- Importance Of Reading Essay

Importance of Reading Essay

500+ words essay on reading.

Reading is a key to learning. It’s a skill that everyone should develop in their life. The ability to read enables us to discover new facts and opens the door to a new world of ideas, stories and opportunities. We can gather ample information and use it in the right direction to perform various tasks in our life. The habit of reading also increases our knowledge and makes us more intellectual and sensible. With the help of this essay on the Importance of Reading, we will help you know the benefits of reading and its various advantages in our life. Students must go through this essay in detail, as it will help them to create their own essay based on this topic.

Importance of Reading

Reading is one of the best hobbies that one can have. It’s fun to read different types of books. By reading the books, we get to know the people of different areas around the world, different cultures, traditions and much more. There is so much to explore by reading different books. They are the abundance of knowledge and are best friends of human beings. We get to know about every field and area by reading books related to it. There are various types of books available in the market, such as science and technology books, fictitious books, cultural books, historical events and wars related books etc. Also, there are many magazines and novels which people can read anytime and anywhere while travelling to utilise their time effectively.

Benefits of Reading for Students

Reading plays an important role in academics and has an impactful influence on learning. Researchers have highlighted the value of developing reading skills and the benefits of reading to children at an early age. Children who cannot read well at the end of primary school are less likely to succeed in secondary school and, in adulthood, are likely to earn less than their peers. Therefore, the focus is given to encouraging students to develop reading habits.

Reading is an indispensable skill. It is fundamentally interrelated to the process of education and to students achieving educational success. Reading helps students to learn how to use language to make sense of words. It improves their vocabulary, information-processing skills and comprehension. Discussions generated by reading in the classroom can be used to encourage students to construct meanings and connect ideas and experiences across texts. They can use their knowledge to clear their doubts and understand the topic in a better way. The development of good reading habits and skills improves students’ ability to write.

In today’s world of the modern age and digital era, people can easily access resources online for reading. The online books and availability of ebooks in the form of pdf have made reading much easier. So, everyone should build this habit of reading and devote at least 30 minutes daily. If someone is a beginner, then they can start reading the books based on the area of their interest. By doing so, they will gradually build up a habit of reading and start enjoying it.

Frequently Asked Questions on the Importance of Reading Essay

What is the importance of reading.

1. Improves general knowledge 2. Expands attention span/vocabulary 3. Helps in focusing better 4. Enhances language proficiency

What is the power of reading?

1. Develop inference 2. Improves comprehension skills 3. Cohesive learning 4. Broadens knowledge of various topics

How can reading change a student’s life?

1. Empathy towards others 2. Acquisition of qualities like kindness, courtesy

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Why is Reading Important for Your Growth?

Updated: November 22, 2022

Published: September 8, 2019

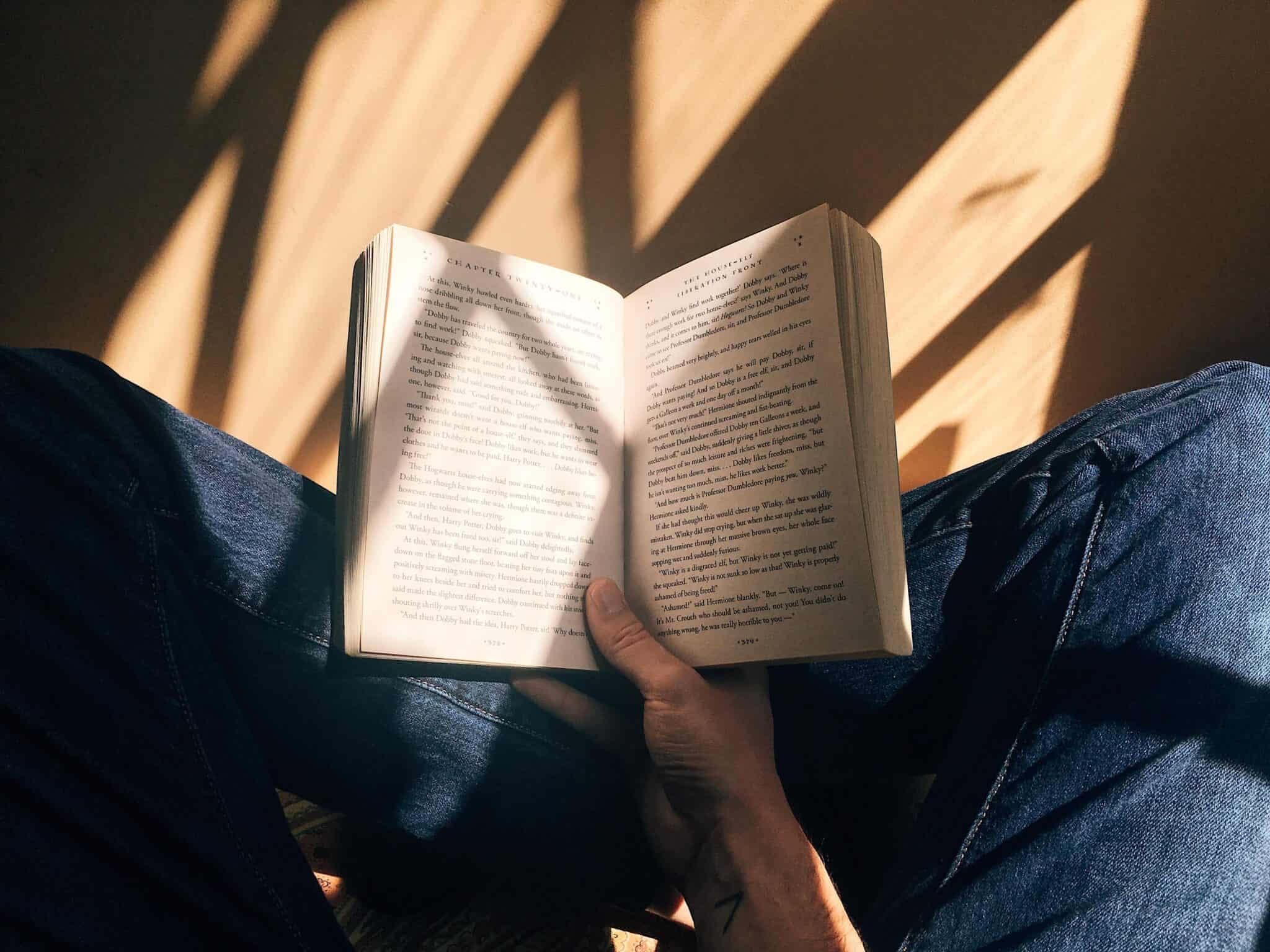

Want to escape without traveling anywhere? Looking to learn about a specific subject? Interested in knowing what it was like to live in the past? Reading can provide all of this and more for you! For anyone who wonders, “why is reading important?” we’re here to share the many reasons.

Yet, there are also some people who read because they are told they must for school. If you fit into that last categorization, then it may be useful to understand the many benefits of reading, which we will uncover here. We’ll also share why people read and what makes it so important.

Now all you have to do is….keep reading!

