- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

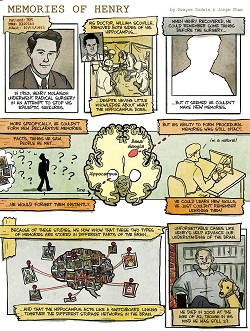

Key Study: HM’s case study (Milner and Scoville, 1957)

Travis Dixon January 29, 2019 Biological Psychology , Cognitive Psychology , Key Studies

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

HM’s case study is one of the most famous and important case studies in psychology, especially in cognitive psychology. It was the source of groundbreaking new knowledge on the role of the hippocampus in memory.

Background Info

“Localization of function in the brain” means that different parts of the brain have different functions. Researchers have discovered this from over 100 years of research into the ways the brain works. One such study was Milner’s case study on Henry Molaison.

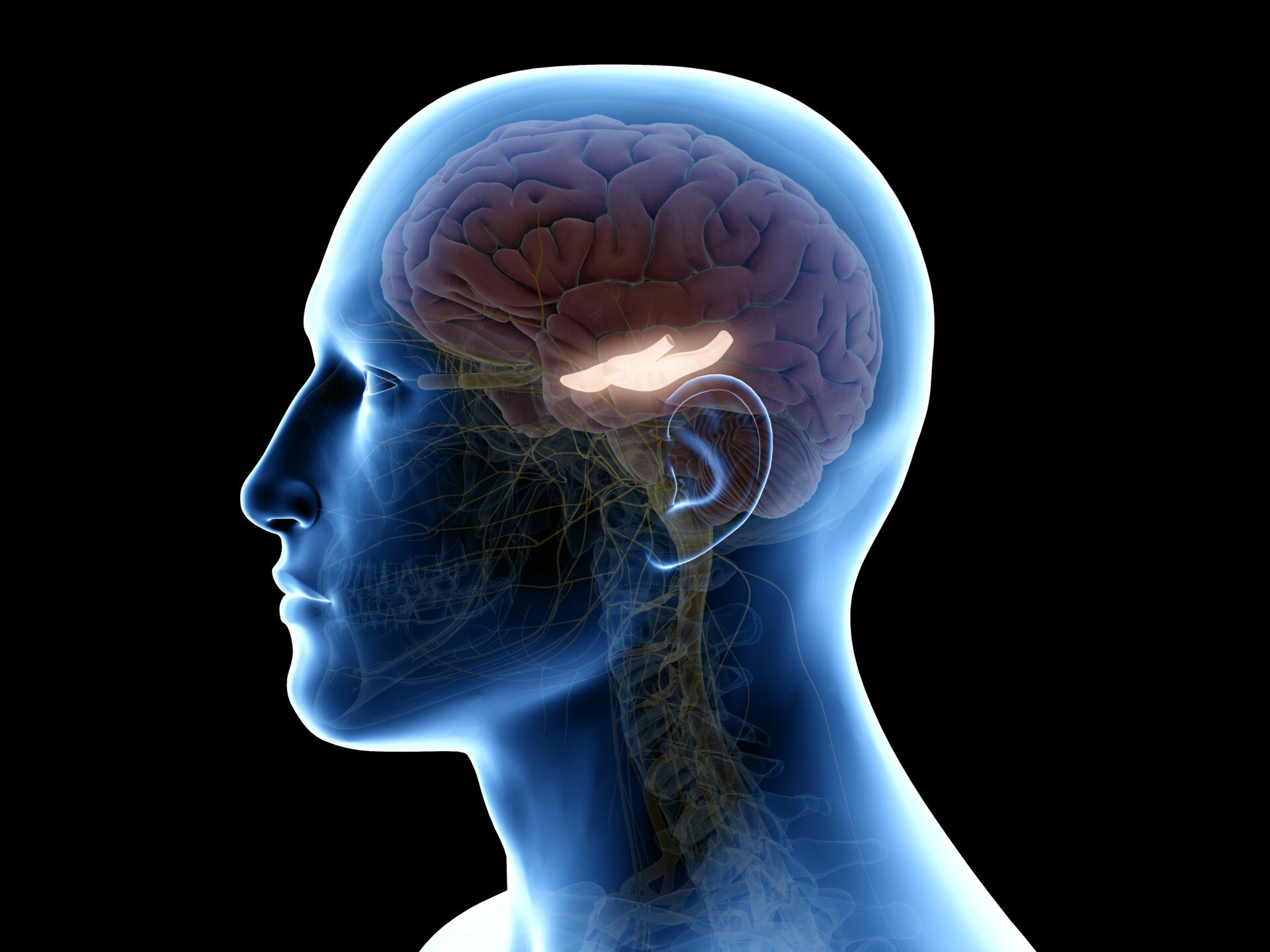

The memory problems that HM experienced after the removal of his hippocampus provided new knowledge on the role of the hippocampus in memory formation (image: wikicommons)

At the time of the first study by Milner, HM was 29 years old. He was a mechanic who had suffered from minor epileptic seizures from when he was ten years old and began suffering severe seizures as a teenager. These may have been a result of a bike accident when he was nine. His seizures were getting worse in severity, which resulted in HM being unable to work. Treatment for his epilepsy had been unsuccessful, so at the age of 27 HM (and his family) agreed to undergo a radical surgery that would remove a part of his brain called the hippocampus . Previous research suggested that this could help reduce his seizures, but the impact it had on his memory was unexpected. The Doctor performing the radical surgery believed it was justified because of the seriousness of his seizures and the failures of other methods to treat them.

Methods and Results

In one regard, the surgery was successful as it resulted in HM experiencing less seizures. However, immediately after the surgery, the hospital staff and HM’s family noticed that he was suffering from anterograde amnesia (an inability to form new memories after the time of damage to the brain):

Here are some examples of his memory loss described in the case study:

- He could remember something if he concentrated on it, but if he broke his concentration it was lost.

- After the surgery the family moved houses. They stayed on the same street, but a few blocks away. The family noticed that HM as incapable of remembering the new address, but could remember the old one perfectly well. He could also not find his way home alone.

- He could not find objects around the house, even if they never changed locations and he had used them recently. His mother had to always show him where the lawnmower was in the garage.

- He would do the same jigsaw puzzles or read the same magazines every day, without ever apparently getting bored and realising he had read them before. (HM loved to do crossword puzzles and thought they helped him to remember words).

- He once ate lunch in front of Milner but 30 minutes later was unable to say what he had eaten, or remember even eating any lunch at all.

- When interviewed almost two years after the surgery in 1955, HM gave the date as 1953 and said his age was 27. He talked constantly about events from his childhood and could not remember details of his surgery.

Later testing also showed that he had suffered some partial retrograde amnesia (an inability to recall memories from before the time of damage to the brain). For instance, he could not remember that one of his favourite uncles passed away three years prior to his surgery or any of his time spent in hospital for his surgery. He could, however, remember some unimportant events that occurred just before his admission to the hospital.

Brenda Milner studied HM for almost 50 years – but he never remembered her.

Results continued…

His memories from events prior to 1950 (three years before his surgery), however, were fine. There was also no observable difference to his personality or to his intelligence. In fact, he scored 112 points on his IQ after the surgery, compared with 104 previously. The IQ test suggested that his ability in arithmetic had apparently improved. It seemed that the only behaviour that was affected by the removal of the hippocampus was his memory. HM was described as a kind and gentle person and this did not change after his surgery.

The Star Tracing Task

In a follow up study, Milner designed a task that would test whether or not HMs procedural memory had been affected by the surgery. He was to trace an outline of a star, but he could only see the mirrored reflection. He did this once a day over a period of a few days and Milner observed that he became faster and faster. Each time he performed the task he had no memory of ever having done it before, but his performance kept improving. This is further evidence for localization of function – the hippocampus must play a role in declarative (explicit) memory but not procedural (implicit) memory.

Cognitive psychologists have categorized memories into different types. HM’s study suggests that the hippocampus is essential for explicit (conscious) and declarative memory, but not implicit (unconscious) procedural memory.

