Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Stephen King — Analysis of ‘Why We Crave Horror Movies’ by Stephen King

Analysis of 'Why We Crave Horror Movies' by Stephen King

- Categories: Stephen King

About this sample

Words: 1020 |

Published: Apr 8, 2022

Words: 1020 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Stephen King's essay, "Why We Crave Horror Movies," delves into the intriguing phenomenon of why people are drawn to horror films. King explores the idea that individuals enjoy challenging fear and demonstrate their bravery by willingly subjecting themselves to scary movies. He suggests that humans have an inherent desire to experience fear and that society has built norms around the acceptable ways to do so, with horror movies being one of those sanctioned outlets.

King ultimately argues that horror movies serve as a release valve for the darker aspects of our psyche, allowing us to maintain a sense of normalcy and societal conformity. He suggests that by indulging in controlled madness within the confines of a movie theater, we can better appreciate the positive emotions and values of our everyday lives.

Throughout the essay, King's thoughts evolve from an exploration of psychological impulses to a nuanced consideration of the ethical and moral dimensions of our fascination with horror. He challenges readers to contemplate the complexities of human nature and the role of horror movies in our society.

Works Cited:

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.).

- National Geographic. (n.d.). Why we believe in superstitions. http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/taboo/articles/why-we-believe-in-superstitions/

- New World Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Superstition. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Superstition

- Radford, B. (2016). Superstition: Belief in the age of science. Oxford University Press.

- Rogers, K. (2019). The power of superstition. Scientific American Mind, 30(6), 50-55.

- Sørensen, J. (2014). Superstition in the workplace: A study of a bank in Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(1), 34-42.

- Truzzi, M. (1999). CSIOP Investigates: Superstition and the paranormal. The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice, 1(1), 174-181.

- Vyse, S. A. (2013). Believing in magic: The psychology of superstition. Oxford University Press.

- Woolfolk, R. L. (2018). Educational psychology: Active learning edition (14th ed.). Pearson.

- Yamashita, K., & Ando, J. (2019). Superstition and work motivation: A field study in Japan. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(1), 28-36.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 723 words

3 pages / 1579 words

4 pages / 1725 words

4.5 pages / 1980 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Stephen King

Stephen King is one of the most prolific and successful authors of our time, with over 350 million copies of his books sold worldwide. His writing has influenced countless other authors and has become a staple in the horror and [...]

The name Stephen King is one that needs no introduction, as he is one of the most successful and prolific authors of all time. Born in Maine in 1947, King has been writing professionally since the early 1970s and has published [...]

Stephen King is a prolific writer known for his contributions to the horror genre. One of his most popular short stories, "The Boogeyman," was first published in 1973. This chilling tale has captivated readers for decades and [...]

In Popsy, by Stephen King, irony is used to make a point about human nature. Though this story is unrealistic and somewhat far-fetched, details make it seem realistic until the very end. The story begins with the main [...]

Stephen King wrote one of his most successful novels, Gerald’s Game in 1992. The novel, much like many of his others, quickly became a New York Times #1 Best Seller. The book has recently been adapted into a very popular Netflix [...]

The only motivating factor for a prisoner of Shawshank is hope. For convicted murderers, the hope of getting free by the legal process is all but nonexistent, at least in a time frame that would matter to them. However, despite [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

According to Stephen King, This Is Why We Crave Horror Movies

The horror king breaks down our obsession with the macabre.

Stephen King and horror are synonymous. Are you really able to call yourself a fan of horror if one of his novels or film adaptations isn't among your top favorites? The Maine-born writer is hands down the most successful horror writer and one of the most beloved and prolific writers ever whose legacy spans generations. Without King, we might not be as terrified of clowns and or think twice about bullying the shy girl in school. One could say that King has earned the moniker, "the King of Horror." In addition to all he's written, King has also had over 60 adaptations of his work for television and the big screen and has written, produced, and starred in films and shows as well. He has fully immersed himself in the genre of horror from all sides, and it's unlikely that we will ever have anyone else like Stephen King. But did you know that King wrote an essay that was published in Playboy magazine about horror movies?

In 1981, King's essay titled " Why We Crave Horror Movies " was published in Playboy magazine as a variation of the chapter " The Horror Movie As Junk Food" in Danse Macabre . Danse Macabre was published in 1981 and is one of the non-fiction books in which that wrote about horror in media and how our fears and anxieties have been influencing the horror genre. The full article that was published is no longer online, but there is a shortened four-page version of it that can be found.

RELATED: The Iconic Horror Movie You Won't Believe Premiered at Cannes

Stephen King Believes We Are All Mentally Ill

The essay starts out guns blazing, the first line reading "I think that we're all mentally ill; those of us outside the asylums only hide it a little bit better." From here, he describes the general behaviors of people we know and how mannerisms and irrational fears are not different between the public and those in asylums. He points out that we pay money to sit in a theater and be scared to prove a point that we can and to show that we do not shy away from fear. Some of us, he states, even go watch horror movies for fun, which closes the gap between normalcy and insanity. A patron can go to the movies, and watch someone get mutilated and killed, and it's considered normal, everyday behavior. This, as a horror lover, feels very targeted. I absolutely watch horror movies for fun and I will do so with my bucket of heart-attack-buttered popcorn and sip on my Coke Zero. The most insane thing about all of that? The massive debt accumulated from one simple movie date.

Watching Horror Movies Allows Us to Release Our Insanity

King states that we use horror movies as a catharsis to act out our nightmares and the worst parts of us. Getting to watch the insanity and depravity on the movie screen allows us to release our inner insanity, which in turn, keeps us sane. He writes that watching horror movies allows us to let our emotions have little to no rein at all, and that is something that we don't always get to do in everyday life. Society has a set of parameters that we must follow with regard to expressing ourselves to maintain the air of normalcy and not be seen as a weirdo. When watching horror movies, we see incredibly visceral reactions in the most extreme of situations. This can cause the viewer to reflect on how they would react or respond to being in the same type of situation. Do we identify more with the victim or the villain? This poses an interesting thought for horror lovers because sometimes the villain is justified. Are we wrong for empathizing with them instead?

Let's take a look at one of the more popular horror movies of recent years. Mandy is about a woman who is murdered by a crazed cult because she is the object of the leader's obsession. This causes Red ( Nicolas Cage ) to ride off seeking revenge for the love of his life being murdered. There are also movies like I Spit On Your Grave and The Last House On The Left where the protagonist becomes the murderer in these instances because of the trauma they experienced from sexual assault. Their revenge makes audiences a little more willing to side with the murderer because they took back their power and those they killed got what was deserved. This is where that Lucille Bluth meme that says "good for her" is used. I'll die on the hill that those characters were justified and if that makes me mentally ill then King might be right!

What Does Stephen King Mean When He Tells Us to "Keep the Gators" Fed?

At the end of the essay, King mentions he likes to watch the most extreme horror movies because it releases a trap door where he can feed the alligators. The alligators he is referring to are a metaphor for the worst in all humans and the morbid fantasies that lie within each of us. The essay concludes with "It was Lennon and McCartney who said that all you need is love, and I would agree with that. As long as you keep the gators fed." From this, we can deduce that King feels we all have the ability to be institutionalized, but those of us that watch horror movies are less likely because the sick fantasies can be released from our brains.

