Labour and Delivery Care Module: 4. Using the Partograph

Study session 4 using the partograph, introduction.

Among the five major causes of maternal mortality in developing countries like Ethiopia (hypertension, haemorrhage, infection, obstructed labour and unsafe abortion), the middle three (haemorrhage, infection, obstructed labour) are highly correlated with prolonged labour. To be specific, postpartum haemorrhage and postpartum sepsis (infection) are very common when the labour gets prolonged beyond 18–24 hours. Obstructed labour is the direct outcome of abnormally prolonged labour; you will learn about this in detail in Study Session 9 of this Module. To avoid such complications, a chart called a partograph will help you to identify the abnormal progress of a labour that is prolonged and which may be obstructed. It will also alert you to signs of fetal distress.

In this study session, you will learn about the principles of using the partograph, the interpretation of what it tells you about the labour you are supervising, and what actions you should take when the recordings you make on the partograph deviate from the normal range. When the labour is progressing well, the record on the partograph reassures you and the mother that she and her baby are in good health.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 4

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

4.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold . (SAQs 4.1 and 4.3)

4.2 Describe the significance and the applications of the partograph in labour progress monitoring. (SAQs 4.1 and 4.2)

4.3 Describe the components of a partograph and state the correct time intervals for recording your observations and measurements. (SAQs 4.1 and 4.3)

4.4 Describe the indicators in a partograph that show good progress of labour, and signs of fetal and maternal wellbeing. (SAQ 4.3)

4.5 Identify the indicators in a partograph for immediate referral to a hospital during the labour. (SAQ 4.3)

4.1 The value of using the partograph

The partograph is a graphical presentation of the progress of labour, and of fetal and maternal condition during labour. It is the best tool to help you detect whether labour is progressing normally or abnormally, and to warn you as soon as possible if there are signs of fetal distress or if the mother’s vital signs deviate from the normal range. Research studies have shown that maternal and fetal complications due to prolonged labour were less common when the progress of labour was monitored by the birth attendant using a partograph. For this reason, you should always use a partograph while attending a woman in labour, either at her home or in the Health Post.

In the study sessions in this Module, you have learned (or will learn) the major reasons why you need to monitor a labouring mother so carefully. Remember that a labour that is progressing well requires your help less than a labour that is progressing abnormally . Documenting your findings on the partograph during the labour enables you to know quickly if something is going wrong, and whether you should refer the mother to the nearest health centre or hospital for further evaluation and intervention.

4.2 Finding your way around of the partograph

The partograph is actually your record chart for the labouring mother (Figure 4.1). It has an identification section at the top where you write the name and age of the mother, her ‘gravida’ and ‘para’ status, her Health Post or hospital registration number, the date and time when you first attended her for the delivery, and the time the fetal membranes ruptured (her ‘waters broke’).

What is the difference between a woman who is a multigravida and one who is a multipara?

A multigravida is a woman who has been pregnant at least once before the current pregnancy. A multipara is a woman who has previously given birth to live babies at least twice before now.

On the back of the partograph (if you are not using another chart), you can also record some significant facts, such as the woman’s past obstetric history, past and present medical history, any findings from a physical examination and any interventions you initiate (including medications, delivery notes and referral).

4.2.1 The graph sections of the partograph

The graph sections of the partograph are where you record key features of the fetus or the mother in different areas of the chart. We will describe each feature, starting from the top of Figure 4.1 and travelling down the partograph.

- Immediately below the patient’s identification details, you record the Fetal Heart Rate initially and then every 30 minutes. The scale for fetal heart rate covers the range from 80 to 200 beats per minute.

- Below the fetal heart rate, there are two rows close together. The first of these is labelled Liquor – which is the medical term for the amniotic fluid ; if the fetal membranes have ruptured, you should record the colour of the fluid initially and every 4 hours.

- The row below ‘Liquor’ is labelled Moulding ; this is the extent to which the bones of the fetal skull are overlapping each other as the baby’s head is forced down the birth canal; you should assess the degree of moulding initially and every 4 hours

- Below ‘Moulding’ there is an area of the partograph labelled Cervix (cm) (Plot X) for recording cervical dilatation , i.e. the diameter of the mother’s cervix in centimetres. This area of the partograph is also where you record Descent of Head (Plot O) , which is how far down the birth canal the baby’s head has progressed. You record these measurements as either X or O, initially and every 4 hours. There are two rows at the bottom of this section of the partograph to write the number of hours since you began monitoring the labour and the time on the clock.

- The next section of the partograph is for recording Contractions per 10 mins (minutes) initially and every 30 minutes.

- Below that are two rows for recording administration of Oxytocin during labour and the amount given. (You are NOT supposed to do this – it is for a doctor to decide! However, you will be trained to give oxytocin after the baby has been born if there is a risk of postpartum haemorrhage.)

- The next area is labelled Drugs given and IV fluids given to the mother.

- Near the bottom of the partograph is where you record the mother’s vital signs ; the chart is labelled Pulse and BP (blood pressure) with a possible range from 60 to 180. Below that you record the mother’s Temp ° C (temperature).

- At the very bottom you record the characteristics of the mother’s Urine: protein, acetone, volume . You learned how to use urine dipsticks to test for the presence of a protein (albumin) during antenatal care.

You learned about giving IV (intravenous) fluid therapy to women who are haemorrhaging in Study Session 22 of the Antenatal Care Module.

What can you tell from the colour of the amniotic fluid?

If it has fresh bright red blood in it, this is a warning sign that the mother may be haemorrhaging internally; if it has dark green meconium (the baby’s first stool) in it, this is a sign of fetal distress.

4.2.2 The Alert and Action lines

In the section for cervical dilatation and fetal head descent, there are two diagonal lines labelled Alert and Action . The Alert line starts at 4 cm of cervical dilatation and it travels diagonally upwards to the point of expected full dilatation (10 cm) at the rate of 1 cm per hour. The Action line is parallel to the Alert line, and 4 hours to the right of the Alert line. These two lines are designed to warn you to take action quickly if the labour is not progressing normally.

4.3 Recording and interpreting the progress of labour

As you learned in Study Session 1 of this Module, a normally progressing labour is characterised by at least 1 cm per hour cervical dilatation, once the labour has entered the active first stage of labour.

Another important point is that (unless you detect any maternal or fetal problems), every 30 minutes you will be counting fetal heart beats for one full minute, and uterine contractions for 10 minutes.

You should do a digital vaginal examination initially to assess:

- The extent of cervical effacement (look back at Figure 1.1) and cervical dilatation

- The presenting part of the fetus

- The status of the fetal membranes (intact or ruptured) and amniotic fluid

- The relative size of the mother’s pelvis to check if the brim is wide enough for the baby to pass through.

Thereafter, in every 4 hours you should check the change in:

- Cervical dilatation

- Development of cervical oedema (an initially thin cervix may become thicker if the woman starts to push too early, or if the labour is too prolonged with minimal change in cervical dilatation)

- Position (of the fetus, if you are able to identify it)

- Fetal head descent

- Development of moulding and caput (Study Session 2 in this Module)

- Amniotic fluid colour (if the fetal membranes have already ruptured).

You should record each of your findings on the partograph at the stated time intervals as labour, progresses. The graphs you plot will show you whether everything is going well or one or more of the measurements is a cause for concern. When you record the findings on the partograph, make sure that:

- You use one partograph form per each labouring mother. (Occasionally, you may make a diagnosis of true labour and start recording on the partograph, but then you realise later that it was actually a false labour. You may decide to send the woman home or advise her to continue her normal daily activities. When true labour is finally established, use a new partograph and not the previously started one).

- You start recording on the partograph when the labour is in active first stage (cervical dilation of 4 cm and above).

