An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites. .

FEMA Case Study Library

Collections.

- COVID-19 Best Practice Case Studies

- Interagency Recovery Coordination Case Studies

- Mitigation Best Practices

- Preparedness Grants Case Studies

- Assistance to Firefighters Grant Case Studies

- Loss Avoidance Studies

- Risk MAP Best Practices

- Cooperating Technical Partners Program Success Stories

Search All Case Studies

West virginia forms partnerships to increase rural engagement.

West Virginia partners with the Pioneer Network to help spread flood risk information and build community capacity.

Rebuilding Education: Tipton County's Response to a Devastating Tornado

On March 31, 2023, an EF3 tornado wreaked havoc in Tipton County, causing one fatality and 28 injuries in Covington, Tennessee. The Tipton County School Board took on the critical responsibility of swiftly reintegrating students into classrooms for the remainder of the academic year.

Protecting School Children from Tornadoes: State of Kansas School Shelter Initiative

On May 3, 1999, a series of intense storms moved through “Tornado Alley,” producing numerous tornadoes that tore through areas of Oklahoma and Kansas.

Miami County, Ohio: Virtual Inspections

Current building codes require site inspections at several stages throughout the construction process. These can include inspections of concrete slabs, foundation walls, insulation, and roof ice guards, as well as re-inspections of specific or code-required (i.e., welds, masonry, etc.) items.

Hurricane Resistant Building Code Helps Protect Alabama

Coastal Alabama has seen rapid growth over the past decade, but it also happens to be the area most vulnerable to hurricanes and other natural hazards in the state.

Community Wind Shelters: Background and Research

Because of the rising frequency of extreme weather, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) strongly encourages homeowners and communities to build safe rooms to FEMA standards. Community shelters have been consistently needed due to the increased risk posed by strong winds and flying debris during natural hazards.

Mitigation Matters: Rebuilding for a Resilient Future

It’s imperative to acquaint yourself with alternative resources designed to mitigate losses resulting from uncovered damages. These resources are equally essential in fortifying your significant investments against the potential impact of natural hazards, fostering resilience, and minimizing vulnerabilities.

Austin: The State Capital’s Fight Against Wildfire

In 2013, Austin was ranked the city with the third greatest risk of wildfire-related structure losses, specifically for communities outside the urban core. These areas, known as the wildland-urban interface, are in the transition zone between undeveloped rural wildlands and developed areas and account for 61% of households in Austin and 64% of the land within Austin city limits.

Puerto Rico: de la recuperación a la resiliencia

Conozca lo aspectos más destacados de los avances en la recuperación de la isla tras los huracanes María y Fiona, y los terremotos de 2020. Este resumen abarca una selección de proyectos de recuperación que afectan al sector de la salud, la seguridad pública, la red energética y las instalaciones de distribución de agua, entre otros.

Puerto Rico: From Recovery to Resilience

Explore highlights of recovery progress on the island after hurricanes María and Fiona, and the earthquakes in 2020. This overview covers a selection of recovery projects that impact the health sector, public safety, energy grid, water distribution facilities and more.

- 0 Shopping Cart

Kerala flood case study

Kerala flood case study.

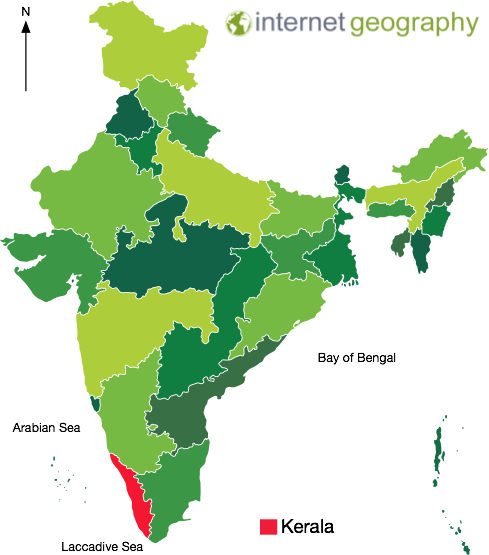

Kerala is a state on the southwestern Malabar Coast of India. The state has the 13th largest population in India. Kerala, which lies in the tropical region, is mainly subject to the humid tropical wet climate experienced by most of Earth’s rainforests.

A map to show the location of Kerala

Eastern Kerala consists of land infringed upon by the Western Ghats (western mountain range); the region includes high mountains, gorges, and deep-cut valleys. The wildest lands are covered with dense forests, while other areas lie under tea and coffee plantations or other forms of cultivation.

The Indian state of Kerala receives some of India’s highest rainfall during the monsoon season. However, in 2018 the state experienced its highest level of monsoon rainfall in decades. According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), there was 2346.3 mm of precipitation, instead of the average 1649.55 mm.

Kerala received over two and a half times more rainfall than August’s average. Between August 1 and 19, the state received 758.6 mm of precipitation, compared to the average of 287.6 mm, or 164% more. This was 42% more than during the entire monsoon season.

The unprecedented rainfall was caused by a spell of low pressure over the region. As a result, there was a perfect confluence of the south-west monsoon wind system and the two low-pressure systems formed over the Bay of Bengal and Odisha. The low-pressure regions pull in the moist south-west monsoon winds, increasing their speed, as they then hit the Western Ghats, travel skywards, and form rain-bearing clouds.

Further downpours on already saturated land led to more surface run-off causing landslides and widespread flooding.

Kerala has 41 rivers flowing into the Arabian Sea, and 80 of its dams were opened after being overwhelmed. As a result, water treatment plants were submerged, and motors were damaged.

In some areas, floodwater was between 3-4.5m deep. Floods in the southern Indian state of Kerala have killed more than 410 people since June 2018 in what local officials said was the worst flooding in 100 years. Many of those who died had been crushed under debris caused by landslides. More than 1 million people were left homeless in the 3,200 emergency relief camps set up in the area.

Parts of Kerala’s commercial capital, Cochin, were underwater, snarling up roads and leaving railways across the state impassable. In addition, the state’s airport, which domestic and overseas tourists use, was closed, causing significant disruption.

Local plantations were inundated by water, endangering the local rubber, tea, coffee and spice industries.

Schools in all 14 districts of Kerala were closed, and some districts have banned tourists because of safety concerns.

Maintaining sanitation and preventing disease in relief camps housing more than 800,000 people was a significant challenge. Authorities also had to restore regular clean drinking water and electricity supplies to the state’s 33 million residents.

Officials have estimated more than 83,000km of roads will need to be repaired and that the total recovery cost will be between £2.2bn and $2.7bn.

Indians from different parts of the country used social media to help people stranded in the flood-hit southern state of Kerala. Hundreds took to social media platforms to coordinate search, rescue and food distribution efforts and reach out to people who needed help. Social media was also used to support fundraising for those affected by the flooding. Several Bollywood stars supported this.

Some Indians have opened up their homes for people from Kerala who were stranded in other cities because of the floods.

Thousands of troops were deployed to rescue those caught up in the flooding. Army, navy and air force personnel were deployed to help those stranded in remote and hilly areas. Dozens of helicopters dropped tonnes of food, medicine and water over areas cut off by damaged roads and bridges. Helicopters were also involved in airlifting people marooned by the flooding to safety.

