An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review

Jiaqi xiong.

a Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

Orly Lipsitz

c Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario

Flora Nasri

Leanna m.w. lui, hartej gill, david chen-li, michelle iacobucci.

e Department of Psychological Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

f Institute for Health Innovation and Technology (iHealthtech), National University of Singapore, Singapore

Amna Majeed

Roger s. mcintyre.

b Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

d Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, ON

Associated Data

As a major virus outbreak in the 21st century, the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to unprecedented hazards to mental health globally. While psychological support is being provided to patients and healthcare workers, the general public's mental health requires significant attention as well. This systematic review aims to synthesize extant literature that reports on the effects of COVID-19 on psychological outcomes of the general population and its associated risk factors.

A systematic search was conducted on PubMed, Embase, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to 17 May 2020 following the PRISMA guidelines. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. Articles were selected based on the predetermined eligibility criteria.

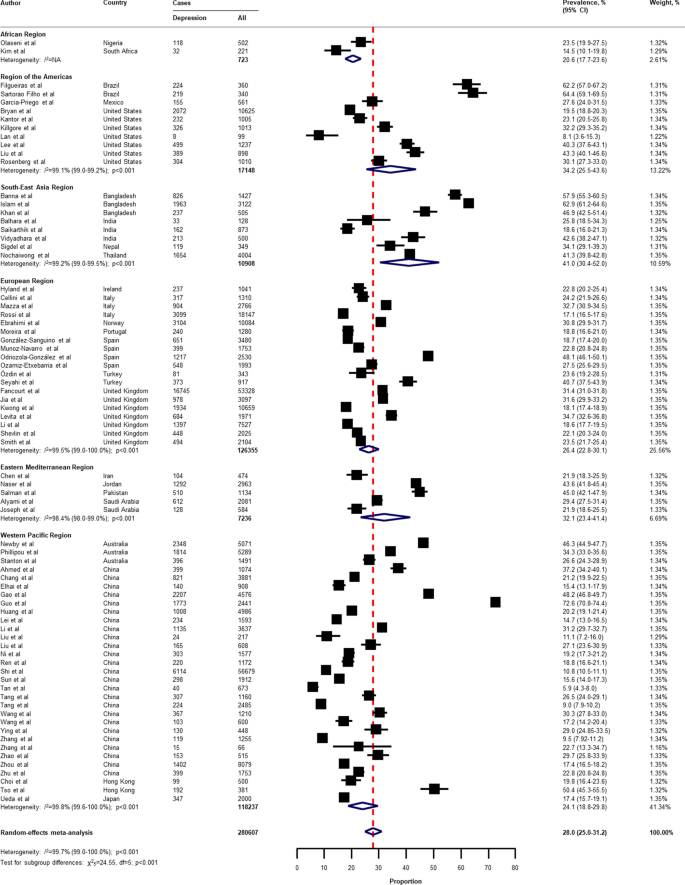

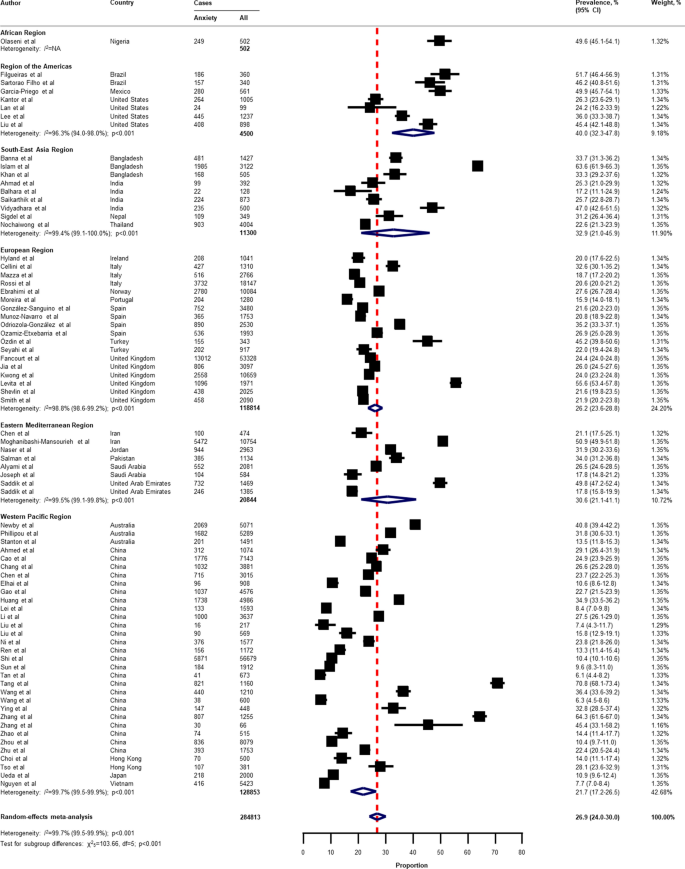

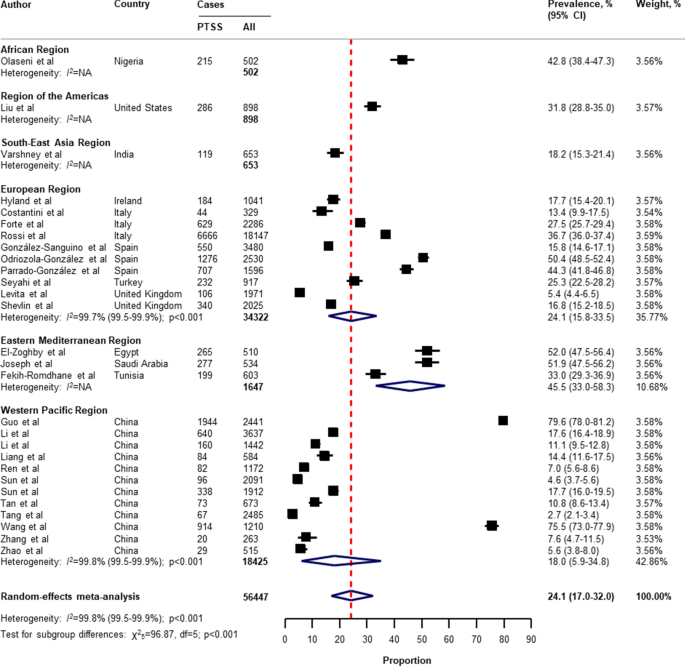

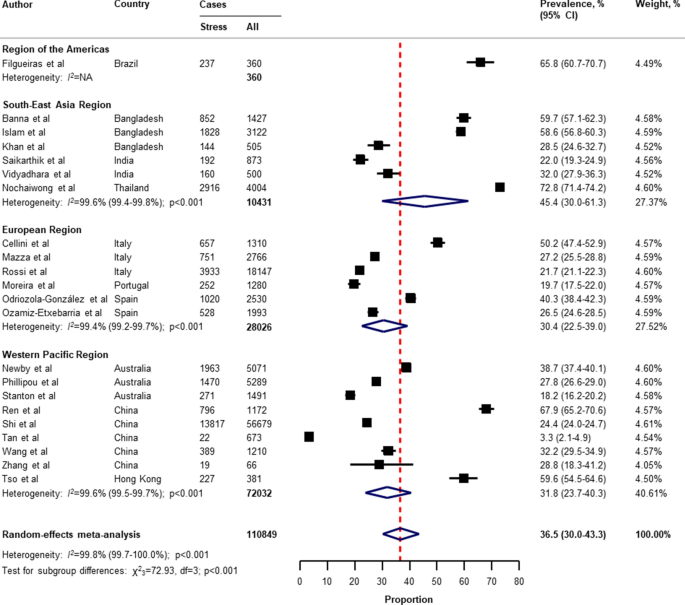

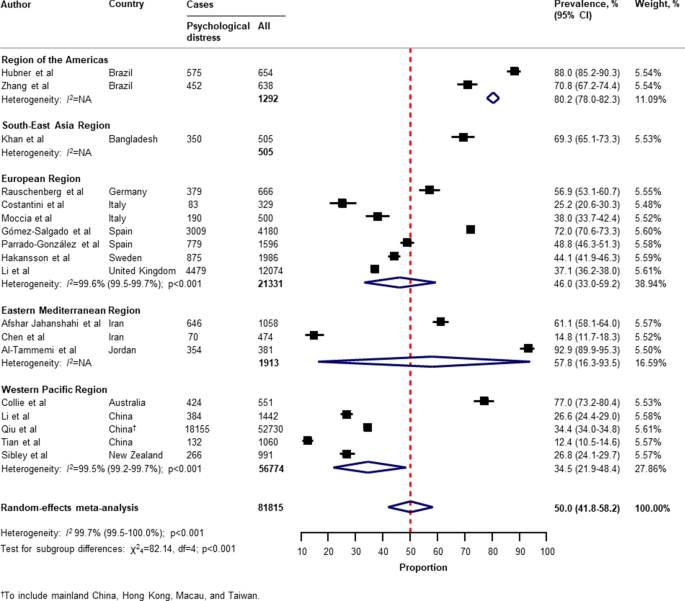

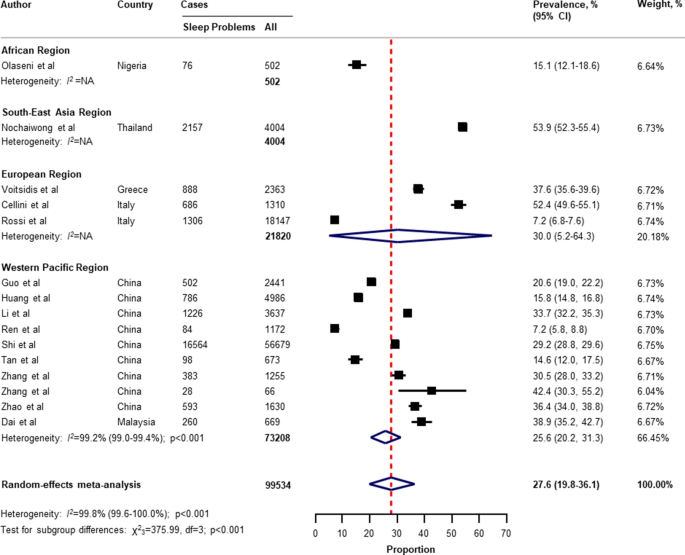

Results: Relatively high rates of symptoms of anxiety (6.33% to 50.9%), depression (14.6% to 48.3%), post-traumatic stress disorder (7% to 53.8%), psychological distress (34.43% to 38%), and stress (8.1% to 81.9%) are reported in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in China, Spain, Italy, Iran, the US, Turkey, Nepal, and Denmark. Risk factors associated with distress measures include female gender, younger age group (≤40 years), presence of chronic/psychiatric illnesses, unemployment, student status, and frequent exposure to social media/news concerning COVID-19.

Limitations

A significant degree of heterogeneity was noted across studies.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with highly significant levels of psychological distress that, in many cases, would meet the threshold for clinical relevance. Mitigating the hazardous effects of COVID-19 on mental health is an international public health priority.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a cluster of atypical cases of pneumonia was reported in Wuhan, China, which was later designated as Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 Feb 2020 ( Anand et al., 2020 ). The causative virus, SARS-CoV-2, was identified as a novel strain of coronaviruses that shares 79% genetic similarity with SARS-CoV from the 2003 SARS outbreak ( Anand et al., 2020 ). On 11 Mar 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak a global pandemic ( Anand et al., 2020 ).

The rapidly evolving situation has drastically altered people's lives, as well as multiple aspects of the global, public, and private economy. Declines in tourism, aviation, agriculture, and the finance industry owing to the COVID-19 outbreak are reported as massive reductions in both supply and demand aspects of the economy were mandated by governments internationally ( Nicola et al., 2020 ). The uncertainties and fears associated with the virus outbreak, along with mass lockdowns and economic recession are predicted to lead to increases in suicide as well as mental disorders associated with suicide. For example, McIntyre and Lee (2020b) have reported a projected increase in suicide from 418 to 2114 in Canadian suicide cases associated with joblessness. The foregoing result (i.e., rising trajectory of suicide) was also reported in the USA, Pakistan, India, France, Germany, and Italy ( Mamun and Ullah, 2020 ; Thakur and Jain, 2020 ). Separate lines of research have also reported an increase in psychological distress in the general population, persons with pre-existing mental disorders, as well as in healthcare workers ( Hao et al., 2020 ; Tan et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020b ). Taken together, there is an urgent call for more attention given to public mental health and policies to assist people through this challenging time.

