- Privacy Policy

Education as a Social Institution

by kdkasi | Aug 3, 2023 | Social Institutions

Education as a Social Institution: Nurturing Minds and Shaping Societal Progress

Education is a fundamental social institution that plays a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ intellectual, social, and emotional development. In a sociological context, education is studied as a complex system of formal and informal institutions that impart knowledge, skills, and values to successive generations. This article explores the sociological significance of education as a social institution, examining its members, importance in society, roles, structure, impact on society, and essential functions that drive individual growth and contribute to societal progress.

Understanding Education as a Social Institution

- Definition: In sociology, education is defined as the process of acquiring knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes through formal schooling or informal learning experiences. It prepares individuals for active participation in society and the workforce.

- Members: Educational institutions consist of various members, including teachers, students, administrators, parents, and policymakers responsible for shaping educational policies.

Importance of Education in Society

- Human Capital: Education equips individuals with knowledge and skills, transforming them into productive and valuable human capital.

- Social Mobility: Education provides opportunities for social mobility, enabling individuals to improve their socio-economic status.

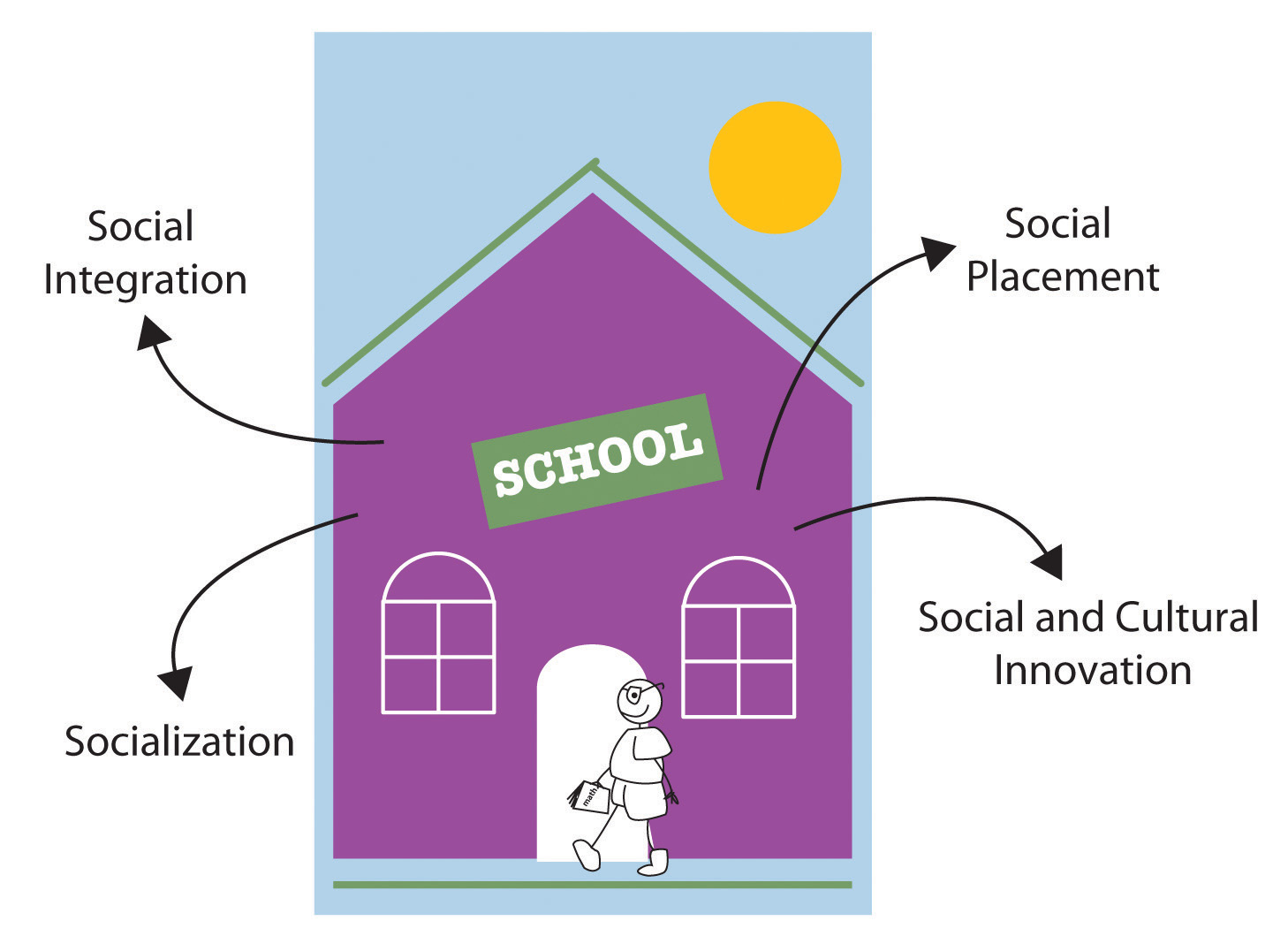

- Social Cohesion: Education fosters social cohesion by instilling common values and cultural knowledge, promoting social integration. Roles of Education in Society Socialization: Education is a primary agent of socialization, transmitting cultural values, norms, and societal expectations to new generations.

- Skill Development: Education imparts practical skills and knowledge that are essential for personal and professional development.

- Critical Thinking: Education fosters critical thinking, enabling individuals to analyze information and make informed decisions. Structure of Education Formal Education: Formal education takes place in schools, colleges, and universities with structured curricula and defined learning objectives.

- Informal Education: Informal education occurs outside the formal classroom setting, through experiences, interactions, and self-directed learning.

- Lifelong Learning: Lifelong learning emphasizes the continuous pursuit of knowledge and skills throughout one’s life. Impact of Education on Society Economic Growth: Education contributes to economic growth by fostering a skilled and innovative workforce.

- Social Progress: Education advances societal progress, enhancing healthcare, technology, and quality of life.

- Reduced Inequality: Education can reduce social inequalities by providing equal opportunities for all individuals to succeed. Functions of Education in Society Human Development: Education nurtures intellectual, emotional, and social development, empowering individuals to reach their potential.

- Cultural Transmission: Education transmits cultural heritage and knowledge to new generations, preserving societal values.

- Social Change: Education can drive social change by challenging norms, promoting social justice, and advocating for human rights.

In Conclusion , Education as a social institution is a bedrock of human progress, shaping individuals’ minds and driving societal development. In a sociological context, understanding the roles, importance, structure, and functions of education provides valuable insights into the dynamics of human learning and its impact on society.

Sociologists play a vital role in studying education, analyzing its impact on social mobility, cultural transmission, and economic growth. By recognizing the sociological significance of education, we can work towards promoting inclusive and equitable education systems that empower individuals and foster a more enlightened, innovative, and harmonious society.

The enduring role of education as a social institution reflects its profound influence on human civilization, molding future generations and shaping the trajectory of societies. Embracing the complexities of educational processes and advocating for accessible, quality education can contribute to creating more equitable and enlightened societies, where knowledge and learning are valued as tools for personal growth and collective progress.

