Pursuing Truth: A Guide to Critical Thinking

Chapter 4 propositional logic.

Categorical logic is a great way to analyze arguments, but only certain kinds of arguments. It is limited to arguments that have only two premises and the four kinds of categorical sentences. This means that certain common arguments that are obviously valid will not even be well-formed arguments in categorical logic. Here is an example:

- I will either go out for dinner tonight or go out for breakfast tomorrow.

- I won’t go out for dinner tonight.

- I will go out for breakfast tomorrow.

None of these sentences fit any of the four categorical schemes. So, we need a new logic, called propositional logic. The good news is that it is fairly simple.

4.1 Simple and Complex Sentences

The fundamental logical unit in categorical logic was a category, or class of things. The fundamental logical unit in propositional logic is a statement, or proposition 5 Simple statements are statements that contain no other statement as a part. Here are some examples:

- Oklahoma Baptist University is in Shawnee, Oklahoma.

- Barack Obama was succeeded as President of the US by Donald Trump.

- It is 33 degrees outside.

Simple sentences are symbolized by uppercase letters. Just pick a letter that makes sense, given the sentence to be symbolized, that way you can more easily remember which letter means which sentence.

Complex sentences have at least one sentence as a component. There are five types in propositional logic:

- Conjunctions

- Disjunctions

- Conditionals

- Biconditionals

4.1.1 Negations

Negations are “not” sentences. They assert that something is not the case. For example, the negation of the simple sentence “Oklahoma Baptist University is in Shawnee, Oklahoma” is “Oklahoma Baptist University is not in Shawnee, Oklahoma.” In general, a simple way to form a negation is to just place the phrase “It is not the case that” before the sentence to be negated.

A negation is symbolized by placing this symbol ‘ \(\neg\) ’ before the sentence-letter. The symbol looks like a dash with a little tail on its right side. If \(\textrm{D}\) = ‘It is 33 degrees outside,’ then \(\neg \textrm{D}\) = ‘It is not 33 degrees outside.’ The negation symbol is used to translate these English phrases:

- it is not the case that

- it is not true that

- it is false that

A negation is true whenever the negated sentence is false. If it is true that it is not 33 degrees outside, then it must be false that it is 33 degrees outside. if it is false that Tulsa is the capital of Oklahoma, then it is true that Tulsa is not the capital of Oklahoma.

When translating, try to keep the simple sentences positive in meaning. Note the warning on page 24, about the example of affirming and denying. Denying is not simply the negation of affirming.

4.2 Conjunction

Negations are “and” sentences. They put two sentences, called conjuncts, together and claim that they are both true. We’ll use the ampersand (&) to signify a negation. Other common symbols are a dot and an upside down wedge. The English words that are translated with the ampersand include:

- nevertheless

For example, we would translate the sentence ‘It is raining today and my sunroof is open’ as ‘ \(\textrm{R} \& \textrm{O}\) .’

4.3 Disjunction

A disjunction is an “or” sentence. It claims that at least one of two sentences, called disjuncts, is true. For example, if I say that either I will go to the movies this weekend or I will stay home and grade critical thinking homework, then I have told the truth provided that I do one or both of those things. If I do neither, though, then my claim was false.

We use this symbol, called a “vel,” for disjunctions: \(\vee\) . The vel is used to translate - or - eitheror - unless

4.4 Conditional

The conditional is a common type of sentence. It claims that something is true, if something else is also. Examples of conditionals are

- “If Sarah makes an A on the final, then she will get an A for the course.”

- “Your car will last many years, provided you perform the required maintenance.”

- “You can light that match only if it is not wet.”

We can translate those sentences with an arrow like this:

- \(F \rightarrow C\)

- \(M \rightarrow L\)

- \(L \rightarrow \neg W\)

The arrow translates many English words and phrases, including

- provided that

- is a sufficient condition for

- is a necessary condition for

- on the condition that

One big difference between conditionals and other sentences, like conjunctions and disjunctions, is that order matters. Notice that there is no logical difference between the following two sentences:

- Albany is the capital of New York and Austin is the capital of Texas.

- Austin is the capital of Texas and Albany is the capital of New York.

They essentially assert exactly the same thing, that both of those conjuncts are true. So, changing order of the conjuncts or disjuncts does not change the meaning of the sentence, and if meaning doesn’t change, then true value doesn’t change.

That’s not true of conditionals. Note the difference between these two sentences:

- If you drew a diamond, then you drew a red card.

- If you drew a red card, then you drew a diamond.

The first sentence must be true. if you drew a diamond, then that guarantees that it’s a red card. The second sentence, though, could be false. Your drawing a red card doesn’t guarantee that you drew a diamond, you could have drawn a heart instead. So, we need to be able to specify which sentence goes before the arrow and which sentence goes after. The sentence before the arrow is called the antecedent, and the sentence after the arrow is called the consequent.