The objective of this systematic review is to summarize extant literature that reported on the prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other forms of psychological distress in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. An additional objective was to identify factors that are associated with psychological distress.

Methods and results were formated based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Moher et al., 2010 ).

2.1. Search strategy

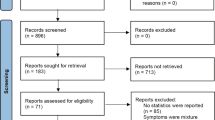

A systematic search following the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram ( Fig. 1 ) was conducted on PubMed, Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to 17 May 2020. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. The search terms that were used were: (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 OR 2019nCoV OR HCoV-19) AND (Mental health OR Psychological health OR Depression OR Anxiety OR PTSD OR PTSS OR Post-traumatic stress disorder OR Post-traumatic stress symptoms) AND (General population OR general public OR Public OR community). An example of search procedure was included as a supplementary file.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study selection flow diagram. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. Study selection and eligibility criteria

Titles and abstracts of each publication were screened for relevance. Full-text articles were accessed for eligibility after the initial screening. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) followed cross-sectional study design; 2) assessed the mental health status of the general population/public during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated risk factors; 3) utilized standardized and validated scales for measurement. Studies were excluded if they: 1) were not written in English or Chinese; 2) focused on particular subgroups of the population (e.g., healthcare workers, college students, or pregnant women); 3) were not peer-reviewed; 4) did not have full-text availability.

2.3. Data extraction

A data extraction form was used to include relevant data: (1) Lead author and year of publication, (2) Country/region of the population studied, (3) Study design, (4) Sample size, (5) Sample characteristics, (6) Assessment tools, (7) Prevalence of symptoms of depression/anxiety/ PTSD/psychological distress/stress, (8) Associated risk factors.

2.4 Quality appraisal

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies was used for study quality appraisal, which was modified accordingly from the scale used in Epstein et al. (2018) . The scale consists of three dimensions: Selection, Comparability, and Outcome. There are seven categories in total, which assess the representativeness of the sample, sample size justification, comparability between respondents and non-respondents, ascertainments of exposure, comparability based on study design or analysis, assessment of the outcome, and appropriateness of statistical analysis. A list of specific questions was attached as a supplementary file. A total of nine stars can be awarded if the study meets certain criteria, with a maximum of four stars assigned for the selection dimension, a maximum of two stars assigned for the comparability dimension, and a maximum of three stars assigned for the outcome dimension.

3.1. Search results

In total, 648 publications were identified. Of those, 264 were removed after initial screening due to duplication. 343 articles were excluded based on the screening of titles and abstracts. 41 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. There were 12 articles excluded for studying specific subgroups of the population, five articles excluded for not having a standardized/ appropriate measure, three articles excluded for being review papers, and two articles excluded for being duplicates. Following the full-text screening, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria.