The Many Benefits of Reading

Beyond reading, because you have to, the importance of reading cannot go unnoticed. Reading is of great value because it provides the means by which you get to:

Strengthens Brain Activity

Reading gets your mind working across different areas. For starters, it involves comprehension to process the words you read. Beyond that, you can use your analytical abilities, stimulate memories, and even broaden your imagination by reading words off a page.

Reading is a neurobiological process that works out your brain muscles. As you do so, you can help to slow down cognitive decline and even decrease the rate at which memory fades. Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley have even found that reading reduces the level of beta-amyloid, which is a protein in the brain that is connected to Alzheimer’s. Who knew that reading could have physical, psychological, and spiritual benefits?

Boosts communication skills

Both reading and writing work to improve one’s communication skills. That’s why if you’re looking to become a better writer, many of the suggestions that you come across will include reading more. Reading can open your eyes, literally and figuratively, to new words. Try this next time you read: if you come across any words you read that you don’t know, take a moment to look them up and write them down. Then, remember to use your new words in your speech so you don’t forget them!

Helps Self-Exploration

Books can be both an escape and an adventure. When you are reading, you have the opportunity to think about things in new ways, learn about cultures, events, and people you may have never otherwise heard of, and can adopt methods of thinking that help to reshape or enhance your identity. For example, you might read a mystery novel and learn that you have a knack and interest in solving cases and paying attention to clues.

Makes One Intellectually Sound

When you read a lot, you undoubtedly learn a lot. The more you read, you can make it to the level of being considered “well-read.” This tends to mean that you know a little (or a lot) about a lot. Having a diverse set of knowledge will make you a more engaging conversationalist and can empower you to speak to more people from different backgrounds and experiences because you can connect based on shared information. Some people may argue that “ignorance is bliss,” but the truth is “knowledge is power.” And, the more you read, the more you get to know! That’s why you can bet that any educational degree you choose to obtain will involve some forms of reading (yes, even math and computer science) .

It’s no wonder why you may see people reading by the pool, on the beach, or even on a lazy Sunday afternoon. Reading is a form of entertainment that can take you to fictional worlds or past points in time.

Imparts Good Values

Reading can teach values. Whether you read from a religious text or secular text, you can learn and teach the difference between right and wrong and explore various cultural perspectives and ways of life.

Enhances creativity

Reading has the potential to boost your levels of creativity. Whether you read about a specific craft or skill to boost it or you are reading randomly for fun, the words could spark new ideas or images in your mind. You may also start to find connections between seemingly disparate things, which can make for even more creative outputs and expressions.

Lowers Stress

If you don’t think that strengthening your brain is enough of a benefit, there’s even more good news. Reading has also been proven to lower stress as it increases relaxation. When the brain is fully focused on a single task, like reading, the reader gets to benefit from meditative qualities that reduce stress levels.

A Look at the Most Popular Books

As we celebrate World Book Day, take a look at some of the most popular books of all time. These should give you an idea of what book to pick up next time you’re at a library, in a bookstore, or ordering your next read online.

- The Harry Potter Series

- The Little Prince

- The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

- The Da Vinci Code

- The Alchemist

The Gift of Reading

Whether you had to work hard to learn to read or it came naturally, reading can be considered both a gift and a privilege. In fact, we can even bet that you read something every single day ( this blog, for instance), even if it’s not a book. From text messages to signs, emails to business documents, and everything in between, it’s hard to escape the need to read.

Reading opens up doors to new worlds, provides entertainment, boosts the imagination, and has positive neurological and psychological benefits. So, if anyone ever asks or you stop to think, “why is reading important” you’re now well-read on the subject to provide a detailed response and share your own purpose of reading!

Related Articles

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Why Reading Is Important for Children’s Brain Development

Early childhood is a critical period for brain development , which is important for boosting cognition and mental well-being. Good brain health at this age is directly linked to better mental heath, cognition, and educational attainment in adolescence and adulthood. It can also provide resilience in times of stress.

But, sadly, brain development can be hampered by poverty. Studies have shown that early childhood poverty is a risk factor for lower educational attainment. It is also associated with differences in brain structure, poorer cognition, behavioral problems, and mental health symptoms.

This shows just how important it is to give all children an equal chance in life. But until sufficient measures are taken to reduce inequality and improve outcomes, our new study, published in Psychological Medicine , shows one low-cost activity that may at least counteract some of the negative effects of poverty on the brain: reading for pleasure.

Wealth and brain health

Higher family income in childhood tends to be associated with higher scores on assessments of language, working memory, and the processing of social and emotional cues. Research has shown that the brain’s outer layer, called the cortex, has a larger surface area and is thicker in people with higher socioeconomic status than in poorer people.

Being wealthy has also been linked with having more grey matter (tissue in the outer layers of the brain) in the frontal and temporal regions (situated just behind the ears) of the brain. And we know that these areas support the development of cognitive skills.

The association between wealth and cognition is greatest in the most economically disadvantaged families . Among children from lower-income families, small differences in income are associated with relatively large differences in surface area. Among children from higher-income families, similar income increments are associated with smaller differences in surface area.

Importantly, the results from one study found that when mothers with low socioeconomic status were given monthly cash gifts, their children’s brain health improved . On average, they developed more changeable brains (plasticity) and better adaptation to their environment. They also found it easier to subsequently develop cognitive skills.

Our socioeconomic status will even influence our decision making . A report from the London School of Economics found that poverty seems to shift people’s focus toward meeting immediate needs and threats. They become more focused on the present with little space for future plans—and also tended to be more averse to taking risks.

It also showed that children from low-socioeconomic-background families seem to have poorer stress coping mechanisms and feel less self-confident.

But what are the reasons for these effects of poverty on the brain and academic achievement? Ultimately, more research is needed to fully understand why poverty affects the brain in this way. There are many contributing factors that will interact. These include poor nutrition and stress on the family caused by financial problems. A lack of safe spaces and good facilities to play and exercise in, as well as limited access to computers and other educational support systems, could also play a role.

Reading for pleasure

There has been much interest of late in leveling up. So what measures can we put in place to counteract the negative effects of poverty that could be applicable globally?

Our observational study shows a dramatic and positive link between a fun and simple activity—reading for pleasure in early childhood—and better cognition, mental health, and educational attainment in adolescence.

We analyzed the data from the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) project, a U.S. national cohort study with more than 10,000 participants across different ethnicities and and varying socioeconomic status. The dataset contained measures of young adolescents ages nine to 13 and how many years they had spent reading for pleasure during their early childhood. It also included data on their cognitive health, mental health, and brain health.

About half of the group of adolescents started reading early in childhood, whereas the others, approximately half, had never read in early childhood, or had begun reading later on.

Meet the Greater Good Toolkit for Kids

28 practices, scientifically proven to nurture kindness, compassion, and generosity in young minds

We discovered that reading for pleasure in early childhood was linked with better scores on comprehensive cognition assessments and better educational attainment in young adolescence. It was also associated with fewer mental health problems and less time spent on electronic devices.

Our results showed that reading for pleasure in early childhood can be beneficial regardless of socioeconomic status. It may also be helpful regardless of the children’s initial intelligence level. That’s because the effect didn’t depend on how many years of education the children’s parents had had—which is our best measure for very young children’s intelligence (IQ is partially heritable).

