Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 8

- Exploring the factors that affect new graduates’ transition from students to health professionals: a systematic integrative review protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8970-0059 Eric Nkansah Opoku 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0003-6006 Lana Van Niekerk 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0684-5373 Lee-Ann Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi 2

- 1 Department of Occupational Therapy , College of Health Sciences; University of Ghana , Accra , Greater Accra Region , Ghana

- 2 Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences , Stellenbosch University , Cape Town , Western Cape , South Africa

- Correspondence to Eric Nkansah Opoku; Enopoku{at}ug.edu.gh

Introduction To become a competent health professional, the nature of new graduates’ transition plays a fundamental role. The systematic integrative review will aim to identify the existing literature pertaining to the barriers during transition, the facilitators and the evidence-based coping strategies that assist new graduate health professionals to successfully transition from students to health professionals.

Methods and analysis The integrative review will be conducted using Whittemore and Knafl’s integrative review methodology. Boolean search terms have been developed in consultation with an experienced librarian, using Medical Subject Heading terms on Medline. The following electronic databases have been chosen to ensure that all relevant literature are captured for this review: PubMed, EBSCOhost (including Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Academic Search Premier, Health Science: Nursing and Academic Edition), Scopus and Web of Science. A follow-up on the reference list of selected articles will be done to ensure that all relevant literature is included. The Covidence platform will be used to facilitate the process.

Ethics and dissemination Ethical approval is not required for this integrative review since the existing literature will be synthesised. The integrative review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal once all the steps have been completed. The findings will also be presented at international and national conferences to ensure maximum dissemination.

- new graduate

- clinical practice

- professional competence

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033734

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The search strings for this integrative review were developed in consultation with an experienced librarian.

The search is comprehensive and will include electronic databases (PubMed, EBSCOhost (including CINAHL, Medline, Health Science: Nursing and Academic Edition), Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane. Hand searching and follow-up of reference lists of eligible publications will be done to ensure that all relevant literature are included in the study.

The authors will conduct a blind review to ensure rigorous and consistent application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Qualitative data analysis software, namely, Weft QDA, will be used to analyse the literature to maximise the findings in terms of both implications for clinical practice and research.

The findings from the integrative review might not be exhaustive of all available literature on factors that affect new graduates’ transition into practice because it will be limited by the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Introduction

The transition from undergraduate student to health professional is recognised as a period of great stress for the new graduate. On commencing clinical practice, new graduates enter a relatively new and often challenging environment. They have to make substantial adjustments from being students whose procedures and activities were supervised in a controlled environment to practising independently as qualified health professionals. 1 This change in status from a student to a health professional is marked by changes in both roles and expectations, which requires that the theoretical knowledge acquired in school be transferred to the practice context. 2 Furthermore, new graduates are expected to plan and implement relevant client treatment programmes. This transition has been described as a period of stress, requiring effective management of conflicting values and role uncertainty. 3 In a phenomenological study conducted by Brennan et al 4 in the UK, junior doctors who participated in the study described their transition from medical students to junior doctors as extremely stressful; both physically and emotionally. The study highlighted that participants were overwhelmed with feelings of anxiety due to uncertainty about their clinical decisions including diagnosis and treatment. 4 Inadequate preparation for this transition may cause the new health professional’s therapy to be ineffective. 5

The transition to practice for new graduates was described as gradual and complex, involving a complete transformation particularly in the first year after graduation. A thorough literature review by McCombie and Antanavage 6 established that new graduates experience low personal and professional confidence, particularly at the initial stage of the transition. A phenomenological study by Seah et al 7 reported that all participants experienced shock on starting work due to the confusing nature of the hospital facility operations, administrative requirements, expectations of other health professionals and professional title.

To become a competent health professional, the nature of a new graduate’s transition plays a fundamental role. Several strategies have been identified in the literature to alleviate the challenges inherent in transition into practice. Supervision has been consistently emphasised as significant during transition. In occupational therapy, supervision has been shown to contribute to new graduates’ ability to relate their acquired knowledge to practice. 8 Hummel and Koelmeyer 9 conducted a quantitative cross-sectional study among occupational therapists (n=74) in Australia to investigate their perceptions, regarding their first year of practice. They found that formal supervision by an experienced health professional, who is capable of providing essential feedback and support, was considered a vital component of a successful transition 9 and fundamental to the new graduate’s perceived success at work. 10 Tryssenaar and Perkins 2 also found supervision to be a vital component to promoting competency. Also in the nursing profession, consistent emphasis has been placed on supervision as an effective strategy to help new graduate nurses to relate the knowledge acquired in the classroom to practice. 11–13 Thus, effective supervision equips new practitioners with competencies that are relevant to their professional career. This impacts on their practice by increasing clinical skills, self-confidence and perception of competence, consequently improving quality of service to clients. 12

The literature revealed several support and coping strategies aimed at easing the challenges of transition into practice. Moores and Fitzgerald 8 found that work colleagues play an important role in ensuring successful transition as they provide advice and information to new graduates. Support from experienced colleagues and other new graduate peers was reported to be highly valued. 8 Halfer and Graf 14 confirmed the importance of supervision and emphasised the value of positive relationships with other professionals and coworkers. A thorough literature review by Moores and Fitzgerald 8 revealed that interactions with peers in the form of group learning, networking and structured discussions on topics relevant to clinical practice supported the transition into practice. In an Australian cross-sectional study by Hummell and Koelmeyer, 9 the novice occupational therapists (n=74) reported that informal support from other new graduates within and beyond the workplace eased their role transition. Regan et al 15 highlighted that formal orientation and mentorship facilitated new health professionals’ transition into practice.

Continued professional development opportunities have also been reported as important in the transition of new graduates into practice. Seah et al 7 reported a positive link between novice professionals’ engagement in continued professional development and increased professional confidence in the clinical environment.

An integrative review will be beneficial in examining the availability and the extent of literature, examining varied perspectives on factors that affect transition into practice. It will aim to identify existing literature pertaining to the barriers and facilitators experienced during transition from being a new graduate to becoming a health professional and the evidence-based coping strategies that assist this transition. The integrative review will inform a larger study to be conducted in Ghana on the factors that impact the transition of new health graduates into independent practice. Health professions’ education programmes offer different types of graded practical exposure, designed to bridge learning between classroom teaching and clinical practice. For some health professions, clinical practice exposure is embedded in the curricula while others complete the pre-clinical component of their curriculum before entering a distinct internship. These differ in terms of level of expectation, duration and level of independence required. For example, occupational therapists complete 1000 hours of clinical practice experience as part of their education and training. 16 For the purpose of the integrative review, the authors will consider all practical and clinical exposures required as part of curricula leading up to qualification as entry-level health practitioners to be a component of learning and thus completed in capacity as student health professional. We are interested in the transition health professionals make having completed their education and training into independent practice.

Aims and objectives

This integrative review aims to identify research conducted in the last two decades (1999–2019) on the factors that affect newly graduated health professionals’ transition in becoming health professionals. The specific objectives are:

To determine the challenges associated with new health graduates’ transition into practice.

To identify the factors that facilitate transition of new health graduates into practice.

To describe the coping strategies employed by new graduates to ensure successful transition into practice.