By Khushdil Khan Kasi

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Enter your email address:

Delivered by FeedBurner

Recent Posts

- A Study of the Larger Mind" by Charles Horton Cooley

- Comte’s Three Stages of Society & Theory of Positivism

- The German Ideology by Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx

- Plato’s Theory of Education and Governance

- Nichomachean Ethics

- White Collar: The American Middle Classes

- Theory of Libertarianism

7.2 Education as a Social Institution

When you consider your COVID education story, it is likely that your education journey was interrupted in some way. You might have turned to YouTube to teach your second grader math. You might have needed a break and learned the latest dance step on Tik-Tok. All of us learn differently, and use many methods to figure things out.

The two minute video in figure 7.3 shows some of the ways that the Martu people of Australia hunt with fire. As you watch, please consider the following questions:

- Who is doing the hunting? Does this surprise you?

- What is the indigenous teaching around hunting and land stewardship?

- Using your imagination, how might this practice of hunting and stewardship be learned?

Figure 7.3. Fire Hunting in Australia [YouTube Video] (time: 2:01).

Traditionally, learning involves storytelling and practice. For the Martu people in Australia, the practices of hunting are taught by stories and experience. In this video, we see hunting practices using fire practiced by women who are hunting monitor lizards (figure 7.3). The women use controlled burns to catch and kill the lizards. In addition, the fire itself makes the landscape more useful for lizard habitat.

As a young person, you might learn about hunting by listening to the stories the hunters tell about the hunt that happened today. Or you might help skin the animals once they were caught. Today, the Martu also have access to schools, and can learn to read and write (Scelza n.d.), in addition to learning through lived experience..

When sociologists look at learning they are more likely to focus on the institution and inequality, in addition to interactions that may happen in the classroom. In this basic sociological definition education is a social institution through which members of a society are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms (Conerly et al. 2021). In this view, students learn not just reading and writing, but how to follow directions, and how to participate in social activities, even things as simple as standing in line.

As we’ve seen in other chapters in this book, education can be a driver of social change and a means of maintaining a status quo that does not serve everyone well. On one hand, education can be a cause of social change. For example, teaching girls to read and write is a component in decreasing poverty in many countries. In other circumstances education serves to reproduce structures of inequality. In the United States, families who are poor receive less access to quality education. How then are we to make sense of this complicated social institution?

7.2.1 Education and the Rise of Democracy

When we think about education as an institution, we consider the function that it serves in our society. According to the U.S. founding fathers, education served the function of creating responsible citizens. Like other revolutionaries of the time, they argued that if people could read and write, they could also decide for themselves. This idea of government serving at the will of the people, which was revolutionary at the time, depended on the people to make informed choices. In other words,

For America’s founders, public education was essential to keeping the republic. Thomas Jefferson famously proclaimed that of all the arguments for education, “none is more important, none more legitimate, than that of rendering the people safe, as they are the ultimate guardians of their own liberty.” (Neem 2019)

Creating a system of formal public education also served the function of stabilizing a new nation. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10 percent of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school, although others became apprentices (Urban and Wagoner 2008).

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to teach immigrants “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.

Free, compulsory education, of course, applied only to primary and secondary schools. Until the mid-1900s, very few people went to college, and those who did typically came from fairly wealthy families. After World War II, however, college enrollments soared, and today more people are attending college than ever before, even though college attendance is still related to social class, as we shall discuss later in this chapter.

An important theme emerges from this brief history: Until very recently in the record of history, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that boys who were not White and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all girls, whose education was supposed to take place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and, to some extent, gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

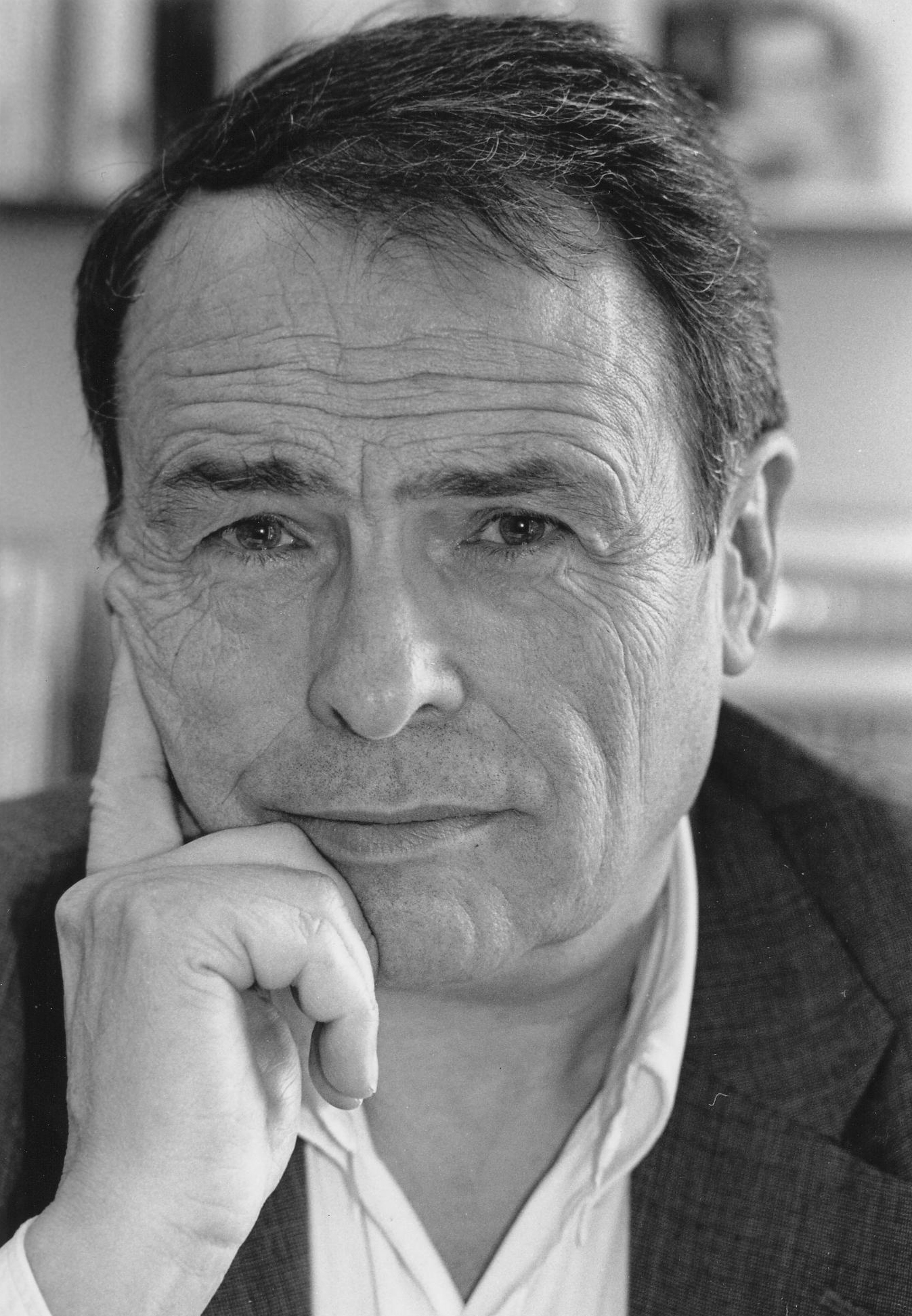

7.2.2 Pierrre Bourdieu: The Reproduction of Economic Inequality through Cultural and Social Capital

Functionalist sociologists focus on the purpose that education serves. As we learned in the last section, literacy can support democracy. Conflict sociologists, on the other hand, look at what maintains unequal social power. They particularly use social class as part of their analysis.