With that release, we can walk down the street normally without the bat of an eye from walkers-by. Perhaps this is why the premise for movies like The Purge came to fruition. A movie where for 24 hours all crime, including murder, is decriminalized couldn't have been made by someone who doesn't get road rage or scream into the void. It was absolutely made by someone who waited at the DMV for too long or has had experience working in retail around Black Friday. With what King is saying, The Purge is a direct reflection of that catharsis. Not only are you getting to watch a crazy horror movie where everyone is shooting everyone and everything is on fire, but it's likely something you've had a thought or two about. You can consider those gators fed for sure.

Do Horror Movies Offer Us True Catharsis or Persuasive Perspective?

Catharsis as a concept was coined by the philosopher Aristotle . He explained that the performing arts are a way to purge negative types of emotions from our subconscious, so we don't have to hold onto them anymore. This viewpoint further perpetuates what King is trying to explain. With that cathartic relief, the urgency to act on negative emotion is less likely to happen because there is no build-up of negativity circling the drain from our subconscious to our reality. However, some who read the essay felt like King was just being persuasive and using fancy imagery rather than identifying an actual reason why horror is popular. Some claim the shock and awe factor of his words and his influence on horror would cause some readers to believe they are mentally ill deep down. I have to say, as a millennial who rummages through the ends of social media multiple times a day, everyone on the internet thinks they're mentally ill, and we all have the memes to prove it. It is exciting and fascinating to watch a horror movie after working a 9-5 job where the excitement is low. Watching Ghostface stalk Sidney Prescott ( Neve Campbell ) in Scream isn't everyone's idea of winding down, but for the last 20-something years, it has been my comfort movie when I'm feeling sad or down. The nostalgia of Scream is what makes it feel cathartic to me and that's free therapy!

What is the Science Behind Loving Horror Movies?

Psychology studies will tell us that individuals who crave and love horror are interested in it because they have a higher sensation-seeking trait . This means they have a higher penchant for wanting to experience thrilling and exciting situations. Those with a lower level of empathy are also more likely to enjoy horror movies as they will have a less innate response to a traumatic scene on screen. According to the DSM-V , a severe lack of empathy could potentially be a sign of a more serious psychological issue, however, the degree of severity will vary. I do love rollercoasters, but I also cry when I see a dog that is just too cute, so horror lovers aren't necessarily the unsympathetic robots that studies want us to be. Watching horror films can also trigger a fight-or-flight sensation , which will boost adrenaline and release endorphins and dopamine in the brain. Those chemicals being released make the viewers feel accomplished and positive, relating back to the idea that watching horror movies is cathartic for viewers.

Anyone who reads and studies research knows that correlation does not imply causation, but whether King's perspective is influenced by his position in the horror genre or not, psychology and science can back up the real reasons why audiences love horror movies. As a longtime horror lover and a pretty above-average horror trivia nerd, I have to wonder if saying we are mentally ill is an overstatement and could maybe be identified more as horror lovers seeking extreme stimulus. Granted, this essay was written over 40 years ago, so back then liking horror wasn't as widely accepted as it is today. It's possible that King felt more out of place for his horror love back then and the alienation of a fringe niche made him feel mentally ill. Is King onto something by assuming that everyone has mental illness deep down, or is this a gross overestimation of the human psyche? The answer likely falls somewhere in between, but those that love horror will continue to release that catharsis through the terrifying and the unknown because it's a scream, baby!

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Stephen King has spent half a century scaring us, but his legacy is so much more than horror

It’s a big year for King adaptations, but the movies only tell part of the story.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Stephen King has spent half a century scaring us, but his legacy is so much more than horror

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56041405/Screen_Shot_2017_05_08_at_11.17.56_AM.0.png)

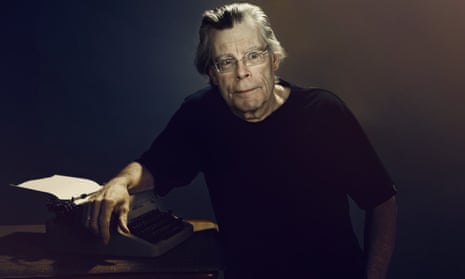

It’s nearly impossible to overstate how influential Stephen King is. For the past four decades, no single writer has dominated the landscape of genre writing like him. To date, he is the only author in history to have had more than 30 books become No. 1 best-sellers. He now has more than 70 published books, many of which have become cultural icons, and his achievements extend so far beyond a single genre at this point that it’s impossible to limit him to one — even though, as the world was reminded last year when the feature film adaptation of It became the highest-grossing horror movie on record, horror is still King’s calling card.

In fact, we’ve been enjoying a cultural resurgence of quality King horror adaptations lately, from small-screen adaptations like Gerald’s Game and Castle Rock to the upcoming remake of Pet Sematary , the first trailer for which looks like a promising continuation of the trend.

That means if you’re a King fan — or looking to become one — there’s no better time to rediscover why he’s such a beloved cultural phenomenon.

After all, without King, we wouldn’t have modern works like Stranger Things , whose adolescent ensemble directly channels the Losers’ Club, King’s ensemble of geeky preteen friends from It . Without The Shining , and Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece film adaptation, “Here’s Johnny!” would be a dead talk show catchphrase and parodies like the Simpsons’ annual Treehouse of Horror would be bereft of much of their material.

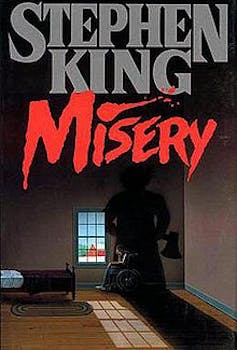

Without Carrie , we wouldn’t have the single defining image of the horror of high school: a vat of pig’s blood being dropped on an unsuspecting prom queen. Without King, we wouldn’t have one of the most iconic and recognizable images in cinema history — Andy Dufresne standing in the rain after escaping from Shawshank prison — nor would we have the enduring horror of Pennywise the Clown, Cujo the slavering St. Bernard, or Kathy Bates’s pitch-perfect stalker fan in Misery .

This is but a sampling born from a staggeringly prolific writing career that’s well on its way to spanning five decades. King has effectively been translating America’s private, communal, and cultural fears and serving them up to us on grisly platters for half a century.

King might have remained a struggling English teacher, but for two women: Tabitha King and Carrie White

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8979365/carrie_prom_shot_1050_591_81_s_c1.jpg)

Born in 1947, King grew up poor in Durham, Maine, the younger son of a single working mother whose husband, a merchant mariner, abandoned his family when King was still a toddler. A lifelong fan of speculative fiction, King began writing seriously while attending the University of Maine Orono. It was there, in 1969, that he met his wife, Tabitha.

By 1973, King was a high school English teacher drawing a meager $6,400 a year. He had married Tabitha in 1971, and the pair lived in a trailer in Hampden, Maine, and each worked additional jobs to make ends meet. King wrote numerous short stories, some of which were published by Playboy and other men’s magazines, but significant writerly success eluded him.

Tabitha, who’d been one of the first to read Stephen’s short stories in colleges, had loaned Stephen her own typewriter and refused to let him take a higher-paying job that would mean less time to write. Tabitha was also the one who discovered draft pages of what would become Carrie tossed in Stephen’s trash can. She retrieved them and ordered him to keep working on the idea. Ever since, King has continued to pay Tabitha’s encouragement forward. He frequently and effusively blurbs books from established as well as new authors, citing a clear wish to leave publishing better than he found it. Meanwhile, Tabitha is a respected author in her own right , as are both of their sons, Joe Hill and Owen King.

