Advertisement

Customer experience: fundamental premises and implications for research

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 13 January 2020

- Volume 48 , pages 630–648, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Larissa Becker 1 &

- Elina Jaakkola 1

111k Accesses

372 Citations

23 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Customer experience is a key marketing concept, yet the growing number of studies focused on this topic has led to considerable fragmentation and theoretical confusion. To move the field forward, this article develops a set of fundamental premises that reconcile contradictions in research on customer experience and provide integrative guideposts for future research. A systematic review of 136 articles identifies eight literature fields that address customer experience. The article then compares the phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions prevalent in each field to establish a dual classification of research traditions that study customer experience as responses to either (1) managerial stimuli or (2) consumption processes. By analyzing the compatibility of these research traditions through a metatheoretical lens, this investigation derives four fundamental premises of customer experience that are generalizable across settings and contexts. These premises advance the conceptual development of customer experience by defining its core conceptual domain and providing guidelines for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Online influencer marketing

Research in marketing strategy

Customer engagement in social media: a framework and meta-analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For the past decade, customer experience has enjoyed remarkable attention in both marketing research and practice. Business leaders believe customer experience is central to firm competitiveness (McCall 2015 ), and marketing scholars call it the fundamental basis for marketing management (Homburg et al. 2015 ; Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ). Such attention has also prompted calls for research (e.g., Ostrom et al. 2015 ) and special issues devoted to customer experience, with a resulting dramatic increase in academic publications pertaining to this concept across many different literature fields and significant advances in scholarly understanding.

Yet this trend has also produced considerable fragmentation and theoretical confusion. No common understanding exists regarding what customer experience entails. Some studies assert that customer experience reflects the offerings that firms stage and manage (Pine and Gilmore 1998 ), but others define it as customer responses to firm-related contact (Homburg et al. 2015 ; Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ; Meyer and Schwager 2007 ). The concept has been used to describe anything from extraordinary (Arnould and Price 1993 ) to mundane (Carú and Cova 2003 ) experiences. Some researchers delimit the scope of customer experience to a particular context, such as service encounters (Kumar et al. 2014 ) or retail settings (Verhoef et al. 2009 ), and others view it more broadly as emerging in customers’ lifeworlds (Chandler and Lusch 2015 ; Heinonen et al. 2010 ).

The lack of a unified view creates considerable challenges for theory development (Chaney et al. 2018 ; Kranzbühler et al. 2018 ). The diverse conceptualizations of customer experience mean that its operationalization differs from study to study, creating measurement and validity concerns. Confusion also prevails about the scope and boundaries of the customer experience construct, its antecedents, and its consequents. Researchers have difficulty defining which insights they can combine, thus limiting replication and generalization across contexts. These challenges also hinder researchers’ ability to disseminate meaningful implications for managers seeking to foster superior customer experience.

To mitigate these challenges and move the field toward a more unified customer experience theory, an integrative understanding is needed. With this article, we seek to develop a set of fundamental premises that reconcile contradictions and dilemmas in the current customer experience literature and provide integrative guideposts for future research in the field . As integrating such fragmented research requires understanding the distance between the phenomena addressed by different studies as well as the degree of compatibility in their underlying assumptions (Okhuysen and Bonardi 2011 ), we pose two research questions to guide our efforts: (1) What is the nature of the customer experience phenomenon and the underlying metatheoretical assumptions adopted in literature that addresses customer experience? (2) What are the common elements of customer experience that are applicable across contexts and literature fields?

To address these questions, we started with a systematic literature review to identify customer experience research in eight key literature fields: services marketing, consumer research, retailing, service-dominant (S-D) logic, service design, online marketing, branding, and experiential marketing. We then analyzed the compatibility of these fields with a metatheoretical approach, which supports comparisons across fragmented, scattered literature pertaining to a particular concept (Gioia and Pitre 1990 ; Möller 2013 ). On the basis of this comparison, we integrated these eight fields into two higher-order research traditions, defined by their approach to customer experience as either (1) responses to managerial stimuli or (2) responses to consumption processes. Through these analyses, we explicate the underlying assumptions of each research tradition and also provide a state-of-the-art description of how customer experience has been studied so far.

Furthermore, we identify commensurable elements that are applicable to both research traditions and across contexts to define four fundamental premises of customer experience that provide solutions to problems in the current research on this concept. These premises provide an integrative definition of customer experience, reveal a multilevel and dynamic view of the customer journey, highlight contingencies for customer experience, and determine the role of the firms in influencing customer experience. Each fundamental premise offers guidelines for future research as well as managerial practice. Our delineation of the conceptual domain of customer experience advances research by reconciling contradictions found in the literature and bridging different research fields and traditions, allowing them to speak the same language, and offering a more comprehensive view of the phenomenon (MacInnis 2011 ). This view complements existing reviews of customer experience (Table 1 ) that tend to focus on narrowly selected sets of articles, that seldom consider the metatheoretical underpinnings of the reviewed studies, and that do not integrate the dispersed studies. The fundamental premises proposed herein can support more rigorous studies, whose results will have more meaningful implications for firms.

The next section presents our research approach, followed by the results of the metatheoretical analysis, including a description of the key phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions embodied in each literature field, as well as a derived theoretical map of customer experience in marketing. Subsequently, we develop four fundamental premises of customer experience by integrating compatible assumptions across research traditions. In the conclusion, we detail the theoretical contributions and managerial implications of this study, as well as its limitations.

Research approach

Developing an integrative view of customer experience requires organizing the scattered literature into groups and analyzing their compatibility (MacInnis 2011 ). This analysis involved three phases: (1) a systematic literature review of customer experience that groups individual studies into eight distinct literature fields, (2) organization of the eight literature fields into two distinct research traditions on the basis of the customer experience phenomena addressed and the underlying metatheoretical assumptions adopted, and (3) forming an integrated view of customer experience by building on the compatible elements across research traditions.

Phase 1: identifying and grouping relevant customer experience research

We conducted a systematic literature review to select relevant articles that study customer experience in marketing, according to strict guidelines (e.g., Booth et al. 2012 ; Palmatier et al. 2018 ). A systematic literature review enables overcoming possible biases in comparison to traditional reviews because it uses explicit criteria and procedures for selecting and including articles in the sample (e.g., Littell et al. 2008 ). We identified 142 articles that we subjected to a two-step process: identification of literature fields and classification of the articles (see Appendix 1 ).

We started with four literature fields—S-D logic, consumer research, services marketing, and service design—that were previously identified as relevant domains for customer experience research (Jaakkola et al. 2015 ). When the articles did not fit these fields in terms of their primary research foci (the aspects of customer experience studied), we added a new category, ultimately resulting in four additional literature fields: retailing, online marketing, branding, and experiential marketing. For example, branding emerged as a clearly distinct field that focuses on brand stimuli, such as logo and packaging (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009 ).

We then classified the articles into these literature fields according to three criteria: the primary customer experience stimuli studied, the customer experience context, and the key references used to define customer experience (e.g., citing Arnould and Price ( 1993 ) to substantiate the definition of customer experience indicates an article is likely to belong to the literature field of consumer research) (Table 2 ).

To be classified into a specific literature field, an article had to meet at least two of these three criteria without considerable overlap between fields. We excluded 12 articles that did not fulfill these criteria. However, we added 6 additional papers, identified through a bibliography search (i.e., back-tracking) (Booth et al. 2012 ; Johnston et al. 2018 ), resulting in a total sample of 136 articles (see Web Appendix ). The iterative process of reading the articles, identifying the literature fields, and classifying the articles stopped when we reached theoretical saturation (i.e., the majority of articles could clearly be categorized in one of the fields).