When we apply this lens to education, we see that the fulfillment of one’s education is closely linked to social class. Students of low socioeconomic status are generally not afforded the same opportunities as students of higher status, no matter how great their academic ability or desire to learn. Picture a student from a working-class home who wants to do well in school. On a Monday, he’s assigned a paper that’s due Friday. Monday evening, he has to babysit his younger sister while his divorced mother works. Tuesday and Wednesday, he works stocking shelves after school until 10:00 p.m. By Thursday, the only day he might have available to work on that assignment, he’s so exhausted he can’t bring himself to start the paper. His mother, though she’d like to help him, is so tired herself that she isn’t able to give him the encouragement or support he needs. And since English is her second language, she has difficulty with some of his educational materials. They also lack a computer and printer at home, which most of his classmates have, so they have to rely on the public library or school system for access to technology. As this story shows, many students from working-class families have to contend with helping out at home, contributing financially to the family, poor study environments and a lack of support from their families. This is a difficult match with education systems that adhere to a traditional curriculum that is more easily understood and completed by students of higher social classes.

Figure 7.4. Photo of Pierre Bourdieu

Such a situation leads to maintaining social class across generations, extensively studied by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (figure 7.4). He researched how cultural capital , or cultural knowledge that serves (metaphorically) as currency that helps us navigate a culture, alters the experiences and opportunities available to French students from different social classes. His results from France have been applied also to students in other countries. Members of the upper and middle classes have more cultural capital than do families of lower-class status. As a result, the educational system maintains a cycle in which the dominant culture’s values are rewarded. Instruction and tests cater to the dominant culture and leave others struggling to identify with values and competencies outside their social class. For example, there has been a great deal of discussion over what standardized tests such as the SAT really measure. Many argue that the tests group students by cultural ability rather than by natural intelligence.

The cycle of rewarding those who possess cultural capital is found in formal educational curricula as well as in the hidden curriculum, which refers to the type of nonacademic knowledge that students learn through informal learning and cultural transmission. This hidden curriculum reinforces the positions of those with higher cultural capital and serves to bestow status unequally.

Conflict theorists point to tracking , a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities. While educators may believe that students do better in tracked classes because they are with students of similar ability and may have access to more individual attention from teachers, conflict theorists feel that tracking leads to self-fulfilling prophecies in which students live up (or down) to teacher and societal expectations ( Education Week 2004).

To conflict theorists, schools play the role of training working-class students to accept and retain their position as lower members of society. They argue that this role is fulfilled through the disparity of resources available to students in richer and poorer neighborhoods as well as through testing (Lauen and Tyson 2008).

IQ tests have been attacked for being biased—for testing cultural knowledge rather than actual intelligence. For example, a test item may ask students what instruments belong in an orchestra. To correctly answer this question requires certain cultural knowledge—knowledge most often held by more affluent people who typically have more exposure to orchestral music. Though experts in testing claim that bias has been eliminated from tests, conflict theorists maintain that this is impossible. These tests, to conflict theorists, are another way in which education does not provide opportunities, but instead maintains an established configuration of power.

7.2.3 Violence and Oppression: Indian Residential Schools

As you might remember from Chapter 1 , though, we need to employ a more powerful equity lens to explore the institution of education. Already we see that even though our early politicians agreed that education was a requirement for country-building, many people were excluded. We notice that the institution serves the function of maintaining existing social classes. As we use our equity lens more powerfully, we see that the institution of education sometimes supports violent and oppressive social change. For this, we look at the history of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada, once described by the governments that funded them as Indian Residential Schools .

By establishing boarding schools for Indigenous children, colonizers committed genocide , the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. This is a strong claim, so let’s look at the evidence. In May 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report . The report details some of the basic facts. The United States established 408 Federal Indian Boarding Schools run between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws which required Indian parents to send their children to these boarding schools ( Newland 2022: 35). The explicit intention of the schools was to disrupt the families and the cultures of Indigenous people. Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022: 38). Because students were required to learn English and agriculture and punished if they spoke their Indigenous languages and practiced their own religious and spiritual practices, families and cultures were indeed destroyed.

Figure 7.5. Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior, first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary.

Deb Haaland (figure 7.5), the U.S. Secretary of the Interior and a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, describes this history in the following way:

>Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities. (Haaland 2021)

Secretary Haaland also recounts the suffering in her own family. She writes: “My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase ‘kill the Indian, and save the man,’ which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021). The 2022 U.S. Federal report documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021).

Figure 7.6. Photo of the Chemawa Indian School, Salem Oregon, no date.

The U.S. government forced hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children to attend Indian Residential Schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition n.d.). Oregon shares this painful history. Historian Eva Guggemos and volunteer historian SuAnn Reddick from Pacific University combed the historical record for the Forest Grove Indian Training School in Forest Grove, which became the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon (figure 7.6). They found that at least 270 children had died while at these schools. Most of these deaths were due to infectious diseases.

Even in cases where the children didn’t die, colonizers accomplished cultural hegemony , achieving authority, dominance, and influence of one group, nation, or society over another group, nation, or society; typically through cultural, economic, or political means. In this case, the colonizers valued their own White, European culture, and forced other groups to conform. These pictures in figure 7.7 and 7.8 tell a story of change and assimilation.

Figure 7.7. Caption from website: A group portrait of students from the Spokane tribe at the Forest Grove Indian Training School, taken when they were “new recruits.”

Figure 7.8 Caption from Website: Seven months later — the students pictured are probably the Spokane students who, according to the school roster, arrived in July 1881: Alice L. Williams, Florence Hayes, Suzette (or Susan) Secup, Julia Jopps, Louise Isaacs, Martha Lot, Eunice Madge James, James George, Ben Secup, Frank Rice, and Garfield Hayes.

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos in more detail:

A particularly poignant pair of photos in the Pacific University Archives vividly show what it meant for native youths to leave their families to come to Forest Grove. An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief. A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later, after the Spokane children had lived and worked for a time at the Indian Training School. In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck. Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove, said Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos, who has extensively studied the history of the Indian Training School. The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse. The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures. (Francis 2019)

The function of education in the case of Indian Boarding Schools doesn’t stop with cultural assimilation. Education functioned to purposefully disrupt families and cultures. Beyond that, the government policies and practices related to Indian education were part of a wider strategy of land acquisition. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous people would make land available for colonists. This is a concrete example of land grabbing, a practice you learned about in Chapter 4 . Jefferson wrote,

>To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts (Jefferson 1803, quoted in Newland 2022:21).

By removing people from the land, and children from families, the US Government made the land available to colonists, who were mainly from Europe, an indirect but purposeful function of education.