More than 300 boats were involved in rescue attempts. The state government said each boat would get 3,000 rupees (£34) for each day of their work and that authorities would pay for any damage to the vessels.

As the monsoon rains began to ease, efforts increased to get relief supplies to isolated areas along with clean up operations where water levels were falling.

Millions of dollars in donations have poured into Kerala from the rest of India and abroad in recent days. Other state governments have promised more than $50m, while ministers and company chiefs have publicly vowed to give a month’s salary.

Even supreme court judges have donated $360 each, while the British-based Sikh group Khalsa Aid International has set up its own relief camp in Kochi, Kerala’s main city, to provide meals for 3,000 people a day.

International Response

In the wake of the disaster, the UAE, Qatar and the Maldives came forward with offers of financial aid amounting to nearly £82m. The United Arab Emirates promised $100m (£77m) of this aid. This is because of the close relationship between Kerala and the UAE. There are a large number of migrants from Kerala working in the UAE. The amount was more than the $97m promised by India’s central government. However, as it has done since 2004, India declined to accept aid donations. The main reason for this is to protect its image as a newly industrialised country; it does not need to rely on other countries for financial help.

Google provided a donation platform to allow donors to make donations securely. Google partners with the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP), an intermediary organisation that specialises in distributing your donations to local nonprofits that work in the affected region to ensure funds reach those who need them the most.

Google Kerala Donate

Tales of humanity and hope

Check your understanding.

Premium Resources

Please support internet geography.

If you've found the resources on this page useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.

River flooding and management

Topic home, wainfleet floods case study, share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Community Med

- v.37(3); Jul-Sep 2012

Disaster Management in Flash Floods in Leh (Ladakh): A Case Study

Preeti gupta.

Regimental Medical Officer, Leh, Ladakh, India

Anurag Khanna

1 Commanding Officer, Army Hospital, Leh, India

2 Registrar, Army Hospital, Leh, India

Background:

On August 6, 2010, in the dark of the midnight, there were flash floods due to cloud burst in Leh in Ladakh region of North India. It rained 14 inches in 2 hours, causing loss of human life and destruction. The civil hospital of Leh was badly damaged and rendered dysfunctional. Search and rescue operations were launched by the Indian Army immediately after the disaster. The injured and the dead were shifted to Army Hospital, Leh, and mass casualty management was started by the army doctors while relief work was mounted by the army and civil administration.

The present study was done to document disaster management strategies and approaches and to assesses the impact of flash floods on human lives, health hazards, and future implications of a natural disaster.

Materials and Methods:

The approach used was both quantitative as well as qualitative. It included data collection from the primary sources of the district collectorate, interviews with the district civil administration, health officials, and army officials who organized rescue operations, restoration of communication and transport, mass casualty management, and informal discussions with local residents.

234 persons died and over 800 were reported missing. Almost half of the people who died were local residents (49.6%) and foreigners (10.2%). Age-wise analysis of the deaths shows that the majority of deaths were reported in the age group of 25–50 years, accounting for 44.4% of deaths, followed by the 11–25-year age group with 22.2% deaths. The gender analysis showed that 61.5% were males and 38.5% were females. A further analysis showed that more females died in the age groups <10 years and ≥50 years.

Conclusions:

Disaster preparedness is critical, particularly in natural disasters. The Army's immediate search, rescue, and relief operations and mass casualty management effectively and efficiently mitigated the impact of flash floods, and restored normal life.

Introduction

In the midnight of August 6, 2010, Leh in Ladakh region of North India received a heavy downpour. The cloud burst occurred all of a sudden that caught everyone unawares. Within a short span of about 2 h, it recorded a rainfall of 14 inches. There were flash floods, and the Indus River and its tributaries and waterways were overflowing. As many as 234 people were killed, 800 were injured, and many went missing, perhaps washed away with the gorging rivers and waterways. There was vast destruction all around. Over 1000 houses collapsed. Men, women, and children were buried under the debris. The local communication networks and transport services were severely affected. The main telephone exchange and mobile network system (BSNL), which was the lifeline in the far-flung parts of the region, was completely destroyed. Leh airport was flooded and the runway was covered with debris, making it non-functional. Road transport was badly disrupted as roads were washed away and blocked with debris at many places. The civil medical and health facilities were also severely affected, as the lone district civil hospital was flooded and filled with debris.

Materials and Methods

The present case study is based on the authors’ own experience of managing a natural disaster caused by the flash floods. The paper presents a firsthand description of a disaster and its prompt management. The data was collected from the records of the district civil administration, the civil hospital, and the Army Hospital, Leh. The approach used was both quantitative as well as qualitative. It included data collection from the primary sources of the district collectorate, interviews with the district civil administration and army officials who organized rescue operations, restoration of communication, and transport, mass casualty management, and informal discussions with local residents.

Disaster management strategies

Three core disaster management strategies were adopted to manage the crisis. These strategies included: i) Response, rescue, and relief operations, ii) Mass casualty management, and iii) Rehabilitation.

Response, rescue, and relief operations

The initial response was carried out immediately by the Government of India. The rescue and relief work was led by the Indian Army, along with the State Government of Jammu and Kashmir, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP). The Indian Army activated the disaster management system immediately, which is always kept in full preparedness as per the standard army protocols and procedures.

There were just two hospitals in the area: the government civil hospital (SNM Hospital) and Army Hospital. During the flash floods, the government civil hospital was flooded and rendered dysfunctional. Although the National Disaster Management Act( 1 ) was in place, with the government civil hospital being under strain, the applicability of the act was hampered. The Army Hospital quickly responded through rescue and relief operations and mass casualty management. By dawn, massive search operations were started with the help of civil authorities and local people. The patients admitted in the civil hospital were evacuated to the Army Hospital, Leh in army helicopters.

The runway of Leh airport was cleared up within a few hours after the disaster so that speedy inflow of supplies could be carried out along with the evacuation of the casualties requiring tertiary level healthcare to the Army Command Hospital in Chandigarh. The work to make the roads operational was started soon after the disaster. The army engineers had started rebuilding the collapsed bridges by the second day. Though the main mobile network was dysfunctional, the other mobile network (Airtel) still worked with limited connectivity in the far-flung areas of the mountains. The army communication system was the main and the only channel of communication for managing and coordinating the rescue and relief operations.

Mass casualty management

All casualties were taken to the Army Hospital, Leh. Severely injured people were evacuated from distant locations by helicopters, directly landing on the helipad of the Army Hospital. In order to reinforce the medical staff, nurses were flown in from the Super Specialty Army Hospital (Research and Referral), New Delhi, to handle the flow of casualties by the third day following the disaster. National Disaster Cell kept medical teams ready in Chandigarh in case they were required. The mortuary of the government civil hospital was still functional where all the dead bodies were taken, while the injured were handled by Army Hospital, Leh.

Army Hospital, Leh converted its auditorium into a crisis expansion ward. The injured started coming in around 0200 hrs on August 6, 2010. They were given first aid and were provided with dry clothes. A majority of the patients had multiple injuries. Those who sustained fractures were evacuated to Army Command Hospital, Chandigarh, by the Army's helicopters, after first aid. Healthcare staff from the government civil hospital joined the Army Hospital, Leh to assist them. In the meanwhile, medical equipment and drugs were transferred from the flooded and damaged government civil hospital to one of the nearby buildings where they could receive the casualties. By the third day following the disaster, the operation theatre of the government civil hospital was made functional. Table 1 gives the details of the patients admitted at the Army Hospital.