Look at those three examples again:

The antecedent for the first sentence is “Sarah makes an A on the final.” The consequent is “She will get an A for the course.” Note that the if and the then are not parts of the antecedent and consequent.

In the second sentence, the antecdent is “You perform the required maintenance.” The consequent is “Your car will last many years.” This tells us that the antecedent won’t always come first in the English sentence.

The third sentence is tricky. The antecedent is “You can light that match.” Why? The explanation involves something called necessary and sufficient conditions.

4.4.1 Necessary and Sufficient Conditions

A sufficient condition is something that is enough to guarantee the truth of something else. For example, getting a 95 on an exam is sufficient for making an A, assuming that exam is worth 100 points. A necessary condition is something that must be true in order for something else to be true. Making a 95 on an exam is not necessary for making an A—a 94 would have still been an A. Taking the exam is necessary for making an A, though. You can’t make an A if you don’t take the exam, or, in other words, you can make an a only if you enroll in the course.

Here are some important rules to keep in mind:

- ‘If’ introduces antecedents, but Only if introduces consequents.

- If A is a sufficient condition for B, then \(A \rightarrow B\) .

- If A is a necessary condition for B, then \(B \rightarrow A\) .

4.5 Biconditional

We won’t spend much time on biconditionals. There are times when something is both a necessary and a sufficient condition for something else. For example, making at least a 90 and getting an A (assuming a standard scale, no curve, and no rounding up). If you make at least a 90, then you will get an A. If you got an A, then you made at least a 90. We can use a double arrow to translate a biconditional, like this:

- \(N \rightarrow A\)

For biconditionals, as for conjunctions and disjunctions, order doesn’t matter.

Here are some English phrases that signify biconditionals:

- it and only if

- when and only when

- just in case

- is a necessary and sufficient condition for

4.6 Translations

Propositional logic is language. Like other languages, it has a syntax and a semantics. The syntax of a language includes the basic symbols of the language plus rules for putting together proper statements in the language. To use propositional logic, we need to know how to translate English sentences into the language of propositional logic. We start with our sentence letters, which represent simple English sentences. Let’s use three borrowed from an elementary school reader:

We then build complex sentences using the sentence letters and our five logical operators, like this:

We can make even more complex sentences, but we will soon run into a problem. Consider this example:

\[ T \mathbin{\&} J \rightarrow S\]

We don’t know this means. It could be either one of the following:

- Tom hit the ball, and if Jane caught the ball, then Spot chased it.

- If Tom hit the ball and Jane caught it, then Spot chased it.

The first sentence is a conjunction, \(T\) is the first conjunct and \(M \rightarrow S\) is the second conjunct. The second sentence, though, is a conditional, \(T \mathbin{\&}M\) is the antecdent, and \(S\) is the consequent. Our two interpretations are not equivalent, so we need a way to clear up the ambiguity. We can do this with parentheses. Our first sentence becomes:

\[ T \mathbin{\&} (J \rightarrow S) \]

The second sentence is:

\[ (T \mathbin{\&} J) \rightarrow S\]

If we need higher level parentheses, we can use brackets and braces. For instance, this is a perfectly good formula in propositional logic:

\[ [(P \mathbin{\&} Q) \vee R] \rightarrow \{[(\neg P \leftrightarrow Q) \mathbin{\&} S] \vee \neg P\} \] 6

Every sentence in propositional logic is one of six types:

- Conjunction

- Disjunction

- Conditional

- Biconditional

What type of sentence it is will be determined by its main logical operator. Sentences can have several logical operators, but they will always have one, and only one, main operator. Here are some general rules for finding the main operator in a symbolized formula of propositional logic:

- If a sentence has only one logical operator, then that is the main operator.

- If a sentence has more than one logical operator, then the main operator is the one outside the parentheses.

- If a sentence has two logical operators outside the parentheses, then the main operator is not the negation.

Here are some examples:

Informally, we use ‘proposition’ and ‘statement’ interchangeably. Strictly speaking, the proposition is the content, or meaning, that the statement expresses. When different sentences in different languages mean the same thing, it is because they express the same proposition. ↩︎

It may be a good formula in propositional logic, but that doesn’t mean it would be a good English sentence. ↩︎

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.5 Critical Thinking and Research Applications

Learning objectives.

- Analyze source materials to determine how they support or refute the working thesis.

- Identify connections between source materials and eliminate redundant or irrelevant source materials.

- Identify instances when it is appropriate to use human sources, such as interviews or eyewitness testimony.

- Select information from sources to begin answering the research questions.

- Determine an appropriate organizational structure for the research paper that uses critical analysis to connect the writer’s ideas and information taken from sources.

At this point in your project, you are preparing to move from the research phase to the writing phase. You have gathered much of the information you will use, and soon you will be ready to begin writing your draft. This section helps you transition smoothly from one phase to the next.