3.2. Study characteristics

Study characteristics and primary study findings are summarized in Table 1 . The sample size of the 19 studies ranged from 263 to 52,730 participants, with a total of 93,569 participants. A majority of study participants were over 18 years old. Female participants ( n = 60,006) made up 64.1% of the total sample. All studies followed a cross-sectional study design. The 19 studies were conducted in eight different countries, including China ( n = 10), Spain ( n = 2), Italy ( n = 2), Iran ( n = 1), the US ( n = 1), Turkey ( n = 1), Nepal ( n = 1), and Denmark ( n = 1). The primary outcomes chosen in the included studies varied across studies. Twelve studies included measures of depressive symptoms while eleven studies included measures of anxiety. Symptoms of PTSD/psychological impact of events were evaluated in four studies while three studies assessed psychological distress. It was additionally observed that four studies contained general measures of stress. Three studies did not explicitly report the overall prevalence rates of symptoms; notwithstanding the associated risk factors were identified and discussed.

Summary of study sample characteristics, study design, assessment tools used, prevalence rates and associated risk factors.

3.3. Quality appraisal

The result of the study quality appraisal is presented in Table 2 . The overall quality of the included studies is moderate, with total stars awarded varying from four to eight. There were two studies with four stars, two studies with five stars, seven studies with six stars, seven studies with seven stars, and one study with eight stars.

Results of study quality appraisal of the included studies.

3.4. Measurement tools

A variety of scales were used in the studies ( n = 19) for assessing different adverse psychological outcomes. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Patient Health Questionnaire-9/2 (PHQ-9/2), Self-rating Depression Scales (SDS), The World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) were used for measuring depressive symptoms. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7/2-item (GAD-7/2), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) were used to evaluate symptoms of anxiety. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale- 21 items (DASS-21) was used for the evaluation of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used for assessing anxiety and depressive symptoms. Psychological distress was measured by The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (CPDI) and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6/10). Symptoms of PTSD were assessed by The Impact of Event Scale-(Revised) (IES(-R)), PTSD Checklist (PCL-(C)-2/5). Chinese Perceived Stress Scale (CPSS-10) was used in one study to evaluate symptoms of stress.

3.5. Symptoms of depression and associated risk factors

Symptoms of depression were assessed in 12 out of the 19 studies ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and S.B. Özdin, 2020 ; Sønderskov et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ). The prevalence of depressive symptoms ranged from 14.6% to 48.3%. Although the reported rates are higher than previously estimated one-year prevalence (3.6% and 7.2%) of depression among the population prior to the pandemic ( Huang et al., 2019 ; Lim et al., 2018 ), it is important to note that presence of depressive symptoms does not reflect a clinical diagnosis of depression.

Many risk factors were identified to be associated with symptoms of depression amongst the COVID-19 pandemic. Females were reported as are generally more likely to develop depressive symptoms when compared to their male counterparts ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Sønderskov et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). Participants from the younger age group (≤40 years) presented with more depressive symptoms ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ;). Student status was also found to be a significant risk factor for developing more depressive symptoms as compared to other occupational statuses (i.e. employment or retirement) ( González et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ). Four studies also identified lower education levels as an associated factor with greater depressive symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). A single study by Wang et al., 2020b reported that people with higher education and professional jobs exhibited more depressive symptoms in comparison to less educated individuals and those in service or enterprise industries.

Other predictive factors for symptoms of depression included living in urban areas, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, being divorced/widowed, being single, lower household income, quarantine status, worry about being infected, property damage, unemployment, not having a child, a past history of mental stress or medical problems, having an acquaintance infected with COVID-19, perceived risks of unemployment, exposure to COVID-19 related news, higher perceived vulnerability, lower self-efficacy to protect themselves, the presence of chronic diseases, and the presence of specific physical symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ).

3.6. Symptoms of anxiety and associated risk factors

Anxiety symptoms were assessed in 11 out of the 19 studies, with a noticeable variation in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms ranging from 6.33% to 50.9% ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ).

Anxiety is often comorbid with depression ( Choi et al., 2020 ). Some predictive factors for depressive symptoms also apply to symptoms of anxiety, including a younger age group (≤40 years), lower education levels, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, female gender, divorced/widowed status, quarantine status, worry about being infected, property damage, history of mental health issue/medical problems, presence of chronic illness, living in urban areas, and the presence of specific physical symptoms ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ).

Additionally, social media exposure or frequent exposure to news/information concerning COVID-19 was positively associated with symptoms of anxiety ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ). With respect to marital status, one study reported that married participants had higher levels of anxiety when compared to unmarried participants ( Gao et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, Lei et al. (2020) found that divorced/widowed participants developed more anxiety symptoms than single or married individuals. A prolonged period of quarantine was also correlated with higher risks of anxiety symptoms. Intuitively, contact history with COVID-positive patients or objects may lead to more anxiety symptoms, which is noted in one study ( Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ).

3.7. Symptoms of PTSD/ psychological distress/stress and associated risk factors

With respect to PTSD symptoms, similar prevalence rates were reported by Zhang and Ma (2020) and N. Liu et al. (2020) at 7.6% and 7%, respectively. Despite using the same measurement scale as Zhang and Ma (2020) (i.e., IES), Wang et al. (2020a) noted a remarkably different result, with 53.8% of the participants reporting moderate-to-severe psychological impact. González et al. ( González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ) noted 15.8% of participants with PTSD symptoms. Three out of the four studies that measured the traumatic effects of COVID-19 reported that the female gender was more susceptible to develop symptoms of PTSD. In contrast, the research conducted by Zhang and Ma (2020) found no significant difference in IES scores between females and males. Other risk factors included loneliness, individuals currently residing in Wuhan or those who have been to Wuhan in the past several weeks (the hardest-hit city in China), individuals with higher susceptibility to the virus, poor sleep quality, student status, poor self-rated health, and the presence of specific physical symptoms. Besides sex, Zhang and Ma (2020) found that age, BMI, and education levels are also not correlated with IES-scores.

Non-specific psychological distress was also assessed in three studies. One study reported a prevalence rate of symptoms of psychological distress at 38% ( Moccia et al., 2020 ), while another study from Qiu et al. (2020) reported a prevalence of 34.43%. The study from Wang et al. (2020) did not explicitly state the prevalence rates, but the associated risk factors for higher psychological distress symptoms were reported (i.e., younger age groups and female gender are more likely to develop psychological distress) ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Other predictive factors included being migrant workers, profound regional severity of the outbreak, unmarried status, the history of visiting Wuhan in the past month, higher self-perceived impacts of the epidemic ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, researchers have identified personality traits to be predictive of psychological distresses. For example, persons with negative coping styles, cyclothymic, depressive, and anxious temperaments exhibit greater susceptibility to psychological outcomes ( Wang et al., 2020 ; Moccia et al., 2020 ).

The intensity of overall stress was evaluated and reported in four studies. The prevalence of overall stress was variably reported between 8.1% to over 81.9% ( Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ). Females and the younger age group are often associated with higher stress levels as compared to males and the elderly. Other predictive factors of higher stress levels include student status, a higher number of lockdown days, unemployment, having to go out to work, having an acquaintance infected with the virus, presence of chronic illnesses, poor self-rated health, and presence of specific physical symptoms ( Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ).

3.8. A separate analysis of negative psychological outcomes

Out of the nineteen included studies, five studies appeared to be more representative of the general population based on the results of study quality appraisal ( Table 1 ). A separate analysis was conducted for a more generalizable conclusion. According to the results of these studies, the rates of negative psychological outcomes were moderate but higher than usual, with anxiety symptoms ranging from 6.33% to 18.7%, depressive symptoms ranging from 14.6% to 32.8%, stress symptoms being 27.2%, and symptoms of PTSD being approximately 7% ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020b ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). In these studies, female gender, younger age group (≤40 years), and student population were repetitively reported to exhibit more adverse psychiatric symptoms.

