- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: Sociopolitical Contexts of Education

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 91097

- Deanna Cozart, Brian Dotts, James Gurney, Tanya Walker, Amy Ingalls, & James Castle

- University of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Although educational policies and practices are sometimes viewed as if they existed in a vacuum, separate from the larger social, political, and cultural contexts, one of the central tenets of multiculturalism asserts that educational decision-making is heavily influenced by each of these contexts. In particular, many scholars of multicultural education point to the importance of the sociopolitical context of education in the modern era as educational policies and practices are increasingly becoming politicized. Given the political nature of educational decision making, the educational policies and practices implemented at national, state, and local levels reflect the values, traditions, and worldviews of the individuals and groups responsible for their design and implementation, which inherently makes education a non-neutral process, though it is often seen as such. Understanding the sociopolitical context of education allows for a critical analysis of educational policies and practices in an effort to reduce educational inequalities, improve the achievement of all students, and prepare students to participate in democratic society.

In the field of multicultural education– and across the social sciences– the sociopolitical context refers to the laws, regulations, mandates, policies, practices, traditions, values, and beliefs that exist at the intersection of social life and political life. For example, freedom of religion is one of the fundamental principles of life in American society, and therefore there are laws in place that protect every individual’s right to worship as they choose. In this instance, the social practices (ideologies, beliefs, traditions) and political process (laws, regulations, policies) reflect each other and combine to create a sociopolitical context that is, in principle, welcoming to all religious practices. There are similar connections between the social and the political in the field of education. Given that one of the main purposes of schooling is to prepare students to become productive members of society, classroom practices must reflect– to some extent– the characteristics of the larger social and political community. For example, in the United States, many schools use student governments to expose students to the principles of democratic society. By organizing debates, holding elections, and giving student representatives a voice in educational decision making, schools hope to impart upon students the importance of engaging in the political process. The policies and practices that support the operation of student government directly reflect the larger sociopolitical context of the United States. Internationally, the use of student government often reflect the political systems used in that country, if a student government organization exists at all. However, sociopolitical contexts influence educational experiences in subtler ways as well.

Throughout the history of American education, school policies and practices have reflected the ideological perspectives and worldviews of the underlying sociopolitical context. As stated above, schools in democratic societies often have democratic student government organizations that reflect the political organization of the larger society, while similar organizations cannot be found in schools in countries that do not practice democracy. Similarly, if a society shares a widespread belief that some groups (based on race, class, language, or any other identifier) are inherently more intelligent than another, educational policies and practices will reflect that belief. For example, as the United States expanded westward into Native American lands during the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries, many Americans shared the widespread belief that Native Americans were inherently less intelligent and less civilized than white Americans. This belief system served as a justification for the “Manifest Destiny” ideology that encouraged further westward expansion. Not surprisingly, the larger sociopolitical context of the time influences educational policies and practices. In large numbers, young Native Americans were torn from their families and forced into boarding schools where they were stripped of their traditions and customs before being involuntarily assimilated into “American culture”. These Native American boarding schools outlawed indigenous languages and religions. They required students to adopt western names, wear western clothes, and learn western customs. While from a contemporary perspective these schools were clearly inhumane, racist, and discriminatory, they illustrate how powerful the sociopolitical climate of the era can be in the implementation of educational policies and practices. Educational policies today continue to reflect the larger social and political ideologies, worldviews, and belief systems of American society, and although instances of blatant discrimination based on race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexual orientation, language, or any other identifier have been dramatically reduced in recent decades, a critical investigation into contemporary schooling reveals that individuals and groups are systematically advantaged and disadvantaged based on their identities and backgrounds, which will be explored in more depth in subsequent sections of this (book/class).

The role of social institutions in educational experiences are another key consideration in developing an understanding of the sociopolitical contexts of education. The term social institutions refer to the establish, standardized patterns of rule governed behavior within a community, group, or other social system. Generally, the term social institutions includes a consideration of the socially accepted patterns of behavior set by the family, schools, religion, and economic and political systems. Each social institution contributes to the efficiency and sustained functionality of the larger society by ensuring that individuals behave in a manner that consistent with the larger structure, which allows them to contribute to the society. Traffic regulations offer an example of how social institutions work together to create and ensure safety and efficiency in society. In order to reduce chaos, danger, and inefficiency along roadways in the United States, political institutions have created laws and regulations that govern behavior along public roads. Drivers found in violation of these regulations face punishment or fines that are determined by the judicial system. Furthermore, families and schools– and to some extent religions organizations– are responsible for teaching young people the rules and regulations that govern transportation in their society. The streamlined and regulated transportation system produced by the aforementioned social institutions allows economic institutions to function more efficiently. Functionalist Theory is a term used to refer to the perspective that institutions fill functional prerequisites in society and are necessary for social efficiency as seen in the previous example.

However, Conflict Theory refers to the idea that social institutions work to reinforce inequalities and uphold dominant group power. Using the same transportation example, a conflict theorist might argue that the regulations that require licensing fees before being able to legally operate a vehicle disproportionately impact poor people, which would limit their ability to move freely and thereby make it more difficult for them to hold and maintain a job that would allow them to move into a higher socioeconomic class. Another argument from the conflict theorist perspective might challenge institutionalized policies that require drivers to present proof of citizenship or immigration papers before being allowed to legally operate a vehicle. These policies systematically deny the right of freedom of movement to immigrants who entered the United States illegally, thereby limiting their civil rights as well as their ability to contribute to the American economy. Both the Functionalist Theory and Conflict Theory perspectives can contribute to a nuanced understanding of contemporary educational policies and practices by providing contrasting viewpoints on the same issue. Throughout these modules these perspectives will inform the discussion of educational institutions and how they influence– and are influenced by– other social institutions.

Much like educational policies and practices, the rules and regulations set by social institutions do not exist within a vacuum, nor are they neutral in regard to the way they impact individuals and groups. Institutional discrimination refers to “the adverse treatment of and impact on members of minority groups due to the explicit and implicit rules that regulate behavior (including rules set by firms, schools, government, markets, and society). Institutional discrimination occurs when the rules, practices, or ‘non-conscious understanding of appropriate conduct’ systematically advantage or disadvantage members of particular groups” (Bayer, 2011). Historical examples of institutional discrimination in abound in American history. In the field of education, perhaps the most well known example of institutionalized discrimination is the existence of segregated schools prior to the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. During this era, students of color were institutionally and systematically prevented from attending white schools, and instead were forced to attend schools that lacked sufficient financial, material, and human resources. Institutional discrimination in contemporary society, however, is often subtler given that there are a plethora of laws that explicitly prevent discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or any other identifier. Regardless of those laws, social institutions and institutionalized discrimination continue to disadvantage non-dominant groups, thereby advantaging members of the dominant group. Use housing as an example, homeowner’s associations are local organizations that regulate the rules and behaviors within a particular housing community. If a homeowner’s association decides that only nuclear families can live within their community and create a bylaw that stipulates such, the practice of allowing nuclear families and denying non-nuclear families becomes codified as an institutionalized policy. While the policy does not directly state that it intends to be discriminatory, it would disproportionately affect families from cultures that traditionally have households that include aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, and other extended family members, a practice that is common in many Asian, African, and South American communities. Although hypothetical, this example represents an example of the subtle ways in which institutional discrimination surfaces in contemporary society.

