- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Ulysses S. Grant

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 30, 2020 | Original: October 29, 2009

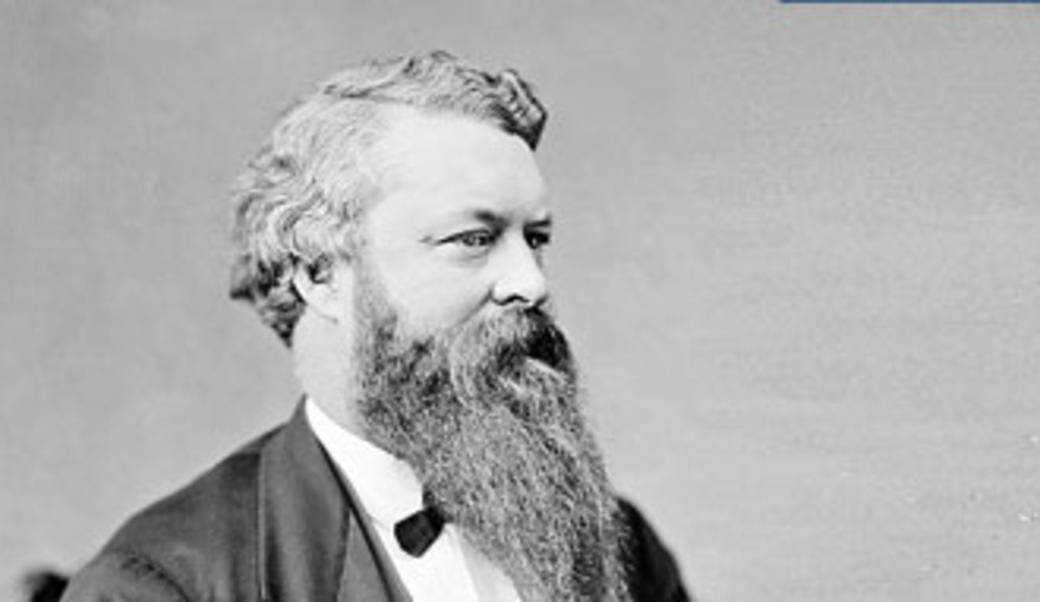

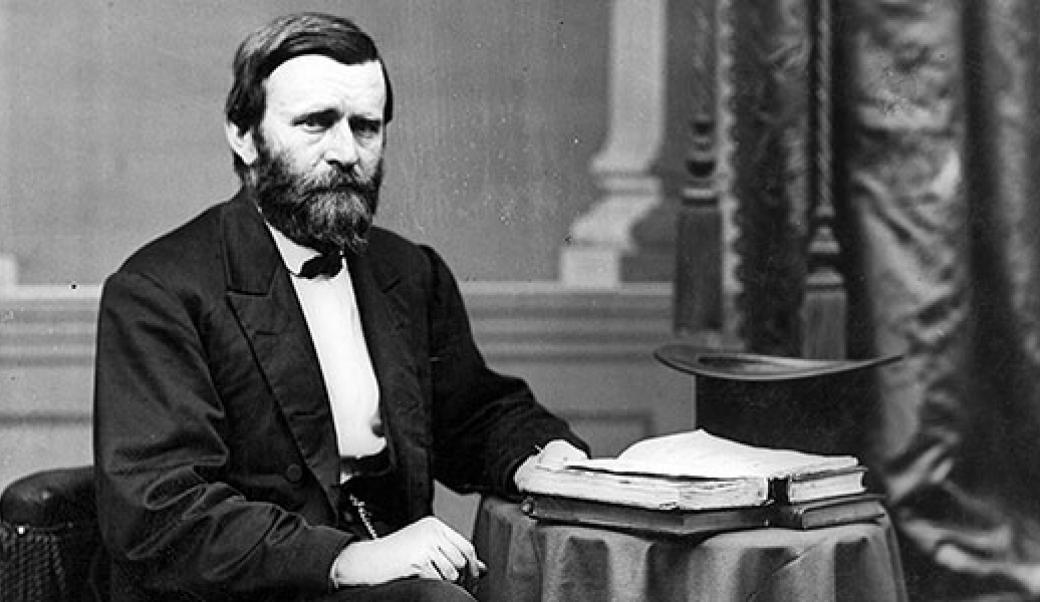

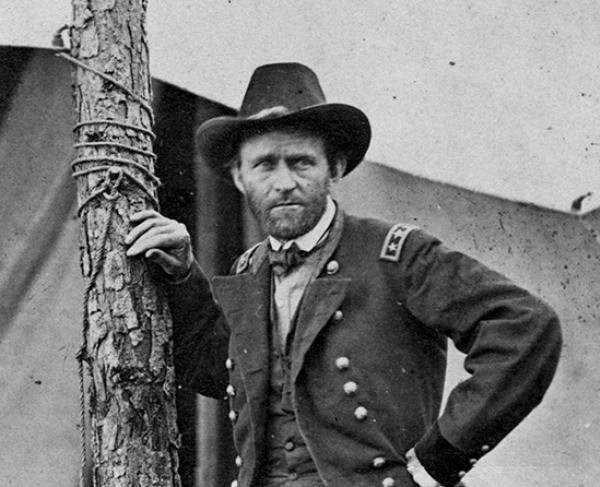

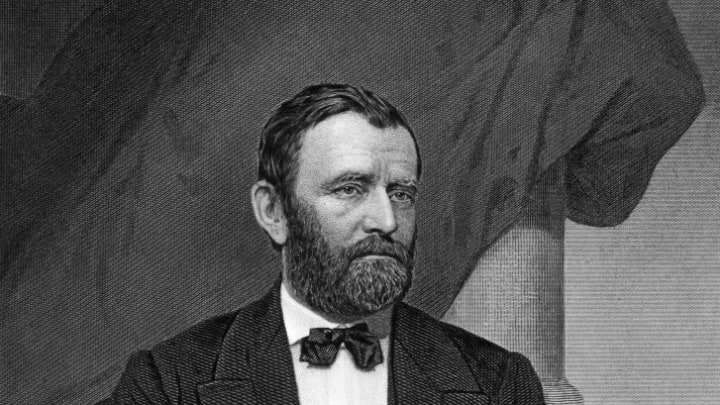

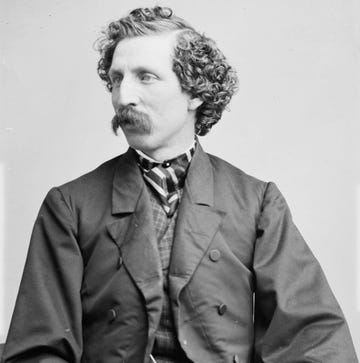

Ulysses Grant (1822-1885) commanded the victorious Union army during the American Civil War (1861-1865) and served as the 18th U.S. president from 1869 to 1877. An Ohio native, Grant graduated from West Point and fought in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). During the Civil War, Grant, an aggressive and determined leader, was given command of all the U.S. armies.

After the war, he became a national hero, and the Republicans nominated him for president in 1868. A primary focus of Grant’s administration was Reconstruction, and he worked to reconcile the North and South while also attempting to protect the civil rights of newly freed black slaves. While Grant was personally honest, some of his associates were corrupt and his administration was tarnished by various scandals. After retiring, Grant invested in a brokerage firm that went bankrupt, costing him his life savings. He spent his final days penning his memoirs, which were published the year he died and proved a critical and financial success.

Ulysses Grant’s Early Years

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio . The following year, he moved with his parents, Jesse Grant (1794-1873) and Hannah Simpson Grant (1798-1883), to Georgetown, Ohio, where his father ran a tannery.

Did you know? Thousands of people worldwide donated a total of $600,000 for the construction of Grant's tomb in New York City. Known officially as the General Grant National Memorial, it is America's largest mausoleum and was dedicated on April 27, 1897, the 75th anniversary of Grant's birth.

In 1839, Jesse Grant arranged for his son’s admission to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point . The congressman who appointed Grant mistakenly believed his first name was Ulysses and his middle name was Simpson (his mother’s maiden name). Grant never amended the error and went on to accept Ulysses S. Grant as his real name, although he maintained that the “S” did not stand for anything.

In 1843, Grant graduated from West Point, where he was known as a skilled horseman but an otherwise undistinguished student. He was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry, which was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri , near St. Louis. The following year, he met Julia Dent (1826-1902), the sister of one of his West Point classmates and the daughter of a merchant and planter.

After seeing action in the Mexican-American War , Grant returned to Missouri and married Julia in August 1848. The couple eventually had four children: Frederick Dent Grant, Ulysses S. Grant, Jr., Nellie Grant and Jesse Root Grant. In the early years of his marriage, Grant was assigned to a series of remote army posts, some of them on the West Coast, which kept him separated from his family. In 1854, he resigned from the military.

