- Health & Wellness

- Hearing Disorders

- Patient Care

- Amplification

- Hearing Aids

- Implants & Bone Conduction

- Tinnitus Devices

- Vestibular Solutions

- Accessories

- Office Services

- Practice Management

- Industry News

- Organizations

- White Papers

- Edition Archive

Select Page

Case Study of a 5-Year-Old Boy with Unilateral Hearing Loss

Jan 15, 2015 | Pediatric Care | 0 |

Case Study | Pediatrics | January 2015 Hearing Review

A reminder of what our tests really say about the auditory system..

By Michael Zagarella, AuD

How many times have I heard— and said myself—that the OAE is not a hearing test? How many times have I thought to myself that, just because a child passes their newborn hearing screening test, it does not mean they have normal hearing? This case brought those two statements front and center.

A 5-year-old boy was referred to me for a hearing test because he did not pass a kindergarten screening test in his right ear. His parents reported that he said “Huh?” frequently, and more recently they noticed him turning his head when spoken to. He had passed his newborn hearing screening, and he had experienced a few ear infections that responded well to antibiotics. The parents mentioned a maternal aunt who is “nearly totally deaf” and wears binaural hearing aids.

Initial Test Results

Otoscopic examination showed a clear ear canal and a normal-appearing tympanic membrane on the right side. The left ear canal contained non-occluding wax.

Tympanograms were within normal limits bilaterally. Unfortunately, otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing could not be completed because of an equipment malfunction.

Behavioral testing with SRTs was taken, and I typically start with the right ear. The child seemed bright and cooperative enough for routine testing. I obtained no response until 80 dB.

I switched to the left ear and he responded appropriately. This prompted me to walk into the test booth and check the equipment and wires; everything was plugged in and looked normal. I tried SRTs again with the same results, even reversing the earphones. Same results. When the behavioral tests were completed, the results indicated normal hearing in his left ear and a profound hearing loss in his right ear.

The child’s parents were informed of these results, and we scheduled him to return for a retest in order to confirm these findings.

Follow-up Test

One week later, the boy returned for a follow-up test. The otoscopic exam was the same: RE = normal; LE = non-occluding wax.

Tympanograms were within normal limits. I added acoustic reflexes, which were normal in his left ear (80-90 dB), and questionable in his right ear (105-115 dB).

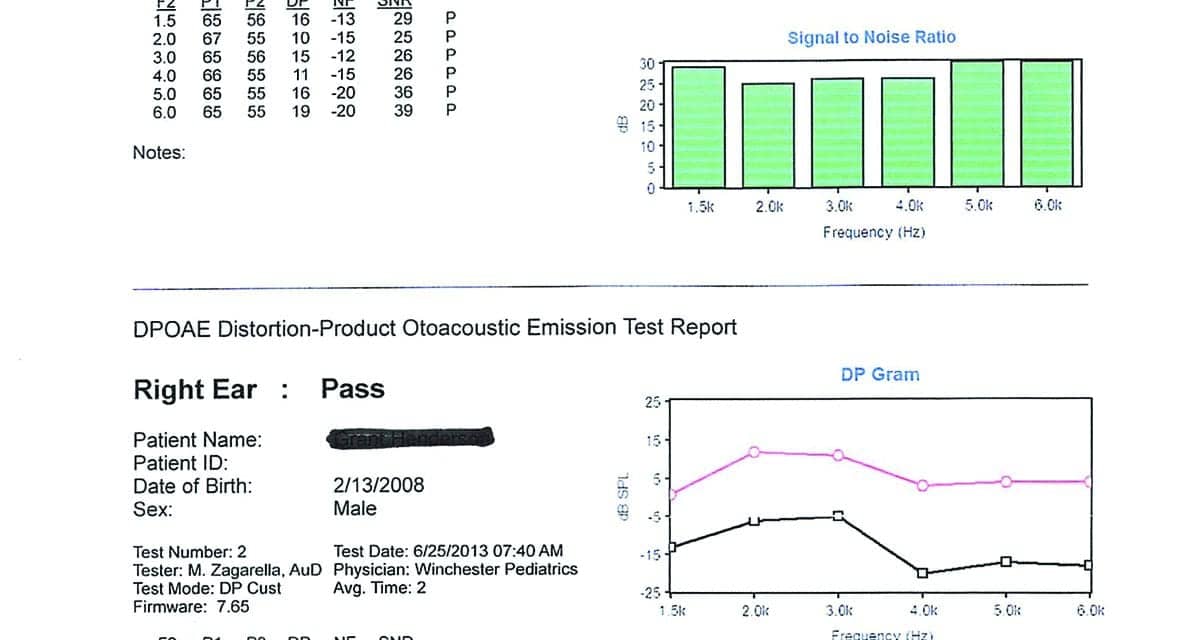

DPOAEs were present in both ears. The right ear was reduced in amplitude compared with the left, but not what I would expect to see with a profound hearing loss (Figure 1).

I repeated the behavioral tests with the same results that I obtained the first time (Figure 2). Bone conduction scores were not obtained at this time because I felt I was reaching the limits of a 5-year-old, and the tympanograms were normal on two occasions.

Recommendation to Parents

After completing the tests, I explained auditory dyssynchrony to the parents, and told them that this is what their son appeared to have. Since they were people with resources, I advised them to make an appointment at Johns Hopkins to have this diagnosis confirmed by ABR.

Johns Hopkins Results

The initial appointment at Johns Hopkins was at the ENT clinic. According to the report from the parents, the physician reviewed my test results and said it was unlikely that they were valid. She suggested they repeat the entire test battery before proceeding with an ABR. All peripheral tests were repeated with exactly the same results that I had obtained. The ABR was scheduled and performed, yielding:

“Findings are consistent with normal hearing sensitivity in the left ear and a neural hearing loss in the right ear consistent with auditory dyssynchrony (auditory neuropathy). The normal hearing in the left ear is adequate for speech and language development at this time.”

Additional Follow-up

The boy’s mother was not completely satisfied with the diagnosis or explanation. After she arrived home and mulled things over, she called Johns Hopkins and asked if they could do an MRI. The ENT assured her that it probably would not show anything, but if it would allay her concerns (and since they had good insurance coverage), they would schedule the MRI.

Further reading: Vestibular Assessment in Infant Cochlear Implant Candidates

Figure 1. DPOAEs of 5-year-old boy.

Findings of MRI. Evaluation of the right inner ear structures demonstrated absence of the right cochlear nerve. The vestibular nerve is present but is small in caliber. The internal auditory canal is somewhat small in diameter. There is atresia versus severe stenosis of the cochlear nerve canal. The right modiolus is thickened. The cochlea has the normal amount of turns, and the vestibule semicircular canals appear normal.

The left inner ear structures, cranial nerves VII and VIII complex, and internal auditory canal are normal. Additional normal findings were also presented regarding sinuses, etc.

Key finding: The results were consistent with atresia versus severe stenosis of the right cochlear nerve canal and cochlear nerve and deficiency described above.

The Value of Relearning in Everyday Clinical Practice

Figure 2. Follow-up behavioral test of 5-year-old boy.

