Art Movement: Baroque – The Style of an Era

“The Baroque… endlessly produces folds. It does not invent things: there are all kinds of folds coming from the East, Greek, Roman, Romanesque, Gothic, Classical folds…..Yet the Baroque trait twists and turns its folds, pushing them to infinity, fold over fold, one upon the other.” The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque , Gilles Deleuze

The term Baroque, derived from the Portuguese ‘barocco’ meaning ‘irregular pearl or stone’, refers to a cultural and art movement that characterized Europe from the early seventeenth to mid-eighteenth century. Baroque emphasizes dramatic, exaggerated motion and clear, easily interpreted, detail. Due to its exuberant irregularities, Baroque art has often been defined as being bizarre, or uneven.

Baroque: origins & key ideas

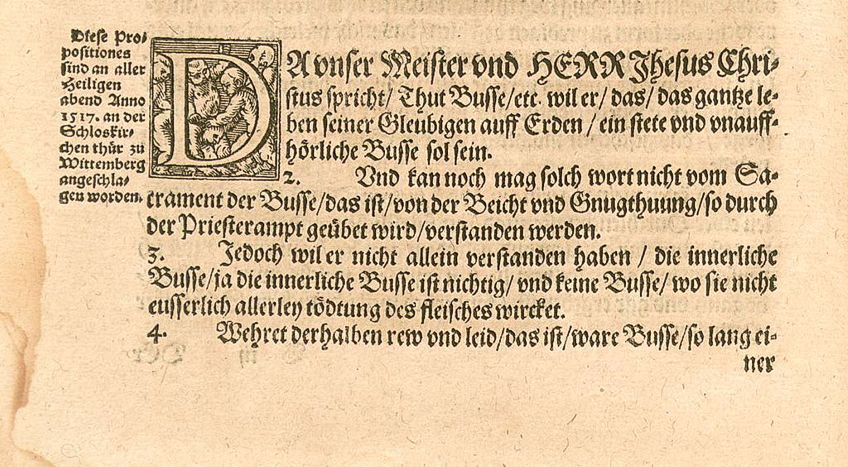

The Baroque era was very much defined by the influences of the major art movement which came before it, the Renaissance. So much so that many art history scholars have argued that Baroque art was simply the end of the Renaissance and never existed as a cultural or historical phenomenon. Others have disagreed and argued that the events of the Protestant Reformation and the devastation of the Thirty Year’s War changed the way Europeans and European artists saw and engaged with the world shifted the directions of the arts and cultures, therefore implicating a clear distinction from the Renaissance.

It’s the sheer scale and importance of events as well as the contrasting painting styles over the course of the era that make it hard to pin an idea to Baroque. Europe was encountering one of its greatest shifts in society, especially with the challenge to the Roman Catholic Church; yet, through the early Baroque artists Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini, the Baroque art movement began with the commissions of masterpieces from the Vatican and the social and religious circles around it. The Renaissance architectural mode went from linear to painterly, and Renaissance ideas of perfection, completion, and conceivability were challenged with ideas of becoming, paint likeness, endlessness, and limitlessness.

Key Period: 1590-1740 Key Regions: Europe: France, Italy, Netherlands, Germany Key Words: Grandeur, color, reformation, drama, non-linear Key Artists : Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini, Annibale Carracci, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Sebastian Bach, Pierre Puget, Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco), Johannes Vermeer van Delft, Antonio Vivaldi.

“I would define the baroque as that style that deliberately exhausts its own possibilities”. Jorge Luis Borges

Style & characteristics

The Baroque art movement had no real directive or specific school driving it. Instead, it consisted of many great schools and artists across Europe throughout the 150 or so years of the Baroque Era encompassing a wide range of styles. Additionally, the quantity of genius-level artistry coming from different countries, schools, styles, and fields injects an added level of subjectivity to what Baroque may mean for an observer of the art movement. The best way to approach the mapping of Baroque art characteristics is therefore often the interaction with specific schools, artists, and artistic mediums. Generally, the main features of Baroque painting manifestations are drama, deep colors, dramatic light, sharp shadows and dark backgrounds. While Renaissance art aimed to highlight calmness and rationality, Baroque artists emphasized stark contrasts, passion, and tension, often choosing to depict the moment preceding an event instead of its occurrence.

Baroque painting

The most prominent Baroque painters originated from the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain. Generally, they were concerned with the human subjects or subjects and depicted similar scenes. The renaissance spheres of power still dominated the art directions of their cultures, and, accordingly, most of the commissions were portraits of royals, religious scenes, depictions of royal life and society. However, with the Baroque era came a rise in history and landscape paintings, as well as, portraits, genre scenes and still lives.

Such paintings flourished specifically in the Netherlands. Great Dutch Baroque painters included Rembrandt van Rijn , Johannes Vermeer , and Peter Paul Rubens . Their mastery of the medium was sought after by royal houses all over Europe. So great were the talents of the Dutch painters that Carl Klaus and Victoria Charles remarked ‘he [Rubens] is the only one who came near to Michelangelo in acting out drama’ and that “as a colourist, Rubens even perhaps overshadowed Michelangelo”.

Rivaling with the Dutch and Spanish artists of the caliber of Diego Velazquez , Italian Baroque painters were imbued with the legacy of Renaissance and Mannerist style. Two of the leading painting schools in Italy were the so-called ‘eclecticism’ of the Carracci family and their academy on the one hand, and Naturalism on the other – a revolutionary style founded by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, which broke the barriers between religious and popular art and avoided the idealization of religious or classical figures, depicting to also ordinary living men and women in contemporary clothing.

Baroque sculpture

Many great Baroque artists were architects as well as sculptors, and common traits can be seen in their oeuvre. A key similarity is the rejection of straight lines, resulting in increasingly pictorial sculptures where movement and expression are emphasized.

Baroque sculpture was primarily concerned with the representation of Biblical scenes spurred by the church but also by the beliefs of the sculptors themselves, as many worked on uncommissioned portrayals of biblical epics as well. Be it scenes from the old or new testaments, the desire of most Baroque sculptors was to portray pathos, as well as movement. The leading figure of Baroque sculpture was certainly Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Baroque architecture

At the start of the 17 th century, Italian architects were the dominant talents of Europe. Immense competition for the contracts offered by churches and the Vatican between Gian Luca Bernini, Francesco Borromini, Baldassare Longhena and others drew the rest of Europe’s attention, soon spreading the style across the continent. Royal courts were desperate to commission projects from the great Italian architects. Baroque architecture is characterized by intricate details and extreme decoration. Elements of Renaissance architecture were made grander and more theatrical, emphasized by optical illusions and the advanced use of trompe-l’œil painting. With the beginning of the 18th century, the European architectural focus shifted to France. There Jules Hardouin-Mansart broke away from the Baroque style and reverted to classicism, while Charles Le Brun brought the style and its traditions to new heights with his designing of the Galerie des Glaces in the Palace of Versailles.

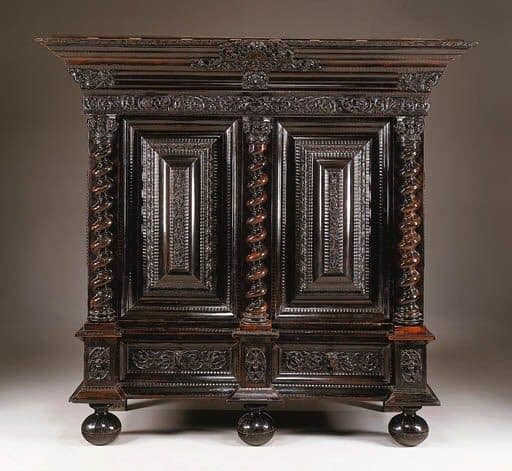

Baroque furniture

Inspired by the Asian decorative techniques brought back to Europe by Dutch, Portuguese, and English traders and explorers in the early 17 th century, the furniture makers of the Low Countries (Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg) combined these new techniques with those from the Renaissance to satisfy the needs and wishes of their customers. This technical progress then spread to the other furniture-making hubs of France, Germany, England, and Italy. Twisted columns, ornate details, foreign or domestic woods, and heavy gilds of varying metals all defined baroque furniture, all put together in an effort to create a harmony of movement and singularity.

Unlike the other art mediums of the Baroque period, the Baroque furniture style was limited to the 17 th century. Thereafter, furniture was dominated by the lavish tastes of King Louis XV of France who, with his craftsmen, developed the Regence and Rococo styles. The king’s taste soon became the rest of Europe’s taste, even in England where furniture makers tried to resist the asymmetrical designs of Rococo.

