Native American Poverty

An endless cycle.

At the time of colonization, First Nations tribes were forced onto remote reservations lacking in natural resources or fertile soil. Additionally, hundreds of years of government policies have left reservations with limited economic opportunities. As a result, First People have the highest poverty rate (one-in-four) and among the lowest labor force rate ( 61.1% ) of any major racial group in the United States. Of the top 100 poorest counties in the United States, four of the top five and ten of the top 20 are on reservations. Most tribal members cope with food insecurity and its associated health problems, unemployment rates as high as 85%, and major housing shortages.

The Native community faces the highest poverty rate (26%) and the lowest labor force rate (61.1%) of any major racial group in the United States.

First people face the lowest employment rate of any racial or ethnic group in the us, (up to 85%)., only one in three native american men have full-time, year-round employment in the poorest communities., as of 2011, there were over 120,000 tribal homes lacking access to basic water sanitation services., approximately 22% of our country’s 5.2 million natives live on reservations, in conditions “comparable to third world”., twenty-six percent of single-race indigenous people are living in poverty, the highest rate of any race group., native american food insecurity.

The majority of Native communities today struggle with systemic problems related to lack of access to healthy food. One-in-four Native Americans experience food insecurity due to scarce access to food and employment, compared to just one-in-eight in the general American population. Grocery stores are few and far between, leaving tribes to largely depend on outside sources for food. Additionally, poverty rates are so high that few families can afford healthy food options and therefore turn to low price, low nutrition alternatives. This results in many health issues, including diabetes, heart disease, obesity and related conditions.

NATIVE AMERICAN UNEMPLOYMENT

Typically, reservations are geographically isolated — located miles away from major metropolitan areas — with limited access to resources and capital. Since there are very few employment opportunities on tribal lands (mostly tribal and federal government jobs), heads of household are forced to leave the reservation to seek work. In the poorest Native counties, only about one out of three men have full-time, year-round employment.

For those who do have jobs, earnings can be well below poverty wages — the average household income for working Native Americans is $35,000 , compared to $50,000 of the general population. As a result, many households depend on federal funding to make ends meet — welfare, disability, social security and additional government services.

NATIVE AMERICAN HOUSING CRISIS

Tribal economies require affordable housing and infrastructure. However, First People face some of the worst substandard and overcrowded housing conditions in the United States. Forty percent of housing on reservations is considered substandard compared to only 6% throughout the rest of the country. Thirty percent of native housing is overcrowded. Less than 50% of native homes are connected to a public sewer system and of those, 16% lack indoor plumbing . Additionally, 23% of Native households pay 30% or more of their household income to housing alone.

At the core of this housing issue, the current reservation real estate market barely exists. Centuries of treaties and federal policies established reservations as lands held in trust for Native people by the federal government. Until the 1990s, mortgages weren’t effective on reservations. Many still can’t get a mortgage due to bad credit or lack of funds for a down payment. In that regard, the housing market is similar to the food or employment markets — it barely exists.

OUR SOLUTIONS

The level of need in the Indigenous world is overwhelming. The Red Road aims to raise our people up and give them the tools needed to help themselves.

SPEAKING ENGAGEMENTS

Baskets of hope, community gardens, tribally-owned business.

- IPR Intranet

INSTITUTE FOR POLICY RESEARCH

What drives native american poverty.

Sociologist Beth Redbird’s research points to job loss, not education, as a key driver

Get all our news

Subscribe to newsletter

The payoff to education is not nearly as high as the payoff to jobs. The idea that we could reduce poverty for the Indian-only population by nearly 20% with employment is astounding.”

Beth Redbird Assistant Professor of Sociology, IPR Fellow, and CNAIR Fellow

Across the United States, 1 in 3 Native Americans are living in poverty, with a median income of $23,000 a year. These numbers from the American Community Survey highlight the stark income inequality the nation’s first peoples face.

“Poverty has been, for over a century, a huge part of the conversation about Indigenous well-being, but to a large extent we don’t even know what drives Native [American] poverty, what causes it, and where it comes from,” said sociologist Beth Redbird . “And without those answers, it’s awfully hard to know how we can fix it.”

She presented her research on what has been driving this poverty rate among Native Americans at a January 29 seminar. It was co-sponsored by the Center for Native American and Indigenous Research (CNAIR) and Institute for Policy Research (IPR). Redbird is both an IPR and a CNAIR fellow.

Changing Demographics

Redbird pointed out several changes Native Americans have experienced since 1980: Over that time, more Native American tribal nations have invested heavily in education and sending their children to schools. As a result, more Native Americans have gone to high school and college than ever before—nearly 1 in 5 reservations offer an elementary school and high school education. Many have moved back to rural parts of the country, with nearly 80% living in a rural area.

Despite the substantial investment and increase in education in Native American communities, the employment rate among Native Americans has declined and wage growth has decreased in that same time period. Even considering that poverty tends to be higher in rural parts of the country, the poverty gap between Native Americans living in rural and urban areas is larger than the white rural and urban gap. This means that poverty is not driven by the fact that Native Americans are more likely to live in rural areas.

Overall changes in the U.S. economy have especially impacted Native peoples, Redbird notes, including the loss of a large number of jobs in construction and manufacturing, the decline of the minimum wage, and the increase in unstable employment.

“One of the things that we also know about jobs is there’s been this declining relationship between working and a job’s ability to help you get out of poverty,” Redbird explained.

Redbird calculated what would happen if Native Americans had the same employment rates, occupations, levels of education, lived in the same geographic location, and were a part of the same types of households as white Americans. Her results showed that employment was the most significant factor in driving poverty.

“The payoff to education is not nearly as high as the payoff to jobs,” she said. “The idea that we could reduce poverty for the Indian-only population by nearly 20% with employment is astounding.”

Creating Jobs and Customizing Policy

She also studied how tribes are working to address their own economic development through two common job initiatives—tribal gaming and energy—to measure if they were successful. Using data from the Census, Redbird finds that even when tribes started gaming establishments or energy projects, few lasting new jobs were created and poverty rates didn’t improve. In 2015, casinos created an average of 25 jobs and energy projects created 12, which barely had an effect on reservations with more than 2,000 residents on average.

“Big projects bring hope to reservations and frequently a lot of debt,” Redbird said, noting their tendency to create few, mostly low-paying, jobs.

She suggests that to generate more jobs, tribes should invest in a variety of job initiatives to diversify economic opportunities, rather than putting all of their capital into one project they hope will reform the tribe. Policy solutions, Redbird believes, should also come from both the federal and tribal governments.

“Federal policy has the ability to be applied broadly,” Redbird said, if you can identify a consistent problem across tribes. “[But] Indians don’t have the highest trust in federal policy. And one of the things that self-determination has really become about is the ability to say, ‘We want to do what’s right here.’”

Because economic well-being at the local level might also look different for a tribe in Wyoming versus one in California and lead to a variety of outcomes, she says it is helpful to have federal and tribal policies that work together. Redbird hopes future research on Native American poverty will consider the best ways to guide tribal policy development.

“The ability to take policy prescriptions and then make them your own, I think has a better chance of success in addressing some of these, than the idea of larger policy,” she argued.

While the high poverty rate among Native Americans is not a new issue, Redbird does not think it is a hopeless one.

“The ability to have enough money so that we at least think that you can meet minimum standards of living— feed a family, [have] clothes, childcare, [and] healthcare—those kinds of things are a standard that we’d at least like to see we’re capable in this country of providing to everybody,” Redbird said.

