- Skip to main content

India’s Largest Career Transformation Portal

Essay on Youth Culture Today for Students and Children

January 20, 2020 by Sandeep

500+ Words Essay on Youth Culture Today

What is Youth Culture? Youth Culture is the term used to describe the ways teenagers lead and conduct their lives. It can refer to their interests, styles, behaviours, music choices, beliefs, vocabulary, clothes, sports preferences and dating relationships.

The concept behind youth culture is that adolescents are a subculture with norms, behaviours and values that differ from the main culture of older generations within society.

Youth culture, especially in the western world, is more about what they wear, the lifestyle they support, the electronic gadgets they own, as a majority or group. There are even competitions for higher ranks, wherein the high ranking ones are the most beautiful, richest, own a wider array of gadgets, and have the most amount of cool friends.

It isn’t that much about who you are but more about what you have. Reality television shows, magazines and the newest gadgets are what rules the youth and the world at large today. It is getting quite out of hand, and because of the new life-stage as ‘teens’, young people don’t realise the big importance they have on the future.

Development of Youth Culture

Youth culture was first developed in the 20th century when it became more common for adolescents to gather together in groups or fandom. Historically, prior to this time, many adolescents spent a large portion of their time with adults or with their siblings. But the introduction of compulsory schooling and other societal changes made the joint socialisation of adolescents more prevalent.

Psychologists such as Erik Erikson have theorised that the primary goal in the developmental stage of adolescence is to answer the question, “Who am I?” If this is the case, it is natural to assume that in finding out one’s own identity, one would seek others within the same age group and generation to grow and learn together and understand the social norms and values of society.

Theorists such as Adele M. Fasick agree that adolescents are in a confused state of mind and that identity development happens during this time as they exert independence from parents and have a greater reliance on their peer groups.

Characteristics of the Youth Today

The youth of today are not like any other preceding generations. They are stronger, more united, and far more understanding. One of the main characteristics of the youth of today is their firm determination. Some might misunderstand this trait for stubbornness, which is also true.

However, our youngsters set their sights very firmly on a certain goal, and do everything in their power to achieve it, sometimes going even beyond what is in their hands to do extra.

This gives them stamina and immense courage to accomplish their target on time with utmost perfection. If we closely observe their behaviour, we notice that their dedication and sincerity towards the work increases day-by-day.

Our young generation also has a very good capacity to withstand stressful situations. They can manage any and every circumstance in a patient manner. Gender is no bar to the withstanding ability. Everyone is equally tested and treated in the world of employment and performance, and the parameters are very competitively met by our charming youth.

The ability to manage stress is also one of the primary investigators in the field of psychoneuroimmunology, which is the study of the relationship between psychological factors and working of the immune system. Seeing as our youth ward off stress not just by ignoring it, but working around it, the youth are also constantly in good health .

One of the down factors is that the blood of the youth gets heated up much too frequently. The youth lacks patience in some areas, and they all need their tasks to be completed as and when required and that too immediately. The loss of patience and the hot temper is often the cause of violence and rage. This is evident from the new-fangled tradition of cursing horrendously at the littlest of things.

Our youthful generation is also extremely tech-savvy. They can complete every task in a single click. The cyber world has given them a life of ease and comfort, in comparison to the long hours that used to be spent at offices. However, this has a downside too. The tech savvy youth have lost the values of physical exercise.

Running games are now played virtually on a gaming screen. These factors are landing the youth into poor health conditions at a tender age, especially due to factors such as obesity. We have reached an era where our youth are unable to perceive anything without the Internet. They have become completely dependent on technology.

Probably the most defining characteristic of the youth of today is their strong rebellion. Now, this might be taken as a bad quality by a lot of people, but in my opinion, this is an excellent thing. The youth do not simply rebel against anything and everything.

They pick and choose their battles carefully and the only rebel against the wrong things in our society. For example, the youth are standing up for the rights of women. They have taken up the fight against racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and many other problems.

The older generations often criticise the youth for being lazy and not being outdoors all the time. But I believe that that is a wrong notion. They may not be as active as the earlier generations in terms of playing games, but the important thing is, they are keeping themselves busy doing something.

The youth don’t just sit back, relaxing. When they see a problem, they devise methods to overcome it, instead of sitting and gossiping about it. They hold protests, strikes and marches in support of their demands.

The youth are currently the only people working towards saving of our planet from climate change , seeing as no one else is taking it seriously. Contrary to popular belief, there are many other sides to this new youth culture than just sex and teenage pregnancy.

The youngsters are well aware of the balancing equations of life. The general IQ and social awareness cause them to help in the upliftment of the rural segments of the world. They are the ones who plan and promote the development of the under-developed nations. They are passionate about their nations, and sometimes, even more, passionate about the world as a nation together.

Reasons for the Youth Culture of Today

The youth of today are unlike any before in all of history. This is because of several factors. The world is ever changing, developing in certain fields and regressing in others.

The previous generations, when they were youth, never had to experience the kinds of difficulties and pressures today’s youth go through almost every day. Of course, no one means to undermine the difficulties of past generations.

