UTC Scholar

- UTC Scholar Home

- UTC Library

Preserving and Sharing UTC's Knowledge

- < Previous

Home > Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications > Masters Theses and Doctoral Dissertations > 512

Masters Theses and Doctoral Dissertations

The role of resilience, emotion regulation, and perceived stress on college academic performance.

Katherine A. Pendergast , University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Follow

Committee Chair

Ozbek, Irene Nichols, 1947-

Committee Member

Clark, Amanda J.; Rogers, Katherine H.

Dept. of Psychology

College of Arts and Sciences

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Place of Publication

Chattanooga (Tenn.)

Stress is a common problem for college students. The goal of this thesis was to examine the relationships between protective and risk factors to experiencing stress and how these factors may predict academic performance in college students. 125 college students were surveyed twice over the course of a semester on emotion regulation strategies, trait resilience, and perceived stress. The relationships between these variables and semester GPA were analyzed using correlational, multiple regression, and hierarchical regression analyses. It was determined that trait resilience scores do predict use of emotion regulation strategies but change in stress and trait resilience do not significantly predict variation in academic performance during the semester. Limitations and future directions are further discussed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my advisor, Dr. Ozbek, and committee members, Dr. Clark and Dr. Rogers, for invaluable feedback and support. Additional thanks to Dr. Jonathan Davidson, M.D., for his permission to use the CD-RISC to better understand resilience in the college population. Also, I would like to extend thanks to Linda Orth, Sandy Zitkus, and the entire records office staff of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga for their willingness to collaborate and assist with this project. Lastly, I would like to thank the faculty and students of the Psychology Department for their overall support.

M. S.; A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science.

Stress (Psychology); Academic achievement -- Education (Higher)

Stress; Resilience; Emotion regulation; Academic performance

Document Type

Masters theses

xi, 72 leaves

https://rightsstatements.org/page/InC/1.0/?language=en

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

Recommended Citation

Pendergast, Katherine A., "The role of resilience, emotion regulation, and perceived stress on college academic performance" (2017). Masters Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. https://scholar.utc.edu/theses/512

Since April 24, 2017

Included in

Psychology Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit Research

- Graduate School Thesis and Dissertation Guidelines

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Perceived stress and stress responses during COVID-19: The multiple mediating roles of coping style and resilience

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Psychology, Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China

Roles Investigation

Affiliation Department of Political Theory, Qingdao Branch of Naval Aeronautical University, Qingdao, China

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Psychology, Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China, Department of Medical Psychology, Changzheng Hospital, Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China

- Qi Gao,

- Huijing Xu,

- Cheng Zhang,

- Dandan Huang,

- Tao Zhang,

- Taosheng Liu

- Published: December 15, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071

- Reader Comments

Although many studies have examined the effects of perceived stress on some specific stress responses during the COVID-19, a comprehensive study is still lacking. And the co-mediating role of coping style and resilience as important mediators of stress processes is also unclear. This study aimed to explore the effects of perceived stress on emotional, physical, and behavioral stress responses and the mediating roles of coping style and resilience in Chinese population during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19 from a comprehensive perspective. 1087 participants were recruited to complete the anonymous online survey including the Perceived Stress Scale, the Stress Response Questionnaire, the Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire and the Emotional Resilience Questionnaire. Pearson’s correlation and Hayes PROCESS macro 3.5 model 6 were used in the mediating effect analysis. Results showed that positive coping style and resilience both buffered the negative effects of perceived stress on emotional, physical, and behavioral responses through direct or indirect pathways, and resilience had the strongest mediating effects. The findings urged relevant authorities and individuals to take measures to promote positive coping style and resilience to combat the ongoing pandemic stress and protect public physical and mental health.

Citation: Gao Q, Xu H, Zhang C, Huang D, Zhang T, Liu T (2022) Perceived stress and stress responses during COVID-19: The multiple mediating roles of coping style and resilience. PLoS ONE 17(12): e0279071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071

Editor: Carmen Concerto, University of Catania Libraries and Documentation Centre: Universita degli Studi di Catania, ITALY

Received: September 17, 2022; Accepted: November 29, 2022; Published: December 15, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Gao et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and the Supporting information files.

Funding: This study was funded by “The 14th Five-year Plan” project of big data application (145AWX200020011X); National Social Science Foundation of China (2022-SKJJ-B-041); “Pyramid Talents Project” Medical talents project of Changzheng Hospital (202007A02). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

The recurring COVID-19 pandemic now constitutes a public health emergency of international concern despite being in its third year [ 1 ]. The outbreak and persistence of COVID-19 has brought a great burden to the public through the risk of infection, social isolation, economic downturn, and other negative events that put the public under great psychological stress [ 2 – 4 ]. Such chronic stress exposure can lead to various stress responses in individuals. Many studies confirmed that perceived stress [the evaluation of one’s perceived level of stress] during the pandemic was positively relevant to individual emotional responses such as anxiety and depression [ 5 , 6 ], and physical responses such as insomnia [ 7 ], especially for those with psychic fragility [ 8 ]. According to the System-based Model of Stress proposed by Jiang [ 9 ], stress responses consist of emotional, physical and behavioral changes that people exhibit as a result of stress. However, no studies have yet explored the effects of perceived stress on different stress responses in the same group during the pandemic. Given the multidimensional nature of stress responses, a comprehensive study could provide a more systematic and holistic understanding of individual stress in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Individuals may exhibit different levels of perceived stress and stress responses even when confronted with the same stressors [ 10 ]. The Stress, Emotions, and Performance meta-model states that the stress process begins with the perception of stress, mediated by various levels of cognitive appraisal and coping resources, and then leads to positive or negative stress responses [ 11 ]. In this process, some protective or risk factors mediate the effects of perceived stress on stress responses. One of them is coping style. Coping style refers to an individual’s cognitive or behavioral pattern in the face of frustration or stressors which can moderate the stages of stress as an individual trait [ 12 ]. Yan et al. [ 13 ] investigated the effect of coping style on the relationship between perceived stress and psychological distress and found that positive coping style alleviated individuals’ emotional distress, while negative coping did the opposite. The results was consistent with most related-topic researches, with positive or adaptive coping being associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression, and negative or maladaptive coping exacerbating psychological distress of people [ 14 – 16 ]. Additionally, a review of stress-related mood disorders suggested that differences in coping styles directly leaded to differences in individual physiological responses to stressors, which in turn affected individual susceptibility to illness [ 17 ]. However, the role of coping styles in the relationship between perceived stress and physical or behavioral responses during the pandemic was still unclear.

Resilience is recognized as a pervasive individual characteristic that helps individual adapt to or overcome adversity, stress, trauma, and recover from these negative experiences [ 18 , 19 ]. Resilience has played an important role in reducing individual mental illness and protecting public well-being during COVID-19 [ 20 – 23 ]. Wilks and Croom [ 24 ] discovered that individuals with higher perceived stress may develop lower levels of resilience [ 25 ], which in turn resulted in higher psychological problems [ 26 ]. But similarly, there have been few studies on the role of resilience in mitigating the negative effects of perceived stress on physical and behavioral responses. As one of the important protective factors for stress, it is reasonable to speculate that resilience may also mitigate physical and behavioral stress responses of individuals during the pandemic.

Coping style and resilience are considered to be closely related concepts [ 27 ], which can jointly relieve individual stress responses. Campbell-Sills et al. [ 12 ] reported that coping style was significantly associated with resilience. Positive and adaptive coping style contributed to the development of resilience, while negative maladaptive coping style was an important risk factor for low levels of resilience [ 28 ]. A review from Shing et al. [ 29 ] also concluded that resilience during and after disasters may partly depend on individual coping style. Such ability to cope with stress was critical for people to recover and adapt after crises, which could be significantly strengthened by positive coping style [ 30 , 31 ]. To our knowledge, no researches have studied how coping style and resilience together function in the effects of perceived stress on stress responses.

In summary, this study aims to explore the effects of perceived stress on emotional, physical, and behavioral stress responses and the mediating roles of coping style and resilience in the Chinese population during the third year of COVID-19, in order to provide scientific suggestions for relevant organizations and individuals to take more effective measures to reduce stress responses and protect physical and mental health in the context of the ongoing pandemic. The proposed models of this study is shown in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.g001

2. Materials and methods

2.1 participants.

Convenience sampling and snowball sampling were used in this study. A total of 1087 subjects were recruited to voluntarily participate in an anonymous questionnaire through the Questionnaire Star platform ( https://www.wjx.cn/vm/YLUDsAO.aspx ) from March 2022 to April 2022. The inclusion criteria included age above 18 years old, currently in mainland China, and voluntary investigation participation. The exclusion criteria included participants’ ages of less than 18 or more than 70, participants response times of less than 200 s or more than 1800 s, repetitive answers, and confusing logic. Finally, 873 valid respondents were included in the analysis (valid ratio = 80.31%, mean age = 38.22 ± 11.95), from 89 cities in 28 provinces of China.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Naval Medical University (NMUMEREC-2021-043). The ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in the course of the study. All participants were asked to complete an informed consent notification prior to the questionnaire. Furthermore, participants were guaranteed the voluntary and confidential of their responses and their rights to quit the survey at any time.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 demographics..