Admissions in the Army Hospital, Leh

The analysis of the data showed that majority of the people who lost their lives were mainly local residents (49.6%). Among the dead, there were 10.3% foreign nationals as well [ Table 2 ]. The age-wise analysis of the deaths showed that the majority of deaths were reported in the age group 26–50 years, accounting for 44.4% of deaths, followed by 11–25 year group with 22.2% deaths.

Number of deaths according to status of residence

The gender analysis showed that 61.5% were males among the dead, and 38.5% were females. A further analysis showed that more females died in <10 years and ≥50 years age group, being 62.5% and 57.1%, respectively [ Table 3 ].

Age and sex distribution of deaths

Victims who survived the disaster were admitted to the Army Hospital, Leh. Over 90% of them suffered traumatic injuries, with nearly half of them being major traumatic injuries. About 3% suffered from cold injuries and 6.7% as medical emergencies [ Table 4 ].

Distribution according to nature of casualty among the hospitalized victims

Rehabilitation

Shelter and relief.

Due to flash floods, several houses were destroyed. The families were transferred to tents provided by the Indian Army and government and non-government agencies. The need for permanent shelter for these people emerged as a major task. The Prime Minister of India announced Rs. 100,000 as an ex-gratia to the next of kin of each of those killed, and relief to the injured. Another Rs. 100,000 each would be paid to the next of kin of the deceased from the Chief Minister's Relief Fund of the State Government.

Supply of essential items

The Army maintains an inventory of essential medicines and supplies in readiness as a part of routing emergency preparedness. The essential non-food items were airlifted to the affected areas. These included blankets, tents, gum boots, and clothes. Gloves and masks were provided for the persons who were working to clear the debris from the roads and near the affected buildings.

Water, sanitation, and hygiene

Public Health is seriously threatened in disasters, especially due to lack of water supply and sanitation. People having lost their homes and living in temporary shelters (tents) puts a great strain on water and sanitation facilities. The pumping station was washed away, thus disrupting water supply in the Leh Township. A large number of toilets became non-functional as they were filled with silt, as houses were built at the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains. Temporary arrangements of deep trench latrines were made while the army engineers made field flush latrines for use by the troops.

Water was stagnant and there was the risk of contamination by mud or dead bodies buried in the debris, thus making the quality of drinking water questionable. Therefore, water purification units were installed and established. The National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) airlifted a water storage system (Emergency Rescue Unit), which could provide 11,000 L of pure water. Further, super-chlorination was done at all the water points in the army establishments. To deal with fly menace in the entire area, anti-fly measures were taken up actively and intensely.

Food and nutrition

There was an impending high risk of food shortage and crisis of hunger and malnutrition. The majority of food supply came from the plains and low-lying areas in North India through the major transport routes Leh–Srinagar and Leh–Manali national highways. These routes are non-functional for most part of the winter. The local agricultural and vegetable cultivation has always been scanty due to extreme cold weather. The food supplies took a further setback due to the unpredicted heavy downpour. Food storage facilities were also flooded and washed away. Government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and the Indian Army immediately established food supply and distribution system in the affected areas from their food stores and airlifting food supplies from other parts of the country.

There was a high risk of water-borne diseases following the disaster. Many human bodies were washed away and suspected to have contaminated water bodies. There was an increased fly menace. There was an urgent need to prevent disease transmission due to contaminated drinking water sources and flies. There was also a need to rehabilitate people who suffered from crush injuries sustained during the disaster. The public health facilities, especially, the primary health centers and sub-health centers, were not adequately equipped and were poorly connected by roads to the main city of Leh. Due to difficult accessibility, it took many hours to move casualties from the far-flung areas, worsening the crisis and rescue and relief operations. The population would have a higher risk of mental health problems like post-traumatic stress disorder, deprivation, and depression. Therefore, relief and rehabilitation would include increased awareness of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and its alleviation through education on developing coping mechanisms.

Economic impact

Although it would be too early to estimate the impact on economy, the economy of the region would be severely affected due to the disaster. The scanty local vegetable and grain cultivation was destroyed by the heavy rains. Many houses were destroyed where people had invested all their savings. Tourism was the main source of income for the local people in the region. The summer season is the peak tourist season in Ladakh and that is when the natural disaster took place. A large number of people came from within India and other countries for trekking in the region. Because of the disaster, tourism was adversely affected. The disaster would have a long-term economic impact as it would take a long time to rebuild the infrastructure and also to build the confidence of the tourists.

The floods put an immense pressure and an economic burden on the local people and would also influence their health-seeking behavior and health expenditure.

Political context

The disaster became a security threat. The area has a high strategic importance, being at the line of control with China and Pakistan. The Indian Army is present in the region to defend the country's borders. The civil administration is with the Leh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) under the state government of Jammu and Kashmir.

Conclusions

It is impossible to anticipate natural disasters such as flash floods. However, disaster preparedness plans and protocols in the civil administration and public health systems could be very helpful in rescue and relief and in reducing casualties and adverse impact on the human life and socio economic conditions.( 2 ) However, the health systems in India lack such disaster preparedness plans and training.( 3 ) In the present case, presence of the Indian Army that has standard disaster management plans and protocols for planning, training, and regular drills of the army personnel, logistics and supply, transport, and communication made it possible to immediately mount search, rescue, and relief operations and mass casualty management. Not only the disaster management plans were in readiness, but continuous and regular training and drills of the army personnel in rescue and relief operations, and logistics and communication, could effectively facilitate the disaster management operations.

Effective communication was crucial for effective coordination of rescue and relief operations. The Army's communication system served as an alternative communication channel as the public communication and mobile network was destroyed, and that enabled effective coordination of the disaster operations.

Emergency medical services and healthcare within few hours of the disaster was critical to minimize deaths and disabilities. Preparedness of the Army personnel, especially the medical corps, readiness of inventory of essential medicines and medical supplies, logistics and supply chain, and evacuation of patients as a part of disaster management protocols effectively launched the search, rescue, and relief operations and mass casualty reduction. Continuous and regular training and drills of army personnel, health professionals, and the community in emergency rescue and relief operations are important measures. Emergency drill is a usual practice in the army, which maintains the competence levels of the army personnel. Similar training and drill in civil administration and public health systems in emergency protocols for rescue, relief, mass casualty management, and communication would prove very useful in effective disaster management to save lives and restore health of the people.( 2 – 4 )

Lessons learnt and recommendations

Natural disasters not only cause a large-scale displacement of population and loss of life, but also result in loss of property and agricultural crops leading to severe economic burden.( 3 – 6 ) In various studies,( 3 , 4 , 7 , 8 ) several shortcomings have been observed in disaster response, such as, delayed response, absence of early warning systems, lack of resources for mass evacuation, inadequate coordination among government departments, lack of standard operating procedures for rescue and relief, and lack of storage of essential medicines and supplies.

The disaster management operations by the Indian Army in the natural disaster offered several lessons to learn. The key lessons were:

- Response time is a critical attribute in effective disaster management. There was no delay in disaster response by the Indian Army. The rescue and relief operations could be started within 1 h of disaster. This was made possible as the Army had disaster and emergency preparedness plans and protocols in place; stocks of relief supplies and medicines as per standard lists were available; and periodic training and drill of the army personnel and medical corps was undertaken as a routine. The disaster response could be immediately activated.