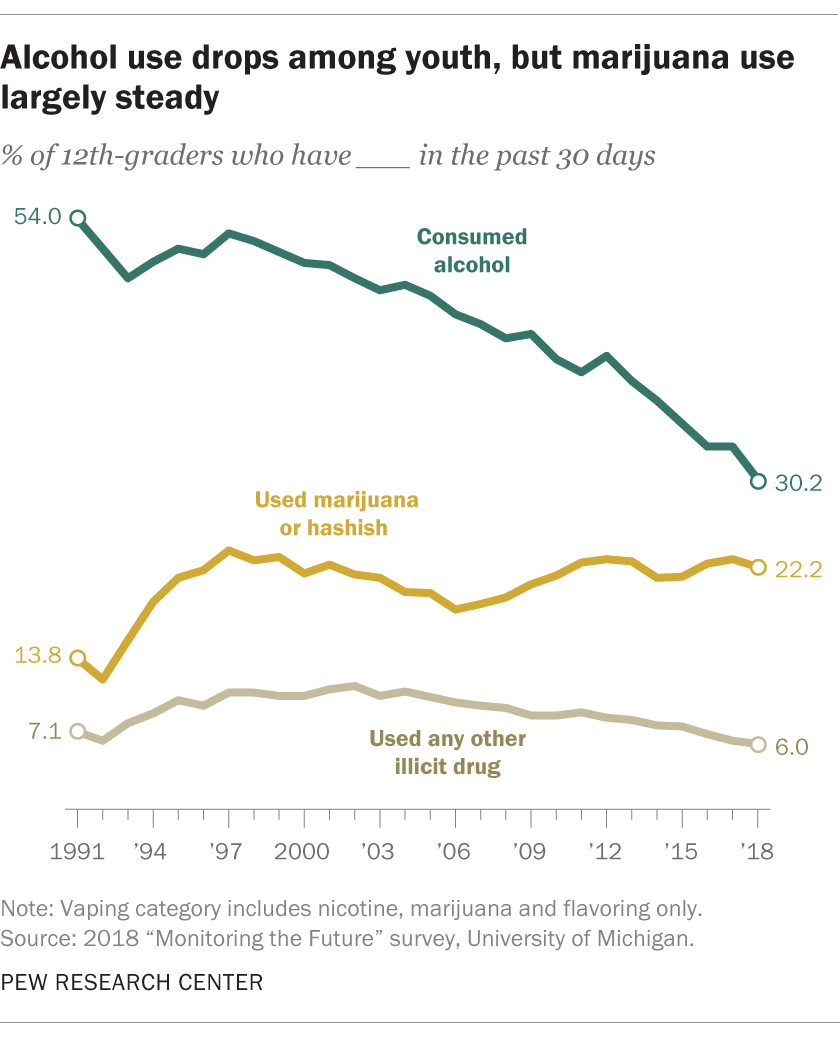

Some of the factors that are responsible for the youth culture of today include the school shootings, the rising paedophilia, easy access to narcotics, the dark web, graphic sexual images on billboards and magazine covers, ever rising racism, and several others. Imagine going to school every day, innocently, and yet never knowing whether you will be coming back home or not.

Young people are being challenged in their everyday lives by the media, their peers and by the school. They are challenged to go beyond their own personal and familial boundaries. Modern technology and advancement have given everyone invaluable tools for communication: cell phones , e-mail, pagers, computers , instant messaging and text messaging, all for the purpose of improving our communication skills.

But very often, although parents are very quick to supply their children with all these communication tools of our modern age, they don’t spend more than fifteen minutes a day speaking to their children on a one-on-one basis.

It is crucial to understand that the youth culture is a type of stereotype wherein we are trying to fit in all the youth of the world. This is not realistically possible. The youth are from all over the world, they glorify in their diversity.

Trying to fit them all into one culture is the same as saying that the lion, dolphin and ostrich are all the same simply because they are all in the animal kingdom.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Teens Today Are Different from Past Generations

Every generation of teens is shaped by the social, political, and economic events of the day. Today’s teenagers are no different—and they’re the first generation whose lives are saturated by mobile technology and social media.

In her new book, psychologist Jean Twenge uses large-scale surveys to draw a detailed portrait of ten qualities that make today’s teens unique and the cultural forces shaping them. Her findings are by turn alarming, informative, surprising, and insightful, making the book— iGen:Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us —an important read for anyone interested in teens’ lives.

Who are the iGens?

Twenge names the generation born between 1995 and 2012 “iGens” for their ubiquitous use of the iPhone, their valuing of individualism, their economic context of income inequality, their inclusiveness, and more.

She identifies their unique qualities by analyzing four nationally representative surveys of 11 million teens since the 1960s. Those surveys, which have asked the same questions (and some new ones) of teens year after year, allow comparisons among Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, and iGens at exactly the same ages. In addition to identifying cross-generational trends in these surveys, Twenge tests her inferences against her own follow-up surveys, interviews with teens, and findings from smaller experimental studies. Here are just a few of her conclusions.

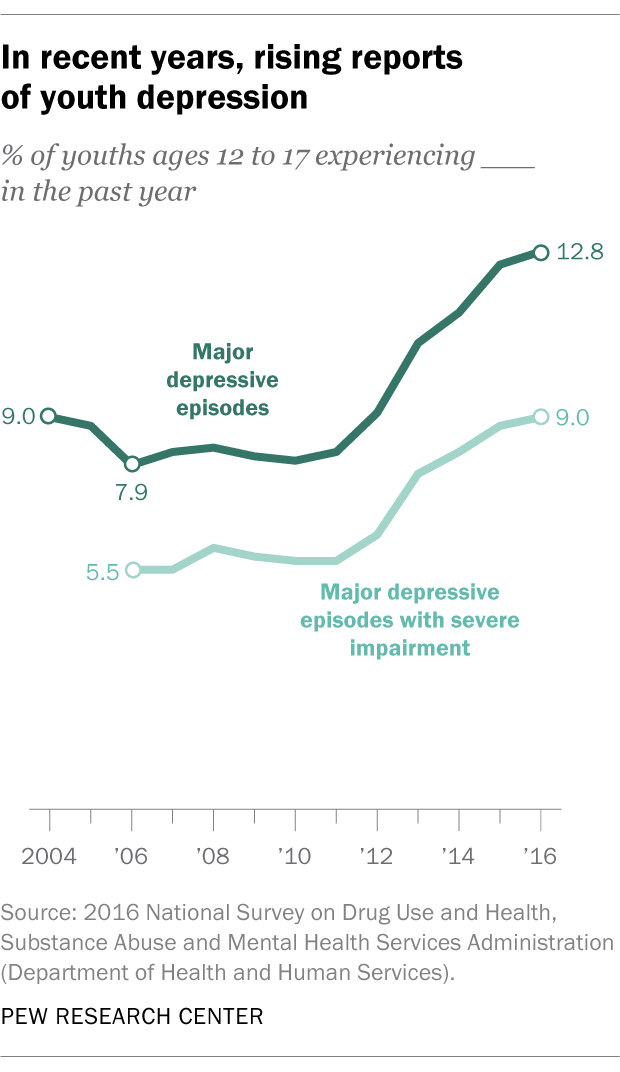

iGens have poorer emotional health thanks to new media. Twenge finds that new media is making teens more lonely, anxious, and depressed, and is undermining their social skills and even their sleep.

iGens “grew up with cell phones, had an Instagram page before they started high school, and do not remember a time before the Internet,” writes Twenge. They spend five to six hours a day texting, chatting, gaming, web surfing, streaming and sharing videos, and hanging out online. While other observers have equivocated about the impact, Twenge is clear: More than two hours a day raises the risk for serious mental health problems.

