ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Academic performance in adolescent students: the role of parenting styles and socio-demographic factors – a cross sectional study from peshawar, pakistan.

- 1 Institute of Public Health & Social Sciences, Khyber Medical University, Peshawar, Pakistan

- 2 Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

Academic performance is among the several components of academic success. Many factors, including socioeconomic status, student temperament and motivation, peer, and parental support influence academic performance. Our study aims to investigate the determinants of academic performance with emphasis on the role of parental styles in adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. A total of 456 students from 4 public and 4 private schools were interviewed. Academic performance was assessed based on self-reported grades in the latest internal examinations. Parenting styles were assessed through the administration of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI). Regression analysis was conducted to assess the influence of socio-demographic factors and parenting styles on academic performance. Factors associated with and differences between “care” and “overprotection” scores of fathers and mothers were analyzed. Higher socio-economic status, father’s education level, and higher care scores were independently associated with better academic performance in adolescent students. Affectionless control was the most common parenting style for fathers and mothers. When adapted by the father, it was also the only parenting style independently improving academic performance. Overall, mean “care” scores were higher for mothers and mean “overprotection” scores were higher for fathers. Parenting workshops and school activities emphasizing the involvement of mothers and fathers in the parenting of adolescent students might have a positive influence on their academic performance. Affectionless control may be associated with improved academics but the emotional and psychosocial effects of this style of parenting need to be investigated before recommendations are made.

Introduction

Despite residual ambiguity in the term, definitions over time have identified several elements of “academic success” ( Kuh et al., 2006 ; York et al., 2015 ). Used interchangeably with “student success,” it encompasses academic achievement, attainment of learning objectives, acquisition of desired skills and competencies, satisfaction, persistence, and post-college performance ( Kuh et al., 2006 ; York et al., 2015 ). Linked to happiness in undergraduate students ( Flynn and MacLeod, 2015 ) and low health risk behavior in adolescents ( Hawkins, 1997 ), a vast amount of literature is available on the determinants of academic success. Studies have shown socioeconomic characteristics ( Vacha and McLaughlin, 1992 ; Ginsburg and Bronstein, 1993 ; Chow, 2000 ; McClelland et al., 2000 ; Tomul and Savasci, 2012 ), student characteristics including temperament, motivation and resilience ( Ginsburg and Bronstein, 1993 ; Linnenbrink and Pintrich, 2002 ; Farsides and Woodfield, 2003 ; Valiente et al., 2007 ; Beauvais et al., 2014 ) and peer ( Dennis et al., 2005 ), and parental support ( Cutrona et al., 1994 ; Sanders, 1998 ; Dennis et al., 2005 ; Bean et al., 2006 ) to have a bearing on academic performance in students.

The influence of parenting styles and parental involvement is particularly in focus when assessing determinants of academic success in adolescent children ( Shute et al., 2011 ; Rahimpour et al., 2015 ; Weis et al., 2016 ; Checa and Abundis-Gutierrez, 2017 ; Zhang et al., 2019 ). The influence may be of significance from infancy through adulthood ( Steinberg et al., 1989 ; Weiss and Schwarz, 1996 ; Zahedani et al., 2016 ) and can be appreciated across a range of ethnicities ( Desimone, 1999 ; Battle, 2002 ; Jeynes, 2007 ). Previously, the authoritative parenting style has been most frequently associated with better academic performance among adolescent students ( Steinberg et al., 1989 , 1992 ; Deslandes et al., 1997 , 1998 ; Aunola et al., 2000 ; Adeyemo, 2005 ; Checa et al., 2019 ), while purely restrictive and negligent styles have shown to have a negative influence on academic performance ( Hillstrom, 2009 ; Parsasirat et al., 2013 ; Osorio and González-Cámara, 2016 ). Parenting styles have also been linked to academic performance indirectly through regulation of emotion, self-expression ( Deslandes et al., 1997 ; Weis et al., 2016 ), and self-esteem ( Zakeri and Karimpour, 2011 ).

Significant efforts have been made to explore and integrate factors which influence parenting stress and behaviors ( Belsky, 1984 ; Abidin, 1992 ; Östberg and Hagekull, 2000 ). A number of factors, including parent personality and psychopathology (in terms of extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, depression and emotional stability), parenting beliefs, parent-child relationship, marital satisfaction, parenting style of spouse, work stress, child characteristics, education level, and socioeconomic status have been highlighted for their role in determining parenting styles ( Belsky, 1984 ; Simons et al., 1990 , 1993 ; Bluestone and Tamis-LeMonda, 1999 ; Huver et al., 2010 ; Smith, 2010 ; McCabe, 2014 ). Studies have also highlighted differences between fathers and mothers in how these factors influence them ( Simons et al., 1990 ; Ponnet et al., 2013 ).

Insight into determinants of academic success and the role of parenting styles can have significant impact on policy recommendations. However, most existing data comes from western cultures where individualistic themes predominate. While some studies highlight differences between the two ( Wang and Leichtman, 2000 ), evidence from eastern collectivist cultures, including Pakistan, is scarce ( Masud et al., 2015 ; Khalid et al., 2018 ).

The aim of this study is to identify the determinants of academic performance, including the influence of parenting styles, in adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. We also aim to investigate the factors affecting parenting styles and the differences between parenting behaviors of father and mothers.

Materials and Methods

The manuscript has been reported in concordance with the STROBE checklist ( Vandenbroucke et al., 2014 ).

Study Design

A cross sectional study was conducted by interviewing school-going students (grades 8, 9, and 10) to assess determinants of academic grades including the influence of parenting styles.

The study took place in the city of Peshawar in Pakistan at eight schools, four from the public sector and four from the private sector. The data collection process began in January 2017 concluded in December 2017.

The prevalence of high grades (A and A plus) among adolescent students was between 42.6 and 57.4% in a previous study ( Cohen and Rice, 1997 #248). Based on this, a sample size of 376 students was calculated to study the determinants of high grades in adolescent students with a confidence level of 95%. Assuming a non-response rate of approximately 20%, we decided to target 500 students from four public and four private schools. A total of 456 students participated in our study.

Participants

Inclusion criteria.

From the eight schools which provided admin consent to conduct the study, students enrolled in grade 8, 9, or 10 were invited to take part in the study. Following consent from the parents and assent from the student, he or she was included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Any student unable to understand or fill out the interview pro forma or questionnaire independently.

Data Sources and Measurement

Data was collected through a one on one interaction between each student and the data collector individually. The following tools were used.

Demographic pro forma ( Supplementary Datasheet 1 )

A brief and simple pro forma was structured to address all demographic related variables needed for the study.

Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) ( Supplementary Datasheet 2 )

The original version of the Parental Bonding Instrument ( Parker et al., 1979 ), previously validated for internal consistency, convergent validity, satisfactory construct, and independence from mood effects in several different populations, including Turkish and Chinese ( Parker et al., 1979 ; Parker, 1983 , 1990 ; Cavedo and Parker, 1994 ; Dudley and Wisbey, 2000 ; Wilhelm et al., 2005 ; Murphy et al., 2010 ; Liu et al., 2011 ; Behzadi and Parker, 2015 ), was employed in our study. This tool, composed of 25 questions, assesses parenting styles as two independent measures of “care” and “control” as perceived by the child. It is filled out separately for the father and the mother. It is available online for use without copyright. The use of PBI has been validated for British Pakistanis ( Mujtaba and Furnham, 2001 ) and Pakistani women ( Qadir et al., 2005 ). A paper by Qadir et al. on the validity of PBI for Pakistani women, reports the Cronbach alpha scores to be 0.91 and 0.80 for the “care” and “overprotection” scales, respectively ( Qadir et al., 2005 ).

The demographic pro forma and the parental bonding index were translated into Urdu by an individual fluent in both languages and validated with the help of an epidemiologist and two experts in the field ( Supplementary Datasheet 3 ). Pilot testing of translated versions was done with 20 students to ensure clarity and assess understanding and comprehension by the students. Both versions for the two tools were provided in hard copy to each student to fill out whichever one he/she preferred. The data collector first verbally explained the items on the demographic pro forma and the PBI to the student following which the student was allowed to fill it out independently.

Using the data sources mentioned above, data was collected for the following variables.

Student Related

Gender, type of school (public or private), class grade (8th, 9th, and 10th) and academic performance.

In Pakistan, public and private schools may differ in several aspects including fee structures, class strength and difficulty levels of internal examinations, with private schools being more expensive, with fewer students per classroom, and subjectively tougher internal examinations.

The academic performance was judged as the overall grade (a combination of all subjects including English, Mathematics and Science) in the latest internal examinations sat by the student as A+, A, B, C, or D.

Family Related

Family structure and type of accommodation (rented or owned).

Parent Related

Information on living status, education level, employment status, employment type and parenting styles was obtained from the student separately for the father and mother.

Quantitative Variables

Academic performance.

The grades A+, A were categorized as “high” grades and grades B, C, and D were categorized as “low” grades.

Socio-Economic Status

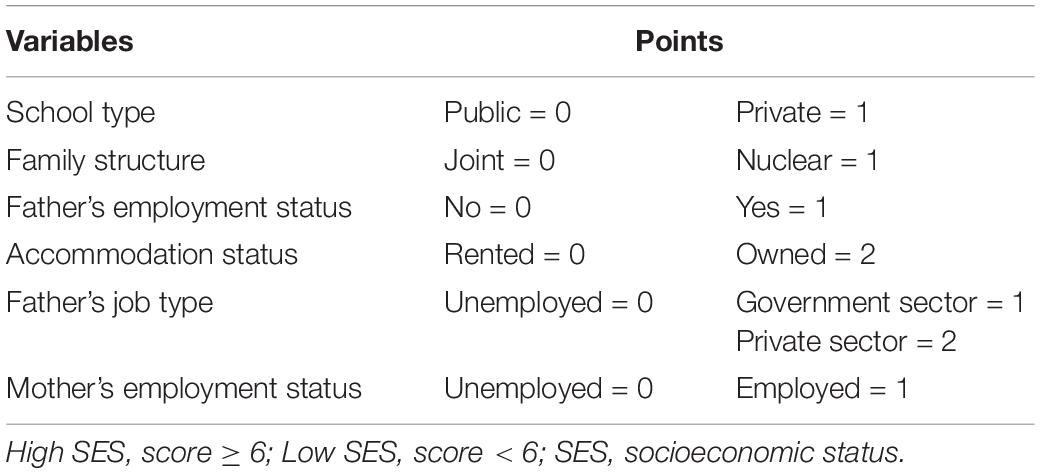

We used variables which adolescent students are expected to have knowledge of to calculate a score which categorized students as belonging to either a high or low socioeconomic status. The points assigned to each variable are show in Table 1 .

Table 1. Calculation of an estimated socioeconomic status.

