Download the Report | Share

Critical Issues in Transportation 2019

Policy snapshot.

INTRODUCTION

Driverless cars maneuvering through city streets. Commercial drones airlifting packages. Computer-captained ships navigating the high seas. Revolutionary changes in technology are taking us to the threshold of a bold and unprecedented era in transportation.

These technologies promise improvements in mobility, safety, efficiency, and convenience, but do not guarantee them. Will the technological revolution reduce congestion, fuel use, and pollution or make them worse by encouraging more personal trips and more frequent freight shipments?

The transportation sector also faces other unprecedented challenges. It needs to (1) sharply curb greenhouse gas emissions to slow the rate of climate change and (2) respond to more climate-related extreme weather. It must serve a growing population and cope with worsening highway congestion. It needs to maintain and upgrade a massive system of roads, bridges, ports, waterways, airports, and public transit and determine how to pay for those improvements. The transportation sector also needs to adapt to shifts in trade, energy, and funding sources that affect all modes of transportation. How will these challenges affect the transportation systems on which consumers and the economy depend?

The answers to these and other questions are critically important. Transportation plays a central role in society and the economy but is frequently taken for granted. Reflect, though, on how much you depend on reliable and affordable transportation to access work, friends and family, recreation, shopping, and worship. Then visualize the transportation networks needed for the daily movement of hundreds of millions of vehicles, ships, planes, and trains to satisfy both personal needs and commercial demands. These networks are enormous and complex. The transportation systems the economy and lifestyles rely on may be challenged dramatically in the coming decades in ways that cannot always be anticipated.

A national conversation among policy makers and citizens about how the country should respond to these challenges is urgently needed. Stakeholders need to debate, discuss, and analyze how transportation can evolve to meet growing and evolving needs and adapt to changes in society, technology, the environment, and public policy.

To spur that conversation, the Transportation Research Board (TRB) identified and organized an array of important issues under 12 key topics. In each of these areas, TRB posed a series of crucial questions to help guide thinking, debate, and discovery during the next 5 to 10 years. These 12 topics are neither comprehensive nor mutually exclusive, and no one can know how the future will unfold. But TRB thinks that asking the right questions, even if they cannot be fully answered, helps to motivate the analysis, discussion, and debate required to prepare for the potentially unprecedented changes ahead. This document is an abbreviated version of a more thorough discussion of the critical issues in transportation. It can be accessed at https://www.nap.edu/download/25314 .

Transformational Technologies and Services: Steering the Technology Revolution

All around the globe, companies are testing automated cars, trucks, ships, and aircraft. Pilot vehicles are already in operation. Some products are almost certain to enter the marketplace in the next few years. Driverless vehicles equipped with artificial intelligence may revolutionize transportation. Perhaps even sooner, vehicles connected to one another with advanced high-speed communication technologies may greatly reduce crashes How will vehicle automation—along with connected vehicles and shared ride, car, bike, and scooter services—transform society? These revolutionary technologies and services can potentially speed deliveries, prevent crashes, and ease traffic congestion and pollution. But they could also cause more congestion and more pollution and exacerbate sprawl and inequity. How do we determine and guide, as necessary, the direction of these changes? How the future unfolds depends on which technologies and services consumers and businesses embrace and how policy makers respond. While we do not know what the future will bring, the changes could be momentous. For example, if we encourage people to pool rides in driverless electric cars, we could see the service, cost, and environment improve. What policies would best reduce traffic congestion and emissions and improve accessibility for the disabled, elderly, and economically disadvantaged? How do we benefit most from the advent of connected and automated vehicles and potentially transformative transportation services?.

Serving a Growing and Shifting Population

The U.S. population is expected to grow about 1 percent annually, with highway use increasing similarly. But this growth will not be spread evenly across the country. Urban areas are growing more quickly, particularly clusters of metro areas known as “megaregions,” while many rural areas decline. At the same time, low-density residential development on the edges of urban areas continues to grow the fastest, which increases traffic and escalates emissions. Although many Millennials are settling in urban centers, more are locating on the edges of cities where Baby Boomers also prefer to live. How do we adjust to and guide travel demand so we are not overwhelmed with more roads, traffic, and emissions as a result of these geographic preferences? Megaregions in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West have emerged as economic engines for the economy, but they also have the worst traffic congestion. And their traffic volumes continue to grow faster than new transportation facilities can be built. What are the best policies and modes for improving travel within each megaregion? How do we ensure that megaregions are well connected to the rest of the nation and the world? How can rural populations be ensured adequate access to jobs and services? How is that access changing? Which policies are needed to provide adequate rural access?

Energy and Sustainability: Protecting the Planet

The Earth’s changing climate poses one of the most important threats humanity has ever faced. To avoid catastrophic changes, all sectors of the economy need to make drastic cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. Vehicles, planes, ships, and other forms of transport emit more greenhouse gases than any other sector of the economy in the United States. And that share is growing because other sectors of the economy are reducing their emissions faster than transportation. Personal vehicles could rely on electrification using batteries or hydrogen as one way to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Planes, ships, and trucks pose major obstacles to this objective because of their dependence on fossil fuels that pack more power than alternatives. What are the most effective and cost-effective ways of achieving the drastic reductions needed in fossil fuel consumption? What are the appropriate roles for the public and private sectors in hastening this transition? How can the shift to electric vehicles be accomplished without overwhelming the power grid? Sustainability requires that there be long-term consideration of the implications of decisions and policies on social, economic, and environmental systems. Examples include making decisions based on life-cycle cost considerations and the long-term vitality of communities and key natural environmental systems. How can consideration of long-term sustainability goals be better incorporated into public policy debates and decisions about transportation?

Resilience and Security: Preparing for Threats

Recent floods, storms, fires, and hurricanes have disrupted the lives of millions and caused hundreds of billions of dollars in damage. Extreme weather events are exacerbated by climate change, and scientists predict things will get worse. Extreme weather and other natural disasters pose huge and costly threats to the transportation infrastructure. Public officials face the challenge of making vulnerable highways, bridges, railroads, transit stations, waterways, airports, and ports more resilient to climate change and other threats. What policies and strategies would help them meet this challenge? How do we set priorities, cope with disruptions, and pay for these adaptations? Terrorists often choose transportation facilities as their targets. Airports and airlines have increased security to guard against terrorism, but other modes of transport— buses, trains, and ships—are more vulnerable. How do we protect these forms of transport without unduly slowing the movement of people and goods? We also need to address the risks of new technologies. Drones, for example, can be used by terrorists or drug smugglers. Automated vehicles and aircraft are vulnerable to hackers. And all types of transport depend on Global Positioning Systems (GPSs), for which there is no back-up system. How do we make technological advances more secure and resilient?

Safety and Public Health: Safeguarding the Public

We depend on motorized transportation, but we pay a price with our health with deaths, injuries, and diseases. Routine highway travel is the source of the vast majority of transportrelated deaths and a significant portion of transport-related pollution in the United States. Even though there have been improvements in vehicles and facilities, most crashes are preventable. How do we muster the political will to adopt the most effective measures to reduce casualties and diseases caused by transportation? How do we encourage the use of the safest vehicle and road designs, reduce alcohol- and drug-impaired driving, and manage operator fatigue? Also, how do we curb driver distractions, especially in semi-automated vehicles that do not require full attention except in emergencies when multitasking drivers may be unprepared to respond? Marijuana legalization and opioid addiction may lead to more people driving while impaired. In addition, pedestrian and cyclist deaths are increasing. What can we do to address these problems? What successes from other countries can be applied? Air pollution comes from many sources, but some transport emissions, such as the particulates from burning diesel fuel, are especially harmful to people. People living near roads, ports, distribution centers, railyards, and airports—often the marginalized and the poor—are exposed to more of these types of vehicle emissions. How do we best address these problems?