She draws these conclusions by showing how the national rise in teen mental health problems mirrors the market penetration of iPhones—both take an upswing around 2012. This is correlational data, but competing explanations like rising academic pressure or the Great Recession don’t seem to explain teens’ mental health issues. And experimental studies suggest that when teens give up Facebook for a period or spend time in nature without their phones, for example, they become happier.

The mental health consequences are especially acute for younger teens, she writes. This makes sense developmentally, since the onset of puberty triggers a cascade of changes in the brain that make teens more emotional and more sensitive to their social world.

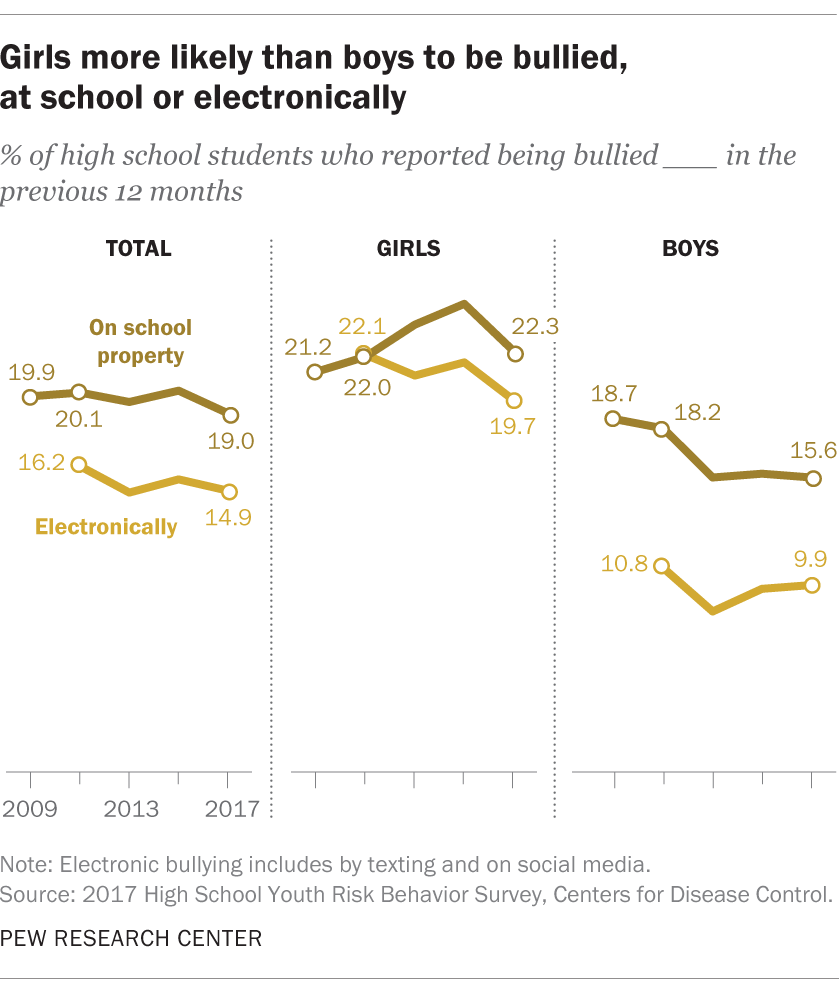

Social media use, Twenge explains, means teens are spending less time with their friends in person. At the same time, online content creates unrealistic expectations (about happiness, body image, and more) and more opportunities for feeling left out—which scientists now know has similar effects as physical pain . Girls may be especially vulnerable, since they use social media more, report feeling left out more often than boys, and report twice the rate of cyberbullying as boys do.

Social media is creating an “epidemic of anguish,” Twenge says.

iGens grow up more slowly. iGens also appear more reluctant to grow up. They are more likely than previous generations to hang out with their parents, postpone sex, and decline driver’s licenses.

Twenge floats a fascinating hypothesis to explain this—one that is well-known in social science but seldom discussed outside academia. Life history theory argues that how fast teens grow up depends on their perceptions of their environment: When the environment is perceived as hostile and competitive, teens take a “fast life strategy,” growing up quickly, making larger families earlier, and focusing on survival. A “slow life strategy,” in contrast, occurs in safer environments and allows a greater investment in fewer children—more time for preschool soccer and kindergarten violin lessons.

More on Teens

Discover five ways parents can help prevent teen depression .

Learn how the adolescent brain transforms relationships .

Understand the purpose of the teenage brain .

Explore how to help teens find purpose .

“Youths of every racial group, region, and class are growing up more slowly,” says Twenge—a phenomenon she neither champions nor judges. However, employers and college administrators have complained about today’s teens’ lack of preparation for adulthood. In her popular book, How to Raise an Adult , Julie Lythcott-Haims writes that students entering college have been over-parented and as a result are timid about exploration, afraid to make mistakes, and unable to advocate for themselves.

