CURATE YOUR FUTURE

My weekly newsletter “Financialicious” will help you do it.

In This Post:

How to write a lead: 9 ways to nail your opening.

The lead, also spelled lede, is the all-important opening of your article. Here’s what to know.

The lead can refer to an opening section, paragraph, or sentence of a written piece.

I enrolled in night school at UCLA because I wanted to develop my skills with something other than an online course. I’m a little burnt out on online courses and the funnels that sell them. I’ve been buying courses for eight years and not finishing them for nine. And I felt ready to learn from more seasoned experts — professors and editors who had decades of experience under their belts.

The UCLA night school building sits on the edge of campus in Westwood, about half a mile from the intersection of Sepulveda and Santa Monica boulevards. When I showed up to class, I sat alongside a dozen other adults ranging in age from 19 to 65 as our teacher handed out the first writing exercise.

“This is the most important skill you will learn in journalism school,” he said.

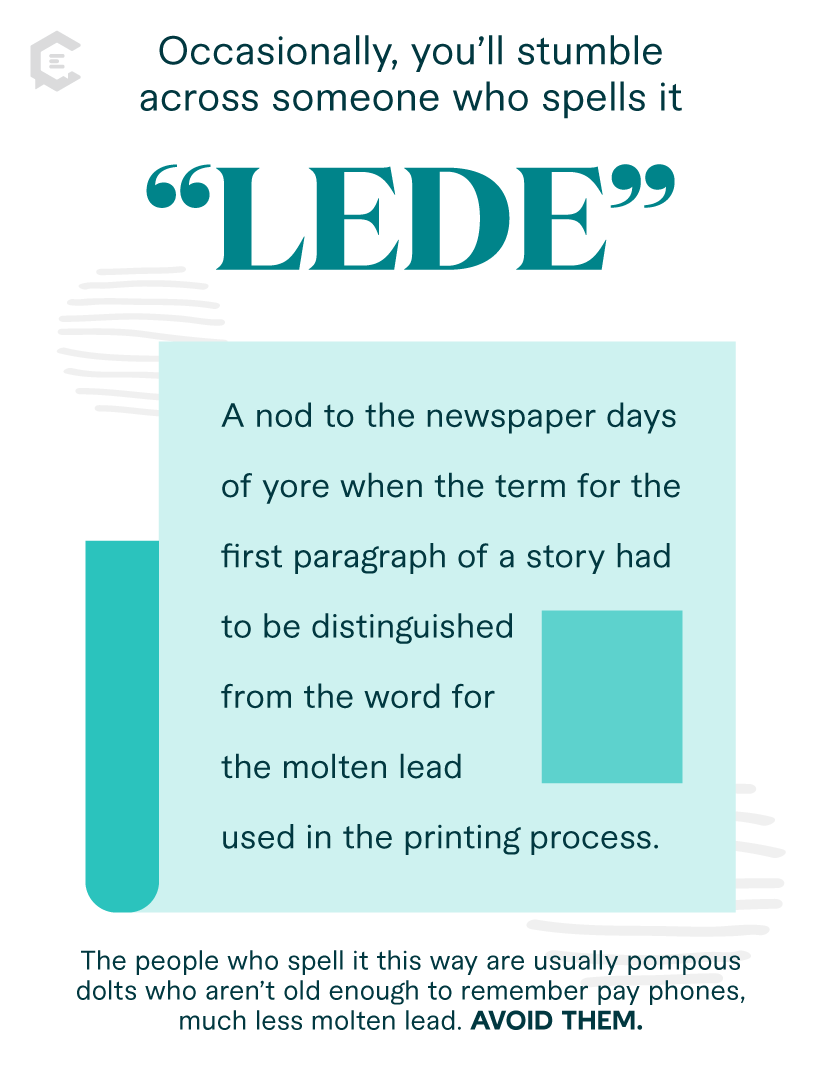

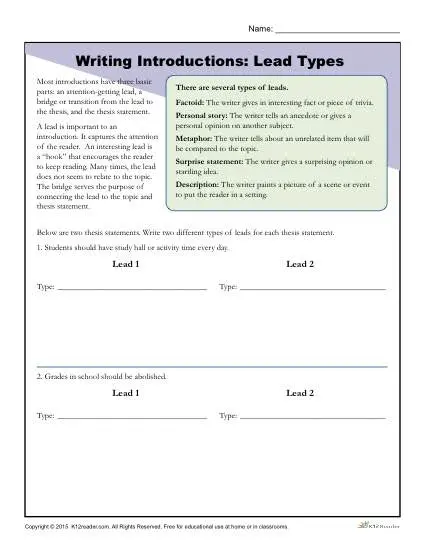

The assignment was to write a lead. Sometimes misspelled “lede” for journalism shorthand, a lead is a single sentence, paragraph, or section that summarizes the who, what, where, when, why, and how of your story.

Think of leads as being like movie trailers. You get a sense of what the movie is about, yet the teaser leaves you wanting more. There are also many variations on the lead — there is something for everyone.

Headlines are vital for successful content marketing , but to keep readers or viewers intrigued, you need a great lead, too. Here’s how this classic journalism technique can help you reach your goals.

Table of Contents

What is a lead (lede), types of leads for writing online, how to write a lead: best practices to consider, when should you write the lead for your news story, practice writing great leads today.

Before delving into the intricacies of a lead, it’s crucial to understand its purpose.

The lead is the opening paragraph or sentence of an article, designed to capture readers’ attention and entice them to continue reading. A well-crafted lead sets the tone for the rest of your writing and serves as a guide for the reader, highlighting the main points and generating curiosity.

In news, a lede serves readers by communicating what they need to know about current events. Marketers can benefit from this skill, too.

A lede will help you do the following:

- Reduce bounce rate. Readers will be less likely to dip out after just a few seconds, and may explore other pages on your website.

- Increase time on page. The longer readers stay on a page, the better it is for SEO. Time on page is a common quality metric in corporate media.

- Feed your sales funnel. Ledes aren’t just for articles; their logic applies to video scripts and sales pages, too. If readers hang around, you’re doing something right.

(For clarity, this definition of lead is different than a marketing lead — someone who has entered your sales funnel — and is distinct from the word lead as other parts of speech, such as “lead me to the nearest food truck, please.” 🌮)

Although there’s no one correct way to write a lead, some approaches are better than others based on the type of article. Journalists learn a core set of leads in year one to attract and engage readers. Here are nine different lead styles to know about.

Limited-Time Offer: ‘Pitching Publications 101’ Workshop

Get the ‘Pitching Publications 101’ Workshop and two other resources as part of the Camp Wordsmith® Sneak Peek Bundle , a small-bite preview of my company's flagship publishing program. Offer expires one hour from reveal.

- Summary lead / straight news lead.

- Single-item lead.

- Anecdotal lead / analogous lead.

- Delayed identification lead.

- Scene-setting lead.

- Short sentence lead / zinger lead.

- First-person lead.

- Observational lead.

- Question lead.

@nickwolny1 Amazon/iRobot Deal Called Off Due to Regulation - Jan. 29, 2023: Amazon will pay a $94 million termination fee to abandon its purchase of Roomba maker iRobot. Was this the right move? Here’s what to know. In 2022, Amazon announced they were acquiring iRobot, maker of the Roomba vacuum and other products, for $1.7 billion. But since then, the deal has been mired by antitrust regulators in the EU, who are blocking the deal on grounds that it gives Amazon too much marketplace control, as they could delist or degrade access to competitors. Antitrust regulators ensure mergers and acquisitions don’t result in monopolies. Market competition keeps product prices down, which is better for consumers. In response, iRobot announced today they would lay off 31% of staff, about 350 employees. iRobot made $891 million in revenue in 2023, but ended at around a $275 million loss. In a joint statement, Amazon and iRobot said there was “no path to regulatory approval for the deal.” Should Amazon have been able to acquire iRobot? #news #journalist #journalism #amazon #smarthome #newsanchor #technews #regulation #europeanunion #vacuum #acquisition #layoffs ♬ original sound - Nick Wolny | News Journalist

In this TikTok, I use a lead sentence to get the point across quickly.

No. 1: Summary Lead / Straight News Lead

Of all the types of leads summary lead is the most common. It’s very popular when writing about hard news or breaking news, and if you’re new to writing, you can’t go wrong with a summary lead. This approach is also called a news lead or a direct lead.

Hannah Block, international news editor for National Public Radio (NPR), describes it well: “Just the facts, please, and even better if interesting details and context are packed in.”

The summary lead formula is simple: aspire to communicate most of the who, what, where, when, why, and how of your story (referred to hereafter as “the W’s”) in a single sentence.

