- LOGIN & Help

The Case Study Method in Social Inquiry

- Educational Psychology

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

ASJC Scopus subject areas

Online availability.

- 10.3102/0013189X007002005

You are here

Case Study Method Key Issues, Key Texts

- Roger Gomm - The Open University

- Martyn Hammersley - The Open University, UK

- Peter Foster

- Description

`This is a worthwhile book which will be useful to readers. It collects

together key sources on a topic which is a "hardy perennial", guaranteeing

its relevance for academics, researchers, and students on higher level

methods programmes. The editorial contributions are by well-known

authorities in the field, are carefully-constructed, and take a clear

position. I would certainly want this book on my shelf' - Nigel Fielding, University of Surrey

". . .the book enlightens researchers concerning the contributions of case studies to research and could serve as an informative reader for doctoral students considering case study methods for their dissertations."

Extremely well written with range of chapters by various authors. Invaluable reading for any student considering using a case study approach for their research project.

offers deep theoretical insight to the issue of generalizability; language could be a bit difficult for 3rd year UG students; however, I would adopt it as supplemental - for students that wish to go the extra mile.

So many well established names in the field of case study research makes this book a fascinating and very helpful resource. Its two main sections cover two vital areas that are often controversial within this method. The multitude of references from each chapter's Bibliography, leave the reader with a gold mine of sources to further investigate.

One of the key considerations in Cast Study research is the complexity relating to generalisability. This text explores generalisability in depth, giving the novice and more mature researcher greater depth and understanding of transferrability of research findings to the wider population.

For anyone thinking about undertaking case study research, I would highly recommend this text. The phrase 'case study' itself is something that is difficult to agree on and this book helps clarify thinking about what a 'case study' really is and then how to go about designing and carrying out case study research.

An excellent book for students undertaking Case Study Research

This is an excellent text for students undertaking case study research.

Preview this book

For instructors.

Please select a format:

Select a Purchasing Option

- Electronic Order Options VitalSource Amazon Kindle Google Play eBooks.com Kobo

Related Products

SAGE Research Methods is a research methods tool created to help researchers, faculty and students with their research projects. SAGE Research Methods links over 175,000 pages of SAGE’s renowned book, journal and reference content with truly advanced search and discovery tools. Researchers can explore methods concepts to help them design research projects, understand particular methods or identify a new method, conduct their research, and write up their findings. Since SAGE Research Methods focuses on methodology rather than disciplines, it can be used across the social sciences, health sciences, and more.

With SAGE Research Methods, researchers can explore their chosen method across the depth and breadth of content, expanding or refining their search as needed; read online, print, or email full-text content; utilize suggested related methods and links to related authors from SAGE Research Methods' robust library and unique features; and even share their own collections of content through Methods Lists. SAGE Research Methods contains content from over 720 books, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and handbooks, the entire “Little Green Book,” and "Little Blue Book” series, two Major Works collating a selection of journal articles, and specially commissioned videos.

Conducting Case Study Research in Sociology

Steve Debenport / Getty Images

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

A case study is a research method that relies on a single case rather than a population or sample. When researchers focus on a single case, they can make detailed observations over a long period of time, something that cannot be done with large samples without costing a lot of money. Case studies are also useful in the early stages of research when the goal is to explore ideas, test, and perfect measurement instruments, and to prepare for a larger study. The case study research method is popular not just within the field of sociology, but also within the fields of anthropology, psychology, education, political science, clinical science, social work, and administrative science.

Overview of the Case Study Research Method

A case study is unique within the social sciences for its focus of study on a single entity, which can be a person, group or organization, event, action, or situation. It is also unique in that, as a focus of research, a case is chosen for specific reasons, rather than randomly , as is usually done when conducting empirical research. Often, when researchers use the case study method, they focus on a case that is exceptional in some way because it is possible to learn a lot about social relationships and social forces when studying those things that deviate from norms. In doing so, a researcher is often able, through their study, to test the validity of the social theory, or to create new theories using the grounded theory method .

The first case studies in the social sciences were likely conducted by Pierre Guillaume Frédéric Le Play, a 19th-century French sociologist and economist who studied family budgets. The method has been used in sociology, psychology, and anthropology since the early 20th century.

Within sociology, case studies are typically conducted with qualitative research methods . They are considered micro rather than macro in nature , and one cannot necessarily generalize the findings of a case study to other situations. However, this is not a limitation of the method, but a strength. Through a case study based on ethnographic observation and interviews, among other methods, sociologists can illuminate otherwise hard to see and understand social relations, structures, and processes. In doing so, the findings of case studies often stimulate further research.

Types and Forms of Case Studies

There are three primary types of case studies: key cases, outlier cases, and local knowledge cases.

- Key cases are those which are chosen because the researcher has a particular interest in it or the circumstances surrounding it.

- Outlier cases are those that are chosen because the case stands out from other events, organizations, or situations, for some reason, and social scientists recognize that we can learn a lot from those things that differ from the norm .

- Finally, a researcher may decide to conduct a local knowledge case study when they already have amassed a usable amount of information about a given topic, person, organization, or event, and so is well-poised to conduct a study of it.

Within these types, a case study may take four different forms: illustrative, exploratory, cumulative, and critical.

- Illustrative case studies are descriptive in nature and designed to shed light on a particular situation, set of circumstances, and the social relations and processes that are embedded in them. They are useful in bringing to light something about which most people are not aware of.

- Exploratory case studies are also often known as pilot studies . This type of case study is typically used when a researcher wants to identify research questions and methods of study for a large, complex study. They are useful for clarifying the research process, which can help a researcher make the best use of time and resources in the larger study that will follow it.

- Cumulative case studies are those in which a researcher pulls together already completed case studies on a particular topic. They are useful in helping researchers to make generalizations from studies that have something in common.

- Critical instance case studies are conducted when a researcher wants to understand what happened with a unique event and/or to challenge commonly held assumptions about it that may be faulty due to a lack of critical understanding.

Whatever type and form of case study you decide to conduct, it's important to first identify the purpose, goals, and approach for conducting methodologically sound research.

- An Overview of Qualitative Research Methods

- Understanding Secondary Data and How to Use It in Research

- Definition of Idiographic and Nomothetic

- Pilot Study in Research

- What Is Ethnography?

- How to Conduct a Sociology Research Interview

- The Sociology of the Internet and Digital Sociology

- What Is Participant Observation Research?