A more concrete example of institutionalized discrimination can be drawn from the housing market in New Orleans as homes were being rebuilt in the aftermath Hurricane Katrina. While the Lower Ninth Ward– a mostly black neighborhood– was among the most damaged neighborhood in New Orleans, just down river the St. Bernard Parish neighborhood– which was mostly white– was also heavily damaged. By 2009, most of St. Bernard Parish had been rebuilt, while the Lower Ninth Ward remained unfit for living. As families began moving back into the neighborhood, elected officials in St. Bernard Parish passed a piece of legislation that required property owners to rent only to ‘blood relatives’. In effect, the policy barred potential black residents from moving into the area and served to maintain the racial makeup of the neighborhood prior to Katrina. After several months of implementation, the policy was legally challenged and was found to be in violation of the Fair Housing Act in Louisiana courts. In 2014, the Parish agreed to pay approximately $1.8 million in settlements to families negatively affected by the policy. This example illustrates how institutionalized discrimination surfaces in contemporary society. Throughout the modules, instances of institutional discrimination in schools, as well as in American society as a whole, will be critically analyzed in order to develop an understanding of how educators can work to reduce inequality and promote academic achievement for all students.

A basic understanding of social institutions and institutional discrimination helps inform this course’s approach to key educational issues in the field of multicultural education. As the student body in American schools becomes increasingly diverse, it becomes increasingly important for future teachers to know and understand how students’ identities might impact their educational experiences as well as their experiences their larger social and political settings. While there are many issues facing education today, Nieto and Bode (2012) identified four key terms that are central to understanding sociopolitical context surrounding multicultural education. These terms include: equal and equitable education, the ‘achievement gap’, deficit theories, and social justice.

The terms equal and equitable are often used synonymously, though they have vastly different meanings. While most educators would agree that providing an equal education to all students is an important part of their mission, it is sometimes more important to focus on creating equitable educational experiences. At its core, an equal education means providing exactly the same resources and opportunities for all students, regardless of their background. An equal education, however, does not ensure that all students will achieve equally. Take English Language Learners (ELLs) as an example. A group of ELL students sitting in the same classroom as native English speakers, listening to the same lecture, reading the same books, and taking the same assessments could be considered an equal education given that all students are receiving equal access to all of the educational experiences and materials. The outcome of this ostensibly equal education, however, would not be equitable. The ELL students would not be able to comprehend the lecture, books, or assessments and would therefore not be given the real possibility of achieving at an equal level, which is the aim of an equitable education. Equity refers to the educational process that “provides students with what they need to achieve equality” (Nieto & Bode, 2012, p.9). In the case of the ELL example, an equitable education would provide additional resources– perhaps including ESL specialists, bilingual activities and materials, and/or programs that foster native language literacy– to the ELL students to ensure that they are welcomed into the classroom community and are given the opportunity to learn and succeed equally. Working towards educational equality by providing equitable educational experiences is one of the central tenets of multicultural education and will be a recurring topic throughout these modules.

A second key term that is crucial in understanding multicultural education is the ‘achievement gap’. A large body of research has documented that students from racially and linguistically marginalized groups as well as students from low-income families generally achieve less than other students in educational settings. Large scale studies of standardized assessments revealed that white students outperformed black, Hispanic, and Native American students in reading, writing, and mathematics by at least 26 points on a scale from 0 to 500 (Nieto and Bode, 2012; National Center for Educational Statistics, 2009). Though usage of the term has changed over time, it often focuses on the role that students themselves play in the underachievement, which has drawn criticism from advocates of multicultural education because it places too much responsibility on the individual rather than considering the larger sociopolitical and sociocultural contexts surrounding education. While gaps in educational performance no doubt exist, Nieto and Bode (2012) suggest that using terms such as “resource gap”, “opportunity gap”, or “expectations gap” may be more accurate in describing the realities faced by marginalized students who often attend schools with limited resources, limited opportunities for educational advancement or employment in their communities, and face lowered expectations from their teachers and school personnel (p.13). Throughout this (book/course) issues related to the achievement gap’ and educational inequalities based on race, class, gender, and other identifiers will be viewed within the larger social, cultural, economic, and political contexts in order to create a more holistic and systematic understanding of student experiences, rather than focusing purely on the individual.

Historically in educational research, deficit theories have been used to explain how and why the achievement gap exists, but since the 1970s, scholars of multicultural education have been working to dismantle the lasting influence of deficit theory perspectives in contemporary education. The term ‘deficit theories’ refer to the assumption that some students perform worse than others in educational settings due to genetic, cultural, linguistic, or experiential differences that prevent them from learning. The roots of deficit theories can be found in 19 th century pseudo-scientific studies that purported to show ‘scientific evidence’ that classified the intelligence and behavior characteristics of various racial groups. The vast majority of these studies were conducted by white men, who unsurprisingly, found white men to be the most intelligent group of human beings, with other groups falling in behind in ways that mirrored the accepted social standings of the era (Gould, 1981). Though many have been disproved, deficit theories continue to surface in educational research and discourse. Reports suggesting that academic underachievement is a product of cultural deprivation or a dysfunctional relationship with school harken back to deficit theory perspectives. Much like the ‘achievement gap’, deficit theories place the burden of academic underachievement on students and their families, rather than considering how the social and institutional contexts might impact student learning. Deficit theories also create a culture of despondency among educators and administrators since they support the idea that students’ ability to achieve is predetermined by factors outside of the teacher’s control. Multicultural education aims to disrupt the prevalence of deficit theory perspectives by encouraging a more nuanced analysis of student achievement that considers the structural and cultural contexts surrounding American schooling.

The fourth and final term that is central to understanding the sociopolitical context of multicultural education is social justice. Throughout these modules, the term social justice will be employed to describe efforts to reduce educational inequalities, promote academic achievement, and engage students in their local, state, and national communities. Social justice is multifaceted in that it embodies the ideologies, philosophies, approaches, and actions that work towards improving the quality of life for all individuals and communities. Not only does social justice aim to improve access to material and human resources for students in underserved communities, it also exposes inequalities by challenging and confronting misconceptions and stereotypes through the use of critical thinking and activism. Finally, in order for social justice initiatives to be successful, they must “draw on the talents and strengths that students bring to their education” (Nieto and Bode, 2012, p.12). This allows students to see their experiences represented in curriculum content, which can empower and inspire students– not only to excel academically– but also engage in activities that strengthen and build the community around them. These key components of social justice permeate throughout the field of multicultural education.