7.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Education as a Social Institution

“Education as a Social Institution” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Education and the Rise of Democracy, partially based on Social Problems Continuity and Change – An Overview of Education https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_social-problems-continuity-and-change/s14-01-an-overview-of-education-in-th.html University of Minnesota Licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 lightly edited

Pierre Bourdeau: Credentialism/Cultural Capital

Introduction to Sociology 3e – Theoretical Perspectives on Education

CC-BY 4.0 lightly edited

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/16-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-education

Figure 7.3. Figure Hunting In Australia. https://youtu.be/j8zb44roDTM

Figure 7.4. Pierre Bourdieu Bernard Lambert, own work, CC-BY-SA 4.0 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Bourdieu#/media/File:Pierre_Bourdieu_(1).jpg

Figure 7.5. Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Deb_Haaland_official_portrait,_116th_congress_2.jpg U.S. House Office of Photography 2019 Public Domain

Figure 7.6. Chemawa Indian School https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/or0051.photos.130102p/resource/ Public Domain

Figure 7.7. https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/tragic-collision-cultures Public Domain

Figure 7.8. . https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/tragic-collision-cultures Public Domain

Social Change in Societies Copyright © by Aimee Samara Krouskop. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

The Sociology of Education

Studying the Relationships Between Education and Society

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

The sociology of education is a diverse and vibrant subfield that features theory and research focused on how education as a social institution is affected by and affects other social institutions and the social structure overall, and how various social forces shape the policies, practices, and outcomes of schooling .

While education is typically viewed in most societies as a pathway to personal development, success, and social mobility, and as a cornerstone of democracy, sociologists who study education take a critical view of these assumptions to study how the institution actually operates within society. They consider what other social functions education might have, like for example socialization into gender and class roles, and what other social outcomes contemporary educational institutions might produce, like reproducing class and racial hierarchies, among others.

Theoretical Approaches within the Sociology of Education

Classical French sociologist Émile Durkheim was one of the first sociologists to consider the social function of education. He believed that moral education was necessary for society to exist because it provided the basis for the social solidarity that held society together. By writing about education in this way, Durkheim established the functionalist perspective on education . This perspective champions the work of socialization that takes place within the educational institution, including the teaching of society’s culture, including moral values, ethics, politics, religious beliefs, habits, and norms. According to this view, the socializing function of education also serves to promote social control and to curb deviant behavior.

The symbolic interaction approach to studying education focuses on interactions during the schooling process and the outcomes of those interactions. For instance, interactions between students and teachers, and social forces that shape those interactions like race, class, and gender, create expectations on both parts. Teachers expect certain behaviors from certain students, and those expectations, when communicated to students through interaction, can actually produce those very behaviors. This is called the “teacher expectancy effect.” For example, if a white teacher expects a Black student to perform below average on a math test when compared to white students, over time the teacher may act in ways that encourage Black students to underperform.

Stemming from Marx's theory of the relationship between workers and capitalism, the conflict theory approach to education examines the way educational institutions and the hierarchy of degree levels contribute to the reproduction of hierarchies and inequalities in society. This approach recognizes that schooling reflects class, racial, and gender stratification, and tends to reproduce it. For example, sociologists have documented in many different settings how "tracking" of students based on class, race, and gender effectively sorts students into classes of laborers and managers/entrepreneurs, which reproduces the already existing class structure rather than producing social mobility.

Sociologists who work from this perspective also assert that educational institutions and school curricula are products of the dominant worldviews, beliefs, and values of the majority, which typically produces educational experiences that marginalize and disadvantage those in the minority in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability, among other things. By operating in this fashion, the educational institution is involved in the work of reproducing power, domination, oppression, and inequality within society . It is for this reason that there have long been campaigns across the U.S. to include ethnic studies courses in middle schools and high schools, in order to balance a curriculum otherwise structured by a white, colonialist worldview. In fact, sociologists have found that providing ethnic studies courses to students of color who are on the brink of failing out or dropping out of high school effectively re-engages and inspires them, raises their overall grade point average and improves their academic performance overall.

Notable Sociological Studies of Education

- Learning to Labour , 1977, by Paul Willis. An ethnographic study set in England focused on the reproduction of the working class within the school system.

- Preparing for Power: America's Elite Boarding Schools , 1987, by Cookson and Persell . An ethnographic study set at elite boarding schools in the U.S. focused on the reproduction of the social and economic elite.

- Women Without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity , 2003, by Julie Bettie. An ethnographic study of how gender, race, and class intersect within the schooling experience to leave some without the cultural capital necessary for social mobility within society.

- Academic Profiling: Latinos, Asian Americans, and the Achievement Gap , 2013, by Gilda Ochoa. An ethnographic study within a California high school of how race, class, and gender intersect to produce the "achievement gap" between Latinos and Asian Americans.

- Introduction to Sociology

- Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge

- The Sociology of Gender

- The Sociology of Social Inequality

- The Sociology of the Family Unit

- Sociology Of Religion

- The Sociology of Consumption

- All About Marxist Sociology

- The Sociology of Race and Ethnicity

- Definition of Self-Fulfilling Prophecy in Sociology

- Definition of Systemic Racism in Sociology

- Theories of Ideology

- Biography of Patricia Hill Collins, Esteemed Sociologist

- Feminist Theory in Sociology

- What You Need to Know About Economic Inequality

- Understanding the Sociological Perspective

16.1 Education around the World

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Identify differences in educational resources around the world

- Describe the concept of universal access to education

Education is a social institution through which members of a society are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. Every nation in the world is equipped with some form of education system, though those systems vary greatly. The major factors that affect education systems are the resources and money that are utilized to support those systems in different nations. As you might expect, a country’s wealth has much to do with the amount of money spent on education. Countries that do not have such basic amenities as running water are unable to support robust education systems or, in many cases, any formal schooling at all. The result of this worldwide educational inequality is a social concern for many countries, including the United States.

International differences in education systems are not solely a financial issue. The value placed on education, the amount of time devoted to it, and the distribution of education within a country also play a role in those differences. For example, students in South Korea spend 220 days a year in school, compared to the 180 days a year of their United States counterparts (Pellissier 2010).

Then there is the issue of educational distribution and changes within a nation. The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is administered to samples of fifteen-year-old students worldwide. In 2010, the results showed that students in the United States had fallen from fifteenth to twenty-fifth in the rankings for science and math (National Public Radio 2010). The same program showed that by 2018, U.S. student achievement had remained on the same level for mathematics and science, but had shown improvements in reading. In 2018, about 4,000 students from about 200 high schools in the United States took the PISA test (OECD 2019).

Analysts determined that the nations and city-states at the top of the rankings had several things in common. For one, they had well-established standards for education with clear goals for all students. They also recruited teachers from the top 5 to 10 percent of university graduates each year, which is not the case for most countries (National Public Radio 2010).

Finally, there is the issue of social factors. One analyst from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the organization that created the PISA test, attributed 20 percent of performance differences and the United States’ low rankings to differences in social background. Researchers noted that educational resources, including money and quality teachers, are not distributed equitably in the United States. In the top-ranking countries, limited access to resources did not necessarily predict low performance. Analysts also noted what they described as “resilient students,” or those students who achieve at a higher level than one might expect given their social background. In Shanghai and Singapore, the proportion of resilient students is about 70 percent. In the United States, it is below 30 percent. These insights suggest that the United States’ educational system may be on a descending path that could detrimentally affect the country’s economy and its social landscape (National Public Radio 2010).

Big Picture

Education in finland.