This approach is preferred in news writing, which aspires to remain neutral and unbiased in its delivery of information, and creates immediate clarity. Prioritize active voice, journalistic writing, and proper AP style in a summary lead.

Here is an example from the Associated Press (AP).

“Intensifying its fight against high inflation, the Federal Reserve raised its key interest rate by a substantial three-quarters of a point for a third straight time and signaled more large rate hikes to come — an aggressive pace that will heighten the risk of an eventual recession.” ( 1 )

AP’s business section has a “business highlights” subsection in which each article is a collection of leads and summary paragraphs. Read through it to get a feel for how to create clarity and context in a single paragraph that includes the most important information. AP News is free to read.

Here’s another example from Reuters:

“The Philadelphia Phillies ended their long wait for a World Series title with a short burst of baseball last night as they clinched the crown by completing a rain-suspended 4-3 win over the Tampa Bay Rays.” ( 2 )

No. 2: Single-Item Lead

The single-item lead is similar to the summary lead, but this approach focuses just one or two of the W’s, rather than trying to stuff most or all of them into a single sentence.

This approach is good if your news story or article is very much driven by one particular detail or feeling, and since it’s shorter, it usually results in a bigger punch. Aim to land your idea in as few words as possible, preferably all in one sentence.

Let's rewrite the previous Reuters lead to demonstrate how it could be expressed as a single-item lead instead.

“The Philadelphia Phillies are World Champions again.”

No. 3: Anecdotal Lead / Analogy Lead

If the information you’re introducing to your audience is complex or overly conceptual, a more effective approach might be to use an analogy or anecdote instead.

The anecdotal lead is unique in that it does not communicate the W’s of the story, but rather leans on details or analogies to help the reader infer what the story is going to be about. The result is a more emotionally charged or stylistic lead that goes beyond hard facts and can pull readers in.

Pro Tip : An anecdote is any short story that illustrates a point.

These leads can use an overt analogy or be more descriptive. Here are examples of each.

The Cincinnati Post

“From Dan Ralescu’s sun-warmed beach chair in Thailand, the Indian Ocean began to look, oddly, not so much like waves but bread dough.”

ProPublica/The New York Times

“"I tucked Joel in, but I feel so guilty I didn’t hold him longer,” Julie Rea said, her voice welling with emotion. That is all she can muster about the worst night of her life. As she tries to say more, she breaks down." ( 3 )

Resist the urge to use an anecdotal lead that is too cheesy or cliché. The objective of this lead is to use an anecdote to create depth and intrigue.

No. 4: Delayed Identification Lead

This lead focuses on an action or situation without revealing who is involved at first. It is good to use when someone wants to emphasize a scenario or situation effectively before revealing the W’s. When done well, it pulls people in.

In the first debate for the United States Democratic Primary in 2020, Kamala Harris used a delayed-identification lead in one of her talking points on busing legislation to great effect.

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate their public schools, and she was bused to school every day. That little girl was me.”

No. 5: Scene-Setting Lead

The scene-setting lead creates depth and detail. It is more lush and narrative, and is great for creating vividness or setting the stage for longer pieces.

Usually, the primary intention of the lead is to establish clarity quickly, but in literary journalism and other more longform approaches, taking the time to set the stage at the beginning often results in a more effective piece.

Here is an example of a scene-setting lead from BuzzFeed.

“For seven years before the murder, Dee Dee and Gypsy Rose Blancharde lived in a small pink bungalow on West Volunteer Way in Springfield, Missouri. Their neighbors liked them. “'Sweet' is the word I’d use,” a former friend of Dee Dee’s told me not too long ago. Once you met them, people said, they were impossible to forget.” ( 4 )

Here is another example, a sentence from the book Beloved by Toni Morrison.

“Winter in Ohio was especially rough if you had an appetite for color. Sky provided the only drama, and counting on a Cincinnati horizon for life’s principal joy was reckless indeed.”

No. 6: Short Sentence Lead / Zinger Lead

This type of lead is when you pack a punch with the first sentence of your article to capture a reader’s attention. It can be sassy, shocking, unexpected, compelling, or all of the above.

Usually, when using a zinger lead, the following paragraphs fill in missing details and function like a regular lead.

Here is a sassy example from the Philadelphia Enquirer.

“Philadelphians don’t need anyone’s approval, especially not New Yorkers. But that doesn’t mean we don’t care when we get recognition.” ( 5 )

Here is another example from the Miami Herald. This was a story about a man who attempted to smuggle cocaine by swallowing balloons of it.

“His last meal was worth $30,000 and it killed him.” ( 6 )

No. 7: First-Person Lead

A first-person lead is the battle ax of many a mom blogger or aspiring opinion columnist. First-person leads are fine for blogging, and they’ve become increasingly popular in our social media-first culture.

However, they also break the fourth wall; if you’re writing a journalistic article or reporting, introducing yourself as a character in your story may be a risk.

Remember, the main goal of a lead is to get a point across quickly. If your personal experience doesn’t contribute to that goal, readers won’t understand what they’re reading, and they’ll check out.

Here is an example from a story by National Public Radio (NPR).

“For many of us, Sept. 11, 2001, is one of those touchstone dates — we remember exactly where we were when we heard that the planes hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. I was in Afghanistan.” ( 7 )

No. 8: Observational Lead

In an observational lead, you project authority by talking about an issue at hand and relating the information back to the big picture.

Observational leads usually aren’t used for breaking news, and they focus more on giving overall context to a situation, rather than just basic facts. They’re a great opportunity to share your perspective, industry savvy, or writing style.

Here are the opening two sentences of a feature from The New York Times that leveraged the observational lead.

“In 2018, senior executives at one of the country’s largest nonprofit hospital chains, Providence, were frustrated. They were spending hundreds of millions of dollars providing free health care to patients. It was eating into their bottom line.” ( 8 )

No. 9: Question Lead

A question lead uses question format to create curiosity and intrigue. Since a question lead is not providing details, the second paragraph of your piece will need to pull extra weight and deliver missing details.

Ensure you have this one-two punch in place so that the rhythm of your article reads properly.

Here's a terrific question lead from an article in The Las Vegas Sun.

“What’s increasing faster than the price of gasoline? Apparently, the cost of court lobbyists.

District and Justice Court Judges want to hire lobbyist Rick Loop for $150,000 to represent the court system in Carson City through the 2009 legislative session. During the past session, Loop’s price tag was $80,000.” ( 9 )

Question leads are also popular in SEO writing , especially questions addressed directly to the reader. Most search engine traffic is people with intent who are trying to have their questions answered; this approach is an easier way to hook readers, but it is sometimes considered low-brow.

Let's look at a question lead from Social Media Examiner that followed this format.

“Are you using TikTok or Instagram for business? Looking for a content strategy that works and won’t leave you exhausted?

In this article, you’ll discover a three-step strategy to create highly engaging TikTok and Instagram content that will scale your audience while helping you avoid burnout.” ( 10 )

Come Up With a Good Hook

To write an effective lead, begin with a strong hook that instantly grabs your readers' attention.

Consider using a thought-provoking question, a surprising fact, or an engaging anecdote that relates to the topic. The key is to make your readers curious and eager to find out more.

For example, if you're writing an article about the benefits of exercise, you could start your lead with a captivating question like, "Did you know that just 30 minutes of daily exercise can add years to your life?"

Related: How to Write Powerful Headlines

Know Your Audience

Understanding your target audience is essential to create a lead that resonates well. Consider your readers’ demographics, interests, and motivations.

For instance, if you are writing a lead for a tech-savvy audience, you may want to start with a powerful statistic or a cutting-edge technological breakthrough. On the other hand, if your audience consists of beginners, you could begin with a relatable storytelling approach to ease them into the topic.

Tailoring your lead to the specific interests of your readers will increase their engagement and make them more likely to continue reading. This is a core concept of positioning.

Keep It Short and Concise

In our fast-paced digital age, attention spans are shrinking. To capture your readers' interest and keep them engaged, keep your lead short and concise.

Use clear and concise language to convey your message effectively. Long-winded leads tend to lose readers' interest quickly, so aim for brevity.

Pro Tip : Avoid unnecessary jargon or complex sentences that may confuse or bore your audience. Instead, focus on making your point succinctly and compellingly.

Use Keywords Strategically

In today's digital landscape, search engine optimization (SEO) is a crucial element in writing leads. Strategic placement of relevant keywords helps search engines recognize the relevance of your content and boost its visibility in search results.

When writing your lead, identify the primary keyword or key phrase that represents your topic. For instance, if you're writing an article on budget travel tips, the primary keyword may be "budget travel." Integrate the keyword naturally in your lead to make it more search-engine-friendly and increase your chances of attracting organic traffic.