Beth Redbird is assistant professor of sociology, an IPR fellow, and a CNAIR fellow.

Photo credit: Patricia Reese.

Published: February 24, 2020.

Related Research Stories

Sociologist Alondra Nelson to Deliver Distinguished Policy Lecture at Northwestern

Reckoning with the Impossible

Laurel Harbridge-Yong to Become IPR’s Ninth Associate Director

Poverty and exclusion among Indigenous Peoples: The global evidence

Gillette hall, ariel gandolfo.

Professor in the Practice and Director of Teaching in the Global Human Development Program, Georgetown University

MA Candidate in Global Human Development, Georgetown University

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

One-in-four Native Americans and Alaska Natives are living in poverty

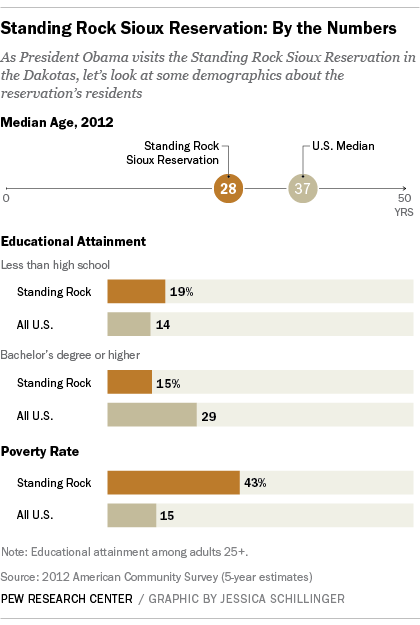

On his visit to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota today, President Obama is using his first stop at a Native American reservation while in office to highlight the challenges Native Americans face. In an op-ed published in Indian Country Today , Obama called the poverty and high school dropout rates among Native Americans “a moral call to action.”

The poverty rate at Standing Rock Reservation is 43.2%, nearly triple the national average, according to Census Bureau data. The reservation, which straddles North Dakota and South Dakota, has a population of 8,956, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs .

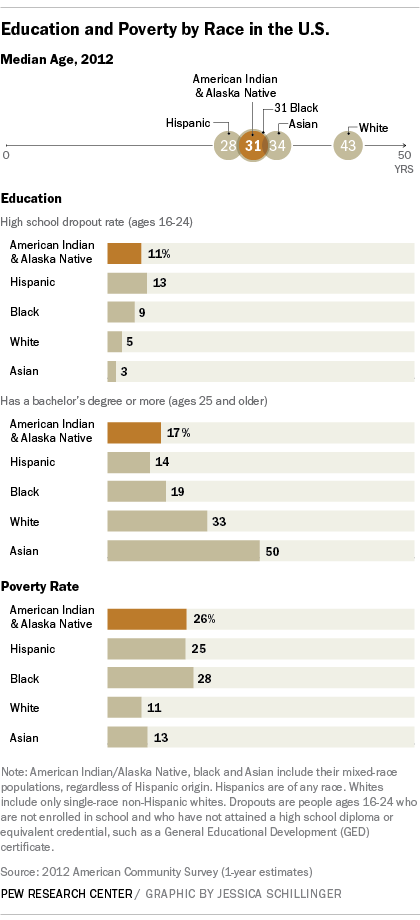

Native Americans have a higher poverty and unemployment rate when compared with the national average, but the rates are comparable to those of blacks and Hispanics. About one-in-four American Indians and Alaska Natives were living in poverty in 2012. Among those who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native as their only race, the poverty rate was 29.1% in 2012.

Some 5.2 million people (1.7% of the total U.S. population) identify as Native American or Alaska Native, with 44% identifying as at least one other race, according to 2010 Census Bureau data , the most recent data available. And census officials have said that the number of people who self-identify as such has been growing, for reasons they don’t fully understand .

There were 170,110 people nationwide who identified as Sioux in the 2010 census. The largest tribal group, Cherokee, has 819,105 people. Of those who identify as Native American or Alaska Native as their only race, one-in-three (33%) live on reservations or tribal lands. Among all American Indians and Alaska Natives, about one-in-five (22%) live on reservations or tribal lands.

- Economic Inequality

- More Racial & Ethnic Groups

- Race & Ethnicity

Jens Manuel Krogstad is a senior writer and editor at Pew Research Center .

1 in 10: Redefining the Asian American Dream (Short Film)

The hardships and dreams of asian americans living in poverty, a booming u.s. stock market doesn’t benefit all racial and ethnic groups equally, black americans’ views on success in the u.s., wealth surged in the pandemic, but debt endures for poorer black and hispanic families, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Poverty and Health Disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native Children: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects

This report explores the current state of knowledge regarding inequalities and their effect on American Indian and Alaska Native children, underscoring gaps in our current knowledge and the opportunities for early intervention to begin to address persistent challenges in young American Indian and Alaska Native children’s development. This overview documents demographic, social, health, and health care disparities as they affect American Indian and Alaska Native children, the persistent cultural strengths that must form the basis for any conscientious intervention effort, and the exciting possibilities for early childhood interventions.

Introduction

Disparities in health have existed among American Indian and Alaska Native populations since the time of first contact 500 years ago, 1 and they continue to occur across a broad spectrum of disease categories and for all ages. 2 Historically, our understanding of health disparities within the American Indian and Alaska Native population as a whole has been limited because of the lack of adequate data; our understanding of the health disparities experienced by American Indian and Alaska Native children in particular has been especially so. 3 , 4 The literature on American Indian and Alaska Native children’s health is relatively small, oftentimes dated, and characterized by descriptive studies of small regional samples, 4 – 6 partly because of difficulties in sampling the small, isolated, diverse, and culturally distinct groups that form the American Indian and Alaska Native population. 7 – 9 The literature on American Indian and Alaska Native children’s health has, however, shown some promising advances with the appearance of several studies based on recent data from both national and tribally specific samples; we highlight here some of the emerging new directions for addressing the most persistent health disparities that affect American Indian and Alaska Native children.

We focus first on the challenges faced by American Indian and Alaska Native populations and children, highlighting demographic, social, health, and health care disparities. Second, we discuss the cultural strengths upon which American Indian and Alaska Native communities and children can draw in the face of such challenges, focusing on the role of extended family and child-rearing beliefs that can and should play an important role in intervention efforts. 10 Third, we close by discussing the possibilities for early childhood intervention in light of both the challenges and the cultural strengths of American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Challenges in American Indian and Alaska Native Children’s Development

Demographic challenges: poverty, education, and employment.