Carrie, which King sold for a $2,500 advance, would go on to earn $400,000 for the rights to its paperback run. The story of a troubled girl who develops powers of telekinesis, Carrie is the ultimate “high school is hell” morality tale. Carrie faces ruthless abuse from her religious mother and bullying from high school classmates, and the book introduces us to two of King’s most prominent themes: small Maine towns with dark underbellies, and main characters written with care and empathy despite being deeply flawed and morally gray — in this case Carrie, her mother, and her bully Sue. The complicated bond between protagonist and antagonist is also a recurring motif in King’s writing.

Two years after Carrie ’s publication, Brian De Palma’s 1976 film adaptation grossed $33 million on a $1.8 million budget, largely on the strength of advance critical praise and word-of-mouth reviews. Buoyed by the subsequent success of Carrie ’s paperback sales, King would go on to churn out six novels ( Salem’s Lot, The Shining, Rage, The Stand, The Long Walk, and The Dead Zone ) over the next six years, establishing a prolificacy that would continue through much of his career.

“The movie made the book and the book made me,” King told the New York Times in 1979.

By 1980 , King was the world’s best-selling author.

It’s taken decades for King’s work to be critically appreciated — in particular for its literary qualities

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8979047/the_shawshank_redemption_accounted_for_a_huge_amount_of_cable_air_time_in_2013.jpg)

King’s work has appeared in magazines ranging from the New Yorker to Harper’s to Playboy. The author has influenced literary writers like Haruki Murakami and Sherman Alexie along with genre creators like the producers of Lost . And he’s won virtually every major horror, mystery, science fiction, and fantasy award there is. But King also spent decades being written off by both the horror writing community and the literary mainstream.

King once referred to critics perceiving him to be “a rich hack,” a perception that bears out in horror writer David Schow’s offhand 1997 description of him as “comparable to McDonald’s” — intended to characterize King as horror’s pedestrian mainstream. When a 1994 King short story , his first to be published in the New Yorker, won the prestigious O. Henry Award, Publishers Weekly declared it to be “one of the weaker stories in this year’s [O. Henry Award] collection.”

“The price he pays for being Stephen King is not being taken seriously,” one of King’s collaborators told the LA Times in 1995.

The critical disparagement of King often went hand in hand with genre shaming. In a 1997 60 Minutes interview , Lesley Stahl questioned King’s literary tastes, getting him to admit that he’d never read Jane Austen and had only read one Tolstoy novel. In response, King grinned that he had, instead, read every novel Dean Koontz had ever written — Dean Koontz being a notoriously lowbrow writer of thrillers. (That same year, the New York Times would compliment the breadth of King’s literary knowledge even while panning his epic best-seller The Stand. )

“Here you are, one of the best- selling authors in all of history,” Stahl continued, “and the critics cannot find much that they like in your work.”

To this, King replied, “All I can say is — and this is in response to the critics who've often said that my work is awkward and sometimes a little bit painful — I know it. I'm doing the best I can with what I've got.”

While King’s self-deprecation may have been a mark of respect for his critics, those critics were on the cusp of being proven wrong. This was in large part thanks to the sleeping giant that became The Shawshank Redemption, which drew popular attention to the fact that King could do more than “just” write horror, and helped kick-start critical reassessment of him and his work.

The film, written by longtime Stephen King adapter Frank Darabont, is based on one of King’s most literary works, a 1982 novella about an agonizingly slow prison break. Shawshank flopped when it opened in theaters in 1994, but it was nominated for seven Academy Awards — more than any other King adaptation. As indicated by its long reign as the highest-ranked film on IMDB , it has gone on to become one of the most popular and beloved films ever made.

By 1998, under the oversight of a new publisher, King’s books were actively being marketed as literary fiction for the first time. From the mid-’90s through today, King’s critical and cultural reputation has advanced as thoroughly as it stagnated before.

In a 2013 CBS interview , we see the marked difference with which contemporary media has come to view King’s work: “You used to always get slotted in the Horror genre,” interviewer Anthony Mason commented to King. “And I think it was sort of a way of some people, I think, not treating you all that seriously as a writer.”

“I don't know if I want to be treated seriously per se, because in the end posterity decides whether it's good work or whether it's lasting work,” King replied, secure in his position as one of the best-loved authors of the 20th century.

But evolving cultural views on genre fiction aside, King’s writing has always displayed significant literary qualities, particularly ongoing literary themes that have shaped how we understand horror as well as ourselves.

The horror of Stephen King doesn’t lie with the external but with the internal

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8988277/183072_full.jpg)

In his award-winning 1981 collection of essays on horror, Danse Macabre , King names three emotions that belong to the realm of the horror genre: terror, horror, and revulsion. He argues that while all three emotions are of equal value to the creation of horror, the “finest” and most worthy is terror because it rests on the creator’s ability to command audiences’ imaginations. Drawing on numerous writers before him, he posits that never fully revealing the source of the horror is the best way to effect terror upon the mind.

King argues that the art of making us terrified about what lies around the corner is all about getting us to identify with the characters who are experiencing the terror. If we don’t care about the characters, then it won’t matter how many jump scares you fling at the audience — we have to be at least a little invested in their fate.

As such, King spends a great deal of time on characters’ interior lives, often jumping between different point-of-view characters throughout his novels. (For example, Salem’s Lot , It , and The Stand are all stories with large ensemble casts and multiple shifting points of view.) But every characterization, even a minor one, is rich with detail; even if you just met a new character, you can bet that by the time he or she meets a grisly ending a few pages later, you’ll have a deep understanding of who that character is.

King’s novels often contain deeply flawed yet sympathetic central characters surrounded by large ensemble casts full of equally flawed people, each struggling to interact and grapple with larger forces. By framing his stories within an interwoven web of narrative perspectives and juxtaposed character experiences, King is able to generate a feeling of interconnectivity, as well as explore the various literary themes that stretch throughout his multidimensional universe, including but not limited to:

1) Nerdboys to men

King credits his absentee father for bequeathing him a love of horror via a stash of pulp novels King discovered as a boy. But another lasting legacy of this truncated relationship was King’s ongoing preoccupation with relationships between men and boys, the process of attaining manhood, and the bridge between boyhood and adulthood.

We see these bonds take a variety of shapes and meaning throughout his work, ranging from comforting ( Salem’s Lot ) to destructive ( Apt Pupil ) to ambiguous ( The Shining ). King explores male intimacy through these relationships, frequently challenging typical masculine forms of expression. He can do this because his boys and men tend to be nerds and outcasts who already exist outside traditional masculine norms. The bookish nerdy kid was relatively uncommon in mainstream adult fiction before King came along; now we recognize such characters as hallmarks of genre literature.

To King, the social markers that make kids outcasts in school — from being nerdy to being overweight to enduring acne — also make them uniquely outfitted to be conduits for readers’ social anxieties and fears. Because deep down, we’re all reliving the social terrors of school every day of our lives.

2) Creative struggles and struggles with addiction

King frequently writes about the process of creation, often by exploring an artist who’s been prevented from creating in some way. The main characters of Salem’s Lot, The Shining, Misery, The Dark Half, Bag of Bones , 1408, and numerous short stories are all writers who’ve been in some way prevented from writing or thwarted in their creative efforts. Many of these and other artistic characters mirror King’s own real-life experiences; for example, the artist at the center of 2008’s Duma Key reflects his physical struggle to write following a highly publicized 1999 injury that made writing difficult for several years.