Methods and analysis

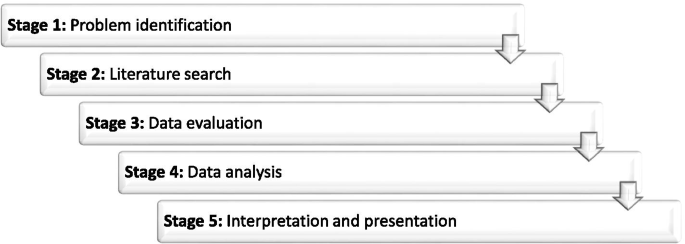

The integrative review will be conducted using Whittemore and Knafl’s 17 integrative review methodology as a guide. This methodological framework comprises five stages: (1) problem identification, (2) literature search, (3) data evaluation, (4) data analysis and (5) presentation.

Problem identification

The nature of a health professional’s transition into independent practice is critical to development of clinical competence. There is wealth of literature on the transition of new graduates into practice for health professionals from diverse backgrounds. This integrative review will explore the factors that affect newly graduated health professionals’ transition into practice comprehensively. To capture the scope and the diversity of available literature, 17 three broad research questions were developed to guide this review. These are:

What types of challenges do new health graduates face during transition into practice?

What factors facilitate the transition of new health graduates into practice?

What coping strategies do new health graduates employ to ensure successful transition into practice?

Literature search

A search will be done to identify literature from electronic databases. Hand searches will be done to retrieve literature that were not found in the databases. Additionally, a follow-up of the reference lists of the included articles will be done to ensure that all relevant literature are included in the review.

Taking the research question and purpose into consideration, the following electronic databases have been chosen for the search for relevant literature for this review: PubMed, EBSCOhost (including CINAHL, Medline, Academic Search Premier, Health Science: Nursing and Academic Edition), Scopus, Cochrane and Web of Science. These databases and search terms were selected in consultation with an experienced subject librarian. The search terms include Medical Subject Heading terms on Medline (see table 1 ).

- View inline

Search strings derived from Medical Subject Heading

An initial search was done on 3 April 2019 to check the suitability of the search string. These results are presented in table 2 . Limiters applied were Published (January 1999 to April 2019), SmartText searching and Language (English only).

Initial database search results

The search will be done using the abstract/title field and will include articles published within the last two decades. Hand searching of the reference lists of included articles will be done to ensure that all articles relevant to the study are included.

Inclusion criteria

The review will include only research articles published in English within the last two decades (1999–2019). There will be no restriction by country. Preliminary inclusion and exclusion criteria have been developed as a guide in the selection of studies for this review. These are presented in table 3 .

Provisional selection criteria

Only primary studies on transition of new graduate health professionals into practice, when education has been completed, will be included. This is the period between starting work as a supervised novice to being a competent health professional who has completed the transition. Figure 1 illustrates the period of transition into practice.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Period of transition into practice illustration.

Data evaluation

All studies that meet the inclusion criteria will be included in this review. Titles and abstracts of all retrieved literature will be uploaded onto Covidence, which will be used to manage the project. The Covidence platform will remove duplicates automatically before the review process will begin. Quality assessment will consider issues such as the clarity of the study aim, the participants and the relevance to answer the research questions of the proposed review. Three independent reviewers will screen all studies against the inclusion criteria to determine their eligibility to be included in this integrative review. Following the title and abstract screening, the full texts of the included publications will be uploaded for full-text screening against the same predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria by the same three reviewers. Full-text publications which meet the inclusion criteria will be selected for data extraction. Conflicts will be resolved by consultation among the three reviewers until a consensus is reached. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols diagram will be used to represent the number of articles that were identified in each of the steps of the review process for visual representation.

Once consensus has been reached on eligibility, relevant data will be extracted. The primary reviewer will read each of the selected full-text publications. A data charting form, adapted from Uys et al 18 will be used in the extraction of the data that will answer the research questions and organise existing literature. To test the feasibility, the form will be tested by the lead reviewer on a random sample of the publications included in the review. Key information obtained from the full articles reviewed will be charted. For each of the included studies, the researcher will extract the following data:

Study characteristics: author names, publishing journal, year of study published, country of study and the population of the study.

Study aims, objectives and/or research questions, the study design.

The findings, with particular emphasis on the barriers, the facilitators and coping strategies of transition into practice.

Data analysis

An inductive and thematic approach to data analysis will be used. Weft QDA, a qualitative data analysis system, will be used to analyse and categorise the literature into theme areas. The analysis will focus on extracting themes from the following areas:

The challenges associated with transition into practice for new health graduates.

The facilitators of transition into practice for new health graduates.

The coping strategies employed by new graduates to ensure successful transition into practice.

Presentation

Once the data evaluation and extraction process have been completed, the study findings will be presented in the form of descriptions and narrations. Given the likely heterogeneity of studies that will be included in this study, narrative summaries of the characteristics of each study will be presented. The findings will be synthesised and written up into a coherent article.

Patient and public involvement

The proposed integrative review will not have any patient or public involvement.

The researchers anticipate that the findings of this integrative review will contribute to advancing knowledge of the barriers, the facilitators and the coping strategies of transition into practice. These can enable clinical supervisors, academics and policymakers to better understand challenges faced and strategies that can assist novice health professionals. Students and new graduates in health sciences might be informed of the obstacles that they are likely to encounter when they commence practice after graduation. They might also be informed of the facilitators and coping strategies that have been found to assist transition into practice. Findings from this study might also inform curriculum development to better prepare students for transition into practice.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required for this integrative review since existing literature will be synthesised. Once all the steps have been completed, the integrative review will be published in health professional education or practice journal. The findings will also be presented at international, national and local conferences.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Mrs Ingrid Van der Westhulzen (subject librarian) at the University of Stellenbosch for contributing towards developing the initial search strings for the integrative review.

- Tryssenaar J ,

- Brennan N ,

- Corrigan O ,

- Allard J , et al

- McCombie RP ,

- Antanavage ME

- Mackenzie L ,

- Fitzgerald C

- Hummell J ,

- Koelmeyer L

- Kennedy-Jones M

- De Bellis A ,

- Longson D ,

- Glover P , et al

- Al Awaisi H ,

- Pryjmachuk S

- Laschinger HK , et al

- Minimum Standards for the Education of Occupational Therapists

- Whittemore R ,

- Buchanan H ,

- Van Niekerk L

Twitter @OpokuNkansah

Contributors All three authors of this article contributed to the conceptualisation, drafting, development and editing of this integrative review protocol. ENO drafted the initial protocol manuscript as part of his master’s degree, LVN and L-AJ-NK guided the development of the protocol and made substantial conceptual and editing contributions and have approved this manuscript. All researchers contributed to all drafts of the manuscript and will be involved in screening and extracting the data once the integrative review commences. The researchers are all committed to being accountable for all aspects of this protocol.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 02 November 2021

Exploring the factors that affect the transition from student to health professional: an Integrative review

- Eric Nkansah Opoku ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8970-0059 1 , 3 nAff2 ,

- Lee-Ann Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0684-5373 1 &

- Lana Van Niekerk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0003-6006 1

BMC Medical Education volume 21 , Article number: 558 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

9 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

The nature of a new health professional’s transition from student to health professional is a significant determinant of the ease or difficulty of the journey to professional competence. The integrative review will explore the extent of literature on the factors that impact the transition of new health professionals into practice, identify possible gaps and synthesise findings which will inform further research. The aim was to identify research conducted in the last two decades on the barriers, facilitators and coping strategies employed by new health professionals during their transition into practice.