American Indian and Alaska Native people today represent roughly 1.5% of the total U.S. population. 11 Relative to the general U.S. population, it is a young and growing population, with one-third of people younger than 18 years 12 and fertility rates that exceed those of other groups. 13 More than one-quarter of the American Indian and Alaska Native population is living in poverty, a rate that is more than double that of the general population and one that is even greater for certain tribal groups (e.g., approaching 40%). 12 American Indian and Alaska Native children and families are even more likely to live in poverty. 14 U.S. Census Bureau statistics reveal that 27% of American Indian and Alaska Native families with children live in poverty, whereas 32% of those with children younger than 5 years do—rates that are again more than double those of the general population and again are even higher in certain tribal communities (e.g., 66%). 15 , 16 Discrepancies in education and employment are also found. Overall, there are fewer individuals within the American Indian and Alaska Native population who possess a high school diploma or GED (71% versus 80%) or a bachelor’s degree (11.5% versus 24.4%). 12 Such educational discrepancies appear early, with American Indian and Alaska Native children’s math and reading skills falling progressively behind those of their white peers as early as kindergarten to fourth grade, as well as other challenges persisting throughout the school years, including higher dropout rates and grade retention. 17 American Indian and Alaska Native people have lower labor force participation rates than those of the general population, 12 whereas family unemployment rates range from 14.4% overall to as high as 35% in some reservation communities. 15 The poverty and unemployment observed in American Indian and Alaska Native communities is related to broader economic development challenges in American Indian and Alaska Native communities, including geographic isolation and the availability of largely low-wage jobs. 18

Social Challenges: Violence, Trauma, and Loss in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities

American Indian and Alaska Natives are especially likely to experience a range of violent and traumatic events involving serious injury or threat of injury to self or to witness such threat or injury to others. 19 Of all races, they have the highest per-capita rate of violent victimization, whereas children between the ages of 12 and 19, in particular, are more likely than their non-Native peers to be the victims of both serious violent crime and simple assault. 20 This situation has been associated with many other health disparities. 21 In a national survey of more than 13,000 youth in grades 7–12 drawn from 200 reservation-based schools, a factor analysis of 30 risk behaviors was conducted. Among the seven risk factors derived from this analysis was one including violence and gang involvement. This factor was correlated with other risk behaviors, such as alcohol and drug use; suicide attempts; and vandalism, stealing, and truancy. 22

American Indian and Alaska Native children experience and are exposed to other kinds of traumatic events in their communities. National injury mortality data show that American Indian and Alaska Native children are more likely to be killed in a motor vehicle accident, to be hit by a car, to commit suicide, or to drown than either their African American or white peers. 23 The implication of these data is twofold. First, the children who are killed in these types of situations represent only a small portion of those who experience these events, because many survive. It is thus likely that the number of American Indian and Alaska Native children surviving these sorts of events is high and that surviving traumatic events, such as car accidents, is a significant source of trauma in their lives. Indeed, national data indicate that injury risk behaviors among American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents are high and exceed those of their geographic peers, 24 with significant percentages of adolescents reporting never wearing seat belts (44%), drinking and driving (37.9%), and riding with a driver who was drinking (21.8%). Second, American Indian and Alaska Native children witness high rates of trauma among their family and friends and thus are exposed to trauma not only as direct victims but also as bystanders. Because of the interconnectedness of reservation communities, 25 the serious injury or traumatic loss of one individual often has an effect far beyond that individual’s immediate family and friends.

Within this large network, American Indian and Alaska Native children are also exposed to repeated loss because of the extremely high rate of early, unexpected, and traumatic deaths due to injuries, accidents, suicide, homicide, and firearms—all of which exceed the U.S. all-races rate by at least two times—and due to alcoholism, which exceeds the U.S. all-races rate by seven times. 26 , 27 Among adults, exposure to such events is high, ranging from 19% to 46%, depending on the type of event. 28 The extent of traumatic loss among American Indian and Alaska Native children is not exactly known; however, data from two research studies provide some idea. In a small sample of 109 8th- to 11th-grade students in a Northern Plains reservation community, 28% reported the sudden loss of someone close or witnessing a death 29 ; in a larger national sample, 24 11% of adolescents reported knowing someone who had committed suicide.

Domestic violence exposure and child abuse and neglect are other sources of violence and trauma in American Indian and Alaska Native children’s lives. 30 Data from several studies reveal that American Indian and Alaska Native women are more likely than women from other ethnic groups to report a history of domestic violence victimization. 31 – 35 The extent to which American Indian and Alaska Native children are exposed to domestic violence in their homes is not well documented, but research suggests that exposure is high relative to that of their non-Native peers. 36 – 38 Better data are available for child abuse and neglect and indicate that 21.7 of 1000 American Indian and Alaska Native children were the victims of child maltreatment in 2002, compared with 20.2 of 1000 African American children and 10.7 of 1000 white children. 39 American Indian and Alaska Native children from Alaska and South Dakota in particular evidenced the highest rates of maltreatment (99.9/1000 and 61.2/1000, respectively). On the basis of retrospective accounts of American Indian and Alaska Native adults, the true rate of child maltreatment is likely far greater. 31 , 32 , 40 , 41 There are both immediate and long-term effects of child maltreatment within the American Indian and Alaska Native population, including higher rates of mental disorders, substance abuse, suicidal behavior, and behavioral and relationship problems among maltreated individuals. 31 , 32 , 37 , 38 , 41 – 46

Physical Health Disparities in the American Indian and Alaska Native Population

Based on existing data, there can be little doubt that the American Indian and Alaska Native population as a whole is confronted with ongoing disparities in health. 47 – 55 According to the Indian Health Service (IHS), the federal agency that provides medical care to roughly 1.6 million American Indian and Alaska Native people, the age-adjusted death rate for adults exceeds that of the general population by almost 40%, with deaths due to diabetes, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, and accidents occurring at least three times the national rate, and deaths due to tuberculosis, pneumonia and influenza, suicide, homicide, and heart disease also exceeding those of the general population. 27 Although studies of urban American Indian and Alaska Native health are limited, 56 those that do exist suggest similar health-related disparities, including higher rates of and deaths due to accidents, liver disease and cirrhosis, diabetes, alcohol problems, and tuberculosis compared to the general population from the same area. 14 , 57

Across the developmental spectrum American Indian and Alaska Native children also experience physical health–related disparities relative to their non-Native peers. National Center for Health Statistics 58 data document rates of inadequate prenatal care and post-neonatal death among American Indian and Alaska Native infants that were two to three times those of white infants and even higher, among rural American Indian and Alaska Native infants. IHS data 27 showed a similar pattern, with an American Indian and Alaska Native postneonatal death rate roughly twice that of both the U.S. all-races and white rates (4.8 deaths per 1000 live births versus 2.7 and 2.2, respectively), and accounted for by the increased number of American Indian and Alaska Native deaths due to sudden infant death syndrome (1.8 versus 0.8 deaths/1000 live births), pneumonia and influenza (0.4 versus 0.1), accidents (0.4 versus 0.1), and homicide (0.2 versus 0.1). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are also greater among American Indian and Alaska Native children occurring in 1.7–10.6 per 1000 births, 59 indicating as much as a fivefold difference compared with national rates. 26 , 27 , 60

Health disparities become more apparent beyond infancy. American Indian and Alaska Native children’s deaths between the ages of 1 and 4 years occur at nearly three times the rate of children in the general population (0.9 versus 0.35 per 1000 lives); with preventable deaths due to accidents (0.47 per 1000 children; 52% of all deaths) and homicide (0.065 per 1000 children; 8% of all deaths) being the leading causes of death, and exceeding the all-races rates by 3.3 and 2.2 times, respectively. 26 , 27 The pattern of disparities for injury-related mortality is especially striking beyond early childhood. 21 , 61 , 62 In a study of Native and non-Native youth in Canada, the overall all-cause relative risk (RR) for injury-related death among Native children was 4.6 times that of non-Native children aged 0–19 years, peaking between ages 0 and 4 for boys and girls and again between 10 and 14 for girls and 15 and 19 for boys. Though injury mortality rates were higher for Native children across all injury categories, they were largest for pedestrian injuries (RR =17.0), poisoning (RR =15.4), homicide by piercing (RR =15.4), and suicide by hanging (RR =13.5). Similar national data from the United States indicated that American Indian and Alaska Native youth had an overall two times greater injury-related death rate than the U.S. average. Relative to white youth, they experienced greater injury-related death in all injury categories and exceeded both black and white children for injury-related deaths due to motor vehicle accidents, pedestrian events, and suicide. These data highlighted the involvement of alcohol in all injury-related death among American Indian and Alaska Native youth.

