The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Before discussing any phenomenon or event, it is of crucial importance to identify the major factors, which contributed to it. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights should be analyzed within the context of the political, cultural, and religious situation, emerging in the middle of the twentieth century. As it is widely known, this act was adopted in 1948. According to this document, every person (or it would be better to say human beings) must be entitled to certain rights, which cannot take away from him or her (Weiss, 14).

At first glance, it may seem that this act should have been readily accepted by every nation; however, one should take into account that the Declaration of Human Rights was not received unanimously by all nations. For instance, representatives of some Islamic countries subjected it to heavy criticism. They stated that religious and cultural traditions were overlooked in this document (Ramcharan, 43).

The question arises of what prompted the United Nations Organization to develop and adopt this act. It stands to reason that first of all this declaration was the natural response to the events of World War II (genocide, violations of Genève convention, atomic explosion), which had proved that human rights could be easily violated even in the most developed countries. In addition to that, it became apparent that the international community did not come to a consensus about such a concept as “human rights”. As it has been pointed out earlier, Western and Eastern interpretations did not exactly coincide; therefore, some unification had to be achieved.

In this respect, we should explore the political situation in the Post-War period. Humankind was on the verge of a new conflict, the Cold War, but at that moment, the contradictions between the United States and the Soviets were not so aggravated, and both sides of the argument supported the idea of such declaration.

Regarding the religious environment, we should first say that the twentieth century is marked by a religious crisis, which means that to some extent, religion ceased to act as guidelines for people (the events of World War II eloquently substantiated this statement). Consequently, it was necessary to lay legal foundations, which were to ensure that at least basic human rights were preserved and protected (Asbeck,88). Naturally, we should not make generalizations because the religious crisis did not strongly affect Islamic countries but it was very tangible in Europe.

The events of World War II also showed that many people were not able to practice their religion. They were officially (or unofficially) prohibited to do it. In theory, the Declaration of Hunan guarantees that every person has religious freedom but it could not eradicate certain tacit laws, which still acted against some religious groups (Weiss, 134).

Furthermore, while analyzing the history of the twentieth century, scholars often attach primary importance to the so-called clash of cultures. At that moment, Easter and Western Worlds were only beginning to interact with each other but it was obvious that such notion as “human rights” was perceived in different ways. Partly, this declaration was aimed at strengthening the ties between the two most basic cultures or at least ensuring that they could efficiently cooperate (Ramcharan, 65).

New social developments also contributed to the adoption of this document. For instance, the growth of the feminist movement indicated that the roles of men and women should be reconsidered especially in terms of employment policies, and education. The adoption of the Declaration aroused a storm of protest in some Islamic countries because social equality of both sexes contradicted some tenants of the Muslim religion, especially regarding the role of women in the family and their dependence on their husbands.

In her book “A World Made New” Mary Glendon gives the reader insights into the atmosphere of that time. The author focuses on the role of Eleanor Roosevelt in developing this document. She was a member of the Human Rights Commission along with representatives of other countries. People, who were designated to draft this document, had to fight against insuperable odds, namely cultural-political, religious, and social controversies. It should be mentioned that even now this document is viewed as pro-Western and pro-American, though it seems its basic principles are universally applicable (Glendon, 33).

Nevertheless, the most important problem that Human Rights Commission had to resolve is how to make this doctrine applicable, in other words, whether this document had any legal force. Johannes Morsink in his book “The Declaration of Human Rights” argues that this legislative act was fully implemented only in the West; however, it did not become applicable in some other countries for example, in the USSR (Morsink, 8).

Thus, having analyzed political, religious, cultural, and cultural environment in the post-War Period we can arrive at the following conclusions: first Human rights commission had to resolve cross-cultural contradictions while drafting the declaration, especially different perceptions of human rights in the Western and Eastern cultures. However, the main problem that had to be resolved was the applicability of this legislative act. It seems that even now this issue remains very stressful because some countries only officially accepted the Declaration of Human Rights but even they do not follow its basic principles.

Bibliography

B. G. Ramcharan.Thirty Years After the Universal Declaration. BRILL, 1979.

Frederik Mari Asbeck. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Its Johannes Predecessors (1679-1948): And Its Predecessors (1679-1948). Brill Archive, 1949.

Morsink. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.

Mary Ann Glendon. “A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” Random House, 2002.

Thomas George Weiss. “The United Nations and Changing World Politics” Westview Press, 2004.