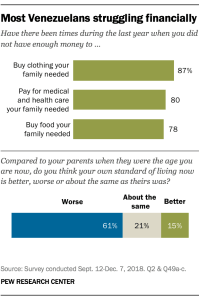

Twenge suggests that the reality is more complicated. Today’s teens are legitimately closer to their parents than previous generations, but their life course has also been shaped by income inequality that demoralizes their hopes for the future. Compared to previous generations, iGens believe they have less control over how their lives turn out. Instead, they think that the system is already rigged against them—a dispiriting finding about a segment of the lifespan that is designed for creatively reimagining the future .

iGens exhibit more care for others. iGens, more than other generations, are respectful and inclusive of diversity of many kinds. Yet as a result, they reject offensive speech more than any earlier generation, and they are derided for their “fragility” and need for “ trigger warnings ” and “safe spaces.” (Trigger warnings are notifications that material to be covered may be distressing to some. A safe space is a zone that is absent of triggering rhetoric.)

Today’s colleges are tied in knots trying to reconcile their students’ increasing care for others with the importance of having open dialogue about difficult subjects. Dis-invitations to campus speakers are at an all-time high, more students believe the First Amendment is “outdated,” and some faculty have been fired for discussing race in their classrooms. Comedians are steering clear of college campuses, Twenge reports, afraid to offend.

The future of teen well-being

Social scientists will discuss Twenge’s data and conclusions for some time to come, and there is so much information—much of it correlational—there is bound to be a dropped stitch somewhere. For example, life history theory is a useful macro explanation for teens’ slow growth, but I wonder how income inequality or rising rates of insecure attachments among teens and their parents are contributing to this phenomenon. And Twenge claims that childhood has lengthened, but that runs counter to data showing earlier onset of puberty.

So what can we take away from Twenge’s thoughtful macro-analysis? The implicit lesson for parents is that we need more nuanced parenting. We can be close to our children and still foster self-reliance. We can allow some screen time for our teens and make sure the priority is still on in-person relationships. We can teach empathy and respect but also how to engage in hard discussions with people who disagree with us. We should not shirk from teaching skills for adulthood, or we risk raising unprepared children. And we can—and must—teach teens that marketing of new media is always to the benefit of the seller, not necessarily the buyer.

Yet it’s not all about parenting. The cross-generational analysis that Twenge offers is an important reminder that lives are shaped by historical shifts in culture, economy, and technology. Therefore, if we as a society truly care about human outcomes, we must carefully nurture the conditions in which the next generation can flourish.

We can’t market technologies that capture dopamine, hijack attention, and tether people to a screen, and then wonder why they are lonely and hurting. We can’t promote social movements that improve empathy, respect, and kindness toward others and then become frustrated that our kids are so sensitive. We can’t vote for politicians who stall upward mobility and then wonder why teens are not motivated. Society challenges teens and parents to improve; but can society take on the tough responsibility of making decisions with teens’ well-being in mind?

The good news is that iGens are less entitled, narcissistic, and over-confident than earlier generations, and they are ready to work hard. They are inclusive and concerned about social justice. And they are increasingly more diverse and less partisan, which means they may eventually insist on more cooperative, more just, and more egalitarian systems.

Social media will likely play a role in that revolution—if it doesn’t sink our kids with anxiety and depression first.

About the Author

Diana Divecha

Diana Divecha, Ph.D. , is a developmental psychologist, an assistant clinical professor at the Yale Child Study Center and Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, and on the advisory board of the Greater Good Science Center. Her blog is developmentalscience.com .

You May Also Enjoy

Why Teens Turn from Parents to Peers

When Going Along with the Crowd May be Good for Teens

Why Won’t Your Teen Talk To You?

When Teens Need Their Friends More Than Their Parents

A Journey into the Teenage Brain

When Kindness Helps Teens (and When It Doesn’t)

- High contrast

- About UNICEF

- Situation of children in Cuba

- Press center

Search UNICEF

Who are the youth of today generation unlimited, we have approached several young people to understand their vision and how they look at the society they live in and make it their own, from each one perspective.

- Available in:

Being young is a synonym of change, progress and future. Being young is, ultimately, facing challenges and creating or recreating a space for future full development. It means turning problems into opportunities and solutions and being the driving force of society.

Today, on the International Youth Day 2020 , we celebrate their visions and their choices, we celebrate “Youth Engagement for Global Action”, a slogan that seeks to highlight the ways young people engage at the local, national and global levels.

Global challenges, like the coronavirus pandemic or climate change, as well as local issues, will have an effect on the future. It is time to see the extent to which this affects the youngest population and to advance solutions. People aged 14 to 29 years represent the largest generation in history.

We reached out to several Cuban youngsters to know about their visions, their roles in society as individuals and part of the population. From their individuality’s point of view, these young people look at the society in which they have to live and how to make it their own. They were posed with two questions, to which they had shared responses. What do you think is the role of young people these days? What are you doing from your position to help young people?

The group of people that goes from 14 to 29 years of age constitute the largest generation in history

Magdany Acosta Gallardo, 18 years old

Young people not only represent the future of our country, we are one of society’s main agents of change and progress. We have a great effect on economic development too. In this stage of our lives, we build many social relationships and develop a personality that defines us as a new generation. What we do when we become adults depends on how we think and act today.

Yaicelín Palma Tejas, 27 years old

Young people only have one role and is the same they have always had. It does not change, because their role is actually changing everything, doing things better than before and injecting them with joy and energy.

Being a journalist, I think my contribution as a champion of young people is to highlight our role as agents of change. As a young citizen, I join every call for autonomy and emancipation, which are challenges for everyone across the globe.

Carlos Alejandro Sánchez, 22 years old

I think young people play a crucial role today no matter the society they live in. We are the ones transforming, consciously or not, our reality, either at the university, at our workplace or in other spaces, and we do it by contributing with a new and updated vision to daily activities. It is our responsibility to make society evolve and stand up for our opinions in the best possible way.

The opportunity of appearing in the media through radio or television every day, in addition to my presence in social networks, which are so popular nowadays, has undeniably helped me to convey messages and show my way of thinking to many more people than usual. Being able to have a positive influence on my generation and on others through my words and actions makes me very proud. For example, hosting a news programme or a show aimed at a young audience is a huge responsibility, but it has allowed me to prove that no matter how young you are, if you want something and are willing to fight for it, you can do it because everything in life is about perseverance and attitude.