- Understanding Purposive Sampling

- The Different Types of Sampling Designs in Sociology

- Units of Analysis as Related to Sociology

- What Is Naturalistic Observation? Definition and Examples

- Social Surveys: Questionnaires, Interviews, and Telephone Polls

- Anthropology vs. Sociology: What's the Difference?

- Deductive Versus Inductive Reasoning

- How to Understand Interpretive Sociology

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Advertisement

Progress in Social and Educational Inquiry Through Case Study: Generalization or Explanation?

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 23 July 2016

- Volume 45 , pages 253–260, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gary Thomas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4937-0622 1

4305 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Although much of the most productive research in applied social science is case-based, there is still concern about the restricted utility of such research because of its limited power to offer generalizable findings. Such concern has contributed to a recent trend in policy-making circles—particularly those in education—to prefer experimentally orientated research for insights on policy. The argument is made here that concerns about generalization are exaggerated and that the focus upon them has allowed an evasion of issues about quality of explanation coming from different forms of social inquiry design. After discussing these generalization-based issues I proceed to define case study as an inquiry form, outlining its most significant ingredients and I offer a review of case study inquiries in education which exemplify its capacity for offering credible new insights on the questions being posed.

Similar content being viewed by others

A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis

When Does a Researcher Choose a Quantitative, Qualitative, or Mixed Research Approach?

Social Constructivism—Jerome Bruner

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There have been many recent injunctions, including those from national governments, for researchers to use particular kinds of quantitatively orientated and experimental research in social and educational inquiry (see, for example, Goldacre 2013a , b ; Prenzel 2009 ; Shavelson and Towne 2002 ; Slavin 2008 ; U.S. Department of Education 2004 ). Such research, it is sometimes asserted, provides “gold standard evidence.” I hope to make the case in this article, though, that the most influential, transformative education research comes not from the stable of experimental study but rather from explorations which are case orientated. Such research offers to education kinds of understanding which are inaccessible via formal kinds of trial and experiment. In using the “science of the singular” (Simons 1980 ) such inquiry promises to inform education practitioners in their own environments, where they can provide “research in practice, not research on practice,” as Friedman ( 2006 , p. 132) has put it (see also, Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009 ).

Over half a century and more, the most iconic analyses of education have come about from case study research, which can provide a uniquely vivid kind of inquiry and furnish the quality of analysis which is impossible from other kinds of research. Early examples include Philip Jackson’s ( 1968 ) Life in Classrooms, Harry Wolcott’s ( 1978 ) The Man in the Principal’s Office , Stephen Ball’s ( 1981 ) Beachside Comprehensive and Paul Willis’s ( 1993 ) Learning to Labor, all of which have contributed enormously to our understanding of the ways that schools work, teachers teach, and students learn. I shall look at these exemplars, and other examples of first-rate case study in education, later in this article.

While the case study has a relatively recent history in education, it has a longer pedigree in other disciplines. Garvin notes ( 2003 ) that it was a lawyer who had, in 1870, named case study method, with the use of the case study at that time in undergraduate teaching. The case had begun to be used, though, around the same time and a little before, in explicating and analyzing social and psychological phenomena. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard described his now-celebrated work with Victor, the “wild boy of Aveyron”, and later in the century Frédéric Le Play made his highly influential studies of the working and living conditions of French miners in the Jura (see Mogey 1955 ).

The aim of these early inquirers was to report and theorize about a particular person or set of people. Analysis based on this kind of work began to chime, at the beginning of the twentieth century, with new thought about social inquiry and how it should be undertaken. It resonated with new ideas about interpretative inquiry, encapsulated in the new anthropology and symbolic interactionism, in such a way that it became a force in and of itself. The case study, exemplified in, for example, Thomas and Znaniecki’s ( 1927 /1958) explication of the life of American immigrants, The Polish Peasant in Europe and America , became an accepted and respected form of research.

Since then, the case study has been used increasingly to illuminate and explicate the social worlds we inhabit. And the different examples to which I have just been referring reveal very different kinds of case study with equally varied means of gathering data and analyzing it, from the use of people’s letters to each other, as in The Polish Peasant …, to rich, narrative accounts, as in Clifford Geertz’s ( 1973 ) notes on the Balinese cockfight. The fertility of the descriptions in these exemplars is sometimes quite striking—descriptions incorporating imagination, conjecture and theorization. The best case studies weave discussion and theorization with the presentation of the case account itself.

The case study presents a view of inquiry that takes a pragmatic view of knowledge—one that elevates a view of life in its complexity. It’s the realization that complexity in social affairs is often indivisible that has led to case study’s status as currently one of the most productive design frames open to the researcher. This is perhaps the reason behind its ongoing popularity among researchers in the field of education and other applied social sciences.

What is Case Study?

There are strong commonalities about what case study constitutes across disciplinary boundaries. Reviewing a number of definitions of case study, Simons ( 2009 ) concludes that what unites them is a commitment to studying the complexity that is involved in real situations, and to defining case study other than by the methods of data collection that it employs. On the basis of these commonalities she offers this definition: “Case study is an in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of the complexity and uniqueness of a particular project, policy, institution, program or system in a ‘real life’ context” (p. 21).

The emphasis in Simons’s definition is on depth of analysis. In it, one finds a “trade-off”, as Hammersley and Gomm ( 2000 , p. 2) put it, between the rich, in-depth explanatory narrative emerging from a very restricted number of cases and the capacity for generalization that a larger sample of a wider population can offer. It is important to add to Simons’s definition the rider that case study should not be seen as a method in and of itself. Rather, it is a design frame that may incorporate a number of methods. Stake ( 2005 ) puts it thus:

Case study is not a methodological choice but a choice of what is to be studied … By whatever methods we choose to study the case . We could study it analytically or holistically, entirely by repeated measures or hermeneutically, organically or culturally, and by mixed methods—but we concentrate, at least for the time being, on the case. (p. 443)

Choice of method, then, does not define case study: analytical eclecticism in the in-depth study of a subject of interest is the key. Alongside holism and methodological eclecticism the case inquirer needs carefully to consider the nature of what is being studied, analytically speaking.

As I have discussed elsewhere (Thomas 2013 ), case study is one of the scaffolds that can help to structure the design of research. As I have defined them (Thomas 2011 ) case studies are

… analyses of persons, events, decisions, periods, projects, policies, institutions or other systems which are studied holistically by one or more methods. The case that is the subject of the inquiry will be an instance of a class of phenomena that provides an analytical frame—an object—within which the study is conducted and which the case illuminates and explicates.

