Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Cyber Bullying — Cyberbullying Paper: Justice For Suicide Victims

Cyberbullying Paper: Justice for Suicide Victims

- Categories: Cyber Bullying Mental Health

About this sample

Words: 746 |

Published: Jun 6, 2024

Words: 746 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The ramifications of cyberbullying, inadequacies of current legal frameworks, the imperative of robust measures.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 694 words

5 pages / 2267 words

4 pages / 1757 words

7 pages / 3008 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Cyber Bullying

Communication as we know it is changing all around the world. When it comes to interaction with others many people would rather communicate nonverbally. While some people would argue that social media is actually helping people [...]

In the age of social media and the omnipresence of technology, the issue of cyberbullying has become increasingly prevalent. This critical review aims to explore the film "Cyberbully" and its portrayal of this concerning [...]

Short Summary of Cyber BullyingCyber bullying, a form of bullying that takes place online or through digital devices, has become a pervasive issue in today's society. With the rapid advancement of technology and the widespread [...]

Cyber bullying has become a prevalent issue in today's society, with the rise of social media and digital communication. This form of bullying involves the use of electronic devices to harass, intimidate, or harm others. In this [...]

Bullying has become a major problem, and the use of the internet has just made it worse. Cyber bullying is bullying done by using technology; it can be done with computers, phones, and the biggest one social media. Children need [...]

The psychology of cyberbullies is a multifaceted issue that demands a comprehensive understanding of motives and psychological profiles. By exploring the power dynamics, motives, and psychological characteristics underlying [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- World Psychiatry

- v.22(1); 2023 Feb

Cyberbullying: next‐generation research

Elias aboujaoude.

1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford CA, USA

Matthew W. Savage

2 School of Communication, San Diego State University, San Diego CA, USA

Cyberbullying, or the repetitive aggression carried out over electronic platforms with an intent to harm, is probably as old as the Internet itself. Research interest in this behavior, variably named, is also relatively old, with the first publication on “cyberstalking” appearing in the PubMed database in 1999.

Over two decades later, the broad contours of the problem are generally well understood, including its phenomenology, epidemiology, mental health dimensions, link to suicidality, and disproportionate effects on minorities and individuals with developmental disorders 1 . Much remains understudied, however. Here we call for a “next generation” of research addressing some important knowledge gaps, including those concerning self‐cyberbullying, the bully‐victim phenomenon, the bystander role, the closing age‐based digital divide, cyberbullying subtypes and how they evolve with technology, the cultural specificities of cyberbullying, and especially the management of this behavior.

Defined as the anonymous online posting, sending or otherwise sharing of hurtful content about oneself, “self‐cyberbullying” or “digital self‐harm” has emerged as a new and troubling manifestation of cyberbullying. Rather than a fringe phenomenon, self‐cyberbullying is thought to affect up to 6% of middle‐ and high‐school students 2 . Is this a cry for help by someone who might attempt “real” self‐harm or even suicide if not urgently treated? Is it “attention‐seeking” in nature, meant to drive Internet traffic in a very congested social media landscape where it can be hard to get noticed and where “likes” are the currency of self‐worth? Research is needed to better characterize self‐cyberbullying, including how it relates to depression and offline self‐harm and suicide.

The bully‐victim phenomenon refers to the permeable boundaries between roles that can make it relatively easy for a cyberbullying victim to become a cyberbully and vice versa. Unlike traditional bullying, visible markers of strength are not a requirement in cyberbullying. Assuming the identity of the cyberbully is known, all that the victims need to attack back and become cyberbullies themselves is a digital platform and basic digital know‐how. Do cyberbullying victims feel in any way “empowered” by this permeability, as some do express in clinical settings? And does knowledge that perpetrators can be attacked back have any deterrent effect on them, or is the bi‐directional violence that can ensue an unmitigated race to the bottom that further impairs well‐being?

What of the bystander role? Depending on the platform, the audience witnessing a cyberbullying attack can potentially be limitless – attacks that go viral are an extreme example of this. While this can magnify the humiliation inflicted on the victim, it also introduces the possibility of enlisting bystanders to protect victims and push back against perpetrators. Research examining how to leverage bystanders as part of anti‐cyberbullying interventions would have significant management and public health utility.

Recent scholarship has brought attention to cyberbullying beyond the young age group. What had been called the “digital divide”, which in this context refers to the notion that children and adolescents are more active online and therefore at higher risk, has narrowed to the point where a significant risk of cyberbullying now appears to exist among college students and perhaps adults overall. Cyberbullying is no longer a middle‐ and high‐school problem, as suggested by a 30‐country United Nations‐sponsored survey that recruited nearly 170,000 youth up to 24 years of age and found that 33% of them had been victims of that behavior 3 . To better protect against cyberbullying and implement age‐appropriate interventions, new research should better delineate the upper limits of the high‐risk cyberbullying age bracket, if they exist.

There is also insufficient research into the culturally‐specific dimensions of cyberbullying. Co‐authoring analyses reveal that the most influential cyberbullying scholarship comes from the US, and that the top 5 universities in publication productivity are in the European Union 4 . Given the different relationship to violence across cultures and the diverging definitions of, and reactions to, trauma worldwide, a broader culturally‐centered research perspective is essential for a more thorough understanding of cyberbullying's global impact.

As we “zoom out” and investigate across cultures, we should also “zoom in” on the specific cyberbullying behavior. Are all cyberbullying attacks similar in terms of prevalence, perpetrator and victim profiles, short‐ and long‐term consequences, and management strategies? Several forms of cyberbullying have been identified 5 , but their similarities and differences require elucidation, especially as technology continues to change and new forms emerge. Therefore, future research should compare diverse behaviors, such as cyberstalking, “excluding” (deliberately leaving someone out), “doxing” (revealing sensitive information about the victim), “fraping” (using the victim's social media account to post inappropriate content under the victim's name), “masquerading” (creating a fake identity with which to attack the victim), “flaming” (posting insults against the victim), and sex‐based cyberbullying through the non‐consensual sending of sexual text messages or imagery. To better understand and address cyberbullying, we must explore its existing subtypes – some of which have only been described in blogs – and, as technology evolves, its emerging forms.