Demographic variables included gender (Male, Female), age (18–35, 36–50, >50), occupations (Occupations with COVID-19 exposure risk: healthcare works, administrators whose work is directly involved with the pandemic, pandemic volunteers, etc; Occupations without COVID-19 exposure risk: enterprise worker, teachers, students, etc), quarantine or not (Being quarantined, Not being quarantined), and financial worries (Extreme worry, Serious worry, Moderate worry, Mild worry, Not at all.)

2.2.2 Perceived stress.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) was applied to measure to which degree people felt their lives as stressful in the past month [ 32 ]. The scale consists of 10 items ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The total scores are calculated by the sum of the 10 items ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores denote higher perceived stress. In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.834.

2.2.3 Stress responses.

The 28-item Stress Response Questionnaire [ 9 ] was used to assess the degree of individual’s stress responses over the last month. The scale includes three subscales: Emotional Response (ER: anxiety, depression, anger, etc. i.e.,”Feeling sullen and depressed.”), Physical Response (PR: dizziness, body pain, fatigue and lassitude, etc. i.e., “Feeling weak and tired easily.“), and Behavioral Response (BR: avoidance, reduced physical activity, etc. i.e., “Too lazy to move.“). Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (surely yes) to 5 (surely not). The total scores for each subscale are summed by the corresponding items. Only three subscales were used in the present study and the Cronbach’s α for ER, PR and BR was 0.946, 0.915 and 0.847, respectively.

2.2.4 Coping style.

The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ) was employed to measure the coping style (CS) that people were accustomed to using in their lives [ 33 ]. There are two dimensions of this scale: positive coping style with 12 items and negative coping style with 8 items. Items are rated on 4-point Likert scales from 0 (never) to 3 (always). In this study, the participants’ final coping style scores were equal to the positive coping scores minus the negative coping scores. The higher the final score, the more inclined the individual was to the positive coping style, and the less inclined the individual was to the negative coping style [ 15 ]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.876 for the current study.

2.2.5 Resilience.

The Emotional Resilience Questionnaire (ERQ) was selected to measure resilience (R). This scale was firstly designed by Zhang and Lu [ 34 ] based on Chinese local culture to assess the resilience of adolescents, the validity has also been demonstrated in adults [ 35 ]. The questionnaire includes 11 items rated from 0 (never) to 6 (always). The total scores are the sum of the 11 items with higher scores indicating greater resilience. The Cronbach’s α was 0.845 in this study.

2.3 Data analysis

All data were analyzed by SPSS21.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe demographic characteristics. Pearson’s correlation analyses were used to examine the correlation between variables of interest. Model 6 of PROCESS v 3.5 was selected to test the mediating effects of coping style and resilience [ 36 ], and the significance of indirect effects were examined by bootstrap method (5000 bootstrap samples) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Demographic characteristics were included in all mediation models as covariates. All variables were standardized before analysis. All statistical tests were two-tailed with p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

3.1 Sample characteristics

The sample characteristics are presented in Table 1 . More than two-third of the participants were female (63.80%). 48.45% of the samples were aged between 18–35, and 35.51% were 36–50. 24.74% were occupationally at the risk of COVID-19 exposure. About half of the participants were being quarantined at the time of our investigation. 6.99% of the individuals reported extremely worried about self finances and 20.39% didn’t worried at all.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.t001

3.2 Correlation analysis

Table 2 shows the results of Person correlation analysis between variables. Perceives stress, emotional response, physical response, and behavioral response were positively inter-correlated with each other, and were all negatively associated with coping style and resilience (all p < 0.01). Coping style was positively related to resilience ( p < 0.01).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.t002

3.3 Multiple mediation analysis

The results of the multiple mediation analysis are shown in Table 3 and Fig 2 . After controlling for gender, age, occupations, quarantine or not, and financial worries, PSS showed negative direct effects on CS ( β = -0.49, p < 0.001) and R ( β = -0.43, p < 0.001), as well as positive direct effects on ER ( β = 0.60, p < 0.001), PR ( β = 0.59, p < 0.001), and BR ( β = 0.47, p < 0.001). CS was positively related to R ( β = 0.29, p < 0.001) and negatively related to BR ( β = -0.09, p < 0.001). R was negatively associated with ER ( β = -0.16, p < 0.001), PR ( β = -0.18, p < 0.001), and BR ( β = -0.15, p < 0.001). Other direct paths were not significant.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.t003

The bootstrap method mediating analysis ( Table 4 ) showed that the indirect effects of PSS on ER through R ( Effect = 0.07, SE = 0.01, 95%CI [0.04, 0.10]) and chain path of CS and R ( Effect = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95%CI [0.01, 0.03]) were significant. The indirect effects of PSS on PR via R ( Effect = 0.08, SE = 0.02, 95%CI [0.05, 0.11]) and chain path of CS and R ( Effect = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95%CI [0.01, 0.04]) were significant. The indirect effects of PSS on BR through CS ( Effect = 0.04, SE = 0.02, 95%CI [0.01, 0.08]), R ( Effect = 0.07, SE = 0.02, 95%CI [0.03, 0.10]) and chain path of CS and R ( Effect = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95%CI [0.01, 0.03]) were significant. Other indirect paths were not significant.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.t004

4. Discussion

COVID-19 posed a widespread and extensive threat to the public as a worldwide health emergency. The persistence of such a negative stressor would trigger a range of psychological, physiological and behavioral changes of people [ 37 ]. This study provided a comprehensive perspective about the effects of perceived stress on emotional, physical, and behavioral stress responses, as well as the separate mediating and co-mediating effects of coping style and resilience. As expected, perceived stress was positively associated with emotional, physical, and behavioral responses. People with higher perceived stress reported more negative emotions, more severe physical symptoms, and more maladaptive behaviors, which was in line with most of the previous studies [ 38 – 41 ].

In the present study, coping style alone mediated the association between perceived stress and behavioral responses, and positive coping could buffer the negative effects of perceived stress on behavioral responses. However, coping style did not mediate the effects of perceived stress on emotional or physical responses, which was inconsistent with previous studies. A majority of studies regarded coping style as an important stress mediator between stressors and all kinds of stress responses [ 42 , 43 ]. People who prefer positive coping style tend to face problems directly and take ways to solve it positively, while people with negative coping style are inclined to avoid problems by denying and withdrawing, which in turn leads to worsening of emotional responses such as anxiety and depression, and an increase in physical responses such as lowered immunity [ 13 , 17 , 44 ]. Here are three possible explanations for the inconsistency. One is that the method of calculating coping style in our study may weaken the effects of different coping styles, since positive and negative coping styles have opposite effects. Another is that coping styles themselves are behavioral expressions and thus have stronger influence on behavioral response. The third explanation is that the role of coping style in the effects of perceived stress on emotional and physical responses are complicated. An mediation research conducted in older people reported that neither positive nor negative coping was correlated with anxiety response [ 45 ]. Lau et al. [ 14 ] also discovered that coping style did not have a direct effect on anxiety, but negative coping style showed a positive and significant effect on anxiety after positive coping style was added as a moderating variable to the structural equation. Therefore, the function of coping style in stress process still needs further research.

The results demonstrated the mediating role of resilience in the relationship between perceived stress and stress responses. Consistent with previous research, higher perceived stress was associated with lower levels of resilience, as the ongoing stress from the epidemic increased the burden on people’s coping resources [ 46 ]. And higher resilience was associated with less stress responses [ 26 , 47 , 48 ]. More importantly, our study confirms the role of resilience in buffering physical and behavioral responses in addition to emotional responses. As an effective protective factor, the higher the level of individual resilience, the better the individual’s ability to counteract perceived stress and the less emotional, physical, and behavioral stress responses are exhibited. According to the Stress Inoculation theory, moderate stress exposure contributes to resilience development. Some longitudinal studies also found that the psychological problems of individuals increased sharply in the early stages of the pandemic, then decreased rapidly, which was interpreted as the stimulation and validation of resilience [ 49 , 50 ]. However, longer term longitudinal studies are needed to clarify whether individual coping resources and resilience will be depleted as the pandemic continues. In any case, at least in the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience still plays an important role in mitigating various stress responses of people.

Coping style and resilience showed chain mediating effects between perceived stress and emotional, physical, behavioral responses in the current study. Many studies endorsed that people with fewer psychological problems in the pandemic had more successful coping and higher levels of resilience [ 51 , 52 ]. As a resilience protective factor, positive coping style was proved to contribute to resilience [ 12 , 28 , 30 ]. Except for behavioral response, coping style in this study cannot directly affect the individual’s emotional and physical responses, but need to be through resilience, and the more positive the coping tendency, the higher the resilience and the less the individual’s emotional, physical, and behavioral responses. As for the mediating effect size, the mediating effect of resilience was the strongest among all indirect pathways, suggesting that resilience performed a stronger role in buffering the effects of perceived stress on stress responses. In contrast, the simple mediation of coping style and chain mediation effects of coping style and resilience were weaker. Nevertheless, our study establishes the important roles and pathways of coping style and resilience in the relationship between perceived stress and different stress responses. The results suggest that fostering positive coping style and promoting resilience are necessary for individuals to better adapt to pandemic-related stressors, reduce stress responses, and recover quickly from pandemic trauma. Individuals are encouraged to proactively develop available protective measures, such as learning stress management methods [ 36 ], doing physical exercise or maintaining healthy lifestyle [ 53 ], and cultivating meaningful relationships for social support [ 54 , 55 ]. Governments and mental health organizations already have some useful measures, such as encouraging social connections [ 56 ], organizing psychological support groups, and providing services for mindfulness practice [ 57 ]. Some coping-focused efforts like coping skills training courses and online virtual stress adaptation training may also be helpful as our results have verified the positive effect of coping style on resilience [ 58 , 59 ].