Limited-Time Offer: ‘The Medium Workshop’

Get The Medium Workshop and two other resources as part of the Camp Wordsmith® Sneak Peek Bundle , a small-bite preview of my company's flagship publishing program. Offer expires one hour from reveal.

Consider writing your lead first, then editing your lead last.

The lead will give you a running start, and is usually one of the first things you will write when you sit down in front of a blank page. However, since the lead needs to accurately capture the essence of your article, it’s helpful to have the rest of your piece developed before attempting to summarize it.

Leads are surprisingly challenging to write, but when done well, they make an article sing.

When you’re able to communicate a message quickly — whether it be yours or someone else’s — your words will reach more people and make a bigger impact in the long run. ◆

Thanks For Reading 🙏🏼

Keep up the momentum with one or more of these next steps:

💬 Leave a comment below. Let me know a takeaway or thought you had from this post.

📣 Share this post with your network or a friend. Sharing helps spread the word, and posts are formatted to be both easy to read and easy to curate – you'll look savvy and informed.

📲 Follow on another platform. I'm active on Medium, Instagram, and LinkedIn ; if you're on any of those, say hello.

📬 Sign up for my free email list. “The Morning Walk” is a free newsletter about commerce, technology, and personal entrepreneurship. Learn more and browse past editions here .

🏕 Up your writing game. Camp Wordsmith® is a content marketing strategy program for small business owners, service providers, and online professionals. Learn more here.

📊 Hire me for consulting. I provide 1-on-1 consultations through my company, Hefty Media Group. We're a certified diversity supplier with the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce. Learn more here.

Welcome to the blog. Nick Wolny is a writer, editor and copy consultant based in Los Angeles.

How to Write a Lead: 10 Do’s, 10 Don’ts, 10 Good Examples

- Written By Megan Krause

- Updated: November 15, 2023

What is lead writing?

It’s the opening hook that pulls you in to read a story. The lead should capture the essence of the who , what , when , where , why, and how — but without giving away the entire show. A good lead is enticing. It beckons. It promises the reader their time will be well-spent and sets the tone and direction of the piece. All great content starts with a great lead.

Old-school reporting ace and author of ‘The Word: An Associated Press Guide to Good News Writing,’ Jack Cappon, rightly called lead writing “the agony of square one.” A lot if hinging on your lead. From it, readers will decide whether or not they’ll continue investing time and energy into your content or jump ship. And with our culture’s currently short attention spans and patience, if your content doesn’t hook people up front, they’ll bolt. The “back” button is just a thumb tap away.

So, let’s break down the types of leads, which ones you should be writing, and the top 10 do’s and don’ts. We’ll get you hooking customers in no time.

Two Types of Leads

There are two main types of leads and many, many variations thereof. These are:

The summary lead

Most often found in straight news reports, this is the trusty inverted-pyramid lead we learned about in Journalism 101. It sums up the situation succinctly, giving the reader the most important facts first. In this type of lead, you want to determine which aspect of the story — who, what, when, where, why, and how — is most important to the reader and present those facts.

An alleged virgin gave birth to a son in a barn just outside of Bethlehem last night. Claiming a celestial body guided them to the site, magi attending the birth say the boy will one day be king. Herod has not commented.

A creative or descriptive lead

This can be an anecdote, an observation, a quirky fact, or a funny story, among other things. Better suited to feature stories and blog posts, these leads are designed to pique readers’ curiosity and draw them into the story. If you go this route, make sure to provide broader detail and context in the few sentences following your lead. A creative lead is great — just don’t make your reader hunt for what the story’s about much after it.

Mary didn’t want to pay taxes anyway.

A note about the question lead. A variation of the creative lead, the question lead is just what it sounds like: leading with a question. Most editors (myself included) don’t like this type of lead. It’s lazy writing. People are reading your content to get answers, not to be asked anything. It feels like a cop-out, like a writer couldn’t think of a compelling way to start the piece. Do you want to learn more about the recent virgin birth? Well duh, that’s why I clicked in here in the first place.

Is there no exception? Sure there is. If you can make your question lead provocative, go for it — Do you think you have it bad? This lady just gave birth in a barn — just know that this is accomplished rarely.

Which Type of Lead Should You Write?

This depends on a few factors. Ask yourself:

Who is your audience?

Tax attorneys looking for recent changes in the law don’t want to wade through your witty repartee about the IRS, just as millennials searching for craft beer recipes don’t want to read a technical discourse on the fermentation process. Tailor your words to those reading the post.

Where will this article be published?

Match the site’s tone and language. There are some things you can get away with on Vice.com that would be your demise on the Chronicle of Higher Education .

What are you writing about?

Certain topics naturally lend themselves to creativity, while others beg for a “Just the facts, ma’am” presentation. Writing about aromatherapy for a yoga blog gives you a little more leeway than writing about investment tips for a retirement blog.

Lead Writing: Top 10 do’s

1. determine your hook..

Look at the 5 Ws and 1 H. Why are readers clicking on this content? What problem are they trying to solve? What’s new or different? Determine which aspects are most relevant and important, and lead with that.

2. Be clear and succinct.

Simple language is best. Mark Twain said it best: “Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do.”

3. Write in the active voice.

Use strong verbs and decided language. Compare “Dog bites man” to “A man was bitten by a dog” — the passive voice is timid and bland (for the record, Stephen King feels the same way).

4. Address the reader as “you.”

This is the writer’s equivalent to breaking the fourth wall in theatre, and while some editors will disagree with me on this one, we stand by it. People know you’re writing to them. Not only is it OK to address them as such, we think it helps create a personal connection with them.

5. Put attribution second.

What’s the nugget, the little gem you’re trying to impart? Put that information first, and then follow it up with who said it. The “according to” part is almost always secondary to what he or she actually said.

6. Go short and punchy.

Take my recent lead for this Marketing Land post : “Freelance writers like working with me. Seriously, they do.” Short and sweet makes the reader want to know where you’re going with that.

7. If you’re stuck, find a relevant stat.

If you’re trying to be clever or punchy or brilliant, and it’s just not happening, search for an interesting stat related to your topic and lead with that. This is especially effective if the stat is unusual or unexpected, as in, “A whopping 80 percent of Americans are in debt.”

8. Or, start with a story.

If beginning with a stat or fact isn’t working for your lead, try leading with an anecdote instead. People absorb data, but they feel stories. Here’s an example of an anecdotal lead that works great in a crime story: “It’s just after 11 p.m., and Houston police officer Al Leonard has his gun drawn as the elderly black man approaches the patrol car. The 9mm pistol is out of sight, pointing through the car door. Leonard rolls down his window and casually greets the man. ‘What can I do for you?'” You want to know what happens next, don’t you?

9. Borrow this literary tactic.

Every good story has these three elements : a hero we relate to, a challenge (or villain) we fear, and an ensuing struggle. Find these elements in the story you’re writing and lead with one of those.

10. When you’re staring at a blank screen.

Just start. Start writing anything. Start in the middle of your story. Once you begin, you can usually find your lead buried a few paragraphs down in this “get-going” copy. Your lead is in there — you just need to cut away the other stuff first.

Lead Writing: Top 10 don’ts

1. don’t make your readers work too hard..

Also known as “burying the lead,” this happens when you take too long to make your point. It’s fine to take a little creative license, but if readers can’t figure out relatively quickly what your article is about, they’ll bounce.

2. Don’t try to include too much.

Does your lead contain too many of the 5 Ws and H? Don’t try to jam everything in there — you’ll overwhelm the reader.

3. Don’t start sentences with “there is” or “there are” constructions.

It’s not wrong, but similar to our question lead, it’s lazy, boring writing.

4. Don’t be cliche.

We beg of you .

5. Don’t have any errors.

Include typos or grammatical errors, and it’s game over — you’ve lost the reader.

6. Don’t say anything is “right around the corner.”

Just trust us. We’ve seen it used way too much. “Valentine’s Day is right around the corner,” “The first day of school is right around the corner,” Mother’s Day sales are right around the corner” … Zzzz. Boring .

7. Don’t make puns. Even ironically.

It’s an old example but it proves the point. From a Huffington Post story about a huge swastika found painted on the bottom of a swimming pool in Brazil: “Authorities did Nazi this coming.” Boo. Absolutely not. Don’t make the reader groan.

8. Don’t state the obvious.

Don’t tell readers what they already know. We call it “water is wet” writing. Some examples: “The internet provides an immense source of useful information.” “Today’s digital landscape is moving fast.” Really! You don’t say?

9. Don’t cite the dictionary.

“Merriam-Webster defines marketing as…” This is the close cousin of “water is wet” writing. It’s a better tactic for essay-writing middle-schoolers. Don’t do this.