Phase 2: Analyzing the nature of the customer experience phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions in the literature fields

Following Okhuysen and Bonardi ( 2011 ), we analyzed these eight literature fields in terms of the focal phenomena addressed and the ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions adopted (Table 3 ) (see Appendix 2 for a more detailed account of the analysis). Using these elements, we compared the literature fields and sought to identify broader groups. By situating the eight literature fields in a theoretical map, we could navigate across them and develop conclusions about their compatibility (Gioia and Pitre 1990 ; Möller 2013 ; Okhuysen and Bonardi 2011 ). In turn, we identified two distinct research traditions that encompass all eight literature fields.

Phase 3: Developing an integrated view of customer experience

To integrate the two research traditions, we used a method analogous to triangulation (Gioia and Pitre 1990 ). By juxtaposing the two research traditions from a metatheoretical perspective, we sought to identify customer experience elements that are common to the two traditions, distinct yet compatible elements, and unique elements that do not fit with the assumptions from the other research tradition (Gioia and Pitre 1990 ; Lewis and Grimes 1999 ). The integration of compatible elements resulted in the development of four fundamental premises of customer experience.

Results of the metatheoretical analysis

In this section, we first describe the nature of the phenomena addressed and the metatheoretical assumptions adopted in the customer experience literature. We then position each literature field on a theoretical map of customer experience to establish two higher-order research traditions.

Customer experience phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions in the literature fields

Table 4 presents the description of the key customer experience phenomena addressed and the metatheoretical assumptions adopted in the eight identified literature fields. A discussion on the similarities and contradictions between them follows (cf. Möller 2013 ; Okhuysen and Bonardi 2011 ).

Customer experience phenomena addressed

As Table 4 shows, there are considerable differences between the literature fields with regard to the scope and nature of customer experience as a research phenomenon. The literature on experiential marketing tends to view experience as the offering itself. However, the most prevalent view within other fields sees customer experience as a customer’s reactions and responses to particular stimuli. Some studies focus on customer responses to stimuli residing within the firm–customer interface , with the goal of understanding how firms can use different types of stimuli to improve customers’ responses along their customer journey, the series of firm- or offering related touchpoints that customers interact with during their purchase process (e.g., Patrício et al. 2011 ). For example, services marketing focuses on service encounter stimuli, such as the servicescape, employee interactions, the core service, and other customers (e.g., Grace and O’Cass 2004 ), the retailing literature focuses on retail elements, such as assortment and price (e.g., Verhoef et al. 2009 ), and online marketing focuses on the elements of the virtual environment (e.g., Rose et al. 2012 ).

In contrast, S-D logic and consumer research consider stimuli related to the customer’s overall consumption process , encompassing factors beyond dyadic firm–customer interactions (e.g., Chandler and Lusch 2015 ; Woodward and Holbrook 2013 ). These studies consider customer experience to also emerge through non-market-related processes (e.g., eating dinner at home; Carú and Cova 2003 ), affected by a range of stakeholders such as customer collectives (Carú and Cova 2015 ) and even institutional arrangements such as norms, rules, and socio-historical structures (e.g., Akaka and Vargo 2015 ).

Metatheoretical assumptions

In terms of the ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions present in the customer experience literature, our analysis reveals some clear divides (Table 4 ). On a general level, services marketing, retailing, service design, online marketing, branding, and experiential marketing assume that particular stimuli likely trigger a certain response from customers. Thus, their view resonates with the idea of an objective, external, concrete reality (Burrell and Morgan 1979 ). Researchers employ hypothetic–deductive reasoning to study the relationship between customer experience and other variables, typically with surveys and experiments (e.g., Srivastava and Kaul 2016 ). In theoretical models, contextual factors usually appear as moderating variables (e.g., Verhoef et al. 2009 ). These fields hence tend to adopt a positivist epistemological approach, seeking to explain an external, concrete reality by searching for regularities and causal relationships in an objective way (Burrell and Morgan 1979 ).

In contrast, consumer research and S-D logic take a subjective view and adopt an interpretive epistemology. Research in these fields sees the customer experience as embedded in each customer’s lifeworld and interpreted by that customer (Helkkula and Kelleher 2010 ). External reality does not exist but instead serves only to describe the subjective reality, which is a product of individual consciousness (Burrell and Morgan 1979 ; Tadajewski 2004 ). Neither S-D logic nor consumer research aims to generate universal, generalizable laws; instead, they seek to understand how customers in their unique situation experience an object (Addis and Holbrook 2001 ). Therefore, these researchers consider customer subjectivity, highlight the role of contextual factors, and prefer qualitative methods (e.g., ethnography, phenomenological interviews) (Schembri 2009 ). Most consumer research studies employ an interpretive and inductive approach that is used to capture the symbolic meaning of consumption experiences (Holbrook 2006 ). In S-D logic, empirical studies often adopt a phenomenological approach, aiming to understand how value emerges during service use in the customer’s context (Helkkula and Kelleher 2010 ).

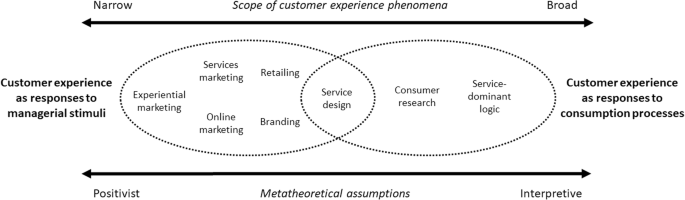

Theoretical map of the customer experience in marketing

The preceding discussion highlights that the scope of the customer experience phenomena addressed in the research ranges from narrow and dyadic to a broader ecosystem view. In terms of metatheoretical assumptions, we identify a continuum from more positivist to more interpretive approaches. Footnote 1 Our comparisons of these elements produced a theoretical map of customer experience where we group the eight literature fields into two higher-order research traditions (Fig. 1 ), which we define as groups of studies that share general assumptions about the research domain (Laudan 1977 ; Möller 2013 ).

Theoretical map of customer experience

The first research tradition combines experiential marketing, services marketing, online marketing, retailing, branding, and service design. These fields view customer experience as responses and reactions to managerial stimuli . As noted, each literature field addresses different stimuli; for example, brand-related stimuli include packaging, advertising, and logos (Brakus et al. 2009 ), whereas retailing elements include price, merchandise, and store facilities (Verhoef et al. 2009 ). The general goal across this research tradition is to examine how firms can affect customer experience by managing different types of stimuli, typically focusing on firm-controlled touchpoints. To test these relationships, researchers usually adopt a positivist philosophical positioning.

The second research tradition comprises consumer research and S-D logic that view customer experience as responses and reactions to consumption processes . This tradition adopts a broad view on experience as it addresses any stimuli during the entire consumption process, potentially involving many firms, customers, and stakeholders, all of which can contribute to the customer experience but are not necessarily under the firm’s control. Research following this tradition tends to see customer experience as embedded in a customer’s lifeworld and interpreted by the customer, such that it reflects an interpretive philosophical positioning (e.g., phenomenology). Finally, service design lies at the intersection of the two research traditions as it is inherently managerially focused but recent studies increasingly incorporate a more systemic view of stimuli for customer experience.

By building on the common elements across traditions and reconciling the distinct but compatible elements, we next develop fundamental premises of customer experience that provide opportunities to extend research within both traditions.

