Find adoption answers, support, training, or professional resources

- Mission and Vision

- Staff and Board

- Internships

- Media & Press Room

- Job Openings for Adoption Professionals

- Social Work CE

- Training for Professionals

- Pre-Adoptive Parents

- Adoptive Parents

- Adopted Persons

- Birth Parents

- Expectant Parents

- Adoption Advocate Publication

Adoption by the Numbers

Profiles in adoption.

- Take Action

- Upcoming Events

- Adoption Hall of Fame

- National Adoption Conference

- Legacy Society

- Families For All Development Fund

- Family Formation Partners

- Annual Report

Adoption Research

We provide accurate, reliable, and up-to-date reports that inform and equip professionals, policymakers, and the public at large to improve and strengthen adoption.

In 2021, we conducted the largest survey ever of adoptive parents. NCFA explored the profile of adoptive parents, their experiences, and what has changed in adoption over time.

In 2022, we surveyed birth parents across the U.S. and conducted focus groups with birth moms to better understand this diverse population, their decision-making and levels of satisfaction, their relationship with their birth children, experiences with stigma and support, and much more.

In 2023, we researched the experiences of adult adoptees through a nationwide survey.

The Importance of Adoption Research

Policymakers and legislators look to research-based facts and statistics to inform their decision-making. Professionals draw from the most recent studies and reports to better understand the needs of the populations they are serving and identify areas for growth in their work. Members of the media, authors, and other content creators look to NCFA's expertise to help them identify the most relevant and accurate information about adoption as they cover current events and raise awareness about stories and issues in adoption.

A comprehensive study of adoption data from 2019 and 2020 across all 50 states.

An ongoing research project to explore the demographic characteristics and personal experiences of adoptive parents, birth parents, and adoptees.

General Adoption Statistics & Data

Quick links to the most recent national statistics

- Trends by type of adoption

- Adoptions from Foster Care

- Intercountry Adoptions

- Nationally Representative Data on Adoption Children in the United States

Start typing & press 'enter'

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Clinical Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 26 May 2021

Family environment and development in children adopted from institutionalized care

- Margaret F. Keil 1 ,

- Adela Leahu 1 ,

- Megan Rescigno 2 ,

- Jennifer Myles 3 &

- Constantine A. Stratakis 1

Pediatric Research volume 91 , pages 1562–1570 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7294 Accesses

1 Citations

132 Altmetric

Metrics details

After adoption, children exposed to institutionalized care show significant improvement, but incomplete recovery of growth and developmental milestones. There is a paucity of data regarding risk and protective factors in children adopted from institutionalized care. This prospective study followed children recently adopted from institutionalized care to investigate the relationship between family environment, executive function, and behavioral outcomes.

Anthropometric measurements, physical examination, endocrine and bone age evaluations, neurocognitive testing, and behavioral questionnaires were evaluated over a 2-year period with children adopted from institutionalized care and non-adopted controls.

Adopted children had significant deficits in growth, cognitive, and developmental measurements compared to controls that improved; however, residual deficits remained. Family cohesiveness and expressiveness were protective influences, associated with less behavioral problems, while family conflict and greater emphasis on rules were associated with greater risk for executive dysfunction.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that a cohesive and expressive family environment moderated the effect of pre-adoption adversity on cognitive and behavioral development in toddlers, while family conflict and greater emphasis on rules were associated with greater risk for executive dysfunction. Early assessment of child temperament and parenting context may serve to optimize the fit between parenting style, family environment, and the child’s development.

Children who experience institutionalized care are at increased risk for significant deficits in developmental, cognitive, and social functioning associated with a disruption in the development of the prefrontal cortex. Aspects of the family caregiving environment moderate the effect of early life social deprivation in children.

Family cohesiveness and expressiveness were protective influences, while family conflict and greater emphasis on rules were associated with a greater risk for executive dysfunction problems.

This study should be viewed as preliminary data to be referenced by larger studies investigating developmental and behavioral outcomes of children adopted from institutional care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Metabolic network analysis of pre-ASD newborns and 5-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Mendelian randomization analyses reveal causal relationships between brain functional networks and risk of psychiatric disorders

Introduction.

The science of early childhood development is clear about the importance of early experiences, caregiving environment, and environmental threats on biological, cognitive, and behavioral development. Young children exposed to institutionalized care, which often corresponds with social deprivation and low caregiving quality, have an increased risk for behavioral problems and psychopathology. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Intervention studies of children who experienced institutionalized care and are later adopted or placed into foster care provide evidence that a more favorable caregiving environment may lead to improved outcomes in growth, health, and development, and an overall reduced risk for psychopathology 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 and may reverse the negative effects of early deprivation on hypothalamic pituitary axis functioning and neurobehavioral development. 8 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

Prior studies have addressed the effects of institutionalized care on neurodevelopment and identified significant deficits in cognitive and social functioning, and developmental delay in children adopted post institutionalization. 3 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Age at adoption and time spent in institutionalization are associated with significant and often detrimental effects on overall outcomes. 21 , 22 Institutionalized care and accompanying stimulus deprivation affect the development of the prefrontal cortex. 23 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 The prefrontal cortex has a key role in the development and regulation of executive functions as well as the control of the autonomic system balance. Executive functions refer to a group of higher-order cognitive processes that coordinate the planning and execution of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, as well as the storage of information in working memory. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Executive skills are critical building blocks for the early development of cognitive and social capabilities; the gradual acquisition of these skills correspond to the development of the prefrontal cortex and other brain areas from infancy to adulthood. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39

There is a paucity of research about post-adoption parenting styles that may promote recovery in children after institutionalized care. Ample evidence supports that the early caregiving environment is a consistent predictor of developmental outcomes and executive skills. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 The developing executive function system is influenced by a child’s experiences, response to stress, and structural and molecular changes associated with changes in the hormonal milieu in the brain during sensitive periods of development. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) has a critical role in human brain development and cognition likely due to the effects of this steroid in enhancing brain plasticity. 45 , 46 Results of recent studies suggest that DHEA affects the development of cortico-amygdala 46 and cortico-hippocampal functions 47 that are important to encoding and processing of emotional, spatial, and social cues, as well as attention and working memory processes. In addition, steroids that are DHEA precursors, such as progesterone and allopregnanolone, have critical roles in neuroprotection. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39

In this prospective study, we followed the development of children who experienced institutionalized care 2 years post adoption by a family in the United States. We examined the relationship between family environment, growth, endocrine and levels of neurosteroids, executive functioning, and cognitive development in children adopted from institutionalized care and non-adopted controls to identify factors related to developmental recovery and behavioral outcomes.

Participants

We recruited children adopted from institutionalized care in Eastern Europe within 2 months of adoption by a US family. Eligible participants had no history of significant medical, developmental, or behavioral problems. Participants were screened to determine that they spent at least 8 months in the institution/orphanage setting and were placed in the institution/orphanage at 6 months of age or less. Participants were recruited from local adoption referral centers. Child participants were recruited for a control group and were cohort age–sex-matched with the adopted subjects. The controls were healthy children with no history of significant medical, psychological, or behavioral disorders. Exclusion criteria for the study included documented history of growth hormone deficiency, history of chronic illness (i.e., renal failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes, hypothyroidism, chromosomal abnormalities, medical conditions known to be associated with developmental delay (i.e., fetal alcohol syndrome (subjects were screened using criteria developed by Hoyme et al. 48 )) chronic infectious disease (e.g., AIDS, hepatitis), or precocious puberty. Socio-economic scores were similar between groups.

Participants were seen at baseline (within 2 months of arrival in the United States for adopted subjects) at 1- and 2-year follow-up. All studies were conducted under protocol 06-CH-0223 that was approved by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from the parent/legal guardian. A total of 11 adopted children and 27 controls were recruited. Ten adopted children and 19 controls completed at least two follow-up visits and were included in the analysis. The study was closed to recruitment earlier than anticipated due to the suspension of adoptions from Eastern Europe to the United States.