The emphasis in this definition is on analysis; I try to make it clear that while case inquiry may often rely on observation, and to an extent description, these are not ends in themselves and the best case studies go much further than illumination. The definition makes a separation between the subject, the focus, of the study and the theoretical issue that this subject explicates. In it I have drawn on the work of Wieviorka ( 1992 ), who made the point that a case in a case study cannot be simply an instance of a class. Wieviorka unpacked in more detail the distinctions between the case and the class by noting that when we talk about a case we are in fact talking about two elements: first, there is what he calls a ‘practical, historical unity’ (p. 159). We might call this the subject . Second, there is what he calls the ‘theoretical, scientific basis’ of the case.

In other words, it is important for case inquirers to be clear about what the case study is a case study of. A case study, as a study (as distinct from a case illustration or a case history) must in some sense explicate a wider theme: it must help in our understanding of some theoretical issue.

Methodological Issues for the Case Study in Education

- Generalization

… situations are so varied that even a large number of cases may be a misleading sample … and none is comprehensible outside the historical sequence in which it grew. (Vickers 1965 , p. 173)

Here, Vickers states the principal reason for the sometimes suspect status of case study as a research design form. This suspicion stems principally from the assumed paucity of general understanding offered by case study. It is general understanding that is the key, and generality goes to the heart of the matter, for it is here, in generality or universals that we find issues of what social science, and particularly theory in social science, has distinctively to offer. This emphasis on generalized knowledge is a problem for case study, which appears to offer little in the way of generalizable information to social scientific inquiries.

Bassey ( 2001 ), however, writing from the context of education, notes that “it is possible to distinguish between two modes of research, namely search for generalities and study of singularities” (p. 6). He picks up Simons’s ( 1980 ) notion of the “singularity” of the educational situation—that singular status implying everything within the boundary of what is under study. It is, as Bassey puts it (ibid), “one set of circumstances and the events, people, places and things, which constitute that set of circumstances, [which] are treated in the study as an entity.”

Bassey firmly sets the issue of generalization in the context of the classroom. He says:

Open generalizations give reliable predictions and so are obviously valuable in the making of classroom decisions. But, in my view, they are scarce in number and so once these few have been mastered, and have become an integral part of a teacher’s way of operating, they appear obvious and no longer valuable.

He concludes that the education research community should

… distinguish between pedagogic research and other forms of educational research, and in relation to pedagogic research should eschew the pursuit of generalizations, unless their potential usefulness is apparent, and instead should actively encourage the descriptive and evaluative study of single pedagogic events.

I have continued the discussion about generalization elsewhere (Thomas 2011 ), noting that “the study must be framed not in the diluted constructs of generalizing natural science but rather in questioning and surprise, heuristic, particularity, analogy, consonance or dissonance with my own situation” (p. 33). The case study, I have concluded, is of course about understanding some phenomenon or construct, but understanding it in the context of what Gadamer ( 1975 ) calls one’s “horizon of meaning” (p. 269). The conclusion is that while precise forms of generalization are impossible—particularly the tight generalization of the natural scientist—the obverse of this observation is that no situation is unique: each is interpreted in the context of our own experience. To interpret in the context of one’s own experience is both legitimate and valid.

For me, the issue about generalization is less troublesome than many fear, for much scientific inquiry is not actually about generalization but, rather, understanding. This is true in any domain of inquiry. Scientists—from astronomers to zoologists—seek understandings on the basis of evidence, which is painstakingly sought, evaluated and used to make the best possible conjectures and explanations of the phenomena in question. While some of these explanations will require certain kinds of rigorous generalization, others do not.

Is It Science?

Atkinson and Delamont ( 1985 ) argue trenchantly for the need for case inquirers to develop a well formulated body of theory and methods in order to produce a coherent, cumulative research tradition. In doing this, they are developing a theme that has been much discussed in qualitative research. The issue is about science and legitimacy of this or that method (Thomas and James 2006 ) and here Kemmis ( 1980 ) makes the point that case studies are sometimes dismissed as purely subjective. They are thus seen as unscientific and are regarded with suspicion, even hostility, by some social scientists. He makes the point that case study is indeed science: it is truth-seeking and in the quest for public knowledge. In discussing the putative pillars of scientific credibility in social science—reliability and validity—he asks what estimates of reliability can be given for a field-note jotted down in the chaos of a classroom discussion.

Lather ( 2004 ) also takes on the theme of science, regretting the call for certain kinds of science in recent government reports—particularly in the discourse which stems from the landmark US piece of education legislation, No Child Left Behind , which demanded that teachers use only scientifically proven methods in their teaching. It’s a theme I have taken up myself (Thomas 2012 ): the point is that there is no core to scientific method, no charmed circle of precepts and processes that lead the incipiently scientific inquirer to the sunlit uplands of scientific inquiry. My argument, similar to Lather’s, is about the ways that we choose to be scientific in education inquiry and the consequences that such choices have for the nature and growth of our field of endeavor—our own science.

Stenhouse ( 1978 , 1980 ) conjoins discussion of these issues that concern the legitimacy of case study with concern about generalization. He sets case study in the context of research and what research should be. He is concerned in particular about verification and cumulation in case studies conducted in field settings in education, and he concludes that case study is a basis for generalization and hence cumulation of data. He proceeds to assert, in response to questions about the usefulness of case study that practice will improve when experience is systematically marshalled as history. He asks for the accumulation of an archive of case records. The concern is to provide a cumulative body of knowledge. But, as I have suggested elsewhere (Thomas 2012 ) expectation about cumulation in our scientific inquiry in education has to rest on an accumulation not of generalizable facts but of understandings drawn from and assessed in the context of one’s own experiences and the experiences of others. It rests, in other words, in the cultivation of provisional, tentative models for interpretation and analysis.

Smith ( 1978 ) described well the process of cultivating tentative models for interpretation in his account of the “miniature theories” (p. 363) which teachers develop and share (and see also Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009 ). Ideas about how it can be conducted have traveled various avenues from Lewin’s ( 1946 ) action research to Checkland’s soft systems ( 1981 ) to Bryk et al’s ( 2015 ) improvement science.

Some Examples of Case Study in Educational Science

I have already mentioned three classic texts—Paul Willis’s Learning to Labor, Harry Wolcott’s The Man in the Principal’s Office and Stephen Ball’s Beachside Comprehensive —and it is worth going into some more detail on these before looking at other exemplars of the case study design frame.

Using case study, each of these researchers has done much for our understanding of the ways that schools work. They have achieved this by painting pictures in fine-grain detail about the encounters that occur in schools amongst staff and students.