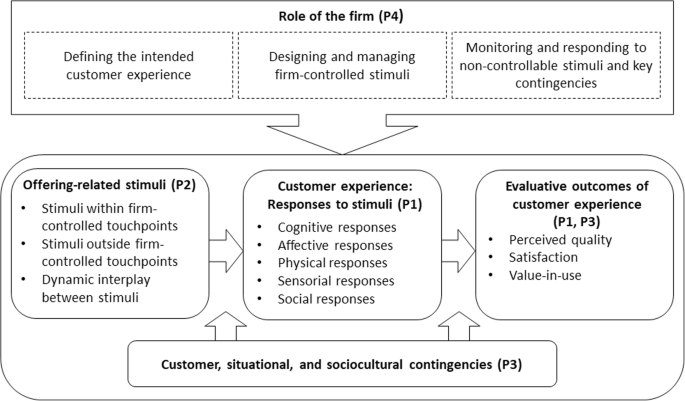

Fundamental premises of customer experience

Many authors highlight the need to build bridges across research traditions to establish a comprehensive understanding of a research domain (e.g., Gioia and Pitre 1990 ; Lewis and Grimes 1999 ; Okhuysen and Bonardi 2011 ). The pivotal question for developing a more unified customer experience theory is: To what extent can the literature from these two traditions be combined?

Our analysis revealed two research traditions that differ in terms of their metatheoretical assumptions, affecting how customer experience is understood and studied. A juxtaposition of these research traditions allows us to identify common elements, distinct yet compatible elements, as well as elements that are incompatible. From this analysis we developed four fundamental premises of customer experience that build on the shared assumptions and help in solving the key discrepancies in the extant literature. These premises may generalize across settings, allowing each research tradition to offer complementary results that collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of the same phenomena (cf. Gioia and Pitre 1990 ). Together, these premises (P1-P4) cover the “big picture” of what customer experience is, what affects it, its key contingencies, and the role that firms can play in it (Fig. 2 ). For each of these premises, we delineate guidelines for future research to move the field forward.

Conceptual framework for customer experience

Definition of customer experience

The metatheoretical analysis conducted revealed a myriad of definitions for customer experience that ultimately suggest different phenomena (see Table 4 ). The current literature on customer experience does not agree on the definition of customer experience nor on its nomological network. Confusion prevails as to whether experience is response to an offering (e.g., Meyer and Schwager 2007 ) or assessment of the quality of the offering (e.g., Kumar et al. 2014 ). This means that in some studies, customer experience overlaps with outcome variables such as satisfaction or value, while in others it is an independent variable leading to satisfaction, for example. Furthermore, some studies view experience as a characteristic of the product rather than as the customer’s response to it (e.g., Pine and Gilmore 1998 ), which is in deep conflict with the interpretive tradition that always views experience as a subjective perception by an individual and even as synonymous with value-in-use (Addis and Holbrook 2001 ).

To resolve this confusion, we suggest customer experience should be defined as non-deliberate, spontaneous responses and reactions to particular stimuli. This view builds on the most prevalent definition across the two research traditions, but separates customer experience from the stimuli that customers react to as well as from conscious evaluation that follows from it. This view rejects suggestions that evaluative concepts such as satisfaction or perceived service quality could be a component of customer experience (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ).

Another conceptual confusion in the extant literature relates to assumptions held regarding the nature of experiences. As Carú and Cova ( 2003 ) note, much of the marketing research assumes that good experiences are “memorable,” if not “extraordinary.” The extant research tends to treat ordinary and extraordinary experiences as different phenomena (e.g., Arnould and Price 1993 ; Klaus and Maklan 2011 ). However, these studies typically focus on the extraordinary or ordinary nature of the offering, such as river rafting or experiential events (Arnould and Price 1993 ; Schouten et al. 2007 ) or routine and mundane offerings (Carú and Cova 2003 ), rather than on the customer’s response to these stimuli. As customer responses can range from weak to strong (Brakus et al. 2009 ), we propose this intensity better marks the difference between an ordinary and extraordinary customer experience. It follows that this classification can be leveraged as a continuum instead of a dichotomy; the weaker the customer responses and reactions, the more ordinary the experience, and vice versa (cf. Carú and Cova 2003 ). A customer can thus have an extraordinary experience as a response to a mundane offering.

In sum, to reconcile confusion in the extant research, we propose the following:

Premise 1a:

Customer experience comprises customers’ non-deliberate, spontaneous responses and reactions to offering-related stimuli along the customer journey .

Premise 1b:

Customer experience ranges from ordinary to extraordinary representing the intensity of customer responses to stimuli.

Implications of Premise 1 for future research

Following Premise 1a, researchers should distinguish customer experience from stimuli (e.g., the offering) and evaluative outcomes (e.g., value-in-use). For example, when operationalizing customer experience, researchers should not build on evaluative scales or use satisfaction and service quality as proxies, as is currently often done (see, e.g., Kumar et al. 2014 ; Ngobo 2005 ). Instead, the operationalization of customer experience should focus on the customer’s spontaneous responses and reactions to offering-related stimuli. The current customer experience literature offers a few solid measures that can serve as a starting point for further development (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009 ; Ding and Tseng 2015 ). We recommend building the measures on the most common experience dimensions used in the extant research—cognitive, affective, physical, sensorial, and social responses (e.g., Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ; Schmitt 1999 ; Verhoef et al. 2009 )—to facilitate the accumulation of knowledge and eventually enable comparing the weight of each type of response across different contexts. The extant research implies that the relevance of different types of customer responses may vary across contexts (McColl-Kennedy et al. 2017 ), but a lack of a common definition and measures for customer experience has prevented building this knowledge effectively.

Defining customer experience as spontaneous responses and reactions suggests that the issue of timing is relevant for its measurement. According to our literature review, most studies use research instruments where the respondents have to rely on memory to report their experience (e.g., Trudeau and Shobeiri 2016 ). To improve the validity of the findings, we recommend research designs where customer responses are captured right after the interaction with the offering-related stimuli has taken place. Some methods and technologies for capturing customers’ reactions in real time have been developed, such as the real time experience tracking method (Baxendale et al. 2015 ) and wearable devices for emotion detection (Jerauld 2015 ). Surprisingly, none of the 136 studies in our review used such technology to investigate customer experience in real time. Future studies should further explore the applicability and consumer acceptance of such methods and technologies.

Following Premise 1b, researchers should also change the way they address extraordinary vs. ordinary experiences. The current literature tends to assume that the higher the score on a customer experience scale, the better the customer experience is (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009 ). Future studies should address contexts where ordinary experiences (i.e., weak or neutral responses) are desirable in order to complement current research that predominantly focuses on contexts where firms try to strengthen customers’ responses rather than to keep them to a minimum (e.g., Ding and Tseng 2015 ). Such studies would help firms in designing customer journeys that, at some points, minimize certain types of responses, while increasing particular responses at other times.

Stimuli affecting customer experience

Delineating the conceptual domain of customer experience also requires defining the stimuli that affect its formation. Key discrepancies in the current literature relate to the source of the stimuli considered and the level of analysis. Our review revealed that most studies focus on a particular set of firm-controlled touchpoints and an integrative view is missing. This is problematic in many respects: customer journeys in today’s markets are “multitouch” and multichannel in nature with new types of stimuli emerging every day, suggesting that firms need to understand a broad range of touchpoints within and outside firm control, both in offline and online settings (Bolton et al. 2018 ; Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ). Furthermore, empowered customers are increasingly in charge of selecting individual pathways to achieve their goals (Edelman and Singer 2015 ; Heinonen et al. 2010 ; Teixeira et al. 2012 ). This means that journeys become increasingly complex and individualized, and the current literature silos focusing on a selected set of stimuli and touchpoints will fail to capture what the customer really experiences. The literature fields that consider customers’ holistic experiences in their lifeworld take a broader view but lack precision and insight into how experiences related to particular offerings emerge.