- Your recordings should be clearly visible so that anybody who knows about the partograph can understand and interpret the marks you have made.

If you have to refer the mother to a higher level health facility, you should send the partograph with your referral note and record your interpretation of the partograph in the note.

Without looking back over the previous sections, quickly write down the partograph measurements that you must make in order to monitor the progress of labour.

Compare your list with the partograph in Figure 4.1. If you are at all uncertain about any of the measurements, then re-read Sections 4.2 and 4.3.

4.4 Cervical dilatation

As you learned in Study Session 1 of this Module, the first stage of labour is divided into the latent and the active phases. The latent phase at the onset of labour lasts until cervical dilatation is 4 cm and is accompanied by effacement of the cervix (as shown in Figure 1.1 previously). The latent phase may last up to 8 hours, although it is usually completed more quickly than this. Although regular assessments of maternal and fetal wellbeing and a record of all findings should be made, these are not plotted on the partograph until labour enters the active phase.

Vaginal examinations are carried out approximately every 4 hours from this point until the baby is born. The active phase of the first stage of labour starts when the cervix is 4 cm dilated and it is completed at full dilatation, i.e. 10 cm. Progress in cervical dilatation during the active phase is at least 1 cm per hour (often quicker in multigravida mothers).

In the cervical dilatation section of the partograph, down the left side, are the numbers 0–10. Each number/square represents 1 cm dilatation. Along the bottom of this section are 24 squares, each representing 1 hour. The dilatation of the cervix is estimated by vaginal examination and recorded on the partograph with an X mark every 4 hours. Cervical dilatation in multipara women may need to be checked more frequently than every 4 hours in advanced labour, because their progress is likely to be faster than that of women who are giving birth for the first time.

In the example in Figure 4.2, what change in cervical dilatation has been recorded over what time period?

The cervical dilatation was about 5 cm at 1 hour after the monitoring of this labour began; after another four hours, the mother’s cervix was fully dilated at 10 cm.

If progress of labour is satisfactory, the recording of cervical dilatation will remain on, or to the left, of the alert line.

If the membranes have ruptured and the woman has no contractions, do not perform a digital vaginal examination, as it does not help to establish the diagnosis and there is a risk of introducing infection. (PROM, premature rupture of membranes, was the subject of Study Session 17 of the Antenatal Care Module.)

4.5 Descent of the fetal head

For labour to progress well, dilatation of the cervix should be accompanied by descent of the fetal head, which is plotted on the same section of the partograph, but using O as the symbol. But before you can do that, you must learn to estimate the progress of fetal descent by measuring the station of the fetal head, as shown in Figure 4.3. The station can only be determined by examination of the woman’s vagina with your gloved fingers, and by reference to the position of the presenting part of the fetal skull relative to the ischial spines in the mother’s pelvic brim.

As you can see from Figure 4.3, when the fetal head is at the same level as the ischial spines, this is called station 0. If the head is higher up the birth canal than the ischial spines, the station is given a negative number. At station –4 or –3 the fetal head is still ‘floating’ and not yet engaged; at station –2 or –1 it is descending closer to the ischial spines.

If the fetal head is lower down the birth canal than the ischial spines, the station is given a positive number. At station +1 and even more at station +2, you will be able to see the presenting part of baby’s head bulging forward during labour contractions. At station +3 the baby’s head is crowning , i.e. visible at the vaginal opening even between contractions. The cervix should be fully dilated at this point.

Now that you have learned about the different stations of fetal descent, there is a complication about recording these positions on the partograph. In the section of the partograph where cervical dilatation and descent of head are recorded, the scale to the left has the values from 0 to 10. By tradition, the values 0 to 5 are used to record the level of fetal descent. Table 4.1 shows you how to convert the station of the fetal head (as shown in Figure 4.3) to the corresponding mark you place on the partograph by writing O. (Remember, you mark fetal descent with Os and cervical dilatation with Xs, so the two are not confused.)

When the baby’s head starts crowning (station +3), you may not have time to record the O mark on the partograph!

What does crowning mean and what does it tell you?

Crowning means that the presenting part of the baby’s head remains visible between contractions; this indicates that the cervix is fully dilated.

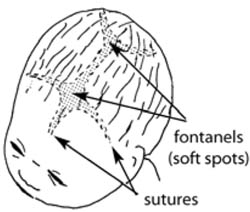

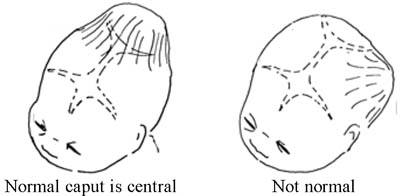

4.6 Assessing moulding and caput formation

The five separate bones of the fetal skull are joined together by sutures, which are quite flexible during the birth, and there are also two larger soft areas called fontanels (Figure 4.4). Movement in the sutures and fontanels allows the skull bones to overlap each other to some extent as the head is forced down the birth canal by the contractions of the uterus. The extent of overlapping of fetal skull bones is called moulding , and it can produce a pointed or flattened shape to the baby’s head when it is born (Figure 4.5).

Some baby’s skulls have a swelling called a caput in the area that was pressed against the cervix during labour and delivery (Figure 4.6); this is common even in a labour that is progressing normally. Whenever you detect moulding or caput formation in the fetal skull as the baby is moving down the birth canal, you have to be more careful in evaluating the mother for possible disproportion between her pelvic opening and the size of the baby’s head. Make sure that the pelvic opening is large enough for the baby to pass through. A small pelvis is common in women who were malnourished as children, and is a frequent cause of prolonged and obstructed labour.

4.6.1 Recording moulding on the partograph

To identify moulding, first palpate the suture lines on the fetal head (look back at Figure 1.4 in the first study session of this Module) and appreciate whether the following conditions apply. The skull bones that are most likely to overlap are the parietal bones, which are joined by the sagittal suture, and have the anterior and posterior fontanels to the front and back.

- Sutures apposed: This is when adjacent skull bones are touching each other, but are not overlapping. This is called degree 1 moulding (+1).

- Sutures overlapped but reducible: This is when you feel that one skull bone is overlapping another, but when you gently push the overlapped bone it goes back easily. This is called degree 2 moulding (+2).

- Sutures overlapped and not reducible : This is when you feel that one skull bone is overlapping another, but when you try to push the overlapped bone, it does not go back. This is called degree 3 moulding (+3). If you find +3 moulding with poor progress of labour, this may indicate that the labour is at increased risk of becoming obstructed.

When you document the degree of moulding on the partograph, use a scale from 0 (no moulding) to +3, and write them in the row of boxes provided:

0 Bones are separated and the sutures can be felt easily.

+1 Bones are just touching each other.

+2 Bones are overlapping but can be separated easily with pressure by your finger.

+3 Bones are overlapping but cannot be separated easily with pressure by your finger.

In the partograph, there is no specific space to document caput formation. However, caput detection should be part of your assessment during each vaginal examination. Like moulding, you grade the degree of caput as 0, +1, +2 or +3. Because of its subjective nature, grading the caput as +1 or +3 simply indicates a ‘small’ and a ‘large’ caput respectively. You can document the degree of caput either on the back of the partograph, or on the mother’s health record (if you have it).

Imagine that you are assessing the degree of moulding of a fetal skull. What finding would make you refer the woman in labour most urgently, and why?

If you found +3 moulding and the labour was progressing poorly, it may mean there is uterine obstruction.