10. Don’t imagine anything. You are not John Lennon.

“Imagine a world where everyone recycled,” “Imagine how good it must feel to save a life,” “Imagine receiving a $1,000 tip from your favorite customer on Christmas Eve.” Imagine we retired this hackneyed, worn-out lead.

10 Worthy Examples of Good Lead Writing

1. short and simple..

Edna Buchanan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning crime reporter for The Miami Herald, wrote a story about an ex-con named Gary Robinson. One drunken night in the ‘80s, Robinson stumbled into a Church’s Chicken, where he was told there was no fried chicken, only nuggets. He decked the woman at the counter, and in the ensuing melee, he was shot by a security guard. Buchanan’s lead:

Gary Robinson died hungry.

2. Ooh, tell me more.

A 2010 piece in the New York Times co-authored by Sabrina Tavernise and Dan Froschjune begins:

An ailing, middle-age construction worker from Colorado, on a self-proclaimed mission to help American troops, armed himself with a dagger, a pistol, a sword, Christian texts, hashish and night-vision goggles and headed to the lawless tribal areas near the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan to personally hunt down Osama bin Laden.

3. Meanwhile, at San Quentin.

From the 1992 story titled, “After Life of Violence Harris Goes Peacefully,” written by Sam Stanton for The Sacramento Bee:

In the end, Robert Alton Harris seemed determined to go peacefully, a trait that had eluded him in the 39 violent and abusive years he spent on earth.

Remember Olympic jerk Ryan Lochte, the American swimmer who lied to Brazilian authorities about being robbed at gunpoint while in Rio for 2016 games? Sally Jenkins’ story on Lochte for The Washington Post begins:

Ryan Lochte is the dumbest bell that ever rang.

5. An oldie but man, what a goodie.

This beautiful lead is from Shirley Povich’s 1956 story in The Washington Post & Times Herald about a pitcher’s perfect game:

The million‑to‑one shot came in. Hell froze over. A month of Sundays hit the calendar. Don Larsen today pitched a no-hit, no‑run, no‑man‑reach‑first game in a World Series.

6. Dialogue lead.

Diana Marcum wrote this compelling lead for the Los Angeles Times , perfectly capturing the bleakness of the California drought in 2014:

The two fieldworkers scraped hoes over weeds that weren’t there. “Let us pretend we see many weeds,” Francisco Galvez told his friend Rafael. That way, maybe they’d get a full week’s work.

7. The staccato lead.

Ditto; we found this one in an online journalism quiz , but can’t track the source. It reads like the first scene of a movie script:

Midnight on the bridge… a scream… a shot… a splash… a second shot… a third shot. This morning, police recovered the bodies of Mr. and Mrs. R. E. Murphy, estranged couple, from the Snake River. A bullet wound was found in the temple of each.

8. Hey, that’s us.

Sure, we’ll include our own former Dear Megan column railing against exclamation points:

This week’s question comes to us from one of my kids, who will remain nameless because neither wants to appear in a dorky grammar blog written by their uncool (but incredibly good-looking) mom. I will oblige this request for anonymity because, despite my repeated claims about how lucky they are to have me, apparently I ruin their lives on a semi-regular basis. Why add to their torment by naming them here? I have so many other ways I’d rather torment them.

9. The punch lead.

From numerous next-day reports following the Kennedy assassination:

The president is dead.

10. Near perfection.

Finally, this lead comes from a 1968 New York Times piece written by Mark Hawthorne. It was recently featured in the writer’s obituary :

A 17-year-old boy chased his pet squirrel up a tree in Washington Square Park yesterday afternoon, touching off a series of incidents in which 22 persons were arrested and eight persons, including five policemen, were injured.

Time to Put That Lead Writing to Good Use

Alright, now that you’ve read this article, you’re going to be hooking readers left and right with captivating leads. What’s next? Well, if you want to showcase your new skills while working with top brands, join our Talent Network . We’ll match you with companies that fit your talent and expertise to take your career to the next level.

Stay in the know.

We will keep you up-to-date with all the content marketing news and resources. You will be a content expert in no time. Sign up for our free newsletter.

Elevate Your Content Game

Transform your marketing with a consistent stream of high-quality content for your brand.

You May Also Like...

The Strategic Ensemble Behind Effective Content

Everything to Know About the Power of SEO Personalization

Personalized Content Strategies: Gaining the Competitive Edge

- Content Production

- Build Your SEO

- Amplify Your Content

- For Agencies

Why ClearVoice

- Talent Network

- How It Works

- Freelance For Us

- Statement on AI

- Talk to a Specialist

Get Insights In Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Intellectual Property Claims

- Data Collection Preferences

How to Start an Essay with Strong Hooks and Leads

ALWAYS START AN ESSAY WITH AN ENGAGING INTRODUCTION

Getting started is often the most challenging part of writing an essay, and it’s one of the main reasons our students are prone to leaving their writing tasks to the last minute.

But what if we could give our students some tried and tested tips and strategies to show them how to start an essay?

What if we could give them various strategies they could pull out of their writer’s toolbox and kickstart their essays at any time?

In this article, we’ll look at tried and tested methods and how to start essay examples to get your students’ writing rolling with momentum to take them to their essays’ conclusion.

Once you have worked past the start of your essay, please explore our complete guide to polishing an essay before submitting it and our top 5 tips for essay writing.

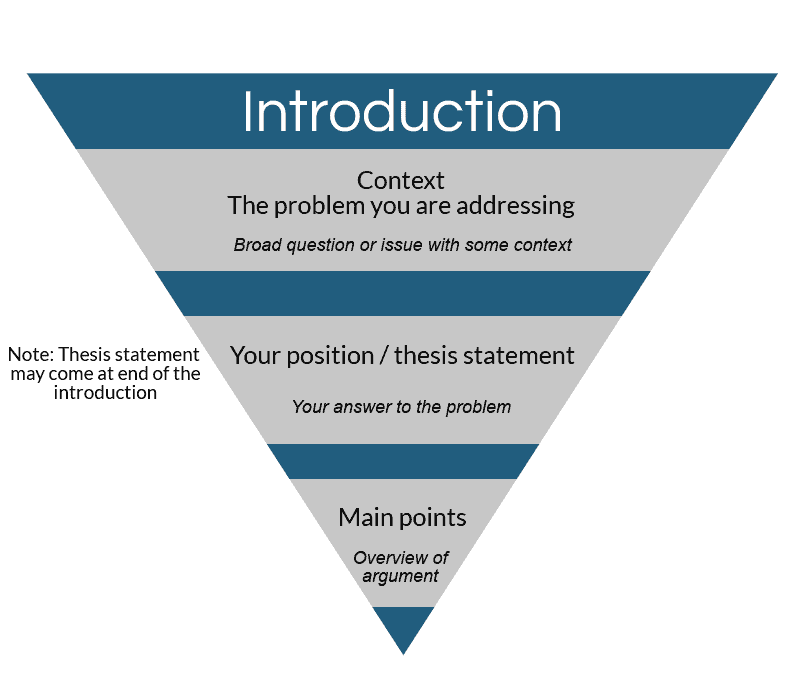

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF AN ESSAY’S INTRODUCTION?

Essentially, the purpose of the introduction is to achieve two things:

1. To orientate the reader

2. To motivate the reader to keep reading.

An effective introduction will give the reader a clear idea of what the essay will be about. To do this, it may need to provide some necessary background information or exposition.

Once this is achieved, the writer will then make a thesis statement that informs the reader of the main ‘thrust’ of the essay’s position, the supporting arguments of which will be explored throughout the body paragraphs of the remainder of the essay.

When considering how to start an essay, ensure you have a strong thesis statement and support it through well-crafted arguments in the body paragraphs . These are complex skills in their own right and beyond the scope of this guide, but you can find more detail on these aspects of essay writing in other articles on this site that go beyond how to start an essay.

For now, our primary focus is on how to grab the reader’s attention right from the get-go.

After all, the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step or, in this case, a single opening sentence.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON WRITING HOOKS, LEADS & INTRODUCTIONS

Teach your students to write STRONG LEADS, ENGAGING HOOKS and MAGNETIC INTRODUCTIONS for ALL TEXT TYPES with this engaging PARAGRAPH WRITING UNIT designed to take students from zero to hero over FIVE STRATEGIC LESSONS.

WHAT IS A “HOOK” IN ESSAY WRITING?

A hook is a sentence or phrase that begins your essay, grabbing the reader’s attention and making them want to keep reading. It is the first thing the reader will see, and it should be interesting and engaging enough to make them want to read more.

As you will learn from the how to start an essay examples below, a hook can be a quote, a question, a surprising fact, a personal story, or a bold statement. It should be relevant to the topic of your essay and should be able to create a sense of curiosity or intrigue in the reader. The goal of a hook is to make the reader want to read on and to draw them into the central argument or point of your essay.