Equity: Serving the Disadvantaged

The United States is prosperous, but not uniformly. More than 40 million Americans live in poverty. Outside central cities, an automobile is essential for access to jobs and a piece of the American dream, but about 20 percent of households with incomes below $25,000 lack a car. In addition, nearly 40 million Americans have some form of disability, of whom more than 16 million are working age. And the population is aging: the number of people older than 65 will increase by 50 percent from 49 million now to 73 million by 2030. Access to jobs, health care, and other services can be expanded through transportation policies and programs and technology, but these approaches need to be affordable and effective. This is a particular challenge in sparsely populated areas. How do we help disadvantaged Americans get affordable access to work, health care, and other services and to family and friends? What policies would ensure that new technologies and services do not create new barriers to the disadvantaged or to rural residents? Also, as we expand transportation networks, how do we ensure that we are not harming low-income and minority neighborhoods?

Governance: Managing Our Systems

A complex web of institutions manages America’s transportation services. Many levels of government, from local to national, play important roles. Some functions, such as public transit, airports, and ports, are managed by thousands of special authorities across the country. This spider web of governance frequently limits efficiency. For example, urban transport networks often span jurisdictional boundaries, creating disagreement about which agency is responsible for which aspects of planning, funding, and management. Separate funding streams for specific transportation modes impede efforts to provide travelers with multi-modal options. How do we address these challenges, particularly as urban areas grow into megaregions? The federal government is responsible for interstate waterways and airspaces and for interstate commerce. However, federal leadership and funding for transportation supporting interstate commerce are waning, forcing state and local governments to take on a larger role. How do we ensure that there are efficient networks for interstate travel and international trade as the federal role declines? New private transportation services efficiently generate enormous data sets about trips. Such data can be helpful to agencies trying to manage system performance. Connected and automated vehicles will add even more information. How can public agencies gain access to these data streams to improve traffic flow while protecting privacy and proprietary information?

System Performance and Management: Improving the Performance of Transportation Networks

Highway congestion costs the nation as much as $300 billion annually in wasted time. Flight delays add at least another $30 billion. Clearly, demand for travel is outpacing growth in supply and the increasing congestion is costing us dearly. As the population grows, demand will only increase. However, expanding or building new roads, airports, and other facilities in urban areas is costly, time consuming, and often controversial. How can we serve growing demand in a financially, socially, and environmentally responsible manner? Transportation officials also need to squeeze more performance out of the existing networks. One way to do this is by managing demand: Charging drivers for peakperiod travel in congested areas, for example, has the potential to increase ride sharing and generate revenues for transit, bike paths, and sidewalks. While pricing is more effective than other approaches, it is also unpopular. How do we build public and political acceptance for demand management strategies that work? In the face of tight budgets, transportation officials must also figure out how to maintain the condition of roads, bridges, airports, and other assets for as long as possible. What research would help increase the durability of construction materials and designs? How do we speed adoption of new information to improve the life-cycle performance of transportation assets?

Funding and Finance: Paying the Tab

Fuel taxes and other user fees have traditionally paid for highways, bridges, airports, ports, and public transit. These user fees are generally fair and efficient ways to pay for the transportation infrastructure, which is valued in trillions of dollars. However, improving fuel efficiency undermines the revenue potential from the motor fuel taxes that have been the chief funding source for highways and transit. Since 1993, federal officials have not raised the fees that fund the federal share of surface transportation and have instead turned to general revenues. In addition, Congress has declined to raise aviation-related user fees, limiting funds for air traffic control and airports. Although most states have raised motor fuel taxes, state and local government officials are also turning to other sources as the revenues from these taxes decline. One is sales taxes, which can unfairly burden the poor. Also, officials are partnering with businesses to build and maintain roads and other assets. This approach has promising features, but relies on tolls or other charges that are controversial. With advances in technology, officials can charge highway users by the mile traveled. They could also charge more during peak periods to manage demand and more to gas-guzzling vehicles to reduce emissions. But the public is not widely aware of these options and is not enthusiastic about them when it is. Clearly, we need to find new ways to maintain and expand the transportation infrastructure. How do we build understanding of the need to invest in transportation assets, identify the best funding options, and reach consensus for action?

Goods Movement: Moving Freight

The economy and our lifestyles depend on an efficient system for moving freight. Although railroads and pipelines are privately owned, funded, and managed, the freight system also requires adequate public infrastructure—roads, airports, ports, and waterways—for private companies to carry the goods needed. Freight movement is expected to grow dramatically in the coming decades to serve the growing population and economy. Without more spending on public infrastructure, this trend could lead to more traffic bottlenecks and capacity problems, especially as overnight and same-day delivery become more popular. How do we provide additional capacity when and where it is needed and ensure that beneficiaries bear the cost? Government officials face the challenges of providing adequate infrastructure for the freight industry while setting a level playing field for competition among private carriers and across transportation modes. In doing so, they need to account and charge for the costs that trucks, aircraft, ships, and other vehicles impose on public infrastructure. This is a process that is both difficult and controversial. How can officials best foster competition and set fair user fees for the freight industry? Another challenge for the freight industry is how to reduce its large and growing share of greenhouse gas emissions. One way to do this is through technology: improving batteries and fuel cells to speed the shift to electric-powered vehicles and moving to automated vehicles. Another is by improving efficiency, such as ensuring more vehicles are carrying freight on return trips. How do we make these improvements effectively and affordably?

Institutional and Workforce Capacity: Providing a Capable and Diverse Workforce

Government transportation agencies face huge challenges and tight budgets. Their ability to rise to these challenges depends on having capable workers with the tools they need to do their jobs. These agencies have difficulty competing for and keeping talented workers. They simply cannot pay as much as private industry. How can officials attract and retain the best employees despite the pay disparities between the public and private sectors? Also, the changing nature of transportation is creating different requirements for the workforce. As a result, transportation organizations struggle to keep workers up to date in the skills they need. This problem is especially acute at the local government level in dealing with complex issues such as climate change and revolutionary new transportation services. How do we address these challenges? Automated trucks, trains, vessels, and aircraft will disrupt the transportation workforce in both the public and private sectors. What are the likely impacts of these technological changes on transportation jobs? What are the best ways to help displaced workers? With a growing, changing, and aging population, transportation organizations will need to hire new and diverse employees. How can managers attract more members of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups into the transportation field? How can they minimize the loss of expertise and experience when Baby Boomers retire?

Research and Innovation: Preparing for the Future

America is known for innovation. Our discovery and embrace of the new is fueled in large part by public investments in education and research. The revolutionary breakthroughs in transportation-related technology happened because of decades of public spending on basic research. In addition, steady improvements in the design, construction, operation, and management of transportation infrastructures have been spurred by research funded by government agencies. Public funding for research and education has never been more important, nor more uncertain. Many experiments are taking place in transportation across the country to meet the challenges of technological innovation and climate change. How do we record, evaluate, and share the results of these experiences and adopt innovations more quickly into standards and practices? Demands on transportation are growing as public spending on transportation research is declining. At the same time, public officials are often discouraged from taking risks. How do we encourage innovation in transportation agencies? How do we speed the pace of research to keep up with the major challenges transportation faces?

Modern civilization would not be possible without extensive, reliable transportation systems. Technology is poised to transform transportation and impact society and the environment in ways we cannot fully predict but must be prepared to manage. In addition to coping with a technological revolution, we also face hard questions about how to reduce transportation’s greenhouse gas emissions; make it more resilient, efficient, safe, and equitable; and pay the staggering costs of doing so. TRB framed what it thinks are the most important transportation questions to address in the next few years. It hopes this document will help spur and inform an urgently needed national debate about the future of transportation and help researchers frame and inform choices about the most promising paths forward. Join the debate. Analyze the options. Find new solutions. Our future depends on it. For a more thorough discussion of these issues go to https://www.nap.edu/download/25314 .

ABOUT THIS REPORT

- Download Free PDF

- Read Online

- Publication Details

- TRB Leaders Unveil Critical Issues

- TRB Critical Issues in Transportation Discussion with Executive Director Neil Pedersen

Copyright 2019 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved

The Geography of Transport Systems

The spatial organization of transportation and mobility

9.3 – Transport Safety and Security

Authors: dr. jean-paul rodrigue and dr. brian slack.