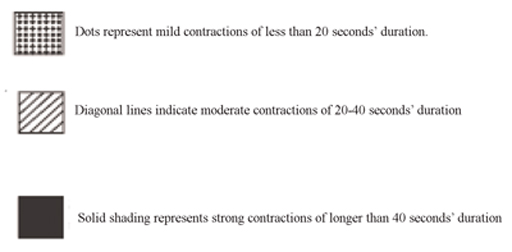

4.7 Uterine contractions

You already know that good uterine contractions are necessary for good progress of labour (Study Session 2). Normally, contractions become more frequent and last longer as labour progresses. Contractions are recorded every 30 minutes on the partograph in their own section, which is below the hour/time rows. At the left hand side is written ‘Contractions per 10 mins’ and the scale is numbered from 1–5. Each square represents one contraction, so that if two contractions are felt in 10 minutes, you should shade two squares.

On each shaded square, you will also indicate the duration of each contraction by using the symbols shown in Figure 4.7.

4.8 Assessment and recording of fetal wellbeing

How do you know that the fetus is in good health during labour and delivery? The methods open to you are limited, but you can assess fetal condition:

- By counting the fetal heart beat every 30 minutes;

- If the fetal membranes have ruptured, by checking the colour of the amniotic fluid.

4.8.1 Fetal heart rate as an indicator of fetal distress

The normal fetal heart rate at term (37 weeks and more) is in the range of 120–160 beats/minute. If the fetal heart rate counted at any time in labour is either below 120 beats/minute or above 160 beats/minute, it is a warning for you to count it more frequently until it has stabilised within the normal range. It is common for the fetal heart rate to be a bit out of the normal range for a short while and then return to normal. However, f etal distress during labour and delivery can be expressed as:

- Fetal heart beat persistently (for 10 minutes or more) remains below 120 beats/minute (doctors call this persistent fetal bradycardia ).

- Fetal heart beat persistently (for 10 minutes or more) remains above 160 beats/minute (doctors call this persistent fetal tachycardia ).

4.8.2 Causes of fetal distress

There are many factors that can affect fetal wellbeing during labour and delivery. You learned in the Antenatal Care Module (Study Session 5) that the fetus is dependent on good functioning of the placenta and good supply of nutrients and oxygen from the maternal blood circulation. Whenever there is inadequacy in maternal supply or placental function, the fetus will be at risk of asphyxia, which is going to be manifested by the fetal heart beat deviating from the normal range. Other factors that will affect fetal wellbeing, which may be indicated by abnormal fetal heart rate, are shown in Box 4.1.

You learned about hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, maternal anaemia and placental abruption in Study Sessions 18, 19 and 21 of the Antenatal Care Module, Part 2.

Box 4.1 Reasons for fetal heart rate deviating from the normal range

Placental blood flow to the fetus is compromised, which commonly occurs when there is:

- Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy

- Maternal anaemia

- Decreased maternal blood volume (hypovolemia) due to blood loss, or body fluid loss through vomiting and diarrhoea

- Maternal hypoxia (shortage of oxygen) due to maternal heart or lung disease, or living in a very high altitude

- A placenta which is ‘aged’

- Amniotic fluid becomes scanty, which prevents the fetus from moving easily; the umbilical cord may become compressed against the uterine wall by the baby’s body

- Umbilical cord is compressed because of prolapsed (coming down the birth canal ahead of the fetus), or is entangled around the baby’s neck

- Placenta prematurely separates from the uterine wall ( placental abruption ).

With that background in mind, counting the fetal heart beat every 30 minutes and recording it on the partograph, may help you to detect the first sign of any deviation for the normal range. Once you detect any fetal heart rate abnormality, you shouldn’t wait for another 30 minutes; count it as frequently as possible and arrange referral quickly if persists for more than 10 minutes.

4.8.3 Recording fetal heart rate on the partograph

The fetal heart rate is recorded at the top of the partograph every half hour in the first stage of labour (if every count is within the normal range), and every 5 minutes in the second stage. Count the fetal heart rate:

- As frequently as possible for about 10 minutes and decide what to do thereafter.

- Count every five minutes if the amniotic fluid (called liquor on the partograph) contains thick green or black meconium.

- Whenever the fetal membranes rupture, because occasionally there may be cord prolapse and compression, or placental abruption as the amniotic fluid gushes out.

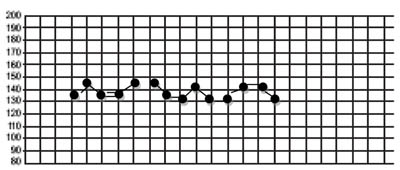

Each square for the fetal heart on the partograph represents 30 minutes. When the fetal heart rate is in the normal range and the amniotic fluid is clear or only lightly blood-stained, you can record the results on the partograph, as in the example in Figure 4.8. When you count the fetal heart rate at less than 30 minute intervals, use the back of the partograph to record each measurement. Prepare a column for the time and fetal heart rate.

4.8.4 Amniotic fluid as an indicator of fetal distress

Another indicator of fetal distress which has already been mentioned is meconium-stained amniotic fluid (greenish or blackish liquor). Lightly stained amniotic fluid may not necessarily indicate fetal distress, unless it is accompanied by persistent fetal heart rate deviations outside the normal range. The following observations are made at each vaginal examination and recorded on the partograph, immediately below the fetal heart rate recordings.

If the fetal membranes are intact, write the letter ‘I’ (for ‘intact’).

If the membranes are ruptured and:

- liquor is absent, write ‘A’ (for ‘absent’)

- liquor is clear, write ‘C’ (for ‘clear’)

- liquor is blood-stained, record ‘B’

- liquor is meconium-stained, record ‘M 1 ’ for lightly stained, ‘M 2 ’ for a little bit thick and ‘M 3 ’ for very thick liquor which is like soup (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2 Extent of meconium staining

- M 1 liquor in latent first stage of labour, even with normal fetal heart rate.

- M 2 liquor in early active first stage of labour, even with normal fetal heart rate.

- M 3 liquor in any stage of labour, unless progressing fast.

4.9 Assessment of maternal wellbeing

During labour and delivery, after your thorough initial evaluation, maternal wellbeing is followed by measuring the mother’s vital signs: blood pressure, pulse, temperature, and urine output. Blood pressure is measured every four hours. Pulse is recorded every 30 minutes. Temperature is recorded every 2 hours. Urine output is recorded every time urine is passed. If you identify persistent deviations from the normal range of any of these measurements, refer the mother to a higher health facility.

Summary of Study Session 4

In Study Session 4, you have learned that:

- The partograph is a valuable tool to help you detect abnormal progress of labour, fetal distress and signs that the mother is in difficulty.

- The partograph is designed for recording maternal identification, fetal heart rate, colour of the amniotic fluid, moulding of the fetal skull, cervical dilatation, fetal descent, uterine contractions, whether oxytocin was administered or intravenous fluids were given, maternal vital signs and urine output.

- Start recording on the partograph when the labour is in active first stage (4 cm or above).

- Cervical dilatation, descent of the fetal head and uterine contractions are used in assessing the progress of labour. About 1 cm/hour cervical dilatation and 1 cm descent in four hours indicate good progress in the active first stage.

- Fetal heart rate and uterine contractions are recorded every 30 minutes if they are in the normal range. Assess cervical dilatation, fetal descent, the colour of amniotic fluid (if fetal membranes have ruptured), and the degree of moulding or caput every four hours.

- Do a digital vaginal examination immediately if the membranes rupture and a gush of amniotic fluid comes out while the woman is in any stage of labour.

- Refer the woman to health centre or hospital if the cervical dilatation mark crosses the Alert line on the partograph.

- When you identify +3 moulding of the fetal skull with poor progress of labour, this indicates labour obstruction, so refer the mother urgently.

- Fetal heart rate below 120/min or above 160/min for more than 10 minutes is an urgent indication to refer the mother, unless the labour is progressing too fast.