Additional physical health disparities emerge for American Indian and Alaska Native children beginning in early childhood and continuing throughout development. Of particular note are childhood obesity and overweight and childhood dental caries. 63 , 64 In one of the largest studies to assess childhood obesity among American Indian and Alaska Native children, 39% were defined as overweight or obese—defined as a body mass index (measured in kilograms per square meter of body surface area) above the 85th percentile. 65 In national studies, American Indian and Alaska Native children are twice as likely to be overweight and three times as likely to be obese, 64 with rates of both growing by 4% since the mid-1990s. 66 The disparities for childhood dental caries are equally striking. According to recent IHS data, 79% of American Indian and Alaska Native preschool children had caries experience, whereas 68% had untreated dental decay—a prevalence of more than three times that of their non-Native peers. 67

Mental Health Disparities in the American Indian and Alaska Native Population

Systematic epidemiological evidence of mental health problems among American Indian and Alaska Native adults has only recently become available. 8 , 51 , 54 , 68 , 69 In community samples from two tribal groups (Southwest [SW] and Northern Plains [NP]), the prevalence of nine psychiatric disorders was assessed among 3086 individuals between the ages of 15 and 54 years by using a culturally modified version of the interview used in the National Comorbidity Survey, 70 allowing for explicit comparisons with national rates. Among American Indian and Alaska Native women, the highest lifetime rates of disorder were posttraumatic stress disorder (SW, 22.5%; NP, 20.2%), alcohol dependence (SW, 8.7%; NP, 20.2%), and major depression (SW, 14.3%; NP, 10.3%). The highest lifetime rates of disorder for American Indian and Alaska Native men were alcohol dependence (SW, 31.1%; NP, 30.5%), posttraumatic stress disorder (SW, 12.8%; NP, 11.5%), and alcohol abuse (SW, 11.2%; NP, 12.8%). Compared with national data, 70 rates of posttraumatic stress disorder were significantly higher for men and women from both tribal backgrounds, ranging from two to three times the national rate. Alcohol dependence was also significantly higher among men (50% higher) and NP women (100% higher). Other data highlight the severity and impact of such mental health problems; death due to suicide among American Indian and Alaska Natives is 72% higher than that in the general population, whereas death due to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and other alcohol-related causes (e.g., accidents) is seven times the national rate. 27

American Indian and Alaska Native youth also experience higher rates of mental health disorders relative to their peers. 71 One study assessed the 3-month prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders among children aged 9–13 years. 36 Overall, conduct and oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety disorders, and separation anxiety were the most common diagnoses, occurring at similar rates for American Indian and Alaska Native and white children from the same area, whereas substance use disorders were significantly more likely among the American Indian and Alaska Native children. In another study, higher rates for more disorders were found among older American Indian and Alaska Native children (aged 14–16 years) than the published rates of disorder for non-Native children of the same age. 72 Substance use disorders were the most common, with 18.3% of American Indian and Alaska Native children meeting criteria for either abuse or dependence within the last 6 months. Disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and other substance use disorders were diagnosed in 13.8%, 5.5%, 4.6%, and 3.9% of children, respectively. In comparison, rates of attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, substance abuse and dependence, and conduct and oppositional defiant disorder were elevated relative to published rates for non-Native children.

As with American Indian and Alaska Native adults, additional data highlight the effect and severity of the mental health problems occurring among youth. According to multiple sources, 61 , 62 , 73 the suicide rate is three to six times higher among American Indian and Alaska Native than among their non-Native peers and indeed represents one of the greatest health disparities faced by young American Indian and Alaska Natives.

Challenges in Intervention and Services

The physical and mental health disparities faced by American Indian and Alaska Native populations can in part be accounted for by the serious lack of funding for health care within the IHS system and by the numbers of American Indian and Alaska Native people not served by IHS who are without any other form of health insurance or benefit. 49 , 50 , 75 A U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report documented that the IHS is so severely underfunded that it spends just $1914 per patient per year compared with twice that amount ($3803) that is spent on a federal prisoner in a year. 76 Amazingly, this finding is little departure from the state of health care more than a century ago. As Jones 1 accounts, in 1890 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs calculated that based on government salaries paid to physicians in the Army, Navy, and Indian health, “the government valued people [at] $21.91 per soldier, $48.10 per sailor, and $1.25 per Indian” (p. 2128). The lack of funding is especially dire for mental health services. According to providers in 10 of the 12 IHS service areas, mental health was identified as the number-one health problem confronting American Indian and Alaska Native communities today; along with social problems, it was estimated to contribute to more than one-third of the demands for services. 77 Despite such a demand, only 7% of an already limited IHS budget is allocated for mental health and substance abuse services. 48 The effect of this underfunding on the availability of mental health services is dramatic; by one estimate there were only two psychiatrists and four psychologists per 100,000 people served by the IHS—one-seventh the number of psychiatrists and one-sixth the number of psychologists available to the general population. 48

Given the critical shortfall in physical or mental health services available to the larger American Indian and Alaska Native population, it is unfortunately not surprising that services targeting the physical, social, or emotional needs of American Indian and Alaska Native children are even more severely limited. 78 , 79 In our review of the literature, we found no published studies of interventions targeting young American Indian and Alaska Native children; for older American Indian and Alaska Native children, we found only a few—most of which focused on the lack of services for American Indian and Alaska Native children or were largely descriptive and provided few data on the effectiveness of the services. 78 , 80 – 82 The dearth of literature does not mean that services are not being provided in American Indian and Alaska Native communities, but it does mean that little is known outside those specific communities about what works and for whom. The lack of such studies indicates a significant gap in the research literature and is a disservice to American Indian and Alaska Native children and communities that needs to be addressed.

Cultural Strengths Supporting American Indian and Alaska Native Children’s Development

American Indian and Alaska Native communities today live with a legacy of cultural trauma as a result of centuries of dispossession at the hands of the U.S. government and its policies and practices intentionally designed to break apart culture, communities, family, and identity. 83 – 89 Despite this legacy and its arguable effects on life in American Indian and Alaska Native communities today, one need only hear a conversation in Towa between a Pueblo grandmother and her grandchild, visit a summer sheep camp among the Navajo, or attend a Lakota sundance to know that American Indian and Alaska Native culture has endured. Though there is great variability from one tribe to the next in terms of cultural values, beliefs, and practices, 4 , 90 certain threads cut across. Here we highlight extended family networks and traditional parenting and child-rearing beliefs as but a few of the cultural strengths upon which American Indian and Alaska Native children can draw.