Safety and security issues concern both transportation modes and terminals that can be either a target for terrorism, a vector to conduct illegal activities, or even a form of warfare.

1. A New Context in Transport Security

While issues of safety and security have regularly preoccupied transport planners and managers, it is only recently that physical security has become an overriding issue. Over this, an important nuance must be provided between criminal activities and terrorism. While both seek to exploit the security weaknesses of transportation, they do so for very different reasons. Terrorism is a symbolic activity seeking forms of destruction and disruption to coerce a political, ideological, or religious agenda. In this context, transportation is mostly a target . Criminal activities seek an economic return from illegal transactions such as drugs, weapons, piracy, and illegal immigration. In this context, transportation is mostly a vector for illicit transactions. Concerns were already being raised in the past. Still, the tragic events of 9/11 thrust the issue of physical security into the public domain as never before and set in motion responses that have reshaped transportation in unforeseen ways. In addition, threats to health, such as the spread of pandemics, present significant challenges to transport planning and operations, as the COVID-19 pandemic underlined.

As locations where passengers and freight are assembled and dispersed, terminals have particularly been a focus of concern about security and safety. Because railway stations and airports are some of the most densely populated sites anywhere, crowd control and safety have been issues that have preoccupied managers for a long time. Access is monitored and controlled, and movements are channeled along pathways that provide safe access to and from platforms and gates. In the freight industry, security concerns have been directed toward worker safety and theft . Traditionally, freight terminals have been dangerous workplaces. With heavy goods being moved around yards and loaded onto vehicles using large mobile machines or manually, accidents were systemic. Significant improvements have been made over the years, through worker education and better organization of operations, but freight terminals are still comparatively hazardous.

The issue of theft has been one of the most severe problems confronting all types of freight terminals, especially where high-value goods are being handled. Docks have particularly been seen as places where organized crime has established control over local labor unions, particularly in the first half of the 20th century. With containerization, theft at port terminals declined substantially as the contents of containers remained hidden from those handling them. Further, access to freight terminals and distribution centers has been increasingly restricted, with workers screening and the deployment of security personnel helping control thefts. Most cargo thefts now occur during transit and when vehicles are parked in rest areas or streets. Thefts occurring in warehouses and terminals are less common but still significant .

The most visible emerging form of security threat is cybersecurity, to which transportation infrastructures and organizations are particularly vulnerable. The growth in information technologies and their associated networks has opened new forms of vulnerability as control and management systems can be remotely accessed. This has resulted in complex, interconnected corporate information networks that can be hacked and disrupted. There is a wide variety of reasons behind cyberattacks , but financial gains remain the main objective. In 2017, malware named NotPetya was released from the hacked servers of a Ukrainian software firm servicing a management program used by some of the world’s largest corporations, causing an estimated USD 10 billion in damage. Transportation and logistics firms such as Maersk and TNT were severely disrupted. In some cases, terminals and distribution centers were forced to cease operations because of inoperable computers.

The foundation of transport security includes several dimensions and potential measures:

- Dimensions . Particularly concerning the integrity of the passengers or cargo, the route, and the information systems (IT security) managing the transport chain.

- Measures . The set of procedures that can be implemented to maintain the integrity of the passengers or cargo, namely inspections, the security of facilities and personnel, as well as of the data and the supporting cybersecurity measures.

The expected outcomes of these measures include:

- Reduced risk of travel or trade disruptions in response to security threats.

- Improved security against theft and cargo diversion, with reductions in direct losses (cargo and sometimes the vehicle) and indirect costs (e.g. higher insurance premiums).

- Improved security against illegal transport of passengers and freight such as counterfeits, narcotics, weapons, and migrants.

- Improved reliance on information systems supporting the complex transactions generated by transport activities.

- Reduced risk of evasion of duties and taxes .

- Increased confidence in the international trading system by current and potential shippers of goods.

- Improved screening process (cost and time) and simplified procedures.

Still, despite the qualitative benefits, the setting and implementation of security measures come at a cost that must be assumed by the shippers and, eventually, by the consumers or the passengers. Airport security fees have become a standard component of airfares. It has been estimated that an increase of 1% in the costs of trading internationally would cause a decrease in trade flows in the range of 2 to 3%. Therefore, security-based measures could increase total costs between 1% and 3%, having a negative impact on international trade. Additionally, the impacts are not uniformly assumed as developing economies, particularly export-oriented economies, tend to have higher transport costs. A major goal is, therefore, to comply with security measures in the most cost-effective way.

2. Physical Security of Passengers

Airports have been the focus of security concerns for many decades. High-jacking aircraft came to the fore in the 1970s when terrorist groups in the Middle East exploited the lack of security to commandeer planes for ransom and publicity. Refugees fleeing dictatorships also found taking over aircraft a possible route to freedom. In response, the airline industry and the international regulatory body, ICAO, established screening procedures for passengers and luggage. This process seems to have worked in the short run with reductions in hijackings . However, terrorists changed their tactics by placing bombs in unaccompanied luggage and packages. The Air India crash off Ireland in 1985, the Lockerbie, Scotland, and the crash of Pan Am 103 in 1988 are illustrative. Another unusual issue is the deliberate crash of a flight by pilots committing suicide. In 2015, Germanwings 9525 was crashed by its co-pilot in the French Alps. In the prior year, Malaysia Airlines 370 crashed in the Indian Ocean allegedly through a similar cause. Still, air travel remains the safest transportation mode , with fatalities steadily decreasing over the years.

The growth in passenger traffic and the development of the hub and spoke networks greatly strained the security process. There were wide disparities in the effectiveness of passenger screening at different airports. Because passengers were routed by hubs, the number of passengers in transit through the hub airports grew significantly. Concerns were being raised, but the costs of improving screening and the need to process ever-larger numbers of passengers and maintain flight schedules caused most carriers to oppose tighter security measures.

The situation was changed irrevocably by the events of September 11, 2001 . The US government created the Department of Homeland Security, which established a Transportation Security Authority (TSA) to oversee the imposition of strict new security measures on the industry. Security can now account for between 20 and 30% of the operating costs of an airport. Security involves many steps, from restricting access to airport facilities, fortifying cockpits, and setting no-fly lists, to the more extensive security screening of passengers and their luggage. Screening includes restrictions on what can be personally carried in airplanes, such as gels and liquids. For foreign nationals, inspection employs biometric identification, which at present involves checking fingerprints and facial pattern recognition, but retinal scans may be implemented in the future.

A new system, the Computer Assisted Passenger Prescreening System (CAPPS II), was introduced. It required more personal information from travelers when they book their flights, which is used to provide a risk assessment of each passenger. Passengers considered to be high risk were further screened. However, this program was canceled in 2004, mostly because it created too many false positives. It was replaced by the Secure Flight program working under similar principles but is entirely managed by the TSA. From 2009, all flights originating, bound to, or flying over the United States, had their list of passengers cross-referenced by a central no-fly list managed by the TSA. To further focus on screening procedures, trusted traveler programs were introduced in which individuals who have volunteered information such as fingerprinting and background checks can undergo an expedited security procedure involving customs clearance. For instance, the Global Entry program that began in 2008 allows US citizens and permanent residents as well as citizens of 14 countries (e.g. Canada, South Korea, Netherlands, UK) who have submitted to an interview and background check to use fast processing lanes and kiosks at the majority of US ports of entry. Using kiosks has been expanded through customs, allowing passengers to have their documentation scanned and photos taken automatically, reducing processing time.

The imposition of these measures has come at a considerable cost, estimated to be more than $7.4 billion annually by IATA in 2018. A significant factor has been the screening of passengers with the hiring and training of a workforce, the purchase of improved screening machines, and the re-designing of airport security procedures. More space within transport terminals is required to handle security procedures, including inspection areas and waiting lines. Further, aircraft design and operations have been changed, including the introduction of reinforced cabin doors. These measures also impacted passenger throughput, with an estimated 5% decline attributed to security measures. Clearing security has become the most important source of delays in the passenger boarding process. Passengers are expected to arrive 2 hours before departure at the terminal to clear security. It is therefore not surprising that there has been a modal shift to the road (and to some extent rail where services are available) for air travel involving shorter distances (500 km or less). This shift has been linked with additional road fatalities, an unintended consequence of additional security measures.