Whittemore and Knafl’s methodological framework for conducting integrative reviews was used to guide this review. Sources between 1999 and 2019 were gathered using EBSCOhost (including CINAHL, Medline, Academic Search Premier, Health Science: Nursing and Academic Edition), PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane and Web of Science, as well as hand searching and follow-up of bibliographies followed. The Covidence platform was used to manage the project. All studies were screened against a predetermined selection criteria. Relevant data was extracted from included sources and analysed using thematic analysis approach.

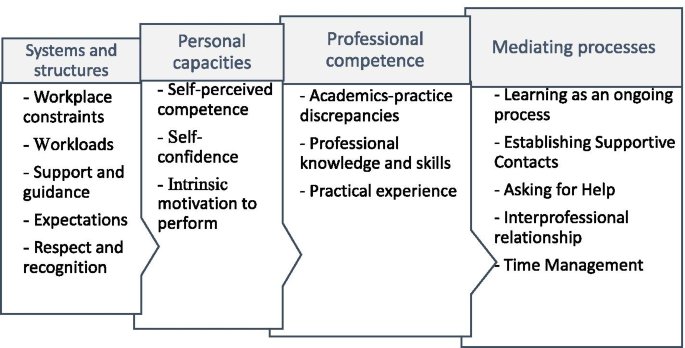

Of the 562 studies identified, relevant data was extracted from 24 studies that met the inclusion criteria, and analysed to form this review. Thematic analysis approach was used to categorise the findings into theme areas. Four overarching themes emerged namely: systems and structures, personal capacities, professional competence and mediating processes. Each theme revealed the barriers, facilitators and coping strategies of transition into practice among new health graduates.

The transition into practice for new health practitioners has been described as complex and a period of great stress. Increasing clinical and practical experiences during education are required to support new health professionals in the process of closing the gap between learning and practice. Continued professional development activities should be readily available and attendance of these encouraged.

Peer Review reports

The transition into practice for new practitioners has been described as complex and a period of great stress [ 1 , 2 ]. The academic environment and the practice environment have been described as different worlds as knowledge acquired in the classroom was deemed practically untransferable to the real world [ 3 , 4 ]. Due to the gap between academic and practice contexts, evidence suggests that new health professionals might be overwhelmed with feelings of inadequacy [ 5 ], unpreparedness [ 6 ] and doubtfulness related to their competence [ 4 , 7 ]. Evidence also suggests that, the reality of practice is experienced as a shock by new health practitioners [ 6 , 7 ]; feelings that might negatively affect- the personal and professional confidence of new health professionals [ 8 ]. Other challenges experienced during the transition included role confusion [ 9 ], overwhelming workloads [ 3 ], sophisticated workplace protocols [ 10 ] and lack of respect and recognition [ 11 ].

The nature of a new health professional’s transition from student to health professional has been shown to be a significant determinant of the ease or difficulty of his/her journey to professional competence [ 2 , 12 ]. Several strategies were found to alleviate the challenges that characterise the transition from student to health professional. Consistent emphasis is placed on supervision to help new health professionals relate the knowledge acquired in the classroom to practice [ 4 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Effective supervision equips new health professionals with skills needed to function in their respective areas of practice [ 13 ]. Moores and Fitzgerald [ 12 ] established that meaningful interactions with other new health professionals in the form of study groups, peer support meetings and social interaction sessions contribute significantly to successful transitions to practice [ 14 ]. Other support strategies emphasised in the literature include adequate orientation for new health professionals [ 11 , 16 ], support from more experienced senior colleagues [ 15 ], preceptorship programmes [ 17 ] and other health professionals [ 18 ]. New health professionals have also been advised to utilise continuing education opportunities. Evidence suggests that continued professional development avenues positively impact on new health professionals’ self-confidence and professional identity [ 7 ].

This integrative review aimed to identify research conducted in the last two decades (1999-2019) on the barriers and facilitators associated with new health professionals’ transition into practice and the coping strategies employed to ensure successful transition into practice

The integrative review commenced with publication of the protocol so as to obtain peer input [ 19 ]. Whittemore and Knafl’s [ 20 ] methodological framework for conducting integrative reviews guided this review (See Fig. 1 ); the process will now be discussed in detail.

Stages of Whittemore and Knafl’s Methodological Framework [ 20 ]

Problem Identification (Preparing guiding question)

The overarching question that guided this review was ‘what factors affect the transition of new health professionals from students to health professionals?’ To capture the scope and the diversity of available literature, three specific research questions were developed to answer the question.

What challenges do new health professionals face during transition into practice?

What factors facilitate the transition of new health professionals into practice?

What coping strategies do new health professionals employ to ensure successful transition into practice?

Literature search

A search was done to identify literature from five electronic databases namely PubMed, EBSCOhost (including CINAHL, Medline, Health Science: Nursing and Academic edition), Scopus, Cochrane and Web of Science. The first search was done April 3, 2019. The search strategy included the keywords New clinician OR Novice professional OR Health student AND Transition* AND Clinical practice AND Clinical competence OR Professional Competence. The search strategy used was developed in consultation with an experienced subject librarian. Limiters applied were published date (January 1999 to April 2019), SmartText searching and Language (English only). Hand searches and follow up of the reference lists of the included articles was done to retrieve literature that were not found in the databases.

Data evaluation

Titles and abstracts of all retrieved sources were uploaded onto the Covidence Platform, which was used to manage the project. The Covidence platform automatically removed duplicates before the review process began. Quality assessment was undertaken to ensure the clarity of study aim, the participants and the relevance of the of the study to answer the research question. All studies were assessed for eligibility by three independent reviewers according to the criteria contained in Table 1 .

Following the title and abstract screening, full texts of the included studies were uploaded for full text screening against the same predetermined selection criteria. Conflicts were resolved through consultation among the three reviewers until consensus was reached. Once consensus was reached on the eligibility of sources, data was extracted from full text publications using a data charting form adapted from Uys et al [ 21 ]. For each of the included studies, the researcher extracted the study characteristics (author names, publishing journal, year study was published, country of study and the population of the study), study aims, objectives and/or research questions, the study design and the findings (with particular emphasis on the barriers, the facilitators and coping strategies of transition into practice).

Data analysis and presentation

Once the data extraction process was completed, findings were analysed and categorised into themes areas using a thematic analysis approach [ 22 ]; this involved summary and categorization of data into codes, sub-themes and main themes. The analysis focused on extracting data that met the objectives of this review. The first author did the analysis, which was then reviewed and refined with the assistance of the second and third authors. Once the data evaluation and analysis processes were completed, the review findings were presented in the form of descriptions and narrations.