King has also been open throughout his career about his struggles with addictions ranging from alcohol to drug abuse to painkillers, and many of his main characters likewise struggle with addiction — either directly, in books like The Shining and Revival , or indirectly: The villain of Misery , Annie Wilkes, is a metaphor for cocaine itself.

3) World building through geography and repeated characters

Most people associate Stephen King with Maine and Maine with Stephen King. This is because King almost exclusively writes and sets his stories there. The town of Derry, for example, where It lives, is based on Bangor, Maine. Numerous fictional King towns, like Derry, Haven (the location of a 2010 TV series based on King’s mystery novel The Colorado Kid ), and Castle Rock, exist in his works alongside real towns.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8976681/Screen_Shot_2017_08_01_at_10.48.04_PM.png)

King uses these locations to increase the verisimilitude of his stories, painting them as all part of the same fictional universe. In stories like It , he borrows liberally from real places and landmarks, highways and scenery, even real street corners. And while Derry is the most famous of King’s fictional towns, Castle Rock is his most frequent destination, showing up over and over in his works.

King doesn’t only reuse places in his stories, however — he also reuses people. One popular villain, a recurring supernatural figure who may or may not be the devil, appears throughout the Stephen King universe in various guises. In T he Dark Tower he’s “the Man in Black”; to the lost souls in The Stand , he’s a leader named Randall Flagg. In other stories, he’s a nebulous cast of characters with the initials “R.F.”

Frequently throughout his books, King will signal that his worlds are all connected by having characters meet characters from other books in passing. King characters also are frequently able to travel between narrative landscapes, with or without their awareness ( The Shining, Gerald’s Game, Bag of Bones, Lisey’s Story ). This interconnectivity becomes the central conceit of the Dark Tower , which explicitly links most of King’s stories together in one vast multiverse and explains that there are metaphysical doors between the worlds that allow all this to happen.

King’s work endures not because of its inherent darkness but because of its inherent hope

Part of the reason it may have taken critics so long to reassess King’s work is that “horror” implies the lower rungs of emotion King speaks of in Danse Macabre — the gross-outs and the physical gags that play into our understanding of the genre. But the key to his popularity as a horror novelist, and as a novelist in general, resides not in the darkest moments of his writing, but in his basic belief in humanity’s innate goodness.

He spells out his essentially hopeful, fundamentally romantic worldview in a 1989 interview :

There must be a huge store of good will in the human race. ... If there weren’t this huge store of good will we would have blown ourselves to hell ten years after World War II was over. ... It’s such a common thing, those feelings of love toward your fellow man, that we hardly ever talk about it; we concentrate on the other things. It’s just there; it’s all around us, so I guess we take it for granted ... I believe all those sappy, romantic things: Children are good, good wins out over evil, it is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. I see a lot of the so-called “romantic ideal” at work in the world around us.

It’s this core optimism, more than his ability to scare us, that makes King so beloved by readers. Even in his bleakest works, he retains his ability to empathize deeply with his characters, and to see even his monsters as fundamentally human.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

The controversy over Harrison Butker’s misogynistic commencement speech, explained

Raw milk is more dangerous than ever. So why are sales surging?

Teletherapy can really help, and really hurt

The Supreme Court decides not to trigger a second Great Depression

Inside the bombshell scandal that prompted two Miss USAs to step down

What young voters actually care about

Why We Crave Horror Movies

27 pages • 54 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Analysis: “Why We Crave Horror Movies”

The essay “Why We Crave Horror Movies” interweaves point of view , structure, and tone to address the foundational themes of fear, emotions, and “insanity” in relation to horror movies. It examines why horror films allow the expression of fearful emotions linked to irrationality. The essay integrates literary techniques and pop culture references to form a cohesive whole, and it highlights several key themes: Good Versus Bad Emotions , The Expression of Fear Through Horror Movies , and “Insanity” and Normality in Society and Horror Film .

King argues that fear and other negative emotions are universal and that horror movies are a key art form for expressing these emotions. The essay gives audiences permission to experience and enjoy these films as a vehicle for fears.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,650+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Stephen King

Stephen King

Bag of Bones

Billy Summers

Children of the Corn

Different Seasons

Doctor Sleep

Dolores Claiborne

Elevation: A Novel

End of Watch

Finders Keepers

Firestarter

From a Buick 8

Full Dark, No Stars

Gerald's Game

Gwendy's Button Box

Stephen King, Richard Chizmar

Featured Collections

Books About Art

View Collection

Good & Evil

What makes Stephen King horror books and movies so scary

Following is a transcript of the video .

"The terror, which would not end for another twenty-eight years--if it ever did end-- began, so far as I know or can tell, with a boat made from a sheet of newspapers floating down a gutter swollen with rain." This is how Stephen King begins "It," his 22nd novel, published in 1986. It's a passage that really exemplifies what King does best: instantly engrossing you in the horrific and unknown. And it's this unique ability that has made him one of the best-selling writers of our time, selling over 350 million copies worldwide and earning him the distinguished title of Master of Horror.

Yet, despite his success and popularity, King is still a difficult writer to discuss among the literary circle. Once described by The New York Times as "a writer of fairly engaging and preposterous claptrap," there has been a long-standing discussion on whether King's works are really literature or just glorified pulp. Nonetheless, King has managed to create some of the most iconic and haunting stories ever to come out of the genre. Which raises the question: How does he do it?

Like any writer, King isn't shy to share his sources of inspiration, most notably writers like Richard Matheson of "I Am Legend" and Bram Stoker of the now classic "Dracula." But perhaps the writer that most closely resembles his style is H.P. Lovecraft, one of the most influential writers of the horror genre. He single-handedly created a whole new subgenre that is now more commonly known as cosmic horror, in which unknown cosmic entities and phenomena beyond our understanding, often portrayed as ancient, mythical monsters, became the subject of horror. But the monsters of Lovecraft were never really monsters.

Instead, they were metaphors that symbolized Lovecraft's deep fear of the rapid technological and scientific advancements in the early 20th century. The helplessness he felt towards the changes around him reflected in the hopeless struggle of people against forces that are far beyond their control. Lovecraft believed that people's inability to truly understand their reality was the most merciful thing in the world and that doing so would be enough to drive anyone to insanity.

In many ways, this is the same kind of horror that King taps into. Whether it's vampires, a haunted hotel, or a rabid dog, the subjects of King's horror all represent our fear for something else. More specifically, the societal fears of the American people. In "Danse Macabre," King's study of the horror genre, he explains that there are two different kinds of horror.

The first is horror that plays on our phobic pressure points. These are fears based on our individual phobias, like the fear of spiders or ghosts, something that a lot of recent horror movies have based themselves on. But these horrors also have a clear limit, as they target a very specific group of people with that specific phobia. Which is why more effective and successful works of horror play with what's known as national pressure points. These are political, societal, and psychological fears that are shared by a wider spectrum of people. Like in the works of Lovecraft and King, are represented by the abnormal and the supernatural. It's what King excels at, living through some of the most tumultuous periods in American history.

His debut novel, "Carrie," on the surface a book about a girl with telekinetic powers, is really a story about the suppression of female sexuality in the '60s, published just six years after the famous Miss America protest in 1968. And in "The Shining," a book about a family stranded in a haunted hotel, King picks apart the concept of patriarchy that is deeply rooted into the American culture to discuss the cyclical nature of parental legacy. Sometimes it's more personal.