Learning to Labour is often described as a classic ethnography. In it, Willis untangles how the young people at the “Hammertown” school—a school with a predominantly working class catchment in the English midlands—developed an antagonism towards school. They developed what Willis calls a counter school culture . They did this via what Willis calls differentiation . He says “ Differentiation is the process whereby the typical exchanges expected in the formal institutional paradigm are reinterpreted, separated and discriminated with respect to working class interests, feelings and meanings” (p. 62). He intertwines the development of the theoretical narrative about differentiation and counter culture with observations and illustrations from the case study itself. There is surely no way that such insights could have come from any frame of research other than case study here.

Ball ( 1981 ), in Beachside Comprehensive , presents a case study of a school and its pupils at a particular moment of change for education. He seeks to understand how the pupils “make sense of school as part of their whole life-world” (p. 109). His work is interesting as case study for the data-collection methods that he uses (questionnaires, diaries) and the ways that he simultaneously incorporates insights from the work of others. In an echo of the “differentiation” and “counter culture” of Willis, Ball reveals how, especially in the final year of compulsory education at a time when the school leaving age was rising, pupils accepted or rejected the goals of the school, and how those who more conspicuously rejected it were in turn viewed as failures by the teachers.

Before both of these studies, in 1973, was Wolcott’s The Man in the Principal’s Office: an Ethnography, which was one of the first detailed ethnographies undertaken in education. The work shows the range of data collection and analytical techniques open to the case inquirer. Wolcott notes the contradiction present in educators’ espoused wish to be seen as integrated with their communities while making their own subculture at school a relatively closed one.

Then there are case studies which reveal their power to change through enabling genuinely fresh theoretical insight. From the very beginning of Ferguson’s ( 1992 ) The Puzzle of Inclusion: a Case Study of Autistic Students in the Life of One High School the reader is immersed in the case. Immediately, we are encouraged to think about the situation itself, to hypothesize, to make our own assessments and judgements about what is happening. The author, therefore, relinquishes control over the interpretations, as Sparkes ( 2007 ) puts it—interpretations about the integration of autistic students into a mainstream school. The case is fascinating for the insights it offers on inclusion. Importantly for case study, Ferguson challenges any assumption that his case study school is in any way typical, nor need it be, he says. He concludes with a key statement:

Each high school … has its own set of unique events and specific personalities that interact with larger social forces and structures to construct its own pattern of understanding itself. Case studies are intended to reveal those patterns in as rich detail as possible. This does not mean that generalizations are impossible or even undesirable. Rather it simply places most of the responsibility for generalization to other settings on the readers themselves who know those other settings best. It is my responsibility as the writer to provide a thick enough description for the readers to make such judgments and comparisons. (p. 166)

Ferguson vividly illuminates the work of the case inquirer here. It reminds us that the work of the researcher in this form is truly theoretically grounded, with the constructs emerging from the research itself rather than being orphaned to some preordained theoretical construct.

In this, Ferguson’s work is like Wright’s ( 2010 ) case study of a small child and her mother. This chronicles, reflects upon and analyzes the emotional stasis and eventual thawing and trust of a little girl with whom Wright was working. Because of the case study approach, it is refreshingly free of the quasi-explanatory constructs that so often characterize accounts of breakdown in learning or emotional development at school. Wright’s explanation about the girl’s withdrawal comes directly from what he saw and what he knew. His intuitions about how to behave with her came from his own experiences as a person and a professional, one with experience of other people, and one who approaches others with humanity, understanding and a will to succeed. We, the readers, read in the context of our own experience, our own horizons of understanding.

In a study of reading failure, Johnston ( 1985 ) did something similar. He gave a case study examination of reading failure and found reasons for this failure more in students’ anxiety than in putative psychological deficits, where traditional educational and psychological science so often have sought within-child explanations. Like Ferguson and Wright, Johnston found failure at school to depend on the context and culture for learning. It is only through the rich and detailed study of individual cases that such analyses of children’s difficulties at school can be made. Such work shows that students’ success or failure at school is due less to “learning disabilities” and more to an array of factors around which acceptance and inclusion are constructed.

A similar set of new, rich explanations, divorced from the traditional starting points of the educator looking for explanation of why children fail come from Hart et al. ( 2004 ), who tell the story of one teacher, Julie. It’s one case study among nine in their book Learning without Limits , describing and analyzing how teachers developed alternative practices in their classrooms to move away from notions of fixed ability and disability, including “learning disability”. It shows how teachers use principles of “accessibility” and “emotional well-being” together with expectations about minimum levels of achievement for each child. Hart and her colleagues are putting into practice what Ferguson was suggesting—enabling through rich description an assessment by the reader of the transferability from one situation to another.

All of these case studies force serious re-thought about many of the pseudo-scientific constructs around which “failure” at school is often constructed. They do this by compelling a direct analysis of the case that is in front of the inquirer. The analyses come not from pre-packaged theorization that puts “failure” into this or that box with this or that label, but rather from insights which emerge from the authors’ own experiences as people and as professionals. We read their accounts and understand them in the contexts of our own experiences, our own horizons of understanding.

There are other examples of case study use in education that demonstrate well that this form of design need not follow an ethnographic route. Cremin et al. ( 2005 ) outline the use of what is sometimes called an n = 1 design, unusual in the case study genre for its employment of an experimental approach. As I have noted, methodologists such as Stake ( 2005 ; 443) have emphasized that case study is not a methodological choice but rather “a choice of what is to be studied” and Cremin et al. demonstrate this point in this experimental study. The researchers look at six classrooms in detail, examining the work of teaching assistants and in particular imposing three different kinds of organization for the work of those assistants in the classrooms. The different organizational methods are compared using a repeated measures experimental design and the findings of this are complemented by commentary from the staff participating in the study.

The terms “experiment” and “case study” are also juxtaposed by Driessen and Pyfer ( 1975 ), though here the “experiment” is an experiment only in the sense of trying something out. These researchers report on an evaluation of a program in adult basic education which was given in informal home settings instead of traditional classrooms. The aim was to meet the needs of “208 adults who wanted formal educational skills, but who found it neither comfortable nor appealing to participate in formal classroom settings” (p. 112). The whole trial is analyzed qualitatively. The use of the term “experiment” in this kind of study raises the issue of what a scientific experiment needs to look like in social science. It needn’t look like the experiments used in plant science and medicine. It can be far simpler, and I have discussed elsewhere the expropriation of the term “experiment” (Thomas 2016 ).