Extended Family

Extended family is the central organizing unit of many American Indian and Alaska Native cultures, emphasizing interdependence, reciprocity, and obligation to care for one another. 91 Within this extended network of care, American Indian and Alaska Native children develop strong relationships and attachments with not only their immediate biological family, but also with aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents. Familial bonds often extend beyond blood relatives to include important others who may be adopted into a family. Therefore, it is common for American Indian and Alaska Native children to have several grandmothers and grandfathers, aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters, or cousins who, although not related through blood or marriage, are nonetheless treated as if they were. This large extended network of blood and traditional relationship ties safeguards American Indian and Alaska Native children in their development by monitoring behavior and ensuring their integration within the larger family group. 4 The close intergenerational relationships also provide opportunities for elder members of the family to pass on tribal stories, songs, and practices that convey values by which to live. 92

Parenting and Child-rearing Beliefs

Across American Indian and Alaska Native cultures, children are regarded as gifts to be honored and cherished. 4 Children and families’ participation in ceremonies give life to this sentiment by celebrating milestones in development and providing children with a sense of belonging within the larger family and community. Examples include naming ceremonies in which a child is given a meaningful Indian name or celebrations to mark a child’s first smile. 4 American Indian and Alaska Native cultures also foster children’s autonomy and individuality through parenting practices that support children in making their own decisions and acting autonomously from a young age, and practices that promote learning through experience, listening, and observing the world around them and the behavior of others over explicit instruction. 4 , 92 , 93 , 95 Emerging evidence suggests that the extent to which parents adhere to traditional tribal values is related to positive aspects of children’s early development. 96 ; furthermore, children’s own identification with traditional culture appears to guard against mental health problems as they grow older. 73

The Promise of Early Childhood Intervention for American Indian and Alaska Native Children

As we have argued elsewhere, the time to move beyond documenting health disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native communities to designing and implementing effective culturally informed intervention has long since arrived. 10 American Indian and Alaska Native communities have been increasingly frustrated by research that serves simply to document problems that they have long known to exist. At the same time, they are reluctant to accept interventions derived from other’s experiences that do not consider their unique social and cultural contexts. Building on the demonstrated success of many early childhood interventions 97 and a commitment in American Indian and Alaska Native communities to prevention through work with young children, our team has been exploring options for such interventions in many contexts—most immediately in developing an approach to feeding and regulation in infancy, 98 which we are now extending to the prevention of early childhood caries. In both cases, the goal is to build on the model developed by Olds, 99 by targeting first-time mothers as they prepare for the transition to parenthood, encouraging and supporting healthy behavior for both themselves and their children. In other efforts we are exploring approaches to working with mothers to promote stimulating language environments for their infants and toddlers and to reduce alcohol use among women of childbearing age to prevent fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in reservation communities.

Many of the disparities experienced by American Indian and Alaska Native children highlighted above are, at a minimum, exacerbated by educational disparities and may in fact be causally related to the problems students experience in the educational system, especially insofar as they are driven by poor health literacy and health behavior. Accordingly, addressing American Indian and Alaska Native educational disparities has become an important priority as well—and we are addressing these issues directly through our American Indian and Alaska Native Head Start Research Center and related research.

Historically, educational institutions have not played a positive role in American Indian and Alaska Native communities; they have participate in the remove of American Indian and Alaska Native children from their families and communities, 100 forbidden the use of American Indian and Alaska Native languages and cultural practices, 101 , 102 and been a part of larger efforts to undermine tribal life ways and practices through the assimilation of children into the larger society. 103 – 105 It is, therefore, not surprising that American Indian and Alaska Native children have often fared poorly in primary and secondary educational settings, with high absenteeism and dropout rates and low achievement and parental involvement. 103 , 106

Nevertheless, school settings today can play an important role in fostering American Indian and Alaska Native children’s development in culturally supportive ways. 102 In light of the already described challenges faced by American Indian and Alaska Native children, educational institutions emerge as vehicles for intervention and support of cultural strengths. However, if this promise is to be realized, educational institutions and programming must take into account the needs of American Indian and Alaska Native communities as determined by American Indian and Alaska Native communities, as well as make meaningful changes to practices that continue to undermine American Indian and Alaska Native culture and children’s development. 101 , 103 , 107

The literature on American Indian and Alaska Native education suggests some goals for future programming that are based on observations of what has and has not worked from the perspective of the communities themselves. Foremost is the importance of working collaboratively with communities to determine the goals and activities of educational programming. 100 , 101 , 103 , 104 , 107 , 108 Doing so often means incorporating traditional cultural teachings and language. 102 Second, educational institutions must acknowledge that communities often identify different norms for what is considered desirable behavior and goals of education. 100 , 109 In practice, doing so means reconsidering the use and validity of traditional means of assessing behavior and educational achievement (e.g., standardized norm-referenced tests), 101 , 104 , 110 – 112 as well as extending involvement in the assessment process to parents and extended family. 100 , 108 , 110 It also means acknowledging and accommodating differences in learning styles that American Indian and Alaska Native children may exhibit (e.g., silence and observation over verbal exchange). 104 Finally, there must be support of the school infrastructure, with special attention to the availability of appropriate facilities and adequately trained and qualified school staff. 107

Our work under the American Indian and Alaska Native Head Start Research Center was designed to respond to these problems in addressing the educational and health disparities for the youngest American Indian and Alaska Native children, by fostering high-quality research training for the next generation of Native investigators in early childhood intervention, and by stimulating new research on issues of key concern in American Indian and Alaska Native Head Start programs. Efforts to date have focused on ways to improve the program quality of American Indian and Alaska Native Head Starts and Early Head Starts but are now moving, under the direction of a steering committee of American Indian and Alaska Native Head Start program directors, to explore the implications of these service improvements for the experiences of children and families.

Although we certainly do not intend to minimize the challenges such research in early intervention confronts, both our community partners and we are excited by the prospects this work raises to better delineate the factors that contribute to the disparities we have documented here and to begin to address them systematically. Such work has the prospect of raising additional resources for American Indian and Alaska Native communities, but we are also aware of the severe constraints under which most American Indian and Alaska Native communities continue to operate, so the focus is on developing sustainable interventions that fit the abilities of local service ecologies and labor forces. Until such time as we address the persistent inequalities in societal support for indigenous wellness, such compromises will, unfortunately, continue to be required. We would be loath to think that any success such efforts would excuse any of us from taking a closer look at our neglected obligations to the first people of this continent.

Conclusions

As this review of the literature makes clear, there remain enormous gaps in our knowledge of the predicaments confronted by American Indian and Alaska Native children, but we have long known enough to begin to act, in concert with indigenous communities, to begin to address the most glaring disparities. Both our community partners and we are placing bets on the value of early intervention, beginning prenatally with a mother’s first pregnancy, and extending throughout the first years of life and beyond, as one of the surest ways to begin to address past centuries of neglect and improve the prospects of American Indian and Alaska Native children in this century.

Acknowledgments

The writing of this report was supported by funds from the Administration on Children and Families (90-YF-0053; P. Spicer, PI), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD42760; P. Spicer, PI), and the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH63260; M. Sarche, PI).

Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous Peoples are culturally distinct societies and communities. Although they make up approximately 6% of the global population, they account for about 19% of the extreme poor.

Indigenous Peoples are distinct social and cultural groups that share collective ancestral ties to the lands and natural resources where they live, occupy or from which they have been displaced. The land and natural resources on which they depend are inextricably linked to their identities, cultures, livelihoods, as well as their physical and spiritual well-being. They often subscribe to their customary leaders and organizations for representation that are distinct or separate from those of the mainstream society or culture. Many Indigenous Peoples still maintain a language distinct from the official language or languages of the country or region in which they reside; however, many have also lost their languages or on the precipice of extinction due to eviction from their lands and/or relocation to other territories, and in. They speak more than 4,000 of the world´s 7,000 languages though some estimates indicate that more than half of the world's languages are at risk of becoming extinct by 2100.

There are an estimated 476 million Indigenous Peoples worldwide . Although they make up just 6 percent of the global population, they account for about 19 percent of the extreme poor . Indigenous Peoples’ life expectancy is up to 20 years lower than the life expectancy of non-Indigenous Peoples worldwide. Indigenous Peoples often lack formal recognition over their lands, territories and natural resources, are often last to receive public investments in basic services and infrastructure and face multiple barriers to participate fully in the formal economy, enjoy access to justice, and participate in political processes and decision making. This legacy of inequality and exclusion has made Indigenous Peoples more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and natural hazards , including to disease outbreaks such as COVID-19.