Two of his most famous works, "Misery" and "Cujo," deal with addiction and the lack of self-control it accompanies and were written by King during his own struggle with drugs and alcohol. Like Lovecraft, the horrors that King portrays are self-reflective and grounded in our reality. Which in turn makes the horror feel that much more real. They're representations of American fear. Things that threaten the very foundation of the society we live in. And just like Lovecraft, it's reality that terrifies King. As he once put it, it isn't the physical or mental abnormalities that really horrify us, but the lack of order in our reality they represent.

So, how does King put this on paper? The first thing to note is that situation comes first. King's books are often based on situations rather than intricate plots. Every single one of his works is based on a series of what-if scenarios. Like what if an ancient, cosmic evil in the shape of a clown terrorized a small town in Maine? Then he drops a group of well-fleshed-out characters right into the heart of the situation. But it's not to help them work their way free, but to simply watch what happens. And it's this spontaneity that allows for some of the most unexpected and shocking moments in King's stories. And it's impossible to talk about Stephen King without talking about suspense.

Another master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, once said suspense is "the most powerful means of holding on to the viewer's attention." And it's what King also excels at. Grabbing your attention and keeping it on something horrific, so you're unable to turn away. And he accomplishes this by applying three of the most basic literary devices. The first step is foreshadowing. Both his books and adaptations are riddled with lines and moments that hint at what's to come. This is why King's stories have an overarching sense of doom and dread.

Unlike most horror novels and films, it's not the uncertainty of danger that has you on edge, but exactly when that danger will finally happen. Then, the next step is callback, where King racks up the suspense by continuously reminding the audience that the danger is lurking. And oftentimes, it takes a while for the danger to actually show its face. And then, finally, the payoff. In which the suspense we've been building towards reaches its peak and we finally face the danger we've been waiting for. And it's at this final moment that King scares us. And you can very well see this throughout King's career. Even in the passage that started this video. With just one line, foreshadowing the terror to come, a callback to the longevity of said terror, and, finally, the payoff to the very thing that started it all.

Analyzing the works of Stephen King is a great opportunity to understand what really scares us at the end of the day. His works are prime examples that show us that our object of fear very much exists in our own reality. Sometimes it's not the monsters or ghosts that scare us, but the horrors of everyday life lurking in the corners, waiting to strike. And it's this horror that King knows and understands perhaps better than anyone. And if that's not enough to make him the Master of Horror, it would be hard to find someone else that deserves it more.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This video was originally published in September 2019.

More from Entertainment

- Main content

- General Hospital

- Celebrities

- Days of Our Lives

- Young and The Restless

- The Bold and the Beautiful

- Movie Lists

- The Walking Dead

- Whatever Happened To

- Supernatural

- Grey's Anatomy

- The Big Bang Theory

- American Horror Story

- The Mandalorian

- Agents of SHIELD

A Summary of Stephen King’s Essay “Why We Crave Horror Movies”

A while back, renowned author Stephen King wrote an essay that appeared in a leading magazine entitled “Why We Crave Horror Movies.” In that essay, he tried to explain why people enjoy watching scary movies so much more than virtually any other type of movie out there. The idea he came up with was one that actually surprised a lot of people, and it certainly made them stop and think about how they interact with their own little corner of the world for a minute.

In this essay, King made it very clear that in his opinion, the reason that people enjoy watching horror movies is because no one is completely sane. He even went as far as to say that mental illness is something that every person has in common, only some people are able to hide it somewhat better than others. That’s right, King very clearly connected people who live what most individuals consider a relatively normal life with those who are living inside insane asylums, stating that the only difference is that one group of people was capable of hiding their insanity better than the other.

He goes on to say that the reason horror films are so popular is because it is a relatively safe way of feeding that insanity. People enjoy watching the gore, feeling that rush of adrenaline that comes when watching something in this particular genre, and perhaps even watching other people carry out things on the screen that they would never actually do in real life, even if they have thought about it a time or two.

The interesting thing is that many people have said that they think Stephen King is both a genius and crazy, all at the same time. Many individuals say they would never want to spend the night alone in a house with him, because if he is able to have that kind of stuff going through his head, they wouldn’t feel very comfortable in his presence without other people around. According to King, he’s merely writing what everyone else thinks about at one time or another.

Is this really true? There certainly were a large number of responses to this essay. Some people were outraged that he would even make such a statement and others actually agreed with him. For the most part, it made the average everyday citizen stop and take a long, hard look at themselves. For anyone that does enjoy horror films to the point of seeking out virtually every one that’s ever been made in order to get that adrenaline rush, the question becomes even more pressing. Why is it so interesting to watch something when you know something bad is going to happen? Why does it seem so appealing to watch something filled with a tremendous amount of gore, questionable subject lines, and boundaries that sometimes shouldn’t be crossed? If you’re the person that sits and watches these movies, do you really have any right to criticize the people who wrote them? After all, no one is holding a gun to your head and forcing you to watch it.

This was ultimately the point that King was making. Everyone has free will. For anyone that flocks to these types of movies, they just might be a little bit crazy, at least as much as whoever wrote them in the first place.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Aiden Mason

Aiden's been an entertainment freelancer for over 10 years covering movies, television and the occasional comic or video game beat. If it's anything Shawshank Redemption, Seinfeld, or Kevin Bacon game related he's way more interested.

Exploring Stephen King: Why We Crave Horror Movies

Stephen King is a prolific writer famous for his horror novels, including “Carrie,” “The Shining,” and “IT.” However, his insights extend beyond the realm of fiction and delve into the psychology and societal influences behind our fascination with horror movies. In this long-form article, we will explore King’s perspective on why we crave horror movies and how they provide a myriad of psychological and emotional reactions.

Key Takeaways

- Stephen King highlights the psychological thrill of fear in horror movies.

- Horror movies provide catharsis and release of pent-up emotions and anxieties.

- They offer a means of escaping the mundane aspects of everyday life and provide a platform to confront societal taboos in a safe environment.

- Horror movies cater to the human desire to explore the mysteries of the world’s unknown .

- They push our sensory boundaries and stimulate our creative thinking by immersing us in terrifying scenarios that evoke intense emotions.

The Psychological Thrill of Fear

As Stephen King suggests, one of the reasons why we are drawn to horror movies is the psychological thrill they provide through fear . Our brain is wired to respond to danger, creating an adrenaline rush that heightens our senses and emotions. Horror movies tap into our primal instincts, triggering the fight or flight response and providing a thrilling experience that is both terrifying and exhilarating.

The experience of fear in a controlled environment can be cathartic, allowing us to confront our deepest fears and experience a sense of release . This complex, multi-layered experience is what makes horror movies so appealing to audiences across generations.

Catharsis and Release

Stephen King contends that one of the reasons there is such an appeal for horror movies is the concept of catharsis . Catharsis is the purging of negative emotions by bringing them to the surface and realizing them. When we experience horror movies, we’re taken on a journey that allows us to express emotion and safely confront our fears, providing a sense of release and resolution. The adrenaline rush , accompanied by excitement and fear that one feels during the anxiety-inducing scenes, creates an outlet for our frustrations and anxieties, hence making it an enjoyable experience.