Was his memory 100% gone? Another follow-up study

Interestingly, HM showed signs of being able to remember famous people who had only become famous after his surgery, like Lee Harvey Oswald (who assassinated JFK in 1963). (Image: wikicommons)

Another fascinating follow-up study was conducted by two researchers who wanted to see if HM had learned anything about celebrities that became famous after his surgery. At first they tested his knowledge of celebrities from before his surgery, and he knew these just as well as controls. They then showed him two names at a time, one a famous name (e.g. Liza Minelli, Lee Harvey Oswald) and the other was a name randomly taken from the phonebook. He was asked to choose the famous name and he was correct on a significant number of trials (i.e. the statistics tests suggest he wasn’t just guessing). Even more incredible was that he remembered some details about these people when asked why they were famous. For example, he could remember that Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated the president. One explanation given for the memory of these facts is that there was an emotional component. E.g. He liked these people, or the assassination was so violent, that he could remember a few details.

HM became a hugely important case study for neuro and cognitive Psychologists. He was interviewed and tested by over 100 psychologists during the 53 years after his operation. Directly after his surgery, he lived at home with his parents as he was unable to live independently. He moved to a nursing home in 1980 and stayed there until his death in 2008. HM donated his brain to science and it was sliced into 2,401 thin slices that will be scanned and published electronically.

Critical Thinking Considerations

- How does this case study demonstrate localization of function in the brain? (e.g.c reating new long-term memories; procedural memories; storing and retrieving long term memories; intelligence; personality) ( Application )

- What are the ethical considerations involved in this study? ( Analysis )

- What are the strengths and limitations of this case study? ( Evaluation )

- Why would ongoing studies of HM be important? (Think about memory, neuroplasticity and neurogenesis) ( Analysis/Synthesis/Evaluation )

- How can findings from this case study be used to support and/or challenge the Multi-store Model of Memory? ( Application / Synthesis/Evaluation )

Exam Tips This study can be used for the following topics: Localization – the role of the hippocampus in memory Techniques to study the brain – MRI has been used to find out the exact location and size of damage to HM’s brain Bio and cognitive approach research method s – case study Bio and cognitive approach ethical considerations – anonymity Emotion and cognition – the follow-up study on HM and memories of famous people could be used in an essay to support the idea that emotion affects memory Models of memory – the multi-store model : HM’s study provides evidence for the fact that our memories all aren’t formed and stored in one place but travel from store to store (because his transfer from STS to LTS was damaged – if it was all in one store this specific problem would not occur)

Milner, Brenda. Scoville, William Beecher. “Loss of Recent Memory after Bilateral Hippocampal Lesions”. The Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1957; 20: 11 21. (Accessed from web.mit.edu )

The man who couldn’t remember”. nova science now. an interview with brenda corkin . 06.01.2009. .

Here’s a good video recreation documentary of HM’s case study…

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

Henry Gustav Molaison: The Curious Case of Patient H.M.

Erin Heaning

Clinical Safety Strategist at Bristol Myers Squibb

Psychology Graduate, Princeton University

Erin Heaning, a holder of a BA (Hons) in Psychology from Princeton University, has experienced as a research assistant at the Princeton Baby Lab.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Henry Gustav Molaison, known as Patient H.M., is a landmark case study in psychology. After a surgery to alleviate severe epilepsy, which removed large portions of his hippocampus , he was left with anterograde amnesia , unable to form new explicit memories , thus offering crucial insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory formation.

- Henry Gustav Molaison (often referred to as H.M.) is a famous case of anterograde and retrograde amnesia in psychology.

- H. M. underwent brain surgery to remove his hippocampus and amygdala to control his seizures. As a result of his surgery, H.M.’s seizures decreased, but he could no longer form new memories or remember the prior 11 years of his life.

- He lost his ability to form many types of new memories (anterograde amnesia), such as new facts or faces, and the surgery also caused retrograde amnesia as he was able to recall childhood events but lost the ability to recall experiences a few years before his surgery.

- The case of H.M. and his life-long participation in studies gave researchers valuable insight into how memory functions and is organized in the brain. He is considered one of the most studied medical and psychological history cases.

Who is H.M.?

Henry Gustav Molaison, or “H.M” as he is commonly referred to by psychology and neuroscience textbooks, lost his memory on an operating table in 1953.

For years before his neurosurgery, H.M. suffered from epileptic seizures believed to be caused by a bicycle accident that occurred in his childhood. The seizures started out as minor at age ten, but they developed in severity when H.M. was a teenager.

Continuing to worsen in severity throughout his young adulthood, H.M. was eventually too disabled to work. Throughout this period, treatments continued to turn out unsuccessful, and epilepsy proved a major handicap and strain on H.M.’s quality of life.

And so, at age 27, H.M. agreed to undergo a radical surgery that would involve removing a part of his brain called the hippocampus — the region believed to be the source of his epileptic seizures (Squire, 2009).

For epilepsy patients, brain resection surgery refers to removing small portions of brain tissue responsible for causing seizures. Although resection is still a surgical procedure used today to treat epilepsy, the use of lasers and detailed brain scans help ensure valuable brain regions are not impacted.

In 1953, H.M.’s neurosurgeon did not have these tools, nor was he or the rest of the scientific or medical community fully aware of the true function of the hippocampus and its specific role in memory. In one regard, the surgery was successful, as H.M. did, in fact, experience fewer seizures.

However, family and doctors soon noticed he also suffered from severe amnesia, which persisted well past when he should have recovered. In addition to struggling to remember the years leading up to his surgery, H.M. also had gaps in his memory of the 11 years prior.

Furthermore, he lacked the ability to form new memories — causing him to perpetually live an existence of moment-to-moment forgetfulness for decades to come.

In one famous quote, he famously and somberly described his state as “like waking from a dream…. every day is alone in itself” (Squire et al., 2009).

H.M. soon became a major case study of interest for psychologists and neuroscientists who studied his memory deficits and cognitive abilities to better understand the hippocampus and its function.

When H.M. died on December 2, 2008, at the age of 82, he left behind a lifelong legacy of scientific contribution.

Surgical Procedure

Neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville performed H.M.’s surgery in Hartford, Connecticut, in August 1953 when H.M. was 27 years old.