Baroque music

The baroque era was a time of musical innovation. Today baroque music is world-famous for the German composers George Fredrich Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach, but at the time Italian composers dominated the scene. Their legacy lives on through the music of Antonio Vivaldi, Claudio Monteverdi, Arcangelo Corelli, and their expressive scores. In order to create music on par with the classical Greek and Roman dramas of the past, Italian composers implemented new ways of playing and introduced new aspects of composition. Seeking dynamics and emotion in the place of regal static-ness, they developed a new musical language that enabled great dramatic interpretation. Most of this musical language is still used to this day, and also forms such as cantata, concerto, sonata, sinfonia, and opera originated in the baroque period.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn more about other essential art movements and styles: Art Deco Dadaism Impressionism

Discover & Buy Contemporary Art

The Baroque style

The Baroque is a highly ornate and elaborate style of architecture, art and design that flourished in Europe in the 17th and first half of the 18th century. Originating in Italy, its influence quickly spread across Europe and it became the first visual style to have a significant worldwide impact.

A defining characteristic of the Baroque style was the way in which the visual arts of painting, sculpture and architecture were brought together, into a complete whole, to convey a single message or meaning.

Baroque art and design addressed the viewer's senses directly, appealing to the emotions as well as the intellect. It reflected the hierarchical and patriarchal society of the time, developing through and being used by those in power – the church, absolute rulers and the aristocracy – to persuade as well as impress, to be both rich and meaningful. Compared to the control and carefully balanced proportions associated with the Renaissance, Baroque is known for its movement and drama.

The first global style

Baroque's influence extended from Italy and France to the rest of Europe, and then travelled via European colonial initiatives, trade and missionary activity to Africa, Asia, and South and Central America. Its global spread saw Chinese carvers working in Indonesia, French silversmiths in Sweden and Italian hardstone specialists in France. Sculpture was sent from the Philippines to Mexico and Spain, whilst London-made chairs went all over Europe and across the Atlantic, and French royal workshops turned out luxury products that were both desired and imitated by fashionable society across Europe. However, as a style, Baroque also changed as it crossed the world, being adapted to new needs and local tastes, materials and contexts.

In China, the European pavilions were the grandest expressions of the Qing rulers' interest in the arts of Europe. These European-style palaces were part of the Yuanming Yuan or Old Summer Palace in Beijing, the Emperor Qianlong's summer residence. Designed by Jesuit priests, the pavilions – most of which were completed between 1756 and 1766 – were based on Baroque models and included grand fountains and statues. In the 1780s, a set of copperplate engravings depicting the European pavilions was commissioned. This album, a copy of which is in our collection , is an important visual record of the pavilions as they were destroyed by English and French troops in 1860.

A sense of drama

An important feature of Baroque art and design is its use of human figures. Represented as allegorical, sacred or mythological, these figures helped turn the work into a drama to convey particular messages and to engage the emotions of the viewer. They have a sense of realistic immediacy, as if they had been stopped in mid-action. Facial expression, pose, gesture and drapery were all used to add dramatic details.

A bust of King Charles II of England in our collection perfectly captures the drama of Baroque portraiture. Portrayed in an animated fashion, his head is turned to one side and an elaborate wig cascades down over his lace cravat and billowing drapery. Such grand Baroque images of monarchs and powerful aristocrats were more common in 17th-century France than in England but Charles had spent much of his youth in mainland Europe and favoured European artists. The bust is in the tradition of flamboyant and imposing portraits of monarchs, and would have unambiguously asserted the King's status.

The performance of architecture

Baroque buildings were also dynamic and dramatic, both using and breaking the rules of classical architecture. Inside, the architecture echoed theatrical techniques – painted ceilings made rooms appear as if they were open to the sky and hidden windows were used to illuminate domes and altars.

Again, the design was used to convey specific meanings and emotions. Papal Rome became a key site for religious Baroque architecture. An example of the Baroque's theatricality can be found in Gianlorenzo Bernini 's (1598 – 1680) design for St Peter's Square. Its grand, imposing curved colonnades, centred on an obelisk, are used to both overwhelm the visitor and to bring them into the church's embrace.

Baroque architecture also shaped the way the public spaces of the city appeared. Public celebrations played an important role in the political life of a nation. Typically, such events took place out of doors and were elaborately designed spectacles. Urban squares such as Piazza Navona in Rome and Place Louis-le-Grand (now Place Vendôme) in Paris were the backdrop for firework displays, lavish theatrical performances and processions in elaborate and expensive costumes.

Imposing architecture was also used to reinforce the power of absolute rulers, such as with the Palace of Versailles, in France – the most imitated building of the 17th century. In 1717, the Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger compiled a "treatise on the decoration of interiors, for all kinds of royal residences, and others of distinction in both town and country", based on his own travel notes. One of the most expensive, recent innovations he recorded was the presence of mirrors so large they covered entire walls. He also noted the use of glass over the chimneypiece in the King's Chamber at Versailles.

Marvellous materials

A fascination with physical materials was central to the Baroque style. Virtuoso art objects made of rare and precious materials had long been valued and kept in special rooms or cabinets, alongside natural history specimens, scientific instruments, books, documents and works of art. However, during the Baroque period, the birth of modern science and the opening up of the world beyond Europe brought an increasingly serious interest in the nature and meaning of these exotic materials. Rarities such as porcelain and lacquer from East Asia became fashionable and were imitated in Europe. New techniques, such as marquetry (the laying of veneers of differently coloured woods onto the surface of furniture), developed by French and Dutch cabinet-makers and learned from them elsewhere, were also developed.

The value attached to such materials can be seen in a porcelain cup from our collection. Made between 1630 and 1650 in China originally as a writing-brush jar, it later had extravagant silver-gilt mounts added in London, which transformed the brush jar into a luxurious, decorative two-handled cup and cover.

Baroque ornament

Representations of the natural world, as well as motifs derived from human and animal forms, were popular decorative features. The most widespread form of Baroque floral decoration was a running scroll, often combined with acanthus – a stylised version of a real plant of the same name. A late 17th-century tankard in our collection features lavish floral decoration. The leaves of the flowers have been turned into scrolling foliage, while the flowers themselves have striped petals, likely to represent a tulip, another key motif of Baroque art.

The auricular style, which featured soft, fleshy abstract shapes, also emerged in the early 17th century, creating an effect that was ambiguous, suggestive and bizarre. In fact, the term 'Baroque' was a later invention – 'bizarre' was one of the words used at the time for the style we associate as Baroque today.

The theatre was a setting for magnificent productions of drama, ballet and opera – a new art form at that time. With their ornate costumes, complex stage sets and ingenious machinery, these performances created wonder and awe. Theatre was popular both with the public and at court. Written by Jean-Baptiste Lully for the French court of Louis XIV (reigned 1643 – 1715), the opera Atys was such a favourite with the King that it became known as "The King's Opera". Our collection includes a pen and ink design for the costume of the character Hercules in Atys . He is shown in a ballet pose, wearing a Roman-style costume, and identified by his club and lion skin.

Theatre also played a role in the power struggles between European courts. Rulers vied to outdo each other in the magnificence of their productions. In France, theatre and opera also became a key element of Louis XIV's cultural policy, which was used to control the nobility and express his power and magnificence. In the early 18th century, the theatre building itself acquired new importance as proof of courtly, civic or technological power. The resulting new buildings across Europe established the theatre in the form we know today.

However, by the mid-18th century, the Baroque style seemed increasingly out of step with the mood of the time, which placed increasing emphasis on reason and scientific enquiry. Baroque was criticised as an "immoral" style and art and design turned away from its use of emotion, drama and illusion, returning to a simpler style inspired by classical antiquity. It was only in the late 19th century that the style began to be critically reappraised once more.

- Share this article

Collections

Explore the range of exclusive gifts, jewellery, prints and more. Every purchase supports the V&A

Painted mirror, probably by Antoine Monnoyer, 1710 – 20, England. Museum no. W.36:1-3-1934. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Baroque rome.

The Denial of Saint Peter

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi)

Bust-Length Portrait of a Woman (recto); Bust-Length Study of a Girl (verso)

Agostino Carracci

Harpsichord

Michele Todini , designer

Barberini Cabinet

Galleria dei Lavori, Florence

Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633)

Giuliano Finelli

The Abduction of the Sabine Women

Nicolas Poussin

The Coronation of the Virgin

Annibale Carracci

The Preaching of John the Baptist

Bartholomeus Breenbergh

Marcantonio Pasqualini (1614–1691) Crowned by Apollo

Andrea Sacchi

Saint John the Baptist Preaching

Mattia Preti (Il Cavalier Calabrese)

Queen Esther Approaching the Palace of Ahasuerus

Claude Lorrain (Claude Gellée)

The Fall of the Giants

Salvator Rosa

The Lamentation

Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri)

Holy-water stoup with relief of Mary of Egypt

Giovanni Giardini

Pope Alexander VII (Fabio Chigi, 1599–1667; reigned 1655–67)

Melchiorre Cafà

The Martyrdom of Saint Cecilia (Cartoon for a Fresco)

Pope Innocent X

After a composition by Alessandro Algardi

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2003

In the seventeenth century, the city of Rome became the consummate statement of Catholic majesty and triumph expressed in all the arts. Baroque architects, artists, and urban planners so magnified and invigorated the classical and ecclesiastical traditions of the city that it became for centuries after the acknowledged capital of the European art world, not only a focus for tourists and artists but also a watershed of inspiration throughout the Western world.