5. Limitation

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Firstly, the convenience and snowball sampling used in the study may affect the generalization of the results and the representativeness of the sample, even though our sample was distributed across the majority of Chinese provinces. And as a cross-sectional study, no causal conclusions can be inferred. Secondly, several demographic variables (such as gender, age, and economy) were selected as covariates to increase the reliability of the results, but the factors influencing the dependent variables are actually numerous and complex. Except for demographic influences, social or political factors may also affect the perceived stress and stress responses of people. Thirdly, this study focused only on the mediating role of coping style and did not explore the effects of specific coping strategies. Studies have shown that positive or negative coping strategies did not necessarily alleviate or exacerbate stress responses. For example, Panourgia et al. [ 60 ] discovered that avoidance behavior can be an effective adaptive strategy in some situations, allowing people to deal with problems more quickly. Considering the complexity of the effects of coping, the ways in which coping and specific coping strategies function deserve further study. Fourthly, the present study explored emotional, physical, and behavioral stress responses in general but not in depth, and future studies could examine each stress response type in more detail. Last but not least, this study included the variable of “quanantine or not” as a covariate, but some studies showed that quarantined people experienced higher levels of stress [ 61 , 62 ], which means that some quarantined participants in this study may have reported higher levels of perceived stress and stress responses, so the findings may be biased and should be interpreted with caution. Further studies could continue to explore perceived stress and stress response of individuals in different quarantine states, as well as the influencing factors.

6. Conclusions

This study is the first to examine overall the effects of perceived stress on emotional, physical, and behavioral responses and the mediating roles of coping style and resilience during the recurrent outbreak of the COVID-19. The results indicated that more positive coping style and especially higher levels of resilience buffered the negative effects of perceived stress on different stress responses, suggesting that relevant authorities and individuals should take measures to foster positive coping and promote the development of resilience to against the ongoing pandemic stress and to protect individuals’ physical and mental health.

Supporting information

S1 dataset..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279071.s001

- 1. World Health Organization. Statement on the twelfth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. (2022) https://www.who.int/news/item/12-07-2022-statement-on-the-twelfth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic . (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 9. Jiang Q. Medical Psychology Theories,Methods and Clinic. 2st ed. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2012.

- 35. Zhang, Y. Attentional bias and autonomic response of emotional resilience in college students. M.Ed. Thesis, Tianjin Normal University. 2013. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201402&filename=1014117971.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=oY81E8UTFUfo7ksR3xl5usKuvM8Y8lzRKmUVqrHrJp0kKFBLqOWLsALX7wV_Zzj0

- 36. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. NY:Guilford Press; 2013.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Heterogeneous trajectories of perceived stress and their associations with active leisure: a longitudinal study during the first year of covid-19.

- 1 School of Natural Sciences and Health, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

- 2 School of Educational Sciences, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

- 3 Department of Teacher Education, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Introduction: There is a plethora of literature on the dynamics of mental health indicators throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, yet research is scarce on the potential heterogeneity in the development of perceived stress. Furthermore, there is a paucity of longitudinal research on whether active leisure engagement, which typically is beneficial in reducing stress, might have similar benefits during times of major disruption. Here we aimed to extend previous work by exploring the dynamics of change in stress and coping, and the associations with active leisure engagement over the first year of COVID-19.

Methods: Data from 439 adults ( M age = 45, SD = 13) in Estonia who participated in a longitudinal online study were analyzed. The participants were assessed at three timepoints: April–May 2020; November–December 2020; and April–May 2021.

Results: Mean stress and coping levels were stable over time. However, latent profile analysis identified four distinct trajectories of change in stress and coping, involving resilient, stressed, recovering, and deteriorating trends. Participants belonging to the positively developing stress trajectories reported higher active leisure engagement than those belonging to the negatively developing stress trajectories.

Discussion: These findings highlight the importance of adopting person-centered approaches to understand the diverse experiences of stress, as well as suggest the promotion of active leisure as a potentially beneficial coping resource, in future crises.

1 Introduction

It is accepted that COVID-19 and the circumstances surrounding the pandemic exacerbated mental health around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic spread in many waves, and this was accompanied by varying levels of social and economic restrictions and the accumulation of potentially stressful life circumstances ( 1 ). The pandemic outbreak constitutes an acute, large-scale, and uncontrollable stressor with a long-term impact. The detrimental impact of the pandemic on mental health has primarily been documented through the population-level increase in depression and anxiety symptoms ( 2 , 3 ). The origin and the development of such mental health problems are consistently related to excessive stress [(e.g., 4 )], and these associations are aligned with the stress-vulnerability models of psychopathology ( 5 , 6 ). These models explain the possible ways in which stressful experiences may trigger the onset of a mental health disorder, whether an individual is predisposed (i.e., vulnerable) to a mental health condition, and what role protective factors may play in these interactions. Numerous research evidence have linked high perceived stress not only to emotional disturbances such as anxiety ( 7 ) but also to physical health [e.g., hypertension, cardiovascular diseases ( 8 )]. Identification of sub-populations with high risk of stress and interventions to reduce stress levels can potentially help to prevent later mental disorders ( 9 ).

The transactional stress model ( 10 , 11 ) posits that a person’s capacity to cope and adjust to life challenges is a consequence of interactions that occur between a person and their environment. The ability to cope with stress depends on how an individual evaluates the relevance of the stressors (primary appraisal) and whether a person believes to hold sufficient resources to relieve or remove the stressor (secondary appraisal). In line with the transactional stress model, Cohen et al. ( 12 ) argue that a psychological state of perceived stress (hereafter stress) occurs when a situation in a person’s life is appraised as threatening or demanding and at the same time resources are insufficient to cope with the situation. However, this approach does not assume that certain life situations are inherently stressful but refers to the cognitive appraisal process where the cognitively mediated emotional response is given to the situation [(e.g., 13 )].

Several longitudinal studies among different age groups have investigated how stress levels may have changed during the pandemic. Most of these studies demonstrated a stable course of stress levels irrespective of the pandemic situation ( 14 – 16 ). Such findings have been explained considering the significant social and economic challenges (e.g., financial insecurities, changes in the working modalities, disruptions in the social life) that the pandemic brought in addition to the health crisis, and which together prolonged the risk of chronic stress. Salfi et al. ( 17 ) reported that stress levels even increased after the first lockdown period in the spring of 2020 and further plateaued by the second wave of the pandemic. They suggested that, in addition to a continuous societal and economic crisis, the lifting of restrictions in between the waves raised the perception of risk and thereby affected stress levels. Controversially, Gallagher et al. ( 18 ) demonstrated decreasing stress levels as the course of the pandemic continued and ascribed such findings to the presupposition that individuals become more resilient to the repercussions of the pandemic over time [(see 19 )].

Most of the previous longitudinal studies on the development of stress among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic have focused on the average changes (i.e., variable-centered approach), but the distinct courses of the stress over time (e.g., increasing for some, while decreasing for others) may bias the results and can obscure heterogeneous patterns (i.e., person-centered approach) of experiences. There is no reason to doubt that all the scenarios explained by the above-cited studies may have partly affected stress response throughout the pandemic but depended on many contextual and person-centered factors. A meta-analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on mental health indicators showed substantial heterogeneity among the findings of longitudinal studies ( 20 ), which suggests that there were no ubiquitous effects on mental health. Several longitudinal studies ( 21 – 23 ) have scrutinized the possibility of distinct courses of the change in symptoms of mental disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety). These studies found heterogeneous trajectories of symptoms during the pandemic, showing that approximately 70–80% of the population consistently reported no symptoms of mental disorders. They concluded that for smaller groups in the population symptoms of mental disorders increased, or in contrast decreased, as the pandemic continued its course. These findings add to evidence that lockdowns did not have evenly detrimental effects on mental health and that a certain proportion of people were psychologically resilient to the circumstances, or some might have even benefitted from the new work and life patterns.

A few studies have also employed a person-centered approach to examining perceived stress and stressor exposure based on cross-sectional data from the beginning of COVID-19. These studies have identified distinct profiles of pandemic-related exposure to stressors in adults ( 24 ) and heterogeneous profiles of stress and coping levels among pregnant women ( 25 ). However, such cross-sectional studies do not allow the examination of potentially distinct trajectory groups of stress developments over time. To our knowledge, the only published longitudinal investigation employing a person-centered approach for the examination of changes in perceived stress levels during the pandemic has been conducted among adolescents [age 12–15 years, ( 16 )]. This study found no support for distinct trajectories of perceived stress. Adolescents (ages 12–15 years) were characterized by homogeneously stable and moderate stress levels during the first year of the pandemic. The authors explained this finding by assuming that adolescents commonly experience stress regardless of the pandemic, and thus pandemic-related stressors did not greatly affect their normative stress levels. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have scrutinized in adults the potential heterogeneity of trajectories (i.e., change over time) of perceived stress during the pandemic, and the findings of the previous variable-centered longitudinal studies on perceived stress are inconsistent ( 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 ).