García et al. ( 2012 ) give literally a case history of the Oxnard schools in California—a history of what the authors call “mundane racism” (p. 2)—almost routine, taken-for-granted racism. Using school records and census records, they show how the school board’s decade-long “obsession” (p. 2) with segregation “effectively established a permanent dual schooling system that replicated racial hierarchy” (p. 2). This ingenious work both motivates and informs, providing not just a window on practices formative of some of today’s prejudices but also insights about how to move forward.

Two further examples demonstrate the value of the case study approach in education in the whole process of understanding teaching, learning and development. Duckworth ( 1986 ) reflects on a project in which she as a researcher and tutor asked teachers to engage in moon-watching—as a novel kind of task, the kind wherein empathy could be experienced with classroom learners—in order to reflect on their understanding of the sort of learning and teaching that might be expected at school. She concludes that “they make sense by trying out their own ideas, by explaining what they think and why, and seeing how this holds up in other people’s eyes, in their own eyes, and in the light of the phenomena they are trying to understand” (p. 487). This is summed up in the understanding of “teaching as research”. Hennessy, Mercer and Warwick do something similar ( 2011 ), showing how researchers and teachers could co-construct this process. They describe co-inquiry wherein, as the authors put it, “collaborative theory-building” (p. 1910) happened. Out of the process, pedagogical rationales were shifted and altered. The authors describe the ways that the case study enabled elucidatory work with teachers, suggesting that a rich set of perspectives could emerge: all the teachers would discuss insights which might develop as they orientated themselves to others’ perspectives.

I’ll finish this mini-sample of case studies in education with Jiménez and Gersten’s ( 1999 ) analysis of two distinct approaches to instruction provided by two bilingual teachers. They offer these as lessons and dilemmas which they have drawn from the literacy instruction of these two teachers. Their conclusion about the “method” of their work sums up much of the method of the case inquirer, for they say that their work aims to create what Wolcott called little theories. They note that Wolcott believed that education is best served by the generation of multiple insights tailored to specific situations and grounded in the expertise of those who work in those situations. These little theories, they suggest, are inductively derived conclusions concerning instruction and learning.

Conclusions

Case study is about explanation through in-depth inquiry and insider accounts, producing “little theories” and “miniature theories”, via the “multiple realities” of Berger and Luckmann ( 1979 ). These prove to be the life-blood of serious, transformative inquiry in education. All of the studies I have drawn from in the previous section of this article force serious re-thought about many of the pseudo-scientific constructs around which ideas about students’ experience at school is often constructed. They do this by compelling a direct analysis of the case that is in front of the inquirer. The analyses come not from the kind of pre-packaged theorization which so often guides the understanding of putatively gold standard experimentation, but rather from insights which emerge from the authors’ own experiences as people and as professionals.

In whatever field, scientific inquiry seeks to answer questions and to solve puzzles. That is its purpose. It looks for explanations—clarification, illumination, enlightenment—about how and why things happen as they do. We conjoin ideas, make connections, test hypotheses, recognize themes, and build models of the way the world works. We seek, as Einstein put it, “in whatever manner is suitable, a simplified and lucid image of the world” (cited in Holton 1995 , p. 168). Our inquiries, our questions and answers, assist in building what Harré ( 2012 )—in explaining the purpose of social science—called “working models of some aspect of social life.” We do this eclectically, and we do it, natural scientists and social scientists alike, through case study as much as experimentation.

For social scientists also seek “a simplified and lucid image” of the worlds in which they work—in whatever way. There can be no specific, superior type of question; no sunlit path to the perfect inquiry. Rather, there is variety. But this variety should not be seen as social science’s Achilles’ heel, accompanied by a laying out of hierarchies of better and worse kinds of research. We should, cherish, not disown, methodological pluralism and value the insights and understandings which come from case study.

None of this, of course—none of the call for pluralism and complementarity, with appropriate respect afforded to case study, ethnographic or more generally qualitative social inquiry forms—is to deny the absolute need for rigor in the conduct and analysis of research. As sociologist Robert Merton ( 1976 ) argued some time ago, the need is for “disciplined eclecticism” (p. 169) and his entreaty is still relevant. Funders need to be convinced of the quality and the intermeshing contributions of different forms of inquiry. They need to be convinced, in other words, of the matrix-like nature of inquiry forms, as Hammersley ( 2015 ) put it. Many advocates of experimental methodology recognize this—recognize, in other words, the slenderness of insight provided by experimental work and incorporate case study and other qualitative elements into their design frameworks to provide such insights. The onus has to be on case inquirers to argue for the contribution of idiographic inquiry to the findings of such research, as well arguing for the analytic power demonstrated in the kinds of study I have reviewed in this paper.

Atkinson, P., & Delamont, S. (1985). Bread and dreams or bread and circuses? A critique of ‘case study’ research in education. In M. Shipman (Ed.), Educational research: Principles, policies and practices (pp. 26–45). London: Falmer.

Google Scholar

Ball, S. (1981). Beachside comprehensive: A case-study of secondary schooling . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bassey, M. (2001). A solution to the problem of generalization in educational research: Fuzzy prediction. Oxford Review of Education, 27 (1), 5–22.

Article Google Scholar

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1979). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge . London: Penguin.

Bryk, A., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Checkland, P. (1981). Systems thinking, systems practice . Chichester: Wiley.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research in the next generation . New York: Teachers College Press.

Cremin, H., Thomas, G., & Vincett, K. (2005). Working with teaching assistants: Three models evaluated. Research Papers in Education, 20 (4), 413–432.

Driessen, J. J., & Pyfer, J. N. (1975). An unconventional setting for a conventional occasion: A case study of an experimental adult education program. Sociology of Education, 48 (1), 111–125.

Duckworth, E. (1986). Teaching as research. Harvard Educational Review, 56 (4), 481–495.

Ferguson, P. (1992). The puzzle of inclusion. In P. M. Ferguson, D. L. Ferguson, & S. J. Taylor (Eds.), Interpreting disability: A qualitative reader (pp. 145–167). New York: Teachers College Press.

Friedman, V. J. (2006). Action science: Creating communities of inquiry in communities of practice. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (pp. 131–143). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1975). Truth and method . New York: Seabury Press.

García, D. G., Yosso, T. J., & Barajas, F. P. (2012). “A few of the brightest, cleanest Mexican children”: School segregation as a form of mundane racism in Oxnard, California, 1900–1940. Harvard Educational Review, 82 (1), 1–25.

Garvin, D. A. (2003). Making the case: Professional education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine, 106 (1), 56–107.