With public education in the United States under such intense criticism, why is it that Singapore, South Korea, and especially Finland (which is culturally most similar to us), have such excellent public education? Over the course of thirty years, the country has pulled itself from among the lowest rankings by the Organization of Economic Cooperation (OEDC) to first in 2012, and remains, as of 2014, in the top five. Contrary to the rigid curriculum and long hours demanded of students in South Korea and Singapore, Finnish education often seems paradoxical to outside observers because it appears to break a lot of the rules we take for granted. It is common for children to enter school at seven years old, and children will have more recess and less hours in school than U.S. children—approximately 300 less hours. Their homework load is light when compared to all other industrialized nations (nearly 300 fewer hours per year in elementary school). There are no gifted programs, almost no private schools, and no high-stakes national standardized tests (Laukkanen 2008; LynNell Hancock 2011).

Prioritization is different than in the United States. There is an emphasis on allocating resources for those who need them most, high standards, support for special needs students, qualified teachers taken from the top 10 percent of the nation's graduates and who must earn a Master's degree, evaluation of education, balancing decentralization and centralization.

"We used to have a system which was really unequal," stated the Finnish Education Chief in an interview. "My parents never had a real possibility to study and have a higher education. We decided in the 1960s that we would provide a free quality education to all. Even universities are free of charge. Equal means that we support everyone and we’re not going to waste anyone’s skills." As for teachers, "We don’t test our teachers or ask them to prove their knowledge. But it’s true that we do invest in a lot of additional teacher training even after they become teachers" (Gross-Loh 2014).

Yet over the past decade Finland has consistently performed among the top nations on the PISA. Finland’s school children didn’t always excel. Finland built its excellent, efficient, and equitable educational system in a few decades from scratch, and the concept guiding almost every educational reform has been equity. The Finnish paradox is that by focusing on the bigger picture for all, Finland has succeeded at fostering the individual potential of most every child.

“We created a school system based on equality to make sure we can develop everyone’s potential. Now we can see how well it’s been working. Last year the OECD tested adults from twenty-four countries measuring the skill levels of adults aged sixteen to sixty-five on a survey called the PIAAC (Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies), which tests skills in literacy, numeracy, and problem solving in technology-rich environments. Finland scored at or near the top on all measures.”

Formal and Informal Education

As already mentioned, education is not solely concerned with the basic academic concepts that a student learns in the classroom. Societies also educate their children, outside of the school system, in matters of everyday practical living. These two types of learning are referred to as formal education and informal education.

Formal education describes the learning of academic facts and concepts through a formal curriculum. Arising from the tutelage of ancient Greek thinkers, centuries of scholars have examined topics through formalized methods of learning. Education in earlier times was only available to the higher classes; they had the means for access to scholarly materials, plus the luxury of leisure time that could be used for learning. The Industrial Revolution and its accompanying social changes made education more accessible to the general population. Many families in the emerging middle class found new opportunities for schooling.

The modern U.S. educational system is the result of this progression. Today, basic education is considered a right and responsibility for all citizens. Expectations of this system focus on formal education, with curricula and testing designed to ensure that students learn the facts and concepts that society believes are basic knowledge.

In contrast, informal education describes learning about cultural values, norms, and expected behaviors by participating in a society. This type of learning occurs both through the formal education system and at home. Our earliest learning experiences generally happen via parents, relatives, and others in our community. Through informal education, we learn important life skills that help us get through the day and interact with each other, including how to dress for different occasions, how to perform regular tasks such as shopping for and preparing food, and how to keep our bodies clean. Many professional tasks and local customs are learned informally, as well.

Cultural transmission refers to the way people come to learn the values, beliefs, and social norms of their culture. Both informal and formal education include cultural transmission. For example, a student will learn about cultural aspects of modern history in a U.S. History classroom. In that same classroom, the student might learn the cultural norm for asking a classmate out on a date through passing notes and whispered conversations.

Access to Education

Another global concern in education is universal access . This term refers to people’s equal ability to participate in an education system. On a world level, access might be more difficult for certain groups based on class or gender (as was the case in the United States earlier in the nation’s history, a dynamic we still struggle to overcome). The modern idea of universal access arose in the United States as a concern for people with disabilities. In the United States, one way in which universal education is supported is through federal and state governments covering the cost of free public education. Of course, the way this plays out in terms of school budgets and taxes makes this an often-contested topic on the national, state, and community levels.

A precedent for universal access to education in the United States was set with the 1972 U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia’s decision in Mills v. Board of Education of the District of Columbia . This case was brought on the behalf of seven school-age children with special needs who argued that the school board was denying their access to free public education. The school board maintained that the children’s “exceptional” needs, which included intellectual disabilities, precluded their right to be educated for free in a public school setting. The board argued that the cost of educating these children would be too expensive and that the children would therefore have to remain at home without access to education.

This case was resolved in a hearing without any trial. The judge, Joseph Cornelius Waddy, upheld the students’ right to education, finding that they were to be given either public education services or private education paid for by the Washington, D.C., board of education. He noted that

Constitutional rights must be afforded citizens despite the greater expense involved … the District of Columbia’s interest in educating the excluded children clearly must outweigh its interest in preserving its financial resources. … The inadequacies of the District of Columbia Public School System whether occasioned by insufficient funding or administrative inefficiency, certainly cannot be permitted to bear more heavily on the “exceptional” or handicapped child than on the normal child ( Mills v. Board of Education 1972).

Today, the optimal way to include people with disabilities students in standard classrooms is still being researched and debated. “Inclusion” is a method that involves complete immersion in a standard classroom, whereas “mainstreaming” balances time in a special-needs classroom with standard classroom participation. There continues to be social debate surrounding how to implement the ideal of universal access to education.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/16-1-education-around-the-world

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Sociology of Education: Meaning, Scope, Importance, Perspectives

Synopsis : This article explores the discipline of Sociology of Education, a branch of the broader subject of Sociology, through its meaning, history of development, significance, differences with Educational Sociology, and scope. It also portrays how education can be examined using the three main theoretical perspectives in sociology.

What is Sociology of Education ?

To understand what Sociology of Education comprises, it is, first and foremost, imperative to define education from a sociological understanding. In sociology, education is held to be a social institution that serves the objective of socializing an individual from their very birth into the systems of society. Henslin (2017) defines education as “a formal system” which engages in imparting knowledge to individuals, instilling morals and beliefs (which are at par with those of the culture and society), and providing formal training for skill development. In non-industrial, simple societies, the specific institution of education did not exist in society.

For quite a long period after it was established as a formal means of knowledge development, education was available only to those privileged enough to afford it. Requirements under industrialization to have literate workers for some jobs reshaped the structure of the education system to a great extent. Even in today’s world, the education system varies from one country to another due to various factors, ranging from cultural values to the availability of proper resources.

Sociology of Education is the discipline or field of study which deals with the institution of education, and all the other factors related to it, in society. Sociology of education is also defined as the academic discipline which “examines the ways in which individuals’ experiences affect their educational achievement and outcomes” (Williams, 2011). Scott (2014) states that the subject is “mostly concerned with schooling, and especially the mass schooling systems of modern industrial societies, including the expansion of higher, further, adult, and continuing education.”

In simple words, the discipline studies education as a social institution, and examines its functions, roles, and other behaviors within the broader social context, as well as how it influences individuals and is influenced reciprocally by them. It highlights the significance of education within the different cultures and other social groups, as well as assesses factors (such as economic, political, etc.) associated with the individuals which might affect their access to education. Some themes discussed within the field are modules or curriculum, testing methods (such as standardized testing), etc.

Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Lancelot Hogben, Talcott Parsons , Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, John Wilfred Meyer, etc., are some scholars associated with the Sociology of Education. The discipline was made popular in India by scholars such as Madhav Sadashiv Gore, Akshay Ramanlal Desai, Yogendra Singh, and Shyama Charan Dube, among others (Pathania, 2013).

Historical Background:

French sociologist Emile Durkheim was the person who helped establish Sociology as a formal educational discipline. Durkheim also became the first professor of sociology, the first individual to pursue a sociological understanding of the functioning of societies, and the foremost person to initiate a discussion on the sociology of education (Boronski & Hassan, 2020). He identified that the base of organic solidarity is moral education, in which self-discipline and keeping one’s desires in check are the essential principles of moral development.

However, even before sociology emerged as a formal academic discipline or pursued interest in the West, Arab philosopher and historian Ibn Khaldun has been designated the position of being one of the pioneer thinkers in Sociology, and in the sociology of education in particular. Khaldun understood education as a tool of significance, the advancement of which is crucial to the growth and development of society and economy (Boronski & Hassan, 2020).

With the advent of the Fabian Society, which was originally established in 1884, during the middle of the twentieth century, sociology of education began in its early stage in Britain.

Boronski & Hassan (2020) describe the Fabian society and its activities as the “political foundation” of the sociology of education in Britain. The methodology followed during this time was ‘political arithmetic’: examining the capability of education to result in a society that was more supportive of and characterized by democracy, and its related principles.

The intellectual roots of sociology of education in Britain lie in the influence of structural functionalism, strongly visible in both Britain and America. The British sociology of education saw a drastic shift to a more critical view of education during the 1970s and 1980s. This was termed as “New Sociology of Education (NSOE)”, which consisted of not one, but several different approaches to education, all of which, however, had a similar base: the system or institution of education was considered as fundamentally adverse to those belonging from the working class (Boronski & Hassan, 2020).

The feminist perspective of sociology grew apace in the education scenario, providing a bolder and enhanced voice to the agenda of the women’s movement, and literature on the same, such as those of Dale Spencer and Judy Samuel, also expanded. Today, the field of Sociology itself, and in particular, the sub-field of Sociology of Education faces a continuous and increasing demand to make the discipline more embracive by facilitating and encouraging the incorporation of involvement of the global South.

Theoretical Perspectives on Education :

The social institution of education can be examined using the three main theoretical perspectives in Sociology:

- Structural Functionalism : This perspective views education as a crucial and integral institution that provides several benefits to society (Henslin, 2017). The first manifest function of education is providing a source of knowledge and teaching essential aptitude, required both for social survival and economic necessities. Standardized testing scores help employers discern and select the ‘good’ potential workers from the ‘bad’ wherever there is a lack of prior knowledge about each of them.

The second function is facilitating distribution or passing on of core cultural values, norms, beliefs, ideals, as well as patriotic feelings towards one’s country, and harmony towards fellow citizens. These are passed on from generation to generation to ensure that these values are kept intact.

“Social integration”, that is, feelings of solidarity towards other people due to sharing the same nationality as them, the inclusion of people with special needs, etc., is the third manifest function of education (Henslin, 2017). At the same time, it also serves the function of separating people into ‘appropriate’ groups based on differences in their characteristics (such as merit, skills, etc.).

Other functions vary from place to place and include providing childcare, providing nutrition (free midday meal systems), facilitating sex education and proper healthcare, diminishing the rate of unemployment, as well as ensuring security in society by keeping individuals in schools and away from corrupt activities (Henslin, 2017).

- Symbolic Interactionism : This perspective focuses on the interaction taking place in schools–in classrooms, playgrounds, etc., between students and teachers, and among students themselves, and how these can affect the individuals involved in the interactions. Socialization into gender roles is a primary example of the influence of in-school interaction upon individuals. Teachers’ expectations, type of peer groups, etc., have an impact on the performance of students (higher the teacher’s expectations, the better the students will perform, and vice versa) (Henslin, 2017). Expectations of students oneself based on their life situations (such as financial conditions) also affect an individual’s educational performance.

- Conflict Theory : This theoretical perspective is inherently skeptical and critical of the education system. According to conflict theorists, education serves the purpose of introducing, reiterating, and maintaining the class division which is present in society. They posit the presence of a “hidden curriculum” which instills values such as submission to power or authority, adherence to social or cultural rules (such as maintenance of racial discrimination, treating students from different social classes differently), etc. (Henslin, 2017).

Also Read: Maxist Perspective on Education

By implementing some latent and some visible rules, schools also promote the current social structures (such as capitalism: by encouraging competitive behavior and pitting students against one another based on test scores, social stratification: regions having lower-class students have poorly funded schools, etc.), thereby facilitating their existence rather than working towards their removal from society.

Other theoretical perspectives which have had a significant impact on how education, and the system around it, is analyzed are feminist approaches, which highlight the gender differences in education, with the third wave of feminism also incorporating race and class-based discriminations into the gender imbalance; and critical race theory which focuses on all matters concerning race (mainly the obstacles which people have to encounter due to race) in education (Robson, 2019).

Scope of Sociology of Education :

Sociology of Education covers a wide range of topics. Society and all other components within it, such as culture, class, race, gender, etc., the ongoing processes of socialization, acculturation, social organization, etc., and other factors such as status, roles, values, morals, etc., all fall under the inspection of this field of study (Satapathy, n.d.). Aligning the design of education according to geographical, ethnic, and linguistic necessities, and requirements of other population subgroups also falls under Sociology of Education. How economic background and situations, family structures and relations, friends, peer groups and teachers, and other more overarching social issues affect the personality, quality of education, and accessibility of opportunities to students is an integral point of consideration under Sociology of Education.

Significance of Studying Sociology of Education :

Dynamic nature of culture, the fact that culture varies from one place to another and sometimes even within the same region, and because education, culture, and society affect each other drastically, it is important to have an understanding of the relationship between these so that education can be used effectively as a tool for human advancement (Satapathy, n.d.). Sociology of Education helps in facilitating that.

Teachers are able to learn cultural differences, practice cultural relativism , understand how differences in culture translate into the educational sphere as well, and work towards providing individuals equitable opportunities for education through the Sociology of Education (Ogechi, 2011). They can also motivate the same knowledge among students. As a discipline, Sociology of Education instills cultural appreciation, respect, and admiration towards diversity, and more in-depth knowledge about different cultures and other social groups through the patterns in education within them.

Sociology of Education also provides greater knowledge about human behavior, clarity on how people organize themselves in society and helps unravel and simplify the complexities within human society (Ogechi, 2011). Because education, whether in the formal, institutionalized form or otherwise, is one of the few components in human society which more or less remains constant across cultures, it becomes an important tool to analyze and interpret human societies.

The discipline also enhances one’s understanding of the position education occupies in society, and the roles it plays in the lives of humans (Ogechi, 2011). At the same time, it helps develop knowledge about the benefits as well as the shortcomings of education and devise policies to make the institution more beneficial for society by facilitating an analytical examination.

Due to its focus on studying one of the most vital parts of human lives today, the academic field of Sociology of Education holds a position of great importance among the several branches and sub-branches of sociology. The discipline is constantly evolving, and undergoing improvement and changes as the society, and the values held by it change.