Security issues have had a negative effect on the air transport industry as costs increased with delays and inconveniences to passengers increasing as well. However, these delays and inconveniences are now considered part of contemporary air travel, with passengers accustomed to security requirements. Further, airports have developed effective procedures, such as multiple security lanes and high throughput scanning, to speed up the process. The burden imposed by security and customs procedures at major ports of entry has also incited the expansion of customs pre-clearance programs .

The COVID-19 pandemic brought forward a new dimension to passenger transportation security: epidemiological security . This is particularly the case for high-density forms of passenger transportation such as public transit, cruise shipping, and air travel. During the pandemic, people were reluctant to use such modes of transportation because of the perceived risks of being infected. Further, many countries initially prevented the entry of foreign residents and later imposed mandates related to vaccination and testing to be allowed entry. Each mode can be associated with an epidemiological risk that needs to be mitigated. For air transportation, this can involve screening passengers and the ongoing disinfection of facilities such as waiting areas and planes between flights. The outcome is additional costs and a decrease in the performance of air travel because of longer turnovers.

3. Freight Security

Security in the freight industry has always been a major problem. Illegal immigrants, drug smuggling, customs duty evasion, piracy , and the deployment of sub-standard vehicles (higher propensity to accidents) have been some of the most important concerns. In light of the emergence of global supply chains , the emphasis on freight transport security is gradually shifting into a more comprehensive but complex approach. However, as in the air passenger business, the events of 9/11 highlighted a new set of security issues. The scale and scope of these problems with freight are of an even greater magnitude. The less-regulated and international dimensions of the shipping industry, in particular, have made it vulnerable to security breaches.

A large number of ports, the vast fleet of global shipping and the range of products carried in vessels, and the difficulty of detection have made the issue of security in shipping an extremely difficult one to address. For ports, vulnerabilities (unauthorized access to cargo and facilities) can be exploited from the land side as well as on the maritime side. The container, which has facilitated globalization, makes it extremely difficult to identify illicit and dangerous cargoes . In the absence of scanners that can scan the entire box, manual inspection becomes time-consuming and virtually impossible, considering the large volumes involved. Hubbing compounds the problem, as large numbers of containers are required to be handled with minimum delays and inconvenience.

In the United States, the response was to enact the Maritime Transportation and Security Act in 2002. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the essential elements of this legislation as the International Ship and Port Security Code (ISPS), which began to be implemented in 2004. There are three important features of these interventions:

- An Automated Identity System (AIS) is required for all vessels between 300 and 50,000 dwt. It requires vessels to have a permanently marked and visible identity number, and there must be a record maintained of its flag, port of registry, and address of the registered owner.

- Each port must undertake a security assessment . This involves an assessment of its assets and facilities and an assessment of the effects of damages that might be caused. The port must then evaluate the risks and identify its weaknesses in features such as physical security, communication systems, and utilities.

- All cargoes destined for the United States must receive customs clearance before the departure of the ship . Besides, biometric identification for seafarers was implemented and maintained in national databases.

The ISPS code has been implemented in ports worldwide as, without certification, a port would have difficulty trading with the United States. Securing sites, undertaking risk assessments, and monitoring ships represent additional costs without commercial return. US ports have been able to tap funding from the Department of Homeland Security, but foreign ports must comply or risk the loss of business. In 2008, legislation in the United States required that all containers being shipped to the United States undergo screening. Foreign ports were expected to purchase expensive scanning equipment and undertake to screen all US-bound containers, regardless of the degree of security threat. This is a further financial and operational complication foreign ports must contend with.

Like its passenger counterpart, the airline freight industry faces stringent security requirements. Since 2010, a TSA regulation has required screening all cargo carried by air within the United States or internationally before loading. The Certified Cargo Screening Program (CCSP) forces airlines, freight forwarders, and shippers to assume the costs of these security measures to establish a secure air freight transport chain. The measure imposed additional costs, delays, and disruptions, undermining the operational effectiveness of air cargo. Still, the air freight industry has adapted to these measures. Security has become an additional element in determining competitive advantage and part of the cost of doing business that carriers and terminal operators are contending with.

Related Topics

- 9.1 – The Nature of Transport Policy

- 9.2 – Transport Planning and Governance

- 9.4 – Transportation, Disruptions and Resilience

- B.19 – Transportation and Pandemics

Bibliography

- Federal Highway Administration (2018) Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework, 3rd Edition, FHWA-HEP-18-020.

- Gillen, D. and W.G. Morrison (2015) “Aviation Security: Costing, Pricing, Finance and Performance”, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 48, pp. 1-12.

- OECD (2011) Future Global Shock – Improving Risk Governance, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Sivak, M. and M.J. Flannagan (2004) “Consequences for Road Traffic Fatalities of the Reduction in Flying Following September 11, 2001”, Transportation Research E, Vol. 7, pp. 301-305.

- Transportation Research Board (2006) Critical Issues in Transportation, Washington, DC: The National Academies.

- World Economic Forum (2012) New Models for Addressing Supply Chain and Transport Risk.

Share this:

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Illustration of How New Technologies Influence Transportation Safety (Long Essay)

Related Papers

Fred Wegman

The transport system and transport policy. An introduction. Second edition

Fred Wegman , Paul Schepers

The number of road crashes, fatalities and injuries is considered unacceptably high in many countries. Risks in road traffic are far more higher than in other modes of transport. Road crashes are tragedies at a personal level and economic costs for society are considerable. A lot of knowledge has been gained over the years on causes of crashes and on risk factors. Our understanding of the effectiveness and efficiency of interventions to reduce risks has grown and implementation resulted in lower risks and less casualties. Fitting in a Safe System approach many promising options can further improve road safety.

International journal of environmental research and public health

Anthony Mawson

Casualties due to motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) include some 40,000 deaths each year in the United States and one million deaths worldwide. One strategy that has been recommended for improving automobile safety is to lower speed limits and enforce them with speed cameras. However, motor vehicles can be hazardous even at low speeds whereas properly protected human beings can survive high-speed crashes without injury. Emphasis on changing driver behavior as the focus for road safety improvements has been largely unsuccessful; moreover, drivers today are increasingly distracted by secondary tasks such as cell phone use and texting. Indeed, the true limiting factor in vehicular safety is the capacity of human beings to sense and process information and to make rapid decisions. Given that dramatic reductions in injuries and deaths from MVCs have occurred over the past century due to improvements in safety technology, despite increases in the number of vehicles on the road and miles driven...

Pete Thomas

Robert B Noland

Journal of Safety Research

David Sleet

Accident Analysis & Prevention

Claes Tingvall , Kalle Parkkari , Lucia Pennisi

American Journal of Preventive Medicine

Elihu Richter

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Crime and safety in transit environments: a systematic review of the English and the French literature, 1970–2020

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 31 January 2022

- Volume 14 , pages 105–153, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Vania Ceccato ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5302-1698 1 ,

- Nathan Gaudelet 2 &

- Gabin Graf 2

15k Accesses

16 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article reviews five decades of English and French literature on transit safety in several major databases, with the focus on Scopus and ScienceDirect. The review explores the nature and frequency of transit crime and passengers’ safety perceptions in transport nodes and along the trip using bibliometric analysis and a systematic review of the literature. The number of retrieved documents was 3137, and 245 were selected for in-depth analysis. Transit safety as a research area took off after the mid-1990s and peaked after the 2010s. The body of research is dominated by the English-language literature (mostly large cities), with a focus on the safety of rail-bound environments and examples of interventions to improve actual and perceived safety for public transportation (PT) users. Highlighting the importance of transit environments along the whole trip, the article also helps advocate for more inclusion of passengers’ safety needs and the involvement of multiple stakeholders in implementing PT policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Practical Challenges and New Research Frontiers for Safety and Security in Transit Environments

Studies on the impact of road freight transport and alternative modes in Australia: a literature study

Theoretical perspectives of safety and security in transit environments.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When we use public transportation (PT), we spend a part of our travel time waiting at transport nodes (train stations or bus stops) or walking on our way to them. If we feel at risk of crime or feel anxious about something unpleasant happening while in transit, there is a risk we may start avoiding PT and start looking for other travel alternatives. Therefore, feeling safe in transit environments is a fundamental need of all travelers and a guarantee for a sustainable city (UN-Habitat 2019 ).