We also discovered that children who read for pleasure had larger cortical surface areas in several brain regions that are significantly related to cognition and mental health (including the frontal areas). Importantly, this was the case regardless of socioeconomic status. The result therefore suggests that reading for pleasure in early childhood may be an effective intervention to counteract the negative effects of poverty on the brain.

While our current data was obtained from families across the United States, future analyses will include investigations with data from other countries—including developing countries, when comparable data become available.

So how could reading boost cognition exactly? It is already known that language learning, including through reading and discussing books, is a key factor in healthy brain development. It is also a critical building block for other forms of cognition, including executive functions (such as memory, planning, and self-control) and social intelligence.

Because there are many different reasons why poverty may negatively affect brain development, we need a comprehensive and holistic approach to improving outcomes. While reading for pleasure is unlikely, on its own, to fully address the challenging effects of poverty on the brain, it provides a simple method for improving children’s development and attainment.

Our findings also have important implications for parents, educators, and policymakers in facilitating reading for pleasure in young children. It could, for example, help counteract some of the negative effects on young children’s cognitive development of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

About the Authors

Barbara jacquelyn sahakian.

Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian, Ph.D. , is a professor of clinical neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge.

Christelle Langley

Christelle Langley, Ph.D. , is a postdoctoral research associate in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Cambridge.

Jianfeng Feng

Jianfeng Feng, Ph.D. , is a professor of science and technology for brain-inspired intelligence/computer science at Fudan University.

Yun-Jun Sun

Yun-Jun Sun, Ph.D. , is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-Inspired Intelligence at Fudan University.

You May Also Enjoy

A Feeling for Fiction

Changing our Minds

Nine Picture Books That Illuminate Black Joy

Eight of Our Favorite Asian American Picture Books

How Reading Fiction Can Shape Our Real Lives

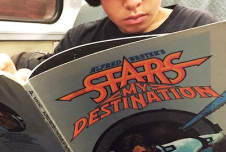

How Reading Science Fiction Can Build Resilience in Kids

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Science of Reading and Its Educational Implications

Mark s. seidenberg.

Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Research in cognitive science and neuroscience has made enormous progress toward understanding skilled reading, the acquisition of reading skill, the brain bases of reading, the causes of developmental reading impairments and how such impairments can be treated. My question is: if the science is so good, why do so many people read so poorly? I mainly focus on the United States, which fares poorly on cross-national comparisons of literacy, with about 25-30% of the population exhibiting literacy skills that are low by standard metrics. I consider three possible contributing factors, all of which turn on issues concerning the relationships between written and spoken language. They are: the fact that English has a deep alphabetic orthography; how reading is taught; and the impact of linguistic variability as manifested in the Black-White “achievement gap”. I conclude that there are opportunities to increase literacy levels by making better use of what we have learned about reading and language, but also institutional obstacles and understudied issues for which more evidence is badly needed.

Is there an area in cognitive science and cognitive neuroscience that has been more successful than the study of reading? Let's not underestimate the amount that has been learned. We, the community of scientists who study reading (including my colleagues Perfetti and Treiman, whose own research is described in accompanying articles) understand the basic mechanisms that support skilled reading, how reading skill is acquired, and the proximal causes of reading impairments.

We understand the fundamental problem facing the beginning reader: how to relate a new code, a written script, to an existing code, spoken language. We know which behaviors of 4 year old pre-readers are strong predictors of later reading ability, how children make the transition from pre-reader to reader, and the obstacles that many encounter. We know what distinguishes good and poor readers, younger and older skilled readers, “typical” readers from those who are atypical because of either constitutional factors (such as a hearing or learning impairment) or environmental ones (for example, poor schooling or poverty).

We know how basic skills that provide the child's entry into reading relate to other types of knowledge and capacities that support comprehending texts of increasing variety and difficulty. We understand that some aspects of reading are universal (because people's brains are essentially alike) and that some are not (because of differences among writing systems and the languages they represent).

Neuroimaging studies have been successful in identifying the main brain circuits involved in reading and the anomalous ways they develop in dyslexics, and several probable causes of such impairments. We have computational models that specify the mechanisms that underlie basic reading skills, how children acquire them, and how differences in experience (with spoken language and reading) and individual differences (in learning and memory capacities, motivation and other factors) result in varied reading outcomes. This vast research base has led to the development of intervention and remediation methods that can reliably help many children who need it. Researchers disagree about many details—it's science, not the Ten Commandments—but there is remarkable consensus about the basic theory of how reading works and the causes of reading successes and failures (for reviews, see Rayner et al., 2001; Pennington, 2006 ; Morris et al., 2010; Gabrieli, 2009 ; Pugh et al., 2012 ).

My question, then, is this: if the science is so advanced, why do so many people read so poorly? In America not long ago we had a “Sputnik moment,” occasioned by the release of the results of the 2009 round of the PISA cross-national assessments of the academic performance of 15 year olds (OECD PISA, 2009). As in previous years, US performance was close to the average for the 34 OECD countries. However, this round was the first to include data from Shanghai and Singapore, which along with Korea, Hong Kong, and Japan, scored higher than the US. These findings received far more attention than the fact that for many years the US has scored lower than countries such as Canada, Australia, Finland and New Zealand on the PISA exercise. The president, the secretary of education, and the commentariat (e.g., Finn, 2009) all treated the results as evidence of a crisis in American education that called for immediate action. But 2010 was not 1957 and so the second “Sputnik moment” passed quickly, rapidly dropping out of public discourse ( Fig. 1 ).

Number of times the phrase “sputnik moment” was uttered on CNN, an American cable news network over a two year period. The Larege spike followed the release of results from the 2009 PISA assessment and coincided with President Obama's 2011 State of the Union address.

Although the PISA results made the news, there is plenty of in-house data about the literacy problem in the US, posted on the Department of Education's web site ( http://ies.ed.gov ). The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (2003) found that about 93 million adults read at “basic” or “below basic” levels. At these levels, a person might be able to find the listing for a television program on cable TV, but not understand the instructions and warnings that come with their blood pressure medication ( Lesgold & Welch-Ross, 2012 ). Results on the NAEP (“the nation's report card”) document the origins of low literacy in the performance of 4 th and 8 th graders ( http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard ). Like everything else about education in the US, this assessment exercise has been the focus of controversy, with different stakeholders spinning the data in different ways. People who emphasize how well American education is doing point to the finding that since 1992, when the modern form of the NAEP was introduced, between 59-67% of 4 th graders and 69-76% of 8 th graders scored at the “basic” level or higher. People who think we should be doing better—I am in this camp—can point to the fact that 66-71% of 4 th graders and 66-71% of 8 th graders scored at “basic” or “below basic” levels. Put another way, there are far too many children scoring in the lowest tier (about a third of the 4 th graders and a quarter of the 8 th graders are “below basic”), and far too few in the highest (6-8% of the 4 th graders and a mere 3% of the 8 th graders are “advanced” readers by this measure). The American polity is in a test-happy phase and so there is much other data about who can read and how well than can be reviewed here. It is fair to say that assessments of adults and children consistently indicate that large numbers of individuals in the US read poorly, and that this has been true for many years.