To resolve this dilemma, we propose integrating the currently disparate perspectives into a multilevel framework that draws on different fields of the customer experience literature and considers the stimuli at multiple levels of aggregation: First, cues refer to anything that can be perceived or sensed by the customer as the smallest stimulus unit with an influence on customer experience, such as product packing and logo design (Bolton et al. 2014 ; Brakus et al. 2009 ). Second, touchpoints reflect the moments when the customer interacts with or “touches” the offering (Patrício et al. 2011 ; Verhoef et al. 2009 ). These contact points can be direct (e.g., physical service encounters) or indirect (e.g., advertising) and comprise various cues (Meyer and Schwager 2007 ). Third, the customer journey comprises a series of touchpoints across the stages before, during, and after service provision (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ; Teixeira et al. 2012 ). Fourth, the consumer journey level captures what customers do in their daily lives to achieve their goals, implying a broader focus than that of the customer journey and accommodating consumer interaction with multiple stakeholders beyond touchpoints with a single firm (Epp and Price 2011 ; Hamilton and Price 2019 ; Heinonen et al. 2010 ).

The extant literature has tended to measure customer experience either in one touchpoint or as an aggregate evaluation of the brand. However, recent research indicates a need for a more dynamic view: Kranzbühler et al. ( 2018 ) argue that customer experience is based on an evolving evaluation of a series of touchpoints, Bolton et al. ( 2014 ) suggest that some stimuli have multiplier effects, and Kuehnl et al. ( 2019 ) state that the connectivity of stimuli across touchpoints is an important driver for positive customer outcomes. These findings suggest that customer experience emerges in a dynamic manner and benefits from a multilevel analysis.

We present Premise 2 that addresses these shortcomings in the existing research and integrates insights across research traditions:

Premise 2a:

Customer experience stimuli reside within and outside firm-controlled touchpoints and can be viewed from multiple levels of aggregation.

Premise 2b:

Customer experience stimuli and their interconnections affect customer experience in a dynamic manner.

Implications of Premise 2 for future research

Premise 2 guides future research to study diverse offering-related stimuli through multiple levels of aggregation. Most of the reviewed research has examined a narrow scope of stimuli and touchpoints (e.g., Grace and O’Cass 2004 ) and a lack of insight into touchpoints beyond firm control is particularly glaring. We recommend cross-fertilization between the two research traditions: Researchers within the managerial research tradition could expand their research foci by drawing from consumption process studies that offer a broad outlook on the various stakeholders contributing stimuli that affect customer experience (e.g., Akaka and Vargo 2015 ; McColl-Kennedy et al. 2015 ). The research tradition focusing on experience as responses to consumption processes could adopt the more detailed analysis on journey composition offered by the managerial tradition and “zoom in” on the journey, focusing on the meanings that emerge at specific touchpoints, for example.

As extant studies often focus on measuring customer experience on the cue or touchpoint level (e.g., Grace and O’Cass 2004 ), the literature is unclear about how the interplay of diverse stimuli affect customer experience. Future research should thus study the interaction between types of stimuli and their dynamic effect on customer experience. Longitudinal research designs would be particularly useful for creating new insight into the evolving effects of stimuli configurations for the formation of customer experience as well as the interaction between the types of customer responses at different touchpoints. In addition, future research could investigate how the combination of responses and reactions that emerge over time lead to evaluative outcomes such as satisfaction.

The effective study on the emergence of customer experience necessitates the development of more dynamic measurement instruments. Current measures of customer experience often only provide a snapshot (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009 ; Ding and Tseng 2015 ). Considering the multitude of potential relevant customer experience stimuli and the active role of customers in forming their own journey (Edelman and Singer 2015 ; Heinonen et al. 2010 ), a possible avenue for research would be the development of self-adaptive scales or surveys where respondents can self-select parts of the journey that they found relevant and the types of responses they experienced. Research supporting the development of such instruments is available (e.g., Calinescu et al. 2013 ) but has not as yet been applied in the customer experience context. While a measurement instrument that captures a complete multilevel framework of the customer journey would become unmanageable, a self-adaptive scale would allow respondents to focus on touchpoints and even on specific cues that are the most relevant for the customer experience. A more dynamic measurement of customer experience would also enable analyzing what types of customer responses emerge in different touchpoints or phases of the customer journey.

Key contingencies for customer experience

Researchers generally agree that customer experience is subjective and specific to the context. This means that contextual variables related to the customer and the broader environment influence customer responses to stimuli and evaluative outcomes of customer experience. However, the current research on these contingencies is fragmented and lacks a uniform view. Within the managerial research tradition, the role of contextual variables is rather peripheral. These studies often investigate a limited number of contextual variables or dismiss their effect altogether. Some typical contextual variables that are studied include consumer attitudes, task orientation, and socio-demographic variables (e.g., Ngobo 2005 ; Verhoef et al. 2009 ). The research tradition that views customer experience as responses to consumption processes places a greater emphasis on the customer context, acknowledging the role of complementary offerings and service providers, institutions and institutional arrangements, and the customer’s goals in the consumption situation (Akaka and Vargo 2015 ; Tax et al. 2013 ; Woodward and Holbrook 2013 ).

Again, insights across research traditions have seldom been combined. To reconcile this shortcoming, we categorize the contingencies used in the extant studies and identify the key ways in which they operate. Our literature review enabled the identification of three groups: (1) customer, (2) situational, and (3) sociocultural contingencies. Customer contingencies refer to the customer’s characteristics such as personality, values, and socio-demographic characters (e.g., Holbrook and Hirschman 1982 ), resources such as time, skills, and knowledge (e.g., Novak et al. 2000 ), past experiences and expectations (e.g., Verhoef et al. 2009 ), customer participation and activities during the journey (e.g., Patrício et al. 2008 ), motivations (e.g., Evanschitzky et al. 2014 ), and the fit of the offering with the customer’s lifeworld (e.g., Schmitt 1999 ).

Situational contingencies are those related to the immediate context, such as the type of store the customer is interacting with (e.g., Lemke et al. 2011 ), the presence of other customers and companions (e.g., Grove and Fisk 1992 ; Schouten et al. 2007 ), and other stakeholders that contribute to the customer experience, such as other firms (e.g., Tax et al. 2013 ). Sociocultural contingencies refer to the broader system in which customers are embedded, such as language, practices, meanings (e.g., Schembri 2009 ), cultural aspects (e.g., Evanschitzky et al. 2014 ), and societal norms and rules (e.g., Akaka and Vargo 2015 ; Åkesson et al. 2014 ).

Our literature review indicates that these contingency factors can affect the customer experience through two alternative routes. First, these factors can make some stimuli more or less recognizable; in other words, they play the role of a moderator between offering-related stimuli and customer experience (Jüttner et al. 2013 ). Second, such contingencies can affect the evaluative outcomes of particular customer responses (Heinonen et al. 2010 ). For example, a feeling of fear can have negative effects in a dentist’s office, but in a context such as river rafting, that response may have positive implications (Arnould and Price 1993 ). Therefore, any particular response to offering-related stimuli is not “universally good” or “universally bad”; its evaluation instead depends on its fit with the customer’s processes and goals.

Altogether, this discussion organizes the fragmented literature around contingencies for customer experience, as summarized in Premise 3:

Customer experience is subjective and context-specific, because responses to offering-related stimuli and their evaluative outcomes depend on customer, situational, and sociocultural contingencies.