3.9. Protective factors against symptoms of mental disorders

In addition to associated risk factors, a few studies also identified factors that protect individuals against symptoms of psychological illnesses during the pandemic. Timely dissemination of updated and accurate COVID-19 related health information from authorities was found to be associated with lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms in the general public ( Wang et al., 2020a ). Additionally, actively carrying out precautionary measures that lower the risk of infection, such as frequent handwashing, mask-wearing, and less contact with people also predicted lower psychological distress levels during the pandemic ( Wang et al., 2020a ). Some personality traits were shown to correlate with positive psychological outcomes. Individuals with positive coping styles, secure and avoidant attachment styles usually presented fewer symptoms of anxiety and stress ( Wang et al., 2020 ; Moccia et al., 2020 ). ( Zhang et al. 2020 ) also found that participants with more social support and time to rest during the pandemic exhibited lower stress levels.

4. Discussion

Our review explored the mental health status of the general population and its predictive factors amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, there is a higher prevalence of symptoms of adverse psychiatric outcomes among the public when compared to the prevalence before the pandemic ( Huang et al., 2019 ; Lim et al., 2018 ). Variations in prevalence rates across studies were noticed, which could have resulted from various measurement scales, differential reporting patterns, and possibly international/cultural differences. For example, some studies reported any participants with scores above the cut-off point (mild-to-severe symptoms), while others only included participants with moderate-to-severe symptoms ( Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). Regional differences existed with respect to the general public's psychological health during a massive disease outbreak due to varying degrees of outbreak severity, national economy, government preparedness, availability of medical supplies/ facilities, and proper dissemination of COVID-related information. Additionally, the stage of the outbreak in each region also affected the psychological responses of the public. Symptoms of adverse psychological outcomes were more commonly seen at the beginning of the outbreak when individuals were challenged by mandatory quarantine, unexpected unemployment, and uncertainty associated with the outbreak ( Ho et al., 2020 ). When evaluating the psychological impacts incurred by the coronavirus outbreak, the duration of psychiatric symptoms should also be taken into consideration since acute psychological responses to stressful or traumatic events are sometimes protective and of evolutionary importance ( Yaribeygi et al., 2017 ; Brosschot et al., 2016 ; Gilbert, 2006 ). Being anxious and stressed about the outbreak mobilizes people and forces them to implement preventative measures to protect themselves. Follow-up studies after the pandemic may be needed to assess the long-term psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.1. Populations with greater susceptibility

Several predictive factors were identified from the studies. For example, females tended to be more vulnerable to develop the symptoms of various forms of mental disorders during the pandemic, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and stress, as reported in our included studies ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ). Greater psychological distress arose in women partially because they represent a higher percentage of the workforce that may be negatively affected by COVID-19, such as retail, service industry, and healthcare. In addition to the disproportionate effects that disruption in the employment sector has had on women, several lines of research also indicate that women exhibit differential neurobiological responses when exposed to stressors, perhaps providing the basis for the overall higher rate of select mental disorders in women ( Goel et al., 2014 ; Eid et al., 2019 ).

Individuals under 40 years old also exhibited more adverse psychological symptoms during the pandemic ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ). This finding may in part be due to their caregiving role in families (i.e., especially women), who provide financial and emotional support to children or the elderly. Job loss and unpredictability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic among this age group could be particularly stressful. Also, a large proportion of individuals under 40 years old consists of students who may also experience more emotional distress due to school closures, cancelation of social events, lower study efficiency with remote online courses, and postponements of exams ( Cao et al., 2020 ). This is consistent with our findings that student status was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 , Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ).

People with chronic diseases and a history of medical/ psychiatric illnesses showed more symptoms of anxiety and stress ( Mazza et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ). The anxiety and distress of chronic disease sufferers towards the coronavirus infection partly stem from their compromised immunity caused by pre-existing conditions, which renders them susceptible to the infection and a higher risk of mortality, such as those with systemic lupus erythematosus ( Sawalha et al., 2020 ). Several reports also suggested that a substantially higher death rate was noted in patients with diabetes, hypertension and other coronary heart diseases, yet the exact causes remain unknown ( Guo et al., 2020 ; Emami et al., 2020 ), leaving those with these common chronic conditions in fear and uncertainty. Additionally, another practical aspect of concern for patients with pre-existing conditions would be postponement and inaccessibility to medical services and treatment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, as a rapidly growing number of COVID-19 patients were utilizing hospital and medical resources, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of other diseases may have unintentionally been affected. Individuals with a history of mental disorders or current diagnoses of psychiatric illnesses are also generally more sensitive to external stressors, such as social isolation associated with the pandemic ( Ho et al., 2020 ).

4.2. COVID-19 related psychological stressors

Several studies identified frequent exposure to social media/news relating to COVID-19 as a cause of anxiety and stress symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ). Frequent social media use exposes oneself to potential fake news/reports/disinformation and the possibility for amplified anxiety. With the unpredictable situation and a lot of unknowns about the novel coronavirus, misinformation and fake news are being easily spread via social media platforms ( Erku et al., 2020 ), creating unnecessary fears and anxiety. Sadness and anxious feelings could also arise when constantly seeing members of the community suffering from the pandemic via social media platforms or news reports ( Li et al., 2020 ).

Reports also suggested that poor economic status, lower education level, and unemployment are significant risk factors for developing symptoms of mental disorders, especially depressive symptoms during the pandemic period ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ;). The coronavirus outbreak has led to strictly imposed stay-home-order and a decrease in demands for services and goods ( Nicola et al., 2020 ), which has adversely influenced local businesses and industries worldwide. Surges in unemployment rates were noted in many countries ( Statistics Canada, 2020 ; Statista, 2020 ). A decrease in quality of life and uncertainty as a result of financial hardship can put individuals into greater risks for developing adverse psychological symptoms ( Ng et al., 2013 ).

4.3. Efforts to reduce symptoms of mental disorders

4.3.1. policymaking.

The associated risk and protective factors shed light on policy enactment in an attempt to relieve the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general public. Firstly, more attention and assistance should be prioritized to the aforementioned vulnerable groups of the population, such as the female gender, people from age group ≤40, college students, and those suffering from chronic/psychiatric illnesses. Secondly, governments must ensure the proper and timely dissemination of COVID-19 related information. For example, validation of news/reports concerning the pandemic is essential to prevent panic from rumours and false information. Information about preventative measures should also be continuously updated by health authorities to reassure those who are afraid of being infected ( Tran, et al., 2020a ). Thirdly, easily accessible mental health services are critical during the period of prolonged quarantine, especially for those who are in urgent need of psychological support and individuals who reside in rural areas ( Tran et al., 2020b ). Since in-person health services are limited and delayed as a result of COVID-19 pandemic, remote mental health services can be delivered in the form of online consultation and hotlines ( Liu et al., 2020 ; Pisciotta et al., 2019 ). Last but not least, monetary support (e.g. beneficial funds, wage subsidy) and new employment opportunities could be provided to people who are experiencing financial hardship or loss of jobs owing to the pandemic. Government intervention in the form of financial provisions, housing support, access to psychiatric first aid, and encouragement at the individual level of healthy lifestyle behavior has been shown effective in alleviating suicide cases associated with economic recession ( McIntyre and Lee, 2020a ). For instance, declines in suicide incidence were observed to be associated with government expenses in Japan during the 2008 economic depression ( McIntyre and Lee, 2020a ).

4.3.2. Individual efforts

Individuals can also take initiatives to relieve their symptoms of psychological distress. For instance, exercising regularly and maintaining a healthy diet pattern have been demonstrated to effectively ease and prevent symptoms of depression or stress ( Carek et al., 2011 ; Molendijk et al., 2018 ; Lassale et al., 2019 ). With respect to pandemic-induced symptoms of anxiety, it is also recommended to distract oneself from checking COVID-19 related news to avoid potential false reports and contagious negativity. It is also essential to obtain COVID-19 related information from authorized news agencies and organizations and to seek medical advice only from properly trained healthcare professionals. Keeping in touch with friends and family by phone calls or video calls during quarantine can ease the distress from social isolation ( Hwang et al., 2020 ).