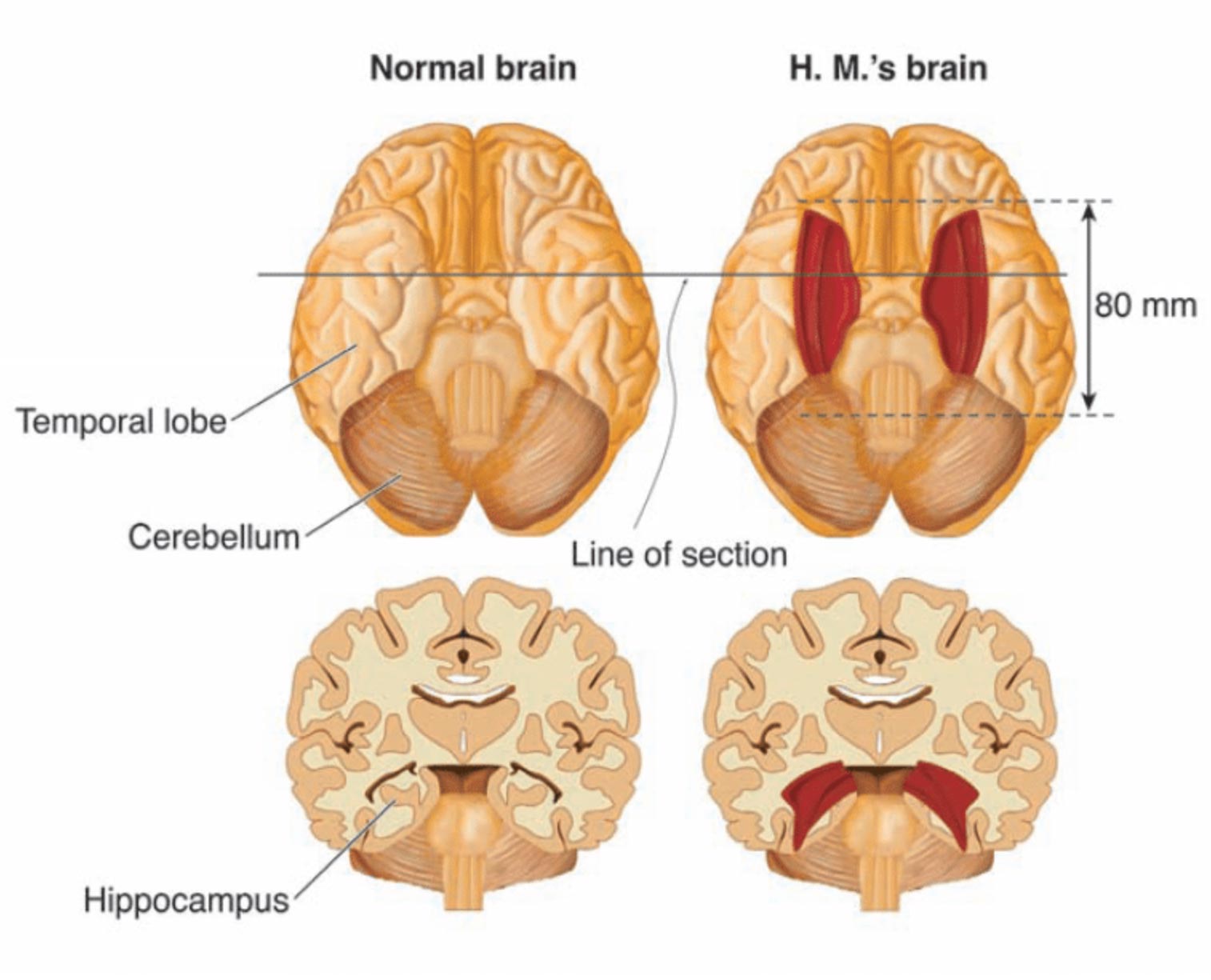

During the procedure, Scoville removed parts of H.M.’s temporal lobe which refers to the portion of the brain that sits behind both ears and is associated with auditory and memory processing.

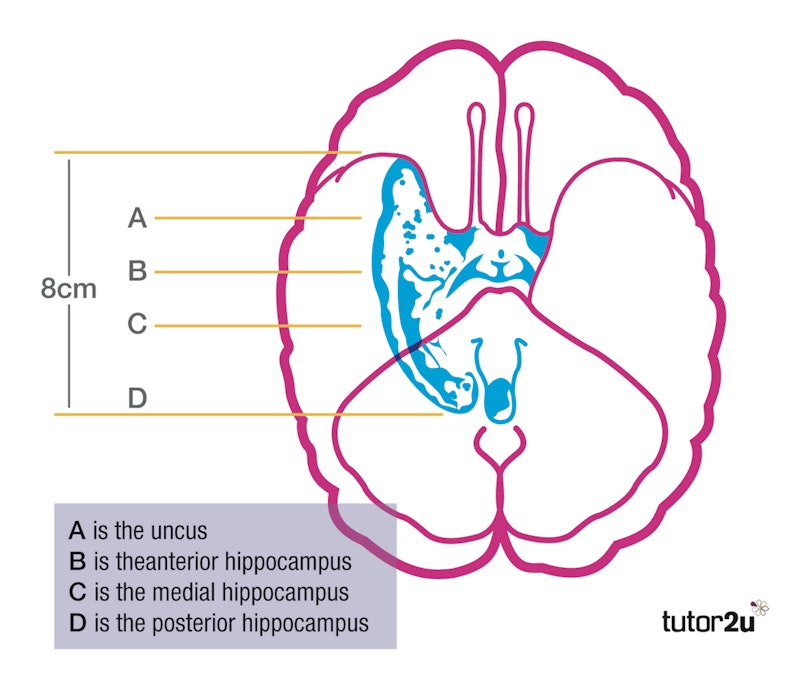

More specifically, the surgery involved what was called a “partial medial temporal lobe resection” (Scoville & Milner, 1957). In this resection, Scoville removed 8 cm of brain tissue from the hippocampus — a seahorse-shaped structure located deep in the temporal lobe .

Bilateral resection of the anterior temporal lobe in patient HM.

Further research conducted after this removal showed Scoville also probably destroyed the brain structures known as the “uncus” (theorized to play a role in the sense of smell and forming new memories) and the “amygdala” (theorized to play a crucial role in controlling our emotional responses such as fear and sadness).

As previously mentioned, the removal surgery partially reduced H.M.’s seizures; however, he also lost the ability to form new memories.

At the time, Scoville’s experimental procedure had previously only been performed on patients with psychosis, so H.M. was the first epileptic patient and showed no sign of mental illness. In the original case study of H.M., which is discussed in further detail below, nine of Scoville’s patients from this experimental surgery were described.

However, because these patients had disorders such as schizophrenia, their symptoms were not removed after surgery.

In this regard, H.M. was the only patient with “clean” amnesia along with no other apparent mental problems.

H.M’s Amnesia

H.M.’s apparent amnesia after waking from surgery presented in multiple forms. For starters, H.M. suffered from retrograde amnesia for the 11-year period prior to his surgery.

Retrograde describes amnesia, where you can’t recall memories that were formed before the event that caused the amnesia. Important to note, current research theorizes that H.M.’s retrograde amnesia was not actually caused by the loss of his hippocampus, but rather from a combination of antiepileptic drugs and frequent seizures prior to his surgery (Shrader 2012).

In contrast, H.M.’s inability to form new memories after his operation, known as anterograde amnesia, was the result of the loss of the hippocampus.

This meant that H.M. could not learn new words, facts, or faces after his surgery, and he would even forget who he was talking to the moment he walked away.

However, H.M. could perform tasks, and he could even perform those tasks easier after practice. This important finding represented a major scientific discovery when it comes to memory and the hippocampus. The memory that H.M. was missing in his life included the recall of facts, life events, and other experiences.

This type of long-term memory is referred to as “explicit” or “ declarative ” memories and they require conscious thinking.

In contrast, H.M.’s ability to improve in tasks after practice (even if he didn’t recall that practice) showed his “implicit” or “ procedural ” memory remained intact (Scoville & Milner, 1957). This type of long-term memory is unconscious, and examples include riding a bike, brushing your teeth, or typing on a keyboard.

Most importantly, after removing his hippocampus, H.M. lost his explicit memory but not his implicit memory — establishing that implicit memory must be controlled by some other area of the brain and not the hippocampus.

After the severity of the side effects of H.M.’s operation became clear, H.M. was referred to neurosurgeon Dr. Wilder Penfield and neuropsychologist Dr. Brenda Milner of Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) for further testing.

As discussed, H.M. was not the only patient who underwent this experimental surgery, but he was the only non-psychotic patient with such a degree of memory impairment. As a result, he became a major study and interest for Milner and the rest of the scientific community.

Since Penfield and Milner had already been conducting memory experiments on other patients at the time, they quickly realized H.M.’s “dense amnesia, intact intelligence, and precise neurosurgical lesions made him a perfect experimental subject” (Shrader 2012).

Milner continued to conduct cognitive testing on H.M. for the next fifty years, primarily at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Her longitudinal case study of H.M.’s amnesia quickly became a sensation and is still one of the most widely-cited psychology studies.

In publishing her work, she protected Henry’s identity by first referring to him as the patient H.M. (Shrader 2012).

In the famous “star tracing task,” Milner tested if H.M.’s procedural memory was affected by the removal of the hippocampus during surgery.

In this task, H.M. had to trace an outline of a star, but he could only trace the star based on the mirrored reflection. H.M. then repeated this task once a day over a period of multiple days.

Over the course of these multiple days, Milner observed that H.M. performed the test faster and with fewer errors after continued practice. Although each time he performed the task, he had no memory of having participated in the task before, his performance improved immensely (Shrader 2012).

As this task showed, H.M. had lost his declarative/explicit memory, but his unconscious procedural/implicit memory remained intact.

Given the damage to his hippocampus in surgery, researchers concluded from tasks such as these that the hippocampus must play a role in declarative but not procedural memory.

Therefore, procedural memory must be localized somewhere else in the brain and not in the hippocampus.

H.M’s Legacy

Milner’s and hundreds of other researchers’ work with H.M. established fundamental principles about how memory functions and is organized in the brain.

Without the contribution of H.M. in volunteering the study of his mind to science, our knowledge today regarding the separation of memory function in the brain would certainly not be as strong.

Until H.M.’s watershed surgery, it was not known that the hippocampus was essential for making memories and that if we lost this valuable part of our brain, we would be forced to live only in the moment-to-moment constraints of our short-term memory .

Once this was realized, the findings regarding H.M. were widely publicized so that this operation to remove the hippocampus would never be done again (Shrader 2012).

H.M.’s case study represents a historical time period for neuroscience in which most brain research and findings were the result of brain dissections, lesioning certain sections, and seeing how different experimental procedures impacted different patients.