In order to develop a holistic understanding of educational experiences, these modules will interpret and analyze educational policies and practices through a lens that considers the sociopolitical contexts of education. By recognizing the role that social and political ideologies have over educational decision making, multicultural approaches to education aim to reduce educational inequalities, improve the achievement of all students, and prepare students to participate in democratic society.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Social Work

- About the British Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Understanding social policy from the social work perspective

- Current status of social work’s engagement in social policy

Social Work and the Changing Context: Engagement in Policymaking

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Surinder Jaswal, Melody Kshetrimayum, Social Work and the Changing Context: Engagement in Policymaking, The British Journal of Social Work , Volume 50, Issue 8, December 2020, Pages 2253–2260, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa234

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Social work’s prime responsibility is to engage with people and structures to address life challenges and enhance well-being in order to further social change, social development, social cohesion, empowerment (and liberation) of people. Engaging with people and structure requires an in-depth understanding of the local environment and the policy frameworks. Local environment such as resources, ecological community, and network of relationships between people is not static and social, economic, cultural and policy frameworks too change rapidly. The environment and frameworks within which social work professionals work and conduct research have changed and evolved over time. The socio-political landscape too has changed considerably over the last decade across the globe. The processes of globalisation, privatisation, new managerialism and technocratisation have further impacted different countries in different ways ( Gibbs, 2001). These socio-economic and political developments have brought large scale changes in the community structures, institutional power arrangements and welfare systems, which have further led to new forms of injustice, oppression and discrimination. The gaps in the social structure are widening and new vulnerabilities have been created which pose serious threats to the well-being of people. As a result, subaltern voices on equality, social justice, human rights, development, security, education, health and mental health, employment, immigration and empowerment have emerged against the socio-political structures and systems. The varied ways in which these voices have played out differs from one environment to another.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-263X

- Print ISSN 0045-3102

- Copyright © 2024 British Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2018

Integrating evidence, politics and society: a methodology for the science–policy interface

- Peter Horton 1 &

- Garrett W. Brown 2

Palgrave Communications volume 4 , Article number: 42 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

21 Citations

22 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Operational research

- Science, technology and society

There is currently intense debate over expertise, evidence and ‘post-truth’ politics, and how this is influencing policy formulation and implementation. In this article, we put forward a methodology for evidence-based policy making intended as a way of helping navigate this web of complexity. Starting from the premise of why it is so crucial that policies to meet major global challenges use scientific evidence, we discuss the socio-political difficulties and complexities that hinder this process. We discuss the necessity of embracing a broader view of what constitutes evidence—science and the evaluation of scientific evidence cannot be divorced from the political, cultural and social debate that inevitably and justifiably surrounds these major issues. As a pre-requisite for effective policy making, we propose a methodology that fully integrates scientific investigation with political debate and social discourse. We describe a rigorous process of mapping, analysis, visualisation and sharing of evidence, constructed from integrating science and social science data. This would then be followed by transparent evidence evaluation, combining independent assessment to test the validity and completeness of the evidence with deliberation to discover how the evidence is perceived, misunderstood or ignored. We outline the opportunities and the problems derived from the use of digital communications, including social media, in this methodology, and emphasise the power of creative and innovative evidence visualisation and sharing in shaping policy.

Introduction

As the world struggles with complex problems that affect all aspects of human civilisation—from climate change and loss of ecosystems and biodiversity, to overpopulation, malnutrition and poverty, to disease, ill health and an ageing population—never before has it been more important to base government policy for intervention upon scientific evidence. In this article, we outline a methodology for integrating the process of scientific investigation with political debate and social discourse in order to improve the science–policy interface.

Science advisors and advisory bodies with scientist representation have steadily increased (Gluckman and Wilsdon, 2016 ); for example, in the UK in the form of the Food Standard Agency (FSA), the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) or globally within the commissions and advisory bodies associated with the United Nations and/or the use of technical review panels such as within The Global Fund to Fight Aids, Malaria and Tuberculosis. The well-established Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a model for other panels, such as the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. However, the process by which scientific evidence becomes part of a policy is complicated and messy (Gluckman, 2017 ; Malakoff, 2017 ), and there are many examples to support the view that this results in fundamental failings to deal quickly or effectively with major global challenges. For example, the time lag between the beginning of meaningful climate action in the COP21 Paris Agreement and the science that proved that greenhouse gas emissions are changing the climate, illustrates the difficulty of evidence-based policy making. It also questions the ultimate effectiveness of policy making, since there is evidence to suggest that COP21 may be too little, too late (Rockstrom et al., 2017 ). Similarly, the continued EU embargo on the use of food from genetically modified (GM) crops shows a serious disconnect between public opinion and the huge amount of scientific evidence that shows that the environmental and health risks are infinitesimal.

What is evidence?

The reasons for these apparent failures are complicated and numerous but one key issue is what constitutes evidence. Even when the problem is clearly one where science can provide a solution, evidence is not only derived from scientific investigation, but also from the political, cultural, economic and social dimensions of these issues, resulting in arguments about relative validity and worth. Hence, bias and prejudice are difficult to remove and evidence is often cherry-picked, only lightly consulted, partially worked into policy (if at all), and/or side-stepped in favour of ideological preferences. Even when evidence is abundant and clear, it is often ignored as we enter a ‘post-truth’ era where the opinions of experts are viewed with scepticism and populist solutions predominate (e.g., a 140 character tweet can brand a piece of sound scientific evidence as ‘fake news’). The ready availability and sharing of information through the internet and social media, which in some sense democratise evidence by increasing the diversity of inputs, should be a positive and welcome development. Condorcet’s mathematical Jury Theorem suggests that ‘larger groups make better decisions’ and that more, and diverse, input leads to better ‘collective intelligence’ (Condorcet, 1785 ). Thus, the increase in diverse information should foster ‘the wisdom of crowds’ (Surowiecki, 2005 ) towards ‘the better argument’ (Landemore and Elster, 2012 ). However, online content is personalised through the use of algorithms aimed to harvest and respond to existing preferences. Thus, the internet often fosters an ‘echo chamber’ effect that limits cognitive diversity and increases ‘group think’ by providing and linking information based solely on the entrenched preferences of the internet user and like-minded individuals (Grassegger and Krogerus, 2016 ). In addition, there is a view that scientific investigation is not clear, takes place outside the public sphere and often perceived as purposefully elitist. This gives rise to conspiracies about who produced the evidence and for what purpose, eroding epistemic authority. As a result, highly personalised preferences are reinforced by selective information, despite the fact that this information might amount to misinformation, exaggeration, falsehood and degraded or ‘cherry-picked’ evidence. Hence, rational policy development is thwarted because governments are tempted to use the evidence that concurs with the preconceived views of their constituents as well as their own existing political mantras, or which confirms public perceptions and aspirations, whether this mirrors the best available evidence or not.