- There is an important lesson to be learned by the civil administration and the public health system to have disaster preparedness plans in readiness with material and designated rescue officers and workers.

- Prompt activation of disaster management plan with proper command and coordination structure is critical. The Indian Army could effectively manage the disaster as it had standard disaster preparedness plans and training, and activated the system without any time lag. These included standard protocols for search, rescue, and evacuation and relief and rehabilitation. There are standard protocols for mass casualty management, inventory of essential medicines and medical supplies, and training of the army personnel.

- Hospitals have always been an important link in the chain of disaster response and are assuming greater importance as advanced pre-hospital care capabilities lead to improved survival-to-hospital rate.( 9 ) Role of hospitals in disaster preparedness, especially in mass casualty management, is important. Army Hospital, Leh emergency preparedness played a major role in casualty management and saving human lives while the civil district hospital had become dysfunctional due to damage caused by floods. The hospital was fully equipped with essential medicines and supplies, rescue and evacuation equipments, and command and communication systems.

- Standard protocols and disaster preparedness plans need to be prepared for the civil administration and the health systems with focus on Quick Response Teams inclusive of healthcare professionals, rescue personnel, fire-fighting squads, police detachments, ambulances, emergency care drugs, and equipments.( 10 ) These teams should be trained in a manner so that they can be activated and deployed within an hour following the disaster. “TRIAGE” has to be the basic working principle for such teams.

- Effective communication system is of paramount importance in coordination of rescue and relief operations. In the present case study, although the main network with the widest connectivity was extensively damaged and severely disrupted, the army's communication system along with the other private mobile network tided over the crisis. It took over 10 days for reactivation of the main mobile network through satellite communication system. Thus, it is crucial to establish the alternative communication system to handle such emergencies efficiently and effectively.( 2 , 11 )

- Disaster management is a multidisciplinary activity involving a number of departments/agencies spanning across all sectors of development.( 2 ) The National Disaster Management Authority of India, set up under National Disaster Management Act 2005,( 1 ) has developed disaster preparedness and emergency protocols. It would be imperative for the civil administration at the state and district levels in India to develop their disaster management plans using these protocols and guidelines.

- Health system's readiness plays important role in prompt and effective mass casualty management.( 2 ) Being a mountainous region, the Ladakh district has difficult access to healthcare, with only nine Primary Health Centers and 31 Health Sub-Centers.( 12 ) There is a need for strengthening health systems with focus on health services and health facility network and capacity building. More than that, primary healthcare needs to be augmented to provide emergency healthcare so that more and more lives can be saved.( 7 )

- Training is an integral part of capacity building, as trained personnel respond much better to different disasters and appreciate the need for preventive measures. Training of healthcare professionals in disaster management holds the key in successful activation and implementation of any disaster management plan. The Army has always had standard drills in all its establishments at regular intervals, which are periodically revised and updated. The civil administration and public health systems should regularly organize and conduct training of civil authorities and health professionals in order to be ready for action.( 1 – 4 )

- Building confidence of the public to avoid panic situation is critical. Community involvement and awareness generation, particularly that of the vulnerable segments of population and women, needs to be emphasized as necessary for sustainable disaster risk reduction. Increased public awareness is necessary to ensure an organized and calm approach to disaster management. Periodic mock drills and exercise in disaster management protocols in the general population can be very useful.( 1 , 3 , 4 )

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

International Case Studies in the Management of Disasters

Natural - manmade calamities and pandemics, table of contents, introduction, analyzing site security design principles in a built environment and implication for disaster preparedness: the case of istanbul sultanahmet square, turkey.

Today, the presence of unwanted activities threatening the safety of the field, which has negative effects on daily life and social psychology, is increasing day by day. There is no doubt that it is inevitable to avoid these threats, but it is possible to take some measures to reduce the destructive power of these threats. Nowadays, increasing terrorist attacks increase the importance of field safety design in urban areas. There is a loss of life in attacks around the world. The subject of this study is to investigate the design criteria related to the built environment and the measures to be taken in the case of bomb attacks in the built environment. In this study, a checklist will designed to measure the security design process around the building. The checklist titles are taken mainly from the “Safety design and Landscape Architecture” series of the Landscape Architecture Technical Information Series/LATIS publications by the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) and the Risk Management Series of the Federal Emergency Management Agency/FEMA ( FEMA, 2003 , 2007 ; LATIS, 2016 ) and others. The checklist created as a result of literature review will be tested in Istanbul Sultanahmet Square. As a result of the study, it was determined that improvements should be made in the areas of vehicular and pedestrian access, parking lots, lighting and trash receptacle designs around Sultanahmet Square.

Local Knowledge in Russian Flood-prone Communities: A Case Study on Living with the Treacherous Waters

Owing to the climate change, the number of flood hazards and communities at risk is expected to rise. The increasing flood risk exposure is paralleled with an understanding that hard flood defense measures should be complemented with soft sociotechnical approaches to flood management. Among other things, this involves development of a dialogue between professionals and flood-prone communities to ensure that the decisions made correspond to the peculiarities of local socioenvironmental contexts. However, in practice, establishment of such a dialogue proves to be challenging. Flood-prone communities are often treated as mere recipients of professional knowledge and their local knowledge remains underrated. Building on an illustrative case study of one rural settlement in North-West Russia, we examine how at-risk communities develop their local knowledge and put it to use as they struggle with adverse impacts of flooding, when the existing flood protection means are insufficient. Our findings showcase that local knowledge of Russian flood-prone communities is axiomatic and tacit, acquired performatively through daily interaction of local residents with their natural and sociotechnical environments. Even if unacknowledged by both the local residents and flood management professionals as a valuable asset for long-term flood management, it is local knowledge that informs local communities' practices and enables their coexistence with the treacherous waters.

Financial Implications of Natural Disasters: A Case Study of Floods in Pakistan

Natural disasters occur all around the world, in the last two decades these natural disasters have brought sever damages to the world economy. Mostly developing countries bear severe consequences due to these natural disasters. In July 2010, Pakistan faced a massive flood, which affected almost all the countries. The disaster affected all sectors like daily life, transportation, infrastructure, etc., of the country. GOP did not have enough resources to cope with this giant disaster and called for international help. Local and international NGOs participated with GOP in the early phases of recovery. Millions of dollars were given away as the initial impact of this disaster, and GOP and other relief agents have spent other million to provide initial recovery and relief. GOP will need billions of dollars further to continue recovery from the disaster of 2010.

Microcase Studies on Managing Tourism Destinations in the Aftermath of Disasters

Comparing the experiences of african states in managing ebola outbreaks from 2014 into 2020 *.

Eradicating Ebola from West Africa was struggled with from 2014 through 2016. While at first inefficient and ineffective, undeniable progress was made in responding to the outbreak once countries and organizations steeled themselves for the task at hand. A separate outbreak occurred concurrently in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) during this period. This episode marked the seventh time that DRC had dealt with the virus over a roughly 45-year span. In 2017, there was an eighth occurrence. Moreover, in 2018, DRC faced its ninth and tenth outbreaks. Comparing the experiences of countries in West Africa facing the disease for the first time, with a state that has a long history addressing its impact, is offered here as a means of better understanding successful disease management where public health epidemics are concerned. Results indicate that early investment in cultivating disease-specific practices, combined with establishing cooperative networks of actors across levels of political response, enables improved mitigation and response during outbreaks.