Therefore, it is paramount we recognize the contribution of patients like H.M., who underwent these dangerous operations in the mid-twentieth century and then went on to allow researchers to study them for the rest of their lives.

Even after his death, H.M. donated his brain to science. Researchers then took his unique brain, froze it, and then in a 53-hour procedure, sliced it into 2,401 slices which were then individually photographed and digitized as a three-dimensional map.

Through this map, H.M.’s brain could be preserved for posterity (Wb et al., 2014). As neuroscience researcher Suzanne Corkin once said it best, “H.M. was a pleasant, engaging, docile man with a keen sense of humor, who knew he had a poor memory but accepted his fate.

There was a man behind the data. Henry often told me that he hoped that research into his condition would help others live better lives. He would have been proud to know how much his tragedy has benefitted science and medicine” (Corkin, 2014).

Corkin, S. (2014). Permanent present tense: The man with no memory and what he taught the world. Penguin Books.

Hardt, O., Einarsson, E. Ö., & Nader, K. (2010). A bridge over troubled water: Reconsolidation as a link between cognitive and neuroscientific memory research traditions. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 141–167.

Scoville, W. B., & Milner, B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions . Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 20 (1), 11.

Shrader, J. (2012, January). HM, the man with no memory | Psychology Today. Retrieved from, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/trouble-in-mind/201201/hm-the-man-no-memory

Squire, L. R. (2009). The legacy of patient H. M. for neuroscience . Neuron, 61 , 6–9.

Related Articles

Famous Experiments , Social Science

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

Famous Experiments , Learning Theories

Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment on Social Learning

Famous Experiments

John Money Gender Experiment: Reimer Twins

Famous Experiments , Child Psychology

Van Ijzendoorn & Kroonenberg: Cultural Variations in Attachment

Dement and Kleitman (1957)

Held and Hein (1963) Kitten carosel

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Research News

H.m.'s brain and the history of memory.

Brian Newhouse

In 1953, radical brain surgery was used on a patient with severe epilepsy. The operation on "H.M." worked, but left him with almost no long-term memory. H.M. is now in his 80s. His case has helped scientists understand much more about the brain.

Web Resources

Copyright © 2007 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Brain Development

- Childhood & Adolescence

- Diet & Lifestyle

- Emotions, Stress & Anxiety

- Learning & Memory

- Thinking & Awareness

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Childhood Disorders

- Immune System Disorders

- Mental Health

- Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Infectious Disease

- Neurological Disorders A-Z

- Body Systems

- Cells & Circuits

- Genes & Molecules

- The Arts & the Brain

- Law, Economics & Ethics

- Neuroscience in the News

- Supporting Research

- Tech & the Brain

- Animals in Research

- BRAIN Initiative

- Meet the Researcher

- Neuro-technologies

- Tools & Techniques

Core Concepts

- For Educators

- Ask an Expert

- The Brain Facts Book

Patient Zero: What We Learned from H.M.

- Published 16 May 2013

- Author Dwayne Godwin

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Memory is our most prized human treasure. It defines our sense of self, and our ability to navigate the world. It defines our relationships with others – for good or ill – and is so important to survival that our gilled ancestors bear the secret of memory etched in their DNA. If you asked someone over 50 to name the things they most fear about getting older, losing one’s memory would be near the top of that list. There is so much worry over Alzheimer’s disease, the memory thief, that it is easy to forget that our modern understanding of memory is still quite young, less than one, very special lifespan.

Meet the Patient Zero of memory disorders, H.M.

H.M. was the pseudonym of Henry Molaison, a man who was destined to change the way we think about the brain. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient H.M. is a touching, comprehensive view of his life through the eyes of a researcher who also, in a sense, became part of his family.

The prologue opens with a conversation between the author, Suzanne Corkin, and Molaison in 1992. It reads a bit like a first meeting of two strangers, but then Corkin reveals a jarring truth: this meeting was one of many similar encounters they’d had over 30 years.

By now, if you’re interested in learning and memory you probably know the basics of Henry Molaison’s story. He had epilepsy from an early age that was thought to be acquired through head trauma from a bike accident (though apparently family members also had epilepsy). His surgeon, William B. Scoville (who in a remarkable twist, was a childhood neighbor of Suzanne Corkin) removed Henry’s hippocampus and amygdala in both hemispheres of his brain, in an attempt to control his seizures.

The results of the surgery are legendary. While Henry’s seizures were controlled, he suffered a type of profound anterograde amnesia that prevented him from encoding new memories, but spared certain details of his life leading up to the surgery. Henry would have no memory of those he worked with from day to day, or of new information he might encounter. The book’s title, “Permanent Present Tense”, describes his zen-like existence within the thirty or so seconds around the present moment, which was the limit of Henry’s short term memory.

If this book were a movie or video game, it would be said to be full of “Easter eggs”. There are vignettes and bits of unexpected information that add rich historical context to the state of knowledge in Molaison’s time. These include a digression on the history of neurosurgery, including the gruesome history of lobotomies and the advances brought to the field of neurosurgery by Wilder Penfield. In many ways, H.M.’s legend is a product of a unique scientific lineage – Scoville owed much to Penfield, who in turn trained under Charles Sherrington (he who gave “synapse” to the neuroscience lexicon), and Brenda Milner, who trained under Donald Hebb (who spawned our current notion of activity-dependent plasticity, embodied by the phrase, “cells that fire together wire together”).

The book also reminds us that H.M. was not the first amnesic patient produced through neurosurgical interventions to treat intractable epilepsy, but he was by far the most studied. The book conveys a sense of wonder at the accomplishments of scientists and physicians, charting terra incognita with scalpels, electrical probes and psychological test batteries.

Corkin recounts Henry Molaison’s early life, including key events - like a childhood plane ride that Henry remembered after his surgery - with gentle but thorough prose. Some of these details come from personal conversations with Henry, while others are the result of careful reporting and research.

The book is an accessible master class in learning and memory, with details and key milestones culled from Corkin’s decades of experience as a memory researcher. The details are not so burdensome as to be esoteric, nor so simple as to be trivial. The book gives only a brief overview of the growing field of knowledge about the cellular mechanisms supporting learning and memory (which might be lost on a casual reader), but this is wisely offset by the details of functional anatomy gleaned from Henry and other patients, and a solid explanation of how we encode, store and retrieve memories.

A light, scholarly tone is maintained throughout the book, but it occasionally brushes up against the deeply personal. It’s difficult to hear Henry’s story and not wonder (or actually, worry) about how it was to live as Henry lived, trapped in the moment. Corkin is reassuring on this point:

“When we consider how much of the anxiety and pain of daily life stems from attending to our long-term memories and worrying about and planning for the future, we can appreciate why Henry lived much of his life with little stress…in the simplicity of a world bounded by thirty seconds.”[p. 75].

In other words, the very thing that might cause Henry to fret about his condition was missing. Henry’s tragedy, it seems, is in the mind of the beholder. Another interesting passage concerns Henry’s moods – which were usually happy and content, but could occasionally be sad or uneasy. This is interesting given the removal during his surgery of a major part of his emotional processing circuitry of the brain, called the amygdala.

Henry Molaison’s anterograde amnesia was practically absolute. However, something not often noted is that he would occasionally surprise those studying him by recalling something he should not be able to remember - for example, colored pictures, or details of celebrities he had heard about after his surgery. Corkin reasons that a bit of spared medial temporal lobe may explain these moments.

Henry was amnesic, but he was not without memory. Through careful behavioral testing, various types of memory function could be uncovered, including recognition memory for having seen images that could persist for months. Corkin suggests that this “memory for the familiar” may have been of some comfort as he navigated what would have otherwise been a confusing experience of reality. New technologies like computers, for example, could be incorporated into his view of the world and did not appear to be jarring to him as would be expected if his capacity for recognizing the familiar did not exist.

Another key discovery from Henry was the finding that he had retained the ability to form non-declarative memories, which took the form of improvement in motor skills. This separate memory system depended on regions of the basal ganglia and motor cortex, which were spared in Henry’s surgery. Testing could improve his performance in the motor task, but his impaired declarative memory system didn’t allow him to remember taking the tests – he could be surprised by his own improvement. Along with his simple recognition memory, motor memory helped smooth challenges Henry faced as he aged, such as learning to use a walker.