Anthropometric measurements, physical examination, neurocognitive testing, behavioral questionnaires, and endocrine labs and bone age (adopted children only) were evaluated over a 2-year period. Anthropometric measures included height, weight, body mass index (BMI), mid-arm circumference (MAC), triceps skinfold (TSF), subscapular skinfold (SSF), waist circumference (WC), and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) by a registered dietitian.

Due to the participants’ age and ethical issues related to procedures that expose healthy child participants to risk, blood and bone age x-rays to assess nutritional and endocrine status were obtained for adopted children only (along with clinically indicated laboratory tests). Serum cortisol, DHEA, testosterone, estradiol, and serum neurosteroid profile were also collected (convenience sample: between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m.).

Neurocognitive testing was performed by a pediatric neuropsychologist and included either the Bayley III or Differential Abilities Scale II (DAS) based on age-appropriate guidelines. Behavioral questionnaires included Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function- Preschool (BRIEF-P), Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA), Colorado Child Temperament Inventory (CCTI), and Family Environment Scale (FES). Waters Attachment Behavior Q-sort (AQS) assessment of child attachment (Waters, SUNY) was performed by two trained observers at the initial visit.

The Bayley III is a clinical evaluation by a trained clinician to identify developmental issues in infants and toddlers and consists of the following domains, adaptive behavior, cognition, language, motor skills, and social–emotional capacities. Mean scores for scales are 10, with an SD of three. 49 The DAS is a nationally normed (US) battery of cognitive and achievement tests for children aged 2 years 6 months to 17 years 11 months across a range of developmental levels; mean is 100, SD of 15. 50 The CBCL questionnaire is a validated parent-report measure to assess emotional (internalizing and externalizing symptoms) and maladaptive behavior in children. 27 The BRIEF-P is a reliable, valid parent-report inventory to assess executive function in preschool children; our analysis focused on the clinical scales of: inhibit (control behavioral response), shift (ability to alternate attention), emotional control (regulate emotional responses), working memory (ability to hold information when completing a task), plan/organization (to plan, organize), and Global Executive Composite (GEC). Scores on the CBCL and BRIEF-P are normalized to a mean of 50 (SD 10), with higher scores indicative of greater degrees of dysfunction and scores >65 considered to be clinically significant. 51 ITSEA is a validated measure completed by the parent to assess social–emotional problems and competence in children (1–3 years of age) and is comprised of four domains, externalizing (impulsive, aggression), internalizing (depression, anxiety, separation distress, inhibition to novelty), dysregulation (sleep problems, negative emotions, sensory sensitivity), and competence (attention, compliance, play, mastery, empathy, prosocial peer relations). 52

The CCTI is a validated inventory designed to assess the temperament of children by parental report. 53 The FES is a self-reported questionnaire to assess social climate and environmental family characteristics and family functioning and emotions. The FES is categorized into three domains with ten subscales—relationship dimensions (cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict), personal growth dimensions (independence, achievement orientation, intellectual–cultural orientation, active–recreational orientation, and moral–religious aspect), and system maintenance dimensions (organization and control). 54 The AQS is widely used to assess child attachment behavior and is based on Ainsworth’s study of secure attachment behavior in infants. The AQS assesses the correlation between secure attachment type and child–parent boundaries and has high validity. The AQS security score is the correlation of a specific child’s Q-sort to prototypical secure child and the score range is from −1.0 to +1.0. 55 , 56

We hypothesized that aspects of the family environment, as measured by FES, would be associated with outcome measures of cognitive, executive function, and behavioral problems.

Statistical analysis

To compare children of different ages, anthropometric measurements, and cognitive function scores were converted to z -scores (the difference between the child’s measurement/score and the age mean or the mean provided by standardized cognitive test, divided by the standard deviation (SD)). For length, height, weight, BMI, OFC, MAC, TSF, SSF, and WC z -scores were calculated using the program PediTools, 57 based on means for age and SDs obtained by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)). The CDC provides a set of growth measurements that are standardized among an ethnically diverse population.

Descriptive statistics were examined, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to evaluate group differences in growth, cognitive, and behavior problems. Statistical comparisons included paired t tests, ANOVAs, correlation, and regression analysis. Regression analyses were conducted to examine which aspects of the family environment predicted cognitive or behavioral outcome measures. Analyses were conducted using the SPSS software. A p value <0.05 was considered for statistical significance.

There was no significant age or sex difference between adopted and control groups at the initial visit (adopted: 27.5 ± 9.3 months (range 14–40 months), 6 females, 4 males; control: 30.7 ± 14 months (range 10–58 months), 9 females, 10 males). For adopted subjects, the average time spent in institutionalized care was 23.6 ± 9 months. All the adopted children in our study were engaged with early intervention educational services.

At baseline, adopted subjects had significantly lower z -scores for height/length, weight, OFC, and MAC compared to controls ( p < 0.5). At baseline, one adopted subject had height and weight z -score <2 SD, compared to one subject in the control group with weight <2 SD; six adopted subjects had OFC <2 SD compared to one control subject with OFC <2 SD. No significant differences were found for z -scores for TSF or SSF or WC. At 2-year follow-up, adopted subjects showed significant improvement in z -scores of height and weight; there were no differences between the two groups for anthropometric measures. For adopted subjects at follow-up, one child had weight SD < 2 SD and four children had OFC < 2 SD. OFC was not obtained in most control subjects at 2-year follow-up. (Table 1 ).

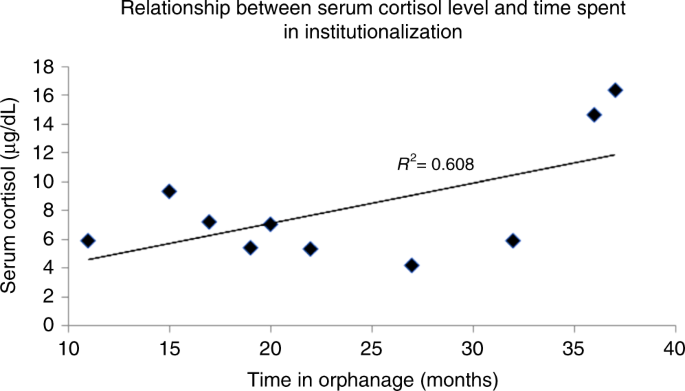

Endocrine and metabolic measures (adopted children)

Serum cortisol was obtained between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. The range of cortisol levels was 4.2 to 16.3 μg/dL. Time in orphanage care was positively associated with serum cortisol at baseline ( R 2 = 0.61, p < 0.06) (Fig. 1 ). Due to the small sample size, the two outliers with longer time in orphanage care may have skewed the results; however, serum cortisol levels at follow-up were not statistically different from baseline values. We planned to collect salivary cortisol levels (diurnal) for both adopted and control subjects; however, due to poor compliance or lack of ample quantity of sample collected, there was insufficient data for analysis. At baseline, thyroid function results were within normal limits, except for one child who had mildly elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone with normal free T4, which normalized at follow-up visit. Other endocrine hormone levels were within normal limits for age/sex. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) z -scores at baseline (0.62 ± 0.2, 1.2 ± 0.3, respectively) and follow-up (0.43 ± 0.3, 1.58 ± 0.3, respectively) were within normal range. Growth factors were not a predictor of cognitive outcome. At the initial visit, bone age was consistent with chronological age in five children, advanced in three children, and delayed in two children. At follow-up, bone age was consistent with chronological age in six, advanced in two, and delayed in two children.

Cortisol levels in adopted children: time in orphanage care is positively correlated with serum cortisol at baseline ( r 2 = 0.608, p < 0.06). Serum cortisol was obtained between 11 am and 1 pm. (convenience sample). Cortisol levels ranged from 4.2 to 16.3 μg/dL.