Low literacy's consequences for the affected individuals and for society are vast, as we all know. It creates serious challenges to fully participating in the workforce, managing your own health care, and advancing your children's education. Looking at these facts, and knowing something about how reading works, I've asked myself whether our science has anything to contribute to improving literacy outcomes in this country and others. It might not. Literacy failure could be due to factors well outside the boundaries of this science: poverty, for example. Poverty has many sequelae, including higher infant mortality rate, atypical brain development, shorter life span, worse health and health care, higher crime and incarceration rates, lower educational achievement, higher dropout rates, poorer schools with less experienced teachers and toward the bottom of a list that could go on much longer, poor reading ( General Accounting Office, 2007 ). Surely reducing poverty would have a bigger impact on literacy than anything inspired by our research. Any person with a politically-acceptable plan to substantially reduce or eliminate poverty should step forward immediately.

If poverty were all that mattered, this article could end here. However, the relationship between socioeconomic status and reading achievement is not simple. It is difficult to isolate effects of SES (itself a complex construct; Duncan & Magnuson, 2005 ) from the many other factors with which it is correlated. Nonetheless, data from a variety of sources suggest that there is much about observed literacy outcomes that SES does not explain. I return to this issue in the final section of this article in the context of the Black-White “achievement gap”, where the confound between SES and achievement is of particular concern. Here I merely want to cite some representative findings suggesting that although poverty has enormous impact, it is not the whole story.

The PISA assessments provide a wealth of data (so to speak) about the relationship between national wealth and reading performance. The 2009 data set includes multiple measures related to a country's economic health for a core group of 34 OECD countries. The main findings are quite interesting. 1 In brief, two economic factors, the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and amount spent on education, are only weakly related to reading performance. The proportion of socio-economically disadvantaged students in each country has a bigger impact, with higher proportions associated with lower scores. However, the US does not score poorly because lower income students are overrepresented; in fact, the US clusters with many OECD countries on this measure, and reading scores in this group vary widely. It is also of interest that parents' education level is a much stronger predictor than economic indicators across countries. Of course, it takes more complex analyses to identify relations among such factors and their relative contributions. Nonetheless, even these descriptive data indicate that both SES and other factors are important determinants of outcomes.

The NAEP assessment also includes information regarding the moderating effects of a variety of factors, including race/ethnicity, gender, and eligibility for subsidized or free school lunch, a common (though rough) proxy for SES. 2 Again there are strong indications that both SES and other factors affect outcomes. There is a large, consistent effect of SES as indexed by the subsidized lunch proxy in every year of testing. However, there are similar results for other factors, such as gender. Females have scored significantly higher than males in every year of NAEP testing. Females also scored significantly higher than males in every participating country/municipality in the 2009 PISA assessment. (The US had one of the smaller gender gaps, whereas Finland, a perennial high-scoring country, had one of the largest.) The gender differences within and across countries may be related in some complex manner to SES, but the consistency of the effect across countries with widely varying economic profiles suggests that SES is not the main determinant.

Insofar as the US does not seem likely to substantially reduce or eliminate poverty any time soon and SES is not the only factor affecting reading outcomes, this article will not end here. To restate the question: what are the main causes of reading failures in the US (and perhaps other countries where similar conditions exist) and does reading science have anything to contribute to substantially reducing them, the considerable impact of poverty notwithstanding? I'll consider this question by examining three quite different kinds of factors often thought to be relevant to literacy outcomes in the US.

Blame English?

One possibility is that a certain number of people are doomed to fail to learn to read well because of intrinsic properties of English. The child's initial task is to learn how the written code relates to the spoken language they already know. The writing system is alphabetic, and we tell beginning readers that letters correspond to sounds, but then we teach them early reading vocabulary that includes HAVE, GIVE, SAID, SOME, WAS, WERE, IS, ME, ONE, WHO, SCHOOL, and many other words with atypical spelling-sound correspondences. These inconsistencies are a much commented-upon property of English. Other alphabetic writing systems are indeed more consistent at this level of analysis, many of them conforming (to a very high degree but not perfectly) to the principle that each symbol in the writing system (a “grapheme” consisting of one or more letters) correspond to a single unit (a phoneme) in the spoken language. English is said to be a “deep” orthography, whereas Italian, German, Russian, Finnish, Korean, Serbo-Croatian, and many other alphabets are “shallow” ( Katz & Frost, 1992 ). Written English is obviously a workable system but the learning curve is steep and a greater proportion of individuals may be left behind than if the writing system were shallow.

This hypothesis is contradicted by the consistently high reading achievement in countries such as Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and Singapore where English is also the main language of instruction (Quebec exception duly noted). Although these results suggest that written English is not the whole problem, perhaps performance would be even higher in these countries (and the US) if it were not so peculiar. These cross-national findings are correlational of course. What is needed is more direct evidence as to whether it is easier to learn to read in shallow alphabetic orthographies, holding other factors aside to the extent possible.

Researchers in many countries have attempted to address this question. By now it is quite clear that it is easier to learn to read words and nonwords aloud in shallow alphabetic orthographies compared to English (for reviews, see Aro & Wimmer, 2003 , and several chapters in Snowling & Hulme, 2005, and in Joshi & Aaron, 2006). The advantage for shallow orthographies has been observed in Italian, Spanish, German, French, Finnish, Serbian, Turkish and other languages. “Learning to read in Albanian” is “A skill easily acquired” according to Hoxhallari et al. (2004) because the alphabet is so shallow. Children know the full set of spelling-sound correspondences for Finnish, which has a shallow orthography, by the time formal schooling commences (at age 7 following a compulsory year of preschool). 3 Tested on their skill at reading words and nonwords aloud, children in Wales learning to read in Welsh (which has a shallow alphabetic script) outperform children from the same area who are learning to read in English ( Hanley et al., 2004 ). The Welsh studies permitted comparisons that excluded many potentially confounding socioeconomic and cultural factors. Such studies suggest in short, that shallow is easier. Share (2008) argues that theories of reading have been led astray because of overreliance on studies of English, an “outlier” among writing systems. Perhaps there would be higher literacy achievement in the US if the writing system were more like Finnish or Albanian.

I don't think so. For one thing, this comparative research on reading acquisition makes the mistake of equating the task of reading words and nonwords aloud with “reading” (as in Aro & Wimmer, 2004, Spencer & Hanley, 2003, and many other studies). Children are sometimes called upon to read aloud, in classrooms and in experiments; reading aloud provides overt evidence about the child's knowledge of words and the opportunity to provide explicit feedback (e.g., corrections of mispronunciations). Because of the nature of the writing system, the child's ability to name words and nonwords aloud in English is a major step in reading acquisition. The task has also provided a domain in which to explore statistical learning procedures (Harm & Seidenberg, 1999) that are relevant to language acquisition, visual cognition, and much else. The goal of reading, however, is comprehension. Reading aloud is much more strongly related to comprehension in English than in shallow orthographies (see, e.g., Lindgren, deRenzi, & Richman, 1985 ). In shallow orthographies, reading aloud can be achieved without comprehending what is being said, indeed without knowing the language. I know this to be true because I proved it at my Bar Mitzvah. Modern Hebrew can be written with or without vowels. With the vowels included, the writing system is shallow: words have simple and consistent spelling-sound correspondences, which can be learned rapidly, comprehension not required. Fortuitously, Hebrew is a good “Bar Mitzvah language” ( Seidenberg, 2011 ), as are Finnish, Albanian, Welsh, Italian and other shallow alphabetic orthographies.