Other forms of memory in which Henry showed improvement were in picture completion, where he was able to identify a picture from fragments over a series of sessions, and priming, where previously presented words could prime recognition on presenting fragments of the words. And while Henry is best known for anterograde amnesia, and is sometimes portrayed as having intact memories of things and events before the surgery, he also possessed a partial retrograde amnesia, especially for autobiographical events that happened two years before the surgery - he had only fragmented memories from before that two year window.

Did Henry Molaison have a sense of self? While his was not a fully integrated personality, he possessed “beliefs, desires and values” and seemed capable of a full set of emotions – even without his amygdalae. His view of his own appearance did not seem to cause him distress, even though his estimate of his own age could vary widely. His impairment prevented him from formulating future plans. His basic decency shines through the narrative.

Henry died in 2008 at the age of 82. His brain was scanned postmortem, and extracted for further anatomical analysis . Coming full circle from one of his remaining childhood memories of his first ride, Corkin describes her last wistful goodbye to Henry’s brain as it was conveyed by his final plane ride back to the west coast, where his brain was sliced up into thin sections for new studies. Perhaps the most documented and studied research subject in neuroscience continues to provide vast amounts of data to further our knowledge.

Henry once remarked about his testing, of which he never seemed to become bored since he carried little from one session to the next: “It’s a funny thing – you just live and learn.” He then went on to provide a poignant turn in the familiar phrase: “I’m living, and you’re learning.”

Though he’s no longer living, we’re still learning from Henry.

Permanent Present Tense is a rare look at an amazing mind, whose study formed the basis of our modern science of memory.

Corkin, Suzanne. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, H.M. (Basic Books) May 14, 2013 | ISBN-10: 0465031595 | ISBN-13: 978-0465031597

Update 6/7/2013: NPR interview with Suzanne Corkin on H.M .

Update 1/30/2014: Report on anatomical and histological findings from Henry Molaison: Postmortem examination of patient H.M.’s brain based on histological sectioning and digital 3D reconstruction . J Annese, NM Schenker-Ahmed, H Bartsch, P Maechler, C Sheh, N Thomas, J Kayano, A Ghatan, N Bresler, MP Frosch, R Klaming & S Corkin. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3122

Update 7/6/2016: Statement on informed consent transmitted to me by Suzanne Corkin

About the Author

Dwayne Godwin

Dwayne Godwin is a Professor of Neurobiology and Neurology at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, where he studies epilepsy, sensory processing, withdrawal and PTSD. He coauthors a comic strip on brain topics for Scientific American Mind .

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Learning & Memory

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

Ask An Expert

Ask a neuroscientist your questions about the brain.

Submit a Question

BrainFacts Book

Download a copy of the newest edition of the book, Brain Facts: A Primer on the Brain and Nervous System.

A beginner's guide to the brain and nervous system.

SUPPORTING PARTNERS

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Manage Cookies

Some pages on this website provide links that require Adobe Reader to view.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Continuing Education

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why publish with this journal?

- About Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology

- About the National Academy of Neuropsychology

- Journals Career Network

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Influential case studies, psychosurgery and asylums, temporal lobectomy, controversy, author notes.

- < Previous

Remembering H.M.: Review of “PATIENT H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets”

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David W. Loring, Bruce Hermann, Remembering H.M.: Review of “PATIENT H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets”, Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology , Volume 32, Issue 4, June 2017, Pages 501–505, https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx041

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Although many influential case reports in neuropsychology exist ( Code, Wallesch, Joanette, & Lecours, 1996 ), there are certain patients who stand out because, based upon the historical zeitgeist in which their brain injuries occurred and the attention that those cases received, their neurobehavioral deficits and circumstances of their injury greatly altered our knowledge of brain-behavior relationships.

Among the most famous of these cases is Phineas Gage, the railroad foreman whose personality dramatically changed following frontal lobe injury in 1848 from an accidental explosion that thrust his tamping iron through his skull. Gage's survival after such a serious injury was a surprise, but Gage's contribution to clinical neuroscience was his significant personality change, aptly described by his physicians with the pithy observation, “Gage was no longer Gage” ( Macmillan, 2000 ). Although his personality changes were well documented soon after the accident, much of Gage's long-term outcome may have been exaggerated for entertainment value ( Macmillan & Lena, 2010 ). Thus, the lasting neurobehavioral effects of Gage's frontal lobe injury and how the deficits may have evolved over time remain clouded in the historical record due to the absence independent scientific characterization.

The second patient is Louis Victor Leborgne, whose expressive language disturbance from a left frontal lobe lesion was described in 1861 by the famous French neurologist Pierre Paul Broca. Monsieur Tan, as he was informally called because “tan tan” was his typical verbal output, retained his capacity to understand commands. The deficits of Monsieur Tan, supported by subsequent cases, demonstrated that language could be fractionated into different components associated with distinct brain regions, and that language was predominately a function of the left brain. Monsieur Tan's contribution, however, was in no small part due to Broca's distinguished reputation as a physician and scientist since localized language effects had been previously described by Jean-Baptiste Bouillard ( Sondhaus & Finger, 1988 ).

The third and most studied of these three cases is patient Henry Molaison (H.M.). H.M. suffered a dense and persistent anterograde amnesia following bilateral medial temporal lobectomy in 1953 to treat intractable epilepsy ( Scoville & Milner, 1957 ). His scientific fame derives from the dramatic demonstration of the critical role that the mesial temporal lobe structures play in learning and memory. Unlike Gage and Monsieur Tan, H.M.’s brain injury was iatrogenic, being an unanticipated adverse event associated with the surgical treatment of his epilepsy. Another important difference is that H.M.’s surgery injury occurred in what can broadly be considered to be the beginning of the modern era of neuroscience ( Shepherd, 2010 ). Thus, his cognitive abilities were subjected to formal characterization with extensive neuropsychological testing over five decades, providing a much richer characterization of his clinical semiology compared to Gage or Monsieur Tan.

H.M.’s amnesia framed how the neuroscience community would eventually conceptualize basic memory mechanisms, beginning with Brenda Milner's early demonstration that multiple memory systems exist such that declarative and procedural memory are readily dissociable ( Milner, 1965 ). Clinically, H.M.’s amnesia meaningfully influenced pre-operative epilepsy surgery protocols across the world. After several additional cases of post-surgical amnesia developed following unilateral temporal lobectomy, it was hypothesized that the functional reserve of the contralateral temporal lobe was insufficient to support the encoding of new memories following resection of the epileptogenic temporal lobe and mesial structures, and multiple methods for characterizing functional hippocampus status were developed ( Milner, 1975 ). What remains poorly reported in standard textbooks, however, is the historical context in which the decision to undergo epilepsy surgery was made, the blurring between experimental clinical techniques and informed consent, and the profound effects on H.M.’s quality of life.

To provide this broad historical context of H.M., Luke Dittrich has published PATIENT H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets ( Dittrich, 2016a ). This is far from a narrative review of H.M.’s contributions to understanding memory, and it is also not a typical biography. However, as the grandson of William Beecher Scoville, MD, the neurosurgeon who performed H.M.’s operation and a prolific practitioner of psychosurgery, Dittrich provides a unique “insider” perspective and captivating description of that era's medical zeitgeist that could not be easily achieved without such a personal relationship. In fact, much of the book does not directly involve H.M.’s life story, but rather, the management of significant psychiatric disease prior to the development of neuroleptics.

Scoville's neurosurgical practice primarily involved surgery for psychiatric indications rather than epilepsy surgery. The early development of psychosurgery's goals is exemplified with a quote from the 19th century physician Dr. Gottleib Burckhardt, who resected undifferentiated brain areas, that illustrates the depersonalization of patients with psychiatric disease: “Mrs. B. has changed from a dangerous and excited demented person to a quiet demented one” (p. 79). It was in late 1935, after listening to the report of operations on two chimpanzees, that Egas Moniz oversaw the first in his series of approximately 20 frontal leucotomies/lobotomies. This series significantly influenced Walter Freeman (neurologist) and James Watts (neurosurgeon) who initially worked together performing prefrontal lobotomies. The distinct approaches to frontal lobotomy developed by Scoville and Freeman also provide a striking contrast in how to best decrease the institutional burden of psychiatric disease. Although Scoville is described as an adventurer who liked expensive sports cars, he was a meticulous neurosurgeon with painstaking preparation before and during all surgical cases. Freeman's enthusiastic efforts to expand the use of frontal lobotomy was reflected by his technique in which an ice pick, inserted through the orbital sockets to a depth of approximately 3 inches, was moved back and forth for frontal disconnection before repeating the procedure on the opposite side. As practiced by Freeman, frontal lobotomy required approximately 15 min to complete, could be performed without a surgeon or an operating room, and multiple procedures could be easily performed in a single day. “Any reasonably competent psychiatrist (could be trained) to perform the ice-pick lobotomy in an afternoon” (p. 151). One can go elsewhere for the complete story of Freeman, his activities and their aftermath, which has been covered by others including the exquisite text by Elliot Valenstein (1986) .