Kerala Nipah Virus Outbreak 2018: The Need for Global Surveillance of Zoonotic Diseases

Managing visiting scholars' program during the covid-19 pandemic.

International mobility outgoing and incoming from almost every university around the world is not just oriented to highly educative standards among them, but to enhance the development of international competences for students, as well as for academics. While students' mobility are mostly an individual effort that implies individual consequences, academics' mobility involve several resources from universities and trigger collective processes such as research collaboration, visiting lecturers, exchange experiences and best practices meetings, plenary sessions, classes, among others. This case study aims to provide insights about how planned activities related for/with visiting international scholars suffer major disruption and collateral damages when an unplanned and unexpected global crisis occurs, which forces them to react immediately under different real-time decisions and nonexistent protocols. The chapter focuses on Latin America, using the case of the Global Business Week organized by Universidad de Monterrey (UDEM) in Mexico, and involving visiting scholars from Peru and Colombia.

Managing E-commerce During a Pandemic: Lessons from GrubHub During COVID-19

The GrubHub Inc, started as a small food ordering service in Chicago in 2004, and has developed into an e-commerce food delivery giant worth over $3 billion. Since its merger with Seamless in 2013, GrubHub has experienced 53% year-over-year growth in revenue. While online food ordering commerce has been expanding over the years, due to the COVID-19, the industry is experiencing an economic shock. Consumers have begun to isolate themselves from outside as much as possible and local shops have been started to close one by one. As a result, demand has been shrinking to services such as GrubHub, even though otherwise would be expected. In order to survive, the company has to employ new measures and devise new ways of conducting business to protect its competitiveness through catering recently changed needs of community due to the pandemic. This case study explains and demonstrates the set of steps that are taken by GrubHub and their effects on its customers, key business partners, shareholder, and stakeholders.

The Role of Communications in Managing a Disaster: The Case of COVID-19 in Vietnam

Despite a ravaging pandemic worldwide, Vietnam managed to contain the local outbreak, partly owing to its carefully implemented risk communications campaign. This chapter investigated the effectiveness of official Vietnam government communications, the sentiment of foreign media reporting on Vietnam, and any challenges. Content analysis was applied to samples from government communications (43 samples); international articles (46); and social media conversations (33). Official government communications were quite accurate, timely, and effective in displaying transparency, employing war symbolism, and shared responsibility, but should more clearly separate between state and expert, offer differing views, and highlight the benefits of compliance. International articles praised the government's viral PSA TikTok video, its transparency, and the netizens' nationalist narratives. While some evidence was found for infodemic, blaming, and heroization, the sample was too small to be conclusive. Future studies should expand the timeframe to a longer duration, quantitatively appraise a wider sampling of social media conversations, and possibly conduct primary interviews with experts, policy makers, and the public.

Passage from the Tourist Gaze to the Wicked Gaze: A Case Study on COVID-19 with Special Reference to Argentina

The Day the World Stopped is a science fiction film that narrates the days of mankind amid an alien invasion headed to avoid the climate change. We made the decision to use a similar title to narrate the facts that precede the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, and its immediate effects on the industry of tourism. Over years, scholars cited John Urry and his insight over the tourist gaze as well as the importance of tourism as a social institution. Of course, Urry never imagined that one day this global world would end. This chapter centers on the needs of discussing the concept of the wicked gaze, which exhibits the end of hospitality, a tendency emerged after 9/11. This chapter punctuates on the decline of hospitality—at least as it was imagined by ancient philosophers—in a way that the tourist gaze sets the pace to a wicked gaze. Whether hospitality and free transit were the foundational values of West, COVID-19, and the resulted state of emergency reveals a new unknown process of feudalization which comes to stay. The chapter is framed based on long-dormant philosophical debates, but given the complexity of this issue, the efforts deserve our attention.

COVID-19 Outbreak in Finland: Case Study on the Management of Pandemics

COVID-19 has created an unprecedented situation for Finland like never before. These are desperate times for Finland. And desperate times need desperate measures. The Government of Finland is pulling out all the stops and doing everything possible in its continued fight against COVID-19 virus. The crisis primarily erupted due to the initial delay in action and lack of preparedness required to tackle this kind of crisis. Communication channels were put to best use by the Finnish Government in an effort to reach out to all the people in Finland. The people living in Finland should strictly follow the guidelines and support the measures by the Government in full tandem to ensure that the COVID-19 virus is defeated and stops further transmission by breaking the chain. This paper portrays different possible trajectories and outcomes associated with the impacts of the pandemic in Finland.

The COVID-19 Crisis Management in the Republic of Korea

Until recently, the business environment was characterized by a world in which nations were more connected than ever before. Unfortunately, the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has virtually ended the borderless and globalized world we were accustomed to. The World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic at a news conference in Geneva on March 11, 2020. The multifaceted nature of this invisible virus is impacting the world at many levels, and this unprecedented pandemic may best be characterized as an economic and health war against humanity. More international cooperation is crucial for effectively dealing with the present pandemic (and future pandemics) because all nations are vulnerable, and it is highly unlikely that any pandemic would affect only one country. Therefore, this case study takes a sociological approach, examining various social institutions and cultural facets (i.e., government, press freedom, information technology [IT] infrastructure, healthcare systems, and institutional collectivism) to understand how South Korea is handling the crisis while drawing important implications for other countries. All aspects of how Korea is handling COVID-19 may not be applicable to other countries, such as those with fewer IT infrastructures and less institutional collectivism. However, its methods still offer profound insights into how countries espousing democratic values rooted in openness and transparency to both domestic and worldwide communities can help overcome the current challenge. As such, the authors believe that Korea's innovative approach and experience can inform other nations dealing with COVD-19, while also leading to greater international collaboration for better preparedness when such pandemics occur in the future. This case study also considers implications for both public policy and organization, and the authors pose critical questions and offer practical solutions for dealing with the current pandemic.

Empowering Patients through Social Media and Implications for Crisis Management: The Case of the Gulf Cooperation Council

Empowered patients are allies to the healthcare system, especially in emergency situations. Social media use has emerged to be a major means by which patients interact with the healthcare system, and in times such as the current COVID-19 situation social media has to play an even greater crisis management role by empowering patients. Social media channels serve numerous beneficial purposes, despite them also being blamed for the spread of misinformation during this crisis. In this Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) focused case study, we will discuss the increasingly greater role being played by the social media in healthcare in the region and how that empowers not just the patients but the system as a whole. In the GCC region, the healthcare sector is found to reflect a steady growth, leading to an increased drive for empowering patients by lowering the barriers to effective communication and consultation through online media. As of today, social media has become an element of the telehealth infrastructure being deployed in the region. During COVID-19, patients are seen to leverage it pointedly for online health consultations thereby lowering the stress on the healthcare system and adding to efficiencies.

Technology in Medicine: COVID-19 and the “Coming of Age” of Telehealth

Telehealth has been playing a progressively significant role in the management of the COVID-19 crisis. The enforcement of social distancing measures has had the consequence of reduced technology distance in almost every walk of life. In this chapter, based primarily on the still-unfolding experiences of deploying it during the current situation, we argue that telehealth has finally come of age and that it is time to move it from the peripheries to the center of the twenty-first-century healthcare. To provide a live context to the discussion, several instances of how telehealth strengthened our healthcare systems during the COVID-19 crisis are presented.