How safe are we while in transit? Our understanding of the conditions that affect safety is growing, but the international literature lacks an updated systematic review of the research evidence. One of the first reviews in this area was carried out by Smith and Clarke ( 2000 ), followed later by Smith and Cornish ( 2006 ), then in the mid-2010s by Newton ( 2014 ), and more recently with a specific focus on gender issues by Ding et al. ( 2020 ). None of these were systematic reviews (Higgins and Green 2011 ), nor did they incorporate studies devoted to safety interventions. They also reflect scholarly material published in English only, and none performed a bibliometric analysis. We argue for the need of a systematic review of the literature on transit crime and safety. Therefore, in this article we collect and systematize scholarly knowledge on the topic covering five decades of studies, written in English primarily but extending also to the French literature as a benchmark. Although this is not the first literature review on transit safety in English or in French (e.g., Bradet and Normandeau 1987 ; Crossonneau 2003 ; Noble 2015a , b ), this article is the first that covers studies dealing with transit crime (various types) as well as safety perceptions of transit environments, providing:

A special focus on studies that deal with the transit environment (stations and bus stops as well as the last-mile mobility and/or safety door-to-door, the so-called “whole journey perspective”). We still can agree with Smith and Clarke ( 2000 ) who suggest there is a lack of understanding of “how the conditions favoring crime on public transport arise and why they persist. We have limited knowledge of the mix of forces and constraints—political, geographical, economic, engineering, and others—which have combined to shape and form modern public transport.”

Extra attention to studies devoted to safety according to “users’ perspectives” and safety needs. The temporal dimension of these studies is also an interesting feature that has been highlighted in this review but was not pointed out in previous reviews.

Lessons from different research traditions, from English and French, with as many perspectives on the topic as possible. The French literature has been chosen because of the long tradition of research on public transportation and also because French is the fifth most common world language, spoken on nearly every continent, providing therefore a good international overview of this field of research.

1.1 Definitions and delimitation

Transit safety is about safety conditions experienced and perceived by public transportation (PT) users along their trip. This may involve PT travelers’ risk of being victimized by crime or feeling unsafe at a particular place (e.g. a station) or in a combination of environments, situations and contexts. For example, Smith and Clarke ( 2000 ) indicate that crime can occur when a PT traveler is walking from home to a bus stop, or it may occur from or between transportation nodes; it is when the traveler is exposed to environments that are more or less criminogenic. Similarly, safety perceptions may vary along and within these environments. When the PT traveler is waiting for transportation or is on the move between different sections of stations (e.g. on the metro station platform or walking from the ticket area to the platform). Third, when the PT traveler is on board a mode of transport (see e.g. Newton 2004 ).

Transit crime includes offenses and/or safety-disturbing behaviors against PT users, personnel, and property. Moreover, crime targets vary and can include the system itself (e.g. vandalism and fare evasion), employees (e.g. assaults on ticket collectors or guards), and PT users (e.g. pickpocketing or assault). These offences and/or safety-disturbing behaviors may not in a strict sense be a “crime” but they affect PT users’ safety perceptions, such as shouting or what Moore ( 2011 ) calls “low-level behavior,” ranging from groups of young people behaving boisterously to people talking loudly on mobile phones on trains or buses.

Safety perceptions is used here as an umbrella term for fear of crime and other anxieties that are expressed by PT users along the trip and can vary over time. How individuals perceive transit environments depends on their individual characteristics (age, gender, previous victimization) and the features and contexts of these transit environments (transport mode, type of transport node—bus stop or station—and quality of the environments they spend time in, from their home to a transport node).

For the purposes of this article, we adopted the term public transportation (PT) to capture what North American readers may think of as “public transit,” “mass transit,” “rapid transit,” or just “public transport” systems. Note that we use the terms “PT users,” “PT travelers,” “PT riders,” and “PT passengers” interchangeably. As suggested by Newton ( 2014 ), there is no clear consensus of a definition of public transport. PT refers here to “a system used by the public, often a means of transporting passengers in mass numbers, generally a for-hire system that occurs across a fixed route or line,” consisting of a range of transport modes, including rail-bound (railroads, light rail, metro/subway/underground railway, high-speed rail, and intercity rail), buses, trolleybuses, and trams. We limit this literature review to PT only, excluding taxis and Uber services that may be connected to PT. We exclude also studies devoted to events of accidents and suicides and focus instead on crime and safety perceptions only. This perspective includes studies focused on safety during the trip on buses and rail-bound modes, at transport nodes, such as bus stops and stations, and/or on the way to them.

1.2 Research questions

The study is based on materials from an open search from several databases (Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google scholar) which were later split into two parts (a bibliometric analysis and an in-depth analysis of materials both in English and French from 1970). We used the software VOSviewer ( https://www.vosviewer.com ) to organize and visualize the vast material spanning five decades. This literature review aims to respond to the following questions:

When and where have most studies on transit safety been published?

Which are the main research domains in transit safety?

What are the most common characteristics of transit research in English and French?

What is the nature and extent of crime in transit environments?

How do temporal, environmental, and other contextual factors influence transit safety?

How do the physical and social characteristics of transit environments affect safety perceptions of PT travelers?

How does safety vary by different types of PT users?

How does technology affect safety in transit environments?

Which are the safety interventions used to tackle safety problems in transit environments?

Which are the recommendations for future research and practice?

This study is composed of six parts. First, we briefly present the methodology, then we report the results by answering the above questions. In the final section, we identify gaps in the literature and suggest a research agenda as well as policy implications of the current knowledge.

2 Methodology

We used two complementary methods: (1) one was the systematic review using Scopus, Science Direct and Google Scholar database (in French) and (2) the other was a list of publication from the Transit crime network.

We conducted a comprehensive search for academic publications (focus was on articles but a bit over 30% were other relevant publications, such as reports and conference papers). We used a variety of bibliographic databases, Scopus and ScienceDirect in particular because they are reliable sources of internationally published research in English language (note that duplets were excluded). In French, because the literature in this area is composed of a mixture of articles and reports distributed in different databases, we used Google Scholar as a search engine to capture multiple sources (Cairn.info, Erudit, Persée, Hal, etc.). A list of keywords used during this process is shown in “ Appendix ” Table 3 .