Some famous examples of hooks in literature you may have encountered are as follows.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen” George Orwell in 1984

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife” – Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice

HOW TO HOOK THE READER WITH ATTENTION-GRABBING OPENING SENTENCES

We all know that every essay has a beginning, a middle , and an end . But, if our students don’t learn to grab the reader’s attention from the opening sentence, they’ll struggle to keep their readers engaged long enough to make it through the middle to the final full stop. Take a look at these five attention-grabbing sentence examples.

- “The secret to success is hidden in a single, elusive word: persistence.”

- “Imagine a world without electricity, where the only source of light is the flame of a candle.”

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, but most importantly, it was the time that changed everything.”

- “They said it couldn’t be done, but she proved them wrong with her grit and determination.”

- “He stood at the edge of the cliff, staring down at the tumultuous ocean below, knowing that one misstep could mean certain death.”

Regardless of what happens next, those sentences would make any reader stop whatever else they might focus on and read with more intent than before. They have provided the audience with a “hook” intended to lure us further into their work.

To become effective essay writers, your students need to build the skill of writing attention-grabbing opening sentences. The best way of achieving this is to use ‘hooks’.

There are several kinds of hooks that students can choose from. In this article, we’ll take a look at some of the most effective of these:

1. The Attention-Grabbing Anecdote

2. The Bold Pronouncement!

3. The Engaging Fact

4. Using an Interesting Quote

5. Posing a Rhetorical Question

6. Presenting a Contrast

How appropriate each of these hooks is will depend on the essay’s nature. Students must consider the topic, purpose, tone, and audience of the essay they’re writing before deciding how best to open it.

Let’s look at each of these essay hooks, along with a practice activity students can undertake to put their knowledge of each hook into action.

1: HOW TO START AN ESSAY WITH “THE ATTENTION-GRABBING ANECDOTE”

Anecdotes are an effective way for the student to engage the reader’s attention right from the start.

When the anecdote is based on the writer’s personal life, they are a great way to create intimacy between the writer and the reader from the outset.

Anecdotes are an especially useful starting point when the essay explores more abstract themes as they climb down the ladder of abstraction and fit the broader theme of the essay to the shape of the writer’s life.

Anecdotes work because they are personal, and because they’re personal, they infuse the underlying theme of the essay with emotion.

This expression of emotion helps the writer form a bond with the reader. And it is this bond that helps encourage the reader to continue reading.

Readers find this an engaging approach, mainly when the topic is complex and challenging.

Anecdotes provide an ‘in’ to the writing’s broader theme and encourage the reader to read on.

Examples of Attention-grabbing anecdotes

- “It was my first day of high school, and I was a bundle of nerves. I had always been a shy kid, and the thought of walking into a new school, surrounded by strangers was overwhelming. But as I walked through the front doors, something unexpected happened. A senior, who I had never met before, came up to me and said ‘Welcome to high school; it’s going to be an amazing four years.’ That one small act of kindness from a complete stranger made all the difference, and from that day on, I knew that I would be okay.”

- “I was in my math class and having a tough day. I had a test coming up, and I was struggling to understand the material. My teacher, who I had always thought was strict and unapproachable, noticed that I was struggling and asked if I needed help. I was surprised, but I took her up on her offer, and she spent extra time with me after class, helping me to understand the material. That experience taught me that sometimes, the people we think we know the least about are the ones who can help us the most.”

- “It was the last day of 8th grade, and we were all sitting in the auditorium, waiting for the ceremony to begin. Suddenly, the principal got on stage and announced that there was a surprise guest speaker. I was confused and curious, but when the guest walked out on stage, I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was my favorite rapper who had come to speak to us about the importance of education. That moment was a turning point for me, it showed me that if you work hard and believe in yourself, anything is possible.”

Attention-Grabbing Anecdote Teaching Strategies

One way to help students access their personal stories is through sentence starters, writing prompts, or well-known stories and their themes.

First, instruct students to choose a theme to write about. For example, if we look at the theme of The Boy Who Cried Wolf, something like: we shouldn’t tell lies, or people may not believe us when we tell the truth.

Fairytales and fables are great places for students to find simple themes or moral lessons to explore for this activity.

Once they’ve chosen a theme, encourage the students to recall a time when this theme was at play in their own lives. In the case above, a time when they paid the cost, whether seriously or humorously, for not telling the truth.

This memory will form the basis for a personal anecdote that will form a ‘hook’. Students can practice replicating this process for various essay topics.

It’s essential when writing anecdotes that students attempt to capture their personal voice.

One way to help them achieve this is to instruct them to write as if they were orally telling their story to a friend.

This ‘vocal’ style of writing helps to create intimacy between writer and reader, which is the hallmark of this type of opening.

2: HOW TO START AN ESSAY WITH “THE BOLD PRONOUNCEMENT”

As the old cliché “Go big or go home!” would have it, making a bold pronouncement at the start of an essay is one surefire way to catch the reader’s attention.

Bold statements exude confidence and assure the reader that this writer has something to say that’s worth hearing. A bold statement placed right at the beginning suggests the writer isn’t going to hedge their bets or perch passively on a fence throughout their essay.

The bold pronouncement technique isn’t only useful for writing a compelling opening sentence, the formula can be used to generate a dramatic title for the essay.

For example, the recent New York Times bestseller ‘Everybody Lies’ by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz is an excellent example of the bold pronouncement in action.

Examples of Bold Pronouncements

- “I will not be just a statistic, I will be the exception. I will not let my age or my background define my future, I will define it myself.”

- “I will not be afraid to speak up and make my voice heard. I will not let anyone silence me or make me feel small. I will stand up for what I believe in and I will make a difference.”

- “I will not be satisfied with just getting by. I will strive for greatness and I will not be content with mediocrity. I will push myself to be the best version of me, and I will not settle for anything less.”

Strategies for Teaching how to write a Bold Pronouncement

Give the students a list of familiar tales; again, Aesop’s Fables make for a good resource.

In groups, have them identify some tales’ underlying themes or morals. For this activity, these can take the place of an essay’s thesis statement.

Then, ask the students to discuss in their groups and collaborate to write a bold pronouncement based on the story. Their pronouncement should be short, pithy, and, most importantly, as bold as bold can be.

3: HOW TO START AN ESSAY WITH “THE ENGAGING FACT”

In our cynical age of ‘ fake news ’, opening an essay with a fact or statistic is a great way for students to give authority to their writing from the very beginning.

Students should choose the statistic or fact carefully, it should be related to their general thesis, and it needs to be noteworthy enough to spark the reader’s curiosity.

This is best accomplished by selecting an unusual or surprising fact or statistic to begin the essay with.

Examples of the Engaging Fact

- “Did you know that the average teenager spends around 9 hours a day consuming media? That’s more than the time they spend sleeping or in school!”

- “The brain continues to develop until the age of 25, which means that as a teenager, my brain is still going through major changes and growth. This means I have a lot of potential to learn and grow.”

- “The average attention span of a teenager is shorter than that of an adult, meaning that it’s harder for me to focus on one task for an extended time. This is why it is important for me to balance different activities and take regular breaks to keep my mind fresh.”

Strategies for teaching how to write engaging facts

This technique can work well as an extension of the bold pronouncement activity above.

When students have identified each of the fables’ underlying themes, have them do some internet research to identify related facts and statistics.

Students highlight the most interesting of these and consider how they would use them as a hook in writing an essay on the topic.

4: HOW TO START AN ESSAY USING “AN INTERESTING QUOTATION”

This strategy is as straightforward as it sounds. The student begins their essay by quoting an authority or a well-known figure on the essay’s topic or related topic.

This quote provides a springboard into the essay’s subject while ensuring the reader is engaged.

The quotation selected doesn’t have to align with the student’s thesis statement.

In fact, opening with a quotation the student disagrees with can be a great way to generate a debate that grasps the reader’s attention from the outset.

Examples of starting an essay with an interesting quotation.

- “As Albert Einstein once said, ‘Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.’ As a 16-year-old student, I know how it feels to be judged by my ability to climb the “academic tree” and how it feels to be labeled as “stupid”. But just like the fish in Einstein’s quote, I know that my true potential lies in my unique abilities and talents, not in how well I can climb a tree.”

- “Mark Twain once said, ‘Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.’ This quote resonates with me because as a teenager, I often feel pressure to conform to the expectations and opinions of my peers. But this quote reminds me to take a step back and think for myself, rather than blindly following the crowd.”