The problem with scientific evidence

For scientists this is a particularly difficult problem to deal with. Science establishes facts, such as the fundamental physics proving that increasing levels of CO 2 in the atmosphere will result in an increased greenhouse effect. Even when proof is elusive (such as knowing exactly how, where and when this greenhouse effect will be translated into changes in climate) the notion of evidence is sacrosanct, it being derived from objective analysis, evaluation, testing, experimentation, retesting and falsifiability. To see hard won evidence ignored, distorted or diluted in favour of what seem ill-informed subjective views leads to frustration and anger. However, a more constructive and positive response would be to realise that the evaluation of scientific evidence cannot be divorced from the political, cultural and social debate that inevitably and justifiably surrounds most major issues. Using the two examples above, the long and sometimes tortuous pathway to the COP21 climate change accord results from the difficult economic trade-offs involved and the very different socio-political perspectives of the nations of the world. In the case of GM, the emotional context of food consumption that may favour natural foods cannot be treated dismissively, nor can the legitimate concerns about increased power and control that GM might give to multinational agri-businesses. As stated elsewhere (Cairney, 2016 ), scientific investigation defines problems, but often does not identify policy-acceptable, scalable and meaningful solutions. Scientists are often not effective in communicating their findings to audiences outside academia and frequently hold naive assumptions that good evidence will be readily accepted and can quickly contribute to policy. Not appreciating the complexity and non-linearity of many of the intractable problems that science is addressing (so-called wicked problems—DeFries and Nagendra, 2017 ) is often the root cause of this failure. Thus, the question often asked is can we improve the ways in which scientific evidence is constructed, integrated and communicated, so it can contribute more effectively, efficiently and quickly into policy formulation, in ways that combat the problems of a ‘post-truth’ era.

Producing evidence

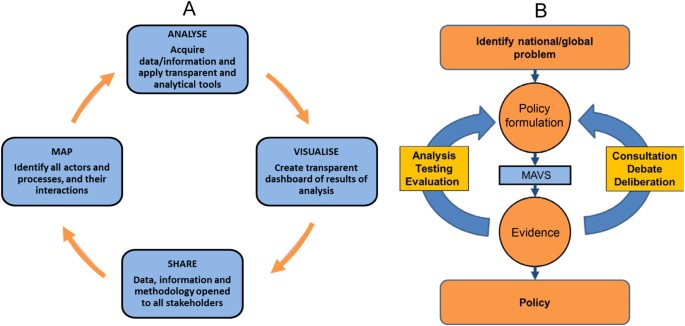

Ideas for a policy intervention follow identification of a particular societal problem and may be initiated by a variety of organisations—governments, agencies of government such as research funding bodies, political parties, pressure groups, NGOs, think-tanks or groups of concerned academics (Fig. 1 ). It may be top-down or bottom-up. This is then followed by the production of evidence about the operation, implementation and effectiveness of the policy idea, commissioned or carried out by the policy proposer. The process of evidence production normally follows a number of steps, which are depicted in Fig. 1A as a MAVS cycle—an iterative process of mapping, analysis, visualisation and sharing (Horton et al., 2016 ).

An integrated process for policy development. a MAVS—an iterative process for obtaining evidence for policy development. The first step is to map the component processes and participants in the issue, if appropriate as a system wide exercise. Then this issue is analysed using data and information and appropriate tools such as Life Cycle Assessment together with the tools of social science. The results of this analysis are then visualised in transparent form as a dashboard, ready for sharing among all stakeholders and when appropriate through publication in academic journals and/or news media. The data produced might well identify other dimensions of the issue and initiate further cycles. b Identification of a problem or opportunity that requires a policy intervention is put on the agenda. The first task to assemble evidence using the MAVS protocol. This evidence is evaluated using a two-pronged process, independent scrutiny and testing of the evidence and use of deliberative forums to address key issues arising. Repetition of this process will lead to a policy ready for implementation

The usefulness of formalising evidence generation in this way was demonstrated in addressing a specific policy question of how to reduce the environmental impact of the production of bread (Goucher et al., 2017 ; Horton, 2017 ). Mapping identified all the key actors in the wheat-bread supply chain, from whom data was obtained. This complete data set was then analysed by a standardised process of Life Cycle Assessment. The evidence clearly showed the dominant contribution of fertiliser as a source of greenhouse gas emissions—which was presented in easily visualised form, and shared via publication in a peer-reviewed academic journal (Goucher et al., 2017 ), press releases and a summary article in The Conversation (Horton, 2017 ). These were widely read and discussed across a wide variety of media. The evidence was subsequently taken up by commercial bodies in the wheat-bread industry who are now seeking ways towards a ‘sustainable bread’.

We suggest that the MAVS methodology could be similarly useful in evidence gathering for many other policy purposes. In such cases the evidence might be much more complex than in the above example, because policy more often than not is addressing complex multidimensional wicked problems rather than purely technical ones. One challenge is how to integrate scientific evidence, which is usually quantitative data, with the qualitative data obtained by social sciences. For this, further development of social indicators is crucial, including indicators of well-being, values, agency and inequality (Hicks et al., 2016 ). Furthermore, what is being suggested here is that evidence production should not be limited to only presenting analytically coherent statements about ‘facts’, ‘truth’ and ‘solutions’. Thus, evidence also needs to be generated in direct response to existing preferences as a means to either support or falsify preferences in a way that speaks to them, not over them. Here, interdisciplinary incorporation of social science techniques adds to the scientific data by providing stakeholder analysis, preference identification and social categorisation.

Lessons could be learned from recent experiments aimed to increase health policy outcomes associated with the production of evidence by means of participatory research models, which incorporate stakeholders into the design (mapping), evaluation (analysis), communication (visualisation and sharing) and implementation phases of research. By doing so, several unique features result. Firstly, stakeholders are able to provide ‘on the ground’ insights about the problems or misunderstandings the research needs to address. Hence the research questions are tailored to these needs and the final aims of the research made transparent. Secondly, by including stakeholders throughout the process, it creates ‘buy-in’ and better understanding of how the evidence was created, increasing epistemic authority while undermining conspiratory speculation and claims of elitism. Thirdly, inclusion naturally builds trust in the results, which in many cases in health research has allowed for better policy translation and outcomes, since people are more willing to adopt the rationale for a policy if they feel that they were involved in the process. As an example, positive policy results have been witnessed in a number of cases where health research linked circumcision to reduced rates of HIV infection in Africa. Although it is still a highly contentious issue in many parts of the world, the inclusion of political, religious and cultural leaders in the research process in many cases helped to alleviate existing fears and misunderstandings, which facilitated more exact communication and acceptance of the source of evidence (WHO, 2016 ).