While Indigenous Peoples own, occupy, or use a quarter of the world’s surface area. Indigenous Peoples conserve 80 percent of the world´s remaining biodiversity and recent studies reveal that forestlands under collective IP and local community stewardship hold at least one quarter of all tropical and subtropical forest above-ground carbon They hold vital ancestral knowledge and expertise on how to adapt, mitigate, and reduce climate and disaster risks.

Much of the land occupied by Indigenous Peoples is under customary ownership, yet many governments recognize only a fraction of this land as formally or legally belonging to Indigenous Peoples . Even when Indigenous territories and lands are recognized, protection of boundaries or use and exploitation of natural resources are often inadequate. Insecure land tenure is a driver of conflict, environmental degradation, and weak economic and social development. This threatens cultural survival and vital knowledge systems – loss in these areas increasing risks of fragility, biodiversity loss, and degraded One Health (or ecological and animal health) systems which threaten the ecosystem services upon which we all depend.

Improving security of land tenure, strengthening governance, promoting public investments in quality and culturally appropriate service provision, and supporting Indigenous systems for resilience and livelihoods are critical to reducing the multidimensional aspects of poverty while contributing to sustainable development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The World Bank works with Indigenous Peoples and governments to ensure that broader development programs reflect the voices and aspirations of Indigenous Peoples.

Over the last 30 years, Indigenous Peoples’ rights have been increasingly recognized through the adoption of international instruments such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of I ndigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, the Ameri can Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2016, the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (Escazú Agreement) in 2021 and the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention from 1991. At the same time, global institutional mechanisms have been created to promote Indigenous peoples’ rights such as the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP), and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNSR).

Last Updated: Apr 06, 2023

The World Bank has established a network of Regional Indigenous Peoples Focal Points who work together with a Global Coordinator for Indigenous Peoples. This network of professionals works to enhance the visibility and inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in the Bank’s analytical work, Systematic Country Diagnostics (SCDs), Country Partnership Frameworks, national policy dialogues, and public investment lending and trust funds.

The E nvironmental and Social Framework (ESF) , the World Bank’s framework that supports borrowers to better manage project risks as well as improve environmental and social performance, contains a standard on Indigenous Peoples/Sub-Saharan African Historically Underserved Traditional Local Communities (ESS7). This standard contributes to poverty reduction and sustainable development by ensuring that projects supported by the Bank enhance opportunities for Indigenous Peoples to participate in, and benefit from, the investments financed by the Bank in ways that respect their collective rights, promote their aspirations, and do not threaten or impact their unique cultural identities and ways of life. Currently, ESS7 is being applied in approximately 33 percent of the Bank’s investment lending.

The World Bank is engaging with Indigenous Peoples’ organizations to better understand and build upon traditional knowledge for climate change mitigation and adaptation solutions. Through direct grants to indigenous organizations and inclusion in national programs, the Bank is also working to promote the recognition and strengthening of Indigenous Peoples’ significant contributions as stewards of the world’s forests and biodiversity.

This is particularly relevant to the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation plus (REDD+) agenda, where – given their close relationships with and dependence on forested lands and resources – Indigenous Peoples are key stakeholders. Specific initiatives in this sphere include: a Dedicated Grant Mechanism (DGM) for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities under the Forest Investment Program (FIP) in multiple countries; a capacity building program oriented partly toward Forest-Dependent Indigenous Peoples by the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) ; support for enhanced participation of Indigenous Peoples in benefit sharing of carbon emission reduction programs through the Enhancing Access to Benefits while Lowering Emissions - EnABLE Fund; and analytical, strategic planning, and operational activities in the context of the FCPF and the BioCarbon Fund Initiative for Sustainable Forest Landscapes (ISFL) . Indigenous Peoples are also observers to the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) .

Increased engagement and dialogue and awareness of Indigenous Peoples’ rights have yielded results at the global, regional, country, and community levels. Examples include:

World Bank direct dialogues with Indigenous Peoples

At a global level, the Bank holds an ongoing dialogue with the Inclusive Forum for Indigenous Peoples (IFIP), comprised of Indigenous Peoples representatives from Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and South Asia. This dialogue provides an opportunity for the Bank to deepen understanding on issues critical for Indigenous Peoples across the globe and inform Bank strategies. It also serves to inform Indigenous leaders about Bank strategies and work and allows for learning across regions. Finally, it serves to facilitate dialogue for Indigenous organizations with the Bank’s regional and country teams.

At a regional level, the World Bank’s Latin American and Caribbean team maintains an ongoing dialogue and strategic work with the Abya Yala Indigenous Forum (FIAY) and the Indigenous Fund for Latin American and the Caribbean (FILAC). The objective of this dialogue is to enhance mutual understanding between the Bank and Indigenous organizations, facilitate the more effective application of ESS7, and build Indigenous Peoples inclusion and voice in the policy dialogue and investments financed by the Bank in the Region.

At national levels, in Nepal , the Bank has launched an Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Consultative Forum. This Forum serves as a round-table for knowledge exchange and dialogue to enhance the Bank’s engagement with Indigenous peoples and/or local communities across the portfolio in Nepal, with a particular focus on forestry. The first Forum meeting was held on March 14th, 2022 and will continue on a quarterly basis.

In Kenya , the Bank is supporting the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC) to develop an Inclusive Development Framework for Marginalized Communities.

Advancing knowledge and analytics relevant for Indigenous Peoples

In the Philippines , the Bank has been implementing an Indigenous Peoples engagement strategy focusing on four pillars: a) Dialogue with IP communities and other ethnic minorities, NGOs and CSOs working on IP issues; b) Partnerships with government agencies and donors to promote IP inclusion; c) Data and Analytics to build robust evidence demonstrating the developing challenges affecting indigenous populations; and d) Policy and Operations to mainstream IP issues within Bank operations and also propose IP-specific IPF projects directly benefiting and promoting indigenous communities. In this regard, three core activities are underway: An Indigenous Peoples report titled "No Data No Story: Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines Report; An Indigenous Peoples and Ancestral Domains Data and Information Platform and Portal; An Indigenous Peoples-specific household survey to provide data that will inform the Bank's and government's policy and operations.

In an effort to contribute to global public knowledge, the Bank has been advancing two initiatives to promote knowledge and good practice in priority areas for Indigenous peoples. These include: (i) a Good Practice Note of Commercial Development in Indigenous Peoples Lands & Territories, and (ii) a Technical Note on the Key Drivers for Indigenous Peoples Resilience, that is being prepared with Indigenous leaders and organizations. In addition to informing Bank finance and policy dialogue on how to best support IP resilience, the Note also aims to contribute to building more resilient societies by promoting a deeper understanding of the benefits of Indigenous peoples' practices of collectivity, solidarity, and sustainable co-existence with the natural environment.

Indigenous Peoples in World Bank Systematic Country Diagnostics (SCDs) and Country Partnership Frameworks (CPFs)

Building on the engagement and analytics of the World Bank in countries across the world, Indigenous Peoples are gaining increased visibility in upstream country planning documents. Illustrative examples can be found in the SCDs and CPFs of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Guatemala, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Panama, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands, and Vietnam .

Investing in Indigenous Peoples’ priorities

In Kenya , the Financing Locally Led Climate Action (FLLoCA) program is supporting partnerships between governments and communities to assess climate risks and identify socially inclusive solutions that are tailored to local needs and priorities. Indigenous peoples or traditionally marginalized groups represent a significant proportion of beneficiaries.