An all-embracing socio-historical event such as the COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique occasion to identify different paths of adaptation or maladaptation to persistent stressors and to examine coping resources that help individuals manage the effects of such drastic circumstances. Engagement in leisure activities is one such behavioral coping resource. Exploring how leisure contributes to relieving and counteracting stress has been studied for decades. Coleman and Iso-Ahola ( 26 ) first proposed in their theory that leisure facilitates social support and generates enduring beliefs of self-determination, which buffers the negative impact of stress on mental and physical health. In addition, Iwasaki and Mannell ( 27 ) described how leisure may act also as a strategy for palliative coping (i.e., temporarily diverting from stressful events to regroup and gain perspective) and mood enhancement (i.e., reducing negative mood and enhancing positive mood). Empirical studies have shown evidence that when people under stressful circumstances are engaged in leisure activities, the stress is reduced and therefore the negative impact of the stress on health is also reduced ( 28 – 31 ). Zawadzki et al. ( 32 ) have also identified the real-time within-person processes such that when individuals reported engaging in leisure, they had lower stress compared to when not engaged in leisure activity. Iwasaki ( 33 , 34 ) has shown that leisure coping predicted positive coping outcomes even beyond the effects of general coping strategies (e.g., problem-focused coping unrelated to leisure).

Although no consensus definition of leisure engagement is imposed, prior research has mostly treated it as a behavioral concept—defined as the frequency or the amount of time in which one participates in leisure activities outside work duties, personal maintenance, and other obligations ( 35 ). The classification of leisure activities has neither been consistent in the literature. Leisure activities have been divided either as passive (also referred to as “low-demand” or “time-out” leisure) or active (also referred to as “high-demand” or “achievement” leisure) ( 36 – 38 ). Prior research has shown that engagement in active leisure activities (e.g., hobbies, physical, and nature-based activities) is more consistently linked with the benefits of stress reduction ( 30 , 39 , 40 ). Caltabiano ( 41 ) identified that outdoor activities/sports and hobbies were the most significant leisure activities to reduce stress. Such activities often involve using both physical and mental energy and often happen with other people. Iwasaki et al. ( 42 ) have emphasized that active leisure is more than just physical activities, and less physically active forms of leisure should not be undervalued in leisure coping processes. It can be assumed that active leisure activities involve ingredients (e.g., social interaction, creative expression, cognitive stimulation) to stimulate a wider range of mechanisms (e.g., psychological, biological, social) which may simultaneously play a role in alleviating stress [(see 43 )].

However, it has been shown that paradoxically people tend to reduce their participation in active leisure when they are stressed, which can be caused by an intuitive preference for passive leisure during hectic times or by a not deliberate reaction to the levels of stress ( 44 ). Thus, the relationship between active leisure and stress could be bidirectional, with stress also affecting motivation to engage in active leisure. At the same time, the options for active leisure were often restricted during the pandemic, possibly further limiting the engagement in active leisure. Previous studies have reported that the number of leisure activities people engaged in decreased ( 45 ), and engagement in physical and outdoor activities was reduced ( 46 ) during the first year of COVID-19.

Several studies have examined leisure engagement as a potential coping resource also during COVID-19. Based on the ecological momentary assessment data, it has been shown that engaging in free time was associated with lower stress levels during the pandemic ( 47 ). Existing findings also suggest that changes in leisure engagement (compared to pre-COVID) were related to poorer mental health ( 46 , 48 ) and people who felt their current leisure engagement level fell below their desired level reported lower mental well-being ( 46 ). Takiguchi et al. ( 45 ) have shown in their longitudinal study that engaging in a larger number of leisure activities during the pandemic reduced depressive symptoms through resilience. However, longitudinal research is scarce on whether active leisure engagement, which is usually beneficial for stress reduction, might have similar benefits in times of major disruptions of the pandemic. It can be assumed that heterogeneous trajectories (if they emerged as such) of perceived stress during the pandemic were characterized by distinct levels of active leisure engagement. As engagement in active leisure is linked with the benefits of stress reduction ( 30 , 39 – 41 ), it can be further assumed that higher engagement in active leisure was associated with positively developing (i.e., decreasing) stress trajectories. It can be expected that lower engagement in active leisure was related to negatively developing (i.e., increasing) stress trajectories.

The present study aims to explore the dynamics of change in stress and its associations with active leisure engagement as a stress coping resource over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study seeks to expand previous research by examining varying trajectories of change in stress (i.e., differences in the level, and the direction of change) and the interplay between the changes in stress and active leisure engagement over time. By doing this, we could gain a more differentiated understanding of the pandemic’s complex impact on stress levels and contribute to formulating guidance for stress-relieving behaviors in potential future lockdowns and pandemics.

As this study is exploratory by nature, to achieve the aim of the study, the following research questions are examined:

1. How did perceived stress change over the first year of COVID-19?

2. Can distinct trajectories be identified based on perceived stress levels over the first year of COVID-19?

3. How was active leisure engagement related to belonging to a certain stress trajectory over the first year of COVID-19?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 procedure and sample.

This study is part of a longitudinal investigation that focuses on the dynamics of mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in Estonia. Approval for conducting the research was granted by the Tallinn University ethics committee (April 15, 2020; decision no 6). Voluntary participants were recruited for the survey via online ads (with the link to the survey) in news portals (e.g., Delfi.ee), and social media channels (e.g., Facebook). The entire study was conducted online using the SurveyMonkey platform. Estonian-speaking adults aged 18 or older currently residing in Estonia were eligible to participate. No compensation was offered as an incentive to participate. After reading an information page and confirming their informed consent, participants completed the survey. The datasets across three assessments were merged based on unique anonymized identification numbers (using SPSS). The data was collected over three timepoints across the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: at Time 1 (T1 – April 20th until May 11th, 2020); at Time 2 (T2 – November 9th until December 6th, 2020); and at Time 3 (T3 – April 27th until May 23rd, 2021).

At T1, 530 participants were recruited for the longitudinal study, of whom 257 responded at T2 and 249 responded at T3. An additional 212 participants were recruited at T2 (via a similar strategy as at T1), of whom 142 responded also at T3. Two hundred participants responded to the survey at all three timepoints. To be able to analyze potential changes, those who had responded to the survey at least twice were included in the data analysis. This strategy resulted in a sample size of 448, which was predominantly composed of females (92.4%). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 81 ( M = 45.37, SD = 12.97). 98.2% of the participants reported their native language as Estonian. In terms of relationship status, 31% were single (including widowed, divorced) and 69% were in a relationship (including married, cohabitation, civil partnership). 82.1% of the participants were employed, and 17.9% were not employed (including students, and pensioners).