Visualisation and sharing are particularly important steps of the MAVS process. All too often, evidence production and analysis results in lengthy and often impenetrable reports, which make the process of transparent evidence sharing impossible and often counter-productive. For example, Howarth and Painter ( 2016 ) describe the problems translating the information contained in IPCC reports into local action plans. Thus, research is urgently needed to find the best ways to visualise and then communicate evidence, for example, using clever infographics and other digital techniques. There is huge potential for evidence sharing via web-based national and international events and new online publishing models (e.g., Horton, 2017 ). Most important of all, people with expert knowledge need to be active and pro-active rather than passive and reactive; indeed one might argue they have a responsibility to do so. Jeremy Grantham, founder of the philanthropic Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment once stated ‘Be persuasive. Be brave. Be arrested (if necessary)’ (Grantham, 2012 ). Sharing of experience and approaches is also vital, to find out what works and what doesn’t, creating networks if appropriate, such as the International Network of Government Science Advice (INGSA) or less formal and spontaneous movements such as that which resulted in the March for Science. Supplementing evidence with powerful stories from ‘real life’ can also increase the effectiveness of communication. One key implication here is that what may previously have been regarded as research (in a university for example) may become an activity in which the end result, in terms of impact, advocacy and implementation, is not just an optional ‘add-on’ but an integral and obligatory part of the project.

Evaluating evidence

The next step in our methodology is evidence evaluation. This is an open and transparent process that questions the validity of the evidence. Who leads this evaluation process will depend upon who is leading the policy initiative. Given their reputation for impartiality, transparency and interdisciplinary thinking, universities could play a key independent role, so long as they have procedures to include all stakeholders, particularly those directly affected by a policy intervention. This is not always straightforward, especially when research depends upon funding by governments and various external bodies. The key is to break away from the traditional model of the ‘expert panel of mostly white male senior academics’ and strive towards diversity of experience, ethnicity and gender. Again, the criterion for such assessment is not to produce an impenetrable report, but to follow the principles of visualisation and sharing set out above.

Evidence evaluation simultaneously and equally combines discussion, debate and deliberation with testing of that evidence in further independent scientific scrutiny, including using peer review procedures well known for academic science (Fig. 1B ). Evidence from scientific investigation rarely constitutes proof and furthermore does not always meet high standards of objectivity, quality or neutrality. Therefore, it has to be independently assessed, including by consideration of evidence available from other sources and studies. Within the evaluation process it is important to locate not only where evidence is lacking or is inconclusive or ambiguous, but also to understand how evidence is perceived, misunderstood or ignored. Thus, for example, the same piece of evidence can be interpreted in different ways by different stakeholders, leading to disagreement and conflict (discussed in Horton et al. 2016 ). These then become focal points in deliberative forums that consider the tension between different actors and stakeholders.

The use of stakeholder deliberative forums within the evidence policy process not only allows for misconceptions and ideological stances to be located and understood, but also provides deliberative opportunities for various ideological positions to be held to public scrutiny by other stakeholders. Stakeholders with particularly entrenched preferences are asked to share these preferences and give their best defences and evidence to support them. This includes having stakeholder positions tested against the best evidence available and mutual requests of reason giving from other stakeholders. Deliberative forums help to undermine enclave thinking and force ideology testing via the need for public reason giving. They have had empirical success in creating intersubjective meta-understandings between stakeholders, which over time, allow crucial agreements on key factual elements within contested public policy.

There are already many cases of governments instituting deliberative forums for key policy discussions, in efforts to generate policy consensus, rather than relying on aggregative preference tallying models that only measure existing preferences and pit them against each other in simplistic minority/majority binaries. For example, there have been successful deliberative experiments trialled by the Western Australian Department of Planning and Infrastructure, in British Columbia’s ‘Citizens Assembly’, in Ireland during the Irish Constitutional Convention, and by Oregon State in its ‘Initiative Review’ (Rosenberg, 2007 ).

Although deliberative forums have largely been physical meetings facilitated by researchers, governments or experts, the use of the internet to broaden the scope of deliberative forums could hold promising innovation. This could allow much wider participation and larger sets of data to be collected and evaluated, aided by the use of artificial intelligence techniques. This is an area to which future research should be directed (Neblo et al., 2017 ).

Transforming knowledge into policy

The results of this two-pronged evaluation are viewed together in the process by which the evidence associated with a policy idea is transformed into a policy plan, as depicted in Fig. 1B . The policy plan can then be evaluated again, and again, step-by-step until all evidence has been validated and all stakeholder viewpoints have been reasonably satisfied or properly discredited. The policy is then ready for implementation. The anticipation here is that stakeholder ‘buy-in’ will remove barriers to policy implementation and that the use of evidence within these deliberations shape that ‘buy-in’. This is because, although politicians could still ignore evidence-based policy consensus, they would have less incentive to do so if that consensus demonstrated a clear ‘buy-in’ by key stakeholders and the public. In addition, deliberative forums often involve policy makers as key participants and thus can deliver preference alteration, particularly if they are aligned at the same time as other constituent stakeholders.

Can the methodology we describe have an effect on the development of evidence-based policy in general? Combining scientific analysis, participation and deliberation among multiple stakeholders, has been proposed to address the problem of water sustainability (Garrick et al., 2017 ), food security (Horton et al., 2017 ) and health (Lucero et al., 2018 ), and it is in such domains that we foresee it being particularly applicable. However, in many cases the full complexity and messiness of the problem may make strict adherence to this methodology difficult, and here evidence sharing through advocacy, stakeholder outreach and campaigning becomes particularly important. Politicians often take note only when public pressure mounts, for example, because of intense activity in the popular press, as in the recent policy proposals in the UK surrounding plastic bottles, coffee cups and plastic pollution of the oceans. It is perhaps less clear whether our methodology can make impact in more politically charged policy areas such as climate change, where evidence is clear but vested interests, often through ‘post-truth’ and ‘fake news’ work to undermine it. Nevertheless, having a formal framework could be a source of stability, discipline and confidence building, a recourse when problems arise and a way to break through log jams and overcome barriers. By establishing trust between scientists, government and the public, it could help build a more effective science–policy interface.