A serum lipid panel was obtained (convenience sample, non-fasting). At baseline, serum cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels were within normal limits for age. Serum high-density lipoprotein levels were <40 mg/dL in six of the ten subjects, and at follow-up remained <40 mg/dL in two of the nine subjects.

Serum neurosteroids were measured at baseline ( n = 6) and follow-up ( n = 9) by isotope dilution high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. 58 Allopregnanolone levels were within the expected range for the assay and levels were similar to a recent report in a healthy population of toddlers that found no significant diurnal variation, as well as no differences between males and females, in the first 3 years of life. 59 Serum tetrahydro-11 deoxycortisol, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone, and DHEA levels were at the lower limit of detection for the assay and did not change in the six subjects who had both baseline and follow-up measured (Table 2 ).

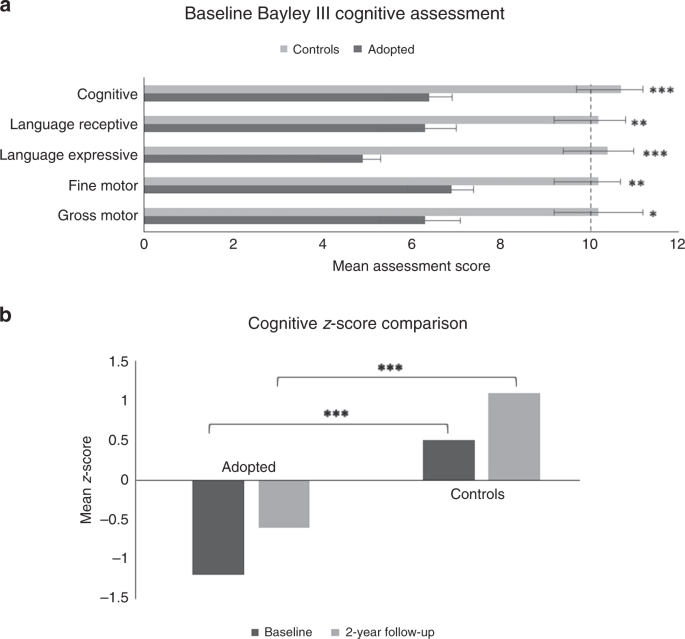

Cognitive data

At baseline, adopted subjects had significantly lower scores compared to controls on all cognitive measures (Bayley III): cognitive, language receptive, language expressive, fine motor, and gross motor ( n = 9 of adopted and 10 of controls were age appropriate for testing with Bayley III). To compare changes in scores from baseline to follow-up, overall cognitive z -scores were calculated ( z -score of Bayley III or DAS General Cognitive Ability) and ANOVA analysis was performed. At baseline, general cognitive z -scores were significantly lower for adopted vs. controls; at 2-year follow-up, there was a trend for improvement in scores for adopted; however, residual differences remained compared to controls. For adopted subjects, lower OFC z -scores (baseline) were associated with lower cognitive scores at follow-up (Table 3 and Fig. 2 ).

a Comparison of mean scores on Bayley III at baseline. Adopted subjects had significantly lower scores in all subscales compared to controls. b Comparison of baseline and follow-up cognitive z -scores. Adopted subjects had significantly lower z -scores at baseline and although a trend was noted for improvement in adopted subjects’ scores from baseline to follow-up, residual differences remained. Error bars indicate standard error. * P < 0.05.

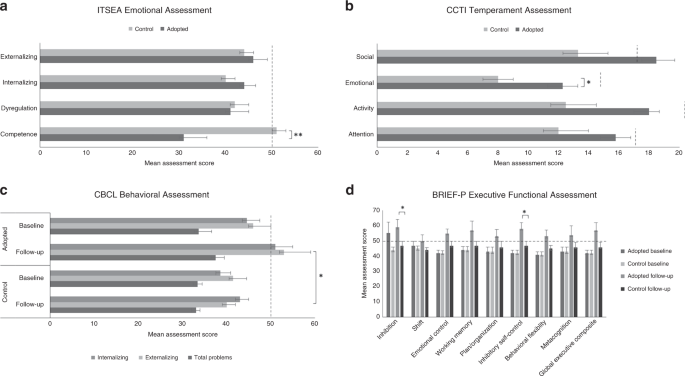

Behavioral data

At baseline, adopted children had significantly lower scores than controls for the ITSEA competence subscale ( p < 0.001; F = 19.017); lower scores are associated with lower social–emotional competence. Since most subjects were above the age limit for use of ITSEA at follow-up, these data were not included in the analysis. At baseline, adopted children had significantly higher scores on the emotional subscale of the CCTI compared to controls ( p < 0.03; F = 5.516). Baseline CBCL results showed no difference between the adopted and control group for any subscale scores. At 2-year follow-up, adopted children had significantly higher scores on externalizing symptom subscales compared to controls ( p < 0.03; F = 5.251).

For adopted subjects at baseline, parent responses for the BRIEF endorsed clinically significant inhibitory control in half the children ( p < 0.05; F = 4.424); no significant difference was found between the adopted and control groups for other subscales. At follow-up the adopted group had significantly higher scores (higher scores associated with more problems) compared to controls for the following subscales: inhibition ( p < 0.04; F = 5.027), inhibitory self-control ( p < 0.03; F = 5.328), with a trend noted for working memory and GEC (Fig. 3 ).

Comparison of mean scores on a ITSEA-Emotional Assessment (baseline); b CCTI-Temperament Assessment (baseline); c CBCL-Behavioral Assessment (baseline and follow-up); and d BRIEF-P-Executive Function (baseline and follow-up) of adopted vs. controls. Error bars indicate standard error. * P < 0.05.

Waters Q attachment scores showed no difference in attachment between adopted children and controls; AQS scores strongly correlated with norms for a sensitive response. Based on that, we concluded that there were no differences between parents’ sensitivity and child attachment in either group and their secure–insecure attachment distribution was comparable with that of normative groups (data not shown). FES scores at baseline showed a significant difference for only the independence subscale score between adopted vs. control groups ( p < 0.05; F = 4.418).

To identify sociodemographic and family environment factors associated with increased risk for executive dysfunction or behavioral problems, a correlational analysis was performed between demographic variables of child gender and age and executive function variables to determine possible covariate variables. Sex was not significantly correlated with any executive function variables and therefore not included in any future analysis. However, age at baseline was significantly correlated with BRIEF subscales; correlation and linear regression analyses were used for these executive function variables.

For adopted subjects, the baseline FES subscales control and conflict were predictors of higher GEC scores at follow-up (BRIEF measure; higher scores associated with dysfunction) ( R 2 = 0.91; F = 14.48, p = 0.03). FES subscale achievement positively correlated with change in cognitive z -scores ( R 2 = 0.433; F = 6.106, p = 0.04). FES subscales cohesion and expressiveness were negatively associated with a change in internalizing scores of CBCL ( R 2 = −0.9; p = 0.04), that is, greater cohesion and expressiveness were associated with lower scores on internalizing symptoms of CBCL. FES subscale control was a predictor of a higher internalizing score (CBCL) at follow-up ( R 2 = 0.74; F = 10.893, p = 0.03); greater emphasis on rules and procedures were associated with more internalizing symptoms, which is a reflection of mood disturbance (i.e., anxiety, depression, social withdrawal). CCTI emotionality was associated with an increase in externalizing scores of CBCL for adopted subjects ( R 2 = 0.97; p < 0.005) (Tables 4 and 5 ).