Dittrich's concerns regarding psychiatric therapies during this era are not limited to psychosurgery. His grandmother, Scoville's wife, experienced a breakdown sometime after their marriage, suffered a brittle psychiatric course, and was institutionalized at the Hartford Institute of Living while her husband was director of neurosurgery there and was performing lobotomies at both the Institute of Living and Hartford Hospital. A variety of harsh non-surgical but unproven psychiatric treatments were used that included: (1) Continuous hydrotherapy in which patients were submerged in a tub with only their heads protruding through a small aperture. (2) Pyrotherapy in which patients were placed in a small copper coffin appearing device that, over a repeated treatment period of days, would elevate core temperatures to 105–106 °C. (3) Electric Shock Therapy. In response to patients’ fears about these therapies, treatment names were changed. “Since these treatments produce states of unconsciousness akin to normal slumber … we are adopting the names that are more truly descriptive of these treatments—INSULIN, METRAZOL, and ELECTRIC SLEEP” (p. 73). Karl Pribram, who was head of research at the Institute of Living at that time, claimed that Scoville had performed a frontal leucotomy on his wife, although Dittrich could not independently substantiate that assertion.

A recurring theme throughout PATIENT HM is the concept embodied by the Hippocratic Oath of “ primum non nocer ” (first, do no harm) as it contrasts with “ melius anceps remedium quam nullum” (it is better to do something than nothing). The tension between these approaches lies at the foundation of modern informed consent in which risks and benefits are carefully weighed as part of the decision-making processes prior to treatment initiation or when deciding to participate in clinical research. Informed consent discussion is not restricted to psychosurgery, shock therapies, or H.M. The rationale for informed consent includes the development of surgical treatment for vesicovaginal fistula by J. Marion Sims during the mid-19th century that was conducted on his slaves prior to application to white women, to the U.S. Public Health Service Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment in the 1930s, and the history of the Doctors Trial at Nuremberg after World War II resulting in the Nuremberg Code.

Scoville was a practitioner of psychosurgery rather than epilepsy surgery, and prior to H.M.’s surgery, Scoville had performed multiple bilateral temporal lobectomies for psychiatric indications. Although he describes H.M.’s surgery as an “experimental operation,” he also states that the procedure was considered due to H.M.’s seizure frequency and severity despite adequate medical therapy, and that surgery was “carried out with the understanding and approval of the patient and his family” ( Scoville & Milner, 1957 ).

By the time of H.M.’s surgery in 1953, the first reported series of temporal lobectomies for epilepsy had been published from the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) ( Penfield & Flanigin, 1950 ). Dittrich describes the important contributions of Wilder Penfield in epilepsy surgery development that ranged from identification of motor and sensory homunculi to how Penfield established a multidisciplinary and state of the art institute by including neurology, electrophysiology, and neuropsychology colleagues. It was in this context that Penfield hired Brenda Milner. A brief biography of Milner's early life is presented in which she designed psychological aptitude tests at Cambridge University during World War II before moving to Montreal and enrolling at McGill University as a graduate student of Donald Hebb.

Although H.M.’s surgery was not performed at the MNI, Milner's neuropsychological testing of epilepsy surgery patients at the MNI made her arguably the most appropriate individual to characterize H.M.’s memory impairment. The first formal scientific presentation of H.M.’s amnesia was published in 1957 by Scoville and Milner although his “very grave, recent memory loss” was described in 1953 at a meeting of the Harvey Cushing Society ( Scoville, 1954 ). However, the 1957 report also contains formal testing on additional temporal lobectomies performed on “seriously ill schizophrenic patients who had failed to respond to other forms of treatment” (p. 11), two of whom also developed significant amnesia following bitemporal resection. Orbital undercutting was extended to include the medial temporal lobes in the “hope that still greater psychiatric benefit might be obtained” (p. 11). The significant psychiatric disease of these patients decreased clinical awareness of memory change without Milner's formal testing given that “the psychotic patients were for the most part too disturbed before operation for finer testing of higher mental functions to be carried out” (p. 12). Thus, the extent of the memory impairment was unknown due to the significant overlaying psychiatric disease in the non-epilepsy patients on whom Dr. Scoville had performed bitemporal resection prior to H.M.

Scoville was sufficiently enthusiastic about the procedure to travel to teach other surgeons the technique. Interesting is mention of Scoville's trip to Manteno State Hospital, an extremely large psychiatric facility located south of Chicago in Manteno, Illinois. Here faculty from the University of Illinois were performing anterior temporal lobectomies that included hippocampal resection, something not undertaken by Percival Bailey in his series in Chicago. Dittrich mentions another severely amnestic case (D.C.) as an outcome of Scoville's surgery at Mantero, a physician from Chicago with a premorbid IQ of 122. He was evaluated postoperatively with the resulting amnesia, comparable to H.M., confirmed by Brenda Milner. This case was apparently very unsettling to Scoville.

It is impossible to review PATIENT HM without consideration of outside events that occurred after its publication. The New York Times Magazine published a book excerpt on August 3, 2016, beginning with interviews with H.M. illustrating the magnitude and severity of his memory impairment, briefly discussing post-mortem brain ownership disagreements between the University of California at San Diego and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, presenting background material on the tension between research groups surrounding manuscript preparation describing an previously unknown lesion in H.M.’s frontal lobe that was detected at autopsy, and discussing how H.M.’s court-appointed guardian was identified. The excerpt concludes with interview quotations from Dr. Suzanne Corkin, who was the principal investigator of H.M.’s amnesia since 1977 following the death of Hans-Lukas Teuber. Again, in an interesting personal twist, Corkin lived across the street from the Scovilles, and was one of Dittrich's mother's best friends during their childhood and adolescence.

After The Times’ excerpt appeared, MIT and other organizations quickly issued statements disputing Dittrich's assertions and conclusions ( Eichenbaum & Kensinger, 2016 ; MIT News Office, 2016 ). The main points of contention included: (1) allegation that research records were or would be destroyed or shredded, (2) allegation that the finding of an additional lesion in left orbitofrontal cortex was suppressed, and (3) allegation that there was something inappropriate in the selection of (the conservator) as Mr. Molaison's guardian. In addition, a letter signed by over 200 scientists supporting Corkin dated August 5, 2017 was sent to The Times ( DiCarlo et al., 2016 ) asserting that Dittrich's claims were untrue.

Part of the interest in the quick response by the scientific community presumably was that Corkin died on May 24, 2016 prior to the book's publication and was unable to respond to these concerns. While Dittrich (2016b) has directly addressed each of the MIT concerns, their response has nevertheless led many of our colleagues and students to assume that Dittrich's book was incendiary, and whose entire story should not be believed.

While the interested reader will examine both sides of the argument (see Vyse, 2016 ), there is no evidence to suggest that any of Dittrich's factual allegations are wrong. Thus, there are two important points to consider when deciding if this controversy should make otherwise interested individuals pass on reading the book. First, in response to the assertion that research records were shredded, some have suggested Corkin's use of “shredding” was either colloquial or referred to material no longer considered relevant. Corkin is explicit in her description of data shredding in the audio clip of her interview that Dittrich posted ( Dittrich, 2016b ). Certainly, the presence of many files in a storage room says nothing about whether any files had been shredded, particularly since there has never apparently been a comprehensive catalog of the material established. Non-published information can still inform our understanding of H.M.’s clinical course as demonstrated by Dittrich's observation that H.M. had a significant memory impairment prior to surgery, a fact that had not been formally published. Similarly, non-significant findings or “failed experiments” also demonstrate a broader representation of functions either affected or unchanged following surgery. As Dittrich notes, Corkin was a “meticulous investigator, keeping careful notes” (p. 270), and these notes have both scientific and historical value.