Ulysses Grant and the Civil War

Now a civilian, Ulysses Grant was reunited with his family at White Haven, the Missouri plantation where Julia had grown up. There he made an unsuccessful attempt at farming, followed by a failed stint in a St. Louis real estate office. In 1860, the Grants moved to Galena, Illinois , where Ulysses worked in his father’s leather goods business.

After the Civil War began in April 1861, Grant became a colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteers. Later that summer, President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) made Grant a brigadier general. Grant’s first major victory came in February 1862, when his troops captured Fort Donelson in Tennessee . When the Confederate general in charge of the fort asked about terms of surrender for the Battle of Fort Donelson , Grant famously replied, “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.”

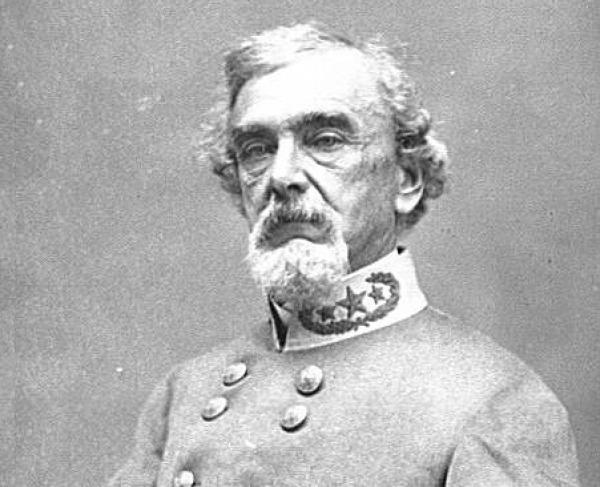

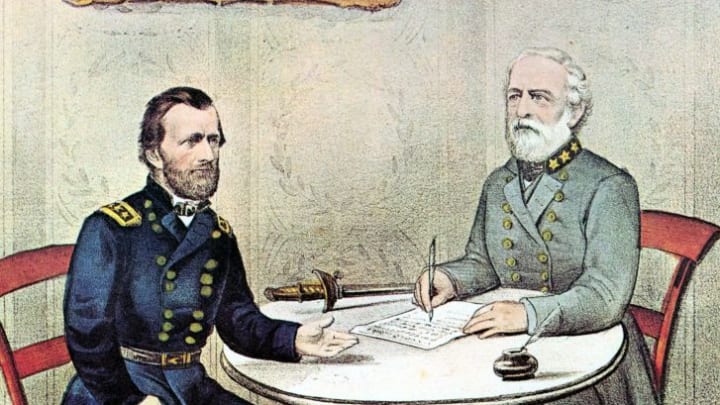

In July 1863, Grant’s forces captured Vicksburg, Mississippi , a Confederate stronghold. Grant, who was earning a reputation as a tenacious and determined leader, was appointed lieutenant-general by Lincoln on March 10, 1864, and given command of all U.S. armies. He led a series of campaigns that ultimately wore down the Confederate army and helped bring the deadliest conflict in U.S. history to a close. On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert Lee (1807-1870) surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia , effectively ending the Civil War.

Five days later, on April 14, Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865) while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Grant, and his wife had been invited to accompany the president that night but declined in order to visit family.

Ulysses S. Grant: An Interactive Map of His Key Civil War Battles

Grant is credited with winning the Civil War and preserving the American Union. This map charts his achievements during the nation’s most wrenching conflict.

From War Hero to President

Following the war, Ulysses Grant became a national hero, and in 1866 was appointed America’s first four-star general at the recommendation of President Andrew Johnson (1808-1875). By the summer of 1867, tensions were running high between Johnson and the Radical Republicans in Congress, who favored a more aggressive approach to Reconstruction in the South.

The president removed a vocal critic of his policies, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (1814-1869), from the Cabinet and replaced him with Grant. Congress charged that Johnson was in violation of the Tenure of Office Act and demanded Stanton’s reinstatement. In January 1868, Grant resigned the war post, thereby breaking with Johnson, who was later impeached but acquitted by a single vote in May 1868.

That same month, the Republicans nominated Grant as their presidential candidate, selecting Schuyler Colfax (1823-1885), a U.S. congressman from Indiana , as his running mate. The Democrats chose former New York governor Horatio Seymour (1810-1886) as their presidential nominee, paired with Francis Blair (1821-1875), a U.S. congressman from Missouri. In the general election, Grant won by an electoral margin of 214-80 and received more than 52 percent of the popular vote. At age 46, he became the youngest president-elect in U.S. history up to that time.

Ulysses Grant in the White House

Ulysses Grant entered the White House in the middle of the Reconstruction era, a tumultuous period in which the 11 Southern states that seceded before or at the start of the Civil War were brought back into the Union. As president, Grant tried to foster a peaceful reconciliation between the North and South. He supported pardons for former Confederate leaders while also attempting to protect the civil rights of freed slaves.

In 1870, the 15th Amendment , which gave black men the right to vote, was ratified. Grant signed legislation aimed at limiting the activities of white terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan that used violence to intimidate blacks and prevent them from voting. At various times, the president stationed federal troops throughout the South to maintain law and order. Critics charged that Grant’s actions violated states’ rights, while others contended that the president did not do enough to protect freedmen.

In addition to focusing on Reconstruction, Grant signed legislation establishing the Department of Justice, the Weather Bureau (now known as the National Weather Service) and Yellowstone National Park, America’s first national park. He also tried, with limited success, to improve conditions for Native Americans.

Grant’s administration made strides in foreign policy by negotiating the 1871 Treaty of Washington, which settled U.S. claims against England stemming from the activities of British-built Confederate warships that disrupted Northern shipping during the Civil War. The treaty resulted in improved relations between the United Kingdom and the United States. Less successful was Grant’s failed attempt to annex the Caribbean nation of Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic).

In 1872, a group of Republicans who opposed Grant’s policies and believed he was corrupt formed the Liberal Republican Party. The group nominated New York newspaper editor Horace Greeley (1811-1872) as their presidential candidate. The Democrats also nominated Greeley, hoping the combined support would defeat Grant. Instead, the president and his running mate Henry Wilson (1812-1875), a U.S. senator from Massachusetts , won the general election by an electoral margin of 286-66 and received close to 56 percent of the popular vote.

During Grant’s second term, he had to contend with a lengthy and severe depression that struck the nation in 1873 as well as various scandals that plagued his administration. He also continued to grapple with issues related to Reconstruction. Grant did not seek a third term, and Republican Rutherford Hayes (1822-1893), the governor of Ohio, won the presidency in 1876.

Ulysses Grant Scandals

Ulysses Grant’s time in office was marked by scandal and corruption, although he himself did not participate in or profit from the misdeeds perpetrated by some of his associates and appointees. During his first term, a group of speculators led by James Fisk (1835-1872) and Jay Gould (1836-1892) attempted to influence the government and manipulate the gold market. The failed plot resulted in a financial panic on September 24, 1869, known as Black Friday. Even though Grant was not directly involved in the scheme, his reputation suffered because he had become personally associated with Fisk and Gould prior to the scandal.

Another major scandal was the Whiskey Ring, which was exposed in 1875 and involved a network of distillers, distributors and public officials who conspired to defraud the federal government of millions in liquor tax revenue. Grant’s private secretary, Orville Babcock (1835-1884), was indicted in the scandal; however, the president defended him and he was acquitted.

Grant’s presidency occurred during an era dominated by machine politics and the patronage system of political appointments, in which politicians rewarded their supporters with government jobs and the employees, in turn, kicked back part of their salaries to the political party. In order to combat the corruption and inefficiency that resulted from this system, Grant established a civil service commission to develop more equitable methods for hiring and promoting government workers. However, civil service reform faced opposition from Congress and members of Grant’s administration, and by 1876 the commission’s funding was cut off and reform rules such as standardized exams were discontinued. Lasting reform did not take hold until 1883 when President Chester Arthur (1829-1886) signed the Pendleton Civil Service Act.

Ulysses Grant’s Later Years

After leaving the White House in March 1877, Ulysses Grant and his family embarked on a two-year trip around the world, during which they met with dignitaries and cheering crowds in many of the countries they visited. At the 1880 Republican National Convention, a group of delegates voted to nominate Grant for president again; however, James Garfield (1831-1881), a U.S. congressman from Ohio, ultimately earned the nomination. He would go on to win the general election and become the 20th U.S. president before being assassinated in 1881.

In 1881, Grant bought a brownstone on New York City’s Upper East Side. He invested his savings in a financial firm in which his son was a partner; however, the firm’s other partner swindled its investors in 1884, causing the business to collapse and bankrupt Grant. To provide for his family, the former president decided to write his memoirs. In late 1884, he was diagnosed with throat cancer.