Roxana Broche, 25 years old

Young people are the cornerstone of society and represent a generational renewal. This is something that has been said so many times, but the reality is that young people are the ones in charge of building a legacy.

As an actress, I think I can share my life and professional experiences to help and inspire young people, without saturating them with the message. The more one talks about life experiences, the more knowledge one can offer, and I think that is a key element, sharing knowledge so that other people can reuse it.

Anthony Bravo, 20 years old

I am lucky to be a young singer, but you also have a big responsibility when you have a voice; that is why my work at this time has been focused on conveying messages of wellbeing and trying to reproduce behaviours that contribute to personal growth which, in turn, drives a collective creation based on principles that put the fate of society before the fate of individuals. The best way to contribute with something positive to the community is to ensure our own wellbeing; humanity starts with the family.

Through my music, my lyrics, also as a design student and even as an active subject in our country, I’ve taken on as my duty to be a spokesman for ideas that I think are useful. I have put my time and ideas at the service of my generation.

Luis Daniel del Riego Carralero. 16 years old

At our age, our role in the world is to carry out some important functions for our society and eventually become responsible adults, committed to our time. For example, there are young people who are leading and paralyzing the world in a long fight against the lack of action of some to avoid global warming. We have proven that we can offer a better future and that we are willing to fight against all odds to achieve that.

Leslie Alonso Figueroa, 27 years old

Young people have the challenge, without forgetting the past, to fight for a fair world. Phobias and discrimination, male chauvinism, gender violence and racism are some of the challenges to overcome. Young people, from their area of actions, study or workplace must fight together in the ultimate pursuit of societies of rights, with everyone’s help and for everyone’s good.

My job as a communicator and a professor is marked by the challenges of the world’s youth which are our challenges as well. We are all living and coexisting in the same place where forces such as climate change or the new coronavirus make us rethink our strategies and roles to build the future we need.

Harold Naranjo, 20 years old

In my opinion, the role of young people nowadays is to be very productive and, even though there are some who may not find a specific purpose, I’m sure there are many who are able to fulfil their dreams, accompanied by music, dance, performing, communication and other artistic manifestations. All that is what I can see in a place like the Centre A+ Espacios Adolescentes, a programme that provides the opportunity to explore creative capacities and to which I feel lucky to belong!

In my case I had the chance to host radio shows as a way to reflect the different concerns of boys and girls who feel identified with the contents because we address topics of interest and skills that are useful to adolescents, young people and families in general to build together the society we want.

Randol Betancourt Milian. 16 years old

Young people represent an important human resource within society since they act like agents of social change, economic development and progress.

Related topics

More to explore.

20,000 young people from Latin America and the Caribbean call on leaders to take action at the EU-CELAC Summit

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Youth Culture

Introduction, theoretical interventions.

- Life-Cycle Shifts

- Socialization

- Language Use and Identity

- Subcultures

- Linguistic Style and Slang

- Schooling and Education

- Class and Labor

- Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

- Race and Racialization

- Modernity and Globalization

- Migration, Immigration, and Transnationalism

- Activism and Politics

- Violence and the Law

- Commodities

- Visual and Digital Culture

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Archaeology of Childhood

- Digital Anthropology

- Ethnomusicology

- Globalization

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Margaret Mead

- Popular Culture

- Rural Anthropology

- Transnationalism

- Visual Anthropology

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Anthropology of Corruption

- University Museums

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Youth Culture by Shalini Shankar LAST REVIEWED: 28 May 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 28 May 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199766567-0081

The anthropological study of youth began as part of broader inquiries about life cycle, ritual, personhood, and generation (e.g., Margaret Mead’s 1952 classic Coming of Age in Samoa ). Such early studies were generally interested in childhood and adolescence insofar as they offered further insight about a society and adult notions of personhood. “Youth culture,” the term widely used in academic and popular circles today, emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as a post–World War II phenomenon in the United States, Canada, and western Europe. A product of extended secondary schooling, delayed entry into the workforce, and the proliferation of consumer culture, youth culture has taken multiple forms with unique trajectories. Youth culture studies now include children, teenagers, and young people in their twenties, and have placed these individuals at the center of the inquiry, rather than as a liminal period before adulthood. This shift has led to productive understandings of broader anthropological questions of interest—such as race, gender, sexuality, class, globalization, modernity, education, and cultural production—while it also shows how youth action is a site of agency, resistance, identity construction, and social change. Scholarship examining style, adornment, and identity construction has made excellent use of the concept of subculture, while practice-based models have further considered the significance of leisure activity, such as consumption of media, commodities, and digital technologies, in young lives. Several other prominent areas have emerged, including childhood and socialization; psychologically informed approaches to child development; schooling as a lens to dynamics of race, gender, and class formation; and language use, identity, and subjectivity. In the past two decades or so, increased emphasis on the ways in which youth mediate globalization, modernity, migration, and transnationalism have come to the fore, as have studies that foreground issues of activism and politics. The potential of youth to be the initiators of social change, however measured, has been productively explored; so too have the struggles of youth as they cope with racism, poverty, abuse, violence, armed conflict, and other social ills. Methodologically, anthropological work on youth is marked by long-term, rigorous fieldwork using ethnographic and sometimes sociolinguistic approaches, and this in situ fieldwork has led to substantive insights about identity and subjectivity, while also attending to history and political economy. Such research has enabled youth to be regarded as significant contributors to the social worlds in which they operate, as well as how they may be poised to inherit and transform these worlds.

The shift to move youth from the margins to the center of anthropological inquiry has been a slow process. Still somewhat sidelined in the discipline overall, as Hirschfeld 2002 notes, theoretical interventions via review articles that define youth as a field of study help give it more of a presence. For instance, Bucholtz 2002 looks at youth culture with a practice-based approach that also considers language use. Korbin 2003 considers childhoods with violence, and Levine 2007 covers numerous contours and debates of this field. Revising approaches to theorizing youth, such as Durham 2004 , and considering issues of methodology and representation as shown in Best 2007 , keep critical focus on this field of inquiry. Sloan 2007 turns a focus on minority youth in particular (see also Shankar 2011 cited under Linguistic Style and Slang ). Undoing misconceptions about the ways that youth have been assessed in schools is also of major concern, especially to those working on the anthropology of education (see McDermott and Hall 2007 , as well as the citations under Schooling and Education ).