- “As J.K. Rowling famously said, ‘It does not do to dwell on dreams and forget to live.’ As a 16-year-old student, I often find myself getting lost in my dreams for the future and forgetting to live in the present. But this quote serves as a reminder to me to strive for my goals while also cherishing and living in the here and now.”

Teaching Strategies for starting an essay with an interesting quotation.

To gain practice in this strategy, organize the students into groups and have them generate a list of possible thesis statements for their essays.

Once they have a list of statements, they now need to generate a list of possible quotations related to their hypothetical essay’s central argument .

Several websites are dedicated to curating pertinent quotations from figures of note on an apparently inexhaustible array of topics. These sites are invaluable resources for tracking down interesting quotations for any essay.

5: HOW TO START AN ESSAY BY “POSING A RHETORICAL QUESTION”

What better way to get a reader thinking than to open with a question?

See what I did there?

Beginning an essay with a question not only indicates to the reader the direction the essay is headed in but also challenges them to respond personally to the topic.

Rhetorical questions are asked to make a point and to get the reader thinking rather than to elicit an answer.

One effective way to use a rhetorical question in an introduction is to craft a rhetorical question from the thesis statement and use it as the opening sentence.

The student can then end the opening paragraph with the thesis statement itself.

In this way, the student has presented their thesis statement as the answer to the rhetorical question asked at the outset.

Rhetorical questions also make for valuable transitions between paragraphs.

Examples of starting an essay with a rhetorical question

- “What if instead of judging someone based on their appearance, we judged them based on their character? As a 16-year-old, I see the damage caused by judging someone based on their physical appearance, and it’s time to move away from that and focus on character.”

- “How can we expect to solve the world’s problems if we don’t start with ourselves? As a 16-year-old student, I am starting to see the issues in the world, and I believe that before we can make any progress, we need to start with ourselves.”

- “What would happen if we stopped labelling people by race, religion, or sexual orientation? As a teenager growing up in a diverse world, I see the harm caused by labelling and stereotyping people; it’s time for us to stop and see people for who they truly are.”

Teaching Students how to start an essay with a rhetorical question

To get some experience posing rhetorical questions, organize your students into small groups, and give each group a list of essay thesis statements suited to their age and abilities.

Task the students to rephrase each of the statements as questions.

For example, if we start with the thesis statement “Health is more important than wealth”, we might reverse engineer a rhetorical question such as “What use is a million dollars to a dying man?”

Mastering how to start an essay with a question is a technique that will become more common as you progress in confidence as a writer.

6: HOW TO START AN ESSAY BY “PRESENTING A CONTRAST”

In this opening, the writer presents a contrast between the image of the subject and its reality. Often, this strategy is an effective opener when widespread misconceptions on the subject are widespread.

For example, if the thesis statement is something like “Wealth doesn’t bring happiness”, the writer might open with a scene describing a lonely, unhappy person surrounded by wealth and opulence.

This scene contrasts a luxurious setting with an impoverished emotional state, insinuating the thrust of the essay’s central thesis.

Examples of Starting an essay by presenting a contrast

- “On one hand, technology has made it easier to stay connected with friends and family than ever before. On the other hand, it has also created a sense of disconnection and loneliness in many people, including myself as a 16-year-old. “

- “While social media has allowed us to express ourselves freely, it has also led to a culture of cyberbullying and online harassment. As a teenager, I have seen social media’s positive and negative effects.”

- “On one hand, the internet has given us access to a wealth of information. On the other hand, it has also made it harder to separate fact from fiction and to distinguish credible sources from fake news. This is becoming increasingly important for me as a 16-year-old student in today’s society.”

Teaching Strategies for presenting a contrast when starting an essay.

For this activity, you can use the same list of thesis statements as in the activity above. In their groups, challenge students to set up a contrasting scene to evoke the essay’s central contention, as in the example above.

The scene of contrast can be a factual one in a documentary or anecdotal style, or a fictionalized account.

Whether the students are using a factual or fictional scene for their contrast, dramatizing it can make it much more persuasive and impactful.

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

These aren’t the only options available for opening essays, but they represent some of the best options available to students struggling to get started with the concept of how to create an essay.

With practice, students will soon be able to select the best strategies for their needs in various contexts.

To reinforce their understanding of different strategies for starting an introduction for an essay, encourage them to pay attention to the different choices writers make each time they begin reading a new nonfiction text.

Just like getting good at essay writing itself, getting good at writing openings requires trial and error and lots and lots of practice.

USEFUL VIDEO TUTORIALS ON WRITING AN ESSAY INTRODUCTION

- Essay Examples

- Privacy Policy

How To Write a Good Lead? Tips and Examples of Leads

- August 2, 2022 August 31, 2022

What is a lead, and why do you need one for your piece of writing?

A lead (sometimes pronounced as lede ) is the opening paragraph of a piece of writing that gives readers an overview of what the article or story will be about. A good lead will also hook readers in and make them want to keep reading. Humans are naturally curious , so why not use it to your advantage?

The main goal of a lead is to exploit readers’ curiosity by making them wonder what will happen next. You should give a “reading momentum” to your readers, which will push them to read further, and this is what a great lead makes.

Leads are typically used for news writing and journalistic writing. However, you can also use leads in essay writing as well, especially if your essay is relatively short.

So, let’s go deeper into lead writing and check out some tips and examples of good leads.

How long should a lead be?

The length of your lead should be directly proportional to the overall length of your piece. That means that if you’re writing a short article, it can be only one sentence . If your article is longer, you can write several sentences .

Ideally, your lead should be no more than one or two sentences for a short article and no more than three or four sentences for a longer piece.

Most common types of leads

In general, there are two major lead types: summary lead and creative lead .

Summary Lead (traditional lead)

This is the most traditional lead type, and it provides a summary of the article or a news story in as few words as possible.

As you can guess, the summary lead provides a quick summary by answering the 5 Ws: Who, What, When, Where, and Why . We will take a closer look at these elements below.

Creative Lead

A creative lead is typically used in feature or informal writing , and it’s designed to provoke curiosity or set the scene for the story. This can be done in many ways, but some of the most common ones include starting with a thought-provoking question, a quotation, or an anecdote to grab readers’ interest .

Writing Leads: Lead examples

1. the straight news lead.

This type of lead is often used for writing hard news stories and usually answers the five Ws: who, what, when, where, and why. It is often seen in newspaper writing.

Refers to the subject of the story.

Is the main point or event of the story.

Tells when the event happened or will happen.

Scene setting – where the event happened or will happen.

Provides the purpose or reason for the story

This is often referred to as the “just the facts” approach. It can be especially effective for breaking news stories where time is of the essence.

Hundreds of people are homeless after a fire ripped through a local apartment complex last night.

2. The Quotation Lead

You can start writing this lead by featuring a direct quotation from a person or people involved in the story. It is often used in human interest stories or stories about controversial topics.

“I’m disgusted with the way our government is handling this issue,” says John Doe, a local citizen.

3. The Anecdotal Lead

This type of lead tells a brief story or an anecdote related to the main topic of the article or essay. It is often used in human interest stories, as well as in stories about controversial topics.

When Jane Doe was sixteen, she never imagined that she would one day be homeless.

4. The Statistic Lead

This type of lead features a statistic related to the main topic of the article or essay. It is often used in stories about controversial topics or issues.

According to a recent study, nearly 60% of Americans are dissatisfied with the current state of the economy.

5. The Feature Lead

This type of lead is often used in feature stories, which are longer and more in-depth than hard news stories . Feature leads are usually more creative than straight news leads, and they often use literary devices such as similes or metaphors.

This story happened in the city that was a concrete jungle, a never-ending maze of gray and brown.

6. The Question Lead

This type of lead features a question related to the main topic of the article or essay. Questions can be effective in grabbing readers’ attention and making them want to find out the answer .

How many times have you seen a homeless person on the street and wondered what their story is?

7. One Word or Short Phrase Lead

This type of lead features a word or phrase, or short sentence , that is related to the main topic of the article or essay. This can be an effective way to start a story, especially if the word or phrase is interesting, thought-provoking, or unexpected.

“We all want what’s best for our children.”

This is a great lead-in to an article about parenting or education. It’s a universal truth that every parent wants what’s best for their child, so this lead sets up the rest of the article nicely.

8. Staccato Lead

Staccato is a musical term meaning “detached” or “unconnected.” In writing, it means to keep your sentences and thoughts short. This lead focuses on just one main idea per sentence. It’s a great way to add punchiness and vibrancy to your writing, but be careful not to overdo it , or your writing will sound choppy.

The city bustled with activity. People hurried to and fro. Cars honked their horns. No one had expected the tornado to hit so quickly.

9. Zinger Lead

A zinger is a rhetorical device used to make a sudden, sharp, or surprising statemen t. It’s often used for comic effect, but it can also be used to make a serious point. A zinger lead is a great way to grab your reader’s attention and get them hooked on your story.