- “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen” and “Declaration of the rights of woman and the female citizen”

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Postwar Change in American Society

- T he Role of Confidentiality in Psychometric and Educational Testing

- Twin Peaks and Misogyny

- Individual Rights vs. Public Order

- Summary of "Smokers Get a Raw Deal" by Stanley Scott

- Is Human Life Valuable Today?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, October 23). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universal-declaration-of-human-rights/

"The Universal Declaration of Human Rights." IvyPanda , 23 Oct. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-universal-declaration-of-human-rights/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The Universal Declaration of Human Rights'. 23 October.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights." October 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universal-declaration-of-human-rights/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights." October 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universal-declaration-of-human-rights/.

IvyPanda . "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights." October 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universal-declaration-of-human-rights/.

- Increase Font Size

2 Human Rights and the Charter of the United Nations

Dr. Vesselin Popovski

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter, readers should know and understand:

- The context in which human rights provisions in the UN Charter must be read

- The concepts of universality, inalienability, indivisibility, equality and non-discrimination of human rights.

- The specific UN Charter articles that contain human rights provisions and the obligations of member states to comply with these provisions.

Human Rights and the UN Charter

This module introduces readers to the concept of human rights, based on universality, inalienability, indivisibility, interdependence, equality and non-discrimination. It explores the provisions of the UN Charter that explicitly refer to human rights and the roles that they play in promoting international co-operation. Human rights are a concern in all parts of the world and it is important that we study the provisions in the UN Charter that seek to promote and protect these rights and bring about greater international collaboration.

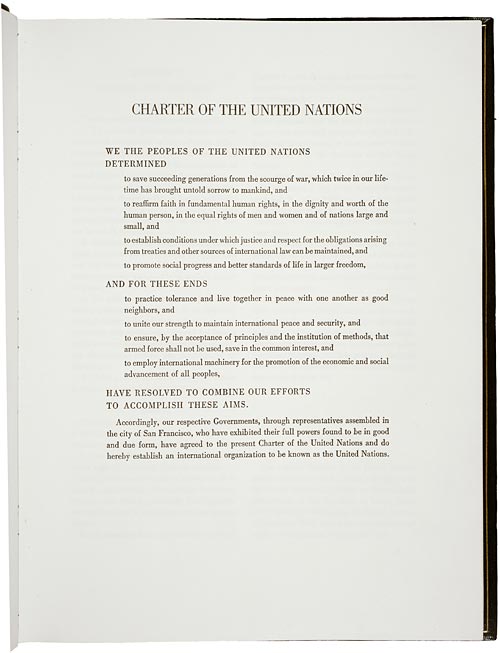

The Charter of the United Nations was signed on 26 June 1945, in San Francisco, at the conclusion of the United Nations Conference on International Organization, and came into force on 24 October 1945. Human Rights, since the inception of the United Nations, have been an important part of its purposes, ideals and functions. Human rights are mentioned as early as in the Preamble of the UN Charter of the United Nations, emphasizing that the UN Organization seeks “to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small” and “to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom”.

The Charter’s operative part contains six articles with explicit references to human rights, making the subject one of the central themes of the legal instrument. In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights brought human rights into the realm of international law. Since then, the Organization has diligently protected and promoted human rights through legal instruments and on-the-ground activities.

What are Human Rights?

Human rights are rights inherent to all human beings, whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language, or any other status. We are all equally entitled to our human rights without discrimination. These rights are all interrelated, interdependent and indivisible.

Universal human rights are often expressed and guaranteed by law, in the forms of treaties, customary international law, general principles and other sources of international law. International human rights law lays down obligations of Governments to act in certain ways or to refrain from certain acts, in order to promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms of individuals or groups.

Universal and inalienable

The principle of universality of human rights is the cornerstone of international human rights law. This principle, as first emphasized in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights in 1948, has been reiterated in numerous international human rights conventions, declarations and resolutions. The 1993 Vienna World Conference on Human Rights, for example, noted that it is the duty of States to promote and protect all human rights and fundamental freedoms, regardless of their political, economic and cultural systems.

All States have ratified at least one, and 80% of States have ratified four or more, of the core human rights treaties, reflecting consent of States which creates legal obligations for them and giving concrete expression to universality. Some fundamental human rights norms enjoy universal protection by customary international law across all boundaries and civilizations.

Human rights are inalienable. They should not be taken away, except in specific situations and according to due process. For example, the right to liberty may be restricted if a person is found guilty of a crime by a court of law.

Interdependent and indivisible

All human rights are indivisible, whether they are civil and political rights, such as the right to life, equality before the law and freedom of expression; economic, social and cultural rights, such as the rights to work, social security and education, or collective rights, such as the rights to development and self-determination, are indivisible, interrelated and interdependent. The improvement of one right facilitates advancement of the others. Likewise, the deprivation of one right adversely affects the others.