Urbanism and Architecture Although Rome gained in magnificent buildings and monuments during the Renaissance , it also suffered the attacks of Reformation theologians and invading armies; although home to major centers of religious pilgrimage and venerable remains of Imperial Rome, the city’s haphazard street system impeded circulation and diminished spectators’ vantage on its monuments. To remedy this situation, Pope Sixtus V (r. 1585–90) promoted his vision of “Roma in forma sideris,” that is, Rome in the shape of a star. He engaged Domenico Fontana (1543–1607) and other planners to lay out processional avenues linking the great basilicas, such as Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni in Laterano, with other strategic points; routes emanated like the rays of a star from focal piazzas marked with Egyptian obelisks brought to Rome in ancient times.

Today the papacy controls only the small zone known as Vatican City, but its domain in former times was not so restricted, and papal patronage transformed the entire city. Three energetic popes, Urban VIII (r. 1623–44), Innocent X (r. 1644–55), and Alexander VII (r. 1655–67), charged the versatile talents of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), Francesco Borromini (1599–1667), and Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669) with commissions meant to monumentalize and beautify areas all over Rome. Bernini executed several projects at the Basilica of Saint Peter, the center of papal authority: he created the superb bronze baldacchino (canopy) over the high altar for Urban VIII, and for Alexander VII he designed the sculptural adornment of the chair of Peter in the apse and the sweeping round colonnades that frame the facade. Nearby, Bernini designed the Ponte Sant’Angelo, a bridge across the Tiber embellished with angels carrying the instruments of Christ’s passion, which eased movement between the Vatican and the important commercial area across the river.

All the popes used the official residence in the Vatican, but they also lavished attention on their own palaces in other parts of the city. Innocent X, for example, developed the Piazza Navona, commissioning Borromini to design facades for the Church of Sant’Agnese in Agone and for his palace next door, and engaging Bernini to create the spectacular Fountain of the Four Rivers, whose gushing waters, colossal sculpture, and crowning obelisk form the centerpiece of the square. The introduction of fountains and monumental stairways throughout the city induced pedestrians not only to move easily from place to place but also to linger in beautified transitional spaces. A prime example is the Spanish Steps, a symmetrical system of landings and curving staircases that connect two neighborhoods formerly divided by an impassably steep hill. Although several artists proposed solutions to the problem, the Steps were finally built to the elegant design of Francesco De Sanctis and completed in 1726.

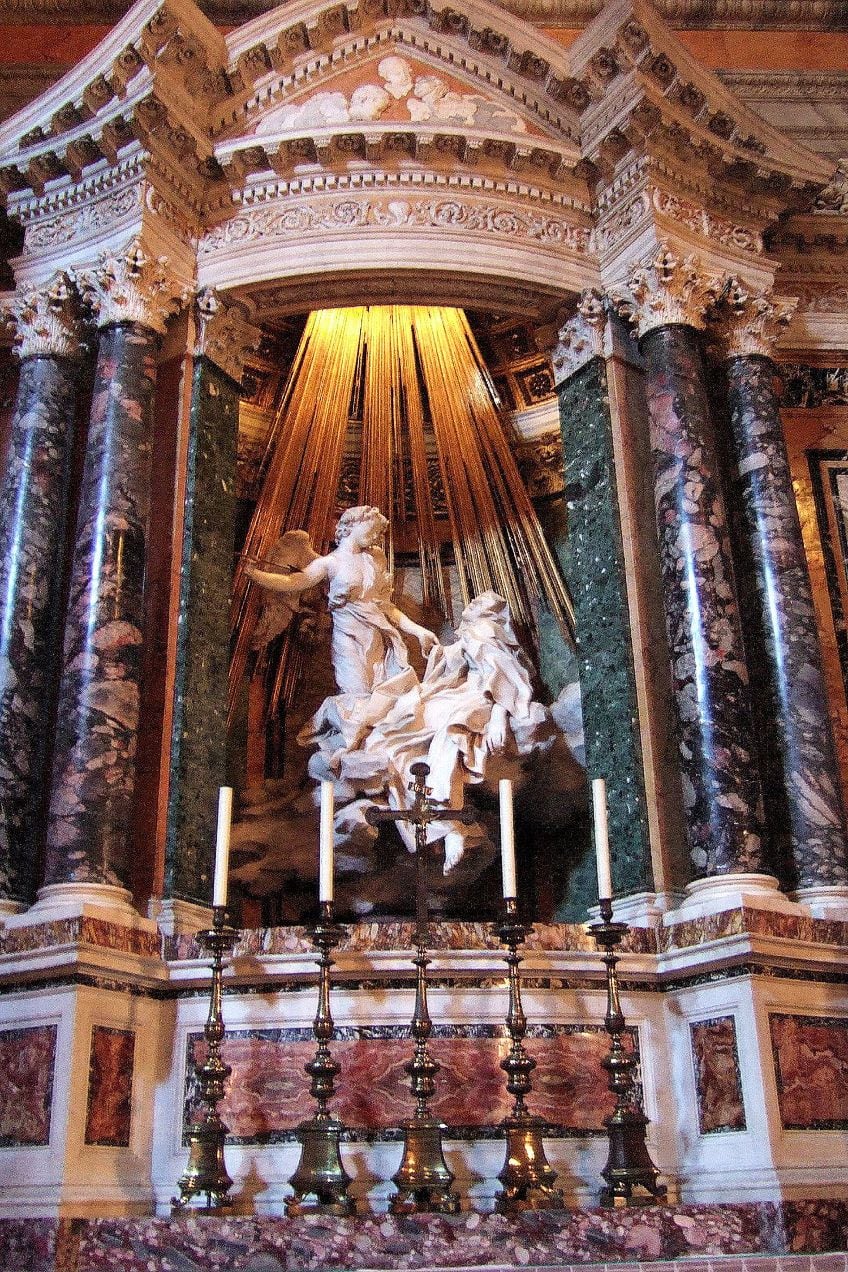

The Building and Embellishment of Baroque Churches Throughout the seventeenth century, churches were constructed along Rome’s newly cut thoroughfares, and existing buildings were modified in keeping with Baroque taste. Borromini designed innovative churches, such as Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza and San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, in which complex harmonies of curved and rectangular forms create surprising, sculptural interiors. Borromini also remodeled the ancient basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, incorporating stuccowork by Alessandro Algardi, gilding, and an abundance of colored marbles, materials lavishly applied in many other Roman interiors. At the Cornaro Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Bernini used sculpture, architectural elements, and hidden light sources to transform a family chapel into a theatrical re-creation of Saint Teresa of Ávila ecstatically receiving an angel with an arrow of divine love. As a result of Pietro da Cortona’s new convex facade for Santa Maria della Pace, the little church seems to swell into the piazza outside and beckon to the viewer turning down the street in front.

Painters also embraced the challenge to create integrated environments ( un bel composto ) meant to heighten religious experience. By 1600, in three famous paintings illustrating the life of Saint Matthew, Caravaggio made the light represented within each picture consistent with the actual illumination of the chapel where the pictures were to hang. In the 1640s and 1650s, Pietro da Cortona adorned the vaults of Santa Maria in Vallicella with spectacular portrayals of the Trinity in Glory and the Assumption of the Virgin, in which monumental groups of figures seen from below enact heavenly events as though occurring in the viewer’s own experience. Pietro’s ceiling frescoes set the standard for many later masterpieces, including the radiant Triumph of the Name of Jesus (1676–79) in Il Gesù, the principal church of the Jesuit order, painted by Giovanni Battista Gaulli, and Andrea Pozzo’s Glory of Saint Ignatius (1691–94) in the Church of Sant’Ignazio, where the ceiling seems to open to reveal the saint ascending into heaven over a hovering assembly of angels and personifications.

Painting and the Decorative Arts The concentration of willing patrons in Rome attracted artists from all over Europe, and painters continued to argue the primacy of technique based alternatively on drawing ( disegno ) or coloring ( colorito ) . Among the artists hailed for reconciling the two approaches was the Bolognese-born Annibale Carracci (1560–1609), who applied his gifts as both draftsman and colorist to the emerging genre of landscape as well as traditional religious subjects; his Coronation of the Virgin ( 1971.155 ), for instance, combines a compositional scheme derived from Michelangelo with subtle lighting in the spirit of Titian . In a famous public debate probably conducted in 1636, Andrea Sacchi (ca. 1599–1661), whose Marcantonio Pasqualini Crowned by Apollo ( 1981.317 ) displays his reliance on drawing, made claims for compositions with few figures and pure contours, while Pietro da Cortona opposed him, advocating instead great assemblies of figures and freer brushwork. Sacchi’s influence is visible in the work of the French painter Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), who made his career in Rome, painting scenes from biblical and classical history; in his Abduction of the Sabine Women ( 46.160 ), he uses bold colors, sharp contours, and figures derived from Greco-Roman sculpture , all characteristic of his art.