Cairney P (2016) The politics of evidence-based policy making. Springer, London

Condorcet M (1785) On the application of analysis to the probability of majority decisions, condorcet: Political writings. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

DeFries R, Nagendra H (2017) Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science 356:265–270

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Garrick DE et al. (2017) Valuing water for sustainable development. Science 358:1003–1005

Gluckman P (2017) Scientific advice in a troubled world. http://www.pmcsa.org.nz/blog/scientific-advice-in-a-troubled-world/

Gluckman P, Wilsdon J (2016) From paradox to principles: where next for scientific advice to governments. Pal Commun. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.77

Goucher L, Bruce R, Cameron D, Koh SCL, Horton P (2017) Environmental impact of fertiliser embodied in a wheat-to-bread supply chain. Nat Plant. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.12

Grantham J (2012) Be persuasive. Be brave. Be arrested (if necessary). Nature 491:303

Grassegger H and Krogerus M (2016) The data that turned the world upside down. Motherboard. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/how-our-likes-helped-trump-win

Hicks CC et al. (2016) Engage key social concepts for sustainability. Science 352:38–40

Horton P (2017) We’ve calculated the environmental cost of a loaf of bread – and what to do about it. The Conversat. http://theconversation.com/weve-calculated-the-environmental-cost-of-a-loaf-of-bread-and-what-to-do-about-it-73643

Horton P et al. (2017) An agenda for integrated system-wide interdisciplinary agri-food research. Food Secur 9:195–210

Article Google Scholar

Horton P, Koh SCL, Shi Guang V (2016) An integrated theoretical framework to enhance resource efficiency, sustainability and human health in agri-food systems. J Clean Prod 120:164–169

Howarth C, Painter J (2016) Exploring the science–policy interface on climate change: The role of the IPCC in informing local decision-making in the UK. Pal Commun. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.58

Landemore H, Elster J eds. (2012) Collective wisdom: Principles and mechanisms. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lucero J et al. (2018) Development of a mixed methods investigation of processes and outcomes of community-based participatory research. J Mixed Methods Res 12:55–74

Malakoff D (2017) A matter of fact. Science 355:363

Neblo MA, Minozzi W, Esterling KM, Green J, Kingrette J, Lazer DMJ (2017) The need for a translational science of democracy. Science 355:914–915

Rockstrom J, Gaffney O, Rogeli J, Meinshausen M, Nakicenovic N, Schellnhuber HJ (2017) A roadmap for rapid decarbonisation. Science 355:1269–1271

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Rosenberg S (2007) Can the people govern: Deliberation, participation and democracy. Palgrave, New York, NY. http://www.participedia.net/en/browse/cases . For tracking of various ongoing deliberative initiatives, see

Surowiecki J (2005) The wisdom of crowds: How the many are smarter than the few. Abacus, London

WHO (2016) A framework for voluntary male circumcision: effective HIV prevention and a gateway to improved adolescent boys and mens health in Eastern and Southern Africa by 2021. World Health Organisation Policy Brief, Geneva. see http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/malecircumcision/vmmc-policy-2016/en/

Download references

Acknowledgements

PH thanks the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment for their generous support. We wish to thank many colleagues in the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures and the Sheffield Sustainable Food Futures group for the discussion.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures and Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

Peter Horton

School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Garrett W. Brown

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter Horton .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Horton, P., Brown, G.W. Integrating evidence, politics and society: a methodology for the science–policy interface. Palgrave Commun 4 , 42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0099-3

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2017

Accepted : 20 March 2018

Published : 17 April 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0099-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Indian rural development: a review of technology and society.

- Ravindra Verma

- Kratika Verma

- Prakash S. Bisen

SN Social Sciences (2024)

Valuation of inter-boundary inefficiencies accounting IoT based monitoring system in processed food supply chain

- Janpriy Sharma

- Mohit Tyagi

- Arvind Bhardwaj

International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management (2024)

Spanning the boundaries between policy, politics and science to solve wicked problems: policy pilots, deliberation fora and policy labs

- Ulrike Zeigermann

- Stefanie Ettelt

Sustainability Science (2023)

Content Analysis of American Network News Coverage of Prevention Strategies During the Initial Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Cary M. Cain

- Nipa Kamdar

- Patrick O’Mahen

Journal of General Internal Medicine (2023)

Extent of reference to science and the efficacy of coastal management policies: Insights from the Vietnamese Mekong Delta

- Nguyen Tan Phong

Journal of Coastal Conservation (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Literature as an Interpretative Method for Socio-Political Scenarios

- First Online: 27 August 2016

Cite this chapter

- Luigi Mastrangelo 6

Part of the book series: Studies in Systems, Decision and Control ((SSDC,volume 66))

1040 Accesses

The Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa explains the complex relationship between literature, politics and society, pointing out how literary works might prove an effective interpretative key of the socio-political scenarios, provided to submit them to a detailed and culturally appropriate analysis under a methodological perspective, as a form of a narrative based social simulation, of better quality, the more it proves the author’s writing skills, by which it is possible to date back to a wider and more plausible scenario analysis. Despite the paradox of “an activity that comes from loneliness, by an outcast”, literature arises from the social and political universe because its object, coming from an unraveling series of plots taken from real result of imagination or the combination of these two elements in different degrees, consists in situations and in social dynamics arising from the relationship between the characters. The works, in order to be properly interpreted, are to be contextualized, starting from the ideological issue that must be approached by two points of view, objective and subjective.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Among the works by Reyes, collected in 13 volumes (1955–1968), stand out in this respect La testimonianza di Juan Peňa (1930), Verità e Menzogna (1950). As Ambassador he travels in France, Spain, Argentina and Brasil.

Vargas Llosa ( 2005 , p. 10).

Besides to Cent ’ anni di solitudine (1967), it is useful to remember La mala ora (1962) and L ’ autunno del patriarca (1975). He was awarded the Nobel prize in 1982.

M. Vargas Llosa, Letteratura cit., p. 12.

Ibidem, p. 15.

The two writers have also in common the attempt to get into active politics: in 1947 Sartre founded with Rosenthal and Rousset the party called Rassemblement Démocratique Révolutionnaire, similarly destined to a negative election result.

M. Vargas Llosa, Letteratura quoted, pp. 16–17.

Sartre ( 1995 , p. 137).

Sciarra ( 2009 , p. 129).

It is the ambitious Bourgois gentleman of the play by Moliere performed the first time in 1670.

Sartre, J.P. Che cos ’ è la letteratura? Quoted, p. 20.

Ibidem, pp. 23–24.

In 1853, Leo Tolstoy asks to be transferred to Sevastopol to tell the Crimean War. In Anna Karenina’s adultery (1873–1877) there is all the conformism of Russian society.

Vargas Llosa, Letteratura quoted, p. 25.

See, among the others, Di Benedetto ( 1991 ).

Baretti defends against Voltaire’ attacks the Italian literature and the Shakespearean theater. From 1763 to 1765 he directed “La Frusta Letteraria”.

Translator of the Odyssey, Pindemonte is the addressee of the Foscolo’s Sepolcri dedicated note. This theme was also developed in a poem of the same title, but with a more private than patriotic enthusiasm belonging to Foscolo.

In the three tragedies of freedom ( La congiura de ’ Pazzi 1779, Virginia 1783, Timoleone 1784), Alfieri condemns the aristocracy’s submissiveness to tyranny.