- Even with a normal fetal heart rate, refer if you see amniotic fluid (liquor) lightly stained with meconium in latent first stage of labour, or moderately stained in early active first stage of labour, or thick amniotic fluid in all stages of labour, unless the labour is progressing too fast.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 4

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

Read Case Study 4.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 4.1 Bekelech’s story

Bekelech is a gravida 5, para 4 mother, whose current pregnancy has reached the gestational age of 40 weeks and 4 days. When you arrive at her house, she is already in labour. During your first assessment, she had four contractions in 10 minutes, each lasting 35–40 seconds. On vaginal examination, the fetal head was at –3 station and Bekelech’s cervix was dilated to 5 cm. The fetal heart rate at the first count was 144 beats/min.

SAQ 4.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3)

- a. What does it mean to say that Bekelech is a ‘gravida 5, para 4 mother’?

- b. How would you describe the gestational age of Bekelech’s baby?

- c. Which stage of labour has she reached and is the baby’s head engaged yet?

- d. Is the fetal heart rate normal or abnormal?

- e. What would you do to monitor the progress of Bekelech’s labour?

- f. How often would you do a vaginal examination in Bekelech’s case and why?

- a. As a gravida 5, para 4 mother you know that Bekelech has had 5 pregnancies of which 1 has not resulted in a live birth .

- b. At 40 weeks and 4 days the gestation is term (or full term).

- c. Bekelch’s cervix has dilated to 5 cm and she is having four contractions in 10 minutes of 35-40 seconds each, so she has entered the active phase of first stage labour. At -3 station, the fetal head is not yet engaged.

- d. The fetal heart rate is within the normal range of 120-160 beats/minute.

- e. As Bekelech’s labour is in the active phase and her cervix has dilated to more than 4 cm, you immediately begin regular monitoring of the progress of her labour, her vital signs, and indicators of fetal wellbeing distress. You record of all these key measurements on the partograph (refer again to Figure 4.1 and Section 4.2.1).

- f. You decide to do vaginal examinations more frequently than the advisory four hours, because Bekelech’s labour may progress quite quickly as she is a multigravida/multipara mother. And you keep alert to the possibility of something going wrong, because Bekelech has already lost one baby before it was born.

SAQ 4.2 (tests Learning Outcome 4.2)

Give two reasons for using a partograph.

Two key reasons for using a partograph are because:

- a. If used correctly it is a very useful tool for detecting whether or not labour is progressing normally, and therefore whether a referral is needed. When the labour is progressing well, the record on the partograph reassures you and the mother that she and her baby are in good health.

- b. Research has shown that fetal complications of prolonged labour are less common when the birth attendant uses a partograph to monitor the progress of labour.

Advancement in Partograph: WHO’s Labor Care Guide

Yash ghulaxe.

1 Medical Student, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, IND

Surekha Tayade

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, IND

Shreyash Huse

Jay chavada.

Worldwide, the partograph, also known as a partogram, is used as a labor monitoring tool to detect difficulties early, allowing for referral, intervention, or closer observations to follow. Despite widespread support from health experts, there are worries that the partograph has not yet fully realized its potential for enhancing therapeutic results. As a result, the instrument has undergone several changes, and numerous studies have been conducted to examine the obstacles and enablers to its use. Nevertheless, the partograph was widely embraced and has been a component of evaluating labor progress. Earlier it was also used as a standard method for monitoring labor progress. Even though it is widely used, there have been reports of usage and accurate execution rates. The WHO Labor Care Guide (LCG) was created so that medical professionals could keep an eye on the health of pregnant women and their unborn children during labor by conducting routine evaluations to spot any abnormalities. The tool intends to enhance women-centered care and encourage collaborative decision-making between women and healthcare professionals. The LCG is designed to be a tool for ensuring high-quality research centered on health, reducing pointless measures, and offering comfort measures.

Introduction and background

Worldwide, more than 14 crore females have childbirth per year, and the percentage of deliveries by trained medical workers is rising gradually [ 1 ]. Complications during labor and delivery cause maternal deaths (>1/3rd), stillbirths (1/2), and newborn deaths (1/4th) [ 2 , 3 ]. Most of these fatalities occur in low-resource environments and might be largely avoided with prompt interventions [ 4 ].

Over the past 20 years, widespread support for skilled birth attendance has been made in an effort to reduce unnecessary maternal and perinatal death and morbidity [ 5 ]. Worldwide, this has resulted in significant increases in facility-based deliveries and the coverage of births attended by trained medical staff (up from 62% in 2000 to 80% in 2017) [ 6 ]. Although the range has increased, this has not necessarily resulted in the anticipated decline in mortality and morbidity during delivery, indicating that subpar treatment grade is still a problem in hospitals [ 7 - 11 ]. Regularly overused interventions include early amniotomy, oxytocin for augmentation, and continuous fetal monitoring [ 12 ]. Rising Caesarean section (CS) rates and poorer birth experiences for women have been attributed to this over-medicalized and frequently disrespectful treatment [ 13 - 15 ]. Therefore, it is critical to regularly monitor labor and delivery to spot dangers or difficulties and stop bad birth results. The most popular labor monitoring device is the partograph, and trained healthcare professionals have been using it to provide care during labor for more than 40 years.

However, the partograph needed to be revised to facilitate care following new research and international priorities in light of the WHO recommendations (2018) on intrapartum supervision for pleasant birth [ 16 ]. To promote the health and wellbeing of women and their unborn children, the guidelines build up recent development of definitions of the length of the first and second stages of labor. In addition, they offer advice on time and usage of labor interference [ 17 , 18 ]. The WHO guidelines included in this list are: care during labor and delivery includes considerate maternal care, effective communication, labor amity, and continuity of care. The first stage includes clinical pelvimetry upon admission, the definition of latent and active first stages, the length and advancement of the first stage, the labor ward admission policy, pubic shaving, access enema, and vaginal examination. The second stage of labor includes: what it is, how long it lasts, how to give birth (with or without epidural anesthesia), how to push, how to avoid perineal injuries, and how to do an episiotomy. Prophylactic uterotonics, delayed cord clamping, controlled cord traction, and uterine massage are done during the third stage of labor. Regular nasal or oral suction during resuscitation, skin-to-skin contact, nursing, vitamin K prophylaxis for hemorrhagic sickness, bathing, and other early postnatal care of the infant are all included in the newborn's care. Following an uneventful vaginal birth, the lady will get postpartum care that includes monitoring her uterine tonus, taking antibiotics, standard postpartum maternal assessments, and discharge.

As a result, in 2018, WHO began work on a "next-generation" partograph, the WHO Labor Care Guide (LCG), with the following objectives: frequently refreshing professionals to provide reassuring treatment during delivery and to refresh for regular inspection that should be done at work to spot any developing complications, in the mother and the fetus; offer benchmarks for aberrant labor observations that should prompt particular responses; reduce needless interventional use and over- and under-diagnosis of problematic labor episodes; assist with audits and raising the standard of labor care. The old WHO partogram failed to demonstrate any meaningful clinical effect; hence this is an urgent requirement [ 19 ]. It is crucial that the LCG can accommodate maternity care and professionals' needs and that it contains the proper criteria for labor monitoring. The LCG was designed to care for mothers and their newborns throughout labor and delivery. Although there was no risk status, it comprises evaluations and examinations, which are crucial for treating all child-bearing females.