One would not want to confuse barking at print with reading comprehension, however. Phil Gough would not have. According to his “simple view of reading” ( Hoover & Gough, 1990 ), children's reading comprehension is a function of decoding skills (recognizing letters, relating print to sound) and knowledge of spoken language (vocabulary and grammar). These skills are dissociable. If the writing system is sufficiently shallow, a person can learn to read aloud without comprehension (my Hebrew). Conversely, a person can know a spoken language quite well without being able to read it (as is true of most 5 year olds who speak English). Among clinicians and researchers, there is a move to reserve the term “dyslexia” for a developmental reading impairment that interferes with acquiring basic print-related skills, especially ability to relate print to sound, independent of spoken language comprehension ( Snowling & Hulme, 2011 ). Other children acquire adequate decoding skills but comprehend texts poorly; these children are also “poor readers,” but a different diagnostic category is needed because their poor reading comprehension is secondary to deficiencies in spoken language.

Granted that it is easy to learn to decode in shallow orthographies, does this confer a comprehension advantage as well? Few studies have closely examined reading aloud, reading comprehension, and spoken language abilities in the same children, although there are some interesting leads. The studies of children learning to read in Welsh and English yielded an interesting tradeoff: whereas the Welsh children performed much better at reading common words and simple nonwords aloud, the English children scored higher when tested on comprehension. As Hanley et al. (2004) noted, “This result suggests that a transparent orthography does not confer any advantages as far as reading comprehension is concerned. As comprehension is clearly the goal of reading, this finding is potentially reassuring for teachers of English” (p. 1408). Why the English children exhibited better comprehension with poorer reading aloud cannot be determined with certainty from these studies. The comparison between Welsh-learning and English-learning children is not entirely clean because the sociolinguistic context is such that English is the dominant language. The Welsh-learning children therefore have substantial knowledge of English (and are bilingual to some degree), whereas the English-learning children have much less knowledge of Welsh and are essentially monolingual. What is clear is that ability to read aloud may say little about the child's reading comprehension.

Durgunoğlu (2006) reached a similar conclusion from extensive studies of reading in Turkish. Turkish has a shallow orthography and a complex, highly productive agglutinating morphology. Summarizing, she noted that “Phonological awareness and decoding develop rapidly in both young and adult readers of Turkish because of the transparent orthography and the special characteristics of phonology and morphology. However, reading comprehension is still a problem.” (2006, p. 226). In her experiments, children's comprehension lagged substantially behind their ability to pronounce words aloud, which she attributes to properties of the spoken language, specifically that complex morphological system, which takes native speakers many years to learn. Whereas comprehension develops more rapidly than production in learning a first language, shallow orthographies create the opposite effect: production—reading aloud—can advance more rapidly than comprehension.

Even within English, accuracy in reading aloud and reading comprehension frequently decouple. Skilled readers are able to read and comprehend many words they mispronounce. Here are some I collected from students and colleagues—words they did not know how to pronounce or systematically mispronounced for many years:

All true. A graduate student who spent a portion of his youth immersed in the computer game Chaos: The Battle of Wizards didn't realize until much later that it was connected to the spoken form /ke i -αs/. The two pronunciations of URANUS seem to be in free variation in the US. People can be more adept at engaging in coitus than pronouncing it. A personal example: the Seidenberg and McClelland (1989) model learned to pronounce QUAY as /kwe i / because the training lexicon was created by hand and that is how I thought it was pronounced (it was corrected in later models). As a land-locked kid growing up on the south side of Chicago, I knew the word from reading but not speech. These cases show that a person can know the meaning of a written word but lack secure knowledge of the pronunciation. People frequently generate erroneous pronunciations that they would not have heard in spoken language. If words like these were used in a reading-aloud experiment, even adult, highly skilled readers of English would perform more poorly than Welsh or Turkish subjects.

Nation and Cocksey (2009) found that 7 year old English-speaking children often know the meanings of words they incorrectly read aloud. Familiarity with the spoken form of a word (as indexed by auditory lexical decision performance) was related to accuracy in reading it aloud, especially for words with irregular spelling-sound correspondences. Across subjects, 521 words were read aloud incorrectly; the correct definition was provided for 328 of them (63%). Of course the fact that ability to comprehend and pronounce words can dissociate should have been obvious from the mere existence of severely hearing impaired deaf individuals who do not receive oral training, do not know the pronunciations of words, but are nonetheless good readers. (The fact that it difficult to become a skilled reader under these conditions is an important but separate issue; Goldin-Meadow & Mayberry, 2001 ).

In summary, reading aloud is not a good index of reading comprehension or a basis for evaluating “ease of learning to read” different writing systems. We should therefore be skeptical of claims that it is easy to learn to read in shallow orthographies, and of the corollary belief that English is especially difficult. Over the past 20 years or so, researchers in many countries have correctly recognized the importance of obtaining data about reading in languages other than English, but attempted to correct the imbalance by replicating studies that had been conducted in English using reading aloud, a task that is more closely related to comprehension in that language precisely because of orthographic idiosyncrasies they were trying to surmount.

The relationship between writing systems and spoken languages

The orthographic depth hypothesis is an example of a very interesting idea that drew attention to an important issue (differences in how writing systems represent phonology and their potential impact on reading) and stimulated an enormous amount of research but turned out to be wrong. The hypothesis narrowly focused on the computation of phonology from print. Given the dependence of reading on spoken language, it seemed to follow that writing systems for which it was easier to compute phonology, the shallow ones, would also be easier to comprehend, other factors being equal. This prediction did not turn out to be correct because other factors are manifestly unequal. Looking across languages and writing systems, it can be seen that the properties of writing systems are related to properties of the languages they represent, in particular the complexity of the language's inflectional morphology. Inflectional morphology is an especially important component of language because it is an interface system conveying information about words and the syntactic structures in which they participate, and a major source of typological variation. Languages such as Welsh and Turkish have shallow writing systems but they are morphologically complex, marking properties such as case, number and gender. English and the Sinitic languages (Mandarin, Taiwanese, Cantonese, et al.) exhibit the opposite pattern: the writing systems are deep but their inflectional systems are simple. Looking at English, Gough had observed that early reading comprehension is a function of knowledge of print and knowledge of spoken language. With a cross-linguistic perspective it becomes clear that the two components are not independent. What has to be learned about print depends on properties of the writing system, which bear a non-arbitrary relationship to spoken language typology.