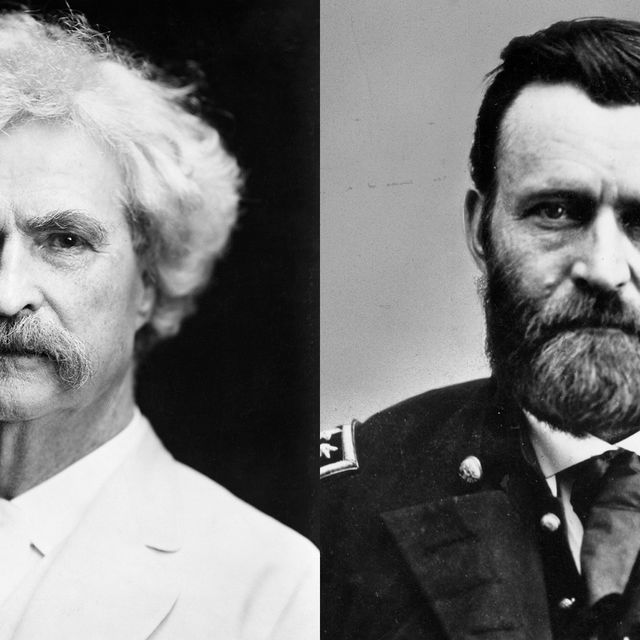

Grant died at age 63 on July 23, 1885, in Mount McGregor, New York, in the Adirondack Mountains, where he and his family were spending the summer. His memoirs, published that same year by his friend Mark Twain (1835-1910), became a major financial success.

More than a million people gathered in New York City to witness Grant’s funeral procession. The former president was laid to rest in a tomb in New York City’s Riverside Park. When Julia Grant died in 1902, she was buried beside her husband.

Ulysses Grant Quotes

“The friend in my adversity I shall always cherish most. I can better trust those who have helped to relieve the gloom of my dark hours than those who are so ready to enjoy with me the sunshine of my prosperity.”

“In every battle there comes a time when both sides consider themselves beaten. Then he who continues the attack wins.”

“There are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice.”

“The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

Ulysses S. Grant

The 18th President of the United States

The biography for President Grant and past presidents is courtesy of the White House Historical Association.

In 1865, as commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant led the Union Armies to victory over the Confederacy in the American Civil War. As an American hero, Grant was later elected the 18th President of the United States (1869–1877), working to implement Congressional Reconstruction and to remove the vestiges of slavery.

Late in the administration of Andrew Johnson, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant quarreled with the President and aligned himself with the Radical Republicans. He was, as the symbol of Union victory during the Civil War, their logical candidate for President in 1868.

When he was elected, the American people hoped for an end to turmoil. Grant provided neither vigor nor reform. Looking to Congress for direction, he seemed bewildered. One visitor to the White House noted “a puzzled pathos, as of a man with a problem before him of which he does not understand the terms.”

Born in 1822, Grant was the son of an Ohio tanner. He went to West Point rather against his will and graduated in the middle of his class. In the Mexican War he fought under Gen. Zachary Taylor.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant was working in his father’s leather store in Galena, Illinois. He was appointed by the Governor to command an unruly volunteer regiment. Grant whipped it into shape and by September 1861 he had risen to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers.

He sought to win control of the Mississippi Valley. In February 1862 he took Fort Henry and attacked Fort Donelson. When the Confederate commander asked for terms, Grant replied, “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.” The Confederates surrendered, and President Lincoln promoted Grant to major general of volunteers.

At Shiloh in April, Grant fought one of the bloodiest battles in the West and came out less well. President Lincoln fended off demands for his removal by saying, “I can’t spare this man–he fights.”

For his next major objective, Grant maneuvered and fought skillfully to win Vicksburg, the key city on the Mississippi, and thus cut the Confederacy in two. Then he broke the Confederate hold on Chattanooga.

Lincoln appointed him General-in-Chief in March 1864. Grant directed Sherman to drive through the South while he himself, with the Army of the Potomac, pinned down Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Finally, on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Lee surrendered. Grant wrote out magnanimous terms of surrender that would prevent treason trials.

As President, Grant presided over the Government much as he had run the Army. Indeed he brought part of his Army staff to the White House.

Although a man of scrupulous honesty, Grant as President accepted handsome presents from admirers. Worse, he allowed himself to be seen with two speculators, Jay Gould and James Fisk. When Grant realized their scheme to corner the market in gold, he authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to sell enough gold to wreck their plans, but the speculation had already wrought havoc with business.

During his campaign for re-election in 1872, Grant was attacked by Liberal Republican reformers. He called them “narrow-headed men,” their eyes so close together that “they can look out of the same gimlet hole without winking.” The General’s friends in the Republican Party came to be known proudly as “the Old Guard.”

Grant allowed Radical Reconstruction to run its course in the South, bolstering it at times with military force.

After retiring from the Presidency, Grant became a partner in a financial firm, which went bankrupt. About that time he learned that he had cancer of the throat. He started writing his recollections to pay off his debts and provide for his family, racing against death to produce a memoir that ultimately earned nearly $450,000. Soon after completing the last page, in 1885, he died.

Learn more about Ulysses S. Grant’s spouse, Julia Dent Grant .

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

Help inform the discussion

U.S. Presidents / Ulysses S. Grant

1822 - 1885

Ulysses s. grant.

It was my fortune, or misfortune, to be called to the office of Chief Executive without any previous political training. Eighth Annual Message

Ulysses S. Grant is best known as the Union general who led the United States to victory over the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. As a two-term President, he is typically dismissed as weak and ineffective; historians have often ranked Grant's presidency near the bottom in American history. Recently, however, scholars have begun to reexamine and reassess his presidential tenure; recent rankings have reflected a significant rise.

Life In Depth Essays

- Life in Brief

- Life Before the Presidency

- Campaigns and Elections

- Domestic Affairs

- Foreign Affairs

- Life After the Presidency

- Family Life

- Impact and Legacy

Chicago Style

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Ulysses S. Grant.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/grant.

Professor of History

Professor Waugh is a professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles.

- U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth

- War within a War: Controversy and Conflict over the American Civil War

- The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture

Featured Insights

Resignation was not the end

President Ulysses S. Grant's secretary of war, William W. Belknap, was impeached and he resigned, but the US Senate went ahead with his trial

President Grant: A case of misfortune?

Learn why scholars are re-examining Grant’s presidency

The "General" election: Ulysses S. Grant

Learn more about how General Grant, who had no political experience, got elected

Why remember the Civil War?

Historian Gary Gallagher discusses why the Civil War still holds such a grip on the American imagination 150 years later and what we most need to remember from that conflict

March 4, 1869: First Inaugural Address

January 13, 1875: message regarding intervention in louisiana, december 5, 1876: eighth annual message, featured video.

U.S. Grant and the crisis of Reconstruction

Watch Joan Waugh, professor in the UCLA history department, talk about the crisis of Reconstruction

Featured Publications

Ulysses S. Grant

Born Hiram Ulysses Grant, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, the future General-in-Chief's name was changed due to a clerical error during his first days at the United States Military Academy at West Point. To his friends, however, he was known simply as "Sam." After a mediocre stint as a cadet, he graduated twenty-first out of the thirty-nine cadets in class of 1843. Yet despite his less than exemplary school record, he performed well as a captain during the Mexican War (1846-1848), winning two citations for gallantry and one for meritorious conduct. Only when the fighting stopped and Grant was assigned monotonous duties at remote posts far from his wife and family did he again begin neglecting his work and drinking heavily. He resigned in 1854 to avoid being drummed out of the service.

Grant spent the next six years in St. Louis, Missouri with his wife, Julia Dent Grant. After several short-lived pursuits, including a brief episode as a farmer, he moved to Galena, Illinois to be a clerk in his family's store. When the Civil War began in 1861, he jumped at the chance to volunteer for military service in the Union army. His first command was as the colonel of the 21st Illinois Infantry, but he was quickly promoted to brigadier general in July 1861, and in September was given command of the District of Southeast Missouri.

His 1862 triumphs at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in western Tennessee won him the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, and placed him before the public eye. However, when a surprise attack by Confederate forces at the Battle of Shiloh yielded devastating casualties during the first day's fighting, President Abraham Lincoln received several demands for Grant's removal from command. Nevertheless, Lincoln refused, stating, “I can’t spare this man. He fights.” The following day, Grant's Army - bolstered by troops under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell - fended off Confederate advances and ultimately won the day.

Grant’s hard-won victory at Vicksburg , Mississippi, in May of 1863 was a strategic masterpiece. On May 1, 1863, Grant's army crossed the Mississippi River at the battle of Port Gibson. With Confederate forces unclear of his intentions, Grant sent a portion of his army under Gen. William T. Sherman to capture the state capital, Jackson, while setting his sights on Vicksburg with a view toward permanently closing the Confederate supply base. When initial assaults on the city demonstrated the strength of Vicksburg's defenses, the Union army was forced to lay siege to the city. On July 4, 1863, after 46 days of digging trenches and lobbing hand grenades, Confederate general John Pemberton 's 30,000-man army surrendered. Coupled with the Northern victory at Gettysburg , the capture of Vicksburg marked the turning point in the war. It also made Grant the premier commander in the Federal army. Later that same year, Grant was called upon to break the stalemate at Chattanooga , further cementing his reputation as a capable and effective leader.