The exuberant theatricality of seventeenth-century projects on an urban scale also animates smaller examples of sculpture and decorative art. Bernini’s early Bacchanal ( 1976.92 ) includes figures in characteristic twisting poses in a composition different from every point of view. Giovanni Giardini’s holy-water stoup ( 1995.110 ) depicts Saint Mary of Egypt in a concave silver panel framed in lapis lazuli, and Michele Todini’s harpsichord ( 89.4.2929 ) carried by tritons of gilded wood is conceived as the centerpiece of a mythic musical contest.

Sorabella, Jean. “Baroque Rome.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/baro/hd_baro.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Barberini, Maria Giulia, et al. Life and the Arts in the Baroque Palaces of Rome: Ambiente Barocco . Exhibition catalogue. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Brown, Beverly Louise, ed. The Genius of Rome, 1592–1623 . Exhibition catalogue. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2001.

Haskell, Francis. Patrons and Painters: A Study in the Relations between Italian Art and Society in the Age of the Baroque . 2d ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

Krautheimer, Richard. The Rome of Alexander VII, 1655–1667 . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Additional Essays by Jean Sorabella

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe .” (April 2011)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe .” (August 2007)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Venetian Color and Florentine Design .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D. .” (May 2010)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Baroque and Later Art .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe .” (originally published October 2001, last revised March 2013)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Interior Design in England, 1600–1800 .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Vikings (780–1100) .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Birth and Infancy of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Carolingian Art .” (December 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Ottonian Art .” (September 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Ballet .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Opera .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Grand Tour .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (1571–1610) and His Followers

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680)

- Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)

- The Nude in Baroque and Later Art

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Annibale Carracci (1560–1609)

- Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

- Architecture in Renaissance Italy

- Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples

- The Byzantine City of Amorium

- Domenichino (1581–1641)

- The French Academy in Rome

- Gardens of Western Europe, 1600–1800

- The Golden Harpsichord of Michele Todini (1616–1690)

- The Grand Tour

- The Idea and Invention of the Villa

- Images of Antiquity in Limoges Enamels in the French Renaissance

- Mannerism: Bronzino (1503–1572) and his Contemporaries

- The Papacy and the Vatican Palace

- Poets, Lovers, and Heroes in Italian Mythological Prints

- The Reformation

- Roman Copies of Greek Statues

- Still-Life Painting in Southern Europe, 1600–1800

- Venetian Color and Florentine Design

- Violin Makers: Nicolò Amati (1596–1684) and Antonio Stradivari (1644–1737)

- Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Balkan Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- Ancient Egyptian Art

- Ancient Greek Art

- Ancient Roman Art

- Architectural Element

- Architecture

- The Assumption of the Virgin

- Baroque Art

- Central Italy

- Christianity

- Classical Period

- Classical Ruins

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Gilded Wood

- Lapis Lazuli

- Musical Instrument

- Mythical Creature

- Oil on Canvas

- Plucked String Instrument

- Preparatory Study

- Religious Art

- Renaissance Art

- Saint John the Baptist

- Sculpture in the Round

- Southern Italy

- Virgin Mary

Artist or Maker

- Algardi, Alessandro

- Amati, Andrea

- Amati, Nicolò

- Bernini, Gian Lorenzo

- Bernini, Pietro

- Breenbergh, Bartholomeus

- Cafà, Melchiorre

- Carracci, Agostino

- Carracci, Annibale

- Carracci, Ludovico

- Domenichino

- Finelli, Giuliano

- Francesco Del Tuppo

- Gentileschi, Artemisia

- Giardini, Giovanni

- Lorrain, Claude

- Luti, Benedetto

- Onofri, Basilio

- Pietro da Cortona

- Poussin, Nicolas

- Preti, Mattia

- Reiff, Jacob

- Rosa, Salvator

- Sacchi, Andrea

- Solimena, Francesco

- Todini, Michele

Online Features

- Viewpoints/Body Language: “Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children”

Overview of Baroque Style in English Prose and Poetry

Definition and Examples

sebastian-julian/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In literary studies and rhetoric , a style of writing that is extravagant, heavily ornamented, and/or bizarre. A term more commonly used to characterize the visual arts and music, baroque (sometimes capitalized) can also refer to a highly ornate style of prose or poetry.

From the Portuguese barroco "imperfect pearl"

Examples and Observations:

"Today the word [ baroque ] is applied to any creation that is exceedingly ornate, intricate, or elaborate. Saying a politician delivered a baroque speech wouldn't necessarily be a compliment." (Elizabeth Webber and Mike Feinsilber, Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Allusions . Merriam-Webster, 1999)

Characteristics of Baroque Literary Style

" Baroque literary style is generally marked by rhetorical sophistication, excess, and play. Self-consciously remaking and thus critiquing the rhetoric and poetics of the Petrarchan, pastoral, Senecan, and epic traditions, baroque writers challenge conventional notions of decorum by using and abusing such tropes and figures as metaphor , hyperbole , paradox , anaphora , hyperbaton , hypotaxis and parataxis , paronomasia , and oxymoron . Producing copia and variety ( varietas ) is valued, as is the cultivation of concordia discors and antithesis --strategies often culminating in allegory or the conceit ." ( The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics , 4th ed., ed. by Roland Green et al. Princeton University Press, 2012)

Cautionary Notes to Writers

- "Very skilled writers will sometimes use baroque prose to good effect, but even among successful literary authors, the vast majority avoid flowery writing. Writing is not like figure skating, where flashier tricks are required to move up in competition. Ornate prose is an idiosyncrasy of certain writers rather than a pinnacle all writers are working toward." (Howard Mittelmark and Sandra Newman, How Not to Write a Novel . HarperCollins, 2008)

- " [B]aroque prose demands tremendous rigor from the writer. If you stuff a sentence, you must know how to do so with complementary ingredients--ideas that do not compete but play off one another. Above all, as you edit , concentrate on determining when enough is enough." (Susan Bell, The Artful Edit: On the Practice of Editing Yourself . W.W. Norton, 2007)

Baroque Journalism

"When Walter Brookins flew a Wright plane from Chicago to Spingfield in 1910, a writer for the Chicago Record Herald reported that the plane drew out great crowds at every town along the way ... In baroque prose that captured the excitement of an era, he wrote:

The sky-gazers looked on in astonishment as the great artificial bird bore down the heavens. . . Wonderment, surprise, absorption were written on every visage . . . a machine of travel that combined the speed of the locomotive with the comfort of the automobile, and in addition, sped through an element until now navigated only by the feathered kind. It was, in truth, the poetry of motion, and its appeal to the imagination was evident in every upturned face."

(Roger E. Bilstein, Flight in America: From the Wrights to the Astronauts , 3rd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001)

The Baroque Period

"Students of literature may encounter the term [ baroque ] (in its older English sense) applied unfavorably to a writer's literary style; or they may read of the baroque period or 'Age of Baroque' (late 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries); or they may find it applied descriptively and respectfully to certain stylistic features of the baroque period. Thus, the broken rhythms of [John] Donne's verse and the verbal subtleties of the English metaphysical poets have been called baroque elements. . . . 'Baroque Age' is often used to designate the period between 1580 and 1680 in the literature of Western Europe, between the decline of the Renaissance and the rise of the Enlightenment." (William Harmon and Hugh Holman, A Handbook to Literature , 10th ed. Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006)

René Wellek on Baroque Clichés

- "One must, at least, admit that stylistic devices can be imitated very successfully and that their possible original expressive function can disappear. They can become, as they did frequently in the Baroque , mere empty husks, decorative tricks, craftsman's clichés ...

- "If I seem to end on a negative note, unconvinced that we can define Baroque either in terms of stylistic devices or a particular worldview or even a peculiar relationship of style and belief, I would not like to be understood as offering a parallel to Arthur Lovejoy's paper on the 'Discrimination of Romanticisms.' I hope that baroque is not quite in the position of 'romantic' and that we do not have to conclude that it has 'come to mean so many things, that by itself, it means nothing...' "Whatever the defects of the term baroque, it is a term which prepares for synthesis, draws our minds away from the mere accumulation of observations and facts, and paves the way for a future history of literature as a fine art." (René Wellek, "The Concept of Baroque in Literary Scholarship," 1946, rev. 1963; rpt. in Baroque New Worlds: Representation, Transculturation, Counterconquest , ed. by Lois Parkinson Zamora and Monika Kaup. Duke University Press, 2010)

The Lighter Side of Baroque

Mr. Schidtler: Now can anyone give me an example of a Baroque writer? Justin Cammy: Oh, sir. Mr. Schidtler: Mm-hm? Justin Cammy: I thought all writers were broke. ("Literature." You Can't Do That on Television , 1985)

- A List of Every Nobel Prize Winner in English Literature

- Definition of Belles-Lettres in English Grammer

- style (rhetoric and composition)

- An Introduction to Baroque Architecture

- Stylistics and Elements of Style in Literature

- Plain Style in Prose

- 12 Classic Essays on English Prose Style

- Figure of Sound in Prose and Poetry

- What Is Euphony in Prose?