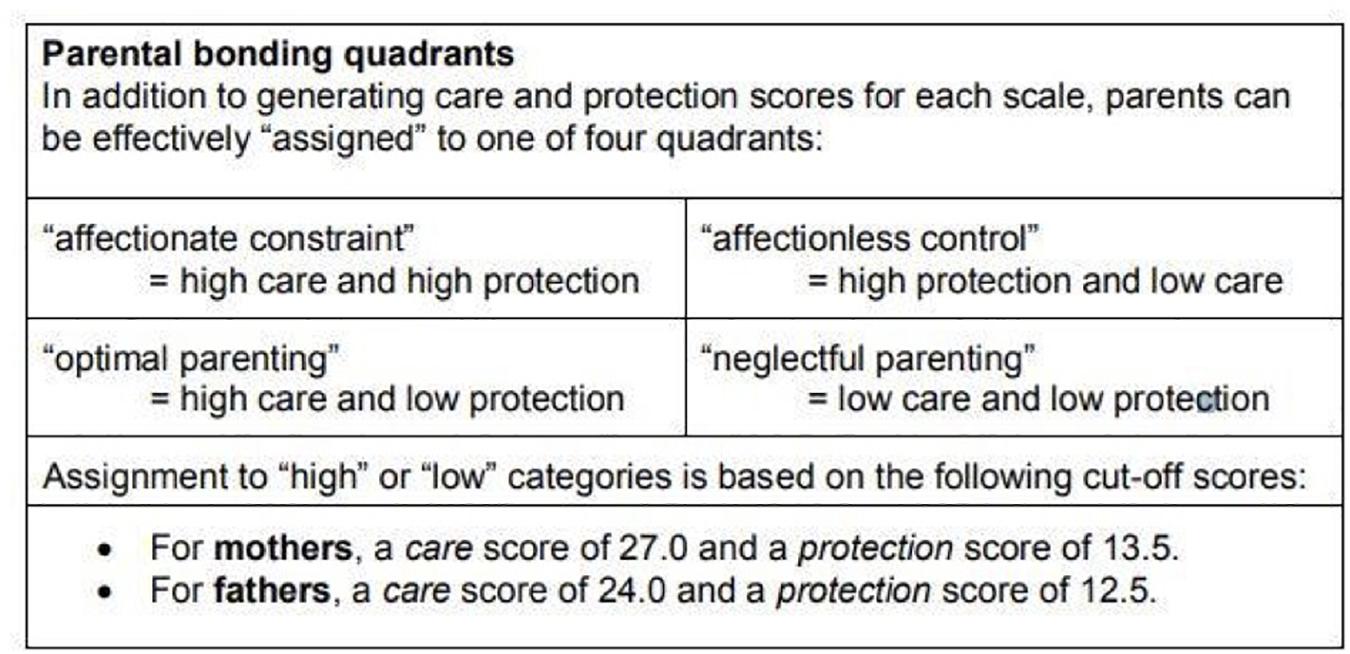

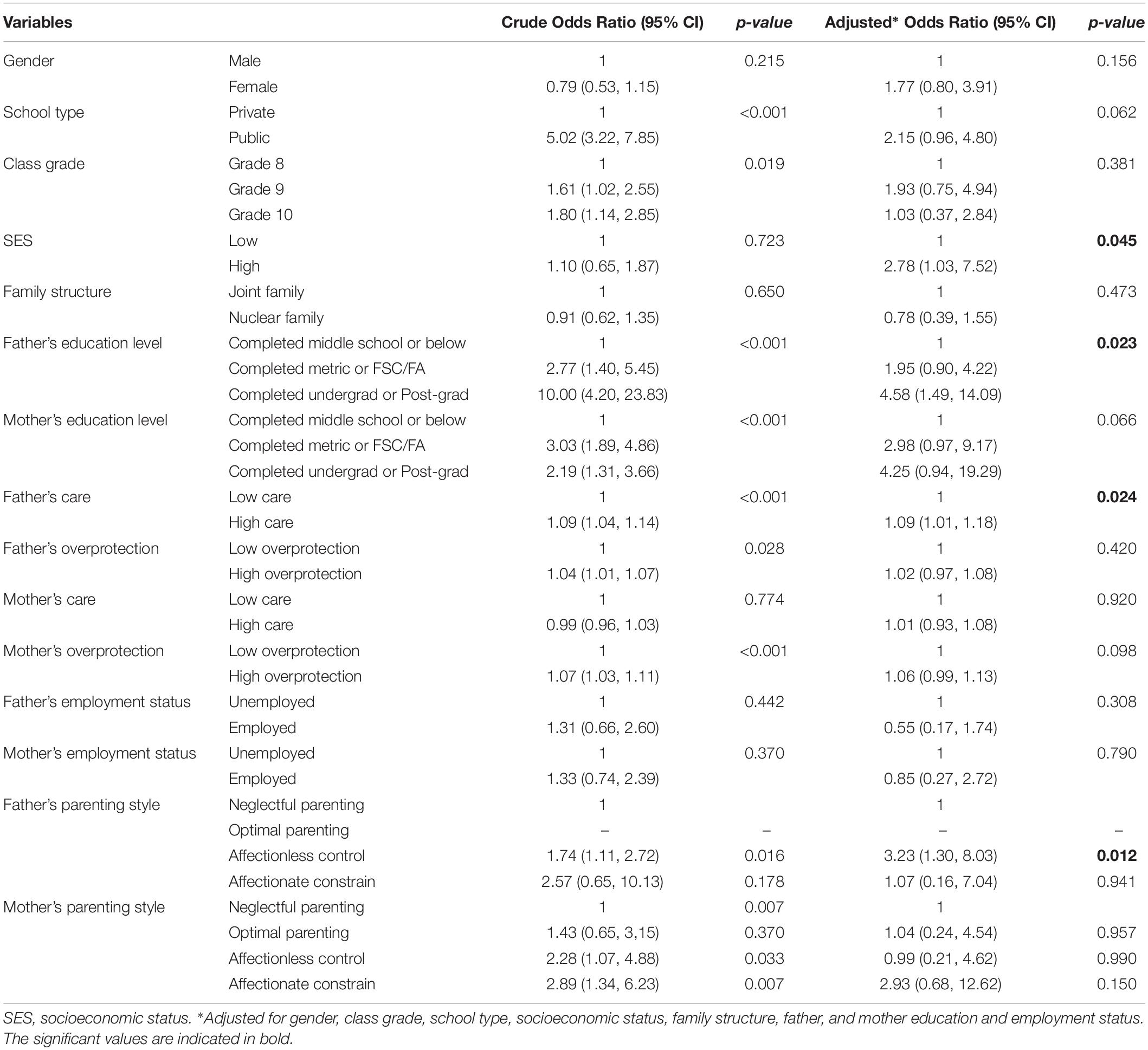

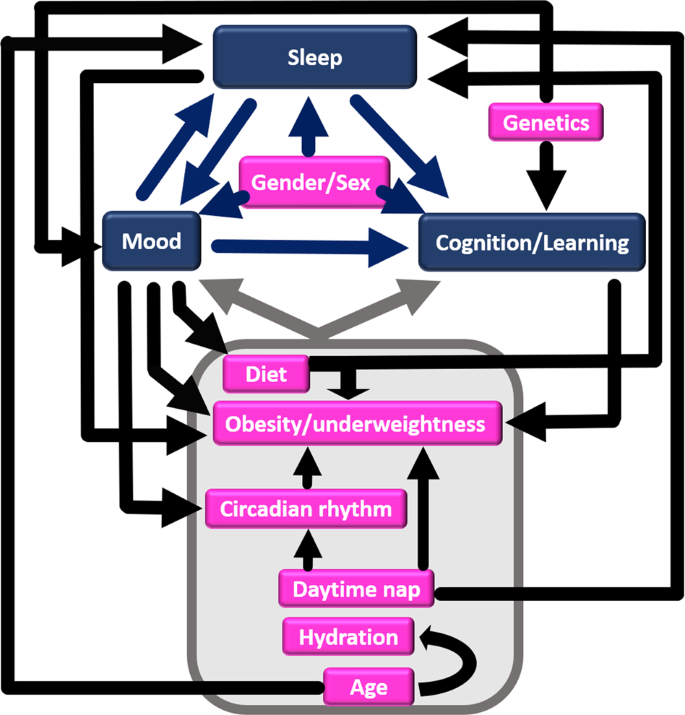

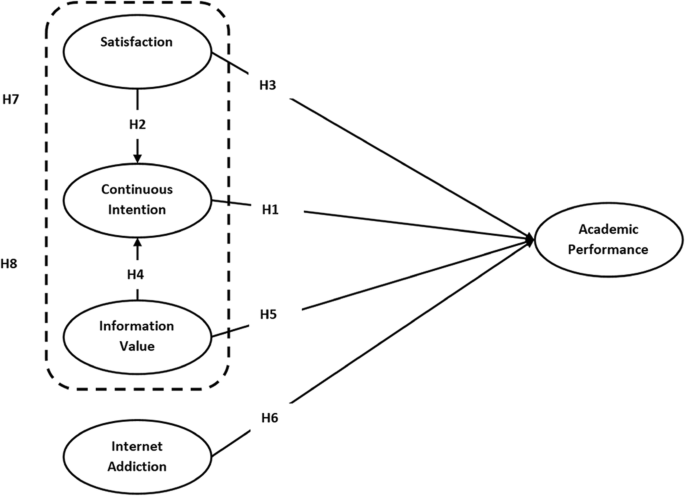

Parenting Styles

The PBI is a 25 item questionnaire, with 12 items measuring “care” and 13 items measuring “overprotection.” All responses have a 4 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very unlikely) to 3 (very likely). The responses are summed up to categorize each parent to exhibit low or high “care” and low or high “overprotection.” Based on these findings, each parent can then be put into one of the 4 quadrants representing parenting styles including “affectionate constraint,” “affectionless control,” “optimal parenting,” and “neglectful parenting.” This computation is explained in Figure 1 obtained from the information provided with the PBI ( Parker et al., 1979 ).

Figure 1. Assigining parenting styles using the PBI ( Parker, 1979 #192).

Students were allowed to fill in the pro forma and questionnaire independently to avoid bias during the data collection process. However, self-reporting of grades in latest examination may be subject to recall bias.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive analyses were conducted on all study variables including socio-demographic factors and parenting styles. Categorical variables were reported as proportions and continuous variables as measures of central tendency. All continuous variables were subjected to a normality test. Mean and median values were reported for variables with normally distributed and skewed data, respectively.

The summary t -test was used to study the differences between mean “care” and “overprotection” scores of fathers and mothers. The independent sample t -test was used to study the factors associated with “care” and “overprotection” scores of fathers and mothers. Threshold for significance was p = 0.05.

The determinants of high grades including the influence of parenting styles were assessed using regression analysis. The outcome variable, student grades, was treated as binary (high grades and low grades). The threshold for statistical significance was p = 0.05. Crude Odds Ratios were adjusted for gender, school type, socioeconomic status, family structure, class grade, parents’ employments and education status.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Khyber Medical University, Advance Studies and Research Board (KMU-AS&RB) in August 2016. Identifying information of students was not obtained. Permissions were obtained from the relevant authorities in the school administration before approaching the students and their parents. Written consent was obtained from the parents through the home-work diary of the students and verbal assent of each student was obtained.