I have attempted to unify these broad cross-linguistic tendencies under the concept of “grapholinguistic equilibrium” ( Seidenberg, 2011 ). The writing systems that have survived support comprehension about equally well. A writing system's capacity to support comprehension can be thought of as a constant that is maintained via trade-offs between orthographic complexity (“depth”, number and complexity of symbols, etc.) and spoken language complexity (particularly morphosyntactic). For languages such as Welsh or Turkish, the spelling-sound correspondences are easily learned, but the morphology is not. These conditions allow children to accurately read aloud sentences that they would not be able to produce or fully comprehend given their still-developing knowledge of the spoken language. Written English is deep but the inflectional system is trivial and little impediment to comprehension. Under these conditions, children easily produce and comprehend sentences that they cannot accurately read aloud.

A deep orthography would be highly dysfunctional, possibly unlearnable, in languages with complex morphosyntax. To illustrate consider Serbo-Croatian. Classic studies focused on its highly consistent spelling-sound correspondences, so different from those in English ( Katz & Frost, 1992 ). My colleagues and I have been more interested in its inflectional system ( Mirković et al., 2004 , 2011 ), which is also very different from English. The system is unquestionably complex. Both nouns and verbs are inflected and there are inflections for number, gender, case, and tense. The inflections are not independent: Number on nouns, for example, depends on case and gender. The inflections are not discrete beads on a string, either: the system is fusional, such that a single suffix encodes multiple inflections. Then there is an additional wrinkle: the realization of an inflection depends on phonological properties of the root to which it is attached ( Table 1 ). The base form SAVETNIK (masculine, “advisor”) is zero-inflected. The final consonant K [/k/] is not retained throughout the inflectional paradigm, changing to C [/ts/] and Č [/tʃ/]. The inflection –E is used for both the vocative singular and the accusative plural; in the former, it is preceded by Č, in the latter by K. It is clear even from this sliver of the language that there is a lot to learn.

Note: All forms are masculine gender. K = /k/ as in Kevin, Č = /t?/ as in “church,” C = /ts/ as in “pizza.”

Now imagine trying to read this language in a script that is more like English, with single letters that represent multiple vowels (e.g., DOSE, LOSE, POSE). Then toss in a few random consonants with multiple pronunciations, such as C (as in CAP and CENT), G (GOAT, GIN), and Y (YOUNG, EDGY). The complexity of the inflectional system is already high. Adding ambiguity in the pronunciations of written letters would increase it enormously. The proper form of an inflection depends on the pronunciation of the previous consonant, but now the pronunciation of the letter representing that consonant will sometimes also depend on context (as with the ambiguous English letters). There would be further penalties if mastery of a complex morphological system requires formal instruction that itself involves reading.

It would take quantitative analyses or simulation models to determine the effects of additional orthographic indeterminacy and establish when the system would become intractable for human learners. The historical fact that languages with complex morphological systems have shallow orthographies is itself suggestive of pressures to maintain this equilibrium, however. Indeed, many times the alignment of language and writing system has been achieved with active intervention, as with the Armenian alphabet in the fifth century, Hangul in 15th century Korea, and Serbo-Croatian in the 19 th century (see Daniels & Bright, 1996 ).

In summary, there is no free orthographic lunch. The child does gain entry into reading more quickly if the associations between units in the written and spoken languages are simple and consistent. However, learning to read aloud in shallow writing systems is a bit like learning to play the violin in the Suzuki method. Both allow the child to rapidly begin performing with relatively little instruction. A four year old's performance of the “Twinkle Variations” may well be the musical equivalent of barking at print. Being able to pronounce words aloud is a helpful skill to possess if your task is to learn a complex, quasiregular morphological system over a many-year period that extends into formal schooling. But, there is little evidence that precocious knowledge of spelling-sound correspondences confers a comprehension advantage, or that the irregularities in written English present an especial burden. 4

What About How Reading is Taught?

American educators have never been able to settle on how to teach children to read. The issue has been debated since Horace Mann was head of the Massachusetts Board of Education in the 1840s. Mann described letters as “skeleton-shaped, bloodless, ghostly apparitions” and encouraged teaching children to read whole words at a time—a lesson that “would be like an excursion to the fields of Elysium” compared to other practices. Mann's tone—authoritative assertion coupled with contempt for other views—is characteristic of much of the subsequent 150 years of debate. 5

How much of the literacy problem in America is due to the way reading has been taught? Everyone knows about the “reading wars” of the past 30 years–the debate over “phonics” and “whole language” approaches. The 2000s saw the emergence of a compromise called “Balanced Literacy,” said to incorporate the best aspects of the two approaches. “Balanced literacy” is a Treaty of Versailles solution that allowed educators to declare the increasingly troublesome “wars” over without having seriously addressed the underlying causes of the strife. The issues are complex, controversial, and ongoing. Here I want to briefly examine some basic considerations, from the perspective of a scientist who studies how reading works, which suggest that how reading is taught is indeed a significant part of the literacy problem in the US and other countries. There are three main points: (a) Contemporary reading science has had very little impact on educational practice mainly because of a two-cultures problem separating science and education; (b) This disconnection has been harmful. Current practices rest on outdated assumptions about reading and development that make learning to read harder than it needs to be, a sure way to leave many children behind; (c) Connecting the science to educational practice would be beneficial but is extremely difficult to achieve. The current environment limits the amount of collaborative work at the all-important translational interface. In the US, the conflicting and often strongly entrenched interests of various stakeholders—educators, politicians, scientists, taxpayers, labor organizations, parent groups—make it hard to achieve meaningful change within the existing institutional structure of public education.

My comments about the culture of education (by which I mean beliefs and attitudes about how children learn and the functions of schooling, particularly with respect to reading) may seem harsh to readers who are not close to the issues. Many people will naturally assume that although scientists and educators may have different views, both have much to contribute and the path to greater progress is through cooperation. Every academic is aware of the importance of interdisciplinary work and of the challenges involved in communicating across disciplines. We also know that the successful creation of cross-disciplinary bridges can have transformative effects, sometimes leading to the emergence of new fields that are much more than the sum of the disciplinary parts. Such a transformation is needed in education and I hope it can be achieved. The question is how. It may be hard for people who are unfamiliar with the landscape to appreciate just how difficult the challenges are. As someone who has been immersed in these issues for many years I have struggled with finding ways to have a positive impact, and that is reflected in the material that follows (see also Seidenberg, 2012).

You may believe, as I usually do, that the collegial and politically-astute approach is to assume that well-intentioned individuals can transcend their differences in the service of a shared goal. Disciplinary barriers only exist as long as we allow them to. We can all do better jobs communicating what we do and what we've learned. Bridges are built on a foundation of mutual respect for individuals and diverse viewpoints. People are doing the best they can; neither side knows everything. I fully support creative bridge-building and have engaged in it myself, but I have come to question whether good intentions and greater effort can be any more effective going forward than they have been in the past. These positive and sincere impulses might have a better chance of succeeding if there were better understanding of the deep differences between the cultures of science and education, which are manifested in their discordant approaches to reading (see also Seidenberg, forthcoming ).