Most urgently, the lack of agreement upon “best practices” for the management of cyberbullying must be remedied. Expanding access to psychiatric and psychological care – given the mental health dimension of cyberbullying – is imperative, as is a better understanding of school‐based interventions, which remain the most popular management approach.

Data from school‐based studies suggest that programs which adopt a broad, ecological approach to the school‐wide climate and which include specific actions at the student, teacher and family levels are more effective than those delivered solely through classroom curricula or social skills trainings 6 . However, the best meta‐analytic evidence for school‐based programs demonstrates mostly short‐term effects 7 , while long‐term data suggest small benefits 8 . Further, success appears more likely when programs target cyberbullying specifically as opposed to general violence prevention 7 , and when they are delivered by technology‐savvy content experts as opposed to teachers 8 . Evidence also suggests that programs are most successful when they provide informational support through interactive modalities (e.g., peer tutoring, role playing, group discussion), and when they nurture stakeholder agency (e.g., offer quality teacher training programs, engage parents in program implementation) 9 .

Future research into cyberbullying management should expand on these findings and examine how management interfaces with the legislative process and with law enforcement when it comes to illegal behavior, including privacy breeches and serious threats.

Much has been learned about cyberbullying, but much remains to be explored. The knowledge gaps are all the more challenging given that Internet‐related technologies evolve at a breakneck pace and in a way that reveals new exploitable vulnerabilities. Along with the previously cited statistic that no less than 33% of young people worldwide have been victimized 3 , this should give the field added urgency to “keep up” and investigate some under‐studied areas that are critical to a more nuanced understanding of cyberbullying and its effective management.

Qualitative Methods in School Bullying and Cyberbullying Research: An Introduction to the Special Issue

- Published: 12 August 2022

- Volume 4 , pages 175–179, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Paul Horton 1 &

- Selma Therese Lyng 2

9916 Accesses

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

School bullying research has a long history, stretching all the way back to a questionnaire study undertaken in the USA in the late 1800s (Burk, 1897 ). However, systematic school bullying research began in earnest in Scandinavia in the early 1970s with the work of Heinemann ( 1972 ) and Olweus ( 1978 ). Highlighting the extent to which research on bullying has grown exponentially since then, Smith et al. ( 2021 ) found that there were only 83 articles with the term “bully” in the title or abstract published in the Web of Science database prior to 1989. The numbers of articles found in the following decades were 458 (1990–1999), 1,996 (2000–2009), and 9,333 (2010–2019). Considering cyberbullying more specifically, Smith and Berkkun ( 2017 , cited in Smith et al., 2021 ) conducted a search of Web of Science with the terms “cyber* and bully*; cyber and victim*; electronic bullying; Internet bullying; and online harassment” until the year 2015 and found that while there were no articles published prior to 2000, 538 articles were published between 2000 and 2015, with the number of articles increasing every year (p. 49).

Numerous authors have pointed out that research into school bullying and cyberbullying has predominantly been conducted using quantitative methods, with much less use of qualitative or mixed methods (Hong & Espelage, 2012 ; Hutson, 2018 ; Maran & Begotti, 2021 ; Smith et al., 2021 ). In their recent analysis of articles published between 1976 and 2019 (in WoS, with the search terms “bully*; victim*; cyberbullying; electronic bullying; internet bullying; and online harassment”), Smith et al. ( 2021 , pp. 50–51) found that of the empirical articles selected, more than three-quarters (76.3%) were based on quantitative data, 15.4% were based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, and less than one-tenth (8.4%) were based on qualitative data alone. What is more, they found that the proportion of articles based on qualitative or mixed methods has been decreasing over the past 15 years (Smith et al., 2021 ). While the search criteria excluded certain types of qualitative studies (e.g., those published in books, doctoral theses, and non-English languages), this nonetheless highlights the extent to which qualitative research findings risk being overlooked in the vast sea of quantitative research.

School bullying and cyberbullying are complex phenomena, and a range of methodological approaches is thus needed to understand their complexity (Pellegrini & Bartini, 2000 ; Thornberg, 2011 ). Indeed, over-relying on quantitative methods limits understanding of the contexts and experiences of bullying (Hong & Espelage, 2012 ; Patton et al., 2017 ). Qualitative methods are particularly useful for better understanding the social contexts, processes, interactions, experiences, motivations, and perspectives of those involved (Hutson, 2018 ; Patton et al., 2017 ; Thornberg, 2011 ; Torrance, 2000 ).

Smith et al. ( 2021 ) suggest that the “continued emphasis on quantitative studies may be due to increasingly sophisticated methods such as structural equation modeling … network analysis … time trend analyses … latent profile analyses … and multi-polygenic score approaches” (p. 56). However, the authors make no mention of the range or sophistication of methods used in qualitative studies. Although there are still proportionately few qualitative studies of school bullying and cyberbullying in relation to quantitative studies, and this gap appears to be increasing, qualitative studies have utilized a range of qualitative data collection methods. These methods have included but are not limited to ethnographic fieldwork and participant observations (e.g., Eriksen & Lyng, 2018 ; Gumpel et al., 2014 ; Horton, 2019 ), digital ethnography (e.g., Rachoene & Oyedemi, 2015 ; Sylwander, 2019 ), meta-ethnography (e.g., Dennehy et al., 2020 ; Moretti & Herkovits, 2021 ), focus group interviews (e.g., Odenbring, 2022 ; Oliver & Candappa, 2007 ; Ybarra et al., 2019 ), semi-structured group and individual interviews (e.g., Forsberg & Thornberg, 2016 ; Lyng, 2018 ; Mishna et al., 2005 ; Varjas et al., 2013 ), vignettes (e.g., Jennifer & Cowie, 2012 ; Khanolainen & Semenova, 2020 ; Strindberg et al., 2020 ), memory work (e.g., Johnson et al., 2014 ; Malaby, 2009 ), literature studies (e.g., Lopez-Ropero, 2012 ; Wiseman et al., 2019 ), photo elicitation (e.g., Ganbaatar et al., 2021 ; Newman et al., 2006 ; Walton & Niblett, 2013 ), photostory method (e.g., Skrzypiec et al., 2015 ), and other visual works produced by children and young people (e.g., Bosacki et al., 2006 ; Gillies-Rezo & Bosacki, 2003 ).