According to the MRI, the cochlea on the right side is normal—which would explain the present DPOAE results. The cochlear branch of the VIIIth Cranial Nerve is completely absent, which would explain the absent ABR result and the profound hearing loss by behavioral testing.

This case has certainly caused me to re-evaluate what I think and say about my test findings. How many times have I heard—and said myself!—that the OAE is not a hearing test? How many times have I thought to myself that, just because a child passes their newborn hear- ing screening test, it does not mean that they have normal hearing?

This case has surely brought those two statements front and center. In addition, what about auditory neuropathy? In about 40 years of testing, I had never seen a case that I was convinced was AN. Naturally, I was somewhat skeptical about this disorder: Is it real, or does it reside in the realm of the Yeti. (Personal note to Dr Chuck Berlin: I truly don’t doubt you, but I do like to see things for myself!)

Finally, this case only reinforces my trust in “mother’s intuition” and the value of deferring to the sensible requests of parents. If she had not felt uneasy about what she had been told at one of the most prestigious clinics in the country, the actual source of this problem would not have been discovered.

So what? Does any of this really make a difference? The bottom line is we have a 5-year-old boy with a unilateral profound hearing loss. How important is it that we know why he has that loss? From a purely clinical standpoint, I think that it is poignant because it brings home the importance of understanding what our tests really say about the hearing mechanism and auditory system (ie, is working or not working?).

And although it may not make a large difference in the boy’s current treatment plan, I do know that the boy’s mother is grateful for understanding the reason for her son’s hearing loss and that it’s at least possible the boy may benefit from this knowledge in the future.

Michael Zagarella, AuD, is an audiologist at RESA 8 Audiology Clinic in Martinsburg, WVa.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or or Dr Zagarella at: [email protected]

Citation for this article: Zagarella M. Case study of a 5-year-old boy with unilateral hearing loss. Hearing Review . 2015;22(1):30-33.

Related Posts

Phonak Launches Web-Based Child Hearing Assessment Toolkit for Schools

June 26, 2013

‘Parentese’ Can Help Boost Child Language Development

February 5, 2020

New Genetic Test Could Prevent Pediatric Deafness

April 4, 2022

People with Learning Disabilities Need to Be Checked for Hearing Loss

September 23, 2014

Recent Posts

- New Insights on Tinnitus Revealed in Apple Hearing Study

- Cilcare Names New Chief Medical Officer

- A Study of Younger People’s Perceptions of Hearing Care

- New AI-Powered Headphones ‘Cancel’ Only Unwanted Sounds

- How Signia Hearing Aids Improved Life for a Music Industry Professional

- Contacta, National Audio Systems Announce Distribution Deal

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Editor-in-Chief

Hannah Dostal

About the journal

Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education is a peer-reviewed scholarly journal integrating and coordinating basic and applied research relating to individuals who are deaf, including cultural, developmental, linguistic, and educational topics.

Latest articles

Special Collections

Explore specially curated collections from the Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education or collections that include articles from the journal.

Highly Cited Collection

Explore a collection of highly cited articles from the Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education .

Family and Practitioner Briefs

Introducing the new Family and Practitioner Briefs: quick-to-read and easy-to-understand briefs about educational strategies, policy decisions, and new topics in deaf education, published quarterly.

Call for Papers

JDSDE invites submissions for an upcoming issue in honor of Dr. Jonathan Henner, a linguist, scholar, and theorist who had a profound effect on multiple fields including but not limited to deaf education, linguistics, and deaf and disability studies.

Read the call for papers here

Submit your research

The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education is currently accepting high quality clinical and scientific papers relating to all aspects of the field.

More information

Follow us on social media

Stay up to date with the latest news and content from the Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education by visiting our Facebook page , or follow us on X.

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education are published online.

- Accessibility

Oxford University Press is committed to making its products accessible to and inclusive of all our users, including those with visual, hearing, cognitive, or motor impairments.

Find out more in our accessibility statement

Related Titles

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-7325

- Print ISSN 1081-4159

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC10686551

Systems that support hearing families with deaf children: A scoping review

Julia terry.

1 School of Health and Social Care, Faculty of Medicine Health and Life Science, Swansea University, Wales, United Kingdom

Jaynie Rance

2 School of Psychology, Faculty of Medicine Health and Life Science, Swansea University, Wales, United Kingdom

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Over 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents who have limited knowledge about deafness and require comprehensive support and information to support and communicate with their deaf child. However, little is known about the systems that support hearing families with deaf children. We performed a scoping review to provide an overview of current literature on the topic.

The protocol of the scoping review was prepared using the PRISMA statement guidelines for scoping reviews. Relevant search terms were used to identify eligible studies following discussion with the study’s steering group. Databases searched were CINAHL, Medline, ProQuest Central and ASSIA, as well as grey literature from relevant journals and online sources. Included were studies published from 2000 to 2021 and available in English.

A search of databases identified 1274 articles. After excluding duplicates, screening titles and abstracts and full texts, 65 papers matched the identified inclusion criteria. Results included 1 RCT, 7 comparative studies, 6 literature reviews, 4 PhD theses, and 47 further empirical studies.

There is limited quality evidence on what supports hearing parents with deaf children. It is evident that further studies are needed to ensure comprehensive support is accessible and effective for hearing parents of deaf children.

Introduction

Authors’ note.

In this paper the terms Deaf and deaf are used. A capital D for Deaf is used to refer to people who identify as Deaf and view themselves as part of Deaf communities, are a Deaf adult, Deaf professional or Deaf mentor, or who may be profoundly Deaf and may use a signed language. When a lower-case d for deaf is used this tends to refer to deaf children or those who are hard of hearing. Currently there is limited consensus about an emic term, as people can feel colonised when a specific label is provided and may be in different places in their individual journey [ 1 ].

Over 5% of the world’s population experience deafness or hearing loss [ 2 ] and by 2050 hearing loss will affect one in ten people. Currently there are an estimated 34 million deaf children globally [ 3 ], and nearly 55,000 deaf children in the UK [ 4 ]. As 96% of deaf babies are born to hearing parents [ 5 , 6 ] who are usually not expecting to raise a deaf child, it is important that families benefit from a range of support processes and interventions. Support in this context can best be described as encouragement, help and enablement, to promote sustainable success and confidence for hearing parents and their deaf children.

When parents find out their child has been diagnosed as deaf or having hearing loss, or when they suspect this to be the case, families begin a journey that involves differing amounts of support, information, and guidance. For many families, initial discussions begin at new-born hearing screening, if these services are available. Newborn hearing screening has become an essential part of neonatal care in high-income countries with positive outcomes following early intervention during the critical period to enable optimal language development. Currently at least 45 US states require new-born hearing screening by law [ 7 ] and others have achieved this without legislation or have it pending. In the UK the NHS newborn hearing screening programme recommends screening for all babies in the first five weeks of life, although there is a notable absence of hearing screening in the Global South [ 8 , 9 ]. The early detection of hearing status can prevent significant detrimental effects on cognitive development happening later. For example, if children’s development needs are not fully addressed [ 10 ] a deaf child may not develop language skills to ensure fluent communication as a vital platform for further learning. Language deprivation in the first five years of life appears to have permanent consequences for long-term neurological development [ 11 ].