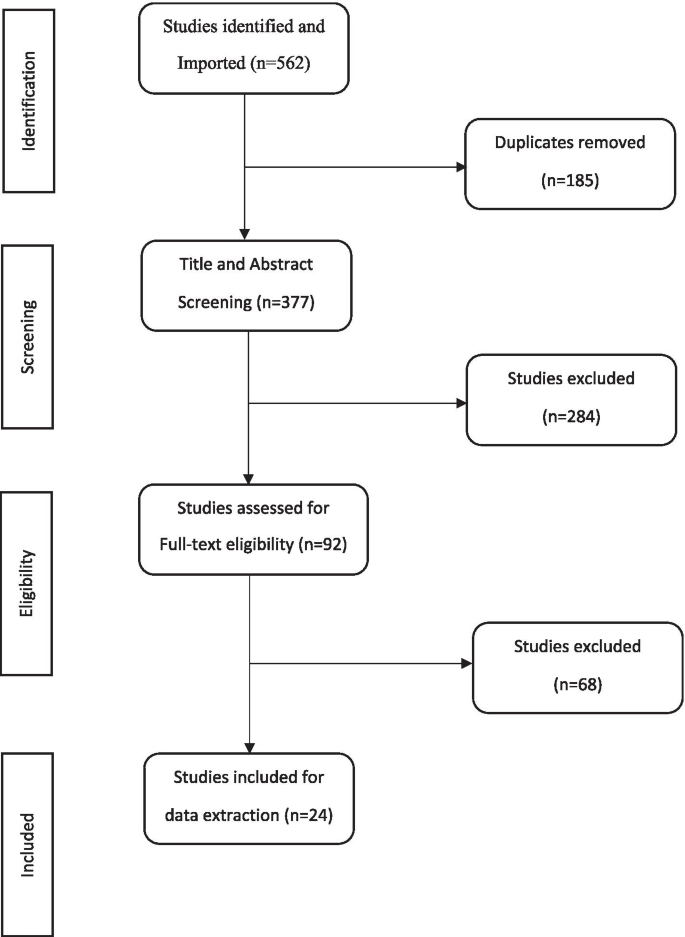

Study selection

The primary search strategy identified 562 studies from which 185 duplicates were removed. The title and abstract of 377 sources were screened and 284 were excluded. The full texts of the included sources were uploaded onto the Covidence platform for full text screening against the same predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Overall, 92 studies were assessed for full-text eligibility. A final total of 24 studies met the inclusion criteria and relevant data was extracted and analysed to form this review (See Fig. 2 : PRISMA flow chart of study selection)

PRISMA flow chart of study selection

Study characteristics

Most sources originated in Australia ( n = 8; 33.3%), followed by Canada ( n = 5; 20.8%), the USA ( n = 3; 12.5%), the UK ( n = 2; 8.3%) and Norway, Turkey, Oman, Jordan, Philippines and Ireland ( n =1 for each country; 4.2%). Twenty sources used qualitative methodologies, 3 used quantitative methodologies and one study used mixed methods. Thirteen sources pertained the profession of nursing (54.2%), seven were on occupational therapy (29.2%), two about medicine/medical doctors (8.3%) and one each on physiotherapy and midwifery (4.2%). Most studies pertaining physiotherapists, midwives and doctors, focused on the transition from student to forms of practice that precede independent practice, for example clinical placements, internships and residencies. These did not form part of this review thus accounting for the low number of sources for these professions. Table 2 presents a summary of the sources that were included in the review including characteristics such as first author, year of publication, country of origin, study aims, sample size, profession of participants, the methodology used and the publishing journal.

Data extraction was done with the three research questions in mind. Multiple factors which affected the multifaceted experiences of new health professionals during their transitions, either positively or negatively, were identified. These factors pertained experiences of new health professionals with self, clients, other health professionals, workplace protocols and the healthcare delivery system as a whole. Once data were charted, findings were summarised and categorised into codes, sub-themes and main themes. Four overarching themes were developed: ‘ systems and structures’, ‘personal capacities’, ‘professional competence’ and ‘mediating processes’ with a number of sub-themes (see Fig. 3 : Theme and sub-themes derived from data analysis ).

Themes and sub-themes derived from data analysis

The challenges, facilitators and the coping strategies shown to affect the transition into practice for new graduates from various health professions will now be discussed in more detail.

Theme 1: Systems and structures

The theme ‘ systems and structures’ reflects the barriers new health practitioners had to overcome and the challenges they faced during transition to practice; it comprises five sub-themes, namely workplace constraints, workloads, support and guidance, expectations, and respect and recognition.

Workplace constraints

Among the challenges encountered by new health professionals were those relating to the complexity of systems in the workplace. New health professionals reported having a naive understanding of the hierarchy of the system, administrative processes, workplace politics and organisational dynamics; this impacted on their transition into practice [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 16 , 33 ]. One study reported that, not knowing the “what, how, why, where and when” of workplace routines posed various challenges for new health professionals [ 4 ]. Variations in operations and administration also served as a source of frustration for new health professionals as they moved between workplaces [ 36 ]. New health professionals were expected to automatically adapt to ‘the-way-things-are-done’ and the ‘it-is-always-done-this-way’ operational culture in the wards [ 15 ]. Many of these procedures were experienced as contrary to what new health professionals had been taught, thus causing confusion [ 17 ].

Complex and overwhelming work-related responsibilities were experienced among new health professionals [ 3 , 4 , 16 , 29 , 31 ]. One study reported that new health professionals were expected to handle complex cases and procedures which they considered unreasonably beyond their capabilities as novice professionals [ 3 ]. Research also reported heavy patient loads among new health professionals which require them to either work overtime or work under pressure in order to meet all responsibilities [ 32 ]. New health professionals generally felt overworked at the end of the day [ 28 ].

Respect and recognition

A lack of respect and recognition for new health professionals during transition into practice was reported. Phillips et al [ 11 ] suggested that new health professionals were not afforded the respect they deserved, especially those that were younger. They emphasized that, lack of respect undermined new health professionals’ self-confidence, which translated into a lack of self-worth [ 11 ]. Unprofessional behaviour from other health professionals or senior colleagues, included experiences of being treated as subordinates, [ 17 ] bullying and insults [ 5 ], impacted negatively on the adjustment of new health professionals. Reynold et al [ 30 ] and Tryssenaar [ 33 ] reported that new health professionals did not feel valued in their practice. In fact, one study reported that new health professionals considered quitting their jobs after the first year due to lack of recognition and appreciation and an overall experience of dissatisfaction at work [ 29 ].

Support and guidance

The importance of having a well-structured system of support and guidance for new health professionals during their transition was emphasized. New health professionals who received sufficient orientation reported doing well during their transition into practice [ 11 , 13 , 16 , 31 , 32 ]. Conversely, new health professionals who did not get sufficient orientation encountered difficulties with the transition [ 4 , 16 , 21 , 26 ]. In addition to orientation programmes, strategies found to support new health professionals’ transition into practice included residency programmes [ 24 ], preceptorship programmes [ 13 , 28 , 31 ] and mentoring programmes [ 5 , 16 , 22 ]. New health professionals needed support from experienced senior colleagues [ 4 , 5 , 11 , 16 , 23 , 30 , 31 ] as well as peers [ 4 ]. New health professionals reported feeling motivated to perform better when they received feedback on their performance from other health professionals [ 34 ] and clients [ 32 ]. Particular emphasis was also placed on supervision as an effective strategy to help new health professionals overcome the stressors of the transition [ 6 , 7 , 11 , 13 ].