This body of research has also included a variety of qualitative data analysis methods, such as grounded theory (e.g., Allen, 2015 ; Bjereld, 2018 ; Thornberg, 2018 ), thematic analysis (e.g., Cunningham et al., 2016 ; Forsberg & Horton, 2022 ), content analysis (e.g., Temko, 2019 ; Wiseman & Jones, 2018 ), conversation analysis (e.g., Evaldsson & Svahn, 2012 ; Tholander, 2019 ), narrative analysis (e.g., Haines-Saah et al., 2018 ), interpretative phenomenological analysis (e.g., Hutchinson, 2012 ; Tholander et al., 2020 ), various forms of discourse analysis (e.g., Ellwood & Davies, 2010 ; Hepburn, 1997 ; Ringrose & Renold, 2010 ), including discursive psychological analysis (e.g., Clarke et al., 2004 ), and critical discourse analysis (e.g., Barrett & Bound, 2015 ; Bethune & Gonick, 2017 ; Horton, 2021 ), as well as theoretically informed analyses from an array of research traditions (e.g., Davies, 2011 ; Jacobson, 2010 ; Søndergaard, 2012 ; Walton, 2005 ).

In light of the growing volume and variety of qualitative studies during the past two decades, we invited researchers to discuss and explore methodological issues related to their qualitative school bullying and cyberbullying research. The articles included in this special issue of the International Journal of Bullying Prevention discuss different qualitative methods, reflect on strengths and limitations — possibilities and challenges, and suggest implications for future qualitative and mixed-methods research.

Included Articles

Qualitative studies — focusing on social, relational, contextual, processual, structural, and/or societal factors and mechanisms — have formed the basis for several contributions during the last two decades that have sought to expand approaches to understanding and theorizing the causes of cyber/bullying. Some have also argued the need for expanding the commonly used definition of bullying, based on Olweus ( 1993 ) (e.g., Allen, 2015 ; Ellwood & Davies, 2010 Goldsmid & Howie, 2014 ; Ringrose & Rawlings, 2015 ; Søndergaard, 2012 ; Walton, 2011 ). In the first article of the special issue, Using qualitative methods to measure and understand key features of adolescent bullying: A call to action , Natalie Spadafora, Anthony Volk, and Andrew Dane instead discuss the usefulness of qualitative methods for improving measures and bettering our understanding of three specific key definitional features of bullying. Focusing on the definition put forward by Volk et al. ( 2014 ), they discuss the definitional features of power imbalance , goal directedness (replacing “intent to harm” in order not to assume conscious awareness, and to include a wide spectrum of goals that are intentionally and strategically pursued by bullies), and harmful impact (replacing “negative actions” in order to focus on the consequences for the victim, as well as circumventing difficult issues related to “repetition” in the traditional definition).

Acknowledging that these three features are challenging to capture using quantitative methods, Spadafora, Volk, and Dane point to existing qualitative studies that shed light on the features of power imbalance, goal directedness and harmful impact in bullying interactions — and put forward suggestions for future qualitative studies. More specifically, the authors argue that qualitative methods, such as focus groups, can be used to investigate the complexity of power relations at not only individual, but also social levels. They also highlight how qualitative methods, such as diaries and autoethnography, may help researchers gain a better understanding of the motives behind bullying behavior; from the perspectives of those engaging in it. Finally, the authors demonstrate how qualitative methods, such as ethnographic fieldwork and semi-structured interviews, can provide important insights into the harmful impact of bullying and how, for example, perceived harmfulness may be connected to perceived intention.

In the second article, Understanding bullying and cyberbullying through an ecological systems framework: The value of qualitative interviewing in a mixed methods approach , Faye Mishna, Arija Birze, and Andrea Greenblatt discuss the ways in which utilizing qualitative interviewing in mixed method approaches can facilitate greater understanding of bullying and cyberbullying. Based on a longitudinal and multi-perspective mixed methods study of cyberbullying, the authors demonstrate not only how qualitative interviewing can augment quantitative findings by examining process, context and meaning for those involved, but also how qualitative interviewing can lead to new insights and new areas of research. They also show how qualitative interviewing can help to capture nuances and complexity by allowing young people to express their perspectives and elaborate on their answers to questions. In line with this, the authors also raise the importance of qualitative interviewing for providing young people with space for self-reflection and learning.

In the third article, Q methodology as an innovative addition to bullying researchers’ methodological repertoire , Adrian Lundberg and Lisa Hellström focus on Q methodology as an inherently mixed methods approach, producing quantitative data from subjective viewpoints, and thus supplementing more mainstream quantitative and qualitative approaches. The authors outline and exemplify Q methodology as a research technique, focusing on the central feature of Q sorting. The authors further discuss the contribution of Q methodology to bullying research, highlighting the potential of Q methodology to address challenges related to gaining the perspectives of hard-to-reach populations who may either be unwilling or unable to share their personal experiences of bullying. As the authors point out, the use of card sorting activities allows participants to put forward their subjective perspectives, in less-intrusive settings for data collection and without disclosing their own personal experiences. The authors also illustrate how the flexibility of Q sorting can facilitate the participation of participants with limited verbal literacy and/or cognitive function through the use of images, objects or symbols. In the final part of the paper, Lundberg and Hellström discuss implications for practice and suggest future directions for using Q methodology in bullying and cyberbullying research, particularly with hard-to-reach populations.

In the fourth article, The importance of being attentive to social processes in school bullying research: Adopting a constructivist grounded theory approach , Camilla Forsberg discusses the use of constructivist grounded theory (CGT) in her research, focusing on social structures, norms, and processes. Forsberg first outlines CGT as a theory-methods package that is well suited to meet the call for more qualitative research on participants’ experiences and the social processes involved in school bullying. Forsberg emphasizes three key focal aspects of CGT, namely focus on participants’ main concerns; focus on meaning, actions, and processes; and focus on symbolic interactionism. She then provides examples and reflections from her own ethnographic and interview-based research, from different stages of the research process. In the last part of the article, Forsberg argues that prioritizing the perspectives of participants is an ethical stance, but one which comes with a number of ethical challenges, and points to ways in which CGT is helpful in dealing with these challenges.