Differences between Educational Sociology and Sociology of Education :

Although the two are related, Sociology of Education is distinctly different from Educational Sociology in certain factors. Sociology of education is the process of scientifically investigating the institution of education within the society–how the society affects it, how education influences people in the society in return, and the problems which might occur as a result of the interaction between the two (Chathu, 2017). Educational Sociology also deals with these, but where Sociology of Education is a more theory-based study, Educational Sociology focuses on applying principles in sociology to the entire system of education and how it operates within the society. In other words, Sociology of Education studies the practices within the social institution of education using sociological concepts, while Educational Sociology engages in the practical application of understandings developed through sociological research into education (Bhat, 2016).

In the same context, Sociology of Education views education as a part of the larger society, and hence the institution is analyzed both as a separate unit, as well as by considering it alongside other factors in society (Bhat, 2016). Therefore, the discipline tries to form a relationship between education and other facets of society and seeks to understand how education affects these different components of the society, and vice versa (for example, how education ingrains gender roles, as well as how pre-existing gender roles affect the quality, quantity, availability, and access to education). Educational Sociology, on the other hand, aims to provide solutions to the problems which occur in education (Bhat, 2016). In doing so, the discipline views education as a separate entity within society.

Sociology of Education tends to strive towards developing an understanding of how the education system affects individuals, and what outcomes are visible in people as a result of education (Chathu, 2017). Educational Sociology, on the other hand, strives to find ways of improving the institution and system of education so that its potentials can be more advantageously harnessed for the greater interest of all in the future.

Bhat, M. S. (2016). EDU-C-Sociological foundations of education-I . https://www.cukashmir.ac.in/departmentdocs_16/Education%20&%20Sociology%20-%20Dr.%20Mohd%20Sayid%20Bhat.pdf

Boronski, T., & Hassan, N. (2020). Sociology of education (2nd ed.). Editorial: Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington Dc, Melbourne Sage.

Chathu. (2017, January 30). Difference between educational sociology and sociology of education | definition, features, characteristics . Pediaa.com. https://pediaa.com/difference-between-educational

Ogechi, R. (2011). QUESTION: Discuss the importance of sociology of education to both teachers and students. Academia . https://www.academia.edu/37732576/QUESTION_Discuss_the_importance_

Pathania, G. J. (2013). Sociology of Education. Economic and Political Weekly , 48 (50), 29–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24479041

Robson, K. L. (2019). Theories in the sociology of education. In Sociology of Education in Canada . Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/robsonsoced/chapter/__unknown__-2/

Satapathy, S. S. (n.d.). Sociology of education . https://ddceutkal.ac.in/Syllabus/MA_SOCIOLOGY/Paper-16.pdf

Scott, J. (2014). A dictionary of sociology (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Williams, S. M. (2011). Sociology of education. Education . https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0065

Soumili is currently pursuing her studies in Social Sciences at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, focusing on core subjects such as Sociology, Psychology, and Economics. She possesses a deep passion for exploring various cultures, traditions, and languages, demonstrating a particular fascination with scholarship related to intersectional feminism and environmentalism, gender and sexuality, as well as clinical psychology and counseling. In addition to her academic pursuits, her interests extend to reading, fine arts, and engaging in volunteer work.

Search NYU Steinhardt

Education as a social institution.

This course considers the role of education as a social institution and the ways in which it fosters, prevents, and maintains social inequities in the U.S. We examine the structural and cultural ways in which schools have played a role in building and sustaining social hierarchies and shaped the character of our society. We explore how schooling socializes students differently based on their real/perceived culture, race, class, gender, sexual identity, and immigrant status and how that leads to differential outcomes for different groups. Students explore the origins, development, and current state of social theory and practice/research on education.

Social Institutions (Definition + 7 Examples)

Welcome to this in-depth look at social institutions! These foundational aspects of our lives shape the way we interact, learn, and grow, often without us even realizing it. They are the building blocks of society, impacting everything from our individual roles to the way communities function.

Social institutions are organized systems or structures within a society that work together to meet the needs of its members. These can include family, education, government, and many more. They help to maintain order, shape behavior, and provide frameworks for cooperation.

In this article, we'll explore the various types of social institutions, delve into key theories that help us understand them, and look at how they affect our everyday lives. So, whether you're a student looking for some extra information or an adult wanting to understand society a little better, read on to get a comprehensive understanding of this crucial subject.

What are Social Institutions?

So, let's get started by clarifying what we mean when we talk about social institutions. Social institutions are like the "rules" and "teams" that help our society work smoothly.

Think of them as organized systems that people have created to help solve problems and meet the needs of the community. For example, families take care of kids and schools help people learn important skills.

Brief Historical Background

Now, social institutions haven't just popped up overnight. They have a history that goes way back. If you've ever heard of cave people, you'll know that even they had a basic form of social institutions. They had family groups, leaders, and even rules about sharing food and other resources.

As societies became more complex, so did these institutions. Fast forward to ancient civilizations like Egypt, Greece, or China, and you'll see even more complex systems involving government, religion, and trade.

In the modern world, these institutions have continued to evolve, reflecting the needs and technologies of the times.

Importance in a Functioning Society

You might be asking, "Why are these social institutions so important?" Well, they're kind of like the glue that holds society together. They make sure people have a way to resolve conflicts, learn new things, and take care of each other.

For instance, without a legal system, it would be hard to solve disagreements peacefully. Without schools, learning would be a haphazard process. And without families or other support networks, individuals might find it really tough to survive and be happy.

So, understanding social institutions is a lot like understanding the rules of a game; it helps you know what's happening, why it's happening, and how you can be a part of it. In the next sections, we will take a closer look at specific types of social institutions and dig deeper into how they make our world what it is.

The History of Social Institutions

Understanding the history of social institutions gives us a "time machine" of sorts, allowing us to see how these important building blocks of society have changed over time. Let's take a historical journey to explore the development and transformation of various social institutions.

Prehistoric Societies

Let's start at the beginning—the very beginning. In prehistoric times, human societies were mainly hunter-gatherer communities. The concept of "family" was crucial even back then.

The family was not just a social unit but a survival unit. Groups of families might come together to form tribes, another rudimentary social institution that helped with hunting, gathering, and protection.

Ancient Civilizations

Fast forward a bit, and we arrive at the era of ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Greece. Each had its own set of intricate social institutions that went far beyond the family and tribe.

In Mesopotamia, for example, the Code of Hammurabi —one of the earliest sets of laws—helped establish a justice system.

In Egypt, the institution of the monarchy was closely linked with religious institutions, with the Pharaoh often considered a god-king.

Religion itself became a social institution with the dawn of organized belief systems. For example, in ancient China, Confucianism wasn't just a religion; it was a social doctrine that influenced family life, education, and governance.

In Greece, the institution of democracy gave rise to the early forms of what we now know as government.

Middle Ages to Renaissance

Let's leap ahead again, this time to the Middle Ages. This period saw significant changes in social institutions, especially in Europe.

The church became an incredibly powerful institution, sometimes even surpassing the power of kings and queens. Feudalism shaped economic and social structures, establishing rigid classes of lords, vassals, and serfs.

However, during the Renaissance, there was a dramatic shift. New ideas about individualism, science, and art challenged existing social norms . The invention of the printing press led to the spread of knowledge and laid the groundwork for the future institution of mass media.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was another turning point. The societal shift from agrarian communities to industrial urban centers brought about new social institutions.