This prospective study followed the development of children adopted from institutionalized care for 2 years post adoption compared to controls. Broadly, our findings are consistent with the literature, showing significant but not complete growth and developmental recovery post adoption for children exposed to institutionalized care. Kroupina et al. 28 reported that growth factors (IGFBP3) at baseline were a negative predictor and change of head circumference and cognitive scores at 6 months were positive predictors, of cognitive outcomes at 30 months post adoption. Our data did not show a correlation between baseline growth factor z -scores and cognitive outcome at follow-up, perhaps due to the constraints of our small sample size. However, OFC z -scores at baseline were a predictor of cognitive scores at 2-year follow-up. Also, Kroupina et al. 28 reported that smaller stature at baseline and weight gain were associated with improved height outcome at 30- month follow-up, and younger age and lower weight at baseline were a predictor of better catch-up growth. Our data did not replicate the findings of Kroupina et al. 28 regarding predictors of catch-up growth, likely due to the constraints of our sample size. Baseline z -scores for height, weight, and OFC were similar between our study and Kroupina et al., 28 which had a larger sample size. As expected, there was a negative correlation between time in orphanage care and baseline height and weight z -scores. Consistent with previous studies, 8 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 34 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 our results support specific aspects of the family environment that are associated with executive function and behavioral symptomology 2 years after adoption. 65 , 66 Specifically, greater conflict and less flexible rules in a family were predictors of higher scores of global executive dysfunction. BRIEF scores reflect the parent’s observations of the child’s everyday executive functioning relative to the parent’s expectations (not an absolute level of functioning) and thus serve as a screening tool for executive dysfunction. Also, in this study, adopted children were found to have higher scores for behavioral inhibition, an aspect of temperament characterized as social reticence that is reported to be stable across childhood and is associated with greater risk for developing social withdrawal, anxiety disorders, and internalizing problems. Prior studies report that developmental outcomes associated with behavioral inhibition can be influenced by the caregiving context; authoritarian style (i.e., lack of emotional warmth, non-transparent declaration of rules, and high levels of control) is detrimental for social developmental outcomes. 67

Family cohesion and expressiveness were a protective influence; at 2-year follow-up, stronger family cohesion and expressiveness were associated with lower internalizing scores (i.e., less problems with mood disturbance, including anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal). Prior studies of internationally adopted children reported either higher mean internalizing symptoms or no differences in internalizing scores between adopted vs. non-adopted children. 66 , 68 , 69 Consistent with prior studies, we found higher externalizing scores (i.e., greater problems with aggression, conflict, and violation of social norms) on the CBCL at 2-year follow-up for adopted children that were associated with higher emotionality scores on CCTI. 70 Scores on the FES at baseline did not differ significantly between groups, suggesting that there were no differences in perceived family characteristics between adopted and controls. 54

As expected, at baseline visit there were significant differences in measures of cognitive function between adopted children and controls; overall mean scores improved but remained lower than controls at 2-year follow-up. Cognitive scores were negatively associated with OFC z -scores (baseline visit). At baseline, compared to controls, adopted children scored lower on measures of competence (as measured by ITSEA) and scored higher (associated with more problems) on measures of emotionality (as measured by CCTI) and inhibitory control (as measured by BRIEF). At follow-up, adopted children scored higher (associated with more problems) on measures of externalizing symptoms, inhibition, inhibitory self-control, behavioral flexibility, working memory, and GEC (BRIEF). The developing executive function system is influenced by a child’s experiences and response to stress, which impacts the developing prefrontal cortex. In this study, although the measurement of neurosteroids did not reveal any relationship to measures of cognitive or behavioral symptomology; the small sample size and lack of data in the control group limit interpretation and future research is warranted.

We did not identify differences in attachment measures in adopted vs. controls. We observed “indiscriminate friendliness” in many of the adopted subjects, as has been described in the literature. 5 , 63 Our observations are consistent with prior studies that note indiscriminate sociability in children with secure attachment. 71 , 72

The strengths of this study are the prospective design and the differentiation of behavioral issues noted at adoption placement versus those that manifest later. Limitations of the study include the small number of participants (the study was terminated prematurely due to the cessation of adoptions from East Europe). Another limitation was that measures of internalizing, externalizing behaviors, and executive function included only parental assessments of behavior. Also, the lack of salivary cortisol data (due to either inadequate quantity of samples collected or poor compliance with collection in this infant/toddler population) is regrettable since salivary cortisol levels are widely used and are an invaluable tool for pediatric studies and would have provided useful information for comparison of adopted and control subjects.

This study, in the context of a small sample size, should be viewed as a pilot study in the field of developmental pediatrics. Here we find that specific aspects of the family caregiving environment moderate the effects of social deprivation during early childhood on executive function and behavioral problems. These findings provide preliminary data for larger studies that will further investigate the developmental effects that manifest in institutionalized children.

In summary, findings from this study support a cohesive and expressive family environment moderated the effect of prior pre-adoption adversity on cognitive and behavioral development in toddlers. Family conflict and greater emphasis on rules/procedures were associated with a greater risk for behavioral problems at 2-year follow-up. Early assessment of child temperament child and parenting context may provide useful information to optimize the fit between parenting style, family environment structure, and the child’s development.

Harlow, H. F. Total social isolation: effects on macaque monkey behavior. Science 148 , 666 (1965).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Heim, C. & Nemeroff, C. B. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol. Psychiatry 49 , 1023–1039 (2001).

Gunnar, M. R. & van Dulmen, M. H., International Adoption Project T. Behavior problems in postinstitutionalized internationally adopted children. Dev. Psychopathol. 19 , 129–148 (2007).

Smyke, A. T., Dumitrescu, A. & Zeanah, C. H. Attachment disturbances in young children. I: the continuum of caretaking casualty. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 41 , 972–982 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tizard, B. & Rees, J. The effect of early institutional rearing on the behaviour problems and affectional relationships of four-year-old children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 16 , 61–73 (1975).

Rutter, M. et al. Early adolescent outcomes of institutionally deprived and non-deprived adoptees. III. Quasi-autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48 , 1200–1207 (2007).

Hellerstedt, W. L. et al. The International Adoption Project: population-based surveillance of Minnesota parents who adopted children internationally. Matern. Child Health J. 12 , 162–171 (2008).

Kroupina, M. G. et al. Adoption as an intervention for institutionally reared children: HPA functioning and developmental status. Infant Behav. Dev. 35 , 829–837 (2012).

O’Connor, T. G. Early experiences and psychological development: conceptual questions, empirical illustrations, and implications for intervention. Dev. Psychopathol. 15 , 671–690 (2003).

Rutter, M. et al. Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: disinhibited attachment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48 , 17–30 (2007).

Weitzman, C. & Albers, L. Long-term developmental, behavioral, and attachment outcomes after international adoption. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 52 , 1395–1419 (2005).

Article Google Scholar

De Kloet, E. R., Vreugdenhil, E., Oitzl, M. S. & Joels, M. Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr. Rev. 19 , 269–301 (1998).

PubMed Google Scholar

Heim, C., Plotsky, P. M. & Nemeroff, C. B. Importance of studying the contributions of early adverse experience to neurobiological findings in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 29 , 641–648 (2004).

Suomi, S. J., Delizio, R. & Harlow, H. F. Social rehabilitation of separation-induced depressive disorders in monkeys. Am. J. Psychiatry 133 , 1279–1285 (1976).

Meaney, M. J. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24 , 1161–1192 (2001).

Imanaka, A. et al. Neonatal tactile stimulation reverses the effect of neonatal isolation on open-field and anxiety-like behavior, and pain sensitivity in male and female adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav. Brain Res. 186 , 91–97 (2008).

Holmes, A. et al. Early life genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 29 , 1335–1346 (2005).

Brand, A. E. & Brinich, P. M. Behavior problems and mental health contacts in adopted, foster, and nonadopted children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 40 , 1221–1229 (1999).