Whilst families welcome prompt hearing screening, it is worth bearing in mind the range of perspectives that exist about deafness. Parents say they encounter predominantly medical model approaches, which suggest their child has a deficit [ 12 ], proposing that deafness is treated and seen as an impairment [ 13 ]. Hearing families may find later that there are cultural-linguistic models and alternative approaches that help them understand the social identity of their deaf children. The socio-cultural view that considers the rich environment of Deaf communities, including the naturalness of sign languages with deafness seen as a way of being, and not an impairment [ 14 ]. Diagnostic rituals can set in motion a deficit-orientated way of addressing a child’s needs, sometimes resulting in diminishing parental competence and confidence [ 15 ]. Often parents report that initial information received upon early detection of their child’s hearing loss can be incomplete and coloured by workers’ personal beliefs and values, usually originating from a medical model [ 16 ], when healthcare policies could acknowledge the broad scope of conflicting views that hearing parents may encounter.

Hearing screening, identification and individualised early intervention is critical in helping deaf or hard of hearing children achieve their full potential [ 17 ] and has led many nations to develop Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs. It may be audiology, speech and language services or education professionals who begin to provide parents with advice about communication choices and pathways. Frequently the not-for-profit or charity sector agencies provide additional support and information perhaps because they have wider scope in terms of delivery arrangements.

Systems that support hearing parents with deaf children may include education, health, care, and social services, depending on the child’s age and location. Support may be provided by statutory services and the voluntary sector and may include short-term initiatives and long-term input. Essentially the support families have and the advice they are given in the early years of their child’s life is of key importance. Hearing parents will want to know about how the ear works, about deafness, communication and language choices, their child’s emotional and social development, education, alerting and assistive devices as well as early years support. At an early point there will be discussions with the family about the child’s language development and communication options. Professionals who support families with deaf children may hold a range of views towards sign language, but essentially families will decide about communication choices and whether their child will learn a mixture of spoken and signed language or just a spoken language [ 18 ]. Decisions made about communication choice will likely affect the child and family for a lifetime [ 19 ].

Fully accessible language experiences during the early years are vital in empowering deaf children’s development potential [ 20 ]. There is a critical window for language development and if a child is not fluent in a language by around the age of five years old [ 21 ], he or she may not achieve full fluency in any language. It is a foundational language that is key to the development of future language. Sign language often comes naturally to deaf children, and deaf children exposed to sign language during the first 6 months of life have age-expected vocabulary growth when compared to hearing children [ 22 – 24 ], meaning that learning a signed language can avoid language delays. If parents are keen for their deaf child to learn speech, then sign language does not impede this. Parents can be given misinformation and not be made aware that there are risks in excluding sign language during the critical time of language acquisition, with no evidence that sign language causes harm [ 25 ]. There are recommendations for changes in existing systems to support bimodal bilingualism as default practice, in order to provide the best educational outcomes, which means a signed language and a spoken language [ 23 ]. It is suggested that all deaf children should be bilingual [ 26 ]. However, little is known about the support parents are given at the outset of these decision-making processes.

Critics suggest there is a need to stop dichotomizing spoken or signed language, and to focus instead on educating families about the range of opportunities available [ 19 , 27 ]. Frequently hearing parents of deaf children do not know where to turn for support and can be overwhelmed with advice as they try to understand different methods employed in the language development and education of their child [ 20 ]. Support for hearing parents of deaf children varies globally. A variety of initiatives and projects appear regularly in local and regional news stories, such as support for sign language classes [ 28 ], family camps for deaf children [ 29 ] and artificial intelligence avatars that help deaf children to read [ 30 ]. Support systems are people or structures in society that provide information, resources, encouragement, practical assistance, and emotional strength.

We argue that there is limited published evidence about the support systems for hearing parents with deaf children. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review to provide a baseline overview of the published evidence until 2021 of the extent, variety, and nature of literature in this area.

Aims of the study

The aim of this scoping review was to map available evidence regarding the systems and structures surrounding deaf children and their families with hearing parents/guardians.

The specific objectives were to:

- identify published studies describing support systems and structures that support hearing parents with deaf children, and

- review the evidence of these studies.

The primary objective of this review was to assess the number of studies and their characteristics such as their origin, study designs, study population, type of support and key findings regarding systems or supports for hearing parents with deaf children.

Study design

We followed PRISMA-ScR guidelines for scoping reviews in the conduct of the literature review, data extraction/charting, and synthesis. The main aim of a scoping review is to identify and map the available evidence for a specific topic area [ 31 ]. The approach to the review was based on Arksey and O’Malley’s framework [ 32 ] which consists of the following stages: i) identifying the research question; ii) identifying relevant studies; iii) selecting studies; iv) charting the data; and v) collating, summarising and reporting the results. Ethical approval was not required because the study retrieved and synthesised data from already published studies.

Identifying the research question

The core aim of this scoping review was: What is the existing research that examines support systems for hearing parents with deaf children. The focus on hearing parents was due to over 90% of deaf children being born to hearing parents, who have little knowledge of deafness and deaf people, which is different from the experience of Deaf parents parenting deaf children [ 33 , 34 ]. An initial a priori protocol was developed and published on Open Science Framework in February 2021, and then revised using feedback from the project steering group over the course of the project, as scoping reviews are an iterative process [ 35 ]. The steering group comprised Deaf and hearing professionals and lay members, people working with Deaf charities, in health, education, policy and academia. Decisions were documented in a search log and steering group meeting notes to record the scoping review process. The final protocol was registered on 24 th August 2022 with the Open Science Framework— https://osf.io/w48gc/ .

Identifying relevant studies

The scoping review research question was left intentionally broad and was discussed in-depth at the first project steering group where members generated 50 words and terms to be included in the outline database searches. The evidence was searched using four electronic databases, hand searches of reference lists of key journals and repositories (such as PROSPERO), and contact made with key authors; as well as internet site searches for policies and reports. The wider project involves interviewing family members and workers situated in Wales, UK, so the scoping review included material specific to Wales as well as other geographical areas nationally and internationally that has contextual similarities (for example, grey literature including newspaper articles about family situations and support projects, blogs and regional reports), and these were included in the early stages of the review. An experienced information specialist’s help was sought in reviewing the PICO framework (see Table 1 ) and specific search strategies. The databases included were CINAHL, Medline, ASSIA and Proquest Central, with searches conducted between May and June 2021, and updated in January 2022. (An example of the search strategy for one database is provided as an additional file).

Different techniques and terms were used to expand and narrow searches, including tools such as medical subject headings (MESH), Boolean operators and Truncation. Single and combined search terms included key subject area on deafness, children, BSL/sign language and parent/family words. Limitations were set to include papers in the English Language and peer-reviewed research from the time period January 2000 onwards. In addition, key journals, professional organisation websites and reference lists of key studies were searched to identify further relevant documents. The final search strategy and terms were agreed and verified by a health subject librarian.