Implications of Premise 3 for future research

While the extant literature agrees on the subjective nature of experiences and recommends that managers ensure their customer experience stimuli have a good fit with the customer’s situational context (e.g., Homburg et al. 2015 ; Kuehnl et al. 2019 ), it does not offer much guidance on the identification and role of key contingencies for customer experience. More systematic research is thus needed on the relevant contextual variables and their effects on the strength and direction of the relationships between offering-related stimuli, customer experience, and evaluative outcomes. The extant empirical research has addressed a relatively narrow set of contextual contingencies, and new insights can be generated, for example, by drawing from research within the interpretative research tradition that has placed a strong emphasis on sociocultural factors beyond the firm–customer interface (e.g., Akaka and Vargo 2015 ; Åkesson et al. 2014 ). In particular, researchers could study the role of institutions and institutional arrangements, as they direct the customer’s attention to particular stimuli in the environment (Thornton et al. 2012 ), but are seldom studied as contingency factors in empirical research on customer experience. Future research could look beyond customer experience research to identify potentially relevant contingencies for customer experience formation.

Customer experience research is often preoccupied with the question of how to provide “good experiences,” simply assuming that higher scores on a customer experience scale are always better (e.g., Ding and Tseng 2015 ). As Premise 3 suggests, it is more relevant to ask for whom a particular experience is good . Future studies should aim to identify relevant key contingences that drive particular customer responses to stimuli and influence a customer’s evaluation of their responses. This insight will aid managers in developing a more individualized set of offering-related stimuli for their different target groups and user personas, which is deemed important in current markets (Edelman and Singer 2015 ).

Role of the firm in customer experience

The fourth premise seeks to settle a seemingly profound discrepancy between the two research traditions: Can firms manage the customer experience? Some studies refer to the customer experience as something created and offered to customers (e.g., Hamilton and Wagner 2014 ; Pine and Gilmore 1998 ), but others emphasize its emergence in customers’ lifeworlds and suggest it cannot be managed directly (Heinonen et al. 2010 ; Helkkula and Kelleher 2010 ). This discrepancy can be solved by building on the common ground of the two research traditions that sees customer experience emerging as customer responses to diverse stimuli. As firms cannot control customer responses, they cannot create the customer experience per se, but they can seek to affect the stimuli to which customers respond.

Studies within the managerial tradition provide guidance on designing and integrating stimuli in firm-controlled touchpoints to ensure positive customer experience (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009 ; Grace and O’Cass 2004 ; Pine and Gilmore 1998 ). Although this research tradition acknowledges that touchpoints outside the firm’s control (e.g., other customers) might greatly influence customer experience (e.g., Grove and Fisk 1992 ), it says very little about what firms can do regarding these stimuli.

Studies that view customer experience as responses to consumption processes offer some guidelines for addressing the uncontrollable touchpoints. For example, Carú and Cova ( 2015 ) advise firms to monitor and react to customers’ collective practices with other consumers. Tax et al. ( 2013 ) suggest that firms should identify other firms that are part of the consumer journey, then partner with these organizations to improve the overall customer experience. Some authors suggest that firms should try to identify all stakeholders that influence the customer journey (e.g., Patrício et al. 2011 ; Teixeira et al. 2012 ). Mapping offering-related stimuli as holistically as possible helps firms design offerings that better fit into customers’ lives (Heinonen et al. 2010 ; Patrício et al. 2011 ). Thus, firms can use their knowledge of external stimuli and contextual factors to their advantage, even though they cannot control such factors.

In sum, to reconcile the disparate streams of extant research, we propose the following:

Firms cannot create the customer experience, but they can monitor, design, and manage a range of stimuli that affect such experiences.

Implications of Premise 4 for future research

Only few attempts have been made to delineate what customer experience management entails (e.g., Homburg et al. 2015 ), and this topic remains insufficiently understood despite its practical relevance. The extant research offers some guidelines for “well-designed journeys” (e.g., Kuehnl et al. 2019 ), but more research is needed to specify management activities that are suited to different types of touchpoints.

According to our literature review, a particularly critical gap in extant knowledge relates to the firm’s possibilities of affecting touchpoints outside of the firm’s control. Service design research offers tools for mapping a broader constellation of touchpoints, but there is scant research on how firms can deal with touchpoints external to the firm–customer interface. Potential future research topics include, for example, how firms can design touchpoints that are adaptive to stimuli residing in external touchpoints and whether firms can influence how customers respond to stimuli at external touchpoints along their journey.

We recommend that future research should ground customer experience management models on a more nuanced conceptual understanding of experience. These models should not consider “good experience” as the goal of customer experience management, but instead define the content of the intended customer experience (cf. Premise 1). In our sample, only a few studies address the specific responses and reactions that firms want to trigger: For example, Bolton et al. ( 2014 ) show three types of intended experiences (e.g., emotionally engaged experiences) and give suggestions on how to trigger them. By focusing on the “good vs. bad” dichotomy of customer experience, studies about customer experience management seem to skip this important step and focus directly on the stimuli to which customers respond (cf. e.g., Lemke et al. 2011 ). A focus on intended responses and reactions would complement this research and provide more precise implications on the management of firm-controlled stimuli.

Another critical gap in the research knowledge on customer experience management relates to the issue of contextual factors. The effect of managerial action depends on how well it resonates with the customers, their situation, and sociocultural context (Heinonen et al. 2010 ); hence, insights into the environment where customers interact with the offering-related stimuli are critical. The extant knowledge on the relevance and fit of particular management activities with particular contexts, situations, and types of customers is very scarce. For example, future research could explore how customer contingencies for customer experience formation (see Premise 3) can be used in segmentation and how management processes should be adapted to ensure the desired effects.

Table 5 summarizes the developed premises that conceptualize customer experience as well as guidelines and suggestions for future research.

Conclusions

Theoretical contributions.

This study undertakes a rigorous development of an integrative view of customer experience, captured in four fundamental premises that can anchor future customer experience research. We highlight four specific conceptual contributions. First, this study differentiates the customer experience concept and the bodies of research that study it (MacInnis 2011 ) (Table 4 ). Then it defines two distinct research traditions that study customer experience: customer experience as responses to managerial stimuli and customer experience as responses to consumption processes (Fig. 1 ). This differentiation facilitates comparisons across research streams and creates the conditions for their integration (MacInnis 2011 ). The metatheoretical analysis makes different assumptions underpinning customer experience research visible and articulates the key differences between literature fields and research traditions, providing a state-of-the-art description of research in the customer experience domain (cf. Palmatier et al. 2018 ). This helps researchers make sense of the conflicting research findings in the previous literature, position their research, and take note of the conceptual boundaries of their chosen literature field.

Second, we integrate the customer experience literature and draw connections among entities, then provide a simplified, higher-order synthesis that accommodates this knowledge (MacInnis 2011 ). Specifically, our analysis provides four fundamental premises of customer experience that integrate common and distinct yet compatible elements across the previously distinct bodies of research, solving key conflicts in the existing research (Table 5 ). Previous literature reviews (Table 1 ) have highlighted differences across customer experience characterizations (Helkkula 2011 ), contextual lenses (Lipkin 2016 ), and theoretical perspectives (Kranzbühler et al. 2018 ), but our study is unique in that it seeks to transcend these individual differences and reconcile the disparate literature. The integration of extant knowledge in a conceptual domain is an important step for advancing science (Palmatier et al. 2018 ); it is particularly valuable for the fragmented customer experience domain hosting a great variety of definitions, dimensions, and analysis levels that create considerable challenges for researchers and hamper the conceptual advancement of the field (Chaney et al. 2018 ; Kranzbühler et al. 2018 ; McColl-Kennedy et al. 2015 ).