Leve, L. D., Fisher, P. A. & Chamberlain, P. Multidimensional treatment foster care as a preventive intervention to promote resiliency among youth in the child welfare system. J. Pers. 77 , 1869–1902 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fox, N. A. et al. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at 8 years of age: findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 52 , 919–928 (2011).

Johnson, D. E. Adoption and the effect on children’s development. Early Hum. Dev. 68 , 39–54 (2002).

Beckett, C. et al. Behavior patterns associated with institutional deprivation: a study of children adopted from Romania. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 23 , 297–303 (2002).

Danese, A. & McEwen, B. S. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 106 , 29–39 (2012).

Judge, S. Developmental recovery and deficit in children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 34 , 49–62 (2003).

Kaler, S. R. & Freeman, B. J. Analysis of environmental deprivation: cognitive and social development in Romanian orphans. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 35 , 769–781 (1994).

Miller, L. C., Kiernan, M. T., Mathers, M. I. & Klein-Gitelman, M. Developmental and nutritional status of internationally adopted children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 149 , 40–44 (1995).

Achenbach, T. M. & Rescorla, L. A. Manual for the AESBA School-Age Forms and Profiles (Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont, Burlington, 2001).

Kroupina, M. G. et al. Associations between physical growth and general cognitive functioning in international adoptees from Eastern Europe at 30 months post-arrival. J. Neurodev. Disord. 7 , 36 (2015).

Fishbein, D. H. et al. Mediators of the stress-substance-use relationship in urban male adolescents. Prev. Sci. 7 , 113–126 (2006).

Arnsten, A. F. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10 , 410–422 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ohta, K. I. et al. The effects of early life stress on the excitatory/inhibitory balance of the medial prefrontal cortex. Behav. Brain Res. 379 , 112306 (2020).

Pena, C. J., Nestler, E. J. & Bagot, R. C. Environmental programming of susceptibility and resilience to stress in adulthood in male mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13 , 40 (2019).

Callaghan, B. L., Sullivan, R. M., Howell, B. & Tottenham, N. The international society for developmental psychobiology Sackler symposium: early adversity and the maturation of emotion circuits–a cross-species analysis. Dev. Psychobiol. 56 , 1635–1650 (2014).

Bos, K. J., Fox, N., Zeanah, C. H. & Nelson Iii, C. A. Effects of early psychosocial deprivation on the development of memory and executive function. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 3 , 16 (2009).

Liston, C., McEwen, B. S. & Casey, B. J. Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 912–917 (2009).

Shaw, P. et al. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature 440 , 676–679 (2006).

Lenroot, R. K. et al. Differences in genetic and environmental influences on the human cerebral cortex associated with development during childhood and adolescence. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30 , 163–174 (2009).

Tsujimoto, S. The prefrontal cortex: functional neural development during early childhood. Neuroscientist 14 , 345–358 (2008).

IoMaNR Council. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (The National Academies Press, Washington, 2000).

Dowsett, S. M. & Livesey, D. J. The development of inhibitory control in preschool children: effects of “executive skills” training. Dev. Psychobiol. 36 , 161–174 (2000).

Bell, M. A. & Wolfe, C. D. Emotion and cognition: an intricately bound developmental process. Child Dev. 75 , 366–370 (2004).

Wolfe, C. D. & Bell, M. A. Working memory and inhibitory control in early childhood: Contributions from physiology, temperament, and language. Dev. Psychobiol. 44 , 68–83 (2004).

EKSNIoCHaH Development. The NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD): Findings for Children up to Age 4 1/2 Years (Government Printing Office, Washington, 2006).

Rhoades, B. L., Greenberg, M. T., Lanza, S. T. & Blair, C. Demographic and familial predictors of early executive function development: contribution of a person-centered perspective. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 108 , 638–662 (2011).

Nguyen, T. V. et al. Interactive effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone on cortical thickness during early brain development. J. Neurosci. 33 , 10840–10848 (2013).

Nguyen, T. V. et al. A testosterone-related structural brain phenotype predicts aggressive behavior from childhood to adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 72 , 219 (2016); erratum 63 , 109–118 (2016).

Nguyen, T. V. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone impacts working memory by shaping cortico-hippocampal structural covariance during development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 86 , 110–121 (2017).

Hoyme, H. E. et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics 115 , 39–47 (2005).

Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development: Administration Manual 3rd edn (Pearson Psychcorp, San Antonio, 2006).

Elliott, C. D., Salerno, J. D., Dumont, R. & Willis, J. O. The Differential Ability Scales—Second Edition: Contempory Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues (Guilford Press, 2018).

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C. & Kenworthy, L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Preschool Edition (PAR Inc., Lutz, 2000).

Carter, A. S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Jones, S. M. & Little, T. D. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 31 , 495–514 (2003).

Rowe, D. C. & Plomin, R. Temperament in early childhood. J. Pers. Assess. 41 , 150–156 (1977).

Moos, R. H. & Moos, B. S. Family Environment Scale Manual (Consulting Psychologist Press, Palo Alto, 1981).

Ainsworth, M. D. S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 1978).

Waters, E. D. K. Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 50 , 41–65 (1985).

Chou, J. H., Roumiantsev, S. & Singh, R. PediTools Electronic Growth Chart Calculators: applications in clinical care, research, and quality improvement. J. Med. Internet Res. 22 , e16204 (2020).

Parikh, T. P. et al. Diurnal variation of steroid hormones and their reference intervals using mass spectrometric analysis. Endocr. Connect. 7 , 1354–1361 (2018).

Fadalti, M. et al. Changes of serum allopregnanolone levels in the first 2 years of life and during pubertal development. Pediatr. Res. 46 , 323–327 (1999).

McGuinness, T. M. & Dyer, J. G. International adoption as a natural experiment. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 21 , 276–288 (2006).

Albers, L. H. et al. Health of children adopted from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Comparison with preadoptive medical records. JAMA 278 , 922–924 (1997).

Benoit, T. C., Jocelyn, L. J., Moddemann, D. M. & Embree, J. E. Romanian adoption. The Manitoba experience. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 150 , 1278–1282 (1996).

Chisholm, K. A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child Dev. 69 , 1092–1096 (1998).

Rutter, M., English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following adoption after severe global early privation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 39 , 465–476 (1998).

Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van, I. M. H. The importance of parenting in the development of disorganized attachment: evidence from a preventive intervention study in adoptive families. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46 , 263–274 (2005).

Schoemaker, N. K. et al. A meta-analytic review of parenting interventions in foster care and adoption. Dev Psychopathol. 46 , 1–24 (2019).

Guyer, A. E. et al. Temperament and parenting styles in early childhood differentially influence neural response to peer evaluation in adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43 , 863–874 (2015).

Hawk, B. N. et al. Caregiver sensitivity and consistency and children’s prior family experience as contexts for early development within institutions. Infant Ment. Health J. 39 , 432–448 (2018).

McCall, R. B. et al. Early caregiver-child interaction and children’s development: lessons from the St. Petersburg-USA orphanage intervention research project. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 22 , 208–224 (2019).

Juffer, F. & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: a meta-analysis. JAMA 293 , 2501–2515 (2005).

O’Connor, T. G. et al. Child-parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Dev. Psychopathol. 15 , 19–38 (2003).