Inclusion criteria were: published research articles and dissertations, literature reviews and PhD theses specific to a) parents and families/caregivers b) deafness/hard of hearing/hearing loss c) sign language or British Sign Language (BSL) d) child or young person e) information specific to support, systems, challenges, barriers f) were published in English between 2000–2021. The inclusion criteria were purposely broad, as there is a dearth of scientific evidence on the area of support and systems for hearing parents with deaf children.

Exclusion criteria were: papers pre-2000 (unless they met a-e of inclusion criteria above); papers without a focus on deafness, papers that focused solely on literacy, or were short news items or opinion papers, and/or did not focus on support issues for hearing parents of deaf children.

Study selection

The initial search produced a total of 1274 results from database searches (see PRISMA, Fig 1 ), which were screened, and a further 192 records were added from internet and hand-searching. An example of a database search is provided in Table 2 . Once duplicates were removed (n = 2653+18) and a further 8 discounted as pre-2000 that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 1202 publications remained, and titles and abstracts were screened. 821 records were then removed in line with the eligibility criteria, and the remaining 381 full texts were obtained, and details transferred to an Excel database for sifting. Knowledge synthesis was achieved by peer review using Rayyan software [ 36 ] and annotated spreadsheets of retrieved papers, which were reviewed by two researchers independently with inter-rater discrepancies resolved by discussion.

We began by excluding sources that did not describe support for hearing parents of deaf children, such as opinion articles, newspaper reports, and papers without a deaf focus. Screening full texts resulted in a further 316 papers being excluded, leaving a total of 65 publications included in this review (see Fig 1 PRISMA diagram).

Charting the data

A data-charting form was developed by one reviewer, and then updated iteratively in discussion with the second reviewer, which was piloted and found to be effective. The data extracted were the author, year of publication and country of origin, study design, sample population, study aim and findings and study strengths and weaknesses, (see Table 3 ). Articles meeting inclusion criteria were examined, and data was entered into Excel spreadsheets, which included sample characteristics (age range, clinical characteristics, sample size); and experimental and control measures, as applicable.

Through this process sources were identified as follows: 55 primary research studies, four PhD theses and six literature reviews.

Collating, summarizing and reporting results

From the final scoping review, 21 individual countries were represented ( Fig 2 , which present the distribution by country). Most publications came out of the USA, Australia, the UK and Canada, which may be due to greater funding in this area of research compared to other nations.

Due to the heterogeneity of the range of study contexts, a narrative synthesis was a reasonable way to approach the reporting of retrieved studies. After summarising the information from sources, a thematic framework was applied to categorise the areas of support for hearing parents. This involved sorting studies into categories as follows: i) Communication choices and strategies; ii) Interventions and resources; iii) Family perspectives and environment; and iv) Deaf identity development . In addition, strengths and limitations of the sources are presented in Table 3 . Context from the grey literature is included in this paper’s introduction section, as this clinical wisdom provides additional information and context.

Theme one: Communication choices and strategies

Hearing parents will need to decide whether their deaf child will communicate using a spoken language or a signed and spoken language [ 37 ]. The timing of this communication choice is challenging as hearing parents make decisions during the small window when their child starts to develop language during the first few years of life. Hearing parents have little understanding about deafness, nor is infrastructure present to guide parents towards appropriate engagement with Deaf communities to begin discussing the differences between communication strategies. Parents can be inundated with information regarding communication and educational methods [ 20 ]. Yet the decision is up to parents and the key factor being that any form of early language development is critical [ 19 ]. Around the decision-making time, parents commonly want to know what will give their deaf child the best chance of learning to communicate, and whether using sign language might adversely affect their academic achievements and if it is worth waiting to see the impact of a cochlear implant before learning sign language [ 5 ]. There is frequent reporting that medical professionals claim that promoting a signed language with a deaf child may delay or hinder the development of spoken language learning, with suggestions that children may be confused [ 5 ], although much evidence supports the positives of learning to sign [ 19 ].

Retrieved papers under the communication choices and strategies theme included 20 primary research studies and two literature reviews. The 20 primary research studies included three co-comparative studies, four quantitative studies and twelve qualitative studies and one PhD thesis.

Factors contributing to parents’ selection of a communication mode to use with their children with hearing loss, are reported as information, perception of assistive technology, professionals’ attitudes and the quality and availability of support [ 38 ]. Parents’ decisions about communication choices with their deaf child are strongly influenced by the information they receive, which in the main focuses on amplification of sound, with information givers rarely mentioning sign language approaches [ 39 ]. Parents who chose speech only as a communication choice appear to have received advice from education and speech/audiology professionals more often [ 37 ]. Similar findings are reported in other studies that parents relied heavily on advice from professionals [ 40 , 41 ]. There is suggestion that advice from speech and language professionals, audiologists and specialist teachers was valued by parents over medical or non-professional views [ 42 ]. Conversely, parents of deaf children they surveyed did not find any professional group’s advice more influential than another, and reported they ultimately relied on their own judgements to make decisions about their child’s communication choices [ 43 ].

Several studies in this scoping literature review compared hearing and Deaf parents’ views about communication choices as well as child outcomes. Deaf parents are likely to choose a more visual mode of communication for their deaf child, and frequently outperform hearing parents in interaction studies that compare hearing and Deaf parents’ engagements with their deaf children [ 44 ]. For example, Deaf parents tend to use a higher level of tactile strategies when communicating with their deaf child compared to hearing parents [ 42 ].

When parents make hearing technology and communication modality choices for their children amongst competing discourses of deafness and language, hearing program principles of fully informed choice of communication narrowly reflected medical knowledge of deafness only [ 43 ]. Frequently there is reported to be minimal information about sign language and Deaf culture, and over time parents resist medical knowledge and asked for alternate services as their knowledge of their own children grew beyond diagnostic assumptions [ 43 ]. Initial adoption of a medicalised model script is recognised as occurring, which often maintains a strict divide between competing views of deafness [ 44 ], such views may include parents thinking their children are successful if they do not need a signed language.

In a comparative study two groups of hearing mothers with deaf children were studied, with one group more experienced as their children had been diagnosed for more than 24 months (compared to the mothers with children diagnosed in the last 18 months) [ 45 ]. The aim was to investigate the type of communication strategies that parents use with their children and how the type of early intervention (EI) involvement affected parents’ values about communication strategies. Mothers completed questionnaires about their views on communication strategies and were also videoed for 3-minute mother-child play interactions, and only minor differences were found between the groups of less and more experienced mothers of deaf children suggesting limited impact of early intervention programs on parental choice of communication method [ 45 ].

The main factors that influenced caregivers to change the communication method with their child with hearing loss included family characteristics, access to information [ 46 ], family strengths, family beliefs, and family practices, with the family at the core of decision-making regardless of severity of hearing loss, family demographic or type of device used or communication approach [ 47 ]. Similarly, the importance of communication changes regarding language modality being child-led, as parents adapted their language choices in line with their child’s needs to improve communication confidence, noting that early sign language exposure benefits the development of spoken language [ 48 ].