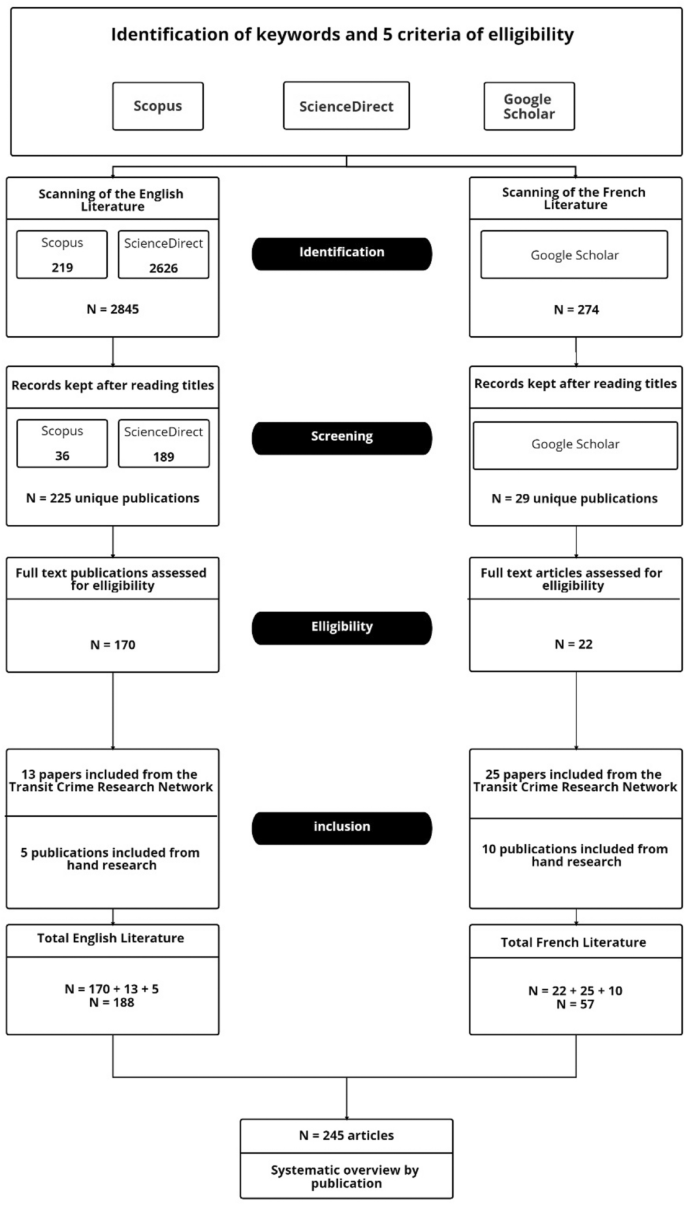

In addition, the literature review used a pre-selected list publication from transit safety researchers provided by a user list Transit crime network ( https://maillist.sys.kth.se/mailman/listinfo/abe.kth.se_tcr-network ). This sample of references is a convenient sample based on the contributions of experts that actively participate in a forum that discusses transit safety. Although the decision of including the literature in a specialized research forum such as this user list might have created a bias in the sample since many members were experts in the area, we believe that the benefits outweigh the problems. Eventually, we included a few articles by hand during the finalizing process to include newly published articles, resulting in 3137 publications (Fig. 1 ).

The methodological steps to perform the literature search based on five criteria of selection

From these 3137 publications, 245 were selected (Fig. 1 ), first eliminating duplicates and later excluding those that were not relevant. We adopted the systematic review protocol of type PRISMA-P 2015 (Moher et al. 2015 ) to support inclusion based on five criteria of importance:

Studies aiming at explaining the link between the transit environment, the perceived safety of riders, and the actual crime occurrences in PT. By “transit environment” we mean the design (e.g. size and layout of platform, lighting, visibility), the technology (e.g. CCTV, apps, RTI), the users (flow, crowdedness), the personnel (e.g. patrols), and the immediate context of the PT node (safety door-to-door).

Studies should preferably show temporal patterns of crime and users’ safety perceptions (hours, days, and seasons).

Studies that distinguish safety perception and victimization in transit by individual and socio-demographic characteristics, in particular by gender but also by age, ethnic background, disabilities, and socio-economic status. Studies that analyze fear of crime in transit from the user’s perspective.

Studies with a focus on crime prevention initiatives. Studies that show qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the impacts of programs or environmental changes that tackle crime and/or perceived safety and/or crime rates in PT.

Studies that provide perspectives on the topic that are as varied as possible, in different contexts. We cover therefore publications from 1970 to 2020, in English and in French. Because there is less material in French and a large part consists of reports resulting from surveys (often having a looser structure compared to English-language journal articles). We made the criteria 1–4 more flexible. For instance, we accepted reports from the French Ministry of Transport that were relevant to the topic (e.g. Barjonet et al. 2011 ).

2.1 Bibliometric analysis

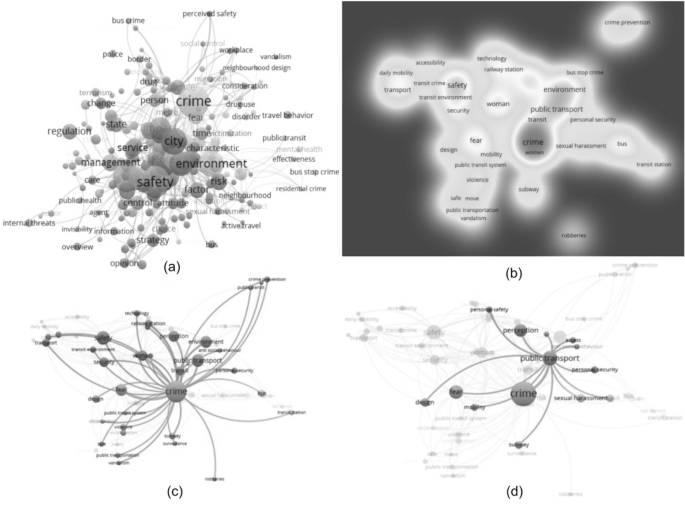

The bibliometric analysis included all English-language articles obtained through the user list and in the data collection process in *.ris (Scopus, Sciencedirect and the TCR network; the French publications were too few to produce meaningful visualization on their own). We used VOSviewer version 1.6.12 ( https://www.vosviewer.com ) to create bibliometric maps based on the terms cited in the titles of each article and to group the terms in clusters according to their linkages. With these clusters, we were able to visualize several topics. The co-occurrence analysis was performed using the terms in titles adopting the full counting method. For VOSviewer mapping of most frequent terms in titles, a minimum occurrence of two was used as a cutoff point for inclusion of the terms in mapping analysis. From a total of 675 terms, only 106 met the threshold of the minimum number of two occurrences/repetitions. This criterion of a minimum of two repetitions was selected to avoid terms without links or with weak links to the topic and at the same time to ensure the coverage of the terms and representativeness of the articles. The final selection resulted in 62 items out of the 106 keywords. We did not apply any filter based on the software “score relevance.” Instead, we selected the relevant terms ourselves to fit our subject. The map of words was created using a minimum cluster size of 10 to maximize the readability of the map; the rest of the parameters were the default ones. Output files from the database were used to produce informative network maps by topic and a heat map showing the frequency of keywords indicating potential research domains. An example of each is discussed in the section “ Findings .”

2.2 In-depth analysis

The bibliometric analysis supports the selection of “research domains” that are discussed in detail. The in-depth analysis was guided by our research questions, namely our interest in knowing about studies on the nature and extent of crime in transit environments, the temporal, spatial, and other factors influencing these crimes, and the potential impact of physical and social environments on safety perceptions of travelers. We also investigated using the literature review to determine whether and how safety perceptions vary by different types of users as well as how technology affects safety in transit environments. In addition, we collected literature about safety door-to-door as well as the types of strategies and interventions that are used to reduce crimes and improve perceived safety in transit environments. From the initial 245, about two thirds are discussed in detail in a set of tables and appendices referenced in the next section.

3.1 Bibliometric analysis

3.1.1 number and types of retrieved documents.

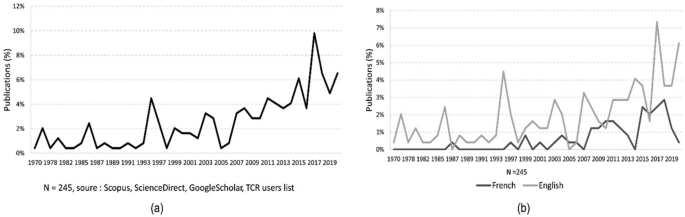

From 245 eligible publications that constitute the base for the analysis, 70% are articles and the remainder are reports, chapters, and conference papers; 77% are in English, and 23% in French. Figure 2 a shows the annual share of total publications on transit safety (N = 245). The same is shown in Fig. 2 b but divided by language.