Animator of “Il Caffe”, Pietro Verri also wrote the Dialogo sul disordine delle monete nello stato di Milano (1763) and le Osservazioni sulle torture.

Cesare Beccaria was also committed with Elements of public economy (1804).

With Ivanhoe (1820) Scott shows the reader Richard the lionhearted’s England. He writes in nine volumes the Life of Napoleon (1827).

Miguel de Cervantes has to flee to Italy for his involvement in a doubtful act of violence, for which he is sentenced to the cut of the right hand: he puts himself in the wake of the Cardinal Giulio Acquaviva, second son of the Duke of Atri and nephew of the Jesuit General Claudio, author of the Ratio studiorum .

James Joyce with the Dubliners written in 1914 offers a portrait of the public life of the city. For the author of Ulysses (1927) likelihood is a rigorous operation and it represents a need both ethical and aesthetic.

Marcel Proust is the author of a work, In Search of Lost Time (1913–1927), considered a stream of consciousness novel but instead more properly sociological, since it describes through the complex transition from the I to We the French society of the early twentieth century.

William Faulkner, Nobel in 1949, deals with the issue of the decline of the South in the scenario of the Secession, also recalling a distant family affair through Colonel Sartoris (1929).

Gustave Flaubert lives in Paris the 1848 Revolution. From Madame Bovary (1856–1857) develops the “bovarysm”, which sees the migration to the metropolis as an antidote to the monotony of the province.

Honoré de Balzac adds the “de” to his surname to elevate his bourgeois origins. He publishes in 1829 Les Chouans about the Vendee rebellion.

Vargas Llosa, Letteratura quoted, p. 34.

Ibidem, pp. 38–39.

The Philosopher from Castelvetrano dealt with, among the others, Manzoni and Leopardi (1920) and Vincenzo Cuoco (1927).

Francesco De Sanctis was appointed Minister of the Public Education from March 1861 to 1862 e still in 1878 and from 1979 to 1981. His History of the Italian literature is to be appreciated as a civil, cultural and spiritual path of the Italian People.

Gramsci ( 1974 , pp. 5–29).

Dizionario delle Opere della letteratura italiana , directed by A. Asor Rosa, Einaudi, 2 tt., Torino (2000) 2006.

Xingjang and Magris ( 2012 , p. 7).

Ibidem, p. 36.

Antiseri ( 2014 , p. 29).

Russi ( 2005 , p. 63).

Sciarra ( 2007 , p. 132).

Gadamer ( 1972 , pp. 508–509).

Antiseri, D.: I cattolici e la politica. Una diserzione che tradisce l’Italia, in “Corriere della Sera”, 9 ottobre 2014, p. 29

Google Scholar

Di Benedetto, A.: Tra Sette e Ottocento, Poesia, letteratura e politica, Dell’Orso, Alessandria (1991)

Gadamer, H.G.: Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzüge Einer Philosophischen Hermeneutik, Tübingen, 1955, Trad. it. Verità e metodo, Fabbri, Milano (1972)

Gramsci, A.: Letteratura e vita nazionale, pp. 5–29. Einaudi, Torino (1974)

Luporini, C.: Leopardi progressivo, Editori Riuniti, Roma, 2006, already in Filosofi vecchi e nuovi, Sansoni, Firenze (1947)

Mastrangelo, L.: Leopardi politico e il Risorgimento. Luciano, Napoli (2010)

Russi, L.: Il passato del presente. Rodolfo De Mattei e la Storia delle Dottrine Politiche in Italia, p. 63. Edizioni Scientifiche Abruzzesi, Pescara (2005)

Sartre, J.P.: An introducion of “Les Temps Modernes”, now in Che cos’è la letteratura? (original edition. Gallimard, Paris, 1947), Il Saggiatore, Milano, (1960), p. 137 (1995)

Sartre, J.P.: Questions de Méthode, in “Les Temps Modernes”, 1957, n. 139, pp. 338–417, then in J.P. Sartre, Critique de la Raison Dialectique, I.t., Paris, 1960, Italian translation by P. Caruso, pp. 15–139. Milano (1963)

Sciarra, E.: Gadamer e i criteri ermeneutici della comprensione sociale, in ID., Epistemologia e società. Popper, Wittgestein, Gadamer, Sigraf Edizioni Scienfiche, Pescara (2007)

Sciarra, E.: Il metodo dell’antropologia storica di Sartre, p. 129. Chieti, Sigraf Edizioni Scientifiche (2009)

Vargas Llosa, M.: Letteratura e politica, translated by R. Bovaia, p. 10. Passigli, Firenze (2005)

Xingjang, G., Magris, C.: Ideologia e letteratura, translated by Simona Polvani, p. 7. Bompiani, Milano (2012)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Communication Science, University of Teramo, Via R. Balzarini 1, 64100, Teramo, Italy

Luigi Mastrangelo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Luigi Mastrangelo .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, University of Chieti-Pescara “G. d’Annunzio", Chieti, Italy

Antonio Maturo

Department of Mathematics and Physics, University of Defence Faculty of Military Technology, Brno, Czech Republic

Šárka Hošková-Mayerová

"Alexandru Ioan Cuza" University of Iasi, Iasi, Romania

Daniela-Tatiana Soitu

Polish Academy of Sciences, Systems Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland

Janusz Kacprzyk

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Mastrangelo, L. (2017). Literature as an Interpretative Method for Socio-Political Scenarios. In: Maturo, A., Hošková-Mayerová, Š., Soitu, DT., Kacprzyk, J. (eds) Recent Trends in Social Systems: Quantitative Theories and Quantitative Models. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol 66. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40585-8_36

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40585-8_36

Published : 27 August 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-40583-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-40585-8

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Metaphor in Socio-Political Contexts

Current crises.

- Edited by: Manuela Romano

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: De Gruyter Mouton

- Copyright year: 2024

- Audience: Researchers in Cognitive Linguistics; Critical Socio-Cognitive Discourse Analysis; Discourse Analysis; Metaphor Theory

- Front matter: 6

- Main content: 334

- Illustrations: 2

- Coloured Illustrations: 28

- Keywords: Metaphor ; Socio-Political Contexts ; Critical ; Socio-Cognitive Approaches

- Published: May 6, 2024

- ISBN: 9783111001364

- ISBN: 9783111001258

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Defining Contemporary Art: How Have Socio-political and Economic Forces Shaped the Way We Look at, Create and Define Art in Our Times?

Related Papers

Marc James Léger

Julia Marshall

Rebecca Hamid

Globalisation, and what this means to art and the art world, has come to feature as one of contemporary art’s most signi cant conditions and fundamental concerns. Commentators widely acknowledge that contemporary art has been shaped by forces that continue to be dominated by international economic exchange. Enabled by globalisation, capitalist economies have nurtured and profited from a commodity-driven ‘spectacle culture.’The excesses of the art market and the exploitation of art as a commodity have manifested in ‘high art’ and ‘spectacularism.’

