- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Most Scathing Book Reviews of 2022

“reading this book reminded me of watching a cat lick a dog’s eye goo.”.

‘Tis the season for schadenfreude. Yes, for the sixth year running, we’ve emerged from the bowels of the book review mines trailing behind us an oozing sack of pans—each one riper and more wince-inducing that the last.

Among the books being gored and devoured by feral hogs this year: Jared Kushner’s soulless work of sycophancy, John Boyne’s shameless sequel to The Boy in the Striped Pajamas , and Hanya Yanagihara’s “anti-accomplishment” doorstopper.

So here they are, in their fabulously festering fulsomeness: the most scathing book reviews of 2022.

“It’s a title that, in its thoroughgoing lack of self-awareness, matches this book’s contents … He betrays little cognizance that he was in demand because, as a landslide of other reporting has demonstrated, he was in over his head, unable to curb his avarice, a cocky young real estate heir who happened to unwrap a lot of Big Macs beside his father-in-law … Breaking History is an earnest and soulless—Kushner looks like a mannequin, and he writes like one—and peculiarly selective appraisal of Donald J. Trump’s term in office. Kushner almost entirely ignores the chaos, the alienation of allies, the breaking of laws and norms, the flirtations with dictators, the comprehensive loss of America’s moral leadership …

This book is like a tour of a once majestic 18th-century wooden house, now burned to its foundations, that focuses solely on, and rejoices in, what’s left amid the ashes … Reading this book reminded me of watching a cat lick a dog’s eye goo … The tone is college admissions essay … Kushner, poignantly, repeatedly beats his own drum … A therapist might call these cries for help … The bulk of Breaking History —at nearly 500 pages, it’s a slog—goes deeply into the weeds … What a queasy-making book to have in your hands.”

–Dwight Garner on Jared Kushner’s Breaking History: A White House Memoir ( The New York Times )

“ The Philosophy of Modern Song is a mouthful, a phrase that puts on airs. It asserts that the book is an important work, a tome that merits a place on your loftiest library shelf, up in the thin air where you keep the leather-bound, gilt-edged stuff … But the title is also a wisecrack, too puffed up and self-important to be taken at face value … As a work of prose, The Philosophy of Modern Song is relentless. It rip-snorts along, charging from song to song, idea to idea. Dylan can write what journalists call a great lede: a first sentence that detonates like a hand grenade … What does all this add up to? Not quite a philosophy of modern song, or at least not a coherent one. But coherence isn’t what you want from Bob Dylan …

You have to plow through 46 chapters before encountering a song by a female artist … Yet women loom large in his consciousness and are omnipresent in his pages—appearing in such monstrous form, evoked in language so marinated in misogyny, that, reading The Philosophy of Modern Song, I began to feel like a therapist, sneaking glances at my watch while the crackpot on the couch blurts one creepy fantasy after another … It’s a bummer, to put it mildly, to find a Nobel laureate…mixing metaphors and spouting nonsense like an elderly uncle who bulk-emails links to Fox News segments.”

–Jody Rosen on Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song ( The Los Angeles Times )

“ Moshfegh’s own sacraments involve a different orifice, so you will forgive her if her search has led her up her own ass … At first glance, Lapvona is the most disgusting thing Moshfegh has ever written…Yet Moshfegh’s trusty razor can feel oddly blunted in Lapvona . In part, her characteristic incisiveness is dulled by her decision to forgo the first person, in favor of more than a dozen centers of consciousness. This diminishment is also a curious effect of Lapvona itself … Lapvona is the clearest indication yet that the desired effect of Moshfegh’s fiction is not shock but sympathy. Like Hamlet, she must be cruel in order to be kind. Her protagonists are gross and abrasive because they have already begun to molt; peel back their blistering misanthropy and you will find lonely, sensitive people who are in this world but not of it, desperate to transform, ascend, escape …

This is the problem with writing to wake people up: Your ideal reader is inevitably asleep. Even if such readers exist, there is no reason to write books for them—not because novels are for the elite but because the first assumption of every novel must be that the reader will infinitely exceed it. Fear of the reader, not of God, is the beginning of literature. Deep down, Moshfegh knows this….Yet the novelist continues to write as if her readers are fundamentally beneath her; as if they, unlike her, have never stopped to consider that the world may be bullshit; as if they must be steered, tricked, or cajoled into knowledge by those whom the universe has seen fit to appoint as their shepherds …

It’s a shame. Moshfegh dirt is good dirt. But the author of Lapvona is not an iconoclast; she is a nun. Behind the carefully cultivated persona of arrogant genius, past the disgusting pleasures of her fiction and bland heresies of her politics, wedged just above her not inconsiderable talent, there sits a small, hardened lump of piety. She may truly be a great American novelist one day, if only she learns to be less important. Until then, Moshfegh remains a servant of the highest god there is: herself.”

–Andrea Long Chu on Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona ( Vulture )

“Reading it is like immersive theatre: one of those elaborate warehouse productions where you stumble about from tableau to tableau, trying to piece the story together … The novel is long on atmosphere and short on sense. There are slick, movie-style conversations with a private investigator, a Vietnam vet, and a trans woman; long lunches with a garrulous criminal friend; flashbacks to Alicia’s hallucinations; the obligatory bit of survivalism (would it even be a McCarthy novel without an episode involving tinned foods and roadkill?) …

James Joyce is invoked. An oblique reminder that great literature requires hard work? But McCarthy’s difficulty is perverse. The decision to open The Passenger with an impenetrable conversation between Alicia and her hallucinations; the quantum mechanics; the pinball structure; the confusing dialogue—all this just makes the novel hard to read. Nothing meaningful is gained. It’s a shame because at times these books are more interesting than McCarthy’s key works … We think these books are unflinching. Really, they are kitsch: McCarthy’s is an art of exaggeration. A con trick is being practised … That’s how you garner comparisons to Hemingway and Faulkner—when, in fact, you’re a mediocre hybrid of both .”

–Claire Lowdon on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger ( The Sunday Times )

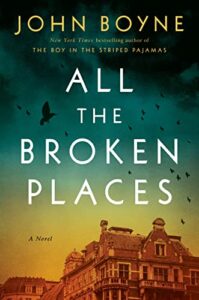

“With his latest treacly tome All the Broken Places— complete with title so maudlin it preempts all mockery—Boyne has gifted us with a Holocaust novel so self-indulgent, so grossly stereotyped, so shameless and insipid that one is almost astonished that he has dared … This is not literature. As a grown-up sequel to children’s trash, All the Broken Places serves two roles. First, to demonstrate that Boyne definitely did not think that the Germans were innocent, definitely knew they were ‘complicit’ and ‘guilty’ and that history is ‘complicated,’ etc, thanks very much. Second, to serve as a sort of fan fiction for those peculiar adults who long for the comfort of a childhood favorite. As to this first goal, at least, it is a consummate failure, a wildly simplified narrative that misrepresents the extent of Nazi ideology. As in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas , Boyne underestimates the family’s awareness of the Holocaust, lending his German characters an exaggerated naivety, or implausible deniability …

Boyne flaunts a teenager’s understanding of the causes and consequences of the Second World War … As with so much Holocaust fiction All the Broken Places utterly fails in its stated purpose: making the next generation slightly less likely to participate in the next genocide… Boyne’s reduction of Nazi ideology to a fringe belief, expressed in infrequent outbursts—’those filthy Jews’—is all the more absurd now that he’s writing for grown-ups …

We don’t need anyone to teach us how to recognize the barefaced devil; the danger is the insidious and gradual creep of violence into the civilised and everyday. This is what the philosopher Theodor Adorno’s dictum—’To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’—warned of: art unable to recognise the break the Holocaust represented with the past, afraid to apprehend the failure of the civilising project. With this childish drivel in which the villains and victims come labelled and sorted, Boyne yet again seems immune to its lessons.”