In the fifth article, A qualitative meta-study of youth voice and co-participatory research practices: Informing cyber/bullying research methodologies , Deborah Green, Carmel Taddeo, Deborah Price, Foteini Pasenidou, and Barbara Spears discuss how qualitative meta-studies can be used to inform research methodologies for studying school bullying and cyberbullying. Drawing on the findings of five previous qualitative studies, and with a transdisciplinary and transformative approach, the authors illustrate and exemplify how previous qualitative research can be analyzed to gain a better understanding of the studies’ collective strengths and thus consider the findings and methods beyond the original settings where the research was conducted. In doing so, the authors highlight the progression of youth voice and co-participatory research practices, the centrality of children and young people to the research process and the enabling effect of technology — and discuss challenges related to ethical issues, resource and time demands, the role of gatekeepers, and common limitations of qualitative studies on youth voice and co-participatory research practices.

Taken together, the five articles illustrate the diversity of qualitative methods used to study school bullying and cyberbullying and highlight the need for further qualitative research. We hope that readers will find the collection of articles engaging and that the special issue not only gives impetus to increased qualitative focus on the complex phenomena of school bullying and cyberbullying but also to further discussions on both methodological and analytical approaches.

Allen, K. A. (2015). “We don’t have bullying, but we have drama”: Understandings of bullying and related constructs within the school milieu of a U.S. high school. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment , 25 (3), 159–181.

Barrett, B., & Bound, A. M. (2015). A critical discourse analysis of No Promo Homo policies in US schools. Educational Studies, 51 (4), 267–283.

Article Google Scholar

Bethune, J., & Gonick, M. (2017). Schooling the mean girl: A critical discourse analysis of teacher resource materials. Gender and Education, 29 (3), 389–404.

Bjereld, Y. (2018). The challenging process of disclosing bullying victimization: A grounded theory study from the victim’s point of view. Journal of Health Psychology, 23 (8), 1110–1118.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bosacki, S. L., Marini, Z. A., & Dane, A. V. (2006). Voices from the classroom: Pictorial and narrative representations of children’s bullying experiences. Journal of Moral Education, 35 (2), 231–245.

Burk, F. L. (1897). Teasing and Bullying. Pedagogical Seminary, 4 (3), 336–371.

Clarke, V., Kitzinger, C., & Potter, J. (2004). ‘Kids are just cruel anyway’: Lesbian and gay parents’ talk about homophobic bullying. British Journal of Social Psychology, 43 (4), 531–550.

Cunningham, C. E., Mapp, C., Rimas, H., Cunningham, S. M., Vaillancourt, T., & Marcus, M. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of students. Psychology of Violence, 6 (4), 596–606.

Davies, B. (2011). Bullies as guardians of the moral order or an ethic of truths? Children & Society, 25 , 278–286.

Dennehy, R., Meaney, S., Walsh, K. A., Sinnott, C., Cronin, M., & Arensman, E. (2020). Young people’s conceptualizations of the nature of cyberbullying: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51 , 101379.

Ellwood, C., & Davies, B. (2010). Violence and the moral order in contemporary schooling: A discursive analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7 (2), 85–98.

Eriksen, I. M., & Lyng, S. T. (2018). Relational aggression among boys: Blind spots and hidden dramas. Gender and Education, 30 (3), 396–409.

Evaldsson, A. -C., Svahn, J. (2012). School bullying and the micro-politics of girls’ gossip disputes. In S. Danby & M. Theobald (Eds.). Disputes in everyday life: Social and moral orders of children and young people (Sociological Studies of Children and Youth, Vol. 15) (pp. 297–323). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Forsberg, C., & Horton, P. (2022). ‘Because I am me’: School bullying and the presentation of self in everyday school life. Journal of Youth Studies, 25 (2), 136–150.

Forsberg, C., & Thornberg, R. (2016). The social ordering of belonging: Children’s perspectives on bullying. International Journal of Educational Research, 78 , 13–23.

Ganbaatar, D., Vaughan, C., Akter, S., & Bohren, M. A. (2021). Exploring the identities and experiences of young queer people in Mongolia using visual research methods. Culture, Health & Sexuality . Advance Online Publication: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.1998631

Gillies-Rezo, S., & Bosacki, S. (2003). Invisible bruises: Kindergartners’ perceptions of bullying. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 8 (2), 163–177.

Goldsmid, S., & Howie, P. (2014). Bullying by definition: An examination of definitional components of bullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 19 (2), 210–225.

Gumpel, T. P., Zioni-Koren, V., & Bekerman, Z. (2014). An ethnographic study of participant roles in school bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 40 (3), 214–228.

Haines-Saah, R. J., Hilario, C. T., Jenkins, E. K., Ng, C. K. Y., & Johnson, J. L. (2018). Understanding adolescent narratives about “bullying” through an intersectional lens: Implications for youth mental health interventions. Youth & Society, 50 (5), 636–658.

Heinemann, P. -P. (1972). Mobbning – gruppvåld bland barn och vuxna [Bullying – group violence amongst children and adults]. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

Hepburn, A. (1997). Discursive strategies in bullying talk. Education and Society, 15 (1), 13–31.

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of mixed methods research on bullying and peer victimization in school. Educational Review, 64 (1), 115–126.

Horton, P. (2019). The bullied boy: Masculinity, embodiment, and the gendered social-ecology of Vietnamese school bullying. Gender and Education, 31 (3), 394–407.

Horton, P. (2021). Building walls: Trump election rhetoric, bullying and harassment in US schools. Confero: Essays on Education, Philosophy and Politics , 8 (1), 7–32.

Hutchinson, M. (2012). Exploring the impact of bullying on young bystanders. Educational Psychology in Practice, 28 (4), 425–442.