In 2020 the World Bank approved Development Policy Operations (DPOs) in Guatemala and Panama that included policy reforms in areas prioritized by Indigenous Peoples. These include: the approval of the Action Plan to Implement the National Midwives Policy in Guatemala and the approval a legal framework that legally adopts the National Indigenous Peoples Development Plan of Panama, requiring a national budgetary allocation for its implementation each year. Both of these policy actions have been subsequently approved by the national authorities in these countries.

In Ecuador , the Bank approved a loan for $40 million to support territorial development priorities for Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, and Montubian peoples and nationalities in the areas of economic development, governance, and COVID-19 response. This project was designed and will be implemented by the Government of Ecuador in partnership with Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian and Montubian organizations at both national and territorial levels.

In Panama , in 2018, the Bank approved the first loan in more than 20 years for $80 million to support what Indigenous Peoples have put forward as their vision for development through the National Indigenous Peoples Development Plan. Jointly developed by Indigenous Peoples, the government and World Bank, this project aims to strengthen governance and coordination for Indigenous Peoples to partner as drivers in their own development, while supporting improvements in access, quality, and cultural pertinence of basic service delivery, in accordance with the Indigenous Peoples’ vision and development priorities.

In Laos , the Poverty Reduction Fund Project (PRF) III was established as one of the Government of Lao PDR's main vehicles to decrease rural poverty and deliver infrastructure services in rural areas. Under the two preceding World Bank-supported projects, the PRF has improved access to infrastructure for well over a million-rural people through implementing more than 4,700 subprojects. The PRF II (2011-2016) alone improved access to infrastructure for more than 567,000 rural people, financing 1,400 subprojects prioritized by beneficiary communities . Ethnic minorities account for approximately 70% of project beneficiaries.

In Cambodia , the Voice and Action: Social Accountability for Improved Service Delivery project facilitated and supported the social inclusion of ethnic minorities, women, and other vulnerable and marginalized communities in effective access to service delivery. Ethnic minorities were hired by local government as community accountability facilitators and improved the quality of service provision in six different Indigenous languages (Khmer-Lao, Kreung, Kuoy, Proav, Mill, and Kraol) through mobile loudspeaker and radio broadcasts.

Approximately 33 percent of the Bank’s investment portfolio applies ESS7, and in so doing, is ensuring that governments work in consultation withIndigenous Peoples to promote their inclusion in project benefits and mitigation of adverse impacts.

Direct grants to Indigenous Peoples through Climate, Forestry and other Trusts Funds

- Climate change is a priority area where the World Bank works closely with Indigenous Peoples and seeks to deepen and expand engagement. The World Bank has supported three different direct grant mechanisms for Indigenous peoples, which have gradually contributed to capacity building and participation of Indigenous Peoples in climate policy dialogue, forest management, and participation in the benefits of emissions reductions.

Last Updated: May 10, 2023

Social Sustainability & Inclusion

World bank operational policies.

- Show More +

- Facebook Live on Indigenous Peoples:

- Publications:

- Our People, Our Resources: Striving for a Peaceful and Plentiful Planet

- Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-First Century

- India's Adivasis

- A closer look at child mortality among Adivasis in India

- India: Unlocking Opportunities for Forest-Dependent People in India

- Blog posts:

- Why we need to talk about Roma inclusion

- Urban Indigenous Peoples: the new frontier

- Yes, how many deaths will it take till we know…

- Indigenous peoples, forest conservation and climate change: a decade of engagement

- Show Less -

Plan de Desarrollo Integral de los Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá

Around the bank group.

Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing on Indigenous Peoples.

STAY CONNECTED

Additional resources, related topics, media inquiries.

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

A reservation town fighting alcoholism, obesity and ghosts from the past

In the Native American community of Blackwater, Arizona, gambling money flows from nearby casinos but personal incomes remain among the lowest in the US. Chris McGreal visits for the last in his series on America’s poorest towns

Part 1: America’s poorest white town: abandoned by coal, swallowed by drugs

Part 2: Poorest town in poorest state: segregation has gone, but so have the jobs

Part 3: America’s poorest border town: no immigration papers, no American Dream

Chuck Morgan is back where he began. Almost.

“There used to be an old building, like a barn, up on the hill there. We lived there and we had no water, no electricity, no bathroom. We had an outhouse. We had to live by lamps. Wood stoves. Trucked our own water in by wagon,” he said. “We had just two big old rooms. A living room and a bedroom together. The whole family there. The other room was a little kitchen.”

Morgan is 64 now. In his time he’s been a logger in California, fought in Vietnam and sought release in drugs and alcohol, before being drawn back to the small town of Blackwater on the sprawling Gila River Indian reservation in southern Arizona – “the res”, as it’s known to those who live there.

When he left half a century ago in search of a path out of deprivation, the reservation was best known outside its borders as the home of Ira Hayes, one of six US marines immortalised in the photograph of soldiers raising an American flag over the Japanese island of Iwo Jima in the second world war. Hayes was hailed by presidents and feted across the country. But his decline into alcoholism – he was arrested dozens of times for drunken behaviour – and drink-related death at the age of 32 was often portrayed as a consequence of life on the reservation, although the toll of war and fame may have had more to do with it.

Gila River Indian Community, known on the reservation as the GRIC, is defined to the outside world by something else these days: the highest rate of obesity and diabetes in the United States. Its people have probably been subjected to more medical studies of the disease than any other on the planet.

But even that development is being eclipsed by another change. “This place is different. So different from when I left,” said Morgan. “They give you a house now. A free house. My brother got one. They give you it without paying a penny, and free water. Everything started getting different when these casinos came up.”

For 20 years, the GRIC has tapped into the wellspring that has reversed the fortunes of Native American communities close to a city big enough to provide a steady stream of punters for slot machines and blackjack tables. Gila River has Phoenix’s 4 million residents a few minutes’ drive away.

The flow of hundreds of millions of dollars each year into Gila River’s casinos helps fund the outlines of a welfare state in a country where the very idea is widely regarded as un-American. Free land and free houses. Its own healthcare system. Regular cash payments to all residents as their slice of the gambling revenues. Even the first Indian reservation television station.

While most young Americans rack up debts getting a university education , Gila River reservation helps pay the bills. For elderly people there are free meals and organised trips to the cinema.

For all that, Blackwater has been, by one measure, the poorest – or at least the lowest income – town in the country. According to the US census bureau’s American community survey 2008-2012 of communities of more than 1,000 people – the latest statistics available at the time of reporting – the median household income in Blackwater was just $9,491 a year. Nationally it was $53,915 in 2012. It has improved more recently to $12,723, but is still less than a quarter of the national average. It is the final stop in a series of Guardian dispatches about the lives of people trying to make a life in places that seem the most remote from the American Dream.

“I was picking cotton in the fields at five years old,” said Lidya, who would only give her first name. She was one of the women working at a centre in Blackwater that provides free lunches for elderly people. “You had this long sack and you had to fill it with cotton. This wasn’t 1868, it was 1968. The casinos changed a lot of things. We’re dependent on them now but there is still that poverty out there. The majority of people here struggle to get by.”

Blackwater sits at the southern end of the 580 square miles designated by the US Congress in 1859 as a home for two tribes - the Akimel O’odham tribe (also known as the Pima) and the Pee Posh (also known as the Maricopa).

The area around the town of little more than 1,000 people – 94% Native American – is mostly farmland and desert. The dried-up bed of the Gila river, which was once the tribes’ lifeblood, is at the town’s eastern flank with the San Tan mountains as backdrop.