It is important to note that there is plenty of good science relevant being conducted within schools of education, often in departments such as Educational Psychology; however, it is isolated from programs focused on professional training and the development of curricula and instructional practices. My comments on the culture of education focus on the training-and-practices side. I should also stress that my concerns are not about teachers, but rather about what teachers are taught (about child development in general and reading in particular) and about how curricula and instructional practices are created and evaluated. I am not challenging anyone's integrity, commitment, motivation, effort, sincerity, or intelligence. But I am challenging some deeply-held beliefs that have guided educational policies and practices for many years. I would expect this to be discomfiting for many people, but also recognizable as relevant to their deep commitments to helping students learn.

Finally, I must acknowledge that my treatment of these issues is incomplete, given this article's length limitations. Below I mainly characterize the current situation rather than how it arose. The resistance to the reading science of the recent past also needs to be considered in a historical context, which includes earlier attempts to base educational practices on the science of the moment. It also needs to be considered in light of other challenges to educators' traditional control over educational policies and practices (including federal intervention via legislation such as No Child Left Behind, and powerful new educational philanthropies; Ravitch, 2011 ). I provide this broader context in Seidenberg (forthcoming) .

The Two Cultures of Science and Education

Learning to read is an educational issue, historically the purview of educators, specifically schools of education. The history of education in the US has been extensively documented, mainly from the perspective of educators themselves (e.g., Ravitch, 2000 ; Cremin, 1988 ). Popping up a level, one sees that science and education occupy different territory in the intellectual world (literally so on many university campuses). The result is that people who are studying the same thing—how children learn to read, for example—can nonetheless have little contact. The cultures of education and science are radically different: they have different goals and values, ways of training new practitioners, criteria for evaluating progress. The two cultures also communicate their research at separate conferences sponsored by parallel professional organizations attended by different audiences, and publish their work in different journals. There are publishers that target one audience and not the other. These cross-cultural differences, like many others, are difficult to bridge.

Psychologists have been studying reading since the 19 th century and educators have had an approach-avoidance conflict about it ever since. Education as a discipline embraced a few theorists with roots in modern psychology—Dewey, Vygotsky, Piaget, and Bruner among others—whose work underlies the deeply entrenched “constructivist” approach in education ( Tobias & Duffy, 2009 ). There is deep skepticism about the relevance of empirical studies that utilize the tools of modern experimental cognitive and developmental psychology, whether in laboratories or classroom settings (e.g., Coles, 2000 ); however, it co-exists with a readiness to appropriate findings that are consistent with existing beliefs and practices. The special role of science—to find out, to the best of our ability, what is true, letting the implications fall where they may—is subverted if people selectively attend to the findings they find congenial: it transforms research studies into another form of anecdote. Educators also use our research as a source of novel findings that feed the relentless demand for educational innovation. Often this means getting far too carried away far too rapidly with findings that are interesting and new but also not solidly established or understood.

These conflicting attitudes about science and education are at the heart of controversies about reading instruction. What I'll call the Modern Synthesis about learning to read, reading skill, and the relationship between reading and language emerged from work conducted since the 1970s, beginning with Gibson and Levin (1978) , Liberman et al. (1977) , Gough (e.g., Gough & Hillinger, 1980 ; Hoover & Gough, 1990 ), Stanovich (1980) , and others. Almost all of this research was conducted by scientists working outside traditional departments and schools of education. The empirical findings underlying the Modern Synthesis were summarized in several white papers commissioned by various agencies ( Adams, 1990 ; Snow et al., 1998 ; National Reading Panel, 2000 ; Snow, 2002 ; Lonigan & Shanahan, 2009 ). This research called into question basic assumptions underlying how reading is taught and what teachers are taught about reading and development—most importantly the idea that the way that children acquire a first, spoken language provides a good model for learning to read—and yet it has had little subsequent impact on them. The conflicts between scientific and educational approaches to reading continue, centered on three issues.

1. Deciding what is true

One of the major cross-cultural differences concerns attitudes about evidence. There is a movement to encourage evidence-based practices in education, analogous to the ones in medicine and clinical psychology (see http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc ). The effort founders, however, if the stakeholders do not agree on what counts as evidence, or who should decide. Many educators are dismissive of attempts to examine reading from a scientific perspective, which is seen as sterile and reductive, intrinsically incapable of capturing the ineffable character of the learning moment, or the chemistry of a successful classroom ( Coles, 2000 ). Education as a discipline has placed much higher value on observation and hard-earned classroom experience. This division was apparent in reactions to the NRP report (2000) . The panel reviewed the scientific literature relevant to learning to read, having established explicit a priori criteria for what kinds of studies would be considered. Those criteria excluded studies that educators value: mainly, observational, quasi-ethnographic studies of individual schools, teachers, classrooms, and children that do not attempt to conform to basic principles of experimental design or data analysis (see, e.g., Barton & Hamilton, 1998; Rasinski et al., 2011 ). The report was therefore of little interest, to many educators except as evidence for a scientistic bias at odds with the educational establishment's core values ( Krashen, 2001 ). 6

From the perspective of modern studies of cognition, educators' confidence in the reliability of their own observations and experiences in classroom settings is baffling. If teachers really could figure out how reading works and children learn just by observation and experience, there wouldn't be a literacy problem or debates about best practices. But what we can learn about reading this way is limited. Most of what we do when we read is subconscious: we are aware of the result—whether we understood a text or not, whether we found the information we were seeking. Neither teachers nor scientists can directly observe children's mental and neural processes; what can be intuited about them based on classroom experience is limited, and intuitions often conflict. Introspection and systematic personal observation were the main methodologies used by the founders of modern psychology ( Boring, 1953 ), but discovery of their limitations led to the adoption of less observer-dependent methods. The limitations are even greater than the early psychologists could have known. What people observe depends on what they believe (see Cox et al., 2004 , for a striking illustration). Inferences based on observation are subject to deep-seated biases that required Nobel-prize caliber research to uncover ( Kahneman, 2011 ). The limitations of personal observation and experience are among the reasons why we conduct this other, scientific, kind of research: to understand components of reading that would otherwise be hidden from view and to do it in an objective, independently verifiable way. A folk psychology about how we read based on intuition and observation does not become any more reliable when elevated to educational principle, but that is the modern history of educational theorizing about reading.

2. The socio-cultural approach

The Modern Synthesis developed out of research that examined reading within the broader context of research on human language and cognition and their neural and computational bases. Within education, a much more influential approach has emphasized the socio-cultural aspects of literacy, particularly the status of reading in different cultural, linguistic, and socio-economic subgroups (e.g., Gee, 1997 ; Au, 1998 ; Scribner & Cole, 1981 ; Moje & Luke, 2009 ). The approach emphasizes attitudes toward reading within such groups; the varied purposes for which people read in different contexts defined by situation, culture, language, or SES; the relevance of different reading-related activities to learners in these contexts; and how socio-cultural factors affect a child's motivation to learn to read and which classroom practices will be successful.

Much of what is assumed within the socio-cultural approach seems true enough, at an informal level: reading isn't a unitary task; how we read depends on what we are reading and for what purpose; in developing a curriculum it would be wise to take into account the cultural and socio-economic context, including different attitudes toward reading and differences in experiences and opportunities outside the classroom that can greatly affect children's progress. These factors are likely to have a strong impact on the child's motivation to read, a very significant factor that reading scientists have largely ignored.