In March 1864, President Lincoln elevated Grant to the rank of lieutenant general, and named him general-in-chief of the Armies of the United States. Making his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, Grant was determined to crush Robert E. Lee and his vaunted Army of Northern Virginia at any cost. Though plagued by reticent subordinates, petty squabbles between generals and horrific casualties, the Federal host bludgeoned Lee from the Rapidan River to the James in what one participant would later describe as "unspoken, unspeakable history." The battles of the Wilderness , Spotsylvania , Cold Harbor and the subsequent siege of Petersburg effectively destroyed the rebel army, leading to the fall of Richmond and Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House . Though Grant’s forces had been depleted by more than half during the last year of the war, it was Lee who surrendered in 1865.

After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson named Grant Secretary of War over the newly reunited nation. In 1868, running against Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant was elected eighteenth President of the United States. Unfortunately, though apparently innocent of graft himself, Grant’s administration was riddled with corruption, and scandal.

For two years following his second term in office, Grant made a triumphal tour of the world. In 1884, he lost his entire savings to a corrupt bank. To make up some of his losses, he wrote about his war experiences for Century Magazine. They proved so popular that he was inspired to write his excellent autobiography, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant , finishing the two-volume set only a few days before dying of cancer at the age of sixty-three. Ulysses S. Grant is buried in New York City in the largest mausoleum of its kind in the United States. Reminiscent of Napoleon's tomb in Paris, Grant's tomb is a National Memorial.

Benjamin Huger

Alexander Hays

Carl Schurz

You may also like.

Ulysses S. Grant

By jake rossen | mar 13, 2020.

MILITARY (1822–1885); POINT PLEASANT, OHIO

Fresh off his victory as commander of the Union armies during the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) became President of the United States in March 1869. While his time in office wasn’t without controversy, Grant has taken his place among the most fascinating of the country’s leaders. Today, you can find him on the $50 bill and the $1 coin that was issued in 2011. For more on Grant, including the mystery of his middle name, keep reading.

1. Ulysses S. Grant’s Civil War victories are legendary.

Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, to parents Jesse and Hannah Grant. He was raised in Georgetown, Ohio, and eventually passed on an opportunity to follow his father into the tannery, or leather, business. Instead, he opted to join the United States Military Academy at West Point at the age of 17. After graduating, he wed Julia Dent and served during the Mexican-American War, before resigning from the military in 1854.

But it was the Civil War that made Grant’s name. He returned to the army when the war broke out, starting as commander of the 21st Illinois Volunteers on his way to eventually becoming Commanding General of the United States Army. During the war, Grant earned several major victories on behalf of the Union:

- Grant led the charge in the Battle of Fort Henry in Tennessee in February 1862, scoring the first major Union win in the war.

- Grant also took Fort Donelson that same month, each time forcing Confederates to surrender. Both are credited as being two crucial victories for the Union, allowing them to take control of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

- Grant conquered the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee in April 1862, said to be among the most violent of the conflict. After two days of fighting and the fatal wounding of Confederate commander Albert Sidney Johnston, the Union beat back Confederate forces.

- In Vicksburg, Mississippi, Grant cut off supplies to Confederates and laid siege to their key city, overwhelming them and breaking their forces into smaller groups. They surrendered on July 4, 1863.

- In November 1863, Grant led Union forces in the Battle of Chattanooga in Tennessee, which included Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. Enemy forces retreated to Georgia, leaving a key railroad junction under Union control.

- Now serving as a lieutenant general of the entire U.S. Army, Grant spent 1864 and 1865 advancing on General Robert E. Lee’s men in Virginia. Losing men rapidly, Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, ending the war.

2. Ulysses S. Grant had no formal middle name.

The “S” in Ulysses S. Grant has long invited questions about his middle name. If you don’t recall ever hearing it, that’s because he doesn’t actually have one. Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant. When he enlisted in the U.S. Military Academy, a paperwork error had him listed as “Ulysses S. Grant.” Rather than get tied up in the confusion, Grant simply accepted the change in his name. The “S” would later come in handy, as his Civil War victories led to people nicknaming him “U.S. Grant” and “Unconditional Surrender Grant.”

3. Ulysses S. Grant was said to be unflappable.

Part of what made Grant such an effective military leader was a seeming sense of impermeability. Grant was said to be very steady and not easily excited. One Union officer who knew him wrote that Grant “habitually wears an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall, and was about to do it.” Once, Grant was sitting for a photographer when the photographer’s assistant fell through a skylight. Glass shards fell right next to Grant, who remained sitting, not moving an inch.

4. As president, Ulysses S. Grant was not necessarily the most qualified.

Following his contributions to winning the Civil War, Grant had unmatched support among Union states and Republicans. When then-President Andrew Johnson was impeached following a controversy over the inappropriate firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Grant was elected to office in 1868. But his history was in military service, not politics, and some felt Grant was lost in the role as a world leader. He was said to look to Congress for guidance, as well as numerous military servicemen he brought to the White House.

Even so, Grant still implemented positive changes while in office. He signed the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, granting black men the right to vote, and supported improved government relations with Native Americans. And in 1872, he signed legislation that named Yellowstone the country’s first national park.

5. Ulysses S. Grant's presidency was not without controversy.

While Grant was never personally involved in any of the wrongdoing while in office, he had a knack for being associated with impropriety. Early on, gold speculators James Fisk and Jay Gould tried to manipulate the market by influencing the government, causing a mass panic on September 24, 1869, that came to be known as Black Friday. Because Grant knew Fisk and Gould personally, the president came under scrutiny. Later, in 1875, Grant’s private secretary, Orville Babcock, was involved in the Whiskey Ring, a network of alcohol distributors that conspired to avoid paying the government liquor tax revenue. Despite these gaffes, Grant was a proponent of civil service reform and established a civil service commission to examine the fair hiring and termination of workers. (Congress, unfortunately, withheld funding .)

6. Ulysses S. Grant toured the world.

Following his two terms as president, Grant, his wife Julia, and their youngest son, Jesse, decided to embark upon an ambitious world tour that would take two and a half years. Departing from Philadelphia in 1877, the Grant family traveled with New York Herald reporter John Russell Young. The first stop was England, where they visited Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. Though cordial, the Queen was famously irritated that Jesse, 19, had come along, describing him as a "very ill-mannered young Yankee." The Grants also made their way through Western Europe, then to Egypt, Greece, Rome, Russia, Austria, Germany, Burma, Singapore, and Vietnam, before returning to America on December 16, 1879.

7. Ulysses S. Grant got help from Mark Twain for his memoirs.

Following his two terms as president, Grant decided to start a career in investment banking, but the firm he was involved in wound up being disreputable. Turns out, his partner, Ferdinand Ward, was embezzling money from his clients and partners, including Grant and his son Buck. Broke and newly diagnosed with throat cancer, Grant turned to his sole remaining source for funds—writing his memoirs.

When he was going to sign a publishing deal that would award him 10 percent royalties, his friend Mark Twain, who Grant had grown close to after several meetings during and after his presidency, was appalled. Twain offered to publish the memoirs at Charles L. Webster & Co., the publishing house he established in 1884. The new royalty rate would be 20 percent, and Twain gave Grant $1000 for living expenses (the former president wouldn't accept a bigger advance out of fear that his book would lose money for Twain).

Twain supervised Grant's writing, and on July 20, 1885, the memoirs were finally finished. Grant died just three days later. When The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant was released that December, it was a resounding success and acted as a kind of inheritance for his widow, Julia. She earned $450,000 in royalties from sales of the book.

Famous Ulysses S. Grant Quotes

- “Although a soldier by profession, I have never felt any sort of fondness for war, and I have never advocated it, except as a means of peace.”

- “Labor disgraces no man; unfortunately, you occasionally find men who disgrace labor.”

- “I don't underrate the value of military knowledge, but if men make war in slavish obedience to rules, they will fail.”

- “In every battle there comes a time when both sides consider themselves beaten, then he who continues the attack wins.”

- “To maintain peace in the future it is necessary to be prepared for war.”

What can we help you find?

While we certainly appreciate historical preservation, it looks like your browser is a bit too historic to properly view whitehousehistory.org. — a browser upgrade should do the trick.

Main Content

Ulysses S. Grant

On April 27, 1822, Ulysses S. Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio. Grant’s father, Jesse, was a tanner and an abolitionist. Grant received an education from several private schools and later attended the United States Military Academy at West Point. After graduating in the middle of his class, Grant was stationed in Missouri where he visited with his former classmate and friend, Fred Dent. During the visit, Grant met Fred’s sister, Julia, and fell in love with her. In 1848, they married and would go on to raise four children together.