- Dr. Babu George

- Dr. Qamaruddin Mahar

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Articles, Papers, Symposia

- Case Studies

- Why Was Boston Strong Initiative

- Executive Education

- Student Involvement

- Confronting Disasters

- 2019 Events

- 2018 Events

- 2017 Events

- 2016 Events

- 2015 Events

- 2014 Events

- 2013 Events

- 2012 Events

- 2011 Events

- 2010 Events

- 2009 Events

- Why Was Boston Strong?

- Our Program

In This Section

The program has developed an extensive catalogue of case studies addressing crisis events. These cases serve as an important tool for classroom study, prompting readers to think about the challenges different types of crises pose for public safety officials, political leaders, and the affected communities at large.

The following cases, here organized into three broad categories, are available through the Harvard Kennedy School Case Program ; click on a case title to read a detailed abstract and purchase the document. A selection of these cases are also available in the textbooks Managing Crises: Responses to Large-Scale Emergencies (Howitt and Leonard, with Giles, CQ Press) and Public Health Preparedness: Case Studies in Policy and Management (Howitt, Leonard, and Giles, APHA Press), both of which contain fifteen cases as well as corresponding conceptual material to support classroom instruction.

Natural Disasters, Infrastructure Failures, and Systems Collapse

At the Center of the Storm: San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz and the Response to Hurricane Maria (Case and Epilogue) This case profiles how Carmen Yulín Cruz, Mayor of San Juan, Puerto Rico, led her City’s response to Hurricane Maria, which devastated the island and neighboring parts of the Caribbean in the fall of 2017. By highlighting Cruz’s decisions and actions prior to, during, and following the storm’s landfall, the case provides readers with insight into the challenges of preparing for and responding to severe crises like Maria. It illustrates how several key factors—including San Juan’s pre-storm preparedness efforts, the City’s relationships with other jurisdictions and entities, and the ability to adapt and improvise in the face of novel and extreme conditions—shaped the response to one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

A Cascade of Emergencies: Responding to Superstorm Sandy in New York City (A and B) On October 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy made landfall near Atlantic City, New Jersey. Sandy’s massive size, coupled with an unusual combination of meteorological conditions, fueled an especially powerful and destructive storm surge, which caused unprecedented damage in and around New York City, the country’s most populous metropolitan area, as well as on Long Island and along the Jersey Shore. This two-part case study focuses on how New York City prepared for the storm’s arrival and then responded to the cascading series of emergencies – from fires, to flooding, to power failures – that played out as it bore down on the region. Profiling actions taken at the local level by emergency response agencies like the New York City Fire Department (FDNY), the case also explores how the city coordinated with state and federal partners – including both the state National Guard and federal military components – and illustrates both the advantages and complications of using military assets for domestic emergency response operations.

Part B of the case highlights the experience of Staten Island, which experienced the worst of Sandy’s wrath. In the storm’s wake, frustration over the speed of the response triggered withering public criticism from borough officials, leading to concerns that a political crisis was about to overwhelm the still unfolding relief effort.

Surviving the Surge: New York City Hospitals Respond to Superstorm Sandy Exploring the experiences of three Manhattan-based hospitals during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, the case focuses on decisions made by each institution about whether to shelter-in-place or evacuate hundreds of medically fragile patients -- the former strategy running the risk of exposing individuals to dangerous and life-threatening conditions, the latter being an especially complex and difficult process, not without its own dangers. "Surviving the Surge" illustrates the very difficult trade-offs hospital administrators and local and state public health authorities grappled with as Sandy bore down on New York and vividly depicts the ramifications of these decisions, with the storm ultimately inflicting serious damage on Manhattan and across much of the surrounding region. (Included in Howitt, Leonard, and Giles, Public Health Preparedness)

Ready in Advance: The City of Tuscaloosa’s Response to the 4/27/11 Tornado On April 27, 2011, a massive and powerful tornado leveled 1/8 of the area of Tuscaloosa, AL. Doctrine called for the County Emergency Management Agency (EMA) to take the lead in organizing the response to the disaster – but one of the first buildings destroyed during the event housed the County EMA offices, leaving the agency completely incapacitated. Fortunately, the city had taken several steps in the preceding years to prepare for responding to a major disaster. This included having sent a delegation of 70 city officials and community leaders, led by Tuscaloosa Mayor Walter Maddox, to a week-long training organized by FEMA. “Ready in Advance” reveals how that training, along with other preparedness activities undertaken by the city, would pay major dividends in the aftermath of the tornado, as the mayor and his staff set forth to respond to one of the worst disasters in Tuscaloosa’s history.

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: The Politics of Crisis Response (A and B) Following the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in late April 2010, the Obama administration organized a massive response operation to contain the oil spreading across the Gulf of Mexico. Attracting intense public attention, the response adhered to the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, a federal law that the crisis would soon reveal was not well understood – or even accepted – by all relevant parties.

This two-part case series profiles how senior officials from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security sought to coordinate the actions of a myriad of actors, ranging from numerous federal partners; the political leadership of the affected Gulf States and sub-state jurisdictions; and the private sector. Case A overviews the disaster and early response; discusses the formation of a National Incident Command (NIC); and explores the NIC’s efforts to coordinate the actions of various federal entities. Case B focuses on the challenges the NIC encountered as it sought to engage with state and local actors – an effort that would grow increasingly complicated as the crisis deepened throughout the spring and summer of 2010.

The 2010 Chilean Mining Rescue (A and B) On August 5, 2010, 700,000 tons of rock caved in Chile's San José mine. The collapse buried 33 miners at a depth almost twice the height of the Empire State Building-over 600 meters (2000 feet) below ground. Never had a recovery been attempted at such depths, let alone in the face of challenges like those posed by the San José mine: unstable terrain, rock so hard it defied ordinary drill bits, severely limited time, and the potentially immobilizing fear that plagued the buried miners. The case describes the ensuing efforts that drew the resources of countless people and multiple organizations in Chile and around the world.

The National Guard’s Response to the 2010 Pakistan Floods Throughout the summer of 2010, Pakistan experienced severe flooding that overtook a large portion of the country, displacing millions of people, causing extensive physical damage, and resulting in significant economic losses. This case focuses on the role of the National Guard (and of the U.S. military, more broadly) in the international relief effort that unfolded alongside that of Pakistan’s government and military. In particular it highlights how various Guard and U.S. military assets that had been deployed to Afghanistan as part of the war there were reassigned to support the U.S.’s flood relief efforts in Pakistan, revealing the successes and challenges of transitioning from a war-footing to disaster response. In exploring how Guard leaders partnered with counterparts from other components of the U.S. government, Pakistani officials, and members of the international humanitarian community, the case also examines how they navigated a set of difficult civilian-military dynamics during a particularly tense period in US-Pakistan relations.

Inundation: The Slow-Moving Crisis of Pakistan’s 2010 Floods (A, B, and Epilogue) In summer 2010, unusually intense monsoon rains in Pakistan triggered slow-moving floods that inundated a fifth of the country and displaced millions of people. This case describes how Pakistan’s Government responded to this disaster and highlights the performance of the country’s nascent emergency management agency, the National Disaster Management Authority, as well as the integration of international assistance.