Geertz, C. (1973). Deep play: Notes on the Balinese cockfight. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (pp. 412–453). New York: Basic Books.

Goldacre, B. (2013a). Teachers! What would evidence based practice look like ? Retrieved from http://www.badscience.net/2013/03/heres-my-paper-on-evidence-and-teaching-for-the-education-minister/#comments

Goldacre, B. (2013b). Building evidence into education . London: Bad Science. Retrieved from http://media.education.gov.uk/assets/files/pdf/b/ben%20goldacre%20paper.pdf

Hammersley, M. (2015). Against ‘gold standards’ in research: On the problem of assessment criteria . Paper given at ‘Was heißt hier eigentlich “Evidenz”?’, Frühjahrstagung 2015 des AK Methoden in der Evaluation Gesellschaft für Evaluation (DeGEval), Fakultät für Sozialwissenschaften, Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft des Saarlandes, Saarbrücken, Germany, May. Retrieved from http://www.degeval.de/fileadmin/users/Arbeitskreise/AK_Methoden/Hammersley_Saarbrucken.pdf

Hammersley, M., & Gomm, R. (2000). Introduction. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, & P. Foster (Eds.), Case study method . London: SAGE.

Harré, R. (2012). Rom Harré on What is Social Science? Social Science Space . Retrieved from http://www.socialsciencespace.com/2012/05/rom-harre-on-what-is-social-science/

Hart, S., Dixon, A., Drummond, M. J., & Mcintyre, D. (2004). Learning without limits (pp. 137–147). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Hennessy, S., Warwick, P., & Mercer, N. (2011). A dialogic inquiry approach to working with teachers in developing classroom dialogue. Teachers College Record, 113 (9), 1906–1959.

Holton, G. (1995). The controversy over the end of science. Scientific American, 273 (4), 168.

Jackson, P. (1968). Life in classrooms . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Jimenez, R. T., & Gersten, R. (1999). Lessons and dilemmas derived from the literacy instruction of two Latina/o Teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 36 (2), 265–302.

Johnston, P. H. (1985). Understanding reading disability: A case study approach. Harvard Educational Review, 55 (2), 153–177.

Kemmis, S. (1980). The imagination of the case and the invention of the study. In H. Simons (Ed.), Towards a science of the singular (pp. 96–142). Norwich: Centre for Applied Research in Education, University of East Anglia.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education’. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2 (4), 34–46.

Merton, R. K. (1976). Sociological ambivalence . New York: The Free Press.

Mogey, J. M. (1955). The contribution of Frédéric Le Play to family research. Marriage and Family Living, 17 (4), 310–315.

Prenzel, M. (2009). Challenges facing the educational system. Vital questions: The contribution of European social science (pp. 30–33). European Science Foundation: Strasbourg.

Shavelson, R. J., & Towne, L. (Eds.). (2002). Scientific research in education . Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Simons, H. (Ed.). (1980). Towards a science of the singular . Norwich, UK: Centre for Applied Research in Education, University of East Anglia.

Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice . London: SAGE.

Book Google Scholar

Slavin, R. E. (2008). Perspectives on evidence-based research in education: What works? Issues in synthesizing educational program evaluations. Educational Researcher, 37 (1), 5–14.

Smith, L. M. (1978). An evolving logic of participant observation, educational ethnography, and other case studies. Review of Research in Education, 6 (1), 316–377.

Sparkes, A. C. (2007). Embodiment, academics, and the audit culture: A story seeking consideration. Qualitative Research, 7 (4), 521–550.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Stenhouse, L. (1978). Case study and case records: Towards a contemporary history of education. British Educational Research Journal, 4 (2), 21–39.

Stenhouse, L. (1980). The study of samples and the study of cases. British Educational Research Journal, 6 (1), 1–6.

Thomas, G. (2011). The case: Generalization, theory and phronesis in case study. Oxford Review of Education, 37 (1), 21–35.

Thomas, G. (2012). Changing our landscape of inquiry for a new science of education. Harvard Educational Review, 82 (1), 26–51.

Thomas, G. (2013). How to do your research project—A guide for students in education and applied social science (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Thomas, G. (2016). After the gold rush. Harvard Educational Review , 86 (3) (in press).

Thomas, G., & James, D. (2006). Re-inventing grounded theory: Some questions about theory, ground and discovery. British Educational Research Journal, 32 (6), 767–795.

Thomas, W. I. & Znaniecki, F. (1927/1958) The Polish peasant in Europe and America (2nd ed.). New York: Dover.

U.S. Department of Education. (2004). Toolkit for teachers . Washington, DC: Department of Education.

Vickers, G. (1965). The art of judgment: A study of policy making . London: Chapman and Hall.

Wieviorka, M. (1992). Case studies: History or sociology? In C. C. Ragin & H. S. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Willis, P. (1993) Learning to labour (pp. 62–77). Aldershot: Ashgate (first published by Saxon House, 1978).

Wolcott, H. (1978). The man in the principal’s office . Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Wright, T. (2010). Learning to laugh: A portrait of risk and resilience in early childhood. Harvard Educational Review, 80 (4), 444–463.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Birmingham, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

Gary Thomas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gary Thomas .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Thomas, G. Progress in Social and Educational Inquiry Through Case Study: Generalization or Explanation?. Clin Soc Work J 45 , 253–260 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-016-0597-y

Download citation

Published : 23 July 2016

Issue Date : September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-016-0597-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Explanation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

research@BSPH

The School’s research endeavors aim to improve the public’s health in the U.S. and throughout the world.

- Funding Opportunities and Support

- Faculty Innovation Award Winners

Conducting Research That Addresses Public Health Issues Worldwide

Systematic and rigorous inquiry allows us to discover the fundamental mechanisms and causes of disease and disparities. At our Office of Research ( research@BSPH), we translate that knowledge to develop, evaluate, and disseminate treatment and prevention strategies and inform public health practice. Research along this entire spectrum represents a fundamental mission of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

From laboratories at Baltimore’s Wolfe Street building, to Bangladesh maternity wards in densely packed neighborhoods, to field studies in rural Botswana, Bloomberg School faculty lead research that directly addresses the most critical public health issues worldwide. Research spans from molecules to societies and relies on methodologies as diverse as bench science and epidemiology. That research is translated into impact, from discovering ways to eliminate malaria, increase healthy behavior, reduce the toll of chronic disease, improve the health of mothers and infants, or change the biology of aging.