However, the LCG was primarily intended to be utilized to care for pregnant people who appeared to be in good health and their unborn children (i.e., low-risk pregnancies). Women at a greater risk of having difficulties during delivery might need more specific monitoring and care [ 20 ]. Even though LCG was primarily developed to be used for the surveillance of child-bearing females who appeared to be in good health, high-risk females who were having labor problems could also benefit from it as an observing tool [ 21 ]. Regardless of the woman's parity or the condition of her membranes, documentation on the LCG of the mother's and the baby's health and the labor's progression should begin when she enters the first stage's active phase of labor (five centimeters or greater cervical dilatation). Women and their babies are expected to be observed and provided care and support during the latent stage of labor, even though LCG should not be started at that time. Pregnancy, delivery, postpartum, and infant care: a guide for essential practice provides comprehensive instructions on how to treat patients during the latent period of labor [ 22 ]. The LCG was developed after extensive research, information synthesis, consultation, field testing, and improvement [ 23 , 24 ].

The LCG differs from earlier partograph designs in addressing the length of labor, identifying when clinical interventions are necessary, and focusing on keeping the mother safe. It is expected that a change from common partograph makeup may make medical professionals uneasy or even hostile. However, change should not be implemented merely for the sake of change because it is difficult. Therefore, the seven portions of LCG were modified from the original partograph layout. As shown in Figure Figure1, 1 , the sections are: identifying information and labor characteristics at admission, supportive care, care of the baby, care of the woman, labor progress, medication, and shared decision-making.

Source: [ 25 ]

The woman's name, parity, method of labor onset, date of active labor diagnosis, date and time of membrane rupture, and risk factors should all be recorded in Section 1 of the labor admission record. This part should be finished with the knowledge acquired after a confirmed diagnosis of active labor. There is a list of labor observations in Sections 2-7. As soon as the lady is admitted to the labor unit, the healthcare provider should start recording observations for all parts. The remaining LCG is then finished after additional labor-related evaluations. Each compliance has two axes, a perpendicular line data axis for noticing any departure from the typical remarks and a horizontal time axis for tracking the length of the inquiry. The woman's name and other crucial details necessary to comprehend her baseline features and risk status at the time of labor admission are written in Section 1 as well. The woman's medical file should also have information on other crucial demographic and labor features, like her age, period of gestational, serological outcomes, hematocrit, blood group, Rh factor, status, referral reason, and symphysis-fundal length. Supportive care is discussed in Section 2. The WHO's recommendations for intrapartum care strongly emphasize respectful maternity care as a fundamental human right of expectant mothers [ 26 ]. At each stage of labor care, the WHO advises clear interaction between health professionals and women in labor, including using easy, appropriate terminology. All women should receive a thorough explanation of the techniques being used and why. The woman and her companion should be informed of the results of the physical examinations. Baby care is included under Section 3. The fetal heart rate (FHR), amniotic fluid, the position of the fetus, the shape of the fetal head, and the development of the caput succedaneum are all regularly observed to determine the baby's health. Section 4 adds maternal care. This section attempts to make it simpler to make decisions on sporadic, ongoing monitoring of women's wellness. On the LCG, the pulse, blood pressure, temperature, and urine are regularly observed to keep track of the woman's health and well-being. Work progress is shown in Section 5. This part promotes the routine practice of periodic observation of labor development markers. The labor process is tracked on LCG by regularly observing the frequency and length of contractions, cervical dilatation, and fetal descent. By indicating the patient is getting oxytocin, its dosage and whether other drugs or IV fluids are given. Section 6 intends to allow constant observation of all forms of drugs used during labor. Section 7 makes it easier for the lady and her companion to communicate continuously and for all assessments and agreed-upon plans to be consistently recorded.

The partograph and the LCG are tools used to enhance women-centered care, but they also have some points in common and distinctions. The fundamental and revolutionary aspect of the original "Philpott chart" was its graphical display of labor development in relation to women's cervical dilation and fall of presenting part of the fetus against time [ 27 , 28 ]. The LCG and modified WHO partograph share some of these characteristics. Despite cosmetic changes, this idea still holds a prominent place in the LCG. Additionally, regular formal monitoring of significant clinical parameters reflecting the frequency and duration of uterine activity and the health of the mother and the unborn child continues. The LCG mainly focuses on clinical parameters rather than parameters obtained from USG [ 25 ]. The LCG has the following improvements among the two uncommon features: the initial moment of the first stage's active phase of labor is dilatation of the cervix of five centimeters (in spite of four centimeters or less); it adds up a division for observing second labor stage; it consists of a division to evaluate and advance the use of understanding interruptions to enhance child health, and every cm of cervical dilatation during the first stage of labor resulted in a shift in the hourly "alarm" line and its corresponding "action" line with corroboration-based time constraints. Table Table1 1 below provides information on the frequent and rare characteristics of LCG and modified partograph [ 29 ]. Specialists distinguished a few difficulties in utilizing LCG that are normal to the utilization of any partograph. A 2014 deliberate survey on partograph use in low-pay and center-pay nations found that while the partograph was largely seen as a valuable device for observing work, its utilization was frequently seen as tedious [ 30 ].

LCG: Labor Care Guide.

Common features are animated timelines showing the progression of labor as measured by cervical dilatation and the head descent and formal and consistent documentation of crucial clinical indicators indicating the mother's and child's health. However, there were some restrictions on how typical labor progressed. Since labor's active first stage is supposed to be indicated by a line drawn at one centimeter per hour from the initial assessment of the cervix, the original partograph uses this technique (three or four cm) to identify prolonged labor (when the action line is crossed), and a parallel line two hours (commonly four hours) later, as the alert or projected normal progress line [ 31 ]. This style was developed using Friedman and Kroll's landmark research, suggesting the average cervical dilatation rate in primigravida was diphasic, slower before three-centimeter dilatation, and roughly one centimeter per hour after three centimeters [ 31 ]. The primary problem with converting this statistical overview of several labors into a template for specific women is that it ignores the variation in women's progression rates. Additionally, because the action line criterion for protracted labor is set in advance for full delivery, it does not consider the non-linear progression of each woman's labor. For instance, it might take longer than four hours to get to the action line if labor had advanced quickly and was suddenly stopped. However, suppose labor has been prolonged due to insufficient uterine movement and has traversed the action line. In that case, it might continue to advance usually but cause anxiety as it is on the action line's wrong side. This anxiety is then useless for directing the course of the rest of the labor. Because guiding factors for labor advancement are dynamic rather than static in the new table for recording labor advancement in LCG, there are significant differences. Instead of setting constant rate boundaries for overall labor's active first stage, contemplation for interruption is governed by a proof-based limit of time for every inch of dilatation of the cervix, which is acquired from 95th percentiles of labor span at various cm stage in a female with ordinary perinatal results [ 32 ]. Even if it takes an unusually short amount of time to reach a dilation of 9 cm, the projected upper limit of 10 cm stays the same. The appropriate cervical assessment (designated by an x) would be highlighted. Actions for responding will be recorded in the plan division, just as in different metrics in the alert division, such as moving from nine to ten centimeters and exceeding two hours. LCG and the partograph vary most noticeably in not presence of the limit lines (diagonal labor progress). An obvious need for recorded feedback when certain parameters have crossed, even though lines are discarded, and the parameters are now presented in a modern, proof-based fashion. The definition of the active phase depends upon the point of inflection on the Friedman curve, original partograph during the first stage of labor identified the beginning of the active phase as 3 cm cervical dilation. The WHO shifted this threshold to 4 cm due to changes to the partograph [ 33 ]. It is compelling that Friedman lately pointed out a misinterpretation of his project and admitted that point of inflection does, in fact, vary from woman to woman. The three or four-centimeter threshold was frequently elaborated as explaining Friedman's actual project. The median cervical dilation rate in normal women without unfavorable perinatal results was observed to pass one centimeter/hour at five centimeters, which marks the fast start of the cervical dilatation process and is the milestone used by the LCG [ 34 ]. This reduces the premature classification of labor's active phase, a significant elicited reason for ostensibly slow labor advancement and needless interruptions [ 35 ]. Because it can only be accurately identified in hindsight, the latent phase of the initial labor stage is challenging to identify, according to the LCG. Its timing is frequently ambiguous, and the length of time it lasts varies greatly across women. Innate in the real plan of the partograph, which set aside the latent phase for eight hours, is a potential source of unnecessary intervention known as premature charting of the latent phase. By starting to chronicle the progress of the labor process after the active phase has been identified, this is neglected in the updated partograph style and LCG.