Hutson, E. (2018). Integrative review of qualitative research on the emotional experience of bullying victimization in youth. The Journal of School Nursing, 34 (1), 51–59.

Jacobson, R. B. (2010). A place to stand: Intersubjectivity and the desire to dominate. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 29 , 35–51.

Jennifer, D., & Cowie, H. (2012). Listening to children’s voices: Moral emotional attributions in relation to primary school bullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17 (3–4), 229–241.

Johnson, C. W., Singh, A. A., & Gonzalez, M. (2014). “It’s complicated”: Collective memories of transgender, queer, and questioning youth in high school. Journal of Homosexuality, 61 (3), 419–434.

Khanolainen, D., & Semenova, E. (2020). School bullying through graphic vignettes: Developing a new arts-based method to study a sensitive topic. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1–15.

Lopez-Ropero, L. (2012). ‘You are a flaw in the pattern’: Difference, autonomy and bullying in YA fiction. Children’s Literature in Education, 43 , 145–157.

Lyng, S. T. (2018). The social production of bullying: Expanding the repertoire of approaches to group dynamics. Children & Society, 32 (6), 492–502.

Malaby, M. (2009). Public and secret agents: Personal power and reflective agency in male memories of childhood violence and bullying. Gender and Education, 21 (4), 371–386.

Maran, D. A., & Begotti, T. (2021). Measurement issues relevant to qualitative studies. In P. K. Smith & J. O’Higgins Norman (Eds.). The Wiley handbook of bullying (pp. 233–249). John Wiley & Sons.

Mishna, F., Scarcello, I., Pepler, D., & Wiener, J. (2005). Teachers’ understandings of bullying. Canadian Journal of Education, 28 (4), 718–738.

Moretti, C., & Herkovits, D. (2021). Victims, perpetrators, and bystanders: A meta-ethnography of roles in cyberbullying. Cad. Saúde Pública, 37 (4), e00097120.

Newman, M., Woodcock, A., & Dunham, P. (2006). ‘Playtime in the borderlands’: Children’s representations of school, gender and bullying through photographs and interviews. Children’s Geographies, 4 (3), 289–302.

Odenbring, Y. (2022). Standing alone: Sexual minority status and victimisation in a rural lower secondary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26 (5), 480–494.

Oliver, C., & Candappa, M. (2007). Bullying and the politics of ‘telling.’ Oxford Review of Education, 33 (1), 71–86.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools – Bullies and the whipping boys . Wiley.

Google Scholar

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying in school: What we know and what we can do . Blackwell.

Patton, D. U., Hong, J. S., Patel, S., & Kral, M. J. (2017). A systematic review of research strategies used in qualitative studies on school bullying and victimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18 (1), 3–16.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Bartini, M. (2000). A longitudinal study of bullying, victimization, and peer affiliation during the transition from primary school to middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 37 (3), 699–725.

Rachoene, M., & Oyedemi, T. (2015). From self-expression to social aggression: Cyberbullying culture among South African youth on Facebook. Communicatio: South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research , 41 (3), 302–319.

Ringrose, J., & Rawlings, V. (2015). Posthuman performativity, gender and ‘school bullying’: Exploring the material-discursive intra-actions of skirts, hair, sluts, and poofs. Confero: Essays on Education, Philosophy and Politics , 3 (2), 80–119.

Ringrose, J., & Renold, E. (2010). Normative cruelties and gender deviants: The performative effects of bully discourses for girls and boys in school. British Educational Research Journal, 36 (4), 573–596.

Skrzypiec, G., Slee, P., & Sandhu, D. (2015). Using the PhotoStory method to understand the cultural context of youth victimization in the Punjab. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 7 (1), 52–68.

Smith, P., Robinson, S., & Slonje, R. (2021). The school bullying research program: Why and how it has developed. In P. K. Smith & J. O’Higgins Norman (Eds.). The Wiley handbook of bullying (pp. 42–59). John Wiley & Sons.

Smith, P. K., & Berkkun, F. (2017). How research on school bullying has developed. In C. McGuckin & L. Corcoran (Eds.), Bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, psychological impacts and intervention strategies (pp. 11–27). Hauppage, NY: Nova Science.

Strindberg, J., Horton, P., & Thornberg, R. (2020). The fear of being singled out: Pupils’ perspectives on victimization and bystanding in bullying situations. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41 (7), 942–957.

Sylwander, K. R. (2019). Affective atmospheres of sexualized hate among youth online: A contribution to bullying and cyberbullying research on social atmosphere. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1 , 269–284.

Søndergaard, D. M. (2012). Bullying and social exclusion anxiety in schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33 (3), 355–372.

Temko, E. (2019). Missing structure: A critical content analysis of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Children & Society, 33 (1), 1–12.

Tholander, M. (2019). The making and unmaking of a bullying victim. Interchange, 50 , 1–23.

Tholander, M., Lindberg, A., & Svensson, D. (2020). “A freak that no one can love”: Difficult knowledge in testimonials on school bullying. Research Papers in Education, 35 (3), 359–377.

Thornberg, R. (2011). ‘She’s weird!’ – The social construction of bullying in school: A review of qualitative research. Children & Society, 25 , 258–267.

Thornberg, R. (2018). School bullying and fitting into the peer landscape: A grounded theory field study. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39 (1), 144–158.

Torrance, D. A. (2000). Qualitative studies into bullying within special schools. British Journal of Special Education, 27 (1), 16–21.

Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Kiperman, S., & Howard, A. (2013). Technology hurts? Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth perspectives of technology and cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 12 (1), 27–44.

Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A Theoretical Redefinition, Developmental Review, 34 (4), 327–343.

Walton, G. (2005). Bullying widespread. Journal of School Violence, 4 (1), 91–118.

Walton, G. (2011). Spinning our wheels: Reconceptualizing bullying beyond behaviour-focused Approaches. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education , 32 (1), 131–144.

Walton, G., & Niblett, B. (2013). Investigating the problem of bullying through photo elicitation. Journal of Youth Studies, 16 (5), 646–662.

Wiseman, A. M., & Jones, J. S. (2018). Examining depictions of bullying in children’s picturebooks: A content analysis from 1997 to 2017. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 32 (2), 190–201.