After the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, Grant fought under General Zachary Taylor before resigning from the military in 1854. Julia, Ulysses, and their children moved back to her father’s plantation, White Haven, in Missouri. Grant became a plantation manager, overseeing the enslaved and free laborers while working alongside them. While there are no known documents or letters related to a bill of sale, Grant did emancipate a man named William Jones in 1859. According to the signed manumission, Jones was “purchased by me [Grant] of Frederick Dent.” Jones is the only known enslaved individual who was owned by Grant—though his decision to free William rather than sell him, especially as he struggled financially, suggests that Grant had personal discomfort with slave ownership. Julia, however, had no qualms about using enslaved labor within her household and she considered those owned by her father Frederick Dent as her own. Click here to learn more about the enslaved households of President Ulysses Grant.

At the onset of the Civil War, the Grants were living in Illinois after the family suffered more financial setbacks in Missouri. Ulysses was working in his father's leather store in Galena when Governor John Wood appointed him commander of an unruly volunteer regiment. By September 1861, Grant had instilled order and discipline within the unit and was rewarded with a promotion to brigadier general of the volunteer force.

In his new position, Grant captured Fort Henry and attacked Fort Donelson. When the Confederate commander asked for Grant’s terms, he replied, "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted." The Confederates surrendered, and President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to major general of volunteers. A few months later, Grant secured a hard-fought victory at the Battle of Shiloh, one of the bloodiest battles in the Western Theater. The casualties concerned some officials enough to call for Grant’s removal. President Lincoln defended Grant by saying, "I can't spare this man, he fights."

Grant then turned his attention to Vicksburg—its location on the banks of the Mississippi River made it a key city for moving troops and supplies. On July 4, 1863, Confederate troops surrendered to Grant after a two-month siege, even though many had considered the fort at Vicksburg impregnable. Grant then followed this success by capturing Chattanooga and its important railroad depot, pushing Confederates back into Georgia. In March 1864, Lincoln appointed Grant general-in-chief. Grant’s success can be credited to his military strategies and maneuvers, which made him remarkably different from his predecessors. He engaged the enemy in all theatres, drawing them into the open while exhausting their resources. His tactical planning and pursuit of General Robert E. Lee’s forces brought the war to a close on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. With Lincoln’s approval, General Grant offered generous terms of surrender that would prevent treason trials and executions.

During the years immediately following the war, General Ulysses S. Grant criticized President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction plan and aligned himself with Radical Republicans. In the 1868 election, Grant, a military hero and symbol of the Union victory, won in a landslide.

President Grant sent federal troops to the South to enforce civil rights legislation and protect African Americans from civil and political violence. With the assistance of Congress, Grant created the Department of Justice and instructed Attorney General Amos T. Akerman to suppress the newly formed Ku Klux Klan’s efforts to disenfranchise and terrorize black communities.

Although personally a man of unquestioned honesty, Grant’s reputation suffered from those around him. The president was often seen with two of his friends, speculators Jay Gould and James Fisk. When Grant discovered their scheme to corner the market in gold, he authorized Secretary of the Treasury George Boutwell to sell enough gold to undermine their plans. The speculation had already damaged the American economy, however, and Grant took the blame for his poor judgment in associates. Some Republican reformers seized on the scandal, accused the administration of corruption, and nominated Horace Greeley for president. The general's allies in the Republican Party were able to fend off these attacks and Grant was reelected with an overwhelming majority of the vote in 1872. However, scandal continued to follow his administration, most notably in 1875 with the discovery of the Whiskey Ring. This was an extensive network of distillers, intermediaries, and government officials who engaged in bribery and extortion to avoid federal taxes on liquor. President Grant’s private secretary, Orville E. Babcock, was indicted as part of the investigation but later acquitted when Grant testified on his behalf.

After retiring from the presidency, Grant’s long history of financial struggles continued. He joined a financial firm, which went bankrupt, and then learned he was suffering from throat cancer in late 1884. He worked furiously to write his memoirs to pay off his debts and provide for his family. These memoirs, completed just before he died on July 23, 1885, earned nearly $450,000. Grant’s autobiography was lauded for its lucid prose and compelling story. Grant argued that the Mexican-American War and the expansion of slavery ultimately drove the country toward civil war. It is still regarded as one of the best first-hand accounts of the Civil War.

Related Information

- Julia Grant

Portrait Painting

You might also like, the american presidents song.

The origin of the "American Presidents" by Genevieve Ryan Bellaire is somewhat unique. One year, Genevieve's father asked her to memorize the order of the Presidents of the United States for Father's Day. As she did, she began to come up with rhymes to help her remember each President. After sharing this method with her family, they told her that

The Presidents and the Theatre

Read Digital Edition Foreword, William SealeThe Man Who Came to Dinner at the White House: Alexander Woollcott Visits the Roosevelts, Mary Jo Binker The Curse of the Presidential Musical: Mr. President and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Amy HendersonFord's Theatre and the White House, William O'Brien The American Presidents and Shakespeare, Paul F. Boller Jr.Opera for the President: Superstars and Song in

International Presidents’ Day Wreath Laying

Carriages of the presidents.

Before the twentieth century, the presidents' vehicles were not armored-plated or specially built. Their carriages were similar to those of citizens of wealth. Often they were gifts from admirers. George Washington had the most elaborate turn out of the presidents for state occasions, sporting a cream-colored carriage drawn by six matched horses "all brilliantly caparisoned." Coachmen and footmen wore livery

Presidents at the Races

No sport created more excitement, enthusiasm and interest in the colonial period and the early republic than horse racing. Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson took immense pride in their horses and bred them to improve the bloodlines of saddle, work, carriage and racehorses. Early presidents loved horse racing, the most popular sport in America at that time. George Washington,

The Presidents and Sports

Read Digital Version Forward by William SealeThe Presidents and Baseball: Presidential Openers and Other Traditions by Frederic J. FrommerUlysses S. Grant's White House Billiard Saloon by David RamseyTheodore Roosevelt: The President Who Saved Football by Mary Jo BinkerHoover Ball and Wellness in the White House by Matthew SchaeferCapturing A Moment in Time: Remembering My Summer Photographing President Eisenhower by Al

St. John’s, the Church of the Presidents

Featuring Rev. Robert Fisher, Rector at St. John’s Church

The Historic Stephen Decatur House

In 1816, Commodore Stephen Decatur, Jr. and his wife Susan moved to the nascent capital city of Washington, D.C. With the prize money he received from his naval feats, Decatur purchased the entire city block on the northwest corner of today’s Lafayette Square. The Decaturs commissioned Benjamin Henry Latrobe, one of America’s first professional architects, to design and buil

250 Years of American Political Leadership

Featuring Iain Dale, award-winning British author and radio and podcast host

"The President's Own"

On July 11, 1798, Congress passed legislation that created the United States Marine Corps and the Marine Band, America's oldest professional musical organization. The United States Marine Band has been nicknamed "The President's Own" because of its historic connection to the president of the United States. At its origin, the fledgling band consisted of a Drum Major, a Fife Major and 32 drums

Dinner with the President

Featuring Alex Prud’homme, bestselling author and great-nephew of cooking legend Julia Child

The Decatur House Slave Quarters

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room, and laundry; while the second floor contained four rooms designated as living quarters. By 1827, the service wing was being used as an urban slave quarters. Henry Clay brought enslaved individuals to Decatur House, starting a trend that was solidified by

Ulysses S. Grant

April 27, 1822–July 23, 1885

Ulysses S. Grant was an American military and political leader who rose from humble beginnings to become general-in-chief of Union forces during the Civil War and, afterward, the eighteenth President of the United States.

Ulysses S. Grant rose from humble beginnings to become General-in-Chief of Union forces during the Civil War and, afterward, the eighteenth President of the United States. [ Wikimedia Commons ]

Ulysses S. Grant Biography

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States, serving two terms from 1869 to 1877. He was a Union general during the American Civil War and was known for his success in leading the North to victory. As president, Grant was committed to rebuilding the country after the war and to protecting the rights of African Americans in the South. However, his presidency was marked by corruption and scandal, particularly within his administration, and he is often criticized for his lack of political experience and poor judgment in choosing advisors.

Quick Facts About Ulysses S. Grant

- Date of Birth: Ulysses S. Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio.

- Parents: Grant’s parents were Jesse and Hannah (Simpson) Grant.

- Date of Death: Grant died on July 23, 1885, at age 63, in a cottage on Mount McGregor in Saratoga County, New York.

- Buried: Grant is buried in the General Grant National Memorial, also known as “Grant’s Tomb”, in New York City.

- Nickname: Grant’s nicknames were “Unconditional Surrender Grant,” “Uncle Sam,” and, “U.S. Grant.”

Ulysses Simpson Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio . His parents, Jesse and Hannah (Simpson) Grant, christened Hiram Ulysses Grant. In 1823, his family moved to Georgetown, Ohio. Grant attended public school in Georgetown, and the school of Richeson and Rand at Maysville, Kentucky (1836–1838), and the Presbyterian Academy at Ripley, Ohio (1838–1839). As a youth, Grant also worked at his father’s tannery, although he disliked the job.