Best, Amy, ed. 2007. Representing youth: Methodological issues in critical youth studies . New York: New York Univ. Press.

A thoughtful collection of essays that examine the benefits and challenges of doing ethnographic fieldwork with children and youth.

Bucholtz, Mary. 2002. Youth and cultural practice. Annual Review of Anthropology 31:525–552.

DOI: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085443

This review article offers in-depth coverage of about three decades of youth culture studies. It establishes the work of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in the 1970s as setting the stage for a practice-based approach, and draws in more recent work from anthropology and related fields.

Durham, Deborah. 2004. Disappearing youth: Youth as a social shifter in Botswana. American Ethnologist 31.4: 589–605.

DOI: 10.1525/ae.2004.31.4.589

Argues that youth should be considered less as a fixed category and more as a set of shifting relationships, and thus as a “shifter” in the indexical sense of indirectly pointing to broader social meanings.

Hirschfeld, Lawrence A. 2002. Why don’t anthropologists like children? American Anthropologist 104.2: 611–627.

DOI: 10.1525/aa.2002.104.2.611

Those working on youth culture may find the title question to ring true, as anthropology has largely marginalized youth as a legitimate field of inquiry and instead considered them primarily as a precursor to adulthood. This article offers reasons for these theoretical and ethnographic gaps and critiques anthropology’s overwhelming emphasis on adults.

Korbin, Jill E. 2003. Children, childhoods, and violence. Annual Review of Anthropology 32:431–446.

DOI: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093345

An overview of numerous types of violence children face and are recruited into, including armed conflict, bullying, abuse, violent rituals, and neglect. Also considers the violent behavior of youth as a form of agency.

Levine, Robert A. 2007. Ethnographic studies of childhood: A historical overview. American Anthropologist 109.2: 247–260.

DOI: 10.1525/aa.2007.109.2.247

A survey of approaches from Mead and Malinowski to twenty-first contemporary ethnography of children, with an emphasis on developmental and psychological perspectives.

McDermott, Ray, and Kathleen D. Hall. 2007. Scientifically debased research on learning, 1854–2006. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 38.1: 9–19.

This intervention documents problematic classroom practices, testing, and teacher training brought about by the No Child Left Behind Act, and calls for less standardized testing and more individual case studies.

Sloan, Kris. 2007. High-stakes accountability, minority youth, and ethnography: Assessing the multiple effects. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 38.1: 24–41.

DOI: 10.1525/aeq.2007.38.1.24

Illustrates the value of ethnography in offering a counterpoint to dominant perspectives on minority youth schooling, including curriculum, pedagogy, and student experiences.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Anthropology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Africa, Anthropology of

- Agriculture

- Animal Cultures

- Animal Ritual

- Animal Sanctuaries

- Anorexia Nervosa

- Anthropocene, The

- Anthropological Activism and Visual Ethnography

- Anthropology and Education

- Anthropology and Theology

- Anthropology of Islam

- Anthropology of Kurdistan

- Anthropology of the Senses

- Anthrozoology

- Antiquity, Ethnography in

- Applied Anthropology

- Archaeobotany

- Archaeological Education

- Archaeology

- Archaeology and Museums

- Archaeology and Political Evolution

- Archaeology and Race

- Archaeology and the Body

- Archaeology, Gender and

- Archaeology, Global

- Archaeology, Historical

- Archaeology, Indigenous

- Archaeology of the Senses

- Art Museums

- Art/Aesthetics

- Autoethnography

- Bakhtin, Mikhail

- Bass, William M.

- Benedict, Ruth

- Binford, Lewis

- Bioarchaeology

- Biocultural Anthropology

- Biological and Physical Anthropology

- Biological Citizenship

- Boas, Franz

- Bone Histology

- Bureaucracy

- Business Anthropology

- Cargo Cults

- Charles Sanders Peirce and Anthropological Theory

- Christianity, Anthropology of

- Citizenship

- Class, Archaeology and

- Clinical Trials

- Cobb, William Montague

- Code-switching and Multilingualism

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Cole, Johnnetta

- Colonialism

- Consumerism

- Crapanzano, Vincent

- Cultural Heritage Presentation and Interpretation

- Cultural Heritage, Race and

- Cultural Materialism

- Cultural Relativism

- Cultural Resource Management

- Culture and Personality

- Culture, Popular

- Curatorship

- Cyber-Archaeology

- Dalit Studies

- Dance Ethnography

- de Heusch, Luc

- Deaccessioning

- Design, Anthropology and

- Disability and Deaf Studies and Anthropology

- Douglas, Mary

- Drake, St. Clair

- Durkheim and the Anthropology of Religion

- Economic Anthropology

- Embodied/Virtual Environments

- Emotion, Anthropology of

- Environmental Anthropology

- Environmental Justice and Indigeneity

- Ethnoarchaeology

- Ethnocentrism

- Ethnographic Documentary Production

- Ethnographic Films from Iran

- Ethnography

- Ethnography Apps and Games

- Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography

- Ethnoscience

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E.

- Evolution, Cultural

- Evolutionary Cognitive Archaeology

- Evolutionary Theory

- Experimental Archaeology

- Federal Indian Law

- Feminist Anthropology

- Film, Ethnographic

- Forensic Anthropology

- Francophonie

- Frazer, Sir James George

- Geertz, Clifford

- Gender and Religion

- GIS and Archaeology

- Global Health

- Gluckman, Max

- Graphic Anthropology

- Haraway, Donna

- Healing and Religion

- Health and Social Stratification

- Health Policy, Anthropology of

- Heritage Language

- House Museums

- Human Adaptability

- Human Evolution

- Human Rights

- Human Rights Films

- Humanistic Anthropology

- Hurston, Zora Neale

- Identity Politics

- India, Masculinity, Identity

- Indigeneity

- Indigenous Boarding School Experiences

- Indigenous Economic Development

- Indigenous Media: Currents of Engagement

- Industrial Archaeology

- Institutions

- Interpretive Anthropology

- Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity

- Laboratories

- Language and Emotion

- Language and Law

- Language and Media

- Language and Race

- Language and Urban Place

- Language Contact and its Sociocultural Contexts, Anthropol...