A comparative study of hearing versus Deaf parents with their respective deaf children acknowledged the active role that parents, and children take when communicating as they sought to explore successful joint attention (where one party seeks to gain the attention of the other, and the other responds) [ 49 ]. Studies that inform understanding of factors supporting language success are crucial. Communication in families will always be a joint venture and knowing if gaining joint attention at an early development point would assist families and professionals with communication choices in the future [ 49 ]. Very often parents want to know exactly what it is that will help communication to be most effective.

Complexities of communication choice are apparent in studies that focus on the intricacies of self-identify in children of parents who chose sign language as a primary mode of communication [ 50 ]. Follow up appointments focusing on communication modality, particularly following cochlear implantation, suggest a background of opposing views on communication choice mean increased awareness for parents is vital [ 51 ]. Families can unknowingly overprotect their child, limit knowledge and skill development due to hearing parents’ lack of knowledge and understanding about Deaf culture and Deaf communities [ 52 ]. All three studies highlighted the importance of continuing professional development for workers in order that they gain familiarity with these topics, and in turn discuss them with families of deaf children [ 50 – 52 ].

Perceptions of factors that foster success in deaf students from parents, teachers, interpreters, notetakers and deaf students themselves do not mention communication choice at a young age; instead, success was attributed to strategic components including self-determination, family involvement, friendships, reading and high expectations [ 53 ].

In one study deaf children of Spanish-speaking families studied did not learn American Sign Language (ASL) early on, often coming to this much later, with many of the children having limited access to language early on, and parents expressing frustration at not being able to communicate with their children, with the family being left behind through delaying communication through ASL [ 54 ].

The importance of professional advice provided to hearing parents of deaf children about communication mode and language use choices is noted, as this may heavily influence caregiver choices about communication. Understandings about factors that led to specific communication choices by hearing parents could be gained through further research [ 55 ]. The next theme focuses on papers concerning interventions and resources that support hearing parents with deaf children.

Theme two—Interventions and resources that support hearing parents with deaf children

Theme two incorporates identified studies that focused on interventions and resources that support hearing parents with deaf children. In this section we report on intervention programmes for hearing parents with deaf children broadly, then how programs were delivered and finally specific types of interventions that support hearing parents with deaf children.

Specific interventions of Deaf mentors and role models

A scoping review of early interventions for parents of deaf infants [ 56 ] found that interventions commonly focus on language, communication and parent knowledge, well-being and parent/child relationships and did not find any studies focusing on parent support to nurture socio-emotional development, which is often a poor outcome for deaf children. Socio-emotional development is not well-analysed by hearing professionals, who may not realise that it is not deafness that needs fixing but everything around it. It was concluded that research in this area is much needed, with most studies conducted some time ago and not in line with healthcare advances, recommending further research to develop evidence based early intervention [ 56 ]. A literature review of early intervention programme models and processes [ 57 ] identified five themes which were caregiver involvement, caregiver coaching, caregiver satisfaction, intervention program challenges and telehealth. Understandably caregiver involvement needs to be culturally and linguistically appropriate, as this improves caregiver satisfaction with services and improves outcomes for deaf children [ 57 ]. Another example is the HI-HOPES intervention program, developed in 2006 and still current, with an appreciation of South Africa’s characteristic linguistic, racial, and cultural diversity, noting embedding of cultural values and practices and includes provision of Deaf mentors [ 58 ].

A series of studies of the Colorado Home Intervention Program over nine years [ 59 ], saw a change in the average age of intervention decrease from 20 months to 2 months, meaning infants had much earlier intervention and therefore increased their language and social-emotional range. The early engagement with parents from a CO-Hear co-ordinator about choice of intervention service is a key success factor [ 59 ]. Another language intervention program with a sole parent focus, this time oral only, is the Muenstar Parental Program [ 60 ], a family-centred intervention following newborn hearing screening. Parents received training on the positive impact their behaviour had on their infant including showing more eye contact, more imitations and more listening, where parent and trainer discuss and agree principles to intensify in the next videotaped interaction. Although only single training sessions [ 60 ], authors noted the model to be a comprehensive early intervention focusing on encouragement, however, when published it was at the concept stage with minimal data available.

Summer pre-school language environments compared to their home environments suggest there are benefits to children, whilst recognising that pre-schoolers’ parents continue to require education around language strategies [ 61 ]. Parents would likely benefit from guided practice regarding extending conversations and asking questions at their child’s language level, and how to expand their children’s language, and that practising these skills with a professional is essential [ 61 ].

Mentors for families with deaf and hard of hearing children have been found to be highly effective, with study examples of family mentors [ 62 ] and mentors for children [ 63 ]. There is an awareness that parent- to- parent support models are rooted in disability ideologies and are highly valued [ 64 ], and often need to be unique [ 62 ]. Parent mentors made notes following each phone support conversation, and notes analysed over a two-year period showing hearing related conversations, early intervention and multiple disabilities were the primary topics of conversations between parent mentors and families. A literature review and eDelphi study to define the vital contribution of parents in early hearing detection and intervention programs suggested supporting, or a mentoring parent was well received [ 65 ].

Similarly Deaf adults are a key element in early intervention programs [ 66 ], primarily as role models and language providers, noting that families do not have a range of Deaf professionals to connect with in early intervention programs. One of the first reported studies of Deaf family mentors [ 63 ] provided a Deaf adult mentor who made home visits to deaf children and their families to share language, as well as a hearing advisor to support to parents. This type of provision is referred to as bilingual-bicultural and was intended as introductory in the first instance in two US states. The Deaf mentors taught each family American Sign Language (ASL) signs, interacted with the child using ASL, shared Deaf knowledge and culture and introduced the family to the local Deaf community, promoting a bi-bi home environment. It is reported children with Deaf mentors used more than twice the number of signs and parents used more than six times the number of signs than the control group [ 63 ]. 85% of survey respondents in the Lifetrack Deaf mentor family program operating in Minnesota USA reported their child’s quality of life to have improved, and 76% of families finding the information about Deaf culture ‘very helpful’ [ 67 ]. There are limited examples of early intervention providers that include Deaf mentor provision for children and families in the US, and whilst 27% of their survey respondents said there were a diverse range of Deaf professionals for families to connect with; but only 2% of respondents reported the first point of contact with early intervention professionals had been with a Deaf person [ 66 ].

Delivering intervention programs using telehealth

Although the provision of healthcare with remote support has become commonplace during Covid-19, prior to the pandemic many services used telehealth because it offered the potential to meet the needs of underserved populations in remote regions [ 68 , 69 ].

Tele-practice or tele-intervention (or virtual home visit) has been used increasingly as a method of delivering early intervention services to families of deaf children. Tele-practice intervention outcomes were compared for children, family and provider compared to in-person home visits using fifteen providers across five US states (Maine, Missouri, Utah, Washington and Oregon) and found children in the telepractice intervention group scored significantly higher on their receptive and total language scores that the children who received in-person visits [ 70 ]. Higher scores were also reported with telepractice intervention for parent engagement and provider responsiveness compared to in-person visits [ 70 ]. Parents reported having better support systems, feeling better supported by programs and knowing how to advocate more for their deaf child. Notably in-person visits were reported to focus more on intervention with the child with parent observation, whilst tele-practice engaged parents more in supporting parents as the child’s natural teacher. Equally when comparing tele-intervention with in-person visits, increased engagement from the tele-intervention group has been reported, with families reporting themselves to being ‘more in the driving seat’, and specialised early intervention services for families with deaf children via telehealth to be cost effective [ 71 ].