U.S. Military Academy Cadet

In 1838, New York Congressman Thomas L. Harvey nominated Grant for an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Grant did not want to attend the academy, but his father insisted. When Grant arrived at West Point in 1839, he discovered Harvey had mistakenly listed his name on the application as Ulysses Simpson Grant. Grant adopted the name Ulysses S. Grant and insisted throughout his life that the initial “S” stood for nothing. While at West Point, he received the nickname, U.S. Grant.

U.S. Army Officer

Grant graduated from West Point on June 23, 1843, ranked twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine cadets. Army officials commissioned Grants as a brevet second lieutenant on July 1, 1843, and ordered him to report to the 4th U.S. Infantry at Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis, Missouri on September 30. While stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Grant often visited the home of his West Point roommate, Frederick Dent, near St. Louis. There he met and fell in love with Dent’s sister, Julia. The couple became secretly engaged in 1844, but they did not marry until August 22, 1848, after Grant returned from the Mexican-American War .

Mexican-American War

In June 1844, the army sent Grant and the 4th Infantry to Natchitoches, Louisiana. In September 1845, they sailed from New Orleans, bound for Corpus Christi, Texas, where a border dispute was brewing between the United States and Mexico. On March 11, 1846, forces serving under General Zachary Taylor invaded the disputed territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, prompting Mexico to declare war on April 23. Grant served as a quartermaster throughout the Mexican-American War, experiencing some combat at Palo Alto , Monterey , Molino del Rey , and San Cosme Garita.

Marriage and Antebellum Service

When the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, Grant returned to St. Louis and married Julia. On November 17, 1848, the army ordered him to Detroit, Michigan. Grant spent the next four years with Julia in Michigan and other more easterly posts, but in 1852, the army ordered west. Grant arrived at Fort Vancouver, Washington on September 20, 1852, unhappy about being separated from his family. With no prospect of reunion in sight, fellow officers reported Grant turned to alcohol to console himself. On September 30, 1853, Grant received notice that the army had promoted him to captain and ordered him to report to Fort Humboldt, California. After another lonely winter, Grant received his official commission as captain on April 11, 1854. He wrote a letter of resignation from the army on the same day. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis , future president of the Confederate States of America, accepted the letter of resignation.

Civilian Life

In 1854, Grant returned to St. Louis and reunited with his family. As a civilian, he first tried his hand as a farmer on the Dent family land. Appropriately, Grant named his farm “Hardscrabble.” Despite working hard, the farm provided little. From 1858 to 1859, Grant went into the real estate business with his wife’s cousin. During that period, Grant freed his one slave, William Jones, who was given to him by the Dent family. When the real estate venture failed, Grant moved to Galena, Illinois, in May 1860. There, he became a clerk in his father’s leather store.

Civil War Career

After the Battle of Fort Sumter (April 12–13, 1861)touched off the American Civil War, Grant volunteered for military duty. In June, he visited General George McClellan’s headquarters in Cincinnati, Ohio, but McClellan refused to see him. On June 15, he returned to Galena and accepted an appointment as a colonel in the Illinois militia. On July 31, at the urging of several Illinois congressmen, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln submitted a request to Congress to commission Grant as a brigadier general in the volunteer army, retroactively to May 17, 1861. Congress approved Lincoln’s request on August 9. On September 1, Western Department Commander Major General John C. Frémont selected Grant to command the District of Southeast Missouri, and Grant established his headquarters at Cairo, Illinois.

Grant’s first Civil War action took place in Missouri at the inconclusive Battle of Belmont (November 7, 1861). Grant intended to attack a Confederate force commanded by Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow , which had invaded Kentucky. As he approached the Confederate forces from Cairo, Grant learned Pillow had crossed the Mississippi River to Belmont, Missouri. Grant attacked there instead and initially drove the Confederates back. The Confederates rallied against Grant’s undisciplined soldiers after being reinforced. The battle ended when the Federals withdrew, with neither side proving much.

Capture of Fort Donelson and Fort Henry

By late 1861, President Lincoln was pressuring Union commanders in the west to invade the South. On December 20, 1861, Major General Henry W. Halleck issued Special Orders, No. 78 (Department of the Missouri) placing Grant in command of the reconfigured District of Cairo.

On January 30, 1862, Halleck reluctantly approved Grant’s request to attack Fort Henry on the eastern bank of the Tennessee River just south of the Tennessee-Kentucky border. Grant left Cairo, Illinois on February 2, with 15,000 soldiers, plus a flotilla of seven gunboats commanded by United States Navy Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. On February 4 and 5, Grant landed his force in two locations near Fort Henry and prepared for battle.

Confederate Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman realized he had little chance of defending Fort Henry against Grant’s sizable force. On February 5, Tilghman sent most of the occupants of Fort Henry to Fort Donelson, twelve miles to the east, leaving behind only a handful of artillerymen to defend the fort. By February 6, Foote’s flotilla maneuvered into position and began bombarding the fort. Seventy-five minutes later, Tilghman surrendered, ending the Battle of Fort Henry .

Following the surrender of Fort Henry, Grant turned his attention toward investing Fort Donelson, located on a hill on the west bank of the Cumberland River just south of the Tennessee-Kentucky border. Grant marched his army toward the Cumberland River on February 12 and 13. After traversing the twelve-mile span between the two forts, Grant positioned his troops in a semi-circle around the western side of Fort Donelson. On February 14, Foote’s flotilla traveled up the Cumberland River and attempted to reduce the fort with naval gunfire from the eastern side. The bombardment proved ineffective, however, because the Confederates held a higher position. Eventually, the Confederate fire forced Foote’s gunboats to withdraw, setting the stage for a land engagement.

On the morning of February 15, Confederate troops surged out of the fort, attacking the Union right flank. The Federals fell back in an orderly retreat. Grant ordered a counterattack on the left, forcing the Confederates back into a defensive position. By nightfall, the Yankees had reclaimed much of the ground that they had lost in the morning.

During the night, the Confederate commanders determined their situation was hopeless. The Federals awoke the next morning, surprised to see white flags of truce flying over Fort Donelson. The fort’s commander, Simon B. Buckner , requested an armistice and asked Grant for his terms of surrender. Grant replied that,

No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

Buckner had reason to believe that Grant would be more generous because of their personal relationship in the Union Army before the war. Nevertheless, he capitulated to what he termed Grant’s “ungenerous and unchivalrous terms.” In the battle’s aftermath, “Unconditional Surrender” Grant became an instant celebrity, earning him a promotion to major general of volunteers.

During the Battle of Fort Donelson , Halleck issued General Orders, No. 37 (Department of the Missouri) on February 14, 1862, assigning Grant to command of the newly created District of West Tennessee.

Battle of Shiloh

The fall of forts Henry and Donelson were serious blows to the Confederacy. The losses forced General Albert Sidney Johnston , the commander of Confederate forces in the West, to abandon Kentucky and solidify his position deeper in Tennessee. The fall of the two forts also provided the Federals with two major waterways in the West from which to launch an invasion of the South.

Halleck ordered Grant to march his army south to Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, near the Tennessee-Mississippi border, to await General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Halleck’s intention was to merge the two armies and then move south to cut the Memphis & Charleston Railroad line at Corinth, Mississippi.

By early April, Grant’s army of nearly 50,000 men encamped along the western side of the Tennessee River near Pittsburg Landing. Not believing that Johnston’s army was within striking distance, Grant used the time awaiting Buell’s arrival to drill his troops rather than construct defensive fortifications.

Johnston took advantage of Grant’s laxity. Rather than waiting to confront the combined Union armies at Corinth, Johnston launched a surprise attack on Grant’s exposed soldiers on the morning of April 6, 1862. In the ensuing confusion, many of the federal troops fled in panic. Others re-formed battle lines and mounted some resistance, but the Confederates gradually drove the Yankees back to a defensive position behind Shiloh Church.

As the Confederates pressed their advance, Union soldiers made a stand at a position, since popularized as the “Hornet’s Nest,” near a road now known as the “Sunken Road.” Although the Confederates killed or captured many of the Federals, the Yankees’ seven-hour standoff bought valuable time for Grant to reorganize his men and establish a final defensive line. During the fighting, Union soldiers mortally wounded General Johnston, and General P. G. T. Beauregard assumed command of the Confederate forces.

When the Battle of Shiloh began, Grant was about ten miles downriver at Savannah, Tennessee, nursing a swollen ankle, which had him on crutches, from a horse-fall the day before. Upon hearing the sounds of the battle, Grant rushed to the scene, arriving about 8:30 a.m., and began re-establishing order amongst his troops. As the first day of the battle concluded, the Confederate advance had spent itself, and Grant had set up a defensive line near the river.

Beauregard attempted a final assault during the early evening, which the Federals repulsed. At that point, Beauregard called off the attack. That night, the overly confident Confederate general sent a telegram to Confederate President Jefferson Davis proclaiming “A complete victory.” Beauregard went to bed expecting to drive Grant’s army across the Tennessee River the next day. Grant, however, had established a strong position, and reinforcements from Buell’s army arrived as Beauregard slept.