At a later stage of labor, the fact that the second stage of work is excluded from the original partograph design and its revisions is a significant drawback. During the labor's second stage, there is no obligation to explicitly continue keeping an eye on the mother's and the baby's health or the labor's progress. The second stage of work is particularly crucial because of increased uterine activity and the mother's efforts to expel the baby; if caution is not exercised during this time, disastrous results may result. The LCG addresses this gap by emphasizing the importance of paying near awareness to the development and the welfare of both mother and child during the second stage. The LCG is intended for the significance of the exploratory aspect of labor by demanding graphic noting of proof-based applications that are important for better clinical results for mothers and their children and women's good birth experiences. The LCG contains assessments of the labor partner, mouth hydration, mother motility and attitude, and pain management to promote intrapartum care and encourage using these evidence-based, but sometimes underutilized interventions. The LCG is beyond just a scientific instrument for keeping track of a woman's health and that of her unborn child throughout labor. The tool also offers testimonial values for the mother and fetal scrutiny and stimulates detailed documentation of the mother's vital signs, fetal welfare, and labor advancement. The plain necessity to circle any statement that conflicts with care, comfort, or labor advancement and to document clinical or reassuring care feedback in conferences with women serves to reinforce the tool's care purpose by encouraging early recognition and improvement of the support that mother and offspring experienced. The caregiver enters the overall evaluation, any new information not before recorded but crucial for labor observation is entered in the "Assessment" part, and the care scheme developed in consultation with the mother is entered in the "Plan" section. This makes LCG more than just labor documentation that could have been finished in the past; it makes it a contemporary monitoring and response tool.

Conclusions

In the past few years, a lot has shifted in the way we provide proof-based, compassionate care during delivery. Future studies will be needed to count women's experiences with care to completely comprehend the applicability and implications of labor care and results. Nevertheless, medical practitioners will be convinced that the fundamental principles that informed the construction of the modified partograph in utilizing the new instrument would not compromise but rather advance the objectives of the earlier partograph. LCG has evolved to reflect these changes and will motivate best practices, which add advancement of excellent, considerate care for all women, new mothers, and their families.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Advertisement

The Partograph in Childbirth: An Absolute Essentiality or a Mere Exercise?

- Invited Review Article

- Published: 16 October 2017

- Volume 68 , pages 3–14, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Asha R. Dalal 1 &

- Ameya C. Purandare 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

1156 Accesses

16 Citations

Explore all metrics

WHO has recommended use of the partograph, a low-tech paper form that has been hailed as an effective tool for the early detection of maternal and fetal complications during childbirth. Yet despite decades of training and investment, implementation rates and capacity to correctly use the partograph remain low in resource-limited settings. Nevertheless, competent use of the partograph, especially using newer technologies, can save maternal and fetal lives by ensuring that labor is closely monitored and that life-threatening complications such as obstructed labor are identified and treated. To address the challenges for using partograph among health workers, health-care systems must establish an environment that supports its correct use. Health-care staff should be updated by providing training and asking them about the difficulties faced at their health center. Then only the real potential of this wonderful tool will be maximally utilized.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Use of an electronic partograph: feasibility and acceptability study in zanzibar, tanzania.

The Partogram and Sonopartogram

Comparing different partograph designs for use in standard labor care: a pilot randomized trial.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for augmentation of labor. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Google Scholar

Lavender T, Hart A, Smyth RMD. Effect of partogram use on outcomes for women in spontaneous labor at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub4 .

Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:567.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

Magon N. Partograph revisited. Int J Clin Cases Investig. 2011;3(1):1:6.

The Partograph. A Managerial tool for the prevention of prolonged labor. The World Health Organization, Geneva; 1998 (section 2, A User’s manual) .

Tayade S, Jadhao P. The impact of use of modified who partograph on maternal and perinatal outcome. Int J Biomed Adv Res. 2002;3(4):256–62.

Lavender T, Omoni G, Lee K, et al. Student nurses experiences of using the partograph in labor wards in Kenya: a qualitative study. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;5(3):117–22. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2011.5.3.117 .

Article Google Scholar

Yisma E, Dessalegn B, Astatkie A, et al. Completion of the modified World Health Organization (WHO) partograph during labor in public health institutions of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health J. 2013;10(23):1–7.

Rakotonirina JEC, Randrianantenainjatovo CH, Elyan Edwige BB, et al. Assessment of the use of partographs in the region of Analamanga. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2(3):257–62. doi: 10.5455/2320-1770.ijrcog20130901 .

Fatusi AO, Makinde ON, Adetemi AB. Evaluation of health workers’ training in use of the partogram. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.07.020 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fahdhy M, Chongsuvivatwong V. Evaluation of World Health Organization partograph implementation by midwives for maternity home birth in Medan, Indonesia. Midwifery. 2005;21(4):301–10. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2004.12.010 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Nkyekyer K. Peripartum referrals to Korle Bu teaching hospital, Ghana—a descriptive study. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5(11):811–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00640.x .

Orji EO, Fatusi AA, Maknde NO, et al. Impact of training on the use of partograph on maternal and perinatal outcome in peripheral health centers. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2007;8(2):148–52.

Javad I, Bhutta S, Shoaib T. Role of the partogram in preventing prolonged labor. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57(8):408–11.

Badjie B, Kao C-H, Gua M-l, Lin K-C. Partograph use among midwives in the Gambia. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;7(2):65–9. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2013.7.2.65 .

Qureshi ZP, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Mutiso SM. Rapid assessment of partograph utilization in selected maternity units in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2010;87(6):235–41.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Orhue AAE, Aziken ME, Osemwenkha AP. Partograph as a tool for team work management of spontaneous labor. Niger J Clin Pract. 2012;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.94087 .

Ogwang S, Karyabakabo Z, Rutebemberwa E. Assessment of partogram use during labor in Rujumbura Health sub district, Rukungiri District, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(1):s27–34.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Okokon IB, Oku AO, Agan TU, et al. An evaluation of the knowledge and utilization of the partogragh in primary, secondary, and tertiary care settings in Calabar, South-South Nigeria. Int J Fam Med. 2014;. doi: 10.1155/2014/105853 .

Opiah MM, Ofi AB, Essien EJ, et al. Knowledge and utilization of the partograph among midwives in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16(1):125–32.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mercer WM, Sevar K, Sadutshan TD. Using clinical audit to improve the quality of obstetric care at the Tibetan Dalek Hospital in North India: a longitudinal study. Reprod Health. 2006;3(4):1–4.

Groeschel N, Glover P. The partograph. Used daily but rarely questioned. Aust J Midwifery. 2001;14(3):22–7. doi: 10.1016/S1445-4386(01)80021-5 .

Prem A, Smitha MV. Effectiveness of individual teaching on knowledge regarding partograph among staff nurses working in maternity wards of selected hospitals at Mangalore. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2013;4(7):1163–6.

Robertson B, Schumacher L, Gosman G, et al. Crisis-based team training for multidisciplinary obstetric providers. Empir Investig. 2009;4(2):77–83.

Guise GM, Segal S. Teamwork in obstetric critical care. Best practice & research. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(5):937–51.

Siassakos D, Crofts JF, Winter C, et al. The active components of effective training in obstetric emergencies. BJOG. 2009;116(8):1028–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02178.x .

Debdas AK. Paperless partogram. 41st annual scientific session 2008; Sri Lanka College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists: SLJOG: vol 30 2008; 1(1):124.