Beginning writers sometimes attempt to transform a pile of note cards into a formal research paper without any intermediary step. This approach presents problems. The writer’s original question and thesis may be buried in a flood of disconnected details taken from research sources. The first draft may present redundant or contradictory information. Worst of all, the writer’s ideas and voice may be lost.

An effective research paper focuses on the writer’s ideas—from the question that sparked the research process to how the writer answers that question based on the research findings. Before beginning a draft, or even an outline, good writers pause and reflect. They ask themselves questions such as the following:

- How has my thinking changed based on my research? What have I learned?

- Was my working thesis on target? Do I need to rework my thesis based on what I have learned?

- How does the information in my sources mesh with my research questions and help me answer those questions? Have any additional important questions or subtopics come up that I will need to address in my paper?

- How do my sources complement each other? What ideas or facts recur in multiple sources?

- Where do my sources disagree with each other, and why?

In this section, you will reflect on your research and review the information you have gathered. You will determine what you now think about your topic. You will synthesize , or put together, different pieces of information that help you answer your research questions. Finally, you will determine the organizational structure that works best for your paper and begin planning your outline.

Review the research questions and working thesis you developed in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” . Set a timer for ten minutes and write about your topic, using your questions and thesis to guide your writing. Complete this exercise without looking over your notes or sources. Base your writing on the overall impressions and concepts you have absorbed while conducting research. If additional, related questions come to mind, jot them down.

Selecting Useful Information

At this point in the research process, you have gathered information from a wide variety of sources. Now it is time to think about how you will use this information as a writer.

When you conduct research, you keep an open mind and seek out many promising sources. You take notes on any information that looks like it might help you answer your research questions. Often, new ideas and terms come up in your reading, and these, too, find their way into your notes. You may record facts or quotations that catch your attention even if they did not seem immediately relevant to your research question. By now, you have probably amassed an impressively detailed collection of notes.

You will not use all of your notes in your paper.

Good researchers are thorough. They look at multiple perspectives, facts, and ideas related to their topic, and they gather a great deal of information. Effective writers, however, are selective. They determine which information is most relevant and appropriate for their purpose. They include details that develop or explain their ideas—and they leave out details that do not. The writer, not the pile of notes, is the controlling force. The writer shapes the content of the research paper.

While working through Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.4 “Strategies for Gathering Reliable Information” , you used strategies to filter out unreliable or irrelevant sources and details. Now you will apply your critical-thinking skills to the information you recorded—analyzing how it is relevant, determining how it meshes with your ideas, and finding how it forms connections and patterns.

Writing at Work

When you create workplace documents based on research, selectivity remains important. A project team may spend months conducting market surveys to prepare for rolling out a new product, but few managers have time to read the research in its entirety. Most employees want the research distilled into a few well-supported points. Focused, concise writing is highly valued in the workplace.

Identify Information That Supports Your Thesis

In Note 11.81 “Exercise 1” , you revisited your research questions and working thesis. The process of writing informally helped you see how you might begin to pull together what you have learned from your research. Do not feel anxious, however, if you still have trouble seeing the big picture. Systematically looking through your notes will help you.

Begin by identifying the notes that clearly support your thesis. Mark or group these, either physically or using the cut-and-paste function in your word-processing program. As you identify the crucial details that support your thesis, make sure you analyze them critically. Ask the following questions to focus your thinking:

- Is this detail from a reliable, high-quality source? Is it appropriate for me to cite this source in an academic paper? The bulk of the support for your thesis should come from reliable, reputable sources. If most of the details that support your thesis are from less-reliable sources, you may need to do additional research or modify your thesis.

- Is the link between this information and my thesis obvious—or will I need to explain it to my readers? Remember, you have spent more time thinking and reading about this topic than your audience. Some connections might be obvious to both you and your readers. More often, however, you will need to provide the analysis or explanation that shows how the information supports your thesis. As you read through your notes, jot down ideas you have for making those connections clear.

- What personal biases or experiences might affect the way I interpret this information? No researcher is 100 percent objective. We all have personal opinions and experiences that influence our reactions to what we read and learn. Good researchers are aware of this human tendency. They keep an open mind when they read opinions or facts that contradict their beliefs.

It can be tempting to ignore information that does not support your thesis or that contradicts it outright. However, such information is important. At the very least, it gives you a sense of what has been written about the issue. More importantly, it can help you question and refine your own thinking so that writing your research paper is a true learning process.

Find Connections between Your Sources

As you find connections between your ideas and information in your sources, also look for information that connects your sources. Do most sources seem to agree on a particular idea? Are some facts mentioned repeatedly in many different sources? What key terms or major concepts come up in most of your sources regardless of whether the sources agree on the finer points? Identifying these connections will help you identify important ideas to discuss in your paper.

Look for subtler ways your sources complement one another, too. Does one author refer to another’s book or article? How do sources that are more recent build upon the ideas developed in earlier sources?