H.M.’s legal guardianship merits greater discussion compared to disagreements about scientific ownership and publication disputes, however, which unfortunately are sufficiently common that university committees exist to address such conflicts. Conservatorship, however, is central to this story because it affects the informed consent for H.M.’s research participation, as well as influencing the final disposition of H.M.’s brain after autopsy. Similar to research study reporting standards, the nature of informed consent has evolved over the course of H.M.’s research participation. Consequently, the absence of any conservator or formal consent process early in H.M.’s research participation reflected generally accepted standards at that time. In 1992, an independent conservator was sought for H.M. to mitigate against unintended conflict of interest by H.M.’s investigators, reflecting greater overall awareness of the importance of informed consent.

The eventual conservator was a son of a former landlady of H.M. Dittrich provides evidence that, in contrast to formal court filings, the conservator was not a relative, and that one of H.M.’s relatives was a first cousin sharing H.M.’s last name (Frank Molaison). We will never fully know how the various points are intertwined or even if H.M.’s relatives had been contacted and were not interested in assuming the role of conservator, and part of this controversy is that Corkin's perspective on Dittrich's claims cannot be obtained. Nevertheless, Dittrich's reporting these issues are neither irrelevant nor inappropriate. Careful consideration of H.M.‘s ability to provide informed consent, and how conservatorship is established in circumstances in which research subjects cannot fully consent, will increase awareness of ambiguities that will allow future researchers to confidently ensure full and appropriate consent is obtained prior to research participation.

Most of the book presents a non-controversial narrative, however, and that was not adequately captured by The Times’ excerpt. What we found to be particularly enjoyable in this book is that it provides new details on the contours of H.M.’s life. Prior to H.M.’s death, there were few personal details known to the scientific community, so it should not be surprising that much of this book's appeal is due to its biographical content reporting a variety of details about H.M.’s past. Upon hearing of H.M.’s death, the initial knowledge of his full name was both exciting but then also associated with some sense of guilt and dismay as if suddenly becoming privy to secret information that had been inadvertently revealed. We enjoyed reading about H.M.’s confusion of The Beatles with The Rolling Stones when examining a photograph, but then accurately spelling B-E-A-T-L-E-S rather than beetles, but there are many others throughout the book such as H.M.’s thick New England accent. When asked “Who, or what, is Sue Corkin,” H.M. replied “She was a … well, a senator.” The book also describes frequent angry outbursts including physical harm to himself, which contrasts with the typical H.M. description of his being agreeable and passive, and it is interesting to speculate whether this behavior might have been related to the orbitofrontal damage identified during autopsy. These pieces of personal information help humanize H.M. rather than simply being either a research subject or clinical syndrome. A particularly poignant comment by H.M. was his statement that “every day is alone in itself. Whatever enjoyment I've had, and whatever sorrow I've had” (p. 375).

Despite the controversies that arose after publication of The Times’ excerpt, or perhaps because of them, this book provides a unique glimpse into the blurring of experimental therapy and research during the mid-20th century, motivations for finding treatments for psychiatrically intractable patients prior to the development of neuroleptics, as well as professional interactions and conflicts that may arise in collaborative research settings. Unlike Gage and Monsieur Tan, the depth of clinical research and the modern era in which he lived not only makes H.M. one of the most influential case studies in clinical neuroscience, but also provides one of the most compelling individual stories about how unanticipated surgical effects robbed H.M. of the capacity to form meaningful and lasting relationships with others due to the inability to form new memories. Though clearly not a textbook, and undeniably chatty at times, this is a volume that neuropsychologists at all levels of training and experience, and particularly those with interests in the history of medicine, will enjoy reading and remembering for a long time.

PATIENT H.M: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets received the 2017 The PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award. We thank Kimford J. Meador for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this review.

Code , C. , Wallesch , C. W. , Joanette , Y. , & Lecours , A. R. ( 1996 ). Classic cases in neuropsychology . New York : Psychology Press .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

DiCarlo , J. J. , Kanwisher , N. , Gabrieli , J. D. E. , Adcock , R. A. , Addis , D. R. , Aggleton , J. P. , et al. . ( 2016 ). Letter to the Editor of the New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://bcs.mit.edu/news-events/news/letter-editor-new-york-times-magazine .

Dittrich , L. ( 2016 b). Questions & Answers about “Patient H.M.” Retrieved frrom https://medium.com/@lukedittrich/questions-answers-about-patient-h-m-ae4ddd33ed9c#.apelhqx85.

Dittrich , L. ( 2016 a). PATIENT H.M.: A story of memory, madness, and family secrets . New York : Random House .

Eichenbaum , H. , & Kensinger , E. ( 2016 ). In defense of Suzanne Corkin. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/in-defense-of-suzanne-corkin#.WKIOVE3rvL8 .

Macmillan , M. ( 2000 ). Restoring Phineas Gage: A 150th retrospective . Journal of the History of Neurosciences , 9 (1), 46 – 66 .

Macmillan , M. , & Lena , M. L. ( 2010 ). Rehabilitating Phineas Gage . Neuropsychological Rehabilitation , 20 (5), 641 – 658 .

Milner , B. ( 1965 ). Visually guided maze learning in man: Effects of bilateral hippocampal, bilateral frontal, and unilateral cerebral lesions . Neuropsychologia , 3 , 317 – 338 .

Milner , B. ( 1975 ). Psychological aspects of focal epilepsy and its neurosurgical management . Advances in Neurology , 8 , 299 – 321 .

MIT News Office ( 2016 ). Faculty at MIT and beyond respond forcefully to an article critical of Suzanne Corkin. Retrieved from http://news.mit.edu/2016/faculty-defend-suzanne-corkin-0809 .

Penfield , W. , & Flanigin , H. ( 1950 ). Surgical therapy of temporal lobe seizures . AMA Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry , 64 (4), 491 – 500 .

Scoville , W. B. ( 1954 ). The limbic lobe in man . Journal of Neurosurgery , 11 , 64 – 66 .

Scoville , W. B. , & Milner , B. ( 1957 ). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions . Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry , 20 , 11 – 21 .

Shepherd , G. M. ( 2010 ). Creating modern neuroscience: The revolutionary 1950s . New York : Oxford University Press .

Sondhaus , E. , & Finger , S. ( 1988 ). Aphasia and the CNS from Imhotep to Broca . Neuropsychology , 2 (2), 87 – 119 .

Valenstein , E. ( 1986 ). Great and desperate cures: The rise and decline of psychosurgery and other radical treatments for mental Illness . New York : Basic Books .

Vyse , S. ( 2016 ). Consensus: Could two hundred scientists be wrong? Retrieved from http://www.csicop.org/specialarticles/show/consensus_could_two_hundred_scientists_be_wrong .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-5843

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

HM, the Man with No Memory

Henry molaison (hm) taught us about memory by losing his..

Posted January 16, 2012 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Henry Molaison, known by thousands of psychology students as "HM," lost his memory on an operating table in a hospital in Hartford in August 1953. He was 27 years old and had suffered from epileptic seizures for many years.

William Beecher Scoville, a Hartford neurosurgeon , stood above an awake Henry and skilfully suctioned out the seahorse-shaped brain structure called the hippocampus that lay within each temporal lobe. Henry would have been drowsy and probably didn't notice his memory vanishing as the operation proceeded.

The operation was successful in that it significantly reduced Henry's seizures, but it left him with a dense memory loss. When Scoville realized his patient had become amnesic, he referred him to the eminent neurosurgeon Dr. Wilder Penfield and neuropsychologist Dr. Brenda Milner of Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI), who assessed him in detail. Up until then, it had not been known that the hippocampus was essential for making memories, and that if we lose both of them we will suffer a global amnesia. Once this was realized, the findings were widely publicized so that this operation to remove both hippocampi would never be done again.

Penfield and Milner had already been conducting memory experiments on other patients and they quickly realized that Henry's dense amnesia, his intact intelligence , and the precise neurosurgical lesions made him the perfect experimental subject. For 55 years, Henry participated in numerous experiments, primarily at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where Professor Suzanne Corkin and her team of neuropsychologists assessed him.

Access to Henry was carefully restricted to less than 100 researchers (I was honored to be one of them), but the MNI and MIT studies on HM taught us much of what we know about memory. Of course, many other patients with memory impairments have since been studied, including a small number with amnesias almost as dense as Henry's, but it is to him we owe the greatest debt. His name (or initials!) has been mentioned in almost 12,000 journal articles, making him the most studied case in medical or psychological history. Henry died on December 2, 2008, at the age of 82. Until then, he was known to the world only as "HM," but on his death his name was revealed. A man with no memory is vulnerable, and his initials had been used while he lived in order to protect his identity .