- Language Ideology

- Language Socialization

- Leakey, Louis

- Legal Anthropology

- Legal Pluralism

- Liberalism, Anthropology of

- Linguistic Relativity

- Linguistics, Historical

- Literary Anthropology

- Local Biologies

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude

- Malinowski, Bronisław

- Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Visual Anthropology

- Maritime Archaeology

- Material Culture

- Materiality

- Mathematical Anthropology

- Matriarchal Studies

- Mead, Margaret

- Media Anthropology

- Medical Anthropology

- Medical Technology and Technique

- Mediterranean

- Mendel, Gregor

- Mental Health and Illness

- Mesoamerican Archaeology

- Mexican Migration to the United States

- Militarism, Anthropology and

- Missionization

- Morgan, Lewis Henry

- Multispecies Ethnography

- Museum Anthropology

- Museum Education

- Museum Studies

- NAGPRA and Repatriation of Native American Human Remains a...

- Narrative in Sociocultural Studies of Language

- Nationalism

- Needham, Rodney

- Neoliberalism

- NGOs, Anthropology of

- Niche Construction

- Northwest Coast, The

- Oceania, Archaeology of

- Paleolithic Art

- Paleontology

- Performance Studies

- Performativity

- Perspectivism

- Philosophy of Museums

- Plantations

- Political Anthropology

- Postprocessual Archaeology

- Postsocialism

- Poverty, Culture of

- Primatology

- Primitivism and Race in Ethnographic Film: A Decolonial Re...

- Processual Archaeology

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Anthropology

- Public Archaeology

- Public Sociocultural Anthropologies

- Religion and Post-Socialism

- Religious Conversion

- Repatriation

- Reproductive and Maternal Health in Anthropology

- Reproductive Technologies

- Rhetoric Culture Theory

- Sahlins, Marshall

- Sapir, Edward

- Scandinavia

- Science Studies

- Secularization

- Settler Colonialism

- Sex Estimation

- Sign Language

- Skeletal Age Estimation

- Social Anthropology (British Tradition)

- Social Movements

- Society for Visual Anthropology, History of

- Socio-Cultural Approaches to the Anthropology of Reproduct...

- Sociolinguistics

- Sound Ethnography

- Space and Place

- Stable Isotopes

- Stan Brakhage and Ethnographic Praxis

- Structuralism

- Studying Up

- Sub-Saharan Africa, Democracy in

- Surrealism and Anthropology

- Technological Organization

- Trans Studies in Anthroplogy

- Tree-Ring Dating

- Turner, Edith L. B.

- Turner, Victor

- Urban Anthropology

- Virtual Ethnography

- Whorfian Hypothesis

- Willey, Gordon

- Wolf, Eric R.

- Writing Culture

- Youth Culture

- Zora Neale Hurston and Visual Anthropology

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 Introduction: A Kaleidoscope of Youth Cultures

The author, editor, or co-editor of more than twenty books, James Marten taught at Marquette University for thirty-six years, where he is now Professor of History Emeritus. He was a founder of the Society for the History of Children and Youth (SHCY) and served as the Society’s president from 2013 until 2015. He is a former editor of the Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth.

- Published: 23 February 2023

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter provides an overview of youth culture, which represents multiple communities and values. It begins by considering the difference on how historians and social scientists examine youth culture. While social scientists are consciously trying to find solutions to perceived problems, historians are more interested in explaining why particular aspects of youth culture are perceived as problems. The chapter then explores how histories of youth culture can be divided into several categories of inquiry: juvenile delinquency, child labor, child soldiers, youth activism, girlhood, and popular culture. It also outlines the subsequent chapters, which, taken together, demonstrate that youth culture has developed out of efforts by adults to shape coming of age and the efforts of youth themselves to find their own paths. Throughout, the authors distinguish between the histories of youth and the histories of youth culture.

The phrase “youth culture” brings together two of the easiest and most difficult words to define. We all know what a “youth” is, and we all have at least a sense of what “culture” is, even though it is a fungible kind of word, related to literature, performing arts, and music, of course—but also to ethnicity, belief systems, and socioeconomic class. But the challenges and opportunities that scholars face in writing about youth and culture come from the fact that these words are highly elastic and relative; used together, they create an almost impossible-to-define concept. Yet youth is one of the most fascinating, rewarding, frightening, and fraught passages in a person’s life, and the way young people experience and describe that passage—and the way parents and society try to narrow the possibilities of that passage—makes up much of what we know about youth culture.

In his 1985 sociological overview, Comparative Youth Culture , Mike Brake writes that sixty or seventy years of scholarship on youth cultures had coalesced around the theme “that if the young are not socialized into conventional political, ethical and moral outlooks, if they are not programmed into regular work habits and labour discipline, then society as it is today cannot continue.” These perennial, age-old fears lend urgency to the need to understand youth culture, and they provide hints as to why social scientists—in the fields that developed late in the nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries, such as psychology, sociology, and social work—studied youth culture for decades before historians took it seriously. Brake goes on to write,

What is central to any examination of youth culture is that it is not some vague structural monolith appealing to those roughly under thirty, but is a complex kaleidoscope of several subcultures, or different age groups, yet distinctly related to the class position of those in them.