Third, the fundamental premises we propose delineate the customer experience concept; they “describe an entity and identify things that should be considered in its study” (MacInnis 2011 , p. 144). The proposed premises serve to reconcile and extend the research domain, as well as resolve definitional ambiguities (Palmatier et al. 2018 ), by delineating what customer experience is, what it is not, how it emerges, and to what extent it can be managed. We argue that the four premises establish the core of the conceptual domain of customer experience and are generalizable across settings and contexts. Few, if any, earlier studies have offered general guidelines for the rapidly growing field of customer experience research, let alone such that are based on a systematic, theoretical analysis of the body of experience research.

Fourth, this paper provides clear guidelines and implications for continued research on customer experience (Table 5 ). Each premise explicates the constituents and boundaries of the customer experience concept and what they mean for its study. We also explicate how researchers within each research tradition can enrich their studies by learning from previously somewhat overlooked experience research conducted within the other tradition.

Applying the premises developed in this study in continued research should facilitate the advancement of science and the generalization of the findings by enabling the different fields and research traditions to speak the same language and establish a more complete view of the conceptual domain. Naturally, customer experience researchers from various fields will continue to hold different assumptions about the nature of reality and how customer experience should be studied; however, these differences should not mean that the concept of customer experience means different things in the marketing literature. The integrative understanding offered in this study is the needed step toward the development of a more unified customer experience theory.

Managerial implications

A better delineation and integration of customer experience research also benefits managerial practice. We determine that customer experience comprises many types of customer responses and reactions that can vary in nature and strength (Premise 1). Instead of just seeking to create “positive” or “memorable” customer experiences, firms should define their intended customer experience with finer nuances. Depending on their value proposition, firms can determine which customer responses and reactions they hope to trigger. For some firms, a weak or mitigated response will be preferable for some touchpoints, such as a hassle-free cleaning service that the customer does not need to think about, or a dentist’s office that reduces excitement and fear. Other value propositions may aim to trigger strong, extraordinary emotional or sensorial experiences, as in the case of an amusement park (Zomerdijk and Voss 2010 ). Firms should thus develop unique customer experience measures to capture different types of customer responses. Using perceived quality or customer satisfaction as proxies to measure customer experience limits the understanding of the true nature of the customer experience that the offering evokes.

After establishing the intended customer experience, firms should map the consumer journey to identify which offering-related stimuli are likely to influence these customer responses and reactions. We propose an integrated view of versatile sources of stimuli along this journey, which is broader than what any single literature field can provide. A useful starting point would be to analyze offering-related stimuli at multiple levels of aggregation (Premise 2). Firms should be careful not to focus exclusively on individual touchpoints (e.g., a physical service encounter) or cues (e.g., website functionality) but rather should consider the multiplicity of and connectivity between stimuli and touchpoints customers encounter along their journeys. Such an effort may require collaborative collections of customer data with partners in the service delivery network. Ethnographic research can be used to understand stimuli in external touchpoints, and ultimately how offerings fits with customers’ lifeworlds. For example, Edvardsson et al. ( 2005 ) describe how IKEA designers observe customers in their houses, then create offerings that match those customers’ everyday experiences.

When mapping the consumer journey, firms should be aware that customer responses to stimuli also depend on customer, situational, and sociocultural contingencies (Premise 3). Therefore, customers in different situations and positions, with different resources, will likely react to particular stimuli in varied ways. Moreover, contextual factors may influence the evaluative outcomes of particular stimuli, such as the degree to which a particular reaction leads to satisfaction and loyalty. We urge firms to conduct customer research to learn about the connections among customer personas, usage situations, and responses to stimuli. These insights can be used as a basis for segmentation and to design different types of journeys for distinct customer types and situations.

Firms should also consider how norms, practices, and values in the customer’s context affect their experiences (cf. Akaka and Vargo 2015 ). Presenting offering-related stimuli that clash with such higher-order institutional arrangements will likely trigger strong reactions because they deviate from norms. The famous Benetton UnHate campaign is an example of an advertising stimulus that triggered strong affective and cognitive responses by creating surprising confrontations with prevailing institutions (cf. Hill 2011 ).

Determining intended customer responses and relevant stimuli for achieving them thus are prerequisites for managing customer experiences (Premise 4). The integrative view of customer experience offered in this study highlights the importance of both controllable stimuli (e.g., servicescape; Grace and O’Cass 2004 ) and those that exist outside the firm’s control (e.g., customer goals, ecosystems; Akaka and Vargo 2015 ). Firms should make an effort to design controllable touchpoints to facilitate the intended customer experience, but also develop methods to understand, monitor, and respond to stimuli their customers face in touchpoints that are beyond firm control. Firms can potentially adopt a facilitator role in some external touchpoints, for example, by providing platforms where customers can interact (e.g., Trudeau and Shobeiri 2016 ) or partnering with stakeholders that control external touchpoints (e.g., Baron and Harris 2010). Firms should constantly monitor the stimuli their customers confront in external touchpoints—for example in social media—and consider opportunities for adapting firm-controlled touchpoints accordingly, to leverage external stimuli supportive of the intended experience and mitigate stimuli causing dissonance.

Limitations

The results should be understood in light of some limitations. First, our systematic literature review did not capture studies that might address customer experience-related phenomena but that use different terminology or that focus on particular customer responses without connecting them to customer experience. However, the procedure of back-tracking articles reduced the risk of excluding seminal research on customer experience. Second, the decision to adopt strict criteria for article inclusion may have limited the results (e.g., excluding book chapters or papers published in languages other than English). Although this approach allowed us to analyze the 136 articles with greater rigor, we also acknowledge that the results may have differed if we had considered related concepts or adopted looser inclusion criteria. Despite these limitations, we are confident that the development of these fundamental premises of customer experience and their research implications will help scholars address this extremely important managerial priority.

We recognize that this is a simplistic division. We do not categorize researchers as positivists or interpretivists but approximate researchers’ assumptions as more positivist or more interpretive to varying degrees.

Addis, M., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). On the conceptual link between mass customisation and experiential consumption: an explosion of subjectivity. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 1 (1), 50–66.

Google Scholar

Akaka, M. A., & Vargo, S. L. (2015). Extending the context of service: from encounters to ecosystems. Journal of Services Marketing, 29 (6/7), 453–462.

Åkesson, M., Edvardsson, B., & Tronvoll, B. (2014). Customer experience from a self-service system perspective. Journal of Service Management, 25 (5), 677–698.

Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. L. (1993). River magic: extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (1), 24–45.

Baron, S. & Harris, K. (2010). Toward an understanding of consumer perspectives on experiences. Journal of Services Marketing, 24 (7), 518–531.

Baxendale, S., Macdonald, E. K., & Wilson, H. N. (2015). The impact of different touchpoints on brand consideration. Journal of Retailing, 91 (2), 235–253.

Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54 , 69–82.

Bolton, R. N., Gustafsson, A., McColl-Kennedy, J., Sirianni, N., & Tse, D. K. (2014). Small details that make a big difference: a radical approach to consumption experience as a firm’s differentiating strategy. Journal of Service Management, 25 (2), 253–274.

Bolton, R. N., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Cheung, L., Gallan, A., Orsingher, C., Witell, L., & Zaki, M. (2018). Customer experience challenges: bringing together digital, physical and social realms. Journal of Service Management, 29 (5), 776–808.