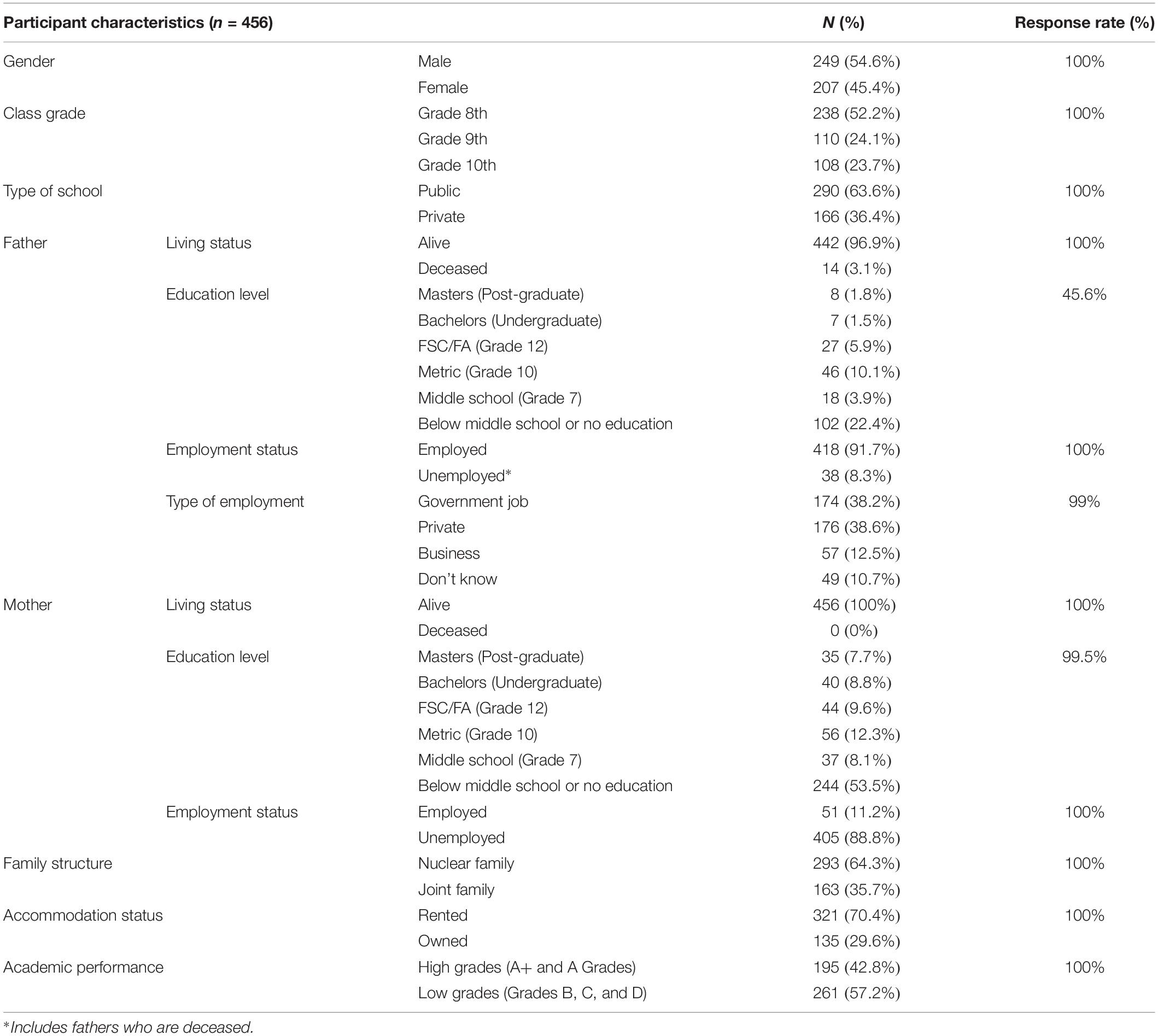

Participants and Descriptive Data

A total of 456 students were interviewed, with 249 (54.6%) males and 207 (45.4%) females. The majority (52.5%) were students of grade 8. Despite including an equal number of public and private schools, 63.6% of the students belonged to a public sector school. The reason may be due to the larger class strength in public schools in comparison to private schools. The nuclear family structure was dominant (64.3%), with most students living in rented accommodation (70.4%) with 42.8% reporting to have obtained high grades (A plus or A) in their latest internal examinations ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Participant and descriptive data.

Majority of the students had both parents alive at the time of the interview. While all students’ mothers were alive, 14 students reported their father to have passed away. Surprisingly, only 46% of the students were able to report their father’s level of education compared to 99.5% for their mother. 9.2% of students reported their father to have an education level of grade 12 or above compared to 26% regarding their mother’s qualification. This was in contrast to 90% of the fathers being employed compared to only 11% of the mothers ( Table 2 ).