Be aware of any redundancies in your sources. If you have amassed solid support from a reputable source, such as a scholarly journal, there is no need to cite the same facts from an online encyclopedia article that is many steps removed from any primary research. If a given source adds nothing new to your discussion and you can cite a stronger source for the same information, use the stronger source.

Determine how you will address any contradictions found among different sources. For instance, if one source cites a startling fact that you cannot confirm anywhere else, it is safe to dismiss the information as unreliable. However, if you find significant disagreements among reliable sources, you will need to review them and evaluate each source. Which source presents a sounder argument or more solid evidence? It is up to you to determine which source is the most credible and why.

Finally, do not ignore any information simply because it does not support your thesis. Carefully consider how that information fits into the big picture of your research. You may decide that the source is unreliable or the information is not relevant, or you may decide that it is an important point you need to bring up. What matters is that you give it careful consideration.

As Jorge reviewed his research, he realized that some of the information was not especially useful for his purpose. His notes included several statements about the relationship between soft drinks that are high in sugar and childhood obesity—a subtopic that was too far outside of the main focus of the paper. Jorge decided to cut this material.

Reevaluate Your Working Thesis

A careful analysis of your notes will help you reevaluate your working thesis and determine whether you need to revise it. Remember that your working thesis was the starting point—not necessarily the end point—of your research. You should revise your working thesis if your ideas changed based on what you read. Even if your sources generally confirmed your preliminary thinking on the topic, it is still a good idea to tweak the wording of your thesis to incorporate the specific details you learned from research.

Jorge realized that his working thesis oversimplified the issues. He still believed that the media was exaggerating the benefits of low-carb diets. However, his research led him to conclude that these diets did have some advantages. Read Jorge’s revised thesis.

Although following a low-carbohydrate diet can benefit some people, these diets are not necessarily the best option for everyone who wants to lose weight or improve their health.

Synthesizing and Organizing Information

By now your thinking on your topic is taking shape. You have a sense of what major ideas to address in your paper, what points you can easily support, and what questions or subtopics might need a little more thought. In short, you have begun the process of synthesizing information—that is, of putting the pieces together into a coherent whole.

It is normal to find this part of the process a little difficult. Some questions or concepts may still be unclear to you. You may not yet know how you will tie all of your research together. Synthesizing information is a complex, demanding mental task, and even experienced researchers struggle with it at times. A little uncertainty is often a good sign! It means you are challenging yourself to work thoughtfully with your topic instead of simply restating the same information.

Use Your Research Questions to Synthesize Information

You have already considered how your notes fit with your working thesis. Now, take your synthesis a step further. Analyze how your notes relate to your major research question and the subquestions you identified in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” . Organize your notes with headings that correspond to those questions. As you proceed, you might identify some important subtopics that were not part of your original plan, or you might decide that some questions are not relevant to your paper.

Categorize information carefully and continue to think critically about the material. Ask yourself whether the sources are reliable and whether the connections between ideas are clear.

Remember, your ideas and conclusions will shape the paper. They are the glue that holds the rest of the content together. As you work, begin jotting down the big ideas you will use to connect the dots for your reader. (If you are not sure where to begin, try answering your major research question and subquestions. Add and answer new questions as appropriate.) You might record these big ideas on sticky notes or type and highlight them within an electronic document.

Jorge looked back on the list of research questions that he had written down earlier. He changed a few to match his new thesis, and he began a rough outline for his paper.

Review your research questions and working thesis again. This time, keep them nearby as you review your research notes.

- Identify information that supports your working thesis.

- Identify details that call your thesis into question. Determine whether you need to modify your thesis.

- Use your research questions to identify key ideas in your paper. Begin categorizing your notes according to which topics are addressed. (You may find yourself adding important topics or deleting unimportant ones as you proceed.)

- Write out your revised thesis and at least two or three big ideas.

You may be wondering how your ideas are supposed to shape the paper, especially since you are writing a research paper based on your research. Integrating your ideas and your information from research is a complex process, and sometimes it can be difficult to separate the two.

Some paragraphs in your paper will consist mostly of details from your research. That is fine, as long as you explain what those details mean or how they are linked. You should also include sentences and transitions that show the relationship between different facts from your research by grouping related ideas or pointing out connections or contrasts. The result is that you are not simply presenting information; you are synthesizing, analyzing, and interpreting it.

Plan How to Organize Your Paper

The final step to complete before beginning your draft is to choose an organizational structure. For some assignments, this may be determined by the instructor’s requirements. For instance, if you are asked to explore the impact of a new communications device, a cause-and-effect structure is obviously appropriate. In other cases, you will need to determine the structure based on what suits your topic and purpose. For more information about the structures used in writing, see Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” .