"Operation Rollback Water": The National Guard’s Response to the 2009 North Dakota Floods ( A , B , and Epilogue ) In spring 2009, North Dakota experienced some of the worst flooding in the state’s history. The state's National Guard responded by mobilizing thousands of its troops and working in concert with personnel and equipment from six other states. This case profiles the National Guard’s preparations for and response to the floods and focuses on coordination within the National Guard, between the National Guard and civilian government agencies, and between the National Guard and elected officials.

Typhoon Morakot Strikes Taiwan, 2009 (A, B, and C) In less than four days, Typhoon Morakot dumped close to 118 inches of rain on Taiwan, flooding cities, towns, and villages; washing away roads and bridges; drowning farmland and animals; and triggering mudslides that buried entire villages. With the typhoon challenging its emergency response capacity, Taiwan’s government launched a major rescue and relief operation. But what began as a physical disaster soon became a political disaster for the President and Prime Minister, as bitter criticism came from citizens, the opposition party, and the President’s own supporters.

Getting Help to Victims of 2008 Cyclone Nargis: AmeriCares Engages with Myanmar's Military Government (Case and Epilogue) In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar (Burma) left 138,373 dead or missing and 2.4 million survivors’ livelihoods in doubt, making it the country’s worst natural disaster and one of the deadliest cyclones ever. Friendly Asian countries as well as western governments which previously had used economic sanctions to isolate Myanmar’s military government now sought to provide aid to Myanmar’s people. But they met distrust and faced adversarial relationships from a suspicious government, reluctant to open its borders to outsiders.

China's Blizzards of 2008 From January 10-February 6, a series of heavy snow storms intertwined with ice storms and subzero temperatures created China’s worst winter weather in 50 years. The storms closed airports and paralyzed trains and roads, damaged power grids and water supplies, caused massive black-outs, and left several cities in hard-hit areas isolated and threatened. The disruption of the power supply and transport also severely affected the production and flow of consumer goods and industrial materials, triggering a cascade of crisis nationwide. Coal reserves at power plants were nearly exhausted, production was significantly cut back at big factories, the chronic winter power shortage was exacerbated, and food prices spiked sharply in many areas because of shortages.

Thin on the Ground: Deploying Scarce Resources in the October 2007 Southern California Wildfires When wildfires swept across Southern California in October 2007, firefighting resources were stretched dangerously thin. Readers are prompted to put themselves in the shoes of public safety authorities and consider how organizations can best address resource scarcities in advance of and during emergency situations.

"Broadmoor Lives:" A New Orleans Neighborhood’s Battle to Recover from Hurricane Katrina (A, B, and Sequel) Stunned by a city planning committee’s proposal to give New Orleans neighborhoods hard-hit by Hurricane Katrina just four months to prove they were worth rebuilding, the Broadmoor community organized and implemented an all-volunteer redevelopment planning effort to bring their neighborhood back to life.

Gridlock in Texas (A and B) As Hurricane Rita bore down on the Houston metro area in mid-September 2005, just a few weeks after Hurricane Katrina had devastated the Gulf Coast, millions of people flocked to the roadways. Part A details the massive gridlock that ensued, illustrating the challenges of implementing safe evacuations and of communicating effectively amidst great fear. Part B explores post-storm efforts to improve evacuation policies and procedures -- and how the resulting plans measured up in 2008, when the area was once again under threat, this time from Hurricane Ike.

Wal-Mart’s Response to Hurricane Katrina: Striving for a Public-Private Partnership (Case and Sequel) This case explores Wal-Mart's efforts to provide relief in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, raising important questions about government’s ability to take full advantage of private sector capabilities during large-scale emergencies. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

Moving People out of Danger: Special Needs Evacuations from Gulf Coast Hurricanes (A and B ) In the face of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, officials in Louisiana and Texas grappled with the challenging task of evacuating people with medical and other special needs to safety. The shortcomings of those efforts sparked major initiatives to improve evacuation procedures for individuals requiring transportation assistance – plans that got a demanding test when Hurricanes Gustav and Ike threatened the Gulf Coast in the fall of 2008. (Included in Howitt, Leonard, and Giles, Public Health Preparedness)

Hurricane Katrina: (A) Preparing for the Big One , and (B) Responding to an "Ultra-Catastrophe" in New Orleans Exploring the failed response to Hurricane Katrina and its implications for the greater New Orleans area, the case begins with a review of pre-event planning and preparedness efforts. Part B details the largely ineffective governmental response to the rapidly escalating crisis. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises; Also available in abridged form.)

Rebuilding Aceh: Indonesia's BRR Spearheads Post-Tsunami Recovery (Case and Epilogue) The December 26, 2004, Indian Ocean tsunami caused tremendous damage and suffering on several continents, with Indonesia's Aceh Province, located on the far northern tip of Sumatra Island, experiencing the very worst. In the tsunami's wake, the Indonesian government faced a daunting task of implementing a large-scale recovery effort, and to coordinate the many reconstruction projects that soon began to emerge across Aceh, Indonesia's president established a national-level, ad hoc agency, which came to be known by its acronym BRR. This case examines the challenges encountered by BRR's leadership as it sought to implement an effective recovery process.

When Imperatives Collide: The 2003 San Diego Firestorm (Case and Epilogue) In October 2003, multiple wildfires burned across southern California. Focusing on the response to the fires, this case explores what can happen when an operational norm — to fight fires effectively but safely — collides with the political imperative to override established procedures to protect the public. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

"Almost a Worst Case Scenario:" The Baltimore Tunnel Fires of 2001 (A, B, and C) When a train carrying hazardous materials derailed under downtown Baltimore, a stubborn underground fire severely challenged emergency responders. Readers are prompted to give particular attention to the significant challenges of managing a multi-organizational response. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

Safe But Annoyed: The Hurricane Floyd Evacuation in Florida When far more citizens than necessary evacuated in advance of Hurricane Floyd, Florida’s roadways were quickly overloaded and emergency management operations overwhelmed. In detailing these (and other) problems, the case highlights the challenges of managing evacuations in advance of potentially catastrophic events. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

The US Forest Service and Transitional Fires This case outlines the operational challenges of decision making in a high stress, high stakes situation – in this instance during rapidly evolving wildland fires, also known as "transitional fires." (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

The Tzu Chi Foundation's China Relief Mission Tzu Chi is one of the largest charities in Taiwan, and one of the swiftest and most effective relief organizations internationally. Rooted in the value of compassion, the organization has many unusual operating features -- including having no long term plan. This case explores the basic operating approach of the organization and invites students to explain the overall effectiveness and success of the organization and its surprising success (as a faith-based, Taiwanese, direct-relief organization -- all of which are more or less anathema to the Chinese government) in securing an operating license in China.

Security Threats

Ce Soir-Là, Ils n'Arrivent Plus Un par Un, Mais par Vagues: Coping with the Surge of Trauma Patients at L'Hôpital Universitaire La Pitié Salpêtrière-Friday, November 13, 2015 On November 13, 2015, Dr. Marie Borel, Dr. Emmanuelle Dolla, Dr. Frédéric Le Saché, and Prof. Mathieu Raux were the doctors in charge of the trauma center at L'Hôpital de la Pitié Salpêtrière in Paris, where dozens of wounded and dying patients, most with severe gunshot wounds from military grade firearms, arrived in waves after a series of terrorist attacks across the city. The doctors had trained for a mass-casualty event but had never envisioned the magnitude of what they now saw. This case describes how they rapidly expanded the critical care capacity available so as to be able to handle the unexpectedly large number of patients arriving at their doors.