Henry's memory loss was far from simple. Not only could he make no new conscious memories after his operation, he also suffered a retrograde memory loss (a loss of memories prior to brain damage) for an 11-year period before his surgery. It is not clear why this is so, although it is thought this is not because of his loss of the hippocampi on both sides of his brain. More likely it is a combination of his being on large doses of antiepileptic drugs and his frequent seizures prior to his surgery. His global amnesia for new material was the result of the loss of both hippocampi, and meant that he could not learn new words, songs or faces after his surgery, forgot who he was talking to as soon as he turned away, didn't know how old he was or if his parents were alive or dead, and never again clearly remembered an event, such as his birthday party, or who the current president of the United States was.

In contrast, he did retain the ability to learn some new motor skills, such as becoming faster at drawing a path through a picture of a maze, or learning to use a walking frame when he sprained his ankle, but this learning was at a subconscious level. He had no conscious memory that he had ever seen or done the maze test before, or used the walking frame previously.

We measure time by our memories, and thus for Henry, it was as if time stopped when he was 16 years old, 11 years before his surgery. Because his intelligence in other non-memory areas remained normal, he was an excellent experimental participant. He was also a very happy and friendly person and always a delight to be with and to assess. He never seemed to get tired of doing what most people would think of as tedious memory tests, because they were always new to him! When he was at MIT, between test sessions he would often sit doing crossword puzzles, and he could do the same ones again and again if the words were erased, as to him it was new each time.

Henry gave science the ultimate gift: his memory. Thousands of people who have suffered brain damage, whether through accident, disease or a genetic quirk, have given similar gifts to science by agreeing to participate in psychological, neuropsychological, psychiatric and medical studies and experiments, and in some cases by gifting their brains to science after their deaths. Our knowledge of brain disease and how the normal mind works would be greatly diminished if it were not for the generosity of these people and their families (who are frequently also involved in interviews, as well as transporting the "patient" back and forth to the psychology laboratory). After Henry's death, his brain was dissected into 2,000 slices and digitized as a three-dimensional brain map that could be searched by zooming in from the whole brain to individual neurons. Thus, his tragically unique brain has been preserved for posterity.

Jenni Ogden, Ph.D. , clinical neuropsychologist and author of Trouble in Mind, taught at the University of Auckland.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Mrs. Eplin's IB Psychology Class Blog

HM Milner (1966)

Maureen Quartuccio

Background/Aim: Henry Gustav Molaison is most widely known as “Patient HM”. He started getting epileptic seizures from a young age when he sustained a head injury from a bicycle accident. At 16 his seizures got increasingly severe and by 27 they were so bad and affected his daily life so immensely that doctors decided something had to be done. Henry then saw a neurosurgeon, Dr. William Beecher Scoville, who suggested that the part of the brain that was causing the seizures should be removed. This was very dangerous and was still very experimental at the time but Henry decided to go through with it. A bilateral medial temporal lobe resection was conducted and included the removal of parts of the hippocampus and amygdala. From the surgery, Henry acquired severe anterograde amnesia which meant that he couldn’t make any new memories.

Aim: To see the causes of anterograde amnesia

Procedure: Milner conducted many different studies to observe HM. These studies included Psychometric testing (IQ tests), Direct observation of his behavior, Cognitive testing, and an MRI to assess the longlasting damage to the patient’s brain.

Results: HM had some sort of working memory because he was able to carry out a conversation with people. His Procedural memory was intact as well because he still remembered his basic motor skills. He did lose his ability to develop new episodic and semantic knowledge. The MRI revealed that the hippocampus had the most damage and that was the reason for the disconnect between short-term and long-term memory.

Evaluation: This study was huge for many reasons but is also invalid because there is no way to ever replicate it exactly. The study revealed that there were different places for the storage of memory (short-term and long-term). It also revealed where these memories are located. This study was very important to show what would happen when certain parts of the brain were damaged. Overall this case was monumental towards expanding our knowledge on the biological factors of our memories.

Works Cited: Myers, Jim. “Brain Case Study: HM.” Bigpictureeducation . https://bigpictureeducation.com/brain-case-study-patient-hm

Share this:

Published by IB Psychology 2018-2019

View all posts by IB Psychology 2018-2019

6 thoughts on “ HM Milner (1966) ”

It increased the validity of the experiment by collecting data in so many ways. I totally agree that it’s unethical and unrepeatable. – Miranda

This gives a great insight into how the hippo campus effects memory. Unfortunately because this is a case study it has low predictability because there is not enough evidence because it was just one person. -Jordan Marley-Weaver

I enjoyed this study, it talked a lot about knowing how to store your memories. But it sucks to find out it can’t be repeated. Very interesting study.-Micah Goldman

It’s interesting knowing that memory is stored all over the brain and that damage to a certain area can effect it. But because this is a case study there isn’t enough evidence to fully support it. -jennifer

I can not tell if I think this is ethical or not not the study itself but the procedure. While I guess it was a different time with little information I just feel like the surgery was experimental to begin with.

-Nadia Schweiger

John Quartuccio I thought This was a very interesting study, But I agree with Nadia’s concerns over whether or not the procedure was entirely ethical or not.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Study Notes

Corkin (1997)

Last updated 22 Mar 2021

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Effect of hippocampal damage on memory.

Background information: Corkin had known H.M. since 1962, during which time he had never recognised her from one visit to another. Corkin and her colleagues used MRI scanning in 1992 and 1993 (written up in their 1997 article) to determine if Scoville’s estimated lesioning of H.M.’s temporal medial lobe area had been as he stated (see the diagram under Scoville and Milner), and whether this could be sufficient to have resulted in the drastic memory loss suffered by H.M.

Aim: To investigate the extent of the hippocampal and medial temporal lobe damage to H.M.’s brain and to determine whether this could be sufficient to have resulted in the drastic memory loss suffered by H.M.

Method: One MRI scan was conducted on H.M. in 1992 and one in 1993. Before the 1992 scan, H.M. completed an IQ test and a memory test. The IQ test showed that he had normal intelligence, but the memory test showed his memory quotient (MQ) was 37 points lower than his IQ and showed he had severe amnesia.

Results: Both scans showed that the lesioning (also called ablation or cutting) of H.M.’s brain was 3cm less than Scoville had estimated. It therefore did not extend as far into the posterior hippocampal region as he thought, although there was surrounding damage, as stated, to the uncus and the amygdala. Approximately 50% of the posterior hippocampus on each side remained, but this had shrunk considerably on the right side. Corkin et al. believe this could be due to both the removal of the rest of the hippocampus, and also to the drugs and continuing (though much reduced) epileptic seizures.

Evaluation:

There is not much to criticise with this study. Corkin had interviewed H.M. extensively over the years, and took care to ensure that the MRI caused no trouble to H.M., who had three non-magnetic clips inserted in his brain by Scoville in 1953, and which had they been magnetic would have meant an MRI was not advised. However, ethically there are some questions. It was Brenda Milner, the psychologist associated long-term with H.M. who gave the permission for Corkin to scan H.M.’s brain. It is not clear if she was the appointed responsible adult legally able to do this. H.M., even if he gave permission himself, would not have remembered it, so there are issues with informed consent and right to withdraw, although anonymity was maintained until after his death.

For More Study Notes…

To keep up-to-date with the tutor2u Psychology team, follow us on Twitter @tutor2uPsych , Facebook AQA / OCR / Edexcel / Student or subscribe to the Psychology Daily Digest and get new content delivered to your inbox!

- Hippocampus

You might also like

Scoville and milner (1957), fink et al. (1996), maguire et al. (2000), ib psychology (bloa): animal research may inform our understanding of human behaviour, ib psychology (bloa): cognitions, emotions & behaviours are products of the anatomy and physiology of our nervous and endocrine system, our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Legacy of Patient H.M. for Neuroscience

Larry r. squire.

1 Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, San Diego, CA 92161, USA

2 Departments of Psychiatry, Neurosciences, and Psychology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

H.M. is probably the best known single patient in the history of neuroscience. His severe memory impairment, which resulted from experimental neurosurgery to control seizures, was the subject of study for five decades until his death in December 2008. Work with H.M. established fundamental principles about how memory functions are organized in the brain.