“It follows then that the genre is important because it offers an emotional and intellectual release – it allows healthy, if temporary, connections with the darkest parts of ourselves and the world around us.” – Darren Mooney

During and after the movie, the sense of fear melts away, making us feel calm and relieved. The viewer is relieved of their anxiety and pent-up emotions, which is why people have been craving horror movies for generations. The genre promises relief and provides the viewer with an opportunity to confront and overcome their personal demons in an exhilarating way, with a sense of satisfaction and contentment after the experience.

Escaping Routine and Taboos

In a world filled with monotony and repetition, it’s no surprise that people crave a little excitement and stimulation. Stephen King suggests that one of the reasons why we enjoy horror movies so much is that they offer a means of escaping routine and providing a fresh perspective on life.

“We’re always looking for something that’s just around the corner, and just out of sight. … The real horror is what’s behind us, what we’ve already done.”

By confronting our deepest fears and anxieties, horror movies provide a cathartic release and allow us to confront societal taboos in a safe environment. The genre often deals with issues that are considered taboo or controversial, such as violence, death, and sexuality, and allows us to explore these themes without judgment or shame.

Through horror movies, we can explore the dark and mysterious corners of the world with a sense of adventure and excitement, without having to put ourselves in real danger. This is why horror movies continue to be a beloved genre that captures the imagination and curiosity of audiences worldwide.

The Allure of the Unknown

As human beings, we are inherently drawn to the mystery of the unknown . It’s the curiosity that drives us to explore the world around us, and the desire to uncover secrets that are waiting to be revealed. Stephen King understands this allure and knows that we crave the unexplored and undiscovered.

Horror movies cater to this innate desire by taking us on a journey to the unknown , and immersing us in terrifying and suspenseful situations that keep us on the edge of our seats. The unknown can be both thrilling and terrifying, and horror movies leverage this duality to create a unique and captivating experience.

Whether it’s the eerie shadows in a haunted house, the unexplained noises in the dark, or the unsettling presence lurking just out of sight, horror movies tap into our primal instincts and evoke powerful emotions. They challenge our senses and imagination, and offer a glimpse into the unknown that is simultaneously terrifying and alluring.

“The unknown is the most alluring part of life. It’s the reason we have science, exploration, and art.” – Stephen King

Challenging Our Senses

Stephen King’s horror movies are known for their ability to push the boundaries of our sensory experiences. By incorporating vivid visuals, spine-tingling sound effects, and suspenseful storytelling, King creates a heightened atmosphere that challenges our senses and immerses us in the terrifying world he has created.

Horror movies often rely on jump scares and sudden bursts of action to trigger our fight or flight response, leading to a rush of adrenaline and a heightened awareness of our surroundings. The physiological reaction to horror movies includes increased heart rate and breathing, which in turn increases the release of endorphins that induce a sense of euphoria.

“The idea that horror is the only genre that consistently challenges the audience’s senses is very true. Horror films are intended to frighten and unsettle us, which they do by playing on a variety of our emotional and sensory responses.” – Stephen King

King’s attention to detail in creating a one-of-a-kind sensory experience has been recognized by critics and audiences alike. By tapping into our primal instincts and pushing our sensory boundaries, he has created horror movies that stay with us long after the credits roll.

The Power of Imagination

Stephen King believes that horror movies have a unique ability to stimulate our imagination. When we watch these films, we transport ourselves to terrifying scenarios that evoke intense emotions and stimulate our creative thinking. The power of imagination is immense, and horror movies utilize this to create memorable experiences that linger long after the credits have rolled.

King argues that, through horror movies, we can confront our deepest fears and anxieties and tap into our primal instincts. By doing so, we expand our imaginative capacity, broaden our understanding of the world, and explore the unknown. Horror movies allow us to push the limits of our imagination and face the unthinkable, all while remaining in a safe and controlled environment.

The Benefits of Stimulating the Imagination

Horror movies offer several significant benefits by stimulating our imagination and creativity:

Ultimately, the power of imagination is the key to the horror movie genre’s appeal. It is what sets this form of entertainment apart from others and creates a lasting impact on audiences. Horror movies provide a unique opportunity to stimulate our minds and expand our horizons. As Stephen King once said, “Imagination is not a talent of some people, but is the health of every person.”

Identification and Empathy

Horror movies often feature a protagonist with whom we can identify and share their fears and struggles, forming emotional connections with the character. Stephen King explains that it’s through this identification that we are drawn into the story and invested in its outcome, as we experience the same emotions as the character.

Empathy plays a fundamental role in our psychological connection to horror movies. By immersing ourselves in the story, we gain a better understanding of human emotions and the complexities of the human psyche. Stephen King suggests that this empathy translates into our real-life experiences, improving our ability to relate to others and understand their emotions.

“We like to view ourselves as rational creatures, but we’re all emotional all the time, and horror movies tap into those emotions we don’t often let out.”

Adrenaline Rush and Biological Response

While horror films may be frightening, they also provide a rush of excitement. Stephen King notes that watching horror movies triggers a biological response in our bodies, releasing adrenaline and heightening our senses. The rush of adrenaline that comes with watching a scary scene is similar to that experienced during a fight-or-flight situation. The body’s fight-or-flight response prepares us to face danger by increasing our heart rate, speeding up our breathing, and activating our muscles.

The biological response in our bodies to horror movies can also lead to a feeling of euphoria. This feeling is caused by the release of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers, which are secreted in response to the excitement and fear that horror films produce. The release of endorphins can create a sense of pleasure and calm after the initial adrenaline rush has subsided.

Overall, horror movies have the ability to trigger a range of physiological responses in our bodies, from the release of adrenaline to the production of endorphins. These responses add an extra level of enjoyment to the horror film experience, providing the audience with a unique and exhilarating experience.

Societal Reflections and Commentary

In analyzing the themes of horror movies, Stephen King has pointed out that they often serve as a reflection of societal fears, anxieties, and cultural phenomena, providing a commentary on contemporary issues and social norms. By exploring our deepest fears and anxieties, horror movies expose the hidden anxieties of society, highlighting the issues we need to address and deal with.

Furthermore, through the portrayal of taboo topics and societal norms that are often too sensitive to discuss, horror movies provide a platform to confront these issues in a safe environment. As King puts it, “Horror movies are a way to confront our demons without putting ourselves in danger.”

“I think that we’re all mentally ill. Those of us outside the asylums only hide it a little better.” -Stephen King, Danse Macabre

By stimulating our imagination, horror movies offer a way to examine subconscious ideas and ideas that may be buried deep in our thoughts, yet play out in our current societal constructs. They can help us identify societal deviance by promoting empathy and understanding of darkness, while also serving as a commentary on social norms.

The importance of commentary and societal reflection in horror movies

The societal reflection aspect of horror movies cannot be ignored. It’s impossible to miss the commentary on the need for escapism in a capitalistic society, the dangers of unchecked power, and the risks of ignorance when confronting complex societal issues. Blending all these themes together, horror movies are not just a source of entertainment, they are an awareness-raising tool that helps audiences connect with societal issues they might otherwise be unaware of.

These discussions and reflections on society are what make horror movies so much more than jump scares and gore. Indeed, they push us to think and reflect on the world we live in and take action. Through this genre, we can approach many heavy topics, taste the fear, the thrill and simultaneously, take something constructive and useful.

In conclusion, Stephen King’s insightful analysis illuminates why we crave horror movies . From the psychological thrill of fear to the cathartic release they provide, horror movies tap into our primal instincts and offer a safe means of confronting societal taboos . They challenge our senses, stimulate our imagination, and foster empathy and emotional connections.