Preschool and school services were examined for children who are hard of hearing and described service setting, amount, and configuration, analysing relationships between services and hearing levels and language scores [ 72 ]. Noting that as children reach the age of three years that services often shift from being family centred to being more child focused and a need for more interprofessional practice to best meet the needs of children who are deaf. Findings that 19% of families did not receive any intervention, which rose to 30% by the time children were of school-age [ 72 ].

Intervention support—Teaching sign language to parents

Another specific type of intervention to support hearing parents with deaf children is supporting the teaching of sign language. When deaf children are introduced to sign language there is an obvious need for parents and significant others in the child’s situation to learn to communicate in that language. However, if there are no other Deaf members of the family, a signed language may not be used in the home. Therefore, the deaf child may not have the exposure to language role models in the home in order to acquire a signed language as a first language. Giving parents a way to communicate with their deaf child will mean parents are provided with greater opportunities to engage effectively with their child’s world. It may be that a signed language does indeed later become a deaf child’s primary language, and early development of this in the home can be key. Six key components in any language development and support programme for parents include communication strategies, language tuition, immersion/language use, language modelling, information giving and practical/emotional support [ 73 ]. During curriculum development of Australian Sign Language (Auslan) and creation of family-specific resources, after finding the need for a language development program that incorporated classroom teaching, incidental learning opportunities and natural sign language immersion with additional learning resources. There is limited available evidence on the teaching of a signed language but researchers stress the need for involvement with Deaf adults or what it is like to live as a Deaf person being of primary importance [ 73 ].

A five-year sign language intervention project is reported [ 74 ] with 81 hearing family members in Finland learning sign language once a week with a teacher who was Deaf, Parents, siblings, and other relatives met once monthly to study sign language, and all families in the project signed together about twice yearly. Noting that if one is to succeed in modern society, communication competence should be good [ 74 ], and found that families most actively involved learned a greater amount.

One challenge noted by research teams regarding interventions given the geographic dispersion of children who are DHH is the shortage of adequately trained professionals [ 70 , 71 ]. The next theme presents material from the literature about family perspectives and environments.

Theme three: Family perspectives and environments

Family perspectives and environments are an over-arching theme that include evidence about family experiences, needs, coping and environmental relevance, and are reported in this section.

A study of family experiences and journeys exploring reactions, behaviours and strategies with 50 hearing parents with deaf children in Karachi City, Pakistan [ 75 ], found all parents reported shock on learning their child was deaf, and 99% were stressed by this news. 98% of these parents wanted counselling and support about three main areas: diagnosis of hearing impairment, speech and communication, and hearing aid maintenance, with specific structured counselling and information sessions in hospitals or schools recommended [ 75 ]. Family journeys with childhood deafness in Mexico are explored through the lens of a pilgrimage through Pfister’s [ 76 ] study as families realised their quest was not about fixing hearing but about finding more reliable communication methods. Parents reported the most common support was in the form of biomedical options which had restricted scope. Families also reported countless troubling questions without a forum to present them [ 76 ]. Similar to the concept of impairment as a predicament that can be overcome [ 77 ], families wanted to continue their quest for worlds people inhabit and aspired to challenge medicalised ideologies, which suggest family perseverance [ 76 ]. Eighteen hearing parents of deaf children in Western Australia reported struggling with a deafness diagnosis and recommendations for professionals who should not “just give a pamphlet to parents…never assume technology will cure all…and find out how a family ticks” [ 78 ]. It is stressed that more research is needed about deaf children with hearing parents across various life stages to fully understand potential challenges; and concluded that Deaf parents of deaf children have much insight to offer hearing parents with deaf children.

Studies that examined hearing families’ stresses and needs highlighted socioeconomic and cultural factors impacting on carers of deaf children in Ecuador around education and employment [ 79 ]. Carers are critical of new measures around schooling that may lead to reduced resources and discrimination and propose future healthcare practitioners screen deaf children for potential abuse regularly due to their vulnerabilities. Using the Parenting Stress Index and information gathered on personal and social resources, researchers found parent variables are largely responsible for successful child development [ 80 ]. A correlational study of stress levels and coping responses found the relationship between family and parental stress and a crisis with a child with a disability to be complex [ 81 ]. Notably families who were able to communicate with their deaf child through a signed language found this was positively related to their stress experience.

Parenting stress reported by Korean mothers of deaf children [ 82 ] suggests a need for comprehensive support services that include schools, parents, siblings and social workers, as they reported on-going alienation in mainstream education [ 83 ] and feeling left out within family relationships. Having a child with hearing loss does change family dynamics as hearing loss becomes the dominant family topic. Healthy families of children who were deaf were interviewed to identify what contributed to a health family dynamic [ 84 ]. Finding that families engage with a variety of professionals, there was a reported desire for professionals to more actively listen and to demonstrate confidence in families to capitalise on existing strengths and resources [ 84 ]. Proactive families welcomed workers who were willing to tolerate a variety of perspectives and options for them and their deaf children, and for workers to create social events for families and workers to interact together. Often hearing families report not having a true voice because they do not understand educational processes and systems, which does not help them to advocate for their deaf children [ 85 ].

Researchers who explored coping strategies of parents with deaf children note that parent stress is not an outcome of child deafness but of different characteristics of the context, perceptions and resources [ 86 ]. Exploring critical incidents with parents whose children have Cochlear implants to understand what influences parents’ coping suggest opportunities to share experiences with others and consistent family support are essential, as is the importance of understanding what hinders coping processes [ 87 ]. Adolescents themselves with Cochlear implants in Copenhagen reported diverse experiences from others of similar age, with participants reporting higher levels of feeling different from others also reported higher levels of loneliness, although this was less for those implanted at a much earlier age; and implies the need for flexible tailored support for all [ 88 ]. The actual reasons for deaf adolescents reporting loneliness is not fully known. Family environments can be enhanced by education and therapy to create robust language environments to maximise cochlear implanted children’s potential [ 89 ]. Families who reported they had a higher emphasis on being organised self-reported they had children with fewer inhibition problems, and that emphasis on structure and planning in family activities can help grow a supportive social family climate. Family environments are one area that can be modified when families become aware of problems impacting on their child’s progress [ 89 ].

A historical study conducted in Cyprus reported on Deaf adults’ childhood memories and how when they were children they reported feeling isolated in family environments due to lack of communication as families often refused to learn sign language [ 90 ]. This worsened when extended family visited and speech pace increased. The ‘dinner table syndrome’ is much reported and describes indirect family communication that occurs at family meals, during recreation and car rides that provides important opportunities to learn about health-related topics and are common to most families [ 91 ]. Deaf people with hearing parents often report limited access to contextual learning opportunities during childhood [ 92 ] which highlights the importance of environmental factors.