- The Writer's Voice in Literature and Rhetoric

- Comma Splices

- Word Choice in English Composition and Literature

- Copia and Copiousness in Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples in Rhyme in Prose and Poetry

- Imitation in Rhetoric and Composition

- Definitions and Discussions of Medieval Rhetoric

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Europe 1300 - 1800

Course: europe 1300 - 1800 > unit 9, baroque art, an introduction.

- How to recognize Baroque art

- Introduction to the Global Baroque

- What is genre painting?

- Francis Bacon and the scientific revolution

- A beginner's guide to the Baroque

Rome: From the “Whore of Babylon” to the resplendent bride of Christ

The art of persuasion: to instruct, to delight, to move, the catholic monarchs and their territories, the protestant north, "baroque”—the word, the style, the period, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Introduction to the Global Baroque

The tremendous diversity of baroque art.

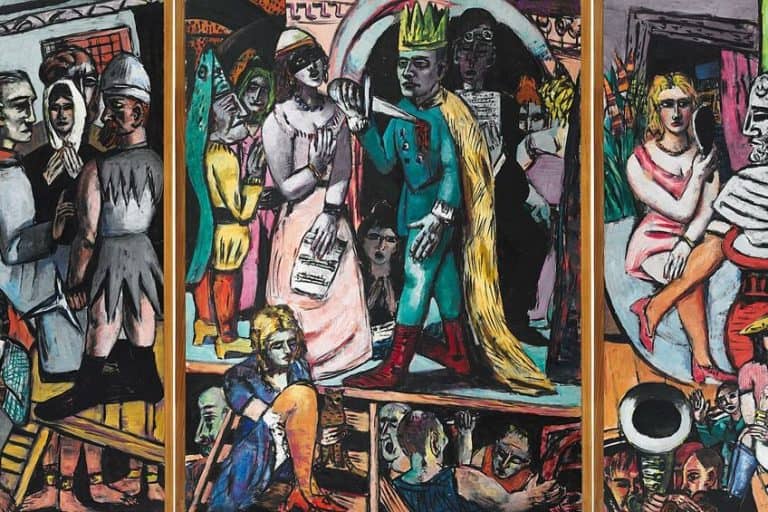

A small sample of artworks showcases the astonishing diversity that characterizes what we now know as “Baroque” art.

Left: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Calling of St. Matthew , oil on canvas, c. 1599–1600 (Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); center: Miguel Cabrera, The Virgin of the Apocalypse , 1760, oil on canvas, 352.7 x 340 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Luisa Roldán, Jesus of Nazareth , 1692–1700, polychromed wood, 159 cm (Convento de Madres Clarisas (Nazarenas), Sisante)

A beam of light falls dramatically over a group of dashing rogues in Caravaggio’s Calling of Saint Matthew . In Miguel Cabrera’s Virgin of the Apocalypse , an oversized Virgin Mary steps triumphantly over a dragon, creating a dynamic diagonal effect. Luisa Roldán’s Jesus of Nazareth awes the viewer with its astoundingly realistic likeness.

Left: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–52, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); center: Louis le Vau, André le Nôtre, and Charles le Brun, Palace of Versailles, 1664–1710 (photo: Jean-Christophe BENOIST, CC BY 3.0); right: Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Blacks, 18th century, Ouro Preto, Brazil (photo: Juliana Bruder, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The ecstasy of Bernini’s Saint Teresa unravels theatrically in a rapture of folds and ascending movement. A façade of symmetrical, repetitive elements imposes with its restrained classicism at Versailles . Two connected ovals and their undulating walls test the limits of formal experimentation at José Pereira dos Santos’s Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Blacks in Ouro Preto (Brazil).

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, also known as il Baciccio, The Triumph of the Name of Jesus , ceiling fresco, 1672–85, Church of Il Gesù, Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Main altar inside Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Javier Castañón, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The ceiling of the Church of the Gesù in Rome opens up into an apotheosis of limitless otherworldly heavens, and the altar of the Church of Santa Prisca and San Sebastian in Mexico compulsively merges disparate forms into a horror vacui of “ornamental fervor.” [1]

Rembrandt, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer , 1653, oil on canvas, 143.5 x 136.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait , c. 1633, oil on canvas, 74.6 x 65.1 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.); Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Las Meninas, c. 1656, oil on canvas, 125 1/4 x 108 5/8″ / 318 x 276 cm ( Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid )

While the Greek philosopher Aristotle introspectively contemplates a bust of Homer in Rembrandt’s Aristotle , the likeness of Dutch painter Judith Leyster greets the viewer with vibrant immediacy in her self-portrait. Members of the Spanish court make reality enter fiction in Velázquez’s Las Meninas .

“Baroque” is here understood as the art produced through the 17th and much of the 18th centuries in a broad range of geographies across the globe. But what do all these disparate works have in common? What does “Baroque” mean? And can we speak of it as being global?

Baroque: limitations and possibilities of an art historical concept

The “Baroque” is one of the most disputed styles of art history, and the history of the term is just as convoluted as the art that it describes. The origins of the term are not entirely clear, but the most accepted (and evocative) theory is that it originated from a term ( barrôco in Portuguese, barrueca in Spanish) describing a specific type of irregular pearl: in other words, a natural but artificial-looking, precious but misshapen object. As you probably guessed, when applied to art, the word “Baroque” can connote a certain measure of distortion and imperfection. But this is an inaccurate characterization that assumes a unified style. As shown in the examples above, there are many versions of the so-called Baroque.

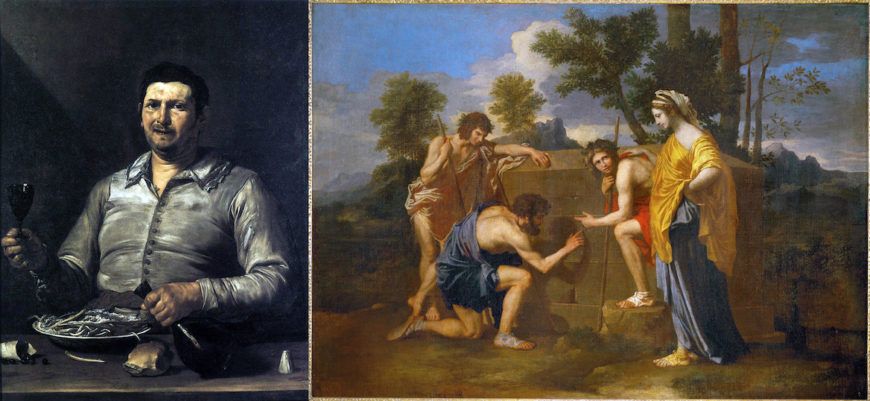

An example of Baroque realism (left) contrasted with an example of Baroque classicism (right). Left: Jusepe de Ribera, Sense of Taste , 1613–16, oil on canvas, 117 x 88 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford); right: Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego, 1637–38, oil on canvas, 87 x 120 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Consider the ordinary figures, stark realism, and dramatic tenebrism of Diego Velázquez’s The Waterseller of Seville or Jusepe de Ribera’s Allegory of Taste —prime examples of what is sometimes referred to as “Baroque realism” alongside the “Baroque classicism” of Nicolas Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego , an image set in ancient Greece with quasi-archaeological accuracy.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Cathedra Petri (or Chair of St. Peter) , gilded bronze, gold, wood, stained glass, 1647–53 (apse of Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, Rome, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

And now consider the stage quality of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Cathedra Petri —a chair (that of Saint Peter) that appears to float in the air through a combination of painting, sculpture, architecture, glass, and light. It characterizes yet another mode, Bernini’s “Theatrical Baroque” (Bernini was in fact a stage designer). To complicate matters, consider how many works conjoin these various Baroque modes at once: Juan Sánchez Cotán’s Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber combines the hyper-realistic depiction of fruits and vegetables with the theatricality of staging these objects under dramatic lighting against a dark background, as well as an erudite classical reference: like most Baroque still life painters, Cotán was probably emulating the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis, who was known through written accounts for the deceptively illusionistic powers of his paintings.

Juan Sánchez Cotán, Still Life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber , c. 1602, oil on canvas, 68.9 cm x 84.46 cm (The San Diego Museum of Art)

Like other art historical categories such as Gothic or Romanesque , the notion that there was a Baroque style originated from unsympathetic critics of a later period. More precisely, in the second half of the 18th century, when it started to refer to art of the previous century, the term “Baroque” designated art which was “not in accord with the rules of proportions.” [2] I n the 19th century, it was associated with notions of bizarreness, and then finally became associated with a distorted and degenerate version of Renaissance ( or more precisely of Italian Renaissance ) art.

For these reasons, some scholars reject the use of Baroque as a valid artistic category: it is anachronistic—people at the time didn’t refer to art of the period as being “Baroque”—and it can carry pejorative connotations. Ultimately, as with almost all such examples of a period style—a label created artificially and after the fact to refer to the defining characteristics of art from a particular historical period—“Baroque” is necessarily reductive.