4.4. Strengths

Our paper is the first systematic review that examines and summarizes existing literature with relevance to the psychological health of the general population during the COVID-19 outbreak and highlights important associated risk factors to provide suggestions for addressing the mental health crisis amid the global pandemic.

4.5. Limitations

Certain limitations apply to this review. Firstly, the description of the study findings was qualitative and narrative. A more objective systematic review could not be conducted to examine the prevalence of each psychological outcome due to a high heterogeneity across studies in the assessment tools used and primary outcomes measured. Secondly, all included studies followed a cross-sectional study design and, as such, causal inferences could not be made. Additionally, all studies were conducted via online questionnaires independently by the study participants, which raises two concerns: 1] Individual responses in self-assessment vary in objectivity when supervision from a professional psychiatrist/ interviewer is absent, 2] People with poor internet accessibility were likely not included in the study, creating a selection bias in the population studied. Another concern is the over-representation of females in most studies. Selection bias and over-representation of particular groups indicate that most studies may not be representative of the true population. Importantly, studies in inclusion were conducted in a limited number of countries. Thus generalizations of mental health among the general population at a global level should be made cautiously.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review examined the psychological status of the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic and stressed the associated risk factors. A high prevalence of adverse psychiatric symptoms was reported in most studies. The COVID-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented threat to mental health in high, middle, and low-income countries. In addition to flattening the curve of viral transmission, priority needs to be given to the prevention of mental disorders (e.g. major depressive disorder, PTSD, as well as suicide). A combination of government policy that integrates viral risk mitigation with provisions to alleviate hazards to mental health is urgently needed.

Authorship contribution statement

JX contributed to the overall design, article selection , review, and manuscript preparation. LL and JX contributed to study quality appraisal. All other authors contributed to review, editing, and submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgements.

RSM has received research grant support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases/National Natural Science Foundation of China and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Shire, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, and Minerva.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 .

Appendix. Supplementary materials

- Ahmed M.Z., Ahmed O., Zhou A., Sang H., Liu S., Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020; 51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anand K.B., Karade S., Sen S., Gupta R.M. SARS-CoV-2: camazotz's curse. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2020; 76 :136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.04.008. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brosschot J.F., Verkuil B., Thayer J.F. The default response to uncertainty and the importance of perceived safety in anxiety and stress: an evolution-theoretical perspective. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016; 41 :22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.04.012. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cao W., Fang Z., Hou G., Han M., Xu X., Dong J., Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 287 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carek P.J., Laibstain S.E., Carek S.M. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011; 41 (1):15–28. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.c. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi K.W., Kim Y., Jeon H.J. Comorbid Anxiety and Depression: clinical and Conceptual Consideration and Transdiagnostic Treatment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020; 1191 :219–235. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_14. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eid R.S., Gobinath A.R., Galea L.A.M. Sex differences in depression: insights from clinical and preclinical studies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019; 176 :86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.01.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Emami A., Javanmardi F., Pirbonyeh N., Akbari A. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020; 8 (1):e35. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v8i1.600.g748. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Epstein S., Roberts E., Sedgwick R., Finning K., Ford T., Dutta R., Downs J. Poor school attendance and exclusion: a systematic review protocol on educational risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviours. BMJ Open. 2018; 8 (12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023953. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Erku D.A., Belachew S.W., Abrha S., Sinnollareddy M., Thoma J., Steadman K.J., Tesfaye W.H. When fear and misinformation go viral: pharmacists' role in deterring medication misinformation during the 'infodemic' surrounding COVID-19. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.032. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Wang Y., Fu H., Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert P. Evolution and depression: issues and implications. Psycho. Med. 2006; 36 (3):287–297. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006112. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goel N., Workman J.L., Lee T.F., Innala L., Viau V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr. Physiol. 2014; 4 (3):1121‐1155. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130054. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- González-Sanguino C., Ausín B., Castellanos M.A., Saiz J., López-Gómez A., Ugidos C., Muñoz M. Mental Health Consequences during the Initial Stage of the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo W., Li M., Dong Y., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Tian C., Qin R., Wang H., Shen Y., Du K., Zhao L., Fan H., Luo S., Hu D. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Jiang X., McIntyre R.S., Tran B., Sun J., Zhang Z., Ho R., Ho C., Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ho C.S.H., Chee C.Y., Ho R.C.M. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2020; 49 (3):155–160. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang Y., et al. . Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiat. 2019; 6 (3):211–224. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hwang T., Rabheru K., Peisah C., Reichman W., Ikeda M. Loneliness and social isolation during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000988. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lassale C., Batty G.D., Baghdadli A., Jacka F., Sánchez-Villegas A., Kivimäki M., Akbaraly T. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019; 24 :965–986. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lei L., Huang X., Zhang S., Yang J., Yang L., Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the covid-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020; 26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li Z., et al. . Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immum. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim G.Y., Tam W.W., Lu Y., Ho C.S., Zhang M.W., Ho R.C. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2018; 8 (1):2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu N., Zhang F., Wei C., Jia Y., Shang Z., Sun L., Wu L., Sun Z., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Liu W. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 287 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S., Yang L., Zhang C., Xiang Y., Liu Z., Hu S., Zhang B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiat. 2020; 7 (4):e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mamun M.A., Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty?—The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mazza C., Ricci E., Biondi S., Colasanti M., Ferracuti S., Napoli C., Roma P. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 :3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McIntyre R.S., Lee Y. Preventing suicide in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020; 19 (2):250–251. doi: 10.1002/wps.20767. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McIntyre R.S., Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113104. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moccia L., Janiri D., Pepe M., Dattoli L., Molinaro M., Martin V.D., Chieffo D., Janiri L., Fiorillo A., Sani G., Nicola M.D. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020; 51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010; 8 (5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Molendijk M., Molero P., Sánchez-Pandreño F.O., Van der Dose W., Martínez-González M.A. Diet quality and depression risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2018; 226 :346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng K.H., Agius M., Zaman R. The global economic crisis: effects on mental health and what can be done. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013; 106 :211–214. doi: 10.1177/0141076813481770. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha M., Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020; 78 :185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olagoke A.A., Olagoke O.O., Hughes A.M. Exposure to coronavirus news on mainstream media: the role of risk perceptions and depression. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12427. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria N., Dosil-Santamaria M., Picaza-Gorrochategui M., Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad. Saude. Publica. 2020; 36 (4) doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Özdin S., Özdin S.B. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pisciotta M., Denneson L.M., Williams H.B., Woods S., Tuepker A., Dobscha S.K. Providing mental health care in the context of online mental health notes: advice from patients and mental health clinicians. J. Ment. Health. 2019; 28 (1):64–70. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1521924. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr. 2020; 33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Samadarshi S.C.A., Sharma S., Bhatta J. An online survey of factors associated with self-perceived stress during the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in Nepal. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2020; 34 (2):1–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sawalha A.H., Zhao M., Coit P., Lu Q. Epigenetic dysregulation of ACE2 and interferon-regulated genes might suggest increased COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in lupus patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 2020; 215 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sønderskov K.M., Dinesen P.T., Santini Z.I., Østergaard S.D. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.15. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Statista, 2020. Monthly unemployment rate in the United States from May 2019 to May 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/273909/seasonally-adjusted-monthly-unemployment-rate-in-the-us/ (Accessed June 12 2020,).

- Statistic Canada, 2020. Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months. https://doi.org/10.25318/1410028701-eng(Accessed June 12 2020,).