Wiseman, A. M., Vehabovic, N., & Jones, J. S. (2019). Intersections of race and bullying in children’s literature: Transitions, racism, and counternarratives. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47 , 465–474.

Ybarra, M. L., Espelage, D. L., Valido, A., Hong, J. S., & Prescott, T. L. (2019). Perceptions of middle school youth about school bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 75 , 175–187.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the authors for sharing their work; Angela Mazzone, James O’Higgins Norman, and Sameer Hinduja for their editorial assistance; and Dorte Marie Søndergaard on the editorial board for suggesting a special issue on qualitative research in the journal.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning (IBL), Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Paul Horton

Work Research Institute (WRI), Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Selma Therese Lyng

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul Horton .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Horton, P., Lyng, S.T. Qualitative Methods in School Bullying and Cyberbullying Research: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 4 , 175–179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00139-5

Download citation

Published : 12 August 2022

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00139-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Instagram now lets teens limit interactions to their ‘Close Friends’ group to combat harassment

In a bid to combat harassment on its platform, Instagram said on Thursday it is expanding the scope of its “Limits” tool specifically for teenagers that would let them restrict unwanted interactions with people. Once they turn the feature on, teens will only be able to see comments, messages, story replies, tags, and mentions from their “Close Friends” group, and interactions from other accounts will be muted.

The company originally debuted the Limits feature as a test in 2021 after English footballers Bukayo Saka, Marcus Rashford, and Jadon Sancho were harassed online following the English team’s loss to Italy in the Euro 2020 finals. Everyone can use Limits right now, though it only lets you restrict interactions with people you follow, in addition to long-standing followers.

The feature has now been tuned for teens with the “Close Friends” setting by default, and Instagram says it is specifically meant to protect people from bullying and harassment. Accounts that aren’t part of a person’s “Close Friends” group can still interact with them, but their activity won’t show up in the feed.

Alternatively, teens can limit interactions with recent followers — accounts that started following them in the past week or accounts that they don’t follow.

In addition, the company is adding new functionality to its “Restrict” feature that lets you limit interactions from specific accounts without blocking them. Instagram will hide all comments from restricted accounts, and they won’t be able to tag or mention you.

Earlier this year, Meta rolled out new restrictions preventing anyone over 18 from messaging teenagers who don’t follow them. In April, the company introduced a feature that would blur nudity in Instagram DMs for teens .

This is a “good faith” move by Meta, which has been facing scrutiny over teen safety in multiple regions. Last October, over 40 U.S. states sued Meta, alleging its product design impacts kids’ mental health . Earlier this month, the European Union opened an investigation against Facebook and Instagram over their addictive design and their negative impact on minors’ mental health .

More TechCrunch

Get the industry’s biggest tech news, techcrunch daily news.

Every weekday and Sunday, you can get the best of TechCrunch’s coverage.

Startups Weekly

Startups are the core of TechCrunch, so get our best coverage delivered weekly.

TechCrunch Fintech

The latest Fintech news and analysis, delivered every Tuesday.

TechCrunch Mobility

TechCrunch Mobility is your destination for transportation news and insight.

Anterior grabs $20M from NEA to expedite health insurance approvals with AI

Anterior, a company that uses AI to expedite health insurance approval for medical procedures, has raised a $20 million Series A round at a $95 million post-money valuation led by…

How India’s most valuable startup ended up being worth nothing

Welcome back to TechCrunch’s Week in Review — TechCrunch’s newsletter recapping the week’s biggest news. Want it in your inbox every Saturday? Sign up here. There’s more bad news for…

Bereave wants employers to suck a little less at navigating death

If death and taxes are inevitable, why are companies so prepared for taxes, but not for death? “I lost both of my parents in college, and it didn’t initially spark…

Apple needs to focus on making AI useful, not flashy

Google and Microsoft have made their developer conferences a showcase of their generative AI chops, and now all eyes are on next week’s Worldwide Developers Conference, which is expected to…

Deal Dive: Human Native AI is building the marketplace for AI training licensing deals

AI systems and large language models need to be trained on massive amounts of data to be accurate but they shouldn’t train on data that they don’t have the rights…

Wazer Pro is making desktop water jetting more affordable

Before Wazer came along, “water jet cutting” and “affordable” didn’t belong in the same sentence. That changed in 2016, when the company launched the world’s first desktop water jet cutter,…

Autonomy’s Mike Lynch acquitted after US fraud trial brought by HP

Former Autonomy chief executive Mike Lynch issued a statement Thursday following his acquittal of criminal charges, ending a 13-year legal battle with Hewlett-Packard that became one of Silicon Valley’s biggest…

Featured Article

What Snowflake isn’t saying about its customer data breaches

As another Snowflake customer confirms a data breach, the cloud data company says its position “remains unchanged.”

Rippling bans former employees who work at competitors like Deel and Workday from its tender offer stock sale

Investor demand has been so strong for Rippling’s shares that it is letting former employees particpate in its tender offer. With one exception.