For instance, factories became the new workplaces, replacing farms and home-based businesses. This also gave rise to labor unions, a new type of social institution focused on workers' rights.

Public education evolved as an institution during this period as well, especially with the advent of compulsory schooling laws. Suddenly, education wasn't just for the elite; it was for everyone, at least in theory.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, we've seen the advent of even more social institutions, or at least significant modifications to existing ones.

Think about how the internet has transformed media, turning it into a digital playground where anyone can be a broadcaster.

Government institutions have adapted to an increasingly globalized world, leading to the formation of international organizations like the United Nations.

Healthcare has also evolved into a complex institution, with advancements in medicine turning what used to be fatal diseases into manageable conditions. Systems of healthcare vary from country to country, from private healthcare markets in the United States to single-payer systems in countries like Canada.

Reflections

Looking back, it's amazing to see how far social institutions have come. From rudimentary family and tribal systems to intricate networks of governance, media, and healthcare, these structures have continually adapted to meet society's changing needs.

Understanding this history helps us appreciate the flexibility and resilience of social institutions. It also highlights the fact that these institutions are human-made, and thus can be changed and improved as society evolves.

The history of social institutions isn't just a look back in time; it's a roadmap that can help us navigate the complexities of today's world and make informed decisions for the future.

Types of Social Institutions

When you hear the word "family," what comes to mind? For most of us, it might be our parents, siblings, or maybe our extended family like grandparents, aunts, and uncles.

Family as a social institution is the foundational unit of society that serves multiple purposes, like emotional support, raising children, and providing a basic social framework. It's like the starting point in a person's life, where you learn your first words, behaviors, and values.

Historical Context

The concept of family has been around since the dawn of human civilization. In prehistoric times, family structures were more about survival. Families hunted and gathered food together, offering protection against the harsh world outside.

As we moved to agrarian societies, families became units of labor and economic production. In medieval times, family lines were vital for social standing, often influencing your profession and even who you could marry.

In more recent history, industrialization led to the 'nuclear family,' as people moved away from extended families to work in cities. Today, families are even more diverse, ranging from single-parent households to blended families, to families of choice that may not even include blood relatives.

Why does family matter? Well, think about it like your first "classroom" or "support group." It's where you learn basic skills like talking and walking, but also values like sharing and kindness.

Families also serve as a safety net. If you're going through tough times, family members are often the ones who support you emotionally and sometimes financially. The family is also important for society because it's where the next generation learns the norms and values they'll carry into adulthood.

If families are strong, it sets a positive ripple effect for the community at large.

Let's look at some different examples to see how the family institution varies. The "nuclear family," consisting of two parents and their children, is often considered the standard, especially in Western societies.

However, this is just one version of family. "Extended families," which include grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, are common in many cultures and offer a broader support network.

Single-parent families are increasingly common, challenging the notion that you need two parents for a functional family unit. Then there are "blended families" where one or both parents bring children from previous relationships into a new family setup.

Some cultures have even more unique family structures. In some Middle Eastern cultures, polygamous families, where a man has multiple wives, are accepted.

In certain Native American cultures, "Two-Spirit" individuals serve unique family roles that don't fit neatly into standard Western categories of male or female.

There are also "chosen families," groups of unrelated individuals who commit to supporting and caring for one another. This can often be found in marginalized communities, where biological families might be unsupportive or absent.

2) Education

Education is more than just what we learn in school; it's a social institution that helps individuals develop the knowledge, skills, and character they need to become functioning members of society.

In essence, education serves as society's "training ground" for both academic and social learning.

The idea of formal education isn't as old as you might think. In ancient times, education was usually limited to wealthy families and often involved a one-on-one mentorship system. With the rise of ancient civilizations like Greece, the idea of education began to evolve.

The Greeks were among the first to have a more formal system of education that included schools, although these were still mainly for the wealthy. During the Middle Ages, education was primarily provided by religious institutions.

Fast forward to the industrial revolution, and mass education became the norm. Schools became standardized, and public education was established to provide learning for everyone, not just the rich.

Nowadays, education is seen as a universal right, and various systems exist worldwide, from public to private to homeschooling setups.

Why is education so crucial? For starters, it equips people with the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in life. But it goes beyond that. Education is the institution through which we learn about our history, our culture, and even about how to interact with other people.

A strong educational system can help to reduce inequality, improve economic prospects, and create more engaged citizens. It's not just about reading, writing, and arithmetic; it's about shaping the kind of society we want to live in.

To grasp the breadth of the education institution, consider its various forms. In the United States, public schools serve as the backbone of the educational system, funded by taxpayer dollars and available to all children.

Private schools offer an alternative, often with specialized curricula or smaller class sizes, but they come at a cost.

Charter schools, another variant, operate with greater freedom in terms of curriculum and operation but are still publicly funded.

Other countries offer unique educational setups. In Finland, for example, schools focus more on student welfare and less on standardized testing, and it's one of the best educational systems in the world.

In Japan, schools emphasize discipline and community, with students even taking turns to clean classrooms.

Adult education is another arm of this institution, aimed at providing lifelong learning opportunities. Whether it's GED programs, community colleges, or online courses, the goal is the same: to empower individuals with the knowledge they need to succeed in life.

3) Religion

Religion is more than just a belief in a higher power; it's a social institution that shapes morals, ethics, and social norms. Through rituals, worship, and a shared sense of community, religion often provides a framework for understanding the world and one's place in it.

Religion has been around for a very long time—probably as long as humans have been capable of complex thought. Early forms of religion were often closely tied to nature and the elements, with gods and goddesses representing forces like the sun, the moon, and the sea.

With the rise of ancient civilizations, religions became more organized, leading to the establishment of religious institutions like temples, churches, and mosques. Over time, different cultures and communities developed their own religious traditions and institutions, often tied to governance and law.

For example, the Catholic Church became a dominant institution in medieval Europe, influencing not just spirituality but also politics and education.

Why does religion matter as a social institution? For one, it's a powerful force for social cohesion, bringing people together under a shared set of beliefs and practices.

Religion also has a significant impact on social values and norms, influencing everything from moral codes to laws to how we interact with others.

In some cases, religious institutions also provide social services, like education and healthcare, and serve as a source of charity and community support.

The diversity of religious institutions is remarkable. Consider Christianity, which has multiple denominations like Catholicism, Protestantism, and Eastern Orthodoxy, each with its own set of beliefs, rituals, and organizational structures.

In Islam, Sunni and Shia Muslims have different interpretations of their faith, leading to different religious practices and institutions.

Hinduism, on the other hand, doesn't have a single centralized institution but consists of various schools of thought and a pantheon of gods and goddesses.

Beyond traditional religions, there are also new religious movements and even "secular religions" like Humanism, which offer ethical and moral frameworks without a belief in a divine power.

In some societies, traditional indigenous beliefs continue to serve as a social institution, shaping community life, rites of passage, and social norms.

4) Government

Government is the institution responsible for making and enforcing laws, administering public services, and representing the interests of the public.

In other words, it's the "control center" of a society, providing structure and maintaining order so that people can live and work together smoothly.

The concept of governance has been around since the earliest human societies, although it's evolved quite a bit over the years.

In early tribal communities, leadership was often tied to physical strength or lineage. With the emergence of agriculture and settled communities, governance structures became more complex, leading to the rise of monarchies, empires, and early forms of democracy in places like ancient Greece.