- Tan W., Hao F., McIntyre R.S., Jiang L., Jiang X., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Zhang Z., Lai A., Ho R., Tran B., Ho C., Tam W. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thakur V., Jain A. COVID 2019-Suicides: a global psychological pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ] Retracted

- Tran B.X., et al. Coverage of Health Information by Different Sources in Communities: implication for COVID-19 Epidemic Response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (10):3577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103577. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tran B.X., Phan H.T., Nguyen T.P.T., Hoang M.T., Vu G.T., Lei H.T., Latkin C.A., Ho C.S.H., Ho R.C.M. Reaching further by Village Health Collaborators: the informal health taskforce of Vietnam for COVID-19 responses. J. Glob. Health. 2020; 10 (1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010354. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., Choo F.N., Tran B., Ho R., Sharma V.K., Ho C. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang H., Xia Q., Xiong Z., Li Z., Xiang W., Yuan Y., Liu Y., Li Z. The psychological distress and coping styles in the early stages of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic in the general mainland Chinese population: a web-based survey. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y., Di Y., Ye J., Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol. Health Med. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yaribeygi H., Panahi Y., Sahraei H., Johnston T.P., Sahebkar A. The impact of stress on body function: a review. EXCLI J. 2017; 16 :1057–1072. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-480. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., Ma Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (7):2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2023

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, anxiety, and depression

- Ida Kupcova 1 ,

- Lubos Danisovic 1 ,

- Martin Klein 2 &

- Stefan Harsanyi 1

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 108 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

9422 Accesses

12 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic affected everyone around the globe. Depending on the country, there have been different restrictive epidemiologic measures and also different long-term repercussions. Morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 affected the mental state of every human being. However, social separation and isolation due to the restrictive measures considerably increased this impact. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anxiety and depression prevalence increased by 25% globally. In this study, we aimed to examine the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population.

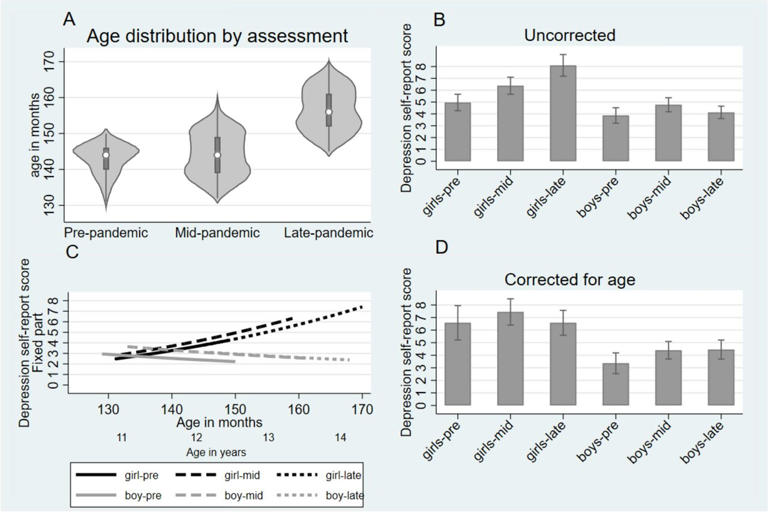

A cross-sectional study using an anonymous online-based 45-question online survey was conducted at Comenius University in Bratislava. The questionnaire comprised five general questions and two assessment tools the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS). The results of the Self-Rating Scales were statistically examined in association with sex, age, and level of education.

A total of 205 anonymous subjects participated in this study, and no responses were excluded. In the study group, 78 (38.05%) participants were male, and 127 (61.69%) were female. A higher tendency to anxiety was exhibited by female participants (p = 0.012) and the age group under 30 years of age (p = 0.042). The level of education has been identified as a significant factor for changes in mental state, as participants with higher levels of education tended to be in a worse mental state (p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Summarizing two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental state of people with higher levels of education tended to feel worse, while females and younger adults felt more anxiety.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The first mention of the novel coronavirus came in 2019, when this variant was discovered in the city of Wuhan, China, and became the first ever documented coronavirus pandemic [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. At this time there was only a sliver of fear rising all over the globe. However, in March 2020, after the declaration of a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), the situation changed dramatically [ 4 ]. Answering this, yet an unknown threat thrust many countries into a psycho-socio-economic whirlwind [ 5 , 6 ]. Various measures taken by governments to control the spread of the virus presented the worldwide population with a series of new challenges to which it had to adjust [ 7 , 8 ]. Lockdowns, closed schools, losing employment or businesses, and rising deaths not only in nursing homes came to be a new reality [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Lack of scientific information on the novel coronavirus and its effects on the human body, its fast spread, the absence of effective causal treatment, and the restrictions which harmed people´s social life, financial situation and other areas of everyday life lead to long-term living conditions with increased stress levels and low predictability over which people had little control [ 12 ].

Risks of changes in the mental state of the population came mainly from external risk factors, including prolonged lockdowns, social isolation, inadequate or misinterpreted information, loss of income, and acute relationship with the rising death toll. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety and depression prevalence increased by 25% globally [ 13 ]. Unemployment specifically has been proven to be also a predictor of suicidal behavior [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. These risk factors then interact with individual psychological factors leading to psychopathologies such as threat appraisal, attentional bias to threat stimuli over neutral stimuli, avoidance, fear learning, impaired safety learning, impaired fear extinction due to habituation, intolerance of uncertainty, and psychological inflexibility. The threat responses are mediated by the limbic system and insula and mitigated by the pre-frontal cortex, which has also been reported in neuroimaging studies, with reduced insula thickness corresponding to more severe anxiety and amygdala volume correlated to anhedonia as a symptom of depression [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Speaking in psychological terms, the pandemic disturbed our core belief, that we are safe in our communities, cities, countries, or even the world. The lost sense of agency and confidence regarding our future diminished the sense of worth, identity, and meaningfulness of our lives and eroded security-enhancing relationships [ 24 ].

Slovakia introduced harsh public health measures in the first wave of the pandemic, but relaxed these measures during the summer, accompanied by a failure to develop effective find, test, trace, isolate and support systems. Due to this, the country experienced a steep growth in new COVID-19 cases in September 2020, which lead to the erosion of public´s trust in the government´s management of the situation [ 25 ]. As a means to control the second wave of the pandemic, the Slovak government decided to perform nationwide antigen testing over two weekends in November 2020, which was internationally perceived as a very controversial step, moreover, it failed to prevent further lockdowns [ 26 ]. In addition, there was a sharp rise in the unemployment rate since 2020, which continued until July 2020, when it gradually eased [ 27 ]. Pre-pandemic, every 9th citizen of Slovakia suffered from a mental health disorder, according to National Statistics Office in 2017, the majority being affective and anxiety disorders. A group of authors created a web questionnaire aimed at psychiatrists, psychologists, and their patients after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Slovakia. The results showed that 86.6% of respondents perceived the pathological effect of the pandemic on their mental status, 54.1% of whom were already treated for affective or anxiety disorders [ 28 ].