120+ countries

engaged in research activity by BSPH faculty and teams.

of all federal grants and contracts awarded to schools of public health are awarded to BSPH.

citations on publications where BSPH was listed in the authors' affiliation in 2019-2023.

publications where BSPH was listed in the authors' affiliation in 2019-2023.

Departments

Our 10 departments offer faculty and students the flexibility to focus on a variety of public health disciplines

Centers and Institutes Directory

Our 80+ Centers and Institutes provide a unique combination of breadth and depth, and rich opportunities for collaboration

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversees two IRBs registered with the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections, IRB X and IRB FC, which meet weekly to review human subjects research applications for Bloomberg School faculty and students

Generosity helps our community think outside the traditional boundaries of public health, working across disciplines and industries, to translate research into innovative health interventions and practices

Introducing the research@BSPH Ecosystem

The research@BSPH ecosystem aims to foster an interdependent sense of community among faculty researchers, their research teams, administration, and staff that leverages knowledge and develops shared responses to challenges. The ultimate goal is to work collectively to reduce administrative and bureaucratic barriers related to conducting experiments, recruiting participants, analyzing data, hiring staff, and more, so that faculty can focus on their core academic pursuits.

Research at the Bloomberg School is a team sport.

In order to provide extensive guidance, infrastructure, and support in pursuit of its research mission, research@BSPH employs three core areas: strategy and development, implementation and impact, and integrity and oversight. Our exceptional research teams comprised of faculty, postdoctoral fellows, students, and committed staff are united in our collaborative, collegial, and entrepreneurial approach to problem solving. T he Bloomberg School ensures that our research is accomplished according to the highest ethical standards and complies with all regulatory requirements. In addition to our institutional review board (IRB) which provides oversight for human subjects research, basic science studies employee techniques to ensure the reproducibility of research.

Research@BSPH in the News

Four bloomberg school faculty elected to national academy of medicine.

Considered one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine, NAM membership recognizes outstanding professional achievements and commitment to service.

The Maryland Maternal Health Innovation Program Grant Renewed with Johns Hopkins

Lerner center for public health advocacy announces inaugural sommer klag advocacy impact award winners.

Bloomberg School faculty Nadia Akseer and Cass Crifasi selected winners at Advocacy Impact Awards Pitch Competition

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

The influence of rural tourism landscape perception on tourists’ revisit intentions—a case study in Nangou village, China

- Yuxiao Kou 1 &

- Xiaojie Xue 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 620 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