Contemporary Arts Across Political Divides

Alla Myzelev

ART-e-FACT. Journal for Contemporary Art & Culture

Larissa Buchholz

Willy Thayer

Apart from the longstanding and much-debated problem of art's commodification, how does neoliberalism transform and determine the conditions of artistic practice? Further, if neoliberalism is a substantially distinct stage in the history of capitalism, and not merely its intensification, what are the implications of this new condition for the practice and criticism of contemporary art? What does it mean to practice and theorize art, to be an artist or critic, under neoliberalism? Drawing on the central topic of this issue, is aesthetic, artistic, or political radicality in art still possible under the neoliberal condition? Can, or should, artistic practice constitute a significant site of resistance? Conversely, is the contemporary art world a paradigmatic case of, and even a model for, neoliberal capitalism?

Ulf Wuggenig

Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture

Terry Smith

An edited transcript of a colloquium between Terry Smith, Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory at the University of Pittsburgh, and Saloni Mathur, Associate Professor of the History of Art, University of California, Los Angeles, held at the Department of the History of Art and Architecture, University of Pittsburgh, on October 17, 2012.

RELATED PAPERS

ENRIQUE DANIEL ARCHUNDIA VELARDE

Jeyaseelan Augustine

Nutrition in Clinical Practice

Laura Matarese

Rev. chil. …

Manuel J Irarrazaval

Ciencia e Ingeniería

Livia Arizaga

Muscle & Nerve

Dirk Lehnick

Patrick Ilg

shahla kazemipour

Materials and Corrosion

Tom Sieverts

Journal of Catalysis

Miguel Banares

Software Quality Analysis, Monitoring, Improvement, and Applications

Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing

Ramy Nagah Eskander

Zita Ekeocha

Implementación de las estrategias didácticas mediadas por la tecnología.

Rafael D E J . Vázquez Mendoza

Solar & Wind Technology

Agnes Samuel

Cell Reports

Guy Beliveau

ikhsan yazi _ C1C021195

African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development

Folayo Aina

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Literature as a Reflection on Socio-political Realities: An Examination of Three Nigerian Writers

- Sikiru Adeyemi Ogundokun Osun State University, Osogbo, Nigeria.

Considering the degree of resemblance between literature and human societies, one is convinced that literature is not just a social construct which is rooted in mere ideas, imaginations or imaginary situations. Instead, it is a social institution; a form of tradition, which has existed for a long time and is accepted as a vital component of a given society to perform certain functions. In this paper, we see literature as a social reality, which presents the state of things as they are, rather than as they are imagined to be. In the selected literary works for this study, the three writers expose and condemn the harsh and hostile social and political realities which confront the African society at different periods of its evolution. Premised on sociological approach to literary criticism, this paper justifies that literature can be employed in working out national reconstruction being a tool that can make people co-operate with one another through information sharing and dissemination.

Author Biography

- Sikiru Adeyemi Ogundokun, Osun State University, Osogbo, Nigeria. Department of Languages and Linguistics.

Adeoti, G. and Elegbeleye, S. 2005. “Nigerian Literary Drama and Satiric Mode as Exemplified in Wole Soyinka’s Works”. In Perspective on Language and Literature, Olateju M and

Oyeleye L. ed. Intec Printers Ltd, Ibadan, p. 303 – 321.

Bakare, B. 2013. “Addressing youth unemployment in Nigeria”, The Punch Newspaper, Tuesday, November, Lagos, The Punch Publishers, p. 26.

Balzer, MM. 1995. “A State within a State: The Sakha (Yakutia)” in Kotkin, S. & Wolff, D. (eds.) Rediscovering Russia in Asia: Siberia and the Russia Far East, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, New York, p. 139-159.

Berthof, W. 1981. The Ferment of Realism. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. x-xi.

Coastes & Silbourn, R. 1983. Poverty: The Forgotten English Men, London, Penguin, p. 67

Darah, G G. 1987. The Punch., Lagos. The Punch Publishers, p. 7.

Faleti, A. 1972. Başòrun Gáà, Ibadan, Onibonoje Press & Book Industries (Nig.) Ltd.

Fatunde, T. 2002. La Calebasse Cassée. Ibadan, Bookcraft Ltd.

Irele, A. 1971. “The Criticism of Modern African Literature” in Perspective on African Literature”, Christopher Heywood (ed.), London, Heinemann, pp. 9 -24.

Mohuddin, Y. 1993. “Female Headed Household and Urban Poverty” in Felbre. Women’s worth in the World Economy, London, Macmillan, p. 48.

Ohai, C and Alasike, C. 2013. “Bad governance behind poverty in Nigeria”. The Punch Newspaper, Wednesday, October 23, Lagos, The Punch Publishers, p. 19.

Olusegun-Joseph, Y. 2006. “Song Motif As Postcolonial Resonance: Tanure Ojaide’s The Endless Song and The Fate of Vultures” in Ibadan Journal of European Studies, Ibadan, No. 6, p. 69-84.

Soyinka, W. 1984. A Play of Giants, Ibadan, Spectrum Books Ltd.

Vazquez A S. 1973. “Art and Society” in Essays in Marxist Aesthetics. New York. Monthly Review Press, p. 30.

Wellek, R and Warren, A. 1968. Theory of Literature. London, Penguin Books, p. 228.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access ).

Similar Articles

- Mary Bhoke Douglas, Prof. Mildred A. Ndeda, Dr. Samwel Okuro, The Role of Kenya Police Force in South Nyanza between the Two World Wars (1914-1945) , Journal of Arts and Humanities: Vol. 8 No. 10 (2019): October

- Germán Bula, María Clara Garavito, Innerarity and Immunology: Difference and Identity in selves, bodies and communities , Journal of Arts and Humanities: Vol. 2 No. 2 (2013): March

- Yanuaris Frans Manunuembun, Abdul Rachmad Budiono, Abdul Madjid, Bambang Sugiri, Political Party’s Vicarious Liability in Political Corruption Cases in Indonesia , Journal of Arts and Humanities: Vol. 9 No. 6 (2020): June

- Njeri Chege, Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Meaning of Male Beach Worker-Female Tourist Relationships on the Kenyan Coast , Journal of Arts and Humanities: Vol. 6 No. 2 (2017): February

- Rahman Taufiqrianto Dako, Mr. Suhandano, Anna Marrie Wattie, Philosophical Values in Traditional Procession of ‘Motolobalango’ in Gorontalo Society , Journal of Arts and Humanities: Vol. 6 No. 4 (2017): April

- Martin Adi-Dako, Emmanuel Antwi, Ghanaian Indigenous Sculpture through the Ghanaian Cultural Lens , Journal of Arts and Humanities: Vol. 3 No. 11 (2014): November