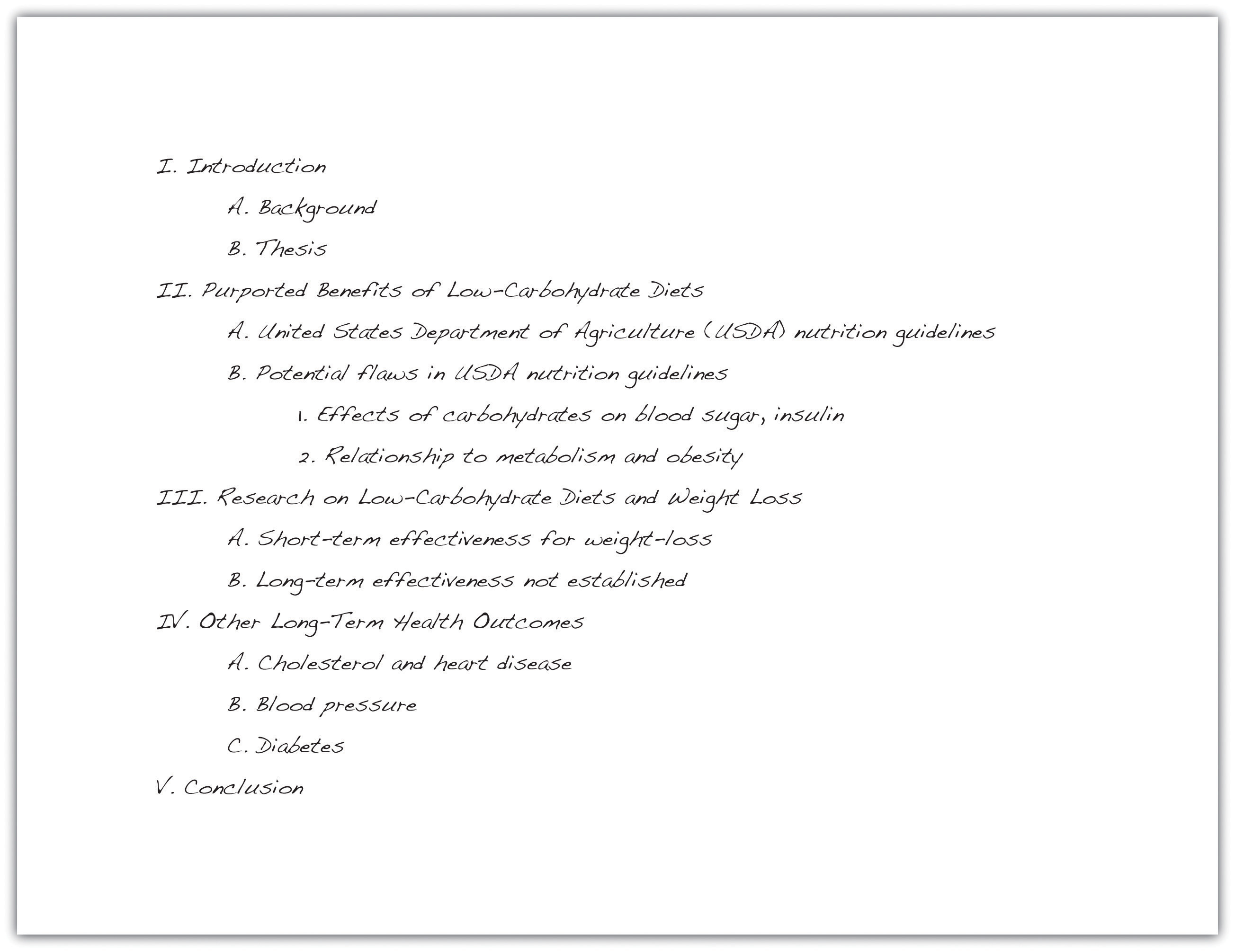

The purpose of Jorge’s paper was primarily to persuade. With that in mind, he planned the following outline.

Review the organizational structures discussed in this section and Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” . Working with the notes you organized earlier, follow these steps to begin planning how to organize your paper.

- Create an outline that includes your thesis, major subtopics, and supporting points.

- The major headings in your outline will become sections or paragraphs in your paper. Remember that your ideas should form the backbone of the paper. For each major section of your outline, write out a topic sentence stating the main point you will make in that section.

- As you complete step 2, you may find that some points are too complex to explain in a sentence. Consider whether any major sections of your outline need to be broken up and jot down additional topic sentences as needed.

- Review your notes and determine how the different pieces of information fit into your outline as supporting points.

Collaboration

Please share the outline you created with a classmate. Examine your classmate’s outline and see if any questions come to mind or if you see any area that would benefit from an additional point or clarification. Return the outlines to each other and compare observations.

The structures described in this section and Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” can also help you organize information in different types of workplace documents. For instance, medical incident reports and police reports follow a chronological structure. If the company must choose between two vendors to provide a service, you might write an e-mail to your supervisor comparing and contrasting the choices. Understanding when and how to use each organizational structure can help you write workplace documents efficiently and effectively.