Annual share of total publications on transit safety, 1970–2020 in percentage, a Total and b by language. Source: Selection from Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, TCR users list (in percentage). Up to June 2020 only

3.1.2 Evolution of the field over time

The earliest publication within the defined time period was written by the National Technical Information Service (SRI - Stanford Research Institute 1970 ). This study discussed the nature and causes of robbery and assault of bus drivers and suggested solutions. One of the most recent articles was published by Jun et al. ( 2020 ) and was devoted to the gap between users’ needs and the practitioners’ prioritization of accessibility features. A focus on users’ perspectives on safety, particularly on women’s safety, became more common in the last decade. From 1970 to 2010, the number of publications grew slowly, but note that 56% of publications (131) came out in the last 10 years, 37% of the total in the last 5 years (86 publications). The maximum number of publications was recorded in 2017. In addition, 24 papers were published in 2017, and a double special issue in “Crime Prevention and Community Safety” on this theme contributed to almost half of these publications.

The literature is dominated by the English literature. While publications in English are characterized by academic articles published in peer-reviewed journals, the French publications are often reports directed at security professionals, organizations, and practitioners. Therefore, it is no surprise that the French documents follow a looser structure than the English publications do. The target of publications in French is mostly the transit system in France (38 publications), while four reports focus on Canada (Montréal only) and two focus on Belgium. The remainder is about different transit systems in cities around the world.

In terms of content, there are differences between the English and French literature. While the English-language literature has focused more on the causalities between transit environments and crime, the French literature has a more sociological/psychological nature, focusing on travelers’ surveys and users’ behaviors and perspectives on safety (e.g. Barjonet et al. 2010 ; Noble 2015a , b ; Wilow 2015 ; Vanier and D'arbois 2018a ). Examples of the French literature include the seminal work of Bradet and Normandeau ( 1987 ) and one of the latest by Noble and Fussy ( 2020 ) on feelings of insecurity in public transit. A few deal with issues of safety and governance, including the interplay between public and private sectors (Malochet 2015 ; Castagnino 2016 ; Hamelin 2010 ; Bonnet 2008 , 2006 ). Reports written in French are mostly about safety perceptions, with a strong focus on sexual crimes and sexual harassment in PT (e.g. d’Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier 2017 ; HCEEFH 2015 ; Debrincat et al. 2016 ; Colard 2018 ; Alessandrin et al. 2016 ).

3.1.3 Most active countries

Most publications are based on examples from the United States (Table 1 ), with nearly twice as many as in France, followed by the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Canada. However, the United Kingdom is in second position if we exclude reports and count the number of published articles only. More recently, the literature has been expanded by contributions from Latin America (Brazil, Colombia, Mexico), Australia, India, Norway, Malaysia, Japan, and Hong Kong, with more than three publications each (e.g. Shibata et al. 2014 ; Javier and Ceccato 2020 ; Otu and Agugua 2020 ; Chowdhury and van Wee 2020 ; Fillone and Mateo-Babiano 2018 ).

3.1.4 Publications by type of geographical area

Public transit systems such as metro, commuting trains, and bus lines in global and capital cities are often the focus of transit safety studies (44% of all publications). Cities such as New York, London, Paris, Tokyo, Los Angeles, Sao Paulo, New Delhi, and Santiago belong to this group. Next, studies that are devoted to an entire country, such as the United Kingdom, United States, France, and Sweden, account for 28% of the publications, followed by transportation systems in cities, such as Liverpool, Lucknow, Manchester, Lyon, and Milan. Thus, 6% of the papers focus on other areas and 10% do not specify the location of their study.

3.1.5 Visualization of author keywords

The visualization map of author keywords from the English literature shows that “crime,” “safety,” “public transport,” “environment,” “fear,” and “transit” were the most frequently encountered keywords (Fig. 3 a). These maps show how keywords in the papers’ titles are linked to each other and their occurrences in our sample. The maps are divided into four clusters, which show families of terms based on their co-occurrences in titles. In the density visualization (Fig. 3 b) the strength of each keyword is shown in different shades. The words “crime” and “public transport” are linked to many other keywords and have many occurrences.

a Network visualization map of words contained in the titles of the English publications, b Density visualization map and c Network visualization map for the English selected publications (N = 188), centered in the words “crime” ( c ) and “public transport” ( d )

Note that “crime,” “public transport,” “environment,” “fear,” “safety,” “crime prevention,” “bus,” and “women/woman” are recurrent terms in these publications; in particular, the word “crime” constitutes the major hotspot. The keywords “women/woman” signal a growing literature on sexual transit crime, a safety problem that is largely underreported (e.g. Ding et al. 2020 ; Solymosi and Newton 2018 ; Newton et al. 2020 ; Priya Uteng et al. 2019 ; Chowdhury and van Wee 2020 ; Jun et al. 2020 ; Whitzman et al. 2020 ; Dunckel-Graglia 2013 , 2016 ; Natarajan 2016 ; Moreira and Ceccato 2020 ). These keywords in the titles are also represented when the network visualization map is created for the selected English publications (N = 188), centered on the words “crime” (Fig. 3 c) and “public transport” (Fig. 3 d). In the next section, we discuss the interconnections between these terms as research domains.

3.1.6 The nature of studies in transit environments

Based on a title search of 245 articles, we found that 81 (33%) publications were about crime, 29 (12%) were about fear and/or safety perceptions, 129 (53%) both crime and safety perceptions, 6 on other topics (2%).

Among those articles that were devoted to the analysis of crime, 70% focused on violence, 18% on property crimes with aggravated violence, such as robberies, 2% on property crimes only, and 10% on vandalism and other types of crime. Vandalism is often associated with the analysis of other crimes (either violent or property crimes), rarely studied by itself. Studies that are devoted to violent crimes, assaults of all types, such as fights and attacks, are common, followed by gendered and sexual crimes and terrorism, which are a minority. With regards to transport mode, as many as 76% (188) of the publications deal with rail-bound PT; of these, about half relate to trains and the other half the metro. About 65% are related to buses, while 8% (22) of these focus on other types of transportation, such as ride-hailing services “Tourist Vehicle with Driver” (Weber 2019 ) or Vikram transports in India (Tripathi et al. 2017 ). In other words, many publications deal with both buses and rail-bound modes.

3.1.7 The types of methods

Quantitative analyses (descriptive or confirmatory statistical analyses) are used in 63% (155) of all 245 publications, 19% (47) are qualitative publications, and 18% (43) used mixed methods. Among the quantitative analyses, the majority used descriptive statistics, such as frequency analysis of crimes and/or perceived safety, cross-tables, and different types of regression models. These publications are often in English and intend to assess the impact of traveling conditions of one or more aspects of the environment on crime and/or safety. As many as 17% (33) of these quantitative publications use regression models. Among them, half (17) were classical multivariate linear regressions and half (15) were logistic regressions (nine binomial, three multinomial, and three ordinal). Publications using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and interstitial analyses have appeared at the end of the twentieth century and represent 12% (25 out of 198) of quantitative papers. None of them are from the French literature. These methods are useful to study certain aspects of transit safety and crime, such as socio-economic characteristics (e.g. Buckley 1996 ; Sung-suk 2009 ) and transit surroundings (e.g. Liggett et al. 2001 ; Newton et al. 2014b ). Out of 47 qualitative publications, half were in French. These findings show the dominance of qualitative analyses in the French literature, while the English publications are denominated by more quantitative approaches. Exceptions are publications in French from Canada that follow an Anglo-Saxon tradition of taking a more quantitative approach to analyze transit safety (Grandmaison and Tremblay 1997 ; Ouimet and Tremblay 2001 ; Browne 2010 ). The studies based on mixed methods are varied in nature and often aim at producing results relevant for practice; see for instance Newton et al. ( 2004 ).

3.2 In-depth analysis by research domains

3.2.1 the temporal patterns of crime and perceived safety.

The flow of passengers both at peak and off-peak times create the necessary conditions for crime, namely the presence of a possible motivated offender, a desirable target, and a lack of people ready to intervene if anything happens (Cohen and Felson 1979 ). This temporal dimension has been recognized by the international literature as key to understanding safety conditions in transit environments. Of the total publications, 22% investigate one or several dimensions of the temporal variations of crime and/or safety perceptions in transit environments. Nearly all publications refer to hourly patterns of crime and/or perceived safety, often differences between peak and off-peak hours. These “time windows” are important for transit safety conditions because crowded environments tend to attract certain types of offenses, such as pickpocketing (Zahnow and Corcoran 2019 ; Ceccato et al. 2015 ), while empty stations or bus stops tend to promote crimes that demand anonymity, such as robbery. “ Appendix ” Table 4 summarizes findings from these studies split into different time windows.