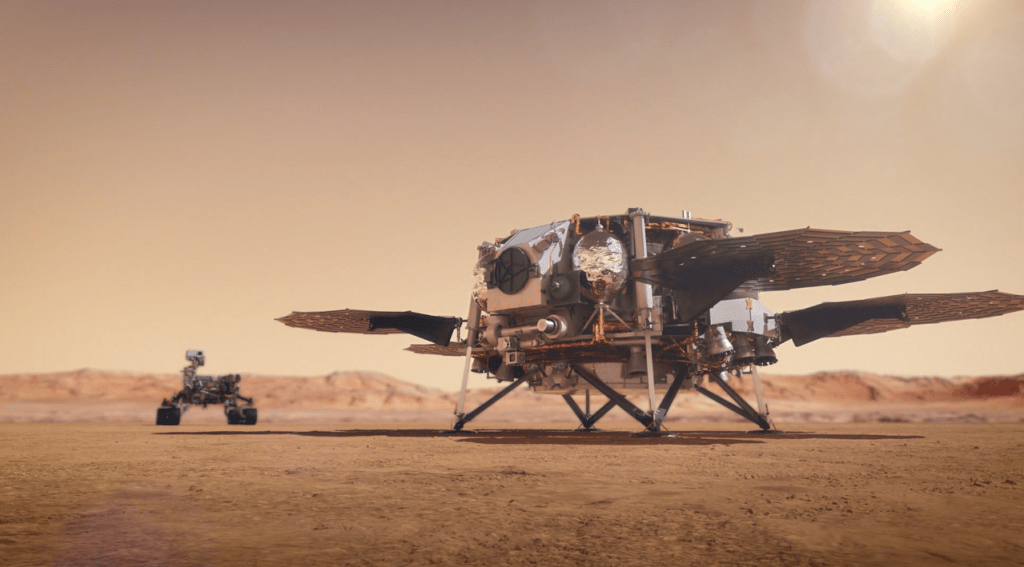

NASA puts $10M down on Mars sample return proposals from Blue Origin, SpaceX and others

It turns out the space industry has a lot of ideas on how to improve NASA’s $11 billion, 15-year plan to collect and return samples from Mars. Seven of these…

In 2024, many Y Combinator startups only want tiny seed rounds — but there’s a catch

When Bowery Capital general partner Loren Straub started talking to a startup from the latest Y Combinator accelerator batch a few months ago, she thought it was strange that the company didn’t have a lead investor for the round it was raising. Even stranger, the founders didn’t seem to be…

Watch Apple kick off WWDC 2024 right here

The keynote will be focused on Apple’s software offerings and the developers that power them, including the latest versions of iOS, iPadOS, macOS, tvOS, visionOS and watchOS.

Startups Weekly: Ups, downs, and silver linings

Welcome to Startups Weekly — Haje’s weekly recap of everything you can’t miss from the world of startups. Anna will be covering for him this week. Sign up here to…

BlackRock has slashed the value of stake in Byju’s, once worth $22 billion, to zero

HSBC and BlackRock estimate that the Indian edtech giant Byju’s, once valued at $22 billion, is now worth nothing.

Apple’s generative AI offering might not work with the standard iPhone 15

Apple is set to board the runaway locomotive that is generative AI at next week’s World Wide Developer Conference. Reports thus far have pointed to a partnership with OpenAI that…

LinkedIn to limit targeted ads in EU after complaint over sensitive data use

LinkedIn has confirmed it will no longer allow advertisers to target users based on data gleaned from their participation in LinkedIn Groups. The move comes more than three months after…

Startup Battlefield 200 applications due Monday

Founders: Need plans this weekend? What better way to spend your time than applying to this year’s Startup Battlefield 200 at TechCrunch Disrupt. With Monday’s deadline looming, this is a…

Novel battery manufacturer EnerVenue is raising $515M, per filing

The company is in the process of building a gigawatt-scale factory in Kentucky to produce its nickel-hydrogen batteries.

Meta quietly rolls out Communities on Messenger

Meta is quietly rolling out a new “Communities” feature on Messenger, the company confirmed to TechCrunch. The feature is designed to help organizations, schools and other private groups communicate in…

Siri and Google Assistant look to generative AI for a new lease on life

Voice assistants in general are having an existential moment, and generative AI is poised to be the logical successor.

Bain to take K-12 education software provider PowerSchool private in $5.6B deal

Education software provider PowerSchool is being taken private by investment firm Bain Capital in a $5.6 billion deal.

Shopify acquires Threads (no, not that one)

Shopify has acquired Threads.com, the Sequoia-backed Slack alternative, Threads said on its website. The companies didn’t disclose the terms of the deal but said that the Threads.com team will join…

Bangladeshi police agents accused of selling citizens’ personal information on Telegram

Two senior police officials in Bangladesh are accused of collecting and selling citizens’ personal information to criminals on Telegram.

Carta’s valuation to be cut by $6.5 billion in upcoming secondary sale

Carta, a once-high-flying Silicon Valley startup that loudly backed away from one of its businesses earlier this year, is working on a secondary sale that would value the company at…

Boeing’s Starliner overcomes leaks and engine trouble to dock with ‘the big city in the sky’

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft has successfully delivered two astronauts to the International Space Station, a key milestone in the aerospace giant’s quest to certify the capsule for regular crewed missions. Starliner…

Rivian’s path to survival is now remarkably clear

Rivian needs to sell its new revamped vehicles at a profit in order to sustain itself long enough to get to the cheaper mass market R2 SUV on the road.

What to expect from WWDC 2024: iOS 18, macOS 15 and so much AI

Apple is hoping to make WWDC 2024 memorable as it finally spells out its generative AI plans.

What to expect from Apple’s AI-powered iOS 18 at WWDC 2024

As WWDC 2024 nears, all sorts of rumors and leaks have emerged about what iOS 18 and its AI-powered apps and features have in store.

Apple’s Design Awards highlight indies and startups

Apple’s annual list of what it considers the best and most innovative software available on its platform is turning its attention to the little guy.

Meta rolls out Meta Verified for WhatsApp Business users in Brazil, India, Indonesia and Colombia

Meta launched its Meta Verified program today along with other features, such as the ability to call large businesses and custom messages.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

When Anti-Fur Protesters Are at the Front Door

The designer Marc Jacobs said he was bullied into renouncing fur — which he claims his brand stopped using in 2018 — after activists targeted his employees.

By Jessica Testa and Vanessa Friedman

A new frontier has opened in fashion’s fur wars, as protesters targeted the homes of more than a dozen employees of Marc Jacobs in recent months, using signs, noisemakers and fake blood in an effort to force the designer to officially renounce the use of fur in his collections.

Over the weekend, Mr. Jacobs accused the protesters of “bullying” in a statement on Instagram , but averred: His brand “does not work in, use or sell fur, nor will we in the future.” He also emphasized that he had not used fur in any of his own brand’s collections since 2018.

“This organization has made it clear that they will not stop their violence toward Marc Jacobs unless they get the statement they want,” Mr. Jacobs wrote. “While I don’t condone the behavior of this organization, I will always do what I can to protect, honor and respect the lives and well-being of the people I work with.”