In this study, we aimed to examine the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population. This study aimed to assess the symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general public of Slovakia. After the end of epidemiologic restrictive measures (from March to May 2022), we introduced an anonymous online questionnaire using adapted versions of Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [ 29 , 30 ]. We focused on the general public because only a portion of people who experience psychological distress seek professional help. We sought to establish, whether during the pandemic the population showed a tendency to adapt to the situation or whether the anxiety and depression symptoms tended to be present even after months of better epidemiologic situation, vaccine availability, and studies putting its effects under review [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Materials and Methods

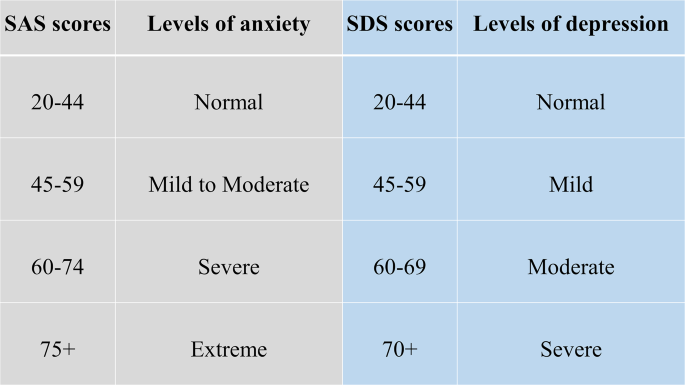

This study utilized a voluntary and anonymous online self-administered questionnaire, where the collected data cannot be linked to a specific respondent. This study did not process any personal data. The questionnaire consisted of 45 questions. The first three were open-ended questions about participants’ sex, age (date of birth was not recorded), and education. Followed by 2 questions aimed at mental health and changes in the will to live. Further 20 and 20 questions consisted of the Zung SAS and Zung SDS, respectively. Every question in SAS and SDS is scored from 1 to 4 points on a Likert-style scale. The scoring system is introduced in Fig. 1 . Questions were presented in the Slovak language, with emphasis on maintaining test integrity, so, if possible, literal translations were made from English to Slovak. The questionnaire was created and designed in Google Forms®. Data collection was carried out from March 2022 to May 2022. The study was aimed at the general population of Slovakia in times of difficult epidemiologic and social situations due to the high prevalence and incidence of COVID-19 cases during lockdowns and social distancing measures. Because of the character of this web-based study, the optimal distribution of respondents could not be achieved.

Categories of Zung SAS and SDS scores with clinical interpretation

During the course of this study, 205 respondents answered the anonymous questionnaire in full and were included in the study. All respondents were over 18 years of age. The data was later exported from Google Forms® as an Excel spreadsheet. Coding and analysis were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0, Armonk, NY, USA). Subject groups were created based on sex, age, and education level. First, sex due to differences in emotional expression. Second, age was a risk factor due to perceived stress and fear of the disease. Last, education due to different approaches to information. In these groups four factors were studied: (1) changes in mental state; (2) affected will to live, or frequent thoughts about death; (3) result of SAS; (4) result of SDS. For SAS, no subject in the study group scored anxiety levels of “severe” or “extreme”. Similarly for SDS, no subject depression levels reached “moderate” or “severe”. Pearson’s chi-squared test(χ2) was used to analyze the association between the subject groups and studied factors. The results were considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical permission was obtained from the local ethics committee (Reference number: ULBGaKG-02/2022). This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines. Due to the anonymous design of the study and by the institutional requirements, written informed consent for participation was not required for this study.

In the study, out of 205 subjects in the study group, 127 (62%) were female and 78 (38%) were male. The average age in the study group was 35.78 years of age (range 19–71 years), with a median of 34 years. In the age group under 30 years of age were 34 (16.6%) subjects, while 162 (79%) were in the range from 31 to 49 and 9 (0.4%) were over 50 years old. 48 (23.4%) participants achieved an education level of lower or higher secondary and 157 (76.6%) finished university or higher. All answers of study participants were included in the study, nothing was excluded.

In Tables 1 and 2 , we can see the distribution of changes in mental state and will to live as stated in the questionnaire. In Table 1 we can see a disproportion in education level and mental state, where participants with higher education tended to feel worse much more than those with lower levels of education. Changes based on sex and age did not show any statistically significant results.

In Table 2 . we can see, that decreased will to live and frequent thoughts about death were only marginally present in the study group, which suggests that coping mechanisms play a huge role in adaptation to such events (e.g. the global pandemic). There is also a possibility that living in times of better epidemiologic situations makes people more likely to forget about the bad past.

Anxiety and depression levels as seen in Tables 3 and 4 were different, where female participants and the age group under 30 years of age tended to feel more anxiety than other groups. No significant changes in depression levels based on sex, age, and education were found.

Compared to the estimated global prevalence of depression in 2017 (3.44%), in 2021 it was approximately 7 times higher (25%) [ 14 ]. Our study did not prove an increase in depression, while anxiety levels and changes in the mental state did prove elevated. No significant changes in depression levels go in hand with the unaffected will to live and infrequent thoughts about death, which were important findings, that did not supplement our primary hypothesis that the fear of death caused by COVID-19 or accompanying infections would enhance personal distress and depression, leading to decreases in studied factors. These results are drawn from our limited sample size and uneven demographic distribution. Suicide ideations rose from 5% pre-pandemic to 10.81% during the pandemic [ 35 ]. In our study, 9.3% of participants experienced thoughts about death and since we did not specifically ask if they thought about suicide, our results only partially correlate with suicidal ideations. However, as these subjects exhibited only moderate levels of anxiety and mild levels of depression, the rise of suicide ideations seems unlikely. The rise in suicidal ideations seemed to be especially true for the general population with no pre-existing psychiatric conditions in the first months of the pandemic [ 36 ]. The policies implemented by countries to contain the pandemic also took a toll on the population´s mental health, as it was reported, that more stringent policies, mainly the social distancing and perceived government´s handling of the pandemic, were related to worse psychological outcomes [ 37 ]. The effects of lockdowns are far-fetched and the increases in mental health challenges, well-being, and quality of life will require a long time to be understood, as Onyeaka et al. conclude [ 10 ]. These effects are not unforeseen, as the global population suffered from life-altering changes in the structure and accessibility of education or healthcare, fluctuations in prices and food insecurity, as well as the inevitable depression of the global economy [ 38 ].

The loneliness associated with enforced social distancing leads to an increase in depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in children in adolescents, with possible long-term sequelae [ 39 ]. The increase in adolescent self-injury was 27.6% during the pandemic [ 40 ]. Similar findings were described in the middle-aged and elderly population, in which both depression and anxiety prevalence rose at the beginning of the pandemic, during the pandemic, with depression persisting later in the pandemic, while the anxiety-related disorders tended to subside [ 41 ]. Medical professionals represented another specific at-risk group, with reported anxiety and depression rates of 24.94% and 24.83% respectively [ 42 ]. The dynamic of psychopathology related to the COVID-19 pandemic is not clear, with studies reporting a return to normal later in 2020, while others describe increased distress later in the pandemic [ 20 , 43 ].

Concerning the general population, authors from Spain reported that lockdowns and COVID-19 were associated with depression and anxiety [ 44 ]. In January 2022 Zhao et al., reported an elevation in hoarding behavior due to fear of COVID-19, while this process was moderated by education and income levels, however, less in the general population if compared to students [ 45 ]. Higher education levels and better access to information could improve persons’ fear of the unknown, however, this fact was not consistent with our expectations in this study, as participants with university education tended to feel worse than participants with lower education. A study on adolescents and their perceived stress in the Czech Republic concluded that girls are more affected by lockdowns. The strongest predictor was loneliness, while having someone to talk to, scored the lowest [ 46 ]. Garbóczy et al. reported elevated perceived stress levels and health anxiety in 1289 Hungarian and international students, also affected by disengagement from home and inadequate coping strategies [ 47 ]. Wathelet et al. conducted a study on French University students confined during the pandemic with alarming results of a high prevalence of mental health issues in the study group [ 48 ]. Our study indicated similar results, as participants in the age group under 30 years of age tended to feel more anxious than others.

In conclusion, we can say that this pandemic changed the lives of many. Many of us, our family members, friends, and colleagues, experienced life-altering events and complicated situations unseen for decades. Our decisions and actions fueled the progress in medicine, while they also continue to impact society on all levels. The long-term effects on adolescents are yet to be seen, while effects of pain, fear, and isolation on the general population are already presenting themselves.