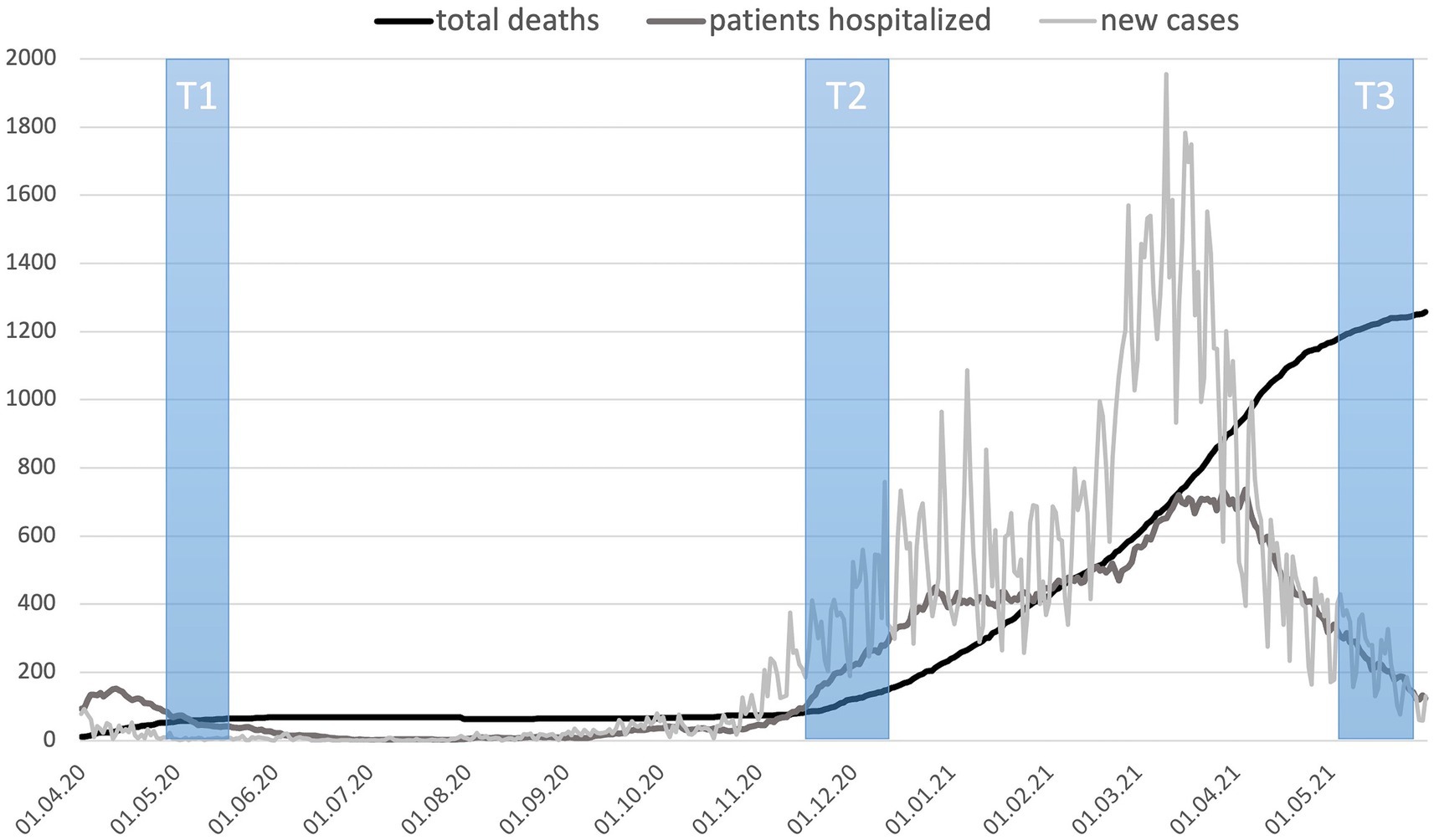

Figure 1 shows the pandemic situation in Estonia during the three data collection periods. In spring 2020, while the first measurement (T1) occurred, the State of Emergency was in effect in Estonia, which meant that the availability of medical services was decreased. Students were transferred to distance learning; public gatherings were banned. Along with restrictions in traveling, all leisure facilities were closed, excluding parks and recreational trails if following the “2 + 2 rule” (i.e., a maximum of two people together at one time, keeping a minimum distance of two meters apart from others). In autumn 2020 (T2), after a relatively virus- and restriction-free summer, the second wave of the virus arrived, and the number of new cases was rising rapidly. However, by that time, lighter restrictions (compared to T1) were only being gradually re-introduced—schools were still open and leisure facilities were so far mostly available. The third data collection, in spring 2021 (T3), followed a period in which the numbers of new cases and hospitalizations had been the highest observed throughout the pandemic, and the government had re-imposed stricter restrictions lasting until May 2021. Widespread vaccination against COVID-19 in the general population (age groups below 60 years) did not start until mid-May 2021 in Estonia ( 49 ) when our third data collection (T3) was ending.

Figure 1 . Situation during three data collection time windows (T1–T3): the number of COVID-19 deaths, patients hospitalized, and new cases per day. Source: Compiled by authors based on data provided by TEHIK ( 49 ).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 perceived stress.

Perceived stress was assessed using the Estonian version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale [PSS-10; ( 50 )]. Participants were asked to indicate on a five-point scale (0 = never, 4 = very often) how often they felt or thought a certain way during the last 4 weeks (e.g., “How often did you feel unable to control the important things in life?”). Originally, this self-reported questionnaire was designed to measure “the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful” [( 12 ), p. 385], consisting of six positively (items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 10) and four negatively (items 4, 5, 7, 8) worded items.

Although the scale was developed to capture stress as a single latent factor, following empirical studies in different contexts and languages using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) techniques have predominantly shown that a two-factor model fits the data better than a unidimensional model ( 51 – 53 ). These two related factors have been described as (a) perceived stress (or helplessness; negatively worded items) and (b) perceived coping (or self-efficacy; positively worded items). In favor of the two-factor solution, authors have pointed out that the content of positively phrased and negatively phrased items do not coincide ( 54 ); and the two factors have shown distinct predictive qualities ( 55 ). For the Estonian version of the PSS-10, only the preliminary psychometric properties have been previously reported, based on principal component analysis and internal reliability coefficients for the unidimensional solution of the scale ( 56 ). Thus, CFA was conducted for the PSS-10 to examine whether a one- or two-factor solution fits the data best. Our data supported the two-factor model of the Estonian version of the PSS-10. Hence, the current study treated perceived stress as a two-dimensional construct of stress and coping. Longitudinal measurement invariance (MI) analysis was also conducted to ensure whether comparisons of stress and coping scores across the three timepoints were meaningful ( 57 ). Our data showed configural invariance and partial scalar and metric invariance in three timepoints, as factor loadings and item intercepts were allowed to vary for two items. The detailed results of CFA and MI are provided in Supplementary material . Cronbach’s alphas showed good internal consistency for both the stress and coping items at each time point (α = 0.83–0.88). Mean values were calculated for both scales at each timepoint and used in further analyses.

2.2.2 Active leisure

Active leisure engagement was measured with a formative scale, comprising the frequency of respondents’ participation in three leisure activities: (1) engaging in physical activities (e.g., sports, walking); (2) spending time in natural settings (e.g., parks, forests); (3) participating in main hobby/pursuit . A similar aggregation approach has been used by numerous previous studies when the goal has been to capture a broader leisure activity domain with one indicator [(e.g., 36 , 46 , 58 )]. The three active leisure activities were selected based on literature: their stress-alleviating qualities have been widely described ( 30 , 39 , 40 ); and they have been consistently linked with better mental health, both before ( 59 ) and during the pandemic ( 48 ). Although our choice of leisure activity items was not all-inclusive, it tapped major active leisure engagement facets relevant to this study ( 39 – 43 ). Participants were asked to rate how often they spent time doing each of the activities during the last month. Response options were: 1 = “less than once a week or never”; 2 = “1–2 times a week”; 3 = “3–4 times a week”; 4 = “5–6 times a week”; 5 = “every day”; and 6 = “2 or more times a day.” The mean aggregation of the three activities was used, which weights each activity equally. Higher scores indicate higher active leisure engagement.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Since the final sample also included those participants who had missed one of the data collection points, the dataset had missing values of perceived stress, perceived coping, and active leisure engagement at different timepoints (31.7% of cases at T1; 10.9% at T2; 12.7% at T3). Regression imputation was used to preserve all cases and to fill in the missing values ( 60 ). For the imputation models of stress and coping, available scores of both constructs of the other two timepoints were used as predictors. In the regression imputation models for active leisure engagement, available scores of the other two timepoints of the same construct were used as predictors. Next, the stress and coping variables were scrutinized for the absence of multivariate outliers. Nine cases were eliminated as multivariate outliers, which resulted in the final sample size of 439. Further, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) controlling for covariates (age and gender) was used to examine changes in stress and coping over time. Violations of sphericity were addressed using Greenhouse–Geisser corrections.

Next, exploratory latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to identify distinct trajectories of perceived stress across the three timepoints. LPA as a person-centered technique allows the identification of heterogeneous subpopulations comprising distinct response patterns across time. Deciding the number of subgroups (i.e., trajectories) is based on the grouping precision and the comparative fit indices, as well as the interpretability of subgroups ( 61 ). Both stress and coping factors were modeled in one LPA with the variances allowed to vary between groups. Also, the covariance between stress in three timepoints and the covariance between coping in three time points were allowed to vary between groups. The fit of models with the different number of profiles was compared using the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC), the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VMLR), bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), a measure of entropy, interpretability of the observed trajectories, and the size of the profiles ( 61 ). After model selection, participants were classified according to their most likely profile membership.

Finally, a mixed ANOVA model controlling for age was run to examine the interaction between changes in active leisure engagement (time as a within-subjects factor) and trajectories of stress and coping (as a between-subjects factor). Gender was not included as a covariate due to the low number of men (<5) in some of the stress trajectory groups found with LPA. The assumption of homogeneity of variances was tested by Box’s M test. Violations of sphericity were corrected by applying a Greenhouse–Geisser correction. For post hoc multiple comparisons, Bonferroni adjustment was used.

CFA and invariance tests were performed in R version 4.1.3 ( 62 ), using lavaan package ( 63 ). Regression imputations were performed in R package mice ( 64 ). LPA was conducted using Mplus 8.8 ( 65 ). ANOVAs were performed in SPSS version 28.