Into Local Streets: Maryland National Guard and the Baltimore Riots (Case and Epilogue) On April 19, 2015, Freddie Gray, a young African American male, died while in the custody of the Baltimore Police. In response to his death, protestors mobilized daily in Baltimore to vocalize their frustrations, including what they saw as law enforcement’s long-standing mistreatment of the African American community. Then, on April 27, following Gray’s funeral, riots and acts of vandalism broke out across the city. Overwhelmed by the unrest, the Baltimore police requested assistance from other police forces. Later that evening, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan declared a state of emergency and activated the Maryland National Guard. At the local level, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake issued a nightly curfew beginning Tuesday evening.

“Into Local Streets” focuses on the role of the National Guard in the response to the protests and violence following Gray’s death, vividly depicting the actions and decision-making processes of the Guard’s senior-most leaders. In particular, it highlights the experience of the state’s Adjutant General, Linda Singh, who soon found herself navigating a complicated web of officials and agencies from both state and local government – and their different perspectives on how to bring an end to the crisis.

Defending the Homeland: The Massachusetts National Guard Responds to the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings On April 15, 2013, Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev placed and detonated two homemade bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, killing three bystanders and injuring more than two hundred others. This case profiles the role the Massachusetts National Guard played in the complex, multi-agency response that unfolded in the minutes, hours, and days following the bombings, exploring how its soldiers and airmen helped support efforts on multiple fronts – from performing life-saving actions in the immediate aftermath of the attack to providing security on the region’s mass transit system and participating in the search for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev several days later. It also depicts how the Guard’s senior officers helped manage the overall response in partnership with their local, state, and federal counterparts. The case reveals both the emergent and centralized elements of the Guard’s efforts, explores the debate over whether or not Guard members should have been armed in the aftermath of the bombings, and highlights an array of unique assets and capabilities that the Guard was able to provide in support of the response.

Recovery in Aurora: The Public Schools' Response to the July 2012 Movie Theater Shooting (A and B) In July 2012, a gunman entered a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado and opened fire, killing 12 people, injuring 58 others, and traumatizing a community. This two-part case briefly describes the shooting and emergency response but focuses primarily on the recovery process in the year that followed. In particular, it highlights the work of the Aurora Public Schools, which under the leadership of Superintendent John L. Barry, drew on years of emergency management training to play a substantial role in the response and then unveiled an expansive recovery plan. This included hiring a full-time disaster recovery coordinator, partnering with an array of community organizations, and holding mental health workshops and other events to support APS community members. The case also details the range of reactions that staff and community members had to APS' efforts, broader community-wide recovery efforts, and stakeholders' perspectives on the effectiveness of the recovery.

"Miracle on the Hudson" (A, B, and C) Case A describes how in January 2009, shortly after takeoff from LaGuardia Airport, US Airways Flight 1549 lost all power when Canada geese sucked into its engines destroyed them. In less than four harrowing minutes, Flight 1549’s captain and first officer had to decide whether they could make an emergency landing at a nearby airport or find another alternative to get the plane down safely. Cases B and C describe how emergency responders from many agencies and private organizations on both sides of the Hudson River – converging on the scene without a prior action plan for this type of emergency – effectively rescued passengers and crew from the downed plane.

Security Planning for the 2004 Democratic National Convention in Boston (A, B, and Epilogue) When the city of Boston applied to host the 2004 Democratic Party presidential nominating convention, it hoped to gain considerable prestige and significant economic benefits. But convention organizers and local officials were forced to grapple with a set of unanticipated planning challenges that arose in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

Command Performance: County Firefighters Take Charge of the 9/11 Pentagon Emergency This case describes how the Arlington County Fire Department – utilizing the Incident Management System – took charge of the large influx of emergency workers who arrived to put out a massive fire and rescue people in the Pentagon following the September 11, 2001, suicide jetliner attack. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

Rudy Giuliani: The Man and His Moment Although not long before the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani had been under fire for aspects of his mayoralty, the post 9/11 Giuliani won national and international acclaim as a leader. This case recounts the details of Giuliani’s response such that students of effective public leadership can analyze both Giuliani’s decisions and style as examples.

Threat of Terrorism: Weighing Public Safety in Seattle (Case and Epilogue) When a terrorist was arrested in late December 1999 at the Canadian-Washington State border in a car laden with explosives, public safety officials worried that the city of Seattle had been a possible target. This case explores the debate that ensued concerning the seriousness of the threat and whether the city should proceed with its planned Millennium celebration. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

Protecting the WTO Ministerial Conference of 1999 (Case and Epilogue) Two very different sets of actors made extensive preparations in advance of the World Trade Organization's Ministerial Conference of 1999 — protesters opposing international trade practices and public safety officials responsible for event security. This case examines the efforts of both, highlighting why security arrangements ultimately fell short. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

The Shootings at Columbine High School: Responding to a New Kind of Terrorism (Case and Epilogue) Within minutes of the shootings at Columbine, numerous emergency response agencies – including law enforcement, fire fighters, emergency medical technicians, and others – dispatched personnel to the school site. Under intense media scrutiny and trying to coordinate their actions, they sought to determine whether the shooters were still active and rescue the injured.

To What End? Re-Thinking Terrorist Attack Exercises in San Jose (Case, Sequel 1, Sequel 2) In the late 1990s, a task force in San Jose, CA mounted several full-scale terrorist attack exercises, but—despite the best of intentions—found all of them frustrating, demoralizing, and divisive. In response, San Jose drew on several existing prototypes to create a new “facilitated exercise” model that emphasized teaching over testing, and was much better received by first responders.

Security Preparations for the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games (A, B, and C) This case describes efforts by state and federal government entities to plan in advance for security protection for the Atlanta Olympics. It also recounts the Centennial Park bombing and emergency response. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

The Flawed Emergency Response to the 1992 Los Angeles Riots (A, B, and C) Following the announcement of the not guilty verdicts for the law enforcement officers accused of beating Rodney King, the City of Los Angeles was quickly overrun by severe rioting. This case reviews how local, county, state, and federal agencies responded and coordinated their activities in an effort to restore order. (Included in Howitt & Leonard, Managing Crises)

Public Health Emergencies

Mission in Flux: Michigan National Guard in Liberia ( Case and Epilogue ) In summer and fall of 2014, thousands of individuals in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea contracted the Ebola virus. This outbreak of the deadly disease, which until then had been highly uncommon in West Africa, prompted a major (albeit delayed) public health response on the part of the international community, including an unprecedented commitment made by the United States, which sent almost 3,000 active military soldiers to Liberia. “Mission in Flux” focuses on the US military’s role in the Ebola response, emphasizing the Michigan National Guard’s eventual involvement. In particular, it provides readers with a first-hand account of the challenges the Michigan Guard faced as it prepared for and then deployed to Liberia, just as the crisis had begun to abate and federal officials in Washington began considering how to redefine the mission and footprint of Ebola-relief in West Africa.