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review . London: Sage.

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73 , 52–68.

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis . Aldershot: Ashgate.

Calinescu, M., Bhulai, S., & Schouten, B. (2013). Optimal resource allocation in survey designs. European Journal of Operational Research, 226 , 115–121.

Carú, A., & Cova, B. (2003). Revisiting consumption experience: a more humble but complete view of the concept. Marketing Theory, 3 (2), 267–286.

Carú, A., & Cova, B. (2015). Co-creating the collective service experience. Journal of Service Management, 26 (2), 276–294.

Chandler, J. D., & Lusch, R. F. (2015). Service systems: a broadened framework and research agenda on value propositions, engagement, and service experience. Journal of Service Research, 18 (1), 6–22.

Chaney, D., Lunardo, R., & Mencarelli, R. (2018). Consumption experience: past, present and future. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 21 (4), 402–420.

Curd, M., & Cover, J. (1998). Philosophy of science: The central issues . New York: W. W. Norton.

Danese, P., Manfè, V., & Romano, P. (2018). A systematic literature review on recent lean research: state-of-the-art and future directions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20 (2), 579–605.

Ding, C. G., & Tseng, T. H. (2015). On the relationships among brand experience, hedonic emotions, and brand equity. European Journal of Marketing, 49 (7/8), 994–1015.

Edelman, D. C., & Singer, M. (2015). Competing on customer journeys. Harvard Business Review, 93 (11), 88–100.

Edvardsson, B., Enquist, B., & Johnston, R. (2005). Cocreating customer value through hyperreality in the prepurchase service experience. Journal of Service Research, 8 (2), 149–161.

Epp, A. M., & Price, L. L. (2011). Designing solutions around customer network identity goals. Journal of Marketing, 75 , 36–54.

Evanschitzky, H., Emrich, O., Sangtani, V., Ackfeldt, A., Reynolds, K. E., & Arnold, M. J. (2014). Hedonic shopping motivations in collectivistic and individualistic consumer cultures. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31 , 335–338.

Gioia, D., & Pitre, E. (1990). Multiparadigm perspectives on theory building. Academy of Management Review, 15 (4), 584–602.

Grace, D., & O’Cass, A. (2004). Examining service experiences and post-consumption evaluations. Journal of Services Marketing, 6 , 450–461.

Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: an organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85 (1), 1–14.

Grove, S. J., & Fisk, R. P. (1992). The service experience as a theater. Advances in Consumer Research, 19 , 455–461.

Hamilton, R., & Price, L. L. (2019). Consumer journeys: developing consumer-based strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 (2), 187–191.

Hamilton, K., & Wagner, B. A. (2014). Commercialised nostalgia: staging consumer experiences in small businesses. European Journal of Marketing, 48 (5/6), 813–832.

Heinonen, K., Strandvik, T., Mickelsson, K., Edvardsson, B., Sundström, E., & Andersson, P. (2010). A customer-dominant logic of service. Journal of Service Management, 21 (4), 531–548.

Helkkula, A. (2011). Characterising the concept of service experience. Journal of Service Management, 15 (1), 59–75.

Helkkula, A., & Kelleher, C. (2010). Circularity of customer service experience and customer perceived value. Journal of Customer Behavior, 9 (1), 37–53.

Hill, S. (2011). The reaction to Benetton’s pope-kissing ad lives up to the Christian stereotype. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2011/nov/20/benetton-pope-kissing-ad . Accessed 1 Nov 2018.

Hoffman, D. L., & Novak, T. P. (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing, 60 , 50–68.

Holbrook, M. B. (2006). Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: an illustrative photographic essay. Journal of Business Research, 59 , 714–725.

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (2), 132–140.

Homburg, C., Jozié, D., & Kuehnl, C. (2015). Customer experience management: toward implementing an evolving marketing concept. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (3), 377–401.

Jaakkola, E., Helkkula, A., & Aarikka-Stenroos, L. (2015). Service experience co-creation: conceptualization, implications, and future research directions. Journal of Service Management, 26 (2), 182–205.

Jain, R., Aagja, J., & Bagdare, S. (2017). Customer experience: a review and research agenda. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27 (3), 642–662.

Jerauld, R. (2015). United States patent no. US9019174B2. Retrieved from https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/e4/81/93/d8d10296bffeb1/US9019174.pdf . Accessed 1 Aug 2019.

Johnston, W. J., Le, A. N. H., & Cheng, J. M. S. (2018). A meta-analytic review of influence strategies in marketing channel relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (4), 674–702.

Jüttner, U., Schaffner, D., Windler, K., & Maklan, S. (2013). Customer service experiences: developing and applying a sequential incident laddering technique. European Journal of Marketing, 47 (5/6), 738–768.

Klaus, P., & Maklan, S. (2011). Bridging the gap for destination extreme sports: a model of sports tourism customer experience. Journal of Marketing Management, 27 (13–14), 1341–1365.

Kranzbühler, A., Kleijnen, M. H. P., Morgan, R. E., & Teerling, M. (2018). The multilevel nature of customer experience research: an integrative review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20 , 433–456.

Kuehnl, C., Jozic, D., & Homburg, C. (2019). Effective customer journey design: consumers’ conception, measurement, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 (3), 551–568.

Kumar, V., Umashankar, N., Kim, K. H., & Bhagwat, Y. (2014). Assessing the influence of economic and customer experience factors on service purchase behaviors. Marketing Science, 33 (5), 673–692.

Laudan, L. (1977). Progress and its problems: Towards a theory of scientific growth . London: University of California Press.

Lemke, F., Clark, M., & Wilson, H. (2011). Customer experience quality: an exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39 , 846–869.

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80 , 69–96.

Lewis, M. W., & Grimes, A. J. (1999). Metatriangulation: building theory from multiple paradigms. Academy of Management Review, 24 (4), 672–690.

Lipkin, M. (2016). Customer experience formation in today’s service landscape. Journal of Service Management, 27 (5), 678–703.

Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis . New York: Oxford University Press.

MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75 , 136–154.

McCall, T. (2015). Gartner predicts a customer experience battlefield. Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/customer-experience-battlefield/ . Accessed 1 May 2018.

McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Gustafsson, A., Jaakkola, E., Klaus, P., Radnor, Z. J., Perks, H., & Friman, M. (2015). Fresh perspectives on customer experience. Journal of Services Marketing, 29 (6–7), 430–435.

McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Danaher, T. S., Gallan, A. S., Orsingher, C., Lervik-Olsen, L., & Verma, R. (2017). How do you feel today? Managing patient emotions during health care experiences to enhance well-being. Journal of Business Research, 79 , 247–259.

Meyer, C. & Schwager, A. (2007). Understanding customer experience. Harvard Business Review, February, 1–12.

Möller, K. (2013). Theory map of business marketing: relationships and networks perspectives. Industrial Marketing Management, 42 (3), 324–335.

Möller, K., & Halinen, A. (2000). Relationship marketing theory: its roots and directions. Journal of Marketing Management, 16 (1–3), 29–54.

Ngobo, P. V. (2005). Drives of upward and downward migration: an empirical investigation among theatregoers. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 22 , 183–201.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D. L., & Yiu-Fai, Y. (2000). Measuring the customer experience in online environments: a structural modeling approach. Marketing Science, 19 (1), 22–42.

Okhuysen, G., & Bonardi, J. (2011). The challenges of building theory by combining lenses. Academy of Management Review, 36 (1), 6–11.

Ostrom, A. L., Parasuraman, A., Bowen, D. E., Patrício, L., & Voss, C. A. (2015). Service research priorities in a rapidly changing context. Journal of Service Research, 18 (2), 127–159.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 1–5.