16 Accesses

1 Altmetric

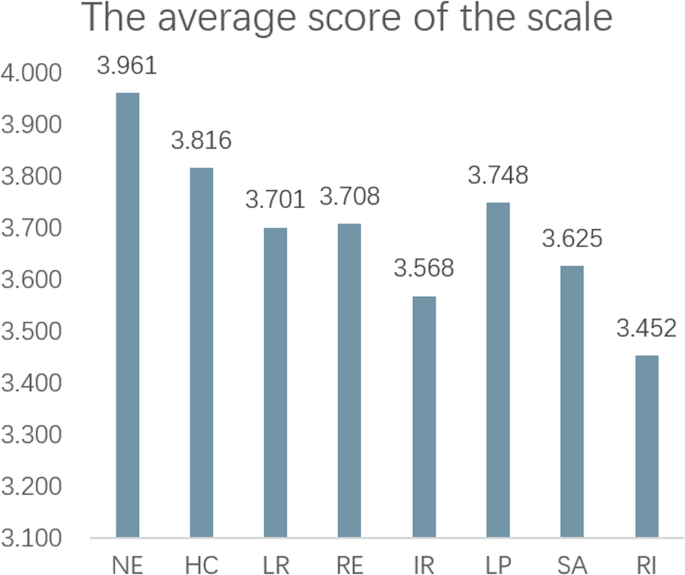

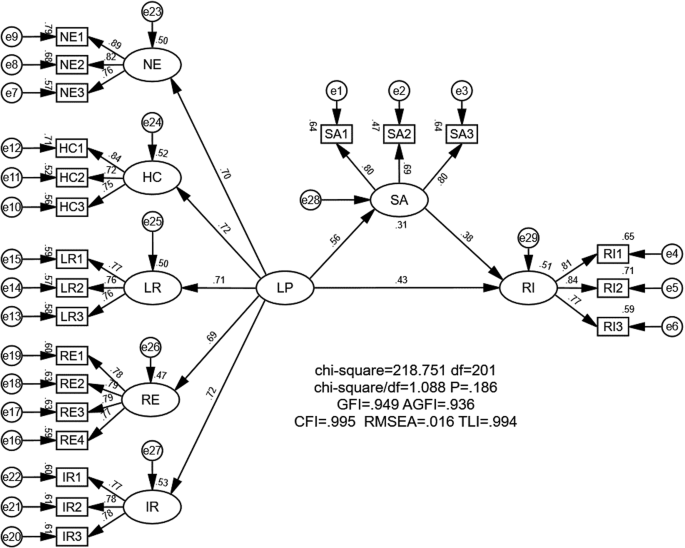

Metrics details

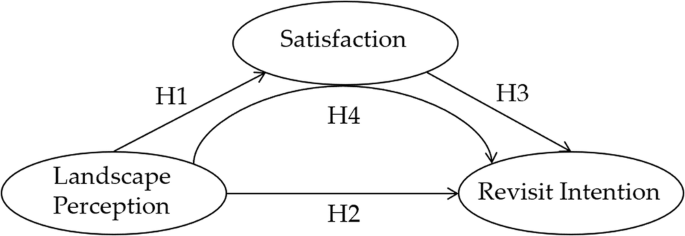

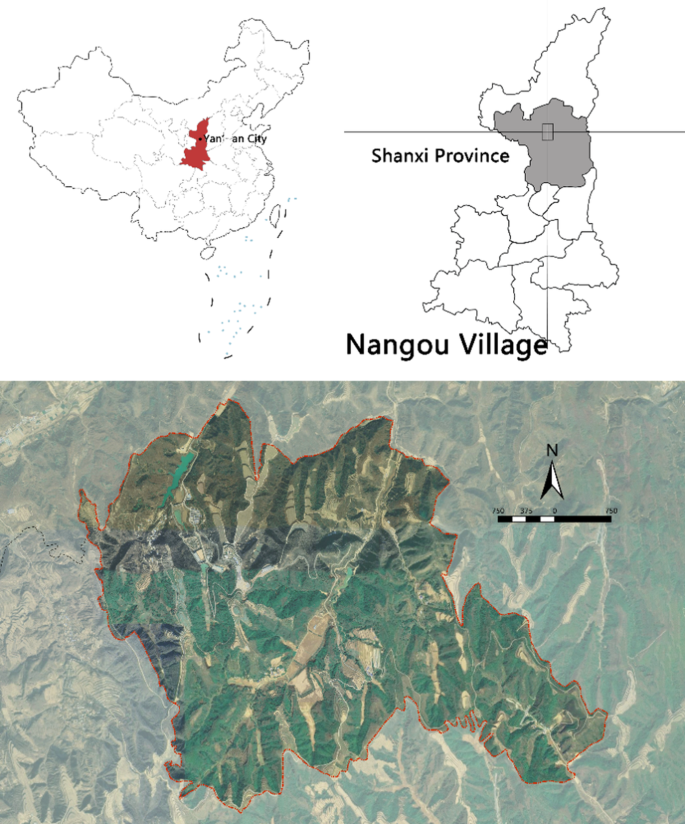

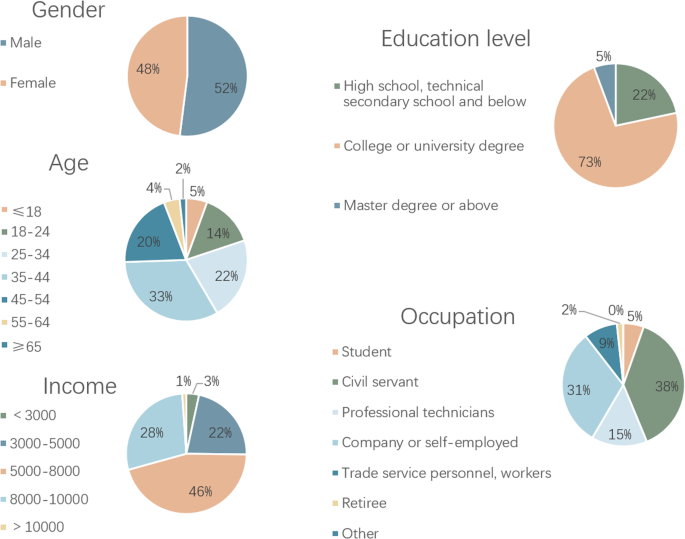

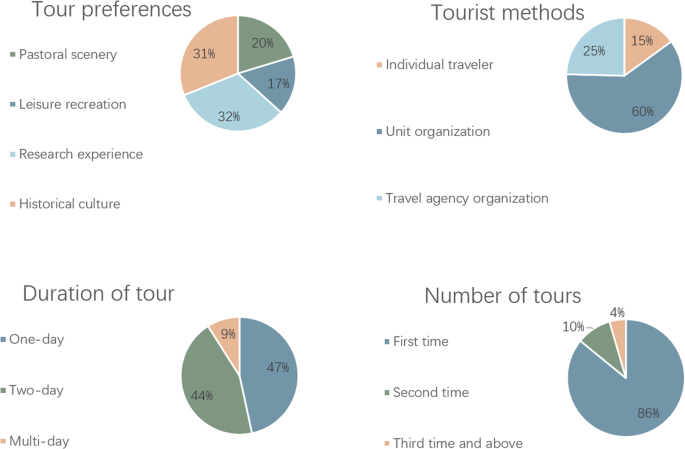

- Environmental studies

Rural tourism development has an important impact on optimizing the rural industrial structure and stimulating local economic growth. China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy has promoted the development of rural tourism nationwide and emphasized Chinese characteristics in the process of local development. Based on the theoretical analysis of landscape perception, this article uses the external Landscape Perception→Satisfaction→Revisit Intention influence path as a theoretical research framework to construct a structural equation model to analyze the willingness of tourists to revisit rural tourism destinations. We selected Nangou Village, Yan’an City, Shaanxi Province, as a key model village for rural revitalization, and conducted an empirical analysis. The empirical analysis results show that landscape perception has a significant positive impact on satisfaction and revisit intention. Tourist satisfaction has a significant positive impact on revisit intention and plays an intermediary role between landscape perception and revisit intention. The five dimensions of natural ecology, historical culture, leisure recreation, research experience, and integral route under landscape perception are all significantly positively correlated with revisit intention, with historical culture and integral route having the greatest impact on landscape perception. The survey about Nangou Village verifies the relationship between landscape perception, satisfaction, and tourists’ revisit intention. Based on the objective data analysis results, this study puts forward suggestions for optimizing Nangou Village’s tourism landscapes and improving tourists’ willingness to revisit from three aspects: deeply excavating rural historical and cultural resources, shaping the national red culture brand, and creating rural tourism boutique routes. It is hoped that the quantitative research method of landscape perception theory in Nangou Village can also provide a reference and inspiration for similar rural tourism planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of ecological presence in virtual reality tourism on enhancing tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior

Evaluating the potential of suburban and rural areas for tourism and recreation, including individual short-term tourism under pandemic conditions

A geographical perspective on the formation of urban nightlife landscape

Introduction.

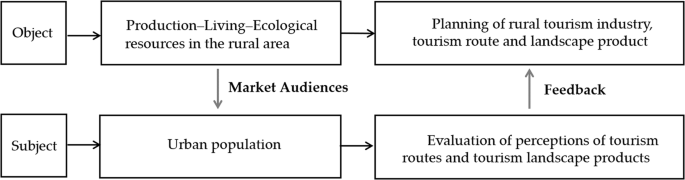

Rural tourism, which originated in Europe in the mid-19th century (He, 2003 ), has constructed a new type of urban–rural relationship—the attachment of the cities to the countryside and the integration of the countryside with the city (Liu, 2018 ). In the 1990s, with the continuous improvement of China’s urbanization level, rural tourism began to rise in response to the demand for returning to nature and simplicity (Guo and Han, 2010 ). The main body of rural tourism (i.e., the main target) is urban residents, and its object is a combination of enjoying the agricultural ecological environment, agricultural production activities, and traditional folk customs. These are presented through tourism industry planning and landscape product design, which is based on the unique production, life, and ecological resources in the countryside, and integrates sightseeing, participation, leisure, vacation, recuperation, entertainment, shopping, and other tourism activities (Zhang, 2006 ).

Rural tourism development is of great significance for optimizing the industrial structure in rural areas, realizing the linked development of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, increasing farmers’ income, stimulating rural economic development, and accelerating the integration of urban and rural areas (Lu et al., 2019 ). Since the implementation of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, China has taken increasing rural tourism as one of the important ways to achieve it (Yin and Li, 2018 ) and has launched construction projects nationwide.