Key Takeaways

- An effective research paper focuses on presenting the writer’s ideas using information from research as support.

- Effective writers spend time reviewing, synthesizing, and organizing their research notes before they begin drafting a research paper.

- It is important for writers to revisit their research questions and working thesis as they transition from the research phase to the writing phrase of a project. Usually, the working thesis will need at least minor adjustments.

- To organize a research paper, writers choose a structure that is appropriate for the topic and purpose. Longer papers may make use of more than one structure.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences

- Gregory J. Privitera - St. Bonaventure University

- Description

Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences, Third Edition employs a problem-focused approach to present a clear and comprehensive introduction to research methods. Award-winning teacher, author, and advisor Gregory J. Privitera fully integrates the research methods decision tree into the text to help students choose the most appropriate methodology for the research question they are seeking to answer. Speaking to readers directly, Privitera empowers students to view research methods as something they can understand and apply in their daily lives.

INSTRUCTORS: Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences, Third Edition is available with a complete teaching and learning package! Contact your rep to request a demo and answer any questions.

- SAGE coursepacks FREE! SAGE coursepacks makes it easy to import our quality instructor and student resource content into your school’s learning management system (LMS). Intuitive and simple to use, SAGE coursepacks allows you to customize course content to meet your students’ needs. Learn more >>

- SAGE edge FREE! SAGE edge offers students a robust online environment with an impressive array of learning resources. Learn more >>

- Student Study Guide Bundle with the Student Study Guide With IBM® SPSS® Workbook for Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences, Third Edition for only $5 more (Bundle ISBN: 978-1-5443-7100-9). Learn more >>

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

edge.sagepub.com/priviteramethods3e

SAGE edge for students enhances learning, it’s easy to use, and offers :

- an open-access site that makes it easy for students to maximize their study time, anywhere, anytime;

- SPSS ® in Focus Screencast videos for SPSS in Focus sections from the text that show step-by-step how to use SPSS ® ;

- eF lashcards that strengthen understanding of key terms and concepts;

- chapter q uizzes that allow students to practice and assess how much they’ve learned and where they need to focus their attention;

- exclusive access to influential SAGE journal content that ties important research and scholarship to chapter concepts to strengthen learning; and

- exercises and multimedia links that facilitate student use of Internet resources, further exploration of topics, and responses to critical thinking questions.

Instructors : SAGE coursepacks and SAGE edge online resources are included FREE with this text. For a brief demo, contact your sales representative today.

SAGE coursepacks for instructors makes it easy to import our quality content into your school’s learning management system (LMS)*. Intuitive and simple to use, it allows you to

- required access codes

- learning a new system

Say YES to…

- using only the content you want and need

- high-quality assessment and multimedia exercises

*For use in: Blackboard, Canvas, Brightspace by Desire2Learn (D2L), and Moodle

Don’t use an LMS platform? No problem, you can still access many of the online resources for your text via SAGE edge.

With SAGE coursepacks, you get:

- quality textbook content delivered directly into your LMS ;

- an intuitive, simple format that makes it easy to integrate the material into your course with minimal effort;

- assessment tools that foster review, practice, and critical thinking, including:

o diagnostic chapter pre-tests and post-tests that identify opportunities for improvement, track student progress, and ensure mastery of key learning objectives

o test banks built on Bloom’s Taxonomy that provide a diverse range of test items with ExamView test generation

o activity and quiz options that allow you to choose only the assignments and tests you want

o instructions on how to use and integrate the comprehensive assessments and resources provided;

- chapter-specific discussion questions to help launch engaging classroom interaction while reinforcing important content;

- exclusive SAGE journal and reference content , built into course materials and assessment tools, that ties influential research and scholarship to chapter concepts;

- editable, chapter-specific PowerPoint ® slides that offer flexibility when creating multimedia lectures so you don’t have to start from scratch;

- sample course syllabi with suggested models for structuring your course that give you options to customize your course to your exact needs;

- all tables and figures from the textbook;

- an instructor’s manual with chapter outlines, lecture suggestions, and more

- SPSS in Focus Screencasts that accompany each SPSS in Focus section from the book and provide step-by-step instructions

- end-of-chapter questions and answer keys

Very comprehensive and easy to understand

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- Testing the Assumptions of Parametric Testing features balance the coverage of this final analysis step in quantitative research by: making students aware of the assumptions; connecting readers to where in the book they can learn about nonparametric alternatives to this testing; and providing students with a more balanced perspective for choosing appropriate statistical analyses to analyze quantitative data.

- Additional and updated examples clarify distinguishing between basic and applied research, types of validity and reliability, and more.

- Hypothesis methodology linked to current examples help students realize the value and real-world application of research design in the behavioral sciences, and connects them to examples in research that they can relate to their own experiences and interests.

- Content reflective of SPSS ® v.25 incorporates new selection options required to analyze data in chapters and in Appendix B.