The socio-cultural research addresses important issues; they are deeply implicated in the “achievement gaps” discussed in the next section. The problem is that socio-cultural paradigm is positioned as an alternative to studies of the types of knowledge and processing mechanisms that underlie reading and how they are acquired, rather than addressing complementary issues. The tension between these approaches furnished the subtext for the “reading wars”. The heart of the conflict was a debate about the validity of what were termed “skills” vs. “literacy” approaches, which, amazingly, were seen as competing alternatives. 7 The scientists were seen as focused on “skills” (e.g., learning to read words and sentences accurately and fluently; vocabulary development), whereas educators emphasized developing “literacy” (the child's appreciation the various types and uses of written language, by individuals with diverse backgrounds, values and cultural traditions). Classroom time is a zero-sum game and so choices between skills and literacy had to be made. Moreover, teaching basic skills to beginning readers was thought to be counterproductive because it stifles children's natural curiosity about reading and their motivation to learn. This basic skills stuff may be necessary but it is also poisonous in large doses, so the child should be exposed to as little of it as possible. The traditional goal of teaching children to read has been replaced by coaching: encouraging the appreciation of and engagement in “multiple literacies.” Educational theorizing has gone “meta” about reading: there's little about how reading works (i.e., its neurocognitive bases), and much about how reading is used (various “literacy practices”) and by whom (various cultural/ethnic/language groups).

This conflict—which I am by no means overstating—arises from a failure to assume a genuinely developmental perspective. The act of reading and comprehending text involves the coordination of cognitive, linguistic, perceptual, motoric, memory and learning capacities. Understanding these capacities, how they develop, and how they are recruited in support of reading is obviously relevant to being able to help children become successful readers. What is relevant to teach (or “facilitate”) depends on where the child is on an extended developmental trajectory. The ability to read and comprehend words and their components is a basic, foundational skill. Helping children achieve this skill, without creating disinterest in reading, is the educational challenge. Acquisition of this foundation allows the child to benefit from other activities that promote further advancement: extended practice reading a variety of texts, with close checks on comprehension; reading texts for different purposes; gaining background knowledge relevant to what is being read. Socio-economic and cultural factors are highly relevant to the child's ability to benefit from schooling, but they do not change the nature of the reading process, or the kinds of knowledge and skills that need to be acquired.

3. Scientific literacy

The gap between the cultures ensures that people coming from the education side have little opportunity to gain an understanding of how research is conducted in relevant disciplines such as cognition, development, and neuroscience. Schools of education socialize prospective teachers into an ideology about children, learning, and reading. Prospective teachers are not exposed to other research that is relevant to their jobs, which is especially damaging given how difficult those jobs are. Educators are unprepared to engage this science in a serious way because they lack the tools to understand what is studied, how it is studied, what is found, what it means, and its relation to other kinds of research. This also leaves educators vulnerable to claims that are intuitively appealing but unproved, overhyped, or discredited. Educators embrace the importance of “critical thinking skills” and “background knowledge” in reading and learning, and so it is ironic when they are missing from discussions of research on reading and learning. I think that this deep ambivalence about the relevance of science to the educational mission explains seemingly contradictory features of educational culture such as the cherry-picking of selected findings, while at the same time discounting the relevance of basic research (e.g., Duke & Martin, 2011 ). I think it also explains why the single most influential educational theorist in America is Lev Vygotsky, who lived in the Soviet Union, wrote in Russian, died in 1934, and never saw an American classroom, or a television, computer, calculator, videogame or smartphone, yet educators are also looking to the latest findings from neuroscience for help (e.g., Willis, 2007 ). It is hard to know what Vygotsky, who founded the socio-cultural framework for education as an alternative to approaches based on psychology and biology, would have thought of this latest development.

Does It Matter?

The people who teach teachers and create curricula don't pay much attention to the science of reading, but is there reason to think that closer alignment of science and education would result in better outcomes? There have always been competing views about how reading should be taught, or, indeed, if it needs to be taught at all. People who have had vastly different educational experiences manage to become skilled readers. We know that teacher quality has a huge impact on educational outcomes (e.g., Hanushek & Rivkin, 2006 ) , but what about different ways of teaching reading?

It should matter. Reading is a learned skill, an “unnatural act” in Gough's memorable phrase. Some children find it easy to learn to read regardless of what happens in the classroom; many are well on their way by the onset of formal schooling. Other children will have difficulty learning to read regardless of what happens in the classroom because they are dyslexic: they have a developmental disorder that interferes with learning to read. Few teacher education programs provide any serious training related to developmental disorders such as dyslexia, how children at risk can be identified, and how such children can be helped. Whereas researchers are closing in on the neural and genetic bases of dyslexia ( Gabrieli, 2009 ), educational theorists are still debating whether dyslexia exists, and if it does, whether knowing that a child has the disorder should have any impact on classroom practices ( Elliott & Gibbs, 2008 ). Many of those children and adults who score poorly on national assessments are undoubtedly dyslexics whose condition has not been identified or addressed.

Between these extremes there is the great majority of children for whom how reading is taught matters a great deal. They are why we should care about what teachers are taught about reading. The main problem is that many of the basic assumptions about how children learn to read that have guided teacher education, classroom practices, and curriculum development have been contradicted by the basic research that lead to the Modern Synthesis. Beliefs about reading, learning, and development, reinforced over many years within the insular culture of schools of education, do not coincide with facts about reading, learning, and development uncovered using a variety of methods in laboratory and naturalistic settings. Rather than repeat details reviewed in sources I've already mentioned, let me try to capture the essence of the problem.

Everyone agrees that children have to acquire basic skills related to processing the visual code (letter recognition, learning about orthographic structure and the relationships between orthography and phonology, etc.), which provide a foundation for developing the ability to comprehend different kinds of texts for different purposes. Beyond this basic observation, there are two contradictory views.

Educators have assumed that basic skills are relatively easy to acquire, but comprehension is hard. Acquiring basic skills is mostly a matter of providing a literacy-rich environment with activities that engage and motivate the child. Learning to read was assumed to be like learning a spoken language. Children do not need to be explicitly instructed in how to read any more than they needed instruction in how to speak a first language. In practice—a Whole Language K-3 classroom—this meant de-emphasizing instruction related to acquiring basic skills. In the appropriate environment, full of “authentic” literature (rather than books written for the purpose of teaching reading), literacy activities focused on extended, “multisensory” engagement with a book (e.g., reading a book to the child, small groups of children reading the book aloud together, making a personal copy of the book, drawing pictures of the book, coloring the book, “writing” about the book using invented spelling, talking about the book, etc.), the child would discover the mechanics. Following John Dewey, discovering how reading works is assumed to have more value than being taught to read. The teacher's role is to promote literacy, not teach reading.

Comprehension, in contrast, was thought to be hard. The great fear was that children might develop basic skills and yet fail to comprehend texts. (Indeed it was thought that an initial focus on phonics would make it harder to become a good comprehender.) And so, inspired by theorists such as Frank Smith (1971 , now in its sixth edition), curricula focused on developing the child's explicit knowledge about text structure, types of inferences, the varied relationships between author and reader, the varied goals of reading, how to monitor comprehension and repair errors, and so on.