O’Connor, T. G. & Rutter, M., English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Attachment disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: extension and longitudinal follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 39 , 703–712 (2000).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and their families for their participation in this study. We thank Dr. Patrick Mason (International Adoption Center, Fairfax, VA), Dr. Penny Glass (CNMC), Dr. Sharon Singh (CNMC), Dr. Pedro Martinez (NIMH), Dr. Steven Soldin (NIH CC DLM), and Dr. Moommal Shaihh (NICHD) for their assistance. We acknowledge the University of Nevada School of Medicine for support of Dr. Rescigno’s elective rotation with NICHD/NIH. This study was supported by NIH grant Z01-HD008920.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Section on Endocrinology and Genetics, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Margaret F. Keil, Adela Leahu & Constantine A. Stratakis

University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno, NV, USA

Megan Rescigno

Nutrition Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Jennifer Myles

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.F.K.: conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. A.L. and J.M.: collected data and carried out the initial analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript. M.R.: assisted with the analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript. C.A.S.: conceptualized and designed the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Margaret F. Keil .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for participation in this study was obtained from the legal guardians of the participating children.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Keil, M.F., Leahu, A., Rescigno, M. et al. Family environment and development in children adopted from institutionalized care. Pediatr Res 91 , 1562–1570 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01325-1

Download citation

Received : 02 September 2020

Revised : 13 November 2020

Accepted : 02 December 2020

Published : 26 May 2021

Issue Date : May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01325-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Adoption Studies

- First Online: 01 August 2023

Cite this chapter

- Barbara Steck 2

188 Accesses

Research in the field of adoption has been ongoing for decades, including studies of interactions of genetic, family, and environmental influences on the psychosocial development of adopted children. Numerous variables such as age, gender, protective and risk factors are explored, as well as potential vulnerable situations that contribute to the psychosocial adjustment of adopted children or lead to psychosocial disorders. Other investigations seek to identify key differences in early versus late adopted children, in national versus international adoptions and in open adoption. Adoption is uniformly described in the literature as the best solution for the development of a child without a family, compared to institutional or foster care placement. Research findings allow a unique insight into the malleability of child development, demonstrating children’s ability to recovery from adversities in infancy. Risk or higher vulnerability are recorded among children with adverse pre- adoptive experiences such as neglect, maltreatment, or multiple placements. Most adoptees do not suffer from mental or somatic illnesses and show little or no influence of adoption on their personal development.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Internalizing problems are characterized by anxious and depressive symptoms, social withdrawal, and somatic complaints. Externalizing problems are defined as aggressive, oppositional, and delinquent behavior.

Attachment Disorders are psychiatric illnesses that can develop in young children who have problems in emotional attachments to others (American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry)

Racially different parents and children in adoptive families

The teaching of coping skills to help children deal effectively with racism and discrimination.

See also: Antares [ 161 ].

Racial identity and ethnic identity are terms that refer broadly to how individuals define themselves with respect to race and/or ethnicity.

Examples of adoption microaggression types include: “Biology is Best,” which conveys an assumption that biological or blood ties are superior; “Grateful adoptee,” which conveys an assumption that adoptees are lucky to have been adopted and should be grateful; and “Phantom Birth Parents,” which conveys an assumption that birth parents are no longer important once they relinquish parental rights ([ 172 ]: pp. 13–14).

The secret, closed, or confidential adoption definition refers to an adoption, in which the prospective birth mother chooses to keep her identity private and exchanges no contact with the adoptive family during or after the adoption process.

Child outcomes included their satisfaction with the degree of openness and their curiosity about their birthparents, global self-worth, understanding of adoption and aspects of socio-emotional adjustment.

Characteristics of collaborative relationships: proactive management of the logistics of openness arrangements; management of fears, management of communication flow to the child in a way that is developmentally appropriate; empathy for the child’s adoptive situation; empathy for the child’s birthmother; maintaining appropriate generational boundaries; and effective management of outside influences, such as agency or extended kin.

Disruption: the adoption process ends before the adoption is legally finalized. Dissolution : the legal relationship between the adoptive parents and adoptive child is ceased - voluntarily or involuntarily - after the adoption is legally finalized. In both situations, the child is placed in foster care or with new adoptive parents.

Compassion fatigue is a condition comprising three elements: burnout, meaning physical and mental exhaustion; secondary trauma stress involving the transfer of trauma symptoms from those who have been traumatized to those who have been hearing the trauma story; and compassion satisfaction which is known to moderate the effects of the other two and is directly related to high quality support from knowledgeable professionals.

Relationship or relational maintenance refers to a variety of behaviors by relational partners in an effort to maintain that relationship; the subjective experience of the relation with the partner may differ with time, the satisfaction within the relationship may increase or decrease.

Johnson DE. Adoption and the effect on children’s development. Early Hum Dev. 2002;68:39–54.

PubMed Google Scholar

Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 2006: adoption as intervention. Meta-analytic evidence for massive catch-up and plasticity in physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1228–45.

Zeanah C. Disturbances of attachment in young children adopted from institutions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:230–6.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Duke ML. Groups secking to climinate adoption. In: Marshner C, Picroce WL, editors. Adoption factbook III.222. Wahington DC: National Council for Adoption; 1999.

Google Scholar

Cohen N. Adoption. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches. Oxford: Blackwell; 2002. p. 373–81.

Hoksbergen R. The importance of adoption for nurturing and enchancing the emotional and intellectual potential of children. Adoption Q. 1999;3(2):29–41.

Jacob F. La logique du vivant. Une histoire de l’hérédité. Paris: Gallimard, coll. « Bibliothèque des sciences humaines » 1970.

Plomin R, Scheier M, Bergeman CS, Pedersen NL, Nesselroade JR, McClearn GE. Optimism, pessimism and mental health: a twin/adoption analysis. Personal Individ Differ. 1992;13(8):921–30.

Plomin R. Genetics and children’s experiences in the family. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1995;56(1):33–68.

Wadsworth SJ, Corley RP, Hewitt J, Plomin R, DeFries JC. Parent-offspring resemblance for reading performance at 7,12 and 16 years of age in the Colorado adoption project. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2002;43(6):769–74.

CAS Google Scholar

Plomin R, Reiss D, Hetherington EM, Howe G. Nature and nurture: genetic influence on measures of the family environment. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:32–43.

Reiss D, Plomin R, Hetherington EM, Howe G, Rovine M, Tryon A, Stanley M. The separate worlds of teenage siblings: an introduction to the study of the nonshared environment and adolescent development. In: Hetherington EM, Reiss D, Plomin R, editors. Separate social worlds of siblings: impact of nonshared environment on development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. p. 63–109.

Wachs TD. The nature-nurture gap: what we have here is a failure to collaborate. In: Plomin R, McClearn GE, editors. Nature, nurture, and psychology. Washington, DC: AOA Books; 1993. p. 375–91.

Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006a;47(3–4):276–95.

Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: multiple varieties but real effects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006b;47(3–4):226–61.

Plomin R. Genetics and developmental psychology. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2004;50(3):341–52.

Poletti M, Gebhardt E, Pelizza L, Preti A, Raballo A. Looking at intergenerational risk factors in Schizophrenia spectrum disorders: new frontiers for early vulnerability identification? Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:566683.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rasic D, Hajek T, Alda M, Uher R. Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt114 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Trubetskoy V, Panagiotaropoulou G, Awasthi S, et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature. 2022;604(7906):502–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04434-5 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Berrettini WH. Are schizophrenic and bipolar disorders related? A review of family and molecular studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(6):531–8.

Giusti-Rodríguez P, Sullivan PF. The genomics of schizophrenia: update and implications. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4557–63. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI66031 .

Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:109–14.

Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Taylor A, Williams B, Newcombe R, Craig IW, Moffitt TE. MAOA, maltreatment, and gene environment interaction predicting children’s mental health: new evidence and a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(10):903–13.

Kozhimannil KB, Kim H. Maternal mental illness. Science. 2014;345(6198):755. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259614 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bergink V, Larsen JT, Hillegers MHJ, Dahl SK, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Petersen L, Munk-Olsen T. Childhood adverse life events and parental psychopathology as risk factors for bipolar disorder. Translational. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e929. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.201 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bountress K, Chassin L. Risk for behavior problems in children of parents with substance use disorder. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(3):275–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000063 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lollis S, Kuczynski L. Beyond one hand clapping: seeing bidirectionality in parent-child relations. J Soc Pers Relationships. 1997;14:441–61.