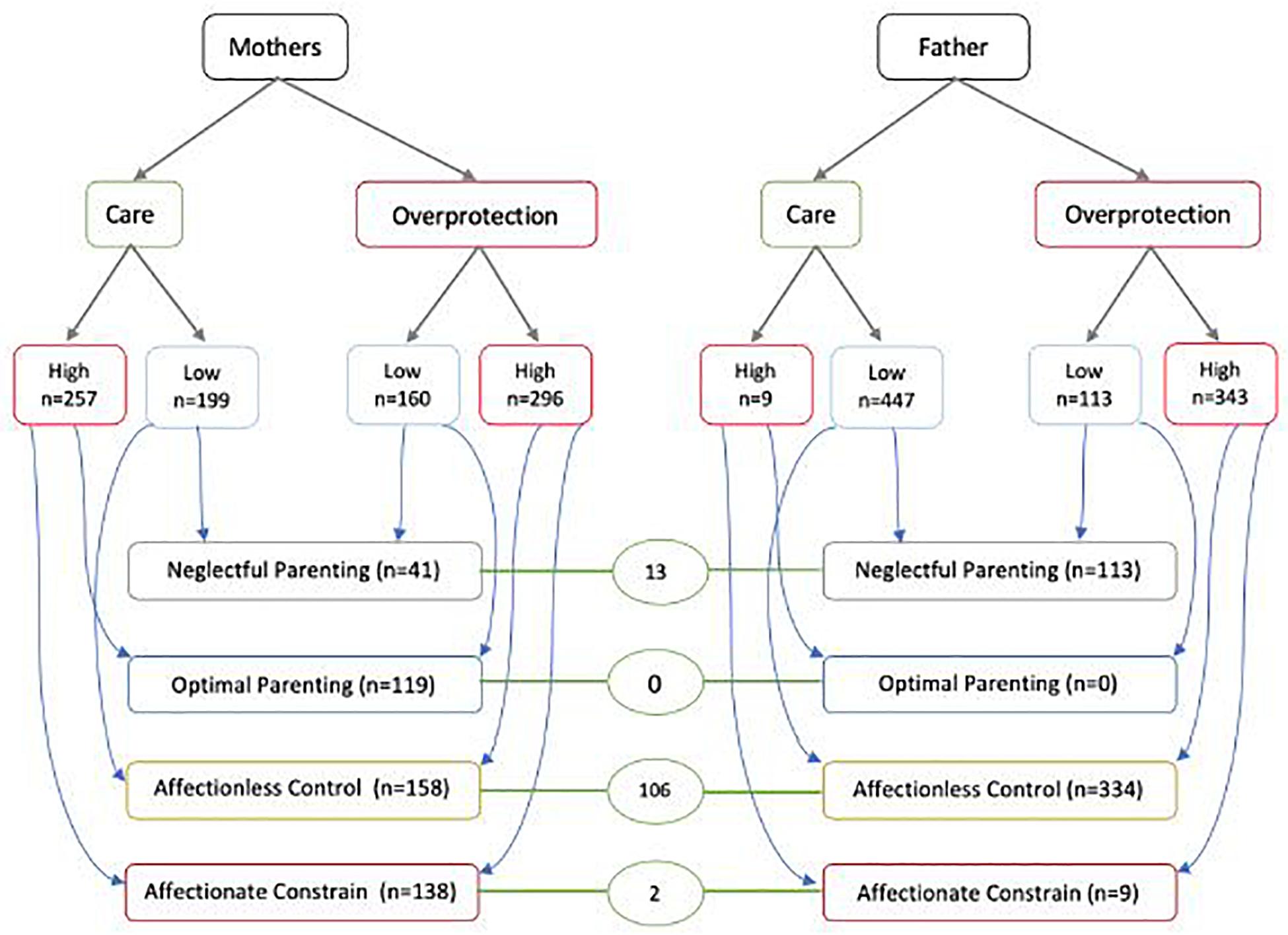

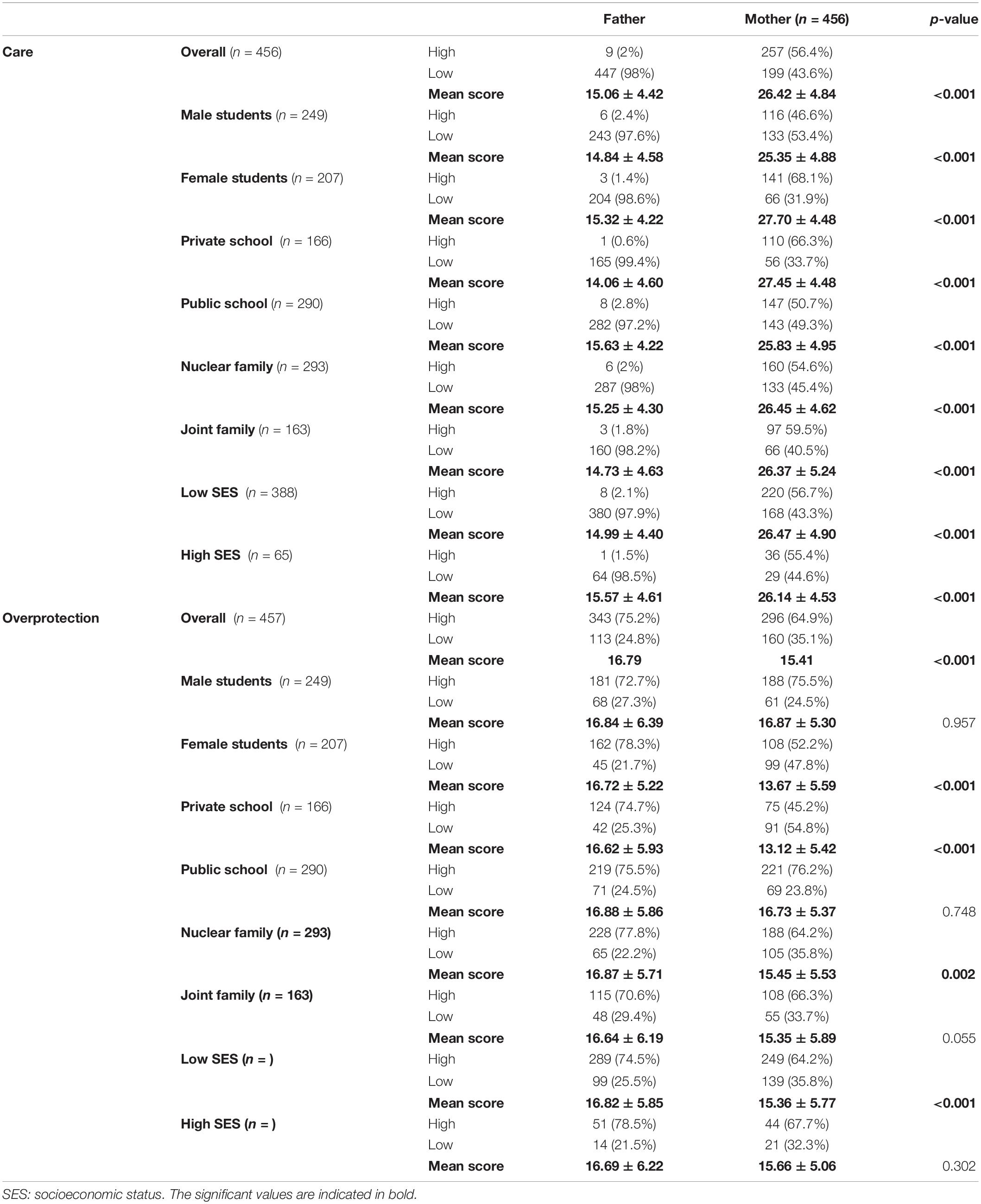

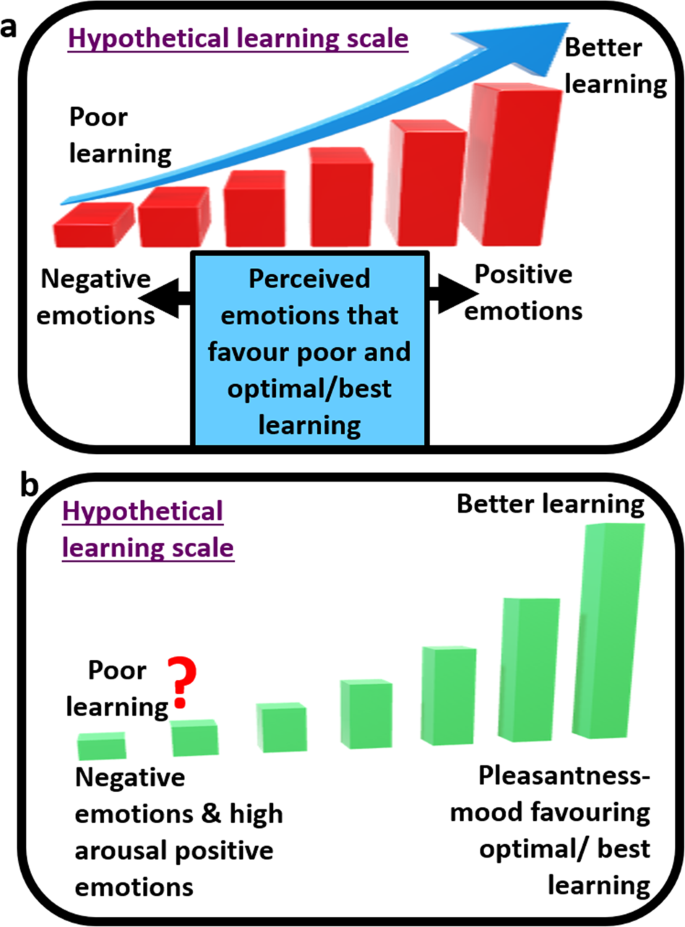

A Total of 257 (56%) students reported their mother to exhibit a high level of “care” vs. only 9 (2%) students reporting the same for their father. In terms of “overprotection,” 343 (75%) and 296 (65%) students reported a high level for their father and mother, respectively. Based on combinations of these measures, the most common parenting style for both fathers (73%) and mothers (35%) was affectionless control and the least common for fathers was optimal parenting (0%) and neglectful parenting for mothers (9%). 121 (26%) students had both parents with the same parenting style, with 23% students having both parents show affectionless control and not a single student with both parents showing optimal parenting ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2. “Care,” “overprotection” and parenting styles for fathers and mothers as reported by students ( n = 456). Green circles represent students with both parents showing the same parenting style – none of the students received “Optimal parenting” from both parents while 106 students received affectionless control from both parents.

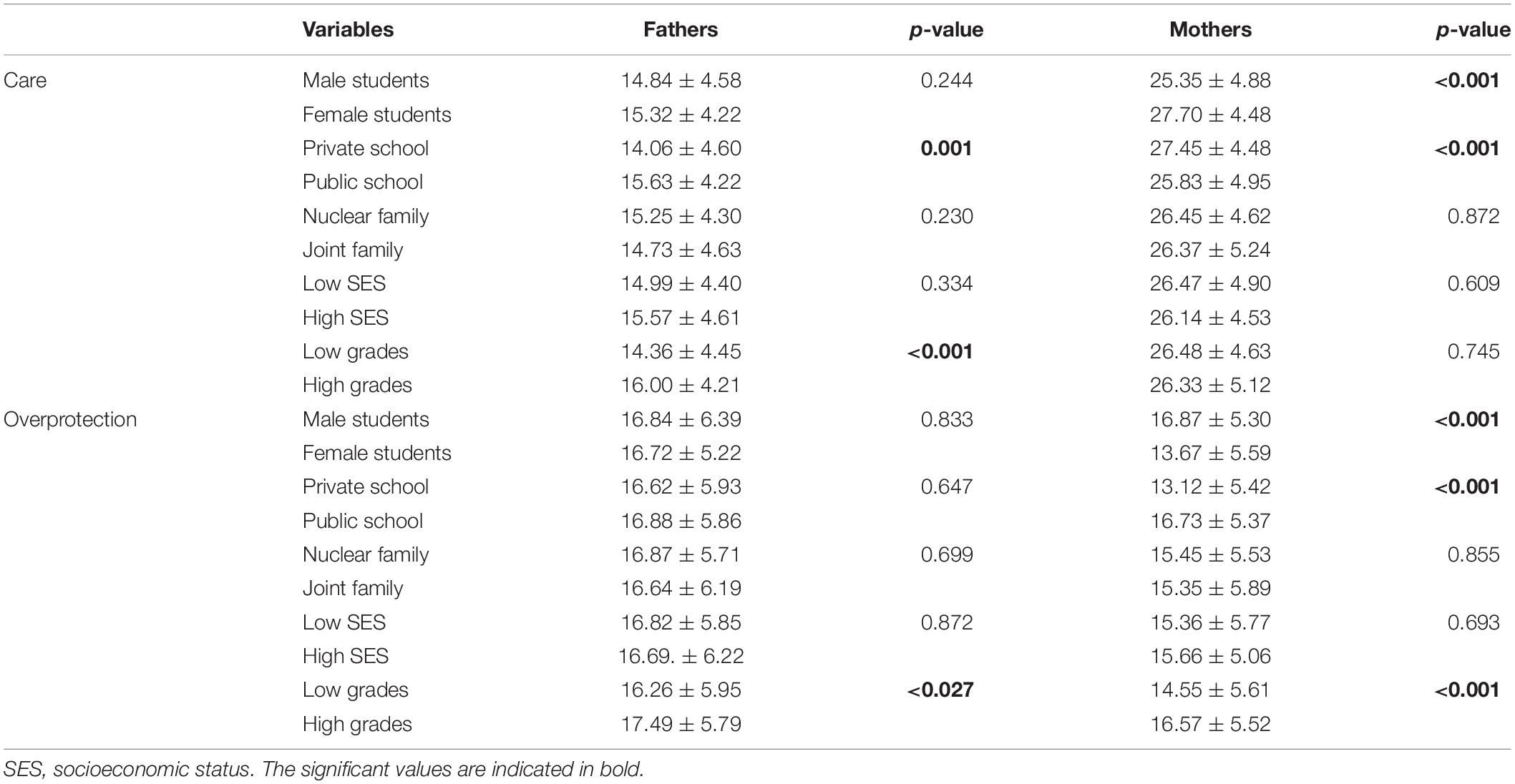

Determinants of High Grades

Our results show that high socioeconomic status [adjusted OR 2.78 (1.03, 7.52)], father’s education level till undergrad or above [adjusted OR 4.58 (1.49, 14.09)], father’s high “care” [adjusted OR 1.09 (1.01, 1.18)] and father’s affectionless control style of parenting [adjusted OR 3.23 (1.30, 8.03)] are significant factors contributing to high grades ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Academic performance: Determinants of “high” grades in the latest internal examinations.

Differences in “Care” and “Overprotection” Between Fathers and Mothers

The mean “care” score for mothers were significantly higher than fathers overall. The difference remained significant for male and female students, public and private schools, joint and nuclear family structures and low and high socioeconomic statuses ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Differences between mean “care” and “overprotection” scores between fathers and mothers.

Overprotection

The mean “overprotection” score was significantly higher for fathers overall. The difference remained significant for female students, private schools, nuclear family structure, and low socioeconomic status. However, there was no significant difference in mean “overprotection” scores between fathers and mothers for male students, public schools, joint family structures and high socioeconomic status ( Table 4 ).

Factors Associated With “Care” and “Overprotection” in Fathers and Mothers

The mean “care” score was significantly higher for fathers as reported by children in public schools and with higher grades. There was no significant difference in mean care scores based on student gender, socioeconomic status or family structure ( Table 5 ).

Table 5. Factors associated with “care” and “overprotection” for mothers and fathers.

For “overprotection” the only factor associated with a significantly higher mean score was “high” grades ( Table 5 ).

A significantly higher mean “care” score for mothers was reported by female students and students in public schools. No significant differences were observed for the other factors ( Table 5 ).

A significantly higher mean “overprotection” score was reported by male students, students in public schools and those with “high” grades for mothers ( Table 5 ).

Summary of Findings

Results of regression analysis show that socioeconomic status, father’s education level and fathers’ care scores have a significantly positive influence on the academic performance of adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. The most common parenting style for both fathers and mothers was affectionless control. However, affectionless control exhibited by the father was the only parenting style significantly contributing to improved academic performance.

Overall, the mean “care” score was higher for mothers and the mean “overprotection” score was higher for fathers. However, differences in “overprotection” were eliminated for male students, public schooling, joint family structures and high socioeconomic status.

Public schooling was associated with a significantly higher mean “care” score for both fathers and mothers and a significantly higher mean “overprotection” score for mothers. High grades were associated with a significantly higher mean “overprotection” score for both fathers and mothers and a significantly higher mean “care” score for fathers. For mothers, female students reported a significantly higher mean care score and male students reported a significantly higher mean “overprotection” score.

An additional interesting finding from the results of the study was that only about half the students were able to report their father’s level of education compared to almost a 100% for their mother. From amongst those who did report, less than 10% of the father’s had an education level equal or above grade 12 compared to a quarter of the mothers. However, only 11% of the mothers were employed in contrast to 90% of the fathers.