–Ann Manov on John Boyne’s All the Broken Places ( The New Statesman )

“99 years old, but still, still pushing out the kind of platitudes that not only can be used to excuse the most evil people in the history of the species but that are designed to do exactly that… This rhetoric-as-strategy is obvious right from this book’s cast of characters…A reader might first wonder what Konrad Adenauer is doing drawn among these heartless hinds, but eyebrows might raise at de Gaulle and even Sadat as well… A moment’s thought reveals the beady-eyed rationale behind this grouping; it’s not to pull down good men, it’s to raise up genuine fire-eyed black-pelted yellow-fanged monsters… Henry Kissinger might not be able to climb a flight of stairs anymore, but he’s still capable of telling a lie before he’s even finished his Table of Contents… As he’s winding up this ghastly, conscienceless book, Kissinger contentedly admits that his subjects weren’t always popular… Not everyone admired them or ‘subscribed to their policies’… Sometimes, in fact, they faced resistance, and their separate memories still sometimes face such resistance… Almost like there might be debate about their legacies, or something… Leadership might very well be Kissinger’s most mandarin-hateful book, even surpassing 2014’s truly odious World Power … It’s his 19th book… Here’s hoping it’s his last. ”

–Steve Donoghue on Henry Kissinger’s Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy ( Open Letters Review )

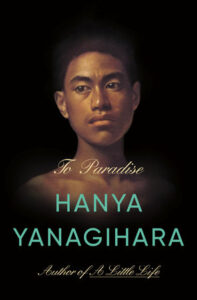

“ To Paradise is so unusually terrible that it is a sort of anti-accomplishment, the rare book that manages to combine the fey simplicity of a children’s tale with near unreadable feats of convolution . It is too juvenile to attract serious adult readers and too obtuse to aspire to popular appeal. If A Little Life dragged and self-dramatized, at least it did so via a welter of readily legible, melodramatic thrills. But soap opera fanatics will fare no better with To Paradise ’s contortions than will seasoned belletrists. There is nothing to recommend it to anyone. As I trudged through the novel’s 700 pages, I found myself nostalgic for books plagued only by quaint defects, such as confusing descriptions and characters who behave inconsistently—not that Yanagihara, who has a special gift for garbled metaphors and bizarrely specific yet impenetrable imagery, spares us such infelicities …

It is hard to summon the will to enumerate To Paradise ’s thematic or even stylistic shortcomings, for its basic construction is so irretrievably botched as to eclipse the rest of its defects. The fundamental problem is simple and devastating: the book does not make any sense … Aside from its sheer incoherence, its most notable feature is only its punishing length. On and on it goes, sprouting new subplots, amassing new contrivances. Anyone must have a brain of stone to finish it without shedding tears of relief.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Hanya Yanagihara’s To Paradise ( Times Literary Supplement )

“Viral success has emboldened [Taddeo] to abandon everything patient and methodical in her investigation of women’s darker appetites in favour of the literary equivalent of chasing clicks … Ghost Lover is a nine-course tasting menu that is all spice and no flavour … The main dish is always the same facile serving of female jealousy. In every effortfully flippant tale, self-conscious women compete to be the most desirable female in the room … At least the proper nouns denote actual things. When Taddeo attempts metaphor, we run into more serious trouble … Throughout, Taddeo rams words together in unexpected ways. ‘His voice turned throaty, filled with wetness and trees.’ Trees? …

Perhaps Taddeo has read Lolita and feels excited about experimenting with the English language. Only it feels more as if she has done the experimenting in another tongue, Finnish or Swahili, perhaps, then run a series of untranslatable local sayings through Google Translate … In the course of producing this Goop noir, Taddeo has abandoned any interest in women as complex, conflicted humans. Her characters are myopically focused on blow-dries, blow jobs and brow tints … Inspires depression.”

–Johanna Thomas-Corr on Lisa Taddeo’s Ghost Lover ( The Sunday Times )

“ Everything in Lessons , whose story concludes within a year and a half of its publication date, gives the impression of having been written in extreme haste . Its prose, for example, is pocked with first-order clichés, second-order clichés, dull metaphors, mixed metaphors, limp similes, oxymorons, pleonasms, catachresis, jejune diction, trivializing double entendres, pomposities, flagrant abuse of self-reflexive questions, and barely-concealed cribbings from more talented stylists like Nabokov … Within the first fifty or so pages, Roland experiences no fewer than three portentous epiphanies, none of which turn out to have any bearing on the subsequent four hundred, as though they were narrative coupons McEwan cut out but forgot to cash in …

McEwan’s novel is not so much an epic as it is three novellas in a trench coat … If this all sounds pat, it has less to do with the necessary evil that is plot summary in book reviewing, than to the didacticism with which McEwan imparts these and other praecepta in the novel itself. Yet perhaps worse than the way the book comes pre-interpreted for the reader is the way it comes pre-criticized … The trench coat is History. Draped loosely from the backs of these three narratives are hundreds of named political and cultural events, persons, and phenomena, starting with Dunkirk and ending with the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, which range from the genuinely consequential to the merely newsworthy to the unmentionably trivial.”

–Ryan Ruby on Ian McEwan’s Lessons ( The New Left Review )

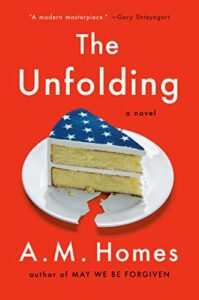

“There is a good, though not excellent, short story hidden somewhere in the four hundred pages of A. M. Homes’s The Unfolding … But on balance, The Unfolding is depressingly shallow, arriving too late and with too little intelligence, humor, wit, or insight to be useful or entertaining … The plot is simple … The structure—dilating and contracting across a narrow band of time—works best in subtly paralleling personal and familial breakdowns with national upheaval, but at its worst, the form makes this novel feel interminable … Homes is dedicated to the idea of these men as so pickled by their own vice and privilege that there’s not an intelligent thought to be found among them. They remain static in their grumbling and their vague schemes, which prevents the irony from deepening or sharpening its critique. What ought to be a central driver of the plot or the evolution of the novel’s themes becomes an inert gimmick …

Homes trades away her characters’ convictions and depth for attempted comedic effect. No contrast. No pathos. These men are hollow, which makes the story itself hollow … Homes for some reason describes any surface or object that comes into contact with her characters as though she were writing about the contours of the human soul. Do we need to know what the taxi seats feel like? … I was bored by this book. By its lazy stances, its lax politics, and its rote writing.”

–Brandon Taylor on A.M. Holmes’ The Unfolding ( 4Columns )

“The institutional tone in 21st-century humor is unequipped to deal with anything that matters. In Happy-Go-Lucky , his new collection of essays about the pandemic, aging, and the slow but inevitable death of his father, David Sedaris simultaneously asserts himself as the undisputed past master of this tone and captures its fundamental weakness, applying the style he has developed for the last 30 years to a subject matter for which it is almost eerily unsuited … It is ironic, then, that relatability also turns out to be the absolute bête fucking noire of this collection, cropping up again and again to recast Sedaris not as the antsy everyman we grew up with but rather as some kind of moneyed Aspergers case …

For a different author, that would be comedy gold—or at least a bracing opportunity to try something new, to go somewhere more vulnerable and potentially less funny, but also maybe incisive and bittersweet in a way that made the late-life output of funny writers like Twain and Joan Didion so paradoxically invigorating. But Sedaris can’t seem to do it. Either he doesn’t have enough tools in the box or he just refuses to look too closely at any of these understandably difficult subjects, so instead he writes about them in the same tone he used to write about department-store Santas and being bad at French, with disastrously jarring results …

Sedaris is like the social director running around the deck of a listing cruise ship, frantically playing for laughs and doing jazz hands while the reader wonders whether he doesn’t know the ship is sinking or just refuses to acknowledge what’s going on … A man with a dozen houses confronts death, the coronavirus pandemic, Black Lives Matter, and broad cultural changes that he cannot fully understand. ‘Ha ha!’ he says. It sounds just like a laugh, just like it always has, except it does not sound true.”

–Dan Brooks on David Sedaris’ Happy-Go-Lucky ( Gawker )

“Even if you’re unfamiliar with this tradition of stories about race transformation, you’ll suspect what’s coming … Tone above all distinguishes Hamid from these precursors. Whereas most of these writers bend race transformation toward satire, offering us topsy-turvy and hysterical tales, Hamid is deeply earnest about his conceit. The novel is that wan 21st-century banality, a ‘meditation,’ and it meditates on how losing whiteness is going to make white people feel. Mostly sad, as it turns out … The sex improves; the prose does not … The novel evinces the worst of Hamid’s style …

As in his earlier novels about social mobility and immigration, romance supplies the plot and casts an aura of ‘love’ over the politico-speculative gimmick … This is the novel’s cure for white despair over the loss of whiteness: Keep calm and carry on … What exactly is being born—or rather, borne? Darkness in The Last White Man is an ordeal. Those who were already dark have little presence and no internal life in the novel … If Hamid’s novel were a self-aware satire of this ideology of whiteness and its violent effects, it would be pitch-perfect. But The Last White Man ’s structure affords us no way to know if this is what Hamid intends: It includes no higher judgment, no specific history, no novelistic frame against which to measure the reliability of the narration, no backdrop across which irony can dance …

The Last White Man feels like a primer for mourning whiteness, not a critique of it … It’s one thing for a character to be afflicted with blurred vision or the race ‘blindness’ that grants Oona a ‘new kind of sight’; it’s another for the novel to suffer the same confusion of perspective.”

–Namwali Serpell on Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man ( The Atlantic )

“… surely the nastiest Trump administration memoir yet, and possibly, given Conway’s track record, the most flagrantly dishonest … in 500 pages packed with more score-settling than a Quentin Tarantino movie, Conway gives free rein to her contempt for Jared Kushner, Steve Bannon, Mark Meadows, Brad Parscale, Reince Priebus, Sean Spicer, and countless other unnamed male Trump staffers … let no one call this book meticulously edited … When she can’t confuse a discussion with arguments as tangled as a pailful of eels, Conway simply avoids it … feels most alive when she’s seething at the ‘overrated, underachieving men who had ridiculed and dismissed me for years’ …

Can be read as the delusional account of a woman blind to the shortcomings of the powerful man who gave her a shot. But it can also be read—will be read, by those who matter—as an advertisement for her own consultancy business. She’s such a skilled prevaricator that I found myself wondering if she really hates all those male GOP consultants so virulently—or is she just taking out the competition? Furthermore, the ease with which she burns her bridges with Kushner while buttering up her one-time client Mike Pence make clear who she thinks her party’s next candidate will be. Only a fool would trust her, but only a bigger fool would write her off.”

–Laura Miller on Kellyanne Conway’s Here’s the Deal: A Memoir ( Slate )

“ John Irving’s 15th novel is 11 shy of 900 pages long. And boy, did I feel every one of those pages … a baffling amount of weak literary explication and juvenile political opining … The most notably shoehorned element (and there are many, including the ghosts that irritatingly scamper throughout) is the inclusion of excerpts of Adam’s film script—so unnecessary and ill-advised in this already flabby book, it’s difficult not to wonder if this might have been a rejected love-project of Irving’s …

The truly discomfiting aspect of this book, though, has to be the hyper-sexualisation of the female characters therein. Early on, a young woman’s loud orgasm is described or referenced, by my count, 16 times. Yes, Irving could argue that this is told from a teenage boy’s perspective, and thus that focusing on all things arousing is only natural. But these leering and, again, endlessly repeated descriptions, read more like the errant mental wanderings of a horny older man than the thoughts of a pubescent boy … There is so much more I could’ve written, but thankfully, unlike Irving, I have a word count to consider.”

–Sweeney Byrne on John Irving’s The Last Chairlift ( The Irish Times )

“As an avant-garde firebrand in the 1960s, Handke wrote an ‘anti-play’ titled Offending the Audience, but now his strategy has shifted perilously close to Boring the Audience to Tears . Much like the narrator imagining the character of the fruit thief, I kept trying to envision a subset of readers who genuinely find this stuff delightful. Lacking most of the elements that draw people to fiction—insight, suspense and so on—it falls to either the language or the narrative material itself to make the novel worth the reader’s while. Although both have their moments—a mad speech in the final pages, an interlude at an inn that takes on the lighting and atmosphere of old European folk tales—the meal served up by this deeply eccentric novelist is spare and saltless, with no wine and no dessert. I suspect it’s the destiny of such an uncompromising writer as Peter Handke to end up writing basically for an audience of one. His most loyal readers, perhaps, adopt an attitude of veneration, hushed and solemn and more or less bored, the way many people attend Mass.”

–Rob Doyle on Peter Handke’s The Fruit Thief ( The New York Times Book Review )

Hungry for more harsh critiques? Reacquaint yourself with The Most Scathing Book Reviews of 2017 , 2018 , 2019 , 2020 , and 2021 .

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Dan Sheehan

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Literary Fanmail: The Letters of Harold Bloom and James Merrill

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Worst of 2022: The Books

Posted January 18, 2023 by Casee in Features | 2 Comments

It’s that time of year again. The time where we come together and look over the books that we’ve read over the course of 2022 and list our favorites. Today’s list will include our least favorite books of 2022. Thanks for joining us on our 2022 reading journey these past few weeks!

The Viper ( Black Dagger Brotherhood: Prison Camp #3 ) by J.R. Ward : This book was not for me. I generally like or feel ambivalent when it comes to JRW. Still–I read every book that she releases. I really regretted reading this one. It was a waste of time.

Free ( Chaos #6 ) by Kristen Ashley : The whole ending to the Benito Valenzuela was just lame. It was just too much.

Shadow Music ( Highlands’ Lairds #3 ) by Julie Garwood : I decided to try to reread this book (on audio). Unfortunately I couldn’t finish it. The heroine was just about unbearable.

Dream Chaser ( Dream Team #2 ) by Kristen Ashley : I DNFed this at 55%. Both Ryn & Boone were awful. I don’t know what they saw in each other because I saw nothing.

Annihilation Road ( Torpedo Ink #6 ) by Christine Feehan : This book was just okay. It was part of a duo within the series & after reading this one, I didn’t read the next.

A Farewell to Charms ( Mystic Bayou, #6 ) by Molly Harper : I usually love Molly Harper’s books and this series in particular, but A Farewell to Charms was painful to read. Alex crossed a serious line in the beginning and I was never able to move past what he did.

All Is Faerie in Love and War ( Fangs and Feathers, #2 ) by Isla Frost : The terrible things the MC did and the way they were addressed in this book ruined my reading experience. I’m sad about it since I enjoyed the first book.

Heart of Hope by Lucy Score : I really enjoyed a lot of books by Score this year, but while the premise of this one was interesting, the execution left a lot to be desired. The secret he kept and her reaction to it kind of killed the story for me. Plus, the whole organ donor thing was a little cheesy.

The Purveli ( Aldebarian Alliance, #3 ) by Dianne Duvall : This is the third book in the Aldebarian Alliance series. If it had been book 2 I think I would have enjoyed it more. As it is, literally every single aspect of it, save one, was spoiled in book 2. There were no surprises or intrigues because we learned everything there was to know about this book in the previous one. It was a total disappointment to read.

Black Moon ( Alpha Pack, #3 ) by J.D. Tyler : I ended up DNF’ing this book. I just couldn’t connect with Kalen or Mac. They both acted immature and weak. I thought about powering through, but honestly nothing worked for me and I didn’t see a point in continuing.

Who were your worst reads of 2022?

Share this:.

- Related Posts

2 Comments Tagged: Casee's Worst of Lists , Holly's Worst of Lists , Worst of 2022

2 responses to “ Worst of 2022: The Books ”

The book that disappointed me the most was Eve Dangerfield’s VELVET CRUELTY. I think in part because I was expecting an “Eve Dangerfield” book full of her trademark heat, heart, and humor, not yo mention self-aware heroines who function with autonomy. Instead, I got a very dark reverse harem romance with an innocent 18-year-old heroine and four heroes (all awful in different ways). So disappointing. I’m not even interested in reading the next book in the series. I wish Dangerfield would have spent her time finishing her Silver Daughters series rather than jumping on the dark romance bandwagon—which is a sub-genre obviously not for her.

I did not finish many books that I started last year, but I’ve put all the details out of my mind! Here’s hoping for some wonderful books in 2023 for us all.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

Thornfield Hall

A Book Blog

The Best and Worst Books of 2022

Readers love the “Best and Worst Books of the Year” lists. I enjoy waking up on a winter morning and (virtually) rustling the newspaper pages for “Best of” lists. I prefer the lists, meant for Christmas shopping, to the actual holidays.

The lists are published earlier every year, however. A few newspapers and magazines published their “Best of’s” before Thanksgiving, which is much too early. The amateurs – Goodreads reviewers, bloggers, and vloggers – are usually more traditional and wait till December. For the first time, I saw a few bloggers and vloggers posting their lists before Halloween!

And that is a huge turn-off.

That said, I have posted my “Best and Worst Books of 2022” list appropriately- in December. I posted links to my reviews at Thornfield Hall and Thornfield Hall Redux , and, in a few cases, Goodreads.

THE BEST AND WORST BOOKS OF 2022!

BEST NEW NOVELS

1. Elizabeth Finch , by Julian Barnes.

2. French Braid , by Anne Tyler

3. The Exhibitionist , by Charlotte Mendelson

4. The Book of Mother , by Violaine Huisman

5. Free Love , by Tessa Hadley

BEST NEW “GENRE” BOOKS

1. Termination Shock , by Neal Stephenson

2. Agatha Christie: An Elusive Woman , by Lucy Worsley (A biography of a genre writer!)

3. A Restless Truth , by Freya Marske

BEST OLDIES

1. The Matchmaker , by Stella Gibbons

2. Rule Britannia , by Daphne du Maurier

3. The Malayan Trilogy , by Anthony Burgess

4. How Green Was My Valley , by Richard Llewellyn

5. The Revolt of the Angels , by Anatole France

BEST CLASSICS

1. Bleak House , by Charles Dickens

2. Life and Fate , by Vasily Grossman

3. The Captain’s Doll , by D. H. Lawrence

4. Lady Susan , by Jane Austen

5. Katherine Mansfield: Letters and Journals

THE WORST OF THE YEAR

1. The Bloater , by Janet Tonk

2. The Half Sisters , by Geraldine Jewsbury

Happy Holidays! You can go to the LargeHearted Boy blog for links to more Best of the Year lists.

Share this:

4 thoughts on “the best and worst books of 2022”.

It’s a bit surprising that ‘The Exhibitionist’ by Charlotte Mendelson made your list since it is not due to be released in the United States until 7/4/2023 according to Amazon. 🙂

I got a British copy. I wonder why it takes so long to publish it here. It’s a mystery!

Good list! I would add Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout to the best new books, and Little Dorrit to the best classics.

I would love to read Lucy by the Sea. (I was disappointed Strout didn’t win the Booker this year.) Am in agreement too about Dickens!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from Thornfield Hall

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Romantic Parvenu

Book Reviews

Ranking All the Books I’ve Read in 2022 (so far)

July 4, 2022

We’re halfway through 2022! We did it.

Today I’m breaking down almost all of the books I’ve read in the past six months and ranking them from best to worst via a highly scientific methodology, the results of which have been peer reviewed by both of my dogs. Be amazed.

Although I am a reader who uses numeric ratings, this Highly Official Ranking System is different. So here’s your nifty guide:

- God Tier : new favorite, bookish perfection, something to screech about, etc.

- Really Good : enjoyable, memorable, would read again without hesitation, “not your average book” kind of book

- Good : a solid read, would recommend, probably wouldn’t read again for whatever reason

- Fine : is it awful? no. is it something I want to have living on my shelf for the next decade? also no.

- Bad : it’s not a good book, Susan, it’s just not

- Horrible : jail for book! jail for One Thousand Years!!!

- It’s Complicated : books I maybe enjoyed but have difficulty categorizing due to problematic stuff

AKA: new favorite, bookish perfection, something to screech about, etc.

SISTERSONG by Lucy Holland — magical alt history folktale retelling featuring a trans prince (!!!)

THE QUEER PRINCIPLES OF KIT WEBB by Cat Sebastian — the ultimate “be gay, do crime” romance novel

ONCE UPON A QUINCEÑERA by Monica Gomez-Hira — everything that is wonderful and messy about being 18

HUNT THE STARS by Jessie Mihalik — A perfect meld of romance and sci-fi.

Really Good

AKA: enjoyable, memorable, would read again without hesitation, “not your average book” kind of book

WE WERE RESTLESS THINGS by Cole Nagamatsu — literary magical realism for the youths

OLGA DIES DREAMING by Xochitl Gonzalez — colonialism, family dysfunction, political thriller *chef’s kiss*

WEATHER GIRL by Rachel Lynn Solomon — an excellent workplace romance

THE FIFTH SEASON by N.K. Jemisin — is there anything to say? we all know this is good.

WINTER’S ORBIT by Everina Maxwell — political thriller sci-fi with strooooong romantic elements

THE WOLF DEN by Elodie Harper — Roman Empire, but about the lower classes outside of Rome itself

GIRL GONE VIRAL by Alisha Rai — the Platonic ideal of a bodyguard romance

SOMETHING FABULOUS by Alexis Hal l — utterly absurd and utterly gay

GET A LIFE, CHLOE BROWN by Talia Hibbert — unique and wholesome contemporary romance

DELILAH GREEN DOESN’T CARE by Ashley Herring Blake — excellent romance with a lot of realistic family complications

WHEN BLOOD LIES by C.S. Harris — this is my favorite series, my favorite couple, etc.

ALL MY RAGE by Sabaa Tahir — a very uncomfortable book to read but also very very good

NIGHTCRAWLING by Leila Mottley — a nonsensationalized glimpse into police corruption, poverty, racism, etc. (and Mottley is nineteen! )

THE DEGENERATES by J. Albert Mann — highly informative story about girls who were institutionalized as part of eugenics policies

THE WAGES OF SIN by Kaite Welsh — Victorian England was about more than pretty dresses and dukes; here’s a book to make you hopping mad @ the patriarchy

AKA: a solid read, would recommend, probably wouldn’t read again for whatever reason

THE HALF-DROWNED KING by Linnea Hartsuyker — exciting plot + excellent research into Viking society

BEASTS OF A LITTLE LAND by Juhea Kim — beautifully written, bittersweet intergenerational saga set in 20th century Korea

A LADY’S GUIDE TO MISCHIEF AND MAYHEM by Manda Collins — more of a mystery than a romance, but enjoyable

THE RIGHT SWIPE by Alisha Rai — good, but development of hero’s character was lacking

HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK by Sequoia Nagamatsu — innovative hybrid between a novel and a short story collection

RENEGADE LOVE by Ann Aquirre — solid “morality chain” alien romance

THE DEATH OF VIVEK OJI by Akwaeke Emezi — very pretty and bittersweet

PACHINKO by Min Jin Lee — well-written, but becomes too episodic by the end

NO BEAUTIES OR MONSTERS by Tara Goedjen — if Stranger Things was a book, basically

THE FALLING GIRLS by Hayley Krischer — toxic murdering co-dependent cheerleaders (!)

NEVER LOOK BACK by Lilliam Rivera —interesting Greek myth retelling set in the Bronx

THE SCHOOL OF MIRRORS by Eva Stachniak — slowish story about women during the final days of the French monarchy

SO THIS IS EVER AFTER by F.T. Lukens — what happens after you save the world?; AKA “two idiots in love”

WHEN WE LOST OUR HEADS by Heather O’Neill — rich girls in Montreal as a metaphor for the French Revolution (I guess???)

FIREBREAK by Nicole Kornher-Stace — post-climate crisis dystopia in which megacorporations rule the world

BOOK OF NIGHT by Holly Black — solid urban fantasy featuring a heist and interesting magic

THE DRAGON’S BRIDE by Katee Robert — not as sexy as I wanted, but a good “captive” romance that heavily emphasizes mutual consent

AKA: is it awful? no. is it something I want to have living on my shelf for the next decade? also no.

ARSENIC AND ADOBO by Mia P. Manansala — mediocre mystery with a decent “hook”

THE RAVEN TOWER by Ann Leckie — queer fantasy Hamlet with second-person narrator and sentient rocks

DAUGHTER OF THE MOON GODDESS by Sue Lynn Tan — too long, plot is disorganized

THE SIREN OF SUSSEX by Mimi Matthews — working class Victorian romance but author doesn’t follow-through on attempts to explore oppression

MASTER OF POISONS by Andrea Hairston — climate disaster fantasy where author’s vision lacked clarity

SERPENT & DOVE by Shelby Mahurin — decent fantasy romance, but read like the stuff that was coming out 10 years ago

THE BEHOLDEN by Cassandra Rose Clarke — fun quest/adventure fantasy with a simple storyline more suited to middle grade than adult

THE VERIFIERS by Jane Pek — predictable and tropey mystery novel

THE IVORY KEY by Akshaya Raman — just okay; too many narrators, too much going on

FOLLOW ME TO GROUND by Sue Rainsford — lots of vibes, no real substance

THE ONES WE’RE MEANT TO FIND by Joan He — overly concerned with complex plot structure

MY SISTER, THE SERIAL KILLER by Oyinkan Braithwaite — the title says it all

A FAR WILDER MAGIC by Allison Saft — solidly readable, but I have Thoughts about the world-building

YELLOW WIFE by Sadeqa Johnson — would have been great if the narrative climax didn’t occur off-page (wtf?)

THE PERFECT CRIMES OF MARIAN HAYES by Cat Sebastian — understanding the plot is wholly reliant on the companion novel, which is not the point of romance series

DEAD SILENCE by S.A. Barnes — cursed space Titanic is a great idea, but it needed to decide if the narrator is crazy or not (instead, author left it vague and confusing)

ALL THAT’S LEFT IN THE WORLD by Erik J. Brown — pretty good, but plot structure was all over the place

AN UNKINDNESS OF GHOSTS by Rivers Solomon — had it brief moments of brilliance, but the world-building and even the action were often too vague

FIRST COMES LIKE by Alisha Rai — this was weird and not very romantic

AKA: it’s not a good book, Susan, it’s just not

THE WOLF AND THE WOODSMAN by Ava Reid — bad plotting, illogical conclusion, world-building was aggravating as hell

NIGHT THEATER by Vikram Paralkar —intriguing, but author could not find a focus within the story

STRANGE BEASTS OF CHINA by Yan Ge — great concept but too slow/sleepy/vague to fully pull it off

THE VALLEY AND THE FLOOD by Rebecca Mahoney — dear white people: this is not how magical realism works

GOOD GIRL COMPLEX by Elle Kennedy — 2012 is calling and would like her poorly written “not like other girls” new adult romance back

IN A GARDEN BURNING GOLD by Rory Power — your cool concept is meaningless if it’s not back up by actual human emotion

I’M SO (NOT) OVER YOU by Kosoko Jackson — the love interest dumps the narrator TWICE with no explanation and takes no accountability for his actions: garbage

PERSEPHONE STATION by Stina Leicht — not enough world-building, character depth, or initial exposition

DAUGHTERS OF A DEAD EMPIRE by Carolyn Tara O’Neil — massively oversimplifies Russian politics to make the Romanovs virtuous martyrs

A THOUSAND STEPS INTO NIGHT by Traci Chee — weirdly juvenile storytelling

WITHIN THESE WICKED WALLS by Lauren Blackwood — a retelling of Jane Eyre which doesn’t actually communicate with the source text

THIS IS HOW YOU LOSE THE TIME WAR by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone — nope

CAN’T RESIST HER by Kianna Alexander — so poorly written that the romance plot didn’t even register

A BOTANIST’S GUIDE TO PARTIES AND POISON by Kate Khavari — everyone in this book is so stupid (the protagonist poisons herself in order to prove the murderer didn’t use poison)

AKA: jail for book! jail for One Thousand Years!!!

A PALE LIGHT IN THE BLACK by K.B. Wagers — propaganda in favor of the American military industrial context, with queer people for set dressing

BITE by K.S. Merbeth — badly written, but also: the love interest sexually assaults the main character

RAMÓN AND JULIETA by Alana Quintana Albertson — the author really thought writing about a gentrifying CEO billionaire was a good idea

GOLD MOUNTAIN by Betty G. Yee — one of the worst written books I’ve ever read (great concept though!)

MR. WRONG NUMBER by Lynn Painter — misogynist hero + jerk heroine + bad writing = not good

CHEROKEE AMERICA by Margaret Verble — a book about “good slaver owners”!!!!!

WE ALL FALL DOWN by Rose Szabo — in which the white protagonist falsely accuses a gay Black man of murder

SILK FIRE by Zabé Ellor — tone-deaf and clumsy story about a man getting revenge against an evil, oppressive matriarchy (also, author appears to be a misogynist)

It’s Complicated

AKA: books I maybe enjoyed but have difficulty categorizing due to problematic stuff

THE MAID by Nita Prose — breezy read but the depiction of autism was so concerning

IF YOU ASK ME by Libby Hubscher — I might have liked this if it had not been FALSELY REPRESENTED as a romance novel (it is not)

SET ON YOU by Amy Lea — this was a great romance…until halfway through it became women’s fic about the heroine’s individual journey (the hero was neither a participant nor a spectator)

PLACES WE’VE NEVER BEEN by Kasie West — it was good but WHY WERE THE ADULTS SO ABUSIVE?!

That was a lot of books. 😳

Let me know in the comments if you have any scientific disagreements with my Highly Official Ranking System (if you dare)!

Did you like this post.

Sign up to get new posts delivered straight to your inbox!

Reader Interactions

July 16, 2022 at 3:47 am

I love this post, such a great way to show off all the books you’ve read so far (and that’s a LOT, I admire you SO much, wow!). I’m so sad that A Thousand Steps Into Night wasn’t that great. I loved Traci Chee’s The Reader series and have been curious about that one. But I’m SO glad to s eethat you’ve read The falling girls, I really liked this book as well! 🙂 Happy reading!! 🙂

adventures of a bibliophile

The worst books i read in 2022, they can't all be winners... here are the losers.

- December 15, 2022

It is time… for the post you have all been waiting for. Today, we are talking about the worst books I read in 2022. Which is honestly one of my most popular posts every year. And hopefully this year’s isn’t too disappointing, because I didn’t read very many books I didn’t like. But I do have a list of six books that I look back on with regret. (Not really, because sometimes it’s more fun to blog about bad books. But you get what I mean.)

Even though this list isn’t long, it makes up for it by containing some of the worst books I’ve read in quite a while. But enough intro, let’s get right to the (bad) books! Here are the worst books I read in 2022, in order from “not that terrible” to “the thought that this got published still makes me mad”:

Comfort Me With Apples by Catherynne M. Valente

I already talked about this one in my most disappointing books of the year list because I really thought I’d enjoy it. And while I didn’t hate it, I was really disappointed and kind of sad after I read it. It’s a thriller that sounded a lot like The Stepford Wives , which I am a fan of. It’s about a woman who lives the perfect life with her perfect husband in their perfect little neighborhood. She knows she was made for him. But strange things start happening and she starts to question just how perfect their world really is. If this reminds you a bit of Don’t Worry Darling , it’s kind of like that.

And I really enjoyed the creepy tone and the mystery in the beginning. But then we started to get clues about where it was going. And I was really hoping it wouldn’t go where I thought it would. But then it did. Basically, it’s a really dark biblical allegory. I wasn’t a huge fan of it. The ending ruined the book for me because not only did I not like it, it was really predictable. When I read weird thrillers, I want to be surprised, I want a good twist. Instead, I spent half the book really wishing it wouldn’t go where I thought it was going. Overall, I wasn’t a huge fan of this one.

Nothing But Blackened Teeth by Cassandra Khaw

I read this book for a post where I read the lowest rated books on my TBR. I ended up scraping the post, but not before getting through this book. To be fair, ti was already on my TBR – I think I just liked the cover. And honestly, I didn’t go into it prepared to not like it just because it has a low rating on Goodreads. I’ve been known to really enjoy some books that other people hate. But this was not one of those books.

I was interested in the idea of a thriller based on Japanese folklore (I’ve been really into Japanese literature for the past couple years). But I think this book tried to fit so much folklore into such a short book that, as someone unfamiliar with the topic, I got kind of lost. I also hated a lot of the characters. Which is fun for a thriller, because then you get to root against them. But this book killed off the least annoying characters. Not going to lie, I was a little disappointed. It also just wasn’t really suspenseful, which is kind of what I look for in horror novels. I did not enjoy it, but it’s definitely not the worst book on this list.

I Love You, But I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins

June was a bad reading month. It gets to claim two of the books on this list, and they’re right next to each other. So you know it wasn’t great. I picked up the next book on this list because of its cover. But this one, I grabbed because of its title. I always hope that the books I give a chance despite having heard nothing about them are good. This one was really not.

It’s supposed to be about womanhood and a woman who leaves her family to go find herself or something. But it’s just chaotic and I had no idea what was going on for most of this book. It spends a lot of time talking about how the main character’s dad was in the Manson cult. I’m pretty sure there wasn’t a point to that, if I remember correctly. Oh, and the main character has the same name as the author. Which just made this book feel extra weird. I don’t remember too much about this book except that I was thinking “WTF is happening?” the entire time I was reading it.

Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin

This was my other terrible book of June, and definitely one I very much regret reading. I talked about it a lot already in my last post . But this book deserves to be on this list, too. Because it was really not good. I was excited to read a dystopian novel with some kickass trans protagonists. But I had so many issues with this book. The fact that the writing wasn’t great was the least of them.

Basically, I thought this book was full of unnecessary violence towards women. It was a lot, and it was very graphic and brutal. I do think violence in books can be used to make a point, but I felt like this author used it so much that it went way beyond just making a point. No book – ever – needs as many rape scenes as this book has. Just no.

I thought the premise of this book was so interesting, but the author completely massacred it with gratuitous violence against women. Even as I’m writing this, I can feel my face morphing into a major look of disgust because that’s how I feel about this book. It says a lot that there are still two books to go on this list.

You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty by Akwaeke Emezi

What do I say about this book? It was probably my most disappointing read of the year because I was really looking forward to this book. I’m a fan of Akwaeke Emezi, and the title of this one definitely drew me in. I wasn’t fully aware that it was a romance book going in, but that’s fine. I like reading romance novels occasionally. But I did not like reading this book.

I really disliked the storyline. There are certain things I hate in romance novels, and this book added to that list. The main character is kind of a terrible person, and the only character development she gets is learning to be okay with being an asshole for the sake of love. I was a little bit let down when her best friend stopped reminding the main character that she was acting like an ass. The sex scenes made me uncomfortable, and I overall kind of hated this book.

But there is one book I hated even more…

Her Heart for a Compass by Sara Ferguson

I do look back on this book with fond memories, so I was a little bit conflicted about where it should go on this list. But any and all enjoyment I derived from reading this book came from writing an entire blog post trashing it . Now, that was fun! This book, though, was just a mess. It’s a five-hundred-plus-page romance novel. Which is not a good start to begin with. Then there’s the fact that Fergie wrote this about her ancestor. And is it just me, or does the idea of that feel a little bit icky?

Not only does Fergie write this about her great-something, but she makes the protagonist an entitled, whiny, helpless, idiot. Like, if you saw an adult acting like this today, you’d wonder how they managed to function before realizing it was because they’re just wealthy and get away with dumb shit. Then there’s the trashing of freaking Queen Victoria, which I am not here for. Lest we forget, this was written by a former member of the royal family. As in, she was married to Queen Victoria’s great-great-great-grandson. Oh, and to make it even worse, the love interest’s name was Donald. I don’t care if it’s historically accurate or whatever, I never again want to read a romance book about a Donald.

Nothing is known about the woman this book is based on except that she existed, got married, had children, and died. So this book is pure speculation. She could have been a secret genius for all we know. I’m just mad this book even got published, and we all know its because they knew a book with a royal’s name on the cover would sell. Which is exactly how I ended up with a signed copy. I’m a sucker.

And we are done with the worst books of the year! Next week, we’ll start getting into all of my favorites, which thankfully outnumber the books on this list. What was the worst book you read this year?

And check out my bookshop , where you can buy books and also shop my curated collections of my personal favorites AND all of the books I’ve read for my reading eperiments. Or you can just buy whatever books you want to. I get a small commission at no extra cost to you, and you get to support your choice of indie bookstores – it’s a win all around!

Click here if you want to check out my bookshop and support this blog!

Share this:

Recent posts.

cozy romance & Black History Month reads

my best reading month in a LONG time!

to read in the Year of the Rabbit

3 responses.

I’m going to have to look back over my 2022 reads soon. Usually, I’m decent at finding books that I love but for some reason I didn’t do great 2022. I think the bad might end up outweighing the good. So, I have too many disappointing books to list right now lol.

Oh no! I’ve definitely had years like that. Hopefully 2023 is better!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Privacy overview.

YA Book Reviews |

- Jan 7, 2023

The BEST and WORST Books I Read in 2022

Updated: Mar 19, 2023

*I have excluded my favorite fantasy books of 2022 from this list because they will be appearing in next week’s blog.

My best books of 2022, 1. razorblade tears by s. a. cosby (adult thriller), what it’s about:, after their two sons (who were married) are murdered buddy lee and ike, who never accepted their sons’ sexualities when they were alive, team up to avenge them., why it’s the best:, i tend to be drawn to morally grey characters and both buddy lee and ike fit that description perfectly. the guilt and grief the two experience feels palpable and cutting. the way their alliance morphs into a genuine friendship captured me. these two also grew so much as characters throughout the story, overcoming their prejudices. this novel has break neck pacing and leaves you dizzy but the raw emotion is never lost. this is a very heavy novel with a lot of trigger warnings (including racism, homophobia and transphobia, misogyny, and violence) but none of it is out of place. still, i do caution you to think carefully before picking up this book. as amazing as it is i don’t think it’s for everyone., 2. carrie soto is back by taylor jenkins reid (adult historical fiction), retired tennis champion carrie soto returns to the game to defend her title from up and coming star nicki chan., i have always given jenkins reid’s historical fiction novels 5 stars. i wondered if this one would be the expectation as i am not a sports person and so the subject matter didn’t interest me one bit. this is a character driver story, though, and so i still found myself being invested. carrie is an abrasive protagonist as she’s cocky, cold, and often cruel. jenkins reid is such a talented writer, however, that she managed to make me root for her still. this is due both to her amazing character arc but also getting to read about her backstory which helps the reader to better understand her. a character doesn’t have to be nice to be well written, after all. the other characters shine as well. i in particular want to shout out love interest bowe who makes carrie a better person and rival nicki who is the only one capable of standing her ground against carrie., 3. we deserve monuments (ya contemporary), avery anderson’s family moves to bardell, georgia to care for her ailing grandmother. while there she falls for local simone but things are complicated by the fact that simone isn’t out., this novel covers a wide variety of topics from racism to generational trauma to grief and sexuality. it manages to juggle all of these well with all the time and care they deserve. there is pain and darkness in this novel but there is also healing and hope. avery is a character that i imagine many young readers will find relatable as she struggles to redefine herself after a bad breakup and a move to a new town. her relationship with her grandmother, mama letty, is the beating heart of this story. i no longer read much ya contemporary, but i will be picking up whatever this author writes next (this is her debut)., 4. the charm offensive by alison cochrun (adult romance), a disgraced tech genius (charlie) becomes the star of a reality tv dating show in order to revamp his image. he ends up falling in love with crew member dev., accurate mental health representation is so important and to get to see two well rounded characters who had the same conditions as me (anxiety disorder and depression) meant the world to someone like me. i was so emotional reading this book because for so long i believed i couldn’t have love in my life because i would be a burden to a partner. this book speared through those insecurities. charlie and dev’s love story is so beautiful because it is filled with passionate moments, dramatic ones, and ones where they are supporting each other through their struggles. this is a book for all those who never get to see themselves in romance books because the truth is we deserve these stories too., 5. the resting place by camilla sten (adult thriller), eleanor has prosopagnosia (face blindness) which renders her incapable of identifying her grandmother’s murderer despite seeing them. she and her boyfriend travel to her grandmother’s estate which her grandmother left her, but they may not be alone there., when it comes to mysteries and thrillers the number one thing that can draw me in is a spooky setting. in particular, i look for houses/manors that have that haunted feeling to them. it’s great if you like to be unsettled and on edge but not outright scared. this book also features the common but for a good reason trope of isolation (there’s a snowstorm trapping them at the estate). something i only recently discovered this year is how i also like unreliable narrators. eleanor has ptsd and this leads to a sense of disquiet and unreality in her pov. the icing on the cake was the ending which had my jaw dropping. i definitely didn’t see it coming, my worst books of 2022, 1.the overnight guest by heather gudenkauf (adult thriller), while writing in an isolated farmhouse during a storm, wylie lark discovers a child whose been in an accident. she brings the child inside but it soon becomes clear someone is after them., why it’s the worst:, this novel is genuinely the most disturbing book i’ve ever read. i should have dnf’d it because it left me feeling sad and disgusted upon finishing it. the past timeline follows a traumatized child who discovers the bodies of her family members and that is not what i signed up for. even if you could look passed all of that then there still isn’t anything worth reading here. the plot and character identities were predictable and wylie’s decisions made no logical sense for her character., 2. reckless girls by rachel hawkins (adult thriller), lux and her boyfriend are hired to take two girls on vacation to a deserted island. when they arrive they find another couple already there. things devolve when a body is found. is there a murderer on the island with them or is one of them the killer, the premise sounds so good, right an isolated setting with a haunting history, strangers, dead bodies. the problem lies with the fact that there is very little of anything that could remotely be considered actual plot to be found in this book. about 90% of the book is shallow characters drinking, relaxing, and partying on a beach. there was none of the tension and mystery and unsettling scenes that i was anticipating. i was bored reading the book and that isn’t how one should feel reading a thriller., 2. they never learn by layne fargo (adult thriller), dr. scarlett clark kills a man who sexually assaults/abuses women on her college campus every year. student carly becomes obsessed with revenge after her roommate is sexually assaulted at a party., in my experience the thriller genre is in the dark ages when it comes to mental health representation. oftentimes they perpetuate that idea that those with mental illness are all dangerous. scarlet, a killer, is portrayed as growing up an awkward outsider with society anxiety. this is so harmful to the mental health community and sickens me. this novel also tries to paint feminism in a very twisted light that is far from favorable. additionally, there are unnecessary scenes of women being assaulted and abused. i understand what fargo’s intentions were, but she missed the mark big time., 3. hench by natalie zina walschots (adult sci-fi), anna is a hench, which means she works for supervillains. when she is fired from her job after a work-related injury she soon finds employment with the most dangerous villain there is., the concept of this book had so much promise and i liked how anna took her pain and turned it into her power. yet somehow anna was the most boring main character ever. she’s bland personality wise and is sidelined during the climax of the novel. the pacing is too meandering and the world building is lacking. finally, the novel’s conclusion was too open ended for a book that is supposed to be a standalone., 5. shadowsong by s. jae-jones (ya fantasy), after her time in the underground falling in love with the goblin king in wintersong, liesel has returned to the surface in this sequel. the underground might not be ready to let her go, though, as the barrier between above and below ground is breaking down., liesel was the least compelling character in this story. in the first book, she is not always likeable but still had her redeeming qualities. her bad qualities much outweigh her good ones in this book, though. the romance was a main part of the plot of the first book but that’s nonexistent here. the goblin king as a character doesn’t really have much of a role at all in this sequel. the overall plot is also just quite boring despite having such promising material to work with. for as much as i liked the first book this wasn’t a good sequel and series conclusion., recent posts.

Taking a Break

As mentioned in a previous blog - My Body is a Battleground (My Journey of Ovarian Surgeries) - I am having surgery to remove a growth that is suspicious for malignancy this month. While I am praying

Here We Go Again by Alison Cochrun (book review)

GENRE: Adult Romance LENGTH: 353 pages PLOT English teachers Logan Maletis and Rosemary Hale are former childhood best friends turned enemies. Their old teacher/father figure Joe Delgado is dying and

My Body is a Battleground (My Journey of Ovarian Surgeries)

While this is primarily a book review blog, I occasionally share my poems here as well. My poetry is how I process the things that happen to me. This one is inspired by the nightmare that began three

Book reviews: 47 of the best novels of 2022

New releases include The Singularities by John Banville and Saha by Cho Nam-Joo

- Newsletter sign up Newsletter

1. The Singularities by John Banville

2. saha by cho nam-joo (trans. jamie chang), 3. bournville by jonathan coe.

- 4. Molly & the Captain by Anthony Quinn

5. Darling by India Knight

6. the passenger by cormac mccarthy, 7. demon copperhead by barbara kingsolver, 8. liberation day by george saunders, 9. lucy by the sea by elizabeth strout, 10. the romantic by william boyd, 11. the marriage portrait by maggie o’farrell, 12. carrie soto is back by taylor jenkins reid, 13. lessons by ian mcewan, 14. the ink black heart by robert galbraith, 15. haven by emma donoghue, 16. trust by hernan diaz, 17. the last white man by mohsin hamid, 18. a hunger by ross raisin, 19. acts of service by lillian fishman, 20. the twilight world by werner herzog, 21. the exhibitionist by charlotte mendelson, 22. vladimir by julia may jonas, 23. to paradise by hanya yanagihara, 24. joan by katherine j. chen, 25. the house of fortune by jessie burton, 26. the seaplane on final approach by rebecca rukeyser, 27. the young accomplice by benjamin wood, 28. the sidekick by benjamin markovits, 29. nonfiction: a novel by julie myerson, 30. you have a friend in 10a by maggie shipstead, 31. very cold people by sarah manguso, 32. trespasses by louise kennedy, 33. elizabeth finch by julian barnes, 34. the candy house by jennifer egan, 35. companion piece by ali smith, 36. young mungo by douglas stuart, 37. sell us the rope by stephen may, 38. french braid by anne tyler, 39. good intentions by kasim ali, 40. the school for good mothers by jessamine chan, 41. pure colour by sheila heti, 42. a previous life by edmund white, 43. a class of their own by matt knott, 44. our country friends by gary shteyngart, 45. scary monsters by michelle de kretser, 46. free love by tessa hadley, 47. the fell by sarah moss.

As the author of three trilogies, John Banville is “no stranger to using recurring characters”, said Ian Critchley in Literary Review . But The Singularities takes this to extremes: so stuffed is it with “old Banville protagonists” that it is close to being a “literary greatest-hits collection”. The setting is Arden House – the crumbling Irish country house from Banville’s 2009 work The Infinities . Various characters from that work are joined by William Jaybey (from The Newton Letter ) and Freddie Montgomery (from The Book of Evidence ), among others. One doesn’t begrudge Banville his “game with his readers”: The Singularities is a “pleasure to read”.

With its “assembly of characters” and country house setting, this novel seems to have the “makings of a whodunnit”, said Tom Ball in The Times . But “no one dies”, or even falls out; and, in fact, little of consequence happens. Fortunately, “you don’t read Banville for his taut plots”. You read him because, every few pages, there’s a sentence “so perfectly contrived it stops you for a moment, achingly, like a beautiful stranger passing in the street”.

Knopf 320pp £14.99; The Week Bookshop £11.99

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The South Korean writer Cho Nam-Joo is best known for her 2016 novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 , said Ellen Peirson-Hagger in The i Paper . A story of “everyday sexism”, it sold more than a million copies in South Korea and sparked a national conversation about the status of women. Cho’s latest novel, Saha , is “just as political” – though this time the focus is on class. Set in a dystopian future, the novel follows a disparate group of characters who live in some dilapidated buildings on the outskirts of “Town”, a fiercely hierarchical “privatised city-nation” where all aspects of life are tightly controlled. Offering a powerful critique of “plutocracy, systemic inequality” and “gendered violence”, the novel is “utterly captivating”.

Cho’s dystopia is “not particularly original”, and her plotting can be “surprisingly loose”, said Mia Levitin in The Daily Telegraph . But the novel’s characterisation is “touching” – and its themes are certainly powerful. At a time of rising global inequality – South Korea’s economy is dominated by “mega-corporations” – this is a book that “resonates widely”.

Scribner 240pp £14.99; The Week Bookshop £11.99

“Few contemporary writers can make a success of the state-of-the-nation novel,” said Rachel Cunliffe in The New Statesman . But one who can is Jonathan Coe. His latest charts 75 years of British history, following the lives of a single family, headed by matriarch Mary Lamb, who live on the outskirts of Birmingham, near the Bournville factory. Coe covers so much ground in just 350 pages by alighting only on key moments: VE Day in 1945; the Queen’s coronation; the 1966 World Cup; the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. The result is a “piercing” satire on Englishness that is “designed to make you think by making you laugh”. This is a warm and comforting book, said Melissa Katsoulis in The Times – like a “mug of hot chocolate”.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The final section, set during Covid-19, is very moving, said J.S. Barnes in Literary Review . But much of this novel is “flat and formulaic”. The use of hindsight is clunky: when Mary visits The Mousetrap in 1953, she thinks: “I imagine it will be closing before very long.” It feels like a “procession through well-worn territory”, rather than something designed to “excite or entertain”.