- An updated study guide helps students practice their skills with SPSS ® exercises.

- Revised figures, tables, and writing improve readability of the material.

- Over 130 new references reflect the latest scholarship and perspectives and replace relatively outdated references.

KEY FEATURES:

- A problem-focused organization of five main sections that each build upon the last give students a full picture of the scientific process.

- Ethics in Focus sections integrated throughout review important ethical issues related to the topics in each chapter.

- Coverage of three broad categories of research design (nonexperimental, quasi-experimental, and experimental) focuses on understanding how, when, and why research designs are used, and the types of questions each design can and cannot answer.

- A guide at the front of the book, How to Use SPSS ® With This Book , provides students with an easy-to-follow, classroom-tested overview of how SPSS ® is set up, how to read the Data View and Variable View screens, and how to use the SPSS ® in Focus sections in the book.

- SPSS ® in Focus sections provide step-by-step instruction using practical research examples for how the data measured using various research designs taught in each chapter can be analyzed using SPSS ® .

- Learning Objectives organize student learning outcomes at the beginning of each chapter and are answered in chapter-concluding summaries.

- Learning Checks with answer keys allow students to review what they learn as they learn it and actually confirm their understanding.

- Making Sense sections break down the most difficult concepts to ease student stress and make research methods more approachable.

- APA appendices support learning of APA style with a guide to grammar, punctuation, and spelling; a full sample APA-style manuscript from a study published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal; instructions for creating posters using PowerPoint ® , and more.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1: Introduction to Scientific Thinking

Chapter 2: Generating Testable Ideas

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

Shipped Options:

BUNDLE: Privitera: Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences 3e (Hardcover) + Privitera: Student Study Guide With IBM® SPSS® Workbook for Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences 3e (Paperback)

Introduction

Chapter outline.

What comes to mind when you think about therapy for mental health issues? You might picture someone lying on a couch talking about his childhood while the therapist sits and takes notes, à la Sigmund Freud. But can you envision a therapy session in which someone is wearing virtual reality headgear to conquer a fear of snakes?

In this chapter, you will see that approaches to therapy include both psychological and biological interventions, all with the goal of alleviating distress. Because psychological problems can originate from various sources—biology, genetics, childhood experiences, conditioning, and sociocultural influences—psychologists have developed many different therapeutic techniques and approaches. The Ocean Therapy program shown in Figure 16.1 uses multiple approaches to support the mental health of veterans in the group.

There are many misconceptions and assumptions about therapy and treatment. In the same way that mental health and psychological disorders are often misunderstood and may be discounted, seeking help for problems can be a difficult and scary time for people. There is no one method that works for everyone, and those seeking help are displaying strength and courage in their decision to address a highly stigmatized and challenging issue. The goal of treatment is not to change whom a person is, but to address symptoms and/or underlying conditions.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/16-introduction

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Describe the steps of critical thinking, Define evidence based knowledge, Truth seeking and more. ... Assignment 16.1 Review Questions. 40 terms. Michael-Tan13. Preview. chapter 15 Electronic claim. 24 terms. edie0168.

Chapter 15 (Critical Thinking) Term. 1 / 50. Critical Thinking Involves. Click the card to flip 👆. Definition. 1 / 50. Open-mindedness, continual inquiry and perseverance, combined with willingness to look at each unique patient situation and determine which identified assumptions are true and relevant. Click the card to flip 👆.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like While assessing a patient, the nurse observes that the patient's intravenous (IV) line is not infusing at the ordered rate. The nurse assesses the patient for pain at the IV site, checks the flow regulator on the tubing, looks to see if the patient is lying on the tubing, checks the point of connection between the tubing and the ...

ASSIGNMENT 15.2 CRITICAL THINKING FOR MEDICAL AND NONMEDICAL CODE SETS FOR 837P ELECTRONIC CLAIMS SUBMISSION Performance Objective Task: Decide whether keyed medical and nonmedical data elements are required, situational, or not used when electronically submitting the 837P health care claim. Conditions: List of keyed data elements (Table 15.5 ...

notes chapter 15 critical thinking and clinical judgment clinical judgment model thinking critically and making sound decisions fig 15.1 pg 210. uses nursing. Skip to document. University; ... Week 2 Assignment Musculoskeletal and Integumentary Systems. health assessment 100% (4) 17.

Chapter Outline. 15.1 What Are Psychological Disorders? On Monday, September 16, 2013, a gunman killed 12 people as the workday began at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, DC. Aaron Alexis, 34, had a troubled history: he thought that he was being controlled by radio waves.

Chapter 4. Propositional Logic. Categorical logic is a great way to analyze arguments, but only certain kinds of arguments. It is limited to arguments that have only two premises and the four kinds of categorical sentences. This means that certain common arguments that are obviously valid will not even be well-formed arguments in categorical logic.