Expectations

New health professionals reported feeling overwhelmed by unrealistically high expectations placed on them [ 3 , 13 , 25 , 26 , 29 ]. Labrague et al [ 3 ] reported that new health professionals felt pressured and stressed when unachievable expectations were placed on them. Nurses in Clare & Loon’s [ 5 ] study expressed gratitude to their superiors for having realistic expectations of their skills. They further emphasized that realistic expectations gave them the opportunity to grow their confidence [ 5 ]. Furthermore, new health professionals reported that they were ignorant of what was expected of them [ 7 , 26 ]. In Zinsmeiter’s [ 35 ] study, new health professionals reported that when all health professionals (new and existing) have clear expectations of their role, the transition becomes comfortable.

Theme 2: personal capacities

In the theme “personal capacities” the personal characteristics of new health professionals that influence their transition from student to health professional were captured; it comprised three sub-themes, namely self-perceived competence, self-confidence, and intrinsic motivation to perform.

Self-perceived competence

One factor that affected new health professionals’ transition into practice was their perception of their own competence. New health professionals’ perception that they do not know enough made them question their competence and readiness for practice [ 4 , 6 , 7 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Several situations were reported where new health professionals were caught in a dilemma related to diagnosis, assessment or treatment procedures [ 5 , 7 , 23 ]. Nurses in Clare’s [ 5 ] study described the overwhelming feeling of inadequacy as the worst aspect of their transition. Feeling inadequate resulted in new health professionals feeling vulnerable and fearful of taking on responsibilities because of their fear of making mistakes [ 23 , 29 ].

Self-confidence

Confidence was emphasized as a personal quality that contributes significantly to the success of transition into practice. However, self-confidence seemed to be determined primarily by new health professionals’ perception of how competent they were and how prepared they were for practice [ 4 , 10 , 11 , 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 32 ]. A quantitative cross-sectional survey by Doherty et al [ 10 ] revealed that new occupational therapy graduates’ perceived self-confidence had a significant positive association with their self-perceived competence level in clinical decision making.

Intrinsic motivation to perform

New health professionals reported several factors motivating them to continue to pursue competence in the face of challenges encountered during transition. The fact that they were playing an integral role of changing the health of patients for the better motivated them to persist. Others found motivation by associating their role to the spiritual benefits they expected in future [ 17 ]. Other new health professionals were motivated by the excitement in acquiring new skills and growing in their professions [ 3 , 5 ].

Theme 3: Professional competences

This theme reflected the relationship between knowledge, skills and attitudes new health professionals acquired through their education, and practising in the field. Three sub-themes emerged, namely academics-practice disparity, professional knowledge and skills, and practical experiences.

Academics-practice disparity

Research findings reported a dichotomy between what was learnt in the classroom and the expectations of actual performance in practice [ 3 , 4 , 16 , 21 , 29 ]. De Bellis et al [ 4 ] emphasized that the knowledge participants in their study acquired from their undergraduate education was not applicable in their practice. The incongruency between education and practice was believed to often lead to a reality shock in the practice environment [ 24 ]. The sources reviewed suggested that new health professionals experienced high levels of tension, coupled with anxiety and nervousness upon entering the world of practice [ 6 , 7 , 20 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 32 , 33 ]. O’shea et al. [ 23 ] emphasized that the ‘reality shock’ and anxiety among new health professionals was intense, particularly in the first five months of transition into practice. New health professionals often experienced disconnect between their expectations of practice and the reality of practice [ 32 ]. They experienced varying levels of stress beyond their expectations which impacted their transition [ 3 , 6 , 13 , 20 , 21 , 25 , 26 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. New health professionals often felt incapable of managing stressful emotional work-related situations such as death and dying [ 13 , 20 , 23 ].

Professional knowledge and skills

The sources reviewed suggested that it is in practice that new health professionals become aware of deficits in their knowledge and skills. The gap between education and practice can cause a mismatch between new health professionals’ expectations of their roles and what is actually practiced in the field, leading to role confusion [ 6 , 13 , 29 ]. New health professionals demonstrated inadequacy in clinical practice skills such as communication skills [ 10 , 22 , 24 ], organisational and management skills [ 16 , 20 , 22 ], clinical decision-making skills [ 5 , 22 ] and skills required for specific practice areas [ 6 , 16 , 29 ]. Newly qualified occupational therapists in a study by Toal-Sullivan [ 32 ] reported that they felt unprepared in specialised clinical skills, such as splinting, cognitive remediation, wheelchair prescription, hand therapy and home safety equipment.

Practical experience

Inadequacies in the knowledge and skills of new health professionals was strongly associated with insufficient practical and clinical exposure in their undergraduate training [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 21 ]. Increasing hands-on experience of new health professionals during education can help prevent inadequate knowledge and skills during practice [ 7 ]. Occupational therapists in their first year of practice emphasized that prior clinical placement experience helped ameliorate the stress and uncertainties that characterised transition into practice [ 7 ]. Brennan et al [ 26 ] also emphasized that new health professionals should cultivate a ‘doing, not observing’ attitude during transition into practice.

Theme 4: Mediating processes

This theme captured the strategies employed by new health professionals to change or manage challenges they encountered during transition into practice. Four sub-themes emerged, namely learning as an ongoing process, establishing supportive contacts, asking for help, and effective time management.

Learning as an ongoing process

Research emphasized the importance of new health professionals recognising that professional competence comes through continuous learning and experience [ 7 , 17 , 33 ]. New health professionals should not expect themselves to know everything when transitioning into practice, rather, they should view their knowledge and skills within the confines of being a new health professional [ 18 ]. With this mindset, new health professionals were advised to strive towards professional competence through personal reading [ 4 , 22 ], revisiting lecture notes [ 4 ], taking continuing education courses [ 6 ], learning from the mistakes they make [ 25 ], creating informal learning culture together with peers [ 36 ] and observing and learning from experienced senior colleagues [ 25 ].

Establishing supportive contacts

The sources reviewed suggested that new health professionals seek to improve their clinical competence through establishing contacts with significant others. New health professionals reported that their peers assisted in alleviating the stressors of transition [ 4 , 6 , 11 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 23 , 25 , 31 ]. New health professionals established meaningful interactions with peers through peer support meetings [ 5 , 25 ], study groups [ 5 ], networking [ 6 , 17 ] and peer debriefing sessions [ 5 , 22 ]. Other supportive contacts included previous lecturers [ 4 ], senior colleagues [ 5 , 6 ] and fellow health professionals [ 7 , 17 , 30 ]. New health professionals reported that ensuring meaningful personal and social lives helped alleviate transition stressors [ 17 , 29 , 30 ]. Furthermore, healthy interprofessional relationship with other members of the multidisciplinary team was emphasized as a positive factor in transition [ 28 , 30 ].

Asking for help

New health professionals resorted to ‘asking for help’ when they did not know what to do [ 36 ] and sought supervision when confronted with new situations [ 4 , 6 ]. In situations where there were no mentors and supervisors, new health professionals sought remote mentors and coaches [ 6 ]. Listening and regularly asking questions were also emphasized as coping strategies to ameliorate the challenges of transition [ 4 , 22 ].

Effective time management

Effective time management strategies were found to help alleviate some challenges of transition [ 6 , 7 ]. New occupational therapy graduates reported that managing their time well enabled them to deal with overwhelming work schedules, prevented having to work overtime and allowed time for meaningful personal and social lives [ 6 ].

Conclusions

The sources included in our review highlighted numerous challenges faced by new health professionals during their transition into practice and support strategies used to ameliorate the difficulties experienced. The coping strategies employed by new health professionals in making a successful transition were included in Table 3 . The review confirmed the importance of tried and tested strategies; yet, highlighted the importance of making these strategies accessible. Considerations for accessibility included availability, quality, timing and format of such strategies.