Jhpiego. The E-Partogram. Retrieved on May 10, 2012 from http://savinglivesatbirth.net/summaries/35 .

India Maternal Health Initiative by Jiva Diya Founation. http://www.jivdayafound.org/maternal-health/ .

Chhugani M, Khalid M, James MM, et al. Experiences of nurses on implementation of a mobile partograph: a novel tool supporting safer deliveries in India. Int J Nurs Midwif Res. 2016;3(4):32–9.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sir HN Reliance Foundation Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, India

Asha R. Dalal

Purandare’s Chowpatty Maternity and Gynecological Hospital, 31/C, Dr N A Purandare Marg, Chowpatty Seaface, Mumbai, 400007, India

Ameya C. Purandare

K J Somaiya Medical College and Superspeciality Hospital, Mumbai, India

Bhatia General Hospital, Mumbai, India

Masina Hospital, Apollo Spectra Hospital, Mumbai, India

Police Hospital, Mumbai, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ameya C. Purandare .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Professor Asha R. Dalal is the MD, DGO, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynecologist, Head in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sir HN Reliance Foundation Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, India, and Dr. Ameya C. Purandare, MD, DNBE, FICOG, FCPS, DGO, DFP, MNAMS, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynecologist in Purandare’s Chowpatty Maternity and Gynecological Hospital, K J Somaiya Medical College and Superspeciality Hospital, Bhatia General Hospital, Masina Hospital, Apollo Spectra Hospital, Police Hospital, Mumbai.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dalal, A.R., Purandare, A.C. The Partograph in Childbirth: An Absolute Essentiality or a Mere Exercise?. J Obstet Gynecol India 68 , 3–14 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-017-1051-y

Download citation

Received : 27 July 2017

Accepted : 06 September 2017

Published : 16 October 2017

Issue Date : February 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-017-1051-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Labor monitoring

- Normal labor

- Abnormal labor

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Brief / Fact Sheet

Aug 1, 2013

Capacity Development/Training | Intrapartum Care

How to Use the Partograph

Related Topics

Organizations, subscribe to our newsletter.

HOW TO USE A PARTOGRAPH A vital tool for the care of every woman in labour. The partograph is a graphic record of vital observations during the course of labour in order to assess its progress and carry out appropriate interventions if and when necessary. Correct use of the partograph can help prevent and manage prolonged or obstructed labour and serious complications, including ruptured uterus, obstetric fistula, and stillbirth. The partograph was developed in Africa (Zimbabwe in about 1970) and has become adopted worldwide.

This film forms part of a growing set of films on Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care for skilled health workers. As well as seeking medical and midwifery expert opinions, the following teaching materials were used in the making of these films – WHO/UNICEF/THET/Somaliland MoH EmONC trainng protocols 2012 – RCOG (Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) Life Saving Skills Manual: Essential Obstetric and Newborn Care – RCOG PROMPT Manual (PRactical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training) – Resuscitation Council (UK) Guidelines© Medical Aid Films 2013

Attribution + Noncommercial + NoDerivatives

Related Resources

Journal Article

Mar 6, 2024

Capacity Development/Training | Complications

How Much Training Is Enough? Low-Dose, High-Frequency Simulation Training and Maintenance of Competence in Neonatal Resuscitation

Feb 27, 2024

Newborn resuscitation timelines: Accurately capturing treatment in the delivery room

Jan 26, 2024

Capacity Development/Training | Data/Statistics

Improvements in Obstetric and Newborn Health Information Documentation following the Implementation of the Safer Births Bundle of Care at 30 Facilities in Tanzania

Jan 10, 2024

Respectful Care | Intrapartum Care

Women’s experience of childbirth care in health facilities: a qualitative assessment of respectful maternity care in Afghanistan

We have a new look and feel!

We may look different, but we have not lost the essence of who we are; a learning platform that provides evidence-based knowledge to those working to ensure that newborns survive and thrive. We’d love to hear what you think of the new HNN!

Contact us!

- Open access

- Published: 22 March 2021

The development of the WHO Labour Care Guide: an international survey of maternity care providers

- Veronica Pingray ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7889-2825 1 ,

- Mercedes Bonet 2 ,

- Mabel Berrueta 1 ,

- Agustina Mazzoni 1 ,

- María Belizán 1 ,

- Netanya Keil 3 ,

- Joshua Vogel 4 ,

- Fernando Althabe 2 &

- Olufemi T. Oladapo 2

Reproductive Health volume 18 , Article number: 66 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7191 Accesses

10 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

The partograph is the most commonly used labour monitoring tool in the world. However, it has been used incorrectly or inconsistently in many settings. In 2018, a WHO expert group reviewed and revised the design of the partograph in light of emerging evidence, and they developed the first version of the Labour Care Guide (LCG). The objective of this study was to explore opinions of skilled health personnel on the first version of the WHO Labour Care Guide.

Skilled health personnel (including obstetricians, midwives and general practitioners) of any gender from Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America were identified through a large global research network. Country coordinators from the network invited 5 to 10 mid-level and senior skilled health personnel who had worked in labour wards anytime in the last 5 years. A self-administered, anonymous, structured, online questionnaire including closed and open-ended questions was designed to assess the clarity, relevance, appropriateness of the frequency of recording, and the completeness of the sections and variables on the LCG.

A total of 110 participants from 23 countries completed the survey between December 2018 and January 2019. Variables included in the LCG were generally considered clear, relevant and to have been recorded at the appropriate frequency. Most sections of the LCG were considered complete. Participants agreed or strongly agreed with the overall design, structure of the LCG, and the usefulness of reference thresholds to trigger further assessment and actions. They also agreed that LCG could potentially have a positive impact on clinical decision-making and respectful maternity care. Participants disagreed with the value of some variables, including coping, urine, and neonatal status.

Conclusions

Future end-users of WHO Labour Care Guide considered the variables to be clear, relevant and appropriate, and, with minor improvements, to have the potential to positively impact clinical decision-making and respectful maternity care.

Antecedentes

El partograma es la herramienta para el monitoreo del trabajo de parto más utilizada a nivel mundial. Sin embargo, en muchos entornos se utiliza de manera incorrecta o inconsistente. En 2018, un grupo de expertos de la OMS evaluó y modificó el diseño del partograma teniendo en cuenta la nueva evidencia científica, y elaboró la primera versión de la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar las perspectivas y opiniones de los profesionales de la salud sobre la primera versión de la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto.

Se identificó a profesionales de salud de servicios de maternidad (incluidos obstetras, parteras profesionales y médicos generalistas) de cualquier género de África, Asia, Europa y América Latina a través de una red de investigación internacional. Los coordinadores de países de la red invitaron entre 5 y 10 profesionales con nivel de experiencia media o avanzada que hubieran trabajado en servicios de maternidad en los últimos 5 años. Se diseñó un cuestionario en línea, autoadministrado, anónimo y estructurado que incluía preguntas cerradas y abiertas para evaluar la claridad, la pertinencia, la adecuación de la frecuencia de registro y la exhaustividad de las secciones y variables de la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto.

Un total de 110 participantes de 23 países completaron la encuesta entre diciembre de 2018 y enero de 2019. Las variables incluidas en la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto se consideraron en general claras, pertinentes y con una frecuencia de registro apropiada. La mayoría de las secciones de la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto se consideraron completas. Los participantes estuvieron de acuerdo o muy de acuerdo con el diseño general, la estructura de la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto, y la utilidad de los umbrales de referencia para desencadenar evaluaciones y acciones adicionales. También estuvieron de acuerdo en que la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto tendrá un impacto positivo en la toma de decisiones clínicas y en el cuidado respetuoso. Los participantes no estuvieron de acuerdo con algunos parámetros propuestos en la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto, incluyendo el manejo de la situación por parte de las mujeres, parámetros urinarios y el estado neonatal.