As you approach your writing project, it is important to practice the habit of thinking critically. Critical thinking can be defined as "self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking" (Paul & Elder, 2007). It is the difference between watching television in a daze versus analyzing a movie with attention to ...

Select information from sources to begin answering the research questions. Determine an appropriate organizational structure for the research paper that uses critical analysis to connect the writer's ideas and information taken from sources. At this point in your project, you are preparing to move from the research phase to the writing phase.

Unformatted text preview: ASSIGNMENT 15.2 CRITICAL THINKING FOR MEDICAL AND NONMEDICAL CODE SETS FOR 837P ELECTRONIC CLAIMS SUBMISSION Performance Objective Task: Decide whether keyed medical and nonmedical data elements are required, situational, or not used whe electronically submitting the 837P health care claim. Conditions: List of keyed data elements (Table 15.5 in Textbook) and pen or ...

critical thinking is acquired through what three ways, and it is not learned in a short period of time. 1. experience. 2. commitment. 3. active curiosity. An RN relies on _____ and _____ when deciding if a patient is having complications that call for notification of a health care provider or if a teaching plan for a patient is ineffective and ...

Get hands-on practice in medical insurance billing and coding! Corresponding to the chapters in Fordney's Medical Insurance and Billing, 16th Edition, this workbook provides realistic exercises that help you apply concepts and develop the critical thinking skills needed by insurance billing specialists.Review questions reinforce your understanding of your role and responsibilities, and ...

Introduction; 2.1 Overview of Managerial Decision-Making; 2.2 How the Brain Processes Information to Make Decisions: Reflective and Reactive Systems; 2.3 Programmed and Nonprogrammed Decisions; 2.4 Barriers to Effective Decision-Making; 2.5 Improving the Quality of Decision-Making; 2.6 Group Decision-Making; Key Terms; Summary of Learning Outcomes; Chapter Review Questions

SSIGNMENT 15.2 CRITICAL THINKING FOR MEDICAL AND NONMEDICAL CODE SETS FOR 837P LECTRONIC CLAIMS SUBMISSION erformance Objective Decide whether keyed medical and nonmedical data elements are required, situational, os no ask: electronically submitting the 837P health care claim. onditions: List of keyed data elements (Table 15.5 in Textbook) and pen or pencil. tandards: Time: minutes Accuracy ...

ASSIGNMENT 15.2 CRITICAL THINKING FOR MEDICAL AND NONMEDICAL CODE SETS FOR 837P ELECTRONIC CLAIMS SUBMISSION Performance Objective Task: Decide whether keyed medical and nonmedical data elements are required, situational, or not used when electronically submitting the 837P health care claim. Conditions: List of keyed data elements (Table 15.5 in Textbook) and pen or pencil.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Exchange of data in a standardized format through computer systems is a technology known as, The act of converting computerized data into a code so that unauthorized users are unable to read it is a security system known, Payment to the provider of service of an electronically submitted insurance claim may be received in ...

Chapter 15 15.1 Review Questions 15.2 Critical Thinking 15.8 Define Patient Record Abbreviations Key Abbreviations 1. ANSI- The American National Standards Institute 2. ASC X12- Accredited Standards Committee X12 3. ASET- Administrative Simplification Enforcement Tool 4. ASP- Application Service Provider 5. ATM- Automatic teller machine 6. DDE- Direct Data Entry 7.

Preview. Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences, Third Edition employs a problem-focused approach to present a clear and comprehensive introduction to research methods. Award-winning teacher, author, and advisor Gregory J. Privitera fully integrates the research methods decision tree into the text to help students choose the most ...

Introduction; 2.1 Overview of Managerial Decision-Making; 2.2 How the Brain Processes Information to Make Decisions: Reflective and Reactive Systems; 2.3 Programmed and Nonprogrammed Decisions; 2.4 Barriers to Effective Decision-Making; 2.5 Improving the Quality of Decision-Making; 2.6 Group Decision-Making; Key Terms; Summary of Learning Outcomes; Chapter Review Questions

Problem. 1O. Step-by-step solution. Step 1 of 3. The major purpose of medical insurance billing experts is to aid in the accounting process, assisting patients in getting optimal insurance plan advantages while also assuring a revenue to the health care organisation where they work. Revenue is the overall income generated by a medical practise ...

Critical Thinking Questions; Personal Application Questions; 14 Stress, Lifestyle, and Health. Introduction; 14.1 What Is Stress? 14.2 Stressors; 14.3 Stress and Illness; 14.4 Regulation of Stress; 14.5 The Pursuit of Happiness; Key Terms; Summary; Review Questions; Critical Thinking Questions;

claim attachments. Documents that contain information, hard copy or electronic, related to a completed insurance claim that assists in validating the medical necessity or explains the medical service or procedure for payment (e.g., operative report, discharge summary, invoice). clearinghouse. An independent organization that receives insurance ...