Orientation programmes are needed. These should include information on systems and procedures, presented in a format that is easily accessible to new generation learners, and detailed and comprehensible enough to deal with challenges that cause unnecessary anxiety. Rather than once-off orientation programmes, modes of delivery and timing should be considered to ensure availability of information when most needed. Additionally, cumbersome and irrelevant systems and structures should be modified to make navigation easier. This may go a long way to improve accessibility and productivity.

In addition to ongoing support from line managers, new health professionals benefit from mentor and peer support. Orientation programmes should encourage new health professionals to request support or supervision from senior colleagues. Conversely, senior colleagues should maintain a good professional relationship with new health professionals and accord them due respect and recognition. This will make it easy for new graduates to approach senior colleagues for professional assistance.

Support programmes are required to assist new health professionals with closing the gap between learning and practice. Education programmes should aim at increasing the practical experiences of students to foster development of skills such as communication skills, clinical decision-making skills, management, organisational skills and time management strategies. However, care should be taken to normalize the gap between competencies new health professionals bring to the field and the clinical expectations they face. This should be done in such a way as to remove the expectation that new health professionals should already have all the competencies required to work effectively, thus promoting engagement in continued professional development activities as a virtue.

Ongoing learning should be an explicit expectation for all health professionals. Continued professional development activities should be readily available and attendance of these encouraged. Line managers and mentors of new health professionals should be sensitised to the fact that certain competencies can only be acquired during the transition into practice. This should be done in such a way as to empower them to support the learning that is still required.

Collaborative formulation of development plans and guided navigation of available support resources should be encouraged. As part of support or mentoring programmes, more experienced health professionals could guide new health professionals to reflect on areas of development and explore and identify personal strengths and the environmental resources that can be used to meet the demands of their new role. Supervisors, mentors or senior colleagues therefore assist new health professionals to identify areas of development, set goals and develop a plan of action with regard to specific knowledge and skill set they are in need of acquiring or further developing. This could assist in increasing new health professionals’ belief in their personal capabilities.

We recommend both formal and informal systems fostering the creation of support networks which ideally should be quality assured and included in performance appraisal structures. Additionally, new health professionals should utilise supportive contacts such as peer support meetings, study groups, peer debriefing sessions and previous lecturers and educators. New health professionals who find themselves in settings without supervisors can seek remote mentors and coaches who can offer long-hand supervision using virtual means. New health professionals should be open-minded and be willing to ask questions and seek help.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

Naidoo D, Wyk J, Van Joubert RN. Are final year occupational therapy students adequately prepared for clinical practice? A case study in KwaZulu-Natal. South African J Occup Ther. 2014;44(3):24–8.

Morley M, Rugg S, Drew J. Before preceptorship: new occupational therapists’ expectations of practice and experience of supervision. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70(6):243–53.

Article Google Scholar

Labrague L, McEnroe-Petite D, Leocadio M. Transition experiences of newly graduated Filipino nurses in a resource - scarce rural health care setting: a qualitative study. Nurs Forum. 2019;54(2):298–306.

De Bellis A, Glover P, Longson D, Hutton A. The enculturation of our nursing graduates. Contemp Nurse. 2001;11(1):84–94.

Clare J, Van Loon A. Best practice principles for the transition from student to registered nurse. Collegian. 2003;10(4):25–31.

Tryssenaar J, Perkins J. From student to therapist: exploring the first year of practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(1):19–27.

Seah CH, Mackenzie L, Gamble J. Transition of graduates of the master of occupational therapy to practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58:103–10.

McCombie RP, Antanavage ME. Transitioning from occupational therapy student to practicing occupational therapist: first year of employment. Occup Ther Heal Care. 2017;31(2):126–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2017.1307480 .

Toal-Sullivan D. New graduates’ experiences of learning to practice occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2006;69(11):513–24.

Doherty G, Stagnitti K, Schoo AMM. From student to therapist: follow up of a first cohort of bachelor of occupational therapy students. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56(5):341–9.

Phillips C, Kenny A, Esterman A, Smith C. Nurse education in practice A secondary data analysis examining the needs of graduate nurses in their transition to a new role. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(2):106–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.07.007 .

Hummell J, Koelmeyer L. New graduates: perceptions of their first occupational therapy position. Br J Occup Ther. 1999;62(8):351–8.

Melman S, Ashby SE, James C. Supervision in practice education and transition to practice: student and new graduate perceptions. Internet J Allied Heal Sci Pract. 2016;14(3):1–16.

Moores A, Fitzgerald C. New graduate transition to practice: How can the literature inform support strategies? Aust Heal Rev. 2017;41(3):308–12.

Regan S, Wong C, Laschinger HK, Cummings G, Leiter M, Macphee M, et al. Starting Out : qualitative perspectives of new graduate nurses and nurse leaders on transition to practice. J Nurs Manag. 2017:25(4):246–55.

Opoku EN, Van Niekerk L, Khuabi L-AJ-N. Exploring the transition from student to health professional by the first cohort of locally trained occupational therapists in Ghana. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1865448 .

Awaisi HAL, Cooke H, Pryjmachuk S. The experiences of newly graduated nurses during their first year of practice in the Sultanate of Oman, a case study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.06.009 .

Lee S, Mackenzie L. Starting out in rural new south wales : the experiences of new graduate occupational therapists. Aust J Rural Heal. 2003;11(1):36–43.

Opoku EN, Van Niekerk L, Khuabi L-AJ-N. Exploring the factors that affect new graduates ’ transition from students to health professionals : a systematic integrative review protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):1–5.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review : updated methodology. Methodol issues Nurs Res. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Google Scholar

Uys ME, Buchanan H, Van Niekerk L. Strategies occupational therapists employ to facilitate work-related transitions for persons with hand injuries : a study protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:1–7.

Maguire M, Delahunt B. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J. 2017;9(3):3351–414.

O’Shea M, Kelly B. The lived experiences of newly qualified nurses on clinical placement during the first six months following registration in the Republic of Ireland. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(8):1534–42.

Abualrub RF, Abu Alhaija’a MG. Perceived benefits and barriers of implementing nursing residency programs in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;00(000–000):1–9.

Mostrom E, Black LL, Perkins J, Hayward L, Ritzline PD, Blackmer B, et al. The first year of practice: an investigation of the professional learning and development of promising novice physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2010;90(12):1758–73.

Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, Archer J, Barnes R, Bleakley A, et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor : today ’ s experiences of Tomorrow ’ s Doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44:449–58.

Casey K, Fink R, Krugman M, Propst J. The graduate nurse experience. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34(6):303–11.

Mangone N, King J, Croft T, Church J. Group debriefing: an approach to psychosocial support for new graduate registered nurses and trainee enrolled nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2005;20(2):248–57.

Nour V, Williams AM. ‘“ Theory becoming alive ”’: the learning transition process of newly graduated nurses in Canada. Can J Nurs Res. 2018;0(0):1–8.

Reynolds EK, Cluett E, Le-may A. Fairy tale midwifery — fact or fiction : The lived experiences of newly qualified midwives. Br J midwifery. 2014;22(9):660–8.