I never thought I’d see the day when my dog would be arrested.

10. Delayed Identification Lead

The delayed identification lead, also known as the “mysterious stranger” lead, is a great way to add suspense and intrigue to your story. In this type of lead, you don’t identify the main character or subject of the story until later on. You can use a descriptive pronoun (such as “the man” or “the woman”) if you want to give your reader a hint about who the mystery person is and reveal his or her identity in a later paragraph .

The woman walked into the room and everyone fell silent. She had an aura of power about her, and it was clear that she was not to be messed with.

So as you can see, there are no limitations when it comes to writing a good lead. Just let your creativity flow and choose the lead type that fits your story best.

How to write a lead sentence – tips to keep in mind

- When writing your lead, be sure to use an active voice . This makes your writing sound more lively and engaging. Passive voice often sounds dull and boring.

- Use active verbs . This will also make your writing sound more lively and engaging.

- Active sentences are shorter and easier to read than passive sentences . This is important because you want your readers to actually read what you’ve written, not just skim over it.

- Be concise . Writing leads is all about getting to the point quickly. Don’t try to be too wordy, or you’ll lose your reader’s attention.

- Good leads should be attention-grabbing , but they shouldn’t give away too much. You want to leave your reader wanting more.

- Most readers will make up their minds about your article or essay within the first few sentences. People are lazy, and they rarely read post the first paragraph.

Now that you know all about leads, it’s time to put what you’ve learned into practice. Choose one of the lead types from the list above or invent your own lead type and use it to write a good story.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Writing a Lead or Lede to an Article

Rules? What rules? Just tell the story effectively and hold the reader

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A lead or lede refers to the opening sentences of a brief composition or the first paragraph or two of a longer article or essay . Leads introduce the topic or purpose of a paper, and particularly in the case of journalism, need to grab the reader's attention. A lead is a promise of what's to come, a promise that the piece will satisfy what a reader needs to know.

They can take many styles and approaches and be a variety of lengths, but to be successful, leads need to keep the readers reading, or else all the research and reporting that went into the story won't reach anyone. Most often when people talk about leads, it's in professional periodical writing, such as in newspapers and magazines.

Opinions Differ on Length

Many ways exist as far as how to write a lead, the styles of which likely differ based on the tone or voice of the piece and intended audience in a story—and even the overall length of the story. A long feature in a magazine can get away with a lead that builds more slowly than an in-the-moment news story about a breaking news event in a daily paper or on a news website.

Some writers note that the first sentence is the most important of a story; some might extend that to the first paragraph. Still, others might emphasize defining the audience and message to those people in the first 10 words. Whatever the length, a good lead relates the issue to the readers and shows why it's important for them and how it relates to them. If they're invested from the get-go, they'll keep reading.

Hard News Versus Features

Hard news leads get the who, what, why, where, when, and how in the piece up front, the most important bits of information right up top. They're part of the classic reverse-pyramid news story structure.

Features can start off in a multitude of ways, such as with an anecdote or a quotation or dialogue and will want to get the point of view established right away. Feature stories and news both can set the scene with a narrative description . They also can establish a "face" of the story, for example, to personalize an issue by showing how it's affecting an ordinary person.

Stories with arresting leads might exhibit tension right up front or pose a problem that'll be discussed. They might phrase their first sentence in the form of a question.

Where you put the historical information or the background information depends on the piece, but it can also function in the lead to ground the readers and get them context to the piece right away, to immediately understand the story's importance.

All that said, news and features don't necessarily have hard-and-fast rules about what leads work for either type; the style you take depends on the story you have to tell and how it will be most effectively conveyed.

Creating a Hook

"Newspaper reporters have varied the form of their work, including writing more creative story leads . These leads are often less direct and less 'formulaic' than the traditional news summary lead. Some journalists call these soft or indirect news leads. "The most obvious way to modify a news summary lead is to use only the feature fact or perhaps two of the what, who, where, when, why and how in the lead. By delaying some of the answers to these essential reader questions , the sentences can be short, and the writer can create a 'hook' to catch or entice the reader to continue into the body of the story." (Thomas Rolnicki, C. Dow Tate, and Sherri Taylor, "Scholastic Journalism." Blackwell, 2007)

Using Arresting Detail

"There are editors ...who will try to take an interesting detail out of the story simply because the detail happens to horrify or appall them. 'One of them kept saying that people read this paper at breakfast ,' I was told by Edna [Buchanan], whose own idea of a successful lead is one that might cause a reader who is having breakfast with his wife to 'spit out his coffee, clutch his chest, and say, "My God, Martha! Did you read this!"'" (Calvin Trillin, "Covering the Cops [Edna Buchanan]." "Life Stories: Profiles from The New Yorker ," ed. by David Remnick. Random House, 2000)

Joan Didion and Ron Rosenbaum on Leads

Joan Didion : "What's so hard about the first sentence is that you're stuck with it. Everything else is going to flow out of that sentence. And by the time you've laid down the first two sentences, your options are all gone." (Joan Didion, quoted in "The Writer," 1985)

Ron Rosenbaum : "For me, the lead is the most important element. A good lead embodies much of what the story is about—its tone, its focus, its mood. Once I sense that this is a great lead I can really start writing. It is a heuristic : a great lead really leads you toward something." (Ron Rosenbaum in "The New New Journalism: Conversations With America's Best Nonfiction Writers on Their Craft," by Robert S. Boynton. Vintage Books, 2005)

The Myth of the Perfect First Line

"It's a newsroom article of faith that you should begin by struggling for the perfect lead . Once that opening finally comes to you—according to the legend—the rest of the story will flow like lava. "Not likely...Starting with the lead is like starting medical school with brain surgery. We've all been taught that the first sentence is the most important; so it's also the scariest. Instead of writing it, we fuss and fume and procrastinate. Or we waste hours writing and rewriting the first few lines, rather than getting on with the body of the piece... "The first sentence points the way for everything that follows. But writing it before you've sorted out your material, thought about your focus , or stimulated your thinking with some actual writing is a recipe for getting lost. When you're ready to write, what you need is not a finely polished opening sentence, but a clear statement of your theme ." (Jack R. Hart, "A Writer's Coach: An Editor's Guide to Words That Work." Random House, 2006)

- How Feature Writers Use Delayed Ledes

- Learn to Write News Stories

- How to Write a News Article That's Effective

- Avoid the Common Mistakes That Beginning Reporters Make

- What Is the Inverted Pyramid Method of Organization?

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How to Write Great Ledes for Feature Stories

- Writing a Compelling, Informative News Lede

- How to Write Feature Stories

- Learn What a Feature Story Is

- 10 Important Steps for Producing a Quality News Story

- Constructing News Stories with the Inverted Pyramid

- Six Tips for Writing News Stories That Will Grab a Reader

- These Are Frequently Used Journalism Terms You Need to Know

- Learning to Edit News Stories Quickly

- How Reporters Can Write Great Follow-up News Stories

Which program are you applying to?

Accepted Admissions Blog

Everything you need to know to get Accepted

March 7, 2024

Writing an Essay Lead That Pops

How many times have you sampled the first few lines of a book and decided, “Nah, this isn’t for me”? Whether you picked the book up in a store or library, or downloaded free sample online, you probably made a pretty speedy decision about whether it would hold your interest.

The human tendency to rush to judgment

Our extremely fast-paced world has trained us to make snap decisions throughout the day, and if, for example, we’re not hooked instantly by an article, book, movie trailer, or song, we’re just a click away from another, more appealing choice. We might move quickly away from someone at a party who begins to bore us and whom we lack the patience to listen to, for even another minute.

Because we have endless choices, we get choosier and choosier about what we’re willing to stick with. These rapid judgments might not be fair, but the “burden of overchoice” in our lives feeds our short attention spans.

Admissions committee members are human. And the pressure of their job forces them to make very quick decisions about whose applications they will invest more time in and whose will merit only an obligatory but cursory review before being set aside as unworthy of serious consideration.

Their reality is truly “so many applications, so little time,” which means that when you are applying to b-school , med school , grad school , or college , you have to capture your reader’s attention with the very first lines of your essay – before they are tempted to just give it that cursory read and move on to the next application. Your very first sentence cannot fall flat. It must reel them into your narrative. Every word counts.

How to hook your essay readers from the beginning

This sounds like a lot of pressure, right? But this is a challenge you can meet successfully. Think of your lead as the beginning of a good fiction story: something is at stake here, something compelling and colorful, something with a punch. Let’s look at a few examples, and you’ll quickly get the point:

“Horns blare as tiny auto rickshaws and bicycle-powered school buses interweave at impossibly close range in the narrow streets of Old Delhi.”