The limitations of this study were numerous and as this was a web-based study, the optimal distribution of respondents could not be achieved, due to the snowball sampling strategy. The main limitation was the small sample size and uneven demographic distribution of respondents, which could impact the representativeness of the studied population and increase the margin of error. Similarly, the limited number of older participants could significantly impact the reported results, as age was an important risk factor and thus an important stressor. The questionnaire omitted the presence of COVID-19-unrelated life-changing events or stressors, and also did not account for any preexisting condition or risk factor that may have affected the outcome of the used assessment scales.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to compliance with institutional guidelines but they are available from the corresponding author (SH) on a reasonable request.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33.

Liu Y-C, Kuo R-L, Shih S-R. COVID-19: the first documented coronavirus pandemic in history. Biomed J. 2020;43:328–33.

Advice for the public on COVID-19 – World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public . Accessed 13 Nov 2022.

Osterrieder A, Cuman G, Pan-Ngum W, Cheah PK, Cheah P-K, Peerawaranun P, et al. Economic and social impacts of COVID-19 and public health measures: results from an anonymous online survey in Thailand, Malaysia, the UK, Italy and Slovenia. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046863.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mofijur M, Fattah IMR, Alam MA, Islam ABMS, Ong HC, Rahman SMA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustainable Prod Consum. 2021;26:343–59.

Article Google Scholar

Vlachos J, Hertegård E, Svaleryd B. The effects of school closures on SARS-CoV-2 among parents and teachers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2020834118.

Ludvigsson JF, Engerström L, Nordenhäll C, Larsson E, Open Schools. Covid-19, and child and teacher morbidity in Sweden. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:669–71.

Miralles O, Sanchez-Rodriguez D, Marco E, Annweiler C, Baztan A, Betancor É, et al. Unmet needs, health policies, and actions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a report from six european countries. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:193–204.

Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P. COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog. 2021;104:368504211019854.

The Lancet null. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020;395:1315.

Lo Coco G, Gentile A, Bosnar K, Milovanović I, Bianco A, Drid P, et al. A cross-country examination on the fear of COVID-19 and the sense of loneliness during the First Wave of COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2586.

COVID-19 pandemic. triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide . Accessed 14 Nov 2022.

Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21:100196.

Hajek A, Sabat I, Neumann-Böhme S, Schreyögg J, Barros PP, Stargardt T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of probable depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in seven countries: longitudinal evidence from the european COvid Survey (ECOS). J Affect Disord. 2022;299:517–24.

Piumatti G, Levati S, Amati R, Crivelli L, Albanese E. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and stress among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Switzerland: the Corona Immunitas Ticino cohort study. Public Health. 2022;206:63–9.

Korkmaz H, Güloğlu B. The role of uncertainty tolerance and meaning in life on depression and anxiety throughout Covid-19 pandemic. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;179:110952.

McIntyre RS, Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113104.

Funkhouser CJ, Klemballa DM, Shankman SA. Using what we know about threat reactivity models to understand mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav Res Ther. 2022;153:104082.

Landi G, Pakenham KI, Crocetti E, Tossani E, Grandi S. The trajectories of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and the protective role of psychological flexibility: a four-wave longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2022;307:69–78.

Holt-Gosselin B, Tozzi L, Ramirez CA, Gotlib IH, Williams LM. Coping strategies, neural structure, and depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in a naturalistic sample spanning clinical diagnoses and subclinical symptoms. Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci. 2021;1:261–71.

McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. The role of psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19: Associations with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. J Context Behav Sci. 2021;19:28–35.

Talkovsky AM, Norton PJ. Negative affect and intolerance of uncertainty as potential mediators of change in comorbid depression in transdiagnostic CBT for anxiety. J Affect Disord. 2018;236:259–65.

Milman E, Lee SA, Neimeyer RA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC. Modeling pandemic depression and anxiety: the mediational role of core beliefs and meaning making. J Affect Disorders Rep. 2020;2:100023.

Sagan A, Bryndova L, Kowalska-Bobko I, Smatana M, Spranger A, Szerencses V, et al. A reversal of fortune: comparison of health system responses to COVID-19 in the Visegrad group during the early phases of the pandemic. Health Policy. 2022;126:446–55.

Holt E. COVID-19 testing in Slovakia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:32.

Stalmachova K, Strenitzerova M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment in transport and telecommunications sectors. Transp Res Procedia. 2021;55:87–94.

Izakova L, Breznoscakova D, Jandova K, Valkucakova V, Bezakova G, Suvada J. What mental health experts in Slovakia are learning from COVID-19 pandemic? Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):459–66.

Rabinčák M, Tkáčová Ľ, VYUŽÍVANIE PSYCHOMETRICKÝCH KONŠTRUKTOV PRE, HODNOTENIE PORÚCH NÁLADY V OŠETROVATEĽSKEJ PRAXI. Zdravotnícke Listy. 2019;7:7.

Google Scholar

Sekot M, Gürlich R, Maruna P, Páv M, Uhlíková P. Hodnocení úzkosti a deprese u pacientů se zhoubnými nádory trávicího traktu. Čes a slov Psychiat. 2005;101:252–7.

Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G, Lustig Y, Balicer RD. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: measurement, causes and impact. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:57–65.

Accorsi EK, Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, Smith ZR, Shang N, Derado G, et al. Association between 3 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and symptomatic infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta Variants. JAMA. 2022;327:639–51.

Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Kohane IS, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet. 2021;398:2093–100.

Magen O, Waxman JG, Makov-Assif M, Vered R, Dicker D, Hernán MA, et al. Fourth dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1603–14.

Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998.

Kok AAL, Pan K-Y, Rius-Ottenheim N, Jörg F, Eikelenboom M, Horsfall M, et al. Mental health and perceived impact during the first Covid-19 pandemic year: a longitudinal study in dutch case-control cohorts of persons with and without depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2022;305:85–93.

Aknin LB, Andretti B, Goldszmidt R, Helliwell JF, Petherick A, De Neve J-E, et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e417–26.

Prochazka J, Scheel T, Pirozek P, Kratochvil T, Civilotti C, Bollo M, et al. Data on work-related consequences of COVID-19 pandemic for employees across Europe. Data Brief. 2020;32:106174.

Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1218–1239e3.

Zetterqvist M, Jonsson LS, Landberg Ã, Svedin CG. A potential increase in adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury during covid-19: a comparison of data from three different time points during 2011–2021. Psychiatry Res. 2021;305:114208.

Mooldijk SS, Dommershuijsen LJ, de Feijter M, Luik AI. Trajectories of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;149:274–80.

Sahebi A, Nejati-Zarnaqi B, Moayedi S, Yousefi K, Torres M, Golitaleb M. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110247.

Stephenson E, O’Neill B, Kalia S, Ji C, Crampton N, Butt DA, et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2022;303:216–22.

Goldberg X, Castaño-Vinyals G, Espinosa A, Carreras A, Liutsko L, Sicuri E et al. Mental health and COVID-19 in a general population cohort in Spain (COVICAT study).Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;:1–12.

Zhao Y, Yu Y, Zhao R, Cai Y, Gao S, Liu Y, et al. Association between fear of COVID-19 and hoarding behavior during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of mental health status. Front Psychol. 2022;13:996486.

Furstova J, Kascakova N, Sigmundova D, Zidkova R, Tavel P, Badura P. Perceived stress of adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown: bayesian multilevel modeling of the Czech HBSC lockdown survey. Front Psychol. 2022;13:964313.

Garbóczy S, Szemán-Nagy A, Ahmad MS, Harsányi S, Ocsenás D, Rekenyi V, et al. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:53.

Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, Baubet T, Habran E, Veerapa E, et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Disorders among University students in France Confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025591.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to provide our appreciation and thanks to all the respondents in this study.