The size of the two armies engaged at the Battle of Shiloh was about equal on the first day. When Beauregard awoke on the second day, the Yankees had him outnumbered. On the morning of April 7, 1862, to Beauregard’s surprise, Grant and Buell launched a counterattack that drove the Confederates back.

Despite several attempts to counterattack, the Confederates gradually lost the ground that they had captured the previous day. Eventually, Beauregard knew he had lost, and he began an orderly retreat to Corinth. To Buell’s dismay, Grant chose not to pursue the retreating Confederates. Except for a short cavalry encounter at a place called Fallen Timbers on April 8, the Battle of Shiloh had ended.

Relieved of Command

Although the Army of the Tennessee prevailed at the Battle of Shiloh, the Northern press blamed Grant for being surprised by Johnston’s attack. Rumors circulated Grant was drunk as Confederates bayoneted Union soldiers in their tents as they slept. After two weeks of criticism, Halleck reacted. On April 28, 1862, he issued Special Orders, No. 31 (Department of the Mississippi). The dispatch merged the Army of the Tennessee, the Army of the Ohio, and the Army of the Mississippi to form one large army comprising three corps commanded by Halleck. Two days later, Halleck issued Special Field Orders, No. 35, which transferred Major General George H. Thomas from the Army of the Ohio to command the Army of the Tennessee. Although Grant lost his field command, he kept command of the District of West Tennessee. To ease the sting, Halleck nominally “promoted” Grant to his second-in-command.

Siege of Corinth

On April 29, 1862, Halleck dispatched his army from Pittsburg and Hamberg Landings in three wings toward Corinth. It took Halleck’s army one month to traverse the twenty-two miles to Corinth. Cautious by nature and still smarting from the Confederate surprise attack at Shiloh, Halleck insisted his soldiers dig new defensive trenches each time they moved to a new position. By May 25, after traveling only five miles in three weeks, Halleck was close enough to Corinth to shell the Confederate defenses and lay siege to the town.

Inside the town, the Confederates were running out of water, and nearly 20,000 of them suffered from wounds, dysentery, and typhoid. On May 29, Beauregard began evacuating his sick and wounded soldiers and withdrawing his supplies. When Union soldiers approached the Confederate fortifications on the morning of May 30, they found them undefended.

Although it took Halleck over one month to capture Corinth, he did so with very little bloodshed. That fact was not lost upon Halleck’s men, many of whom had taken part in the bloodbath at Shiloh and who expected the same at Corinth.

Grant’s Command Restored

Ten days after his triumph at Corinth, Halleck dismantled the large army he had created. On June 10, 1862, he issued Special Field Orders, No. 90, (Department of the Mississippi) revoking Special Field Orders, No. 31. The directive stated that,

The order dividing the army near Corinth into right wing, center, left wing, and reserve is hereby revoked. Major-Generals Grant, Buell, and Pope will resume the command of their separate army corps, except the division of Major-General Thomas, which, till further orders, will be stationed in Corinth as a part of the Army of the Tennessee.

Although Beauregard’s army escaped to fight another day, the Northern press and the Lincoln administration celebrated the Union victory. On July 11, President Lincoln summoned Halleck to Washington and placed him in charge of all federal armies, hoping he might duplicate his success on a larger stage. Before departing, Halleck issued Special Orders, No. 161 (Department of the Mississippi), which expanded Grant’s responsibilities as commander of the District of West Tennessee, to “include the Districts of Cairo and Mississippi; that part of the State of Mississippi occupied by our troops, and that part of Alabama which may be occupied by the troops of his particular command, including the forces heretofore known as the Army of the Mississippi.” For the next few months, Grant deployed his troops to secure Union inroads made into Tennessee and Mississippi earlier in the year.

On October 16, 1862, the War Department issued General Orders No. 159 , creating the Department of Tennessee and placing Grant in command of the new department. Although still not officially designated the Army of the Tennessee, the informal handle for Grant’s forces was now more closely aligned with the actual name of his command.

Vicksburg Campaign

With two of the three main rivers connecting the North and South in the Western Theater under Union control, Grant turned his attention to Vicksburg, Mississippi. Known as “The Gibraltar of the Confederacy” because of its location on a high bluff overlooking a horseshoe-shaped bend on the Mississippi River, Vicksburg was key to controlling traffic on the Mississippi River. Grant resolved to capture the river fortress and split the Confederacy in two, denying its supplies from the Far West.

The bluff upon which the city sits made Vicksburg nearly impossible to assault from the river. To the north, nearly impenetrable swamps and bayous protected the city. To the east, a ring of forts mounting 172 guns shielded the city from an overland assault. The land on the Louisiana side of the river, opposite Vicksburg, was rough, etched with poor roads and many streams.

After several failed attempts to assault the city, from December 1862 through April 1863, Grant settled on a bold plan to march his army down the west side of the Mississippi, cross the river south of Vicksburg, and attack the fortress from the south and the east. In late March, federal engineers undertook the arduous task of building roads and bridges through swamps in Louisiana, so that Grant could march his army south.

By late April, Grant’s army crossed the river south of Vicksburg, back into Mississippi. On May 14, 1863, Grant captured the Mississippi capital at Jackson and gained control of the railroad into Vicksburg, denying the Confederate defenders in the river fortress supplies or reinforcements.

The Federals then converged on Vicksburg and the trapped Confederate army. After two failed attempts to assault Vicksburg on May 19 and 22, Grant besieged the city . The Confederate Army, along with Vicksburg’s civilians, held out for six weeks, but on July 4, 1863, the Confederate commander, Lieutenant Commander John C. Pemberton surrendered his army and the city .

Major General in the Regular Army

Grant’s victory propelled him to new heights. Three days after Pemberton surrendered, Halleck wrote to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton , “I respectfully recommend the following appointments: Major Gen Ulysses S. Grant. Vols. to be Major Genl in the U.S. Army, to date from July 4th, the capture of Vicksburg.” On the same day, Stanton approved Halleck’s recommendation, and Halleck telegraphed Grant, “It gives me great pleasure to inform you that you have been appointed a Major Genl in the Regular Army, to rank from July 4th, the date of your capture of Vicksburg.” On July 18, 1863, Grant wrote to Brigadier General Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General of the Army, “I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of notice of my appointment as Maj. General in the Army of the United States and my acceptance of the same.”

General Order Number 11

Although a great Union victory, the Vicksburg Campaign was not without some controversy for Grant. Exasperated by black-market trade between Northern merchants and Confederates, Grant issued his ill-conceived General Order Number 11, on December 17, 1862, expelling all Jews from the Department of the Tennessee. The order created such a protest throughout the North that President Lincoln rescinded it on January 4, 1863.

Also, that spring several Union generals engaged in a smear campaign, accusing Grant of being a drunkard. When Lincoln reviewed the allegations he purportedly said, “If it [drink] makes fighting men like Grant, then find out what he drinks, and send my other commanders a case!” Despite the humor, Lincoln took the allegations seriously enough to send Charles Anderson Dana to keep a watchful eye on Grant. It was during this time that Grant’s friend and adviser, John Aaron Rawlins, reportedly devoted himself to helping Grant maintain his sobriety.

Chattanooga Campaign

On October 16, 1863, the War Department issued General Orders, No. 337 merging the departments of the Ohio, the Cumberland, and the Tennessee under Grant’s command. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton directed Grant to move as soon as possible to Chattanooga, Tennessee to assist the Army of the Cumberland , which was under siege by General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Grant quickly ordered Major General William T. Sherman to transport the Army of the Tennessee from Mississippi to Chattanooga to reinforce the Army of the Cumberland. Grant himself arrived in Chattanooga on October 23, 1863, and took personal command of all forces within the city.

Upon his arrival, Grant set about establishing a new supply line into Chattanooga, known as the “Cracker Line.” The Cracker Line reduced the distance of the existing supply line into the city by half. On October 30, 1863, the first supplies began arriving in Chattanooga over the new route, and conditions within the city immediately improved.

While awaiting Sherman’s arrival, Grant began preparing for offensive operations to drive the Confederates away from Chattanooga and relieve the city. Sherman’s army began arriving at Chattanooga on November 20, and on November 23, the offensive moved into action. On November 23, about 14,000 federal soldiers left their defensive works and overran the 600 Confederate defenders of a hill between Chattanooga and Seminary Ridge, known as Orchard Knob. The Union soldiers fortified the hill, and Orchard Knob served as Grant’s headquarters for the rest of the breakout. The next day, about 10,000 Union forces under the command of Major General Joseph Hooker captured Lookout Mountain , a strategic position overlooking Chattanooga.

On November 25, a large-scale federal assault on Missionary Ridge forced Bragg to retreat into northern Georgia. The successful breakout ended the siege and gave the Union uncontested control of Chattanooga, the “Gateway to the Lower South.”

After lifting the siege at Chattanooga, Grant sent Sherman north to help end General James Longstreet’s siege of Major General Ambrose Burnside’s forces in Knoxville, Tennessee. Faced with Sherman’s advancing army, Longstreet withdrew from the Knoxville area on December 3 and 4, giving the Union complete control over Tennessee.