Previous Literature and Comparison of Main Findings

The results of our study have identified socioeconomic status, father’s education level and high care scores for fathers to be significant predictors of academic success in adolescent students. Previous literature has shown socioeconomic status to be a predictor of academic success ( Gamoran, 1996 ; Sander, 1999 ; Lubienski and Lubienski, 2006 ).

Parental education has been frequently associated with improved academic performance ( Dumka et al., 2008 ; Dubow et al., 2009 ; Masud et al., 2015 ). In 2011, a study by Farooq et al. described the factors affecting academic performance in 600 students at the secondary school level in a public school in Lahore, Pakistan. Results of their study also associate parental education level with academic success in students. However, their results are significant for the education level of the mother as well as the father. Additionally, they also reported significantly higher academic performance in females and in students belonging to a higher socioeconomic status, factors not significant in our study ( Farooq et al., 2011 ). Differences may be explained by cultural variations in Lahore and Peshawar within Pakistan, which should be explored further.

The description of parenting styles and behaviors has evolved over the years. With some variation in terminologies, the essence lies in a few common principles. Diana Baumrind initially described three main parenting styles based on variations in normal parenting behaviors: authoritative, authoritarian and permissive ( Baumrind, 1966 , 1967 ). Building on the concepts put forth by Baumrind, Maccoby and Martin identified two dimensions, “responsiveness” and “demandingness,” which could classify parenting styles into 4 types, three of those described by Baumrind with the addition of neglectful parenting ( Maccoby et al., 1983 ). The two dimensions, “responsiveness” and “demandingness,” often referred to as “warmth” and “control” in literature ( Lamborn et al., 1991 ; Tagliabue et al., 2014 ), are similar to the two measures, “care” and “overprotection” assessed by the parental bonding instrument ( Parker et al., 1979 ; Parker, 1989 ; Dudley and Wisbey, 2000 ). Based on this, the authoritative, authoritarian, permissive and neglectful parenting styles described by Baumrind and Maccoby are similar to the affectionate constraint, affectionless control, optimal, and neglectful styles as classified by the parental bonding instrument, respectively ( Baumrind, 1991 ; Cavedo and Parker, 1994 ).

Results of our study show that affectionless control, similar to the authoritarian style of parenting, adapted by the father is significantly associated with improved academic performance. This differs from the popularity of the authoritative parenting style, similar to affectionate constraint, in determining academic success in literature from western cultures ( Steinberg et al., 1989 , 1992 ; Deslandes et al., 1998 ; Aunola et al., 2000 ; Adeyemo, 2005 ; Masud et al., 2015 ; Pinquart, 2016 ; Checa et al., 2019 ). Evidence from societies with cultural similarities with Pakistan presents varied findings. A study from Iran shows support for the authoritarian parenting style similar to our study ( Rahimpour et al., 2015 ). A review of 39 studies published by Masud et al. (2015) in 2015 assesses the effect of parenting styles on academic performance ( Masud et al., 2015 #205). The review very aptly described how the authoritative parenting style is the dominant and most effective style in terms of determining academic performance in the West and European countries while Asian cultures show more promising results for academic success for the authoritarian style ( Dornbusch et al., 1987 ; Lin and Fu, 1990 ; Masud et al., 2015 ). The results of our study are in synchrony with these findings. However, our results also show that high father’s “care” scores are significant contributors to higher academic grades. Since no father showed optimal parenting and only 9 fathers had affectionate constraint, both parenting styles with high care scores, these results may be a reflection of the importance of father’s role in determining academic performance in Asian cultures. Findings supporting the authoritarian/affectionless control style may be due to the abundance of this parenting style. Perhaps a fairer comparison may be possible with a larger sample population with fathers showing all types of parenting styles equally.

Interpretation and Explanation of Other Findings

Observations of factors associated with and differences in “care” and “overprotection” between fathers and mothers may be attributed to reverse causality and should be used as hypothesis generating.

Our results show that mothers have higher mean “care” score and fathers have a higher mean “overprotection” score. Since these scores are based on perceptions of the child, part of these observations may be explained by the cultural norms of expression of love and concern by fathers and mothers. With the difference in “overprotection” being eliminated for male and female children, it is possible that mothers are more overprotective of their sons. Male gender preference in Pakistan may be an explanation for this ( Qadir et al., 2011 ).

Our results show lower employment rates for women despite higher education levels. The finding of higher education levels for females compared to males does not agree with national data, which reports findings from rural areas as well where education opportunities are limited for females ( Hussain, 2005 ; Chaudhry and Rahman, 2009 ). Our results provide a zoomed in look at an urban population, which may have progressed enough to improve women’s education but cultural norms, gender discrimination and lack of opportunity still prevent women from stepping into the workface ( Chaudhry, 2007 ; Begum and Sheikh, 2011 ).

Implications and Future Direction

The findings of our study may have implications for future research and policy making.

Affectionless control is associated with improved academic performance but further research investigating the effects of this style on other aspects of child development, particularly emotional and psychological health, is needed. Factors affecting care and overprotection need to be studied in more detail so that parenting workshops and interventions are tailored to our population. Results also suggest that fathers should play a stronger role in parenting of adolescent students. School policies should make it mandatory for both parents to attend parent-teacher meetings and assigned home activities should include both parents.

Limitations

Since the study is based on the urban population of Peshawar, results may not be generalizable to the adolescent students of the country which includes large rural populations. Academic performance was judged on latest internal examinations, the marking criteria for which may vary across schools. The use of external examinations would have standardized grades across schools but limited the sample to students of grade 9 and 10.

Our study concludes that socioeconomic status, father’s level of education and high care scores for fathers are associated with improved academic outcomes in adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. Affectionless control is the most common parenting style as perceived by the students and when adapted by the father, contributes to better grades. Further research investigating the effects of demonstrating affectionless control on the emotional and psychological health of students needs to be conducted. Parenting workshops and school policies should include recommendations to increase involvement of fathers in the parenting of adolescent children.

Data Availability Statement

Data collected and stored as part of this study is available upon reasonable request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Khyber Medical University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

SM contributed in conceiving, designing, data acquisition, grant submission, and manuscript review. SHM involved in data analysis and manuscript writing. NQ involved in manuscript writing. MK was the principal investigator and supervisor for the project. FK and SK contributed in literature review and data management. All authors proofread and agreed on the final draft and accept responsibility for the work.

This project was graciously funded by the Research Promotion and Development World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (RPPH Grant 2016-2017, TSA reference: 2017/719467-0).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nazish Masud (King Saud bin Abdulaziz University), and Dr. Khabir Ahmad and Dr. Bilal Ahmad (The Aga Khan University) for their contributions to the project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02497/full#supplementary-material

Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 21, 407–412. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Adeyemo, D. A. (2005). Parental involvement, interest in schooling and school environment as predictors of academic self-efficacy among fresh secondary school students in Oyo State, Nigeria. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 3, 163–180.

Google Scholar

Aunola, K., Stattin, H., and Nurmi, J.-E. (2000). Parenting styles and adolescents’ achievement strategies. J. Adolesc. 23, 205–222. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0308

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Battle, J. (2002). Longitudinal analysis of academic achievement amonga nationwide sample of hispanic students in one-versus dual-parent households. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 24, 430–447. doi: 10.1177/0739986302238213

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Dev. 37, 887–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1966.tb05416.x

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 75, 43–88.

Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J. Early Adolesc. 11, 56–95. doi: 10.1177/0272431691111004

Bean, R. A., Barber, B. K., and Crane, D. R. (2006). Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth: the relationships to academic grades, delinquency, and depression. J. Fam. Issues 27, 1335–1355. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06289649

Beauvais, A. M., Stewart, J. G., DeNisco, S., and Beauvais, J. E. (2014). Factors related to academic success among nursing students: a descriptive correlational research study. Nurse Educ. Today 34, 918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.005

Begum, M. S., and Sheikh, Q. A. (2011). Employment situation of women in Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 38, 98–113. doi: 10.1108/03068291111091981

Behzadi, B., and Parker, G. (2015). A Persian version of the parental bonding instrument: factor structure and psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 225, 580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.042

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev. 55, 83–96. doi: 10.2307/1129836

Bluestone, C., and Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (1999). Correlates of parenting styles in predominantly working- and middle-class African American mothers. J. Marriage Fam. 61, 881–893. doi: 10.2307/354010

Cavedo, L., and Parker, G. (1994). Parental bonding instrument. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 29, 78–82.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Chaudhry, I. S. (2007). Gender inequality in education and economic growth: case study of Pakistan. Pakistan Horizon 60, 81–91.

Chaudhry, I. S., and Rahman, S. (2009). The impact of gender inequality in education on rural poverty in Pakistan: an empirical analysis. Eur. J. Econ. Finance Adm. Sci. 15, 174–188.

Checa, P., and Abundis-Gutierrez, A. (2017). Parenting and temperament influence on school success in 9–13 year olds. Front. Psychol. 8:543. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00543

Checa, P., Abundis-Gutierrez, A., Pérez-Dueñas, C., and Fernández-Parra, A. (2019). Influence of maternal and paternal parenting style and behavior problems on academic outcomes in primary school. Front. Psychol. 10:378. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00378

Chow, H. P. (2000). The determinants of academic performance: Hong Kong immigrant students in Canadian schools. Can. Ethn. Stud. J. 32, 105–105.

Cohen, D. A., and Rice, J. (1997). Parenting styles, adolescent substance use, and academic achievement. J. Drug Educ. 27, 199–211. doi: 10.2190/QPQQ-6Q1GUF7D-5UTJ

Cutrona, C. E., Cole, V., Colangelo, N., Assouline, S. G., and Russell, D. W. (1994). Perceived parental social support and academic achievement: an attachment theory perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 66, 369–378. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.369

Dennis, J. M., Phinney, J. S., and Chuateco, L. I. (2005). The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 46, 223–236. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0023

Desimone, L. (1999). Linking parent involvement with student achievement: do race and income matter? J. Educ. Res. 93, 11–30. doi: 10.1080/00220679909597625

Deslandes, R., Bouchard, P., and St-Amant, J.-C. (1998). Family variables as predictors of school achievement: sex differences in Quebec adolescents. Can. J. Educ. 23, 390–404.

Deslandes, R., Royer, E., Turcotte, D., and Bertrand, R. (1997). School achievement at the secondary level: influence of parenting style and parent involvement in schooling. McGill J. Educ. 32

Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F., and Fraleigh, M. J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Dev. 58, 1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x

Dubow, E. F., Boxer, P., and Huesmann, L. R. (2009). Long-term effects of parents’ education on children’s educational and occupational success: mediation by family interactions, child aggression, and teenage aspirations. Merrill Palmer Q. 55, 224–249. doi: 10.1353/mpq.0.0030

Dudley, R. L., and Wisbey, R. L. (2000). The relationship of parenting styles to commitment to the church among young adults. Relig. Educ. 95, 38–50. doi: 10.1080/0034408000950105

Dumka, L. E., Gonzales, N. A., Bonds, D. D., and Millsap, R. E. (2008). Academic success of Mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: the role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles 60, 588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z

Farooq, M. S., Chaudhry, A. H., Shafiq, M., and Berhanu, G. (2011). Factors affecting students’ quality of academic performance: a case of secondary school level. J. Qual. Technol. Manag. 7, 1–14.

Farsides, T., and Woodfield, R. (2003). Individual differences and undergraduate academic success: the roles of personality, intelligence, and application. Pers. Individ. Differ. 34, 1225–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00111-3

Flynn, D. M., and MacLeod, S. (2015). Determinants of Happiness in Undergraduate University Students. Coll. Stud. J. 49, 452–460.

Gamoran, A. (1996). Student achievement in public magnet, public comprehensive, and private city high schools. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 18, 1–18. doi: 10.3102/01623737018001001

Ginsburg, G. S., and Bronstein, P. (1993). Family factors related to children’s intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance. Child Dev. 64, 1461–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02964.x

Hawkins, J. D. (1997). “Academic performance and school success: sources and consequences,” in Healthy Children 2010: Enhancing Children’s Wellness , eds R. P. Weissberg, T. P. Gullotta, R. L. Hampton, B. A. Ryan, and G. R. Adams, (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc), 278–305.

Hillstrom, K. A. (2009). Are Acculturation and Parenting Styles Related to Academic Achievement Among Latino students? dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Hussain, I. (2005). “Education, employment and economic development in Pakistan,” in Education Reform in Pakistan: Building for the Future , ed. R. M. Hathaway, (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars), 33–45.

Huver, R. M. E., Otten, R., de Vries, H., and Engels, R. C. (2010). Personality and parenting style in parents of adolescents. J. Adolesc. 33, 395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.012

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Urban Educ. 42, 82–110. doi: 10.1177/0042085906293818

Khalid, A., Qadir, F., Chan, S. W., and Schwannauer, M. (2018). Parental bonding and adolescents’ depressive and anxious symptoms in Pakistan. J. Affect. Disord. 228, 60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.050

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J. L., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., and Hayek, J. C. (2006). What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature. Washington, DC: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., and Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 62, 1049–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x

Lin, C. Y. C., and Fu, V. R. (1990). A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. Child Dev. 61, 429–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02789.x

Linnenbrink, E. A., and Pintrich, P. R. (2002). Motivation as an enabler for academic success. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 31, 313–327. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2018.1471169

Liu, J., Li, L., and Fang, F. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Parental Bonding Instrument. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 48, 582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.008

Lubienski, C., and Lubienski, S. (2006). Charter, Private, Public Schools and Academic Achievement: New Evidence from NAEP Mathematics Data. New York, NY: Columbia University.

Maccoby, E., Martin, J., Hetherington, E., and Mussen, P. (1983). “Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction,” in Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality, and Social Development , 4th Edn, Vol. 4, ed. E. M. Hetherington, (Hoboken. NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 101.

Masud, H., Thurasamy, R., and Ahmad, M. S. (2015). Parenting styles and academic achievement of young adolescents: a systematic literature review. Qual. Quant. 49, 2411–2433. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-0120-x

McCabe, J. E. (2014). Maternal personality and psychopathology as determinants of parenting behavior: a quantitative integration of two parenting literatures. Psychol. Bull. 140, 722–750. doi: 10.1037/a0034835

McClelland, M. M., Morrison, F. J., and Holmes, D. L. (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: the role of learning-related social skills. Early Child. Res. Q. 15, 307–329. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00069-7

Mujtaba, T., and Furnham, A. (2001). A cross-cultural study of parental conflict and eating disorders in a non-clinical sample. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 47, 24–35. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700103

Murphy, E., Wickramaratne, P., and Weissman, M. (2010). The stability of parental bonding reports: a 20-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 125, 307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.003

Osorio, A., and González-Cámara, M. (2016). Testing the alleged superiority of the indulgent parenting style among Spanish adolescents. Psicothema 28, 414–420.

Östberg, M., and Hagekull, B. (2000). A structural modeling approach to the understanding of parenting stress. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 29, 615–625. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_13

Parker, G. (1979). Reported parental characteristics in relation to trait depression and anxiety levels in a non-clinical group. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 13, 260–264. doi: 10.3109/00048677909159146

Parker, G. (1983). Parental Overprotection: A Risk Factor in Psychosocial Development. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton.

Parker, G. (1989). The parental bonding instrument: psychometric properties reviewed. Psychiatr. Dev. 7, 317–335.

Parker, G. (1990). The parental bonding instrument. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 25, 281–282.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., and Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 52, 1–10.

Parsasirat, Z., Montazeri, M., Yusooff, F., Subhi, N., and Nen, S. (2013). The most effective kinds of parents on children’s academic achievement. Asian Soc. Sci. 9, 229–242.

Pinquart, M. (2016). Associations of parenting styles and dimensions with academic achievement in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 475–493. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9338-y

Ponnet, K., Mortelmans, D., Wouters, E., Van Leeuwen, K., Bastaits, K., and Pasteels, I. (2013). Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Pers. Relat. 20, 259–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.x

Qadir, F., Khan, M. M., Medhin, G., and Prince, M. (2011). Male gender preference, female gender disadvantage as risk factors for psychological morbidity in Pakistani women of childbearing age - a life course perspective. BMC Public Health 11:745. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-745

Qadir, F., Stewart, R., Khan, M., and Prince, M. (2005). The validity of the Parental Bonding Instrument as a measure of maternal bonding among young Pakistani women. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 40, 276–282. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0887-0

Rahimpour, P., Direkvand-Moghadam, A., Direkvand-Moghadam, A., and Hashemian, A. (2015). Relationship between the parenting styles and students’ educational performance among Iranian girl high school students, a cross- sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9:JC05–JC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15981.6914

Sander, W. (1999). Private schools and public school achievement. J. Hum. Resour. 34, 697–709. doi: 10.2307/146413

Sanders, M. G. (1998). The effects of school, family, and community support on the academic achievement of African American adolescents. Urban Educ. 33, 385–409. doi: 10.1177/0042085998033003005

Shute, V. J., Hansen, E. G., Underwood, J. S., and Razzouk, R. (2011). A review of the relationship between parental involvement and secondary school students’ academic achievement. Educ. Res. Int. 2011:915326.

Simons, R. L., Beaman, J., Conger, R. D., and Chao, W. (1993). Childhood experience, conceptions of parenting, and attitudes of spouse as determinants of parental behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 55, 91–106. doi: 10.2307/352961

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Conger, R. D., and Melby, J. N. (1990). Husband and wife differences in determinants of parenting: a social learning and exchange model of parental behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 52, 375–392. doi: 10.2307/353033

Smith, C. L. (2010). Multiple determinants of parenting: predicting individual differences in maternal parenting behavior with toddlers. Parenting 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/15295190903014588

Steinberg, L., Elmen, J. D., and Mounts, N. S. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Dev. 60, 1424–1436. doi: 10.2307/1130932

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., and Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev. 63, 1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x

Tagliabue, S., Olivari, M. G., Bacchini, D., Affuso, G., and Confalonieri, E. (2014). Measuring adolescents’ perceptions of parenting style during childhood: psychometric properties of the parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire. Psicol. Teoria e Pesquisa 30, 251–258. doi: 10.1590/s0102-37722014000300002

Tomul, E., and Savasci, H. S. (2012). Socioeconomic determinants of academic achievement. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 24, 175–187. doi: 10.1007/s11092-012-9149-9143

Vacha, E. F., and McLaughlin, T. F. (1992). The social structural, family, school, and personal characteristics of at-risk students: policy recommendations for school personnel. J. Educ. 174, 9–25. doi: 10.1177/002205749217400303

Valiente, C., Lemery-Chalfant, K., and Castro, K. S. (2007). Children’s effortful control and academic competence: mediation through school liking. Merrill Palmer Q. 53, 1–25. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2007.0006

Vandenbroucke, J. P., von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., et al. (2014). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 12, 1500–1524.

Wang, Q., and Leichtman, M. D. (2000). Same beginnings, different stories: a comparison of American and Chinese children’s narratives. Child Dev. 71, 1329–1346. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00231

Weis, M., Trommsdorff, G., and Muñoz, L. (2016). Children’s self-regulation and school achievement in cultural contexts: the role of maternal restrictive control. Front. Psychol. 7:722. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00722

Weiss, L. H., and Schwarz, J. C. (1996). The relationship between parenting types and older adolescents’ personality, academic achievement, adjustment, and substance use. Child Dev. 67, 2101–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01846.x

Wilhelm, K., Niven, H., Parker, G., and Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2005). The stability of the parental bonding instrument over a 20-year period. Psychol. Med. 35, 387–393. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003538

York, T., Gibson, C., and Rankin, S. (2015). Defining and measuring academic success. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 20, 1–20.

Zahedani, Z. Z., Rezaee, R., Yazdani, Z., Bagheri, S., and Nabeiei, P. (2016). The influence of parenting style on academic achievement and career path. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 4, 130–134.

Zakeri, H., and Karimpour, M. (2011). Parenting styles and self-esteem. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 758–761. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.302

Zhang, X., Hu, B. Y., Ren, L., Huo, S., and Wang, M. (2019). Young Chinese children’s academic skill development: identifying child-, family-, and school-level factors. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2019, 9–37. doi: 10.1002/cad.20271

Keywords : parenting styles, academic performance, adolescent students, Pakistan, care, overprotection, parental bonding instrument

Citation: Masud S, Mufarrih SH, Qureshi NQ, Khan F, Khan S and Khan MN (2019) Academic Performance in Adolescent Students: The Role of Parenting Styles and Socio-Demographic Factors – A Cross Sectional Study From Peshawar, Pakistan. Front. Psychol. 10:2497. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02497

Received: 16 May 2019; Accepted: 22 October 2019; Published: 08 November 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Masud, Mufarrih, Qureshi, Khan, Khan and Khan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarwat Masud, [email protected] ; Muhammad Naseem Khan, [email protected] ; [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2022

Determinants of good academic performance among university students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study

- Mesfin Tadese 1 ,

- Alex Yeshaneh 2 &

- Getaneh Baye Mulu 3

BMC Medical Education volume 22 , Article number: 395 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

260k Accesses

26 Citations

Metrics details

Education plays a pivotal role in producing qualified human power that accelerates economic development and solves the real problems of a community. Students are also expected to spend much of their time on their education and need to graduate with good academic results. However, the trend of graduating students is not proportional to the trend of enrolled students and an increasing number of students commit readmission, suggesting that they did not perform well in their academics. Thus, the study aimed to identify the determinants of academic performance among university students in Southern Ethiopia.

Institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from December 1 to 28, 2020. A total of 659 students were enrolled and data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire. A multistage sampling technique was applied to select study participants. Data were cleaned and entered into Epi-Data version 4.6 and exported to SPSS version 25 software for analysis. Bivariable and multivariable data analysis were computed and a p -value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Smoking, age, and field of study were significantly associated with academic performance.

Four hundred six (66%) of students had a good academic performance. Students aged between 20 and 24 years (AOR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.22-0.91), and medical/ health faculty (AOR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.45-4.20) were significant associates of good academic performance. Students who didn’t smoke cigarettes were three times more likely to score good academic grades compared to those who smoke (AOR = 3.15, 95% CI = 1.21-7.30).

In this study, increased odds of good academic performance were observed among students reported to be non-smokers, adults, and medical/health science students. Reduction or discontinuation of smoking is of high importance for good academic achievement among these target groups. The academic environment in the class may be improved if older students are invited to share their views and particularly their ways of reasoning.

Peer Review reports

Higher education institutions play a pivotal role in producing qualified human power that enables solving the real problems of a community [ 1 ]. Education is a powerful agent of change that improves health and livelihoods and contributes to social stability. At the micro-level, it is associated with better living standards for individuals through improved productivity; given that those who have received a higher education tend to have more economic and social opportunities. At the macro level, education builds well-informed and skilled human capital, which has been considered an engine of economic growth, that positively contributes to economic development [ 2 ]. However, gaining knowledge, attitudes, values, and skills through education is not a simple task; rather it is a long and challenging trip in life. Students are expected to spend much of their time studying and need to graduate with good academic results.

Academic performance/ achievement is the extent to which a student, teacher, or institution has attained their short or long-term educational goals and is measured either by continuous assessment or cumulative grade point average (CGPA) [ 3 ]. A correlational study among vocational high school students in Indonesia found that students who had good academic achievements have higher income, better employment benefits, and more advancement opportunities [ 4 ]. Besides, academically successful students have higher self-esteem and self-confidence, low levels of anxiety and depression, are socially inclined, and are less likely to engage in substance abuse, i.e., alcohol and khat [ 5 ]. However, a cross-sectional study in Malaysia in higher learning institutions reported that an increasing number of students still do not graduate on time, suggesting that they did not perform well in their studies [ 6 ].

Despite excessive government investment in education, most students fail to achieve good academic performance at all levels of education. A correlational study in Arba Minch University, South Ethiopia, reported that the trend of graduating students is not proportional to the trend of enrolled students and more students commit readmission due to poor academic performance [ 7 ]. This resulted in unemployment, poverty, drugs elicit, promiscuity, homelessness, illegal activities, social isolation, insufficient health insurance, and dependence. Additionally, a systematic review in India concluded that poor academic achievement causes significant stress to the parents and low self-esteem to the students [ 8 ]. It is also significantly associated with high anxiety scores among university students in Pakistan [ 3 ]. Further, in public schools in Pakistan, academic failure affects self-concept and leads to a feeling of disturbance and shock. In this way, students finally drop out of the education system at all [ 9 ].

Beyond the quality of schools, various personal and family factors, including socioeconomic factors, English ability, class attendance, employment, high school grades, and academic self-efficacy have been proposed to influence academic performance. Besides, other factors, i.e., teaching skills, study hours, family size, and parental involvement have an association with academic performance as well [ 2 , 10 ]. A cohort study among university students in Australia concluded that aging does not impede academic achievement [ 11 ]. A secondary data analysis among fifth-grade students in Colorado showed that eating breakfast, normal body mass index, adequate sleep, and ≥ 5 days’ physical activity per week was significantly associated with higher cumulative grades [ 12 ]. A significant association was also found between joining the medical profession and good academic performance in Pakistan [ 13 ]. At Arba Minch University, students with a good academic record before campus entry were more likely to have academic success in higher education programs [ 7 ]. A descriptive study on Bahir Dar university students showed that the education status of parents and attending night club affect academic performance [ 14 ]. Also, a survey in Nigerian high schools indicated students whose parents were government employees achieved better performance [ 15 ]. However, the impact of these factors varies from region to region and differs in cities and rural areas. This might be due to diverse data measurement methods and quality or the context of each study.

One of the critical barriers to academic success is substance use. A cross-sectional study in the US among high school seniors showed that substance users had greater odds of skipping school and having low grades [ 16 ]. Similarly, a descriptive survey among primary school students in Jordan indicated that smoking affects children’s physical and mental development and reduces academic achievement. Smoking was considered a barrier to optimal learning [ 17 ]. A cross-sectional study among university students in Wolaita Sodo found that substance use (smoking, khat chewing, drinking alcohol, and having an intimate friend who uses substances) was significantly and negatively associated with students’ academic performance [ 18 ]. In Jordan Primary school students, smoking was more likely to impair cognitive development, and decrease attentiveness and memory. This in turn leads to difficulty in remembering information and verbal learning impairment [ 17 ].

Most of the previous studies focus on primary and secondary education levels and the problem is not well addressed at the university level. The poor performance of university students requests attention. Moreover, in Ethiopia, limited studies were done on this topic and it was complicated by confounding factors. Thus, this study intended to identify the predictors of academic performance among university students in Southern Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study design, setting, and period.

This is an institution-based cross-sectional study conducted among Hawassa University students from December 1 – 28, 2020. The University is one of the oldest public and residential national universities found in Hawassa city, Sidama Region. It is located 278 km south of Addis Ababa on the Trans-African Highway for Cairo-Cape Town. By the year 2020/21, the university has enrolled 21,579 students: 7955 Females and 13,624 Males. In general, there is one Institute of Technology and 10 colleges that offer 81 undergraduate, 108 Master’s, and 16 Ph.D. programs.

Sample size and eligibility criteria

The sample size was calculated using Open Epi version 3.03 statistical software using percent of controls exposed (58%), odds ratio 0.63 [ 19 ], 80% power, and 95% confidence interval. By considering a 5 % non-response rate the final sample size was 659. All students who undergo their education in the selected departments and are available at the time of data collection were included in the study. Non-regular students, mentally and physically incompetent, and those who were not willing to fill out the questionnaire were excluded.

Sampling procedure

The study was conducted among Regular Hawassa University students. A multi-stage sampling technique was applied to select study participants. The simple random sampling (SRS) technique was used to select representative colleges and departments. Students were stratified based on their batch/academic year. The sample size was distributed using probability proportional to size (PPS). Thereafter, SRS was applied to pick the required sample size from the predetermined sampling frame.

Academic performance was the dependent variable. Independent variables include sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, residence, parents’ education, family size, and faculty), individual factors (study hours, working after school, English language proficiency, sleeping hour, missing class, and entrance exam score), lifestyle and behavioral factors (substance use, breakfast, attending night club, and physical activity), and family and psychosocial variables (parents’ occupation, weight loss, and parent’s involvement).

Data collection tool and quality control

The data was collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire. Four data collectors and two supervisors participated in data collection. The questionnaire was prepared by reviewing similar published articles [ 2 , 7 , 20 ]. It was translated from English to the local language, Amharic, and then back to English by an independent translator to keep the consistency of the tool. Pre-testing was done on 5 % of the samples (33 students) at Dilla University and necessary adjustments were considered following the result (i.e., ethnicity, income). The principal investigators trained data collectors and supervisors about the objective and procedure of the study. The data were daily checked for completeness, consistency, and clarity.

Measurement

- Academic performance

Students who scored a cumulative GPA of 2.75 and above were categorized as “Good”, whereas those with a cumulative GPA of below 2.75 were categorized as “Poor” [ 7 ].

Participants who smoke at least one cigarette per day will be evaluated as smokers, and those who use more than one drink per day (any type of alcohol) will be considered alcohol consumers. Similarly, those who consume at least four glasses of tea and three cups of coffee per day will be accepted as those consuming tea and coffee, respectively [ 21 ].

Sugar intake

Excessive if individuals took 12 or more teaspoons of table sugar daily, moderate if 6 to 12 teaspoons; and restricted use if less than 6 teaspoons [ 22 ].

Extracurricular activities

Participation in school-based activities, i.e., sports, arts, and academic clubs [ 23 ].

Data management and analysis

Data were cleaned and entered into Epi-Data version 4.6 and SPSS statistical package version 25 was applied to perform all the statistical analysis. Cross-tabulation of variables was computed and the Chi-Square (X 2 ) test was used to analyze the variables. Pearson Chi-Square test was reported for variables that fulfill the assumption of the X 2 test. Whereas Fisher’s Exact Test was reported for variables having an expected count of less than five. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis were performed to identify independent predictors of academic performance. Variables with a p -value of ≤0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression were included in the final model. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of participants. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals were used to interpret the strength of association, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit was used to check for model fitness. A two-tailed p -value of ≤0.05 was considered to declare statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics of participants

Six hundred fifteen (615) students were involved in the study, making a 93.3% response rate. The age of students ranged from 18 to 29 years with the mean age of 21.62 ± 1.89 and 21.73 ± 2.08 for academically poor and good students, respectively. About 39% of rural residents had poor academic performance (PAP), whereas 69.3% of urban residents had good academic performance (GAP) ( p = 0.035). Further, more than one-third (38.9%) of non-medical/non-health students and 82.9% of medical/health students scored PAP and GAP, respectively ( p < 0.00) (Table 1 ).

Family and psychosocial characteristics

As shown in Table two below, 34% of students who experience weight loss scored poor academic results, while 66% of students who didn’t experience weight loss scored good academic results. Additionally, 38.7% of students who belong to agriculturalist families registered poor academic points, whereas 69.7% of students who belong to government employees scored academically good results (Table 2 ).

Behavioral characteristics

One-third (67%) of students involved in regular physical activity scored GAP. About 58.8% of students who smoke cigarettes had PAP, whereas 66.7% of students who didn’t smoke scored GAP (chi 2 p = 0.028). Additionally, 35% of students who attend night club scored PAP, while 66.2% of students who didn’t attend night club scored GAP (Table 3 ).

Personal characteristics

A higher proportion of participants who studied more than 4 hours per day (69.3%) scored GAP. One-third (35.4%) of students who sleep more than 7 hours per night registered PAP, while 68.4% of students who sleep less than 7 hours scored GAP. About 46.2% of students who had a pre-intermediate level of English proficiency were poor in academics, whereas 80.6% of students with an advanced level of proficiency were good in academics (chi 2 p = 0.002) (Table 4 ).

Overall, 406 (66%) of students had a good academic performance. The mean CGPA of students was 2.92 (SD ± 0.48), with a minimum of 1.80 and a maximum of 4.00 points. The mean CGPA of academically poor students was 2.39 points, which is lower by 0.81 compared to academically good students (3.20 points).

Determinants of academic performance

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, age, faculty, and smoking have shown a statistically significant association with academic performance (Table 5 ).

Students aged between 20 and 24 years were 56% less likely to score good academic performance compared to those who were aged between 25 and 29 years (AOR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.22-0.91). Medical/ health science students were two times more likely to attain good academic points compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.45-4.20). Students who didn’t smoke cigarettes were three times more likely to register good academic grades compared to those who smoke (AOR = 3.15, 95% CI = 1.21-7.30).

This study investigated the determinants of academic performance. The finding showed that only two-thirds (66%) of university students score good academic grades. Age, faculty, and cigarette smoking were found to have a statistically significant association with academic performance.