So, why are we using it here?

Despite its flaws, most scholars have embraced the “Baroque” as a useful category to give coherence to the striking variety of artworks from this period. The most influential scholar was Heinrich Wölfflin, who offered the first positive assessment of the Baroque in his Principles of Art History (1915), though he considered it primarily in the Italian context. To demonstrate that the Baroque was distinct from and just as valuable as the Renaissance, Wölfflin devised an influential comparative formal analysis—much like you might see in an art history class today , with images side-by-side. By closely looking at examples of Renaissance and Baroque art, he concluded that Baroque works were characterized by:

- painterliness—loose brushwork, blurred contours, and color over line;

- expansiveness—the impression that the artwork continues beyond its borders, oftentimes through the use of diagonals; and

- uncertainty—the emphasis on how things appear instead of how they actually are, that is the prioritizing of pictorial effects over legibility of form.

In highlighting these Baroque traits, Wölfflin was implying that tension, contradiction, and even imperfection were valuable forms of artistic expression. To him, this was in opposition to Renaissance linearity (the preference for clearly distinct forms perfectly defined by line), self-containment (the way a work is contained within its frame), and clarity ( allows one to clearly distinguish each element in a work at once).

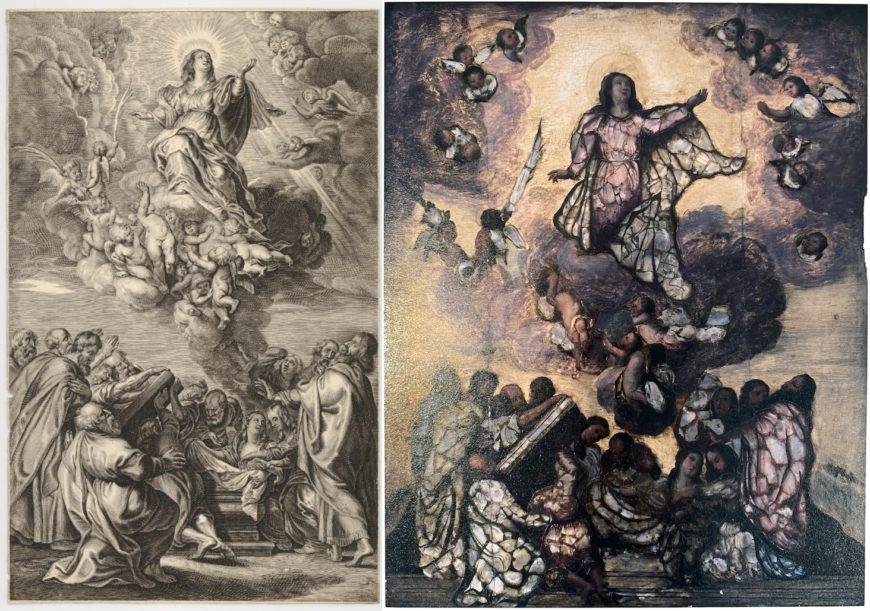

Left: Raphael, Madonna of the Goldfinch , 1505–6, oil on panel, 107 x 77 cm (Uffizi, Florence); right: Peter Paul Rubens, Assumption of the Virgin Mary , 1626, oil on panel, 490 cm x 325 cm, High Altar of the Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp, Province of Antwerp, Flanders, Belgium (photo: Rolf Kranz, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A comparison between Raphael’s Madonna of the Goldfinch from the Renaissance and Peter Paul Rubens’s The Assumption of the Virgin from the Baroque illustrates Wölfflin’s categories. Raphael’s painting emphasizes defining lines, self-contained figures—notice how through her gaze and posture, the Virgin draws the composition inward rather than expanding it beyond the borders of the canvas— and spatial clarity. Rubens’s Assumption, on the other hand, displays painterly brushwork, prominent color, the blurring of contours, dynamic diagonals, and dramatic contrast of light and shadow. It also seems to project outward into the space of the viewer.

Annibale Carracci, Christ Appearing to Saint Peter on the Appian Way (also known as Domine quo vadis ), 1601–02, oil on wood, 77.4 x 56.3 cm (The National Gallery, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Wölfflin’s analysis was far from perfect—for example, he excluded the more restrained and classically inspired works of artists such as Annibale Carracci or Nicolas Poussin because they didn’t fit his idea of the Baroque. More importantly, he was so focused on visual elements that he didn’t pay enough attention to social and cultural factors. Many scholars after Wölfflin addressed these issues: from Erwin Panofsky’s view of the Baroque as a phenomenon unique to Counter-Reformation Italy (the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation ), to John Rupert Martin’s definition of the Baroque as a mentality with shared attitudes towards the world.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Holofernes , c. 1612–13, oil on canvas, 199 x 162.9 cm (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In Martin’s view, features as distinctive of the Baroque as Naturalism (the imitation of nature) and Psychology (the interest in human passions) are related to developments in science (the direct observation of nature promoted by thinkers such as Francis Bacon and Johannes Kepler) and philosophy (the study of emotions of philosophers such as René Descartes) such as they appear, for example, in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes .

San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru, 17th century (photo: courtesy World Monuments Fund)

What about art outside of Europe?

However, in their discussions, none of these earlier critics considered art produced outside of Europe. By contrast, in the past few decades, scholars have started to recognize the Baroque as a global phenomenon—some even considering it the first truly global style. Scholars of Latin American art and culture have pointed out that Wölfflin’s recognition of difference and paradox—the tensions, contradictions, and imperfections discussed above—as essential features of Baroque aesthetic is useful to think about the Baroque in all its global diversity and complexity (even though applying a European category to the rest of the world is also problematic). For example, consider the church of San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas in Peru, which features a combination of European, Islamic, and Indigenous Andean elements. In a way, such a work defies categorization. But it also embodies quite neatly the Baroque elements of difference and paradox singled out by Wölfflin.

Some scholars have even embraced the Baroque ahistorically—that is, suggesting that we can find a Baroque aesthetic across any time and space—but most recognize it as an array of styles that developed around the globe in a specific time period (c. 1585–1750) from very specific historical conditions—including the Counter-Reformation , the Scientific Revolution , the consolidation of absolutism , the rise of capitalism , the expansion of colonization—through which European countries exerted control over Indigenous populations—and globalization.

São Paulo , founded 1610, Diu, India (photo: Shakti, CC BY-SA 3.0)

What did it mean to be global in the Baroque?

In the 17th and 18th centuries, globalization meant connectedness across distant geographies, but not that every part of the globe was connected to each other. Rather, there were specific pathways shaped by the contours of religion, colonization, and trade, which themselves were closely linked. For example, the establishment of Portuguese colonies in India since the early 16th century facilitated the presence of religious missionaries such as the Jesuits , who in turn employed Hindu carvers to build extraordinary churches such as São Paulo in Diu, India.

The Jesuits were also largely responsible for the dissemination of European prints that were used as models for religious images in colonial contexts. But those who were forced into religious and artistic models were by no means passive receptors. Rather, they were active contributors who creatively transformed those models, forging, in turn, completely new and original versions of the Baroque.

Left: Schelte à Bolswert, The Assumption of the Virgin , 1630–90, engraving, 27.3 x 17.2 cm, after the painting by Rubens (The British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); right: Miguel González and/or Juan González, The Assumption of the Virgin , c. 1700, oil on panel with inlaid mother-of-pearl, 93 x 74 cm (private collection, Monterrey, Mexico)

For example, consider how Miguel González and/or Juan González’s The Assumption of the Virgin , one of the many Latin American works related to prints after the painting by Rubens of the same subject, transforms the European model into something distinct and unexpected through the use of mother-of-pearl inlay enconchado , an artistic technique which reflects both a longstanding tradition of Indigenous peoples in Mexico and Japanese namban lacquer work, and that through its shimmering effect emphasizes the divinity of the subject. [3]

One of pair of tulip vases as triumphal arches, from Greek A Factory (Adriaen Kocks, proprietor) attributed, c. 1690–1705 (Delft), tin-glazed earthenware, 29.5 x 30.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In case you are wondering, knowledge of Japanese traditions such as lacquerware in Mexico was possible through the effect of global trade. Although wide geographical networks had existed before, what made the Baroque truly globe-encompassing was not only the inclusion of new continents such as the Americas to the mix, but also the establishment of trade routes and chartered companies in which imperial powers systematically promoted and monopolized the exchange of goods.

These included:

- the India Run (the voyage made by the Portuguese between Lisbon and Goa, on the southwestern coast of India. from the 16th to the 19th centuries)

- the Manila Galleon (maintained by Spain between 1565–1815 to bring Asian goods —including the Japanese lacquer works that Mexican artists embraced in enconchado paintings such as the one mentioned above —across the North Pacific from Manila in the Philippines to Acapulco in New Spain, now Mexico),

- and the Dutch East and West India Companies ( VOC and GWC), which monopolized trade with Eurasia and Southern Africa and with West Africa and the Americas, respectively, during much of the 17th and 18th centuries.