However for deaf children introduced to Deaf adults in Deaf clubs there are clear benefits for engagement with Deaf role models, where they can discuss serious issues and communicate effectively [ 76 , 90 ]. Although it must be noted that Deaf clubs in many parts of the UK and US are reducing in number [ 93 , 94 ]. Social success can be viewed differently, with hearing children and parents seeing their friendships more positively than deaf children [ 95 ]. Evidence is consistent about deaf children with Deaf parents having higher social success and better communication outcomes than deaf children of hearing parents [ 95 ].

Theme four: Deaf identity development

Deaf identity development describes the contrasting nature of opposing aspects of deaf and hearing perspectives on topics that relate to support for hearing parents, for example models of deafness and language and communication modalities, as well as ways deaf people encounter Deaf identity.

A review of mainstream resilience literature, in relation to what it means to be deaf and the contexts of deafness around disability, suggest resilience is often about challenging social and structural barriers [ 96 ]. The barriers in themselves often create risk and adversity, and for deaf young people the successful navigation of “countless daily hassles, which may commonly deny, disable or exclude them” is a key definition of resilience [ 96 , p 52]. Protective factors and skill development are the enablers.

The cultural constructs of deafness and hearingness can best be viewed through a lens of multimodality, with communication being more than about language [ 97 , 98 ]. The focus on why the body matters in how we, hearing and Deaf, come to shape a sense of self and the interplay between resources we use in the process. Such intersections are important in the development of identity and social skills. Aspects of adolescent-reported social capital (for example, the networks and relationships that enable a society to function) are reported as being linked to their language and reading skills, with deaf young people found to have less strong social skills than their hearing peers [ 99 ]. Aspects of adolescent-reported social capital are positively related to their language and literacy outcomes, suggesting the importance of increased promotion of social capital in adolescents who are DHH and their families [ 100 ].

The importance of understanding different ways that deaf children are contextualised, usually through the medical model, the social model and the Deaf culture model of Deafness are reported [ 101 ], with the medical model remaining dominant and framing being deaf as having hearing that does not work and needs to be treated to restore Deaf people to the normality of the majority of the population. The social model of deafness focuses on disability and strives for inclusion to ensure differences are supported. A Deaf cultural model values and celebrates Deafness collectively, often with a focus on Deafhood [ 102 ] and Deaf pride, where the label of impairment is seen negatively. A social relational model that is more about how deaf children shape their own identities and relocating the balance of power to create policy directives regarding increased use of signed language would enable greater inclusion and would directly challenge structures that exist [ 101 ]. Re-framing deaf children as plurilingual learners of signed language, English and additional languages, instead of as deficient bilinguals by dominant culture standards has potential [ 101 ].

Hearing parents’ experiences of adjusting to parenting a deaf child is impacted by the cultural-linguistic model of deafness have been examined, and how challenging the notion of a loss or deficit and instead using a model which promotes a linguistically able and culturally diverse lens [ 103 ]. An early intervention programme in the UK involving hearing parents and hearing teachers where families received weekly visits involving Deaf consultants in the role of ‘Deaf friend’ engaged family members in games, discussion and sign language tuition. Two key findings were reported with parent anxiety about the meaning of deafness reported as lessened by a Deaf adult ‘simply being themselves’ [ 103 , p163]. Equally, the relationship between childness and deafness, concerned with the overlap of a child being both a child, and a deaf child, and the importance of accepting the child and their child’s deafness. The cultural-linguistic model of deafness on the adjustment process hearing parents of deaf children experience is a potential tool to support parents through their reactions to their child’s deafness [ 103 ].

The discursive context of cultural-linguistic model views and medical models of deafness perspectives is present in hearing mothers’ talk and how they positioned their meanings of the two phenomena [ 104 ]. The language of advice from professionals has substantial influence, and positioning theory helps to explain the discrepancies parents experience between reported and actual plans for language practices [ 104 ].

An in-depth analysis of a shared-signing Bedouin community [ 105 ] highlights how deafness does not easily fall under the medical model because a wider lens is used in communities where many individuals who are hearing sign too, similar to Martha’s Vineyard situations [ 106 ]. Evidence is generally about Deaf communities rather than signing communities [ 106 ], and how linguistic communities do not just share a language but knowledge of its patterns of use and its cultural distinctions (such as attention getting and name giving) can be key in terms of identity development.

Descriptions of the Deaf Bi-lingual Bi-cultural community (Bi-Bi) helps us to understand this unique identify in an increasingly diverse world, and the relationship between language and identity formation and people’s social participation [ 107 ]. Misconceptions about bi- and multilingualism frequently recommend families limit their deaf child to learning oral English only, although multiple languages result in fluid conversational exchanges, trusting parent relationships and a strong cultural identity. Increasing clinicians’ understanding of language and culture, particularly Deaf culture would mean they could more effectively support child development and respond to human diversity issues in healthcare environments [ 107 ].

The importance of signed stories and how Deaf teachers’ storytelling in schools is an important part of deaf children’s identity development [ 108 , 109 ]. Due to the decades of strict oralist policies (from 1880 to 1980) [ 110 ], many deaf children do not experience the possibilities of a Deaf identity unless they go to a deaf school due to the lack of employment of Deaf teachers in mainstream education. Signed stories are a way of teaching deaf children about their linguistic and cultural heritage [ 108 ]. Rather than conceptualising deaf people as individuals who cannot hear, Deaf people see themselves as viewing the world visually and often use sign language, so deafness is not a loss but a social, cultural, and linguistic identity.

The aim of this scoping review was to identify published evidence on the supports and structures surrounding hearing parents with deaf children. The characteristics and results of the included articles were assessed. To the authors’ knowledge this is the first scoping review that focuses on what supports hearing parents as they in turn nurture their growing deaf children. Following a thorough database search and eligibility criteria, 65 papers were included in this scoping review. While it is a large amount of evidence about what supports hearing parents with deaf children, the evidence is mainly based on small, non-repeated studies with few randomised controlled trials published on the efficacy of support for families with deaf children. Current knowledge has therefore been framed as a narrative synthesis of reports of what supports families.

When families with deaf children are introduced to communication choices and strategies, their decisions are strongly influenced by the information they receive [ 46 ], but ultimately, they rely on their own judgements, with family characteristics, family strengths and beliefs also considered [ 47 ]. Hearing parents are less likely to choose a visual mode of communication, which may be due to hearing programme principles reflecting a predominantly medical model of deafness resulting in more ableist and audist approaches [ 43 ], although some parents do go on to ask for alternate services over time as their own knowledge of their child grows. It is reported that there are three phases of decision-making—information exchange, deliberation, and implementation, with two key decisions dominating on implantable devices and communication modality [ 111 ].

When discussing communication choices with families, there is a need for professionals to be familiar with and understand the cultural ecology [ 12 , 46 ] and that parents may make choices without access to information, and that not all choices are available. Culturally incompetent care often spreads health inequalities for Deaf people [ 28 ]. Increased awareness of communication choices is vital for parents because families may unknowingly limit knowledge or skill development due to limited awareness of Deaf culture and Deaf communities [ 52 ].