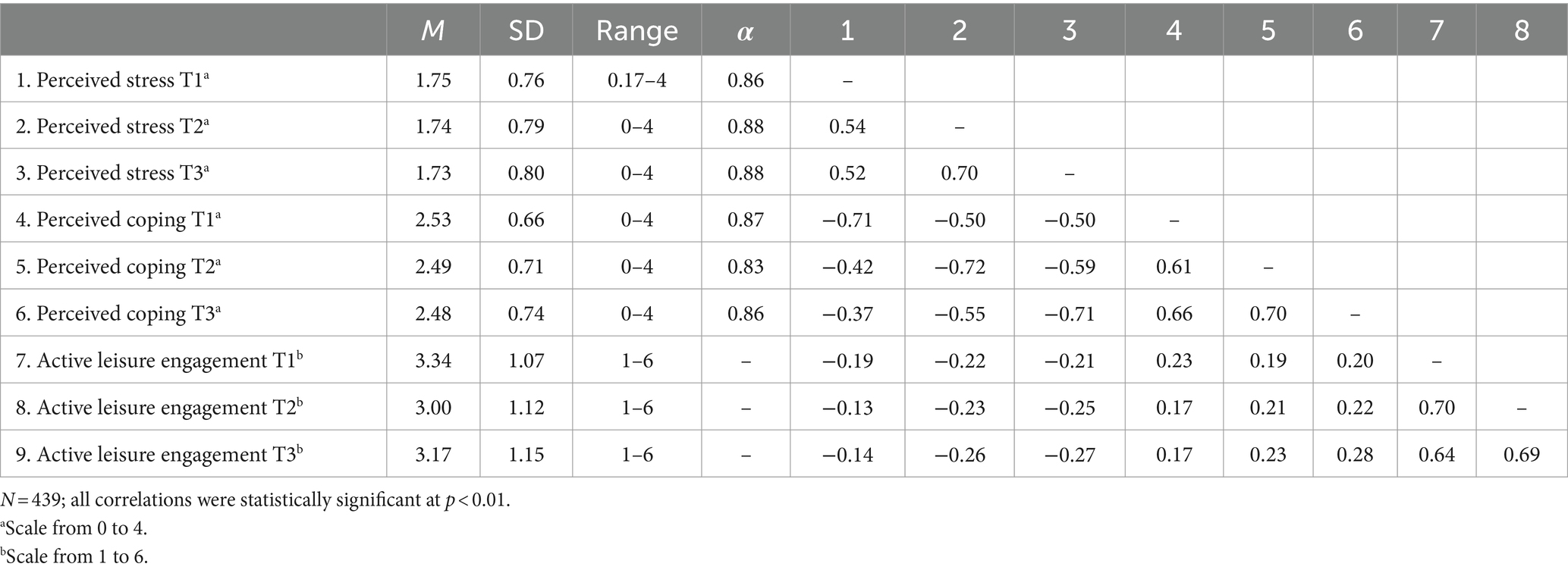

The means, standard deviations, ranges, Cronbach’s alphas, and bivariate correlations for all the study variables are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Means (M), standard deviations (SD), ranges, Cronbach’s alphas (α), and correlations between study variables.

3.1 Changes in stress and coping: variable-centered approach

First, changes in average perceived stress and perceived coping during the first year of the pandemic were investigated using repeated measures ANOVA. There were no significant changes found across three timepoints in mean scores of stress, F (1.88, 818.60) = 0.83, p = 0.43, η p 2 = 0.002, nor in mean scores of coping, F (2, 872) = 0.84, p = 0.43, η p 2 = 0.002.

3.2 Distinct trajectories of stress and coping: person-centered approach

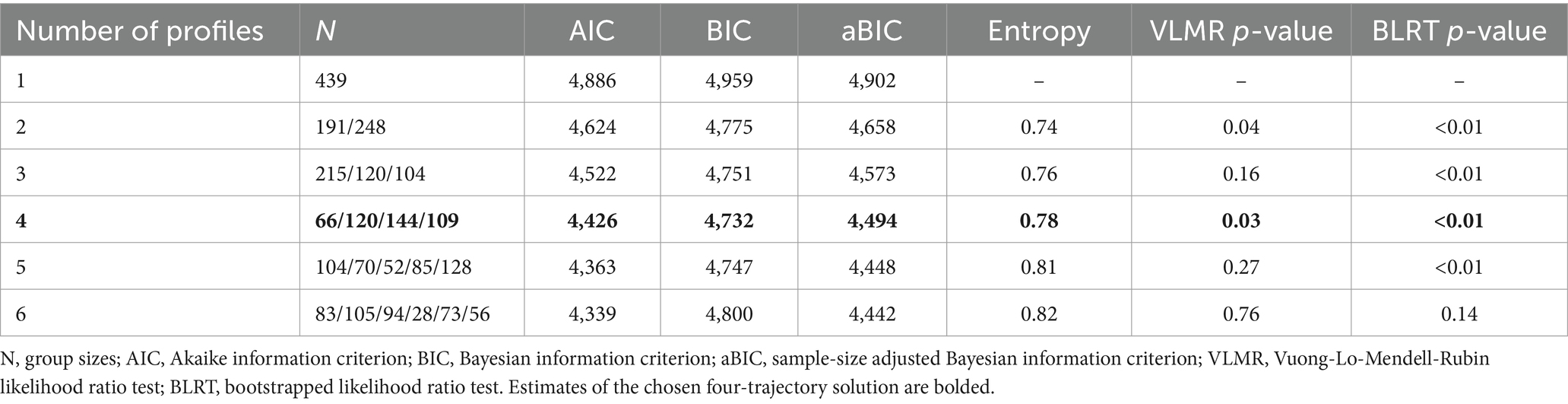

To identify potential distinct trajectories of stress during the first year of the pandemic, a latent profile analysis was conducted on perceived stress and coping scores measured at three timepoints. Six sets of LPA-s were compared. The drop of AIC and aBIC values decelerated, and BIC value did not further decrease, after the four-trajectory solution (see Table 2 for the fit indices, entropy, and group sizes). The five-trajectory solution did not reveal any new patterns of change, and the more parsimonious four-trajectory model was chosen as it had the best interpretability.

Table 2 . Fit statistics for comparison of different longitudinal latent profile models of perceived stress and coping.

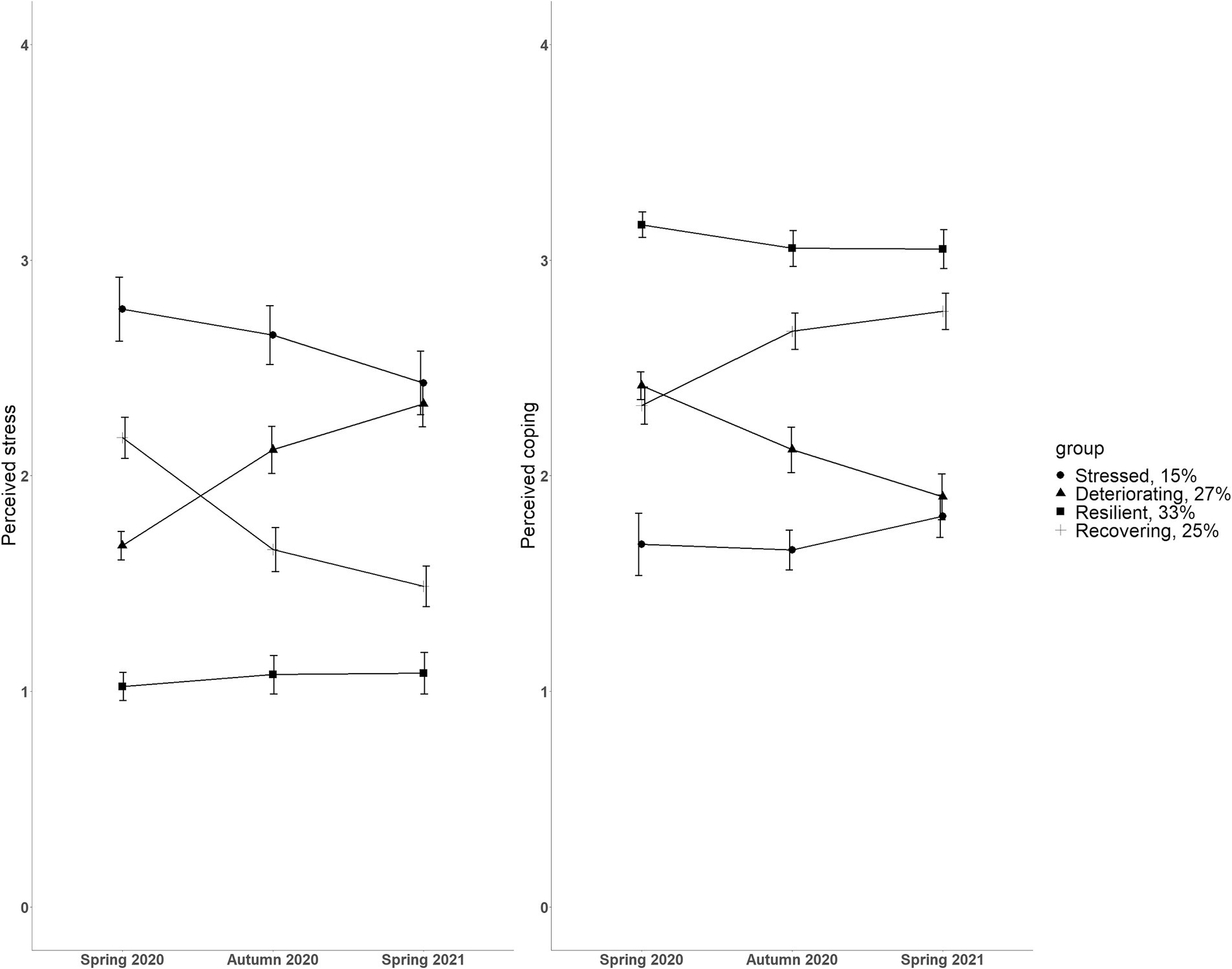

Figure 2 presents the stress and coping trajectories over three timepoints for four groups identified in the LPA model. The first trajectory, labeled as ‘ Stressed ’ (15%, N = 66), was characterized by a high stress level and a low coping level throughout the study. In the second trajectory, labeled as “ Deteriorating ” (27%, N = 120), the participants had relatively low stress and high coping at the beginning of the pandemic, but it was followed by a sustained incline in stress and decline in coping throughout the first year of the pandemic. The largest proportion of participants (33%, N = 144) belonged to the third trajectory labeled as “ Resilient .” The participants in this group had consistently low stress and high coping across the first year of the pandemic. In the fourth trajectory, labeled as “ Recovering ” (25%, N = 109), the participants reported relatively high levels of stress at the beginning of the pandemic. However, these participants “bounced back” over time, as indicated by a decline in stress and an incline in coping throughout the next two timepoints.