These routes and companies moved exotic luxury objects such as Indian and Chinese fabrics , lacquer furniture, ivory figurines , porcelain, and spices across all the known continents. But most were also involved in the slave trade, adding a brutal aspect to this early modern globalization in the thousands of Africans who were forced into slavery in Europe and the Americas.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with Pearl Necklace , 1664, oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm (Staatliche Museen)

The wealth of materials, techniques, and especially the countless artists, artisans, and craftsmen of various origins who contributed to the creation of this global Baroque can’t be overestimated. Think about how the desire for Chinese porcelain in the Dutch Republic drove the production of delftware ( illustrated e arlier ) , a domestic version of the coveted ware (and in turn how the Chinese created new types of ceramics for European markets ), or how the “perfect red” attained with American cochineal dye became the color of royalty and nobility across Europe and the Americas.

Antonio de Pereda, Still Life with Ebony Chest, detail, 1652, oil on canvas, 80 x 94 cm (The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg)

Now consider the painstakingly rendered reflections bouncing off the Chinese vase in Jan Vermeer’s Girl with Pearl Necklace (shown earlier), the objects from across the globe set on display in Antonio de Pereda’s Still Life with Ebony Chest ; or the diaphanous muslins from Cambay (India) in Josefa de Óbidos’ Christ Child as Salvator Mundi .

Josefa de Ayala, Christ Child as Salvator Mundi , signed and dated “Josepha em Obidos 1680,” oil on canvas, Third Penitential Order of Saint Francis, Coimbra

Even more, think about objects as uniquely global as the Biombo with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse) (known as the Brooklyn Biombo , shown below), created in the circle of the González family. This luxurious object, commissioned in Mexico City by the viceroy of New Spain and probably displayed in the viceregal palace, is a reinterpretation of the Japanese folding screen or byōbu, with designs based on various European sources–including Dutch etchings and tapestry designs, and inlaid mother-of-pearl enconchado inspired by pre-contact Mexican and Japanese techniques.

Folding Screen (biombo) with the Siege of Belgrade (front), c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Repressive or liberating?

Folding Screen (biombo) with Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

The inlaid mother-of-pearl of the Brooklyn Biombo painting leads us back to the Baroque pearl metaphor mentioned earlier. The infamous pearl is particularly poignant to discussions of the global Baroque when we consider what these jewels meant in the early modern world and the many frictions involved in their transatlantic trade. Although pearls had been available and treasured as jewels in Europe for thousands of years, it was after Christopher Columbus’s voyages into the Caribbean (between 1492 and 1502), sponsored by the Spanish Catholic Monarchs, that pearls became emblematic of overseas imperial wealth. Such wealth involved the exploitation of pearl fisheries in the region through an enslaved labor force—first of Indigenous peoples, and later of Africans forcibly brought to the continent for that purpose. To twist the metaphor of the baroque pearl even further, we should add that the wonder, exuberance, and opulence that characterizes so many examples of the global Baroque often originated from violence, force, and coercion. Paradoxically, this violent global world witnessed artists of African descent, such as the painters Juan de Pareja and Juan Correa and the architect Antonio Francisco Lisboa (known as Aleijadinho ), thriving as professional artists in Spain, Mexico, and Brazil, respectively.

We can’t deny that one strand of the global Baroque is its Catholic, monarchical, and colonizing nature, but this doesn’t mean that there wasn’t room for artistic individuality, experimentation, or even dissent. Like the beautiful, unconventional, mutable forms and porous surfaces of the Baroque pearl, the forms and surfaces of Baroque artworks from across the globe reflect the Baroque styles’ countless permutations, as well as the overlapping histories and cultural encounters of those who created and enjoyed them.

[1] Robert Harbison, Reflections on Baroque (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), p. 127.

[2] Helen Hills, “The Baroque: The Grit in the Oyster of Art History,” in Helen Hills, ed. Rethinking the Baroque (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), p. 12.

[3] As Aaron Hyman has recently noted, while bearing an unmistakable resemblance to Rubens’ “original” painting, we should also consider how such a work may have been in dialogue with the many other colonial versions of the Rubens that already existed, forcing us to reconsider the primacy of the European model and the meaning of (baroque) originality. Rubens in Repeat: The Logic of the Copy in Colonial Latin America (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2021), pp. 6–10.

Additional resources

Learn more about the global baroque with two Reframing Art History chapters—” Secular matters of the global baroque ” and “ The sacred baroque in the Catholic world.”

Gauvin A. Bailey, Baroque and Rococo (London; New York, NY: Phaidon, 2012)

Timothy J. Brook, Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2009)

Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello, “The Global Lives of Things: Material Culture in the First Global Age.” In Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello eds., The Global Lives of Things: The Material Culture of Connections in the Early Modern World (Routledge, 2015), pp. 1–28.

Byron Hamman, “Interventions: The Mirrors of Las Meninas: Cochineal, Silver, and Clay.” The Art Bulletin vol. 92, issues 1/2 (2010), pp. 6–35.

Robert Harbison, Reflections on Baroque (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000)

Helen Hills, “The Baroque: The Grit in the Oyster of Art History.” In Helen Hills, ed. Rethinking the Baroque (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), pp. 11–36.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “ Introduction to the Spanish Viceroyalties in the Americas ” in Smarthistory, February 1, 2017, accessed January 6, 2022.

Aaron Hyman, Rubens in Repeat: The Logic of the Copy in Colonial Latin America (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2021)

José Antonio Maravall, Culture of the Baroque: Analysis of a Historical Structure (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986)

John Rupert Martin, Baroque (New York: Harper & Row, 1977)

Vernon Hyde Minor, Baroque and Rococo: Art and Culture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999)

Erwin Panofsky, Three Essays on Style (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995)

Lois Parkinson Zamora and Monika Kaup, “Baroque, New World Baroque, Neobaroque: Categories and Concepts.” In Lois Parkinson Zamora and Monika Kaup, eds. Baroque New Worlds: Representation, Transculturation, Counterconquest (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 1–35.

Molly A Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492–1700 (Williamsburg, Virginia: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018)

Thijs Weststeijn, “Cultural Reflections on Porcelain in the Seventeenth-Century Netherlands,” in J. van Campen and T. Eliens, eds. Chinese and Japanese Porcelain for the Dutch Golden Age (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2014), pp. 213–229, 265–268.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art (New York: Dover Publications, 1950, ©1932)

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Baroque Architecture: Everything You Need to Know

By Katherine McLaughlin

For those that love a performance, perhaps no building style is more theatrical than Baroque architecture. “The origins of the word ‘Baroque’ are not entirely clear, but it is generally associated with irregularity in forms as well as opulence,” says Laura Foster, an architectural historian and professor at John Cabot University whose research focuses on Baroque architecture. Born in Italy in the late 16th century and flourishing throughout certain parts of Europe, the style was characterized by grandeur and a distinct dramatic flair. In this guide from AD, learn just how Baroque architecture came to be, discover famous examples of the style, and study what exactly makes the look different from other ornamented aesthetics.

What is Baroque architecture?

Strictly speaking, Baroque architecture refers to an opulent architectural style born in Italy in the late 16th century. “It’s a very broad term used for European architecture of the 17th and early 18th centuries,” Foster explains. As Merriam Webster defines it, the building style “is marked generally by use of complex forms, bold ornamentation, and the juxtaposition of contrasting elements often conveying a sense of drama, movement, and tension.” The architectural style is the structural manifestation of a larger movement in art and design—commonly called the Baroque period—which also included similarly elaborate and dramatic work in the visual arts and music.

Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in A Coruña, Spain

Often, Baroque architects would employ elaborate motifs and decorations in their work with an emphasis on organic, curving lines and bright colors. “The term Baroque was initially used as an epithet to describe buildings whose design strayed from the principles established during the Renaissance,” Foster adds. The style spread primarily throughout the 17th century in Europe, with particular prominence in Germany, and even made its way to colonial South America. Late Baroque work, which emerged in the mid to late 18th century, is often referred to as Rococo style—or Churrigueresque in Spain and Spanish America. This iteration of the style was even more ornamented and elaborate.

History of Baroque architecture

Unlike other architectural styles, Baroque aesthetics didn’t come to be just because of a change in cultural tastes or ideologies. Rather, the catalyst for the emergence of Baroque buildings was the ongoing tension between the Catholic Church and Protestant Reformers. “The origins of Baroque architecture are often associated with religious conditions beginning in the late 16th century,” Foster says. At this time, Protestant believers had rejected the authority of the Roman Pope and disavowed many Roman Catholic teachings. This was known as the Protestant Reformation.

Known as the Counter-Reformation, Baroque architecture was part of the Church’s campaign to entice congregants back into Catholic worship. By constructing churches to inspire awe and emotion, Catholics believed they could attract parishioners back to them. The church commissioned architects to reimagine many of the elements of Renaissance architecture—like domes and colonnades—and make them grander and more dramatic. Inside, almost all design decisions were made to entice visitors to look up, with the goal to make worshipers feel as if they were looking into heaven. Quadratura or trompe-l’oeil paintings on the ceilings or winding columns that evoked upward movement were often employed as part of this.

.jpg)

Karlskirche in Vienna

Early Baroque architecture was largely contained to Rome, later spreading to more Italian cities before making its way across other European nations. Some of the earliest completed works in the Baroque period were the Church of Gesu, in 1584, and the facade of St. Peter’s Basilica, designed in 1612. As the style took hold, it wasn’t just churches that were crafted in the aesthetic, but secular buildings too. One of the most famous examples of this—commissioned by Louis XIV of France—is the Palace of Versailles.

“The Baroque style overlapped with Neoclassicism in the 18th century, which largely replaced [Baroque architecture] by the end of the century,” Foster says of the style’s end. “Its disappearance partly had to do with religious associations made with the Baroque style as well as identification of it with monarchy and absolutism.”

Defining elements and characteristics of Baroque architecture

The Palace of Versailles in Paris

By Mona Basharat

By Carly Olson

By Annabelle Dufraigne

According to Foster, there are three main elements that define all Baroque buildings. “First, there is a sense of monumentality even when the space is actually small,” she says. This can be seen throughout many Baroque structures, though she says the façade of Francesco Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane is a particularly good example. Next, Baroque design exemplifies a desire to create embodied experiences of architectural space. “This was done by creating theatrical forms through the manipulation of the classical orders, curvature in walls and façades, and the dynamic sequencing of spaces,” she explains, citing Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale as a good example. Lastly, light plays a vital role in Baroque work. “Its use is often through reflective or glimmering surfaces, such as the extensive use of gold in interior church and palace decoration,” she says.

To better understand the style of architecture, consider the elements and characteristics of Baroque architecture. Though not exhaustive, many Baroque buildings will make use of the following:

- Vaulted cupolas

- Twirling and swiveling colonnades

- Rough stone and smooth stucco used throughout walls and doorways

- Frescoes and ornately painted ceilings

- Trompe l’oeil paintings—French for “deceives the eye”—on the ceilings and walls. This style included hyperrealistic subjects, like painted windows, which would give the viewer the perception that windows actually existed

- Use of complex form and less focus on strict rigidity or order

- Gilding on the interior and exterior

- Elaborate and highly decorative interior design

Famous Baroque architecture examples and architects

Consider the following list of notable architects and buildings from the Baroque period:

Facade of Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

Commissioned in 1634 and built between 1638 and 1646 (the façade was later added in 1677), this Roman church was designed by Francesco Borromini as a monastery for a small group of Spanish monks. Though it is constructed in a relatively small plot, it’s a prime example of the way Baroque architecture emphasizes the feeling of monumentality. The curved, undulating façade was also frequently referenced in later Baroque work.

The main nave and altar within Jesuit Church Il Gesù

One of the most cited examples of Baroque architecture, Jesuit Church Il Gesù is the mother church for Jesuits. Featuring a single aisle, side chapels, and a large dome over the nave and the transepts, the layout became a standard for many Baroque churches. The fresco on the nave, The Triumph of the Name of Jesus by Giovanni Battista Gaulli, is considered one of the most pristine examples of Baroque art.

The cupola of Chiesa di Sant’Andrea al Quirinale

Commissioned by Cardinal Camillo Francesco Maria Pamphili, Church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale was the third Jesuit church in Rome. Gian Lorenzo Bernini was said to have been incredibly proud of the structure and considered it one of this best works. The heavily gilded dome is representative of the ways Baroque churches encouraged visitors to look upwards.

The Quire inside St. Paul’s Cathedral

As the seat of the Bishop of London, St. Paul’s Cathedral is one of the most celebrated Baroque buildings in England. It’s considered a more restrained version of the Baroque style, and the large dome of the cathedral remains one of the most recognizable parts of of the London skyline.

The Hall of Mirrors inside the Palace of Versailles

Executed in the French Baroque style, the Palace of Versailles is often cited as one of the most notable royal residences in the world. Commissioned by Louis XIV, every element of the structure is designed to glorify the king. The highly extravagant Hall of Mirrors is likely the most famous room in the building.

What is the importance of Baroque architecture?

Like any aesthetic period, understanding Baroque architecture helps tell the human story. Not only does it serve as a lasting reminder of an important moment in history, but studying its impact explains the desires and ideals of Europeans at that time. It was also one of the first architectural styles to spread globally and a prime example of the way architecture is used to convey cultural messages.

Additionally, the Baroque period has long represented a creative peak for Western civilization. As modernist architect Harry Seidler explained in a lecture at University of New South Wales in 1980 on the links between Baroque and modern architecture, the Baroque style was one of the last great examples of a truly new aesthetic. “The Baroque has been called the last great creative and innovative period before our own; there have only been revival periods in between us,” he said. “The fact remains that both eras [modernism and baroque] were born of fresh thought.”

More Great Stories From AD

The Story Behind the Many Ghost Towns of Abandoned Mansions Across China

Inside Sofía Vergara’s Personal LA Paradise

Inside Emily Blunt and John Krasinski’s Homes Through the Years

Take an Exclusive First Look at Shea McGee’s Remodel of Her Own Home

Notorious Mobsters at Home: 13 Photos of Domestic Mob Life

Shop Amy Astley’s Picks of the Season

Modular Homes: Everything You Need to Know About Going Prefab

Shop Best of Living—Must-Have Picks for the Living Room

Beautiful Pantry Inspiration We’re Bookmarking From AD PRO Directory Designers

Not a subscriber? Join AD for print and digital access now.

Browse the AD PRO Directory to find an AD -approved design expert for your next project.

By Perri Ormont Blumberg

Baroque Art – Exploring the Exuberance of Baroque Period Art

The Baroque period emerged after the Renaissance and Mannerism periods and brought with it new perspectives about life, art, religion, and culture. The Baroque style moved away from the severe elements depicted by the Protestant style, while the Catholic Church supported the development of Baroque with its origins in Rome, Italy, and many European countries. In this article, we unpack the decorative and fanciful art period encompassed by Baroque art, including its most famous artists and the origins of the movement.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 The Reformation: The Catholic Church and Protestants

- 1.2 The Protestants Versus Counter-Reformation Groups

- 1.3 A Flawed Pearl: Definition of Baroque

- 2.1.1 Chiaroscuro

- 2.1.2 Tenebrism

- 2.1.3 Quadro Riportato

- 2.1.4 Illusionism: Trompe l’Oeil and Quadratura

- 3.1 Annibale Carracci (1560 – 1609)

- 3.2 Caravaggio (1571 – 1610)

- 3.3 Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1656)

- 4.1 Giacomo Della Porta (1532 – 1602)

- 5.1 Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680)

- 6.1 Flemish Baroque Artists

- 6.2 French Baroque Artists

- 6.3 Spanish Baroque Artists

- 6.4 Dutch Baroque Artists

- 7 From Dark to Light: Baroque and Rococo

- 8.1 What Is Baroque Art?

- 8.2 What Are the Characteristics of Baroque Art?

- 8.3 When Was the Baroque Period?

Historical Foundations of the Baroque Period

When was the Baroque period? The Baroque period began during the the late 1500s and lasted until the early 1700s. The movement’s reach was considered to be incredibly wide and varied throughout many European countries. The Baroque style was founded on the principles of extravagance, ornateness, and intricately decorated details that were portrayed in a range of traditional mediums such as paintings, architecture, sculpture, literature, and music. It was regarded as a period of revival across art and culture, with deep roots in the religious structures and powers of Western Europe at the time. These religious structures included the Catholic Church, which is presently referred to as the Roman Catholic Church.

Baroque art, of any kind, was inseparably linked to the Catholic Church. In fact, the Church had a great influence over shaping the conventions around what art should look like to have a desired effect on the people. Baroque art was made to inspire grandeur and awe in the people who experienced it and became a wholly new sensory religious experience.

The Catholic Church supported the Baroque style because it needed a new and enlivened approach to inspire and uplift the common people, as well as to connect them with the Church and its majestic nature.

After the turmoil of war and conflicts from the Reformation, Baroque art offered a refreshing resurgence for the Church and its community. The driving forces behind this can be considered propagandist, as it used the modes of visual representation and communication via painting, architecture, sculpture to maintain the credibility and authority of the Catholic Church.

To better understand the advancements that Baroque art brought to art and culture in the 17th century, we need to look at the historical foundations underpinning this complex movement.

The Reformation: The Catholic Church and Protestants

The Baroque period developed from considerable political and religious upheaval in Europe, such as the Reformation between the Protestants and the Catholic Church during the 1500s. Although the Reformation may have started with many other religious figures before Martin Luther (a German monk, priest, and theologian), many scholarly sources point to him as the catalyst of the Reformation, which set these events in motion.