The organization referenced by Mr. Jacobs is the Coalition to Abolish the Fur Trade, or CAFT, a group that selects targets and disseminates information and resources to anti-fur activists on the ground.

“We were ecstatic,” Matthew Klein, the executive director of CAFT USA, said of Mr. Jacobs’s statement, though he disputed the description of the protests as violent: “Home protest is protected by the First Amendment, and has a long and proud history of use by the labor and civil rights movements.”

According to Mr. Klein, CAFT has been protesting Marc Jacobs since June 2023 — a few months after the company collaborated on a runway show with the Italian brand Fendi.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Cyberbullying exerts negative effects on many aspects of young people's lives, including personal privacy invasion and psychological disorders. The influence of cyberbullying may be worse than traditional bullying as perpetrators can act anonymously and connect easily with children and adolescents at any time .

bullying incident and 25% an educator2 (Patchin, 2018). Additionally, the Pew Research Center found that 60% of teenagers feel that parents are doing an excellent or good job in addressing cyberbullying — a statistic significantly higher than positive assessments of, for instance, social media companies (33%) or elected officials (20%) (Anderson,

While some researchers view cyberbullying as not profoundly distinct from traditional bullying (Olweus & Limber, 2018; see Vaillancourt, Faris, & Mishna, 2017), the nuanced differences between the two suggest that generalizing findings from traditional bullying to cyberbullying may be inadequate (Savage & Tokunaga, 2017).Growing evidence reveals that many facets of cyberbullying—from its ...

cyberbullying, in which individuals or groups of individuals use the media to inflict emotional distress on. other individuals (Bocij 2004). According to a rece nt study of 743 teenager s and ...

Recognized as complex and relational, researchers endorse a systems/social-ecological framework in examining bullying and cyberbullying. According to this framework, bullying and cyberbullying are examined across the nested social contexts in which youth live—encompassing individual features; relationships including family, peers, and educators; and ecological conditions such as digital ...

Cyberbullying could have enormous negative impacts on those who experience it. In addition to the. damage to behaviors, mental hea lth, and emotional development also affected the victims' future ...

ABSTRACT. Bullying is a topic of international interest that attracts researchers from various disciplinary areas, including education. This bibliometric study aims to map out the landscape of educational research on bullying and cyberbullying, by performing analyses on a set of Web of Science Core Collection-indexed documents published between 1991-2020.

entitled 'New bottle but old wine: A research of cyberbullying in schools', shows that 54% of. the 177 seventh grade students in Canada had been bullied offline, and 25% had been bullied ...

Cyberbullying has most negatively influenced youth and adolescents in the social media space. Today, Cyberbullying, a psycho-social-digital phenomenon with roots in traditional bullying, is a global problem affecting primarily school children, adolescents, and vulnerable adults (Nixon, 2014, UNICEF, 2019, Zhu et al., 2021).

1. Introduction. Cyberbullying is an emerging societal issue in the digital era [1, 2].The Cyberbullying Research Centre [3] conducted a nationwide survey of 5700 adolescents in the US and found that 33.8 % of the respondents had been cyberbullied and 11.5 % had cyberbullied others.While cyberbullying occurs in different online channels and platforms, social networking sites (SNSs) are fertile ...

Defining verbal, social, physical, and cyberbullying victimization. Bullying occurs when someone takes an adverse action against another that inflicts intentional harm or discomfort (Olweus, Citation 1994).The method of delivery, however, can substantially vary from slapping, name-calling, exclusion from groups, or even harassment/embarrassment on social media.

qualitative school bullying and cyberbullying research. The articles included in this special issue of the International Journal of Bullying Prevention discuss dierent qualitative methods, reect on strengths and limitations — possibilities and challenges, and suggest implications for future qualita-tive and mixed-methods research. Included ...

Cyberbullying Defined. Cyberbullying involves the use of information and communication technologies, such as e-mail, cell phone and pager text messages, instant messaging, defamatory personal Web sites, and defamatory online personal polling Web sites, to support deliberate, repeated, and hostile behavior by an individual or group that is intended to harm others (Citation Belsey, 2004).

research. Cyberbullying can cause fear, low self-esteem, social isolation, bad academic performan ce. It can also cause difficulty in crea ting healthy relationships and most importantly, victims ...

victimized by cyberbullying. This research paper summarizes what the literature has already discovered about the experiences of cyberbullying for adolescents who have been victimized. The method for obtaining information is described and the findings are presented using descriptive statistics, independent t-test, and content analysis.

Like bullying, cyberbullying is a serious problem which can cause the victim to feel inadequate and overly self-conscious, along with the possibility of committing suicide due to being cyberbullied. Two such cases are included in this paper. There are numerous ways in which schools and parents can prevent cyberbullying and ways in which they can

Related Essays on Cyber Bullying. The Impact of Social Media and the Effects of Cyberbullying Essay. Communication as we know it is changing all around the world. When it comes to interaction with others many people would rather communicate nonverbally. ... Cyber bullying has become a prevalent issue in today's society, with the rise of social ...

Cyberbullying: next‐generation research. Cyberbullying, or the repetitive aggression carried out over electronic platforms with an intent to harm, is probably as old as the Internet itself. Research interest in this behavior, variably named, is also relatively old, with the first publication on "cyberstalking" appearing in the PubMed ...

School bullying research has a long history, stretching all the way back to a questionnaire study undertaken in the USA in the late 1800s (Burk, 1897).However, systematic school bullying research began in earnest in Scandinavia in the early 1970s with the work of Heinemann and Olweus ().Highlighting the extent to which research on bullying has grown exponentially since then, Smith et al. found ...

ChatGPT, OpenAI's text-generating AI chatbot, has taken the world by storm. What started as a tool to hyper-charge productivity through writing essays and code with short text prompts has evolved…

Although cyberbullying is a well-studied online risk, little is known about the effectiveness of various coping strategies for its victims. Therefore, this study on 2,092 Czech children aged 12-18 ...

Over the weekend, Mr. Jacobs accused the protesters of "bullying" in a statement on Instagram, but averred: His brand "does not work in, use or sell fur, nor will we in the future." He ...