce asserts positively that the moral sensibility is a necessary condition of the artist:

The foundation of all poetry is therefore the human personality, and since the human personality fulfills itself morally, the foundation of all poetry is the moral conscience. ( PPH 221)

Still it’s possible to read him as not having changed his view. For instance, Shakespeare could not have been Shakespeare without seeing into the moral heart of man, for morality is the highest domain of spirit. But we have to distinguish between the moral sensibility—the capacity to perceive and feel moral emotions—and the capacity to act morally. Croce’s position is that only the first is relevant to art.

The early emphasis on beauty is downplayed in subsequent writing in favour of the successful work art as expression, as constituting a ‘lyrical intuition’. In Essence of Aesthetic he writes:

…what gives coherence and unity to the intuition is feeling: the intuition is really such because it represents a feeling, and can only appear from and upon that. Not the idea, but the feeling, is what confers upon art the airy lightness of a symbol: an aspiration enclosed in the circle of a representation—that is art; and in it the aspiration alone stands for the representation, and the representation alone for the aspiration. ( EA 30)

Croce still holds that art is intuitive, a-logical or nonconceptual, and therefore by ‘it represents a feeling’ he does not mean that our aesthetic mode of engagement involves that concept, and he does not mean that art is to be understood as symbolic, implying a relation which would require an intellectual act of mind to apprehend. Both would imply that our mode of aesthetic engagement would be something more, or something other than, the aesthetic, which is as always the intuitive capacity. The point is simply that our awareness of the form of the intuition in nothing but our awareness of the unifying currents of feeling running through it. It is a claim about what it is that unifies an intuition, distinguishes it from the surrounding, relatively discontinuous or confused intuition. This is, in effect, a claim about the nature of beauty:

An appropriate expression, if appropriate, is also beautiful, beauty being nothing but the precision of the image, and therefore of the expression. …( EA 48).

Expression and beauty are not two concepts, but a single concept, which it is permissible to designate with either synonymous word … ( EA 49).

Genuinely new in the 1917 essay was Croce’s appealing but enigmatic claim that art is in a sense ‘universal’, is concerned with the ‘totality’:

To give artistic form to a content of feeling means, then, impressing upon it the character of totality, breathing into it the breath of the cosmos. Thus understood, universality and artistic form are not two things but one. ( PPH 263).

In intuition, the single pulsates with the life of the whole, and the whole is in the life of the single. Every genuine artistic representation is itself and is the universe, the universe in that individual form, and that individual form as the universe. In every utterance, every fanciful [imaginative] creation, of the poet, there lies the whole of human destiny, all human hope, illusions, griefs, joys, human grandeurs and miseries, the whole drama of reality perpetually evolving and growing out of itself in suffering and joy. ( PPH 262)

Croce—and undoubtedly the political situation in Italy in 1917 played a role in this—was anxious to assert the importance of art for humanity, and his assertion of it is full of feeling. And the claim marks a decisive break from earlier doctrine: form is now linked with universality rather that with particular feelings. But it is difficult to see beyond such metaphors as ‘impressing upon it the character of totality’ (not even with the help of Croce’s Logic ). One is reminded of the Kantian dictum that in aesthetics we ‘demand universality’ in our judgements, but there are no explicit indications of such. There is one piece of Crocean philosophy behind it: Since art takes place prior to the intellect, so the logical distinction between subject and predicate collapses; therefore perhaps at least one barrier is removed from speaking of the ‘universality of art’. But that does not indicate what, positively, it means. It obvious that there is something right about speaking of the ‘universal character’ of a Beethoven or a Michelangelo as opposed to the pitiful, narrow little spectacle of this month’s pop band, but Croce doesn’t tell us what justifies or explains such talk (various others have reached a similar conclusion; see Orsini p. 214). Still, that doesn’t mean that he had no right to proclaim it, and perhaps not to count his readers as agreeing to it.

10. Problems

There is a lot of Croce’s aesthetics that we have not discussed, including his criticisms of the discipline of Rhetoric (Aes. 67–73; PPH 233–35), his disparagement of ‘genre criticism’—that is, his doctrine that there are ultimately no aesthetic differences amongst different kinds of art (Aes. 111–17, EA 53–60, PPH 229–33)—and his condemnation of psychological and other naturalistic views of art ( Aes. 87–93; EA 41–7). There is also his magnificent if contentious précis of the history of aesthetics ( Aes. 155–474). But these are points of relative detail; the theory is whole is sufficiently well before us now to conclude by mentioning some general lines of criticism.

The equation of intuition with expression as at section 4.3 simply is not, in end, plausible. C. J. Ducasse (1929) put his finger on it. When we look at a vase full of flowers, it simply does not matter how closely or in what manner we attend to it; we do not create a ‘work of art’ unless we draw or paint it. Croce has lost sight of the ordinary sense of passively contemplating and doing something; between reading and writing, looking and drawing, listening and playing, dancing and watching. Of course all the first members of these pairs involve a mental action of a kind, and there are important connections between the first members and the corresponding seconds—perhaps in terms of what Berenson calls ideated sensations —but that is not to say that there are not philosophically crucial distinctions between them.