Peters BR, Atkins MS, McKay M. Adopted children’s behavior problems: a review of five explanatory models. Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19(3):297–328.

Rende R, Plomin R. Nature, nature, and the development of psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, vol. 1 (theory and methods). New York: Wiley; 1995. p. 291–314.

Rutter M, Silberg J, O’Connor TG, Simonoff E. Genetics and child psychiatry: I advances in quantitative and molecular genetics. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1999a;40(1):3–18.

Knafo A, Plomin R. Parental discipline and affection and children’s prosocial behavior: genetic and environmental links. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90(1):147–64.

Plomin R, Fulker DW, Corley R, DeFries JC. Nature, nurture, and cognitive development from 1 to 16 years: a parent-offspring adoption study. Am Psychol Soc. 1997;8:6.

Schleiffer R. Adoption: psychiatrisches Risiko und/oder protektiver Faktor? Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiat. 1997;46:645–59.

Masten AS, Coatswonh JD. Competence, resilience, and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, vol. 2 (risk, disorder, and adaptation). New York: Wiley; 1995. p. 715–52.

Rutter M. Psychosocial resillience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, editor. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1990. p. 181–214.

Cohler BJ, Scott FM, Musick JS. Adversity, vulnerability, and resilience: cultural and development perspectives. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, vol. 2 (risk, disorder, and adaptation). New York: Wiley; 1995. p. 753–800.

McGuinness TM, Dyer JG. International adoption as a natural experiment. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006;21(4):276–88.

Lombroso P, Pauls D, Leckman J. Genetic mechanismen in childhood psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:921–38.

Wierzbicki M. Psychological adjustment of adoptees: a meta-analysis. J Clin Child Psychol. 1993;22:447–54.

Scarr S. Developmental theories for the 1990s: development and individual differences. Child Dev. 1992;63:1–19.

Brand AE, Brinich PM. Behavior problems and mental health contacts in adopted, foster, and nonadopted children. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1999;40(8):1221–9.

Cohen NJ, Coyne J, Duvall J. Adopted and biological children in the clinic: family, parental and child characteristics. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1993;34(4):545–62.

Dance C, Rushton A, Quinton D. Emotional abuse in early childhood: relationships with progress in subsequent family placement. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2002;43(3):395–407.

Fergusson DM, Lynskey M, Horwood LJ. The adolescent outcomes of adoption: a 16-year longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1995;36(4):597–615.

Rutter M, Kreppner JM, O’Connor TG. Specificity and heterogencity in children’s responses to profound institutional privation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:97–103.

Tienari P, Wynne LC. Adoption studies of schizophrenia. Ann Med. 1994;26:223–37.

Verhulst FC, Althaus M, Versluis-den Bieman HJM. Problem behavior in international adoptees: I. an epidemiological study. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(1):94–103.

Tienari P, Sorri A, Lahti I, Naarala M, Wahlberg KE, Pohjola J, Moring J. Interaction of genetic and psychosocial factors in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand., Suppl. No 319. 1985a;71:19–30.

Tienari P, Sorri A, Lahti I, Naarala M, Wahlberg KE, Rönkkö T, Pohjola J, Moring J. The Finnsih adoptive family study of schizophrenia. Yale J Biol Med. 1985b;58:227–37.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tienari P. Implications of adoption studies on schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161(Suppl. 18):52–8.

Tienari P, Wynne LC, Sorri A, Lahti I, Läksy K, Moring J. Genotype-environment interaction in schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. Long-term follow-up study of Finnish adoptees. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:216–22.

Wahlberg KE, Wynne LC, Hakko H, Laksy K, Moring J, Miettunen J, Tienari P. Interaction of genetic risk and adoptive parent communication deviance: longitudinal prediction of adoptee psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1531–41.

Wynne LC, Tienari P, Nieminen P, Sorri A, Lahti I, Moring J, Naarala M, Läksi K, Wahlberg KE, Mittunen J. Genotype-environment interaction in the schizophrenia spectrum: genetic liability and global family ratings in the Finnish Adoption Study. Fam Process. 2006;45(4):419–34.

Myllyaho T, Siira V, Wahlberg KE, Hakko H, Laksy K, Roisko R, Niemela M, Rasanen S. Interaction of genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia and family functioning in adopted-away offspring of mothers with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.017 .

Eley TC, Deater-Deckard K, Fombonne E, Fulker DW, Plomin R. An adoption study of depressive symptoms in middle childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1998;39(3):337–45.

Rice F, Harold G, Thapar A. The genetic aetiology of childhood depression: a review. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2002;43(1):65–79.

Rutter M, the English, Romanian (ERA) Study Team. Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following adoption after severe early privation. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1998;39(4):465–76.

Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Sources of parent-offspring resemblance for major depression in a National Swedish Extended Adoption Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3828 .

Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. An extended Swedish National Adoption Study of Bipolar Disorder Illness and cross-Generational Familial Association with schizophrenia and major depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(8):814–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0223 .

LeMoult J, Humphreys KL, Tracy A, Hoffmeister JA, Ip E, Gotlib IH. Meta-analysis: exposure to early life stress and risk for depression in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(7):842–55.

Cadoret RJ, Troughton E, Bagford J, Woodworth G. Genetic and environmental factors in adoptee antisocial personality. Eur Arch Psychiatr Neurol Sci. 1990a;239:231–40.

Cadoret RJ, Thoughton E, Moreno-Merchant L, Whitters A. Early life psychosocial events and adult affective symptoms. In: Robins LN, Rutter M, editors. Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990b. p. 300–13.

Howe D. Age at placement, adoption experience and adult adopted people’s contact with their adoptive and birth mothers: an attachment perspective. Attach Hum Dev. 2001;3:222–37.

Nickman SL, Rosenfeld AA, Fine P, Macintyre JC, Pilowsky DJ, Howe RA, Derdeyn A, Gonzales MB, Forsythe L, Sveda SA. Children in adoptive families: overview and update. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):987–95.

Collishaw S, Maughan B, Pickles A. Infant adoption: psychosocial outcomes in adulthood. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:57–65.

Howe D. Adoption outcome research and practical judgement. Adopt Foster. 1998a;22(2):6–15.

Howe D. Patterns of adoption: nature, nurture and psychosocial development. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998b.

Howe D, Hinings D. Adopted children referred to a child and family Centre. Adopt Foster. 1987;11:44–7.

Howe D. Parent reported problems in 211 adopted children: some risk and protective factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1997;38(4):401–12.

Humphrey M, Ounsted C. Adoptive families referred for psychiatric advice. Br J Psychiatry. 1963;109:599–608.

Stams GJJM, Juffer F, Rispens J, Hoksbergen RAC. The development and adjustment of 7-year-old children adopted in infancy. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2000;41(8):1025–38.

Maughan B, Collishaw S, Pickles A. School achievement and adult qualifications among adoptees: a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1998;39(5):669–85.

Cederblad M, Höök B, Irhammar M, Mercke AM. Mental health in international adoptees as teenagers and young adults: an epidemiological study. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1999;40:1239–48.

Beckett C, Maughan B, Rutter M, Castle J, Colvert E, Groothues C, Kreppner J, et al. Do the effects of early severe deprivation on cognition persist into early adolescence? Findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Child Dev. 2006;77(3):696–711.

Stams GJM, Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. Maternal sensitivity, infant attachment, and temperament in early childhood predict adjustment in middle childhood: the case of adopted children and their biologically unrelated parents. Dev Psychol. 2002;38(5):806–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.806 .

McDermott JM, Troller-Renfree S, Vanderwert R, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA. Psychosocial deprivation, executive functions, and the emergence of socio-emotional behavior problems. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;77:167.

Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJX. Conclusions: overview of findings from the era study, inferences, and research implications. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2010;75(1):212–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00557.x .

Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Castle JI. Investigating the impact of early institutional deprivation on development: background and research strategy of the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) study. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2010;75(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00548.x .

Stovall KC, Dozier M. Infants in foster care: an attachment theory perspective. Adopt Q. 1998;2:55–88.

Paine AL, Fahey K, Anthony RE, Shelton KH. Early adversity predicts adoptees’ enduring emotional and behavioral problems in childhood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:721–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01553-0 .

Zeanah C. Beyond insecurity: a reconceptualization of attachment disorders in infancy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:42–52.

Jacobsen T, Miller L. Attachment quality in young children of mentally ill mothers: contribution of maternal caregiving abilities. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment disorganization and foster care context. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. p. 347–78.

Liotti G. Disorganization of attachment as a model for understanding dissociative psychopathology. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment disorganization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. p. 291–317.

Perry BD, Pollard RA. Homcostatis stress, trauma and adaptation: a neurodevelopmental view of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1998;7:33–51.

Schore A. Early organization of the nonlinear right brain and development of a predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9:595–631.

Hodges J, Tizard B. Social and family relationship of ex-institutional children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1989;30:77–98.

O’Connor TG, Rutter M, the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Attachment disorder behavior following severe deprivation: extension and longitudinal follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000a;39(6):703–12.

O’Connor TG, Rutter M, Beckett C, Keavency L, Kreppner J, the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. The effects of global severe privation on cognitive competence: extension and longitudinal follow-up. Child Dev. 2000b;71:376–90.

Castle J, Groothues C, Bredenkamp D, Beckett C, O’Connor TG, Rutter M, the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Effects of qualities of early institutional care on cognitive attainment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69:424–37.

Goldstein J, Freud A, Solnit A. Beyond the best interests of the child. 2nd ed. New York: Free Press; 1973.

Bowlby J. Attachment. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

Groze V, Rosenthal JA. Attachment theory and the adoption of children with special needs. Soc Work Res Abstr. 1993;29(2):5–12.

Hughes DA. Adopting children with attachment problems. Cild Welfare. 1999;LXXVIII(5):541560.

Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment disorganization. New York: Guiloford Press; 1999.

Chisholm K. A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from romanian orphanages. Child Dev. 1998;69(4):1092–106.

Juffer F, Hoksbergen AC, Riksen-Walraven JM, Kohnstamm GA. Early intervention in adoptive families: supporting maternal sensitive responsiveness, infant-mother attachment, and infant competence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(8):1039–50.

Rutter M, Andersen-Wood L, Bredenkamp D, Castle J, Groothues C, et al. Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global privation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999b;40(4):537–49.

Woodhouse W, Baily A, Rutter M, Bolton P, Baird G, Le Couteur A. Head circumference and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:665–71.

Gillberg C, Coleman M. The biology of the autistic syndromes. 2nd ed. London: Mac Keith Press; 1992.

Rutter M, Bailey A, Bolton P, Le Couteur A. Autism and known medical conditions: myth and substance. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:311–22.

Chugani HT, Phelps ME. Maturational changes in cerebral function in infants determined by “FDG positron emission tomography”. Science. 1986;231:840–3.

Chugani HT, Phelps ME, Mazziotta JC. Positron emission tomography study of human brain functional development. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:487–97.

Chugani HT, Behen ME, Muzik O, Juhasz C, Nagy F, Chugani DC. Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: a study of postinstitutionalized romanian orphans. Neurolmage. 2001;14:1290–301.

Rutter M, Beckett C, Castle J, Colvert E, Kreppner J, Mehta M, Stevens S, Sonuga-Barke E. Effects of profound early institutional deprivation: an overview of findings from a UK longitudinal study of Romanian adoptees. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2007;4(3):332–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620701401846 .

Article Google Scholar

Erich ST, Leung P. The impact of previous type of abuse and sibling adoption upon adoptive families. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:1045–58.

Hoksbergen R. Die Folgen von Vernachlässigung. Erfahrungen mit Adoptivkindern aus Rumänien. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner; 2003.

van der Vegt EJ, Tieman W, van der Ende J, Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC, Tiemeier H. Impact of early childhood adversities on adult psychiatric disorders: a study of international adoptees. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:724–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0494-6 .

Sonuga-Barke EJS, Kennedy M, Kumsta R, Knights N, Golm D, Rutter M, et al. Child-to-adult neurodevelopmental and mental health trajectories after early life deprivation: the young adult follow-up of the longitudinal English and Romanian Adoptees study. 2017 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30045-4 .

Julian MM. Age at adoption from institutional care as a window into the lasting effects of early experiences. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16(2):101–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0130-6 .

Golombok S, Cook R, Bish A, Murray C. Families created by the new reproductive technologies: quality of parenting and social and emotional development of the children. Child Dev. 1995;66:285–98.

Brodzinsky DM. Long-term outcomes in adoption. In: Behrman RE, editor. The future of children: adoption. Los Altos, CA: Center for the Future of Children, the Davis and Lucile Packard Foundation; 1993. p. 153–66.

Grotevant HD, McRoy RG. Adopted adolescents in residential treatment: the role of the family. In: Brodzinsky DM, Schechter MD, editors. The psychology of adoption. New York: Oxford University Prerss; 1990.

Kotsopoulos S, Cote A, Joseph L, Pentland N, Stavrakaki C, Sheahan P, Oke L. Psychiatric disorders in adopted children. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1988;58(4):608–12.

Hersov L. The seventh annual Jack Tizard memorial lecture, aspects of adoption. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990;34(4):493–510.

Jerome L. Overrepresentation of adopted children attending a children’s mental health center. Can J Psychiatr. 1986;31:526–31.

Kim WJ, Davenport C, Joseph J, Zrull J, Woolford E. Psychiatric disorders and juvenile delinquency in adopted children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:111–5.

Rogeness GA, Hoppe SK, Macedo CA, Fischer C, Harris WA. Psychopathology in hospitalised, adopted children. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:628–31.

Warren SB. Lower threshold for referral for psychiatric treatment for adopted adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:512–7.

Van Ijzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Poelhuis CW. Adoption and cognitive development: a meta-analytic comparison of adopted and nonadopted children’s IQ and school performance. Psyachol Bull. 2005;131(2):301–16.

Bohman M, Sigvardsson S. Outcome in adoption: lessons from longitudinal studies. In: Brozinsky DM, Schechter RMH, editors. The psychology of adoption. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. p. 93–106.

Groza V, Ryan SD. Pre-adoption stress and its association with child behavior in domestic special needs and international adoptions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:181–97.

Hoksbergen R, Juffer F, Waardenburg BC, van de Klippe G. Adopted children at home and at school. The integration after eight years of 116 Thai children in the Dutch society. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1987.

Sharma AR, McGue MK, Benson PL. The psychological adjustment of united adopted adolescents and their nonadopted siblings. Child Dev. 1998;69:791–802.

Verhulst FC, Versluis-den Bieman HJM. Developmental course of problem behaviors in adolescent adoptess. J Am Acad Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(2):151–9.

Versluis-den Bieman HJM, Verhulst FC. Self-reported and parent reported problems in adolescent international adoptees. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1995;56(8):1411–28.

Simmel BD, Barth RP, Hinshaw SP. Externalizing symptomatology among adoptive youth: prevalence and preadoption risk factors. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001;29(1):57–69.

Brodzinsky DM. Adjustment to adoption: a psychosocial perspective. Clin Psychol Rev. 1987;7:25–47.

Hersov L. Adoption. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, Hersov L, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry. 3nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 1994. p. 267–82.

Haugaard JJ. Is adoption a risk factor for the development of adjustment problems ? Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(1):47–69.

Zill N. Adopted children in the United States: a profile based on a national survey of child health (serial 104–33). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1996. p. 104–19.