Conclusiones

Los futuros usuarios de la Guía para la Atención del Trabajo de Parto consideraron que las variables eran claras, pertinentes y apropiadas, y que, con pequeñas mejoras, podría tener un impacto positivo en la toma de decisiones clínicas y la atención respetuosa del parto.

Le partogramme est l'outil de suivi du travail le plus couramment utillis dans le monde. Cependant, il est utilisé de façon incorrecte ou non uniforme dans de nombreux contextes. En 2018, un groupe d'experts de l'OMS a examiné et révisé la conception du partogramme à la lumière de nouvelles données et a développé la première version du Guide de Gestion du Travail. L'objectif de cette étude était d'explorer les points de vue et les opinions du personnel de santé qualifié sur la première version du Guide de Gestion du Travail de l'OMS.

Un vaste réseau mondial de recherche a permis d'identifier le personnel de santé qualifié (y compris des obstétriciens, des sages-femmes et des médecins généralistes) des deux sexes, en Afrique, Asie, Europe et en Amérique latine. Les coordinateurs nationaux du réseau ont invité entre 5 et 10 personnels de santé qualifiés de niveau intermédiaire à supérieur, et ayant travaillé dans des services de maternité à au cours des 5 dernières années. Un questionnaire en ligne, structuré, anonyme et à remplir soi-même, comprenant des questions fermées et ouvertes, a été conçu pour évaluer la clarté, la pertinence, la convenance de la fréquence d'enregistrement et l’intégrité des variables du Guide de Gestion du Travail.

Au total, 110 participants de 23 pays ont répondu à l'enquête entre décembre 2018 et janvier 2019. Les variables incluses dans le Guide de Gestion du Travail ont t généralement considérées claires, pertinentes et avec une fréquence d'enregistrement appropriée. La plupart des sections du Guide de Gestion du Travail sont considérées complètes. Les participants ont approuvé ou fortement approuvé le concept générale, la structure du Guide de Gestion du Travail et l'utilité des seuils de référence pour déclencher une évaluation et des actions supplémentaires. Ils ont également convenu que le Guide de Gestion du Travail aura potentiellement un impact positif sur les prise de décisions cliniques et les soins maternels respectueux. Les personnes interrogées ont exprimé leur désaccord avec la valeur de certaines variables, notamment la capacité d'adaptation, l'urine et l'état néonatal.

Les futurs utilisateurs du le Guide de Gestion du Travail ont estimé que les variables étaient claires, pertinentes et appropriées, et qu'elles pourraient avoir un impact positif sur la prise de décision clinique et les soins de maternit respectueux, moyennant quelques améliorations mineures.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

During the past 20 years, skilled birth attendance has been promoted widely to reduce preventable maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity [ 1 ]. This has translated into large increases in both the coverage of births attended by skilled health personnel (62% in 2000 to 80% in 2017), and facility-based births [ 1 ]. However, these increases in coverage have not always translated into the expected reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity during labour and childbirth, suggesting that suboptimal quality of care is still prevalent in health facilities [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Regular monitoring of labour and childbirth is vital to identifying risks or complications and to preventing adverse birth outcomes.

The partograph is the most commonly used labour monitoring tool, and it has been used for over 40 years by skilled health personnel providing care during labour. However, in light of the publication of the 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience, the partograph required a revision to facilitate care according to emerging evidence and global priorities [ 7 ]. These WHO recommendations include new definitions and durations of the first and second stages of labour, and they highlight the importance of woman-centred care to optimize the experience of labour and childbirth for women and their babies.

WHO therefore initiated the development of a “next-generation” partograph, known as the WHO Labour Care Guide (LCG) (Additional file 1 - First version of the LCG) with the following purposes: (a) continuously remind practitioners to offer supportive care throughout labour and childbirth, and remind them of what observations should be regularly made during labour to identify any emerging complication in mother and/or baby; (b) provide reference thresholds for abnormal labour observations that should trigger specific actions; (c) minimize over-diagnosis and under-diagnosis of abnormal labour events and the unnecessary use of interventions; and (d) support audits and quality of labour care improvement.

It is critical that the LCG includes appropriate parameters for labour monitoring and that it can meet the needs of maternity care providers. The findings from this research are intended to support a revision process that will improve the LCG. The objective of this study was to explore perspectives of skilled health personnel on the first version of the LCG.

We conducted an international cross-sectional survey among skilled health personnel who were actively providing labour and childbirth care in a health facility. Participating skilled health personnel were asked about their opinions on the clarity, relevance, appropriateness of the frequency of recording, and the completeness of each section of the first version of the LCG. All participants consented to participating in the survey.

The first version of the LCG was organized into eight sections. The first section was for identification , specifically related to the time of diagnosis of active phase of labour, while the other sections were related to different categories of care provided throughout labour and childbirth: supportive care (companion, coping, pain relief, oral fluid and posture), care of the baby (baseline fetal heart rate (FHR), FHR deceleration, amniotic fluid, fetal position, caput and moulding), care of the mother (pulse, blood pressure, temperature and urine), labour progress (uterine contractions in 10 min, duration of contractions, cervix, and descent), medication (oxytocin, medicine, IV fluid), shared decision-making (assessment and plan), and birth outcomes (mode of birth, Apgar score at 5 min, blood loss, neonatal status and birthweight).

Participants and sample

Skilled health personnel providing care during labour and childbirth (obstetricians, midwives and general practitioners) of any gender from four world regions—Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America—were invited to participate. We targeted mid-level and senior providers who were currently practicing or had been working in labour wards during the previous 5 years. Eligible individuals were those who expressed their interest in participating, were fluent in English, French or Spanish, and provided consent to participate.

Participants were identified through the WHO Global Maternal Sepsis Study (GLOSS) research network [ 8 ]. Study coordinators from 23 countries of GLOSS research network, out of 30 invited, were involved in the selection and invitation of 5 to 10 skilled health personnel in their country/area of study. Country coordinators were encouraged to provide a diverse sample of skilled health personnel, based on the relevant cadres in their area.

A semi-structured questionnaire was designed, including closed and open-ended questions. The questionnaire was pretested among four maternal health researchers, using cognitive interviews for assessing its face-validity. Additionally, 12 English-proficient practicing obstetricians participated in a pilot study to assess length, clarity and relevance of the items of the questionnaire. Once the pilot was completed, a final revision of the instrument was made.

The online survey (via Survey Monkey™) was self-administered and anonymous (see Additional file 2 : Online questionnaire). It assessed the clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of the frequency of recording and completeness of each of the eight sections of the LCG. The clarity and relevance of variables included in the LCG were rated on a 9-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very unclear or not relevant) to 9 (very clear and extremely relevant). The completeness of each section was assessed by asking participants if any other relevant variables should be added. Agreement regarding appropriateness of the frequency of recording was measured on a 4-point Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree. Participants were also asked to provide their views on the format of open-text variables in the LCG, and to provide comments on each section. Finally, there was a section for the general assessment of the LCG, including: providers’ opinions on the overall structure and organization of the LCG, clarity of instructions and abbreviations. The survey also asked about participants’ perceptions of its possible impact on clinical decision-making and respectful maternity care, and the usefulness of reference thresholds to trigger further assessment and necessary actions. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into French and Spanish.

An invitation to participate in the survey was sent in December 2018 to 142 providers identified through GLOSS country coordinators. Among invited providers, 114 confirmed their interest and availability to participate in the online survey. Three reminders were sent to participants with partial or no responses over a 6-week period. Completeness and consistency between the survey items were monitored during survey administration.

Data analysis