The historians who contributed to this handbook might not use precisely the same language, but they would certainly agree with the notion that there is not one “youth culture.” And, although it may stretch the metaphor to say so, youth culture is similar to a kaleidoscope in that it represents multiple communities and values, and that it can be seen differently depending on the perspective from which it is being viewed. 1

Societies have often focused on youth culture as a series of problems: delinquency, illicit sex, loud music, protest, and countless other forms of behavior often viewed as threats to social order that demand solutions. This reductionism is reflected in the titles found on the shelves of the Library of Congress’s HQ subsection in any academic library: Fitting In, Standing Out ; Youth Crisis ; My Son Is an Alien ; Search for Identity ; All Grown Up and No Place to Go ; Lost Youth in the Global City ; Teenage Wasteland ; Growing Up Absurd ; The Vanishing Adolescent ; Strangers in the House ; Pathways through Adolescence ; Not Much, Just Chillin’ ; Re/Constructing “The Adolescent” ; Goth’s Dark Empire ; Super Girls, Gangstas, Freeters, and Xenomaniacs .

Although the specifics have varied, the general concerns have not much changed since the early twentieth century. In a recent collaboration with Scientific American , the journal Nature devoted much of a 2018 issue to “Coming of Age: The Science of Adolescence.” Its introduction states that

It’s widely accepted that adolescents are misunderstood. Less well known is how far we still have to go to understand adolescence itself. One problem is that it is hard to characterize: the concept of puberty does not capture the decade or more of transformative physical, neural, cognitive and socio-emotional growth that a young person goes through. Another is that science, medicine, and policy have often focused on childhood and adulthood as the most important phases of human development, glossing over the years in between.

The rest of the issue examines contemporary health and social issues: brain development, generational relationships, use of media, alcohol, obesity, and antisocial behavior. 2

In some ways historians have followed the lead of psychologists, political scientists, social workers, activists, and policymakers in exploring youth culture through the lenses of pathologies, failures of society, or attempts to solve perceived problems. Yet historians by their very nature do not see themselves as solvers of problems; rather, they step back to study the actions and desires that seem to feed those problems along with the institutions, organizations, and laws intended to control them. In the introduction to their excellent anthology, Joe Austin and Michael Nevin Willard write that “the practices of young people become occasions for moral panic … resulting in calls for social renewal and action.” Drug use, sex, crime, sexuality and teen pregnancy, and shortcomings in our educational systems have all taken their turns, some several times—as sources of community anxiety and increased supervision and regulation. The more than two dozen essays that Austin and Willard assembled tend to focus more on youth agency than on attempts to control it, highlighting music, art, dress, cars, zines, and other forms of self-expression. 3

The difference, perhaps, between historians and social scientists examining youth culture is that, while the latter are consciously trying to find solutions to perceived problems (and, of course, there are problems that need to be solved), the former are more interested in explaining why particular aspects of youth culture are perceived as problems. Historians seek to understand the motivations behind the youth forming those cultures and the adults expressing their anger, fear, or dismay.

In Paula Fass’s Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society , Austin offers a useful overview of the historiography and history of youth culture. The first line of his entry is instructive: “Culture is among the most complicated words in the English language.” He goes on: “It refers to the processes by which … traditions and rituals” and “frameworks for understanding experience … characteristically shared by a group of people” are “maintained and transformed across time.” Some, he points out, are “distinctive from those of their parents and the other adults in their community.” Another useful point he makes is that, even if the institutions and concrete evidence of culture do not appear in the historical record, it does not mean that youth culture did not exist. For him—and for many of the authors in this handbook— behavior is as much a product and signifier of youth culture as are institutions, organizations, and movements. 4

Defining a Historical Youth Culture

The essays in this volume explore the development and diversification of youth culture around the world from the medieval period to the present. Although global in scope, this is not a comprehensive history of youth culture. It does , however, address a comprehensive set of issues related to youth culture. Throughout, authors distinguish between the histories of youth (in other words, the experiences of youth and the conditions in which they live) and the histories of youth culture (the cultural and emotional products of youths’ interaction with one another and with their larger community or communities). For instance, an essay on youth and work provides an overview of the nature of the work experience, but it emphasizes the ways in which youth responded to work, and the ways in which greater autonomy, access to spending money, and relationships to other youth contributed to the formation of youth culture.

Taken together, the chapters demonstrate that youth culture has developed out of efforts by adults to shape coming of age and the efforts of youth themselves to find their own paths. It encompasses the aspects of “culture” that we are familiar with—art, literature, drama—as well as the less tangible but perhaps more important organizations, associations, customs, and styles that draw youth together and separate them from others. The ways in which youth spend their leisure time has figured prominently in the ways that parents and policymakers have worried about youth culture, even as leisure activities provided structure to that culture, and a significant segment of youth culture has also been almost inseparable from popular culture—music, movies, and television, especially—since at least the 1950s and 1960s. Normal biological, emotional, and intellectual development naturally intersect with youth culture, especially in the contexts of emerging sexuality, mental health issues, and the relationship of youth to authority figures and institutions.

Studying the history of youth culture in any society provides a crucial lens for understanding that society’s value systems, educational and economic structures, gender relations, and virtually every facet of cultural expression and human development. This is particularly important during the modern period, which saw the development of economies that required less labor from adolescents while at the same time offering—and requiring, in most places—more opportunities for formal education, both of which encouraged the development of a separate youth culture. Although these conditions emerged first in the United States and then in Western Europe, they gradually expanded to most of the world, although specific forms of youth culture varied greatly by place, ethnicity, and religion, among other factors. Moreover, societies around the world have periodically experienced crises in the behavior of adolescents (the “boy problem” in the United States in the early twentieth century, for instance).

The Search for a Definition of Youth Culture

Humans have for many centuries recognized “youth” as a separate phase of life. It appeared in many early demarcations of the “stages of man,” although the exact ages at which it began and ended could vary from the mid-teens to late twenties. But the important point is that virtually all societies recognized some distinct facets of youth, from legal responsibility to the ability to articulate thoughts and feelings to being physically ready and mature enough to consider courtship. As a recent brief survey of adolescence says, one definition is disarmingly simple: the “period of transition between life as a child, and life as an adult.” The author goes on to state that puberty has normally been a fairly safe starting point for thinking about adolescence, but a paragraph later he writes that although the teenage years are generally considered identical to adolescence, some researchers consider ages ten to eighteen as more accurate, and the World Health Organization identifies it as ten to nineteen. 5