“After a near disaster during my first week as a case manager at a community center for women and children, I discovered that to succeed in my job, I’d have to restrain my anger at how badly things were run in this place.”

“My aunt’s cancer had already metastasized throughout her body by the time she was finally diagnosed correctly – too late for any effective treatment. At that moment, my interest in a career as a science researcher became much more personal.”

“From the age of seven, when I was struggling with simple math problems but acing my spelling tests and already writing simple stories, I knew I was meant to become a writer.”

Notice that three of these four sample leads are personal anecdotes. They offer no details about the writer’s GPA or technical facts about what they researched in the lab. The first lead is so colorful and dramatic that we instantly want to know more about the person who observed the scene. In every case, the lead begins a story that makes the reader sit up and say, “Ah! This is a dynamic person with a compelling voice!”

Your goal is to write an essay that introduces you to the admissions committee and makes them want to get to know you better. You’re way ahead of the game when your essay introduction really shines.

Three components of a strong lead

A strong essay opener will include three key elements:

- The theme or agenda of your essay, offering the first few facts about who you are, what you are interested in doing with your life/career/studies, and/or important influences

- Creative details or descriptions

- Energetic writing that will keep the reader engaged through the rest of the essay

Good leads connect where you’ve been to where you’re going

Let’s look at a few more engaging first lines:

- “It was absolutely pitch black outside when we had to silently leave our home and climb into the back of a truck, beginning our journey to freedom.”

- “Only six months after I launched my start-up, money was flowing… out the window.”

- “Finding a green, scratched 1960s Cadillac in a dump last summer was the moment I realized that mechanical engineering was for me.”

Wouldn’t you want to keep reading to learn the rest of these stories? I would!

Many clients worry that these kinds of anecdotal introductions are too “soft,” too “personal,” or too “creative.” But the right vibrant anecdote can absolutely do the job of being creative, personal, and strong. A compelling lead draws your reader into your story and make them feel involved in your journey. Descriptive language can go a long way to spice up a straightforward story and help the reader follow you from where you began to where you are headed.

How to write a lead that pops

Now that you have read several great examples of attention-grabbing leads, your mind might already be busy generating ideas for your own essay introduction. Write them down. If you don’t have ideas just yet, though, that’s okay – give yourself some time to think. Make a list of turning-point moments in your life that relate to your educational or professional goals. As we have seen, these experiences can be drawn from anywhere: recent or older work experiences, your cultural or family background, or “aha!” moments.

An electrical engineering applicant could describe the first time their rural home suddenly went dark and they realized they had found their professional calling. An MBA applicant might have had a very profound and meaningful experience offering basic financial guidance to a struggling working-class individual, prompting their goal of pursuing a career in the nonprofit sector. A law school applicant might have witnessed a courtroom scene during an internship that inspired them to pursue a certain type of law. The possibilities go on and on.

As you make your list of anecdotes, jot down as many small, precise details as you can about each memory or experience. Why was this moment important on your journey toward your dream career or school? How did you feel at that moment? How did it help shape you? What did it teach you? Were there any sensory details (sights, smells, tastes, touch) that were particularly relevant to those moments?

Then, try starting your essay with the anecdote itself, inviting the reader to share your experience, and add color, personality, and voice.

At the beginning of this post, we pointed out how easy it is to make snap judgments (perhaps unfairly) about a book, article, film, or acquaintance you just met at a party, and to turn your attention away because you weren’t captivated instantly. We end this post asking you to think about all the times you began sampling a book or story and after the first few lines, you simply had to know what was going to happen next. You bought the book or read the story straight through. You want your essay to be one of those proverbial “page-turners” (even if it’s less than one page) that the admissions committee starts reading and can’t put down. You will have earned their full attention, straight through to the end. Once they’re hooked, you can take them anywhere you please.

Still need help finding that “hook” to open your essay? Our admissions pros will guide you to finding that perfect moment. They can help you plan and craft an application that will draw your readers in with a substantive narrative that will inspire them to place your application in the “admit” pile.

By Judy Gruen, former Accepted admissions consultant. Judy holds a master’s in journalism from Northwestern University. She is also the co-author of Accepted’s first full-length book, MBA Admission for Smarties: The No-Nonsense Guide to Acceptance at Top Business Schools . Want an admissions expert help you get accepted? Click here to get in touch!

Related Resources:

- Five Fatal Flaws to Avoid in Your Grad School Statement of Purpose , a free guide

- Three Must-Have Elements of a Good Statement of Purpose

- Proving Character Traits in Your Essays

About Us Press Room Contact Us Podcast Accepted Blog Privacy Policy Website Terms of Use Disclaimer Client Terms of Service

Accepted 1171 S. Robertson Blvd. #140 Los Angeles CA 90035 +1 (310) 815-9553 © 2022 Accepted

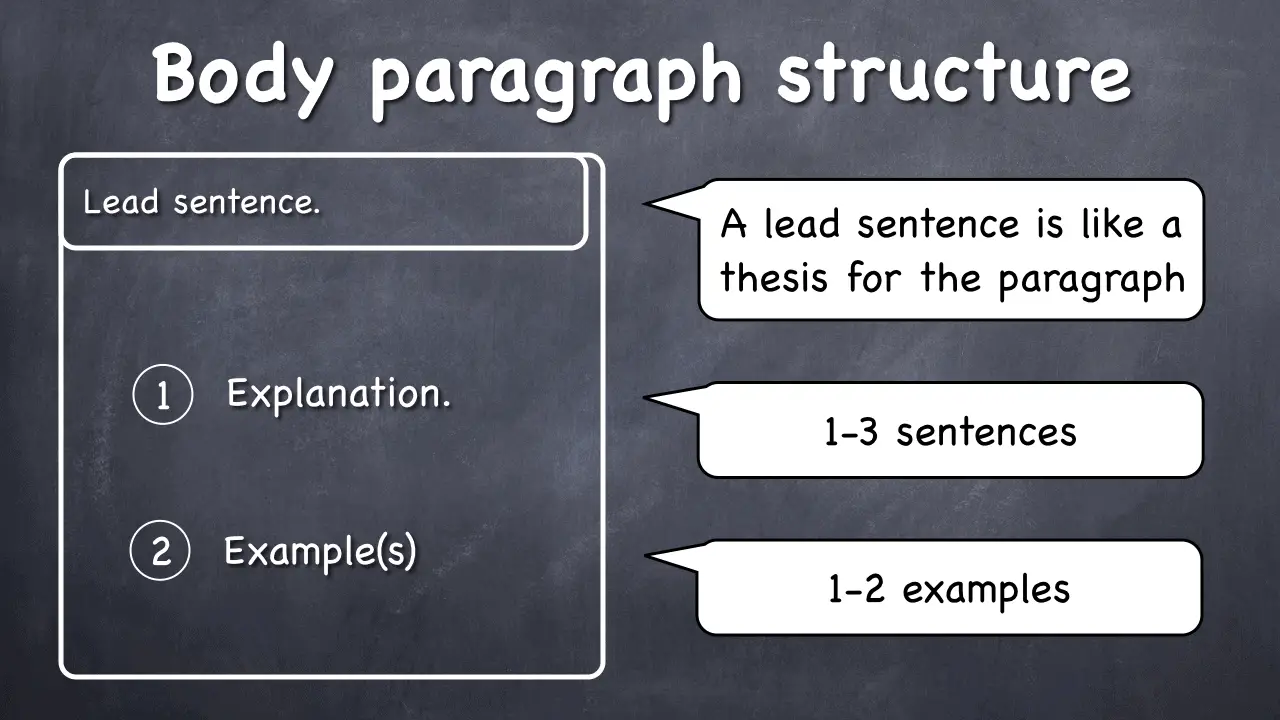

How to Use Lead Sentences to Improve Your Essay Writing

What are lead sentences and how do you use them to improve your essay writing?

Hi, I’m Tutor Phil, and if you’ve ever watched some of my other videos or read my blog at TutorPhil.com, then you probably have a pretty good idea of how to start writing an essay. You start out with a thesis stated clearly.

And how is a lead sentence related to a thesis? Put simply, a lead sentence is a sentence that opens and summarizes an essay, a section of an essay, or a paragraph perfectly.

I’d like to give you three examples of lead sentences – one for an entire essay, one for a section, and one for a paragraph.

Let’s say your professor wants you to write an essay about a movie. And you pick the movie “Titanic.”

Example of a Lead Sentence that Opens an Essay

Your lead sentence for the essay about the movie could be something like:

“Titanic is a very sad movie because it focuses on a relationship that ends tragically.”

This is a perfect lead sentence for this essay. At the same time this is also a perfect thesis.