Tastan S, Unver V, Hatipoglu S. An analysis of the factors affecting the transition period to professional roles for newly graduated nurses in Turkey. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(3):405–12.

Toal-sullivan D. New graduates ’ experiences of learning to practise occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2006;69:513–24.

Tryssenaar J. The lived experience of becoming an occupational Therapist. Br J Occup Ther. 1999;63(3):107–12.

Wangensteen S. The first year as a graduate nurse – an experience of growth and development. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(14):1877–85.

Zinsmeister LB, Schafer D. The exploration of the lived experience of the graduate nurse making the transition to registered nurse during the first year of practice. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2009;25(1):28–34.

Bearman M, Lawson M, Jones A. Participation and progression : new medical graduates entering professional practice. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2011;16:627–42.

Seah CH, Mackenzie L, Gamble J. Transition of graduates of the master of occupational therapy to practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58(2):103–10.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Mrs. Ingrid Van der Westhulzen (Subject librarian) at the University of Stellenbosch for contributing towards developing the search strings for the integrative review. A warm appreciation goes to Elizabeth Casson Trust, UK and Marian Velthuijs, Netherland for supporting the master’s study out of which this integrative review was done.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Eric Nkansah Opoku

Present address: Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

Authors and Affiliations

Division of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Francie Van Zijl Dr. Tygerberg Medical Campus, Cape Town, South Africa

Eric Nkansah Opoku, Lee-Ann Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi & Lana Van Niekerk

Department of Occupational Therapy and Human Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Health & Life Sciences; Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All three authors of this article contributed to the conceptualisation, drafting, development and editing of this integrative review. ENO drafted the initial manuscript in partial fulfillment of his master’s degree, LVN and LJNK guided the development of the manuscript and made substantial conceptual and editorial contributions. All authors participated in editing the final version and have approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eric Nkansah Opoku .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Opoku, E.N., Khuabi, LA.JN. & Van Niekerk, L. Exploring the factors that affect the transition from student to health professional: an Integrative review. BMC Med Educ 21 , 558 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02978-0

Download citation

Received : 01 December 2020

Accepted : 12 October 2021

Published : 02 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02978-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Role transition

- Clinical practice

- New clinicians

- Professional competence

- Novice professionals

- Professional practice

- Systematic literature review

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 28 July 2017

New graduate nurses’ experiences in a clinical specialty: a follow up study of newcomer perceptions of transitional support

- Rafic Hussein ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7094-358X 1 , 2 ,

- Bronwyn Everett 1 , 2 ,

- Lucie M. Ramjan 1 , 2 ,

- Wendy Hu 1 &

- Yenna Salamonson 1 , 2

BMC Nursing volume 16 , Article number: 42 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

56k Accesses

79 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Given the increasing complexity of acute care settings, high patient acuity and demanding workloads, new graduate nurses continue to require greater levels of support to manage rising patient clinical care needs. Little is known about how change in new graduate nurses’ satisfaction with clinical supervision and the practice environment impacts on their transitioning experience and expectations during first year of practice. This study aimed to examine change in new graduate nurses’ perceptions over the 12-month Transitional Support Program, and identify how organizational factors and elements of clinical supervision influenced their experiences.

Using a convergent mixed methods design, a prospective survey with open-ended questions was administered to new graduate nurses’ working in a tertiary level teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia. Nurses were surveyed at baseline (8–10 weeks) and follow-up (10–12 months) between May 2012 and August 2013. Two standardised instruments: the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale (MCSS-26) and the Practice Environment Scale Australia (PES-AUS) were used. In addition to socio-demographic data, single –item measures were used to rate new graduate nurses’ confidence, clinical capability and support received. Participants were also able to provide open-ended comments explaining their responses. Free-text responses to the open-ended questions were initially reviewed for emergent themes, then coded as either positive or negative aspects of these preliminary themes. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse the quantitative data and the qualitative data was analysed using conventional content analysis (CCA). The study was approved by the relevant Human Research Ethics Committees.

Eighty seven new graduate nurses completed the follow-up surveys, representing a 76% response rate. The median age was 23 years (Range: 20 to 53). No change was seen in new graduate nurses’ satisfaction with clinical supervision (mean MCSS-26 scores: 73.2 versus 72.2, p = 0.503), satisfaction with the clinical practice environment (mean PES-AUS scores: 112.4 versus 110.7, p = 0.298), overall satisfaction with the transitional support program (mean: 7.6 versus 7.8, p = 0.337), satisfaction with the number of study days received, orientation days received (mean: 6.4 versus 6.6, p = 0.541), unit orientation (mean: 4.4 versus 4.8, p = 0.081), confidence levels (mean: 3.6 versus 3.5, p = 0.933) and not practising beyond personal clinical capability (mean: 3.9 versus 4.0, p = 0.629).

Negative responses to the open-ended questions were associated with increasing workload, mismatch in the level of support against clinical demands and expectations. Emergent themes from qualitative data included i) orientation and Transitional Support Program as a foundation for success; and ii) developing clinical competence.

Conclusions

While transitional support programs are helpful in supporting new graduate nurses in their first year of practice, there are unmet needs for clinical, social and emotional support. Understanding new graduate nurses’ experiences and their unmet needs during their first year of practice will enable nurse managers, educators and nurses to better support new graduate nurses’ and promote confidence and competence to practice within their scope.

Peer Review reports

Acute healthcare settings in Australia and developed countries are rapidly evolving [ 1 ] and becoming increasingly complex [ 2 ]. For newly graduated registered nurses (NGNs), transitioning from university to practice in acute settings remains challenging, stressful and emotionally exhausting [ 3 ] as they strive to deliver safe nursing care amidst heavy workloads, increased accountability and responsibility for their patient care [ 4 ]. Concerns about new graduate nurses’ ability to cope and deliver safe nursing care have contributed to the development of transitional support programs alongside various forms of clinical supervision to promote the development of clinical proficiency, support professional development and improve new graduate nurse retention [ 5 ].

To fully comprehend the transitional experience of new graduates it is important to understand their clinical environment and workplace conditions. New graduate nurses continue to enter a work environment characterised by nursing staff shortages, increasing patient acuity [ 6 ] and at times limited access to clinical support [ 7 ]. Although a positive workplace environment facilitates more effective transition of graduate nurses and significantly influences their job satisfaction [ 6 ], negative experiences have been found to result in feelings of heightened work stress for up to one year after graduation, with contributory factors including poor work environments, poor clinical supervisors and poor nurse-doctor relations [ 8 ]. Not only do these early experiences impact on new graduate nurses’ levels of satisfaction but they can influence long term career intentions [ 5 ]. Of concern is that current research on the experiences of first year nurses still reflects the findings of the research on their counterparts a decade earlier; that is, they still struggle to meet expectations placed on them, face difficulties to manage unreasonable workloads, high levels of stress, burnout and feeling at times unsafe [ 9 ].

New graduate nurses’ experiences in the first year of practice are often described as overwhelming and stressful as they strive to apply newly acquired skills, deliver quality patient care and ‘fit in’ [ 10 ]. Importantly, the first year of practice is also a time of high attrition with rates of up to 27% reported in the literature [ 11 ]. These concerns have contributed internationally to the development of new graduate programs [ 12 ], often referred to as transitional programs, to promote clinical proficiency, support NGNs’ professional development and improve retention.