Studies show that morning peak hours attract robberies (Block and Davis 1996 ; Newton et al. 2014b ), assaults, thefts, public disorder (Stringer 2007 ; Ceccato 2018 ), and sexual crimes (Ceccato and Paz 2017 ), while Smith ( 1986 ) finds fewer crimes in the early morning hours. Research suggests that people feel unsafe during morning rush hours, especially women (Mitra-Sarkar and Partheeban 2011 ), which is when sexual crimes can take place (Ceccato et al. 2011 , 2017 ). As exemplified by Vanier and D'arbois ( 2018b ), seven articles deal with peak hours in the mornings, a time that is both “anxiety-inducing” and criminogenic. However, almost half of the papers focusing on the nighttime describe it as the time of day when most people feel the least safe, especially women (e.g. Austin 1984 ; d’Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier 2017 ). This feeling is stronger when travelers have to wait for transportation (Chowdhury and van Wee 2020 ; Mahmoud and Currie 2010 ), or when the location is associated with a particular land use, such as being near nightclubs (Gosselin 2012 ). Fear may reflect the risk of different crimes. For instance, violent crimes are said to be prevalent after rush hour, after 6:00 pm (Moreira and Ceccato 2020 ; Newton 2014 ), while robberies seem to occur more often late at night than in the early evening (Block and Davis 1996 ; Chaiken et al. 1974 ; Clarke et al. 1996 ).

Among the publications that deal with the temporal dimension of crime or perceived safety in transit environments, 43% made a distinction between crime occurring on weekdays or on weekends. Seven of these (30%) suggest that more crimes occur on weekends (e.g. Ceccato et al. 2011 , 2017 ). The end of the week (Thursday to Saturday) witnesses increases in robbery (Newton 2018a ). Finally, one article (Smith 1986 ) suggests that maybe there are fewer crimes during weekends in absolute numbers but, after the author compares the number of crimes with the number of travelers, crime rates are actually higher. In addition, despite the fact that Monday is posited as a low-crime day (TCRP 2001 ; Capasso da Silva and Rodrigues da Silva 2020 ), 22% of the publications suggest that most crimes happened on a weekday, especially on Wednesday (e.g. Chaiken et al. 1974 ; Le Grâet and Vanier 2016 ). There are indications that lack of surveillance and fewer patrols affect crime during weekends (Ouimet and Tremblay 2001 ). Also, trains are less frequent on weekends, the density of passengers decreases and waiting times increase, affecting safety perceptions (Yavuz and Welch 2010 ; Mahmoud and Currie 2010 ). Weekends tend to be perceived as unsafe, especially by women (Vanier and d’Arbois 2017 ). “ Appendix ” Table 4 summarizes the remaining time windows.

3.2.2 The influence of environment on transit safety

According to Smith and Clarke ( 2000 ) “crimes cannot be properly explained, nor effectively prevented, without a thorough understanding of the environments in which they occur. Nowhere is this more apparent than in urban public transport.” (page 169). Transit environments can be planned in a way that reduces the possibility of crime occurring, by stimulating surveillance, fostering territoriality, and reducing areas of conflict by controlling access and improving overall perceived safety. These principles are based on what is called Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) and on situational crime prevention theory (Clarke 1983 ) that, among other things, seek to enhance natural surveillance through planning and modifying the environment. CPTED asserts “that the physical environment can encourage or discourage opportunities for crime by its very design and management” (Cozens et al., 2003a , b , c ). Research shows that crime and safety in transit environments depend on the physical and social environmental attributes at the transport node, either bus stops or train/subway stations, the characteristics of the immediate environment and neighborhood, and the relative position of both the station and neighborhood in the city (Loukaitou-Sideris et al. 2001 ; Ceccato 2013 ). Yet, how do the physical and the social characteristics of transit environments affect safety perceptions of PT travelers? Below we discuss the importance of the quality of transit environments, in particular, design, layout, obstacles and hiding spots that affect visibility and surveillance; maintenance and lighting conditions, CCTV cameras; the presence and flow of passengers over time, specially crowdedness, and the quality of immediate areas.

3.2.2.1 Visibility, obstacles and hiding spots

Elements of the station, such as elevators, pillars or facilities should not hinder visibility for PT users. Instead, elevators with large glass side panels should be endorsed (La Vigne 1996 ). Similarly, columns no wider than necessary, glassed internal walls and ticketing in one central location in the station (Felson et al. 1996 ) should be encouraged. In an underground station with long corridors, often with sharp corners and restricted sight lines, a solution is the establishment of corner convex mirrors that increase visibility and natural surveillance (Crime-Concern 2004 ; Felson et al. 1996 ). Moreover, it is important to ensure visibility from any point in a station (Umaña-Barrios and Gil 2017 ; Mohamed and Stanek 2020 ); high-domed and/or white ceilings in the station are encouraged (e.g.: Felson et al. 1996 ; Sham et al. 2013 ) as is avoiding spiral ramps (Atkins 1990 ). Moreover, the design of bus stops is important. Transparent bus shelters are recommended by seven articles (27%) focusing on buses and bus stops. They insist on the avoidance of enclosed brick shelters; indeed, the lack of visibility is an opportunity for offenders to commit crimes (Noble 2015a ; Sham et al. 2013 ). Moreover, curved shelter structures can be a solution that gives the feeling of an open and secure space for users (Diec et al. 2010 ). Finally, bus stops should be located in front of a place that provides natural visibility (Liggett et al. 2001 ). Regarding the interior of the buses, large, transparent windows are encouraged, while dark-tinted windows reduce visibility from the outside during daylight and should be avoided (Levine and Wachs 1985 ). Thus, the same article suggests that seats in the back could be arranged in a circular pattern to allow better visibility between passengers and to cut down on pickpockets. Overall, the internal design of the bus should maximize clear sight lines and visibility for both driver and passengers (Sham et al. 2013 ).

The external and internal design of the stations are essential elements that can promote visibility and opportunities for surveillance. Uittenbogaard ( 2015 ) suggests that visibility as the possibilities (promoted by the environment) a person has for observing others or situations while surveillance , in contrast, relates to the possibilities for others to observe a person, an object or a place. It can also be carried out by CCTV cameras or involving a diverse array of agents in a train station, for example: from police, security guards, safety hosts to drivers, shop owners, passengers and residents. More recently, with the wide use of cameras in mobile phones, ‘surveillance’ (‘eye-in-the-sky’ watching from above) gives room to the process of ‘sousveillance’ which denotes bringing the camera or other means of observation down to a human level (Ceccato 2019 ).

Impaired visibility is clearly associated with fear of crime (e.g.: Cozens et al. 2003b , 2004 ; Ceccato and Paz 2017 ). Having control of where others are, the capacity to see and be seen by others, increases the confidence of travelers (Umaña-Barrios and Gil 2017 ). When passengers feel isolated, they feel themselves becoming an easy target for criminals (Noble 2015b ; Buckley 1996 ). Research shows that underpass platforms are often related to higher rates of disorder and crime (e.g. Ceccato 2013a ; Loukaitou-Sideris et al. 2002 ). However, the literature shows unexpected findings when vandalism is often associated with increased visibility, perhaps because it reflects the size of passenger flows (Ceccato and Uittenbogaard 2013 ). Ten articles (45%) raise the question of visibility inside stations. These focus on the importance of a wide-open design, which straightening sight lines provides, and avoiding obscured areas, corners, hiding spots, and enclosed spaces (e.g. CEMT 2003 ; Ceccato et al. 2011 ). In addition, plants should not become obstacles and impede the field of view (Mohamed and Stanek 2020 ; Crime-Concern 2004 ; Diec et al. 2010 ).

3.2.2.2 Management and maintenance