Facilities in Blackwater are few beyond tribal offices. No cafes, bars or restaurants. The new houses paid for by the casino revenues, clustered together in their own neighbourhoods, stand out from the crumpled homes that have endured decades of desert winds.

There is a stillness about the place during the day. Those who work are at the casinos, in the fields or have commuted to one of the towns off the reservation. Those who don’t work are kept indoors by the heat.

The road north runs the length of Gila River reservation, passing one largely indistinguishable community after another until the skyscrapers of Arizona’s capital, Phoenix, rise up against the mountains.

The reservation’s northern tip reaches almost to the city limits. It is the geography of this small corner that has delivered the promise of a different future. The tribal council has taken advantage of a 1987 US supreme court ruling that recognised a degree of sovereignty for Native American reservations as “domestic dependent nations”. Gila River joined the band of Indian communities that got into the casino businesses after the justices said state governments had no authority to stop or regulate them.

The reservation spent $200m building the Wild Horse Pass casino and hotel , the largest in the state when it was completed. The luxury resort now includes a concert venue, golf course and a motorsports race track. The tribal council, as on other reservations, won’t reveal how much it makes from the Wild Horse and two other casinos on Gila River but estimates put it at around $250m a year.

The high-priced cocktails and luxury cars – and the wads of cash lost on the turn of a card – reflect a lifestyle those who live in Blackwater only glimpse if they trouble to venture to the other end of the reservation.

More than half of Blackwater’s residents live below the poverty line. Half of those have an income that is less than half the level set as the poverty line. About one-third of the working-age population is unemployed. Yet the numbers are only part of the story.

Gila River reservation has had its fleeting moments of fame – and infamy. It was the site of an internment camp for thousands of Japanese Americans during the second world war, over the objections of the tribes.

Towards the war’s end, Ira Hayes’s return from Japan brought a more welcome kind of attention. He is in the far left of the photograph as the American flag is lifted over Iwo Jima during the battle with the Japanese for the island. Within days, three of the six soldiers in the picture were dead.

Years later, his life story was told in a film, The Outsider, where a white man, Tony Curtis, played the Native American hero. It also inspired a Johnny Cash hit, The Ballad of Ira Hayes, with lyrics touching on a bitter legacy that is the source of many of the reservation’s problems to this day:

The water grew Ira’s people’s crops ’Til the white man stole the water rights And the sparklin’ water stopped.

The sparkling waters of the Gila river made the tribes who lived around it successful farmers. The river irrigated beans, corn and cotton. The Spanish brought new crops, wheat and watermelon, and cattle in the 17th century. By the 1850s, the tribes were prospering selling food and cotton to white settlers and miners.

The US government encouraged whites to trek west and populate Arizona territory by promising free land on condition it was cultivated. That required the settlers to irrigate from the Gila river. As their numbers grew, so more of the river was diverted, until it was reduced to a near trickle by the late 19th century.

Drought was the final blow. The tribes were forced to rely on food from the US government. It sent lard, white flour and canned meats, changing the eating habits of the Native Americans . Today, bread fried in lard is not only popular but regarded as traditional. The small game and birds their ancestors hunted gave way to fatty beef.

Photographs of the reservation’s beauty queens line a wall at the tribal headquarters in Sacaton. They are radiant and smiling. They are also what clothing manufacturers would describe as on the plus size.

Size matters because it represents fears for the future of the reservation’s young, even if it is a highly sensitive subject after Gila River’s residents were labelled the fattest people in America by the media.

Half of all working-age adults within the GRIC have type 2 diabetes. Among teenagers 15 to 19, the rate is more than 10 times that of the Native American population as a whole in the US. Close to nine out of 10 residents will be diagnosed with the disease by the age of 55.

Two years ago, Blackwater community school warned the federal government in a grant application (pdf) that it had a high number of children with “unhealthy” weight levels on the reservation. “Unfortunately, many of the children at Blackwater community school are at risk to develop type 2 diabetes as children,” it added.

Diabetes increases the risk of heart attacks and kidney failure . At the elderly centre in Blackwater, Lidya said that of the 100 people she served lunch to every day, a dozen were on dialysis.

That it wasn’t always this way is clear from Pima people living in Mexico, where diabetes rates are considerably lower and about the same as in the rest of that country. Not only do Mexican Pima eat more healthily but they do more physical activity as farmers.

People on the reservation sometimes feel as if they are part of one large clinical study. The National Institutes of Health arrived five decades ago to try to account for the levels of obesity and diabetes. Almost all of the population is now involved in the research.

An extraordinary number of academic papers have been written. Theories have come and gone, including of a gene that developed in the Pima to store body fat to cope with periods of famine, which has made it hard to shed excess weight.

The tribal authorities have responded with relentless health campaigns. Billboards promote “health and wellness fairs” and mass exercise drives in the parks. Stark warnings about diet spring from the community newspaper. The reservation’s health department placed an advert picturing sugar pouring from a can of Coca-Cola. There is no caption. Everyone understands.

The soft drinks and sugar industries would probably have pounced on such a graphic warning by any other public authority, but the same political rules do not apply on the reservation.

Casino revenues have paid for a well-equipped gym in Blackwater, and there’s an indoor basketball court next door that would be the envy of many American high schools. But the gym looks as though it is rarely visited and Alan Blackwater, chairman for the district that covers the town and surrounding area, laments that young people don’t use the basketball court much either.

“They barely come here except for community meetings,” he said. “We’ve got all kinds programmes. Walks. Prevention. That kind of stuff. It makes a difference for some people. Not everyone.”

Blackwater was diagnosed with the disease in the 1990s. “I have diabetes. Practically everybody does. Eating the wrong kind of food, I guess. It took years and years and years before I changed my lifestyle,” he said. “I don’t take no medication. I eat the right kind of food now. I changed that. I exercise but not right now because I’ve got a bum knee.”

For all of the campaigns, diabetes rates continue to rise among young people.

Something else has been linked by the GRIC’s health department to the development of the disease: the stresses of reservation life, particularly “poverty, unemployment, crime, gang activity”.

Blackwater has lived within the Gila River community his whole life. He said it had always been beset by problems common to other reservations. When he was young, it was routine for men to leave to look for work.

“They had a relocation programme way back where they would move them off to try and get a trade,” he said. “Move them to the cities like Chicago, California. There was nothing for them here. Some of them never came back.”

Morgan remembers the hardship. “I had a kerosene lamp to do my homework. Maybe that’s why I wear glasses now,” he said. “My grandparents lived across the river the same way. We kind of grew up there too because my dad drank a lot. I guess it was rough but it didn’t seem like it then. My dad got hold of someone who had a vacant house. We moved there. It was a little better. Had electricity, lights.”

When Morgan was 14 he persuaded his parents to send him to a boarding school in California. The tribal government paid. “Right after I graduated from school, I enlisted in the marine corps. Boot camp in San Diego. Went to combat infantry school and then, whoosh, Vietnam,” he said.

A red US marines flag flies over Morgan’s house. It represents a complex past. On the one hand there’s Ira Hayes. On the other, Vietnam veterans were for a long time regarded as akin to war criminals by many Americans.

“The guys fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, they’re way up here,” said Morgan, lifting his hand above his grey hair. “Vietnam veterans were way down here,” he added, lowering his hand to his knee.

Then there is Native American history at the hands of the US army.

The military has long been a path off reservations for young men and, more recently, women, who have limited choices if they remain at home. A disproportionately high number of Native Americans sign up.