As King notes, horror movies also serve as a reflection of societal fears, anxieties, and cultural phenomena. Through their exploration of contemporary issues and social norms, they offer commentary and insight into our world.

Ultimately, King’s observations remind us of the powerful draw of horror movies and their ability to evoke intense emotions and sensations. As we continue to crave these experiences, we can look to King’s work as a guide to understanding the complex interplay between our psychology, emotions, and societal reflections .

So, the next time you find yourself drawn to a horror movie, take a moment to appreciate the many subtle factors that contribute to this attraction. And who better to guide you through this exploration than the master of horror himself, Stephen King?

Why are horror movies so popular?

Horror movies are popular because they tap into our primal instincts and provide a thrilling experience through fear. They allow us to release pent-up emotions and anxieties, offering a sense of catharsis and resolution. Additionally, horror movies offer a means of escaping the mundane aspects of everyday life and provide a platform to confront societal taboos in a safe environment. Furthermore, they cater to our fascination with the unknown and the human desire to explore the mysteries of the world. Horror movies also challenge our senses through visuals, sound effects, and suspenseful storytelling. They stimulate our imagination, fostering creativity and intense emotional reactions. Moreover, horror movies allow us to identify with characters, fostering empathy and emotional connections. Lastly, the physiological effects of watching horror movies, such as the release of adrenaline and the heightened senses, contribute to the allure . Overall, horror movies serve as a reflection of our society, often commenting on contemporary issues and social norms.

What insights does Stephen King provide about horror movies?

Stephen King offers various insights into the allure of horror movies. He emphasizes the psychological aspect, highlighting how they tap into our primal instincts and provide a thrilling experience through fear. King also discusses the concept of catharsis, illustrating how horror movies allow us to release pent-up emotions and anxieties. He suggests that horror movies offer an escape from routine and a means to confront societal taboos in a safe environment. Furthermore, King explores the fascination with the unknown and the human desire to explore mysteries. He examines how horror movies challenge our senses through visuals, sound effects, and suspenseful storytelling. King emphasizes the power of imagination , noting how horror movies stimulate creative thinking by immersing us in terrifying scenarios. Additionally, he discusses the identification with characters in horror movies, fostering empathy and emotional connections. Lastly, King highlights the physiological effects of watching horror movies, including the release of adrenaline and the heightened senses.

How do horror movies reflect societal fears and anxieties?

Horror movies often serve as a reflection of societal fears, anxieties, and cultural phenomena. They provide a platform to comment on contemporary issues and social norms. Through terrifying scenarios and monstrous creatures, horror movies depict the fears and anxieties that resonate with a wide audience. They address societal taboos and explore the darker aspects of human nature. Additionally, horror movies often incorporate subtexts and symbolism to comment on political, social, or cultural landscapes. By tapping into our collective fears, horror movies can provoke thought and initiate discussions about societal issues.

Explore More

- Rage Book Stephen King – Controversial Novel Insights

- Explore Stephen King’s Graveyard Shift Novella

- Best Stephen King Movies on YouTube

- Fairy Tale Stephen King PDF – Download Guide

- Stephen King’s Graveyard Shift: A Horror Gem

- Laurie Stephen King: Unraveling the Short Story

- Stephen King’s Favorite Books: Top Picks Revealed

- Stephen King’s Bag of Bones: A Haunting Read

- Stephen King vs Edgar Allan Poe: Literary Titans

- Stephen King’s My Pretty Pony: A Review

- Finn Stephen King – Unraveling the Narrative

- Stephen King’s Top Book Recommendations

Previous Post Stephen King's Award Wins Highlighted

Next post the breathing method: king's chilling novella, similar posts.

Friday essay: in praise of the ‘horror master’ Stephen King

Lecturer in Communications and Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

Disclosure statement

Ari Mattes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The University of Notre Dame Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Growing up in the 1980s, the name Stephen King was synonymous with macabre, terrifying, apparently taboo (though ubiquitous) book covers. They seemed to appear everywhere: bookstores, to be sure; but also newsagents, supermarkets, cinemas, airports and libraries. They always seemed to be spinning in some library carousel, looking tattered, like they’d been borrowed 100,000 times.

Like a kid from a King novel, I was obsessed with the forbidden. I would spend hours staring at these book covers, thinking about the horrors that might lie within.

A giant, bloody salivating dog. A freakish pair of eyes looking out of a drain. A silhouette of a figure with an axe eclipsing someone in a wheelchair. Hell, they looked more like movie posters than book covers. I’d go to bed and imagine one of these figures coming alive and creeping towards the house from the backyard.

Very occasionally, this was actually scary – but mostly it was just fun.

Why we love horror

Why do we gravitate towards subject matter that, if it existed in the real world, would be at best supremely unpleasant? There are many theories regarding why people love horror film and literature.

Perhaps it’s cathartic. Maybe it reflects Freud’s “ death drive ,” or what Edgar Allan Poe described, in a titular short story, as the “imp of the perverse,” (suggesting we all have self-destructive tendencies). Or maybe it simply reflects our fascination with extreme experiences, a desire to be overwhelmed by the sublime, which Edmund Burke defined as a mixture of fear and excitement, terror and awe. Perhaps horror thus manifests a desire to re-enchant the world with magic in a controlled and safe context, physically activating the body and its response mechanisms in an environment that only simulates real peril.

Friedrich Nietzsche wrote about the collective pleasure of inflicting pain on others through punishment. Does our fascination for horror channel this? Or, as Julia Kristeva ’s theory suggests, does art help us manage our abject horror at the breakdown between self and other – most pointedly captured in our confrontations with corpses?

Literary theorist René Girard ’s ideas are equally compelling. Perhaps we’re attracted to images of violence because of its anthropological function in the earliest periods of community formation. A victim – the scapegoat – would be chosen to bear the violence that would otherwise be destructively directed towards other members of the community. This idea is beautifully rendered in Drew Godard’s The Cabin in the Woods , a horror film about the origins of horror films in ritual and sacrifice.

In a broader cultural sense, our modern interest in horror, the supernatural and the weird has grown in direct proportion to industrialisation, and the parallel shrinking of the world’s magic and mysteries (captured in the term “globalisation”).

In a post-sacred era of intense scientific rationalism and technological development, the aesthetics of the weird, supernatural and horrific – in all their wondrous irrationality – allow us to occupy an alternate, imaginary space removed from the horror of things as they really are: mass industrial wars of attrition, precarious states of living, pandemic disease and global warming.

Read more: Friday essay: scary tales for scary times

My first King

When I finally had the autonomy (and my own money) to pick the books I wanted to read, it was with mixed feelings of shame and excitement that I went to buy my first Stephen King novel.

I still remember the suburban bookstore and the sardonic frown of its middle-aged clerk as she looked down at my ten-year-old self when I placed Pet Sematary on the counter and got 12 bucks out of my wallet. I remember blushing when she intimated (or was it actually a question?) I must have been buying this for an older relative.

The novel follows what happens to a doctor and his family when they discover, in the woods, a children’s pet cemetery that reanimates whatever is buried there. It lived up to the promise of its cover, offering splashes of superlative gore, a handful of genuinely terrifying moments (the sequences involving Rachel’s sick sister Zelda still get to me) and a plethora of new words. Not swear words, mind you – any self-respecting kid knows all of these by seven or eight – but terms like “cuckold”, about which I had to consult my mum.