Studies that were categorised as providing evidence about interventions and resources that support hearing parents made mention of the value of interventions that focused on language, communication and parent knowledge as well as supporting parent-child relationships. There was a paucity of evidence about nurturing socio-emotional development which is often a poorer outcome for deaf children when compared to hearing children [ 56 ]. There was an emphasis that intervention programmes need to be culturally and linguistically appropriate, as this improves caregiver satisfaction [ 57 ], and that all interventions with families need to address linguistic, racial and cultural diversity elements.

The provision of Deaf mentors was noted to be a popular feature with families [ 58 – 60 ]. Although there are often few Deaf professionals in services for families to connect with and limited evidence of sustained Deaf mentor programmes available [ 66 ]. A supporting parent was also a welcome intervention, which carried less sense of a hierarchical relationship and families reported valuing such input [ 65 ].

There is evidence to suggest that intervention and support occurring early result in better language for deaf children at later point [ 59 ]. Giving parents guided practice with examples for their individual child’s language level and practice of this skill with a professional was highlighted as useful [ 61 ]. Increasing evidence suggests that deaf children having access to a signed language at the earliest possible age is beneficial [ 22 ] but it must be noted that Deaf people’s under-achievement in education is not a result of deficits within children themselves but relates to the ‘disabling pedagogy’ to which they are routinely subjected [ 112 ].

Whilst many services have moved online during the pandemic, the reported results for parent intervention with deaf children are before Covid-19 occurred, with telepractice groups scoring significantly higher on their total language score and more in the ‘driving seat’ [ 73 ] which may be due to parents saying they felt better supported and engaged through this route. As deaf children grow older, and services move to being more child-focused than family-focused there is evidence that families voice feeling less supported with over 30% reporting no intervention by the time children attend school [ 76 ].

The reported key components of language and support programmes for parents are that communication strategies, language tuition immersion and language modelling, as well as information and emotional support are all essential [ 73 ]. It is not uncommon for support programmes to include family get togethers sporadically, say two to three times per year [ 74 ].

The family perspectives and environment theme included reports that 98% of hearing parents wanted counselling on discovering their child was deaf [ 75 ]. A priority for parents was finding reliable communication methods, and whilst parents had commonly been offered biomedical options and information, many suggested they wanted a forum to raise concerns and questions [ 76 ] and did not want to overly rely on medicalised ideologies [ 77 ]. More information was wanted from hearing parents about challenges they might encounter at different life stages for their child [ 78 ].

Environments for deaf children need vital consideration due to the potential for abuse of vulnerable groups [ 79 ]. However, parent variables are largely responsible for successful child development [ 84 ]. One example being parents who were able to communicate through sign language found this significantly lowered their stress as communication with their child was available to them [ 81 ].

Families were keen for professionals to value their strengths and resources, and particularly for social events to be arranged with other families with deaf children [ 84 ]. Parent stress seems to be more related to context and resources than actual child deafness [ 86 ] and knowing what hinders coping would be useful knowledge [ 87 ]. Enhancing family environments with education and therapy or therapeutic support is key [ 89 ]. Environmental factors for hearing parents with deaf children are vital, which is particularly evident with discussion of the dinner table syndrome with children missing out on many learning opportunities and family relational communication [ 91 ]. It is notable that deaf children with Deaf parents frequently outperform deaf children with hearing parents because of their early language encounters and immersion in an inclusive world [ 95 ]. The reverse is true for deaf children.

The theme Deaf identity development highlighted the importance of the intersectionality of Deaf identity in relation to other cultural identities [ 99 ]. Successful identify development is strongly linked to social capital [ 100 ], so rather than being contextualised by the social model, the Deaf culture model of deafness offers a more positive view which may empower both hearing parents as well as their deaf children [ 102 ], as this challenges a deficit model and promotes a more linguistically able and culturally diverse lens [ 12 ]. Tools that promote acceptance of deafness, adjustment and managing reactions have much scope [ 103 ].

The language of diagnosing and medical professionals can have substantial influence, as well at the position that they take [ 16 ]. Communities that include hearing signers have much to offer, as the notion of signing communities suggests the benefits and richness of signed languages [ 106 ]. It is worth noting that most deaf children are not exposed to the idea of a Deaf identity unless they go to a Deaf school and have exposure to deaf children and Deaf adults on a regular basis. Since the evidence search for this scoping review was undertaken, further publications also support our conclusions. Namely that health care professionals and early intervention providers must inform parents about signed language as a language choice as the majority of parents only learn about such options through their own research [Lieberman]. Also that supporting parents’ development of communicative competence in signed languages has significant implications for meeting their deaf children’s communicative needs [ 112 , 113 ].

Limitations

A systematic and rigorous approach was adopted when carrying out this scoping review. Evaluating the findings of this scoping review the limitations are discussed in this section. The inclusion criteria were purposively broad at the outset, and due to the high number of retrievals it became clear that focusing on empirical research studies would provide the most valuable evidence. However, whilst some support programmes had been sustained over time, many were short term projects with small samples.

One limitation could be that only articles published in the English language were included in the review, therefore articles in other languages may have been missed in the search. Support systems for hearing parents with deaf children vary greatly. A formal quality appraisal of the included articles was beyond the scope of this review. To decrease the risk of bias the selection of retrieved papers was monitored and viewed independently by two researchers with differences of opinion resolved through discussion. A total of four electronic databases were selected and searched, and despite those covering a range of academic fields their databases may potentially have been excluded. However, at the outset the suggestions of 50 keywords/terms from the steering group helped ensure that a diverse and broad range of material was included. One limitation of this scoping review is that results are presented in a narrative style with limited quantitative analysis of retrieved studies. Whilst sample size and results are available in Table 3 , there was a low number of randomised controlled trials on this subject and suggests that the evidence is available about what supports hearing parents with deaf children are not adequately addressed. Despite these limitations this scoping review provides what we believe to be a first overview of existing research on supportive interventions and help for hearing parents with deaf children and serves to highlight the lack of evidence on this important topic.

Overall, the results of this scoping review about supports for hearing parents with deaf children suggest it is important to identify the journey parents and their children navigate from the results of hearing screening or deafness diagnosis, through to the available provision and supports from various services and providers. The results suggest that more research is needed to know what supports hearing parents with deaf children. We propose that further longitudinal studies should test and compare specific interventions and programmes in low-middle income countries and high-income countries. This scoping review highlights a need for improvement in the experience of hearing parents with deaf children as they, along with their deaf children, navigate challenges, information provision and supports required.

Supporting information

S1 checklist, funding statement.

This scoping review and the linked descriptive qualitative study are part of the SUPERSTAR project funded by Research Capacity Building Collaboration (RCBC) Wales, a Welsh Government funded scheme through Health and Care Research Wales, which exists to increase research capacity in nursing, midwifery, the allied health professions and pharmacists across Wales. The SUPERSTAR project is a Postdoctoral Fellowship, where the funder provides access to a supervisor, and a Community of Scholars to support and promote high research quality and outputs. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2023; 18(11): e0288771.

Decision Letter 0

19 Dec 2022

PONE-D-22-29952Systems that support hearing families with deaf children: a scoping reviewPLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Terry,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

Please submit your revised manuscript by Feb 02 2023 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols . Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols .

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Gursimran Dhamrait, Ph.D

Academic Editor

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf