- Help Center

- Fix a problem

- Watch videos

- Manage your account & settings

- Supervised experience on YouTube

- YouTube Premium

- Create & grow your channel

- Monetize with the YouTube Partner Program

- Policy, safety, & copyright

- Privacy Policy

- YouTube Terms of Service

- Submit feedback

- Creator Tips

- Fix a problem Troubleshoot problems playing videos Troubleshoot account issues Fix upload problems Fix YouTube Premium membership issues Get help with the YouTube Partner Program Learn about recent updates on YouTube Get help with YouTube

- Watch videos Find videos to watch Change video settings Watch videos on different devices Comment, subscribe, & connect with creators Save or share videos & playlists Troubleshoot problems playing videos Purchase & manage movies, TV shows & products on YouTube

- Manage your account & settings Sign up and manage your account Manage account settings Manage privacy settings Manage accessibility settings Troubleshoot account issues YouTube updates

- YouTube Premium Join YouTube Premium Learn about YouTube Premium benefits Manage your Premium membership Manage Premium billing Fix YouTube Premium membership issues Troubleshoot billing & charge issues Request a refund for YouTube paid products YouTube Premium updates & promotions

- Create & grow your channel Upload videos Edit videos & video settings Create Shorts Edit videos with YouTube Create Customize & manage your channel Analyze performance with analytics Translate videos, subtitles, & captions Manage your community & comments Live stream on YouTube Join the YouTube Shorts Creator Community Become a podcast creator on YouTube Creator and Studio App updates

- Monetize with the YouTube Partner Program YouTube Partner Program Make money on YouTube Get paid Understand ads and related policies Get help with the YouTube Partner Program YouTube for Content Managers

- Policy, safety, & copyright YouTube policies Reporting and enforcement Privacy and safety center Copyright and rights management

- Analyze performance with analytics

- Research tab

Understand research insights

We're currently experiencing high contact volumes. If you contact us, you may notice longer than normal wait times.

To explore what your audience and viewers across YouTube are searching for, you can use the Research tab in YouTube Analytics. The insights from the Research tab can help you think of video ideas that viewers may want to watch.

View the research tab

- Sign in to YouTube Studio .

- In the left menu, select Analytics .

- Click the Research tab.

- To get started, enter a search term in the search bar. To save a search term, click Save .

After you enter a search term, you can view viewer activity related to that topic:

- Recent audience activity : Shows how popular the topic is with your audience.

- Searched on YouTube : Shows popular searches made by viewers across YouTube for the topic.

- Watched on YouTube : Shows popular videos watched by viewers across on YouTube for the topic.

Note : For now, insights are limited to search queries in English from viewers in the United States, United Kingdom, India, Australia, and Canada.

What the research tabs show

Searches across youtube.

This tab shows the top related searches for a search term over the last 28 days. Viewers across YouTube, not just your audience, make these searches.

- Next to each search term, there’s a level that describes how popular the term is: low, medium, or high.

- Next to some search terms, there’s a label that says Content gap . Learn more about Content gaps .

- To get data that’s more specific, you can filter the results by Content gaps, Geography, or Language.

Note : If there are no search results, it’s because there isn’t enough data to estimate your audience’s interest.

Your viewers’ searches

This tab shows the top searches that your audience and viewers of similar channels have searched over the last 28 days.

- Next to each search term, there’s a search volume rank that describes how popular the term is: low, medium, or high.

Watch and learn about search insights

To learn more about search insights on the computer, check out the following video from the YouTube Creators channel.

Understand Search Insights: Research Tab in YouTube Analytics

Was this helpful?

Fifteen years of YouTube scholarly research: knowledge structure, collaborative networks, and trending topics

- Published: 19 September 2022

- Volume 82 , pages 12423–12443, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Mohamed M. Mostafa 1 ,

- Ali Feizollah 2 &

- Nor Badrul Anuar 2

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Since its inception, YouTube has been a source of entertainment and education. Everyday millions of videos are uploaded to this platform. Researchers have been using YouTube as a source of information in their research. However, there is a lack of bibliometric reports on research carried out on this platform and the pattern in the published works. This study aims at providing a bibliometric analysis on YouTube as a source of information to fill this gap. Specifically, this paper analyzes 1781 articles collected from the Scopus database spanning fifteen years. The analysis revealed that 2006-2007 were initial stage in YouTube research followed by 2008 -2017 which is the decade of rapid growth in YouTube research. The 2017 -2021 is considered the stage of consolidation and stabilization of this research topic. We also discovered that most relevant papers were published in small number of journals such as New Media and Society, Convergence, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Computers in Human Behaviour and the Physics Teacher, which proves the Bradford’s law. USA, Turkey, and UK are the countries with the highest number of publications. We also present network analysis between countries, sources, and authors. Analyzing the keywords resulted in finding the trend in research such as “video sharing” (2010-2018), “web -based learning” (2012-2014), and “COVID -19” (2020 onward). Finally, we used Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) to find the conceptual clusters of research on YouTube. The first cluster is related to user -generated content. The second cluster is about health and medical issues, and the final cluster is on the topic of information quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Quantitative Analysis of Scholarly References on YouTube

Science and Medicine on YouTube

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since its acquisition by Google in 2005, YouTube has been a video -sharing social media and a search engine with over 2 billion views per month [ 41 ]. It allows users to upload videos and share their content. It is a preferred search engine for contents like cooking recipes because of its audio and visual medium of communication. In addition to watching the videos, users can leave their comments and feedbacks for each video. The combination of audio, video, and comments make YouTube a valuable source of data. Researchers have been using this source of data to analyze various topics across wide range of research domains. One of the research domains that utilizes YouTube is health and healthcare. Educational videos and users’ feedback towards them have been a common research topic. For example, Li et al. [ 41 ] examined YouTube as a source of information on COVID -19 pandemic. Khatri et al. [ 34 ] also researched YouTube as a source of information on COVID -19 on English and Mandarin content. Hussein et al. [ 30 ] evaluated YouTube as a source of information by measuring the information on this platform and by auditing misinformation in videos. Indirectly, some research works developed methods that can be used in YouTube video analysis [ 42 , 56 , 57 , 45 ]. Analyzing research trends in YouTube papers requires the use of the bibliometric method.

Bibliometric is a quantitative analysis of papers published in a specific research domain [ 46 ]. The bibliometric study analyzes the authors’ activities, publication trends, and collaborations among institutions and countries. The bibliometric analysis evaluates impact of published papers and reveals the potential gaps and future directions in a research area, which increases interest and attention of researchers and funding bodies. The bibliometric study has been used in many research areas like COVID -19 pandemic [ 26 ], agricultural [ 47 ], accounting [ 50 ], and economic [ 8 ]. The advantages of using a bibliometric study are: 1) reveals important research works in a research domain; 2) helps to discover the gaps need to be addressed by researchers; 3) gives young researchers a holistic view of a research area.

To scrutinize research trends and direction on YouTube, this study aims at performing a bibliometric analysis on research works focused on YouTube published between 2006 and 2021. We propose the following research questions to fulfill the aim of this study: 1) what are the trends and directions in YouTube research? And 2) what information can be discovered related to YouTube research? The contributions of this study are as following:

we found only one published paper on YouTube bibliometric study, which presents number of papers, citations, and countries that published research works related to YouTube [ 56 ]. However, our work presents a more comprehensive analysis of the YouTube papers by providing network analysis, research structure, and thematic mapping.

we present a comprehensive network analysis like co -citation network, co -cited sources network, authors’ collaboration network, institutions’ collaboration network, nations’ network, as well as keywords and co -occurrence network.

We analyze the trending research and provide a structured research trends as well as thematic and historiographic mapping.

we adopt dominance factor, Bradford’s law, and Lotka’s law to analyze the published works using scientific methods.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology used to carry out the analysis. Section 3 deals with research findings. Section 4 discusses the research findings. The last section deals with research limitations and explores potential avenues for future research.

This study is guided by the following four steps:

Selecting the database and defining the search terms.

Conducting the preliminary statistical analysis.

Performing the bibliometric network analysis.

Performing the conceptual structure, thematic and historiographic mapping.

To conduct the analysis, the R version 4.1 software [ 58 ] was used along with several libraries such as the bibliometrix, wordcloud and ggplot2 . For network visualization, we used the VOSviewer software [ 61 ]. We discuss here the steps outlined above in some detail.

2.1 Database and documents’ extraction

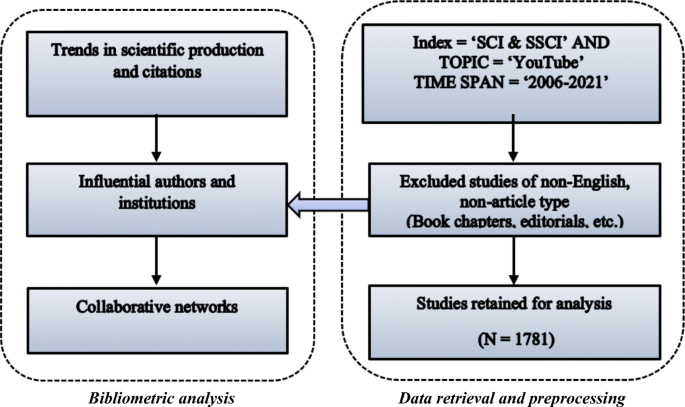

Following Sigala et al. (2021), the Scopus database was selected to conduct the analysis. As the largest database for peer -reviewed journals (Norris & Oppenheim, 2007), Scopus is frequently used by researchers to conduct bibliometric analysis (Cunill et al., 2019; Hassan et al., 2021). Having selected the database, we extracted bibliographic records related to the selected documents, including relevant information about documents’ titles, authors, and keywords. Retrieved documents were then transformed to a plain text format for further filtering and analysis. Choosing a particular type of document for bibliometric analysis has long been the subject of debate [ 51 , 52 ]. For instance, journal articles only have been selected in prior studies (e.g., [ 20 ]), whereas some authors have focused on both books and journal articles (e.g., [ 4 ]), yet others excluded only meeting abstracts, corrections, and editorial material, (e.g., [ 2 ]). Here, we opted for peer -reviewed articles only because such articles “usually undergo a meticulous peer -review process and are generally of high quality” ([ 16 ], p. 206). To avoid false -positive results, only article titles, abstracts and keywords were searched using the terms “YouTube.” Figure 1 plots the search procedure followed to extract the articles used in this analysis. We limited the selection to documents written in English and we chose 2006 as the date of reference because YouTube was launched in 2006.

Schematic flowchart of data acquisition and methodology (Adapted from [ 15 ])

Having selected the database, we extracted bibliographic records related to the selected documents, including relevant information about documents’ titles, authors, and keywords. Retrieved documents were then transformed to a plain text format for further filtering and analysis. Choosing a particular type of document for analysis has long been the subject of debate [ 51 , 52 ]. For instance, journal articles only have been selected in prior studies (e.g., [ 20 ]), whereas some authors have focused on both books and journal articles (e.g., [ 4 ]), yet others excluded only meeting abstracts, corrections, and editorial material, (e.g., [ 2 ]). Here, we opted for peer -reviewed articles only because such articles “usually undergo a meticulous peer -review process and are generally of high quality” ([ 16 ], p. 206).

Table 1 shows the main information about the YouTube research data.

The table reveals that 1781 research articles were extracted. The articles were written by 4699 authors, and they include 65,677 references. 417 articles were written by single authors, whereas 567 were written by multi -authors, with a collaboration index of 3.26. This index is calculated by dividing the total authors of multi -authored articles by total multi -authored articles [ 23 , 36 ]. Our result indicates that the average YouTube research team falls between 3 and 4.

2.2 Bibliometric network analysis

A network can be regarded as “a structure composed of a set of actors, some of whose members are connected by a set of one or more relationships” ([ 35 ], p. 8). In social network analysis (SNA), an edge connecting two nodes represents a relationship. Khan and Wood [ 32 ] noted that “when used to synthesize the existing literature from a network perspective, the SNA technique can reveal valuable invisible patterns that can certainly facilitate theory development and uncover areas for future research.” There has been extensive prior research using network analysis in areas as diverse as exploring individual scientific collaboration networks [ 11 , 27 , 66 ], collaboration among research institutions [ 21 ] and keywords co -occurrence networks [ 7 ].

2.3 Thematic and conceptual structure maps

Thematic maps or strategic diagrams were suggested by Law et al. [ 39 ]. The map is usually employed to reveal the clusters’ dynamics based on analyzing the keywords or co -word occurrences [ 29 ]. The Callon et al. [ 10 ] density and centrality metrics are generally used to construct the map. The map also draws heavily on the financial portfolio analysis and concepts based on co -word networks [ 5 ]. Due to its usefulness, the map has been used in a plethora of research articles [ 33 , 40 , 65 ]. On the other hand, conceptual structure maps can be employed to investigate the conceptual structure of a research area by breaking down a research domain into clear “knowledge clusters” [ 63 ].

3.1 Scientific output, core journals and impactful authors

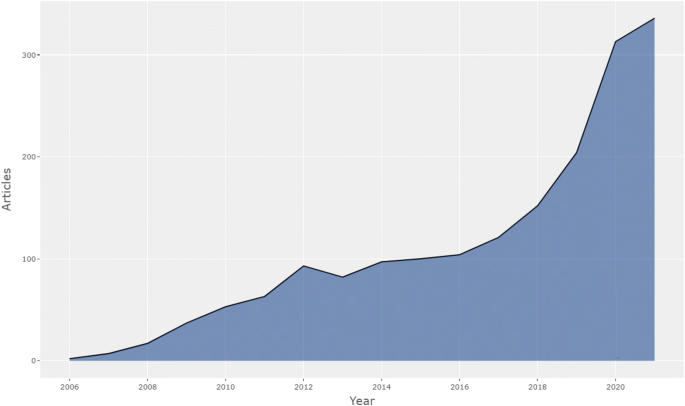

We extracted 1781 Scopus documents related to YouTube. The documents were written by 4699 authors representing 70 nations. Timewise, the documents covered almost fifteen years (2006-2021). Figure 2 plots the scientific output trends in the field. Although the figure reveals an exponential annual growth rate, this rate is not evenly distributed. For instance, in the first two years there was a paucity in YouTube research with only a handful of papers per year. These two years might be referred to as “the initial stage in the YouTube research.” However, the next decade (2008-2017) appears to witness a tremendous increase in research dealing with YouTube. This decade might be called “the rapid growth stage.” Indeed, this period represents the highest growth rate. The final stage (2018-2021) might be called the “consolidation and stabilization stage” because the YouTube research reached the “saturation/maturity” stage. This result is in line with several bibliometric studies conducted in several research areas [ 53 , 66 ].

YouTube research annual scientific production (2006–2021)

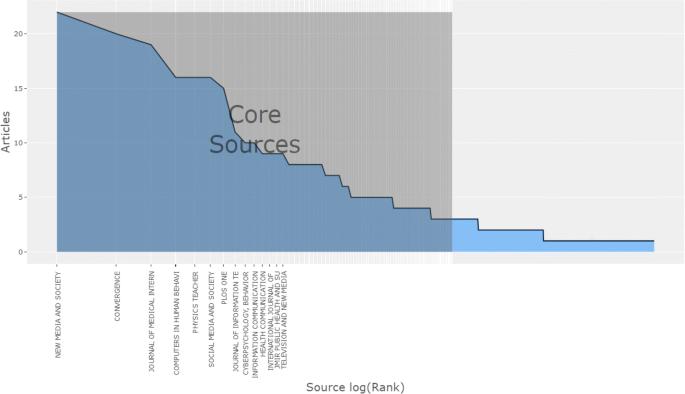

Table 2 shows the most important Scopus -indexed journals publishing YouTube research. The table reveals that the most relevant sources publishing YouTube research include journals such as New Media and Society, Convergence, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Computers in Human Behavior and the Physics Teacher . Another way to examine the journals’ influence is known as the Bradford’s law [ 37 ]. This law was first proposed by Bradford [ 9 ], who noted that “if scientific journals are arranged in order of decreasing productivity of articles on a given subject, they may be divided into a nucleus of periodicals more particularly devoted to the subject and several groups or zones containing the same number of articles as the nucleus.” Fig. 3 plots the Bradford’s law in YouTube research. From the graph, we see that the “core zone” is dominated by just few journals, including New Media and Society, Convergence, Journal of Medical Internet Research, etc. Such journals are considered the outlets publishing the “core” YouTube research.

Bradford’s law in YouTube scholarly research

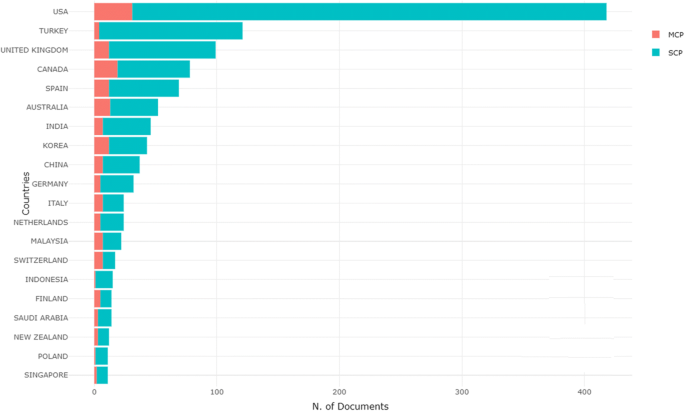

The YouTube research growth is also evident from the corresponding author’s country involved (Fig. 4 ).

YouTube research by corresponding author’s country. Note: SCP = Single Country Production; MCP = Multiple Country Production

Table 3 shows the most cited articles in YouTube research. The table shows that Smith et al. (2012) paper in the Journal of Interactive Marketing is the most cited paper as it was cited 457 times. In this article, the authors compared brand -related user -generated content between three social media platforms, namely Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Results provide a general theoretical framework demonstrating how consumer -generated brand communications are influenced by a particular social media channel. The second most cited paper (443 citations) is Lang (2007) paper published in the Journal of Computer - Mediated Communication. In this paper, the author employed ethnographic methodology to analyze how YouTube participants develop and maintain social networks related to video sharing activities. With 333 citations, Susarla et al. (2011) article is the third most cited paper. In this article published in Information Systems Research , the authors analyzed the networked structure of interactions on YouTube. Results revealed that “social interactions are influential not only in determining which videos become successful but also on the magnitude of the impact.” (p. 23). Halpern and Gibbs (2013) paper published in Computers in Human Behavior was cited 298 times. In this paper the authors used two social media platforms, namely YouTube and Facebook to examine how social media can be used to foster democratic deliberations. Results showed that the “Facebook expands the flow of information to other networks and enables more symmetrical conversations among users, whereas politeness is lower in the more anonymous and deindividuated YouTube” (p. 1159). Khan’s (2017) paper published in Computers in Human Behavior was cited 291 times. In this paper the author investigated motives behind YouTube users’ engagement. Results revealed that YouTube participation is driven mainly by the relaxing/entertainment motive. However, passive content viewing was mainly driven by reading comments posted on the platform. Table 4 .

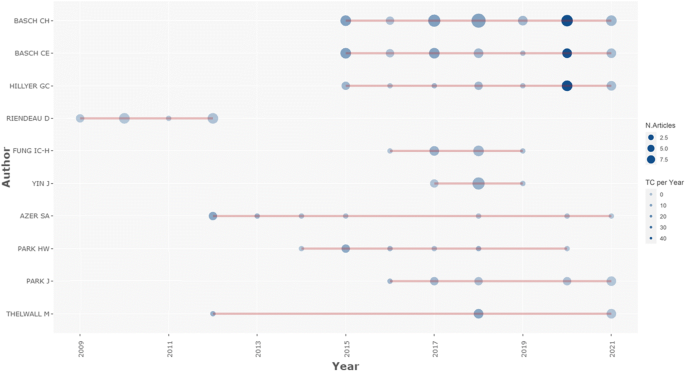

The dominance factor is a bibliometric measure that calculates authors dominance by dividing the number of multi -authored articles in which the author is the first author by the total number of multi -authored articles [ 38 ]. This metric has been used widely in the literature [ 23 , 25 ]. Figure 5 shows the dominating authors over time. From the figure, we see that the most dominating authors were C Basch from 2015 till 2021, Riendeau from 2009 till 2012 and S Azer from 2012 to 2021. Newcomers to the field have also achieved some dominance. Examples include J Yin (2017-2019) and J Park (2016-2021).

YouTube authors dominance over the time

In bibliometric studies, “Evenness/concentration of authors’ contribution” is a widely used metric [ 49 ]. This metric can be quantified using Lotka’s law (Lotka, 1926). Based on the well -known Zipf’s law, Lotka’s law implies that “the number of authors producing a certain number of articles is a fixed ratio, 2, to single -article authors.” Results suggests that the Lotka’s law seems to hold in YouTube research ( K - S two sample test p > 0.05).

3.2 Network analysis

3.2.1 co -citation networks.

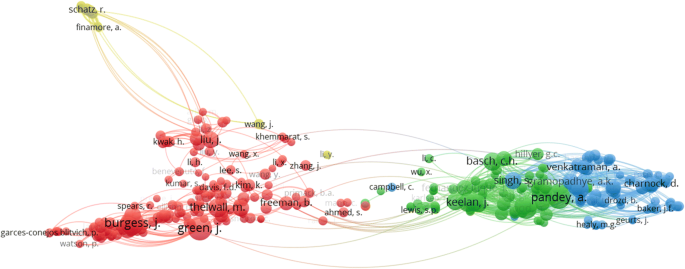

A co -citation network is formed when two authors are cited together in a third reference. Figure 6 displays the YouTube research co -cited authors’ network. Based on the color used, the graph reveals four distinct clusters. The red cluster includes authors such as J Burgess, M Thelwall and J Green. The size of the node indicates which author occupies a central position in the cluster. Such author(s) might be regarded as influential as they have disproportionate impact on the information diffusion on the network [ 6 ]. From the graph, we also see that some nodes are quite close to each other, whereas others drift further away. McPherson et al. [ 48 ] argued that closeness signifies a strong “homophily effect,” which occurs when authors in a virtual -room -like environment discuss common topics [ 24 ]. In bibliometrics, homophily is an indicator of “disciplinary or thematic similarity” [ 31 ]. For example, the nodes representing both R Schatz and A Finamore are very close to each other, indicating possible “homophily effect.”

YouTube authors co-citation network (> = 30 articles)

The green cluster includes authors such as C Basch, J Keelan, A Pandy and S Sarangi. The blue cluster includes sixty -two authors such as J Baker, D Charnock, A Rapp and J Lee. The yellow cluster is the smallest and it includes ten authors such as A Finamore, R Schatz and J Wang. The centrally located authors in each cluster might be regarded as influential authors as they “tend to anchor each community and they have a large impact on other communities as they control and stimulate information diffusion [in the network] through research activities” ([ 53 ], p. 664).

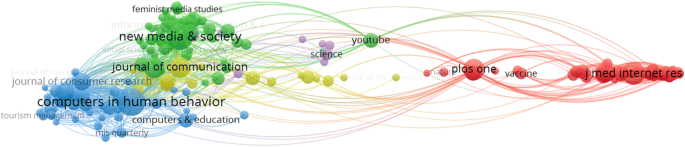

Figure 7 displays the YouTube research co -cited sources’ network. The graph reveals five distinct clusters. For example, the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, Epilepsy Behavior and the Journal of Cancer Education are co -cited together as they belong to the same cluster. The American Sociological Review is co -cited with Discourse and Society, and Feminist Media Studies . The Journal of Advertising is co -cited with the Journal of Business Research and the Journal of Consumer Research , whereas Body Image is co -cited with the Journal of Pragmatics and Sex Roles . Interestingly, “core” journals occupy central position in the network with a minimal interaction among the distinct clusters, confirming what Glotzl and Aigner [ 28 ] term “the orthodox core -heterodox periphery” phenomenon within the field of YouTube research. Dobusch and Kapeller [ 22 ] found that “orthodox journals” tend to be heavily cited, whereas “heterodox journals” tend to be drifted towards the periphery.

YouTube source co-citation network (> = 30 articles)

3.2.2 Collaboration networks

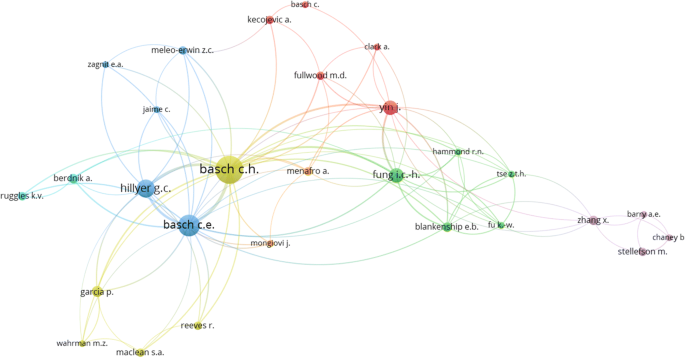

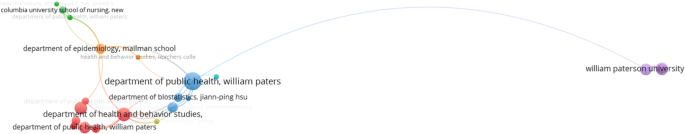

The collaboration network among authors is depicted in Fig. 8 . The thickness of the link in this graph is proportionate to articles coauthored, whereas the node size is formed based on the author’s publications. A glance at the graph reveals that the sparse network is formed by seven distinct communities, signifying a limited cooperation among authors. The sparse network implies that impactful researchers in the field work in isolated “silos” [ 62 ].

YouTube authors’ collaboration network (documents > = 2 articles)

Figure 9 depicts the collaboration network at the institutional level. The thickness of the link is proportional to the institution’s collaboration, whereas the node size is formed based on each institution’s publications. From the graph, we see that there are seven distinct clusters. For example, there is a strong collaboration between Columbia University, the New York University and the William Paterson University in the US. Zou et al. [ 66 ] argued that this type of sparse collaboration reflects a “locally -centralized -globally -discrete” cooperation. It also reflects a “North -South” divide, with a clear lack of cooperation between developed/developing world institutions.

Collaboration network among institutions producing YouTube research (documents > = 1 article)

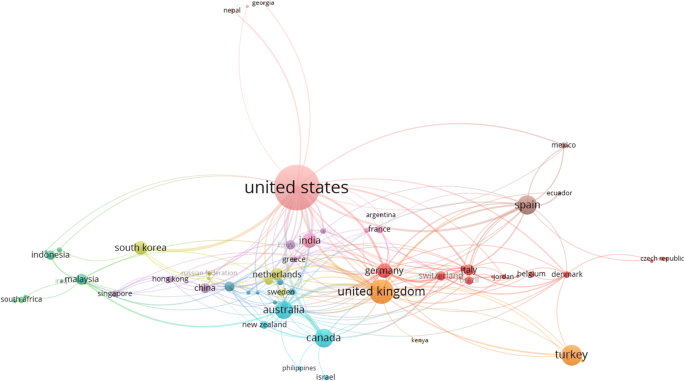

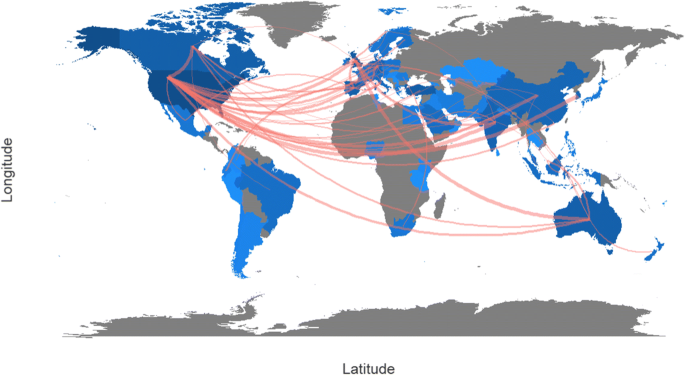

Figure 10 shows the collaboration at the nations’ level, with a total of 62 nations collaborating in the scientific production of YouTube research. The figure shows that US tops the world in terms of the total collaboration links, followed by the UK and Australia. A closer look at the graph reveals that some clusters are formed based on geographic distance or linguistic similarity. For example, Spain cooperates with Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico. The cluster that includes Egypt also includes Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Figure 11 plots the “geographic atlas” of the countries producing the YouTube research.

Collaboration network among nations producing YouTube scholarly research (documents > = 2 articles)

Geographic atlas of collaboration among nations producing YouTube scholarly research

3.2.3 Keywords and co -occurrence network analysis

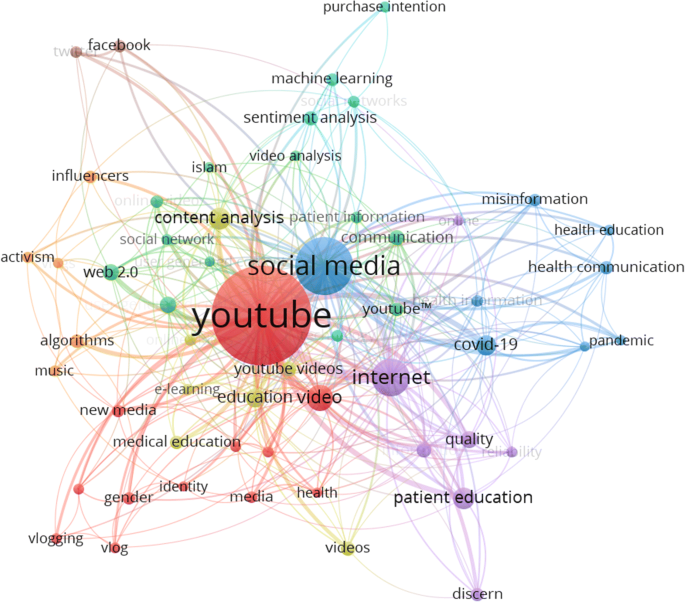

Due to their abstract nature [ 12 ], keywords can be used to reveal the content of a paper. Figure 12 shows a simple wordcloud constructed based on the author -provided keywords. A wordcloud plot is an appealing visual tool that can be used to summarize textual data. The size of each word and its closeness to the cloud center determine its significance [ 42 , 43 ]. From the figure we see that the most relevant/frequent keywords used are “Youtube”, “social media” and “Internet.”

Keyword-based wordcloud of the most frequent YouTube terms

To further scrutinize how frequently keywords co -occur in the same document, we also used the author -provided keywords to construct the YouTube keyword co -occurrence network because “authors of a paper should be the ones that have the best feel as to what areas are spoken to by the paper” [ 19 ]. Figure 13 displays the resulting co -occurrence network. The graph reveals eight main clusters. For example, the first cluster in blue deals with medical/health use of the YouTube and includes words such as “health communication”, “health education” and “health information”. The second cluster (green -colored) deals with consumer comments and includes words such as “user -generated content”, “social network” and “Web 2.0”. The third cluster (yellow -colored) deals mainly with the educational use of the YouTube and includes words such as “e -learning”, “medical education” and “online videos”.

Co-occurrence network for author-provided YouTube keywords

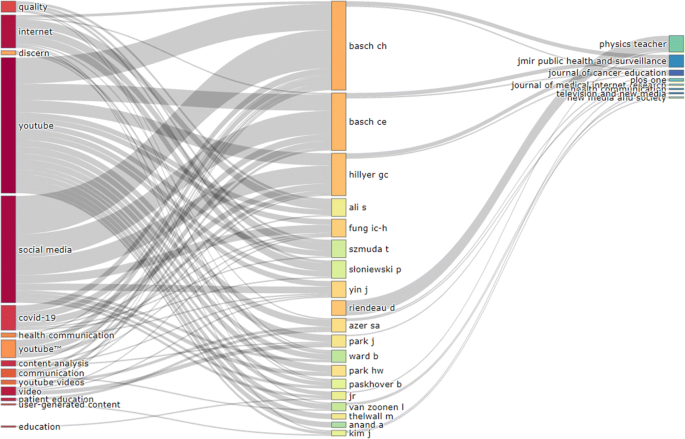

A three -field plot, also known as a Sankey diagram, was also used to contextualize the flow trend linking keywords (left), authors (middle) and sources (right). In this diagram the size of the boxes is proportional to the related quantity (keyword, author, or source). Figure 14 displays the YouTube research Sankey diagram. Not surprisingly, edge widths flowing from keywords as “YouTube”, “social media”, and “Internet” are the largest, signifying that such keywords were used by several authors in their publications. We see also see that while some authors have used an extensive list of the keywords reflecting the diversity of their research (C Basch), others used a unique keyword (J Kim).

Sankey diagram for YouTube research flow (kewword-author-reference)

3.2.4 Trending topics and thematic evolution

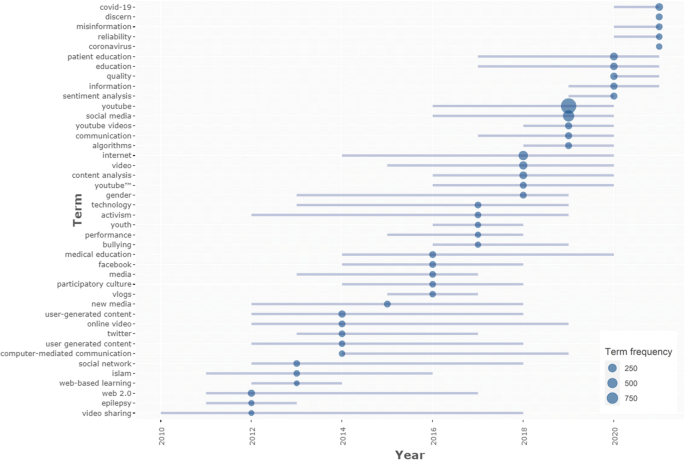

Figure 15 plots the major YouTube research trending topics. From the graph we see that there is a move from established YouTube topics such as “video sharing” (2010-2018) and “web -based learning” (2012-2014) to new topics such as “COVID -19” (2020 onwards) and “misinformation” (2020 onwards). Such topics might be regarded as “trending topics/hotspots” in the scholarly publications dealing with YouTube because it has been argued that trending topics usually represent hotspots or evolving themes in a specific research domain [ 13 , 14 , 54 , 60 ]. Abrupt burst or surge in keywords might be also an indicator of “potential fronts” [ 57 ] as “the body of knowledge in a certain discipline can be seen as a sequence of topics that appear, grow in importance for a particular period and then disappear” [ 18 ].

YouTube research trending topics

3.3 Conceptual structure and thematic maps

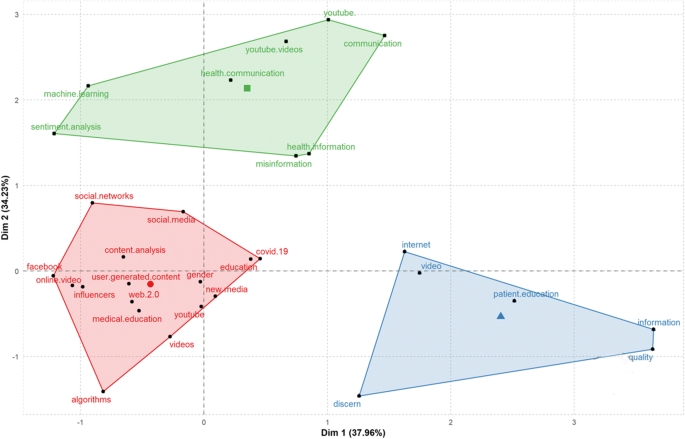

We applied the Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) method on the author -provided keywords. The MCA is an extension of correspondence analysis, akin to the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), that helps to analyze the pattern of relationships of categorical data [ 1 ]. It was selected since the results of this method is proved to be better on categorical data compared to other methods [ 1 ]. Figure 16 depicts the resulting YouTube research conceptual structure over four decades. From the graph, we see that the best dimension reduction achieved for the first two dimensions of the MCA account for roughly 72% of the total variability. In this graph, the closer the dots, the similar the profile they represent, whereas each cluster of dots represents discriminating profiles [ 64 ].

Conceptual structure map for YouTube scholarly research (MCA method)

An inspection of the graph reveals the depth and breadth of the domain. For instance, the largest red cluster comprises keywords emphasizing the consumer -generated content such as “user -generated content”, “web 2.0” and “online video.” The second cluster (in green) appears to deal with health and medical issues and includes keywords such as “health communication”, “health information” and “misinformation.” The third cluster in blue appears to deal with YouTube research within the context of information quality and includes keywords such as “internet”, “information” and “quality.”

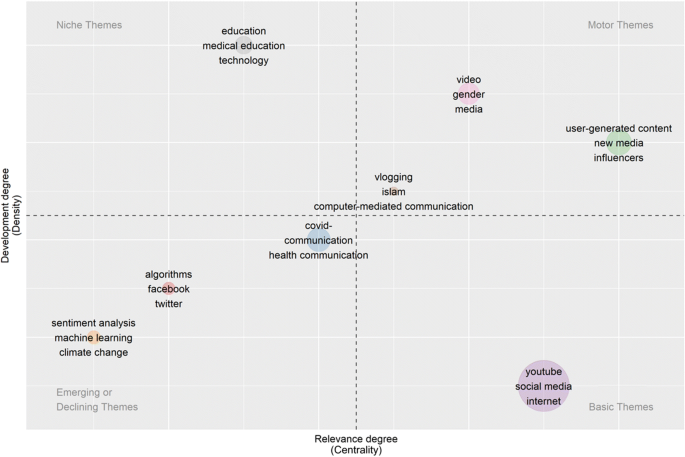

A thematic/strategic map is also shown in Fig. 17 . In this graph, average values of both axes are represented by a dotted line dividing the map into four quadrants. Each quadrant in this graph represents a different theme, whereas the bubble size is drawn in proportion to the frequency of documents in which the keywords is used. The first quadrant represents “motor themes” that are well -developed both internally and externally as it is characterized by high density and centrality. [ 17 ]. Within the YouTube research, such themes include “user -generated content”, “new media”, “influencers”, and “gender.” The second one is usually labeled the “highly -developed -and -isolated themes” quadrant as it deals with niche themes. With high -density -low -centrality structure, this quadrant highlights the fact that while the themes it comprises are well -developed internally, they are marginally important externally. Within the YouTube research, such themes include “education,” “medical education”, and “technology.” The low -density -low -centrality third quadrant is termed the “emerging -or -declining themes” quadrant. This implies that the themes in this quadrant are characterized by weak ties at the internal and external levels. Such themes might indicate potential hotspots in YouTube research. Examples include “COVID -19”, “health communication” and “Twitter.” Finally, the “basic -and -transversal themes” quadrant (low density -high -centrality) comprises themes that are weakly developed in terms of internal ties. Nevertheless, they are characterized by important external ties. Within the YouTube research, such themes include “Social media” and “internet.”

YouTube research thematic/strategic map

4 Discussion

This study examined published research works related to YouTube between 2006 and 2021. At this point, we can answer the research questions. To answer the first research question about trends and directions, we found that between 2006 and 2008, there was a slow growth in publications since the YouTube platform was new. Then from 2008 to 2017, there was a rapid growth in research on YouTube. Afterwards, the trend is still upward with a slower pace. We also found that the trending topic changes over time. While “gaming” and “video sharing” were trending topics in some time period, the trend shifted towards topics like “COVID -19” and “misinformation”.

The second research question is related to the information discovered from YouTube research. We discovered the most cited papers, authors, and countries with highest number of publications. We also discovered the network between the published works. Specifically, the authors’ collaboration network, collaboration between institutions, and collaboration between countries. We also analyzed the collected works regarding the Bradford’s law and Lotka’s law. It was proved that large number of papers were published in a small group of journals, which followed the Bradford’s law. Also, it was proved that the frequency indexes of author productivity distribution followed Lotka’s law. Additionally, the MCA algorithm was used to find the conceptual structure map related to YouTube papers. The output shows three clusters, consumer -generated content, health and medical issues, and information quality.

Based on this paper’s results, large number of works are related to health and medical issues. Among the institutions, department of public health appeared more than other institutions. Additionally, the journal of medical internet research is in the third spot of the most relevant sources. The MCA algorithm dedicated one cluster for health and medical issues. Furthermore, “medical education” topic started trending in 2014 and is still trending, based on Fig. 15 , which is one of the longest trending topics. It is clear that researchers are interested in analyzing YouTube about health -related issues. These points coincide with studies on effectiveness of YouTube videos as a health educational platform. Allgaier mentioned that many people use YouTube as a source of information on science, technology, and health [ 3 ]. It is also assumed that because of the sensitivity of health and medical related issues, researchers focused more on the health aspect of the YouTube to find information and misinformation in videos. They analyzed videos and comments to understand users’ feedback on the health -related videos [ 59 ].

5 Limitations and future research

Despite the major contributions of this study, it suffers from some limitations. First, we relied only on the Scopus database to conduct our bibliometric analysis. Thus, we unavoidably commit a selection bias. Subsequently, we believe that future research should test the robustness of our finding by merging several databases such as WoS and Google Scholar. However, it has been argued that the Google Scholar database is less stringent as it comprises citations from unpublished manuscripts, blogs, etc. (Gavel & Iselid, 2008; [ 55 ]). Second, we limited the selection of documents to articles published in English. Thus, our results might be limited in terms of coverage [ 57 ]. Future research might add other languages to test the generalizability of our findings. Finally, although we conducted a comprehensive study on the whole domain of YouTube research, future research might focus on specific journals publishing YouTube research such as New Media and Society, Convergence, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Computers in Human Behaviour, and the Physics Teacher, among others.

6 Conclusion

This work conducted a bibliometric study on YouTube, as a research topic, in the literature between 2006 and 2021. The search in Scopus database resulted in 1781 research works, which were collected along their meta data such as authors name, keywork, etc. The collected data were analyzed, and the results were presented in the form of network of collaborations between authors, institutions, and countries. We also show the results of networks of keywords. We then created a thematic map based on the keywords to find the trending topic in research related to YouTube. The analysis revealed that 2006 -2007 were initial stage in YouTube research followed by 2008 -2017 which is the decade of rapid growth in YouTube research. The 2017 -2021 is considered the stage of consolidation and stabilization of this research topic. We also found that the trending topic changes over time. While “gaming” and “video sharing” were initially trending, the trend shifted towards topics like “COVID -19” and “misinformation”.

Abdi H, Valentin D (2007) Multiple correspondence analysis. Encycl Meas Stat 2(4):651–657

Google Scholar

Al-Khalifa H (2014) Scientometric assessment of Saudi publication productivity in computer science in the period of 1978-2012. Int J Web Inf Syst 10:194–208

Allgaier J (2019) Science and environmental communication on YouTube: strategically distorted Communications in Online Videos on climate change and climate engineering. Front Commun 4(36):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00036

Article Google Scholar

Aryadoust V, Ang B (Forthcoming) Exploring the frontiers of eye tracking research in language studies: A novel co-citation scientometric review. Comput Assist Lang Learn

Ávila-Robinson A, Wakabayashi N (2018) Changes in the structures and directions of destination management and marketing research: A bibliometric mapping study, 2005-2016. J Destin Mark Manag 10:101–111

Bakshy E, Hofman J, Mason W, Watts D (2011) Everyone’s an influencer. In: King I, Nejdl W, Li H (eds) Proceedings of the 4th ACM International conference on web search and data mining – WSDM’11. ACM Press, New York, p 65

Banckendorff P (2009) Themes and trends in Australian and New Zealand tourism research: A social network analysis of citations in two leading journals (1994-2007). J Hosp Tour Manag 16:1–15

Bonilla CA, Merigó JM, Torres-Abad C (2015) Economics in Latin America: a bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 105(2):1239–1252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1747-7

Bradford S (1934) Sources of information on specific subjects. Eng Illus Wkly J 137:85–86

Callon M, Courtial J, Laville F (1991) Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: the case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics 22:155–205

Chen X, Liu Y (2020) Visualization analysis of high-speed railway research based on CiteSpace. Transp Policy 85:1–17

Chen C, Song I, Yuan X, Zhang J (2008) The thematic and citation landscape of data and knowledge engineering (1985-2007). Data Knowl Eng 67:234–250

Chen C, Hu Z, Liu S, Tseng H (2012) Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin Biol Ther 12:593–608

Chen C, Dublin R, Kim M (2014) Orphan drugs and rare diseases: A scientometric review (2000-2014). Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2:709–724

Chen X, Zou D, Cheng G, Xie H (2020) Detecting latent topics and trends in educational technologies over four decades using structural topic modeling: A retrospective of all volumes of Computers & education. Comput Educ 151:103855

Chen X, Zou D, Xie H, Cheng G (2021) Twenty years of personalized language learning: topic modeling and knowledge mapping. Educ Technol Soc 24:205–222

Cobo M, Lopez-Herrera A, Herrera-Viedma E, Herrera F (2011) An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. J Inflametrics 5:146–166

Colicchia C, Creazza A, Noe C, Strozzi F (2019) Information sharing in supply chains: A review of risks and opportunities using the systematic literature network analysis (SLNA). Supply Chain Manag 24:5–21

Corbet S, Dowling M, Gao X, Huang S, Lucey B, Vigne S (2019) An analysis of the intellectual structure of research on financial economics of precious metals. Res Policy 63(101416):101416

Corte V, Gaudio G, Sepe F (2018) Ethical food and the kosher certification: A literature review. Br Food J 120:2270–2288

Ding Y (2011) Scientific collaboration and endorsement: network analysis of co-authorship and citation networks. J Inflamm 5:187–203

Dobusch L, Kapeller J (2012) A guide to paradigmatic self-marginalization: lessons for post-Keynesian economists. Rev Polit Econ 24:469–487

Elango B, Rajendran P (2012) Authorship trends and collaboration pattern in the marine sciences literature: A scientometric study. Int J Inf Dissem Technol 2:166–169

Findlay K, van Rensburg O (2018) Using interaction networks to map communities on twitter. Int J Mark Res 60:169–189

Firdaus A, Ab Razak M, Feizollah A, Hashem I, Hazim M, Anuar N (2019) The rise of “blockchain”: bibliometric analysis of blockchain study. Scientometrics 120:1289–1331

Gautam P, Maheshwari S, Kaushal-Deep SM, Bhat AR, Jaggi CK (2020) COVID-19: A bibliometric analysis and insights. Int J Math Eng Manag Sci 5(6):1156–1169

Glänzel W, Schubert A (2005) Analyzing scientific networks through co-authorship. In: Moed H, Glanzel W, Schmoch U (eds) Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Research: The Use of Publication and Patent Statistics in Studies of S&T Systems. Springer, Dordrecht

Glotzl F, Aigner E (2018) Orthodox core-heterodox periphery? Contrasting citation networks of economics departments in Vienna. Rev Polit Econ 30:210–240

Gonzales-Valiente C (2019) Redes de citación de revistas iberoamericanas de bibliotecología y ciencia de la información en Scopus. Bibliotecas Anales de Investigación 15:83–98

Hussein E, Juneja P, Mitra T (2020) Measuring misinformation in video search platforms: An audit study on YouTube. Proc ACM Human-Comput Interact 4(CSCW1):Article 048. https://doi.org/10.1145/3392854

Jiang Y, Ritchie B, Benckendorff P (2019) Bibliometric visualization: An application to tourism crisis and disaster research. Curr Issue Tour 22:1925–1957

Khan G, Wood J (2016) Knowledge networks of the information technology management domain: A social network analysis approach. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 39:367–397

Khasseh A, Soheili F, Moghaddam N, Chelak A (2017) Intellectual structure of knowledge in iMetrivs: A co-word analysis. Inf Process Manag 53:705–720

Khatri P, Singh SR, Belani NK, Yeong YL, Lohan R, Lim YW, Teo WZY (2020) YouTube as source of information on 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak: a cross sectional study of English and mandarin content. Travel Med Infect Dis 35:101636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101636

Knoke D, Yang S (2010) Social network analysis. SAGE, Los Angeles

Koseoglu M (2016) Mapping the institutional cpollaboration network of strategic management research: 1980-2014. Scientometrics 109:203–226

Kumar H, Dora M (2011) Citation analysis of doctoral dissertations at IIMA: A review of the local use of journals. Libr Collect Acquis Tech Serv 35:32–39

Kumar S, Kumar S (2008) Collaboration in research productivity in oil seed research institutes of India. Fourth International conference on webometrics, informatics and Scientometrics. Universitat zu Berlin, Institute for Library and Information Science, 1-18

Law J, Bauin S, Courtial J, Wittaker J (1988) Policy and the mapping of scientific change: A co-word analysis of research into environmental acidification. Scientometrics 14:251–264

Lee M, Chen T (2012) Revealing research themes and trends in knowledge management: from 1995 to 2010. Knowl-Based Syst 28:47–58

Li HO-Y, Bailey A, Huynh D, Chan J (2020) YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: a pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Glob Health 5(5):e002604. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604

Liao H, Tang M, Li Z, Lev B (2019a) Bibliometric analysis for highly cited papers in operations research and management science from 2008 to 2017 based on essential science indicators. Omega 88:228–236

Liao X, Yu Y, Li B, Li Z, Qin Z (2019b) A new payload partition strategy in color image steganography. IEEE Trans Circ Sys Video Technol 30(3):685–696

Liao X, Li K, Zhu X, Liu KR (2020a) Robust detection of image operator chain with two-stream convolutional neural network. IEEE J Sel Top Signal Process 14(5):955–968

Liao X, Yin J, Chen M, Qin Z (2020b) Adaptive payload distribution in multiple images steganography based on image texture features. IEEE Trans on Dependable Secure Comput 1

Liu J, Tian J, Kong X, Lee I, Xia F (2019) Two decades of information systems: a bibliometric review. Scientometrics 118(2):617–643

Luo J, Han H, Jia F, Dong H (2020) Agricultural Co-operatives in the western world: A bibliometric analysis. J Clean Prod 273:122945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122945

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook J (2001) Birds of feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 27:415–444

Merediz-Sola I, Bariviera A (2019) A bibliometric analysis of bitcoin scientific production. Res Int Bus Financ 50:294–305

Merigó JM, Yang J-B (2017) Accounting research: A bibliometric analysis. Aust Account Rev 27(1):71–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12109

Mostafa M (2015) Do products’ warning labels affect consumer safe behavior? A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. J Bus Econ Stud 22:24–39

Mostafa M (2016) Do consumers recall products’ warning labels? A meta-analysis. Int J Manag Mark Res 9:81–96

Mostafa M (2020) A knowledge domain visualization review of thirty years of halal food research: themes, trends, and knowledge structure. Trends Food Sci Technol 99:660–677

Neff M, Corley E (2009) 35 years and 160,000 articles: A bibliometric exploration of the evolution of ecology. Scientometrics 80:657–682

Neuhaus C, Neuhaus E, Asher A, Wrede C (2006) The depth and breadth of Google scholar: an empirical study. Libr Acad 6:127–141

Noruzi A (2017) YouTube in scientific research: A bibliometric analysis. Webology 14(1):1–7

Qian J, Law R, Wei J (2019) Knowledge mapping in travel website studies: A scientometric review. Scand J Hosp Tour 19:192–209

R Development Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna https://www.R-project.org

Teng S, Khong KW, Pahlevan Sharif S, Ahmed A (2020) YouTube video comments on healthy eating: descriptive and predictive analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill 6(4):e19618–e19618. https://doi.org/10.2196/19618

van Eck N, Waltman L (2014) CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. J Inf Secur 8:802–823

van Eck N, Waltman L (2019) VOSviewer, version 1.6.13

Vidgen R, Henneberg S, Naude P (2007) What sort of community is the European conference on information systems? A social network analysis 1993-2005. Eur J Inf Syst 22:317–335

Wetzstein A, Feisel E, Hartmann E, Benton W (Forthcoming) Uncovering the supplier selection knowledge structure: A systematic citation network analysis from 1991 to 2017. J Purch Supply Manag

Wong W, Mittas N, Arvanitou E, Li Y (2021) A bibliometric assessment of software engineering themes. Schools and institutions (2013-2020). J Syst Softw 180:111029

Zong Q, Shen H, Yuan Q, Hu X, Hou Z, Deng S (2013) Doctoral dissertations of library and information science in China: A co-word analysis. Scientometrics 94:781–799

Zou X, Yue W, Vu H (2018) Visualization and analysis of mapping knowledge domain of road safety. Accid Anal Prev 118:131–145

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Gulf University for Science and Technology, Mubarak Al-Abdullah, West Mishref, Kuwait

Mohamed M. Mostafa

Department of Computer System & Technology, Faculty of Computer Science & Information Technology, University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Ali Feizollah & Nor Badrul Anuar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohamed M. Mostafa .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mostafa, M.M., Feizollah, A. & Anuar, N.B. Fifteen years of YouTube scholarly research: knowledge structure, collaborative networks, and trending topics. Multimed Tools Appl 82 , 12423–12443 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-13908-7

Download citation

Received : 13 December 2021

Revised : 21 February 2022

Accepted : 12 September 2022

Published : 19 September 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-13908-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bibliometric analysis

- Co -citation networks

- Keyword co -occurrence networks

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Perspective article, how to succeed as an academic on youtube.

- College of Global Futures, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

More and more people are turning to YouTube to expand their knowledge, develop their understanding, and learn new skills. These “casual learners”—loosely defined as individuals who are curious about a topic and are self-motivated to learn more about it—are taking advantage of the ease with which nearly anyone with an internet connection, basic video skills, and something to say, can become a YouTube “creator.” However, amidst a dizzying array of videos purporting to educate or otherwise inform viewers, academic content-creators are notable by their lack of presence on the platform. Here, there are largely-untapped opportunities for academics to contribute to the richness, diversity and trustworthiness of video content available to casual learners, and to effectively mobilize their knowledge at scale. There is also a pressing need for diversity in casual learning content, including diversity in creator gender, identity, ethnicity, and perspective, and academics are uniquely positioned to address this need. Drawing on the author's experiences in developing and producing the YouTube channel Risk Bites, this perspective explores how time, resource, and even talent-limited academics can nevertheless leverage YouTube as a platform for further mobilizing their knowledge for public good.

Introduction

Since its launch in 2005, YouTube has emerged as a versatile educational platform ( Sherer and Shea, 2011 ; Snelson, 2011 ) and perhaps one of the most influential online platforms for casual (or informal online) learning ( Duffy, 2008 ; Brossard and Scheufele, 2013 ; Maynard, 2016 , 2017 ; Welbourne and Grant, 2016 ). Despite this, academic experts have struggled to make effective use of YouTube and similar platforms for effective and impactful knowledge mobilization, in spite of growing expectations that research and scholarship are connected more effectively to socially relevant issues and outcomes. This seeming-disconnect between holders of knowledge within academia, and consumers of knowledge (or what masquerades as knowledge) on YouTube, has long intrigued me as a university professor and science communicator—so much so that, in 2012, I set out to explore how academic experts with little to no institutional support can effectively utilize the platform in providing YouTube users with accessible and engaging content that represents the cutting edge of current knowledge. The result was the YouTube channel Risk Bites 1 , and 8 years of learning the hard way what works and what doesn't as an academic who also aspires to be a YouTube content creator.

In setting out on this journey, I was particularly interested in how individuals with no institutional support or communication-specific funding, but with a passion for making their knowledge accessible and useful to others, could effectively use YouTube as a casual learning platform—where casual learners are loosely defined as individuals who are curious about a topic and are self-motivated to learn more about it ( Maynard, 2016 ).

Sadly, effective public communication as a social good remains under resourced in many academic institutions, and one consequence of this is that academics who take such a role seriously often need to resort to modes of communication that they can squeeze between the cracks in a profession that is extremely demanding of their time and attention. Within this context, I set out to better understand as a practitioner how time-constrained academics interested in public education/communication could leverage the opportunities afforded by YouTube to reach wider audiences and engage in effective knowledge mobilization at scale.

This paper draws on that journey as it provides a personal perspective on the opportunities and challenges that the democratization of online video-based communication and education opens up to independent academic experts. In doing so, it considers ways in which academics may succeed as YouTube “stars”—not in the conventional sense of online stardom, but in the sense of effectively mobilizing their knowledge for online audiences, and making it accessible to casual learners in a form that is relevant, impactful, and scalable.

Why Youtube?

Over the past several years, the ways people learn and the various roles of learning in society, have been undergoing a number of transformations ( Brown and Adler, 2008 ; Thomas and Brown, 2011 , 2012 ; Peters et al., 2014 ). In particular, the emergence of new technologies, shifts in social systems, norms and expectations, and the continuing march of automation, are together calling into question how we learn and what we learn. One consequence of this has been a growing shift toward online informal self-directed, or casual, learning, where users actively seek out the knowledge they are interested in ( Song and Bonk, 2016 ; Welbourne and Grant, 2016 ; Peters and Romero, 2019 ). This form of learning is endemic within generations who have grown up with Google and near-ubiquitous internet access, and where information (although not necessarily knowledge) is often a mere search box or smart-speaker query away.

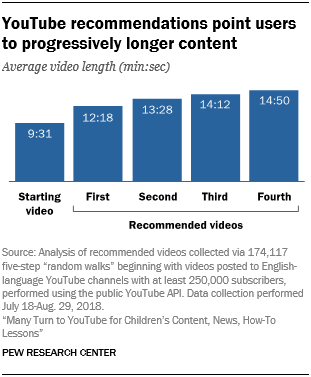

Within this casual learning environment, YouTube has arisen as one of the most widely used platforms for informally acquiring new skills and knowledge. The platform is purportedly the largest search engine in the world after Google, 2 and is increasingly a go-to platform for learning specific skills. It's where casual learners turn if they want to know how to mend a leaking toilet, or try a new hairstyle, or bake bread, learn to paint landscapes, ace an interview, or master a myriad other practical techniques. But it is also where a growing number of users are turning to expand their understanding and to learn more broadly. As a result, there is a growing breadth and depth of knowledge-content on YouTube that dives deep into areas such as mathematics, philosophy, history, and science (social as well as natural), and that provides casual learners with access to material that was previously confined to academic books, peer review papers, and tuition-based college and university classes.

This content is being spurred on by a growing global desire for learning that is not being met through conventional channels, and that is reflected in the popularity of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) ( Breslow et al., 2013 ) and movements, such as TED (Technology, Entertainment, and Design) ( Sugimoto and Thelwall, 2013 ). This is a desire that, I suspect, is being stimulated in part by living in a world of rapidly changing technological capabilities and social norms, where conventional educational platforms are not keeping up with the need for agility in developing new skills and understanding. But it also reflects the natural curiosity and innate desire to learn that many of us possess. Here, YouTube is enabling people to satisfy this curiosity on their own terms, without the constraints imposed by formal educational establishments.

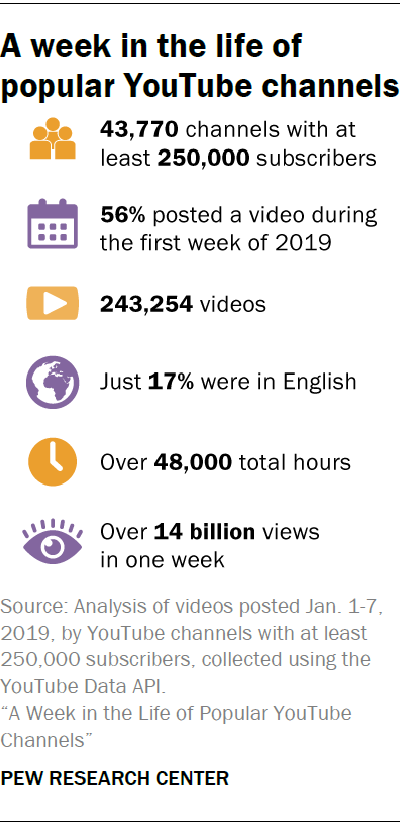

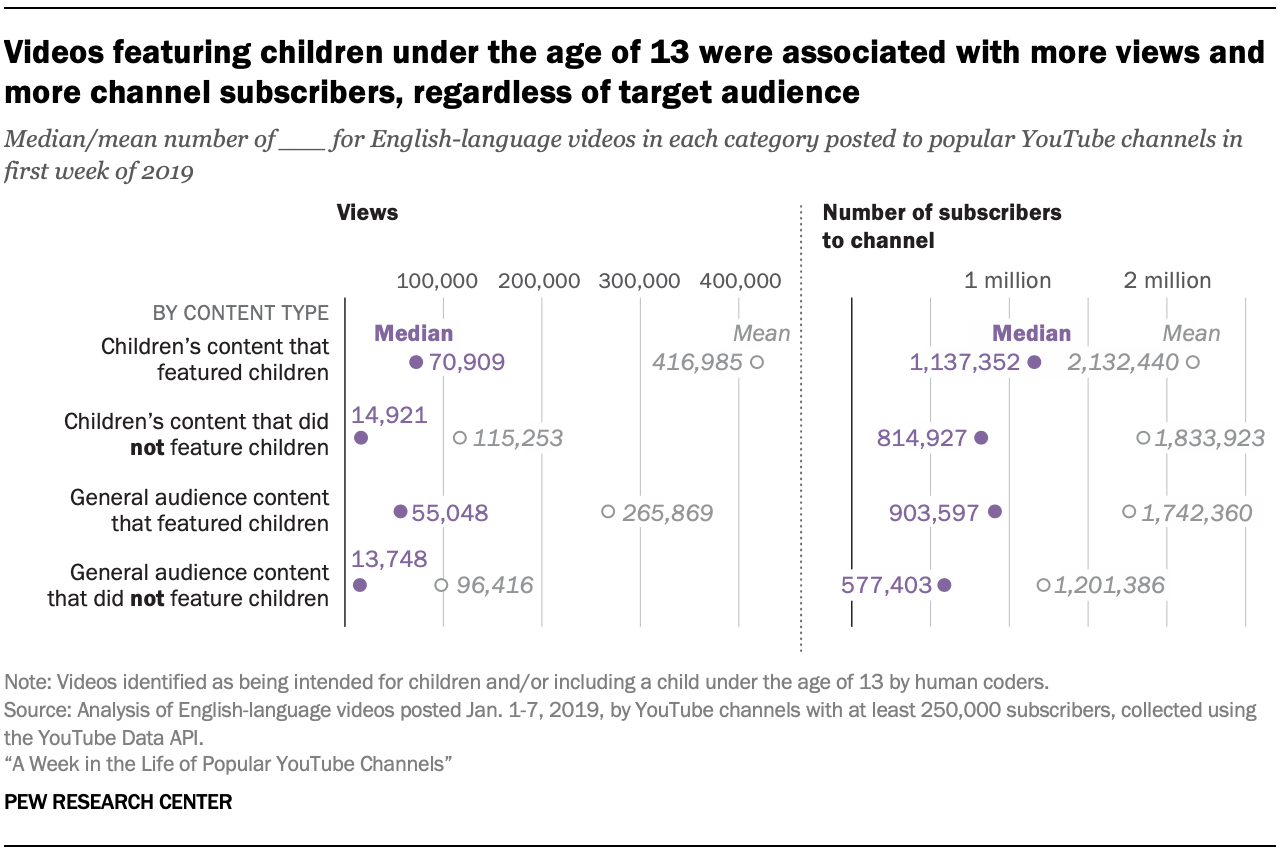

Perhaps reflecting this, YouTube reportedly has over 2 billion users who watch over a billion hours of video each day, 3 and according to the Pew Research Center, it continues to be the most widely used online platform in the US, with 81% of 15–25 years old and 73% of adults claiming to use it at some time ( Perrin and Anderson, 2019 ). Of course, many YouTube users will be looking for content that is entertaining, and that is associated with and reinforces their online social community and identity. Of these, only a relatively small subset of users are likely to be explicitly seeking educational content. Yet the very nature of casual learning blurs the lines between how content is defined, meaning that many YouTube users are likely learning from a broad diversity of video types, styles and genres, irrespective of how content creators or researchers categorize them.

Within this online learning environment, a number of educational content creators have become highly successful in terms of video views and the numbers of people subscribing to their channels. For example, at the time of writing, Minute Physics 4 —an early trend-setter in science content on YouTube—has over 5 million subscribers and over 440 million views. Vsauce 5 —another early pioneer in casual learning-oriented content—has close to 16 million subscribers, and over 1.8 billion views. CrashCourse 6 —a learning channel launched by Hank and John Green in 2012—has nearly 11 million subscribers, and over 1.2 billion views. And Khan Academy 7 —an early leader in simple video-based educational instruction—has over 5.7 million subscribers and 1.7 billion views.

The learning-reach implied by these numbers is substantial, and these are just a few of the many YouTube channels that combine sought-after educational content with views in the millions or billions. These figures attest to a deep interest amongst users for educational content, and the potential for educational channels on YouTube to reach large numbers of casual learners. And yet, while many of these channels are produced by experts, or draw on the knowledge of experts, very few are produced by individual academics as part of their public communication and/or knowledge mobilization efforts. Even at substantially lower levels of reach and engagement (such as YouTube channels with thousands of subscribers and tens of thousands of views) successful academic content creators are hard to find.

This is problematic, both with respect to the implications for how much knowledge residing in academia that is not being mobilized and contributing to social value creation through YouTube, and in terms of the quality and trustworthiness of content that is, in turn, filling the resulting vacuum.

On this latter point, there is rising concern around the use of YouTube and other social media platforms to promote false and misleading information ( Briones et al., 2012 ; Donzelli et al., 2018 ; Allgaier, 2019 ; Scheufele and Krause, 2019 ; Ahmed et al., 2020 ). And the reality is that, as online platforms continue to enable a rapid scaling of one-to-many communication that is independent of the validity or trustworthiness of the content, there is a growing danger around potentially harmful misinformation propagating through society. Yet this only serves to emphasize the importance of academics developing the skills and abilities to act as counterweights to misleading and mischievous content masquerading as authoritative educational material.

Of course, many prominent educational channels on YouTube provide exceptionally high-quality content that is expertly crafted by professionals for the audiences they serve. And it would be naïve to assume that individual academic content creators could and should aspire to compete with them on the same grounds—especially as they have many other commitments on their time and attention to balance. And yet, despite the presence of these professional education channels, YouTube remains rife with poor and misleading content that is returned in searches by casual learners, and that is challenging for them to sift through.

In addition to the tension between accurate and informative vs. inaccurate and misleading information, there are also gaps in YouTube content where leading educational creators simply do not have the time or the impetus to produce the diversity of material that casual learners are looking for. This is exacerbated by successful content creators often pursuing business models that are based on ad-revenues which are, in turn, driven by user views. And while this is a model that can and does support high quality content, it is also one that prioritizes popular content over useful content.

The result is a landscape of authoritative, accessible and informative content for casual learners on YouTube that is far from comprehensive, and a community of professional content-producers who, despite their best efforts, are unable to meet the needs of users—especially in niche areas. And it was this gap between content-production and content-demand that got me asking in 2012 what it might take for academic content-creators to become increasingly successful in using YouTube for knowledge mobilization, and what might define success in this context.

Prior to 2011, I had relatively little interest in YouTube. As well as being a professor at a research university, I was an active science communicator, writing and talking widely about the responsible development and use of nanotechnologies and other emerging technologies. And I'd occasionally used the platform to post-videos relevant to my work. But it wasn't until my then-teenage daughter and son introduced me to how some communities were using YouTube that I began to explore more deeply how it might be utilized by academics with an interest in public education and communication.

In July 2011, my daughter and son persuaded me to accompany them to VidCon—an annual convention dedicated to online video that was originally conceived by the authors and YouTube creators John and Hank Green. At the time, my daughter was a member of an international YouTube collaborative channel, and deeply engaged with the online community fostered by the Green brothers.

This was the second year the convention had been held, and it was still small and informal enough for top YouTube creators to mix and engage relatively freely with their fans. At the start of the convention, I was mildly curious about what was happening with YouTube around science communication and education. But by the end of it, I was convinced that this was a platform that offered academic content creators a unique opportunity to make what they know accessible to others—and the seeds for the educational channel Risk Bites were sown.

Under the curation of John and Hank Green, VidCon 2011 had a strong focus on educational content creators. This is where I was introduced to a foundational community of creators who had either set out to make educational content that was highly accessible and engaging (such as Derek Muller and Veritasium, 8 and Henry Reich and Minute Physics), or had morphed into educational content (such as the channel Vsauce). What struck me most though was the combination of authenticity and simplicity that many of these creators represented, together with an ability to reach hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of viewers. Using the simplest of methods—at least on the surface—creators, such as Henry Reich, Vi Hart, 9 and others were demonstrating that, equipped with a video camera, whiteboard (or sheet of paper) and a handful of pens, anyone with knowledge to share and some patience could become a successful YouTube creator.

Of course, it wasn't quite this simple. But after the convention, I was intrigued by whether someone like myself—an academic with deep expertise in risk, emerging technologies and responsible innovation, but little creative talent, less time, and no training—could also leverage the platform as a way of making accessible what I knew to others.

My motivation here was 3-fold. As a science communicator, I was interested in better-understanding how YouTube could be used for user-centric communication, where viewers are the arbiters of what is worth their time to watch. As an educator, I was intrigued with the potential to make what I taught inside relatively small limited-access classrooms publicly accessible at scale, to thousands, or even tens of thousands of YouTube users. And as an academic, I wanted to know if it was possible to develop a video creation process that would empower people in a similar position to myself to make their knowledge freely accessible to others within the constraints of having little time or perceived ability, and often with little to no institutional support.

The result was the channel Risk Bites, 10 which soft-launched in July 2012, and formally launched in November the same year.

Video Content-Creation for Time and Talent-Limited Academics

Given my lack of time, resources, and talent as a video-creator, Risk Bites was designed and developed around a concept that worked within these limitations to produce content that was engaging, informative, and useful. Drawing on my work around risk (which spans conventional risk assessment to the potential risks of emerging technologies and novel approaches to value protection and creation 11 ), the channel focused (and still does) on making the science of risk engaging, accessible and useful to a broad audience. Within this, a style was developed that was loosely based on the simple drawings of Minute Physics and the screen-drawings used by Kahn Academy, and was modulated by my limited skills with a whiteboard, which consisted of the simplest possible stick figures, geometric shapes, and the occasional written word.

Given the constraints of time, ability and resources, a workflow was developed that was designed to support the effective production of videos that appealed to viewers despite their obvious limitations. Here, four factors were paramount: developing content built on a highly professional foundation, even where the results appeared somewhat informal; building videos around a tightly focused and constructed script that is easy to follow, engaging and as jargon-free as possible; ensuring the narration and audio quality were as high as could be achieved with available resources; and staying true to my personality, perspectives and interests as an expert and creator.

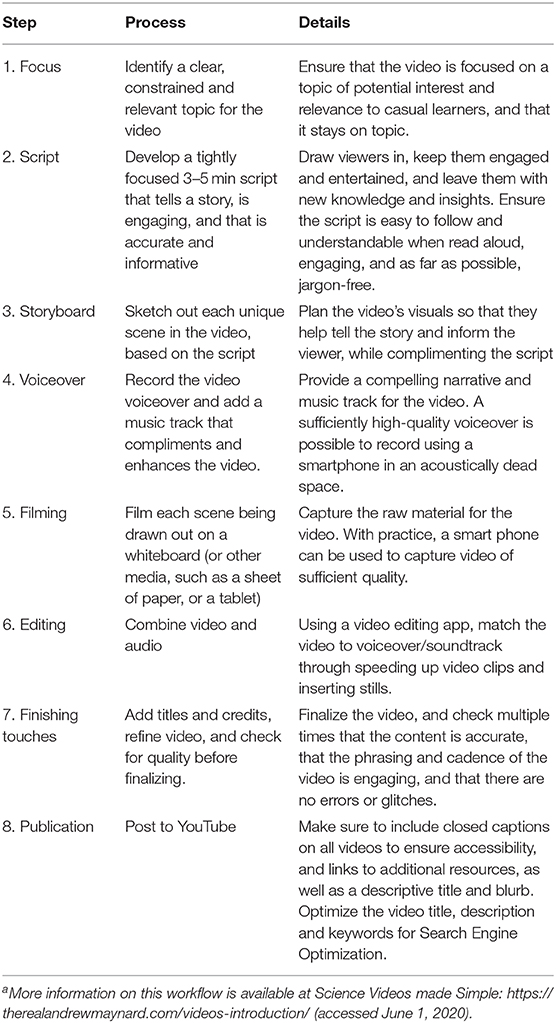

These factors were codified into a workflow for producing tightly-scripted 3–5 min videos that continues to underpin the channel's content, and which is outlined in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Workflow followed for Risk Bites from the initial idea to the final video a .

With some practice, this workflow enabled the production of a ~3–5 min video with around 10–15 h effort, that reflected my expertise and was relevant and accessible to a wide audience. It also allowed for the rapid production of highly-responsive videos where there was an emerging need. For instance, it took around 12 h from initial concept to publication for the 2014 video “5 Things Worth Knowing about Ebola.” 12 And somewhat uniquely, it enabled the production of videos that reflect nuances and subtleties in expertise and insight which are common in the classroom, but hard to replicate by video producers who are not also domain experts.

By utilizing this workflow and taking advantage of the simplicity of whiteboard-style videos, Risk Bites has developed into a niche YouTube channel that is effective at reaching specific audiences. At the time of writing, the channel has over 15,400 subscribers and 100 public videos that have been watched over 2.6 million times, with aggregated channel videos being watched nearly 100 h per day on average. 13 These numbers are not high compared to the top science channels on YouTube. But for a channel produced as a side-project by a full-time academic, they represent a substantial reach.

This reach becomes more apparent when watch-time is compared to in-class face-time with students. 100 h is roughly equivalent to individual student-instructor face-time associated with teaching seven students in a one-credit course over a semester (assuming a 15-weeks semester). In other words, each day, Risk Bites videos have a similar reach to a small semester-long class. By this metric, 100 h per day of YouTube watch-time over 15 weeks is similar to the student-instructor face-time associated with teaching 105 such courses over a semester, or teaching 735 students in a one-credit course or 245 students in a 3-credit course.

Of course, these comparisons are flawed, as class-based teaching involves far more than face to face lecturing (or equivalent). And unlike education within a structured learning environment, there is no clear association with YouTube videos between watch-time and measurable learning with respect to specific learning objectives. To complicate matters further, watch-time is not associated with the number of users who view videos in their entirety (many videos are only watched for a fraction of their duration). Yet despite this, the comparisons serve as a crude yet useful indicator of the potential reach and impact of even a relatively modest YouTube channel.

Useful as video views and watch-time are in indicating reach and impact though, it's also helpful to gain insights into who is engaging with content, and how it is relevant to them. Here, subjective indicators of success used by Risk Bites have included requests for permission to use videos as an education or training resource, and requests for new videos (or collaborations) addressing specific topics.

Since the channel's formation, a number of its videos have been used as class resources around the world, or by media outlets to explain complex topics. These uses are not always reflected in YouTube analytics, and so are sometimes hard to track. But where they can be, they help indicate the value, utility and reach of the channel's content.

Video collaborations, and requests for videos on specific topics, further establish the value of the channel to others. Since its launch, over 20% of videos produced have involved collaborations of one form or another. For example, the video “TOX21: A New Way to Evaluate Chemical Safety and assess risk” 14 was produced at the request of the International Life Science Institute North America (ILSI NA—an organization which I am affiliated with) and with collaborators from the US Environmental Protection Agency, and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). And the video “What Does ‘Probably Causes Cancer' Mean?” 15 was a collaboration with the online environmental magazine Grist. More recently, “A social distancing guide for students living with coronavirus” 16 came out of a collaboration with two prominent public health experts. And in 2017, the Swiss National Science Foundation supported a series of videos on nanotechnology research that were directly inspired by Risk Bites. 17 These and other collaborative videos indicate a level of recognition for the relevance and impact of the channel that transcends metrics, such as views and aggregated view time.

A more quantitative metric that is also indicative of engagement—although one that is not straight forward to interpret—is the average percentage of each video that is viewed. Anecdotally, many YouTube videos show a sharp drop-off in viewer-retention by the half-way point with (a phenomenon borne out on Risk Bites). While this leads to a rather subjective metric of engagement, videos with a low average percentage of video viewed may be considered to be poorly successful in engaging their audience, while those with a high average percentage of video viewed may be considered to be reasonably successful. However, the percentages that delineate high/low success are not well-defined. While there are no hard and fast rules here, and a paucity of related quantitative studies, a general rule of thumb is that videos which lose most viewers in the first few seconds are not particularly effective, while that those which have average percentage views above 60–70% are good performers. Videos with an average percentage view duration around 50% are often considered to be adequate performers ( Lang, 2013 ).

Average percentage view duration is commonly used in the context of video optimization with respect to monetization, where sustained viewing increases the potential of revenue from ads. However, it is also useful for assessing and, where necessary, increasing engagement levels amongst casual learners. As with most YouTube channels, the range of average percentage view duration on Risk Bites is wide. Between May 7–June 3 2020 for instance, amongst the 50 most-watched videos, the top average percentage view duration was 82% and the lowest was 12%, with both the mean and the median sitting at 54%. This suggests a reasonable level of engagement across the channel, and the presence of some videos that are engaging viewers to a high degree. But it also indicates that there is scope for creating content that is more successful in retaining the attention of viewers—although as creators have little control over who watches their videos, there will always be a percentage of viewers who quickly realize a video isn't for them.

Beyond average percentage view duration, another metric has emerged over the course of working on Risk Bites that is partially quantifiable, and perhaps provides an even greater indication of video alignment with casual learner interests: YouTube search rank. This, it should be noted, is an unreliable metric, as the YouTube search algorithm is opaque, dynamic, and context-dependent. Yet within these limitations, videos that are within the top ten YouTube search results for given keywords and phrases are more likely to be reaching and serving their target audience.

For the past few years, the success of Risk Bites videos has increasingly been assessed by their YouTube search ranking for keywords and phrases associated with their content, and videos have been actively optimized to increase their search rank. This has typically been carried out with the aid of a video optimization plugin, such as VidIQ that helps guide search engine optimization (SEO). Here, search ranking has proved to be a useful tool for assessing the degree to which videos are potentially reaching target audiences, and has indicated a number of notable successes.

For example, the video “What is Nanotechnology” posted in 2016, 18 is one of the top videos returned in the US for YouTube searches for “nanotechnology,” “what is nanotechnology,” or “nanotechnology risks.” “Hazard and Risk – What's the difference?” (2014) 19 is likewise in the top returned items for searches on “hazard vs risk” and “hazard and risk.” And “Ten risks presented by Artificial Intelligence” (2018) 20 is amongst the top videos returned on a search for “AI risk” or “Ethical AI.”

This focus on search rank for keywords and phrases, rather than absolute views and watch-time, helps refocus efforts on meeting the needs and interests of particular communities of casual learners, rather than competing against channels that are geared toward optimizing views and advertising revenue. Here, it is worth noting that, while the first two videos cited above have relatively high numbers of views for an academic-creator channel (574,000 for nanotechnology, and 130,000 for hazard and risk), the third does not (19,000 views)—despite clearly meeting an area of interest amongst a subset of YouTube users.

Search rank can, of course, be misleading. As well as being context-dependent, it is time-dependent, and an initially successful video may drop in rank as it gets older (although constant attention to SEO can help alleviate this). Yet it remains a useful metric nevertheless for academic content-creators who are looking for indications of whether their videos are having a justifiable impact.

Lessons Learned

Looking back over the past 8 years of producing Risk Bites, perhaps the greatest personal lesson has been that it is not only possible for time and talent-limited academics to be successful on YouTube—as long as appropriate metrics of success are used—but that there is an urgent and growing need for more content creators in this domain. I was curious though as to whether my perspective aligned with that of more successful professional YouTube creators serving casual learners. And so I reached out to Hank Green, co-founder of the channels CrashCourse and SciShow and the production company Complexly, and a leading producer of YouTube science content, to get his sense of the opportunities that YouTube provides academic content-creators, and in particular whether the platform is simply too dominated by professional producers these days for academics to be able to thrive on it.

Green's perspective aligned with my own experiences: he was clear that there remains plenty of space “for higher-level content that explains things people need to know for work or education… and whether that content is going to be self-sustaining through advertising (it almost definitely won't be) is a completely different question than whether it will improve people's education and provide opportunities for the career of the creator” (Hank Green, personal communication).