For the next two years, I spent most of my reading time dedicated to King. I quickly got through the pantheon – massive tomes like The Stand , Needful Things and It ; more moderately sized ones like Carrie , The Shining and Salem’s Lot ; and short, explosive ones like The Running Man , published under King’s pseudonym, Richard Bachman. And then I started with the new releases (there was at least one every year – like 1994’s Insomnia ), generally available from Kmart in hardback.

I found in King an interlocutor who spoke with gusto and enthusiasm about all kinds of things – old age, domestic abuse, natural and supernatural horrors of the mind and closet. But, more than anything else, he seemed not only to write stories that often featured young characters, but to accurately dramatise what it actually felt like to be a kid.

Short stories like The Sun Dog , novels like Cycle of the Werewolf and the monumental It – not to mention more obvious outings like The Body, the basis of the massively successful nostalgia film Stand By Me – captured the peculiar melancholic excitement, both intense and slightly wistful, of being near the beginning of life in that delirious halcyon era just before puberty sets in.

Then I grew up – and stopped reading King. Through writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Jane Austen, I was introduced to prose worlds that seemed to be richer: both more concentrated and more expansive, certainly more nuanced. King gradually disappeared from my field of vision.

I forgot about the “gypsy” curse on Billy Halleck (the basis of Thinner ) and about Arnie and Dennis from Christine , as they struggle to overcome the eponymous evil car. Like one of the children of It – who forget their childhoods, until they reunite as adults to confront them – I forgot about my horror master, erasing my childhood experiences from memory. When I was 15, as a gag, I tried reading Firestarter and found it garish, gross, infantile. A few years earlier, King’s novel about a pyrokinetic child being hunted by a government who want to weaponise her would have seemed thrilling, maybe even insightful.

But the King was dead.

Read more: 'Supp'd full with horrors': 400 years of Shakespearean supernaturalism

Literary snobs and good writers

Perhaps the only thing worse than the literary snob who looks down on everyone who doesn’t read Joyce’s Ulysses on loop is the literary snob of the populist variety, the one who scowls at everyone who doesn’t read the kind of fiction that ord’nary folks like.

When outspoken literary critic and professor Harold Bloom described the 2003 awarding of the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters to Stephen King as “another low in the shocking process of dumbing down our cultural life,” it was easy to dislike Bloom as an example of the former. Listening to King discuss his writing, it is almost as easy to dismiss him as the latter.

What makes a good writer? According to King,

If you wrote something for which someone sent you a check, if you cashed the check and it didn’t bounce, and if you then paid the light bill with the money, I consider you talented.

So is King, as Bloom writes, “an immensely inadequate writer on a sentence-by-sentence, paragraph-by-paragraph, book-by-book basis”? King does, after all, describe his own work as “the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and a large fries from McDonald’s”. And there are numerous passages throughout his work – probably most pronouncedly in the words of writer Bill Denbrough in It – in which King expresses a serious disdain for academic knowledge and scholarship.

As Bloom would probably argue, consistency in style and tone, and complexity of form, are key elements underpinning any kind of aesthetic mastery. And it’s undeniable that King has produced a not-inconsiderable volume of poorly written and inconsistent work. Sometimes his novels warrant criticisms of pretentiousness, hackneyed style and tediously repetitive prose.

King may or may not be a great, or even good, writer. His more self-consciously serious stuff sometimes seems intolerable to me: kitsch is only fun if the attitude is fun. And some of his work ( Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption and Dolores Claiborne , for example) feels heavy-handed to the point of being virtually unreadable. Never mind – these works are frequently adapted into incredibly popular and incredibly dull films.

In any case, the debate continues to play out, with critics intermittently arguing for and against King’s writing. Dwight Allen, for example, wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books that King creates one-dimensional characters in dull prose. In the same publication, Sarah Langan responded :

All of [King’s] novels, even the stinkers, have resonance. […] his fiction isn’t just reflective of the current culture, it casts judgement. […] No one except King challenges [Americans] so relentlessly, to be brave. To kill our monsters.

King is, undeniably, a juggernaut of commercial literary production – an industry unto himself, a literary and cinematic brand – who has written a handful of genuine horror genre masterpieces throughout his career.

Perhaps it’s in part this combination of prolific volume and intermittent brilliance that keeps me, like an addict, coming back for more.

Ultimately, though, I would suggest I like reading King for the same reason so many others do, a reason that accounts for his enduring popularity when better horror stylists (King’s contemporaries Clive Barker and Peter Straub , for example) have fallen by the wayside. And that’s his unprecedented capacity to tap into nostalgia.

Returning to King-world

Nearly 20 years after I gave up on Stephen King, in one of those random nostalgic moments that seem to populate his fictional world, my brother gave me Revival for Christmas.

King’s Frankensteinian novel, published in 2014, is about the aftermath of an encounter between a young boy and a Methodist minister fascinated by electricity. After years of mainly reading what is sometimes pretentiously called “literary” fiction, and mostly avoiding anything written after the 19th or very early 20th centuries, I returned to King-world.

And I was dazzled by what I found there, realising what I must have known as a kid: King is a superb storyteller. Much of his work is characterised by an infectiously energetic prose style, governed by a flair for simple but satisfying plotting and a supremely inventive imagination.

And – yep – I was stunned by his capacity to precisely render in prose, perhaps more acutely than any other contemporary writer, the confusing, often hokey and melodramatic, but always exciting images, emotions, and sensibilities of youth.

I realised there’s something brilliant, and totally inimitable, about King. Despite his work’s sometimes kitsch silliness (a hazard of the horror genre), despite the not uncommon misfires – and despite the absurdly voluminous output - King is able to authentically generate an atmosphere of nostalgia that taps into something at the very core of the pleasure of reading.

Read more: Frankenstein: how Mary Shelley's sci-fi classic offers lessons for us today about the dangers of playing God

It: a masterpiece of nostalgia

His novel It is a case in point: a masterclass in narrative development through a nostalgic structure.

It – for anyone who hasn’t read it, or seen one of the three film adaptations – cuts between the adult lives and childhoods of a group of misfits, the “ Losers Club ”, who collectively band together to fight the evil of their town, Derry. That evil takes the form of a shape-shifting clown, Pennywise.

The Losers Club battled and banished Pennywise as kids, but now “it” has come back. The club members return from around the world to live up to their childhood promise: that if “it” ever returns, they, too, will return to fight “it”. The narrative cuts between characters, en route to Derry, as they recall forgotten passages from their childhood “it’s” return has forced them to remember.

So, the novel is structured around a nostalgic trope: adults literally remembering and reconstructing their childhood in the present. At the same time, the town Derry is developed by King according to a quintessentially nostalgic image of the American small town, recalling peak 1950s Americana. Think Grease : soda fountains, switchblades and quiffs. But behind closed doors, fathers abuse daughters, mothers keep their children sick, and a monster that assumes the form of whatever demon most terrifies you stalks the streets, killing and eating children.

The narrative architecture is starkly simple, sustaining a profound sense of dread in the reader. The characters remember a dreadful past, in a present-future they wish had never materialised. Perhaps nostalgia always contains shades of the dreadful, given its suggestion that one’s future is foreclosed, that all we have are memories of a better time: memories that only exist as memories.

In some of King’s work – Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, for example – nostalgia acts mainly as window dressing, functioning primarily as an aesthetic. But in It, nostalgia is neither incidental nor benign: it’s a way of exploring the impossibility of having to remember trauma .