Numerous studies have reported the impact of workplace stress, uncivil behavior and burnout on the retention of new graduate nurses [ 9 , 11 , 13 ]. However, how best to facilitate newcomer transition in acute care settings remains a subject of ongoing research. Although there is consensus in the literature that a supportive organizational environment (both at the ward and organizational level) is needed for the safe and successful integration of novice nurses, few authors have detailed the experiences and perceptions of new graduate nurses and how these change over time. Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo and Tucker [ 14 ] describe the process of newcomer nurses being socialized into organizations, sometimes referred to as ‘onboarding’, during which time they acquire the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors to perform effectively and adjust to their work surroundings [ 15 ]. However, this process has been shown to be negatively impacted by rising patient acuity and understaffing and in some cases, exacerbated by fear of failure [ 16 ].

Transitional programs are one intervention to address these challenges; the format varies, but they are designed to assist new graduate nurses’ transition into the nursing workforce and profession within an institutional context. Over 12 months, the program offers new graduates exposure to a variety of clinical settings including facility and ward orientation, 2–3 ward rotations, 4–5 pre-planned study days, formal and informal clinical supervision. Such programs aim to assist novice nurses with facility and ward orientation to consolidate theoretical learning, critical skills and judgement in their new professional role [ 11 ]. To ensure a successful transition from a novice nurse to competent registered nurse (RN), it is argued that structured professional development programs are provided [ 17 ] in a supportive manner to help newly graduated nurses integrate into organizational systems and processes [ 7 ].

Given the implications for nursing workforce retention, it is thus important to examine the effectiveness of transitional support programs and the factors associated with positive and negative new graduate experiences. The overall aim of this study was to examine change in new graduate nurses’ perceptions over a 12-month transitional support program (TSP), also commonly known as nurse residency program. Specifically, this study sought to (i) identify elements of clinical supervision that influenced new graduates’ experiences during the program; (ii) to examine changes in new graduate nurses’ perceptions and clinical supervision, confidence levels, satisfaction with the orientation program and their practice environment over the 12-month transitional period and (iii) explore their experiences during the transitional period and identify change between baseline and follow-up.

This convergent mixed methods study was part of a larger project [ 18 ] which evaluated the effectiveness of clinical supervision practice for new graduate nurses in an acute care setting (Fig. 1 ). The value of mixed methods research can be dramatically enhanced through the integration of quantitative and qualitative data [ 3 , 19 ].

Overview of Convergent Mixed Methods Design [ 3 , 19 ]

In this paper, we integrate an analysis of quantitative data with a separate analysis of the qualitative open-ended responses from a survey completed by new graduate nurses enrolled in a transitional support program. The survey was initially administered 8–10 weeks after the commencement of the transitional support program and again to the same participants 10–12 months after commencement. These data collection points were selected for pragmatic reasons; that is they coincided with programmed study days and ensured participants had sufficient time in each of their rotations to report their transitioning experience and clinical competence.

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted in a principal referral and teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia. The hospital has 855 beds and employs over 1500 nursing staff across a range of clinical streams and specialities, including state-wide services in critical care and trauma. All new graduate nurses ( n = 140) enrolled in the 12-month transitional support program were invited to participate in this study at facility orientation, study days and by emailed invitations. Programmed study days are pre-allocated study days for new graduates throughout the transitional support programme. ‘Orientation days’ refers to the number of days new graduate nurses were given as supernumerary on the ward. This means they were ‘buddied up’ for the shift or preceptored by another registered nurse or clinical nurse educator. Data collection for this study was conducted between May 2012 and August 2013 during group TSP study days, shift overlap times on the ward and other times convenient to participants. Participants completed the self-report instruments independently.

Data collection

Participant characteristics assessed in this study included i) age; ii) gender; iii) history of previous paid employment, and iv) previous nursing experience. Single-item Likert scale measures were used to assess how frequently (0 = never, 10 = always) NGNs were placed in clinical situations where they did not feel confident or which were beyond their clinical capability. In addition, three practice environment factors were included: i) assigned unit (critical care or non-critical care area); ii) level of satisfaction with unit-based orientation using a single-item question and; iii) satisfaction with the clinical supervision offered within the TSP. Participants were asked to give a reason for their rating or elaborate by providing an example for the single-item measures. Also administered at baseline and follow up were two validated instruments, the 26-item Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale (MCSS-26) used to assess NGN perception of the quality of clinical supervision [ 20 ], and the Practice Environment Scale - Australia (PES-AUS) used to assess satisfaction with their clinical practice environment [ 21 ]. The PES-AUS was modified with a midpoint of 3 = ‘unsure’, as it was anticipated that some new graduates may not be familiar with some items of the scale. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for both instruments were 0.90 and 0.91 respectively, indicating high internal consistency.

Ethics approval was granted by Western Sydney University and South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committees (H10055, LNR/11/LPOOL/510). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Permission to use the MCSS-26 and PES-AUS was obtained by the authors.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using the statistical software package, IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 [ 4 ]. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and expressed as median and range. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. To examine for change in the study cohorts’ responses between baseline and follow-up, we used Pearson’s chi-square for categorical variables, paired t -test or Wilcoxon signed rank test for changes between baseline and follow-up. A p -value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

A Conventional Content Analysis (CCA) technique was used to analyze the open-ended responses. This approach allows the analysis (themes and names for the themes) to be derived from the open-ended responses, rather than being preconceived [ 22 ]. The open-ended responses were read multiple times by the first author (RH) to achieve immersion [ 22 ]. Responses were then read for frequently repeated words (e.g. support, workload, skills), denoting main views on experiences and transition were highlighted within an excel spreadsheet. First impressions of open-ended responses were noted and formed the basis of development of categories or ‘sub-themes’ for grouping under main ‘themes’.

Open-ended responses to the single item measures were reviewed for emergent themes by two researchers (RH and LR). Initially 20% of the free text responses were coded independently by two researchers (RH & YS), categorizing the text as either positive or negative aspects of these preliminary themes. Any differences in coding were then discussed to achieve consensus before the continuation of further text coding. RH completed the remainder of the coding. Data integration was achieved by transforming (‘quantitizing’) the qualitative data into numerical form [ 19 ].

Using the six subthemes as categories, the frequencies of the free-text responses were grouped into positive and negative dimensions, based on the number of times a code referring to a sub-theme was found in a participants’ survey. A numerical value of “1” was given for each positive comment and a score of “0” if the comment was negative. An aggregate score for each subtheme was thus computed (Table 1 ). The qualitative responses were then ‘transformed’ into quantitative data, then integrated with illustrative examples from the original dataset [ 23 ].

Quantitative findings

Sample characteristics.

A total of 140 new graduate nurses enrolled in the transitional program. One hundred and fourteen new graduates (81%) completed the baseline survey, and of these, 87 (76%) completed follow-up surveys. There were no statistically significant differences in age, MCSS-26 or PES-AUS scores between responders and non-follow-up responders.

The median age was 23 years (Range: 20 to 53) and over three-quarters of the sample were female (78%). Over half of the new graduates had previous nursing experience, with most previously employed as Assistants in Nursing (AINs) (unlicensed workers). During the two clinical rotations within the transitional support program, approximately two-thirds (63%) of new graduates worked in non-critical care areas with the remainder (37%) allocated to work in critical care areas.

Experiences over time: Baseline vs follow up