Viking 368pp £20; The Week Bookshop £15.99

4. Molly & the Captain by Anthony Quinn

Anthony Quinn is a “fine prose stylist, able to evoke the past with vivid immediacy”, said Alex Preston in The Observer . His ninth novel is a sweeping epic that consists of three interlinked sections. In the 1780s, Laura Merrymount – daughter of the Gainsborough-esque portraitist William Merrymount – strives to escape from her father’s shadow and become a painter herself. In Chelsea a century later, we meet the young artist Paul Stransom and his sister Maggie – who abandoned her own dreams of becoming an artist to care for their dying mother. And finally, in 1980s Kentish Town another artist, Nell Cantrip, suddenly acquires late-career fame. Marked by its “intricate”, immaculate plotting, this novel is a “rollicking read”.

I found the plotting a bit predictable, and the characterisation heavy-handed, said Imogen Hermes Gowar in The Guardian . But the book has interesting things to say “about women’s work and talent, and the life cycle of art”; and it is deftly put together by a writer who delights in the “granular details of an era”, while also understanding its broad sweep.

Abacus 432pp £16.99; The Week Bookshop £13.99

India Knight’s new book is a “contemporary reimagining” of Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love , said Christina Patterson in The Sunday Times . Updating “such a beloved novel” certainly isn’t easy – but Knight has pulled off the task with aplomb. In her version, the four Radlett children – Linda, Louisa, Jassy and Robin – are not the progeny of an English lord, but of an ageing and reclusive rock star. Desperate to protect his children from “modern life”, he has purchased a “vast Norfolk estate” – and it’s there that we first encounter Linda and her siblings, through the eyes of their cousin Franny. The narrative tracks their passage to adulthood, and their romantic entanglements – centred on “Linda’s pursuit of love”.

Darling works because, as in Mitford’s original, the details are so “bang on”, said Emma Beddington in The Spectator . Sometimes, Knight artfully tweaks them: she replaces hunting with swimming, and gives her adult characters jobs (Linda runs a café in Dalston). Mitford “diehards can rest easy: your blood vessels are safe with this faithful, fiercely funny homage”.

Fig Tree 288pp £14.99; The Week Bookshop £11.99

Cormac McCarthy’s first novel in 16 years explores “the very boundaries of human understanding”, said Nicholas Mancusi in Time . Investigating a plane crash in the Gulf of Mexico, diver Bobby Western discovers that one passenger is missing; soon he is being harassed by government agents. But the pretence that this is a thriller doesn’t last long: chapters in which Bobby discusses the meaning of life alternate with ones in which his maths genius sister Alice experiences schizophrenic hallucinations. It’s a deeply weird book, held together by “chuckle-out-loud” humour. A companion novel, Stella Maris , focusing on Alice, does little to explain it – but together they are “staggering”.

Sorry, said James Walton in The Times , but I can’t remember a recent novel so wildly indifferent to what its readers might enjoy, or even understand. The conversations that make up the bulk of it, ranging from nuclear physics to Kennedy’s assassination, are a complete ragbag. McCarthy’s gift for description and dialogue remains undiminished, but there’s no escaping the sense that The Passenger is “a big old mess”.

Picador 400pp £20; The Week Bookshop £15.99

Barbara Kingsolver’s latest novel is a retelling of David Copperfield , transposed to the “valleys of southwest Virginia at the height of America’s opioid crisis”, said James Riding in The Times . Demon Copperhead, the “rambunctious hero”, is “born in a trailer to a teenage single mother”, and grows up in a world of neglectful child protection services and dubious guardians. The characters are all recognisable from the Dickens novel – but appear in new guises: “Steerforth becomes Fast Forward, a pill-popping quarterback; Uriah Heep is U-Haul, a football coach’s errand boy”. Daring and entertaining, Demon Copperhead is “shockingly successful” – “like Dickens directed by the Coen brothers”.

It’s a promising premise, not least because in its extreme inequality, post-industrial America resembles Victorian England, said Jessa Crispin in The Daily Telegraph . Yet while Kingsolver closely cleaves to the story of the original, she “breaks the most important rule of working in the Dickensian mode”: the need to “show the reader a good time”. Hers is a retelling “beset by earnestness” – and as a result it falls flat.

Faber 560pp £20; The Week Bookshop £15.99

Besides being a Booker Prize winner with his only novel, Lincoln in the Bardo , George Saunders is “routinely hailed as the world’s best short story writer”, said James Walton in The Daily Telegraph . The American’s dazzling new collection – his first since 2013’s Tenth of December – shows why he garners such acclaim. As is customary in a Saunders collection, quite a few of the tales are “deeply strange”: in the title story, three people are kept permanently “pinioned to a wall”, enacting scenes from American history; another story is set in a theme park that has never received any visitors. Around half the tales, however, explore “recognisable social and political dilemmas”: two employees clashing at work; a mother’s despair about the state of America after her son is pushed over by a tramp. And whether Saunders is engaging with contemporary reality, or “taking us somewhere else entirely”, he never forgets that the most important duty of a writer is to make his work “winningly readable”.

Tenth of December was a “marvellous” collection, but unfortunately Liberation Day doesn’t hit the same heights, said Charles Finch in the Los Angeles Times . Although “the standard of Saunders’ writing remains astronomically high”, there are times here when he seems almost on auto-pilot, reprising themes and situations he has previously explored. It’s true that if you’ve read Saunders before, then parts of Liberation Day will sound “like self-parody”, said John Self in The Times . But then again, “it’s churlish to knock a true original for repeating himself”. When he’s at his best, Saunders’ “oblique, farcical, tragic” view of the world still has the ability to “take the top of your head off”.

Bloomsbury 256pp £18.99; The Week bookshop £14.99

“Elizabeth Strout is writing masterpieces at a pace you might not suspect from their spaciousness and steady beauty,” said Alexandra Harris in The Guardian . Lucy by the Sea is the third sequel to her acclaimed bestseller My Name is Lucy Barton . It takes place early during the pandemic, when Lucy and her ex-husband, William, leave New York for a friend’s empty beach house in Maine – for “just a few weeks”, he says. It is “a study of a later-life reunion between a man and woman who married in their 20s”. It isn’t “a tender tale”, as William isn’t an easy man to like, but it is “as fine a pandemic novel as one could hope for”.

Over the course of three Lucy Barton books, Strout has “created one of the most quizzical characters in modern fiction”, said Claire Allfree in The Times . Still, even this “avid fan” found herself wondering whether this instalment is “surplus to requirements”. This, sadly, is a novel that “mistakes simplistic observation for subtle insight, bathos for pathos”, and Lucy herself is “downright annoying”. I disagree entirely, said Julie Myerson in The Observer . Lucy by the Sea is a wonderful evocation of lockdown life. It is “her most nuanced – and intensely moving – Lucy Barton novel yet”.

Viking 304pp £14.99; The Week Bookshop £11.99

William Boyd’s 17th novel – his first set in the 19th century – is an “old-fashioned bildungsroman” that follows its “hero, Cashel Greville Ross, through a long and peripatetic life”, said Lucy Atkins in The Sunday Times .

After growing up in Ireland and Oxford, Cashel “impulsively joins the army” and finds himself “facing the French bayonets at the Battle of Waterloo”. He subsequently “hangs out” with Byron and Shelley in Italy, spends time in east India and New England, and becomes an opium addict, an author and a diplomat. Although the authorial winks can be groan-inducing – “Shelley can barely swim”, a friend of the poet declares – it is a “masterclass” in narrative construction and its ending is “genuinely poignant”.

Boyd is “as magically readable as ever”, said Jake Kerridge in The Daily Telegraph . But amid the non-stop action and “endless verbal anachronisms”, Cashel never quite emerges as a fully rounded character. Compared with Boyd’s previous “whole life novels”, such as Any Human Heart and Sweet Caress , The Romantic feels “glaringly synthetic”.

Viking 464pp £20; The Week Bookshop £15.99

Maggie O’Farrell’s last novel, the brilliant Hamnet , “fleshed out” the lives of Shakespeare’s children, said Elizabeth Lowry in The Daily Telegraph . Her latest brings another neglected historical figure into the light – the noblewoman Lucrezia de’ Medici. In 1560, a 16-year-old Lucrezia left Florence to begin her married life with Alfonso d’Este, heir to the Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio. “Within a year, she was dead”; it was rumoured Alfonso had killed her. Taking these “suggestive details” as inspiration (as Robert Browning did in his famous poem My Last Duchess ), O’Farrell “constructs a convincing human drama”.