Lieutenant General in Command of U.S. Armies

On February 29, 1864, President Lincoln signed legislation restoring the rank of lieutenant general in the United States Army. The next day, Lincoln submitted Grant’s nomination, and Congress confirmed it on March 2. On March 3, Grant traveled to Washington to receive his commission. On March 10, Lincoln issued an executive order announcing

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, U.S. Army, is assigned to the command of the armies of the United States

On March 17, 1864, Grant issued General Orders, Number 12, taking command of the armies. Grant brought with him a reputation for the doggedness that Lincoln was seeking. Unlike previous Union generals, Grant was tenacious.

War in the East: the Overland Campaign

Upon his arrival in Washington, Grant drafted a plan to get the various Union armies in the field to act in concert. He also devised his Overland Campaign to invade east-central Virginia and destroy Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia . Grant instructed General George Meade , who commanded the Army of the Potomac, “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.” Grant realized that with the superior resources he had at his disposal, Lee would lose a war of attrition, as long Grant persistently engaged him.

On May 4, 1864, Grant launched the Overland Campaign when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. Although Meade nominally commanded the Army of the Potomac, as General-in-Chief of the Armies, Grant accompanied the army in the field so he could supervise overall campaign operations.

Throughout the month of May, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia slugged it out in a series of battles including the Wilderness (May 5-7), Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21), North Anna (May 23-26), Totopotomoy Creek (May 29-30) and Cold Harbor (May 31-June 12, 1864). Although the Confederates inflicted high casualties on the Federals during those battles, Grant continued his strategy of moving south and east to Lee’s right and then re-engaging the Confederate forces. Grant’s moves forced Lee to re-position his lines continually to defend Richmond.

The Overland Campaign was a strategic success for the North. By pounding at the Army of Northern Virginia, Grant hindered Southern efforts to send reinforcements to halt the scorched earth campaigns of Philip Sheridan in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and William T. Sherman in Georgia. In addition, although the Federals suffered higher casualties (39,000 to 31,500) than the South, the Confederacy could not replace their losses as readily as the North. Finally, Grant tied down the Army of Northern Virginia, limiting Lee’s options for the rest of the war.

Despite the strategic success of the Overland Campaign, it was not without its critics. High casualty rates and horrific battle conditions shocked war-weary Northerners. Some began referring to Grant as a butcher, whose strategy of winning by attrition exacted too high of a toll in human life. The mounting losses provided ammunition for Peace Democrats intent on defeating Lincoln in his reelection bid in 1864. Many critics fell silent by the autumn, however, as Grant’s strategy aided Sheridan’s and Sherman’s successful campaigns, thus securing the president’s re-election and enhancing prospects for restoring the Union.

Richmond Campaign and Surrender at Appomattox Court House

The battles of the Overland Campaign had forced Lee to leave Petersburg, Virginia—an important supply center near Richmond— unprotected. In early June 1864, Grant changed his strategy. Instead of pursuing the Army of Northern Virginia, Grant attacked Petersburg and cut off supplies to Lee’s army and the Confederate government in Richmond.

On June 15, 1864, Union forces overran Petersburg’s outer defenses. On June 16, the Federals renewed their attack, but Lee’s army reinforced the Confederate defenders on June 18. Unable to break through the Confederate defenses, Grant settled into a siege that lasted over nine months.

With his army weakened by desertions, disease, and hunger, Lee abandoned Petersburg and Richmond by late March 1865. On April 3, 1865, both cities surrendered to federal control. For the next few days, Grant pursued the Army of Northern Virginia until Lee capitulated at Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865 , marking the third time an entire Confederate army surrendered to Grant.

Grant’s terms of surrender were generous. None of Lee’s soldiers would be imprisoned or prosecuted for treason. In addition, Grant allowed Lee’s officers to keep their sidearms and personal baggage. Grant also allowed soldiers with horses or mules to take them home to help with the spring planting. Finally, Grant supplied rations for Lee’s starving army.

Lee’s surrender to Grant did not end the American Civil War, but it doomed the Confederacy. As news of the surrender spread, other Southern armies laid down their arms. By May 13, 1865, the fighting stopped, and the war was over.

Post-war Life

Following the Civil War, Grant remained in the United States Army. On July 25, 1866, Congress enacted legislation reviving the grade of General of the Army. On the same day, President Andrew Johnson appointed Grant to the post.

Grant also became involved in the conflicts between the United States Congress and the President. Johnson sought a lenient policy towards Southern states that had seceded from the Union, while a majority in Congress wanted a harsher approach. Congress repudiated Johnson’s plan for Reconstruction, but the president retaliated by firing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. By doing so, Johnson did not follow the recently passed Tenure of Office Act. That act stated that the president could not fire any officeholder that had received Senate approval before being hired until the Senate approved a successor. Johnson violated this act by firing Stanton and replacing him with Grant. Grant quickly resigned from the office, preferring to remove himself from the dispute.

President Grant

In 1868, the Democratic Party chose Horatio Seymour as its presidential candidate. Seymour, a former governor of New York, supported states’ rights and opposed equal rights for African Americans. The Republican Party selected Grant, a defender of equal opportunities for blacks and a supporter of a strong federal government. On Election Day, 53% of American voters selected Grant. He easily won the Electoral College vote, capturing twenty-six of the thirty-four states, to become the 18th President of the United States. Grant sought reelection in 1872 and easily won again, receiving fifty-six percent of the popular vote.

Political scandals marred Grant’s presidency. Several leaders and cabinet members engaged in corrupt activities. Grant remained above the controversy, but many Americans faulted him for his political appointments and his inability to control his cabinet.

In the South, the nation seemed far from healing its war wounds. Violence increased between whites and the African-American population. A growing number of Republicans lost their enthusiasm for Radical Reconstruction policies and encouraged Grant to withdraw federal troops from the South.

In 1873, an economic depression further alienated the American people from Grant . Thousands of businesses closed over the next five years, causing rampant unemployment. Because of Grant’s declining popularity, the Republican Party nominated Rutherford B. Hayes as president, even though Grant desired to seek a third term. Grant also sought the party’s candidacy in 1880, but the Republicans selected James Garfield instead.

See Gilded Age Politics for more on Grant’s Presidency.

On May 17, 1877, Grant and his family embarked on a trip around the world that lasted over two and one-half years. During the trip, huge crowds in many countries wildly received and honored Grant. When he returned home in December 1879, Grant settled in New York City. At his son’s urging, Grant became a silent partner in the brokerage firm of Grant and Ward. In May 1884, he discovered that Ferdinand Ward had swindled him of his life savings and left him $150,000 in debt. Determined to repay his debts and provide for his family, Grant began writing articles about his military life for The Century Magazine during the summer. In November of the same year, doctors informed Grant that he had throat cancer.

Grant’s cancer diagnosis presented the general with one last test of the mettle that had served him so well in the Civil War. On February 27, 1885, Grant signed a contract with his friend Mark Twain to publish his memoirs. Sales of the work provided financial resources to support Grant’s family after his death.

On March 4, 1885, President Chester A. Arthur signed legislation to restore Grant to the rank of General of the Army, providing Grant’s family with a much-needed pension. Throughout the spring, Grant endured overwhelming pain as he dictated his memoirs. Incredibly, by May 23, 1885, the first volume of the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant went to press. By then, Grant could no longer speak.

In June, Grant moved to the cooler climate of Mount McGregor in eastern New York State. Wracked with pain, Grant used pencils to scribble the second volume of his memoirs on paper tablets for Frederick, his oldest son, and Adam Badeau, a former staff member, to transcribe. Grant completed the second volume on July 19, 1885. Four days later, he died, surrounded by his family. Grant’s memoirs became an immediate bestseller and ensured that Grant’s wife, Julia, would be financially secure for the rest of her life.

Grant’s family held funeral services at Mount McGregor on August 4, 1885. They then publicly displayed his coffin at Albany, New York, and the City Hall in New York City, before interring Grant’s remains in Riverside Park in New York. On April 27, 1891, workers broke ground for the construction of Grant’s Tomb. Officials dedicated the tomb on April 27, 1897, the 75th anniversary of Grant’s birthday.

Grant’s legacy remains mixed. To be sure, corruption and his poor judgment of character tarnished his presidency. Critics have made much about Grant’s struggles with alcohol, although there is no evidence that drinking had any detrimental effects on his combat performance. Some have even questioned Grant’s military leadership, suggesting that he succeeded on the battlefield because he enjoyed overwhelming advantages in men and materiel. Such assertions, however, diminish Grant’s inspired campaigns at Vicksburg and Chattanooga. They also overlook the fact that Grant succeeded where other Union generals who enjoyed the same advantages failed. Despite his personal aversion to blood and distaste for the savagery of battle, Grant’s doggedness and determination drove him to victories that eluded others, and eventually restored the Union.

- Written by Harry Searles

Ulysses S. Grant

Read about Grant’s life.