Equal and non-discriminatory

Non-discrimination is a cross-cutting principle in international human rights law. The principle is present in all the major human rights treaties and provides the central theme of some of international human rights conventions such as the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

The principle applies to everyone in relation to all human rights and freedoms and it prohibits discrimination on the basis of a list of non-exhaustive categories such as sex, race, colour and so on. The principle of non-discrimination is complemented by the principle of equality, as stated in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

Both Rights and Obligations

Human rights entail both rights and obligations. States assume obligations and duties under international law to respect, to protect and to fulfil human rights. The obligation to respect means that States must refrain from interfering with or curtailing the enjoyment of human rights. The obligation to protect requires States to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses. The obligation to fulfil means that States must take positive action to facilitate the enjoyment of basic human rights. At the individual level, while we are entitled our human rights, we should also respect the human rights of others.

Human Rights in the UN Charter

It has been noted by several commentators that the Charter is unsatisfactory as regards its human rights provisions, because it nowhere specifies these rights. For the representatives of the fifty governments who met in San Francisco in 1945 to write and sign the Charter, like the parliamentarians in the signatory states who ratified it – indeed, like most people in civilized countries – did share a common understanding of what were the most basic human rights, broadly defined. So nobody could say in good faith in San Francisco or in the United Nations that, as the Charter did not specify any human rights.

The provisions of promotion of human rights are present in article 1(3), part IX and article 76(c) of the UN Charter.

According to Article 1(3), one of the purposes of the United Nations is

“to achieve international co-operation…in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

It is self-evident that the Organization is obliged to pursue and try to realize its purposes. At the San Francisco gathering the chairman of the United States delegation Secretary of State Edward Stettinius expressed the sense of the Conference when he stated that the purposes listed in Article 1 of the Charter “are binding on the Organization, its organs and its agencies, indicating the direction their activities should take and the limitations within which their activities should proceed.”

Article 1(3) may be compared with a similar provision in Article 55:

With a view to the creation of conditions of stability and well-being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, the United Nations shall promote:

c) universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.

Under Article 55(c), the United Nations is obliged to promote a certain end which is essentially identical with the end which, under Article 1(3), the Organization is obliged to promote and encourage by achieving international co-operation. In fact the two articles are more similar in meaning than they may appear. On a superficial reading, the obligation imposed on the United Nations by Article 1(3) relates to the achievement of international co-operation for the purpose of promoting respect for human rights, whereas the obligation imposed by 55(c) relates directly to the promotion of this end itself.

These two articles may now be compared with Article 76, which states “the basic objectives of the trusteeship system, in accordance with the Purposes of the United Nations laid down in Article 1.” These objectives include:

c) to encourage respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion…

Objective (c) concerns the encouragement of a certain end which is identical with the end referred to in Article 1(3), and also is essentially identical with that in Article 55(c). By Article 76(c) the United Nations, under whose authority the trusteeship system functions, is obliged to encourage the realization of this end.

The weightage given to Human Rights by the Charter is high considering that there is a repetition of the aims and means to attain the aim in various articles of the Charter and the Preamble.

Obligations by Member nations to comply with the Human Rights provisions in the UN Charter

Granted that the United Nations is obliged by its own Charter to pursue the purpose or objective of promoting and encouraging respect for human rights, what obligation does this fact impose on the Member States ? A general kind of understanding of the matter may be achieved by considering certain provisions in Article 2 of the Charter. The article begins with the words: “The Organization and its Members, in pursuit of the Purposes stated in Article 1, shall act in accordance with the following Principles” – and proceeds to specify seven principles. In the present connection, the most significant of the principles are the following:

- All Members, in order to ensure to all of them the rights and benefits resulting from membership, shall fulfill in good faith the obligations assumed by them in accordance with the present Charter.

- All Members shall give the United Nations every assistance in any action it takes in accordance with the present Charter…

- Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state…

It may be argued that paragraph (2) merely affirms the Members’ general obligation to fulfil their various obligations under the Charter – which is tautological and superfluous. However, it is important to point out that the principle expressed in the paragraph is linked to, and must be read in conjunction with, the introductory words which refer to the purposes of the United Nations. The underlying idea is that the United Nations’ purposes, or rather the requirement and duty of the Organization to pursue them, imply for all the Members certain relevant obligations. What obligations? A general sort of answer is suggested by paragraph (5), namely: obligations in the form of giving assistance to whatever the Organization does in pursuit of its purposes. This must be taken to mean that Member States ought not only to refrain from obstructing the efforts of the Organization, but also to participate actively in these efforts. If Member States merely refrained from being obstructive, but they never did anything positive in connection with the purposes of the Organization, nothing much would ever be achieved. It follows, then, that the obligation of the United Nations to make efforts to develop international co-operation for the purpose of promoting respect for human rights implies that all Member States have an obligation to participate actively in these efforts.

Nothing more specific can be established from a study of Article 2 about the Member States’ human rights obligations, except a negative point contained in paragraph (7). According to this paragraph, the United Nations has no authority to undertake any action which constitutes an intervention in the domestic affairs of any state. In other words, the Organization is not permitted by its Charter – and therefore it is not obligated – to impose on any state, or compel it to accept, any arrangements in its internal administration or its relations to its own inhabitants, for whatever purpose. It was clearly understood by the authors of the Charter that whereas the United Nations and its Members should assume obligations for the promotion of respect for human rights, the actual observance of human rights was primarily the concern of each state.

In summary, the UN Charter imposes on the United Nations the obligation to initiate international co-operation, and on the Member States the obligation to participate actively and in good faith in such co-operation, for the purpose of promoting respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, by bringing about the adoption of suitable legislative and administrative measures in all independent states and dependent territories. Indeed, the whole United Nations system may be seen as a framework of organs, agencies and other formal institutions, operating under international law, for the achievement of international co- operation in pursuit of the various purposes of the Organization. Co-operation for the promotion of human rights, carried out through the appropriate organs – basically the General Assembly and ECOSOC together with the Human Rights Council – may take a variety of forms, which must always be consistent with the principle of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of any state. Among permissible forms of co-operation are:

(A)Conduct studies and investigations, writing reports, holding debates on human rights problems, and in due course preparing recommendations and draft conventions embodying measures for the protection of human rights.

Exercise as effectively as possible the moral authority of the Organization with a view to persuading or inducing all states to accept the recommendations and ratify the conventions.

- Waldheim, Kurt. 1985. In the Eye of the Storm , 134London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Kelsen, Hans. 1951. The Law of the United Nations , 29London: Stevens & Sons.

- Schwarzenberger, Georg. 1964. Power Politics, , 3rd ed., 462London: Stevens & Sons.

- Lauterpacht, Hersch. 1950. International Law and Human Rights , 147London: Stevens & Sons.

- Goodrich, L.M., Hambro, E. and Simons, A.P. 1969. Charter of the United Nations: Commentary and Documents, , 2nd ed., 25New York and London: Columbia University Press.

- Russell, Ruth B. 1958. A History of the United Nations Charter , 783Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- UN Human Rights Documentation

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- Research Guides

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- DHL Research Guides

UN Documentation Research Guides

- General Assembly Resolutions

- Security Council Meetings & Outcomes

- Security Council Vetoes

- About UN Documents

- How to Find UN Documents

- How to Use the UN Digital Library

- UN Document Symbols & Series Symbols

- UN Membership

- UN System Documentation

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- Economic and Social Council

- Trusteeship Council

- International Court of Justice

- Secretariat

- Charter of the UN

- Decolonization

- Development

- Disarmament

- Environment

- Human Rights

- International Law

- Peacekeeping

- Research UN Mandates

- UN Budget, 2020-

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Drafting History

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) 35th Anniversary

- Introduction

- Charter-based Bodies

- Treaty-based Bodies

- High Commissioner for Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is one of the first UN documents to elaborate the principles of human rights mentioned in the UN Charter. It was adopted by General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) on 10 December 1948 , by a vote of 48-0-8.

- Resolution symbol: A/RES/217 A (III)

- Meeting record: A/PV.183

- Voting summary: 48-0-8

Human Rights Day is celebrated on 10 December every year.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is one part of the resolution on the "International Bill of Human Rights" ( A/RES/217 (III) ). Following the adoption of this five-part resolution in 1948, two covenants were drafted that are also considered part of the International Bill of Human Rights, both were adopted in 1966:

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and its Optional Protocols

Unlike the covenants, the UDHR is not a treaty and has not been signed or ratified by states. See the UN Treaty Collection Glossary for more information on declarations.

The UN has adopted many more declarations and conventions on human rights topics since 1948. The lists on the UN Treaty Collection and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights websites are excellent starting points for research.

The drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights took place from 1946-1948 in several bodies including:

- Drafting Committee

- Commission on Human Rights

- General Assembly, including the Third Committee

Documents related to the drafting are available online through the ODS , UN Digital Library and the Drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights research guide. Links to additional archival materials are found in the UNOG research guide on the UDHR .

There are several ways to approach research on the drafting of the UDHR. Procedural histories or travaux préparatoires of the UDHR provide reference to the documents including drafts of the declaration, proposals by countries, meeting records, reports, and voting information.

- The UN Audiovisual Library of International Law has a brief scholarly procedural history of the UDHR, including an overview of the drafting process, links to selected UN documents, and related audio, video and photos.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: The Travaux Préparatoires . Edited by William A. Schabas. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). 3157 p. ( library holdings in WorldCat ) This reference book not only includes the relevant documents, but also indexes the documents by subject, article of the UDHR, personal name of participants, and country. This is an excellent starting point for research on country positions and the drafting of specific articles or paragraphs.

- Many additional websites, articles and books concern the UDHR, its drafting, its impact and/or various aspects of the declaration. Consult your librarian for help finding material available to you.

The drafters of the UDHR included many prominent people from around the world. The meeting records of the drafting bodies list the participants in the meetings; meeting records of the Economic and Social Council and the General Assembly generally name just the presiding officer and the speakers. Eleanor Roosevelt served as the Chair of the Commission on Human Rights during the drafting of the UDHR; she is sometimes referred to in meeting records as Chairman or Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Some sources for starting research on the drafters include:

- The research guide on drafting of the UDHR includes brief biographies of members of the Drafting Committee

- The Human Rights Day website highlights the contributions of several women

- The index to the Schabas Travaux Préparatoires lists contributions by personal name and by country

- Books and articles have been published about some of the UDHR drafters

The meetings of the various drafting bodies were held in different places. The meeting records or the reports of the bodies on their sessions indicate the date, time and location of the meetings. The declaration was adopted at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, where the third session of the General Assembly was held. The meeting at which the UDHR was adopted ( A/PV.183 ) was held in the "grande salle" of the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, France. The Palais is a theatre and the "grande salle" is its main room.

Translations

At the time of the adoption of the UDHR in 1948, resolutions of the General Assembly were published in Chinese, English, French, Russian, Spanish. Over 500 translations can be found on the UDHR website of the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights , including videos in several sign languages.

Links and Resources

- OHCHR website on UDHR

- Human Rights Day website

- UNOG Library research guide on UDHR

- OHCHR Library guide to UDHR resources

- Audiovisual Library of International Law - Historic Archives

- Ask DAG: What are travaux préparatoires and how can I find them?

- UN Human Rights Documentation by Dag Hammarskjöld Library Last Updated Feb 28, 2024 13599 views this year

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Drafting History by Dag Hammarskjöld Library Last Updated Dec 8, 2023 16015 views this year

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948): 30 Articles - 30 Documents: Exhibit for the 75th Anniversary by Dag Hammarskjöld Library Last Updated May 7, 2024 14151 views this year

- << Previous: High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Next: Resources >>

- Last Updated: May 24, 2024 4:31 PM

- URL: https://research.un.org/en/docs/humanrights

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Human Rights: Samples in 500 and 1500

- Updated on

- Dec 9, 2023

Essay writing is an integral part of the school curriculum and various academic and competitive exams like IELTS , TOEFL , SAT , UPSC , etc. It is designed to test your command of the English language and how well you can gather your thoughts and present them in a structure with a flow. To master your ability to write an essay, you must read as much as possible and practise on any given topic. This blog brings you a detailed guide on how to write an essay on Human Rights , with useful essay samples on Human rights.

This Blog Includes:

The basic human rights, 200 words essay on human rights, 500 words essay on human rights, 500+ words essay on human rights in india, 1500 words essay on human rights, importance of human rights, essay on human rights pdf.

Also Read: Essay on Labour Day

Also Read: 1-Minute Speech on Human Rights for Students

What are Human Rights

Human rights mark everyone as free and equal, irrespective of age, gender, caste, creed, religion and nationality. The United Nations adopted human rights in light of the atrocities people faced during the Second World War. On the 10th of December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Its adoption led to the recognition of human rights as the foundation for freedom, justice and peace for every individual. Although it’s not legally binding, most nations have incorporated these human rights into their constitutions and domestic legal frameworks. Human rights safeguard us from discrimination and guarantee that our most basic needs are protected.

Did you know that the 10th of December is celebrated as Human Rights Day ?

Before we move on to the essays on human rights, let’s check out the basics of what they are.

Also Read: What are Human Rights?

Also Read: 7 Impactful Human Rights Movies Everyone Must Watch!

Here is a 200-word short sample essay on basic Human Rights.

Human rights are a set of rights given to every human being regardless of their gender, caste, creed, religion, nation, location or economic status. These are said to be moral principles that illustrate certain standards of human behaviour. Protected by law , these rights are applicable everywhere and at any time. Basic human rights include the right to life, right to a fair trial, right to remedy by a competent tribunal, right to liberty and personal security, right to own property, right to education, right of peaceful assembly and association, right to marriage and family, right to nationality and freedom to change it, freedom of speech, freedom from discrimination, freedom from slavery, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of movement, right of opinion and information, right to adequate living standard and freedom from interference with privacy, family, home and correspondence.

Also Read: Law Courses

Check out this 500-word long essay on Human Rights.

Every person has dignity and value. One of the ways that we recognise the fundamental worth of every person is by acknowledging and respecting their human rights. Human rights are a set of principles concerned with equality and fairness. They recognise our freedom to make choices about our lives and develop our potential as human beings. They are about living a life free from fear, harassment or discrimination.

Human rights can broadly be defined as the basic rights that people worldwide have agreed are essential. These include the right to life, the right to a fair trial, freedom from torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the right to health, education and an adequate standard of living. These human rights are the same for all people everywhere – men and women, young and old, rich and poor, regardless of our background, where we live, what we think or believe. This basic property is what makes human rights’ universal’.

Human rights connect us all through a shared set of rights and responsibilities. People’s ability to enjoy their human rights depends on other people respecting those rights. This means that human rights involve responsibility and duties towards other people and the community. Individuals have a responsibility to ensure that they exercise their rights with consideration for the rights of others. For example, when someone uses their right to freedom of speech, they should do so without interfering with someone else’s right to privacy.

Governments have a particular responsibility to ensure that people can enjoy their rights. They must establish and maintain laws and services that enable people to enjoy a life in which their rights are respected and protected. For example, the right to education says that everyone is entitled to a good education. Therefore, governments must provide good quality education facilities and services to their people. If the government fails to respect or protect their basic human rights, people can take it into account.

Values of tolerance, equality and respect can help reduce friction within society. Putting human rights ideas into practice can help us create the kind of society we want to live in. There has been tremendous growth in how we think about and apply human rights ideas in recent decades. This growth has had many positive results – knowledge about human rights can empower individuals and offer solutions for specific problems.

Human rights are an important part of how people interact with others at all levels of society – in the family, the community, school, workplace, politics and international relations. Therefore, people everywhere must strive to understand what human rights are. When people better understand human rights, it is easier for them to promote justice and the well-being of society.

Also Read: Important Articles in Indian Constitution

Here is a human rights essay focused on India.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. It has been rightly proclaimed in the American Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Created with certain unalienable rights….” Similarly, the Indian Constitution has ensured and enshrined Fundamental rights for all citizens irrespective of caste, creed, religion, colour, sex or nationality. These basic rights, commonly known as human rights, are recognised the world over as basic rights with which every individual is born.

In recognition of human rights, “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was made on the 10th of December, 1948. This declaration is the basic instrument of human rights. Even though this declaration has no legal bindings and authority, it forms the basis of all laws on human rights. The necessity of formulating laws to protect human rights is now being felt all over the world. According to social thinkers, the issue of human rights became very important after World War II concluded. It is important for social stability both at the national and international levels. Wherever there is a breach of human rights, there is conflict at one level or the other.

Given the increasing importance of the subject, it becomes necessary that educational institutions recognise the subject of human rights as an independent discipline. The course contents and curriculum of the discipline of human rights may vary according to the nature and circumstances of a particular institution. Still, generally, it should include the rights of a child, rights of minorities, rights of the needy and the disabled, right to live, convention on women, trafficking of women and children for sexual exploitation etc.

Since the formation of the United Nations , the promotion and protection of human rights have been its main focus. The United Nations has created a wide range of mechanisms for monitoring human rights violations. The conventional mechanisms include treaties and organisations, U.N. special reporters, representatives and experts and working groups. Asian countries like China argue in favour of collective rights. According to Chinese thinkers, European countries lay stress upon individual rights and values while Asian countries esteem collective rights and obligations to the family and society as a whole.

With the freedom movement the world over after World War II, the end of colonisation also ended the policy of apartheid and thereby the most aggressive violation of human rights. With the spread of education, women are asserting their rights. Women’s movements play an important role in spreading the message of human rights. They are fighting for their rights and supporting the struggle for human rights of other weaker and deprived sections like bonded labour, child labour, landless labour, unemployed persons, Dalits and elderly people.

Unfortunately, violation of human rights continues in most parts of the world. Ethnic cleansing and genocide can still be seen in several parts of the world. Large sections of the world population are deprived of the necessities of life i.e. food, shelter and security of life. Right to minimum basic needs viz. Work, health care, education and shelter are denied to them. These deprivations amount to the negation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Also Read: Human Rights Courses

Check out this detailed 1500-word essay on human rights.

The human right to live and exist, the right to equality, including equality before the law, non-discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth, and equality of opportunity in matters of employment, the right to freedom of speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, the right to practice any profession or occupation, the right against exploitation, prohibiting all forms of forced labour, child labour and trafficking in human beings, the right to freedom of conscience, practice and propagation of religion and the right to legal remedies for enforcement of the above are basic human rights. These rights and freedoms are the very foundations of democracy.

Obviously, in a democracy, the people enjoy the maximum number of freedoms and rights. Besides these are political rights, which include the right to contest an election and vote freely for a candidate of one’s choice. Human rights are a benchmark of a developed and civilised society. But rights cannot exist in a vacuum. They have their corresponding duties. Rights and duties are the two aspects of the same coin.

Liberty never means license. Rights presuppose the rule of law, where everyone in the society follows a code of conduct and behaviour for the good of all. It is the sense of duty and tolerance that gives meaning to rights. Rights have their basis in the ‘live and let live’ principle. For example, my right to speech and expression involves my duty to allow others to enjoy the same freedom of speech and expression. Rights and duties are inextricably interlinked and interdependent. A perfect balance is to be maintained between the two. Whenever there is an imbalance, there is chaos.

A sense of tolerance, propriety and adjustment is a must to enjoy rights and freedom. Human life sans basic freedom and rights is meaningless. Freedom is the most precious possession without which life would become intolerable, a mere abject and slavish existence. In this context, Milton’s famous and oft-quoted lines from his Paradise Lost come to mind: “To reign is worth ambition though in hell/Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven.”

However, liberty cannot survive without its corresponding obligations and duties. An individual is a part of society in which he enjoys certain rights and freedom only because of the fulfilment of certain duties and obligations towards others. Thus, freedom is based on mutual respect’s rights. A fine balance must be maintained between the two, or there will be anarchy and bloodshed. Therefore, human rights can best be preserved and protected in a society steeped in morality, discipline and social order.

Violation of human rights is most common in totalitarian and despotic states. In the theocratic states, there is much persecution, and violation in the name of religion and the minorities suffer the most. Even in democracies, there is widespread violation and infringement of human rights and freedom. The women, children and the weaker sections of society are victims of these transgressions and violence.

The U.N. Commission on Human Rights’ main concern is to protect and promote human rights and freedom in the world’s nations. In its various sessions held from time to time in Geneva, it adopts various measures to encourage worldwide observations of these basic human rights and freedom. It calls on its member states to furnish information regarding measures that comply with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights whenever there is a complaint of a violation of these rights. In addition, it reviews human rights situations in various countries and initiates remedial measures when required.

The U.N. Commission was much concerned and dismayed at the apartheid being practised in South Africa till recently. The Secretary-General then declared, “The United Nations cannot tolerate apartheid. It is a legalised system of racial discrimination, violating the most basic human rights in South Africa. It contradicts the letter and spirit of the United Nations Charter. That is why over the last forty years, my predecessors and I have urged the Government of South Africa to dismantle it.”

Now, although apartheid is no longer practised in that country, other forms of apartheid are being blatantly practised worldwide. For example, sex apartheid is most rampant. Women are subject to abuse and exploitation. They are not treated equally and get less pay than their male counterparts for the same jobs. In employment, promotions, possession of property etc., they are most discriminated against. Similarly, the rights of children are not observed properly. They are forced to work hard in very dangerous situations, sexually assaulted and exploited, sold and bonded for labour.

The Commission found that religious persecution, torture, summary executions without judicial trials, intolerance, slavery-like practices, kidnapping, political disappearance, etc., are being practised even in the so-called advanced countries and societies. The continued acts of extreme violence, terrorism and extremism in various parts of the world like Pakistan, India, Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Somalia, Algeria, Lebanon, Chile, China, and Myanmar, etc., by the governments, terrorists, religious fundamentalists, and mafia outfits, etc., is a matter of grave concern for the entire human race.

Violation of freedom and rights by terrorist groups backed by states is one of the most difficult problems society faces. For example, Pakistan has been openly collaborating with various terrorist groups, indulging in extreme violence in India and other countries. In this regard the U.N. Human Rights Commission in Geneva adopted a significant resolution, which was co-sponsored by India, focusing on gross violation of human rights perpetrated by state-backed terrorist groups.

The resolution expressed its solidarity with the victims of terrorism and proposed that a U.N. Fund for victims of terrorism be established soon. The Indian delegation recalled that according to the Vienna Declaration, terrorism is nothing but the destruction of human rights. It shows total disregard for the lives of innocent men, women and children. The delegation further argued that terrorism cannot be treated as a mere crime because it is systematic and widespread in its killing of civilians.

Violation of human rights, whether by states, terrorists, separatist groups, armed fundamentalists or extremists, is condemnable. Regardless of the motivation, such acts should be condemned categorically in all forms and manifestations, wherever and by whomever they are committed, as acts of aggression aimed at destroying human rights, fundamental freedom and democracy. The Indian delegation also underlined concerns about the growing connection between terrorist groups and the consequent commission of serious crimes. These include rape, torture, arson, looting, murder, kidnappings, blasts, and extortion, etc.

Violation of human rights and freedom gives rise to alienation, dissatisfaction, frustration and acts of terrorism. Governments run by ambitious and self-seeking people often use repressive measures and find violence and terror an effective means of control. However, state terrorism, violence, and human freedom transgressions are very dangerous strategies. This has been the background of all revolutions in the world. Whenever there is systematic and widespread state persecution and violation of human rights, rebellion and revolution have taken place. The French, American, Russian and Chinese Revolutions are glowing examples of human history.

The first war of India’s Independence in 1857 resulted from long and systematic oppression of the Indian masses. The rapidly increasing discontent, frustration and alienation with British rule gave rise to strong national feelings and demand for political privileges and rights. Ultimately the Indian people, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, made the British leave India, setting the country free and independent.

Human rights and freedom ought to be preserved at all costs. Their curtailment degrades human life. The political needs of a country may reshape Human rights, but they should not be completely distorted. Tyranny, regimentation, etc., are inimical of humanity and should be resisted effectively and united. The sanctity of human values, freedom and rights must be preserved and protected. Human Rights Commissions should be established in all countries to take care of human freedom and rights. In cases of violation of human rights, affected individuals should be properly compensated, and it should be ensured that these do not take place in future.

These commissions can become effective instruments in percolating the sensitivity to human rights down to the lowest levels of governments and administrations. The formation of the National Human Rights Commission in October 1993 in India is commendable and should be followed by other countries.

Also Read: Law Courses in India

Human rights are of utmost importance to seek basic equality and human dignity. Human rights ensure that the basic needs of every human are met. They protect vulnerable groups from discrimination and abuse, allow people to stand up for themselves, and follow any religion without fear and give them the freedom to express their thoughts freely. In addition, they grant people access to basic education and equal work opportunities. Thus implementing these rights is crucial to ensure freedom, peace and safety.

Human Rights Day is annually celebrated on the 10th of December.

Human Rights Day is celebrated to commemorate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UNGA in 1948.

Some of the common Human Rights are the right to life and liberty, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom from slavery and torture and the right to work and education.

Popular Essay Topics

We hope our sample essays on Human Rights have given you some great ideas. For more information on such interesting blogs, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu .

Sonal is a creative, enthusiastic writer and editor who has worked extensively for the Study Abroad domain. She splits her time between shooting fun insta reels and learning new tools for content marketing. If she is missing from her desk, you can find her with a group of people cracking silly jokes or petting neighbourhood dogs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

1 The UN Charter and Its Evolution

Ian Johnstone is Dean ad interim and Professor of International Law at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University

- Published: 02 July 2019

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter conceives of the United Nations Charter as a “relational contract,” placing it somewhere between an ordinary treaty and global constitution. It is a legal instrument that structures a long-term relationship among UN member states and as such provides the normative and procedural foundation for much multilateral treaty-making. In other words, it is both a relational contract in itself and the embodiment of the relationship in which other multilateral treaties are negotiated, adopted, and implemented. While there are limits to the analogy, viewing the Charter in this way helps to explain how interpretation of the Charter has evolved. It also sheds light on the UN as a venue for and actor in treaty-making, and the implications of that for the development of treaty law. The chapter concludes that insights from relational contract theory show why the UN Charter has survived as the foundation for the international order, and why it is resilient enough to continue to do so despite the fundamental challenges to that order that are currently being witnessed.

This chapter seeks to answer two questions: What type of legal instrument is the United Nations Charter, and why has the UN come to play such a central role in treaty-making? I draw on relational contract theory to answer both. My central claim is that the Charter is neither an ordinary treaty nor a global constitution, but something in-between. It is a legal instrument that structures a long-term relationship among UN member states and as such provides the normative and procedural context within which many multilateral treaties are made.

The chapter begins with an explanation of relational contract theory and how it illuminates the nature of the UN Charter. A section on interpretation of the Charter as a “living tree” follows. The third section looks at the UN as both a venue for and actor in treaty-making. The chapter concludes with reflections on where this is heading. If the strength of a “relational” treaty depends in part on the desire of the parties to preserve the relationship it embodies, do the current challenges to the UN and multilateralism generally put the viability of the Charter in jeopardy?

1 The Charter as a Relational Contract

The UN Charter is not an ordinary treaty. It has certain constitution-like features that distinguish it from most other treaties. 1 Foremost among them is the primacy principle embodied in Article 103, which holds that in the event of a conflict between obligations under the UN Charter and those under any other agreement, the Charter trumps. Second, like most national constitutions, amending the Charter is difficult—requiring the approval of a supermajority in the General Assembly, including all five permanent members of the Security Council. A third feature is that the Charter spells out the division of competencies among the constituent parts of the organization. Moreover, some of its core articles are “constitutive rules” of the international system—rules that do not simply regulate the conduct of states, but give structure to the international system. 2 The principle of sovereign equality, the prohibition against the use of force, and respect for the obligations that arise from treaties (pacta sunt servanda ) are amongst these rules.