Students who didn’t smoke cigarettes were more likely to register good academic grades compared to those who smoke. This is consistent with the findings observed among university students in western societies. Smoking cigarettes were associated with decreased odds of high academic achievement in Norwegian students [ 19 ]. A cohort study in England showed that tobacco use was strongly linked with subsequent adverse educational outcomes [ 24 ]. Similarly, in Jordan, lower academic performance was positively associated with smoking [ 17 ]. In both Pakistan [ 25 ] and Korea [ 26 ], students who achieve good academic performance were less likely to smoke. Besides, a study from Finland suggested that smoking both predicts and is predicted by lower academic achievement [ 27 ]. The use of substances including smoking is known for its significant association with mental distress and depression. It also increases the risk of respiratory infections, asthma, tuberculosis, certain eye diseases, and problems of the immune system as well as increases the risk of bacterial meningitis, especially among freshman living in dorms. Additionally, smoking had a great influence on the attitude, emotion, and behavior of students, and can motivate them to perform their bests. For instance, in Australia, 69% of smokers attended bars, nightclubs, or gaming venues at least monthly [ 28 ] . Further, smokers are substantially engaged in khat chewing and alcohol drinking [ 29 ]. Having a serious health complication, wasting study hours, and concomitant substance use in college might prevent students from being able to perform their best in school. This finding call attention on prevention efforts aimed at students to reduce the detrimental consequences on academic performance.

In this study, students aged between 20 and 24 years were less likely to score good academic performance compared to those who were aged between 25 and 29 years. This effect favors the older students. A comparable result was obtained in Australia. The study showed that aging does not impede academic achievement and discrete cognitive skills as well as lifetime engagement in cognitively stimulating activities promote academic success in adults [ 11 ]. Similarly, age was positively related to the CGPA of the students in Nigeria [ 30 ]. According to a cross-sectional study in Norway, higher age was associated with better average academic performance of students [ 31 ]. Older students, that is 25 years and above are wiser and more mature. Students of a higher age may have a stronger motivation for studying and follow a more productive approach to studying; that means, they may employ more deep and strategic approaches than surface approaches. Additionally, older have more life experience than younger ones. Older students may personally or by their relationships to others, have experience with failure and success, illness and recovery, and loneliness and companionship in a range of settings and domains. Experience with the bright and the dark sides of life, and reflecting on and learning from that experience may encourage students’ ability to apply a variety of theoretical perspectives for academic assignments. As a result, older students may benefit and achieve good academic results.

The current study found that medical/ health science students were more likely to attain good academic points compared to their counterparts. Similarly, in Pakistan, joining the medical profession was significantly linked with good academic scores [ 13 ]. Admission to medical school was also a significant predictor of good academic performance in Nigeria [ 32 ]. Additionally, in Southern Ethiopia, poor academic performance was significantly higher among agriculture students than health science students [ 33 ]. The possible explanation might be that medicals students have higher levels of stress than non-medical and this was mostly attributed to their studies (75.6%) [ 34 ]. The stress showed beneficial effects on medical students. Exam, test, and assignment-related stress was associated with high attendance, better day-to-day activities, and good academic results [ 35 ]. In addition, medical students had significantly higher intrinsic motivation for academics [ 36 ].

The study has some limitations. First, there might be social desirability bias as a result of self-administered data collection techniques. However, anonymity and confidentiality were assured. Second, some potential confounders, i.e., institutional influences were not controlled. Third, self-reporting may have resulted in under or over-reporting of some factors. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature does not allow the making of direct causal inferences.

Implication

Education is a powerful agent of change that produces qualified human power, improves health and livelihoods, accelerates economic development, and solves the real problems of a community. Students are expected to spend much of their time on their education and need to graduate with good academic results. Academically good students have better employment benefits, higher income, higher self-esteem and self-confidence, low levels of anxiety and depression, and are less likely to engage in substance abuse. However, in this study, only two-thirds of university students achieved good academic grades. Smoking, age, and field of study were significantly associate with academic performance. The finding of the study had the academic implication that cessation of smoking had a paramount benefit for academic success, and hence more employment opportunities and good quality of life.

Increased odds of good academic performance were observed among students reported to be non-smokers, adults, and medical/health science students. Reduction or discontinuation of smoking is of high importance for good academic achievement among these target groups. The finding suggests that higher university officials need to raise awareness regarding the adverse educational outcomes of smoking through public service announcements and curriculum-based education. Additionally, policies concerning smoking restrictions in community spaces and university facilities may help reduce the onset of smoking. The current action taken to promote a smoke-free student population can impact the future health of Ethiopians, future leaders, scholars, and professionals. Further, the academic environment in the class may be improved if older students are invited to share their views and particularly their way of reasoning. Although this study had provided some primary evidence, more similar studies documenting the association between tobacco use and academic performance among Ethiopian University students are warranted.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author and can be presented upon a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Cumulative Grade Point Average

Good Academic Performance

Poor Academic Performance

Statistical Package for Social Science

Simple Random Sampling

World Health Organization

Idris F, Hassan Z, Ya’acob A, Gill SK, Awal NAM. The role of education in shaping youth’s national identity. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;59:443–50.

Article Google Scholar

Sothan S. The determinants of academic performance: evidence from a Cambodian University. Stud High Educ. 2019;44(11):2096–111.

Talib N, Sansgiry SS. Determinants of academic performance of University students. Pakistan. J Psychol Res. 2012;27(2):265–78.

Tentama F, Abdillah MH. Student employability examined from academic achievement and self-concept. Int J Eval Res Educ. 2019;8(2):243–8.

Google Scholar

Regier J. Why is academic success important. Appl Sci Technol Scholarsh. 2011:1–2.

Ab Razak WMW, Baharom SAS, Abdullah Z, Hamdan H, Abd Aziz NU, Anuar AIM. Academic performance of University students: a case in a higher learning institution. KnE Soc Sci. 2019:1294–304.

Yigermal ME. Determinant of academic performance of under graduate students: in the cause of Arba Minch University Chamo Campus. J Educ Pract. 2017;8(10):155–66.

Karande S, Kulkarni M. Poor school performance. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72(11):961–7.

Chohan BI. The impact of academic failure on the self-concept of elementary grade students. Bull Educ Res. 2018;40(2):13–25.

Mushtaq I, Khan SN. Factors affecting students’ academic performance. Glob J Manag Bus Res. 2012;12(9):17–22.

Imlach A-R, Ward DD, Stuart KE, Summers MJ, Valenzuela MJ, King AE, et al. Age is no barrier: predictors of academic success in older learners. NPJ Sci Learn. 2017;2(1):1–7.

Stroebele N, McNally J, Plog A, Siegfried S, Hill JO. The association of self-reported sleep, weight status, and academic performance in fifth-grade students. J Sch Health. 2013;83(2):77–84.

Khan KW, Ramzan M, Zia Y, Zafar Y, Khan M, Saeed H. Factors affecting academic performance of medical students. Life Sci. 2020;1(1):4.

Tiruneh WA, Petros P. Factors affecting female students’ academic performance at higher education: the case of Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. Afr Educ Res J. 2014;2(4):161–6.

Atolagbe A, Oparinde O, Umaru H. Parents’ occupational background and student performance in public secondary schools in Osogbo Metropolis, Osun State, Nigeria. Afr J Inter/Multidisciplinary Stud. 2019;1(1):13–24.

Bugbee BA, Beck KH, Fryer CS, Arria AM. Substance use, academic performance, and academic engagement among high school seniors. J Sch Health. 2019;89(2):145–56.

Kawafha MM. Factors affecting smoking and predictors of academic achievement among primary school children in Jordan. Am J Heal Sci. 2014;5(1):37–44.

Mekonen T, Fekadu W, Mekonnen TC, Workie SB. Substance use as a strong predictor of poor academic achievement among university students. Psychiatry J. 2017;2017:7517450.

Stea TH, Torstveit MK. Association of lifestyle habits and academic achievement in Norwegian adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–8.

Tessema B, Wolde W, Walelign A, Sibera S. Determinants of academic performance of students: case of Wolaita Sodo University. In: Research review workshop. 2014. p. 122.

Unsal A, Ayranci U, Tozun M, Arslan G, Calik E. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and its effect on quality of life among a group of female university students. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115(2):138–45.

Muluneh AA, seyuom Nigussie T, Gebreslasie KZ, Anteneh KT, Kassa ZY. Prevalence and associated factors of dysmenorrhea among secondary and preparatory school students in Debremarkos town, North-West Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):1–8.

Abruzzo KJ, Lenis C, Romero YV, Maser KJ, Morote E-S. Does participation in extracurricular activities impact student achievement? J Leadersh Instr. 2016;15(1):21–6.

Stiby AI, Hickman M, Munafò MR, Heron J, Yip VL, Macleod J. Adolescent cannabis and tobacco use and educational outcomes at age 16: birth cohort study. Addiction. 2015;110(4):658–68.

Ullah S, Sikander S, Abbasi MMJ, Rahim SA, Hayat B, Haq ZU, et al. Association between smoking and academic performance among under-graduate students of Pakistan, a cross-sectional study. 2019.

Book Google Scholar

So ES, Park BM. Health behaviors and academic performance among Korean adolescents. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2016;10(2):123–7.

Latvala A, Rose RJ, Pulkkinen L, Dick DM, Korhonen T, Kaprio J. Drinking, smoking, and educational achievement: Cross-lagged associations from adolescence to adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;137:106–13.

Trotter L, Wakefield M, Borland R. Socially cued smoking in bars, nightclubs, and gaming venues: a case for introducing smoke-free policies. Tob Control. 2002;11(4):300–4.

Deressa Guracho Y, Addis GS, Tafere SM, Hurisa K, Bifftu BB, Goedert MH, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with current cigarette smoking among ethiopian university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Addict. 2020;2020:9483164.

Abubakar RB, Bada IA. Age and gender as determinants of academic achievements in college mathematics. Asian J Nat Appl Sci. 2012;1(2):121–27.

Bonsaksen T, Ellingham BJ, Carstensen T. Factors associated with academic performance among second-year undergraduate occupational therapy students. Open J Occup Ther. 2018;6(1):14.

Ekwochi U, Osuorah DIC, Ohayi SA, Nevo AC, Ndu IK, Onah SK. Determinants of academic performance in medical students: evidence from a medical school in south-east Nigeria. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:737.

Mehare T, Kassa R, Mekuriaw B, Mengesha T. Assessing predictors of academic performance for NMEI curriculum-based medical students found in the Southern Ethiopia. Educ Res Int. 2020;2020:8855306.

Aamir IS, Aziz HW, Husnain MAS, Syed AMJ, Imad UD. Stress level comparison of medical and nonmedical students: a cross sectional study done at various professional colleges in Karachi, Pakistan. Acta Psychopathol. 2017;3(02):1–6.

Kumar M, Sharma S, Gupta S, Vaish S, Misra R. Medical education effect of stress on academic performance in medical students-a cross-sectional study. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;58(1):81–6.

Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1742964.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the study participants, data collectors, and supervisors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

Mesfin Tadese

Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wolkite University, Wolkite, Ethiopia

Alex Yeshaneh

Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

Getaneh Baye Mulu