Figure 2 . Estimated mean perceived stress (left) and perceived coping (right) scores from the four-trajectory solution of the latent profile analysis across three timepoints. Each group indicates a distinct trajectory during the first year of the pandemic. Both scales from 0 to 4. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Next, we tested if the four groups identified in the LPA were characterized by differences in age, relationship status, or work status. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the mean age between four stress and coping groups. There was no statistically significant difference in age between the four groups [ F (3, 435) = 2.36, p = 0.07]. Chi-square tests were used to examine if the group membership was related to relationship status or work status. Relationship status was dichotomized into “single” (incl. Widowed, divorced) and “in a relationship” (incl. Married, cohabitation, civil partnership). Work status was dichotomized into “employed” and “not employed” (incl. Student, pensioner). Group membership was neither related to relationship status [ X 2 (3, N = 439) = 1.39, p = 0.71] nor to work status [ X 2 (3, 439) = 3.57, p = 0.31].

3.3 Changes in active leisure engagement in relation to distinct trajectories of stress and coping

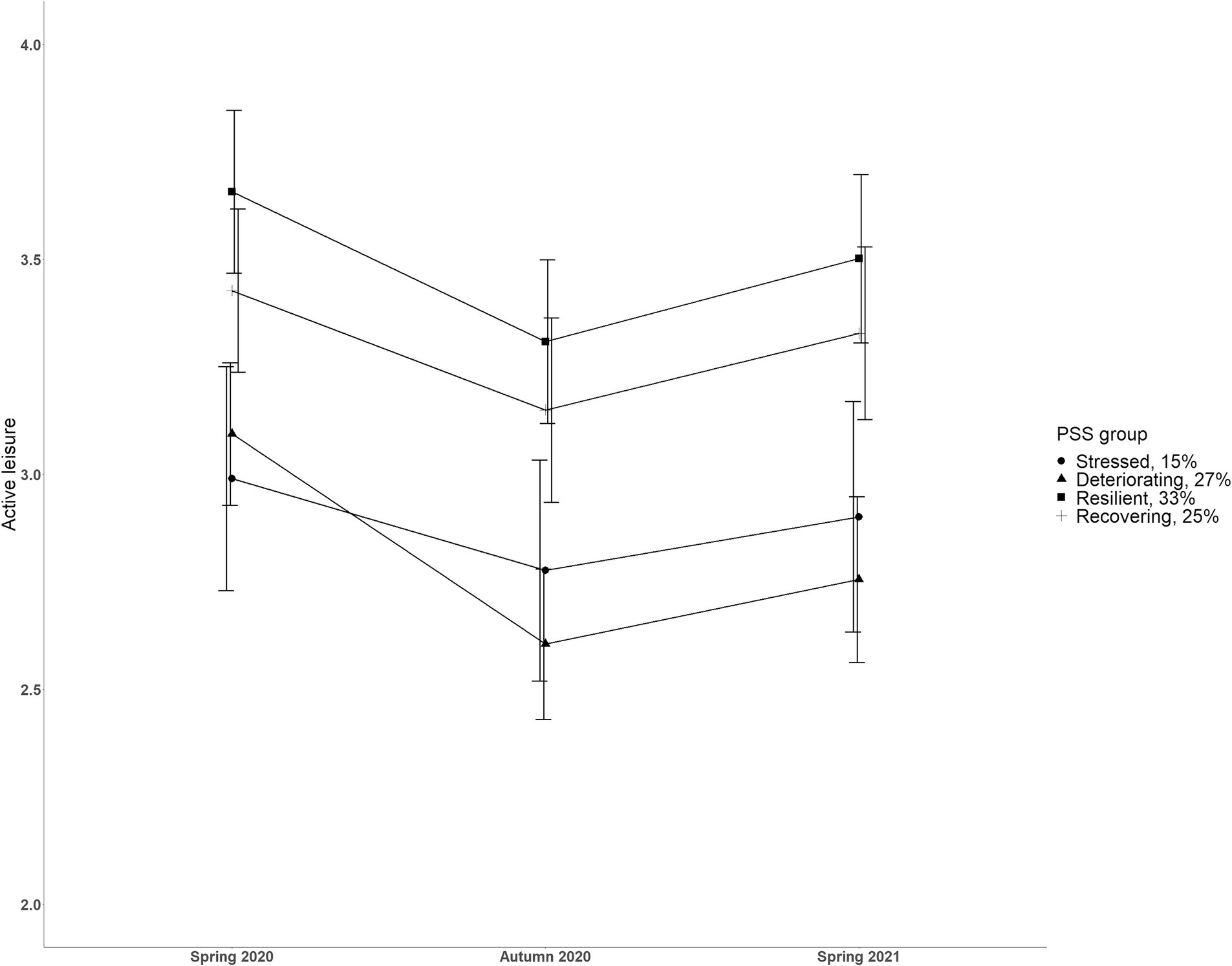

Changes in active leisure engagement were investigated in relation to distinct trajectories of stress and coping. Specifically, a 4 (trajectories) X 3 (timepoints) mixed ANOVA model controlling for age was run to examine the interaction effect between trajectories of stress and coping (group membership as a between-subjects factor) and time (as a within-subjects factor) on active leisure engagement. The mixed ANOVA results are illustrated in Figure 3 .

Figure 3 . Estimated mean active leisure engagement scores across three timepoints according to four distinct stress trajectories. Scale from 1 to 6. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

There was a main effect of time on active leisure engagement, F (1.96, 850.85) = 9.68, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.02. Bonferroni adjusted pairwise comparisons showed a quadratic effect such that active leisure engagement decreased ( p = 0.001) from spring 2020 to autumn 2020, and then increased ( p = 0.001) from autumn 2020 to spring 2021 (see Table 1 for means and SDs). There was a main effect of stress and coping trajectory membership on active leisure engagement, F (3, 434) = 12.18, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.08. Bonferroni adjusted pairwise comparisons revealed that participants belonging to the “Resilient” ( M = 3.46, SD = 0.94) trajectory reported higher active leisure engagement than those in the “Stressed” ( M = 2.93, SD = 0.93) and “Deteriorating” ( M = 2.83, SD = 0.93) trajectories (both comparisons p < 0.001). In addition, participants belonging to the “Recovering” ( M = 3.30, SD = 0.93) trajectory reported higher active leisure engagement than those in the “Deteriorating” ( M = 2.83, SD = 0.93) trajectory ( p < 0.001). The interaction between the stress trajectories and changes in active leisure engagement was not found, F (5.88, 850.85) = 1.30, p = 0.26, η p 2 = 0.009, failing to prove that changes in active leisure engagement were related to distinct trajectories of stress and coping.

4 Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the dynamics of change in stress and its associations with active leisure engagement as a stress coping resource during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our person-centered analytical approach with longitudinal data adds to previous research by identifying heterogeneous trajectories of change in stress among adults. In addition, the current study extends previous research by demonstrating how stress trajectories were characterized by distinct levels of active leisure engagement in times of major social and economic disruptions of the pandemic.

Addressing the first research question, the results from variable-centered analyses indicated that perceived stress and coping levels were stable irrespective of the situation over the first year of the pandemic. Such finding coincides with many of the longitudinal studies on stress levels during the pandemic ( 14 – 16 ). However, as our subsequent person-centered analyses showed, the depiction obtained through the conventional variable-centered approach failed to capture the complexity of the situation.

Our second research question aimed at identifying potentially distinct stress trajectories. The person-centered (latent profile) analyses, based on perceived stress and coping scores measured at three timepoints, revealed a more nuanced understanding of temporal stress dynamics during the first year of the pandemic among adults. Four heterogeneous trajectories of change in stress and coping were identified.

The largest proportion of the sample belonged to the Resilient group (33%), with consistently stable low stress and high coping across the year. This group was composed of individuals who tended to appraise the circumstances as not harmful for them and/or perceived their resources as sufficient to cope with the demands, regardless of the varying conditions throughout the first year of the pandemic ( 11 , 66 ). The clear emergence of such a group also supports Bonanno’s ( 67 ) work on arguing how a substantial proportion of individuals endure aversive events with minor effects on their healthy functioning.

One-quarter of the sample consisted of Recovering individuals, who experienced relatively high levels of stress during the first spring of the pandemic, but “bounced back” during the following year. This favorable adaptation trajectory could be ascribed to novelty, unpredictability, and initial difficulties with new obligations that caused acute stress during the first wave of the virus, but over time adaptation to the conditions occurred and the situation was appraised as less threatening [(see 19 , 68 )].