Patrício, L., Fisk, R. P., & Falcão e Cunha, J. (2008). Designing multi-interface service experiences: the service experience blueprint. Journal of Service Research, 10 (4), 318–334.

Patrício, L., Fisk, R. P., Falcão e Cunha, J., & Constantine, L. (2011). Multilevel service design: from customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. Journal of Service Research, 14 (2), 180–200.

Pine II, B. J. & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 97–105.

Rose, S., Clark, M., Samouel, P., & Hair, N. (2012). Online customer experience in e-retailing: an empirical model of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 88 , 308–322.

Schembri, S. (2009). Reframing brand experience: the experiential meaning of Harley-Davidson. Journal of Business Research, 62 , 1299–1310.

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15 , 53–67.

Schouten, J. W., McAlexander, J. H., & Koenig, H. F. (2007). Transcendent customer experience and brand community. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35 , 357–368.

Shostack, G. L. (1982). How to design a service. European Journal of Marketing, 16 (1), 49–63.

Srivastava, M., & Kaul, D. (2016). Exploring the link between customer experience-loyalty-consumer spend. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31 , 277–286.

Tadajewski, M. (2004). The philosophy of marketing theory: historical and future directions. The Marketing Review, 4 (3), 307–340.

Tax, S. S., McCutcheon, D., & Wilkinson, I. F. (2013). The service delivery network (SDN): a customer-centric perspective of the customer journey. Journal of Service Research, 16 (4), 454–470.

Teixeira, J., Patrício, L., Nunes, N. J., Nóbrega, L., Fisk, R. P., & Constantine, L. (2012). Customer experience modeling: from customer experience to service design. Journal of Service Management, 23 (3), 362–376.

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Trudeau, H. S., & Shobeiri, S. (2016). Does social currency matter in creation of enhanced brand experience? Journal of Product and Brand Management, 25 (1), 98–114.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68 , 1–17.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 , 1–10.

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing, 85 (1), 31–41.

Woodward, M. N., & Holbrook, M. B. (2013). Dialogue on some concepts, definitions and issues pertaining to ‘consumption experiences’. Marketing Theory, 13 (3), 323–344.

Zomerdijk, L. G., & Voss, C. A. (2010). Service design for experience-centric services. Journal of Service Research, 13 (1), 67–82.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the colleagues from Turku School of Economics for commenting on earlier versions of this manuscript as well as the Editors and three Reviewers for their highly constructive and useful feedback.

Open access funding provided by University of Turku (UTU) including Turku University Central Hospital.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Turku School of Economics, Department of Marketing and International Business, University of Turku, 20014, Turku, Finland

Larissa Becker & Elina Jaakkola

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Larissa Becker .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mark Houston and John Hulland served as special issue editors for this article.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 47 kb)

Appendix 1: Conducting the systematic literature review

Figure 3 presents an overview of the systematic literature review process.

Systematic literature review process

After reading articles about customer experience to familiarize ourselves with the phenomenon and help us decide on the methodological procedures (Booth et al. 2012 ; Littell et al. 2008 ), we established the criteria for the systematic literature review. We searched articles in the EBSCO Business Source Complete and Science Direct databases with the following keywords, separated by the term “OR”: “experiential marketing,” “service experience,” “customer experience,” “consumer experience,” and “consumption experience.” One of these keywords had to be present in the title, abstract, or keywords (e.g., Danese et al. 2018 ). We conducted the search in early May 2016 and did not set any temporal limits.

In the screening phase, we excluded all articles that were written in a language other than English, were outside the marketing scope, were not published in peer-reviewed journals, and were editorials, comments, or repeated articles. Then, we evaluated the relevance of each article to our study according to three criteria, such that it had to (1) refer to business-to-customer or general customer experience, (2) include customer experience (or related terms) as a central concept (Danese et al. 2018 ), and (3) provide a definition and/or characterization of customer experience (Helkkula 2011 ). In applying these criteria, we first reviewed the title and abstract, and, if necessary, skimmed or read the full article (Booth et al. 2012 ; Littell et al. 2008 ). These processes resulted in 142 articles to be analyzed.

Appendix 2: Metatheoretical analysis

We used content analysis to analyze the articles (Booth et al. 2012 ), reading them in chronological order within each literature field. The first step involved extracting material from the articles and transferring it to a codebook (Littell et al. 2008 ). To increase coding objectivity, we developed a frame of reference with explicit detailed procedures and coding rules (Littell et al. 2008 ). The codebook included variables that operationalized the key elements of the metatheoretical analysis; that is, phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions (see Table 3 ). To code the articles, we constantly went back and forth between the studies being analyzed and the frame of reference.

In the second step, we extracted material from the codebook to describe the phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions. To analyze the phenomena , we grouped similar codes to form theoretical dimensions. These theoretical dimensions aided our understanding of what customer experience is and how it is characterized in each literature field. For the ontological , epistemological, and methodological assumptions , we counted instances of codes to describe the metatheoretical assumptions in each literature field (contextualizing according to the understanding obtained by reading articles in each literature field).

Next, we developed a theoretical map, which we defined as a spatial allocation of different literature fields according to particular theoretical criteria. The description and comparison of the phenomena and metatheoretical assumptions in each literature field (i.e., the theoretical criteria) resulted in two higher-order research traditions: customer experience as responses to managerial stimuli and customer experience as responses to consumption processes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Becker, L., Jaakkola, E. Customer experience: fundamental premises and implications for research. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 48 , 630–648 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00718-x

Download citation

Received : 04 July 2018

Accepted : 27 December 2019

Published : 13 January 2020

Issue Date : July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00718-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Customer experience

- Consumer experience

- Customer journey

- Literature review

- Metatheoretical analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

JCR Misconduct Policies: A Note from the Policy Board

Is Top Rated More Persuasive than Best Seller?

Report from the ACR Conference

The Consumption of Crowdfunding

JCR Inclusion Grants

Current Issue

Origin versus substance: competing determinants of disruption in duplication technologies, the value-translation model of consumer activism: how consumer watchdog organizations change markets, mysterious consumption: preference for horizontal (vs. vertical) uncertainty and the role of surprise, how political ideology shapes preferences for observably inferior products, when products come alive: interpersonal communication norms induce positive word of mouth for anthropomorphized products, wealth in people and places: understanding transnational gift obligations, distributions distract: how distributions on attribute filters and other tools affect consumer judgments, on or off track: how (broken) streaks affect consumer decisions, spending windfall (“found”) time on hedonic versus utilitarian activities, the magnitude heuristic: larger differences increase perceived causality, the network see all.

Consumer-Driven Memorialization

Consumer fascination with the past drives a diverse range of markets.

The Ferber Award 2022

JCR Best Paper 2021: An Author Interview

Crafting the Identity Politics of Consumption

Chalkboard: resources for teachers see all.

Consumer Culture Research in JCR: Our List

A collection for research and training, created by Zeynep Arsel, Markus Giesler, and Ashlee Humphreys.

Teaching a PhD Seminar?

Why Consumers Value Effort in Caregiving

Wordify: An Author Interview

The authors’ table see all.

How Do Same-Sex Couples Navigate Hysterisis?

Mobilizing Gendered Capital to Resolve Hysteresis

The Pursuit of Meaning

When a House is No Longer a Home

Donating Time versus Money

Editorial matters see all.

How Do We Evaluate JCR Papers?

At JCR, we broadly distinguish between five different types of papers, each requiring a slightly different approach.