Over a quarter of our sample belonged to the Deteriorating trajectory, with relatively low stress and high coping at the beginning of the pandemic which was followed by a sustained incline in stress and decline in coping over the study period. A continuous societal and economic crisis, loss of hope for a quick end to the pandemic, and a possible increase in perception of health risks ( 17 ) may have played a role for the individuals in the deteriorating trajectory.

The smallest proportion of our sample belonged to the Stressed group, who experienced high stress and low coping levels throughout the study period. Since we did not possess pre-pandemic data on our sample, it is not possible to credibly attribute high stress levels to the pandemic. Nevertheless, these patterns of increasing or persistently excessive stress levels call for particular attention.

Our analyses demonstrated that focusing only on the average changes (i.e., variable-centered approach) obscures the variability of the temporal changes in stress during the pandemic and could lead to oversimplified inferences. As opposed to the assumption of uniform effects of the varying circumstances of the pandemic on stress levels ( 14 , 17 , 18 ), our study highlights that there was a clear heterogeneity of temporal changes in perceived stress across the first year of the pandemic. More generally, this means that the identification of different subgroups in the temporal process of stress provides an opportunity to describe differences in the details of effective coping with stress. Contrary to our results, a study conducted among adolescents found no evidence of heterogeneity in stress trajectories during the first year of the pandemic ( 16 ). We assume that the different target populations of these studies explain the discrepancy in findings. One possible explanation is that changes in the daily routine of adults were more heterogeneous compared to adolescents (e.g., interruptions in the typical school routines were similar for all students). Among adults, previous studies on mental disorder symptoms during the pandemic that employed a person-centered approach, have consistently shown distinct trajectories of the symptoms’ development ( 21 – 23 ) and thus, support our findings considering the link between stress and psychopathology ( 6 ). Interestingly, the four trajectories also overlap with the prototypical outcome trajectories of human stress responses after potentially traumatic life events [(see 68 )]. It seems that continuous and potentially stressful conditions of the pandemic (i.e., chronic events) were followed by a similar heterogeneity of stress responses across time, as have been observed after short-term aversive life events (i.e., acute events). When considering the socio-demographics potentially associated with the four stress trajectories, our analysis indicated that the distinct trajectories could not be attributed to age, being single (vs. in a relationship), or being employed (vs. not employed). This partially contradicts previous findings which have consistently shown that younger age is related to a higher risk for negatively developing mental health trajectories ( 21 – 23 , 68 ).

Addressing our third and final research question, active leisure engagement across three timepoints was investigated in relation to distinct trajectories of stress and coping. We found that the data collection period had a small effect on average active leisure engagement levels. Even though in the autumn of 2020 there were fewer restrictions on leisure activities than in the rest of the data collection periods, in the autumn of 2020 our study participants were less engaged in active leisure, compared to the spring of 2020 or the spring of 2021. Thus, this finding can be attributed rather to a seasonal effect, as inclement and uncomfortable weather conditions in north temperate zones in autumn have been shown to reduce the frequency of active leisure engagement ( 69 ).

The participants’ active leisure engagement levels were found to differ according to their stress trajectories membership irrespective of the timepoint of assessment. As it was assumed, participants belonging to the positively developing stress trajectories reported higher active leisure engagement than those belonging to the negatively developing stress trajectories (specifically, Resilient compared to Stressed and Deteriorating ; Recovering compared to Deteriorating ). Thus, our findings not only support existing studies ( 30 , 39 , 40 , 47 ) but also extend previous studies by indicating a potentially preventive effect of active leisure engagement on perceived stress during times of crises (while options for leisure are often limited). Importantly, we cannot rule out the possibility of a bidirectional relationship between stress levels and active leisure engagement. It has been previously shown that perception of stress may negatively affect motivation to engage in active leisure ( 44 ). The interaction effect between the changes in active leisure engagement across time and the stress trajectories was not found in our study, indicating that distinct developments in stress during the pandemic were not attributable to the addition of, or shrinkage in, active leisure. However, a slight tendency toward such an effect was noticeable ( Figure 3 ), where individuals in the Deteriorating stress trajectory tended to decrease their active leisure engagement between spring and autumn 2020 more than individuals in other trajectories; and it warrants attention in future research.

5 Limitations

Despite our contributions to a better understanding of the complex temporal dynamics of stress and its longitudinal associations with active leisure engagement in times of major social and economic disruptions, our research has several limitations. First, based on our observational data, we cannot be sure of the direction of associations, and intervention studies are needed to infer causality. A clear limitation is the absence of pre-pandemic data on our sample that would have facilitated a more detailed interpretation of the stress trajectories, and their associations with active leisure engagement. Caution should be taken when interpreting stress levels as ‘due to the pandemic’ since such a supposition remains speculative. Second, we cannot rule out self-selection bias that may have occurred using an online survey; health-conscious people may have been more interested in participating in a mental health study. Most concerning is the underrepresentation of males (7.6%) in our sample. Thus, we must be especially careful when making inferences about men. Challenges with male recruitment are widely documented, especially in online public health surveys ( 70 ). Still, we could not overcome this issue because the data collection needed to be urgently started to study this unpredictable period of the pandemic. Third, additional person-related confounders (e.g., health status, contracting the virus, job insecurity, social support, personality traits) and environmental factors such as season might have influenced our findings. These variables were not included in our study, and we recommend accounting for them in future research. Finally, a rather broad measure of active leisure engagement (i.e., aggregation of three activities) was used in our study, and future research should consider scrutinizing the possible differential and additive effects of specific leisure activities.

6 Conclusion

Our findings indicate substantial variabilities in the level and in the direction of change in stress during an all-embracing socio-historical crisis. The study highlights the importance of considering individual differences in stress appraisal and adopting person-centered approaches to understand the diverse experiences of stress and coping during future crises. Heterogeneous trajectories of perceived stress were characterized by distinct levels of active leisure engagement. Our findings extend previous studies by pointing to the stable link between higher active leisure engagement and lower perceived stress during the pandemic while options for active leisure were often limited. We highlight the importance of promoting and facilitating opportunities for active leisure as a potentially beneficial coping resource during times of crisis. As male participants were underrepresented in our study, special caution should be taken when generalizing the findings to men.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by Tallinn University ethics committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KKu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. A-LJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KKa: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Tallinn University School of Natural Sciences and Health under grant number TA2620.

Acknowledgments

We thank our research group members Kadi Liik, Kristiina Uriko, Avo-Rein Tereping, and Valeri Murnikov for helping to prepare this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1327966/full#supplementary-material

1. Low, RS, Overall, NC, Chang, VT, Henderson, AM, and Sibley, CG. Emotion regulation and psychological and physical health during a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown. Emotion . (2021) 21:1671–90. doi: 10.1037/emo0001046

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Robinson, E, Sutin, AR, Daly, M, and Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord . (2022) 296:567–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098

3. Santomauro, DF, Herrera, AMM, Shadid, J, Zheng, P, Ashbaugh, C, Pigott, DM, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet . (2021) 398:1700–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

4. Tafet, GE, and Nemeroff, CB. The links between stress and depression: psychoneuroendocrinological, genetic, and environmental interactions. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . (2016) 28:77–88. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.15030053

5. Ingram, RE, and Luxton, DD. Vulnerability-stress models In: BL Hankin and JRZ Abela, editors. Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2005). 32–46.

Google Scholar

6. McLaughlin, KA, Rosen, ML, Kasparek, SW, and Rodman, AM. Stress-related psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav Res Ther . (2022) 154:104121. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2022.104121

7. Shi, J, Huang, A, Jia, Y, and Yang, X. Perceived stress and social support influence anxiety symptoms of Chinese family caregivers of community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. Psychogeriatrics . (2020) 20:377–84. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12510

8. Wright, EN, Hanlon, A, Lozano, A, and Teitelman, AM. The impact of intimate partner violence, depressive symptoms, alcohol dependence, and perceived stress on 30-year cardiovascular disease risk among young adult women: a multiple mediation analysis. Prev Med . (2019) 121:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.01.016

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Lindholdt, L, Labriola, M, Andersen, JH, Kjeldsen, MMZ, Obel, C, and Lund, T. Perceived stress among adolescents as a marker for future mental disorders: a prospective cohort study. Scand J Public Health . (2022) 50:412–7. doi: 10.1177/1403494821993719

10. Ben-Zur, H. Transactional model of stress and coping In: V Zeigler-Hill and T Shackelford, editors. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences . Cham: Springer (2019).

11. Lazarus, RS, and Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping . New York: Springer (1984).

12. Cohen, S, Kamarck, T, and Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav . (1983) 24:385–96. doi: 10.2307/2136404

13. Boluarte-Carbajal, A, Navarro-Flores, A, and Villarreal-Zegarra, D. Explanatory model of perceived stress in the general population: a cross-sectional study in Peru during the COVID-19 context. Front Psychol . (2021) 12:673945. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.673945

14. Gori, A, and Topino, E. Across the COVID-19 waves; assessing temporal fluctuations in perceived stress, post-traumatic symptoms, worry, anxiety and civic moral disengagement over one year of pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health . (2021) 18:5651. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115651

15. Slurink, IA, Smaardijk, VR, Kop, WJ, Kupper, N, Mols, F, Schoormans, D, et al. Changes in perceived stress and lifestyle behaviors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands: an online longitudinal survey study. Int J Environ Res Public Health . (2022) 19:4375. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074375